The Moon is Calling: NASA Gets Serious About Artemis II Launch Timeline

There's a moment in any major space mission when you can feel the momentum shift. The conversations get sharper. The timelines tighten. The executives start talking publicly about launch dates instead of technical hurdles.

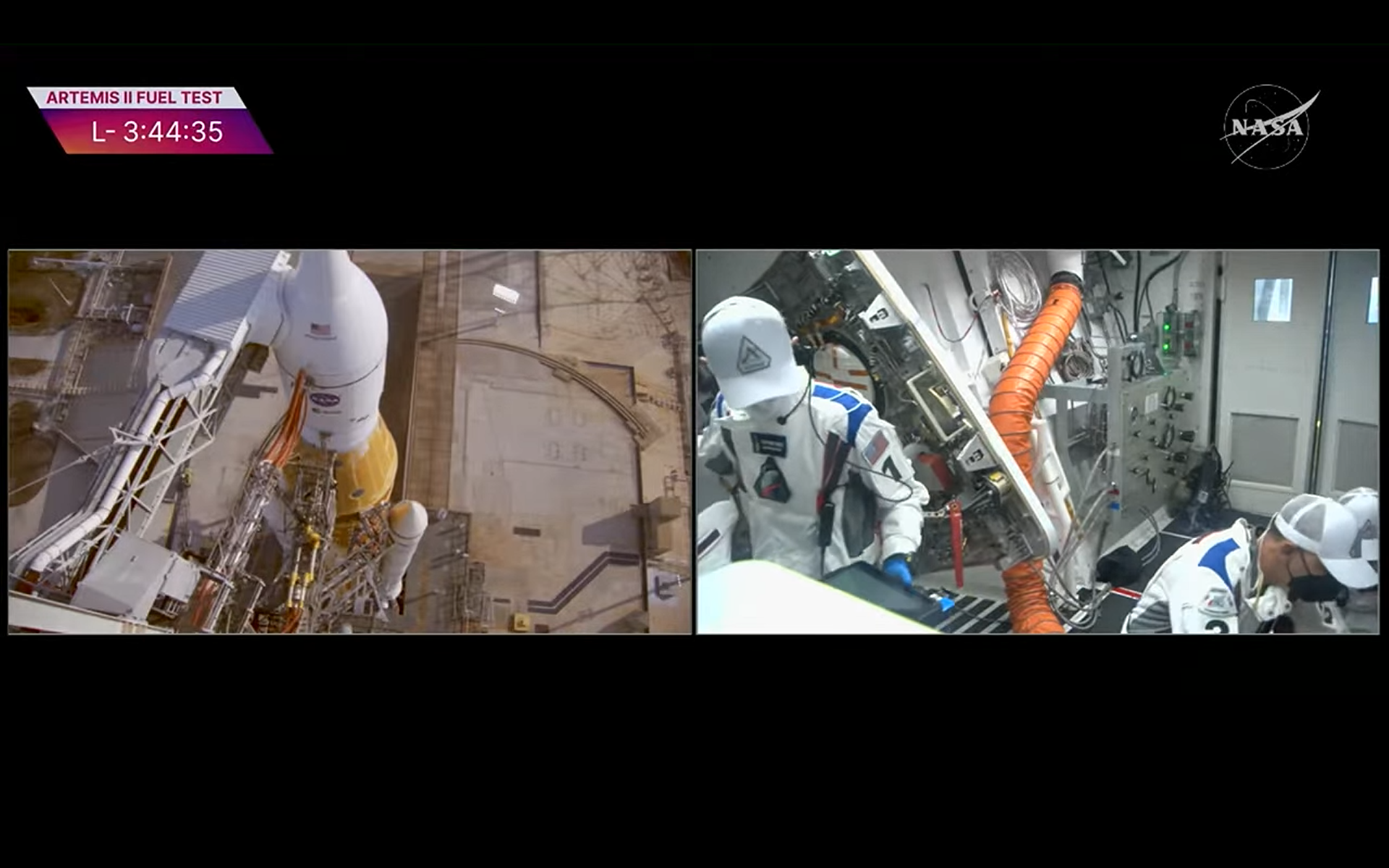

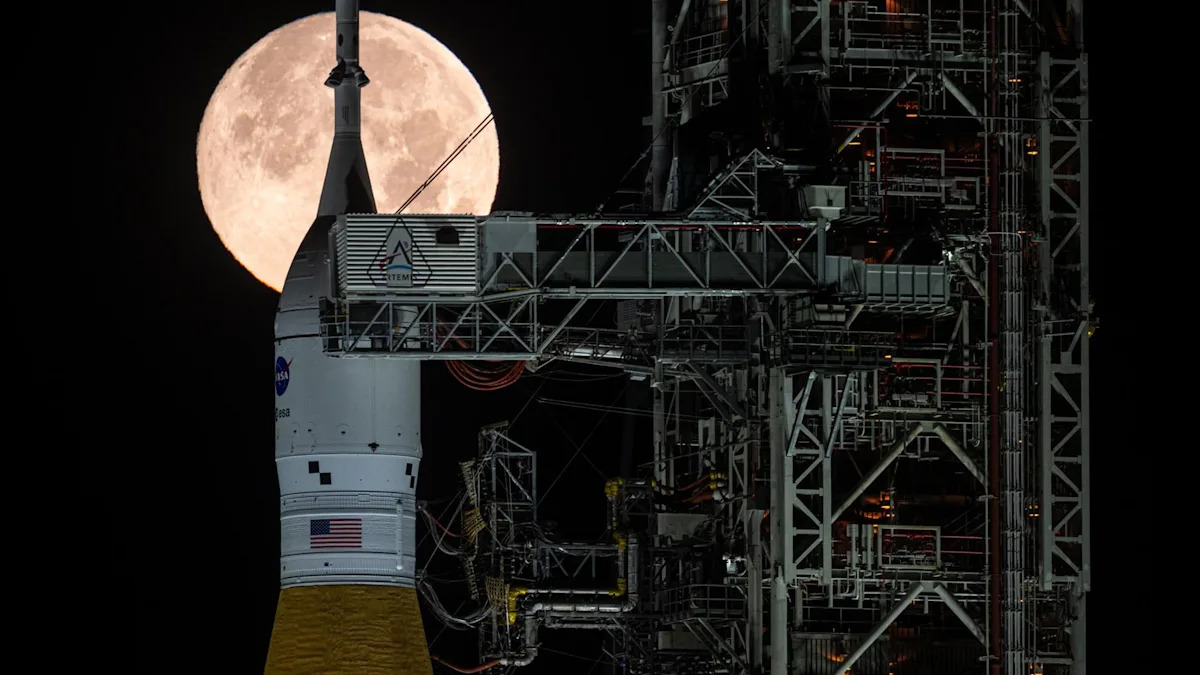

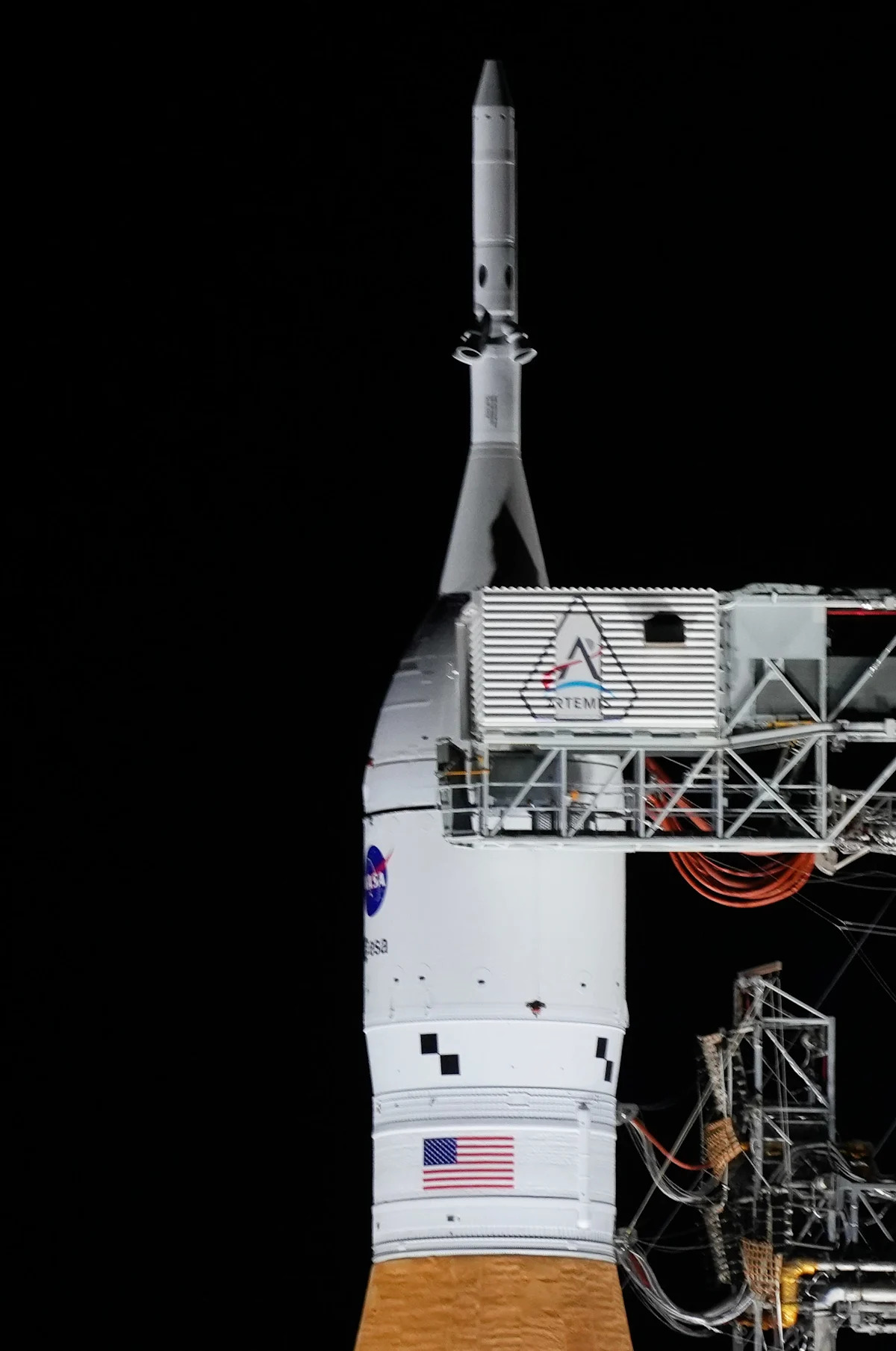

NASA hit that moment on February 20, 2026. After spending weeks wrestling with a stubborn hydrogen leak that derailed the first fueling test, NASA's teams proved Thursday night that they'd actually fixed the problem. The Space Launch System rocket sat on the pad at Kennedy Space Center, got completely fueled up without incident, and ran through a full countdown rehearsal that showcased the kind of precision you want to see before launching four humans around the Moon.

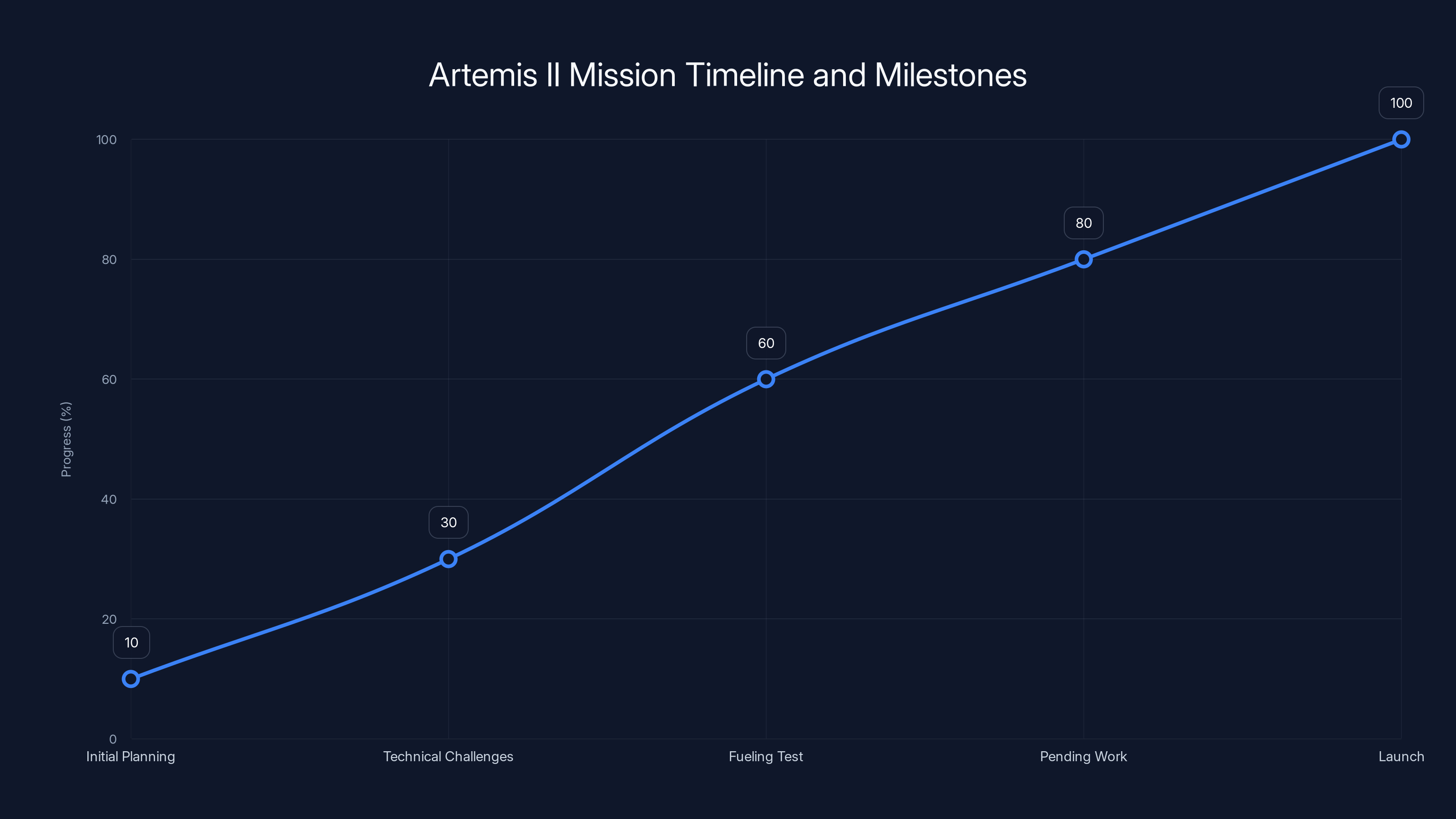

The result: NASA is now targeting March 6 as the earliest launch opportunity for Artemis II. That's five months after the mission was originally scheduled for September 2024, but it's progress. Real, concrete progress.

But here's the thing about spaceflight. Confidence and caution exist in the same space. Yes, Thursday's test went well. Yes, the seals held. Yes, the countdown proceeded nearly on schedule. And yes, there's still an enormous amount of pending work before these four astronauts strap into the Orion spacecraft and head toward the lunar farside.

Lori Glaze, NASA's acting associate administrator for exploration programs, was careful about how she framed this moment. "We're now targeting March 6 as our earliest launch attempt," she said during the post-test briefing. "I am going to caveat that. I want to be open, transparent with all of you that there is still pending work. There's work, a lot of forward work, that remains."

That caveat matters. It shows the maturity of NASA's decision-making process. This isn't a room full of engineers and managers desperate to announce a launch date and move on. This is an organization that's learned hard lessons about the difference between "we think we're ready" and "we are actually ready."

So what exactly happened during Thursday's test? Why did it succeed where February's attempt failed? What comes next? And what does this timeline mean for NASA's broader lunar ambitions?

Let's walk through it.

What Went Wrong in February (And Why It Almost Derailed Everything)

The first Wet Dress Rehearsal on February 2 was supposed to be routine. Fuel the rocket. Run the countdown. Practice the procedures. Learn what you need to learn. It wasn't supposed to become a technical deep-dive into hydrogen leak physics.

But that's what happened. About three hours into the fueling operations, technicians detected hydrogen building up in an area it shouldn't be. Specifically, the leak occurred at the connection where supercold liquid hydrogen flows from the launch platform into the SLS core stage. This is one of the most critical connections on the entire vehicle.

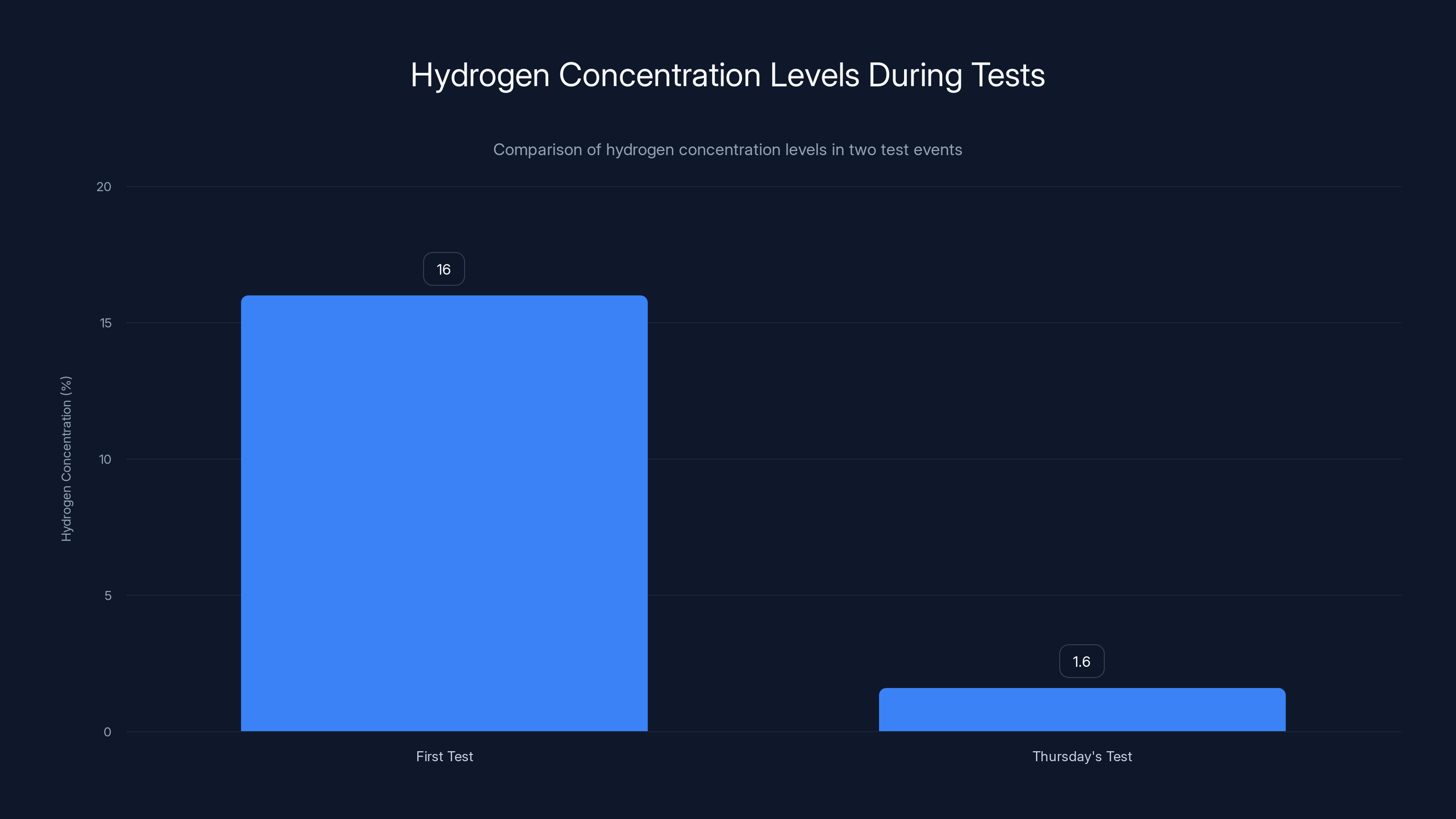

Hydrogen is tricky stuff. It's incredibly light, so it evaporates almost instantly when exposed to air. It's also incredibly dangerous in certain concentrations. NASA has strict safety limits: if hydrogen concentration exceeds 16 percent in any enclosed space near the launch pad, the countdown stops. Period. No exceptions.

During that first test, hydrogen sensors near the connection detected concentrations exceeding that 16 percent threshold. The launch team paused the fueling operation. They tried restarting the flow. The leak contained itself briefly. Then as the core stage fuel tank started pressurizing in the final minutes of the countdown, the hydrogen concentrations spiked again. NASA called it. The test ended. Propellants got drained. The rocket sat there, inert and unhelpful.

This is the thing about problems with fueling umbilicals: they're not always simple to fix. The umbilical isn't just a pipe. It's an incredibly complex assembly that carries multiple flows (liquid hydrogen, liquid oxygen, pressurization gases, coolant lines, electrical connections, and more) from the launch pad into the vehicle. The seals on these connections are made of Teflon, a material that's chemically resistant and thermally stable but also notoriously finicky about installation, temperature variations, and cyclic loading.

NASA had dealt with similar hydrogen leaks during preparation for Artemis I in 2021. Those took weeks to resolve. The fact that they could identify a likely culprit and develop a fix in just over two weeks suggested something encouraging: they'd learned from those previous experiences.

The diagnosis was that the seals themselves needed replacement. The suspected cause was either improper seating or some kind of micro-damage from the first attempt. Either way, the fix was straightforward in theory: disconnect the umbilical, swap out the seals, reconnect, and try again.

What made this a compressed timeline issue was the launch window. NASA can't launch the Artemis II mission on arbitrary dates. The Moon's position, the intended trajectory, the Earth-Moon geometry, thermal and lighting constraints at the landing site, and a dozen other factors combine to create a launch window that opens up only a few days each month. Miss February, and you're looking at March. Miss March, and you might be looking at April. And those delays have a cascading effect through the entire program.

So the pressure was real. Get the seals replaced and proven out quickly, or lose significant schedule margin.

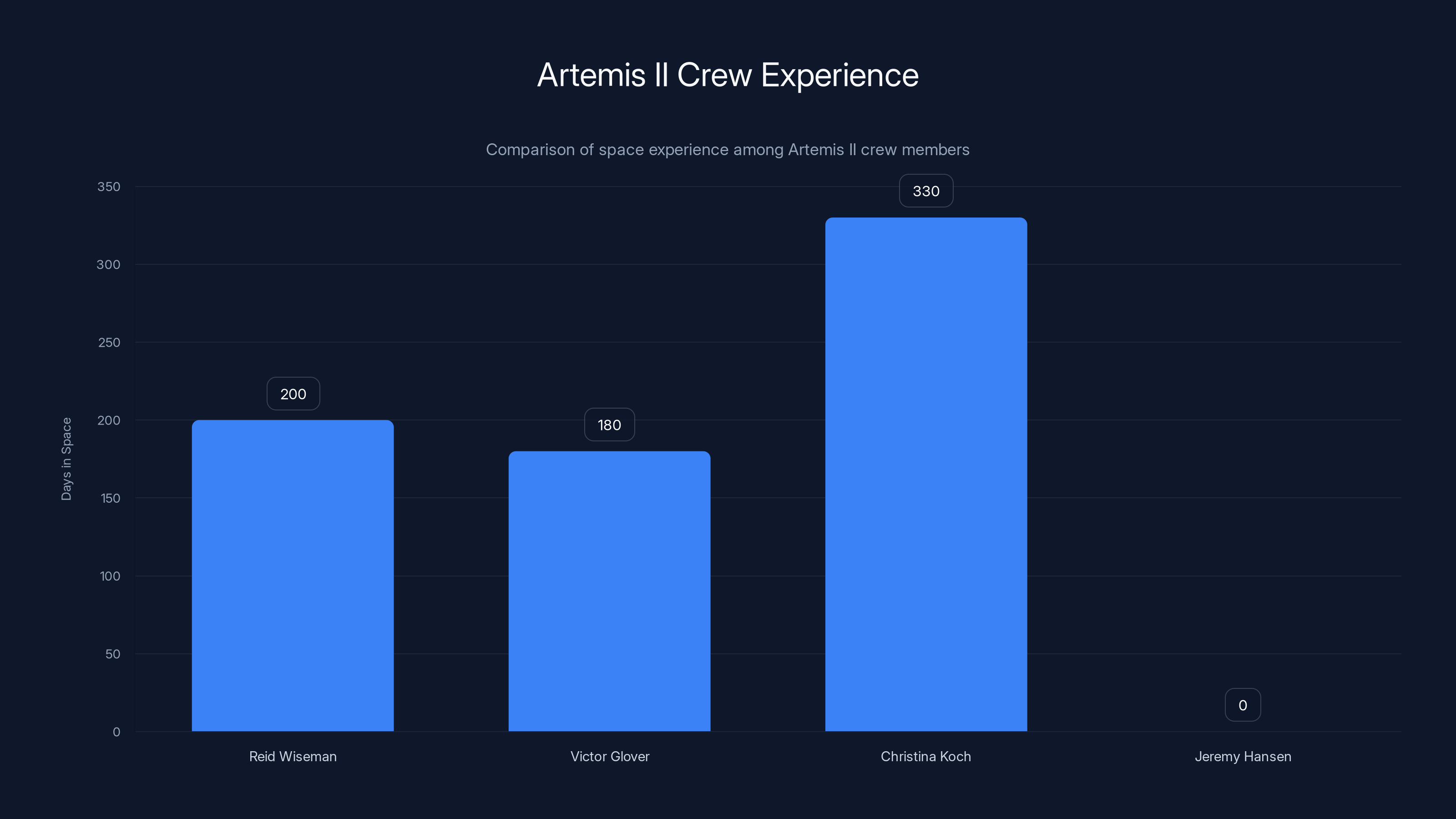

Christina Koch leads the Artemis II crew with 330 days in space, highlighting her extensive experience compared to her fellow crew members.

Thursday's Test: What Actually Changed

On Thursday, February 20, things went differently. The countdown ran almost perfectly to the planned schedule. The launch team proceeded through fueling operations with no major pauses or holds. More importantly, the hydrogen sensors stayed quiet. While the first test had sensors spiking above 16 percent concentration, Thursday's readings topped out at 1.6 percent. That's roughly one-tenth of the safety limit. Not only acceptable—it's the kind of number that makes engineers actually smile.

Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, who serves as NASA's Artemis II launch director, is one of the most experienced countdown engineers in the world. She's directed dozens of Space Shuttle missions and has been guiding the SLS program through test after test. When she said the hydrogen seals showed "very good performance," it carried weight.

"The countdown ran close to the planned schedule, allowing the launch team to complete two runs through the final 10-minute terminal countdown sequence before ending the test at T-minus 29 seconds," Blackwell-Thompson said. "When we wrapped all that up, we still had launch window remaining. So, very successful day. I'm very proud of this team and all that they accomplished."

Notice that phrase: "still had launch window remaining." That means they finished the test early. In spaceflight, finishing early is almost as valuable as finishing on time. It proves your operations have enough margin built in. It proves you're not flying right at the edge of your constraints.

But the hydrogen seals weren't the only thing being tested Thursday night. The launch team also exercises a comprehensive suite of vehicle systems: avionics, communications, pressurization systems, electrical networks, control systems, sensor arrays, and more. During a Wet Dress Rehearsal, technicians actually flow cryogens through the systems at operational pressures and temperatures. This stresses the hardware in ways that desktop simulations simply cannot replicate.

Two secondary issues did pop up during Thursday's test. First, a communications problem briefly affected the launch team's ability to relay commands to the vehicle. Nothing that suggested a fundamental issue, but it triggered a pause in operations while engineers verified all was well. Second, there was a potential issue with one of the booster avionics systems—basically, the computer systems that control the solid rocket boosters.

John Honeycutt, NASA's chair of the Artemis II Mission Management Team, addressed both issues during the post-test briefing. "So far, we don't have any indications of anything that we're worried about, but we're just getting started with the data review," he said. "We'll go through that and see what the teams come up with and address those as needed, but overall, it was a good day for us."

That measured tone—neither dismissive nor alarmist—is the appropriate response to secondary issues discovered during testing. You don't want to find problems during flight. Finding them during rehearsals is exactly what you're supposed to do.

The Artemis II mission has progressed through various stages, with the recent successful fueling test marking a significant milestone. The mission is on track for a potential March 6 launch, pending completion of remaining tasks. Estimated data.

March 6: What the Target Date Actually Means

When NASA says March 6 is the "earliest launch attempt," that phrase carries specific technical meaning that's worth unpacking.

First, the date isn't arbitrary. NASA's launch window for Artemis II is constrained by orbital mechanics. The mission needs to depart Earth at a time that gets the Orion spacecraft to the Moon's distant retrograde orbit (DRO) at the right lunar phase, with proper lighting angles for thermal management, with proper viewing geometry for the landing sites NASA wants to evaluate, and with orbital energy that allows the vehicle to coast efficiently through space without excessive propellant expenditure.

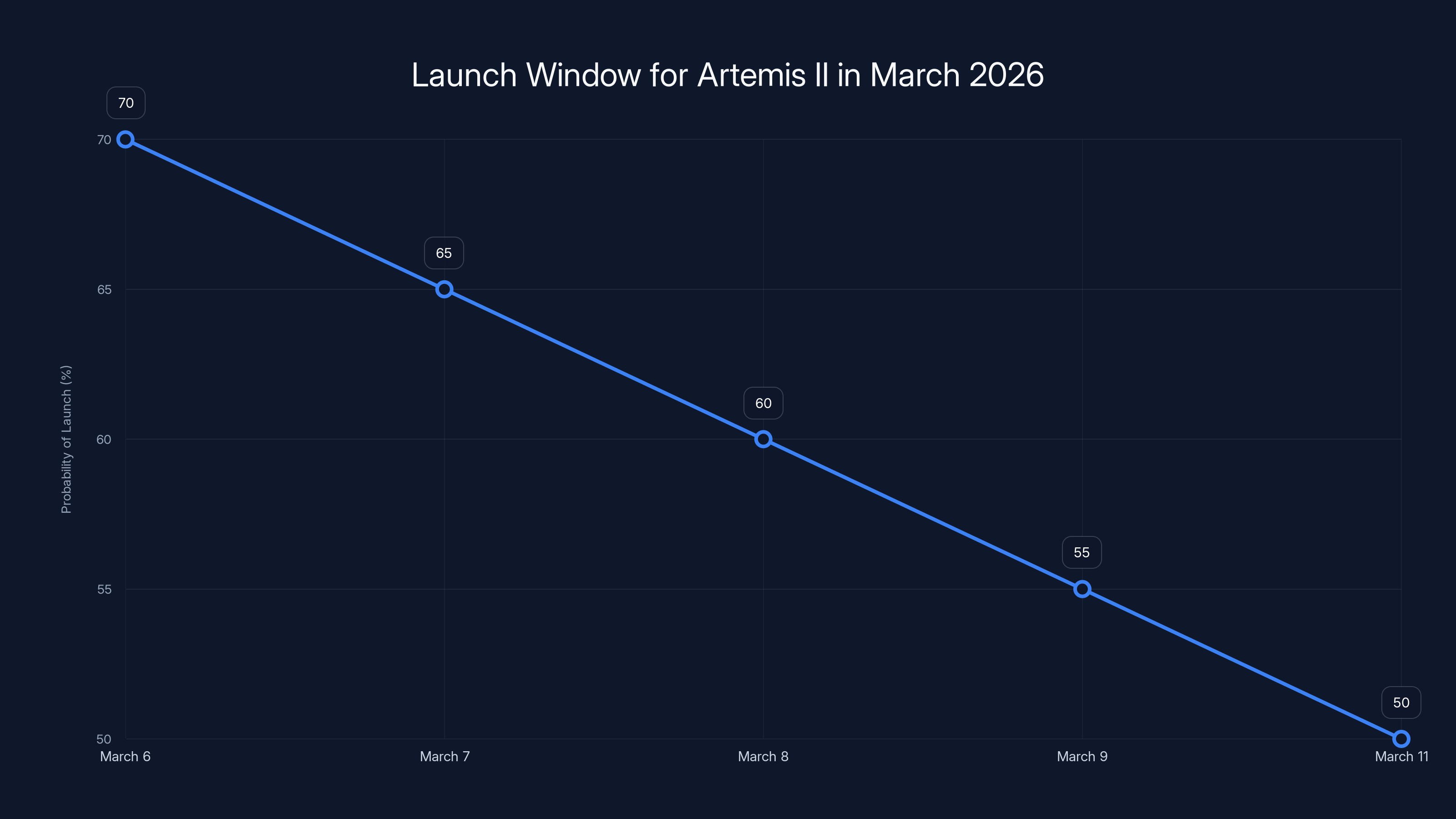

Those constraints combine to create a launch window that's only open on specific dates each month. For March 2026, those dates are March 6, 7, 8, 9, and 11. If the mission doesn't launch within that window, the next opportunity doesn't arrive until April.

Second, March 6 is the earliest date in that window. NASA is essentially saying: "If everything is ready and the weather cooperates, we can launch on this date." The liftoff window itself is two hours long, opening at 8:29 PM Eastern Standard Time on March 6 and closing at 10:29 PM. That two-hour window is standard for SLS launches and reflects the time it takes for the launch team to get the vehicle through final checks and actually ignite the engines.

Third, and this is crucial, the target date comes with caveats. Lori Glaze's emphasis on "pending work" wasn't just polite acknowledgment of how much remains to be done. It's recognition that multiple parallel tracks of activity have to complete successfully before launch can proceed.

These include:

-

Data analysis from Thursday's test: Engineers from multiple teams will spend weeks poring over the 30 million-plus data points collected during the test. Any anomalies, any unexpected behavior, any sensor readings that don't match predictions—all of it gets scrutinized. This isn't bureaucratic process; it's fundamental to understanding whether the rocket is actually ready.

-

Avionics system verification: The secondary issue with booster avionics needs investigation and resolution. The launch team needs confidence that the computers controlling the solid rocket boosters are functioning correctly and will respond as expected when the engines light.

-

Communications system refinement: The communications issue that briefly paused Thursday's countdown needs a root cause analysis. What caused the problem? Is it a hardware issue or a procedural issue? Is it a one-time event or a symptom of a larger problem? How do we prevent it on flight day?

-

Vehicle inspection and processing: After the test, the rocket sits on the pad. Technicians inspect every external surface, every connection, every system. The vehicle gets serviced. Any wear items get replaced. Consumables get replenished. This takes weeks.

-

Range and ground support infrastructure verification: Kennedy Space Center isn't just a launch pad. It's an integrated system of ground support equipment, communication networks, weather systems, launch control computers, and safety systems. All of it was exercised during the test. All of it needs verification.

-

Flight crew readiness: Commander Reid Wiseman, Pilot Victor Glover, Mission Specialist Christina Koch, and Mission Specialist Jeremy Hansen have been in training for two years. They've flown the Orion simulator hundreds of times. They've conducted emergency procedures until they're second nature. But there's always more training, more scenario practice, more contingency rehearsal. The flight crew needs to be at absolute peak readiness.

-

Launch team certification: NASA has formal processes for certifying that launch team members have completed all required training, all required qualifications, all required checkouts. Charlie Blackwell-Thompson and her team need to get formally certified as ready to conduct a crewed launch.

All of this has to align. There's no path to launch if any one of these tracks fails to complete on schedule.

The Artemis II Mission Profile: What We're Actually Launching

It's worth stepping back and understanding what this mission is. Because Artemis II isn't just another space launch. It's the first crewed flight of a system that hasn't flown humans in over five decades, and it's going to do something that hasn't been done since 1972.

The crew consists of four astronauts:

-

Reid Wiseman serves as commander. Wiseman is a former Navy test pilot who's logged more than 3,000 flight hours in military jets. He's also a veteran astronaut with prior experience on two Space Shuttle missions and one International Space Station expedition. He's logged over 200 days in space. When something goes wrong on Artemis II, Wiseman is the person in charge of fixing it.

-

Victor Glover is the pilot. Glover is also a Navy test pilot and a veteran astronaut with one prior ISS expedition. His expertise in orbital mechanics and spacecraft systems makes him the second-in-command and the person responsible for flying the Orion spacecraft.

-

Christina Koch and Jeremy Hansen are mission specialists. Koch is a veteran of two ISS expeditions and has logged nearly 330 days in space—more than any other woman in the astronaut corps. Hansen is a Canadian astronaut and former fighter pilot who's making his first spaceflight on this mission.

Their mission is structured in phases:

Launch and Earth Orbit: The SLS rocket will accelerate the Orion spacecraft and its service module to orbital velocity, achieving an elliptical orbit around Earth. Unlike Apollo missions, which used a separate third stage to reach lunar trajectory, Artemis II relies on the Orion service module engines to perform the trans-lunar injection burn. This burn happens when the spacecraft is over the Pacific Ocean, pushing Orion out of Earth orbit and toward the Moon.

Trans-Lunar Coast: For about three days, Orion will coast through space toward the Moon. The crew will have time to evaluate systems, conduct experiments, and adjust trajectory if needed. This is roughly the same journey duration as Apollo missions from the 1970s, but Orion has more capable life support systems and better radiation shielding.

Lunar Orbit Insertion: As Orion approaches the Moon, its engines will fire to slow the spacecraft, allowing the Moon's gravity to capture the vehicle into orbit. But this isn't a traditional circular lunar orbit. Instead, Orion will enter a distant retrograde orbit (DRO)—an orbit that's about 40,000 miles from the Moon on the far side. This unusual orbit has advantages: it's stable over long periods, requires minimal fuel to maintain, and provides excellent vantage points for surveying potential landing sites on the south pole.

Lunar Orbit Operations: The crew will spend several days in lunar orbit, conducting experiments and observations. They'll practice procedures they might use during future landing missions. They'll image the lunar surface from unique vantage points that will inform future landing site selection. They'll take samples and observations that will help NASA understand the lunar environment.

Return Journey: After about nine to ten days total mission duration, Orion's engines will fire again to leave lunar orbit and begin the journey home. The return trajectory is deliberately designed to be faster than the outbound journey, allowing Orion to coast back toward Earth in about three days.

Earth Entry and Recovery: As Orion approaches Earth, the spacecraft will separate into its pressure vessel and service module. The pressure vessel will hit the atmosphere at extreme velocity—roughly 25,000 miles per hour—and will experience deceleration forces exceeding nine Gs. The vehicle's heat shield will protect the crew as atmospheric friction heats the capsule exterior to temperatures exceeding 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Parachutes will deploy to slow the descent further. Finally, Orion will splash down in the Pacific Ocean west of San Diego, where recovery ships will retrieve the crew.

This is a nine to ten day mission to the Moon and back with four crewed astronauts aboard. It's the first crewed lunar mission in 54 years. It's going to be extraordinary.

Thursday's test showed a significant improvement in hydrogen concentration levels, reducing from 16% in the first test to 1.6%, well below the safety limit.

The Hydrogen Leak Problem: Why This Specific Issue Was So Stubborn

To understand why the hydrogen leak was such a persistent problem, you need to understand the physics and engineering involved.

Liquid hydrogen is stored at negative 423 degrees Fahrenheit. At that temperature, it's a cryogenic liquid with a density slightly less than water. It flows through umbilicals from the launch platform into the rocket's core stage, where it's mixed with liquid oxygen and burned to produce thrust.

The challenge is that hydrogen molecules are incredibly small—they're the smallest atoms on the periodic table. When hydrogen leaks from a high-pressure system into a low-pressure area, it doesn't just vanish into the air. It immediately vaporizes and disperses as a gas. In certain concentrations (roughly 4 to 75 percent by volume when mixed with oxygen), hydrogen becomes explosively flammable.

The umbilical connection where the leak occurred carries liquid hydrogen at high pressure and low temperature. The seals that prevent leakage from that connection are engineered to function in that extreme environment. They're made of Teflon, a material that's chemically inert and thermally stable. But sealing at cryogenic temperatures is genuinely difficult.

Here's why: metals contract when they cool. Seals contract when they cool. Everything contracts. But they don't all contract at the same rate. A seal that's tight at room temperature might develop gaps at cryogenic temperature. Conversely, a seal that's tight at cryogenic temperature might be over-compressed at room temperature, leading to material deformation.

Additionally, repeated thermal cycling—warming up and cooling down—can lead to seal degradation. Each time the system cycles, the seal material experiences stress. Over time, that stress leads to micro-cracks and material fatigue.

NASA's approach has been to use new seals for each fueling test and to closely monitor seal installation procedures. The February 2 test used seals that had been in place longer or under different conditions than ideal. The February 20 test used new seals installed with verified procedures, and those seals performed well.

But here's what engineers will tell you: you never have perfect confidence in cryogenic seals until you've actually flowed cryogenic propellant through them. Desktop testing and bench testing only get you so far. You have to actually freeze the system down, pressurize it, flow the fluid, and verify that the seals don't leak. That's what the Wet Dress Rehearsals are for.

The fact that Thursday's test showed hydrogen concentrations at only 1.6 percent suggests the seals are working. But NASA's engineers will spend weeks analyzing those numbers, understanding the source of even that small amount of hydrogen, and determining whether the performance is repeatable and robust.

Schedule Implications: Why This Matters for the Broader Artemis Program

Artemis II's launch date doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a coordinated sequence of missions that's supposed to build NASA's permanent presence at the Moon.

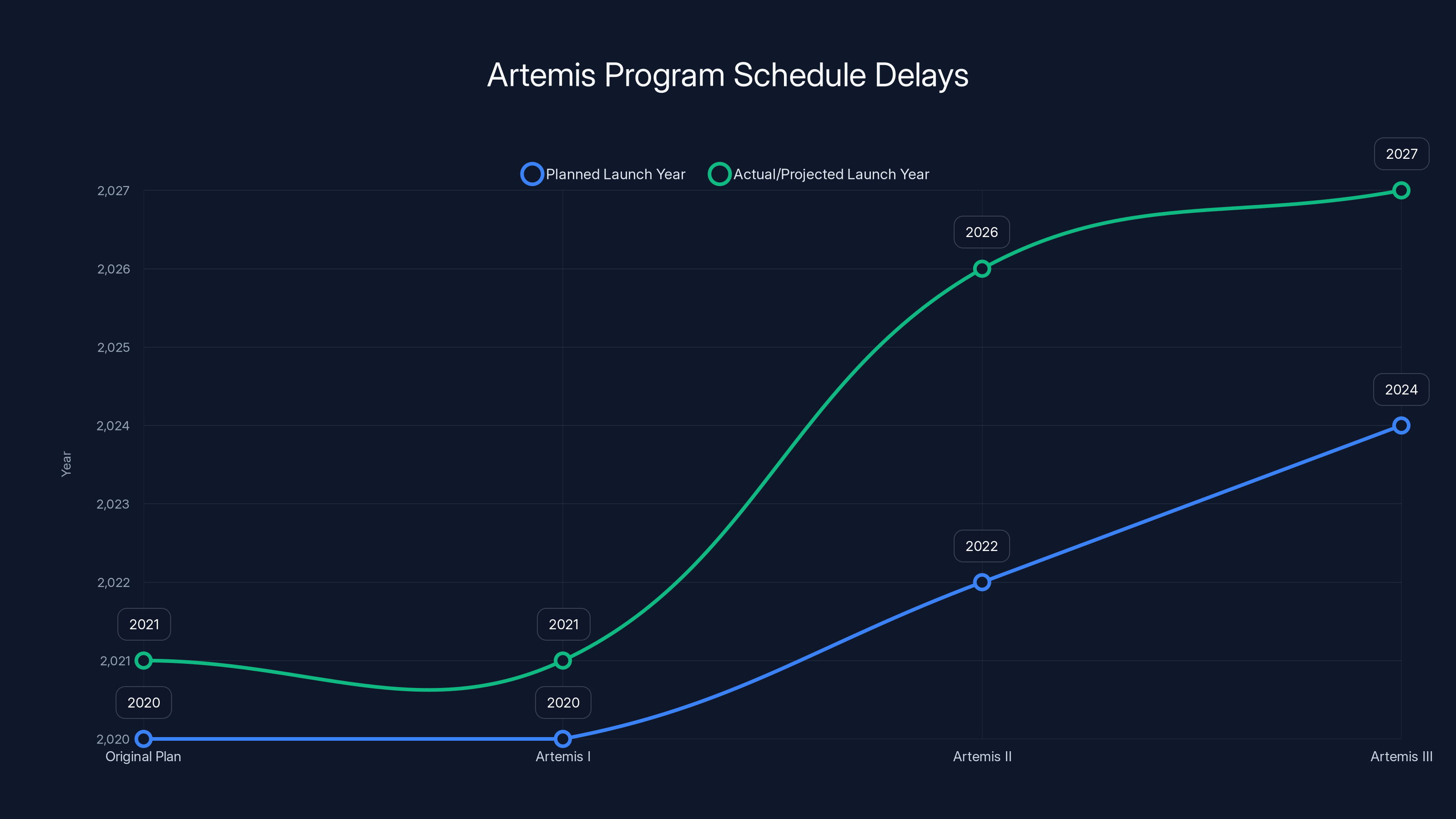

The original Artemis program schedule, announced in 2019, called for Artemis II to launch in 2022. That didn't happen. Technical challenges, budget constraints, industrial base issues, and COVID-related disruptions all contributed to delays. Artemis I, originally planned for 2020, didn't launch until November 2021. That delay had cascading effects on Artemis II.

Now, with a March 2026 target, NASA is targeting Artemis III for late 2026 or early 2027. Artemis III is the mission that's supposed to actually land astronauts on the Moon's south pole—the first human lunar landing since Apollo 17 in 1972.

But here's where schedule pressure becomes real: Artemis III's success depends on systems that don't even exist yet. Specifically, NASA needs:

-

A human-rated lunar lander: NASA has contracted with SpaceX (for the Starship Human Landing System) and Blue Origin (for the Blue Moon lander) to develop landing vehicles. These vehicles need to be built, tested, and certified as human-rated. That's years of work that's still ongoing. SpaceX's Starship is being actively tested, but there are still significant development milestones ahead.

-

Extravehicular activity (EVA) spacesuits: NASA and contractors are developing next-generation spacesuits for lunar operations. These suits need to protect astronauts in the harsh lunar environment, provide adequate mobility, and function reliably for extended surface operations. Current development timelines are aggressive and have risk.

-

Reliable SLS and Orion vehicles: Artemis II is essentially a certification flight for SLS and Orion. A successful mission demonstrates that these vehicles are human-rated and ready for operational use. A mission failure would set back the entire program significantly.

-

Ground infrastructure and supply chains: Maintaining and operating multiple SLS rockets and Orion spacecraft requires sustained industrial base capability. Suppliers need to remain engaged, production lines need to stay active, and skilled workforce needs to be retained.

All of these factors mean that the March 6 launch date, while hopeful, is also fragile. A one-month slip becomes a several-month slip when you account for the cascading effects on later missions, crew training, contractor readiness, and organizational coordination.

This explains why NASA is being both confident (the test went well) and cautious (there's still pending work) in its messaging. The organization has learned from the past five years that optimism and caution need to coexist in large-scale spaceflight programs.

The Artemis program has experienced significant delays, with Artemis I launching a year late and Artemis II projected for 2026, four years after the original plan. Estimated data for future missions.

The Crew's Perspective: Training for the Unknown

While engineers work through technical problems and schedule challenges, the flight crew is in constant training for a mission that's never quite happened before.

Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen are among the most thoroughly trained humans on Earth. Each crew member has logged hundreds of hours in high-fidelity simulators. They've practiced normal procedures until they're automatic. They've trained for dozens of failure scenarios until they can respond without hesitation.

But simulation is different from reality. There are aspects of spaceflight that you can't practice until you're actually in space. You can't truly feel weightlessness in a simulator (parabolic flights give brief tastes of it, but not sustained experience). You can't truly experience the cognitive load of operating in a spacecraft while in orbit. You can't truly understand how your body will respond to radiation exposure during a deep-space mission.

Artemis II will be a learning mission for the crew in that sense. Yes, they've trained extensively. Yes, they're extraordinarily capable. But they're also going to encounter things that surprised all previous astronauts. That's the nature of human spaceflight.

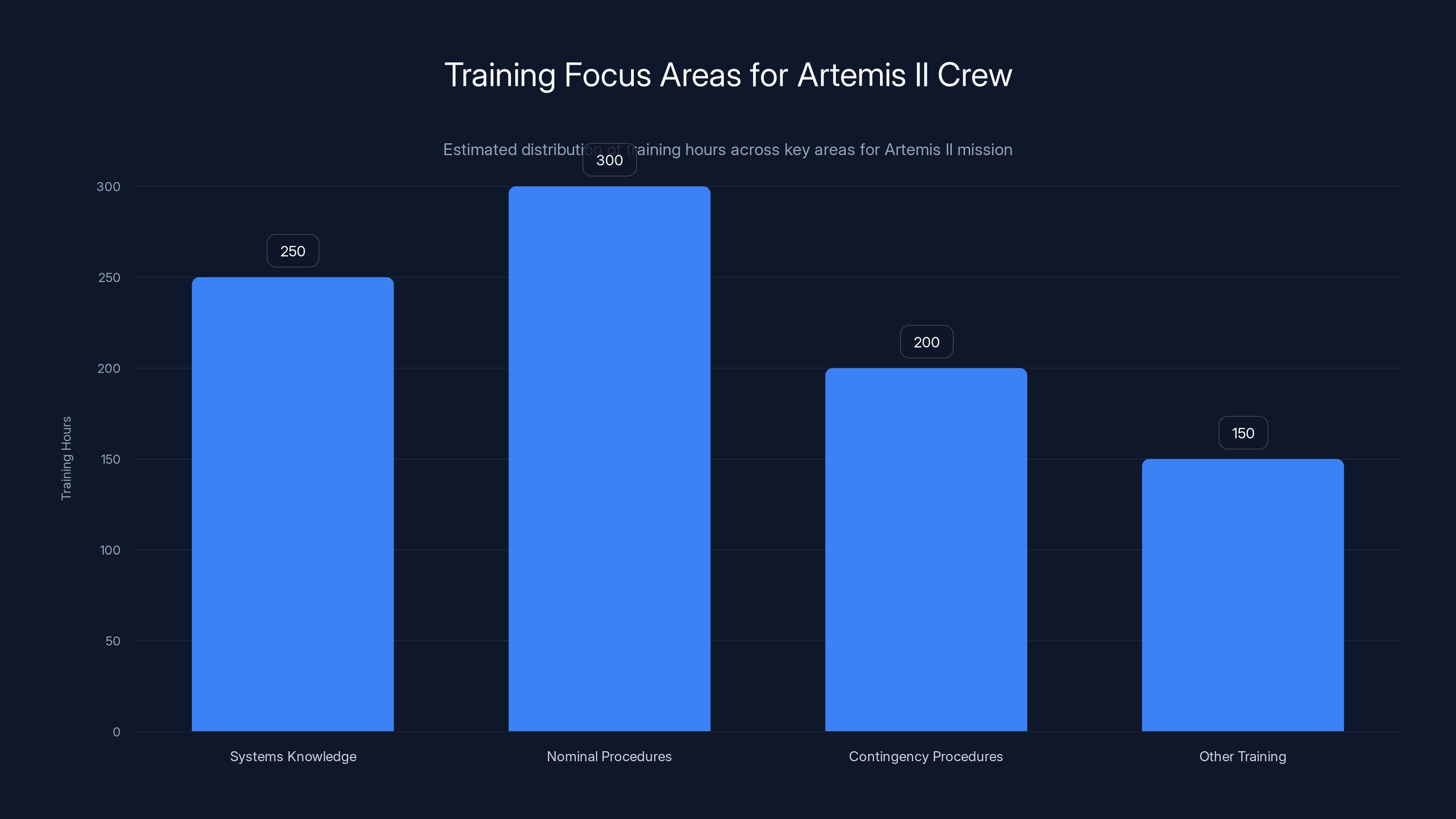

The training regimen for Artemis II is structured around these phases:

Systems knowledge: Each crew member has to master the technical systems of the Orion spacecraft and the SLS rocket. They need to understand not just how systems operate under nominal conditions, but how they degrade under failure conditions and what workarounds or procedures exist to manage those failures.

Nominal procedures: The crew practices the standard sequence of events for every phase of flight—launch, trans-lunar coast, lunar orbit insertion, lunar orbit operations, return trajectory, and entry. These procedures are practiced until they're second nature.

Contingency procedures: The crew practices what-if scenarios. What if an engine fails during launch? What if a navigation system malfunctions? What if life support develops a problem? For each possible failure mode, there's a procedure the crew needs to understand and be able to execute.

Vehicle familiarization: Unlike Apollo astronauts, who spent time in actual spacecraft capsules and trainers, modern astronaut training relies heavily on simulator fidelity. Still, the crew has spent time in mockups and hardware test articles to develop familiarity with the actual layout and controls of the Orion capsule.

Emergency egress: The crew has trained for emergency escape scenarios, including procedures for rapidly exiting the spacecraft if something goes wrong during pre-launch or immediate post-launch phases.

By the time the crew steps aboard Orion on launch day, they will have spent more than 1,000 hours in training for a nine-day mission. That's roughly 111 hours of training for every hour of flight. The ratio is high by modern standards (pilots of commercial aircraft spend roughly 60 hours training per hour of flying) but appropriate for a mission to the Moon.

Engineering Complexity: The Invisible Work Behind the Launch Date

When NASA announces a launch date, most people focus on that date. When will we launch? When can I watch? When should I make travel plans to Kennedy Space Center?

What's less visible is the absolutely staggering amount of engineering work that happens between a successful test and launch day.

Every system on the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft is interconnected. You can't change one thing without considering how that change affects everything else. The hydrogen fueling system affects pressurization systems. Pressurization systems affect structural loads. Structural loads affect vehicle dynamics. Vehicle dynamics affect guidance and navigation. Everything is connected.

So when the hydrogen seals were replaced, engineers had to verify:

- That the new seals were correctly installed with proper torque specifications

- That the fueling umbilical structural supports properly constrained the replacement connection

- That no damage occurred to adjacent components during the replacement work

- That the pressurization logic would function correctly with the new seals

- That vibration analysis still showed acceptable levels for the modified connection

- That thermal stress analysis was valid for the new seal configuration

- That the sealing surface finish met specifications

- That the material properties of the replacement seals matched design requirements

- That installation procedures were properly documented and verified

- That inspectors had certified compliance with all requirements

This isn't bureaucratic process for its own sake. This is engineering discipline. Each verification step exists because ignoring it has, in the history of spaceflight, led to failures.

Similarly, the secondary avionics issue that emerged during Thursday's test will trigger an investigation that includes:

- Data trending to understand whether the anomaly is isolated or systemic

- Root cause analysis to understand why the issue occurred

- Risk assessment to determine if the issue could affect flight-critical operations

- Corrective action planning to fix the underlying problem

- Verification testing to ensure the corrective action works

- Process improvement to prevent similar issues in the future

- Training updates for launch team personnel who might encounter similar issues

Each of these steps is necessary. Each takes time. Collectively, they ensure that when the rocket launches, you're launching something that's been thoroughly understood, rigorously tested, and properly prepared.

The Artemis II crew dedicates significant time to mastering nominal procedures, followed by systems knowledge and contingency procedures. Estimated data based on typical astronaut training regimens.

Historical Context: Learning from Five Decades of Rocket Science

Artemis II is succeeding or failing in the context of everything NASA learned from building and flying rockets since 1960.

When NASA and contractors first started fueling Space Launch System vehicles (which happened only recently—the first SLS rocket was fueled for Artemis I in 2022), they immediately encountered hydrogen leak problems. These weren't surprises to engineers who understood cryogenic systems. They were expected problems that needed engineering solutions.

The fact that NASA has persisted through two fueling tests, identified the problem, developed a fix, and demonstrated that the fix works is exactly how the engineering process is supposed to function.

Compare this to the Apollo program, where many critical systems were only fully tested during actual flight missions. The Saturn V rocket that took humans to the Moon was a marvel of engineering, but it also had single points of failure and limited redundancy. Astronauts accepted higher risk because the stakes were different and society's tolerance for risk was higher.

Modern spaceflight has different constraints. Public tolerance for risk is lower. Accountability is higher. The requirement for evidence of readiness is more stringent. This means more testing, more verification, more engineering work.

But it also means that when a mission does launch, you have genuine confidence that it's ready. The delays aren't signs of failure. They're signs of thoroughness.

The Broader Vision: Why Artemis II Matters Beyond the Launch Date

Artemis II is marketed as a lunar mission. And yes, it is. But it's also something more significant: it's a proof-of-concept for NASA's broader strategy of sustainable lunar exploration.

The Artemis program isn't designed to be a flag-planting exercise like Apollo. It's designed to establish patterns of regular lunar access that can be sustained for decades. The goal is to create a "lunar economy" where multiple organizations—government agencies, commercial companies, international partners—can access the Moon's resources and conduct diverse operations.

Artemis II serves several roles in this vision:

System validation: Artemis II proves that SLS and Orion work in the actual deep-space environment. No amount of ground testing fully replicates the radiation environment, the thermal environment, the micrometeor environment, or the psychological environment of deep space. You have to go there to truly validate that your systems work.

Crew operations validation: Artemis II demonstrates that human crew can operate effectively in cislunar space. By March 2026, it will have been 54 years since humans last ventured beyond low Earth orbit. Things have changed. Life support systems are better. Communication systems are better. Navigation systems are better. Medical countermeasures are better. But you still need to prove it works.

Landing site reconnaissance: The crew will spend several days in lunar orbit, imaging potential landing sites for future missions. This reconnaissance will inform the selection of specific landing locations for Artemis III and subsequent surface missions.

Technology demonstration: The mission includes various technology demonstrations and experiments designed to test equipment that might be used in future missions. These demonstrations are low-cost ways to gather data about how systems perform in the actual lunar environment.

International partnership demonstration: The crew includes astronauts from multiple nations. Jeremy Hansen is Canadian. This demonstrates NASA's commitment to international partnership in lunar exploration. Future Artemis missions are expected to include astronauts from allied nations.

All of this points to something important: Artemis II isn't just about getting four people to the Moon and back. It's about establishing patterns, validating systems, and creating capabilities that will be used for decades.

That's why the March 6 target date matters. It's not just about when humans will next leave Earth orbit. It's about when NASA can credibly move forward with the next phases of its lunar strategy.

Estimated data shows the probability of a successful launch attempt on available dates in March 2026. March 6 is the earliest opportunity with the highest probability.

Risk Factors That Could Still Delay the Mission

For all the success of Thursday's test, multiple risk factors could still delay the launch past March 6.

Weather: Kennedy Space Center's location in Florida means dealing with Atlantic weather patterns. March is historically a better month than February for launch weather, but Atlantic systems can still develop. If a major weather system threatens the launch window, NASA can use backup dates (March 7, 8, 9, 11), but those fill quickly. If March weather fails, April becomes the next option.

Data analysis findings: Engineers are still processing 30 million-plus data points from Thursday's test. If analysis reveals issues, that could trigger additional tests, additional fixes, and additional schedule delay. The culture at NASA has evolved to where schedule delay is preferable to launching with unresolved technical issues.

Vehicle processing issues: Between now and launch day, Orion and SLS undergo extensive processing at Kennedy Space Center. Workers inspect hardware, replace consumables, conduct servicing, and perform final integration activities. If processing uncovers issues, that triggers additional work.

Crew medical issues: The flight crew undergoes regular medical evaluations to ensure readiness. While serious medical issues are unlikely given the crew's baseline health and the routine monitoring, spaceflight medicine can sometimes reveal unexpected issues. NASA has backup crew members trained, but a crew swap would require additional time.

Contractor readiness issues: SLS has multiple major contractors, and each contractor has supply chains and subcontractors. If any of those organizations encounters issues delivering hardware or services on schedule, that could affect launch readiness.

Range infrastructure problems: Kennedy Space Center's launch range infrastructure includes communication systems, tracking systems, safety systems, and other critical support equipment. If any of that infrastructure requires repairs or upgrades, that could affect launch readiness.

Mission rule changes: NASA has formal mission rules that define how the organization will respond to various technical issues or environmental conditions. If mission rule reviews, conducted as part of launch certification, identify new requirements or new restrictions, that could affect launch readiness.

None of these are likely to occur, based on current information. But spaceflight is an undertaking where multiple things have to go right. Any single thing going wrong has the potential to cause delay.

Looking Ahead: The Road to Artemis III and Beyond

Artemis II's March 6 target date is notable primarily because it unblocks the path to Artemis III and beyond.

Assuming a successful Artemis II mission, NASA's plan is to launch Artemis III in late 2026 or early 2027. Artemis III will include a lunar landing—the first human lunar landing since Apollo 17 in 1972. The plan is to land four astronauts on the Moon's south pole, with two crew members spending multiple days conducting surface operations.

Artemis III faces its own risks and challenges:

- The lunar lander needs to be developed, tested, and certified as human-rated. SpaceX's Starship is the current primary contractor, with Blue Origin providing a backup.

- EVA spacesuits for lunar operations need to be completed and qualified. Current development is on an aggressive timeline with risk.

- The Artemis III mission architecture is complex, involving multiple spacecraft and multiple rendezvous operations. Each adds operational complexity and risk.

- Landing on the Moon's south pole presents unique challenges related to lighting (the south pole experiences continuous darkness in certain areas), thermal environment, and terrain.

Beyond Artemis III, NASA is planning a series of follow-on missions that would establish a more sustained lunar presence. These missions would include:

- Extended surface operations: Longer-duration lunar surface missions with more crew members and more extensive equipment

- Lunar base infrastructure: Development of habitats, power systems, and other infrastructure to support sustained operations

- In-situ resource utilization: Systems to extract and use lunar resources (water ice, regolith) in support of local operations

- Science objectives: Expanded scientific investigations including geology, geophysics, biology, and other disciplines

All of this flows from successful Artemis II and Artemis III missions. Each mission provides experience, validates systems, and builds confidence for more ambitious follow-on missions.

The schedule shown by NASA assumes Artemis IV around 2028-2029, with subsequent missions following at intervals. But those dates are notional. The actual schedule will depend on how Artemis II and III missions execute, what unexpected issues emerge, and how industrial base capability evolves.

The Human Element: Why This Mission Resonates

Artemis II is a complex engineering undertaking involving millions of components, thousands of people, and billions of dollars. But at its core, it's a human mission.

Four people will travel to the Moon. For nine days, they'll be farther from home than any humans have been in 54 years. They'll see the far side of the Moon. They'll see Earth rising over the lunar horizon. They'll experience sensations and emotions that are beyond normal human experience.

That resonates with people at a visceral level. We're a species that explores. We're drawn to frontiers. There's something profound about pushing beyond our current boundaries.

Artemis II represents that impulse. It's not a practical mission in the sense that it doesn't generate immediate economic value or solve pressing problems on Earth. It's not even necessary for establishing a sustained lunar presence (that could be done with uncrewed missions and robotic systems).

But it is profound. It says to the world: we can do difficult things. We can dream big and execute on those dreams. We can send humans beyond our immediate sphere and bring them home safely.

That's worth doing. That's worth the complexity, the risk, the schedule pressure, and the cost.

The March 6 launch date isn't just a technical milestone. It's a symbol that humanity is ready for the next chapter of deep-space exploration.

FAQ

What is the Space Launch System and why is it so important?

The Space Launch System (SLS) is NASA's new heavy-lift launch vehicle designed to carry humans and cargo to deep-space destinations like the Moon and Mars. It's the most powerful operational rocket in the world, with the ability to lift approximately 70 metric tons to trans-lunar injection. The SLS is essential to NASA's Artemis program because no commercial rocket currently has the capability to perform the Artemis II mission profile.

Why did the first fueling test fail and what was the fix?

The first fueling test on February 2 failed because hydrogen leaked from the connection where liquid hydrogen flows from the launch platform into the SLS core stage. Hydrogen sensors detected concentrations exceeding NASA's safety limit of 16 percent, forcing the test to be aborted. NASA identified the seals on the fueling umbilical as the likely cause and replaced them with new seals before conducting the successful test on February 20.

What makes hydrogen leaks such a persistent problem in rocket operations?

Hydrogen is an extremely small molecule that easily evaporates from cryogenic systems. The seals that prevent hydrogen leakage must function at temperatures near negative 423 degrees Fahrenheit, an extreme environment that challenges material properties and thermal compatibility. Additionally, repeated thermal cycling can degrade seals over time. These factors combine to make hydrogen leak management one of the most challenging aspects of rocket operations.

How many days will the Artemis II mission take, and what are the main phases?

The Artemis II mission will last between nine and ten days. The main phases are trans-lunar coast (roughly three days), lunar orbit operations in distant retrograde orbit (several days), return trajectory (roughly three days), and Earth entry and splashdown. The crew will not land on the Moon during Artemis II; that mission profile is reserved for Artemis III.

What qualifications do the Artemis II crew members have?

The crew consists of highly experienced astronauts. Commander Reid Wiseman and Pilot Victor Glover are both Navy test pilots with prior spaceflight experience. Mission Specialist Christina Koch has logged nearly 330 days in space across multiple expeditions. Mission Specialist Jeremy Hansen is a Canadian fighter pilot and astronaut making his first spaceflight. Collectively, the crew has over 500 days of prior spaceflight experience.

What are the main risks that could cause the March 6 launch date to slip?

Potential risks include adverse weather in the Kennedy Space Center area, unexpected findings during data analysis of Thursday's test, issues discovered during vehicle processing, crew medical issues, contractor readiness problems, range infrastructure problems, or changes to mission rules. Any of these factors could trigger additional testing or work that would cause launch delay.

How does Artemis II relate to NASA's broader lunar exploration strategy?

Artemis II is a crucial validation mission for systems and procedures that will be used in Artemis III and subsequent lunar missions. The mission will provide critical data about how SLS, Orion, and crew perform in the deep-space environment. It will also conduct reconnaissance of potential landing sites for future surface missions and demonstrate sustained human presence in cislunar space. All of this builds confidence for more ambitious follow-on missions.

Why is the distant retrograde orbit used for Artemis II instead of a traditional circular lunar orbit?

The distant retrograde orbit offers several advantages: it's dynamically stable (requiring minimal fuel to maintain), it's far enough from the Moon that Earth radiation belts don't significantly affect the spacecraft, it provides good vantage points for landing site reconnaissance, and it requires less energy to reach than traditional lunar orbits. These advantages make DRO ideal for missions that need to loiter near the Moon for extended periods.

Conclusion: A Mission That Changes Everything

When NASA announces that Artemis II is targeting March 6 for launch, that date carries symbolic weight that extends far beyond a calendar marking.

It means that the most powerful rocket ever built is ready to fly. It means that human-rated deep-space spacecraft systems are validated and ready. It means that four extraordinarily trained astronauts are ready to undertake one of the most significant space journeys in human history. It means that a global infrastructure spanning Kennedy Space Center, contractor facilities across the country, and mission support networks is aligned and ready to execute.

It means that humanity is returning to deep space.

The journey to March 6 has been longer than anyone anticipated. Technical challenges, schedule pressures, budget constraints, and the simple complexity of building and operating systems at the cutting edge of human capability have all contributed to delays. But those delays, frustrating as they were, reflect the seriousness with which NASA approaches human spaceflight.

Thursday's successful fueling test was a major milestone. The hydrogen seals held. The countdown proceeded smoothly. The launch team executed with precision. All of that points toward a mission that's ready to fly.

But Lori Glaze's caveat remains important: there's still pending work. Data analysis continues. Secondary issues need resolution. Vehicle processing continues. Launch readiness certification continues. All of these activities have to complete successfully for March 6 to be the actual launch date rather than a target date.

Still, the momentum is unmistakable. The excitement is real. The confidence is warranted.

Artemis II is coming. In all likelihood, whether in March or shortly thereafter, the SLS rocket will light up on the Florida coast, carrying Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen on a journey to the Moon.

For the first time since 1972, humans will travel beyond low Earth orbit. For the first time in 54 years, human footprints will approach the Moon. For the first time in a generation, the world will witness the kind of human spaceflight accomplishment that inspires awe and reminds us of what we're capable of.

That's why the March 6 target date matters. It's not just about launching a rocket. It's about humanity taking the next step in its oldest journey: the exploration of new frontiers.

The hydrogen seals held on Thursday night. The path forward is clear. The countdown, in a real sense, has already begun.

Key Takeaways

- NASA successfully conducted Artemis II fueling test on February 20 with hydrogen concentrations at 1.6% versus 18.5% during failed February 2 test, validating seal replacement fix

- March 6, 2026 launch target requires completing data analysis, avionics verification, vehicle processing, and crew certification with backup launch dates March 7, 8, 9, and 11

- Four-person crew (Wiseman, Glover, Koch, Hansen) with over 500 combined spaceflight days will journey to distant retrograde orbit 40,000 miles from Moon in nine to ten day mission

- Hydrogen seal management remains ongoing challenge in spaceflight due to extreme cryogenic temperatures (-423°F) and small hydrogen molecules requiring precision Teflon seals

- Artemis II success directly enables Artemis III landing mission targeting 2026-2027, making this validation mission critical to NASA's sustainable lunar exploration strategy

Related Articles

- Artemis 2 Moon Mission: NASA's Historic 2025 Launch [2025]

- NASA's Fraggle Rock Space Adventure: Muppets Meet Moon Exploration [2025]

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Bring Smartphones to the Moon [2025]

- NASA SpaceX Crew-12 ISS Docking: Complete Mission Guide [2025]

- Bezos vs Musk: The Race Back to the Moon [2025]

- SpaceX Super Heavy Booster Cryoproof Testing Explained [2025]

![NASA Artemis II Launch: March 6 Target After Successful Fueling Test [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-artemis-ii-launch-march-6-target-after-successful-fueli/image-1-1771632437152.jpg)