The Search for Alien Artifacts Is Coming Into Focus [2025]

Here's the thing about alien artifacts: we've been thinking about them for decades, but we've never had a coherent strategy to actually look for them. That's changing. Fast.

For generations, the hunt for extraterrestrial life focused on one narrow channel: radio signals. Scientists would point massive dishes at the stars hoping to catch some cosmic broadcast, some undeniable proof that someone out there was trying to talk to us. It made sense. Radio travels far. It's cheap. And it fit neatly into the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI, a field that's been respectable enough to secure funding and university positions.

But radio signals leave no physical evidence. They're ephemeral. A signal can vanish before you even know it arrived. What if, instead of shouting across the void, an advanced civilization sent physical emissaries? Robots. Probes. Artifacts. Technology we could actually hold and study.

For decades, that idea lingered in the margins of serious science, treated as something between a thought experiment and science fiction. Then something shifted. The discovery of interstellar objects passing through our solar system, the emergence of new detection technologies, and a growing cohort of researchers willing to ask uncomfortable questions have transformed alien artifact research from taboo speculation into legitimate scientific inquiry.

This isn't about flying saucers landing on the White House lawn. It's about rigorous methodology applied to an unconventional question: What if we've been looking in the wrong place the whole time?

TL; DR

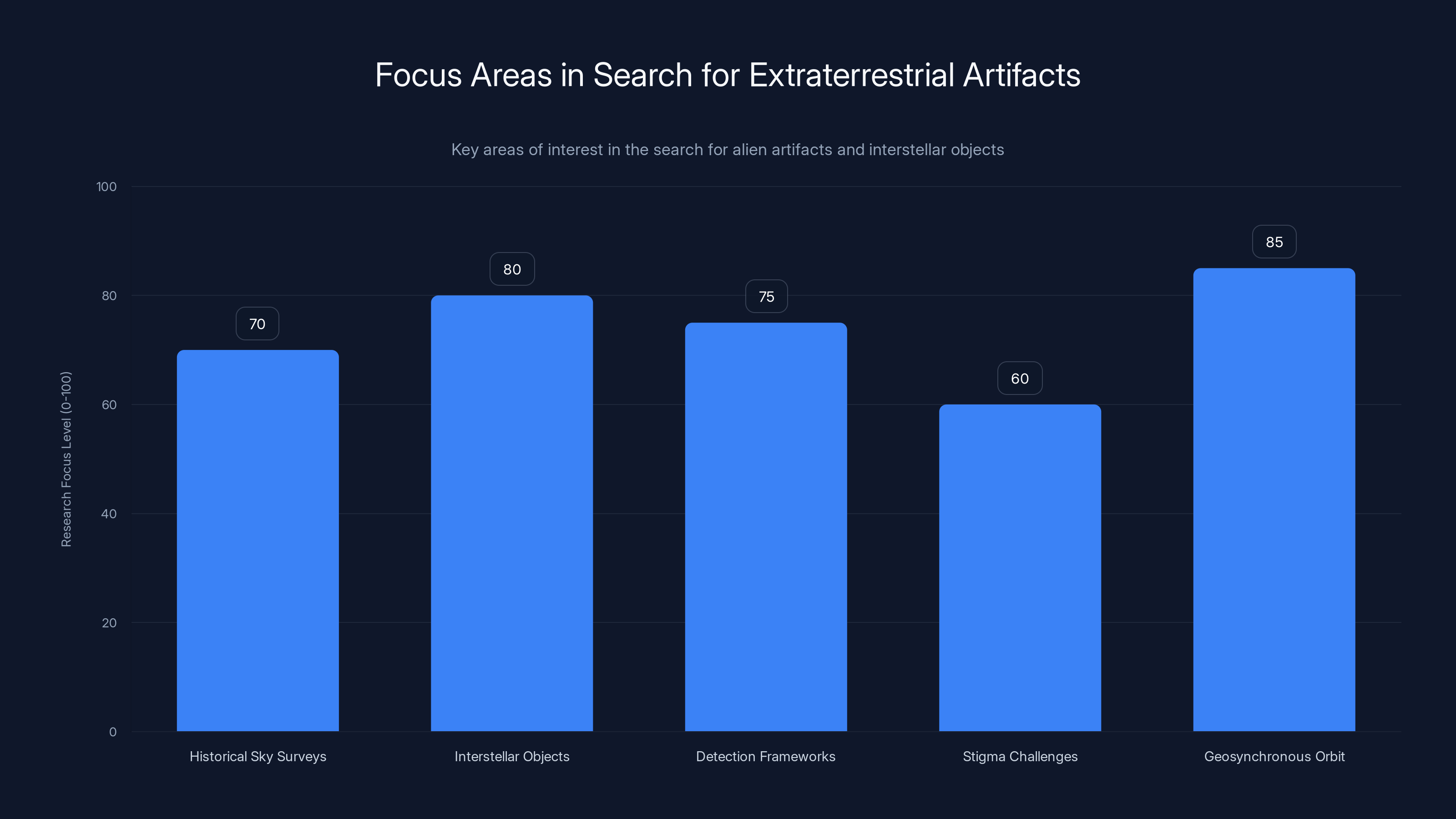

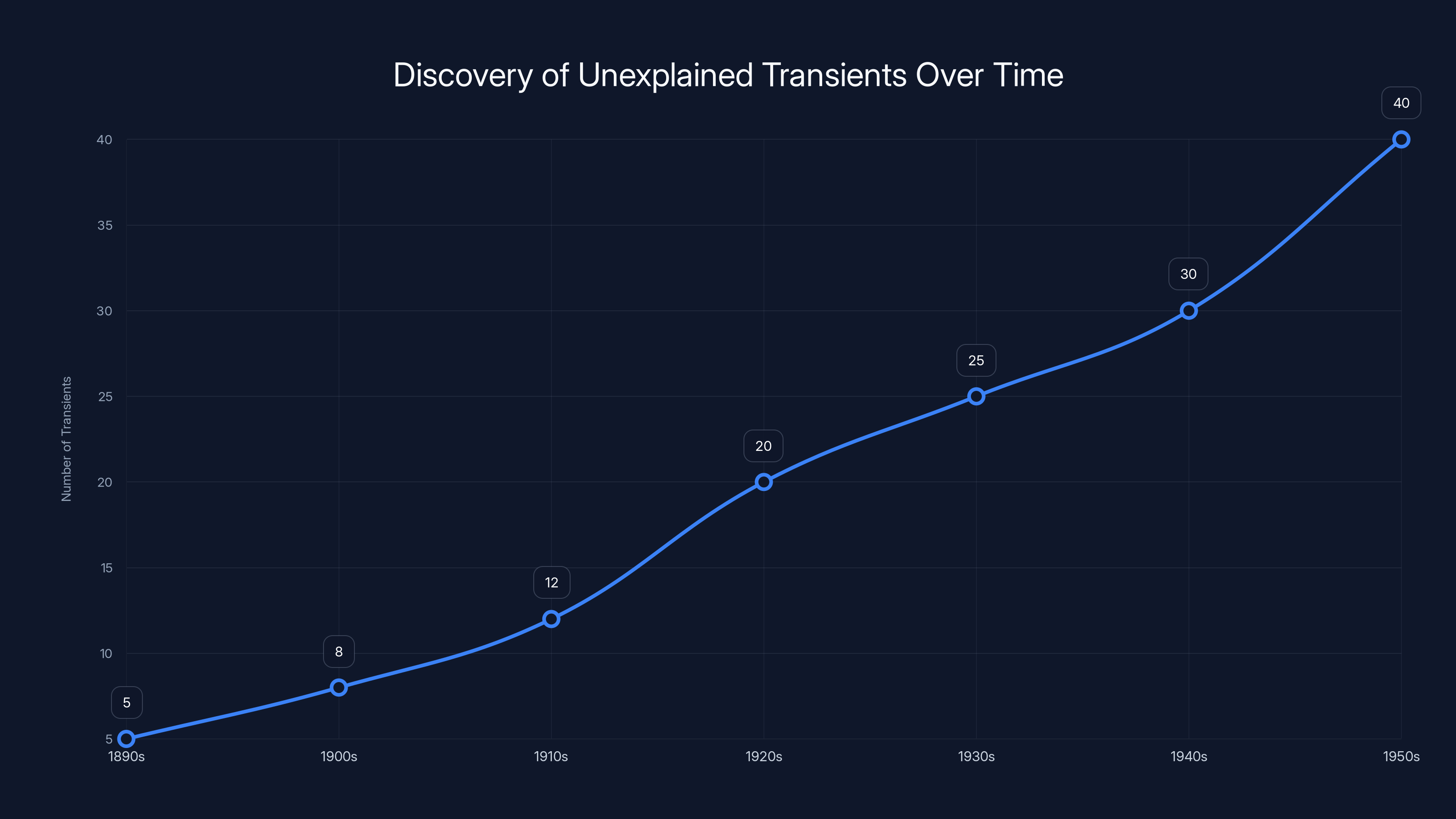

- Scientists are searching for alien artifacts using historical sky surveys: Researchers analyzing pre-1957 photographs have identified unexplained transient objects that could represent artificial satellites predating human spaceflight

- Interstellar objects have become legitimate research focus: Three confirmed interstellar visitors (1I/'Oumuamua, 2I/Borisov, and 3I/ATLAS) have generated serious scientific debate about whether some could be technological probes

- New detection frameworks are emerging: The field of SETA (Search for Extraterrestrial Artifacts) has evolved from theoretical physics into practical observational astronomy with specific methodologies and criteria

- Stigma remains a significant barrier: Despite rigorous methodology, researchers face resistance from the scientific establishment due to historical associations with fringe theories

- Geosynchronous orbit is now a focus area: Earth's orbital neighborhood, particularly the region 22,000 miles up, is being reconsidered as a potential repository for alien technology

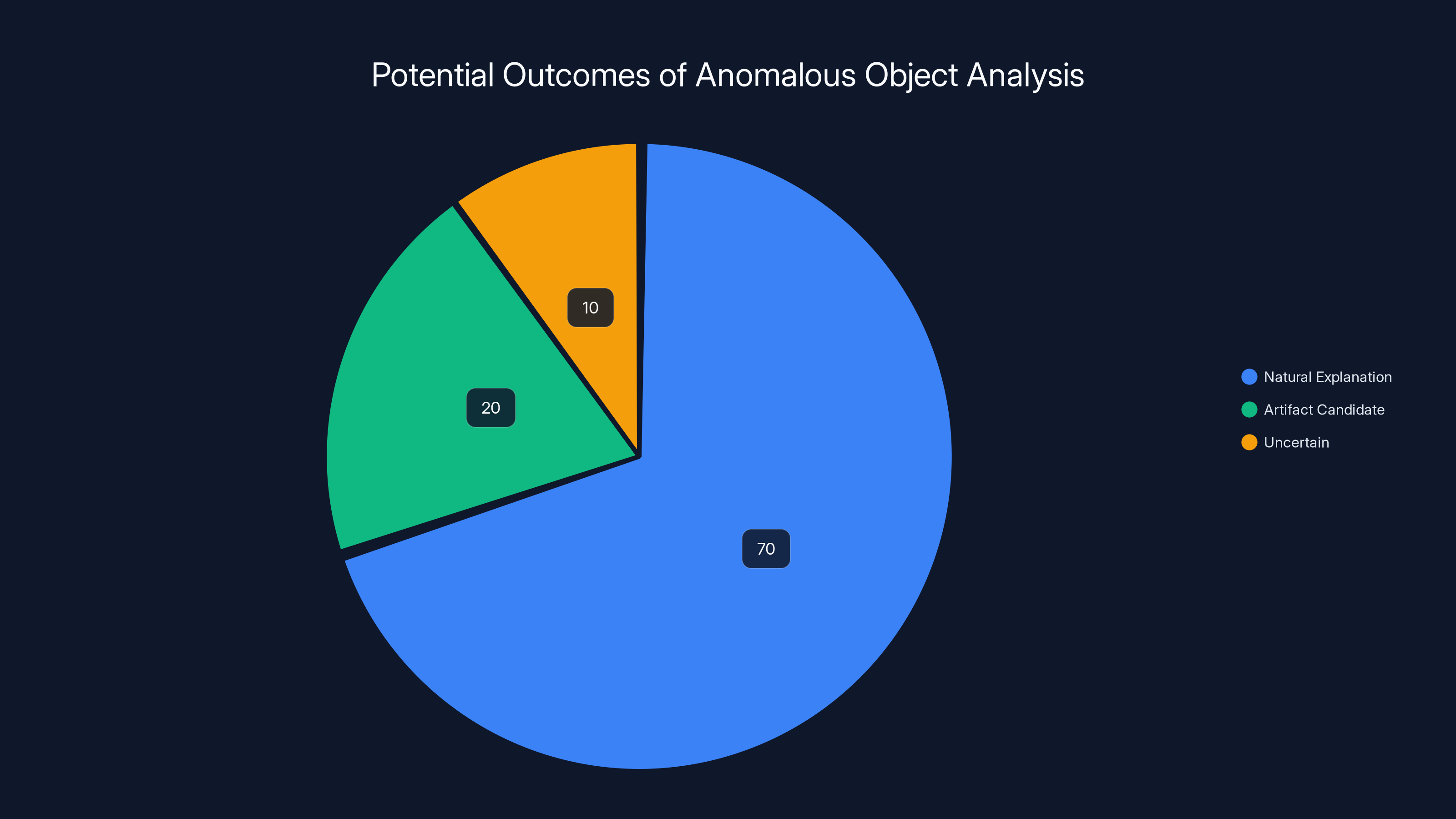

Estimated data suggests that most anomalies are explained naturally, with a smaller percentage remaining as artifact candidates or uncertain.

The Long History of Thinking About Artifacts

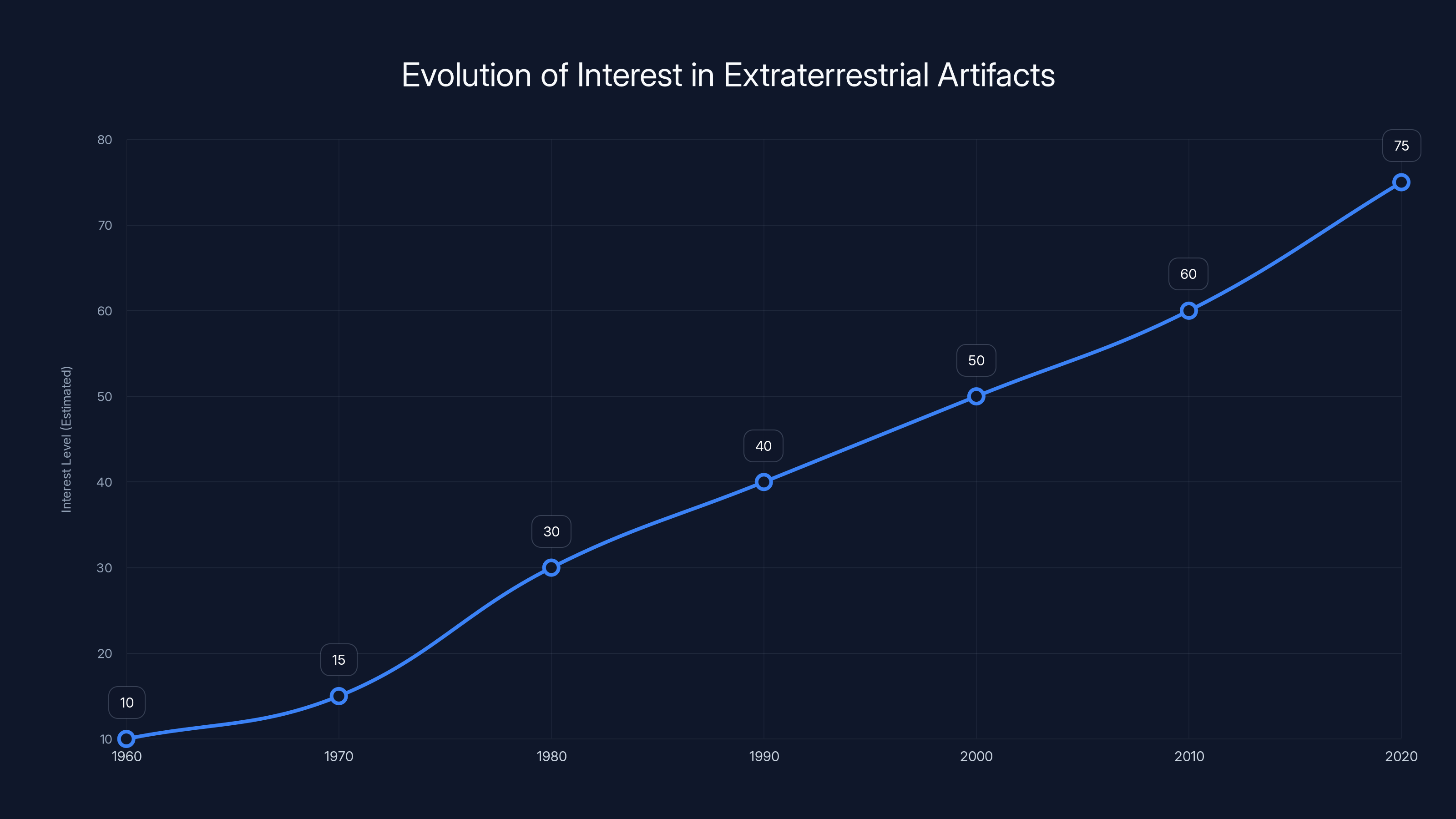

The concept of searching for physical artifacts from alien civilizations didn't emerge yesterday. It's been lurking in the scientific literature since the early space age, waiting for someone brave enough to take it seriously.

Back in 1960, physicist Ronald N. Bracewell published a speculative paper in Nature proposing something that would come to be called Bracewell probes. The idea was elegant and counterintuitive: if you wanted to explore the galaxy efficiently, why send manned expeditions or constantly transmit signals? Instead, send self-replicating robotic scouts. They could travel at a fraction of the speed of light, explore multiple star systems, and remain in place for potentially millions of years, ready to communicate when intelligent life emerged in a system.

It was brilliant thinking, but it remained theoretical. Pure speculation without observational grounding.

Then came 1985. Two researchers, Robert A. Freitas Jr. and Francisco Valdes, published a seminal paper in Acta Astronautica that formally established the search for extraterrestrial artifacts as a legitimate subset of SETI research. They called it SETA, and they outlined compelling reasons why an advanced civilization might choose to send physical probes rather than rely on radio.

Their key insight was simple but powerful: radio signals are fleeting. An artifact could engage in sustained, complex communication with a newly emerging civilization. It could adjust its strategy based on what it learned. It could be a true conversation, not just a broadcast that may or may not be heard.

But here's what's crucial to understand: this theoretical work existed almost entirely in the abstract. There were no real observations, no candidates, no data points to analyze. SETA research was philosophy masquerading as science.

What changed was the arrival of ground truth. Real, tangible objects from beyond our solar system began appearing in our cosmic neighborhood, and suddenly the theoretical became observational.

Interstellar Visitors: The First Concrete Evidence

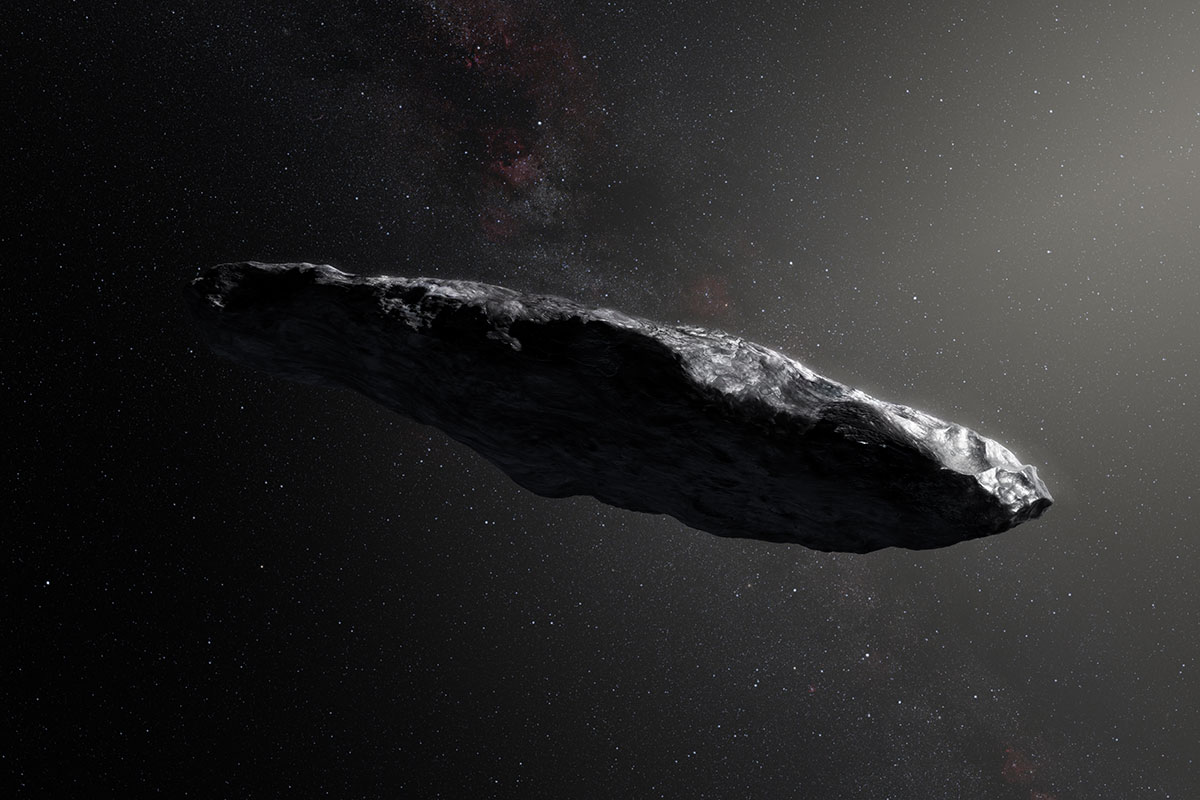

In October 2017, something extraordinary happened. A telescope in Hawaii called Pan-STARRS detected an object moving through space at an unusual velocity and trajectory. Astronomers quickly calculated its orbit and realized something shocking: this object wasn't from our solar system. It came from somewhere else in the galaxy.

They named it 1I/'Oumuamua, derived from Hawaiian words meaning "a messenger from afar arriving first." The name was poetic, but the scientific reality was even more fascinating: this was the first confirmed interstellar object ever discovered passing through our solar system.

Oumuamua was roughly 400 meters long, shaped like a cigar or a pancake (measurements remain somewhat uncertain), and it accelerated as it approached the sun in ways that couldn't be easily explained by solar radiation pressure alone. Some of its characteristics were unusual enough that researchers published hundreds of papers speculating about its nature. Most concluded it was a comet or asteroid. But a vocal minority, including Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb, suggested that its acceleration and trajectory could indicate artificial propulsion.

The mainstream scientific community was skeptical, as they should be. The bar for extraordinary claims requires extraordinary evidence, and Oumuamua's behavior, while unusual, could be explained by conventional physics. But the psychological effect was significant. We had proof that interstellar objects could and did pass through our solar system. We weren't just imagining a possibility anymore.

Two years later, in 2019, a second interstellar object was discovered: 2I/Borisov. This one was even more interesting because it was clearly a comet, with a visible coma and tail. Its brightness, composition, and behavior all suggested a relatively conventional icy body from elsewhere in the galaxy. But again, it proved the principle: the solar system receives visitors from beyond.

Then in 2025, a third interstellar object was detected and designated 3I/ATLAS. Each discovery reinforced the same reality: the galaxy is an active place. Objects move through space. We can detect them. And if natural objects can arrive from distant star systems, so theoretically could artificial ones.

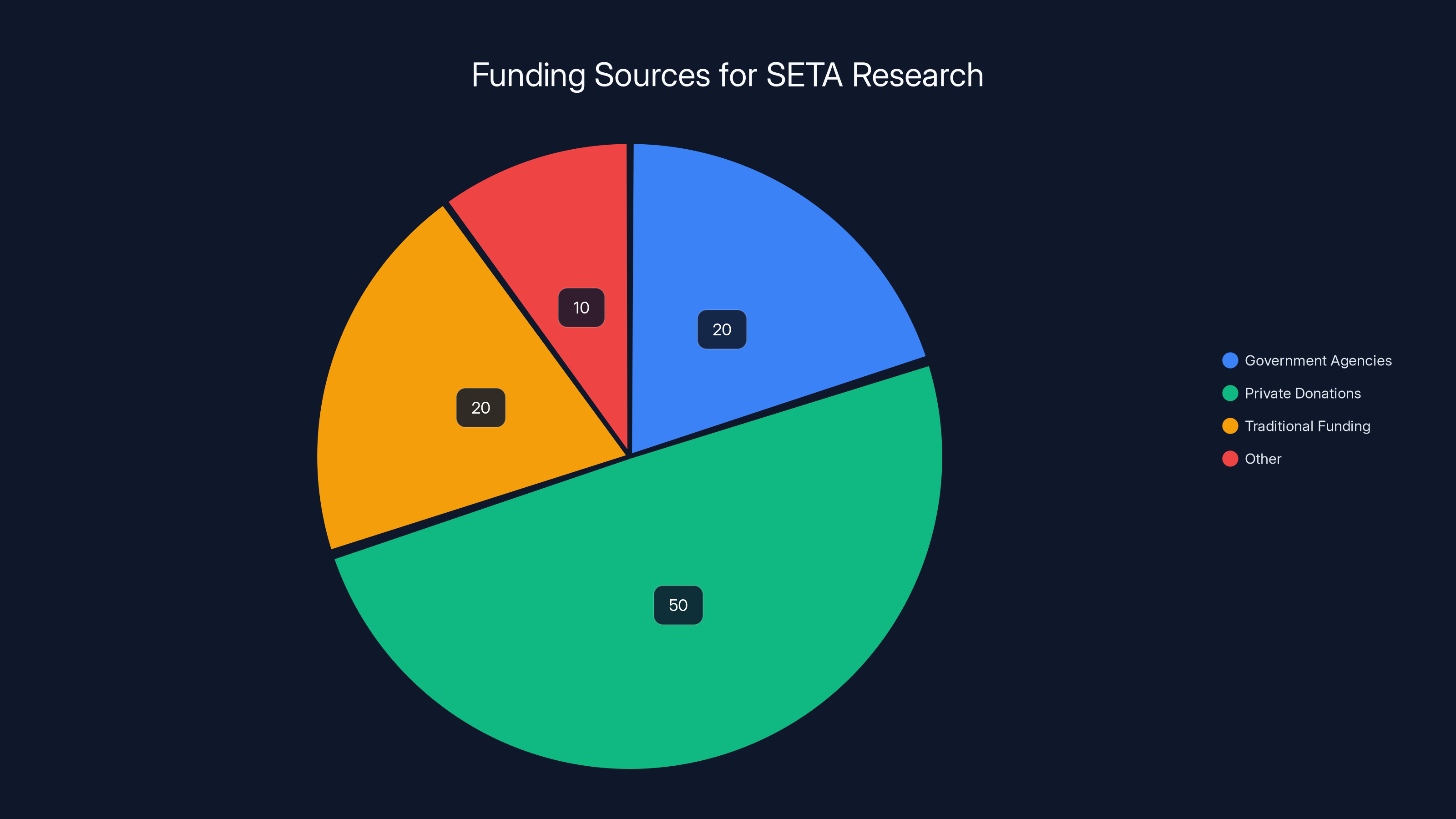

Private donations constitute the largest portion of funding for SETA research, highlighting reliance on non-traditional sources. Estimated data.

The Archival Sky Survey: Looking Backward Into the Future

While most researchers focused on interstellar objects entering our solar system from outside, one astronomer had a different idea. What if alien artifacts were already here, placed long ago, waiting to be discovered? And what if the evidence existed not in current observations but in historical photographs gathering dust in archives?

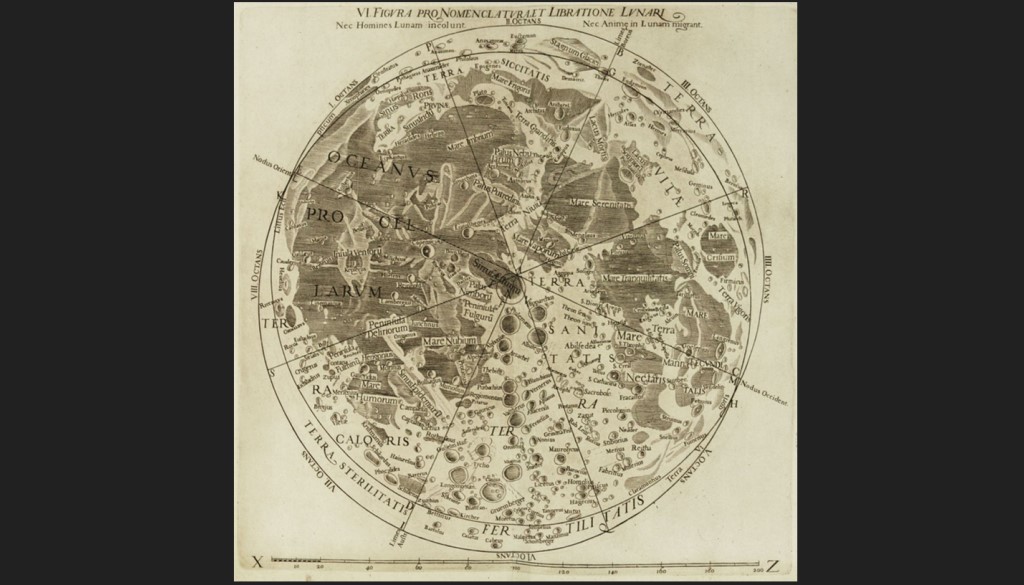

Beatriz Villarroel, an assistant professor at the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics, began thinking about something most astronomers overlooked: the photographic plates captured by telescopes before the space age. From the 1890s through the 1950s, astronomers systematically photographed the sky, creating an unprecedented visual record of celestial objects and events.

These images were taken before Sputnik launched in 1957, before humanity began filling orbit with its own satellites. They captured a pristine sky, relatively free from artificial objects. In theory, that made them perfect for spotting things that didn't belong, including potential alien artifacts.

Villarroel leads the Vanishing & Appearing Sources during a Century of Observations project, or VASCO. The original goal was to identify stars and other celestial objects that had disappeared from the sky between old observations and modern ones. But as she and her team dug through the archives, something interesting emerged.

They found transient objects that appeared in some old photographs but not in others. These objects looked, on closer inspection, exactly like artificial satellites. The problem was simple and profound: no artificial satellites existed when these photographs were taken.

In 2021, Villarroel and her colleagues published their findings, identifying dozens of these unexplained transients in pre-Sputnik observations. The work generated immediate controversy. Skeptics offered alternative explanations: instrumental errors, dust on the photographic plates, meteors, cosmic rays, artifacts of the photographic process itself.

But Villarroel didn't back down. She and her team published three additional studies in prestigious journals including the Publications of the Astronomy Society of the Pacific and Scientific Reports, continuing to investigate these anomalies and refine their analysis.

The work was rigorous. The findings were real: there were objects in the historical record that didn't fit neat categories. Whether they represented alien artifacts, previously unknown natural phenomena, or measurement errors remained unresolved. But the fact that mainstream journals were publishing this research represented a sea change in the field's respectability.

Geosynchronous Orbit: Our Backyard of Potential Discoveries

If you wanted to observe Earth while remaining stationary relative to one location on the planet's surface, you'd place a satellite in geosynchronous orbit, roughly 22,000 miles above the equator. At that altitude, an object's orbital period matches Earth's rotation, so it hovers above the same spot permanently.

Geosynchronous orbit is crowded with human satellites, communication systems, weather stations, and military assets. But what if something else was up there? Something that arrived not from Florida or Kazakhstan but from another star system?

The logic is sound. A geosynchronous orbit provides several advantages for an observer or probe. It's far enough from Earth to avoid immediate atmospheric drag. It offers a stable vantage point. It's protected by Earth's magnetosphere from much of the solar wind. And crucially, objects in geosynchronous orbit follow predictable paths, making them easier to locate and monitor.

Villarroel has suggested that a dedicated mission to image geosynchronous orbit thoroughly could resolve some of the mysteries identified in the archival plates. Such a mission would be relatively straightforward from a technical perspective. Send up a probe, image the entire geosynchronous belt, compare results to historical data and theoretical models of what natural objects should be there.

But here's where the politics become crucial. Space agencies are unlikely to fund such a mission in the near term. Why? Because the entire enterprise remains controversial. Funding a mission explicitly to search for alien artifacts, regardless of its scientific merit, exposes agencies to ridicule from both the public and the scientific establishment.

Villarroel has been remarkably candid about this obstacle. "There's so much taboo that nobody's ever going to take such results seriously until you bring down such a probe," she's noted. In other words, we need the physical evidence. We need to capture something and analyze it directly. But we won't fund a mission to capture it until we have stronger preliminary evidence. It's a catch-22 that highlights how stigma can slow scientific progress even when the methodology is sound.

The Stigma Problem and Why It Matters

Let's address the elephant in the room: searching for alien artifacts carries serious stigma in mainstream science.

Part of this comes from history. The field's fringes have attracted UFO enthusiasts, pseudoscientists, and people eager to find evidence of extraterrestrial intervention in human affairs. Area 51, Roswell, ancient astronaut theories—all of this baggage hangs over legitimate research into extraterrestrial technology.

But another part of the problem is more subtle. Science has a hierarchy of respectability. Some questions are considered serious; others are considered a waste of resources. Searching for alien artifacts has traditionally fallen into the second category. Researchers who devoted significant time to the question could find their careers affected. Funding committees might pass. Journal editors might reject papers more readily.

Adam Frank, an astrophysicist at the University of Rochester, has been thinking about these issues for years. He recognizes the stigmatization as real and counterproductive. But he also sees something encouraging happening: the scientific back-and-forth is finally occurring in reputable venues.

"This is how science actually works," Frank has noted. "You publish a paper in a reputable journal, and now we can have the scientific back and forth." In other words, the mechanism for testing ideas, challenging claims, and moving toward truth is functional. Yes, some researchers remain skeptical about the archival data and Villarroel's interpretations. But that skepticism is expressed through peer review and published responses, not through dismissal.

That represents genuine progress. The question is no longer whether artifact searches are legitimate, but rather how to conduct them rigorously and what standards of evidence we should apply.

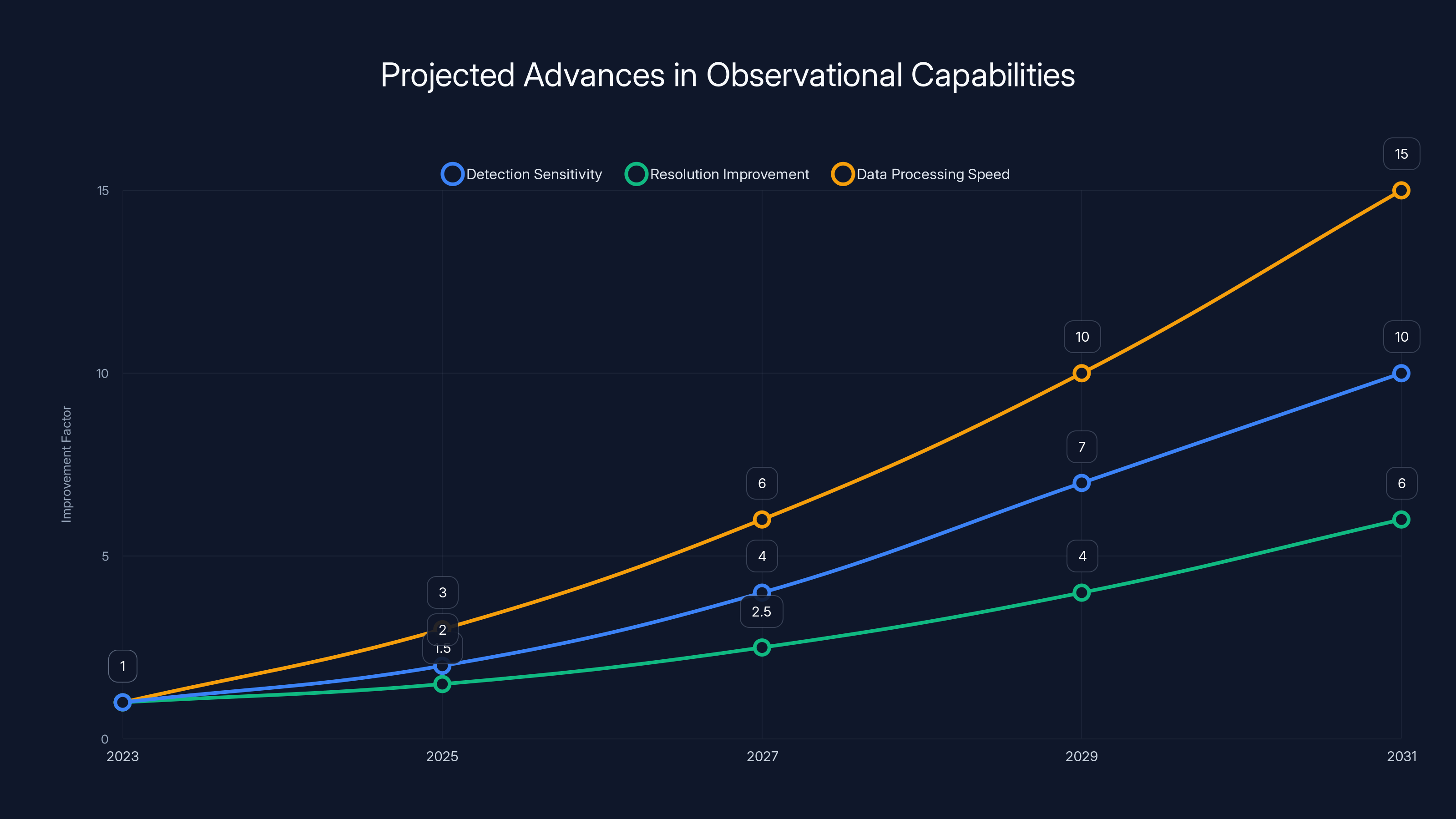

Estimated data shows significant improvements in detection sensitivity, resolution, and data processing speed over the next decade, enhancing the potential for artifact discovery.

Methodological Frameworks: How Scientists Now Search

As SETA research has gained legitimacy, researchers have developed specific frameworks and methodologies for conducting searches. These frameworks distinguish SETA from casual speculation by establishing clear criteria for what counts as a candidate object.

First, researchers establish baseline expectations. What natural objects should we expect to find in a given observational region? What are their typical velocities, compositions, and trajectories? By establishing these baselines, scientists can identify anomalies: objects that don't fit the expected patterns.

Second, researchers develop hierarchical classification systems. Not every unusual object is an artifact candidate. An object might be anomalous but still have natural explanations. SETA research typically creates categories: definitely natural, probably natural, possibly anomalous, probably artificial, definitely artificial. Most candidates never move beyond the "possibly anomalous" stage because conventional explanations eventually emerge.

Third, researchers establish criteria for what would constitute credible evidence. This is crucial. Before you can claim to have found something, you must specify in advance what evidence would convince you. This prevents confirmation bias and post-hoc rationalization.

Fourth, researchers integrate data from multiple sources and time periods. A single observation might be ambiguous, but if multiple independent observations from different telescopes, different time periods, and different analysis methods all point to the same conclusion, the case strengthens substantially.

These methodologies aren't unique to SETA research. They're standard scientific practice applied to an unconventional question. But the rigor is worth emphasizing because it distinguishes legitimate artifact searches from science fiction.

Interstellar Probes: The Bracewell Hypothesis Reconsidered

Ronald Bracewell's 1960 proposal that aliens might send autonomous robotic probes across the galaxy deserves deeper examination because it shapes how modern researchers think about what they should be looking for.

Bracewell's insight was based on simple economics and physics. Consider the challenge facing a space-faring civilization: the galaxy is vast. Traveling between stars takes centuries or millennia at any conceivable speed. Maintaining radio contact across such distances requires extraordinary energy. But if you send a self-replicating probe, it could explore multiple star systems and wait indefinitely for signs of emerging intelligence.

What would such a probe look like? Bracewell imagined something sophisticated: a spacecraft carrying advanced sensors, communication equipment, and most intriguingly, a manufacturing capability. Upon detecting intelligent signals, the probe would begin creating copies of itself. These copies would then spread to other star systems, creating a network of sentries monitoring the galaxy.

This might sound like science fiction, but the logic is sound. A probe doesn't need to be biological or organic. It could be entirely mechanical, potentially capable of operating for millions of years. It could be small and relatively inconspicuous, or it could be enormous and obvious. There's no way to know without looking.

Modern researchers have expanded on Bracewell's ideas. Some have speculated that an extremely advanced civilization might send probes disguised to look like natural objects. Others have suggested that probes might establish themselves in relatively stable orbital regions, such as the Lagrange points where gravitational forces balance, allowing an object to remain stationary relative to planets.

Still others have considered whether detectable signatures might emerge from the probe's operations themselves. A probe in geosynchronous orbit might need to occasionally adjust its position, creating detectable thruster firings. It might emit waste heat distinguishable from natural sources. It might broadcast test signals, even if those signals weren't deliberately aimed at Earth.

These are precisely the kinds of considerations that guide modern artifact searches. Researchers aren't just looking randomly; they're looking for things that advanced technology would predictably create.

Natural Object Explanations and When They Work

One critical aspect of rigorous SETA research involves honestly evaluating competing hypotheses. Most transient objects identified in archival surveys or anomalous interstellar visitors eventually receive conventional explanations.

Consider the alternative explanations offered for Villarroel's pre-Sputnik transients:

Instrumental errors represent a serious possibility. Photographic plates are imperfect. Dust, scratches, and manufacturing defects can create artifacts that look like objects. Cosmic rays striking the photographic emulsion can create tracks indistinguishable from real objects. Over millions of archival plates, some false signals are inevitable.

Atmospheric phenomena like meteors and fireballs could create brief, bright transients. A meteor entering the atmosphere, ionizing gases, and creating a brief flash would look superficially similar to a satellite. These events are common.

Nuclear testing created significant atmospheric effects during certain periods when several of Villarroel's pre-Sputnik transients were observed. The Starfish Prime test in 1962 created an artificial radiation belt visible to satellites and even bright enough to be seen from Earth. Earlier tests generated various atmospheric phenomena that might have been captured on photographic plates.

Debris and space weather events including coronal mass ejections and solar particle events could create anomalous signals in certain detection methods.

The key point is this: legitimate SETA research doesn't dismiss these alternatives. Instead, it systematically evaluates them. Researchers ask: if this transient was a meteor, what evidence would we expect to find? If it was an instrumental error, would the error show specific patterns? By working through these alternatives rigorously, scientists can rule out conventional explanations and identify true anomalies.

Sometimes, this process eliminates candidates entirely. The signal disappears. The explanation becomes clear. The science works as it should.

Geosynchronous orbit and interstellar objects are currently the most focused areas in the search for extraterrestrial artifacts, despite challenges like stigma. Estimated data based on topic emphasis.

The Geometry Problem: How Do You Search a 3D Universe?

One underappreciated challenge in SETA research is the sheer geometric difficulty of the task. The solar system is incomprehensibly vast. Even if you've identified a search region like geosynchronous orbit, you're dealing with an enormous volume of space.

Geosynchronous orbit occupies a shell about 22,000 miles above Earth's equator. The thickness of this shell where satellites typically operate is measured in hundreds of miles. The circumference of this orbit around Earth is approximately 89,000 miles. A simple calculation reveals that the geosynchronous belt encompasses roughly 8 billion cubic miles of space.

Now imagine trying to search that volume systematically. You could deploy satellites to image different regions, but doing so thoroughly would require an enormous armada of observational assets. You could use ground-based telescopes with sufficient resolution, but atmospheric distortion and limited viewing angles constrain what's possible.

More fundamentally, the search isn't just a geometric problem; it's a temporal one. You're not looking for a single object at a single moment. You're looking for a pattern that might have changed. An artifact that was present decades ago might have moved or been deactivated. An object visible under certain lighting conditions might be invisible under others.

This temporal dimension adds another layer of complexity. Researchers must integrate observations across time, accounting for orbital decay, seasonal brightness variations, and the movements of Earth, planets, and the Sun.

These geometric and temporal constraints are why researchers focus on promising regions rather than attempting exhaustive universal searches. Geosynchronous orbit is interesting because objects placed there would be relatively stable. Lagrange points are interesting because objects could remain in position with minimal fuel expenditure. Certain asteroid populations are interesting because they offer accessible materials for future observers.

Focusing the search makes the problem tractable. But it also means that artifacts could exist in unsearched regions, passing undetected indefinitely.

The Acceleration Problem: When Physics Becomes Fascinating

One persistent mystery from the interstellar objects is their acceleration as they approach the Sun. This seemingly technical detail has profound implications for how researchers think about identification criteria.

Oumuamua in particular showed an acceleration that couldn't be fully explained by solar radiation pressure alone. This is the core claim underlying some speculation that it might be artificial. But here's where the story gets more interesting: the measurements themselves have uncertainties, and different analysis methods give different results.

Some researchers, analyzing outgassing patterns and composition estimates, concluded that non-gravitational acceleration was within the range expected for a comet releasing frozen gases. In other words, it's fully explained by conventional physics if you account for outgassing that might not be directly observable.

Other researchers, including Avi Loeb, argued that the data didn't clearly support the outgassing hypothesis. They suggested that solar radiation or even more exotic physics might account for the acceleration. Some floated the possibility of solar sail technology: if Oumuamua had a large surface area relative to its mass, radiation pressure alone could accelerate it.

The fascinating part of this debate isn't whether Oumuamua is artificial. Most evidence suggests it's not. The fascinating part is how this seemingly technical question about physics becomes a test case for methodology. How do you evaluate competing explanations? What standard of evidence is sufficient? When should you accept the conventional explanation, and when should you look harder?

These questions matter beyond SETA research. They reflect how science progresses generally. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, but extraordinary evidence can hide within seemingly ordinary data if you're asking the right questions.

What an Actual Discovery Would Look Like

Imagine for a moment that researchers actually found convincing evidence of an alien artifact. What would that look like, and how would science respond?

The most straightforward scenario involves physical recovery. A small probe or artifact captured by a space mission would be brought back to Earth for analysis. Scientists would examine its composition, isotopic ratios, and structure. They would search for markings, inscriptions, or encoded information. They would try to reverse-engineer its function.

The verification process would necessarily be international and extremely rigorous. No single nation or organization could credibly authenticate such a discovery alone. Peer review would occur at the highest levels. Multiple independent laboratories would need to confirm findings. The burden of evidence would be extraordinary.

Interestingly, an authenticated artifact might resolve some questions while creating others. Knowing definitively that alien technology had reached Earth would answer the central question: we're not alone, and at least one civilization achieved spacefaring capability. But it would generate new questions: Where did it come from? How long has it been here? Is it still active? What can we learn from its design?

Scientific response would likely be more muted than popular culture suggests. There wouldn't be panic or dramatic governmental announcements necessarily. Instead, there would be intense, focused research. Grants would suddenly flow to SETA research. Universities would establish programs. The question would shift from "Is this possible?" to "How do we understand this phenomenon?"

The social and political implications would dwarf the scientific ones. A confirmed alien artifact would fundamentally reshape how humanity understands itself. We would know that intelligence emerges elsewhere in the galaxy. We would know that some civilization achieved the capability to send probes across interstellar distances. We would know that we're being observed or had been observed at some point in the past.

These knowledge items would transform philosophy, theology, social policy, and international relations in ways that are almost impossible to predict.

Interest in extraterrestrial artifacts has grown steadily since the 1960s, with key publications in 1960 and 1985 marking significant milestones. Estimated data.

The Conference Effect: How Ideas Spread and Gain Legitimacy

Another indicator of SETA's increasing legitimacy is the emergence of dedicated conferences and symposia focused on technosignatures and artifact searches. These events bring together researchers from astronomy, physics, engineering, and other fields to present findings, debate methodologies, and plan future research.

Conferences serve crucial functions in science. They create venues for presenting preliminary results that might not yet be ready for publication. They allow researchers working on similar problems from different institutions to find each other and collaborate. They generate citations and citations generate legitimacy. Journal editors who see that a topic has generated multiple presentations at prestigious conferences become more likely to accept papers on that topic.

Over the past five years, the number of papers on technosignatures and artifact searches presented at major conferences has grown substantially. This might seem like a minor metric, but it's actually important. Conference presentations indicate that researchers are moving beyond purely theoretical work into applied research with testable hypotheses.

These conferences also serve a therapeutic function for researchers who've faced skepticism. Sharing space with colleagues working on similar problems, hearing their strategies and findings, reinforces that this research is legitimate and important. It reduces the isolation that can occur when working on minority topics within one's field.

The conference effect also influences funding. Grant agencies pay attention to conference presentations when evaluating proposals. If they see that a topic has generated substantial academic interest and rigorous research, they become more likely to fund work in that area.

Funding Challenges and the Research Pipeline

Despite growing interest, funding for SETA research remains limited. Government space agencies and traditional funding sources are reluctant to invest heavily in artifact searches, partly due to the stigma but also due to practical concerns about research direction and probability of success.

This has driven some researchers toward private funding. Avi Loeb's Galileo Project, for instance, is funded through private donations rather than government grants. While private funding provides freedom to pursue unconventional research directions, it creates different constraints. Private funders may have specific interests or ideologies. They may expect results on particular timelines. They may withdraw support if results aren't forthcoming.

The funding situation also affects who can conduct research. Established researchers with secure positions can afford to explore minority interests. Early-career researchers typically cannot. A graduate student or postdoc devoting significant time to artifact research would likely damage their career prospects, as the field remains lower status than mainstream astronomy or cosmology.

This creates a pipeline problem. Without younger researchers entering the field, there's no guarantee of continuity. The people currently working on these questions are often midcareer or established. In 20 years, will younger researchers have been trained to continue this work? Or will the field stagnate as current researchers retire?

Some institutions and funding agencies are beginning to recognize this problem and are trying to address it by explicitly supporting high-risk, unconventional research. But systemic change in how academic science evaluates and funds research questions remains slow.

Future Observational Capabilities and Detection Horizons

The next decade promises significant advances in observational capabilities that could transform artifact searches. Next-generation telescopes will offer unprecedented sensitivity and resolution. Distributed sensor networks will enable systematic sky surveys at unprecedented scales. Space-based observatories will provide capabilities unattainable from Earth's surface.

The Vera Rubin Observatory, now under construction in Chile, will conduct an automated survey of the southern sky, cataloging billions of objects and identifying transients automatically. This capability will generate an enormous database of archival photographic observations in digital form, making them available for SETA analysis.

Space telescopes operating in infrared wavelengths will detect faint thermal signatures that visible-light telescopes would miss. An artificial satellite or probe might be invisible in visible light but detectable through its waste heat.

Gravitational wave detectors might eventually achieve sensitivity sufficient to detect the thruster firings or other large-scale events of extremely advanced spacecraft. This sounds speculative, but the principle is sound.

Most intriguingly, advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning are being applied to sift through enormous datasets. Rather than humans visually inspecting millions of images or spectra, AI systems can process this data at scales and speeds humans cannot match. This could accelerate identification of genuine anomalies.

These technological advances don't guarantee discoveries. But they do expand the search space and improve the signal-to-noise ratio. The probability of detecting an artifact, if artifacts exist, rises with each advancement.

Estimated data shows a gradual increase in the discovery of unexplained transients in archival photographs from the 1890s to the 1950s, suggesting growing interest and capability in astronomical observations.

The Philosophical Implications: What Discovery Would Mean

Beyond the scientific questions, SETA research touches fundamental philosophical territory. What would discovery of alien artifacts tell us about ourselves?

Most obviously, it would confirm that life emerges elsewhere in the universe and that at least one civilization achieved technological sophistication sufficient for interstellar travel. This alone would be revolutionary, settling one of humanity's most ancient questions.

It would also constrain our theories about the frequency of intelligent life and the timeline on which civilizations emerge and achieve spacefaring capability. If an artifact is here now, how old is it? Did the civilization that created it still exist? If not, how long ago did it perish? These questions would help answer the famous Fermi Paradox: if intelligent life is common, why don't we see clear evidence of it everywhere?

Artifact discovery might also reveal something about the nature of alien consciousness and civilization. The design choices made in creating a probe tell us about the values, priorities, and understanding of its creators. A probe designed for communication suggests a civilization interested in peaceful contact. A probe optimized for surveillance might suggest something else entirely.

Philosophically, an artifact would represent a kind of message across the void. Even if it's not actively transmitting signals, its very existence is a statement: "We existed. We were capable. We cared enough about the universe to reach out." That message, for most of humanity, would be profound.

Current Controversies and Legitimate Disagreements

Not all disagreements about SETA research stem from bias or stigma. Some represent genuine scientific disagreements about evidence interpretation and methodology.

For instance, some researchers question whether archival photographic plates can provide reliable evidence of spacecraft. The technology used to create and preserve these plates is understood imperfectly. Systematic errors affecting entire plate series might introduce false signals. The standards for evaluating anomalies differ between researchers.

Another genuine controversy concerns the proper standards of evidence. How strong must evidence be before we claim to have identified an artifact candidate? Some argue for extremely high bars, requiring multiple independent lines of evidence. Others argue that given the stakes of discovery, even moderate evidence warrants serious investigation.

There's also disagreement about the likelihood of various scenarios. How common are interstellar spacecraft? Would aliens target Earth specifically or survey the galaxy randomly? Would artifacts be actively shielded or passively observable? These questions have no clear answers, yet they fundamentally shape what we should be looking for.

These disagreements are healthy. They push the field forward by forcing researchers to sharpen their arguments and evidence. They create the kind of scientific back-and-forth that generates progress.

Building the Search Infrastructure: What Would Be Needed

To conduct truly comprehensive artifact searches would require substantial infrastructure: observational assets, analytical resources, computational power, and most importantly, human expertise.

On the observational side, researchers need access to powerful telescopes with sufficient resolution to distinguish artificial objects from natural phenomena. They need coverage across the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio wavelengths through visible light to infrared and beyond. They need the ability to observe consistently over long periods to identify temporal patterns.

They also need access to archival data. Photographs, spectra, and other observational records accumulated over more than a century provide baseline information about what natural objects should look like. Comparing recent observations to historical ones can reveal changes or anomalies.

Computationally, SETA research demands substantial resources. Processing millions of images, analyzing spectral data, modeling orbital mechanics, and searching for patterns requires powerful computers and sophisticated algorithms.

Most fundamentally, the field needs people. Astronomers trained to ask these questions. Physicists capable of modeling exotic scenarios. Engineers who understand propulsion and spacecraft design. Philosophers and social scientists prepared to think about the implications of discovery. Building and maintaining this expertise requires investment in education and training, which takes time.

The infrastructure for truly comprehensive artifact searches doesn't exist yet, though individual researchers are beginning to assemble components. A fully developed research program would require coordination across multiple institutions, likely with international collaboration.

Timeline: When Might We Expect Results?

Crystal-ball gazing about scientific discovery is notoriously unreliable, but several researchers have offered timelines for when decisive evidence might emerge.

In the near term, over the next five years, we can expect more analysis of existing data. Villarroel's VASCO project will continue examining archival plates. New interstellar objects will be discovered and studied. Methodologies for identifying artifact candidates will be refined.

Within 10-15 years, next-generation observatories should come online fully. The Vera Rubin Observatory and similar facilities will provide unprecedented datasets. AI systems trained on these datasets should improve anomaly detection significantly.

Within 20-30 years, technology might mature sufficiently to support dedicated missions to geosynchronous orbit or other promising search regions. At this timescale, spacecraft designed specifically to search for artifacts could plausibly be developed and launched.

Beyond 30 years, hypothetically, comprehensive searches of multiple candidate regions might have been conducted, and the results—discovery or increasingly confident null findings—would inform science's understanding.

These timelines assume continued funding and interest, which is not guaranteed. They also assume that artifacts, if they exist, are discoverable with foreseeable technology. Some scenarios might require more advanced capabilities.

Practical Next Steps for Researchers

For scientists interested in contributing to SETA research, several concrete paths forward exist.

First, researchers can participate in ongoing projects like VASCO, contributing archival analysis, data interpretation, or methodology development. The project actively recruits collaborators and welcomes contributions from astronomers and data scientists.

Second, researchers can publish theoretical work on artifact detection methodologies, technosignature characteristics, and optimal search strategies. This work might not directly discover artifacts, but it shapes the field's thinking and provides foundation for future observations.

Third, researchers can develop instrumentation and software specifically designed for artifact searches. Better detection algorithms, improved data analysis techniques, and more sensitive instruments all accelerate progress.

Fourth, researchers can mentor students and early-career scientists interested in these topics, ensuring that the field has a succession of trained researchers continuing the work.

Fifth, researchers can engage with funding agencies and policymakers, making the case for why this research matters and how it could be supported sustainably.

None of these paths guarantees discovery. But all of them contribute to building the research enterprise that might eventually produce results.

Implications for Space Policy and Planetary Defense

Artifact searches have surprising connections to space policy and planetary defense, usually thought of as distinct domains.

If researchers develop robust detection systems for spacecraft and probes, those same systems could be adapted to track asteroids, comets, and other objects that pose planetary hazard. Conversely, infrastructure built for asteroid monitoring could be repurposed for artifact searches.

Space policy discussions about debris mitigation and orbital object tracking could benefit from SETA research perspectives. Understanding how to identify, track, and characterize small objects in orbit is relevant whether those objects are human-generated debris or potential alien technology.

There's also a strategic dimension. A nation or alliance that develops superior capability to detect and identify orbital objects gains a significant advantage in space situational awareness. Investment in SETA research could plausibly advance this capability as a byproduct.

These spillover effects suggest that even if society concludes that dedicated artifact searching isn't justified on its own merits, the benefits to space security and planetary defense might provide additional justification for supporting related research.

FAQ

What exactly is an alien artifact?

An alien artifact is a physical object created by an extraterrestrial civilization and present in our solar system. This could range from a small probe the size of a satellite to a massive spacecraft, or from deliberately placed technology to objects that arrived accidentally. The key characteristic is that it would be artificial, created by intelligent beings, rather than a natural occurrence like an asteroid or comet.

How do scientists distinguish between natural objects and potential artifacts?

Scientists establish baseline expectations for what natural objects should look like and how they should behave, then search for anomalies that deviate from these expectations. They examine composition, velocity, trajectory, structural properties, and other characteristics. Anomalies are then evaluated for whether they have natural explanations. Only objects that remain anomalous after thorough analysis become artifact candidates, and even then, the confidence level may remain uncertain.

Why haven't we found definitive proof of alien artifacts yet?

The solar system is incomprehensibly vast, and humans have only been systematically observing it for a few decades. If artifacts exist, they might be in regions we haven't searched thoroughly, or they might be concealed or dormant. Additionally, what looks like an anomaly might ultimately receive a natural explanation as our understanding improves. The absence of confirmed discoveries so far doesn't mean artifacts don't exist; it means either they're not present, or we haven't looked in the right places yet.

What would happen if researchers confirmed the discovery of an alien artifact?

Such a discovery would undergo the most rigorous verification process in scientific history. Multiple independent laboratories would confirm findings. International collaboration would be essential to validate results. The scientific community would shift dramatically, with enormous resources directed toward understanding the artifact. The broader social, political, philosophical, and religious implications would be profound and transformative, reshaping how humanity understands itself in relation to the universe.

Is the search for alien artifacts legitimate science?

Yes. Researchers approach the search using rigorous methodology, establishing clear criteria for what counts as evidence, publishing findings in peer-reviewed journals, and subjecting their work to scientific scrutiny. The fact that the field had historical stigma doesn't invalidate the methodology. Many now-standard research areas were once considered fringe or illegitimate. The legitimacy of a question isn't determined by its popularity but by whether it can be investigated using scientific methods.

How much would a comprehensive search for alien artifacts cost?

Estimates vary, but a dedicated mission to thoroughly survey geosynchronous orbit would likely cost $1-3 billion, comparable to major space telescope missions or planetary science programs that already receive funding. A comprehensive survey of multiple promising regions might cost substantially more. These expenses are significant but not prohibitive relative to government space budgets. The primary barriers are political and cultural rather than financial.

Could alien artifacts already be on Earth?

This is theoretically possible but considered extremely unlikely by most scientists. If aliens visited Earth, they would likely attempt to minimize disruption or detection. Any artifacts left behind would probably be hidden or concealed. So far, no objects or structures have been definitively identified as artificial extraterrestrial technology. Claims that ancient structures or artifacts are alien in origin lack credible evidence and are generally considered pseudoscience by mainstream researchers.

What would an alien probe look like?

There's no way to know definitively. A probe might look like a conventional spacecraft, similar to human-designed probes. Alternatively, it might look completely unlike anything humans have built, incorporating materials or design principles unfamiliar to us. It might be designed to look like a natural object to avoid detection. Or it might be deliberately conspicuous, intended as a beacon. The lack of clear expectations about appearance is one of the challenges in searching.

How do scientists search through archival sky surveys?

Archival surveys contain millions of photographic plates and digital images from telescopes accumulated over more than a century. Researchers digitize these images and analyze them computationally, searching for objects that appear in some images but not others, or that move in ways inconsistent with natural objects. They also look for objects with properties that seem artificial rather than natural. This labor-intensive process has become more feasible with advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Could an alien probe reach Earth from another star system?

Yes, in principle. The nearest star system, Proxima Centauri, is about 4.24 light-years away. A probe traveling at 10% the speed of light would take 42 years to reach Earth. Faster travel is physically possible but would require enormous energy. Slower travel would take centuries or millennia. The timescales are large, but not impossibly so for an advanced civilization with centuries or millennia of planning horizon. This is why researchers take the possibility seriously.

Conclusion: A Field Coming of Age

The search for alien artifacts has transitioned from speculative philosophy into operational astronomy. That statement might surprise people who still think of artifact hunting as the domain of UFO enthusiasts and conspiracy theorists. But the science has matured. Methodologies have been developed. Researchers are publishing in mainstream journals. Data is being collected and analyzed with rigor.

This doesn't mean that artifacts will be discovered. They might not exist. They might be so rare that the solar system happens to contain none. They might be deliberately hidden, designed to avoid detection by newly emerging technological civilizations. Or they might be present, waiting to be found, but in regions we haven't searched yet.

What matters is that humanity is finally asking the right questions and developing the tools to answer them. The search won't resolve overnight. It might take decades or longer. But the infrastructure is being built. The methodology is being tested. The conversation is becoming respectable.

In a broader sense, this research reflects something important about scientific progress. Legitimate science doesn't require that all researchers agree on which questions matter. It requires that researchers use rigorous methodology, publish findings openly, subject their work to peer review, and remain willing to be proven wrong. SETA research meets these criteria.

The implications of discovery would be vast. But even if discoveries never come, the research has value. It sharpens our understanding of how to search for rare events in enormous datasets. It forces us to clarify what we mean by artificial versus natural. It pushes technology development forward in pursuit of better observational capabilities.

Most profoundly, it reflects humanity's deep need to understand our place in the cosmos. Are we alone? Have others come before us? Will we eventually encounter evidence of extraterrestrial civilization?

We still don't have definitive answers to these questions. But we're finally asking them in ways that science can address. The search for alien artifacts is coming into focus, and what we find—or don't find—will shape human understanding for generations to come.

The work continues. The sky remains to be searched. And somewhere in the vast darkness, the answers might be waiting.

Key Takeaways

- SETA research has evolved from theoretical speculation to rigorous observational astronomy with peer-reviewed publications and systematic methodologies

- Discovery of three confirmed interstellar objects (1I/Oumuamua, 2I/Borisov, 3I/ATLAS) provides ground truth that such visitors actually exist in our solar system

- Beatriz Villarroel's analysis of pre-Sputnik archival sky surveys identified unexplained transient objects that cannot be definitively explained as natural phenomena

- Geosynchronous orbit at 22,000 miles above Earth represents a strategic focus area for artifact searches due to orbital stability and observational accessibility

- Stigma surrounding artifact searches remains a significant barrier despite rigorous methodology, limiting funding and institutional support for comprehensive surveys

- Detection of potential alien technology would require extraordinary evidence and international verification, transforming human understanding of our place in the universe

![The Search for Alien Artifacts Is Coming Into Focus [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-search-for-alien-artifacts-is-coming-into-focus-2025/image-1-1768822765331.jpg)