Introduction: The Global Space Launch Industry at an Inflection Point

We're living through one of the most pivotal moments in spaceflight history, and honestly, most people don't realize it. The space launch industry isn't just evolving—it's fundamentally restructuring itself. The old European monopoly is collapsing, SpaceX keeps redefining what's possible, and now countries like India are reverse-engineering the playbook with homegrown rockets that can compete globally.

Here's what's happening right now, in early 2025: Europe's betting big on Ariane 6 as its answer to SpaceX dominance. India is allegedly developing a reusable rocket that looks suspiciously like a Falcon 9. The US military is investing a billion dollars directly into rocket motor suppliers to shore up munitions production. And meanwhile, smaller launch companies are scrambling to find their niche in a market that's consolidating faster than anyone predicted.

The stakes are enormous. Whoever controls the economics of space access controls everything downstream: satellite constellations, space tourism, deep space exploration, national defense. That's not hyperbole. It's literally why governments are pouring billions into launch capability right now.

This article breaks down everything happening in the commercial space launch world in 2025. We're talking about real hardware launches, actual financial commitments, international competition that's intensifying by the month, and the business model shifts that are making some rocket companies thrive while others struggle. You'll see specific numbers, launch dates, payload capacities, and the technical details that matter.

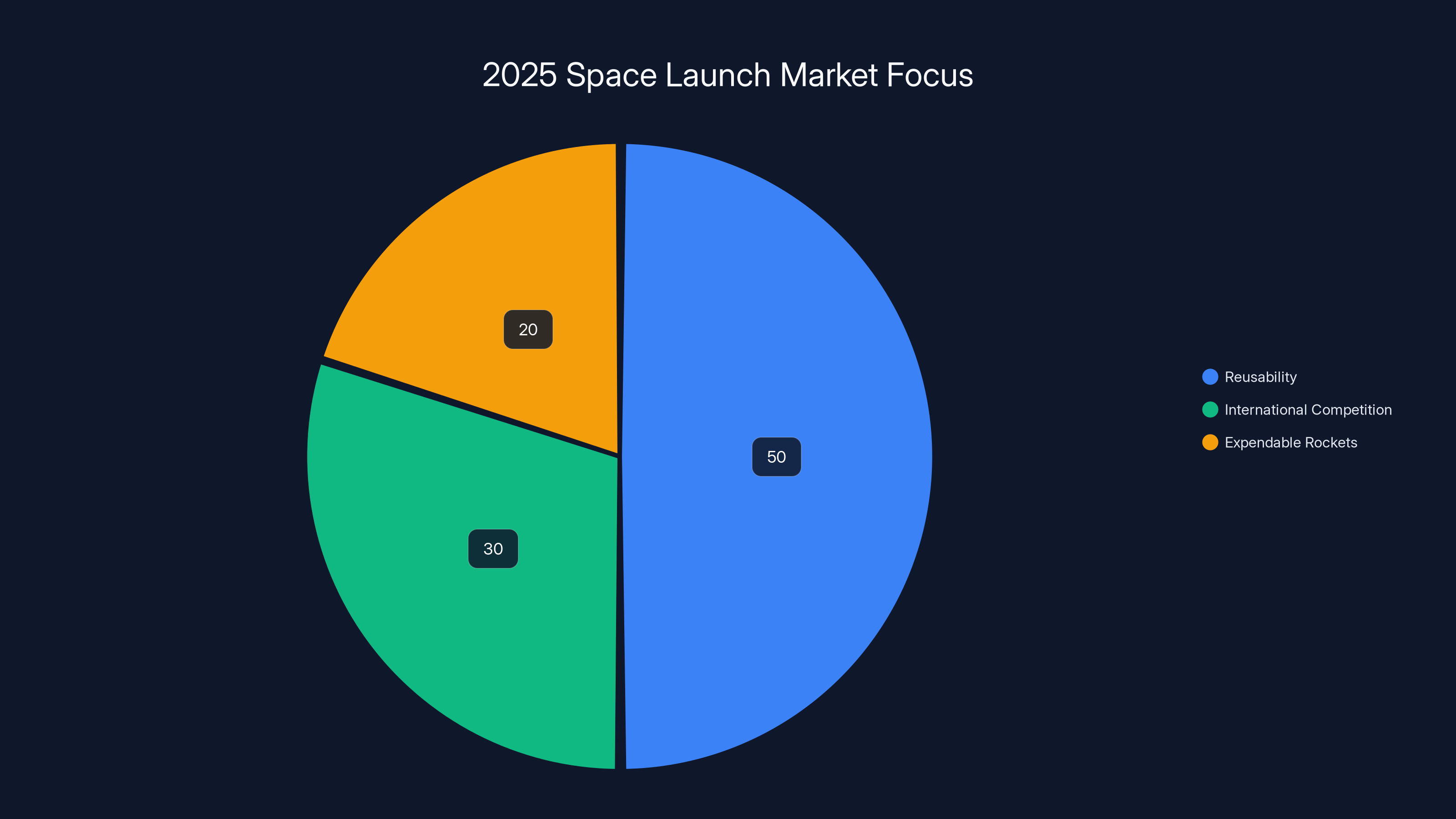

The landscape is shifting because the fundamental economics of spaceflight have changed. Reusability works now. It's proven. That means the companies and nations that can master rapid reusability will own the market. Everyone else is playing catch-up, whether they admit it or not.

TL; DR

- Ariane 6 launches Amazon satellites in February: Europe's new heavy-lift rocket variant (Ariane 64) carries 18 missions worth of One Web broadband satellites starting this month

- India developing homegrown Falcon 9 competitor: Multiple failures of the PSLV have accelerated India's timeline for a reusable rocket platform

- US military consolidates launch supply chain: $1 billion government investment in L3 Harris rocket motors signals shift in how defense secures critical spaceflight infrastructure

- Small launch vehicles struggling: Companies like Firefly and others are forced to redesign core systems after repeated failures

- Reusability is now the baseline: Every new rocket in development emphasizes first-stage recovery and rapid turnaround

- Bottom Line: The 2025 space launch market is consolidating around reusability, international competition is intensifying, and the days of expendable rockets are numbered

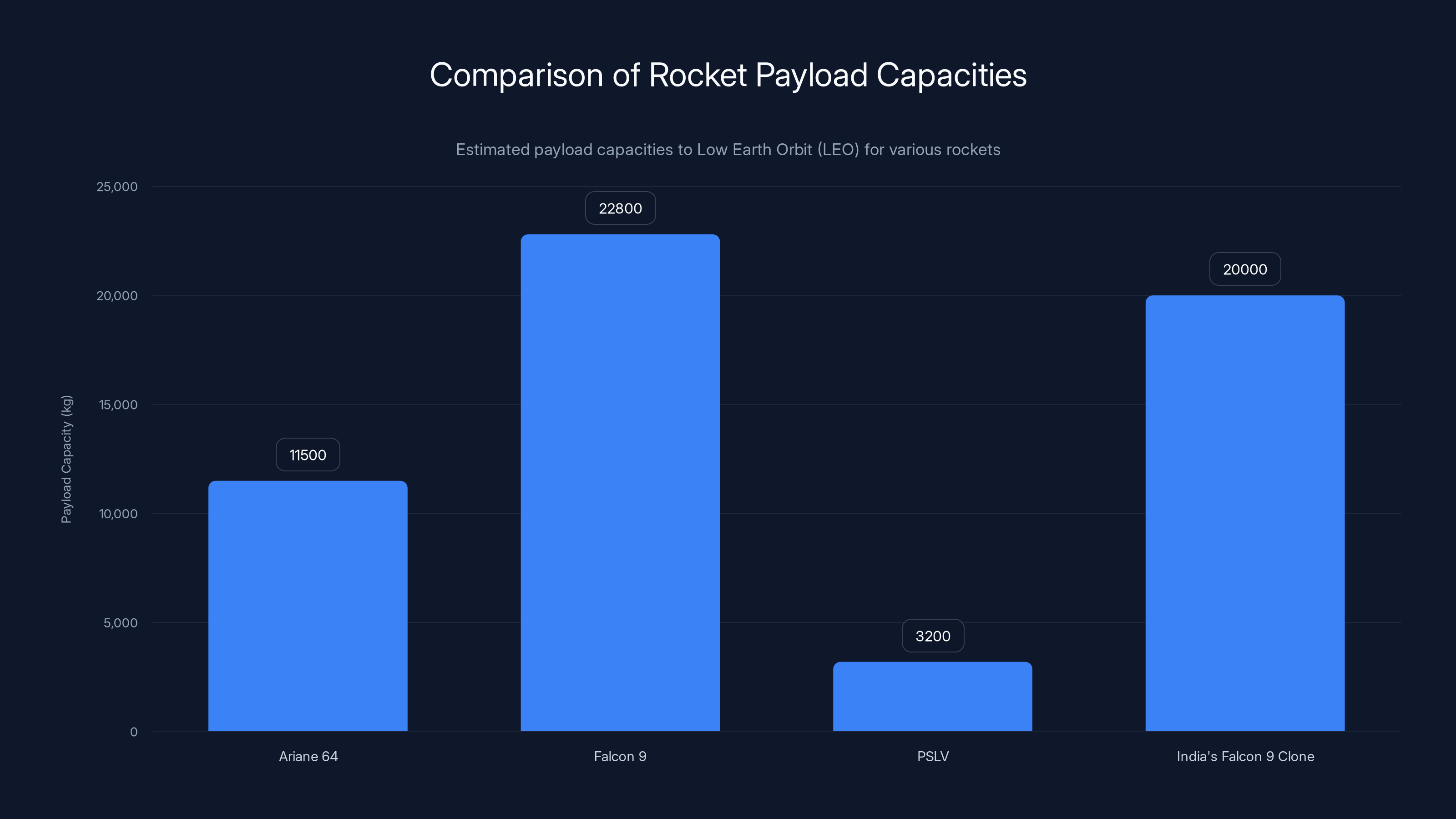

Ariane 64 can deliver approximately 11,500 kg to LEO, competing with SpaceX's Falcon 9. India's development of a Falcon 9 clone aims for a 20,000 kg capacity, enhancing its space access capabilities. Estimated data.

The Ariane 6 Debut: Europe's Serious Push to Stay Relevant

Ariane 64 Variant: Why Four Boosters Matter

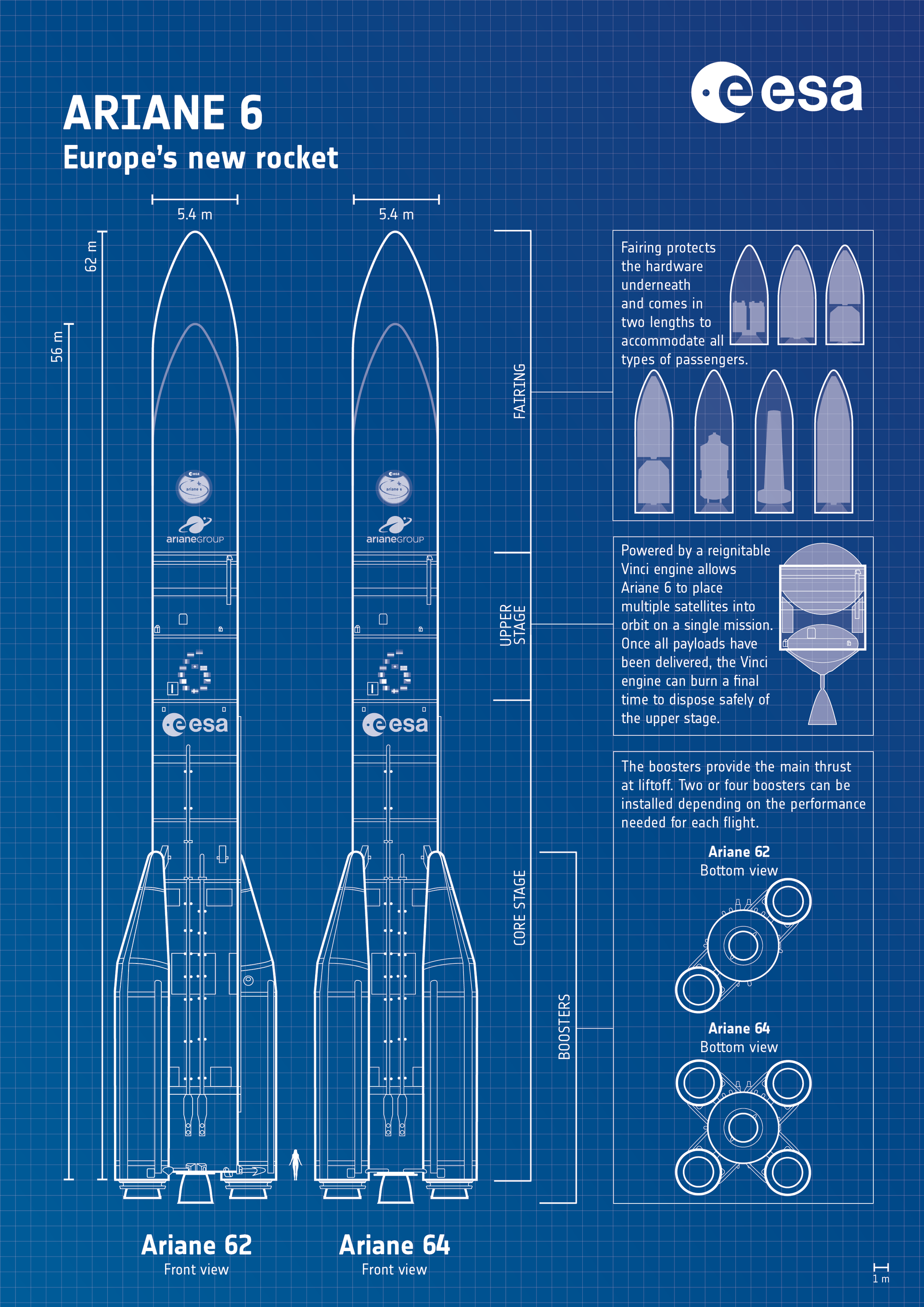

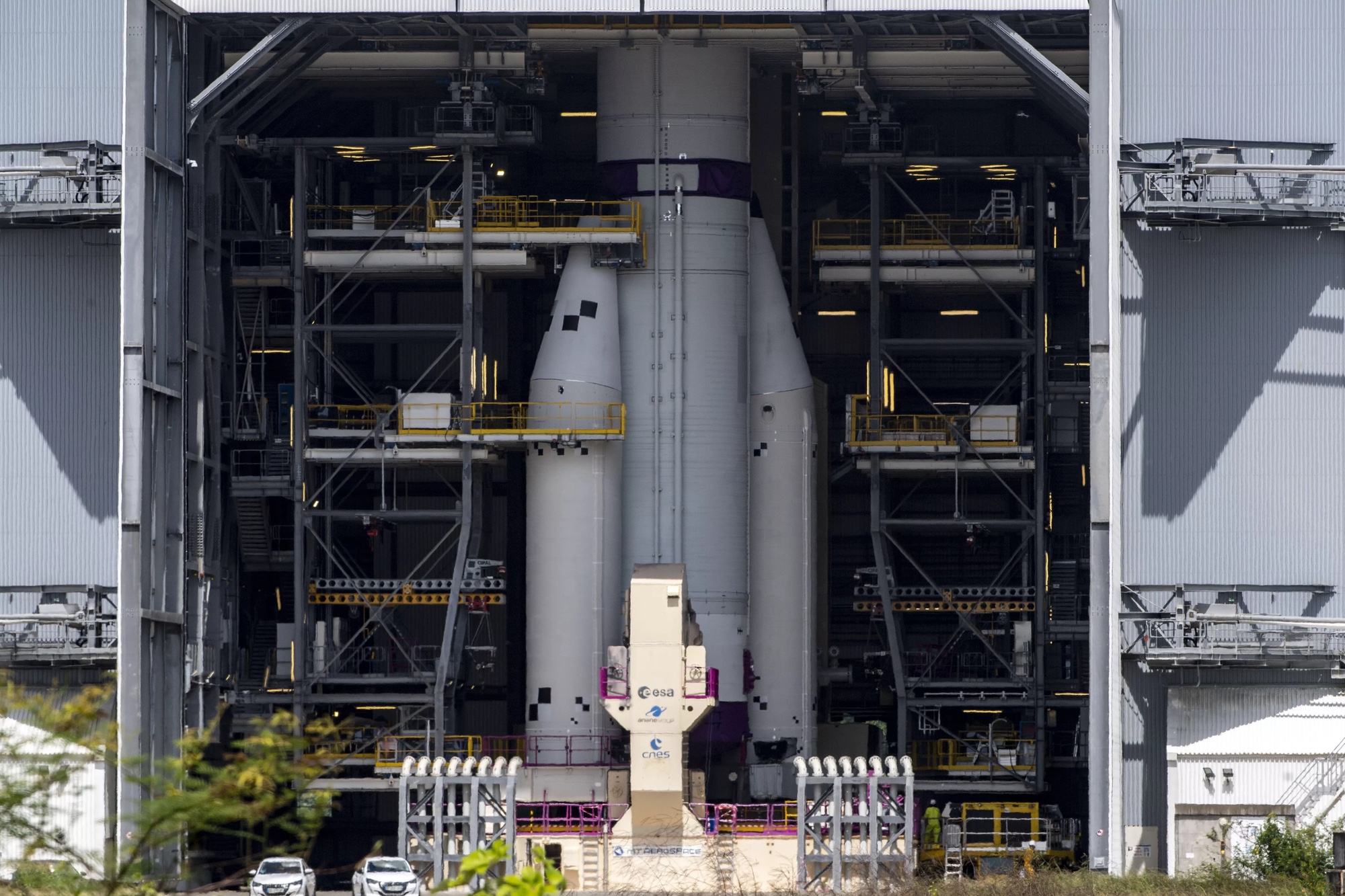

Let's talk about the Ariane 6. If you've been paying attention to space news, you know Europe's been working on this rocket for years. The first test flight happened back in July 2024, and it worked. But here's the thing: the real story isn't just that Ariane 6 exists. It's the variants and how they're being deployed.

Arianespace announced it's launching Ariane 64 on February 12 from French Guiana. The "64" designation means four solid rocket boosters attached to the main core. The "6" refers to the 60-meter height. It's a straightforward naming scheme, but the implications are significant. More boosters mean heavier payload capacity. More payload capacity means the economics get better for satellite constellation providers.

For the Ariane 6 specifically, the 64 variant can deliver somewhere in the neighborhood of 11,500 kilograms to low Earth orbit. That's substantial. When you're launching satellites for mega-constellations like One Web or Kuiper, mass to orbit directly translates to cost per satellite. Better economics mean more profitable missions.

The first Ariane 64 mission is carrying Amazon's Project Kuiper satellites. This isn't a one-off contract. Arianespace secured 18 dedicated launches from Amazon. Eighteen. That's a massive commitment representing hundreds of millions in revenue. For a company that's been publicly struggling against SpaceX's efficiency, this is validation that customers still see value in the Ariane 6.

The One Web Infrastructure Play

Wait, let's back up for a second. One Web. You've probably heard that name before, especially if you follow satellite internet. One Web is a broadband constellation that's been through absolute hell. The company went bankrupt once, got rescued by the British government and India's Bharti Airtel, and has been clawing its way back ever since.

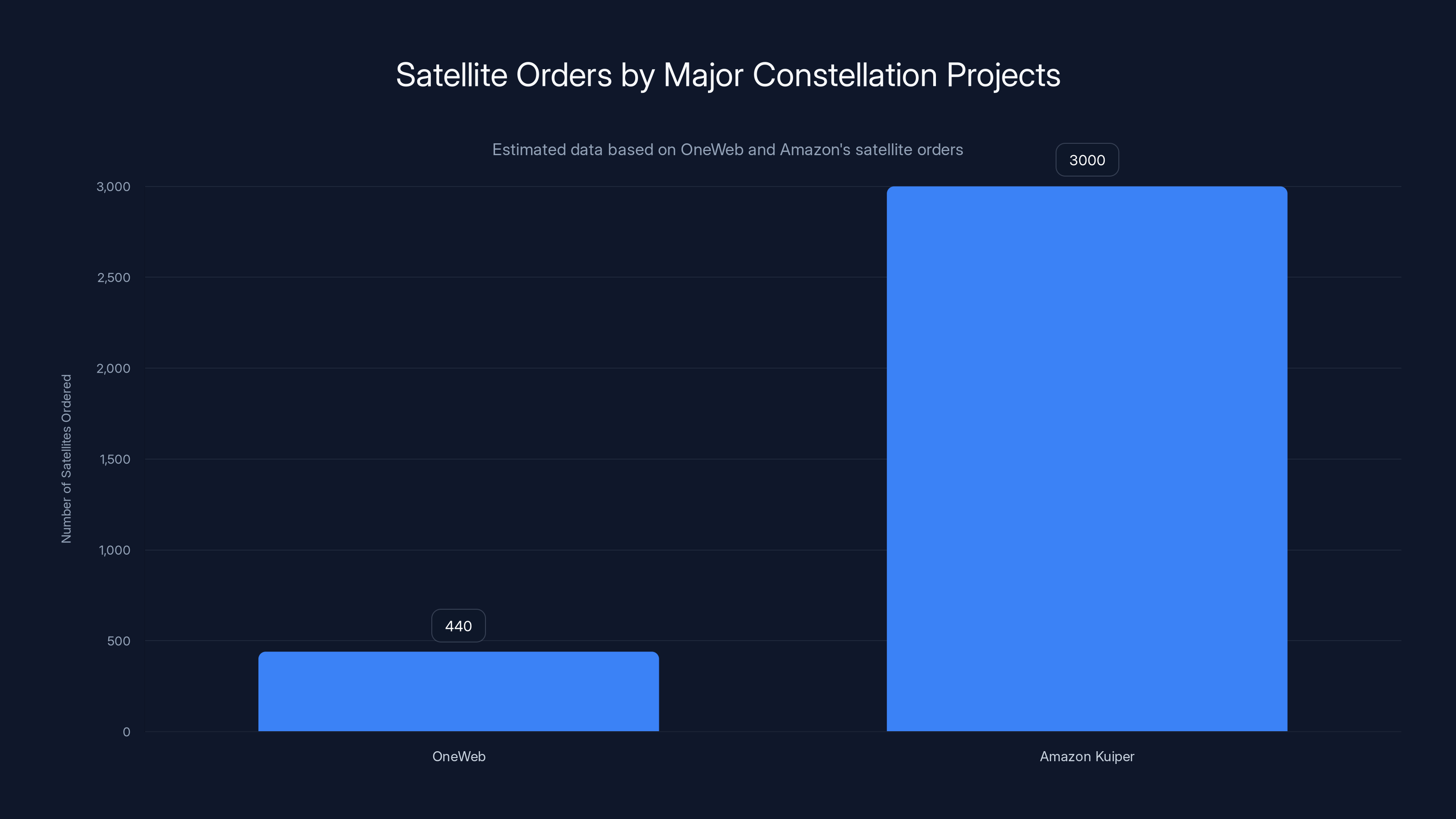

Amazon is fundamentally restructuring One Web's satellite procurement. The company ordered 440 new satellites from Airbus to either renew existing One Web capacity or expand it. Think about that number: 440 satellites. At roughly 10-15 satellites per Ariane launch, that's 30-plus launches. And Arianespace got to bid on a significant portion of them.

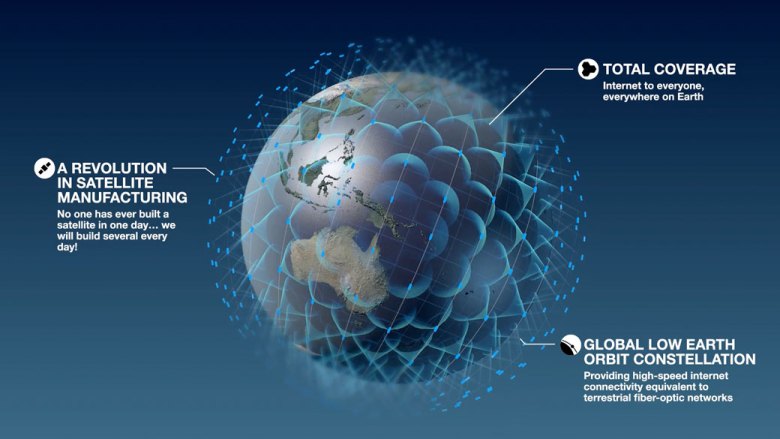

The reason this matters is that mega-constellation development is one of the few things that can drive launch cadence. You need volume launch contracts to justify the infrastructure investments and the workforce expansion. SpaceX figured this out with Starlink. They built the rocket company partly to serve the constellation company. Now European launch providers are finally getting enough commercial satellite work to make the economics work.

Ariane 6 Performance vs. Falcon 9

Here's where I need to be honest about the competitive dynamics. Falcon 9 is still more efficient. SpaceX has demonstrated first-stage recovery on nearly every mission. Their booster reuse turnaround times keep getting shorter. The cost-per-kilogram advantage is still in SpaceX's corner.

But Ariane 6 has some genuine advantages. It launches from French Guiana, which is closer to the equator than most US launch sites. That translates to a free velocity boost from Earth's rotation for certain orbits. It's a subtle advantage, but it compounds. The rocket also uses liquid methane for upper stage propulsion in some versions, which provides better performance than the RP-1 kerosene that Falcon 9 uses.

The real question isn't whether Ariane 6 is better. It's whether the European industrial base can achieve the operational cadence that customers demand. Arianespace ran four Ariane 6 launches last year. They're targeting continued increases. But SpaceX is flying 30-plus missions annually now. That gap matters.

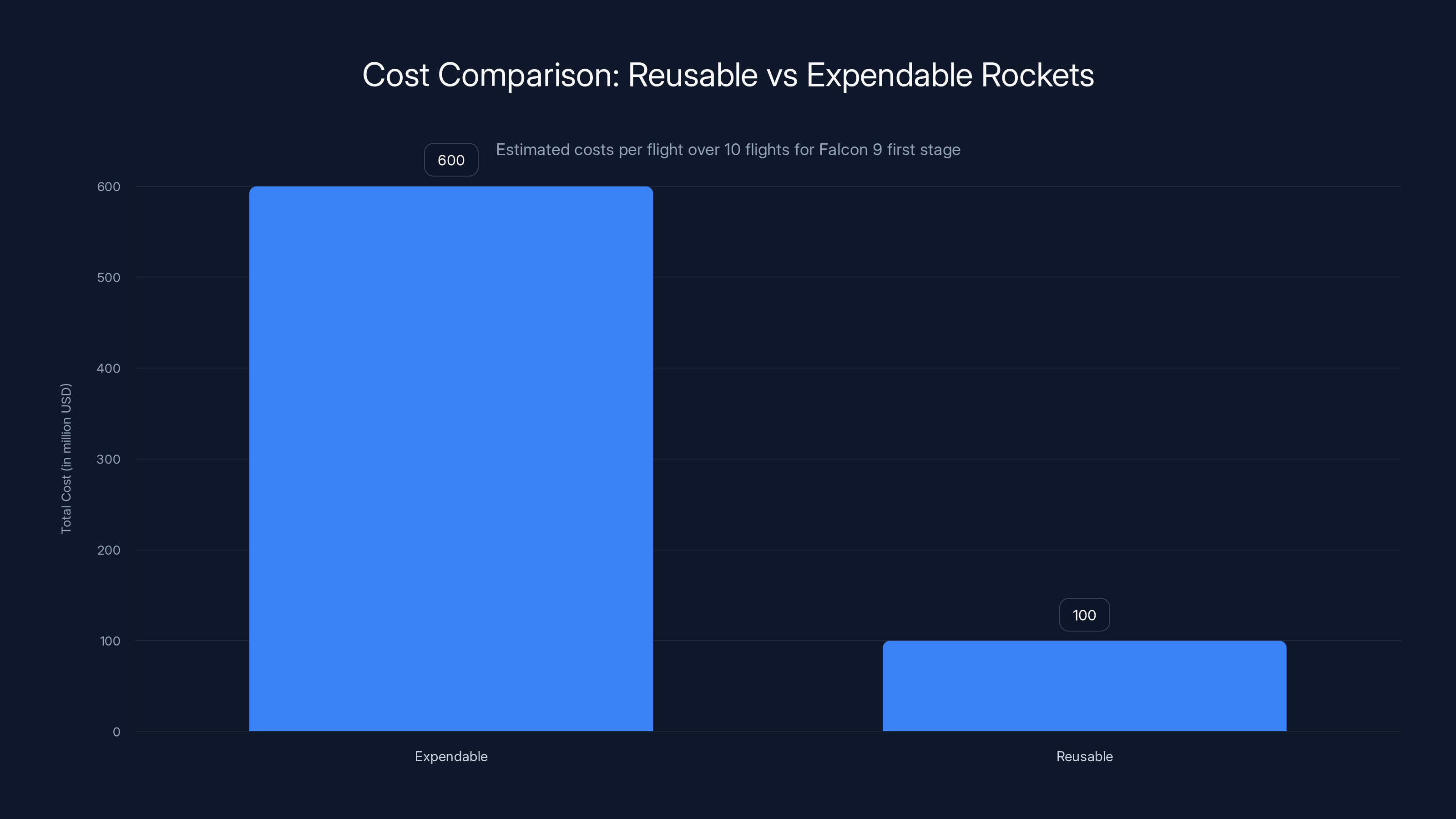

Reusability significantly reduces costs, with reusable rockets costing approximately

Maia Space: The Scrappy Ariane Group Subsidiary Making Waves

From Side Project to Major Contracts

Maia Space is doing something interesting. It's a subsidiary of Ariane Group, created in 2022, but it's positioned as a separate entity. Think of it as the "startup within the incumbent" strategy. The goal is to be faster and more agile than the parent company while retaining access to infrastructure and capital.

This week, Maia Space signed a major launch contract with Eutelsat. We're talking about a significant chunk of the 440-satellite One Web order. That's not chump change. That's real commercial validation.

Why would a major satellite operator choose Maia Space over established launch providers? Two reasons: price and availability. Maia Space is hungry. They need to establish a manifest and prove their rocket works. They're therefore incentivized to offer competitive pricing. And they're building something new, so they can implement better operational practices from day one instead of inheriting legacy inefficiencies.

Maia Specifications and Performance

Let's talk about what Maia actually is. It's a liquid oxygen and methane-fueled rocket. LOX-methane is becoming increasingly popular because it's a sweet spot between performance and manufacturability. It's cleaner than kerosene-based fuels. It's more efficient than solid rocket motors for medium-lift applications. And industrial machinery can handle LOX-methane infrastructure without the extreme complexity that hydrogen requires.

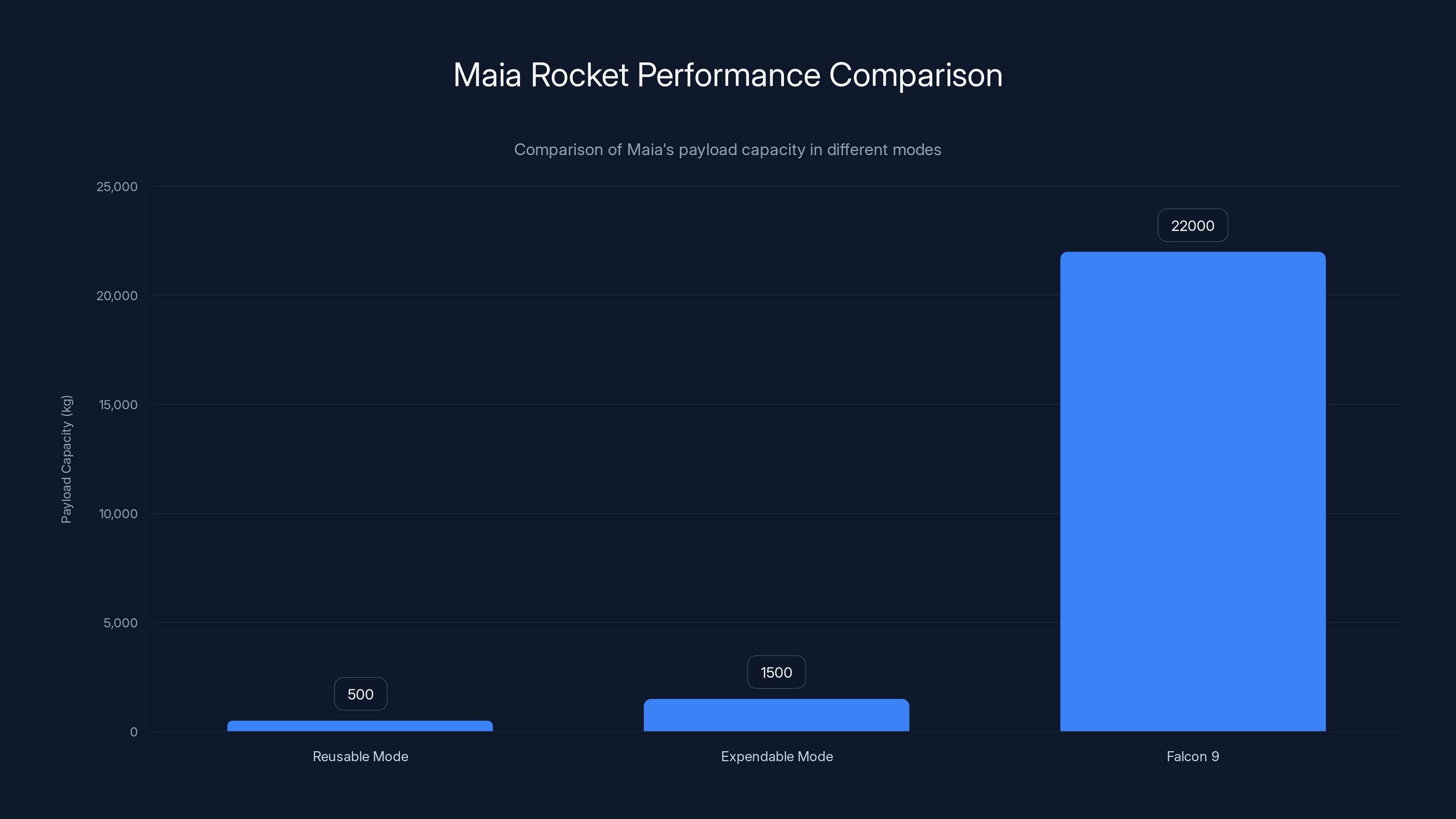

Maia is designed to lift 500 kilograms to low Earth orbit when the first stage is recovered and reused. That's the reusable mode. When flown expendably, it can deliver 1,500 kilograms. Those numbers seem modest compared to Falcon 9's 22-plus ton capacity to LEO. But Maia isn't competing with Falcon 9. It's competing for a different market segment: dedicated launches for smaller operators who don't have enough payload to fill a Falcon 9.

The first test flight of Maia is scheduled for the end of 2026, a year later than originally planned. That's actually pretty normal for new rockets. Delays happen. But the operational plan is aggressive: once Maia starts flying, Eutelsat satellites should start launching in 2027. That's a 12-18 month gap between first test flight and commercial operations. That's ambitious but not impossible.

The Subsidiary Model vs. Traditional Aerospace

What's fascinating about Maia Space is the organizational structure. It's shielded from traditional Ariane Group bureaucracy. It can move faster. But it still has access to the parent company's facilities, test infrastructure, and expertise. That's a genuine advantage over pure startup rocket companies that have to build everything from scratch.

This model is catching on. Blue Origin has New Shepard and New Glenn operating somewhat independently. SpaceX operates as a single entity but breaks out Starship development as a separate focus. The idea is that you need organizational agility to make rockets work in the modern era.

The risk, of course, is that a subsidiary can cannibalize the parent's business. If Maia becomes super successful and captures customers from Ariane 6, that's a problem for Ariane Group executives. But that's also how innovation works. You kill your own business before competitors do.

India's PSLV Failures and the Falcon 9 Clone Strategy

The PSLV Track Record: Two Consecutive Failures

India's space program just had a rough month. The PSLV-C62 mission failed in early 2026. That's the second consecutive PSLV failure, both involving the same problem: the third stage. The mission carried 16 satellites from multiple countries. They're all lost now.

Let me provide some context. The PSLV, or Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle, has been India's workhorse rocket since 1993. It's a four-stage vehicle using a mix of solid and liquid propulsion. First stage: solid fuel. Second stage: liquid fuel. Third stage: solid fuel. Fourth stage: liquid fuel. It's a proven design that achieved 58 consecutive successful missions before these recent failures.

58 successful missions in a row. That's an extraordinary track record. But here's what matters: that streak is over. When a reliable rocket suddenly has problems, it signals that something fundamental has changed. Maybe they've pushed the envelope on throttling. Maybe the manufacturing process had a subtle deviation. Maybe they're using a different supplier for a critical component. But whatever it is, two failures in a row on the same stage means the investigation is going to be lengthy and thorough.

ISRO, India's space agency, initiated a formal detailed analysis. They're not rushing to figure this out. Given the sensitivity around satellite launch failures and the international payload losses, the investigation will be meticulous.

The Hidden Story: Development of a Reusable Rocket

But here's where it gets interesting. Behind the PSLV failures, India has been quietly developing something that looks a lot like a Falcon 9. Reusable first stage. Powered by indigenous LOX-methane engines. Designed for rapid turnaround. The unofficial references call it India's "Falcon 9 clone," though Indian space officials are careful not to use that language publicly.

The PSLV failures are actually accelerating the timeline for this new rocket. When your legacy system starts failing and customers demand reliability, you have two options: fix the legacy system or replace it with something better. India is pursuing both, but the reusable rocket program is clearly getting elevated priority.

Why does India need this? Volume. India's space program wants to establish space infrastructure over the next decade. That means satellite constellations for communications, Earth observation, navigation, and defense. You can't build constellations if your launch vehicle fails every 30 missions. You need something more reliable and more frequent.

The Import of the LOX-Methane Technology

LOX-methane is the sweet spot for modern rocket development. It's what SpaceX uses for Raptor engines. It's what Blue Origin uses for BE-4. It's what Rocket Lab is moving toward with their new Neutron vehicle. India's adoption of the same fuel combination means the technology has truly become the industry standard.

The advantage is immense. LOX-methane is storeable in normal conditions. It doesn't require extreme cryogenic maintenance like hydrogen. Engines can be tested repeatedly without degradation. Manufacturing is straightforward with conventional equipment. Compare that to solid rocket boosters, which are effectively one-use and harder to inspect thoroughly, or hydrogen systems, which require specialized facilities for everything.

India's ISRO has already flown LOX-methane engines on test flights. They know the technology works. The challenge is integrating it into a complete reusable first-stage design and proving that it can achieve the rapid turnaround that makes reusability economically viable.

If India successfully deploys a reusable rocket even approaching Falcon 9's capability, it fundamentally changes the geopolitical dynamics of space access. Right now, SpaceX is the only company consistently achieving true rapid reusability. India joining that club would represent a genuine disruption.

Maia's payload capacity is modest compared to Falcon 9, but it targets a different market segment with its 500 kg and 1,500 kg capacities in reusable and expendable modes respectively.

The US Military's Rocket Motor Consolidation

Why $1 Billion in Direct Investment?

Let's talk about something that doesn't get enough attention: rocket motors used in weapons systems. Tomahawk missiles. Patriot interceptors. Standard missile variants. These aren't exotic space rockets. They're proven military hardware that's been in service for decades. But they all need rocket motors, and those motors have been supplied by the same industrial base for a very long time.

The US Department of Defense just invested $1 billion directly into L3 Harris Technologies' rocket motor business. It's a convertible security that will automatically become equity when L3 Harris spins out the rocket motor division as a separate public company later in 2026.

Why? Because the Pentagon is worried about supply chain fragility. Michael Duffey, the undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment, put it bluntly: "We are fundamentally shifting our approach to securing our munitions supply chain." That's not casual language. That's a statement about strategic vulnerability.

Here's the problem: the industrial base for producing rocket motors for missiles has consolidated significantly over the past 20 years. When consolidation happens, you get fewer suppliers, which means less redundancy. If a supplier gets disrupted for any reason, the entire supply chain can be at risk. And in a crisis scenario, if the US is burning through munitions rapidly, you need surge capacity. You need multiple suppliers. You need resilience.

The Industrial Base Problem

Rocket motor production requires specialized manufacturing. You can't just retool a factory that makes airplane parts. You need facilities that understand solid propellant processing, casting, quality control, and the specific requirements of defense applications. Those facilities are expensive to build and operate.

Over time, smaller suppliers have either shut down or consolidated upward into larger contractors. That consolidation made business sense during peacetime when volumes were low and steady. But in the context of a potential peer conflict or a major regional war, it's a vulnerability.

L3 Harris has been expanding its rocket motor capabilities significantly. By taking a direct equity stake, the Pentagon is essentially saying: we want this company to have financial incentive to expand capacity. We want them to have resources to modernize facilities. We want them to take risks on expanding production without worrying about demand uncertainty.

The Conflict of Interest Problem

Now here's the awkward part: the US government will own equity in a company that bids on major defense contracts. That's a conflict of interest. Full stop. L3 Harris competes for lucrative Pentagon contracts every year. Now the Pentagon itself is an investor in L3 Harris. That creates obvious potential for bias, favoritism, or accusations thereof.

The government's response is basically that this is necessary for national security. The Pentagon argues that ensuring a resilient munitions supply chain overrides normal procurement concerns. That may be true, but it sets a precedent. If it's okay for defense to directly invest in L3 Harris, why not other suppliers? And if the government starts taking equity stakes in multiple suppliers, you've effectively partially nationalized the defense industrial base.

There will be legal challenges. Competitors will argue conflict of interest. Congressional oversight committees will hold hearings. But in the near term, the investment likely proceeds, and L3 Harris expands capacity.

Firefly Aerospace's Reliability Crisis and Block II Redesign

The Failure Record That Nobody Wants

Firefly Aerospace has a problem. It's a company that's been working on the Alpha rocket for years, invested hundreds of millions, and has six launches to show for it. Of those six, only two were complete successes. That's a 33% success rate. In the commercial rocket business, you need close to 100% or you'll lose customers, insurance support, and ultimately funding.

So Firefly announced a "Block II" upgrade to Alpha. The CEO, Jason Kim, says they're focusing on "enhancing reliability, streamlining producibility, and improving launch operations." That sounds like corporate-speak, but it's actually meaningful. Producibility means they're trying to manufacture rockets faster and with less manual labor. Reliability means they're addressing the fundamental design or manufacturing issues that caused the failures.

Alpha Flight 7, scheduled to launch "in the coming weeks," will be the last flight in the current configuration. It will carry multiple Block II subsystems in what they call "shadow mode." That means the new components are flying but not actively controlling the rocket. They're monitoring how they perform alongside the existing systems. Once they're confident the Block II parts work, they'll transition to active control.

What Went Wrong and Why It Matters

Firefly hasn't been fully transparent about what caused each failure. That's normal—there's competitive sensitivity around failures. But the pattern suggests fundamental design issues rather than one-off anomalies. When your first six flights fail that frequently, it's usually because something about the overall design or integration wasn't correct.

Possibilities include: thrust vectoring problems that damaged the airframe, combustion instability in the engines, structural failure under flight loads, guidance system issues, or integration problems between stages. Without official data, it's speculation. But the fact that they need a complete Block II redesign rather than minor tweaks suggests something structural.

What matters is that Firefly isn't giving up. The company has customer commitments and investor backing. They're taking the pragmatic approach: redesign, retest, and resume operations. It's the right call. The alternative—trying to incrementally fix the existing design—would take longer and inspire less confidence.

The Broader Lessons for New Launch Companies

Firefly's experience illustrates why launching rockets is genuinely hard. It's not just engineering. It's operational discipline, quality control, and having enough resources to iterate when problems emerge. Firefly has all three. Many startups don't.

There's a graveyard of launch startups that burned through funding, had failures they couldn't debug, and ran out of money before reaching reliable operations. Orbital ATK, Orbital Sciences, Kistler Aerospace—these were real companies with real funding that still failed to reach operational status.

Firefly's Block II redesign represents institutional knowledge. They've tested hundreds of hardware subsystems. They've analyzed the failures. They know where the weak points are. Now they're systematically addressing them. That's how you actually build a rocket company.

The fact that Firefly is willing to reveal their redesign plan publicly is also significant. It signals confidence. They're not in crisis management mode. They're in optimization mode. That's a healthy signal for customers and investors.

OneWeb has ordered 440 satellites, while Amazon's Project Kuiper plans to deploy around 3000, indicating significant investment in satellite-based broadband (Estimated data).

NASA's Artemis II: The SLS Rollout and Timeline Reality

What the Wet Dress Rehearsal Actually Tests

NASA's Space Launch System has been in development for over a decade. The Artemis II mission represents the first crewed flight of the SLS and Orion spacecraft. This weekend, NASA is rolling out the complete stack to the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The mission starts with a wet dress rehearsal. That means NASA will fuel the entire rocket, run through all the countdown procedures, get to terminal countdown, and then... stop. They won't ignite the engines. They'll drain the propellant and learn what went wrong.

The WDR is crucial because it's the only way to validate integrated systems at scale. You can test individual components in laboratories. You can test stage-by-stage. But when you put all 385 feet of the rocket together and start loading it with 2.1 million pounds of propellant, things behave differently. Different structural loads. Different acoustic environments. Different thermal dynamics.

If something's going to fail catastrophically, it's often going to reveal itself during fueling operations. That's a feature, not a bug. NASA would much rather find problems with an unpiloted rocket during ground testing than discover them during crewed flight.

The February 8 No-Earlier-Than Date

NASA set a no-earlier-than launch date of February 8 for Artemis II. That's contingent on the wet dress rehearsal going well. If the WDR surfaces significant issues, the launch date slips. That's the standard progression.

Here's the thing: everybody expected Artemis II to launch in 2024. Then it became 2025. Now we're looking at February 2025 at the earliest, which means it will actually launch in spring or summer 2025, probably. These dates have been slipping for years because SLS is complex and development has been genuinely challenging.

The cost to date for developing the SLS is somewhere north of $40 billion, depending on how you allocate expenses. The goal is to eventually launch it annually. But annual SLS operations remain theoretical. Every mission requires extensive ground infrastructure preparation, multiple testing campaigns, and careful management of the supply chain.

Compare that to SpaceX's Starship, which has completed multiple test flights in a single year, or Falcon 9, which now launches over 30 times annually. The operational cadence difference is stunning. But SLS and Starship serve different purposes. SLS is specifically designed for deep space missions to the Moon. Falcon 9 is optimized for Earth orbit and expendable payloads.

The Significance of Artemis II for NASA's Moon Architecture

Artemis II matters because it validates the entire SLS-Orion-Artemis architecture. If something goes wrong with the crewed flight, it jeopardizes the entire program. If it succeeds, it opens the path for Artemis III, which will actually land astronauts on the Moon. That's the goal. That's what all this investment is for.

Artemis III is tentatively scheduled for 2026, but that's almost certainly optimistic. These timelines always slip. But the fundamental path is clear: prove the SLS works, then use it to support Artemis missions to the Moon, then establish a sustained presence.

The Moon architecture depends on multiple companies and systems working together: Blue Origin's Human Landing System, various cargo delivery providers, life support systems from multiple vendors, and the SLS itself. It's extraordinarily complex. Every component has to work flawlessly.

The Economics of Rocket Reusability at Scale

The Cost Structure Problem

Let's talk about why reusability matters so much in modern rocketry. The simple answer is economics. A Falcon 9 first stage costs roughly

But if you recover and reuse that stage 10 times, the cost per flight drops to

Compare that to a completely expendable rocket where the first stage is one-use: every flight is

For Ariane 6, European officials have emphasized reusability. For Maia, reusability is a design goal. For India's new reusable rocket, reusability isn't optional. Every new serious rocket program now includes first-stage recovery as a baseline assumption.

The Operational Challenges

But here's where it gets complicated. Reusability sounds simple in theory. In practice, it requires:

- Precision landing zones and recovery infrastructure

- Rapid inspection and refurbishment procedures

- Precision-manufactured engines that tolerate multiple flight cycles

- Advanced materials that don't degrade significantly over reuse

- Software systems that can autonomously land a falling rocket

- Rigorous quality control to ensure each stage is safe to fly again

SpaceX has solved most of this, but it took years of iteration. They've achieved booster reuse cadences where some stages fly multiple times within a single month. That's extraordinary from a logistics and manufacturing perspective.

Other companies are still working on the basics. Can they recover the stage? Can they inspect it thoroughly? Can they refurbish it quickly? These are solved problems at SpaceX. They're still challenging at other companies.

The Supply Chain Implications

Reusability also changes supply chain dynamics. With expendable rockets, you manufacture engines at a certain rate because each one is used once. With reusable rockets, you need fewer engines total, but you need better engines that tolerate multiple cycles.

That means engine suppliers need to invest in higher-quality manufacturing processes. It means tighter tolerances. It means more thorough testing. It means higher cost per engine, but lower total engine demand.

For traditional aerospace suppliers that have been building expendable rocket motors for decades, reusability is a disruption. They need to transition to manufacturing for durability rather than single-use optimization. Some will make the transition successfully. Others won't.

Estimated data shows that by 2025, the space launch market will heavily focus on reusability (50%), with significant international competition (30%), and a declining emphasis on expendable rockets (20%).

The Satellite Constellation Wave Driving Launch Demand

One Web's Resurrection and Expansion

One Web was essentially dead a few years ago. The company went bankrupt, assets were sold, and it looked like the mega-constellation dream was over. Then Bharti Airtel and the British government came in, rescued the company, and essentially said: we're going to make this work.

Now One Web has ordered 440 new satellites from Airbus. That's a massive undertaking. It represents years of continuous launch operations, billions in manufacturing costs, and a bet that global broadband demand from satellites is real and addressable.

Why would Bharti Airtel, an Indian telecom operator, invest in One Web? Because connectivity is valuable. One Web's satellites provide latency characteristics acceptable for video conferencing and web browsing. Previous satellite internet was too laggy for real-time applications. One Web is different.

The 440-satellite order also signals confidence that the launch market will support the cadence needed to get these satellites deployed within a reasonable timeframe. That confidence depends on multiple launch providers offering competitive pricing and reliable service.

Kuiper and Amazon's Mega-Constellation Push

Amazon's Project Kuiper is in similar territory. Amazon ordered thousands of satellites from Kuiper-focused manufacturers. The company secured 18 dedicated Ariane 6 launches just in the first phase.

Kuiper is not live yet. No satellites have launched. But Amazon's financial commitment is real. The company has invested tens of billions into the program. They're treating it as a core piece of future AWS infrastructure.

Kuiper is interesting because it's forcing Amazon to make launch provider decisions. Amazon can't just use Blue Origin, even though Blue Origin is partially owned by Amazon's founder. Instead, Amazon is diversifying across Ariane 6, Falcon 9, and potentially others. That's actually good for competition. It prevents any single launch provider from becoming too essential.

The Intersection of Constellations and Ground Infrastructure

Mega-constellations are only valuable if the ground infrastructure exists to use them. You need user terminals. You need gateway stations. You need regulatory approval in every country. You need spectrum. These are complex problems that go beyond rocketry.

But from a launch perspective, mega-constellations are the demand driver that makes sustained high-cadence operations possible. Without them, the market for launch services would be fragmented: some government missions, some commercial satellites, some interplanetary missions. With mega-constellations, you have steady, predictable launch demand that can justify dedicated launch infrastructure and workforce.

This is exactly what SpaceX needed with Starlink. Having a captive customer (Starlink) meant SpaceX could justify rapid Falcon 9 operations even if other customers were sparse. Now that SpaceX has other customers, Starlink is still there as a baseline demand driver.

Launch Failures and the Investigation Process

What Actually Happens After a Mission Failure

When a rocket fails, there's an immediate investigation. That investigation is intensive and can take months. For the PSLV-C62 failure, ISRO will likely conduct:

- Telemetry analysis—examining every sensor reading from launch to failure

- Component examination—studying the third stage remains for signs of what broke

- Manufacturing review—checking if the third stage was built according to spec

- Test data review—looking at all ground testing done on that specific stage

- Supply chain investigation—confirming material specifications and supplier quality

Only after all this can ISRO determine root cause and implement corrective actions. Then they have to ground all PSLV launches until the fix is verified through testing.

For a company like ISRO that relies on government funding, a sustained grounding of your primary launch vehicle is a significant problem. It impacts commercial customers, government satellite missions, and India's standing in the launch services market.

Why Third-Stage Failures Are Particularly Frustrating

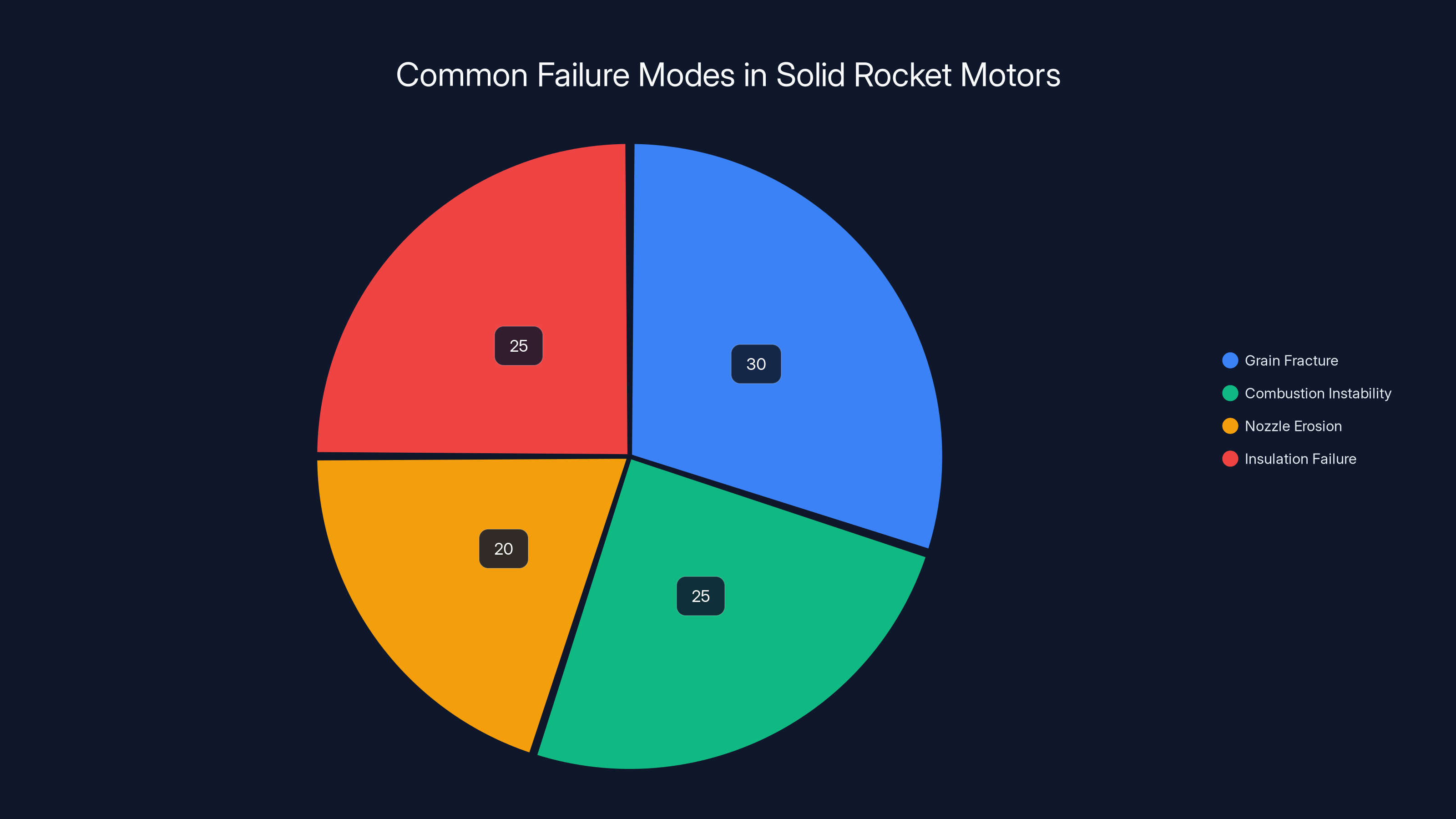

The PSLV third stage is solid-fueled. Solid rocket motors, once you light them, are burning until they're empty. You can't shut them down. You can't restart them if they flake out. That's different from liquid-fueled stages where you have more control.

Third-stage anomalies are especially challenging because the stage is already in space when they happen. The rocket has escaped Earth's atmosphere, deployed its first and second stages, and the third stage is supposed to establish velocity and orbit. If something goes wrong at that point, the payload is unrecoverable.

For solid motors, failure modes can include: grain fracture (the solid propellant develops cracks that change burn characteristics), combustion instability (the burn becomes erratic), nozzle erosion (the nozzle throat enlarges and changes thrust), or insulation failure (the casing is breached and the structure fails). Any of these are catastrophic.

Solid motors are more difficult to inspect than liquid engines because you can't visually examine the interior without destroying the motor. You have ultrasonic scanning and X-rays, but those have limitations. Once you stack a solid motor onto a rocket and close it up, you're trusting the manufacturing process implicitly.

The Path Forward for PSLV

ISRO will fix the PSLV. They have institutional expertise and a track record. But the failure rate change—from 58 consecutive successes to two failures—signals that something changed. Maybe they're flying the rocket at higher temperatures or pressures. Maybe there's a supply chain issue. Maybe the design is reaching operational limits.

The acceleration of India's reusable rocket program is directly connected to PSLV failures. If PSLV keeps working reliably, there's less urgency. But now there's urgency. That's actually healthy for India's long-term space program because reusable vehicles are the future anyway.

Grain fracture and insulation failure are estimated to be the most common failure modes in solid rocket motors, each accounting for about 25-30% of failures. Estimated data.

The Defense Space Industrial Base and National Security Implications

Why Rocket Motors Matter for Military Capability

Rocket motors are used in everything from sea-launch cruise missiles to air-defense systems. Tomahawk cruise missiles have been in service since the 1980s. Patriot air-defense systems go back even further. These weapons are core to US military capability.

The rocket motors in these weapons were designed decades ago. Manufacturing processes have evolved, but the basic technology is stable and proven. The problem isn't the technology. It's the supply chain and production capacity.

During peacetime, military demands for rocket motors are steady but not huge. You build enough to maintain readiness, train personnel, and maintain a surge capacity buffer. But if the US got into a large-scale conflict, rocket motor demand would spike immediately. The supply chain would be stressed.

The Surge Capacity Problem

Surge capacity is the ability to ramp production from normal peacetime levels to wartime levels. In the modern era, surge capacity is harder to achieve because manufacturing is optimized for efficiency, not flexibility. You can't easily double production overnight.

During the Cold War, the US maintained surge manufacturing capacity in various defense sectors. That was expensive but deliberate. In the post-Cold War era, that capacity was reduced as a cost-cutting measure. That was probably a mistake.

The Pentagon's investment in L3 Harris directly addresses this. By taking an equity stake and guaranteeing investment, the Pentagon is essentially saying: expand your facilities, hire more people, prepare for surge production. That costs money, but it ensures that if conflict happens, the supply chain can support high-volume operations.

The Geopolitical Dimension

Rocket motors for defense applications are sensitive technology. You don't just buy them from whoever. There are strict controls on export. Every production facility is secured and inspected. The workforce is vetted.

The US wants to ensure that its supply chains for critical defense systems are domestically secure. That means not relying on foreign suppliers and not having critical facilities in countries where the US doesn't have direct control.

L3 Harris is a US company with US-based facilities. The Pentagon's investment supports US employment, US manufacturing, and US supply chain security. That's the strategic objective.

The 2025 Launch Manifest: What's Coming

Near-Term Launches and Scheduled Missions

The space launch calendar for 2025 is packed. Ariane 64 is scheduled for February 12. That will be followed by additional Ariane 6 launches as Amazon Kuiper satellite deliveries continue. Falcon 9 is flying 30+ times this year. SLS Artemis II is targeting spring or summer. Blue Origin's New Glenn is in the late stages of preparation.

Indian PSLV launches are on hold pending investigation closure, but once cleared, operations will resume. Chinese Long March variants continue regular commercial and government operations. Japan's H3 is ramping to multiple launches per year. The manifest is full.

This represents genuine global competition. Every major spacefaring nation except Russia is launching actively. The manifest diversity signals healthy competition and customer choice.

The Technology Transitions Happening This Year

Several first-flight test programs are scheduled for 2025. These include Maia's debut, Firefly's Block II operations, potentially Blue Origin's New Glenn, and various smaller vehicles. Each of these represents a technology transition that, if successful, will shift the competitive dynamics.

New Glenn is particularly significant because it represents Blue Origin's heavy-lift entry. Blue Origin has been development-heavy and launch-light for years. If New Glenn succeeds, it's validation that the company's approach works. If it fails, it's a setback for the company and a confidence issue for customers.

Supply Chain and Operational Readiness

Launch operations at scale require prepared ground infrastructure. That means launch pads that are ready, range safety systems that are certified, and support equipment that's maintained. The US has limited range capacity. The ability of Florida's Space Coast to support 30+ launches annually is a logistics achievement.

Every international launch site has similar constraints. French Guiana can't support unlimited launch cadence. The same is true for Japan, India, and China. There are actual physical and regulatory limits on how many rockets you can launch from any given location.

This creates an interesting dynamic. Companies like SpaceX are investing in additional launch facilities precisely because single-pad limitations constrain growth. Launch Pad 39A can only support so many Falcon 9 launches per year. Boca Chica can only support so many Starship tests. Multi-site operations become necessary at high cadence.

Future Predictions: What Comes After 2025

The Reusability Maturation Curve

Over the next 3-5 years, reusability will transition from competitive advantage to table stakes. Every new rocket will expect rapid booster reuse as normal. Companies that can't achieve it will struggle to compete.

We're already seeing this transition with Ariane 6 announcing reusability goals and Maia designing for booster recovery from day one. The only hold-outs will be specialized vehicles with unique mission requirements.

This has profound implications for manufacturing. The engines in next-generation rockets need to be more robust. Structures need to tolerate more stress cycles. Materials need to perform better. This drives R&D investment and creates technology differentiation.

The Consolidation Likelihood

The launch services market will probably consolidate further. We've already seen this: small launch vehicles are struggling, medium-lift is being squeezed by Falcon 9's efficiency, and heavy-lift remains specialized.

Over the next decade, expect fewer launch providers globally but with higher flight rates from the survivors. The economics of rocketry mean that you either achieve scale or you don't survive. Middle-market launch companies face real pressure.

Exceptions exist for specialized niches: air-launch for small payloads, vertical launch for dedicated missions from specific locations, and reusable suborbital for microgravity research. But orbital launch services are consolidating toward a handful of dominant providers.

International Competition and Commercial-Military Blending

The line between commercial and military launch services is blurring. The Pentagon's investment in L3 Harris is one example. National space agencies leveraging commercial providers is another. This is healthy for innovation but creates complicated policy questions.

International competition will intensify. India's reusable rocket, if successful, will be a genuine competitor. Japan's H3 and European Ariane 6 will continue improving. China's Long March family is sophisticated and proven. This is good for global space access but creates geopolitical tensions around space infrastructure.

The space launch market will likely remain regional for a while: US providers dominate in the Western hemisphere, European providers operate from French Guiana and Europe, China and India have their own ecosystems. That's actually healthy because it prevents any single entity from controlling global access to space.

The Role of Government Contracts and Supporting Demand

Government demand remains crucial for launch providers. Commercial satellites are great, but government missions provide stable, predictable revenue. National security space launch contracts are worth hundreds of millions. NASA contracts drive innovation.

As mega-constellations mature and commercial space activity increases, government may represent a smaller percentage of total market activity. But absolute government spending will probably remain stable or grow. That's important for launch providers' long-term planning.

We're essentially in a phase where government and commercial are learning to work together in space launch. That's new. Historically, governments did their own thing. Now governments are customers of commercial providers and partners in development. That partnership model is proving effective.

The Technical Innovation Cycle Accelerating

Methane-Based Propulsion as the Standard

LOX-methane is winning. Almost every new rocket program includes methane engines in the design. The advantages are obvious: better performance than kerosene, simpler handling than hydrogen, and proven manufacturability.

This represents a technical consensus forming around the optimal fuel for modern rocketry. That's healthy because consensus enables standardization, supply chain maturation, and operational expertise development.

We're likely to see methane engines proliferate across the industry. Component suppliers will specialize in methane hardware. Engineers will accumulate expertise. That's how technologies mature.

The Full Flow Stage Combustion Debate

SpaceX's Raptor engines use full flow stage combustion, a sophisticated cycle that achieves exceptional efficiency. Other engine programs are studying whether to adopt similar cycles.

Full flow is complex. It requires better materials, more sophisticated control systems, and precision manufacturing. But the performance gains are meaningful. Over a long program's lifetime, fuel efficiency compounds into significant cost savings.

We're at an inflection point where the technology is feasible for multiple companies, not just SpaceX. That will drive a wave of new engine development across the industry.

Materials and Manufacturing Innovation

Rocket structure require advanced materials: aluminum-lithium alloys, titanium composites, specialized steels. As rockets become reusable, the demands on materials intensify. You need materials that tolerate multiple thermal cycles and landing impacts.

Manufacturing innovation is equally important. Automated welding, robotic assembly, and additive manufacturing are all being applied to rocket structures. The cost per kilogram of structure is coming down, which improves the fundamental economics of rocketry.

This innovation happens across the industry. It's not proprietary. Once something works, other companies adopt it. That's healthy for the industry.

Conclusion: The Space Launch Market in 2025 and Beyond

We're in the middle of a fundamental restructuring of space launch. The old model where spaceflight was rare, expensive, and government-dominated is dead. The new model is commercial-led, reusability-focused, and increasingly competitive.

Ariane 6 is proving that Europe can still compete if it modernizes. India's development of a Falcon 9 competitor signals that reusability capability is spreading globally. The US military's consolidation of the rocket motor supply chain shows governments are taking space infrastructure seriously. Firefly's willingness to redesign and iterate demonstrates that startup resilience is real.

The mega-constellation wave is driving sustained launch demand. One Web, Kuiper, Starlink—these constellations will require thousands of launches over the next decade. That demand is justifying investment in launch infrastructure and pushing technology forward.

Reusability is no longer aspirational. It's proven. The question now is which companies and nations can master it best. The competitive advantages go to whoever can recover rockets quickly, refurbish them reliably, and refly them with minimal turnaround time. SpaceX has this figured out. Others are catching up.

The supply chain is shifting. Traditional defense contractors like L3 Harris are being integrated into government planning in new ways. Launch providers are becoming critical infrastructure. The industrial base is adapting to the reality that space access will be routine, frequent, and essential.

What's next? Watch Ariane 64's February 12 launch. That mission will show whether European launch operations can achieve the cadence and reliability needed to compete. Watch Firefly's Block II progression. That will indicate whether smaller launch companies can actually execute redesigns and return to flight. Watch India's PSLV investigation closure and the timeline for their reusable rocket debut. That will show whether alternative launch capabilities are genuinely spreading globally.

The space launch race isn't about a finish line. It's about who builds the most reliable, most economical, most frequent space access for the next 20 years. That's not determined in a single launch. It's determined by consistent execution over time.

2025 will be a landmark year for space launch. We'll see first flights of new vehicles, major missions from established providers, and the groundwork for everything coming next. Pay attention. The decisions made this year shape the space industry for the next decade.

FAQ

What is the Ariane 64 and why does it matter?

Ariane 64 is the four-booster variant of the Ariane 6 heavy-lift rocket. The "6" refers to the 60-meter height, and the "4" indicates four solid rocket boosters attached to the core. This variant can deliver approximately 11,500 kilograms to low Earth orbit, making it capable of launching mega-constellation satellites like Amazon's Project Kuiper. The significance is that Ariane 64 represents Europe's serious commitment to competing with SpaceX by securing long-term commercial contracts, particularly Amazon's 18-launch commitment for Kuiper satellite deployment.

How does reusable first-stage recovery work in modern rockets?

Reusable first-stage recovery involves the rocket's lower stage separating from upper stages after reaching a certain altitude and velocity. The first stage then performs a controlled descent using precision sensors, guidance systems, and deployed fins or grid fins to stabilize descent. The stage uses reserved propellant to ignite engines for final deceleration, either landing on a drone ship at sea or a land pad. After landing, engineers inspect the stage for damage, refurbish critical components, and prepare it for another flight. SpaceX has refined this process to achieve booster reuse cadences where some first stages fly multiple times within weeks, dramatically reducing the cost per launch.

Why is India developing a Falcon 9 clone and what does this mean for space access?

India's development of a reusable rocket with Falcon 9-like capabilities is driven by the critical failures of the PSLV-C62 mission and the broader need for frequent, reliable launch capability to support India's satellite constellation ambitions. A homegrown reusable rocket would give India independent space access and reduce dependence on foreign launch providers. This development signals that reusable launch technology is becoming the global standard and that nations with space ambitions cannot rely on expendable rockets anymore. If India successfully deploys a reusable vehicle, it would fundamentally change space launch competition and give India significant geopolitical leverage in the space domain.

What is the Pentagon trying to accomplish with its $1 billion investment in L3 Harris rocket motors?

The US Department of Defense is investing $1 billion in L3 Harris Technologies' rocket motor business to address critical vulnerabilities in the munitions supply chain. Rocket motors are essential components in cruise missiles like Tomahawks and air-defense systems like Patriot. By taking an equity stake in L3 Harris, the Pentagon ensures that the company has financial incentive to expand production capacity, modernize facilities, and prepare for potential wartime surge production. The investment addresses the reality that the defense industrial base has consolidated significantly over two decades, reducing redundancy and surge capacity. This shifts the strategy from buying on open market to directly investing in suppliers deemed essential for national security.

What went wrong with the PSLV-C62 mission and India's launch reliability?

PSLV-C62 failed due to an anomaly in the third stage, marking the second consecutive PSLV failure with the same component. The PSLV is a four-stage vehicle mixing solid and liquid-fueled stages, with the third stage using solid propulsion. When solid rocket motors fail, the anomaly can be catastrophic because solid propulsion cannot be shut down once ignited. This mission lost 16 satellites from multiple countries. The string of failures after 58 consecutive successes suggests something fundamental changed: possibly new manufacturing tolerances, supply chain issues, or the rocket reaching operational limits. ISRO is conducting a detailed investigation that will ground PSLV launches until the root cause is identified and corrected.

How is mega-constellation demand driving the launch services market?

Mega-constellations like One Web, Kuiper, and Starlink require thousands of satellite launches spread over several years. One Web's order of 440 satellites from Airbus, combined with Amazon's 18-launch Arianespace contract for Kuiper, represents sustained demand that justifies continued investment in launch infrastructure. This constellation demand is fundamentally different from traditional space missions where launch opportunities are sporadic. With constellations, launch providers have predictable volume and long-term customer relationships, enabling them to invest in ground infrastructure, workforce expansion, and technology development. The constellation wave is making space access routine rather than exceptional, which aligns perfectly with reusable rocket economics where high flight frequency is essential for cost-effectiveness.

What makes Firefly's Block II redesign significant?

Firefly's Alpha rocket achieved only 2 successful launches out of 6 attempts, a 33% success rate that threatens customer confidence. The Block II redesign addresses fundamental issues in reliability, manufacturability, and operational efficiency by consolidating parts, implementing stronger structures with automated manufacturing, and incorporating lessons learned from hardware testing and failures. The significance is that Firefly is choosing to fundamentally redesign rather than incrementally fix, suggesting systemic issues rather than isolated problems. If Block II succeeds, it validates Firefly's engineering approach and design corrections. If it fails, the company faces an extended timeline. Either way, the willingness to redesign and iterate is the correct approach for new launch companies developing orbital-class vehicles.

Why did Maia Space secure major launch contracts despite being a new company?

Maia Space, a subsidiary of Ariane Group created in 2022, secured significant launch contracts from Eutelsat for One Web satellites because of competitive advantages that new entrants can possess. First, Maia Space is motivated to offer competitive pricing to establish a manifest and build reputation. Second, as a separate entity from traditional Ariane Group, it can operate more agilely and implement better operational practices from inception without inheriting legacy inefficiencies. Third, the subsidiary model provides access to Ariane Group's infrastructure and expertise while maintaining autonomy. The Eutelsat contract validates that customers appreciate Maia Space's approach and believe the company can deliver reliable, cost-effective launch service once Maia completes its first test flight scheduled for late 2026.

How does the transition from expendable to reusable rockets change manufacturing and supply chains?

The shift from expendable to reusable fundamentally changes component specifications, manufacturing processes, and supplier relationships. Expendable rockets can tolerate manufacturing variations that reusable rockets cannot because reusable components must survive multiple flight cycles, thermal stress, landing impacts, and refurbishment. This requires higher-quality manufacturing, tighter tolerances, and materials with better fatigue resistance. Engine suppliers must transition from optimizing for single-use to optimizing for durability. Structural manufacturers need materials and processes that maintain properties through multiple flights. Supply chain volumes shift as well: fewer total engines and structures are needed, but each one must be better quality. Traditional suppliers accustomed to high-volume, single-use production must adapt to lower-volume, higher-quality reusable manufacturing.

What are the realistic timelines for next-generation rockets to reach operational status?

Based on historical patterns and current programs, timeline expectations should be conservative. Ariane 6 had its first launch in July 2024 and is targeting consistent operational cadence through 2025 and beyond. Maia's first test flight is planned for late 2026, with operational missions potentially starting in 2027 or 2028. Firefly's Block II redesign will extend their timeline beyond original plans, likely pushing operational recovery to 2025-2026 at the earliest. Blue Origin's New Glenn is targeting first flight in late 2024 or early 2025. India's reusable rocket is in development with timelines that are uncertain given current investigation delays. Every rocket program to date has experienced delays relative to original announcements. Plan for three-to-six-month delays to be normal. Significant anomalies extend timelines further.

Try automating your research and content workflows with Runable. For teams following space industry developments, Runable's AI-powered platform can generate automated reports, timelines, and research summaries from technical documentation, saving hours every week. Try Runable for free starting at just $9/month.

Key Takeaways

- Ariane 6's Ariane 64 variant launches February 12, carrying Amazon Kuiper satellites as part of an 18-mission contract worth hundreds of millions

- India is developing a reusable rocket with Falcon 9-like capabilities after consecutive PSLV failures, signaling that reusability is becoming the global standard

- Pentagon invested $1 billion in L3Harris rocket motors to shore up defense supply chain resilience and ensure surge manufacturing capacity for munitions systems

- Firefly Aerospace's 33% success rate (2 of 6 launches) prompted comprehensive Block II redesign, illustrating challenges new launch companies face achieving reliability

- Mega-constellation demand from OneWeb (440 satellites), Amazon Kuiper, and Starlink is driving sustained launch volume that justifies continued infrastructure investment

Related Articles

- RTX 5070 Ti Memory Shortage: What's Really Happening in the GPU Market [2025]

- NexGen, AMD's $850M Gamble: How a Startup Challenged Intel [2025]

- Best Buy Winter Sale 2025: 19 Deals Worth Buying Now

- The Fake War on Protein: Politics, Masculinity & Nutrition [2025]

- People-First Communities in the Age of AI [2025]

- AI Data Center Infrastructure Upgrades: The Engineering Boom [2025]

![The Space Launch Race Heats Up: Ariane 6, India's Falcon 9 Clone, and the Future [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-space-launch-race-heats-up-ariane-6-india-s-falcon-9-clo/image-1-1768567055148.jpg)