Introduction: When Creators Critique Their Own Work

There's something uniquely revealing when a developer takes a public playthrough of their own game and starts roasting the work they poured months into creating. That's exactly what happened when CD Projekt Red's lead story designer Artur Ganszyniec sat down for a YouTube playthrough of the original Witcher game and reached the epilogue. What unfolded wasn't a nostalgic love letter to a classic RPG, but rather a brutally honest critique of design choices he himself had implemented.

Ganszyniec's candid commentary about the epilogue—specifically calling one mechanic "extremely stupid design" and telling himself "Artur, you should be ashamed"—has since become a fascinating case study in game development failure, creative compromise, and the realities of production crunch. It's not often you get this kind of transparency from industry veterans about what went wrong and why. Most developers polish their public image and defend their choices, but Ganszyniec's raw honesty reveals something deeper about the gap between creative vision and finished product.

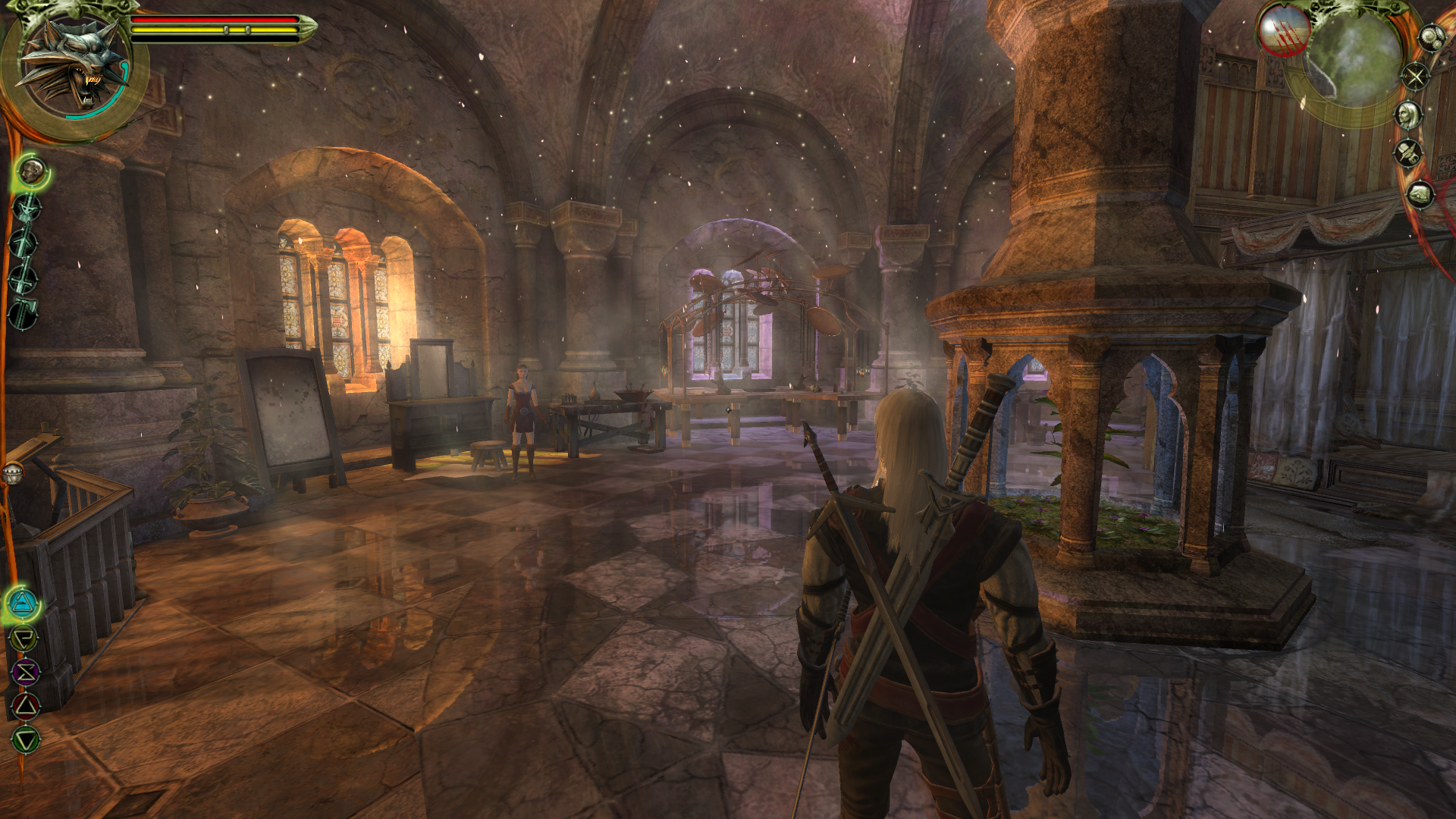

The original Witcher, released in 2007, occupies a strange space in gaming history. It wasn't The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, the critically acclaimed masterpiece that launched the franchise into mainstream consciousness. It was rough around the edges, technically ambitious for its time, and deeply flawed in ways that even its own creators now acknowledge openly. Yet it was also groundbreaking—a narrative-driven RPG that prioritized storytelling and moral complexity before that became industry standard.

What makes Ganszyniec's criticism particularly interesting is the context: the epilogue wasn't a passion project developed with ample time and resources. It was hastily assembled during the final crunch period of development, largely by Ganszyniec himself and project lead Jacek Brzeziński working nights toward the end of production. That timeframe created rough edges that have stuck around for nearly two decades. Now, with a full remake of the original game in development by Fool's Theory using Unreal Engine 5, these old design decisions are being re-examined and potentially corrected.

This article digs into what Ganszyniec revealed during his playthrough, why last-minute development timelines create these kinds of problems, and what his criticism tells us about game design philosophy, creative compromise, and the ongoing efforts to preserve and improve classic games.

TL; DR

- Direct Critique: Artur Ganszyniec, The Witcher's lead story designer, publicly called his own epilogue design "extremely stupid" during a YouTube playthrough

- Crunch Production: The epilogue was largely created by Ganszyniec and Jacek Brzeziński during late-stage crunch, resulting in rough mechanics

- Specific Issue: A campfire lighting bug prevented proper meditation mechanics, exemplifying poorly implemented design

- Remake Opportunity: CD Projekt Red's full remake using Unreal Engine 5 offers a chance to address these design flaws

- Bottom Line: Developer transparency about creative failures reveals the tension between creative ambition and production realities in game development

Despite receiving mixed review scores (around 70), The Witcher sold over 1.5 million copies, highlighting the impact of strong narrative and player choice on sales.

The Original Witcher: An Underrated Classic with Genuine Flaws

Setting the Stage: 2007 and a Different Gaming Landscape

When CD Projekt Red released the original Witcher in 2007, the gaming landscape looked fundamentally different. BioWare's Knights of the Old Republic had shown that Western audiences would embrace story-driven RPGs, but the standard remained action-heavy gameplay with narrative as window dressing. The Witcher arrived as something different: a game that treated narrative and moral choice as the primary mechanical pillar, with combat as a supporting element.

The game was technically impressive for its era. Built on a modified version of BioWare's Odyssey engine (used in Jade Empire), it featured a fully voice-acted protagonist, branching dialogue trees, and a story that changed based on player choices. In 2007, these weren't universal features in RPGs. The game also featured a visual style that stood out—dark, moody, and distinctly European in flavor, drawing directly from Andrzej Sapkowski's source material.

However, the game was undeniably rough. Combat felt clunky, character animations were limited by engine constraints, and the pacing suffered in places. Load times were brutal by modern standards, and the UI felt dated even at launch. The game required significant technical knowledge to run properly on most PCs, and performance optimization left much to be desired.

Why The Epilogue Matters: The Final Act Problem

Epilogues in game design face a unique challenge: they must provide narrative closure while avoiding the "ending fatigue" that can set in when players have already mentally finished the story. The epilogue should feel like a natural conclusion, not a forced extension. In The Witcher, the epilogue carries particular weight because the story's ending dramatically changes based on choices made throughout the game.

The issue Ganszyniec identified wasn't primarily narrative-related. It was mechanical. The epilogue features meditation as a core mechanic—the player must light campfires to rest and advance time. This is mechanically sound in theory: it grounds the passage of time in player agency and creates small pockets of exploration. But the implementation contained bugs that broke the entire system.

The specific bug Ganszyniec encountered prevented him from lighting one of the required campfires. Without this campfire, meditation wasn't possible, and the story progression stalled. For a story-driven game, this wasn't a minor inconvenience. It was a complete failure of the intended design, and Ganszyniec, realizing he had created the system himself, was visibly frustrated.

The Design Philosophy Behind The Witcher's Epilogue

The original Witcher's epilogue represents a specific design philosophy: use mechanics to ground narrative beats in player action. Rather than simply playing a cinematic sequence, the player must perform actions—light fires, meditate, observe the passage of time—that reinforce the emotional weight of the story's ending. This is sophisticated game design in theory.

However, there's a threshold where adding mechanics to narrative-driven gameplay can become counterproductive. Players who've invested 40-50 hours in a story want closure more than they want to solve mechanical puzzles. The epilogue is where emotional payoff should take priority over experimental mechanics. Ganszyniec's self-criticism suggests he recognized this, and that the implementation didn't serve the narrative goals it was designed to support.

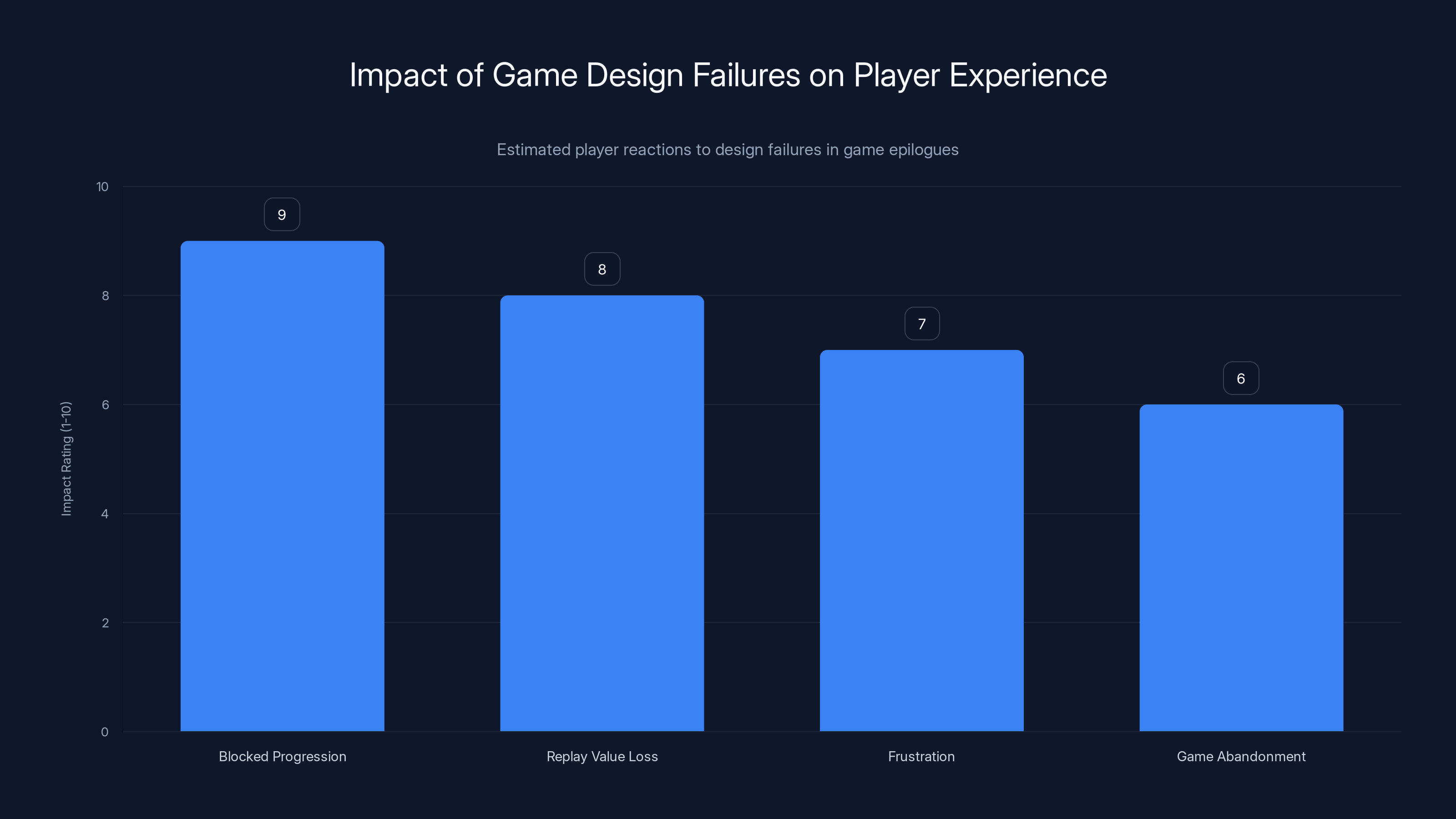

Design failures in game epilogues significantly affect player experience, with blocked progression rated highest in impact. Estimated data.

Crunch Time and Creative Compromise: The Reality of Game Development

How Last-Minute Development Timelines Create Problems

During his YouTube playthrough, Ganszyniec explicitly stated that "most of the epilogue, I was the one implementing it," and that he and Brzeziński worked on it during nights toward the end of production. This reveals a common truth in game development: core systems sometimes don't get the attention they deserve until the final stretch, when time pressure is at its maximum.

Game development crunch is well-documented in the industry, and its effects are predictable. Developers working extended hours make more mistakes. Testing becomes more superficial because there's less time for thorough QA cycles. Design decisions that would benefit from iteration instead get implemented once and shipped. New features don't get polished because the focus shifts entirely to stability and bug fixing.

The epilogue suffered from exactly this problem. What might have been a sophisticated narrative mechanic—grounding time progression in player action—became a source of frustration because it wasn't fully implemented or tested. The bug that prevented campfire lighting is the symptom, but the disease was the compressed timeline.

The Broader Pattern: Why Strong Games Sometimes Have Weak Endings

This isn't unique to The Witcher. Many acclaimed games feature strong narratives and mechanics that gradually become more uneven as the story progresses. There are several reasons this happens consistently:

Timeline Compression: Publishers typically set hard shipping dates. If a game isn't tracking toward completion, features get cut from late chapters before they get cut from early chapters, simply because there's less time to fix them.

Technical Debt: Early design decisions create technical constraints that become more limiting as scope expands. By the epilogue, developers are working within systems designed for entirely different scenarios.

Creative Fatigue: Teams working on a project for 3-5 years have less creative energy for final chapters than for opening acts. The novelty and excitement that drove early development has diminished.

Testing Resources: Most QA resources get allocated toward early-to-mid game content, ensuring players can actually reach the ending without crashing. The epilogue often gets tested less thoroughly simply because there's less time.

Ganszyniec's candor about this situation—rather than deflecting or making excuses—is refreshing precisely because these dynamics are so common in the industry.

Why Developers Rarely Admit to Design Failures Publicly

Most game developers, when appearing in public, carefully craft narratives about their work. They discuss their creative vision, the challenges they overcame, and the innovations they pioneered. They rarely say things like "that was stupid" about their own work, especially on public platforms where quotes can be immortalized and shared.

Ganszyniec's willingness to do exactly that—to play through his own game, encounter a mechanical failure, and openly criticize it—suggests either remarkable humility or a genuine confidence that players understand the context of crunch development and will appreciate his honesty. Either way, it's unusual enough to be noteworthy.

This kind of transparency serves multiple purposes. It humanizes game development, showing that even experienced professionals create things they're not satisfied with. It also demonstrates genuine investment in craft—Ganszyniec clearly cares about design quality, even if he couldn't achieve it within the constraints he faced. And it opens a conversation about what happened and why, rather than letting players speculate.

The Specific Design Failure: Campfires, Meditation, and Progression Blockers

Understanding The Meditation Mechanic

In The Witcher's epilogue, meditation serves as the primary mechanism for progressing through time and accessing story beats. To meditate, Geralt must light a campfire. The mechanic is straightforward: find the campfire, interact with it, advance time. However, the implementation contained a critical flaw that prevented one campfire from being lit properly.

This isn't a minor graphical bug or an audio issue. It's a progression blocker—a mechanic that prevents the core game loop from functioning. Without the ability to meditate at that specific location, story advancement stalls. Players attempting to complete the epilogue would find themselves stuck, unable to progress, unsure if they're missing something or if the game has broken.

The distinction matters because different types of bugs have different impacts. A cosmetic bug might frustrate players but won't prevent them from experiencing the narrative. A progression blocker, especially in a story-driven game, is a complete failure of the intended design. It turns your ending into a roadblock.

Why This Particular Bug Reveals Larger Design Problems

On the surface, Ganszyniec's criticism focuses on a specific campfire bug. But the real design failure extends beyond that single issue. The broader problem is that the entire progression system depended on a mechanic that wasn't robustly tested or implemented. Consider the design chain:

- Player must reach epilogue

- Epilogue depends on meditation mechanic

- Meditation depends on lighting campfires

- One campfire doesn't light properly

- Entire epilogue progression breaks

This reveals a design philosophy that lacked redundancy or fallback systems. A more robust design would have multiple paths to progression, or at minimum, would ensure that critical mechanics were thoroughly tested before shipping. The fact that a single bug could break the entire system suggests that the system itself was fragile.

Ganszyniec's self-criticism—"that is extremely stupid design"—likely refers not just to the bug, but to the underlying design decision to create a system with a single point of failure. That's a design philosophy issue, not just an implementation issue.

The Distinction Between Bugs and Bad Design

This is an important distinction in game development criticism. A bug is an implementation error—you designed the system correctly but failed to execute it. Bad design is a conceptual error—the system itself has flaws that make it problematic regardless of implementation quality.

Ganszyniec seems to be critiquing the latter. The meditation mechanic itself, as a design concept for grounding time progression, isn't inherently terrible. But creating a progression path that depends entirely on a single mechanic that isn't redundant, isn't well-tested, and requires precision implementation is bad design. It's vulnerable to failure in exactly the way it failed.

This is the kind of insight that only comes from experience. Developers working on modern AAA games have likely encountered similar problems and learned to avoid them through defensive design practices. The Witcher's epilogue is a case study in what happens when that defensive design isn't implemented under crunch conditions.

Modern AAA games typically have longer development times, more extensive QA and progression testing, and standard post-launch patching, compared to The Witcher's original development.

The Context: CD Projekt Red's History with The Witcher Series

From Polish Studio to Global Powerhouse

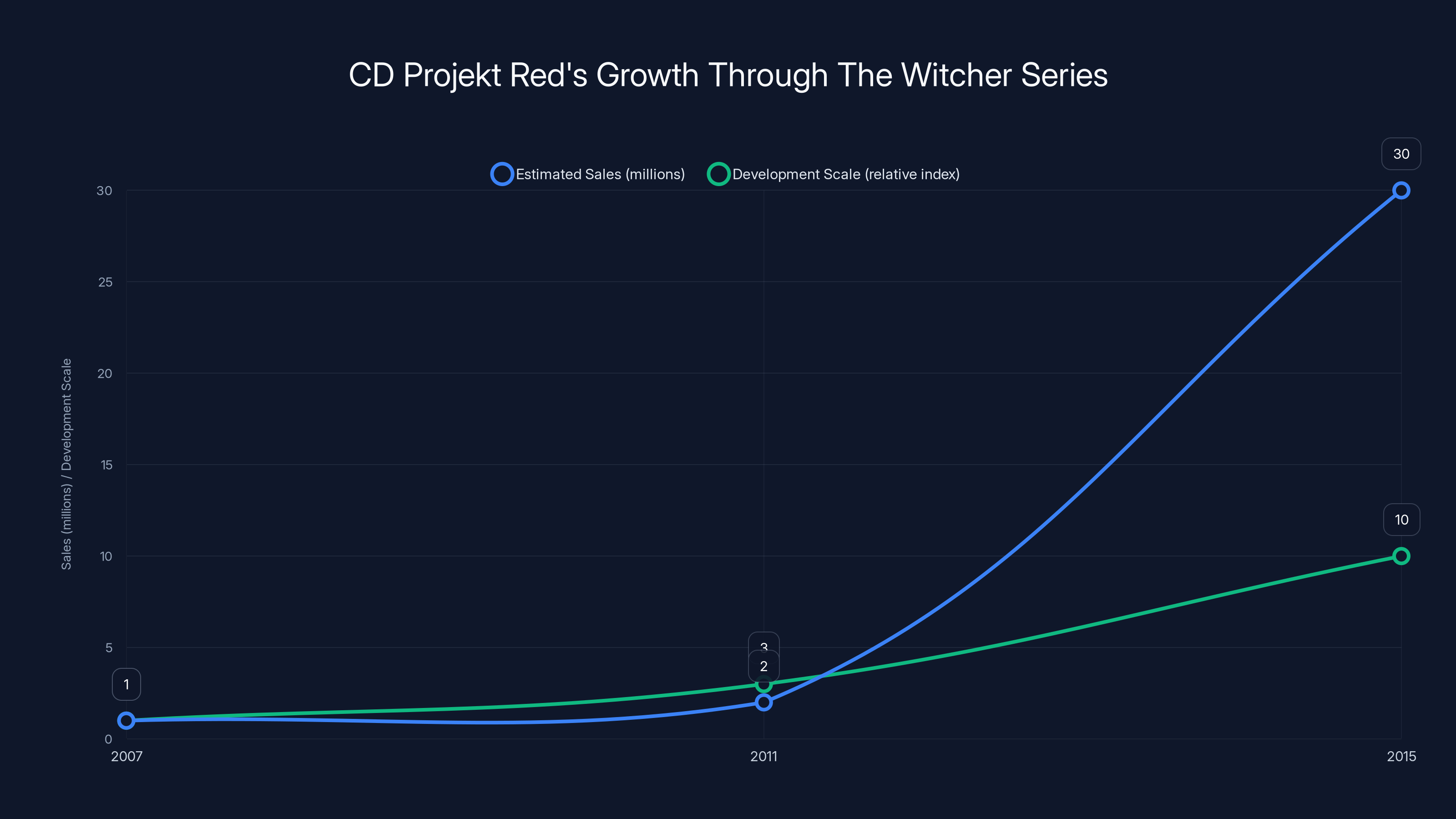

CD Projekt Red was far from an established powerhouse when they released the original Witcher in 2007. The studio was known primarily for distributing games in Poland and Eastern Europe. Developing an original RPG based on a Polish author's books was an ambitious bet for a regional publisher.

The original Witcher found an audience, but it was never the global phenomenon that The Witcher 3 became. That game, released in 2015, sold over 30 million copies and transformed CD Projekt Red from a respected regional studio into one of the world's largest game publishers. The success of The Witcher 3 gave the studio resources and credibility to expand its operations globally.

This trajectory is important context for understanding Ganszyniec's perspective on the original game. When he worked on the original Witcher, the studio was smaller, operating under tighter budgets, with less established development infrastructure. The crunch on the epilogue wasn't some luxury studio running inefficiently—it was a smaller team trying to ship a game on a tight timeline with limited resources.

The Evolution of CD Projekt Red's Design Philosophy

Comparing the original Witcher to The Witcher 3 reveals how much CD Projekt Red's design philosophy evolved. The Witcher 3 features extensive polish, multiple romance options, dozens of side quests with narrative depth, and a world that feels genuinely alive. The epilogue of The Witcher 3 is cinematic, emotionally impactful, and doesn't rely on obscure mechanics for progression.

This evolution reflects not just budgetary increases but a fundamental shift in how the studio approaches game design. Early games experimented more freely, accepting rough edges as part of the creative process. Later games prioritized polish and accessibility, ensuring that the core experience was robust enough to be enjoyed by millions of players with varying skill levels and patience for obtuse mechanics.

Ganszyniec's criticism of the original game's epilogue makes sense in light of this evolution. He's not criticizing a game made in 2007 by the standards of 2007. He's critiquing it with two decades of additional game development experience, with knowledge of better approaches that have been proven in The Witcher 3 and elsewhere in the industry.

Why Game Developers Work in Crunch: The Economics of Publishing

The Timeline Pressure Problem

Understanding why games ship with unpolished elements requires understanding the economics of game publishing. When a publisher sets a release date, that date becomes almost immovable for financial reasons. Marketing campaigns are planned around it. Retail shelf space is allocated. Supply chains are coordinated. Changing the date becomes increasingly expensive as you get closer to launch.

Developers are aware of this pressure. They know that asking for more time becomes harder as the deadline approaches. This creates a perverse incentive structure where developers take on work during crunch rather than asking for extensions. It's often faster to work nights and weekends than to have conversations about timeline extensions with publisher management.

The original Witcher's epilogue is a direct result of this dynamic. The deadline was fixed. The scope probably wasn't as polished as developers wanted. Rather than cutting content or asking for more time, the team worked extended hours to get something shippable finished. The result was functional but rough—exactly what happens in crunch situations.

The Review Deadline Factor

For a 2007 game release, review embargoes lifted before launch, and reviews typically appeared the day before or day of release. This means the game had to be feature-complete and at least minimally stable weeks before shipping, with no opportunity to patch in the epilogue if something wasn't working.

Modern game development benefits from day-one patches and post-launch content updates. Issues that would have been catastrophic in 2007 can now be fixed after release. The original Witcher didn't have this luxury. If the epilogue had major bugs at shipping, there was no option to fix it later. It had to work at launch, or it didn't work at all.

This added pressure to get the epilogue functional, even if not fully polished. Shipping something rough was better than shipping something that blocked progression entirely. So the team did exactly that—created something that technically worked but had enough flaws that the lead designer would later feel compelled to publicly criticize it.

Timeline compression and resource constraints are major factors impacting game quality. Estimated data based on industry trends.

The Remake Opportunity: Fool's Theory and Unreal Engine 5

Why Remaking The Original Witcher Makes Sense

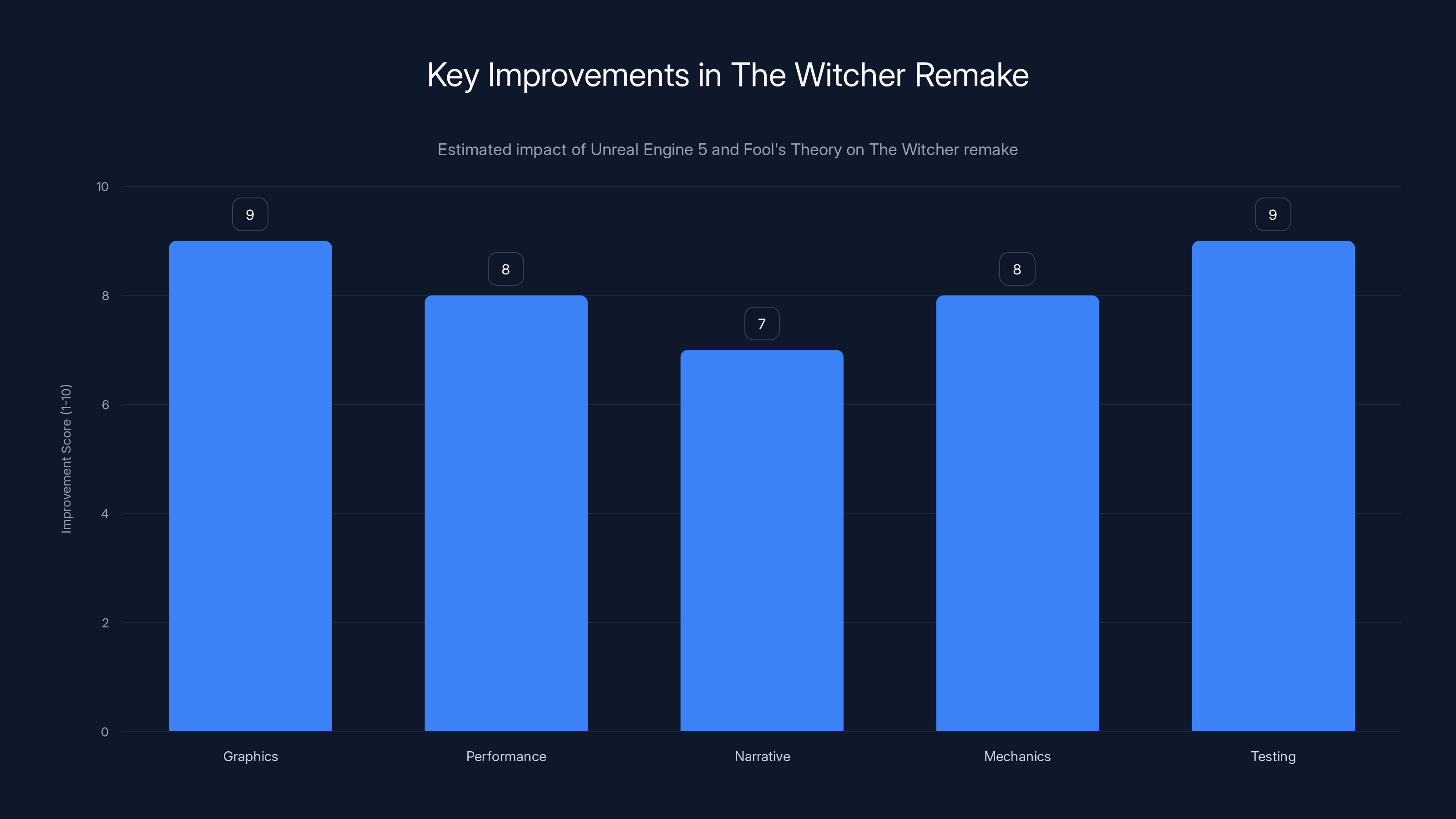

In 2022, CD Projekt Red announced that Fool's Theory would develop a full remake of the original Witcher using Unreal Engine 5. This isn't a simple upscaling or a graphics update. It's a complete reconstruction of the game using modern technology and design practices.

This announcement effectively acknowledges what Ganszyniec was pointing out in his playthrough: the original game, while narratively important and mechanically interesting, was rough in execution. A remake provides an opportunity to preserve what made the original special while fixing the design issues that plagued it.

Fool's Theory, the developer leading the remake, has experience with substantial game projects. Their involvement suggests that CD Projekt Red is serious about getting this remake right, rather than treating it as a quick cash-in on the franchise's current success.

What the Remake Can Address

With Ganszyniec's public criticism now on record, the remake developers know exactly what needs fixing. The epilogue can be redesigned with better progression mechanics, improved testing, and more robust systems. The entire game can be updated with modern UX standards, better performance optimization, and cleaner code that won't require extended crunch periods to polish.

Moreover, remaking the game provides an opportunity to address narrative issues as well as mechanical ones. Some of the original Witcher's storytelling is excellent, while other elements feel dated or awkward. A remake can preserve the narrative strengths while smoothing out the rough edges in how those stories are told.

The use of Unreal Engine 5 is particularly significant. UE5 comes with built-in systems for optimization, better debugging tools, and more robust testing frameworks than the modified Odyssey engine used in the original. This infrastructure makes it harder to accidentally ship with progression blockers, because the engine itself helps catch these issues.

The Broader Pattern: Remakes as Design Corrections

Ganszyniec's criticism isn't unique just because a developer critiqued their own work. It's significant because it shows why remakes are valuable for the industry. Games like Resident Evil 2, Final Fantasy VII Remake, and the upcoming original Witcher remake provide opportunities to fix design mistakes from the original while preserving the core experience that made the game special.

This is fundamentally different from a simple remaster, which updates graphics and performance while keeping the original game's systems intact. A remake allows for systematic redesign of problematic elements. The epilogue progression system can be replaced entirely. The meditation mechanic can be reimagined or replaced. Or it can be kept but implemented robustly so it doesn't break under any circumstance.

Game Design Lessons: What the Epilogue Teaches About Systems Design

Redundancy in Progression Systems

One core lesson from the epilogue's failure is the importance of redundancy in critical systems. If progression depends on a single mechanic, and that mechanic fails, the entire game breaks. Robust systems design includes fallbacks—alternative paths forward if primary systems fail.

A better design might have included:

- Multiple campfires: If one is bugged, others still work for meditation

- Alternative progression paths: Even if meditation fails, players can advance through dialogue or other mechanics

- Graceful degradation: If the specific mechanic fails, the game doesn't block progression but instead offers an alternative path forward

- State tracking: The system tracks whether meditation has occurred, preventing double-completion or missed content

These aren't complex solutions. They're standard defensive programming practices that become especially important in story-driven games where player progression is tied to narrative advancement.

Testing for Progression Blockers

Any game development process should include specific testing focused on progression blockers. The QA team should have a defined critical path—the minimum set of actions required to complete the game—and that path should be tested repeatedly on clean saves, after loading saves, and with various player inputs.

The fact that a campfire bug made it to shipping suggests that either (a) the critical path wasn't thoroughly tested, or (b) testing resources were limited by crunch conditions. Most likely both were factors. A more robust testing process would have caught this issue during development, and a more generous timeline would have allowed fixing it before shipping.

Mechanics Serving Narrative vs. Mechanics for Their Own Sake

The original design concept behind the epilogue's meditation mechanic is interesting: ground narrative time-progression in player agency rather than cutscenes. This is a legitimate design goal that can enhance player investment.

However, there's a difference between a mechanic that serves narrative and a mechanic that gets in the way of narrative. In the epilogue of a story-driven game, players have already invested significant time in the narrative. The epilogue should primarily deliver on narrative payoff. Any mechanics should enhance that experience, not create friction.

Ganszyniec's criticism suggests that the meditation mechanic, as implemented, created friction rather than serving the narrative. It added complexity to what should be a straightforward ending experience. This is a design lesson: understand what players need at each stage of the game. Early game can afford experimental mechanics. Late game should prioritize delivering on the narrative promise.

CD Projekt Red's sales and development scale grew significantly from 2007 to 2015, highlighted by The Witcher 3's success with over 30 million copies sold. Estimated data.

The Transparency Question: Why Developers Should Critique Their Own Work

Breaking the Glossy Developer Narrative

Most game marketing emphasizes developer passion, creative vision, and overcoming technical challenges. These narratives are often true, but they're also curated. Developers highlight the decisions they're proud of and minimize the ones they regret. Ganszyniec's willingness to break this pattern is refreshing.

When a developer publicly states that their own work contains "extremely stupid design," several things happen. First, it makes the developer more credible. Audiences recognize that this is someone being honest rather than performing. Second, it opens space for more honest conversations about game design—what works, what doesn't, and why.

Third, it demonstrates that even experienced professionals create work they're not satisfied with. This is valuable context for players and industry observers. It humanizes game development, showing that failure and compromise are part of the process, not exceptions.

The Risk-Reward Calculation

There are risks to developers being this candid. Public criticism of your own work could be used against you—in hiring discussions, in industry politics, or in media narratives. Ganszyniec presumably made this trade deliberately, deciding that the value of honesty outweighed the risks.

This suggests confidence either in his own track record or in the gaming community's understanding that crunch development creates these situations. The original Witcher's flaws haven't prevented CD Projekt Red from creating The Witcher 3. Ganszyniec's willingness to acknowledge the epilogue's problems probably enhances rather than damages his reputation among people who understand game development.

Building Trust Through Transparency

In an industry where developers are often protective about their work, transparency becomes a differentiating factor. When a developer acknowledges problems openly, players are more likely to trust their future decisions. They're more likely to believe that if a developer ships something, the developer is satisfied with it, because you know they'll tell you if they're not.

This has broader implications for how the industry communicates with audiences. If more developers were this candid about their process—discussing what worked, what didn't, and why—the industry would benefit. Players would better understand the constraints game development operates under. Aspiring developers would have more realistic expectations about the work.

The Wider Industry Context: How Modern Games Avoid These Problems

Extended Development Timelines

Modern AAA games often spend 4-6 years in development, compared to the roughly 2-3 years The Witcher spent. This extended timeline allows for more thorough iteration, testing, and polish. The tradeoff is higher budgets and longer waits between releases, but the results tend to be more polished experiences.

Ganszyniec's epilogue issues likely wouldn't occur in a modern development context with this extended timeline. Late-game content would get as much attention as early content because there would be time to iterate on both. Testing would be more thorough. Crunch would be less intense because the timeline would provide buffer for unexpected issues.

Structured Testing Processes

Modern game development includes dedicated QA phases focusing on progression, stability, and critical path completion. These phases typically run months before launch and include systematic testing of all paths to beating the game. The focus is specifically on finding and fixing progression blockers before release.

The original Witcher's development didn't have the benefit of these standardized processes. Testing methodology has improved significantly over the past two decades. A 2024 game going through this testing process would almost certainly catch the campfire bug before shipping.

Post-Launch Support and Patching

Modern games can be patched after release. The day-one patch is now standard in the industry. This removes some of the pressure to be perfect at launch and allows developers to fix issues that slip through testing. This isn't an excuse for shipping buggy games, but it does provide a safety valve for issues like the campfire bug.

The original Witcher didn't have this option. Everything had to work at launch. This contributed to the pressure that forced the epilogue into crunch development. Modern development timelines can afford more flexibility because patches are expected.

The remake of The Witcher using Unreal Engine 5 is expected to significantly enhance graphics, performance, and testing capabilities, while also improving narrative and mechanics. Estimated data based on typical UE5 enhancements.

Player Impact: How Design Failures Affect the Game Experience

Progression Frustration and Replay Value

For a player attempting to complete the original Witcher's epilogue, encountering the campfire bug would be deeply frustrating. They've already played 30-50 hours of game. They've made choices that shaped the story. They're close to the ending. And suddenly, they hit a wall—a mechanic that doesn't work.

The immediate impact is blocked progression. But the longer-term impact is on replay value. A player who hits a progression blocker is less likely to restart and try alternative paths. They're more likely to move on to other games, leaving the original incomplete.

This has implications for how players remember the game. The epilogue is the last thing they experience. A frustrating epilogue colors the entire experience retroactively. This explains why Ganszyniec, with years of perspective, still criticizes the epilogue. It's not just a late-game issue—it's the final impression players have of the game.

Difficulty and Accessibility

The epilogue's reliance on specific mechanics also raises accessibility questions. Players with certain disabilities might struggle with the precision required to light a specific campfire. For elderly players or players with limited time, a progression blocker is more frustrating than it would be for others. Robust, well-tested progression systems need to be accessible to a wide range of players.

This is another area where modern game design has improved. Accessibility testing is now standard practice. Alternative paths for progression are considered essential, not optional. A modern remake would include multiple ways to progress through the epilogue, ensuring that no single mechanic blocks players from reaching the ending.

The Emotional Cost of Failure

Beyond the mechanical implications, there's an emotional dimension to progression blockers. Players invest emotionally in games, especially story-driven games. They want to know how the story concludes. A mechanic that prevents that conclusion violates the implicit contract between developer and player.

Ganszyniec's self-criticism reflects this understanding. He wasn't just annoyed at a technical bug. He recognized that his design failed to deliver on a fundamental promise: letting players experience the ending of the story they'd invested in.

The Future: How the Remake Can Learn from These Failures

Opportunities for Design Improvement

With Fool's Theory developing the remake and Unreal Engine 5 providing modern infrastructure, there are numerous opportunities to improve on the original epilogue. The progression system can be redesigned entirely. Rather than depending on a single meditation mechanic, progression can use multiple paths. Story advancement can be less dependent on specific mechanics and more integrated into narrative beats.

Alternatively, the meditation mechanic can be retained but implemented robustly. Unreal Engine 5's tools make it easier to test mechanics thoroughly, track state reliably, and implement fallback systems. The same concept that failed in the original could work perfectly in a remake with proper implementation.

Narrative Opportunities

Beyond mechanical improvements, a remake provides narrative opportunities. The epilogue's story can be expanded. Branches that were cut due to crunch can be restored. Additional endings based on specific playstyles can be added. The epilogue can be given the narrative attention it deserves.

The original game's story is solid, but rushed. A remake can take a strong narrative foundation and polish it into something exceptional. Ganszyniec presumably has ideas about what he wanted the epilogue to be, given unlimited time and resources. The remake might finally allow him to realize that vision.

Preservation and Player Experience

Ultimately, the remake serves preservation. The original Witcher's story is important to the franchise history and to RPG history more broadly. But the original's technical limitations make it increasingly difficult to experience. A remake ensures that future players can experience the story without struggling with early-2000s engine limitations, control schemes, and UI conventions.

Ganszyniec's playthrough and criticism accelerated this preservation effort. By publicly acknowledging what needed fixing, he provided the remake team with a clear roadmap of what required attention.

Lessons for Independent Developers: Applying These Insights to Smaller Projects

Protecting Your Timeline

The epilogue's problems stem from timeline compression. Indie developers often face even tighter timelines than CD Projekt Red did in 2007. Protecting your development timeline becomes crucial. This means:

- Setting realistic scopes from the beginning

- Prioritizing ruthlessly—cut features rather than extend timelines

- Building in testing time before the final deadline

- Planning for contingencies rather than assuming perfect execution

- Communicating timeline pressures to your audience early rather than shipping unfinished work

Some of the most successful indie games are successful because developers knew their limitations and designed within them. That's a stronger approach than attempting ambitious scope and shipping rough work due to crunch.

Testing on a Budget

Independent developers typically can't afford the QA infrastructure of large studios. But they can implement systematic testing practices that catch progression blockers without expensive resources:

- Playthrough testing: Regularly complete the game from start to finish

- Variation testing: Try different playstyles to see if any break progression

- Save loading: Test progression after loading saves from different points

- Edge case testing: Try unusual inputs and see what breaks

These aren't replacement for professional QA, but they catch major issues without requiring a dedicated QA team.

Design Defensibility

Design your systems defensively. Assume mechanics will fail in unexpected ways. Build in redundancy. Provide alternative paths forward. This makes your game more robust and more player-friendly simultaneously.

A single progression path that depends on a specific mechanic working perfectly is fragile. Multiple paths that can accommodate failures are resilient. Defensive design doesn't add much complexity, but it dramatically improves player experience.

Industry Accountability: What Ganszyniec's Criticism Means for Developer Standards

Setting Precedent for Honesty

When a lead developer publicly critiques their own work, it sets a precedent. It signals that accountability and transparency are valued in the industry. It makes it harder for other developers to hide behind marketing narratives when they know that frank assessment is possible and respected.

This matters because the industry has long struggled with developers shipping incomplete or broken work and expecting post-launch patches to fix it. Ganszyniec's willingness to acknowledge that the original game's epilogue had problems—and that he shared responsibility for those problems—demonstrates a commitment to craft that should be aspired to.

The Role of Public Playthrough

Ganszyniec's choice to conduct his playthrough publicly, rather than speaking about these issues in an interview, makes the criticism more credible. We're seeing the actual bug, not hearing about it secondhand. We're watching someone encounter the issue and react honestly, rather than reading a polished statement about it.

This format—developers playing their own games publicly—should become more common. It provides genuine insights into how games actually work, how they fail, and what developers think about their own work. It's much more valuable than standard promotional content.

Implications for Quality Standards

If more developers publicly acknowledge and critique their own work, it raises industry quality standards. Publishers become less tolerant of known issues at launch if developers are willing to openly discuss them. Players set higher expectations if they know that developers recognize quality problems.

Ganszyniec's criticism won't single-handedly change the industry. But it's a data point. It shows that transparency doesn't damage a developer's reputation—it enhances it. It shows that accountability is possible. It suggests that the path forward includes more honest assessment of our own work.

Looking Forward: The State of Game Remakes and Preservation

Why Remakes Matter More Than Ever

As games age, they become increasingly difficult to play due to technical changes, discontinued platforms, and outdated interfaces. A game released on PC in 2007 might not run on modern Windows without significant tweaking. Console games from that era are unplayable once the hardware fails and isn't replaceable.

Remakes solve this problem by rebuilding games on modern infrastructure. The original Witcher remake, once released, will be the definitive way to experience that game's story for decades to come. The original will be preserved as historical artifact, while the remake serves as the accessible version for new players.

This is increasingly important as games are recognized as cultural artifacts worthy of preservation. Film archives preserve important films. Museums preserve important artworks. Game remakes serve a similar function for interactive media.

The Creative Opportunity

Remakes also provide creative opportunities. They're not just preservation—they're reinterpretation. A remake can take a game's core ideas and explore them with modern design sensibilities, new narrative possibilities, and enhanced technical capabilities.

The original Witcher remake represents an opportunity to take a groundbreaking narrative experience and make it truly work as designed. If Ganszyniec's vision for the epilogue was constrained by timeline and technical limitations, the remake can realize it fully.

The Broader Industry Pattern

The success of remakes like Resident Evil 2, Final Fantasy VII Remake, and the upcoming Witcher remake suggests that this is a sustainable approach to game development. Rather than only creating new IPs, studios can also carefully rebuild legacy titles. This provides economic stability while honoring gaming history.

Conclusion: From Criticism to Improvement

Artur Ganszyniec's candid criticism of the epilogue he largely created represents something important: a moment where the gap between ambition and execution becomes visible and acknowledged. The original Witcher's epilogue was conceived as a way to ground narrative progression in player agency, a sophisticated design goal. But the execution, constrained by crunch and timeline pressure, fell short.

That failure isn't unique to The Witcher. It's part of a broader pattern in game development where timeline compression, technical debt, and resource constraints force developers to ship work that's rougher than they'd prefer. What makes Ganszyniec's situation noteworthy is his willingness to publicly acknowledge this, rather than defending the work or pretending it was fully realized.

This transparency serves multiple purposes. It humanizes game development, showing that even accomplished professionals create work they're not satisfied with. It provides valuable lessons about defensible design, robust testing, and the importance of protecting development timelines. It demonstrates that the original Witcher, while flawed, was created by people who cared about quality and understood those flaws.

The upcoming remake by Fool's Theory using Unreal Engine 5 represents an opportunity to address these issues fully. With modern technology, extended timelines, and the benefit of Ganszyniec's direct feedback about what needs fixing, the remake can realize the vision that crunch prevented in the original. It can make the epilogue work as designed—a mechanically and narratively satisfying conclusion to the game.

Ultimately, Ganszyniec's criticism isn't a failure. It's a data point that helps us understand game development, the pressures developers operate under, and the gap between what we aim for and what we ship. It's an invitation to think about better ways to develop games, with more reasonable timelines, more robust testing, and more defensive design. And it's a reminder that transparency about our failures is more valuable than silence about them.

The original Witcher's epilogue will be remembered not just for its flaws, but for the developer willing to say "that was stupid design" and mean it. That honesty is rare enough in an industry built on marketing narratives to be worth celebrating—and learning from.

FAQ

What was Artur Ganszyniec's main criticism of The Witcher's epilogue?

Ganszyniec criticized the epilogue's meditation and campfire mechanics as "extremely stupid design." The core issue was a progression blocker—a bug preventing a specific campfire from being lit, which made meditation and story advancement impossible. This was particularly problematic because the epilogue depended entirely on this mechanic working correctly.

Why was the epilogue created during crunch time?

The original Witcher's epilogue was largely developed during the final crunch period of the game's production, mostly by Ganszyniec and project lead Jacek Brzeziński working nights toward the end of development. This compressed timeline meant less testing, less iteration, and less polish than would have been possible with more extended development. The budget and team constraints of a 2007 regional studio further limited resources.

How does this compare to modern game development practices?

Modern AAA games typically spend 4-6 years in development with dedicated QA phases, systematic progression testing, and extended testing specifically for progression blockers. Modern engines like Unreal Engine 5 provide better tools for catching these issues automatically. Additionally, post-launch patching is now standard, removing some pressure to be perfect at launch, though developers still aim for stability.

What is The Witcher remake attempting to do differently?

The Witcher remake, being developed by Fool's Theory using Unreal Engine 5, provides an opportunity to redesign problematic systems like the epilogue's mechanics. Modern tools and extended timelines allow for more robust implementation. The progression system can be redesigned entirely, or the meditation mechanic can be retained but implemented thoroughly enough that bugs like the original's campfire issue won't occur.

Why did Ganszyniec publicly criticize his own work?

Ganszyniec's willingness to play through the game publicly and acknowledge its problems demonstrates confidence in his track record and appreciation for transparency. Rather than defending rough work or pretending it was fully realized, he acknowledged the constraints he worked under and the compromises that resulted. This kind of honesty actually enhances developer credibility and opens productive conversations about game design challenges.

What does this teach us about game design philosophy?

The epilogue's failure illustrates several important principles: defensive design with redundancy is more important in progression systems than elegant minimal design, late-stage crunch produces rough results, and mechanics should serve narrative goals rather than existing for their own sake. Additionally, it demonstrates that progression blockers are especially damaging in story-driven games where players have significant emotional investment.

How has CD Projekt Red changed since The Witcher's original release?

CD Projekt Red has evolved from a regional Polish publisher to a global studio with dramatically increased resources and development infrastructure. The Witcher 3's design demonstrates lessons learned from the original game's rough edges. Modern CD Projekt Red games feature extended development, dedicated testing phases, and polished systems throughout. The decision to remake the original game shows the studio's commitment to preserving its history while improving upon it.

What can indie developers learn from this situation?

Independently-developed games face even tighter timelines than The Witcher did. Key lessons include: protect your development timeline ruthlessly, build defensive design practices from the beginning (redundancy, alternative paths, fallback systems), implement systematic testing practices within budget constraints, and communicate timeline realities to players early rather than shipping rushed work. Many successful indie games succeed specifically because developers designed within their constraints rather than overcommitting on scope.

Why is this criticism significant for the gaming industry?

Developer transparency about their own work is relatively rare in an industry built on marketing narratives. Ganszyniec's willingness to publicly acknowledge design failures sets a precedent that accountability and honesty are valued. This could influence industry standards toward more transparent discussion of crunch, compromise, and the gap between ambition and execution. It also provides valuable case studies for understanding game development challenges.

When will The Witcher remake release?

The original Witcher remake is in development by Fool's Theory but no specific release date has been announced. CD Projekt Red has stated that the remake is being "carefully supervised" by their development staff, suggesting a commitment to quality over speed. Given that the studio is primarily focused on The Witcher 4, the remake is likely several years from release.

Final Thoughts

Artur Ganszyniec's candid playthrough of the original Witcher represents a rare moment of industry transparency. His willingness to critique his own work provides valuable lessons about game development, the impacts of crunch, and the importance of defensive design. The upcoming remake offers an opportunity to address these historical issues while preserving what made the original special. For anyone interested in game development, design philosophy, or how studios evolve over time, this situation offers rich material for understanding the realities of creating games under pressure.

Key Takeaways

- Artur Ganszyniec publicly criticized the epilogue's progression-blocking campfire mechanics as 'extremely stupid design,' showing rare developer transparency

- The epilogue was created during crunch time by Ganszyniec and project lead Jacek Brzeziński, illustrating how timeline compression creates rough design outcomes

- Progression blockers—mechanics that prevent story advancement—are especially damaging in narrative-driven games with significant player emotional investment

- Modern game development practices (extended timelines, dedicated QA testing, modern engines) would prevent the kind of design failures that plagued the original Witcher's epilogue

- The upcoming remake by Fool's Theory using Unreal Engine 5 provides an opportunity to address these design issues while preserving the original's narrative strengths

Related Articles

- Metal Gear Solid 4 Leaves PS3: Console Exclusivity Death [2025]

- God of War Remake Trilogy & Sons of Sparta: What Gamers Need to Know [2025]

- Metal Gear Solid Master Collection Vol. 2: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- Blizzard QA Workers Win Historic Union Contract: What It Means [2025]

- Genigods: Nezha PS5 Action Game Deep Dive [2025]

- Reviving Anthem After Server Shutdown: Why EA's Frostbite Engine Makes It So Hard [2025]

![The Witcher's Story Lead Blasts His Own Epilogue Design [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-witcher-s-story-lead-blasts-his-own-epilogue-design-2025/image-1-1771416742062.jpg)