US Removes Spyware Executives From Sanctions: What Actually Happened [2025]

Last week, something strange happened in the world of cybersecurity policy. Three executives tied to one of the world's most invasive commercial spyware platforms were quietly delisted from the US government's sanctions list. No press conference. No statement explaining why. Just a brief OFAC notice, and they were off the hook.

Merom Harpaz, Andrea Nicola Constantino Hermes Gambazzi, and Sara Aleksandra Fayssal Hamou had been on the Office of Foreign Assets Control's Specially Designated Nationals list since March and September of 2024. These weren't small-time operators either. Harpaz was a top executive at Intellexa Consortium. Gambazzi owned controlling interests in the parent companies. Hamou handled the offshore corporate structure that kept everything running.

They were sanctioned for one reason: Intellexa Consortium developed and marketed Predator spyware—a tool so powerful it can unlock your phone without you even clicking anything. The kind of weapon governments use to surveil dissidents, journalists, and human rights lawyers.

So why'd they get delisted? Nobody's saying.

This article breaks down exactly what happened, who these people are, why they mattered enough to sanction in the first place, and what their sudden removal from the sanctions list tells us about how government actually handles cybercriminal networks.

TL; DR

- The delisting: Three Intellexa Consortium executives disappeared from OFAC's sanctions list with zero explanation or official justification

- Who they were: Merom Harpaz (top executive), Andrea Gambazzi (beneficial owner of parent companies), Sara Hamou (offshore corporate specialist)

- Why they were sanctioned: Direct ties to Predator spyware, a commercial tool sold to authoritarian governments for mass surveillance

- The problem: Predator remains active and dangerous—recent reports show it targeting Pakistani human rights lawyers

- The bigger issue: The US government appears to have reversed course without transparency, raising questions about diplomatic pressure or backdoor negotiations

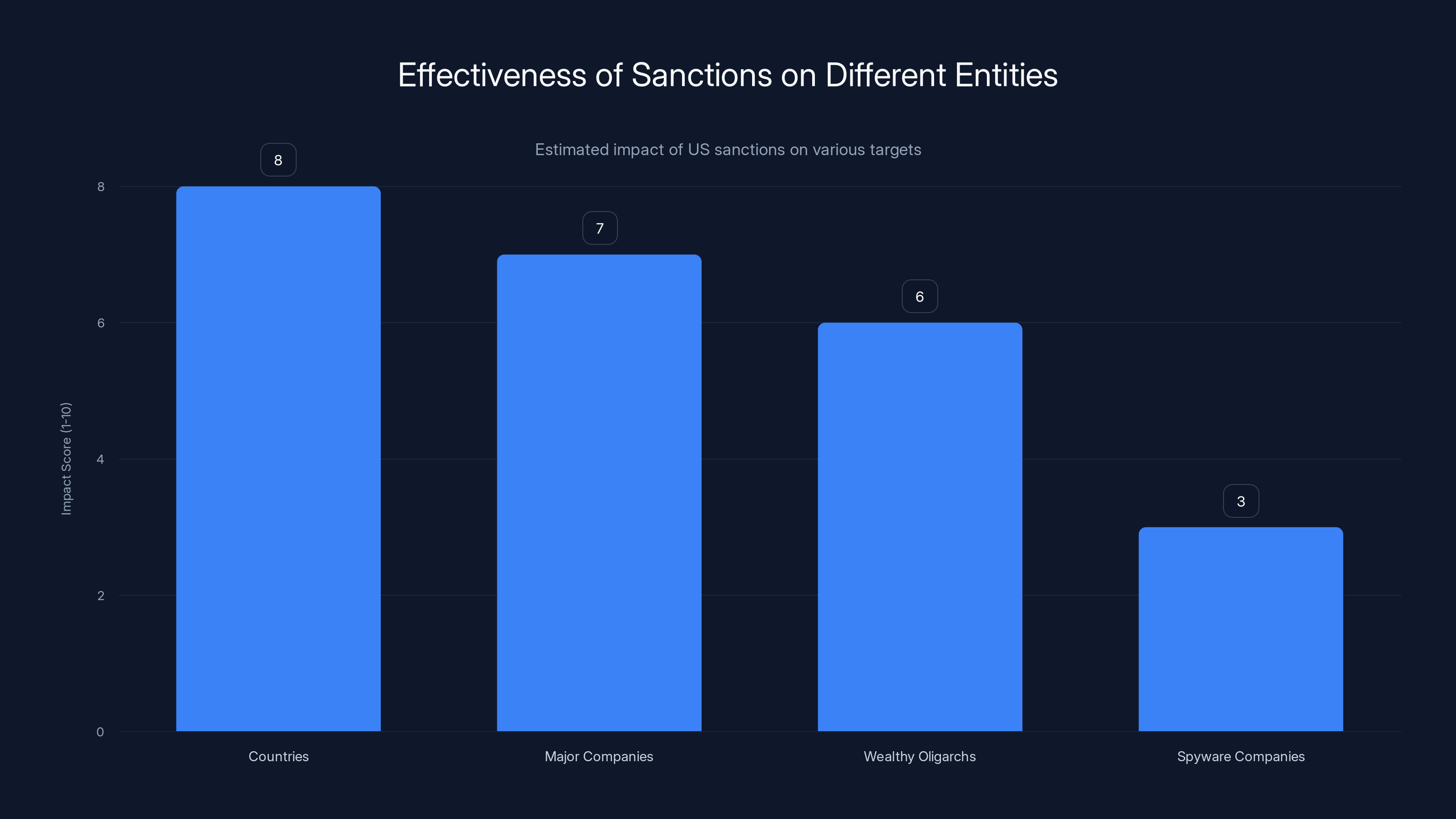

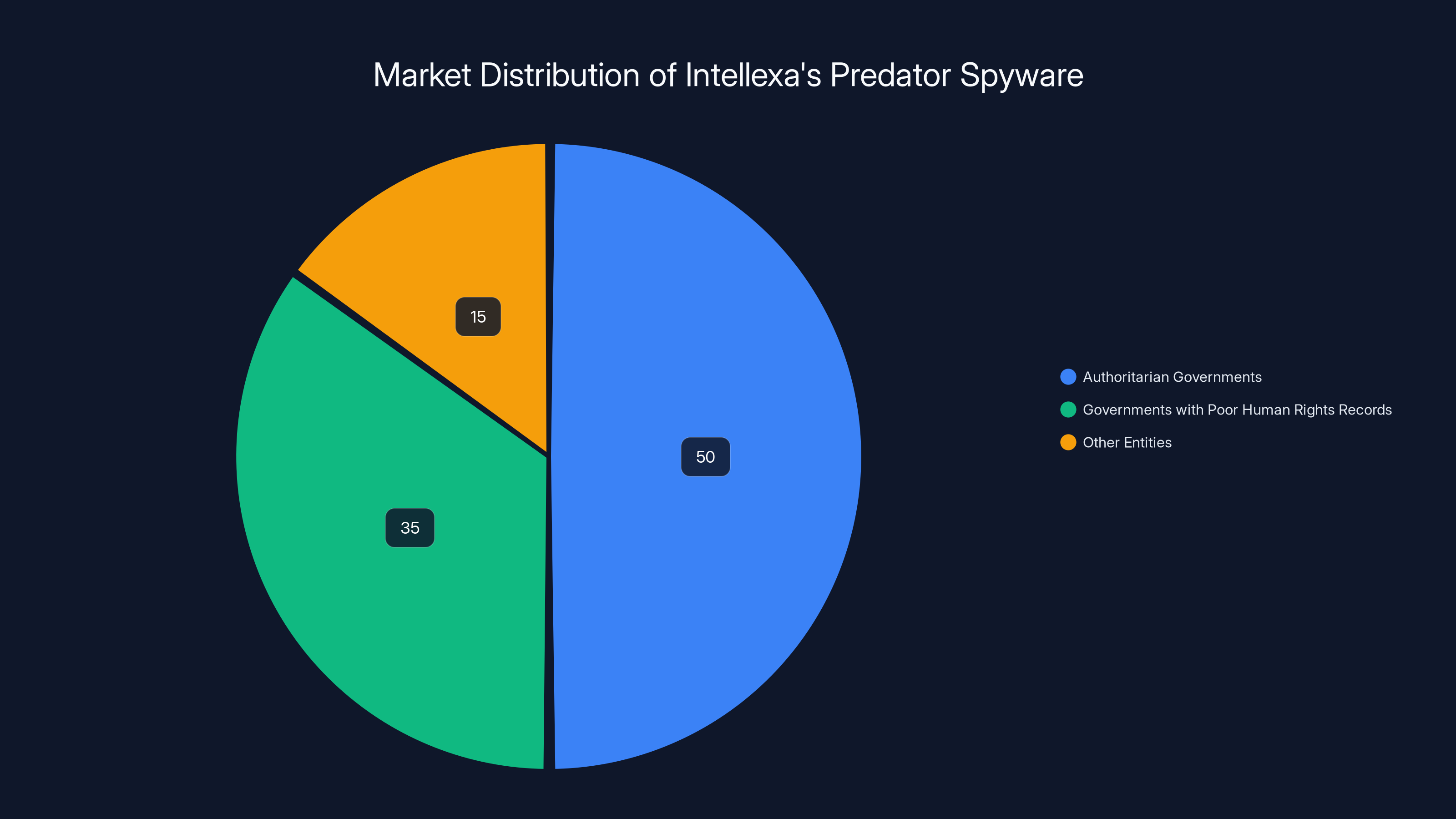

Sanctions are most effective against countries and major companies, with spyware companies being less affected due to their international and decentralized nature. Estimated data.

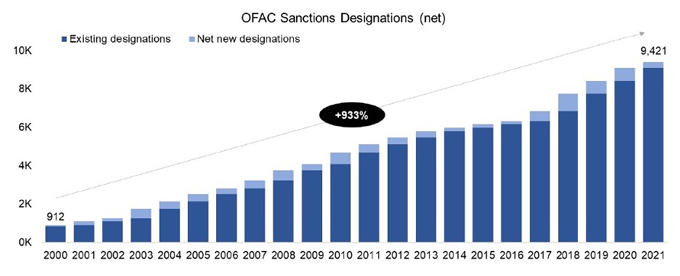

Understanding the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) and Sanctions Lists

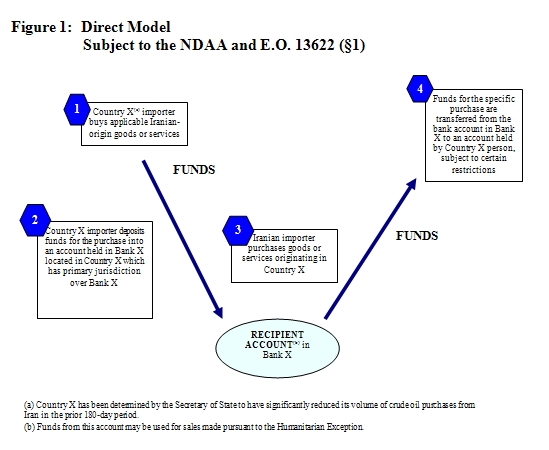

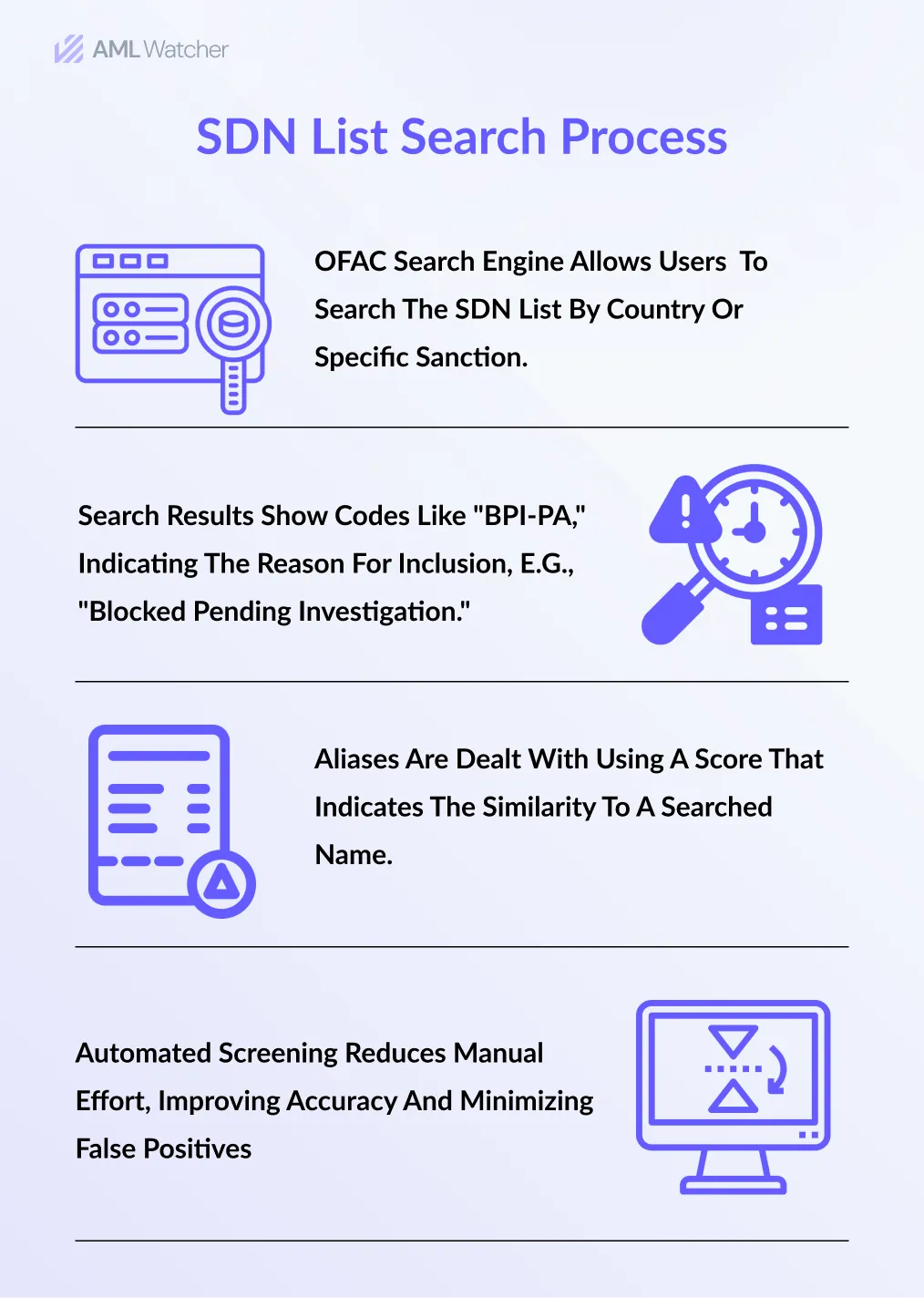

OFAC is the enforcement arm of the US Treasury Department. When they put someone on their Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list, it's not a slap on the wrist. It's a financial death penalty.

Here's what being on the SDN list actually means. Any assets you control inside the United States get frozen immediately. Banks have to block accounts. Investment firms must liquidate holdings. Real estate transactions halt mid-closing. For companies, it's worse—US businesses and citizens become legally prohibited from doing business with you. If they violate that prohibition, they're looking at civil penalties up to $250,000 per violation and potential criminal charges carrying prison time.

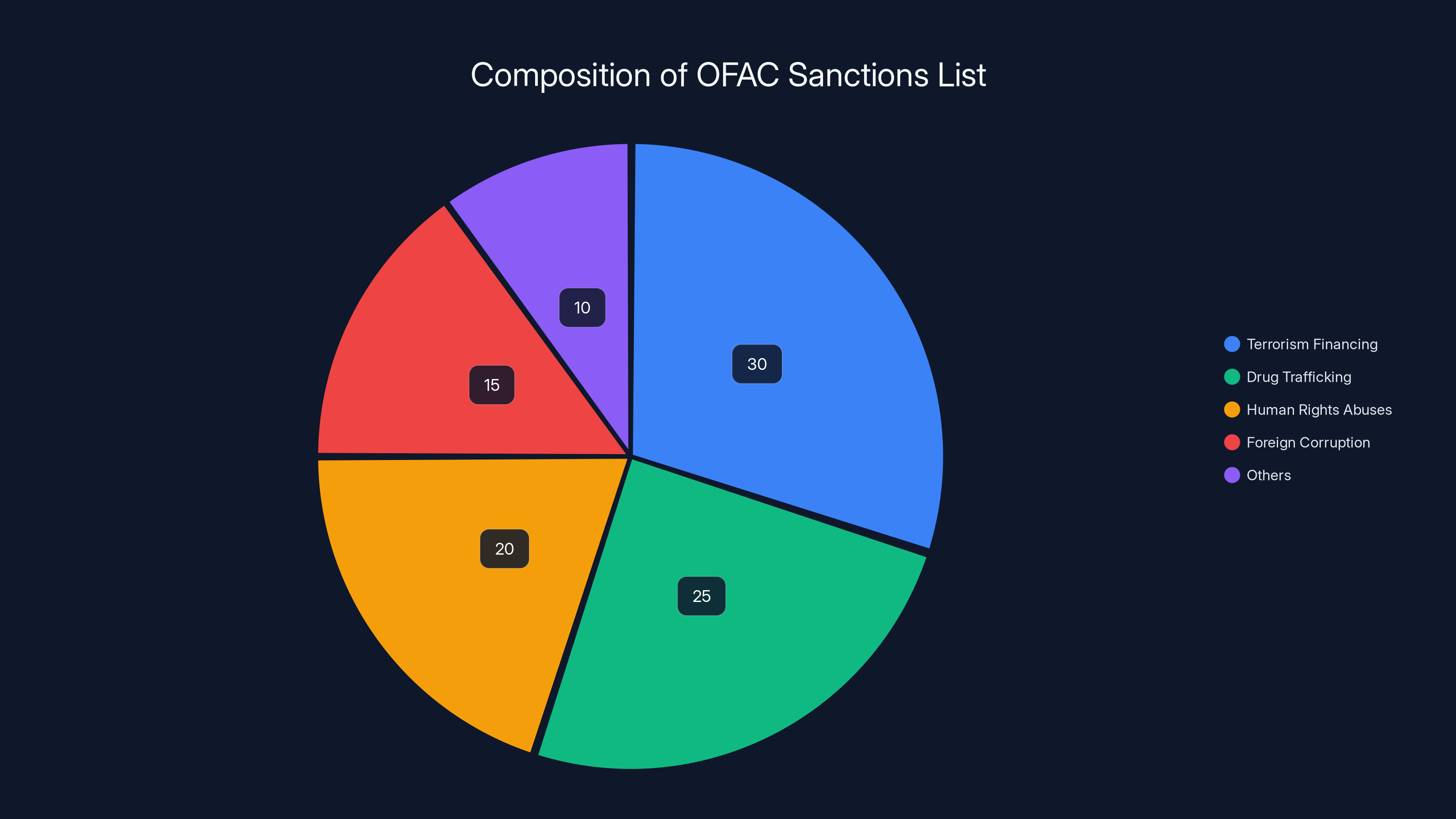

The list exists to target terrorism financing, drug trafficking, human rights abuses, and foreign corruption. It's the nuclear option in financial sanctions.

When OFAC adds someone to the SDN list, there's usually a supporting document explaining the legal basis. They cite specific violations, identify which sanctions programs apply, and provide the enforcement reasoning. When they remove someone, the same process should happen in reverse—new facts that contradict the original evidence, or a change in circumstances that makes the sanctions counterproductive.

In this case, they removed three major actors in a commercial spyware network and provided exactly zero explanation.

That silence is the story.

The SDN List: How It Actually Works

OFAC manages multiple sanctions programs. The primary one relevant here is the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), which targets malicious cyber activity and human rights abuses by foreign persons.

When OFAC designates someone under CAATSA, they have to articulate a clear violation. The individual either engaged in cyberattacks against US infrastructure, or they enabled human rights abuses by providing tools to do so. Spyware developers and sellers fit squarely in the second category—they knowingly sell surveillance weapons to governments that use them against civilians.

The enforcement mechanism is absolute. Every US bank, payment processor, real estate agency, and investment firm has a legal obligation to check the SDN list before processing any transaction. Finding a match triggers a 24-hour reporting requirement to OFAC and an immediate freeze of assets. Get it wrong, and the institution itself faces penalties.

The fact that three individuals tied to an active, operational spyware platform were removed from this list without public explanation creates a massive credibility problem. It suggests either the original sanctions were based on incorrect information, or something changed diplomatically that made keeping them on the list politically inconvenient.

Neither scenario is reassuring.

Why This Delisting Matters for Cybersecurity Policy

The removal signals something fundamental about how the US government handles commercial spyware as a national security threat. If OFAC initially had enough evidence to sanction these three executives, what changed?

Were they cooperating with US intelligence? Did someone higher up in the administration decide that disrupting Intellexa wasn't worth potential blowback with allied nations that had been using their tools? Did the executives claim they were winding down operations, and the government took them at their word?

None of these questions have been answered, and that opacity is dangerous.

Commercial spyware isn't like a traditional weapons system. Once a vulnerability is weaponized in a surveillance tool, it stays weaponized. The code doesn't go away because a government decided sanctions were inconvenient. Predator's capabilities remain unchanged, and new targets keep getting infected.

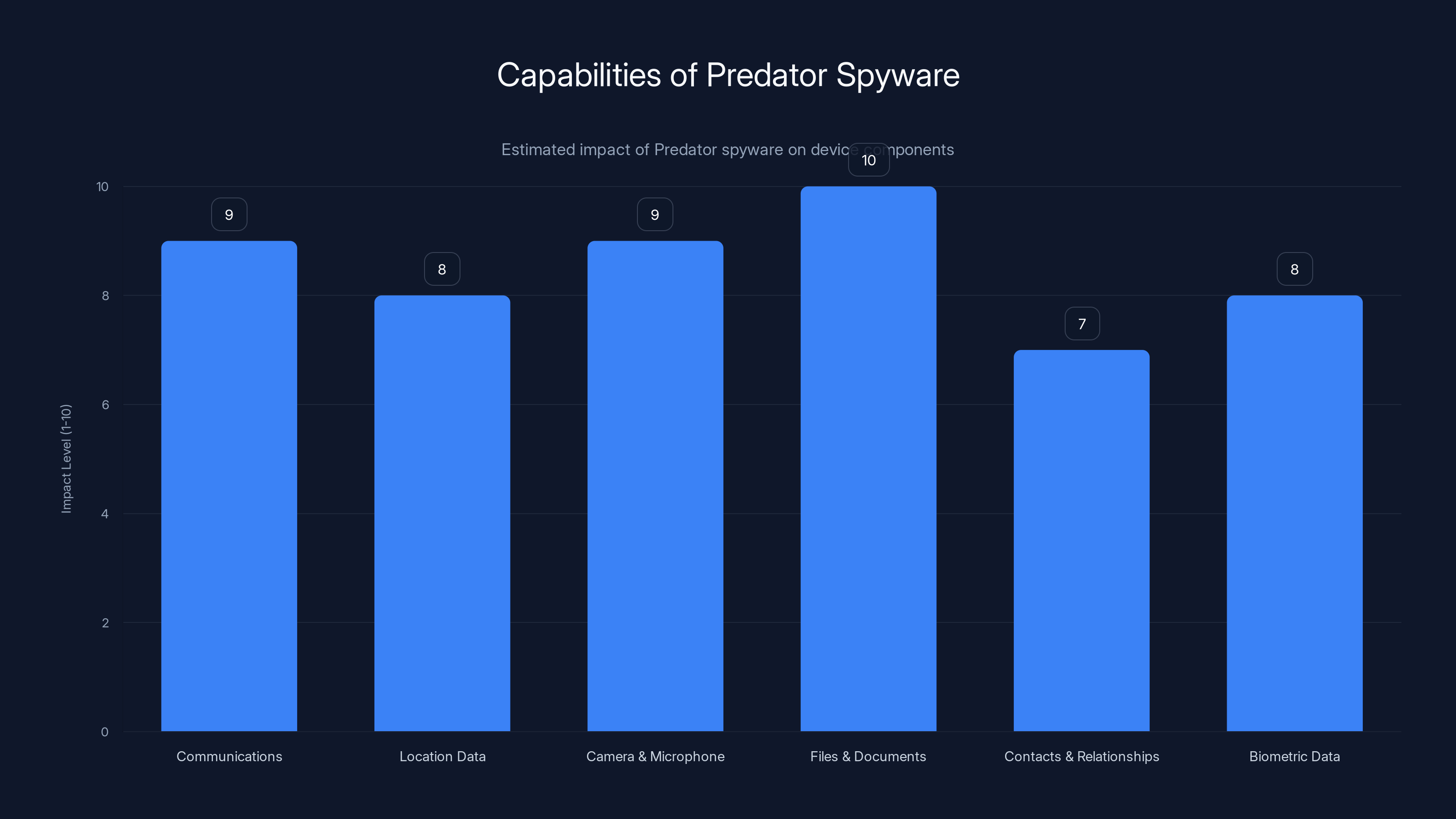

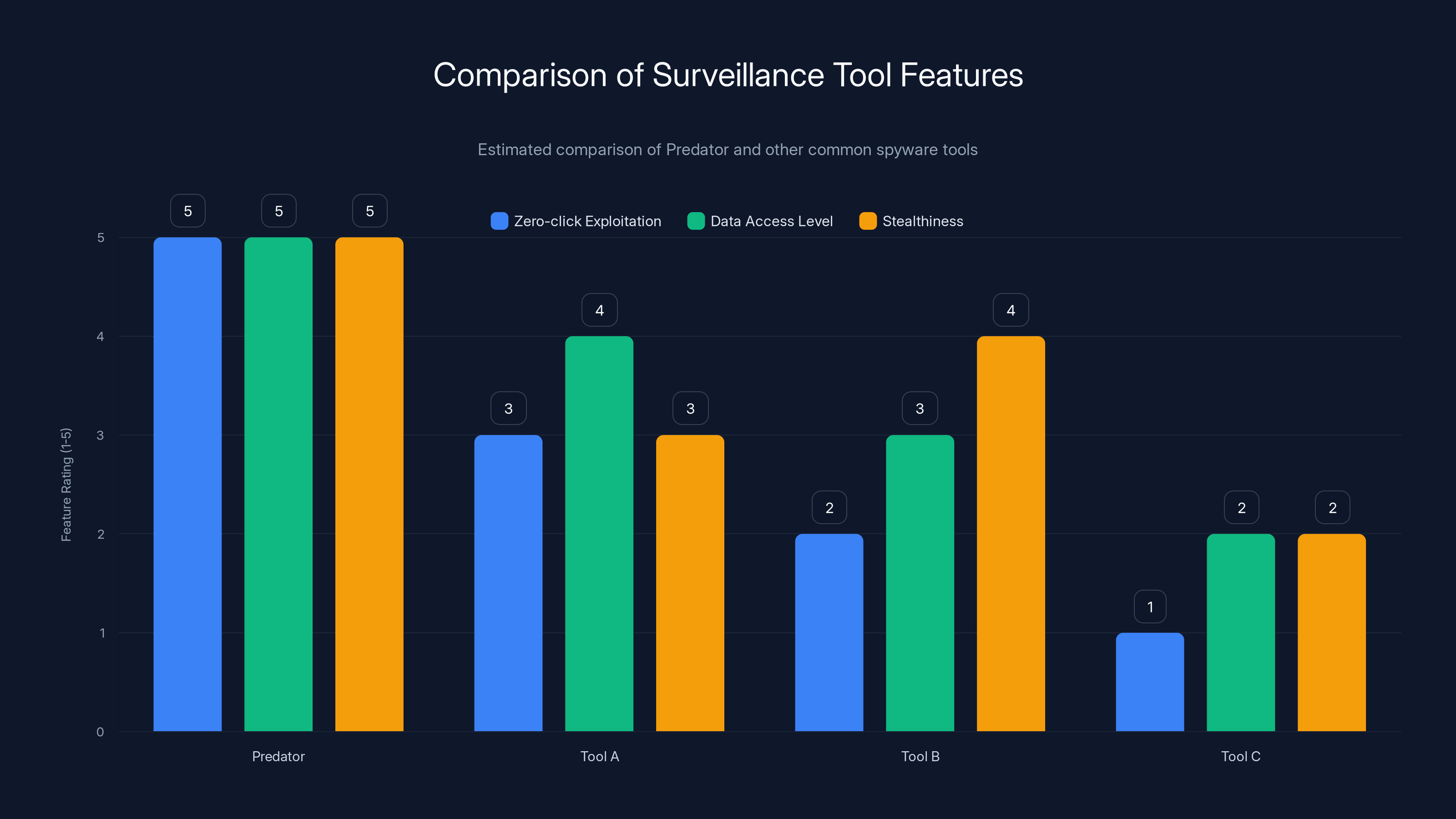

Predator spyware has a high impact across various device components, particularly in accessing files and documents. Estimated data.

The Intellexa Consortium: A Brief History of a Spyware Empire

Intellexa Consortium isn't a single company—it's a network of interlinked entities designed to obscure ownership and make enforcement difficult. Think of it as a holding company structure for surveillance weapons.

The core entities include Intellexa Limited (the operational center), Thalestris Limited (owned by Gambazzi), and a sprawl of subsidiaries registered across multiple jurisdictions. This structure is intentional. When one entity gets investigated or sanctioned, the others theoretically can continue operating. It's the corporate equivalent of a hydra.

Intellexa's main product is Predator spyware. Unlike casual hacking tools, Predator is a sophisticated, remote-access trojan (RAT) designed for zero-click attacks. That means the target doesn't need to click anything, install anything, or do anything differently. Just having their phone near a compromised Wi Fi network, or receiving a message, can be enough for infection.

Once Predator gets into a device, it does what you'd expect from enterprise surveillance software. It records calls, captures messages, extracts files, uses the camera and microphone, steals contacts and location data. It's not crude—it's built to be forensically difficult to detect and nearly impossible to remove without professional help.

Intellexa marketed Predator directly to government agencies, particularly those in authoritarian countries or countries with poor human rights records. The pitch was straightforward: buy this tool, and you can monitor your enemies without them knowing. Scale it across a nation, and you've got mass surveillance capability.

This is where the human rights angle comes in. Predator wasn't sold to democratic governments with robust judicial oversight and warrant requirements. It went to regimes that use such tools against dissidents, political opponents, journalists, and anyone else deemed a threat to state control.

The Known Targets and Scope of Predator Attacks

We don't know the full extent of Predator's deployment because the whole point is secrecy. But leaked documents and investigative reports have identified targets across multiple countries.

Investigative journalists have documented Predator infections in Greece, where it was allegedly used against the political opposition and journalists. There's evidence of Predator use in Poland, where it was reportedly deployed against activists. In the Middle East, there are indications Predator's been used to target political dissidents and journalists.

The most recent incident that we know about happened just weeks ago—a Pakistani human rights lawyer was targeted with Predator via Whats App. That's particularly significant because Pakistan is one of the countries where Intellexa has had documented ties to government agencies.

Think about what this means. The US sanctioned these three executives in March and September 2024. By early 2025, a human rights lawyer in Pakistan was being actively targeted with the exact same spyware tool. The sanctions didn't stop the operations. They didn't disrupt the supply chain. The tool kept working, kept getting used, kept destroying privacy.

Then, a few weeks after that attack, the US removed these executives from the sanctions list.

The timing is... noteworthy.

The Business Model: Selling Surveillance to Governments

Intellexa didn't develop Predator for the open market. There's no "Predator Plus" subscription for corporations. This was a B2B2G model—business to government through a network of subsidiaries and resellers.

The typical process works like this. A potential client (usually a country's intelligence or law enforcement agency) makes an inquiry. Intellexa evaluates whether they think it's worth the reputational risk. If yes, they quote a price—usually millions of dollars for deployment, plus ongoing licensing and support fees. The client signs an end-user agreement that theoretically restricts use to counterterrorism or serious crime investigations.

Then nothing's enforced.

Once Predator's deployed, Intellexa can't control how it's used. They probably don't want to know. The vague end-user agreements create plausible deniability. "We sold this for terrorism prevention. It's not our fault if the government decided to spy on journalists. That's on them."

Except Intellexa knew. Everyone in the industry knows. The entire commercial spyware market runs on the assumption that governments will use these tools for political surveillance. It's the reason the market exists at all.

The Three Executives: Who They Were and What They Did

Let's look at the specific individuals who just got delisted.

Merom Harpaz: The Executive Face

Harpaz was identified as a top executive in the Intellexa Consortium. When the US initially sanctioned Intellexa in March 2024, Harpaz was mentioned as a key player in the organization's leadership structure.

Executives at spyware companies occupy a weird ethical space. They're not field agents or soldiers. They're not directly using the tools against targets. They're running a business—organizing development, managing sales, handling operations. But they know exactly what their product does, who's buying it, and what it's being used for.

Harpaz's role was to keep Intellexa operational. As a top executive, he would have been involved in strategic decisions, client relationships, and possibly financing and expansion. He wasn't a coder who didn't understand the implications. He was a manager making decisions that enabled mass surveillance.

When OFAC sanctioned him in September 2024, the rationale was that his executive position made him responsible for the company's human rights abuses. You don't get to claim ignorance when you're the one directing operations.

Now he's been delisted.

Andrea Nicola Constantino Hermes Gambazzi: The Owner

Gambazzi's title is even more significant. He was identified as the beneficial owner of Thalestris Limited and Intellexa Limited—the parent companies controlling the actual spyware operations.

Beneficial ownership is crucial in sanctions law. OFAC doesn't just go after executives who manage companies. They go after the people who own them, because ownership implies both financial benefit and decision-making authority. If your company is trafficking in surveillance weapons, and you're the one who owns it and profits from it, you're directly accountable for what it does.

Gambazzi's background suggests he's the kind of operator who specializes in making companies like this work. There are entire professions built around owning companies that do questionable things in questionable jurisdictions. You set up shell companies, move ownership through legal structures designed to obscure it, take the profits out as consulting fees or management contracts. On paper, you're just a businessman. In reality, you're the architect of a system designed to hide liability.

Sanctioning the beneficial owner is meant to cut off the money. Stop the profits, and the company stops operating. Without Gambazzi and his ownership stake, Intellexa becomes financially unviable—or so the theory goes.

But again, he's now been delisted. Which means either OFAC believes Intellexa's no longer operating (evidence suggests otherwise), or something else convinced them to reverse course.

Sara Aleksandra Fayssal Hamou: The Corporate Structure Specialist

Hamou was listed as a corporate off-shoring specialist providing managerial services. This is the person who builds and maintains the hidden ownership structures.

She's the reason companies like Intellexa are hard to hold accountable. Shell companies, nominee directors, holding companies registered in jurisdictions with weak disclosure requirements, bank accounts obscured through intermediaries—Hamou's job is to create the legal and corporate maze that makes it nearly impossible to trace who actually owns what and who's responsible for what.

Off-shoring specialists aren't evil geniuses. They're skilled professionals in a legal gray area. What they do is technically legal in most jurisdictions. The whole reason they exist is that there's genuine, legitimate demand for corporate privacy and structure. But that same toolset gets used by surveillance companies to hide who's making money from human rights abuses.

When OFAC sanctioned Hamou in March 2024, they were saying, "We know what you do, and we're cutting off your ability to do it for this company." They were trying to make it harder for Intellexa to hide and reorganize if the main entities got disrupted.

Now she's been delisted too.

Estimated data suggests that the majority of Intellexa's Predator spyware is marketed to authoritarian governments and those with poor human rights records, reflecting its use in mass surveillance.

The Timeline: From Sanctions to Delisting

Let's walk through the actual sequence of events.

March 2024: The First Sanctions Wave

In March 2024, the US government sanctioned Intellexa Consortium as an entity and designated Sara Hamou individually. The announcement cited Intellexa's development and marketing of spyware tools designed for mass surveillance, specifically calling out Predator as the primary product.

The stated justification was that Intellexa knowingly sold surveillance capabilities to governments, and those governments used those capabilities to target journalists, human rights defenders, and political dissidents. By providing the tool, Intellexa made itself complicit in human rights abuses.

This was the standard playbook for commercial spyware enforcement. The US has done similar actions against companies like NSO Group (maker of Pegasus spyware) and Candiru. Sanction the company, designate key individuals, freeze assets, prohibit business transactions.

At the time, the move seemed forceful and meaningful. Here was the US government drawing a clear line: sell surveillance tools to authoritarian governments, and we'll sanction you.

Then, six months later, they started backing off.

September 2024: The Second Sanctions Wave (Expansion)

Six months into the original sanctions, OFAC didn't lift them. Instead, they expanded them.

In September 2024, the US designated two additional individuals: Merom Harpaz and Andrea Gambazzi. The rationale was that these two were even more central to Intellexa's operations than Hamou. Harpaz as a top executive making strategic decisions. Gambazzi as the beneficial owner and financial beneficiary.

This was an escalation, not a retreat. Adding Harpaz and Gambazzi to the list suggested the US government was getting serious. They'd let the initial sanctions sit for a few months, assessed that they weren't working, and decided to cut off the money at the source by going after the owners directly.

Sanctioning beneficial owners is a more aggressive move because it's harder for them to escape. An executive can resign, claim they were just following orders, separate themselves from the company. An owner can't. Their wealth is bound up in the business. Sanctions against them directly threaten their financial interests in a way that forces attention.

For about four months, all three—Harpaz, Gambazzi, and Hamou—remained on the SDN list. If the pattern had held, we'd probably expect more escalation, or a long period where the sanctions remained in place as a pressure point.

Instead, they got delisted.

Early 2025: The Mysterious Removal

There was no announcement. No press release. No official explanation.

OFAC simply removed all three individuals from the SDN list. The delisting appeared in a routine update, the kind of bureaucratic notice that most people never see. No details about why the decision was made. No explanation of what changed. No statement about whether Intellexa had agreed to cease operations, whether they'd cooperated with US intelligence, whether there was a broader deal being cut.

Just gone.

The timing was particularly striking because, just weeks before the delisting, a Pakistani human rights lawyer had been targeted with Predator spyware via Whats App. This wasn't ancient history. This was active, ongoing Predator use against someone doing exactly the kind of work (human rights defense) that supposedly justified the original sanctions.

If Predator was still being actively used to target human rights defenders after the September 2024 sanctions expansion, why were we removing the sanctions in early 2025?

Either the US government had evidence that Intellexa had stopped operations (unlikely, given the fresh Predator attack), or something else was driving the decision.

Predator Spyware: Technical Capabilities and Attack Methods

To understand why these sanctions mattered, you need to understand what Predator actually does and how dangerous it is.

Predator is a remote access trojan built on a foundation of zero-click exploitation. In the spyware world, "zero-click" is the holy grail of attack methods. It means the target doesn't need to do anything wrong. They don't need to click a link, open an attachment, install an app, or acknowledge anything. The infection happens silently, without their knowledge or interaction.

The standard Predator attack chain works like this. A target is identified. Intellexa or their government clients work with telecom operators or network administrators to intercept the target's communications. The attack happens during a message delivery—possibly a Whats App message, an SMS, a Telegram message, or a push notification. The exploit code triggers silently, giving Predator a foothold on the device.

Once Predator's installed, it operates like a legitimate system process. It integrates deeply into the operating system, giving it access to virtually everything on the device. Here's what an infected person loses, usually without ever knowing it:

- Communications: All messages, emails, and calls. Predator records them in real-time and exfiltrates them to a command-and-control server.

- Location data: Predator knows where you are at all times, accurate to a few meters.

- Camera and microphone: Predator can activate them without the LED indicator that normally appears when these are in use, giving attackers real-time surveillance capability.

- Files and documents: Everything on the device, including photos, documents, password managers, and encrypted files.

- Contacts and relationships: Predator can identify who you know and how you interact with them.

- Biometric data: Fingerprints, face recognition data, voice recordings.

Predator is designed to be stealthy. It doesn't drain the battery quickly. It doesn't generate unusual network traffic that security software would flag. It doesn't create obvious artifacts on the device. The idea is that someone can be infected for weeks or months without having any idea their privacy has been completely compromised.

Detection and Defense Challenges

Defending against Predator is extraordinarily difficult for ordinary users, and even challenging for security professionals.

The zero-click attack method means the standard user awareness advice—"don't click suspicious links"—is useless. You can't click your way to safety if there's nothing to click. The infection happens at a system level, below the user interface.

Antivirus and mobile security software struggle because Predator often uses zero-day exploits (vulnerabilities that haven't been publicly disclosed yet). These aren't bugs that security companies know about and have patched. They're previously unknown flaws that Intellexa or their government clients found and weaponized.

Even if you wanted to check whether you've been infected, you probably can't. Predator is designed to hide its presence. Professional threat hunters with access to forensic tools can sometimes find evidence after the fact, but your typical antivirus software won't detect it.

The only reliable defense is prevention. Don't communicate with anyone who might be targeted with Predator. Or use a feature phone with basic SMS capability instead of a smartphone. Neither is practical for people who need to stay connected to organize, communicate, and report on human rights abuses.

This is why Predator is such a powerful tool for authoritarian governments. It's not about catching criminals or preventing terrorism (both of which require warrant-backed surveillance of suspect individuals). Predator enables mass surveillance of an entire population of potential dissidents. Scale it up, and a government can monitor thousands of people at once, identifying networks of resistance or dissent before they become threats.

Comparison to Other Commercial Spyware

Predator isn't the only commercial spyware in existence. NSO Group's Pegasus spyware is probably more famous, having been revealed in the Pegasus Project leaks. There's also Candiru's Fim spyware, Moon spyware, and a handful of others.

The capabilities are similar across these tools, but Predator's zero-click approach is particularly insidious. Pegasus also has zero-click capabilities, but Pegasus was publicly exposed in detailed, journalistic investigations. Governments using Pegasus knew they had to be more cautious about targets because the tool was famous and people understood what it could do.

Predator, by contrast, was less well-known outside cybersecurity circles. The general public didn't know what Predator was. Human rights defenders didn't know what they were up against. That obscurity was an advantage for Intellexa and their clients. A surveillance tool is most effective when people don't know it exists.

Predator spyware is estimated to have superior zero-click exploitation and data access capabilities compared to other common surveillance tools, making it particularly dangerous. Estimated data.

The Sanctions Response: What Worked and What Didn't

When the US first sanctioned Intellexa in March 2024, what was the point?

OFAC's theory of change with sanctions is that financial pressure forces behavioral change. If you can't access the US financial system, if your assets get frozen, if nobody wants to do business with you because they're afraid of secondary sanctions—eventually, you have to choose between your business and changing your behavior.

For traditional sanctions targets—countries, major companies, wealthy oligarchs—this sometimes works. Russia's economy has been significantly damaged by sanctions following the Ukraine invasion. Iranian banks and oil companies have been crippled. Individual oligarchs have lost access to yachts and real estate.

For a spyware company, the calculus is different.

Why Sanctions Might Not Work Against Spyware Companies

First, spyware companies are inherently international and decentralized. Intellexa's main operations were probably in Europe (given the individuals' names and the company registrations), but they had reach into multiple countries. Sanctioning them in the US doesn't prevent them from operating elsewhere.

Second, their primary customers are governments, not US companies or consumers. If the US bans all American companies from working with Intellexa, that's a problem for Intellexa's revenue from American government contracts. But if Intellexa never had significant American government contracts (and there's no public evidence they did), the US sanctions don't hurt their core business.

Third, the profit margins on spyware are enormous. A single deployment can be worth millions. You need far fewer clients to be profitable than a software company that sells to the mass market. If you go from selling to 20 governments to selling to 15 governments because some pulled away due to international pressure, you're still profitable.

Fourth, and most importantly, the political will to enforce sanctions against a spyware company is weak compared to, say, sanctioning a Russian oligarch. A Russian oligarch has no defenders in Western governments. Sanctioning them is easy and popular.

Intellexa's clients, however, probably include governments that the US has diplomatic relationships with. They might be partners on other issues. They might be buying American weapons. They might host US military bases. Sanctioning their surveillance tool creates friction in those relationships.

Evidence That Sanctions Weren't Working

The most obvious evidence is that Predator didn't stop being used.

By November or December 2024, just a few months after the September sanctions expansion, reports emerged that a Pakistani human rights lawyer was actively being targeted with Predator via Whats App. This wasn't a remnant attack from before the sanctions. This was fresh, ongoing targeting.

If the sanctions had disrupted Intellexa's operations, we wouldn't expect to see new Predator attacks. We'd expect to see the tool going dormant as the company scrambled to survive under sanctions.

Instead, it was business as usual.

This strongly suggests that either:

- The sanctions never actually disrupted Intellexa's operations, or

- Intellexa found ways to circumvent them, or

- Their government customers continued using Predator regardless of sanctions, relying on servers and infrastructure outside US jurisdiction.

Probably all three.

The Political Reality of Sanction Enforcement

This is where the delisting decision makes more sense, even if it's not more ethical.

If you're a US government official and you've sanctioned a spyware company, but the sanctions haven't disrupted their operations, and their government customers are complaining about the sanctions affecting their relationship with the US, what do you do?

You could increase the pressure. Add more sanctions, broaden the restrictions, go after their suppliers. But that escalates the diplomatic cost further.

Or you could quietly lift the sanctions on specific individuals, claim victory ("We've disrupted Intellexa's leadership"), and let the issue fade.

From a purely realpolitik perspective, that second option makes sense if you've already decided that the sanctions weren't effective enough to justify the diplomatic friction they were causing.

The delisting might not have anything to do with Intellexa actually changing their behavior. It might be pure political calculation: the sanctions weren't working, so there's no point keeping them, and lifting them restores some goodwill with allied governments that were frustrated by the original designations.

Government Surveillance Tools and Policy Implications

This situation reveals something uncomfortable about how governments actually handle the commercial spyware problem.

On one hand, there's public-facing rhetoric. The US condemns surveillance tools that target human rights defenders. The Biden administration has made human rights a centerpiece of its foreign policy message. Congress has expressed concern about commercial spyware.

On the other hand, there's the actual behavior. Governments buy these tools themselves. They encourage allies to buy them. They use them against their own dissidents. When forced to choose between maintaining a principled stance against spyware and maintaining diplomatic relationships, the diplomatic relationships tend to win.

The Hypocrisy Problem

The US government uses surveillance tools against terrorism suspects, drug traffickers, and hostile foreign intelligence agencies. Some of that is legitimate law enforcement. Some of it is overreach.

The difference between US surveillance and the surveillance that Intellexa enables is theoretically about rule of law and oversight. US surveillance of terrorism suspects happens under warrant. It's subject to Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) procedures. There's theoretical oversight from Congress and the judiciary.

Surveillance by authoritarian governments using Intellexa's Predator spyware has no such constraints. There's no warrant. There's no independent judicial approval. There's just the government deciding that person X is a threat and monitoring them.

But that theoretical distinction doesn't actually mean much when you're the person being surveilled. Being wiretapped under a FISA warrant still violates your privacy. The fact that a judge approved it doesn't make the invasive surveillance less invasive from your perspective.

And if the US wants to credibly claim the moral high ground on this issue, it probably needs to actually enforce its stated principles, not quietly remove sanctions when it becomes diplomatically inconvenient.

The Regulatory Gap

One broader implication of the Intellexa situation is that our current regulatory framework for spyware is fundamentally inadequate.

Sanctions are a foreign policy tool, not a regulatory mechanism. They're blunt instruments designed to punish and deter. They're not designed to address a systemic problem. Intellexa is one company among many. Predator is one spyware tool among many. Removing Intellexa wouldn't eliminate the commercial spyware problem even if the sanctions had worked perfectly.

What we'd actually need is export control on surveillance capabilities. Countries like Germany, Israel, and the US control who can export military weapons. But surveillance tools are treated differently—they're not officially weapons, they're "law enforcement" tools. That classification makes them easier to export and harder to regulate.

Some of this is changing. The European Union has moved toward stricter controls on surveillance tools. Some countries have banned the sale of spyware entirely. But this is patchy and inconsistent.

Until there's a coherent, global regulatory framework that treats commercial spyware like what it actually is—a dual-use military technology that can be weaponized against civilian populations—we'll keep seeing situations like this where governments sanction companies for optics, then quietly remove the sanctions when they become diplomatically uncomfortable.

Estimated data showing the distribution of entities on the OFAC SDN list, highlighting the focus on terrorism financing and drug trafficking.

The Broader Commercial Spyware Ecosystem

Intellexa isn't operating in a vacuum. There's an entire industry of companies developing and selling surveillance tools to governments.

Other Major Players

NSO Group, an Israeli company, develops Pegasus spyware. Pegasus is arguably even more sophisticated than Predator, with capabilities that match or exceed Predator's. NSO has faced international scrutiny, press coverage, and some sanctions, but the company continues operating.

Candicore, another Israeli company, makes surveillance tools. There's Positive Technologies in Russia, which develops remote access capability. Moon spyware, reportedly developed by a Moroccan company. And dozens of smaller players offering localized surveillance solutions.

The industry exists because demand exists. Governments want to spy on their populations. Companies that provide the tools are profitable. Markets work, even when the product is privacy violation.

The Funding and Investment Side

Spyware companies are usually venture-backed or government-funded. NSO Group has received investment from prominent venture capital firms and private equity groups, some of which are based in the US or operate through US investment structures.

That creates an interesting contradiction. US investors sometimes fund companies whose products the US then sanctions. Or US companies do business with governments that buy spyware from Israeli companies, even while the US condemns spyware.

There's no strong regulatory mechanism preventing this. There's no requirement that venture capital firms vet the human rights implications of surveillance tools they're funding. There's no export control that prevents US capital from flowing into spyware companies.

So even when the US sanctions a specific spyware company like Intellexa, the broader ecosystem that funds and supports spyware development continues operating unchanged.

What the Delisting Means for Human Rights Defenders

For the people actually being targeted with surveillance tools, the delisting means something concrete: the political pressure against spyware development just got weaker.

A human rights lawyer in Pakistan, or a journalist in Greece, or an activist in the Middle East can't appeal to US sanctions if the people running the spyware network aren't on the SDN list anymore. The threat model doesn't change materially—they were still at risk of Predator attacks before the delisting, and they're still at risk after. But the symbolic message from the US government is now muddier.

"We're concerned about commercial spyware," the US says. But "We're not concerned enough to keep the sanctions in place," it also says simultaneously. These messages point in different directions.

For human rights defenders who've been counting on the US government as a counterweight to authoritarian surveillance, that's demoralizing. It suggests that when diplomatic interests conflict with principle, principle loses.

Practical Security Implications

From a practical security standpoint, the delisting probably doesn't affect the immediate threat level. Predator was still being developed and deployed before the delisting. It will continue to be developed and deployed after.

What might change is investment and expansion. If Intellexa was worried about sanctions crushing the company, they might have been more cautious about taking on new customers or expanding their product line. With sanctions lifted, that constraint goes away. They might become more aggressive about finding new markets and customers.

For people working in human rights, the implicit message is to assume they could be targeted at any time. Not because of anything they've done wrong, but because governments want to know what they're doing and how they're organizing. The only defense is security tools and tradecraft that assume professional-grade surveillance is happening.

The sanctions against Intellexa intensified from March to September 2024, with a significant escalation in September when additional individuals were sanctioned. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Intelligence Community Perspective

There's one scenario where the delisting makes sense from the US government's perspective: Intellexa became an intelligence asset.

If, at some point over the past six months, Intellexa or its executives agreed to cooperate with US intelligence—perhaps providing access to the networks they'd already compromised, or sharing information about who was using Predator and how—the US might have decided that the intelligence value of the cooperation exceeded the value of the sanctions.

This happens sometimes. The US has cooperative relationships with intelligence services in countries that do all kinds of problematic things. If Intellexa offered something valuable—intelligence access, information about spyware targets, visibility into which governments are conducting surveillance—that might be worth more than maintaining the sanctions.

But this is speculative. There's no public evidence of cooperation, and the US government certainly wouldn't announce it if it existed.

The point is that from the US intelligence community's perspective, a sanctions regime might be the wrong tool for managing the spyware problem. What they might actually want is relationship-building, information sharing, and access. Sanctions cut off those possibilities.

So if an intelligence official decided that cooperating with Intellexa (or just lifting the sanctions to avoid diplomatic friction with countries using their products) was in the national security interest, they'd have leverage to argue for the delisting.

Why Transparency Matters: The Open Questions

The fact that the delisting came with zero explanation is the biggest problem in this entire situation.

OFAC routinely explains the rationale for designations. When they put someone on the SDN list, they publish detailed documents articulating the legal basis, the evidence, and the violations. This transparency is supposed to be a feature—it's supposed to show that sanctions are based on law and evidence, not political whim.

When they remove someone from the list, the same transparency ought to apply. If the original evidence was flawed, explain what was wrong. If new evidence emerged showing the person changed their behavior, explain what they did. If they cooperated with the US, explain the general nature of that cooperation (even if you can't publish classified details).

Instead, we got nothing. Just a quiet removal.

That's a problem because it opens the door to speculation. Was this a mistake? Was this a political deal? Was someone pressuring the administration? Was someone in the intelligence community deciding the sanctions were counterproductive?

Without transparency, we don't know.

The Precedent This Sets

If the US government can designate executives for sanctions, let those sanctions sit for six months, and then silently remove them without explanation, what does that mean for the credibility of the sanctions regime?

It suggests that OFAC designations might not be about principled law enforcement. They might be negotiating tools. You get designated as a negotiating tactic, and maybe you get removed once the negotiation concludes or becomes inconvenient.

That's not necessarily how it works—many designations stick for years. But it creates uncertainty. Business partners won't trust a relationship with someone who's at risk of getting designated. Governments will factor in the risk of sanctions when deciding whether to work with a company.

But if they know designations can be reversed without explanation, the deterrent effect weakens. "Sure, we might get sanctioned, but maybe it'll be quietly reversed in six months if it becomes politically inconvenient for the US."

What Should Happen Next

From a policy perspective, several things should happen.

Demand Transparency

First, Congress should demand an explanation for the delisting. If there was a legitimate reason—evidence that the sanctions were based on flawed information, or evidence that the designated individuals changed their behavior—that should be explained publicly.

If there wasn't a legitimate reason, then the delisting was a mistake and should be reversed.

Strengthen Surveillance Tool Regulations

Second, there needs to be stronger regulatory control over surveillance tool exports. The current system of sanctions, where they're applied after the fact as a punitive measure, doesn't work. Export controls, similar to military weapons controls, would be more effective.

This would require international cooperation, but it's achievable. The EU is moving in this direction. The US could propose stronger international standards.

Support Independent Monitoring

Third, organizations like the European Union and civil rights groups should continue monitoring spyware development and deployment. The Pegasus Project was revelatory not because the governments using it were hiding it, but because independent journalists and researchers were tracking it. That work needs to continue.

Hold Companies Accountable

Fourth, there need to be consequences for spyware company executives who knowingly enable surveillance against human rights defenders. Sanctions are one tool, but criminal liability might be another. If executives of surveillance companies could face actual criminal charges for aiding human rights abuses, that would be a more serious deterrent than financial sanctions.

FAQ

What is Intellexa Consortium and why does it matter?

Intellexa Consortium is a network of companies that develop and market Predator spyware—a surveillance tool capable of remotely accessing smartphones without user interaction. It matters because Predator has been documented targeting journalists, human rights defenders, and political dissidents in multiple countries, making Intellexa a major player in enabling state surveillance against civilian populations.

How does the OFAC sanctions process work?

When OFAC places someone on its Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list, any US-based assets are frozen, and US persons and companies are prohibited from doing business with them. Violations can result in civil penalties up to $250,000 per violation or criminal charges. The process requires documented evidence of violations, which is usually published when designations are made.

What makes Predator spyware different from other surveillance tools?

Predator uses zero-click exploitation, meaning targets don't need to click anything or take any action to become infected. Once installed, it provides complete access to device data including messages, location, camera, microphone, and files. This makes it nearly impossible for ordinary users to protect themselves, which is why it's particularly dangerous when deployed against human rights defenders.

Why would the US government remove executives from the sanctions list without explanation?

Possible reasons include: the original sanctions were based on flawed intelligence and new evidence emerged contradicting the designations; the executives agreed to cooperate with US intelligence; diplomatic pressure from allied governments made the sanctions politically inconvenient; or the US government determined the sanctions weren't effective at stopping Predator deployment and decided the diplomatic cost wasn't worth the benefit. Without an official explanation, these are educated guesses.

Does removing these three executives from the SDN list mean Intellexa is no longer a threat?

No. Predator spyware remains operational, and recent reports show it's still being actively used to target human rights defenders. Removing executives from the sanctions list doesn't change the tool's capabilities or the threat it poses to vulnerable populations. It only changes the international legal status of those specific individuals.

What can human rights defenders do to protect themselves from Predator spyware?

Protection against zero-click spyware is extremely difficult for ordinary users. Recommended practices include using secure messaging apps that have strong end-to-end encryption, keeping devices updated with security patches, using dedicated security devices for sensitive communications, and implementing operational security practices that assume professional surveillance is possible. For high-risk individuals, working with professional security consultants is advisable.

Has this delisting affected other sanctions against spyware companies?

The delisting hasn't formally affected other spyware company sanctions, but it does signal that the US government may not maintain sanctions long-term if they become diplomatically inconvenient. This creates uncertainty about the credibility of future spyware-related sanctions and may embolden spyware developers who believe sanctions will eventually be reversed if they wait long enough.

What should the US government do to better regulate commercial spyware?

Policy experts recommend implementing export controls on surveillance tools similar to military weapons controls, establishing stricter international standards for spyware sales, supporting civil society monitoring of surveillance tool deployment, and pursuing criminal liability for spyware company executives who knowingly facilitate human rights abuses. The current system of after-the-fact sanctions appears insufficient to deter development and sale of surveillance tools.

Conclusion: When Principles Meet Politics

The delisting of Merom Harpaz, Andrea Gambazzi, and Sara Hamou illustrates a fundamental tension in how governments handle technology policy.

On principle, the US government opposes commercial spyware and the human rights abuses it enables. The original sanctions on Intellexa Consortium reflected that principle. They said: "We're taking this seriously enough to freeze assets and prohibit business transactions."

But principles are expensive. They create friction with countries that want to buy surveillance tools. They limit intelligence access. They complicate diplomatic relationships. So when the sanctions didn't seem to be working—when Predator kept operating and getting used—the political cost of maintaining them exceeded the political benefit.

The delisting is a retreat from principle. It's the moment when the administration decided that diplomatic convenience mattered more than the human rights rhetoric.

That's not necessarily a unique problem. Governments routinely make these kinds of compromises. The US conducts business with countries that have appalling human rights records. It funds intelligence agencies in allied nations that operate with minimal oversight. It uses the same surveillance tools against its own citizens that it condemns when other governments use them.

But this particular delisting is worth paying attention to because it's so brazen in its lack of transparency. If the US government had explained the decision—if it had said, "New intelligence shows these individuals have agreed to cease spyware development," or "Diplomatic negotiations resulted in Intellexa scaling back operations," there would at least be a narrative.

Instead, there's just silence. And silence, in a matter involving human rights and national security, raises more questions than it answers.

For the human rights lawyer in Pakistan, the journalists in Greece, the activists in the Middle East, and anyone else who might be targeted with Predator spyware, the delisting sends a message: don't count on the US government to protect you from commercial surveillance. Count on yourself, your security practices, and the hope that someone else finds the evidence necessary to reignite pressure on spyware companies.

It's not the message the US government should be sending. And the fact that it's sending it silently, without explanation, makes it even worse.

The hope is that transparency advocates, Congress members, and civil society organizations keep asking questions about why this delisting happened and what it means for future sanctions against surveillance companies. Sunshine, as they say, is the best disinfectant. And right now, this situation could use a lot more light.

Key Takeaways

- Three Intellexa Consortium executives were quietly removed from OFAC sanctions list with no official explanation, contradicting stated US policy on commercial spyware

- Predator spyware remains operationally active, with recent documented attacks on human rights defenders showing sanctions ineffectiveness

- The delisting signals that diplomatic convenience may outweigh principle in US government surveillance tool enforcement policy

- Commercial spyware regulation requires international export controls, not just after-the-fact sanctions that can be reversed without transparency

- Human rights defenders face an asymmetric threat from tools like Predator that use zero-click exploits—protection requires professional-grade security practices

![US Removes Spyware Executives From Sanctions: What Actually Happened [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/us-removes-spyware-executives-from-sanctions-what-actually-h/image-1-1767199188299.jpg)