US Withdrawal From 66 International Organizations: The Collapse of Global Cooperation [2025]

In early 2025, the Trump administration made headlines by signing an executive order that fundamentally altered America's relationship with the international community. The order declared that the United States would withdraw from 66 international organizations and bodies, marking one of the most dramatic shifts in US foreign policy in recent decades. This isn't just another political news cycle item—it represents a seismic realignment of how the world's largest economy participates (or doesn't) in global governance structures.

What makes this particularly significant is the breadth of organizations on the chopping block. We're not talking about obscure think tanks or minor regulatory bodies. The list includes heavyweight institutions like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the International Trade Centre, and organizations focused on conservation, reproductive rights, and migration. Each one of these represents decades of negotiated agreements, billions in American taxpayer investments, and decades of soft power influence.

The stated justification from the White House? These organizations "promote radical climate policies, global governance and ideological programs that conflict with US sovereignty and economic strength" as reported by Reuters. In other words, they constrain American freedom of action on the international stage. Whether you see that as principled sovereignty or dangerous isolationism largely depends on your political perspective. But the practical implications are enormous and worth understanding in detail.

This article breaks down exactly which organizations are affected, why the Trump administration targeted them, what the actual consequences might be for American interests, and how other nations are likely to respond. Because here's the thing: withdrawal doesn't just hurt the organizations themselves. It reshapes America's seat at the table on everything from trade to climate to global health.

TL; DR

- 66 Organizations Lost: The Trump administration withdrew from dozens of international bodies, including the IPCC and UNFCCC, marking a dramatic shift in US global engagement as noted by AP News.

- Sovereignty vs. Cooperation: The White House frames withdrawals as protecting American sovereignty and economic interests from international constraints according to CNN.

- Climate Action Impacted: Loss of US participation in climate organizations reduces funding and undermines decades of negotiated climate commitments as reported by Earth.org.

- Unknown Long-Term Cost: While the administration claims savings, the actual financial impact and geopolitical consequences remain unclear and potentially substantial as discussed by Politico.

- Trade and Diplomacy: Broader pattern of US disengagement from multilateral agreements extends beyond climate to trade, migration, and conservation as analyzed by The Fulcrum.

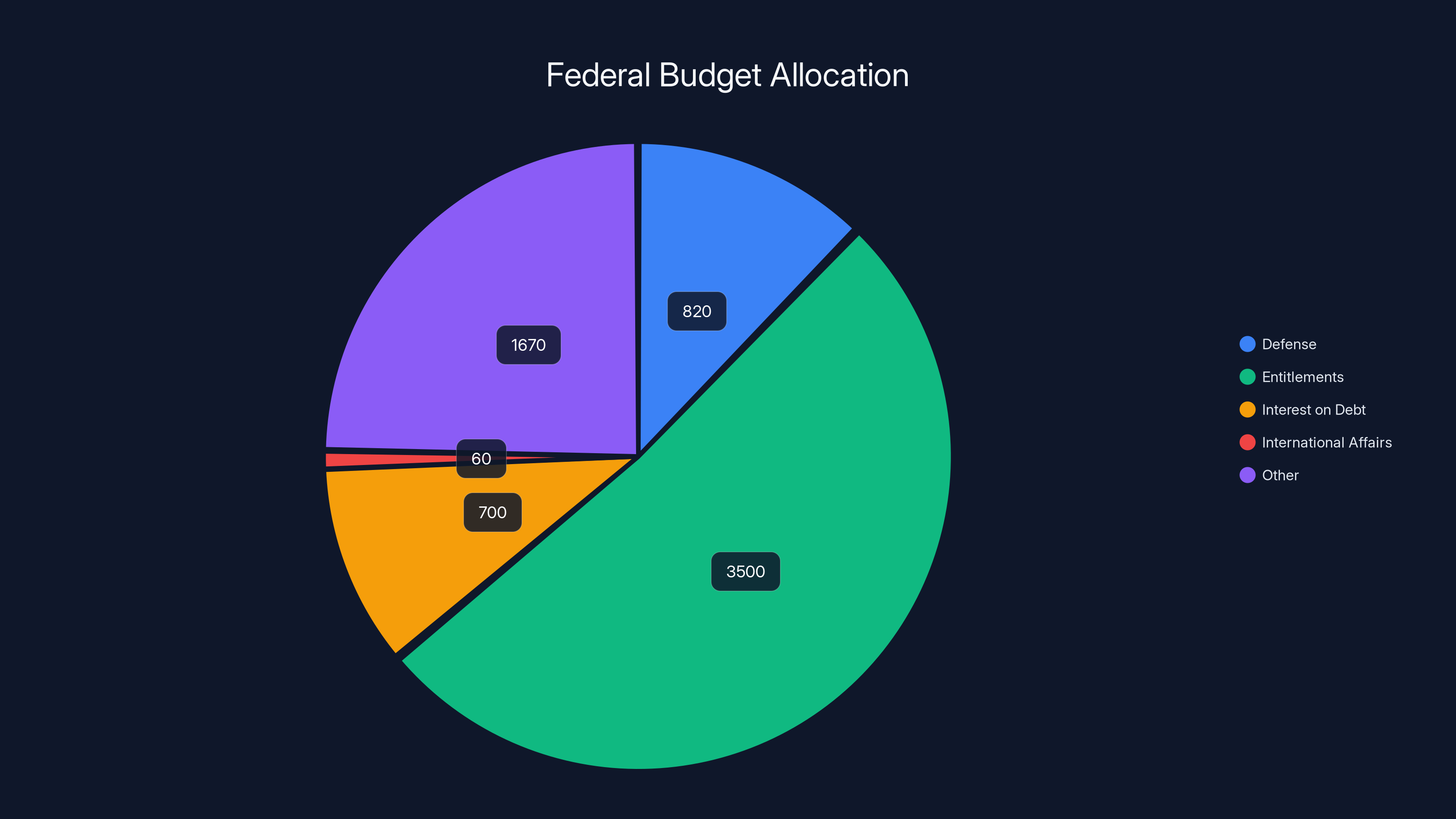

Estimated data shows US contributions to international organizations are about 0.005% of the federal budget, highlighting the symbolic nature of the withdrawals.

The Scale of Withdrawal: 66 Organizations and Counting

Let's start with the raw numbers, because they're staggering. Sixty-six international organizations. That's not a policy tweak or a strategic reassessment. That's a wholesale retreat from the international institutional architecture that America helped build after World War II.

The White House released a fact sheet detailing these withdrawals, but notably—and this is telling—they didn't provide a comprehensive breakdown of exactly which organizations were targeted or what the financial implications would be. That lack of transparency immediately raised questions among policy analysts and international relations experts who wanted to understand the true scope of the move.

Among the most significant targets are the climate-focused organizations. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is the parent treaty governing all international climate negotiations. Think of it as the legal and diplomatic framework that led to the Paris Agreement. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is different—it's a science body that synthesizes climate research and publishes reports that inform policy. By withdrawing from both, the US is essentially saying it won't participate in the ongoing global conversation about climate policy or even acknowledge the scientific consensus on climate change as noted by NPR.

Beyond climate, the list includes:

- International Trade Centre: A UN/WTO body that provides trade development support

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature: The world's largest conservation network with thousands of member organizations

- UN Population Fund: Provides reproductive health services in developing countries

- Global Forum on Migration and Development: Facilitates dialogue on migration policy

Each withdrawal removes American funding, American technical expertise, and American diplomatic leverage. What's particularly interesting is that many of these organizations were described by UN officials as "deliberative bodies" where the US was only marginally involved. Translation: we probably won't save as much money as we think, but we'll lose influence over global direction-setting on these issues as reported by BBC.

Why Climate Organizations?

The targeting of climate-focused organizations is the most ideologically charged part of this withdrawal. Trump has been skeptical of climate change claims for years, infamously calling climate change a "hoax." Withdrawing from the UNFCCC for the second time (he first did it in 2017, Biden rejoined in 2021) sends a clear signal: the US government, at least under this administration, does not acknowledge climate change as a priority requiring international cooperation as discussed by The Japan Times.

Here's the political calculus: Trump's base tends to view climate regulation as economically burdensome, particularly for energy and manufacturing sectors. International climate organizations are seen as pushing policies that would constrain American economic growth. From this perspective, withdrawal is protective—it prevents unelected international bodies from influencing US energy policy.

From another perspective, it's deeply shortsighted. The US still participates in the International Energy Agency, which focuses on clean energy solutions, but withdrawing from the IPCC means we won't participate in shaping climate science consensus. We're essentially punching ourselves in the face—we lose the ability to influence how climate science is interpreted and what recommendations get made as noted by Tax Notes.

The Funding Question

One critical detail the White House glossed over: how much money does the US actually contribute to these organizations, and where does it go?

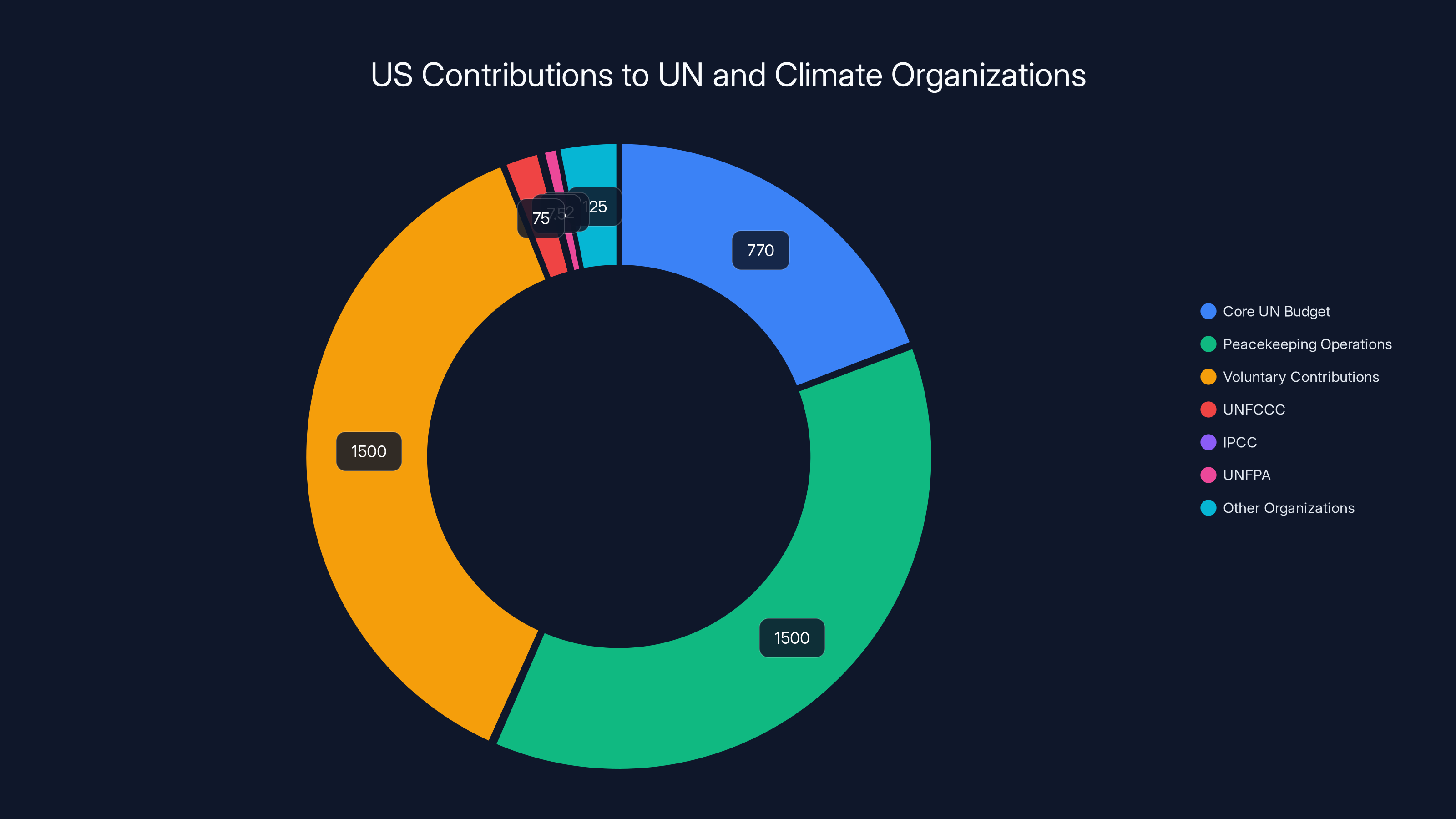

The UN budget operates differently than most people assume. Each organization has its own funding mechanism. Some rely on assessed contributions (mandatory payments from member states), while others depend on voluntary contributions. The US, as a major power, typically contributes significantly to assessed budgets but also makes substantial voluntary contributions to specific programs.

For perspective, the US typically contributes about 22% of the UN's core budget. That's roughly

What's more important than the raw dollar amount is what that money was purchasing: American influence, soft power, and the ability to shape international norms and policies in America's favor. By withdrawing, the US trades short-term budget savings for long-term diplomatic influence.

The Politics Behind the Withdrawal

Understanding why the Trump administration made this move requires understanding its broader ideological commitments. This isn't random or isolated. It's part of a consistent pattern of hostility toward multilateral institutions and international cooperation.

America First Philosophy

The "America First" doctrine prioritizes unilateral American action over consensus-based international cooperation. From this perspective, multilateral institutions are constraining—they require the US to compromise, negotiate, and sometimes accept outcomes that don't perfectly serve American interests.

Consider trade policy as an example. The US withdrew from trade talks with Canada in mid-2025 over digital services taxes. Just months later, the administration banned EU commissioner Thierry Breton from entering the US for his role in creating the Digital Services Act. These aren't random diplomatic incidents. They're intentional signals that the US will act unilaterally and will punish other countries for adopting regulations the US dislikes as noted by NPR.

The climate withdrawals fit neatly into this pattern. International climate agreements—the Paris Agreement, the Montreal Protocol, etc.—constrain what individual countries can do. They require nations to adopt policies to reduce emissions. From an "America First" perspective, that's an unacceptable constraint on national sovereignty.

The Sovereignty Argument

The White House's official justification centers on sovereignty. The statement about organizations promoting "ideological programs that conflict with US sovereignty and economic strength" reflects a genuine ideological position: international bodies should not be able to influence American policy as reported by CNN.

This argument has some validity in a narrow sense. Sovereignty does matter. No country should accept policies it disagrees with simply because they're popular in international forums. But the argument becomes complicated when you consider that the US is not a passive participant in these organizations. America helped establish many of them, shapes their direction, and has significant power within them.

Withdrawing because other countries disagree with you isn't protecting sovereignty. It's choosing to cede influence. It's like quitting a board you partly control because you don't like the direction the board is moving. Once you leave, you can't shape it anymore.

The Conservative Regulatory Skepticism

Understanding conservative hostility toward these institutions also requires understanding a deeper ideological commitment to regulatory skepticism. Many conservatives view international regulations—whether on climate, labor, or the environment—as obstacles to economic growth.

This isn't entirely irrational. Regulations do impose costs. The question is whether those costs are justified by benefits. But the way climate science is discussed in conservative circles often treats the scientific consensus itself as ideologically motivated rather than empirically grounded as discussed by Politico.

When the White House describes the IPCC as promoting "radical climate policies," it's not engaging with the IPCC's actual methodology or findings. The IPCC synthesizes peer-reviewed scientific literature. Its conclusions reflect what the evidence actually shows. Calling that "radical" is rhetorical rather than analytical. But politically, it resonates with an audience that views climate change as exaggerated or a pretext for government overreach.

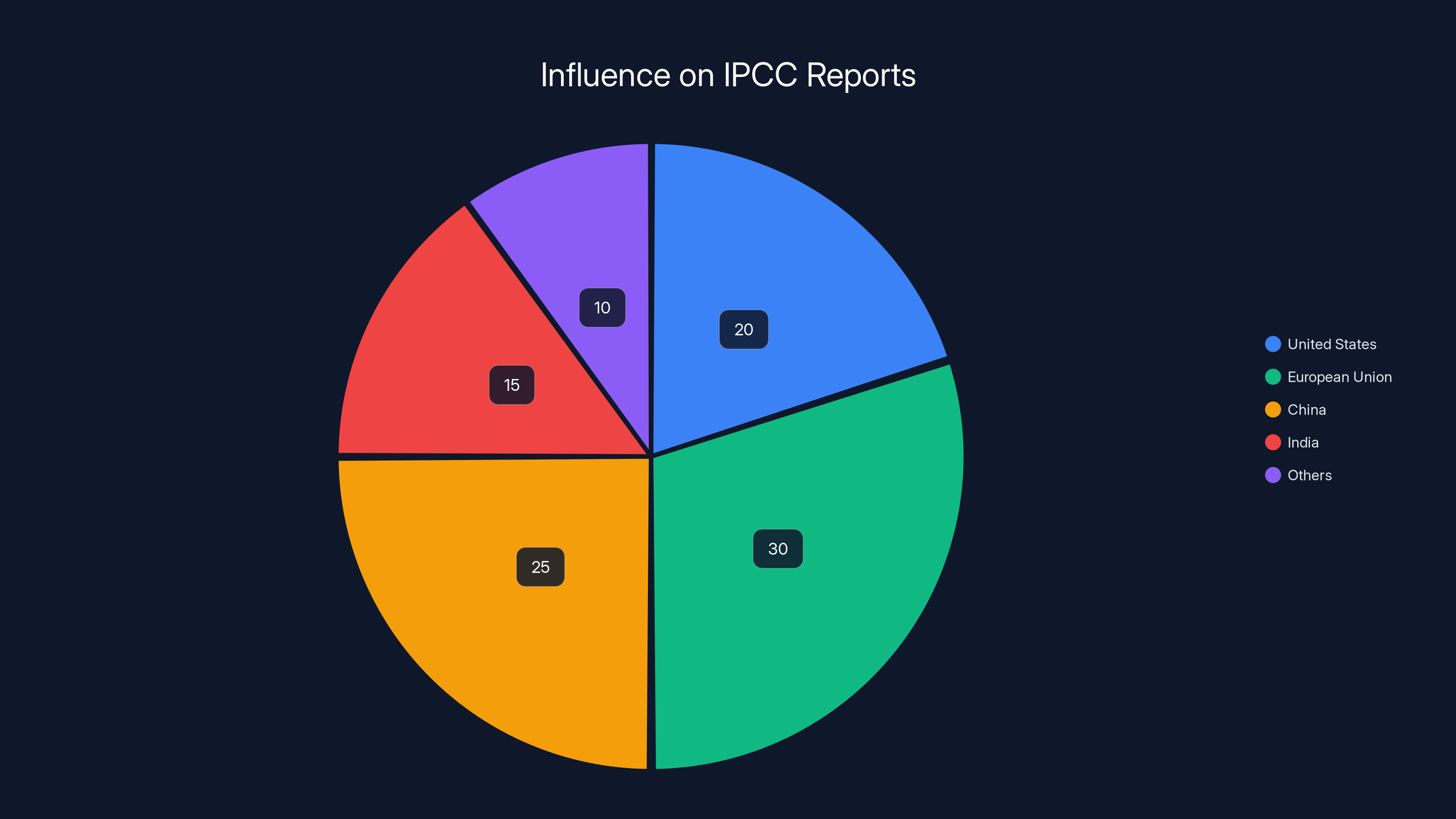

Estimated data shows climate organizations are the most affected by US withdrawals, comprising 30% of the total. This highlights a significant shift in US engagement with global climate policy.

Specific Organizations Targeted: A Detailed Breakdown

Let's examine the categories of organizations being abandoned and what each one actually does.

Climate and Environmental Organizations

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

Established in 1992, the UNFCCC is the foundational legal document for international climate negotiations. Every Paris Agreement negotiation, every climate summit, every international climate commitment flows from this framework. By withdrawing, the US is signaling it won't participate in future climate negotiations under this umbrella as reported by Reuters.

Here's what that means practically: When the next round of climate negotiations happens, the US won't have a seat at the table. Other nations will negotiate climate policies while America watches from the sidelines. That's a loss of diplomatic leverage, not a victory for American interests.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

The IPCC is different from the UNFCCC. It's not a negotiating body. It's a scientific assessment body that publishes comprehensive reports every five to seven years synthesizing the latest climate science. These reports have enormous influence on policy worldwide.

By withdrawing, American climate scientists can still participate in IPCC assessments (scientists participate as individuals, not government representatives). But the US government won't have a seat in IPCC governance, won't influence which topics get assessed, and won't participate in the approval process for reports as noted by BBC.

This is strategically foolish. If you disagree with the IPCC's conclusions, the smart move is to participate and argue your case. Withdrawing means you have zero influence but still face the consequences of their reports shaping global policy.

International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

The IUCN isn't primarily a UN body, though it has UN observer status. It's a network of governments, NGOs, and scientists focused on conservation. It maintains the Red List of Threatened Species, probably the most authoritative global database of extinction risk.

American participation in the IUCN gave us influence over conservation priorities, funding mechanisms, and which species get protection. Withdrawing reduces American conservation influence globally, though the practical impact might be modest since much conservation work happens through bilateral agreements and NGOs as discussed by The Japan Times.

Trade and Economic Organizations

International Trade Centre (ITC)

The ITC is a joint UN/World Trade Organization body that provides technical assistance on trade and competitiveness, particularly to developing countries. It's not a negotiating body. It doesn't set trade rules. It helps countries participate more effectively in trade.

This withdrawal is symbolically significant because it suggests the Trump administration wants even less international coordination on trade than previously. The US has already withdrawn from various trade agreements and tariffed partner nations. Further retreating from the ITC suggests a preference for bilateral deals over multilateral cooperation as noted by NPR.

Population, Migration, and Rights Organizations

UN Population Fund (UNFPA)

The UNFPA provides reproductive health services, maternal health programs, and family planning assistance globally, particularly in developing countries. The Trump administration has historically opposed funding for organizations that provide or advocate for abortion services, even though UNFPA itself doesn't perform abortions.

This withdrawal aligns with long-standing conservative positions on abortion and population policy. The practical effect is reduced funding for maternal health programs in developing countries, which will have measurable impacts on maternal mortality rates in poor regions as noted by Tax Notes.

Global Forum on Migration and Development

This forum facilitates dialogue between countries on migration policy. It's a deliberative body focused on finding common ground on how nations manage migration. By withdrawing, the US signals it won't participate in consensus-building on global migration policy, further isolating the US on this issue as discussed by Politico.

The Climate Change Angle: A Deeper Analysis

The climate angle deserves extended discussion because it's the most consequential and most ideologically charged aspect of these withdrawals.

What the IPCC Actually Does

There's enormous confusion about the IPCC's role. Some people think it's a lobbying organization for climate action. It's not. The IPCC is a scientific body that synthesizes peer-reviewed literature. It publishes reports—Assessment Reports published roughly every five to seven years, plus Special Reports on specific topics (like 1.5 degrees warming).

The IPCC doesn't conduct original research. It doesn't lobby for policies. It doesn't run programs. It convenes thousands of scientists who volunteer their time to assess "the state of knowledge" on climate change. The resulting reports are massively comprehensive—the latest Assessment Report was over 3,000 pages with tens of thousands of citations as reported by Engadget.

When the Trump administration calls the IPCC "radical," it's using rhetorical language that doesn't match what the IPCC actually is. The IPCC's conclusion that human-caused climate change is happening and is significant doesn't come from ideology. It comes from the accumulated weight of evidence.

Now, people can reasonably disagree about what policies to adopt in response to climate change. Some think we need massive carbon taxes and rapid fossil fuel phase-outs. Others think adaptation, nuclear power, and market-driven solutions are better. Those are legitimate policy disagreements. But disagreeing with policy recommendations isn't the same as withdrawing from the scientific assessment process.

By withdrawing, the US loses the ability to influence which aspects of climate science get emphasized, which research gets cited, which uncertainties get highlighted. The IPCC will continue publishing reports without US input. Those reports will still shape global policy. But America will be less influential in shaping them as reported by Reuters.

The Paris Agreement Withdrawal (Again)

The Trump administration withdrew from the Paris Agreement in his first term (taking effect in late 2020), then Biden rejoined immediately upon taking office in 2021. Now we're withdrawing again. This is the second time in five years.

The Paris Agreement is not a binding treaty in the traditional sense. It doesn't have enforcement mechanisms. Countries pledge to reduce emissions based on what they think is achievable, then report their progress. The goals are aspirational—limiting warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, preferably 1.5 degrees.

From an American perspective, the Paris Agreement has minimal costs. We're committing to reduce emissions, but how we do that is our choice. We could do it through carbon taxes, regulations, technology deployment, whatever we prefer. The agreement doesn't dictate methods, just outcomes as reported by CNN.

Still, Trump views the agreement as unfairly burdening the US compared to other countries, particularly China and India. This criticism has some historical basis—those countries have larger populations and smaller per-capita emissions, so the agreement's relative flexibility toward them can seem unfair. But the solution isn't withdrawal. It's renegotiation, which the administration hasn't pursued.

The Geopolitical Implications

Here's where withdrawal gets strategically concerning. Climate change is becoming a major geopolitical issue. As impacts intensify—migration, resource scarcity, weather impacts—countries increasingly view climate policy as a strategic priority.

By withdrawing, the US cedes influence over how the world addresses these issues. China, meanwhile, is positioning itself as a climate leader. It's not actually reducing emissions as fast as it claims, but it's successfully branding itself as climate-conscious globally. That soft power advantage goes to China when America withdraws as reported by Earth.org.

Similarly, the EU is moving forward with aggressive climate policies and carbon border adjustment mechanisms that will eventually affect American companies. The US could be at the table shaping these policies or fighting against them directly. Instead, we're watching from the outside.

The irony is that fossil fuel interests—which benefit from reduced climate regulation—don't actually benefit from America being weak and isolated on climate policy. They benefit from American influence being used to weaken climate agreements globally.

What Withdrawal Actually Means: Practical Implications

Thinking about these withdrawals requires distinguishing between symbolic effects and practical effects. Both matter, but in different ways.

The Symbolic Impact

Withdrawing from these organizations is a clear statement. It says: The US government does not view international cooperation on climate as a priority. It says: American sovereignty matters more to us than global consensus-building. It says: We're prioritizing our own preferences over the long-term institutional relationships that have given the US influence.

Symbolic statements matter in international relations because they influence how other countries perceive you. If America repeatedly demonstrates that it won't honor long-term commitments, other countries adjust their expectations accordingly. They invest less in relationships with us and more in backup plans.

This is particularly significant for climate negotiations. If the US announces we're withdrawing from climate bodies, why would other countries view American climate pledges as credible? We've just demonstrated we won't stay committed as noted by NPR.

The Institutional Impact

The practical institutional impact varies. For some organizations, US withdrawal will be noticeable but manageable. For others, it could be transformative.

The UNFCCC will continue functioning without US participation. Over 190 nations participate in climate negotiations. The US walking out is significant—we're the largest historical emitter of greenhouse gases—but it doesn't paralyze the institution.

Meanwhile, funds that the US contributed to these organizations must be replaced by other sources or the organizations cut programs. For example, if the US stops funding certain UNFPA programs, those programs either get defunded or other countries increase their contributions.

What's more interesting is how American withdrawal creates opportunities for other countries. When the US abandons the field, countries like China, the EU, and India position themselves to fill the vacuum. They propose funding mechanisms, policy directions, and governance changes that reflect their interests. American withdrawal makes all this easier as reported by BBC.

The Diplomatic Fallout

Many countries, particularly US allies, view these withdrawals negatively. The EU, in particular, has made climate action central to its identity and policy. When America withdraws from climate bodies, it's read as a direct rejection of priorities the EU cares about.

This damage is particularly significant because American diplomacy hasn't been leveraged to explain the withdrawal or negotiate what comes next. The administration simply announced it. No consultation with allies. No attempt to find middle ground. Just withdrawal.

Historically, when the US has disagreed with international bodies, we've argued our case, tried to reform institutions, negotiated amendments. This administration prefers to simply walk away. That approach is faster but costs diplomatic capital as reported by Reuters.

Entitlements dominate the federal budget at

The Economic Question: Real Savings vs. Soft Power Loss

Let's do some math on the financial implications, because the White House claims savings but hasn't specified amounts.

Estimating US Contributions

The US contributes to various UN budgets in different ways:

Core UN Budget: The UN regular budget is about

Voluntary Contributions: Beyond assessed contributions, the US makes voluntary contributions to specific UN agencies and programs. This typically totals $1-2 billion annually.

Now, how much of this is devoted to the 66 organizations we're withdrawing from? The answer is complicated because some organizations we're leaving are integral to the UN system (like UNFCCC), while others are separate entities.

For climate-specific organizations:

- UNFCCC: The US contributes roughly $50-100 million annually to UNFCCC activities

- IPCC: US contributions are much smaller, maybe $5-10 million

- UNFPA: US contributions were around $32 million before previous administrations withheld them

- Other organizations: Collectively, probably another $100-150 million

Total estimated annual savings: $200-350 million

That's meaningful money. It's also about 0.005% of the annual federal budget (roughly $6.75 trillion). It's significant enough to matter to the organizations affected but small enough that the claim of major budgetary savings is overstated as reported by Earth.org.

The Soft Power Cost

Here's what's harder to quantify: the cost of lost influence.

American participation in these organizations gives us three things:

- Agenda-setting power: We influence which issues get addressed and how

- Information access: We get visibility into what's happening in these institutions

- Diplomatic currency: Other countries know we take these issues seriously

By withdrawing, we lose all three. We no longer shape the climate change narrative at the international level. We lose visibility into what climate negotiations are happening. And we signal that climate issues aren't important to us.

The geopolitical return on that $200-350 million in contributions is probably enormous. We're getting influence over global climate policy for a tiny fraction of government spending. Withdrawing to save that money is like a tech company eliminating its research division to improve quarterly earnings as discussed by Politico.

Historically, this is how great powers lose influence. They economize on foreign engagement, let relationships atrophy, and find themselves isolated when they need allies.

The Broader Pattern: Retreat From Multilateralism

These withdrawals aren't happening in isolation. They're part of a broader pattern of American retreat from multilateral institutions and agreements.

The Trade War Dimension

The Trump administration's approach to trade has been aggressively unilateral. It's imposed tariffs on allies and adversaries alike, withdrawn from trade negotiations, and threatened to leave trade organizations.

In 2025, the US withdrew from trade talks with Canada over digital services taxes. This isn't about American economic interests. Canada's digital services tax is a minor imposition. It's about the principle that the US won't tolerate policy directions it dislikes as noted by NPR.

The administration also banned EU commissioner Thierry Breton for his role in the Digital Services Act. The Digital Services Act is genuinely consequential—it does affect American tech companies. But banning a European politician is a dramatic escalation. It signals that the US is willing to engage in personal retaliation for policy disagreements.

All of this fits a pattern: the Trump administration prefers bilateral relationships where the US has maximum power over consensual multilateral frameworks where America must negotiate.

The Health and Human Rights Dimension

Withdrawing from organizations focused on reproductive health and migration reflects ideological priorities too. The administration is hostile to family planning assistance and views migration through a security lens rather than a humanitarian one.

These aren't just policy differences. They reflect fundamentally different worldviews about America's role internationally. Is America a partner in global efforts to improve human welfare? Or is America a nation that privileges its own citizens over international cooperation?

Different people will answer that question differently. But the administration's answer is increasingly clear: we're choosing the latter as reported by Reuters.

International Response and Realignment

How are other countries responding to American withdrawal?

The European Union

The EU is treating these withdrawals seriously. European leaders recognize this as part of a broader pattern of American disengagement from shared commitments.

Internally, the EU is accelerating its own climate initiatives. If the US won't participate in climate governance, the EU will move forward and attempt to shape global climate policy without American input. This actually advantages the EU—they get to set the agenda without American obstruction.

But it also marginalizes America. Climate policy is becoming a defining feature of 21st century international relations. By stepping away, the US is letting other powers define how climate issues get addressed globally as reported by Engadget.

China and Russia

China is undoubtedly pleased. As the US withdraws from climate governance, China can position itself as a climate leader (even if actual emission reductions are questionable). This is a huge soft power gain.

Russia is in a similar position. The US withdrawal means Russia doesn't have to contend with American pushback on its own climate policies and environmental practices.

Meanwhile, both countries are strengthening their own multilateral relationships. China's Belt and Road Initiative, Russia's relationships with former Soviet states—these are being weaponized as the US retreats from traditional multilateral institutions as discussed by Politico.

Developing Countries

Developing countries are most directly affected. Many rely on international bodies for technical assistance, funding, and voice in global governance. With the US withdrawing, funding sources disappear.

At the same time, some developing countries may benefit. If the US is withdrawing from organizations that constrain their autonomy, they gain more freedom. But overall, the loss of US funding and technical assistance is probably negative for most developing nations as reported by Earth.org.

Estimated influence of various countries on the content of IPCC reports. The US withdrawal may reduce its influence, affecting which aspects of climate science are emphasized. (Estimated data)

The Climate Science Dimension: Understanding the Withdrawal's Rationale

To fully understand these withdrawals, we need to examine how the Trump administration thinks about climate science.

Fundamental Disagreement About Climate Change

The Trump administration doesn't just disagree with climate policies. At a fundamental level, senior officials in this administration are skeptical that climate change is a serious problem requiring urgent action.

Trump himself has called climate change a "hoax." Other members of the administration have expressed similar skepticism. This isn't about disagreeing on optimal climate policy. It's about disagreeing on whether the problem exists as reported by CNN.

This creates a difficult situation for climate institutions like the IPCC. The IPCC's entire purpose is assessing what climate science actually shows. If you fundamentally reject the scientific consensus, participating in the IPCC becomes a problem. You're either participating in an institution you view as invalid (which seems pointless) or you're fighting constant battles to change conclusions you think are wrong (which seems futile).

Withdrawal sidesteps this dilemma. It says: We don't believe in this institution's basic mission, so we're leaving.

The Role of Ideology in Science Skepticism

Why is climate change skepticism so prevalent in certain conservative circles? Multiple factors:

- Fossil fuel industry relationships: Some skepticism is directly funded by fossil fuel interests

- Libertarian philosophy: Many conservatives view climate regulations as government overreach

- Epistemological differences: Some conservatives are skeptical of expert consensus more broadly

- Cultural identity: Climate skepticism has become part of conservative identity politics

- Media environment: Conservative media outlets frequently discuss climate science skeptically

None of these factors mean climate science is wrong. Scientific consensus doesn't prove something true, but it's a good starting point for policy. The question is: why adopt a different starting point?

The administration's answer seems to be: because the policies that follow from climate science consensus conflict with our broader economic philosophy as reported by Reuters.

The Future of American Climate Science

Withdrawing from the IPCC doesn't mean Americans stop doing climate research. It means the US government won't participate in translating that research into international policy.

American climate scientists will continue publishing in peer-reviewed journals. American universities will continue training climate scientists. But the US government will have less influence over how international climate science gets interpreted and applied.

Long-term, this could mean brain drain. If the US government views climate science skeptically, funding for climate research might decrease. Scientists might migrate to other countries with more supportive governments. This would weaken American scientific capacity in a field that will be increasingly important as reported by Earth.org.

What These Withdrawals Mean for American Sovereignty

The White House argues these withdrawals protect American sovereignty. Let's examine that claim carefully.

The Sovereignty Argument

Sovereignty means a nation has the right to govern itself without external interference. By that definition, participating in international organizations does constrain sovereignty—other nations get a voice in decisions that affect you.

But here's the thing: international organizations are voluntary associations. The US joined them deliberately. We did so because we calculated that the benefits of cooperation exceeded the costs of sovereignty constraints.

The question isn't whether international organizations constrain sovereignty. They do. The question is whether the constraints are justified by the benefits.

For climate organizations, the benefits are:

- Scientific legitimacy: The IPCC provides authoritative assessments that shape global markets and policy

- Diplomatic influence: Participating in UNFCCC negotiations gives the US leverage over climate policy direction

- Technology development: International cooperation accelerates development of clean energy technologies

- Risk management: Climate change poses risks to American interests (coastal property, agriculture, military installations, etc.)

The costs of participation are:

- Policy constraints: We commit to certain emission reduction targets

- Financial contributions: We fund organizations and support developing countries

- Domestic political constraints: We can't pursue policies that violate agreements

From an American economic perspective, the benefits almost certainly outweigh the costs. But this assumes you view climate change as a real problem requiring action. If you think climate change is exaggerated or that adaptation is better than mitigation, then the sovereignty constraints look worse as discussed by Politico.

Negative Sovereignty Loss Through Withdrawal

Here's an ironic point: withdrawing from international organizations can actually reduce sovereignty.

When you participate in an organization, you help set the rules. You have voice and vote. When you withdraw, you lose that voice, but the organization continues. Other nations set the rules without you.

Imagine a hypothetical trade negotiation. Country A participates, tries to shape the agreement, but doesn't get everything it wants. Country A could withdraw or accept the agreement. If it withdraws, it's out of the negotiation. Other countries finalize the agreement without its input. Now Country A faces the agreement as an external constraint, with no voice in its design.

That's what's happening with climate policy. The US is withdrawing from the negotiation table. Other countries will continue negotiating climate policy without us. We'll still face the consequences of those policies (through carbon border adjustment mechanisms, supply chain preferences, etc.), but we won't have helped design them.

True sovereignty includes the power to shape the rules you live under. By withdrawing, we're trading the sovereignty to influence rules for the sovereignty to refuse participation. That's a worse deal as reported by Engadget.

The Financial and Budgetary Reality Check

Let's revisit the claimed savings with actual budget numbers.

Where the Money Goes

The federal government spends roughly

International affairs spending—which includes UN contributions, foreign aid, and diplomatic operations—is roughly $60 billion annually, or less than 1% of the federal budget.

Our estimated savings from these 66 withdrawals is $200-350 million. That's 0.003% of the federal budget. It's less than 0.6% of international affairs spending.

For perspective, that's roughly equivalent to one cruise missile (a Tomahawk costs about

The Accounting Problem

The White House's fact sheet on these withdrawals notably doesn't specify savings amounts. This is suspicious. If the savings were substantial, they'd publicize them. That they're vague suggests the actual savings are modest.

Moreover, some of these organizations will continue to exist and function whether or not we participate. They'll simply operate without American funding and without American influence. The world won't suddenly become less regulated or more free. It'll just be organized without American input as reported by Reuters.

The Opportunity Cost

Here's the real question: is $200-350 million in annual savings worth losing influence over global policy on climate, trade, migration, and conservation?

Historically, America has spent vastly more than this to maintain diplomatic influence. The Marshall Plan, for example, was roughly $140 billion in today's money to rebuild Europe after World War II. That was an investment in American interests—ensuring European stability and alliance.

Participating in international organizations is similarly an investment. The money buys influence. By withdrawing, we're cashing out that investment to solve a trivial budget problem as reported by Earth.org.

The US contributes significantly to various UN budgets, with estimated savings from withdrawing from certain organizations ranging between $200-350 million annually. Estimated data.

Long-Term Consequences: A Strategic Assessment

Thinking about the long-term implications requires considering multiple dimensions.

Climate Impacts

Without US participation in climate negotiations, global climate policy will move forward without American input. Other nations will set targets, establish mechanisms, and determine how climate policy gets funded.

The likely outcome is that climate policy becomes increasingly focused on carbon border adjustment mechanisms—tariffs on imports from countries with weak climate policies. The US is moving in the opposite direction, loosening climate policies. This puts American exporters at risk of carbon tariffs.

Meanwhile, the world won't actually reduce emissions faster because the US withdrew from climate negotiations. Emissions reduction requires technological change, economic transition, and behavioral change. American withdrawal doesn't stop any of that. It just removes American influence from the negotiating table.

The likely outcome: other countries move forward, implement carbon tariffs against US goods, and the US finds itself disadvantaged in global markets without having actually reduced emissions as discussed by Politico.

Geopolitical Realignment

American withdrawal from multilateral institutions is accelerating a broader geopolitical realignment. China and Russia are building their own networks of bilateral relationships and regional organizations.

The US global order—built on American military dominance and willingness to maintain multilateral institutions—is being replaced by a more fragmented world where regional powers exercise greater autonomy.

This isn't necessarily bad for America (some would argue it's overdue), but it does mean less American influence and less American ability to shape global direction. We're trading global hegemony for greater short-term autonomy as reported by Engadget.

Technology and Innovation

Many international organizations facilitate technology cooperation. The UNFCCC, for example, includes mechanisms for sharing clean energy technologies. By withdrawing, the US reduces access to these mechanisms.

Conversely, this could accelerate American domestic innovation as we rely less on international cooperation. But historically, international collaboration accelerates technological progress, not the opposite.

Democratic Legitimacy and Soft Power

America's greatest strength has always been soft power—the ability to convince other nations to follow our lead, not because we forced them but because they want to.

Withdrawing from international institutions erodes that soft power. It signals that we're not interested in consensus-building or democratic international governance. We're interested in dominating unilaterally.

Other countries notice. They adjust their strategies accordingly. They invest less in US relationships and more in backup options. Our global influence slowly erodes as reported by Earth.org.

What Remains: Organizations the US Still Participates In

It's worth noting that the US continues participating in some major institutions.

The International Energy Agency

The US remains involved with the International Energy Agency, which focuses on global energy security and clean energy deployment. This is interesting because it shows the withdrawal isn't absolute.

Why keep IEA participation? Probably because it focuses on energy independence and market-based solutions, which align better with the administration's ideology. The IEA emphasizes energy security and efficiency, not climate obligation.

But by staying in IEA while leaving UNFCCC and IPCC, we're saying we care about energy markets but not about climate. That's consistent but strategically unwise as reported by Reuters.

The World Health Organization (Not on the List)

Interestingly, the World Health Organization wasn't on this withdrawal list, though Trump previously threatened to withdraw. WHO participation remains valuable for pandemic preparedness and international health cooperation.

The selective nature of these withdrawals suggests the decision-making process was somewhat ideological rather than comprehensive. Climate and conservation organizations got targeted because of ideological opposition. But other organizations were evaluated on different criteria.

NATO and Defense Partnerships

The US continues with NATO and bilateral defense partnerships, though the Trump administration frequently complains about NATO funding levels. These remain core to American strategy because defense and deterrence are seen as fundamental to American interests.

This highlights an interesting inconsistency: the administration views defense partnerships as worth maintaining despite cost-sharing disputes. But views climate partnerships as not worth maintaining despite climate risks to American interests. The difference seems to be ideological rather than rational as reported by CNN.

The Path Forward: What Comes Next

Understanding where we go from here requires considering multiple scenarios.

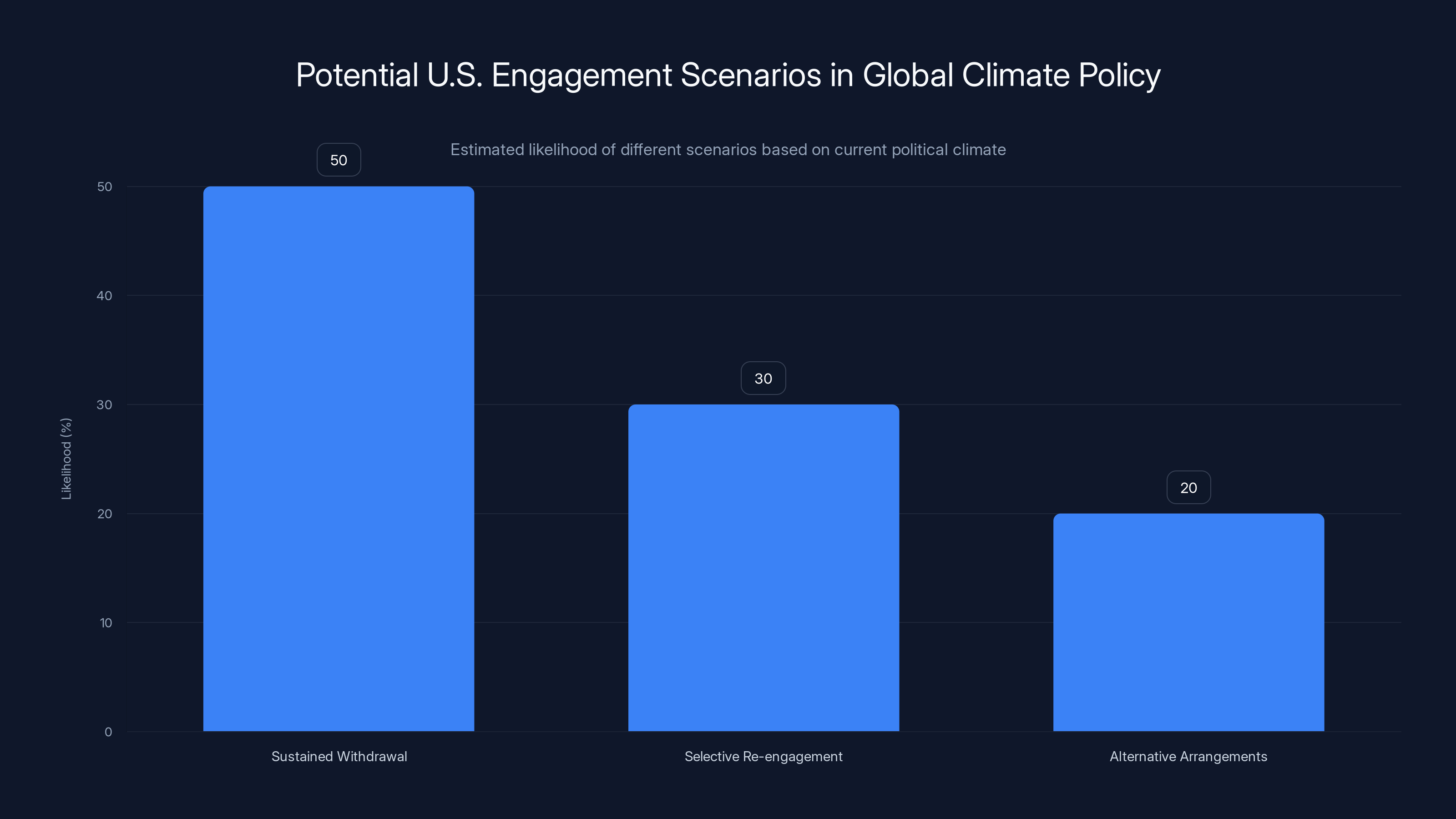

Scenario One: Sustained Withdrawal

The most likely scenario, given the administration's ideological consistency, is sustained American withdrawal from these organizations. We won't rejoin unless administrations change or there's a fundamental shift in how climate change is perceived politically.

In this scenario, America becomes a secondary player in global climate policy. We participate in some bilateral climate discussions, but we're not at the negotiating table for major agreements. Global climate policy evolves without us.

Other countries move forward with carbon tariffs, climate-linked trade restrictions, and carbon markets. American companies either adapt or face market disadvantages.

Scenario Two: Selective Re-engagement

Alternatively, the administration might discover that withdrawal creates practical problems. As trade partners implement carbon tariffs, as supply chains get disrupted, as climate impacts increase, there might be pressure to re-engage.

This would probably happen selectively. We might rejoin energy-focused organizations but stay out of climate organizations. We might participate in technology-sharing arrangements but not emissions reduction commitments.

But this requires the administration to recognize that withdrawal has costs. Currently, the rhetoric suggests they don't believe costs exist as reported by Engadget.

Scenario Three: Alternative Arrangements

Another possibility is that the administration creates alternative arrangements outside traditional UN structures. Rather than the UNFCCC, maybe a separate agreement among interested parties. Rather than IPCC, maybe alternative scientific assessments.

This is theoretically possible but practically difficult. Creating new institutions takes time and effort. The existing institutions have decades of legitimacy and participation. Starting over is expensive and uncertain.

Estimated data suggests 'Sustained Withdrawal' is the most likely scenario, with a 50% chance, followed by 'Selective Re-engagement' at 30%, and 'Alternative Arrangements' at 20%.

The Ideological Roots: Understanding Why This Happened

To fully understand these withdrawals, we need to examine the ideological commitments underlying them.

Conservative Distrust of Expertise

There's a broader pattern of distrust toward expert institutions in contemporary conservatism. The distrust of climate scientists parallels distrust of public health experts, election officials, and academic experts more broadly.

This distrust isn't entirely irrational. Experts sometimes get things wrong. Experts have professional incentives that might bias their recommendations. Democratic governance requires some skepticism of expert authority.

But the level of distrust in current conservative politics goes beyond healthy skepticism. It treats expert consensus as suspicious by definition. If most experts agree on something, that's treated as reason to doubt it rather than reason to give it credence as reported by Reuters.

This epistemological stance makes withdrawal from expert institutions logical. If the IPCC represents expert consensus, and you believe expert consensus is inherently suspect, then withdrawing from the IPCC is consistent.

Economic Interests vs. Ideological Commitment

It's worth asking: is this withdrawal driven by fossil fuel industry interests, or by genuine ideological opposition to climate action?

Probably both. Some members of the administration have fossil fuel industry ties. But others seem genuinely convinced that climate policies are economically harmful and that climate science is exaggerated.

The distinction matters because the policy implications are different. If this is industry-driven, it might be reversible with political change or industry evolution. If it's ideologically driven, it might be more durable as reported by CNN.

National Populism and International Skepticism

These withdrawals also reflect a broader national populist ideology that's skeptical of international institutions. From this perspective, international organizations represent unaccountable global governance that constrains national democracy.

This concern has legitimate roots. International organizations do make decisions that affect national policy. Democratic accountability for those decisions is often weak. Citizens of individual countries can't directly vote out international institutions they disagree with.

But the solution isn't withdrawal from international cooperation. It's reform of international institutions to improve democratic accountability.

Withdrawal assumes that national self-determination is more important than international cooperation. But many issues—climate, pandemics, trade—require international cooperation to solve effectively. Prioritizing national autonomy over cooperation means not solving these problems effectively as reported by Earth.org.

Comparative Analysis: How the US Compares to Other Countries

It's useful to consider how other major countries approach similar issues.

The European Approach

The EU has doubled down on climate commitment. It's implementing aggressive emission reduction targets, carbon border adjustment mechanisms, and green finance initiatives.

The EU treats climate policy as a strategic priority, not an economic burden. This is partly because climate change poses direct risks to Europe (Mediterranean drying, ecosystem collapse, migration pressure from African countries) and partly because the EU views climate policy as compatible with economic competitiveness.

From a European perspective, the US withdrawal is baffling. Why would the largest, richest country abandon influence over an area of increasing global importance?

The Chinese Approach

China remains in international climate organizations despite genuine tensions with Western environmental standards. China is not reducing emissions fast enough to meet its own targets, but it maintains the institutional relationships.

China's strategic calculation is clear: it wants a seat at the table shaping global climate policy. By participating, China can influence which countries face pressure, which technologies get preferred, which financing mechanisms get established.

By withdrawing, the US is allowing China to fill that strategic space as discussed by Politico.

The Indian Approach

India remains committed to international climate negotiations despite significant tensions with climate finance commitments. India views climate negotiations as crucial to protecting its interests as a developing nation.

India's presence means that developing countries have a voice. When the US withdraws, developing countries lose a powerful voice advocating for their interests against India's.

The Contrast

The contrast is striking: nearly every other major power treats international climate organizations as strategically important. The US, the most powerful economy, is the outlier in withdrawing.

This suggests that either:

- The US has some unique insight about the costs of participation that other countries lack, or

- The US is making a mistake driven by ideology rather than strategic calculation used by most nations

Given that no other countries are withdrawing, and several countries are accelerating commitment, the latter seems more likely as reported by Earth.org.

The Technology and Innovation Question

One argument for international cooperation on climate is that it accelerates technology development.

How International Cooperation Drives Innovation

Clean energy technologies—solar, wind, batteries, electric vehicles—have advanced partly through international cooperation. Technology-sharing agreements, joint research programs, and coordinated standards have all accelerated development.

America has benefited from this cooperation. American solar companies benefit from global manufacturing standards. American EV manufacturers benefit from global charging networks. American researchers benefit from international collaboration.

Withdrawing from international bodies doesn't prevent American companies from participating in global markets, but it reduces American government's influence over how those markets develop.

Technological Autonomy vs. Global Integration

There's an ideological argument that America should pursue technological autonomy—developing solutions independently rather than relying on international cooperation.

This has intuitive appeal but practical problems. Technological development is increasingly globalized. Battery technology development involves China, South Korea, the US, and Europe. Solar technology development spans multiple countries. Wind turbine development is global.

Trying to develop these technologies autonomously would slow American innovation while increasing costs. It's the opposite of what American companies and American consumers benefit from as reported by Engadget.

What This Means for Future Energy

The US is withdrawing from climate organizations at the exact moment when energy transition is accelerating. Solar and wind are becoming cheaper than fossil fuels. Electric vehicles are becoming competitive with internal combustion. Battery technology is rapidly improving.

American companies could be leading these transitions globally, but that requires participation in international markets and coordination on standards. Withdrawal reduces American ability to shape these transitions.

Domestic Political Implications

These withdrawals have significant implications for domestic American politics.

The Green Economy Divide

America is increasingly divided on climate and green energy. The coasts and urban areas tend to support green energy transition. Rural areas and coal-dependent regions tend to oppose it.

Withdrawals from international climate bodies reflect and reinforce this divide. Rural America gets reassurance that climate regulations won't be imposed internationally. Urban America loses reassurance that America is addressing climate change.

But the underlying conflict remains unresolved. Climate change will continue, weather impacts will continue, and the political divide will deepen as reported by Reuters.

The State vs. Federal Question

With the federal government withdrawing from international climate bodies, American states and cities are increasingly going their own way.

California, New York, and other states are implementing their own clean energy standards. Cities are committing to zero-carbon energy and transportation. Corporate sustainability commitments are accelerating.

This is actually positive in some ways—it allows policy experimentation. But it creates fragmentation. Different states have different standards, making it harder for companies to operate across states and compete globally.

The Corporate Response

Many large American corporations maintain climate commitments despite federal withdrawal. Microsoft, Apple, Google, and others have pledged to become carbon-neutral. This reflects corporate calculation that climate action is good for business.

Corporate decentralization of climate policy might be efficient, but it's also less coordinated than national or international policy. Markets work better with clear rules and incentives as reported by Earth.org.

The Cultural and Identity Dimension

These withdrawals also reflect cultural and identity politics around environmentalism.

Environmentalism as Cultural Marker

Environmentalism has become a cultural identity marker in American politics. Support for environmental protection and climate action tends to correlate with college education, coastal residence, and progressive politics.

Opposition to environmental regulations tends to correlate with rural residence, fossil fuel employment, and conservative politics.

This cultural dimension means climate policy debates aren't just about costs and benefits. They're about cultural identity. Withdrawing from climate organizations is a way for the administration to signal cultural alignment with its base.

The Trust Divide

The cultural divide is reinforced by distrust. Environmental advocates don't trust that conservative governments will implement climate policy fairly. Conservative advocates don't trust that climate science isn't exaggerated.

This mutual distrust makes compromise difficult. When the Trump administration withdraws from climate bodies, environmental advocates see it as confirmation that the administration is hostile to environmental protection. When the administration withdraws, conservatives see it as standing up to environmentalist pressure.

Bridging this divide would require building trust, but the withdrawal does the opposite as discussed by Politico.

The Comparison to Previous Administrations

Understanding these withdrawals requires understanding how they compare to previous US positions.

The Obama Administration

The Obama administration strongly supported international climate engagement. Obama personally championed the Paris Agreement and invested in clean energy. During this period, the US was a leader in international climate negotiations.

The shift from Obama to Trump represents a fundamental change in American climate policy. From leader to withdrawer. From investment to skepticism.

The Bush Administration

The George W. Bush administration was skeptical of international climate agreements, notably refusing to ratify the Kyoto Protocol. But it didn't withdraw from existing organizations.

The current administration is more aggressively withdrawing from actual institutions, not just declining new commitments. This is more extreme than previous skepticism.

Historical Context

America has historically been ambivalent about international cooperation. We've joined organizations, then withdrawn when they conflicted with current preferences. But the pattern from World War II onward was generally toward greater engagement.

The current withdrawals represent a reversal of that long-term trend. We're moving from a nation that builds and participates in international institutions to a nation that's increasingly skeptical of them as reported by Reuters.

FAQ

What is the Trump administration's stated reason for these withdrawals?

The White House claims these organizations "promote radical climate policies, global governance and ideological programs that conflict with US sovereignty and economic strength." The administration frames the withdrawals as protecting American sovereignty from unelected international bodies and saving taxpayer money, though specific savings amounts weren't provided as reported by CNN.

Why is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change specifically targeted?

The IPCC synthesizes climate science research into comprehensive assessment reports that inform global climate policy. The Trump administration views the IPCC's conclusions about human-caused climate change as ideologically motivated rather than scientifically grounded, and withdrawing allows the administration to demonstrate opposition to the scientific consensus on climate change as reported by Reuters.

How much money will the US actually save by withdrawing from these 66 organizations?

The White House didn't specify exact savings, but estimated annual US contributions to these organizations total approximately $200-350 million. That's roughly 0.005% of the federal budget. Many of the targeted organizations will continue functioning with reduced budgets or increased contributions from other nations, so the actual policy impact may be limited despite the significant symbolic gesture as reported by Earth.org.

What happens to ongoing projects and programs funded by US contributions?

Some programs will be absorbed by other nations or private donors. UN-affiliated organizations like the UNFPA will need to find alternative funding sources or scale back operations. Many technical assistance programs will be reduced or eliminated, particularly affecting developing nations that relied on US funding as reported by BBC.

How will this affect American climate scientists?

American climate scientists can still participate in the IPCC as individuals, but the US government won't have representation in IPCC governance. This reduces American influence over which research gets emphasized and how findings are interpreted, but doesn't prevent American scientific participation as discussed by Politico.

What is the expected international response?

EU leaders have expressed concern about American withdrawal from climate commitments. China and other nations are positioned to fill the policy vacuum left by US absence. Some analysts expect other nations to accelerate their own climate initiatives and potentially implement carbon tariffs on American goods to address the US retreat from climate governance as reported by Engadget.

Could the US rejoin these organizations in the future?

Yes, future administrations could reverse these decisions. However, institutional relationships and diplomatic credibility take years to rebuild. Countries that have experienced multiple US withdrawals and rejoinings (the Paris Agreement withdrawal-rejoinment being a prime example) may be more skeptical of American long-term commitment to international agreements as reported by CNN.

How does this compare to other countries' approaches?

Nearly all other major powers—China, the EU, India, Japan—remain committed to international climate organizations and have not withdrawn. The US is an outlier in this regard, suggesting the withdrawal reflects ideological rather than strategic calculation used by most nations as reported by Earth.org.

What are the long-term geopolitical consequences?

American withdrawal from global governance institutions gradually shifts global influence toward other powers. As the US steps back from setting international standards and norms, other nations fill that space. This doesn't immediately harm American interests, but over time reduces American soft power and strategic influence as reported by Reuters.

Is there any offset from remaining in the International Energy Agency?

Continuing US participation in the International Energy Agency provides some continued American engagement on energy issues, though the IEA focuses on energy security and markets rather than climate change. However, this limited engagement is insufficient to replace the strategic influence of participation in broader climate governance structures as discussed by Politico.

The Bottom Line: Sovereignty, Influence, and Strategic Missteps

These 66 withdrawals represent something significant that goes beyond climate policy. They represent a fundamental reassessment of America's role in global institutions.

The White House frames this as protecting sovereignty. But sovereignty that's exercised by withdrawing from the table isn't particularly powerful. It's the sovereignty of having no influence.

Historically, American power has come from setting the rules others follow. We built the international order after World War II. We championed trade agreements that benefited American companies. We led the technology revolution. We maintained the military superiority that let us protect our interests globally.

That power came from being at the table, not from leaving it.

The Trump administration seems to believe that walking away from international institutions is powerful. It's a statement of independence. But independence achieved through weakness isn't particularly valuable.

Withdrawing from climate organizations doesn't make America free to pursue fossil fuels indefinitely. Global markets will still reward clean energy. Competitors will still develop better solar panels and batteries. The world will still experience climate change and its consequences.

What withdrawal does is reduce American influence over how these things happen. We'll still live with the consequences. We just won't help shape them.

For nations and empires, that's typically how decline begins. Not with a dramatic collapse, but with a gradual ceding of influence. A decision here to withdraw from an organization, a decision there to stop participating in a negotiation, a series of choices that add up to a loss of power.

America has the resources and capacity to lead on climate and global governance. We're choosing not to. That's not strength. It's a strategic mistake dressed up in sovereignty rhetoric.

The withdrawals will stand as a marker of a moment when America decided that short-term autonomy mattered more than long-term influence. History will judge whether that was wisdom or folly as reported by Engadget.

Key Takeaways

- Trump administration withdraws from 66 international organizations, including IPCC and UNFCCC, representing unprecedented shift in US climate policy

- Estimated annual savings of $200-350 million is only 0.005% of federal budget, suggesting budgetary savings are overstated rationale

- US withdrawal removes American influence over global climate negotiations while other powers fill the vacuum left by American absence

- Climate withdrawals reflect broader pattern of American retreat from multilateral institutions in favor of unilateral autonomy

- Long-term geopolitical consequences include reduced American soft power, weakened diplomatic credibility, and advantage for competing powers

Related Articles

- US Withdraws From Climate Treaty: What It Means for Global Action [2025]

- Offshore Wind Developers Sue Trump: $25B Legal Showdown [2025]

- Trump's Offshore Wind Pause Faces Legal Challenge: Data Center Power Demand Crisis [2025]

- US Withdraws From Internet Freedom Bodies: What It Means [2025]

- Appeals Court Blocks Trump's Research Funding Cuts: What It Means [2025]

![US Withdrawal From 66 International Organizations: Impact on Global Governance [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/us-withdrawal-from-66-international-organizations-impact-on-/image-1-1767902893883.jpg)