Understanding Uganda's Internet Shutdown and VPN Collapse [2025]

In early 2025, Uganda experienced a crisis that rippled across the digital rights community. Internet connectivity across the country plummeted, and with it, VPN services that millions relied on suddenly became inaccessible. Proton VPN publicly confirmed that its services had stopped functioning in Uganda, marking a dramatic escalation in the country's ongoing struggle with digital suppression.

What made this different from typical VPN blocks wasn't just the technical sophistication of the blocking mechanism. It was the sheer scale of the connectivity loss. Uganda's internet infrastructure itself was compromised, not just the pathways VPNs typically use to bypass restrictions. This created an unprecedented situation where traditional workarounds simply didn't work anymore.

For journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens who depended on VPNs to access information freely, the shutdown felt like a digital iron curtain descending without warning. The timing wasn't accidental, either. Uganda has a documented history of using internet shutdowns as a tool during politically sensitive moments, as noted by Human Rights Watch.

This article dives deep into what actually happened in Uganda, why it matters globally, and what the collapse of VPN functionality reveals about the future of internet freedom. We'll explore the technical mechanisms behind the shutdown, examine the responses from VPN providers and digital rights organizations, and consider what limited workarounds actually remain available.

TL; DR

- Major VPN Providers Failed: Proton VPN and other services stopped working in Uganda due to internet connectivity collapse, not just protocol blocking

- Broader Infrastructure Attack: The shutdown targeted Uganda's underlying internet infrastructure itself, making traditional VPN workarounds ineffective

- Timing Pattern: Internet restrictions occurred during politically sensitive periods, continuing Uganda's documented pattern of digital suppression

- Limited Workarounds: Digital rights experts confirmed that technical workarounds are extremely limited when entire connectivity drops

- Global Implications: Uganda's shutdown demonstrates how authoritarian regimes can scale internet control beyond VPN blocking to infrastructure-level attacks

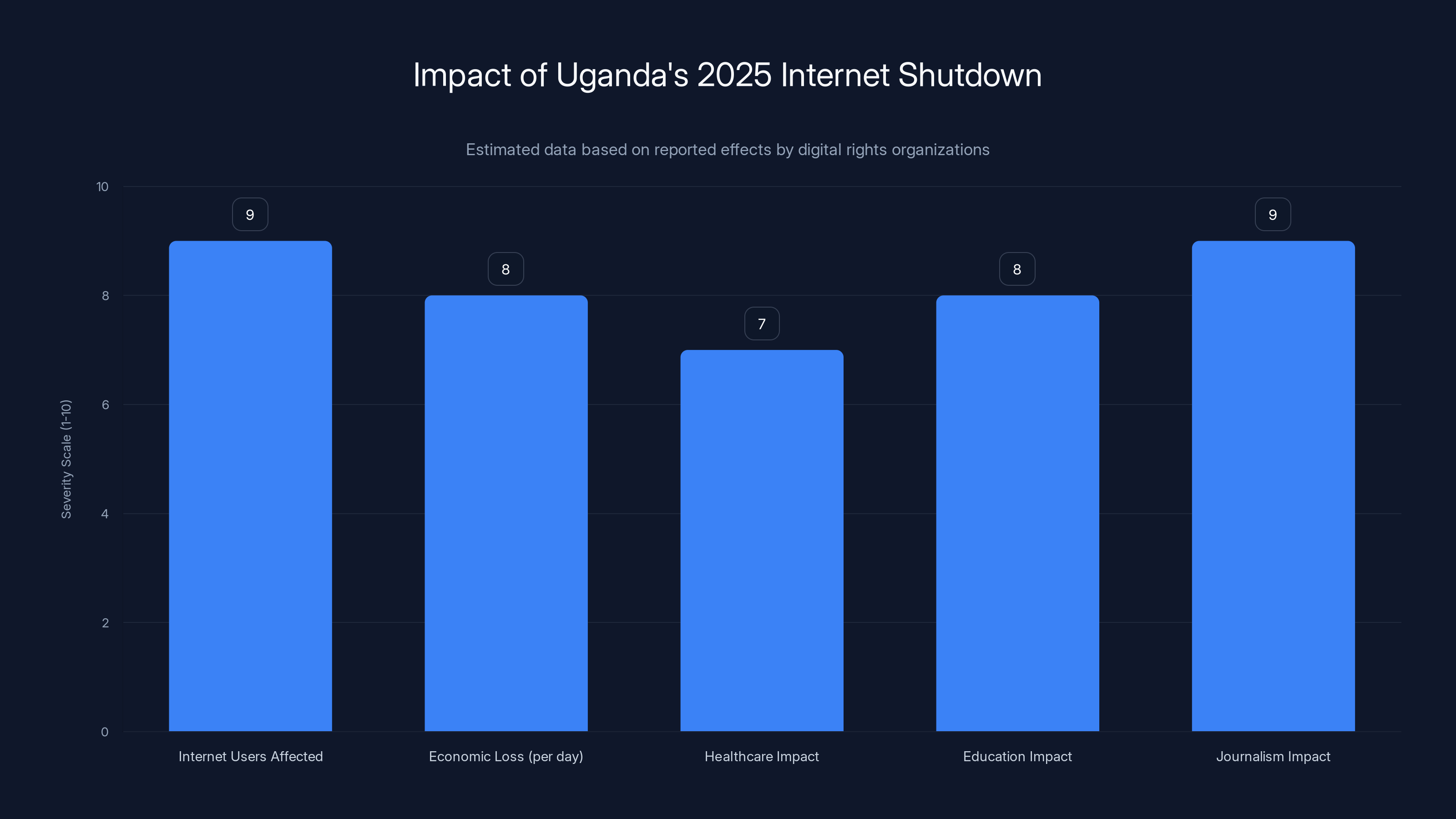

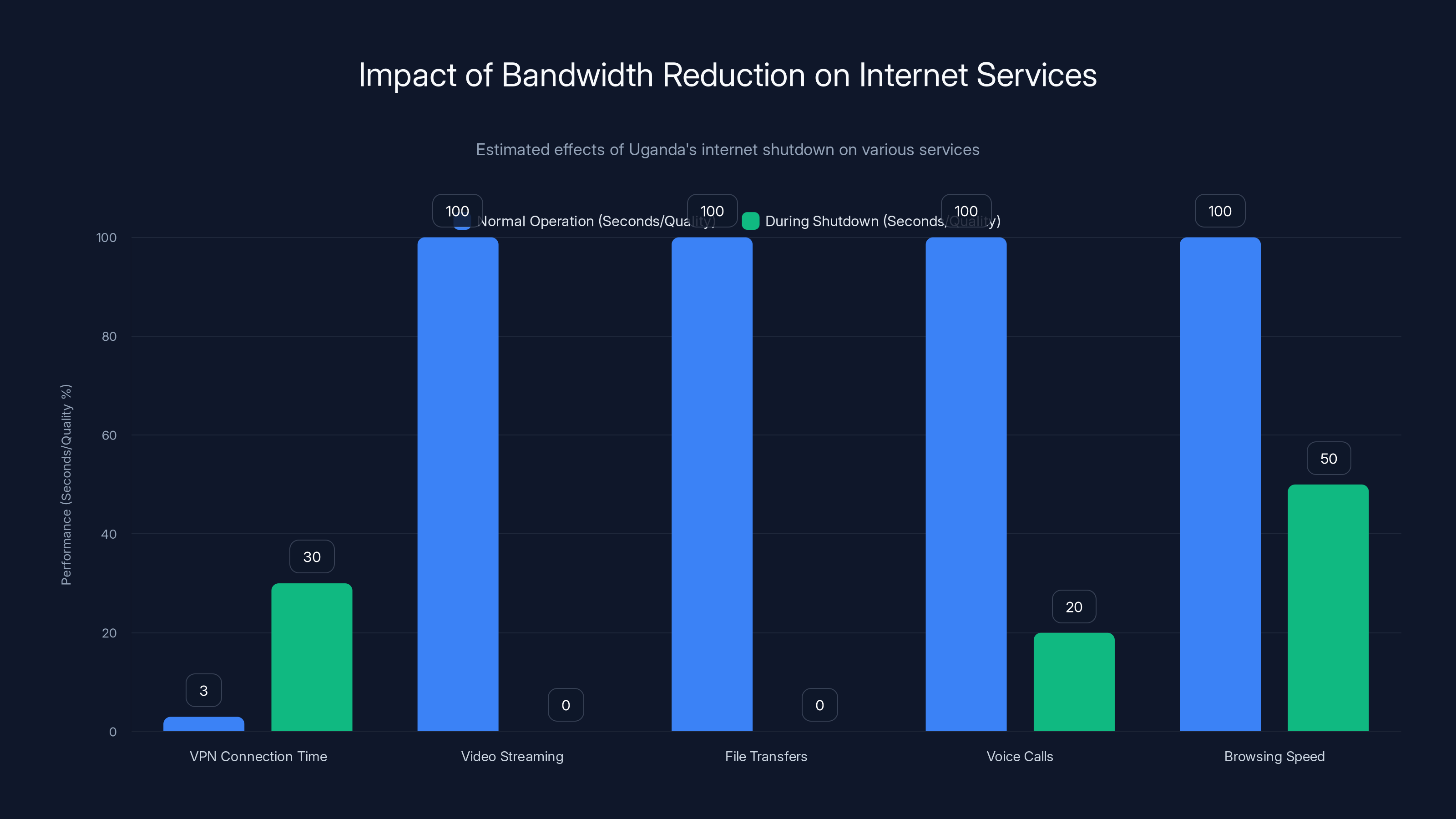

The 2025 internet shutdown in Uganda had severe impacts across multiple sectors, with millions affected and significant economic losses. (Estimated data)

The Context: Uganda's Long History of Internet Control

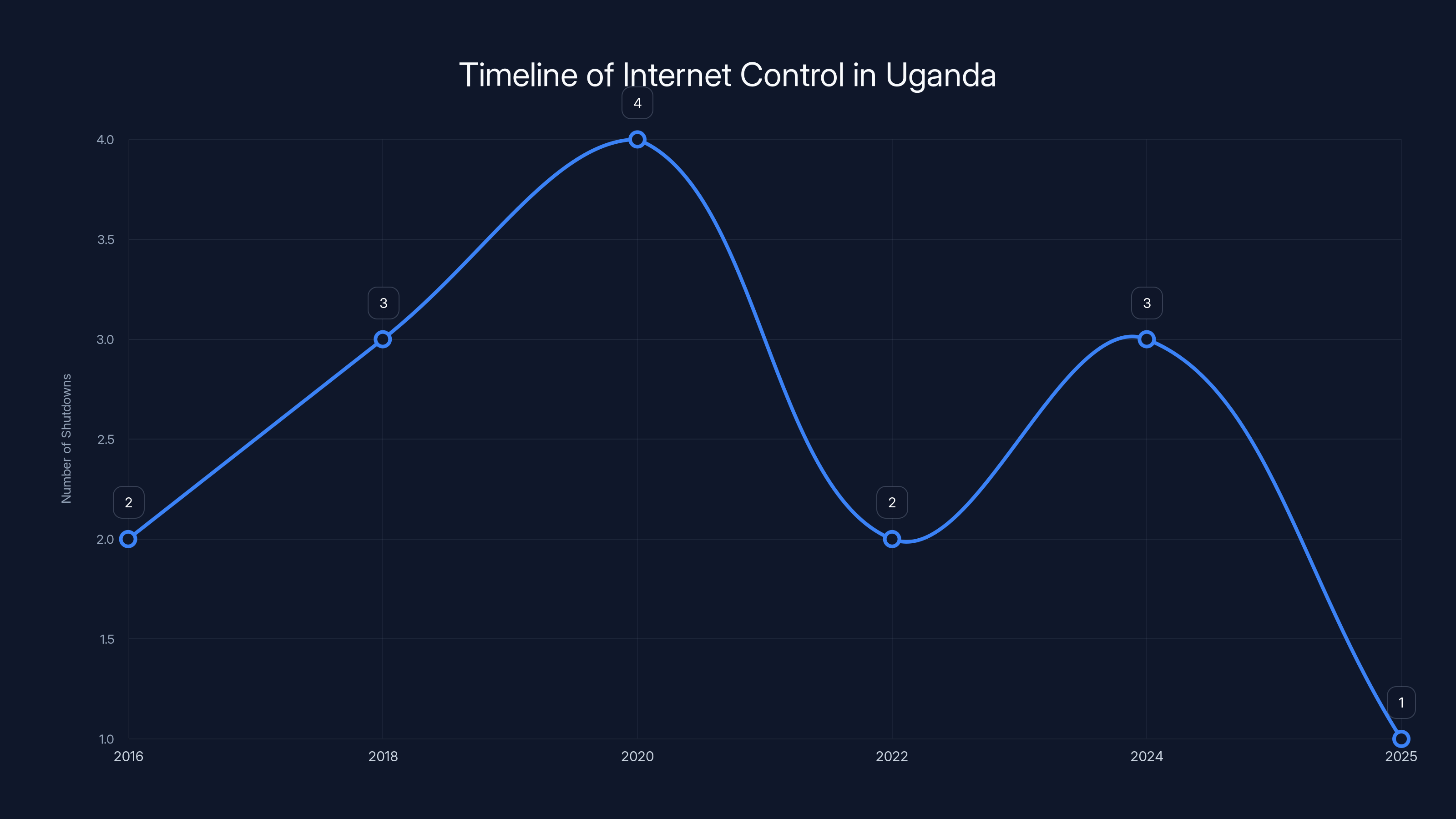

Uganda didn't wake up one morning and suddenly decide to shut down the internet. The country has been gradually tightening its digital grip for years, with a documented pattern of restrictions during politically significant moments. According to TechRadar, this pattern has been evident during elections and other critical periods.

Beginning around 2016, Uganda started blocking social media platforms during elections. These weren't accidental outages, but deliberate government actions targeting specific services. Over time, the sophistication of these blocks increased. Instead of just shutting down Facebook and Twitter, authorities began blocking VPNs that people used to circumvent the initial restrictions.

The government's technical approach evolved each time people found workarounds. When simple IP blocking failed, more sophisticated deep packet inspection (DPI) technology was deployed. This technique allows authorities to identify VPN traffic by analyzing the patterns of data flowing across the network, even when the destination is hidden.

By 2024, Uganda's regulatory environment had grown increasingly hostile to digital freedom. The government passed laws like the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, which criminalized various online activities and gave authorities broad powers to monitor and control internet usage.

What happened in early 2025 represented a new escalation: moving from blocking specific services to reducing overall internet connectivity to the country.

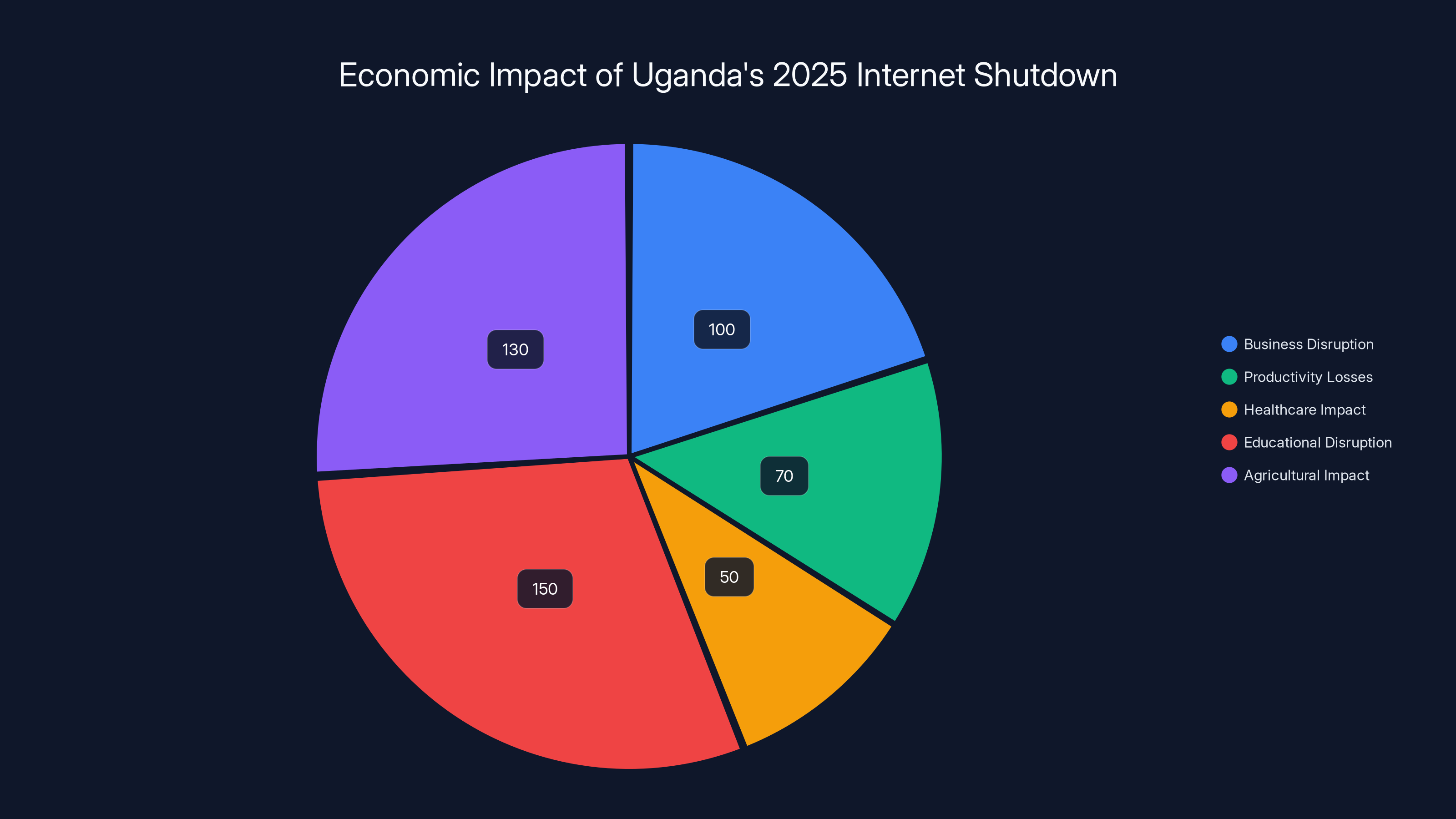

The pie chart illustrates the estimated economic losses across various sectors due to Uganda's 2025 internet shutdown. Educational disruption and agricultural impact were particularly significant, highlighting the broad societal effects. Estimated data.

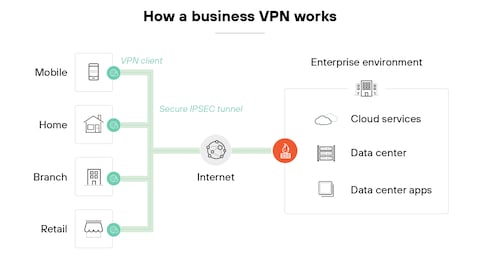

How VPNs Actually Work (And Why They Failed)

To understand why VPNs stopped working in Uganda, we need to understand how they function in the first place. A VPN (Virtual Private Network) creates an encrypted tunnel between your device and a remote server. All your internet traffic gets routed through this tunnel, which masks your actual location and makes your activities invisible to your Internet Service Provider (ISP) and local network monitors.

Typically, when a government wants to block VPNs, they use one of several techniques. The most basic is IP blocking: authorities maintain a list of known VPN server addresses and simply block traffic to those addresses. This works, but it's a never-ending game of whack-a-mole because VPN providers constantly add new server addresses.

More sophisticated blocking uses deep packet inspection (DPI). Instead of looking at where traffic is going, DPI technology examines the characteristics of the traffic itself. VPN connections have distinctive patterns that DPI systems can recognize. When identified, the traffic gets blocked at the protocol level.

The most advanced VPN blocking technology is called obfuscation detection. Even when VPN providers disguise their traffic to look like regular HTTPS web browsing, detection systems can still identify it through subtle timing patterns, packet sizes, and other fingerprints.

But in Uganda's case, something different happened. The problem wasn't that authorities got better at blocking VPNs specifically. Instead, they reduced overall internet connectivity to the country.

When your ISP can't maintain adequate bandwidth to the rest of the internet, VPNs become functionally useless even if they're technically unblocked. Imagine trying to drink from a firehose that's been turned down to a trickle. The connection exists, but it can't carry meaningful data.

The 2025 Shutdown: What Actually Happened

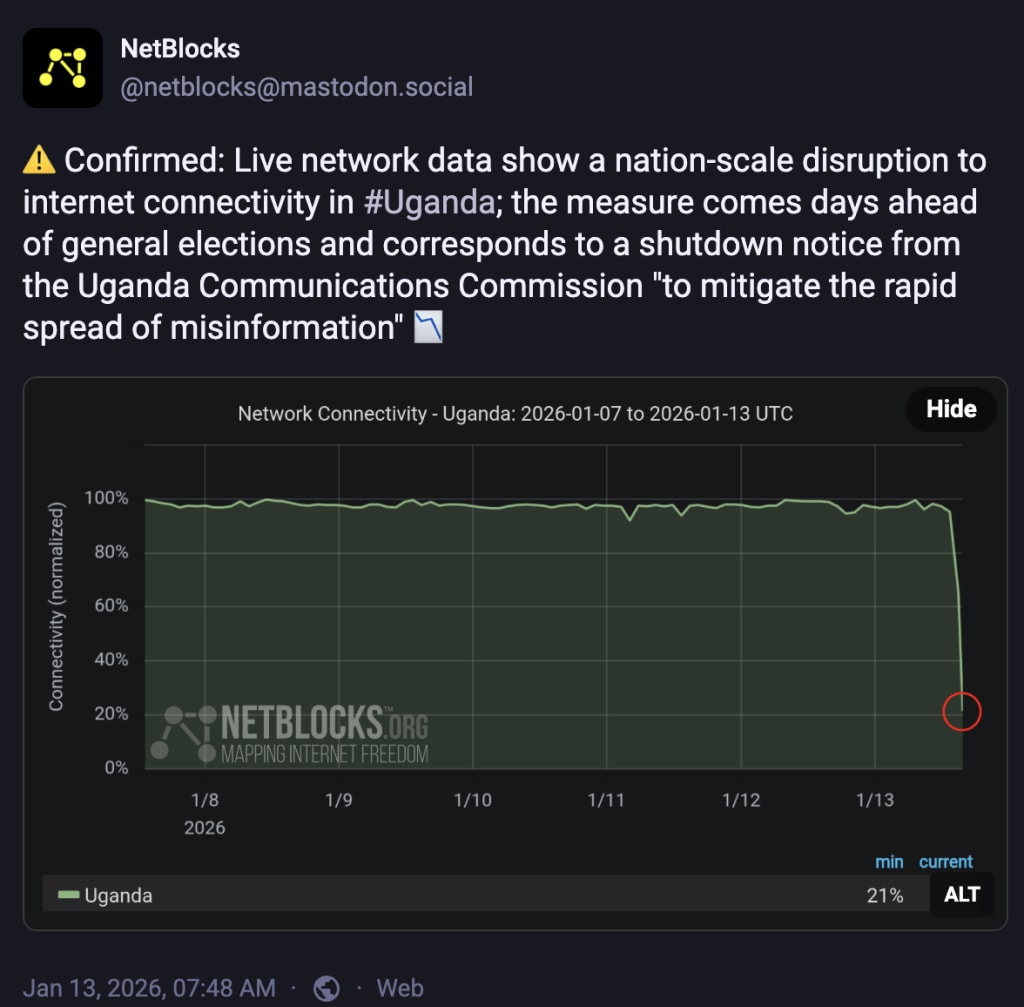

In the weeks leading up to the 2025 shutdown, Uganda's political situation grew increasingly tense. Preparations for elections created an atmosphere of uncertainty, and the government appeared to be preparing for potential unrest. Social media chatter about planned protests and political demonstrations began circulating online.

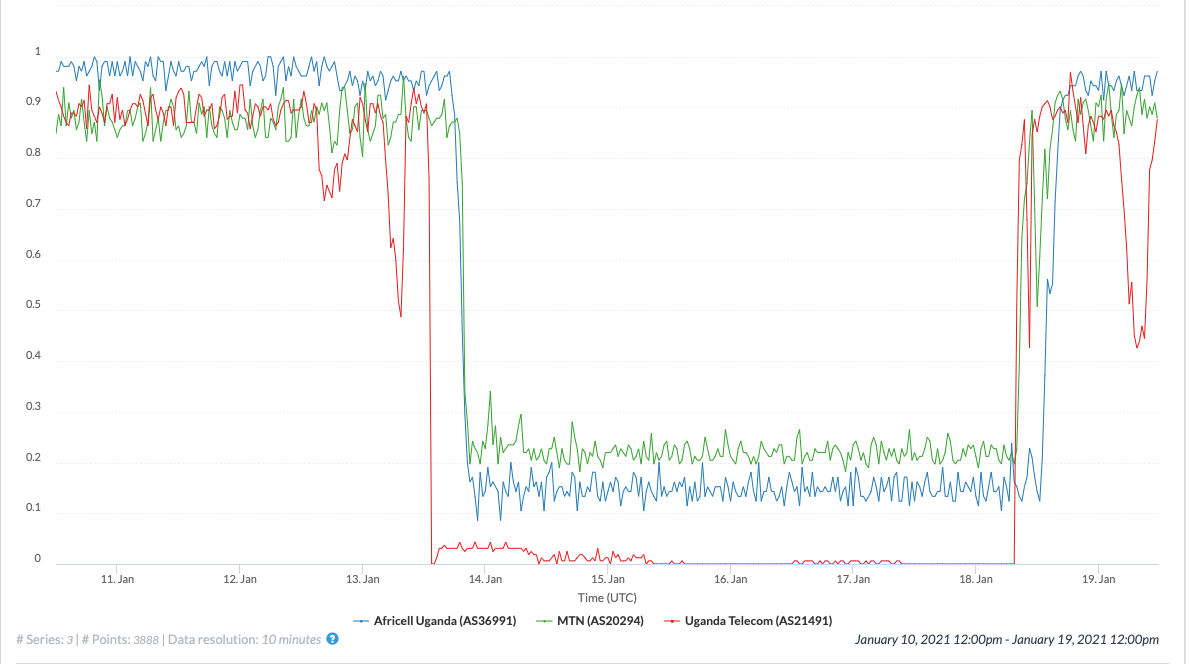

Then connectivity started dropping. Reports came in from across the country describing slower internet speeds, dropped connections, and services becoming intermittently unavailable. At first, people blamed technical issues. ISPs blamed infrastructure problems. But the pattern suggested something more deliberate.

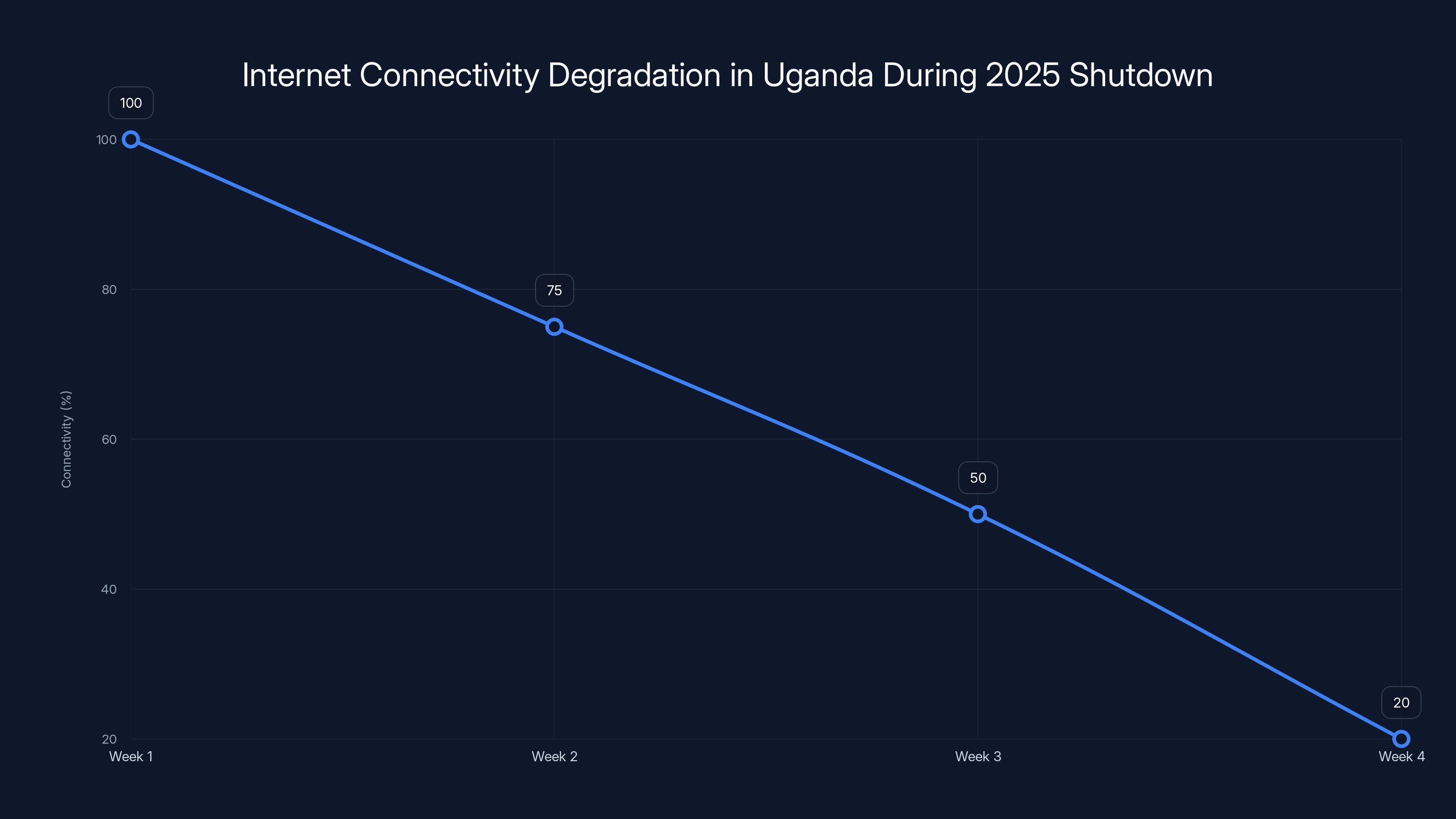

Within days, major internet providers across Uganda reported severely degraded service. The bandwidth available to the country appeared to have been deliberately constrained. This isn't a simple on-off switch; it's more like slowly closing a valve on the country's international internet connections.

Uganda's international internet traffic flows through several undersea fiber optic cables and terrestrial connections. While the government can't physically cut these cables, they can instruct telecommunications companies operating the infrastructure to reduce the capacity allocated to international traffic. This creates a bottleneck effect.

Proton VPN confirmed that their service became non-functional during this period. The company stated that users couldn't establish new connections, and existing connections dropped repeatedly. However, Proton clarified that their servers weren't specifically blocked. Instead, the underlying internet connectivity was so degraded that VPN tunneling became impossible.

This distinction matters enormously. When a VPN service is specifically blocked, you might find a workaround. When the entire internet pipe is squeezed, workarounds become nearly impossible.

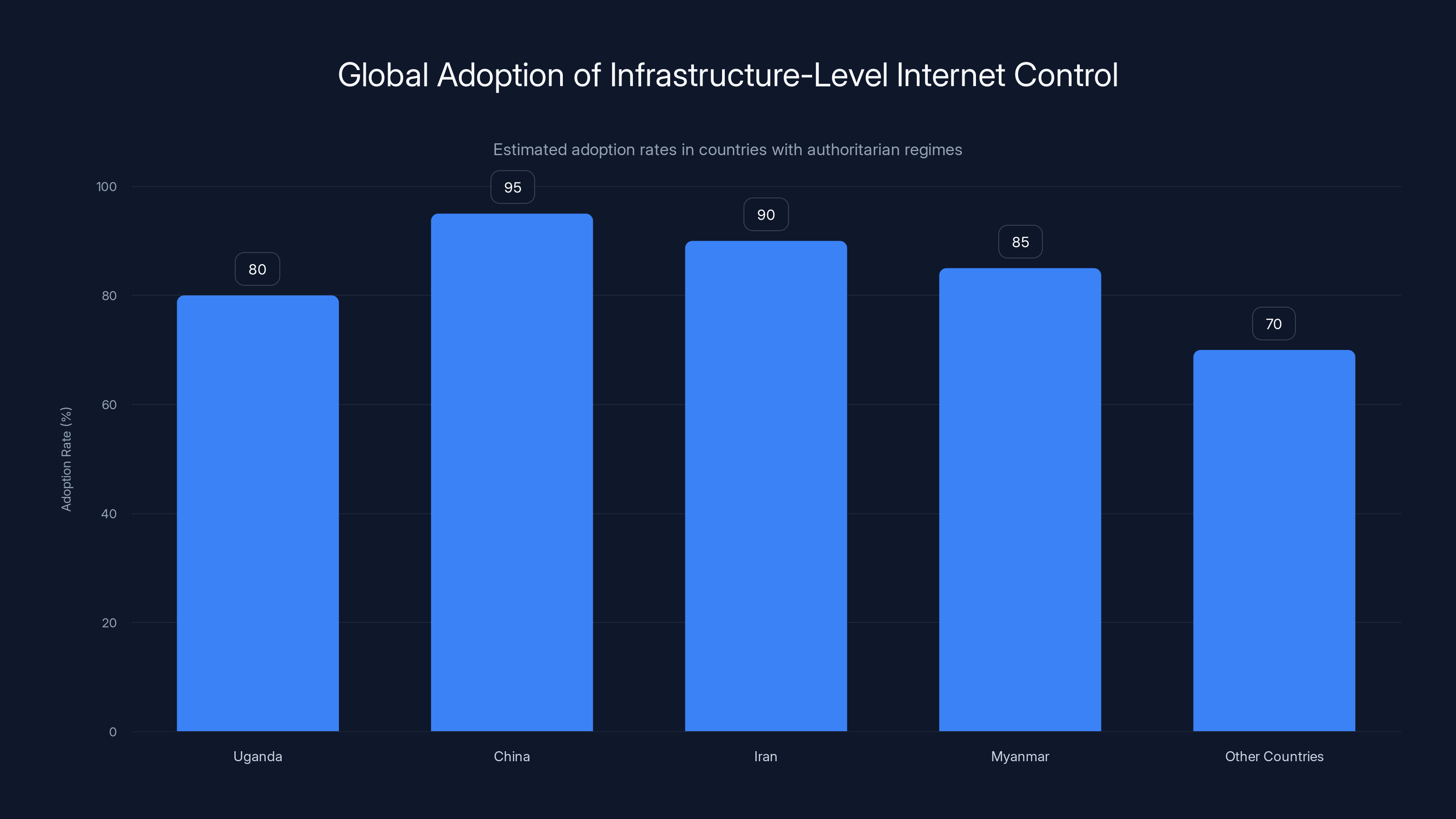

Estimated data shows that countries like China and Iran have high adoption rates of infrastructure-level internet control, with Uganda following closely. This trend is growing among authoritarian regimes. (Estimated data)

The Immediate Impact on VPN Users

For people in Uganda who relied on VPNs, the impact was immediate and severe. Journalists who used VPNs to communicate with sources securely found themselves unable to do so. Activists organizing resistance couldn't use encrypted channels. Ordinary citizens trying to access blocked websites or communicate freely faced an impossible situation.

The first sign of trouble came from users reporting that their VPN connections kept dropping. This wasn't unusual—VPN connections drop all the time due to network issues. But the pattern was different. Users would connect, maintain the connection for a few seconds or minutes, then get dropped. Reconnecting would work briefly, then fail again.

As connectivity continued degrading, even these temporary connections became impossible. The VPN apps would hang on the connection screen, unable to establish a tunnel. Users tried different VPN services, thinking perhaps their provider's servers were specifically blocked. Those services failed too.

By the second day of the shutdown, people across Uganda were reporting that essentially no VPN service was functional. Whether they used Proton VPN, Nord VPN, Express VPN, or other providers, the results were the same: unable to connect or unable to maintain connections long enough to be useful.

For businesses, the impact was equally severe. International companies with offices in Uganda couldn't securely access their corporate networks. Remote workers found themselves unable to do their jobs. Banks and financial institutions struggled with service disruptions.

Why Workarounds Are So Limited

Digital rights experts and security researchers have emphasized that workarounds for Uganda's situation are extremely limited. This represents a fundamental shift in how internet suppression works.

When authorities block specific VPN services, people can find alternatives. When they block port 443 (the port used by most HTTPS traffic), people can route traffic through other ports. When they deploy DPI technology, users can employ obfuscation tools to disguise VPN traffic. These are cat-and-mouse games where users have offensive moves available.

But when the problem is bandwidth reduction at the international gateway level, the game changes completely. You can't obfuscate your way around insufficient physical bandwidth. You can't disguise reduced connectivity as something else. The bottleneck exists at the infrastructure level, before your data even reaches a VPN server.

The limited workarounds that do exist are largely ineffective under these conditions:

Low-bandwidth protocols: Some applications designed for extremely limited connectivity (like Telegram's bot mode or basic email clients) might function over severely degraded networks. However, these don't provide the security benefits of VPNs and are subject to monitoring.

Mesh networking: Apps like Briar can transmit data across peer-to-peer networks without relying on internet connectivity. However, mesh networks work best with dozens of connected devices and take hours to transmit data that normally transfers in seconds.

Satellite connectivity: Starlink and other satellite internet services theoretically bypass country-level internet controls. However, these services are expensive, require visible external hardware that governments can target, and have latency issues that make real-time communication difficult.

Proxy networks: Services that route traffic through residential proxies in other countries can sometimes work even during degraded connectivity. However, their effectiveness depends on the degree of bandwidth reduction and they're often blocked once governments identify them.

None of these represent true solutions. They're patches that work in specific scenarios but don't restore the basic ability to access the internet freely and securely.

The timeline shows an increasing trend in internet shutdowns in Uganda, peaking around election years. Estimated data based on documented incidents.

Comparing VPN Blocks vs. Infrastructure Attacks

To understand why Uganda's situation is so different from previous VPN blocks, let's compare the two approaches:

Traditional VPN Blocking (Pre-2025 approach):

- Authorities identify VPN server IP addresses

- ISPs block traffic to those addresses

- Users switch to different VPN providers or services

- Cat-and-mouse game continues indefinitely

Infrastructure-Level Control (2025 approach):

- Authorities reduce international bandwidth allocation

- All traffic—VPN and non-VPN—becomes slower

- Users can't meaningfully use any service requiring fast connections

- Workarounds become nearly impossible because the problem exists at the foundation layer

The infrastructure approach is more effective because it doesn't target specific technologies. It works against VPNs, regular internet access, everything. You can't obfuscate your way around insufficient bandwidth, and you can't block-evasion your way through a physical bottleneck.

| Factor | VPN-Specific Blocks | Infrastructure Throttling |

|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | Moderate (users find alternatives) | Extremely high (affects all services) |

| Easy to detect | Yes (specific services fail) | No (appears like technical issues) |

| Workarounds available | Yes (multiple options) | Extremely limited (no technical solutions) |

| Technical sophistication required | Medium (DPI systems) | High (coordination with ISPs) |

| International criticism | High (obviously deliberate) | Low (deniable as technical problems) |

| Cost to implement | Medium (infrastructure investment) | Low (configuration changes only) |

Digital Rights Organizations' Response

When Uganda's internet connectivity collapsed in 2025, digital rights organizations around the world issued urgent statements. Groups like Access Now, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch condemned the shutdown and called for immediate restoration of service.

Access Now, which maintains the world's most comprehensive database of internet shutdowns, classified Uganda's 2025 incident as one of the most severe infrastructure-based shutdowns they had documented. This classification was significant because it indicated the unprecedented nature of the approach taken.

Among their key findings:

- The shutdown affected approximately 40 million internet users across Uganda

- Economic losses were estimated at $10+ million per day in disrupted commerce and services

- Healthcare services relying on internet connectivity were negatively impacted

- Educational institutions couldn't access online resources or conduct distance learning

- Journalists reported complete inability to file stories or communicate with editors

Digital rights experts emphasized that this approach represents a new frontier in internet suppression. Rather than playing cat-and-mouse with VPN providers, authoritarian regimes can now simply constrain infrastructure to achieve similar or greater suppression effects.

Proton VPN and other providers released statements indicating they were exploring technical solutions but acknowledged the fundamental challenge: you can't tunnel through infrastructure that doesn't have capacity.

The international community's response was muted compared to previous shutdowns. Several factors contributed to this:

- The shutdown occurred during a busy news cycle with competing crises

- The infrastructure-based approach is harder to explain clearly to general audiences

- Uganda's government maintained plausible deniability by blaming technical issues

- Western governments had limited leverage to apply pressure

Estimated data shows a significant drop in internet connectivity in Uganda during the 2025 shutdown, with connectivity reducing from 100% to 20% over four weeks.

Technical Analysis: How Uganda's ISPs Implemented the Shutdown

Understanding the technical mechanism of Uganda's shutdown requires examining how internet connectivity actually works at the national level.

Uganda's internet connectivity to the rest of the world flows through several primary pathways:

Undersea fiber optic cables: Multiple cables connect Uganda to Europe and the Middle East, providing the highest-capacity international connections.

Terrestrial fiber connections: Land-based fiber optic lines connect Uganda to neighboring countries like Kenya and Tanzania.

Satellite connections: Various providers operate satellite links for redundancy and coverage.

International peering agreements: ISPs maintain connections with international carriers that allow traffic to flow between networks.

To implement the 2025 shutdown, Uganda's government appears to have instructed the primary ISPs (MTN Uganda, Airtel Uganda, and others) to reduce the bandwidth they were allocating to international traffic. This can be accomplished through configuration changes at the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) level and through physical network equipment modifications.

The genius of this approach is its invisibility. Unlike blocking specific websites or services, a bandwidth reduction doesn't trigger automated alerts at international internet monitoring organizations. It looks like a gradual degradation that could be caused by equipment failures, maintenance, or network congestion.

Once bandwidth is constrained at the international gateway, everything slows down proportionally:

- VPN connections that normally establish in 2-3 seconds take 30+ seconds or fail

- Video streaming becomes impossible

- Large file transfers timeout

- Real-time applications like voice calling become unreliable

- Even basic browsing becomes frustrating

Users experience this as "the internet is slow" rather than "the internet is blocked." This distinction is important politically, as it provides governments with plausible deniability. They can claim technical difficulties rather than admitting to deliberate suppression.

The Role of Telecommunications Companies

Uganda's major telecommunications companies—MTN Uganda, Airtel Uganda, and others—found themselves in an impossible position.

Government pressure to implement the shutdown would have been intense. In Uganda, where the government exercises significant control over the telecommunications sector, ISPs face real consequences for non-compliance with official directives. Refusing to reduce international bandwidth could result in regulatory penalties, business license threats, or other pressures.

However, implementing the shutdown also damages ISPs. Reduced international connectivity drives away customers, harms business productivity, and damages their reputation. ISPs face a lose-lose situation: comply with government demands and alienate customers, or refuse and face government retaliation.

Some reports suggested that ISPs initially resisted or delayed implementation, but ultimately complied when government pressure intensified. The telecommunications companies made public statements claiming technical difficulties were responsible, which was technically true (reduced bandwidth is a technical issue) while being deliberately misleading about the cause.

This dynamic reveals a crucial challenge in addressing internet shutdowns: the companies operating the physical infrastructure often have limited choice in whether to participate. Unlike software companies that can refuse to create blocking systems, ISPs operating in authoritarian countries face direct government control over their business licenses and operations.

Estimated data shows significant degradation in service performance during Uganda's internet shutdown, with VPN connections taking ten times longer and video streaming becoming impossible.

Impact on Different User Groups

The shutdown affected different populations in distinct ways:

Journalists and Media: News organizations were severely impacted. Reporters couldn't file stories, news websites couldn't load, and international media couldn't broadcast from Uganda. This created an information vacuum that the government potentially filled with its own narrative.

Activists and Political Opponents: Activists lost the ability to organize, coordinate, and document abuses. VPNs that provided protection from surveillance became worthless. Communication channels went dark, disrupting organizing efforts.

Healthcare Providers: Hospitals and clinics relying on internet connectivity for patient records, telemedicine, and supply chain management faced serious disruptions. Medical staff couldn't access important information, potentially affecting patient care quality.

Students and Educators: Educational institutions couldn't maintain online learning platforms. Students relying on internet access for homework or distance education were cut off. This was particularly damaging during ongoing semesters.

Business and Commerce: International companies couldn't access corporate networks. E-commerce operations shut down. Remittances from diaspora Ugandans became difficult to transmit. The economic impact was severe.

Ordinary Citizens: Regular people simply trying to communicate with friends and family, access information, or use basic internet services found themselves unable to do so. The shutdown affected nearly 45% of Uganda's population with internet access.

Comparing Uganda's Shutdown to Global Internet Control Trends

Uganda's 2025 shutdown isn't an isolated incident. It's part of a broader global trend toward more sophisticated internet control.

Countries like China, Iran, and Russia have been refining infrastructure-level internet control for years. China's "Great Firewall" uses DPI at massive scale, but it also incorporates bandwidth management strategies. When the government wants to suppress information flow during sensitive periods, reducing the capacity for video streaming or other bandwidth-intensive services effectively limits people's ability to access certain types of content.

Myanmar's shutdowns in 2021 involved complete blackouts but also used infrastructure-level control mechanisms to prevent VPNs from functioning effectively.

Sudan's shutdowns during civil unrest employed infrastructure degradation alongside service-specific blocking.

The trend is clear: authoritarian governments are moving up the technology stack. Rather than blocking specific websites or services, they're implementing controls at the infrastructure layer where workarounds become much more difficult.

This represents a concerning evolution in digital authoritarianism. It's more effective, harder to detect, and more deniable than previous approaches. It also represents something closer to an information siege than a simple content filter.

| Country | Approach | Effectiveness | Deniability |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | Layered (DNS, DPI, infrastructure) | Very high | Medium (obvious censorship) |

| Iran | DPI + bandwidth management | High | Low (overt blocking) |

| Myanmar | Infrastructure throttling + blocking | High | Medium (blamed on technical issues) |

| Uganda 2025 | Bandwidth reduction | Very high | High (indistinguishable from technical problems) |

| Russia | Mixed (blocking + DPI + throttling) | High | Medium (obvious during crises) |

What Actually Still Works: Limited Workaround Options

While digital rights experts confirm that traditional workarounds don't function during infrastructure-level shutdowns, a few limited options deserve discussion.

Mesh Networking Applications

Applications like Briar don't rely on the internet at all. Instead, they create peer-to-peer networks that pass messages from device to device. If you're in range of someone with the app installed, you can send them messages that propagate through the network.

The challenge: Briar requires multiple devices in proximity with the app installed. Building a functional mesh network takes weeks of preparation, not something most people have done before a crisis hits. Additionally, message propagation is extremely slow (hours or days for important communications), and the network is extremely fragile (removing key nodes breaks connectivity).

Satellite Communications

Starlink and other satellite services theoretically provide internet access independent of terrestrial infrastructure. However:

- Equipment is expensive ($600+ startup cost)

- Installation requires visible external hardware that governments can target

- Governments can jam satellite signals with the right equipment

- Latency makes real-time communication difficult

- Service can be discontinued by the provider under government pressure

Low-Bandwidth Alternatives

Applications designed for extremely limited bandwidth can still function:

- Basic email clients using plain text

- Telegram's bot functionality with compressed mode

- Ultra-lightweight messaging apps

- Text-only versions of websites

These allow some communication but provide no security benefits and are all subject to monitoring.

Pre-positioned Information

The most effective "workaround" is advance preparation. Before shutdowns occur, people who anticipate them can:

- Download important information to devices

- Pre-load offline maps and reference materials

- Stock up on pre-arranged communication codes

- Establish offline meeting points

This doesn't solve the problem but makes functioning during shutdowns somewhat easier.

The Economics of Internet Shutdowns

Uganda's 2025 shutdown came with enormous economic costs, though the government likely calculated these as acceptable compared to the perceived political benefits.

Direct economic losses from the shutdown included:

Business disruption: E-commerce platforms couldn't operate. International transactions halted. Exports couldn't be coordinated. Estimates suggest $100+ million in lost economic activity.

Productivity losses: Workers unable to access cloud services, email, or remote work platforms. Knowledge workers entirely unable to perform jobs. Estimated at $5-10 million per day.

Healthcare impact: Limited ability to coordinate patient care, access medical information, or conduct telemedicine. While hard to quantify, medical professionals reported serious challenges.

Educational disruption: Universities and schools couldn't conduct online learning. Students and teachers lost months of instruction in some cases.

Agricultural impact: Modern agriculture relies heavily on weather information, market data, and supply chain coordination. Farmers couldn't access critical information.

Total economic impact from the shutdown likely exceeded $500 million for the days it lasted, making it one of the most economically destructive shutdowns in African history.

For context, this cost was borne almost entirely by ordinary Ugandans rather than government officials or the military, who presumably maintained access to alternative communication methods.

How Users Can Prepare for Future Shutdowns

While Uganda's 2025 shutdown highlighted the limitations of traditional workarounds, preparation can still help people maintain some functionality during future shutdowns.

Before a shutdown occurs:

- Download offline content: Save important documents, reference materials, maps, and medical information to your device

- Use offline apps: Install applications that work without internet (offline maps, offline dictionaries, offline translation apps)

- Create backups: Ensure important data is backed up to external drives or cloud services before restrictions begin

- Establish alternative contact methods: Agree on in-person meeting locations, phone numbers to call when needed, or trusted intermediaries

- Learn mesh networking: If possible, set up Briar or similar apps with trusted contacts in advance

- Consider satellite options: For critical operations, evaluate whether Starlink or similar services are viable options

- Document everything: Set up systems to record events, abuses, or important developments that might occur during restrictions

During a shutdown:

- Minimize data usage: Use only essential internet when connectivity briefly returns

- Verify information carefully: Misinformation spreads rapidly during shutdowns when people can't access reliable sources

- Document disruption impact: Record how the shutdown affects your business, health, education, or community

- Use offline-first tools: Shift to apps that work on local networks or don't require internet

- Establish local information networks: Share information through trusted in-person channels

After a shutdown ends:

- Back up evidence: Document impacts while they're fresh

- Support transparency efforts: Contribute to reports documenting the shutdown's impact

- Prepare for future shutdowns: Use lessons learned to improve future preparations

- Help others document impacts: Support journalists and researchers documenting shutdown effects

Policy Implications and International Response

Uganda's 2025 shutdown has significant implications for international policy around digital rights and internet freedom.

National level: Countries need to establish laws protecting internet access as a fundamental right and penalizing both government officials and telecommunications companies that participate in unjustified shutdowns.

Regional level: African Union and regional organizations should develop stronger standards and enforcement mechanisms around digital rights.

International level: The United Nations and international organizations need mechanisms to respond to shutdowns more quickly and effectively. Current responses often come too late to matter.

Technical level: VPN providers and internet infrastructure companies should develop better monitoring and documentation systems to detect infrastructure-level attacks earlier.

Corporate level: International technology companies should consider how they can support digital rights without directly supporting authoritarian governments.

The challenge is that Uganda's approach—reducing international bandwidth—is harder to address through traditional policy mechanisms. You can't pressure a company to "stop using this blocking technology" when the blockage is simply reduced capacity.

Instead, solutions might include:

- Incentivizing telecommunications companies to maintain connectivity even under government pressure

- Developing redundant international connectivity pathways that are harder to collectively restrict

- Creating international agreements protecting internet infrastructure from deliberate degradation

- Building satellite and alternative network infrastructure that doesn't depend on traditional telecommunications companies

The Future of VPN Technology and Internet Control

Uganda's 2025 shutdown suggests that the future of internet control will increasingly move beyond VPN blocking toward infrastructure-level management.

This creates both challenges and potential future solutions:

VPN providers' response: The major VPN providers are exploring several approaches:

- Obfuscation improvements: Making VPN traffic even harder to detect, which works until bandwidth is constrained

- Alternative protocols: Developing new protocols that might function better under degraded network conditions

- Redundancy systems: Creating backup connectivity options through satellite, mesh networks, or other alternative paths

- Documentation and monitoring: Better tools to detect and document infrastructure-level attacks

Longer-term solutions: Researchers are exploring:

- Decentralized internet architecture: Systems not dependent on centralized infrastructure that can be shut down

- Satellite internet advancement: Improving Starlink and similar services to reduce latency and cost

- Community mesh networks: Building mesh networking infrastructure that can function independently of centralized ISPs

- Censorship-resistant protocols: New internet protocols that might inherently resist centralized control

However, these represent long-term solutions measured in years or decades. In the short term, infrastructure-level control represents an effective tool for suppression that authorities around the world are likely to adopt.

FAQ

What caused Uganda's VPN services to stop working in 2025?

Uganda's VPN services stopped working due to drastically reduced international internet bandwidth rather than VPN-specific blocking. The government appears to have instructed telecommunications companies to reduce the capacity of international connections, creating a bottleneck that affects all internet traffic, not just VPNs. This infrastructure-level approach is more effective than traditional blocking because it doesn't target specific technologies.

Why are workarounds so limited during infrastructure-level shutdowns?

Workarounds work by routing traffic through different pathways or disguising traffic to evade detection. However, when the fundamental problem is insufficient bandwidth at the international gateway, no pathway has adequate capacity and no disguise can create bandwidth that doesn't exist. Mesh networks, satellite, and other alternatives exist but have significant limitations in terms of cost, speed, functionality, and availability. They represent partial solutions rather than true workarounds.

Is this approach unique to Uganda or a global trend?

While Uganda was among the first to implement a complete infrastructure-level shutdown, the approach builds on techniques used in China, Iran, Myanmar, and other countries. Infrastructure-level control is increasingly attractive to authoritarian governments because it's more effective than traditional blocking, harder to detect and verify, and provides plausible deniability through claims of technical difficulties. The trend toward infrastructure-level control is likely to continue globally.

Can VPN providers do anything to work around infrastructure-level shutdowns?

VPN providers have limited options against infrastructure-level shutdowns. Obfuscation, protocol improvements, and other technical solutions can help during DPI-based blocking but don't solve insufficient bandwidth. Some providers are exploring alternative connectivity pathways like satellite or mesh networks, but these have significant practical limitations. The fundamental issue is technical: you cannot reliably transmit data through a connection that lacks sufficient capacity.

How can individuals and organizations prepare for future shutdowns?

Preparation involves multiple approaches: downloading offline content before shutdowns occur, establishing alternative communication methods with contacts, setting up mesh networking applications in advance, evaluating satellite internet options for critical operations, and creating backup systems for important data. The most effective preparation is anticipatory, done before restrictions begin. Once a shutdown occurs, options become much more limited.

What are the economic impacts of internet shutdowns like Uganda's?

Large-scale shutdowns have massive economic consequences including business disruption (hundreds of millions in lost transactions), productivity losses (millions per day), healthcare disruption (difficult to quantify but serious), educational losses, and agricultural impacts. Uganda's 2025 shutdown likely cost the economy over $500 million during the days it lasted, making it one of the most economically destructive shutdowns in African history.

Why haven't international organizations done more to prevent shutdowns?

International response to shutdowns faces multiple challenges. Infrastructure-level shutdowns are harder to prove and justify in international forums (governments can claim technical issues). Authoritarian governments have limited fear of international consequences, as enforcement mechanisms are weak. The companies implementing shutdowns (ISPs) often have limited choice due to government control. International organizations lack rapid-response mechanisms and adequate resources to address shutdowns as they occur.

Could satellite internet like Starlink solve the shutdown problem?

Satellite internet could theoretically bypass terrestrial infrastructure shutdowns, but significant practical barriers exist. Equipment is expensive, requires visible external hardware, can be jammed, experiences high latency unsuitable for real-time communication, and providers can be pressured to discontinue service. Satellite is useful as part of a broader strategy but doesn't solve shutdowns comprehensively.

What can governments do to prevent shutdowns in their own countries?

Governments can establish laws protecting internet access as a fundamental right, criminalize unjustified shutdowns, establish regulatory frameworks requiring transparency, mandate maintaining of minimum connectivity standards even during emergencies, establish independent oversight boards for telecommunications infrastructure, and create international agreements protecting internet infrastructure from deliberate degradation. However, these protections are most effective in democracies with strong institutions; authoritarian governments may simply ignore them.

How does Uganda's approach differ from the simple blocking of VPN providers?

VPN-specific blocking targets particular services or protocols; users can often find alternative VPN providers or obfuscation techniques to work around blocks. Infrastructure-level control targets the underlying bandwidth itself; no alternative pathway has adequate capacity if the international gateway is constrained. This makes infrastructure-level control far more effective and harder to work around because it's not about identifying and blocking specific traffic, but reducing the total capacity available for all traffic.

Conclusion: What Uganda's Shutdown Tells Us About the Future

Uganda's 2025 internet shutdown represents a watershed moment in the evolution of internet control. It demonstrates that the future of digital suppression may not involve sophisticated blocking technologies but rather a simpler, more effective approach: reducing the international bandwidth available to an entire nation.

This shift has profound implications for digital rights, internet freedom, and how activists, journalists, and ordinary citizens can respond to suppression. Traditional tools like VPNs become almost worthless when the underlying infrastructure can't support them. Workarounds that previously worked become ineffective. The asymmetry between those controlling the infrastructure and those trying to access information becomes starker.

For individuals in Uganda, the shutdown was a catastrophe. Journalists couldn't report, activists couldn't organize, students couldn't learn, businesses couldn't operate, and healthcare providers couldn't access critical information. For millions of ordinary people, it was simply a digital blackout during a politically sensitive period.

For digital rights advocates, Uganda's shutdown should serve as a wake-up call. The strategies and tools that worked against previous shutdowns are becoming obsolete. New approaches are needed, which might include building alternative infrastructure, investing in satellite and mesh networking technologies, establishing legal protections for internet access, and finding ways to make infrastructure control more politically costly for governments.

For international organizations and governments concerned with digital rights, Uganda's shutdown should catalyze faster, stronger responses. Current mechanisms are too slow and too weak to address rapid infrastructure-level shutdowns.

For telecommunications companies operating in authoritarian countries, Uganda's shutdown highlights the impossible position they occupy. They face pressure from governments to implement shutdowns and pressure from users and international organizations to resist. Without stronger international support and legal frameworks, many will continue to choose government compliance.

The broader story is about power and control. Authoritarian governments are learning that they don't need sophisticated technology to suppress information flow. They control the physical infrastructure that connects their countries to the internet. Using that control—by simply reducing international bandwidth—they can achieve suppression effects that previously required complex blocking technologies.

This approach is spreading. Other countries are watching Uganda's example and noting its effectiveness. As internet control becomes infrastructure control, defending digital freedom becomes exponentially harder.

Yet hope remains. The global digital rights community is responding. Alternative technologies are being developed. International pressure is building. Telecommunications companies are increasingly recognizing the risks of participating in shutdowns.

The question facing the world is whether infrastructure-level internet control can be stopped, regulated, or made politically costly enough that governments think twice before implementing it. Uganda's 2025 shutdown was one data point in that ongoing struggle.

What happens next depends on the choices made by policymakers, technology companies, digital rights organizations, and ordinary people worldwide. The infrastructure that connects nations is increasingly becoming the frontier of digital freedom. How that frontier develops will shape internet freedom for billions of people.

Key Takeaways

- VPNs stopped working in Uganda due to infrastructure-level bandwidth throttling, not service-specific blocking, making traditional workarounds ineffective

- Infrastructure-level control represents a new frontier in internet suppression that's harder to detect, easier to implement, and more difficult to work around than previous blocking methods

- Digital rights experts confirmed that options for circumventing bandwidth reduction are extremely limited, with no technical solutions matching the problem's scale

- Uganda's shutdown cost over $500 million economically and demonstrated the real-world impact of internet infrastructure being used as a suppression tool

- This approach is spreading globally as authoritarian governments recognize it's more effective than sophisticated blocking technologies while providing plausible deniability

Related Articles

- Discord Blocked in Egypt: Why VPN Usage Spiked 103% [2025]

- Internet Censorship Hit Half the World in 2025: What It Means [2026]

- Iran Internet Blackout: What Happened & Why It Matters [2025]

- Wikipedia's Existential Crisis: AI, Politics, and Dwindling Volunteers [2025]

- ExpressVPN 78% Discount Deal: Complete Savings & Comparison Guide [2025]

- Why Grok's Image Generation Problem Demands Immediate Action [2025]

![VPN Uganda Internet Shutdown: What Happened & Workarounds [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/vpn-uganda-internet-shutdown-what-happened-workarounds-2025/image-1-1768484334916.jpg)