Iran's Historic Internet Blackout: Understanding the Digital Shutdown

On a Thursday morning in 2024, something extraordinary happened. Ninety million people woke up to find their phones stopped working, their emails wouldn't load, and their social media feeds vanished. Not because of a technical glitch or a cyber attack from some foreign power, but because their own government flipped a switch.

This wasn't the first time Iran had cut off internet access. But this blackout was different. It lasted over 90 hours straight—nearly four full days. For context, that's longer than most people go without sleep before hallucinating. It's long enough that people forget what they were angry about, then remember again, then wonder if they imagined the whole thing.

What makes this blackout so significant isn't just the duration or the scale. It's what it reveals about how governments can weaponize connectivity itself. In 2025, when we talk about digital rights, internet freedom, and surveillance, we can't ignore what happened in Iran. This wasn't theoretical. It wasn't a hypothetical scenario discussed in a tech conference. It was real people, real consequences, and a real demonstration of state power over digital infrastructure.

The blackout came at a critical moment. Iran was experiencing widespread protests, and the government faced a choice: allow people to organize, document abuses, and share their stories with the world, or cut them off completely. They chose the latter. The decision reveals uncomfortable truths about how fragile internet access really is, how concentrated power over connectivity has become, and what happens when governments decide that information control matters more than anything else.

This article breaks down everything you need to understand about the Iran blackout, why it happened, how authorities pulled it off, and what the implications are for digital freedom globally. We're talking technical details, political context, human impact, and what experts predict comes next.

TL; DR

- 90+ hour blackout affected 90 million people in Iran during protest movement, with nearly complete internet shutdown

- Government demonstrated unprecedented control over digital infrastructure by severing connections at multiple network chokepoints simultaneously

- Internet censorship and blackouts are escalating as a control mechanism, with Iran using this as a blueprint for future digital suppression

- VPNs and privacy tools become critical during shutdowns, but even these have limitations when governments block VPN protocols directly

- Global implications are serious as other authoritarian regimes study Iran's methods and consider similar digital lockdowns

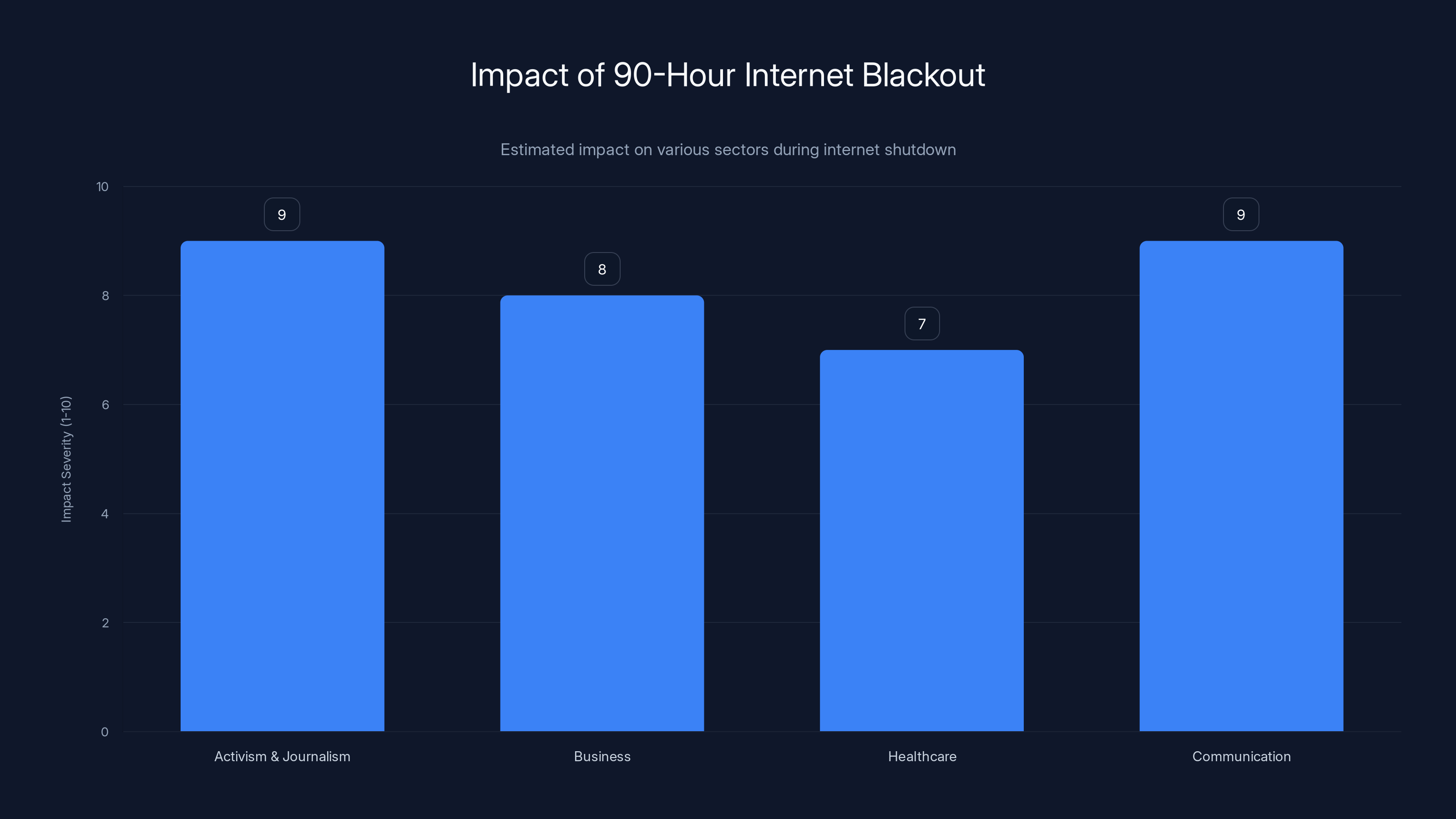

The 90-hour internet blackout severely impacted activism, journalism, business operations, healthcare, and personal communication. Estimated data.

What Actually Happened: Timeline of the Blackout

Understanding the blackout requires knowing exactly when it started, how it unfolded, and what people experienced minute by minute.

Thursday morning arrived like any other day in Iran. Commuters were checking their phones on the subway. Students were opening social media between classes. Activists were coordinating online. Then, systematically, everything stopped.

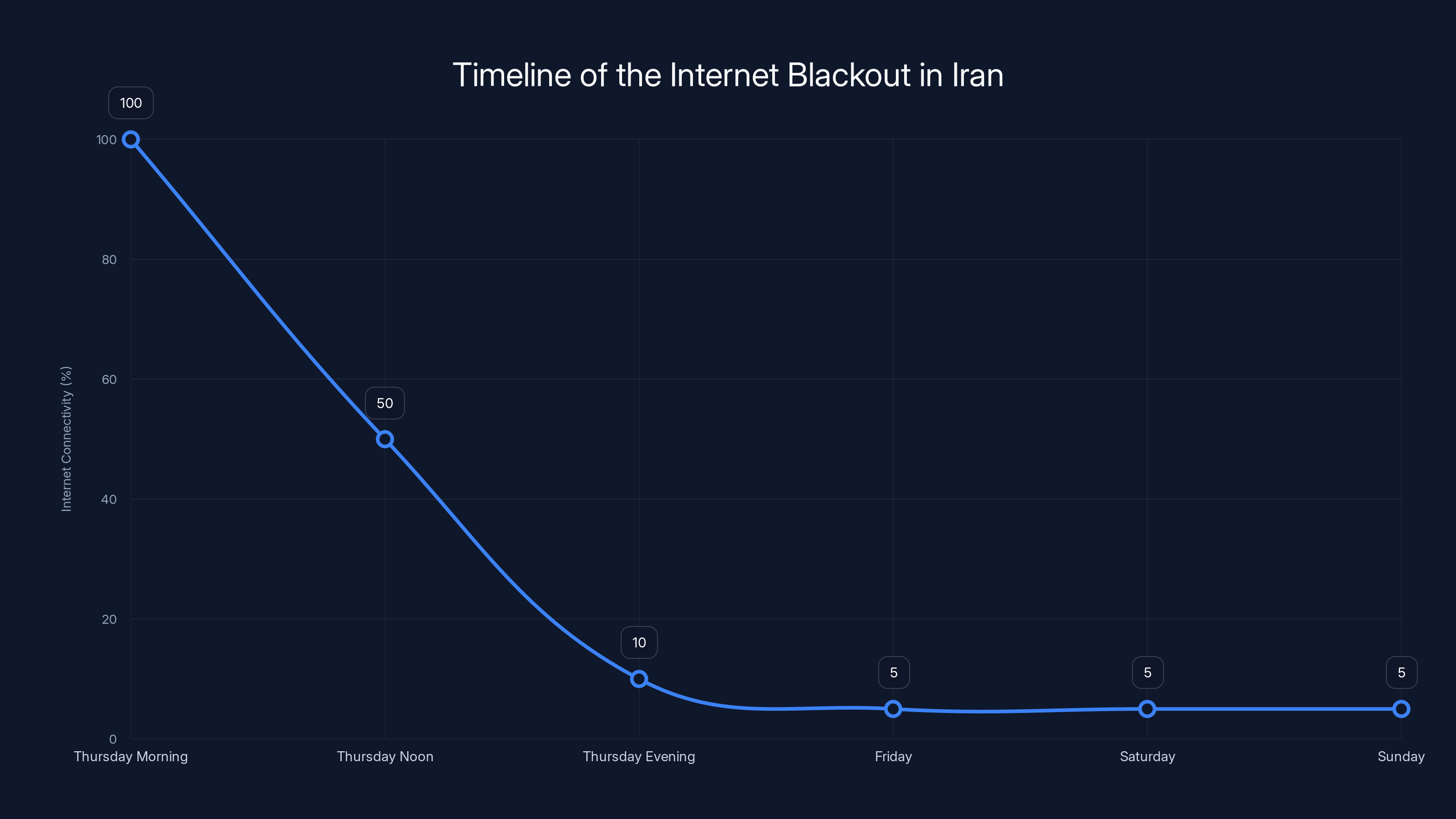

The shutdown didn't happen all at once across the entire country. That would be chaotic and might trigger international alarm faster. Instead, it rolled out in waves. Internet speeds dropped first. Pages that normally loaded in two seconds took thirty. Then they timed out completely. Mobile data slowed to dial-up speeds—so slow that even a text message felt revolutionary.

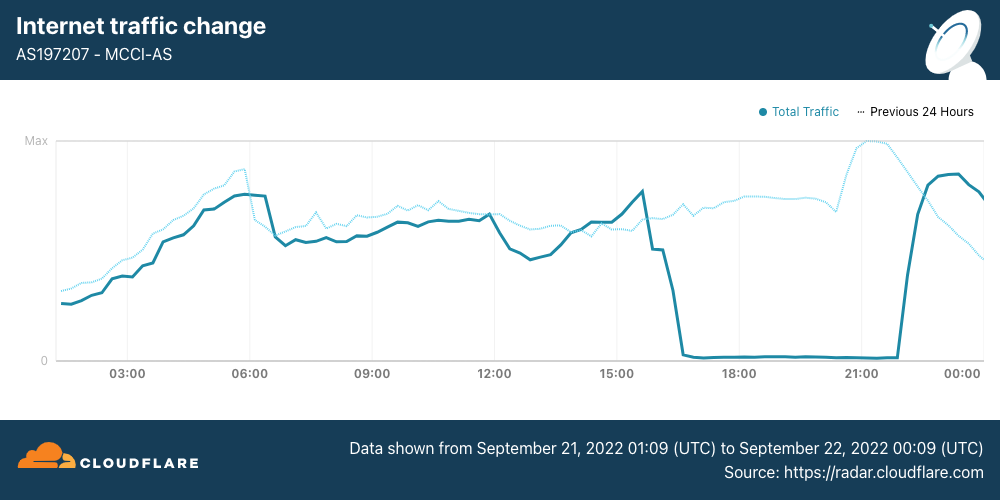

Within hours, major internet service providers across the country reported that their international gateway traffic had been throttled dramatically. Then cut entirely. By mid-morning Thursday, the situation was clear: Iran's government had taken action. The scope became apparent as the day went on. Not just one provider. Not just certain regions. The entire country.

By Thursday afternoon, international monitoring services confirmed what Iranians already knew: their country had essentially vanished from the internet. Companies that track global connectivity in real-time reported that Iran's internet traffic had dropped by over 90%. Not 50%. Not 70%. Ninety percent.

The 90+ hours that followed represented an information vacuum. No one could call their family outside Iran. Journalists couldn't file reports. Activists couldn't coordinate. International media had to rely on satellite phones and VPNs if they could get them working at all. Even video calls were completely impossible. The world was watching, but Iranians were in the dark.

Friday came and went. Internet remained down. Saturday. Still down. Sunday rolled around, and people started adapting. They learned to navigate without digital tools. Face-to-face conversations became the only way to share information. Rumors spread faster than facts. And the government maintained control through the most effective tool available: silence.

By Monday morning, five days after the blackout began, the government started carefully restoring access. Not all at once. Again, in waves. Some services came back. Then more. Then social media. The restoration took almost as long as the shutdown itself, suggesting the government was being deliberate about which services to restore first.

Internet connectivity in Iran dropped dramatically from 100% to below 10% by Thursday evening, remaining low over the following days. (Estimated data)

Why the Blackout Happened: The Political Context

Internet blackouts don't happen by accident, and they don't happen for technical reasons. They happen because someone decides that controlling information is more important than allowing people to communicate.

In Iran's case, the trigger was straightforward. Massive protests had erupted over a specific incident that had outraged the nation. The government faced a dilemma every authoritarian regime encounters: let the protests grow and spread with the help of social media and internet coordination, or shut it all down.

Historically, connectivity amplifies dissent. When people can document injustice with their phones and share it instantly with millions, movements gain momentum that offline organization simply cannot match. A protest that stays local stays manageable. A protest that goes viral becomes a political crisis. Iran's government had seen what happened in 2009 during the Green Movement, when internet and mobile phones enabled coordination despite heavy-handed government tactics. They understood the power of digital tools in organizing opposition.

So when faced with this new wave of protests, they made a calculation. The short-term pain of a blackout—international criticism, economic costs, logistical nightmare—was worth the benefit of stopping information from spreading. Controlling the narrative becomes easier when there is no competing narrative. Evidence of government abuses becomes impossible to share when no one can access the internet.

This decision wasn't made in isolation. It reflected a broader strategy that Iran had been developing for years. The government had been investing in what's called "digital sovereignty," which essentially means building infrastructure and capabilities to operate completely independently from the global internet. They'd been planning for this scenario—the ability to fully control or shut down connectivity if needed.

The blackout was also a test. By implementing it and observing what happened, Iran's government learned valuable information about what's possible, what people accept, and what the international response looks like. The United States condemned it. Europe issued statements. International human rights organizations published reports. But there were no significant consequences. No sanctions specifically targeting the blackout. No military intervention. Just words.

For other authoritarian governments watching, this was educational. If Iran could implement a 90+ hour blackout and face only diplomatic criticism, what was stopping them from doing the same? The precedent had been set.

How Governments Shut Down the Internet: Technical Mechanisms

This is where it gets technical, and understanding the mechanism is crucial because it reveals both how fragile internet access is and where governments have concentrated power.

The internet isn't one big network. It's thousands of networks connected together. For internet data to flow into and out of Iran, it has to pass through specific physical locations called "internet exchange points" or "international gateways." Think of them like border checkpoints. All traffic going in or out must pass through these chokepoints.

Iran only has a handful of these international gateways. That's unusual—most countries have many more, distributed across different regions and providers. The concentration exists partly for historical reasons and partly because the Iranian government deliberately consolidated control over time. Fewer gateways means easier control.

To shut down the internet, the government doesn't need to destroy anything. It doesn't need to physically cut cables (though those are vulnerable too). It just needs to tell the companies that operate these gateways to stop routing traffic through them. When those orders come from the government, companies comply. Refusing means penalties, criminal charges, or losing your license to operate entirely.

But it's not just about the international gateways. The government also needs to control domestic internet traffic. Within Iran's borders, there are several major internet service providers. These companies own the infrastructure that connects ordinary people's homes and phones to the broader internet. When the government tells them to restrict access, they implement it through their network systems.

The technical implementation involves something called "BGP," or Border Gateway Protocol. It's the system that routes internet traffic around the world. When Iran wanted to blackout the internet, network administrators essentially removed Iran's internet routes from the global routing tables. Other routers worldwide were told, "If you get traffic destined for an Iranian IP address, you don't know how to reach it anymore." The traffic either gets dropped or never leaves the source in the first place.

It's like someone removing a city from all the maps in the world. If no one can see how to get there on their navigation system, they stop trying to reach it. The city doesn't disappear physically, but it becomes invisible from the outside.

The government also had to handle VPNs and proxy services, which would normally allow people to bypass censorship by routing their traffic through servers outside Iran. How do you stop VPNs? Several ways. You can block the IP addresses of known VPN providers at the gateway level. You can deep packet inspect traffic to identify VPN protocols and filter them. You can require VPN providers to register with the government and then pressure them to turn over user data or shut down. Iran used combinations of these techniques.

The result was a internet infrastructure under complete government control. The beauty of this approach, from an authoritarian government's perspective, is that it's hard to circumvent. You can't just use a different ISP because there are only a few major ones. You can't route around the international gateways because the government controls those. You can't use underground networks because everyone would need access to specialized equipment and knowledge.

What Iran demonstrated was this: if a government has control over the infrastructure and isn't afraid of international consequences, they can essentially shut down internet access for everyone. The technical barriers are lower than most people realize.

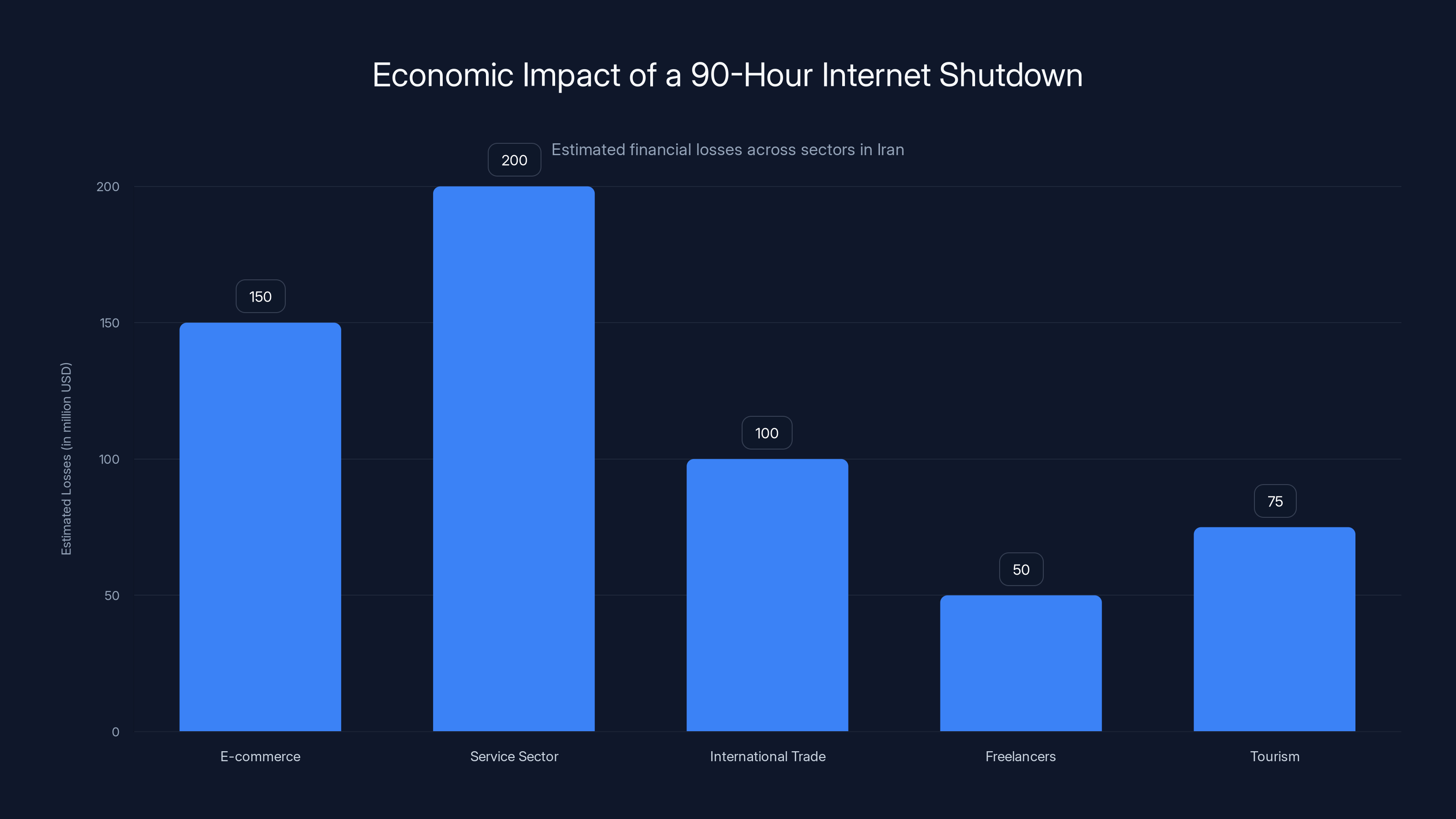

The 90-hour internet shutdown in Iran caused significant economic losses across various sectors, with the service sector facing the highest estimated losses. Estimated data.

The Human Impact: What 90 Hours Without Internet Really Means

Statistics about internet shutdowns are easy to understand abstractly. Ninety million people. Ninety hours. It sounds like data. But the human reality is far more complex and far more painful.

For activists and journalists, the blackout was catastrophic. Plans couldn't be coordinated. Evidence of government violence couldn't be documented or shared. International media outlets that relied on citizen journalists suddenly had no sources. The narrative became whatever the government said it was, because no one could contradict it with video evidence or firsthand accounts.

Consider the practical details. A young woman in Tehran wanted to tell her family in the United States that she was safe. No email. No Whats App. No Telegram. Nothing. She had no way to contact them except to find someone with a working satellite phone, which almost no one had. Her family had no way to verify she was okay. For five days, they had no information. That's the emotional weight of a blackout.

Businesspeople faced enormous losses. A company that relied on cloud services, international payments, or digital commerce couldn't operate. Websites went offline, not because of any technical failure, but because the entire country was disconnected. Imagine running a business and suddenly having no way to access your data, communicate with international partners, or process transactions. The blackout lasted long enough to disrupt everything but not long enough to allow people to establish offline workarounds.

Medical services were affected. Hospitals that used digital records systems had to switch to paper. Pharmacies that managed inventory through digital systems couldn't access their data. Patients who needed medications couldn't be contacted if their prescriptions needed adjustments. The healthcare impact of a internet blackout is rarely discussed, but it's significant.

For ordinary people, the blackout meant losing access to information. News sources were unreachable. Weather forecasts were unavailable. Maps didn't work. People couldn't check bank balances or access their money through digital services. The invisible infrastructure that modern life depends on was simply gone.

Socially, the blackout created a strange vacuum. Without internet, people turned to face-to-face conversation and rumor. Without verified information, misinformation filled the void. People heard stories that couldn't be confirmed or denied. Anxiety increased because no one knew what was really happening in the rest of the country or the world.

For people with disabilities that benefited from internet access—remote medical consultations, text-to-speech applications, remote work opportunities—the blackout was particularly devastating. These groups lost their lifelines to services and employment.

The psychological impact of an internet blackout is something that researchers are only beginning to study. People report feeling isolated, disconnected from reality, and anxious about what information they're missing. The blackout creates a form of enforced ignorance that people find deeply unsettling.

International Response and Condemnation

When Iran's internet went dark, the world noticed. And in 2025, when something happens, the international community has mechanisms to respond.

The United States immediately condemned the blackout, with officials calling it a violation of basic human rights. The State Department released statements emphasizing that access to information is a fundamental right and that internet shutdowns are tools of oppression. But words, even from the US government, are just words. They don't restore internet access.

The European Union issued a joint statement from multiple member countries expressing "grave concern" about the shutdown. Various EU nations highlighted their commitment to internet freedom and digital rights. Again, symbolic but not substantive in terms of immediate consequences.

International human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch documented the blackout and its effects. They published reports with specific details about its impact on journalists, activists, and ordinary people. These reports are important for the historical record and for building cases that might eventually lead to accountability, but in the immediate term, they don't help people reconnect to the internet.

Tech companies with operations or users in Iran faced difficult questions. Should they condemn the blackout publicly, knowing it might anger the Iranian government and result in further restrictions on their services? Should they stay silent and be accused of complicity? Different companies made different choices, reflecting the tension between business interests and human rights values.

The international response revealed something important: there are no effective enforcement mechanisms for internet freedom violations. The UN can't intervene. NATO can't militarily protect internet access. Sanctions can be imposed, but they're slow and often ineffective. A country determined to shut down its internet can do so without facing serious immediate consequences.

This is a gap in global governance that will likely become more important as internet blackouts become more common. If shutdowns are normalized because consequences are minimal, we should expect to see more of them. Countries will learn from Iran's example and implement their own blackouts when facing political unrest or when they want to suppress information.

Some countries are already considering it. During moments of political tension, officials in several nations have publicly discussed the possibility of internet shutdown as a tool for maintaining stability. Iran's successful implementation without major consequences makes this possibility feel real to these leaders.

The international response also highlighted a geopolitical dimension. Western democracies condemned the blackout because they generally support internet freedom and freedom of information. But some non-democratic states were notably quieter, perhaps seeing the blackout as a reasonable tool for governance rather than a violation.

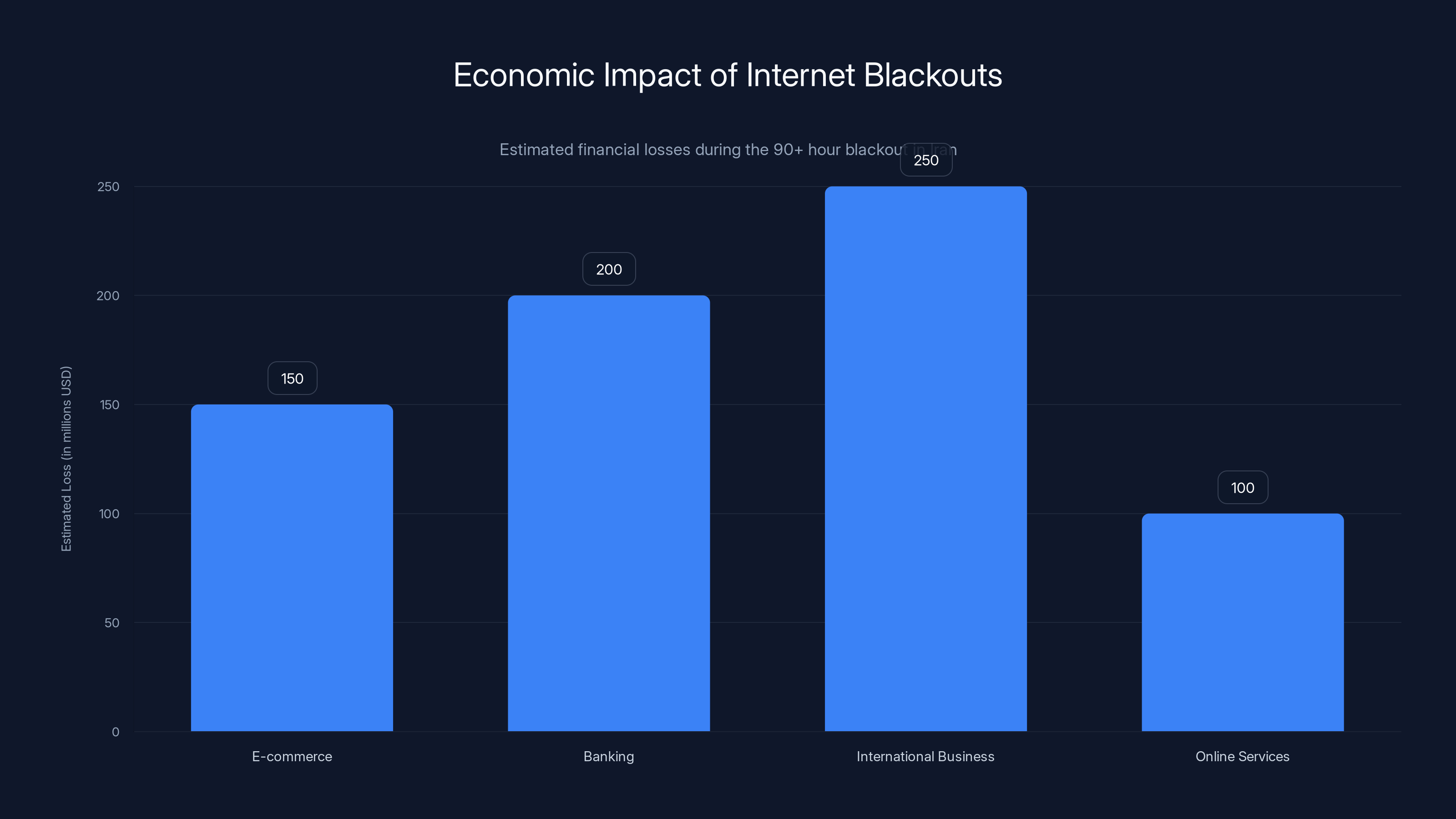

The 90+ hour internet blackout in Iran caused significant economic losses across various sectors, with international business facing the highest estimated loss. Estimated data.

VPNs, Proxies, and Bypassing Internet Censorship During Blackouts

When facing internet censorship, people often turn to VPNs and proxy services as solutions. During Iran's blackout, many people tried exactly this. But the reality of bypassing a government-level shutdown is more complicated than most people understand.

A VPN, or Virtual Private Network, encrypts your internet traffic and routes it through a server in another country. If Iran's government is trying to see what you're accessing, they see encrypted data going to a VPN server, not the actual content you're viewing. This is useful for normal internet censorship, where the government is trying to block specific websites or monitor what you're doing.

But a blackout is different. The government isn't trying to censor specific content or monitor specific people. They're trying to prevent all international internet traffic. If the international gateways are shut down, no traffic gets out at all, whether it's encrypted or not. You can run a VPN all you want, but if there's no path for your encrypted traffic to leave the country, the VPN is useless.

During Iran's blackout, VPNs essentially didn't work for most people. Not because they were broken or because the government specifically blocked them, but because there was nowhere for the traffic to go. The fundamental infrastructure was shut down.

There are workarounds. Tor, for instance, uses a more distributed network of nodes that makes blocking more difficult. But Tor is slower and requires more technical knowledge to set up correctly. During the blackout, some people with Tor expertise and access to the right equipment might have been able to maintain connectivity, but we're talking about maybe thousands of people out of ninety million.

Another option is satellite internet. Companies like Starlink provide connectivity that doesn't depend on terrestrial internet infrastructure. A person with satellite equipment could potentially maintain connectivity during a blackout. But satellite internet is expensive, requires physical equipment that most people don't own, and the Iranian government could theoretically jam the signals if they wanted to.

The practical reality is this: once a government shuts down the underlying internet infrastructure at the gateway level, individuals have very limited options for restoring connectivity. The solutions require either specialized technical knowledge, expensive equipment, or luck in finding a connection that wasn't shut down.

This is an important lesson for digital freedom advocates. VPNs and proxies are valuable tools for circumventing censorship of specific content, but they're not a solution to infrastructure-level shutdowns. To truly protect digital freedom, you need to prevent shutdowns from happening in the first place, not try to work around them after they've started.

Some privacy advocates have suggested that building distributed, mesh-based internet infrastructure would be more resilient to shutdowns. Instead of everyone depending on a few international gateways, imagine a network where data could route through many different paths. If one path is shut down, traffic finds another route. This is technically possible, but it would require massive infrastructure investment and would need to be in place before a shutdown occurs.

Precedent and Escalation: Iran's Blackout in Historical Context

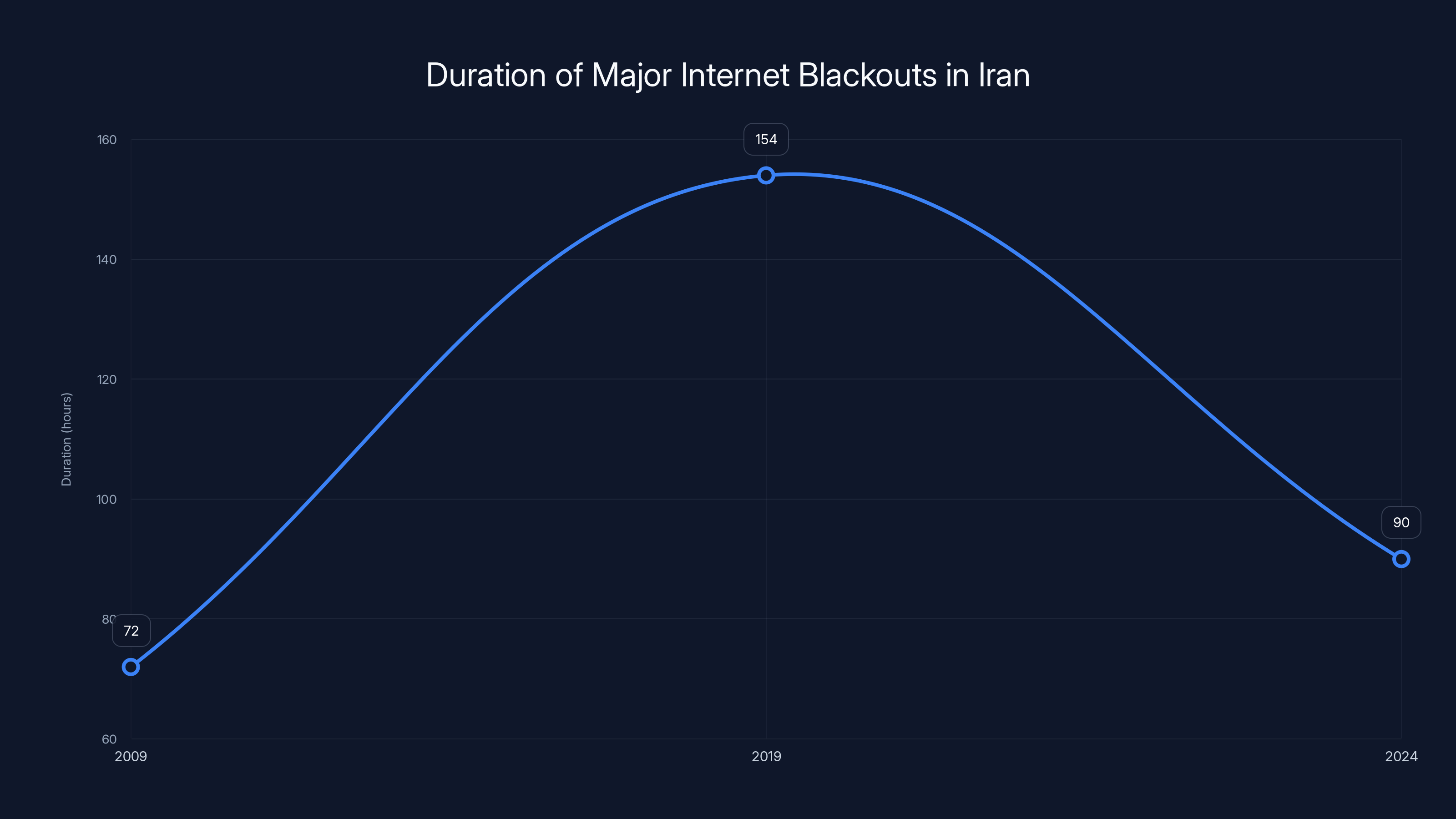

Iran's 90+ hour blackout wasn't unprecedented, but it was significant in terms of scale and duration. Understanding where this fits in the history of internet shutdowns reveals a troubling trend: they're becoming longer, more frequent, and more normalized.

The first major internet blackout in Iran occurred in 2009 during the Green Movement protests. The government shut down international internet connectivity for several days. At the time, this was shocking to the international community. It was seen as extreme, desperate even. But it worked. The blackout disrupted the protest movement's coordination and reduced global visibility of events.

Fast forward to 2019, during fuel price protests. The government implemented a blackout that lasted about 154 hours—longer than the 2024 event we're discussing. Again, the shutdown suppressed information flow and disrupted the movement. Again, the international response was condemnation without serious consequences.

Each time, the Iranian government refined its tactics. They learned what worked and what needed adjustment. By 2024, they had the infrastructure and experience to implement a blackout efficiently. The lessons learned from 2009 and 2019 made the 2024 blackout possible.

What's concerning is that other countries are clearly watching and learning. Several nations have either implemented or seriously considered internet shutdowns. Myanmar used blackouts during political crisis. Venezuela has implemented periodic internet restrictions. Sudan has shut down internet during conflicts. These aren't isolated incidents—they're part of a pattern.

The normalization of shutdowns is particularly worrisome because it represents a shift in how governments think about digital infrastructure. Instead of seeing the internet as something to regulate and monitor, they're treating it as something that can be simply turned off when it becomes inconvenient.

Internet shutdowns also reveal the concentration of power over digital infrastructure. A handful of companies and governments control the gateways and infrastructure that enable global connectivity. When these entities decide to shut down access, individuals and civil society have little recourse. This concentration of power is arguably more dangerous than any single government's policies.

The trend also connects to broader concerns about digital sovereignty and political control. Governments increasingly view digital infrastructure as strategic and critical. Just as they might take control of ports, airports, or power plants during national emergencies, they're now taking control of internet infrastructure. This framing makes shutdowns seem more justified within a national security context.

The duration of internet blackouts in Iran has varied, with the longest occurring in 2019. The trend indicates a strategic use of shutdowns over time.

Economic Consequences: The Real Cost of Going Dark

When ninety million people lose internet access for over ninety hours, the economic damage is significant. But it's often overlooked in discussions that focus on political implications.

E-commerce businesses in Iran faced immediate losses. Every hour without internet is an hour without sales, without customer service, without the ability to fulfill orders. For small businesses operating on thin margins, a 90-hour shutdown can mean the difference between profit and loss for the week or month.

The service sector was particularly affected. Banks couldn't process transactions online. Payment processors went offline. Accounting and payroll systems that relied on cloud services became inaccessible. Companies had to halt operations because they simply couldn't do business without internet connectivity.

International trade was disrupted. Companies importing or exporting goods couldn't coordinate shipments, couldn't access customs documentation, couldn't communicate with international partners. This causes cascading delays that extend well beyond the 90-hour shutdown.

Freelance workers and remote employees lost income. Someone working for a international company and earning income through the internet suddenly had no way to access their work platforms or submit deliverables. For workers in countries with limited local job opportunities, the blackout meant zero income for five days.

Tourism took a hit. Hotels couldn't make reservations online, restaurants couldn't accept digital payments, attractions couldn't be booked. The shutdown disrupted the entire tourism experience for both domestic and international visitors.

Telecommunications companies faced enormous pressure. When the blackout ended, they faced massive spikes in demand as everyone tried to access the internet simultaneously. The infrastructure strain could have caused additional outages, requiring careful orchestration of the restoration process.

The World Bank and other economic research organizations have estimated that internet shutdowns cost countries hundreds of millions of dollars. Iran's 90-hour blackout likely cost somewhere in the range of tens to hundreds of millions of dollars, depending on economic models and assumptions. These aren't trivial sums.

But the economic impact is really just the visible part. The deeper economic impact comes from the loss of trust and confidence. Businesses that experience a shutdown may decide to diversify their infrastructure to be less dependent on internet connectivity. They might invest in backup systems, redundancy, and offline capabilities. These adaptations increase costs and reduce efficiency.

More fundamentally, severe and extended internet shutdowns make a country a less attractive place to do business. Companies considering expanding operations to Iran face new risks. What if another shutdown happens? How will they maintain operations? This uncertainty creates economic drag long after the blackout ends.

For a country that's already facing economic challenges due to international sanctions and geopolitical factors, internet shutdowns add another layer of economic instability. Over time, this discourages investment and slows economic growth.

Privacy, Surveillance, and Digital Rights During Shutdowns

When the internet comes back after a blackout, the government often has new tools and expanded capabilities. This is because shutdowns force the government to build infrastructure and implement processes that can be used for ongoing surveillance and control.

During the blackout restoration process, the government controlled exactly which services came back online and in what order. Social media came back slowly. International connectivity was restored last. This staging gave the government a window to monitor who was trying to connect to what, before everything came back at full capacity.

The surveillance infrastructure built to implement the blackout doesn't disappear once the shutdown ends. Deep packet inspection systems that were deployed to identify VPNs and proxies remain in place. Border gateway filtering equipment stays installed. The government now has tools for granular surveillance that they didn't have before.

This is a pattern in digital authoritarianism. Each cycle of control and censorship leaves behind infrastructure that can be used for the next cycle. Each shutdown teaches the government more about how people try to circumvent restrictions, informing the next generation of tools.

From a privacy perspective, shutdowns also highlight how exposed people are when they don't have proper encryption and security measures in place. When the internet comes back, the government can monitor who immediately accesses privacy tools or political websites. They can identify activists and dissidents based on their reconnection behavior.

Privacy advocates argue that the solution is widespread encryption and use of privacy tools before shutdowns occur. If everyone is using VPNs and encrypted messaging by default, then when the internet comes back, the government can't identify who's accessing what. But if most people aren't using encryption, the government can easily spot the people who suddenly start using privacy tools after the shutdown ends.

This creates a classic security problem: if you only start using security tools when you're under threat, you become visible. But if you use them beforehand, you remain anonymous in a crowd of other users. The most secure approach is universal adoption of privacy tools, but this requires a level of digital literacy and security consciousness that most people don't have.

Shutdowns also have implications for data rights. When internet services are unavailable, people lose access to their own data stored in cloud services. They can't back up new information. They can't access files they need for work or personal reasons. After the shutdown, they face questions about what data was lost or corrupted, whether their accounts were compromised, and whether the government accessed their accounts during the downtime.

The privacy implications extend to location data. When cellular service is degraded or offline, location tracking becomes less accurate. But when the internet comes back, the government can potentially see where people have been moving through the location history data from their devices. This can be used to identify who was at protest sites or other sensitive locations.

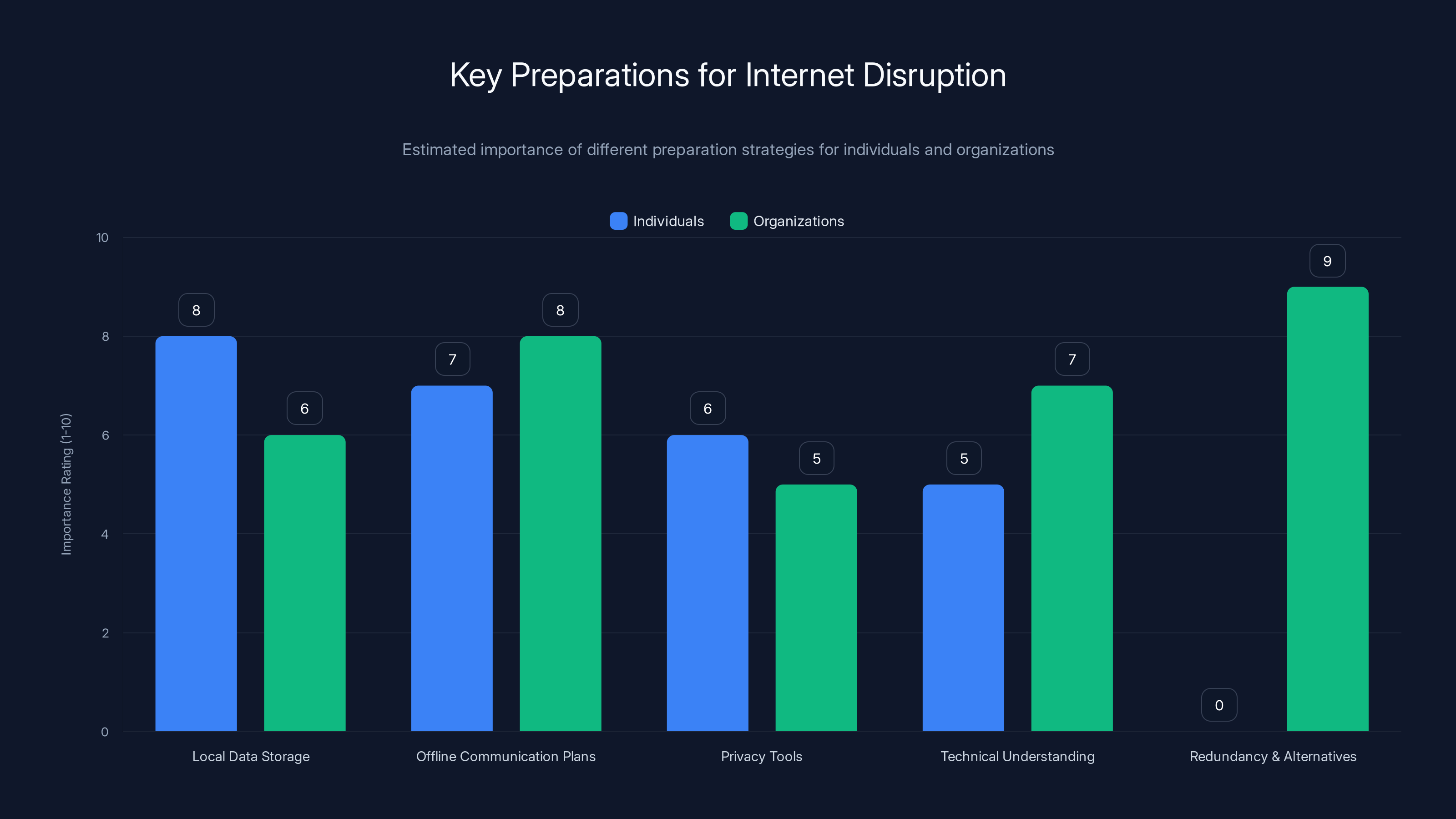

Both individuals and organizations should prioritize offline communication plans and local data storage. Organizations must also focus on redundancy and alternatives. Estimated data based on typical preparedness strategies.

Government Justification vs. Reality: Propaganda and Narrative Control

Every government that implements an internet shutdown offers some justification. These justifications are important to examine because they reveal how governments rationalize extreme measures and why they're increasingly willing to implement shutdowns.

Iran's government framed the blackout as a temporary measure necessary to restore order during a public security crisis. They suggested that the internet was being used to coordinate violence and that shutting it down was necessary to protect citizens. This narrative was consistent with how other governments that have implemented shutdowns have framed their actions.

The justification typically includes several elements. First, a claim that specific communications tools were being used for illegal purposes, such as coordinating violence or terrorism. Second, a suggestion that the shutdown was temporary and would end once the crisis was resolved. Third, an appeal to national security and public safety. Fourth, an implied criticism that outside observers don't understand the local situation or the severity of the crisis.

These justifications can be superficially compelling. If you believe there's a public safety crisis and that the internet is facilitating illegal activity, shutting it down might seem reasonable. But examining the specifics reveals that the justification doesn't match the implementation.

First, the blackout was nearly total, not targeted at specific platforms or communications used for the alleged illegal activity. If the goal was to stop coordination of violence, the government could have blocked encrypted messaging apps specifically. Instead, they shut down all internet access, including services used for legitimate business, healthcare, and journalism. This suggests the goal wasn't combating specific illegal activity but rather controlling information more broadly.

Second, the duration was far longer than necessary to address an immediate public safety threat. A public security crisis might justify a few hours of internet restriction. But over 90 hours? The duration suggests the goal was to suppress information and disrupt the protest movement, not to address an immediate threat.

Third, the restoration wasn't based on any specific improvement in the public safety situation. The internet came back because the government decided it would, not because conditions had changed enough to no longer warrant the shutdown. This indicates the shutdown was not proportional to any concrete threat but was instead a tool for political control.

Fourth, even if there were legitimate public safety concerns, international human rights law suggests that shutdowns must be a last resort, must be narrowly tailored, and must be time-limited. A nearly total blackout lasting over 90 hours doesn't meet these criteria.

The narrative justification also serves a function within Iran's domestic political context. By framing the shutdown as necessary for public safety, the government was trying to shift responsibility from itself to external threats or the protest movement. The government wasn't shutting down the internet out of malice or desire for control—they were doing it to protect people. This is a powerful narrative, even if the facts don't support it.

International propaganda also plays a role. By controlling which narratives emerge during the blackout, the government can shape how the events are understood globally. Without contradicting information, the government's version of events becomes the default narrative, at least for a period.

This is where internet shutdowns differ from other forms of censorship. Censoring specific websites or messages still allows some information to flow. A blackout prevents all information from flowing, giving the government an information monopoly. During the 90+ hour blackout, the Iranian government's narrative was essentially unchallenged because there was no way to communicate contradictory information to a global audience.

Future Outlook: Will Internet Shutdowns Become More Common?

If you're asking whether Iran's blackout was a one-time event or the beginning of a trend, the evidence points clearly toward escalation. Internet shutdowns are becoming more frequent, more normalized, and more sophisticated.

Several factors suggest that shutdowns will become more common. First, they work. From the government's perspective, they achieve the goal of suppressing information and disrupting movements. The 2024 blackout disrupted the protest movement and prevented global media coverage. Success breeds repetition.

Second, there are few consequences. The international response to Iran's blackout was criticism and condemnation, but no meaningful sanctions, no military action, no significant economic penalties targeting the blackout specifically. Governments calculating the cost-benefit of a shutdown have to conclude that the benefits outweigh the risks.

Third, the technical barriers are declining. Countries are learning from each other's successes. What took Iran years to develop, another country might implement in months by copying Iran's approach. As the technical knowledge spreads, more countries will have the capability to execute sophisticated shutdowns.

Fourth, internet infrastructure is becoming more centralized in some regions, making shutdowns easier. In countries where internet connectivity is concentrated in a few major providers or gateways, the technical challenge of a blackout is simpler. Infrastructure concentration is often justified on efficiency grounds, but it has the side effect of making shutdowns more feasible.

Fifth, geopolitical tensions are increasing, creating more scenarios where governments might view shutdowns as justified. During crises, shutdowns begin to seem like reasonable emergency measures rather than human rights violations.

Sixth, surveillance technology is improving, making governments more confident in their ability to control information. If a government can track who's trying to use VPNs and identify activists through digital traces, they're more likely to shut down the internet, knowing they can identify and prosecute dissidents afterward.

The future trajectory suggests that internet shutdowns will become more common, longer, and more sophisticated. This is bad for digital freedom, bad for human rights, bad for economic development, and bad for global information flow.

What could reverse this trend? International pressure and consequences would help, but as noted, such pressure has been ineffective so far. Countries would need to face serious economic sanctions, international isolation, or other penalties that outweigh the political benefits of shutdowns. This seems unlikely without more coordinated global response.

Another possibility is technical resilience. If countries and individuals invest in distributed internet infrastructure, mesh networks, and other technologies that can't be easily shut down, shutdowns become less effective. But this requires massive investment and changes to how internet infrastructure works fundamentally.

A third possibility is changing governance. If countries democratize and establish stronger protections for digital rights and freedom of information, shutdowns become politically impossible. But democratization happens slowly and inconsistently.

The most likely scenario is that internet shutdowns will continue to increase, become more normalized internationally, and become more sophisticated. This is depressing, but it's what the trend data suggests.

What You Can Do: Preparing for Internet Disruption

Given the reality that internet shutdowns are becoming more common, what can individuals and organizations do to prepare?

For individuals, there are several practical steps. First, store important data locally as well as in cloud services. If the internet goes down, you want access to critical information without depending on external connectivity. This means keeping local backups of documents, photos, and other important files.

Second, establish communication plans that don't depend on internet connectivity. This might include satellite phones for critical contacts, pre-arranged meeting locations if you can't reach people electronically, or other offline communication methods.

Third, learn about privacy tools before you need them. If you wait until an internet shutdown or heavy censorship begins, you'll be obvious using privacy tools for the first time. But if you're already using VPNs, encrypted messaging, and other privacy technologies, you blend in with millions of other users.

Fourth, understand the technical reality of shutdowns so you don't rely on tools that won't work. VPNs are useful for censorship, but not for infrastructure-level shutdowns. Tor is more resilient but slower and requires knowledge to use securely. Satellite internet is possible but expensive and requires equipment.

For organizations, the preparations are more complex. Companies should assess their dependence on internet connectivity and identify critical functions that require it. Where possible, build redundancy and offline alternatives. For services that absolutely require internet, consider diversification of connectivity options, such as having multiple ISPs or backup satellite internet.

Organizations should also develop communication plans for scenarios where internet is unavailable or restricted. How will employees stay connected? How will critical operations continue? How will you maintain communication with customers and partners?

Journalists and human rights organizations should consider secure communication infrastructure that doesn't depend on commercial internet services. This might include encrypted radio systems, secure satellite phones, or other backup communication methods.

Governments and international organizations should work toward better protections for internet infrastructure and stronger international norms against shutdowns. This is slower and less practical than individual preparation, but it's essential for long-term solutions.

The hard truth is that once a government decides to shut down the internet, there are no perfect solutions for the affected population. The goal of preparation is to minimize the damage and maintain some level of communication and access to information despite the shutdown.

Lessons for Global Digital Infrastructure and Resilience

Iran's 90+ hour blackout provides several important lessons for how we think about internet infrastructure, resilience, and digital rights globally.

First, the concentration of internet infrastructure is a systemic vulnerability. When a country has only a handful of international gateways, any of which can be controlled by the government, the system is fragile by design. More distributed infrastructure would be more resilient, but it would also be more expensive and complex.

Second, internet access is a political issue, not just a technical one. Making the internet more resilient requires not just technological solutions but also political commitment to internet freedom. If governments don't support internet resilience for political reasons, technical improvements alone won't solve the problem.

Third, the global internet governance system doesn't have adequate mechanisms to prevent or respond to shutdowns. International organizations can condemn shutdowns, but they can't prevent them or enforce consequences. This gap in governance will likely become more important as shutdowns become more common.

Fourth, individual preparation and privacy tools are necessary but insufficient. Even the most privacy-conscious person can't stay connected during an infrastructure-level shutdown. Systemic solutions are needed, not just individual technical literacy.

Fifth, the economic cost of shutdowns is significant, and this cost should factor into government calculations. If governments understood the full economic damage caused by shutdowns, they might be less willing to implement them. But governments often underestimate these costs or prioritize political control over economic performance.

Sixth, shutdowns have a ripple effect beyond the immediate affected country. International businesses lose access to Iranian customers and partners. Global information flow is disrupted. Media outlets lose sources and information. The impact extends far beyond Iran's borders.

Seventh, shutdowns are a symptom of broader digital authoritarianism. If shutdowns are becoming more common, it's because governments are becoming more willing and able to control digital infrastructure. This trend threatens digital freedom globally and requires collective response.

The lessons suggest that creating a more resilient and free internet requires action at multiple levels: technical infrastructure development, international governance reform, national policy changes, and individual digital literacy and preparation. It's not a problem with a simple solution, but understanding the dimensions of the problem is the first step toward addressing it.

Glossary of Technical Terms and Concepts

Internet shutdowns involve several technical concepts that are useful to understand. Here's a breakdown of key terms:

Border Gateway Protocol (BGP): The system that routes internet traffic globally. When BGP routes are withdrawn, traffic can't reach its destination.

Deep Packet Inspection (DPI): Technology that examines the contents of data packets to identify what type of traffic they are. Used to block specific applications or protocols.

International Gateway: Physical location where a country's internet connects to the global internet. Controlling these gateways allows control over all international traffic.

Internet Service Provider (ISP): Companies that provide internet connectivity to customers. In countries with few ISPs, control is more centralized.

VPN (Virtual Private Network): Service that encrypts your internet traffic and routes it through a server elsewhere, obscuring your activities from your ISP.

Tor: Network that routes traffic through multiple encrypted relays, making tracking extremely difficult. More resilient to censorship but slower than VPNs.

Proxy: Server that sits between you and your destination, making requests on your behalf. Useful for censorship circumvention but less secure than VPNs.

Mesh Network: Network where devices connect directly to each other, allowing communication even if some connections are down. More resilient but requires specialized software and devices.

Internet Exchange Point (IXP): Physical location where internet service providers exchange traffic. Similar to international gateways but for domestic traffic.

Latency: Delay in data transmission. During throttling, latency increases, making connections slow and unreliable.

Conclusion: What Iran's Digital Blackout Means for the Future

Iran's 90+ hour internet blackout is significant not because it was unique, but because it's part of an escalating pattern. Every year, more shutdowns occur. They get longer and more sophisticated. International response remains inadequate. The trend points clearly toward more, not fewer, shutdowns in the future.

What happened in Iran can happen elsewhere. In fact, elements of it already have. Venezuela has implemented internet restrictions. Myanmar has had shutdowns. Pakistan has cut connectivity during elections. Sudan has shut down the internet during conflicts. This isn't an Iranian phenomenon—it's a global trend.

The implications are serious. An internet where governments can simply turn off connectivity at will is an internet that's fundamentally broken for human rights and freedom. It's an internet that's less useful for economic development. It's an internet where power is concentrated in the hands of government authorities.

The solutions exist, but they require action at multiple levels. Technically, we need more distributed infrastructure that can't be easily shut down. Politically, we need stronger international norms against shutdowns and consequences for countries that implement them. Individually, we need better digital literacy and preparation for scenarios where internet connectivity is disrupted.

Most importantly, we need to recognize that internet shutdowns aren't exceptions or anomalies. They're becoming part of how governments operate. If we don't want a future where internet access is controlled by government decree, we need to act now—before shutdowns become as normalized as other forms of censorship.

Iran's 2024 blackout was over ninety hours. The next one might be longer. Without significant changes in how internet infrastructure is built and governed, without stronger international protections for digital rights, and without individual preparation, we should expect shutdowns to become increasingly common and increasingly sophisticated.

The digital divide—the gap between those with reliable internet access and those without—is about to include a new dimension: those in countries that use shutdowns as a control mechanism. As this divide grows, digital freedom becomes increasingly unequal globally.

The question isn't whether internet shutdowns will happen again. They will. The question is whether the international community, internet infrastructure providers, governments, organizations, and individuals will take the steps necessary to make shutdowns less effective and less common. The answer to that question will determine what kind of internet we have in the coming years.

FAQ

What exactly is an internet blackout and how does it differ from regular censorship?

An internet blackout is a complete or near-complete shutdown of internet connectivity, preventing people from accessing any online services. It differs from censorship, which blocks specific websites or content while leaving internet connectivity intact. During a blackout, people can't access anything online—not just forbidden content, but legitimate services, news sites, and communication platforms. It's the difference between a bouncer checking IDs at a club (censorship) and closing the club entirely (blackout).

Why did Iran shut down the internet for over 90 hours?

The Iranian government implemented the blackout during large-scale protests to prevent coordination and information sharing. Without internet, activists couldn't document government actions, organize demonstrations, or communicate with the international media. The blackout also prevented the government's actions during the protests from being recorded and shared globally. From the government's perspective, the blackout gave them control over the narrative and disrupted the protest movement's ability to organize.

Can VPNs bypass internet blackouts?

VPNs can be useful tools for circumventing internet censorship when specific websites are blocked, but they're largely ineffective during infrastructure-level shutdowns like Iran's. When international gateways are shut down, there's no path for traffic to leave the country, even encrypted VPN traffic. VPNs only work if the internet infrastructure still exists—if you can reach a VPN server somehow. During a total blackout, unless you have backup connectivity (like satellite internet), VPNs won't help.

What were the economic consequences of the 90+ hour blackout?

The blackout disrupted all e-commerce, banking, international business, and online services. Companies couldn't process transactions, make or receive payments, or access cloud-based systems. Freelancers and remote workers lost income. International trade was disrupted. Estimates suggest the blackout cost the Iranian economy hundreds of millions of dollars across the five-day period, though precise figures are difficult to calculate. The longer-term impact includes reduced business confidence in Iran and increased costs as companies implement backup systems for future shutdowns.

How do governments technically implement internet shutdowns?

Governments control shutdowns by directing internet service providers to stop routing traffic through international gateways. This is done at the network level through Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) announcements. The government essentially tells routers worldwide that Iran's internet networks are unreachable. Additionally, governments can order ISPs to block connectivity domestically. The process involves coordination between the government and the companies that operate internet infrastructure, and companies typically comply because refusing government orders carries severe penalties.

Are internet shutdowns legal under international law?

International human rights law, particularly the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, protects freedom of expression and access to information. The UN Human Rights Office has stated that internet shutdowns violate international law. However, enforcement mechanisms are weak. Countries can implement shutdowns knowing that while the international community will condemn them, there are unlikely to be serious legal or economic consequences. The legal framework exists, but the will to enforce it is lacking.

What should individuals do to prepare for potential internet shutdowns?

Store critical data locally, not just in cloud services. Establish communication plans that don't depend on internet. Learn about privacy tools before you need them so you're not obviously using security measures when a crisis occurs. Understand that VPNs work for censorship but not for blackouts. Consider satellite phones or other backup communication methods if you live in a region at risk. For journalists and activists, prepare secure storage for documentation and pre-arrange ways to share information once connectivity is restored.

Will internet shutdowns become more common?

All evidence suggests yes. Shutdowns are becoming more frequent globally, they're lasting longer, and they're becoming more sophisticated. Governments are learning from each other's successes. The international consequences remain minimal, creating weak incentives against implementation. As infrastructure becomes more concentrated in some regions, shutdowns become technically easier. Without significant international response or technical changes to internet infrastructure, expect shutdowns to become more normalized.

What's the difference between an internet blackout and internet throttling?

Internet throttling is when speeds are reduced—pages load slowly, videos buffer, connections are unreliable. Services technically still exist, but accessing them becomes very difficult. An internet blackout is a complete loss of connectivity. Throttling is sometimes a precursor to a full blackout or used as a control mechanism short of complete shutdown. Iran's 2024 blackout involved both—throttling first as connectivity was degraded, then a complete shutdown.

How does an internet blackout affect healthcare and emergency services?

Healthcare systems that rely on digital records become unable to access patient information. Hospitals using cloud-based systems for prescriptions, imaging, and scheduling lose access. Emergency services that coordinate through digital systems may face challenges. Telemedicine becomes impossible. People with chronic conditions who rely on digital monitoring or remote consultations lose those services. Pharmacies can't check inventory or insurance coverage. The impact on healthcare can be significant, particularly for people with serious medical conditions that require ongoing monitoring or treatment coordination.

Key Takeaways

- Shutdowns are escalating: Iran's 90+ hour blackout is part of an increasing trend of internet shutdowns globally, with shutdowns becoming longer, more frequent, and more sophisticated over time

- Infrastructure matters: Countries with centralized internet infrastructure (few gateways, few ISPs) can more easily implement shutdowns, revealing critical vulnerability in global internet architecture

- Economic damage is real: Shutdowns cost hundreds of millions of dollars in lost business, disrupted trade, and economic uncertainty, creating long-term damage beyond the immediate impact

- Individual tools have limits: VPNs and proxies help against censorship but are ineffective against infrastructure shutdowns; preparation requires multiple approaches including offline data storage and communication plans

- International response is weak: Shutdowns face only diplomatic criticism without meaningful economic or political consequences, creating weak incentives for governments to avoid them

- Preparation is essential: For individuals and organizations in regions at risk, preparing for shutdowns through data backup, communication redundancy, and digital literacy reduces vulnerability

- The future trajectory is concerning: Without significant changes to internet infrastructure governance and stronger international protections, shutdowns will become increasingly common and normalized

Related Articles

- Iran's Internet Collapse: What Happened and Why It Matters [2025]

- Discord Blocked in Egypt: Why VPN Usage Spiked 103% [2025]

- How to Change Your Location With a VPN: Complete Guide [2025]

- ExpressVPN 78% Off Deal: Is It Worth It in 2025?

- Meta Closes 550,000 Accounts: Australia's Social Media Ban Impact [2025]

- Indonesia Blocks Grok Over Deepfakes: What Happened [2025]

![Iran Internet Blackout: What Happened & Why It Matters [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/iran-internet-blackout-what-happened-why-it-matters-2025/image-1-1768239498187.jpg)