France's VPN Ban for Minors: Digital Control or Privacy Destruction [2025]

France is about to cross a line that might make even surveillance-state advocates uncomfortable. While the government works to keep teenagers off social media platforms, it's simultaneously eyeing restrictions on virtual private networks—the very technology that protects digital privacy for millions of users. This isn't a casual policy proposal buried in some legislative footnote. It's a deliberate strategy that could reshape how governments regulate internet access for an entire generation.

Anne Le Hénanff, France's Minister Delegate for Artificial Intelligence and Digital Affairs, made headlines recently when she casually mentioned during a Franceinfo broadcast that VPNs are "the next topic on my list." That comment, seemingly offhand, signals something far more alarming: the government is actively considering whether restricting VPN access for anyone under 15 should become law. Think about that for a moment. France isn't just proposing age limits on social media. It's contemplating shutting down one of the most fundamental tools for digital privacy and security—specifically for young people.

This situation exposes a critical tension in modern governance. On one hand, the concerns about minors and social media are legitimate. The mental health impacts of constant social comparison, algorithmic addiction, and cyberbullying are well-documented. On the other hand, banning VPNs doesn't protect kids—it surveils them. It transforms privacy protection into a mechanism of control. And once that precedent is set in France, other nations will inevitably follow.

What makes this particularly troubling is the broader context. Europe has positioned itself as a privacy-first continent, championing strict data protection through mechanisms like GDPR. Yet France is now proposing to undermine that very philosophy in the name of child protection. The contradiction is stunning. You can't claim to value privacy while simultaneously restricting the tools that enable it.

This article explores what France's proposed VPN restrictions actually mean, why they're fundamentally misguided, what alternatives exist, and what this tells us about the future of digital regulation globally. We'll examine the technical realities, the privacy implications, the geopolitical consequences, and the human cost of these policies.

TL; DR

- France is considering VPN bans for minors under 15 as part of broader social media restrictions, with government officials explicitly naming them as "next on the list" according to TechRadar.

- VPN restrictions create privacy nightmares, enabling unprecedented government surveillance while failing to actually protect children from determined access as noted by WebProNews.

- Age verification alternatives exist but carry their own data privacy risks that haven't been adequately addressed by policymakers as discussed by Tech Policy Press.

- Global precedent matters: If France succeeds, other nations will quickly follow, creating a fragmented internet where privacy protection is treated as a threat as reported by Reuters.

- Technical reality: VPN bans are difficult to enforce and easily circumvented, making them security theater rather than effective policy as highlighted by BBC News.

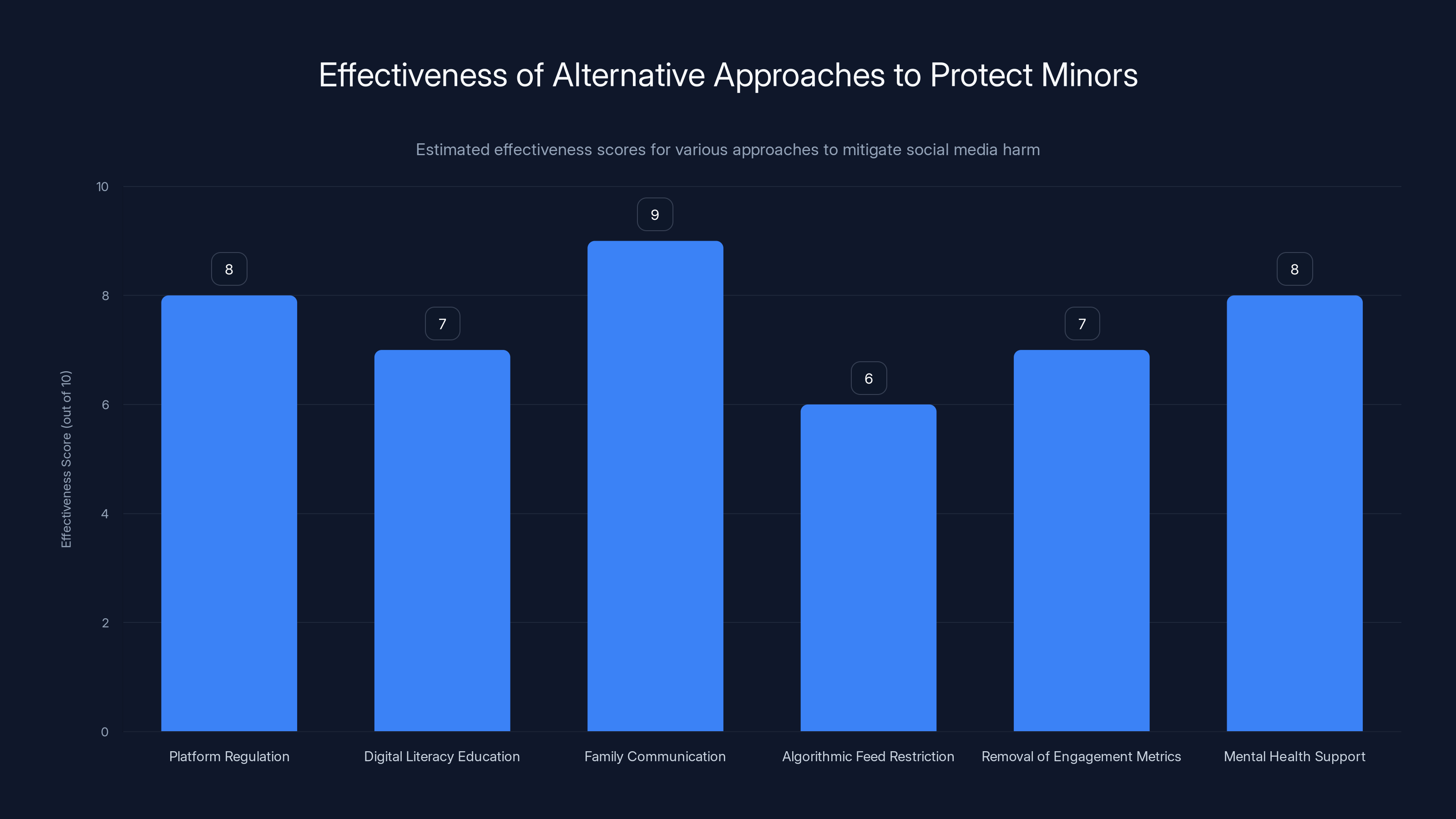

Estimated data: Family communication and platform regulation are among the most effective approaches to protect minors from social media harm.

The Current Situation: What France Is Actually Proposing

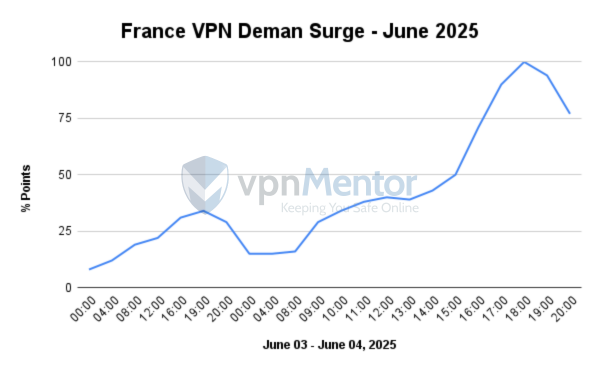

Let's be clear about what's happening here. France's government isn't hypothetically considering VPN restrictions. Officials are actively discussing them as part of a legislative package that's already advancing. The National Assembly voted 116-23 in favor of restricting social media access for minors under 15. That's substantial support. Now, with that momentum, government delegates are openly naming VPNs as their next legislative target.

When Le Hénanff said VPNs are "the next topic on my list," she wasn't musing philosophically. She was signaling legislative intent. In European bureaucratic language, that's as close to a policy announcement as you get without holding a press conference. The government is surveying the landscape, testing public reaction, and building the intellectual framework for restrictions.

The reasoning seems straightforward from a protective standpoint. If France successfully bans social media for under-15s, teenagers will immediately hunt for workarounds. VPNs are the most obvious solution. They mask your IP address and location, making it appear as though you're accessing the internet from a different country or region. A French teenager could theoretically use a VPN to appear as though they're logging in from Germany or Spain, bypassing French age verification systems.

From a child protection perspective, this is the logical next step in enforcement. From a privacy perspective, it's terrifying.

The proposal doesn't exist in isolation. Similar legislation has already surfaced elsewhere. The United Kingdom experienced a wave of online safety discussions after passing the Online Safety Bill. While it didn't explicitly target VPNs, it created pressure for age verification systems that could theoretically lead to VPN restrictions. Australia has entertained comparable ideas. Even the United States has seen proposals at the state level that hint at similar concerns.

France's approach is different in one crucial way: it's explicit. They're not dancing around the issue. They're directly naming VPNs as the problem to solve. This directness matters because it forces a conversation that other governments have been avoiding. What happens when you restrict privacy tools to protect minors? Who actually benefits from that arrangement?

The legislative timeline matters too. France's social media ban isn't finalized. It still needs Senate approval. But the government's simultaneous focus on VPN restrictions suggests they're thinking several steps ahead. They're building a comprehensive framework for controlling how minors access online content. Whether they ultimately succeed with VPNs remains uncertain, but the intent is unmistakable.

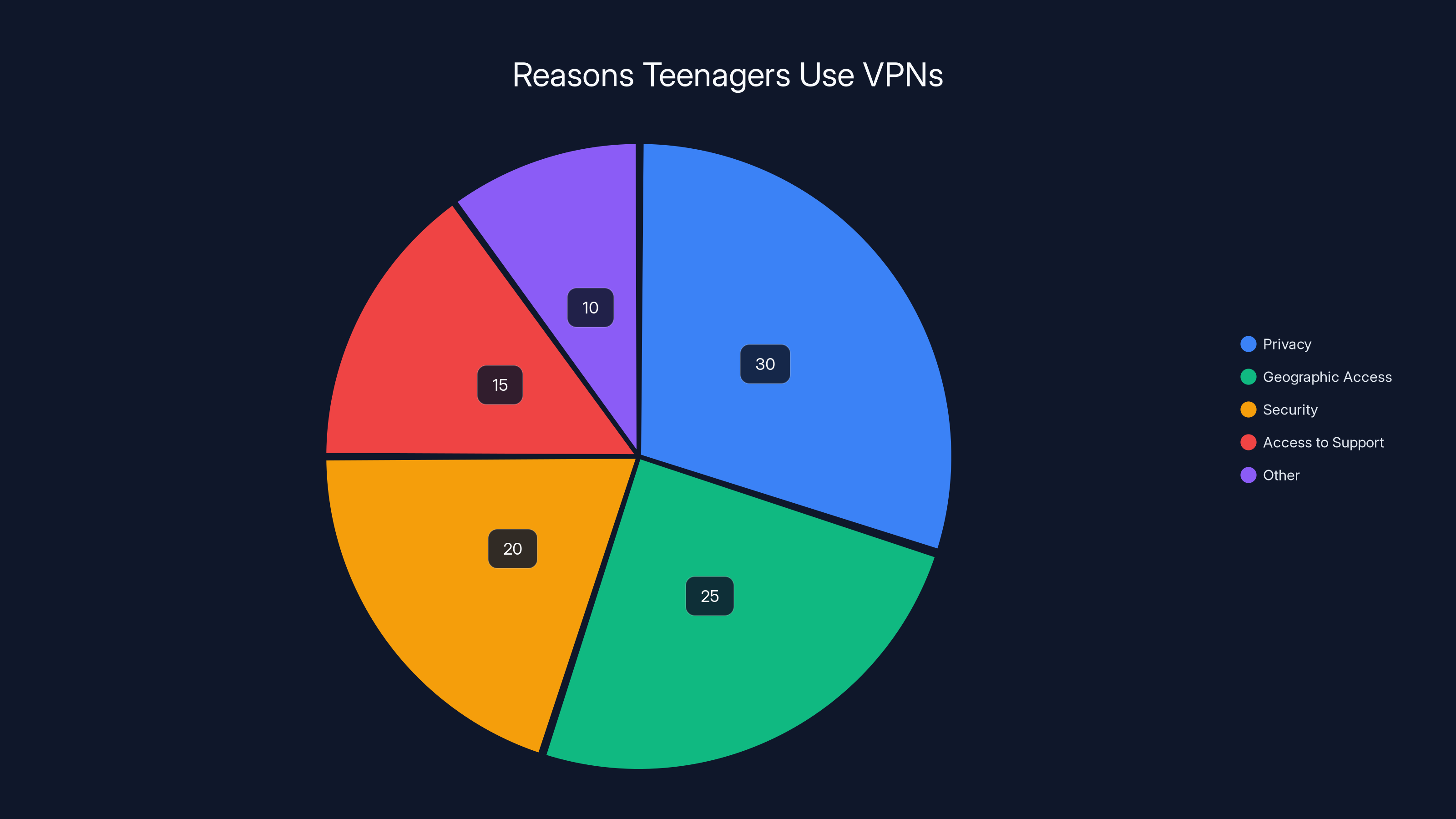

Why Teenagers Actually Use VPNs (And It's Not Just Social Media)

The government's narrative treats VPN usage like a simple bypass tool for social media. In reality, teenagers use VPNs for a much broader ecosystem of reasons—many of them perfectly legitimate and some directly related to personal safety.

First, there's the privacy angle that adults often overlook. Teenagers are acutely aware that their browsing behavior is tracked. They know about data collection. They understand that ISPs log their activity, that schools monitor network traffic, and that their phones report location data. For many young people, VPN usage is a rational response to pervasive surveillance, not necessarily evidence of wrongdoing.

Second, there's geographic access. Streaming services, educational content, and entertainment platforms vary by region. A French teenager might use a VPN to access a tutorial on a platform that's only available in the US, or to watch content that's geographically restricted. This isn't nefarious. It's solving a real access problem.

Third, there's security. Public Wi-Fi is notoriously insecure. At cafes, libraries, and schools, teenagers connect to networks that could expose them to man-in-the-middle attacks. A VPN encrypts that connection, protecting sensitive data from being intercepted. If France restricts VPN access, teenagers on public networks become more vulnerable to data theft, credential harvesting, and worse. The supposed protection actually increases risk.

Fourth—and this is the part government officials rarely acknowledge—some teenagers use VPNs to access mental health resources, LGBTQ+ support communities, or other sensitive content in environments where they don't feel safe being open about their identity. In households with controlling parents, VPNs provide a lifeline to communities and information that can literally save lives. Restricting VPN access means restricting access to potentially life-saving support.

Fifth, there's the geopolitical angle. Young people interested in understanding global events, accessing news censored in their country, or connecting with people across borders use VPNs for communication and information. France isn't known for heavy censorship, but the infrastructure of VPN restrictions could easily be repurposed by less democratic governments.

The French government's framing ignores all of this. They see VPN equals bypass tool equals problem to eliminate. But that's like solving internet safety by banning encryption entirely. You're destroying the solution to address the symptom, while ignoring the underlying problems.

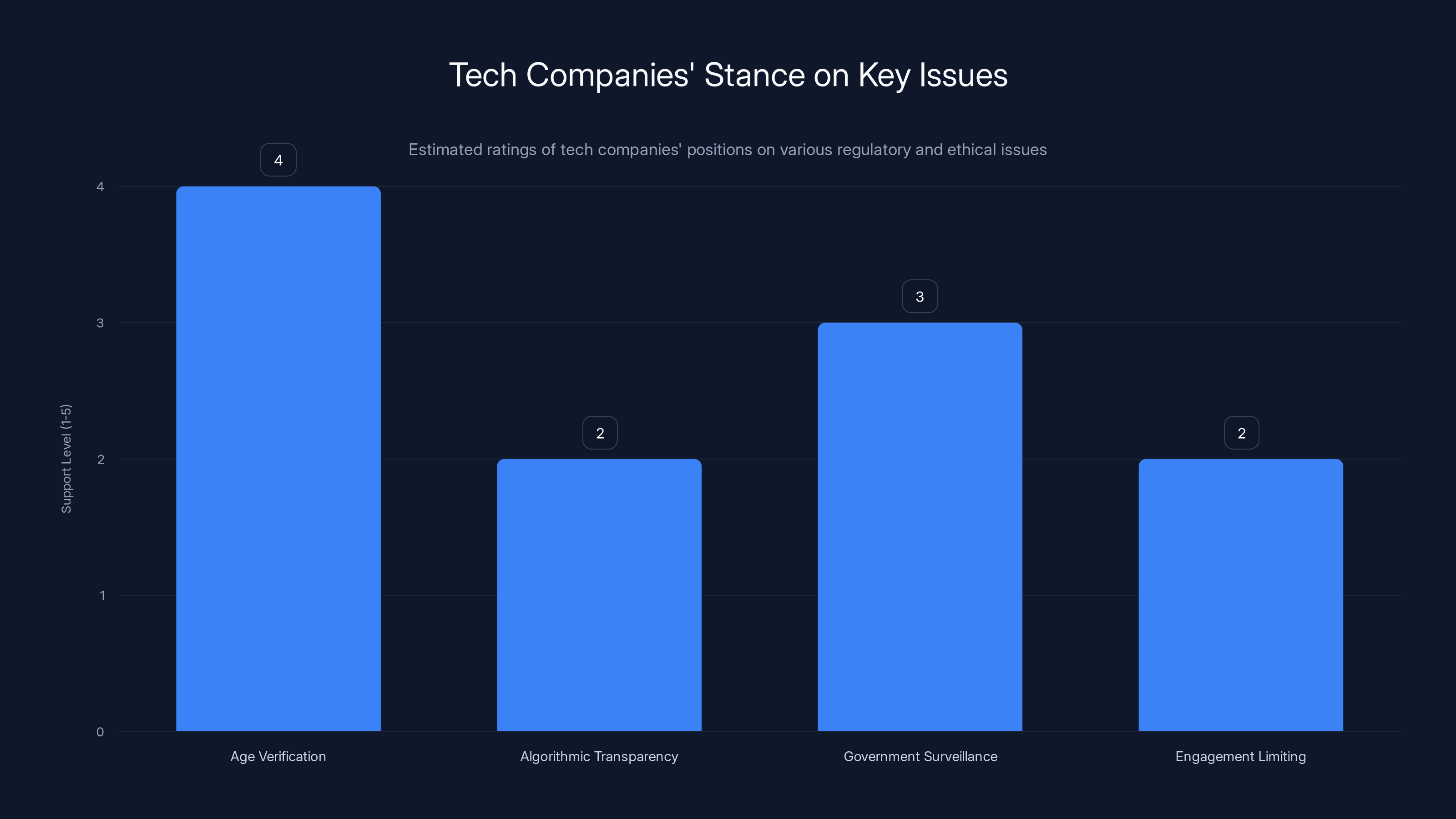

Tech companies are estimated to support age verification the most due to reduced liability, while showing less support for algorithmic transparency and engagement limiting. Estimated data.

The Age Verification Trap: Why Data Collection Is the Real Risk

Here's the uncomfortable truth that policymakers keep avoiding: restricting VPNs doesn't actually solve the problem. It just shifts it. If you can't restrict the tools, you have to restrict the service access itself. And that requires age verification.

France's implicit strategy seems to be building a comprehensive system where social media platforms require robust age verification before allowing access. This is where things get genuinely dystopian from a privacy standpoint.

Age verification, on the surface, sounds reasonable. You're confirming someone is actually the age they claim before letting them on a platform. But implementing age verification at scale creates several interlocking nightmares.

First, there's the data requirement. How do you verify someone's age? The most reliable method is accessing government ID databases. This requires either the platform collecting a copy of your ID directly, or the government sharing ID databases with private companies. Both options are privacy nightmares. If Snapchat or TikTok has copies of your government ID, that's a data breach waiting to happen. TikTok alone has been hacked; imagine ID documents exposed at that scale.

Alternatively, platforms could use third-party age verification services—companies that specialize in confirming someone's age by cross-checking public records, financial data, and other sources. These companies would accumulate vast databases of young people's personally identifiable information, creating honeypots for hackers. One data breach at an age verification service could expose the identity data of millions of teenagers across multiple platforms simultaneously.

Second, there's the surveillance infrastructure. Once you have a system that tracks which young people are accessing which services, you've created an unprecedented monitoring apparatus. Governments could access this data (willingly or through legal pressure). Parents could exploit it. Bad actors could weaponize it. A system built to "protect" children becomes a system that surveils them in ways previous generations would have found dystopian.

Third, there's the enforcement problem. Many age verification systems rely on secondary factors like payment methods. Does your teenager use a credit card? If not, what other verification methods do they have? This creates a de facto requirement for parental financial integration into social media access, which itself is a privacy and autonomy issue.

Fourth, there's the false sense of security. Young people are creative. They get older siblings to help. They use borrowed devices. They find workarounds. Age verification doesn't actually prevent access—it just adds friction and data collection. You're collecting millions of data points to prevent behavior that motivated individuals will circumvent anyway.

The irony is stunning: France is proposing to restrict privacy tools (VPNs) while simultaneously requiring the implementation of privacy-destroying verification systems. You're trading one form of surveillance for another, except the second form is worse because it's specifically designed to track minors and requires integration with government ID systems.

Technical Reality: Why VPN Bans Are Nearly Impossible to Enforce

Let's talk about the elephant in the room that French policymakers seem to be ignoring: VPN bans are technically difficult to enforce and easily circumvented.

VPNs aren't magical secret tools. They're software. The basic mechanism is encryption. Your device connects to a VPN server, and that connection is encrypted so nobody in between can see what you're doing. It's sophisticated, but it's not secret.

However—and this is crucial—detecting VPN usage and actually blocking it are two different things. Internet service providers can identify VPN traffic by analyzing the patterns of encrypted data. They can see that large volumes of data are flowing to a known VPN provider's IP address. But blocking it? That's much harder.

France would need to either block VPN IP addresses directly (which VPN providers respond to by constantly rotating IP addresses, making it a game of whack-a-mole), or they'd need to require ISPs to implement deep packet inspection, actively monitoring and analyzing encrypted traffic to identify which protocols are being used. Deep packet inspection is powerful, intrusive, and expensive.

More importantly, it's not foolproof. It's possible to disguise VPN traffic as regular encrypted traffic from services like Netflix or banking sites. You can wrap VPN connections in protocols that appear to be something else. The technology is complicated, but it exists. A determined teenager could use obfuscation tools to hide the fact that they're using a VPN.

Beyond that, there are alternatives to traditional VPNs. Proxy servers work similarly but are harder to detect. Tor, the anonymity network, routes traffic through multiple encrypted layers. SSH tunnels achieve similar privacy goals. If you ban VPNs specifically, you've only blocked one category of privacy tools. You haven't solved the underlying problem.

The UK discovered this after passing the Online Safety Bill. Discussions about VPN restrictions quickly ran into the technical reality: you can't actually ban them without either massive surveillance infrastructure or accepting that the ban will be ineffective. Some security researchers calculated that a comprehensive VPN ban would require monitoring equivalent in scale and scope to the surveillance systems in authoritarian regimes like China.

So why is France pursuing this if it won't actually work? That's the question that should concern people most. If the government knows these restrictions are technically difficult to enforce, then the real goal isn't protection—it's establishing precedent for internet surveillance infrastructure. You're not banning VPNs because they'll solve the problem. You're banning VPNs because doing so requires building the surveillance apparatus you actually want.

Privacy Paradox: Europe's GDPR vs. Its Own Surveillance Ambitions

This is where the hypocrisy becomes impossible to ignore. France is a leader in the European Union, a bloc that explicitly positions itself as privacy-forward. GDPR—the General Data Protection Regulation—is considered the world's strongest consumer privacy law. It was built specifically to protect citizens' data from exploitation.

Yet France is now proposing a policy that would require:

- Government ID sharing with private platforms

- Age verification databases tracking minors' activities

- Deep packet inspection of encrypted traffic

- Integration between government databases and private companies

- Comprehensive logging of which young people access which services

All of these directly contradict GDPR's principles. GDPR requires data minimization—collecting only the data necessary for a specific, legitimate purpose. Age verification for social media creates data collection far beyond that purpose. GDPR requires explicit consent—you can't just collect ID information without explicit, informed consent. Bundling ID verification with platform access pressure-coerces consent. GDPR requires data protection—but age verification systems accumulate massive honey pots of sensitive information.

EU legal experts have already noted this contradiction. Privacy advocates across Europe are raising alarms that France is building the legal and technical infrastructure for surveillance that GDPR was designed to prevent. The argument that it's "for the children" doesn't overcome the fundamental privacy violations. If anything, it's worse because it establishes the precedent that protecting children justifies suspending privacy rights.

Once that precedent is set, it doesn't stay limited to children. The surveillance infrastructure built for minors becomes available for adults. The justification expands. Before long, what started as child protection becomes the foundation for comprehensive government surveillance.

This isn't paranoia. It's how these systems actually evolve historically. Surveillance authorized for security purposes doesn't stay limited. It gets repurposed. The mechanisms built to "monitor VPN usage for minors" become tools for monitoring dissidents, journalists, and political opponents.

The contradictions are so obvious that you have to assume France's policymakers understand them. That means they're not actually concerned about the privacy implications. They're concerned about building surveillance infrastructure under the guise of child protection. That's an important distinction, and it should worry everyone.

Estimated data suggests that privacy and geographic access are the top reasons teenagers use VPNs, followed by security and accessing support communities.

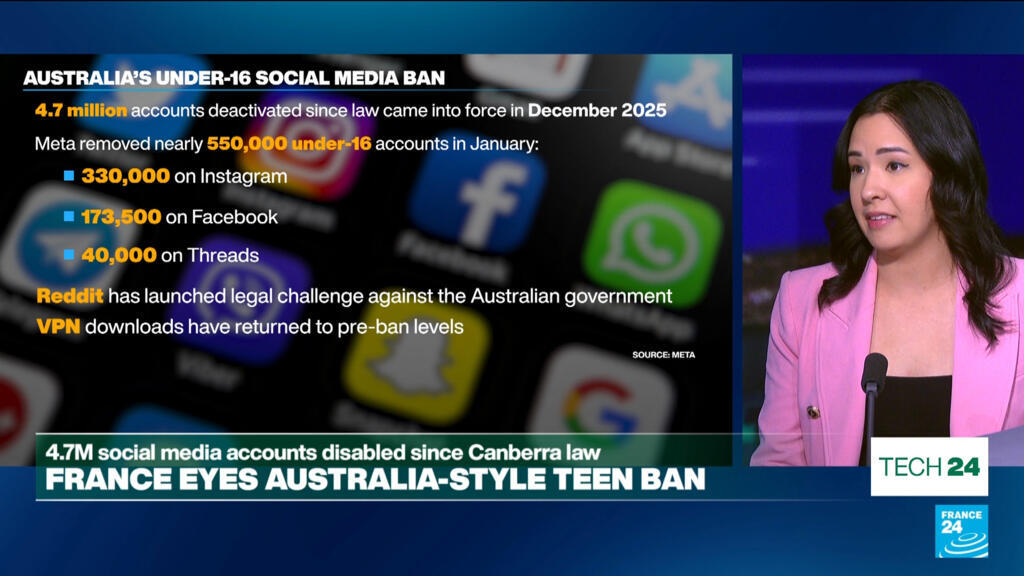

What Actually Happens When Countries Restrict VPNs: Real-World Evidence

France won't be the first country to contemplate VPN restrictions. Several nations have already gone down this path, and the evidence is instructive.

Russia has effectively restricted VPN access over the past decade. How? By blocking known VPN provider IP addresses and implementing aggressive deep packet inspection. The result: Russians determined to access restricted content find workarounds (using obfuscation tools, smaller VPN providers, proxy networks), while ordinary citizens just lose a privacy tool. The state gained surveillance capability. Privacy didn't actually improve for minors—it just became the government's monopoly instead of something citizens controlled.

China has gone further, requiring all VPN services to be government-approved. Privately operated VPNs are illegal. This creates an environment where the government can monitor all encrypted traffic. Children's privacy? That's irrelevant. The system is built for control, not protection.

India attempted VPN restrictions as part of broader internet control measures. Again, the outcome was surveillance capability for the government, minor inconvenience for people determined to use privacy tools, and lost privacy protection for everyone else.

The United Kingdom considered explicit VPN restrictions before abandoning the idea as technically infeasible and potentially legally problematic under their data protection framework. But the fact that they considered it, and had to actively reject it, shows how appealing these ideas are to policymakers despite being problematic in practice.

The pattern is consistent: VPN restrictions don't actually prevent access for determined individuals. They do establish surveillance infrastructure. They do indicate government intent toward comprehensive monitoring. And once the infrastructure exists, it inevitably gets repurposed beyond its original stated purpose.

Why would France want to replicate this? That's the real question. The answer suggests that controlling access and monitoring behavior is a goal independent of actually protecting minors.

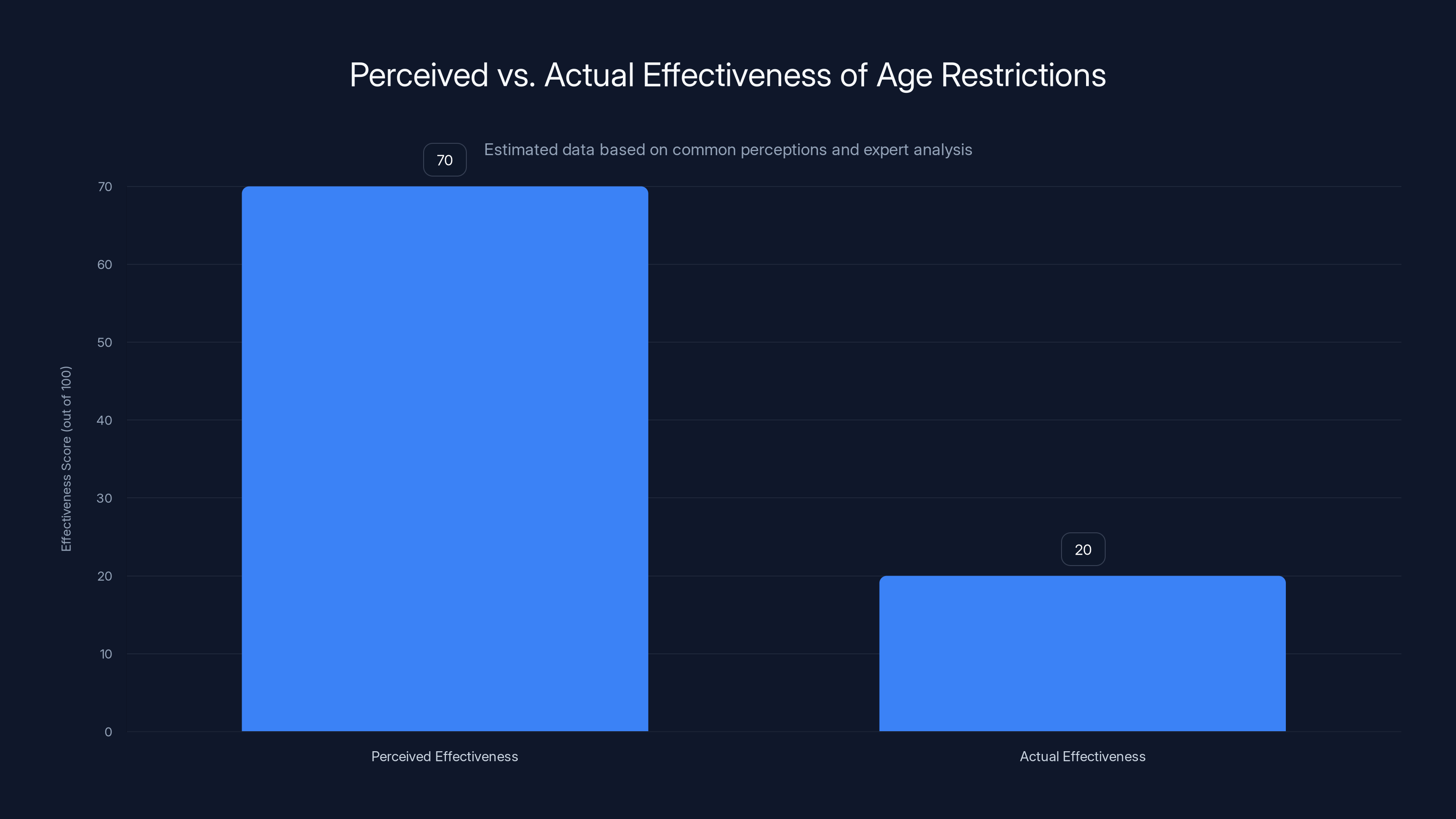

The Real Problem: Why Age Restrictions Alone Don't Work

Here's what France's government isn't saying but clearly understands: age restrictions on social media are performative. They don't actually solve the problem they claim to address.

For decades, platforms have had age requirements. You have to be 13 to use Facebook, 18 for some services. How many teenagers have breached these restrictions? Essentially all of them, at some point. The legal mechanism exists, but enforcement has always been absent because enforcement would require surveillance at the platform level or the ISP level or both.

The real issues driving government action aren't just about age. They're about algorithm design, engagement metrics, and business models. Social media platforms are built to be maximally engaging, which means they're optimized for triggering emotional responses, creating addiction, and promoting content that generates controversy.

These problems exist whether a user is 12 or 25. A 30-year-old gets equally addicted to algorithmic feeds. A 14-year-old and a 44-year-old both suffer from comparison-driven anxiety when scrolling through curated highlight reels. The business model of extracting engagement and selling attention to advertisers is the problem—not the age of the user.

But governments can't directly regulate the business model. They can't mandate that platforms optimize for user wellbeing instead of engagement because that would require restricting their business practices, which creates political opposition from powerful tech companies. Instead, governments find it easier to blame the users (especially young ones) and restrict their access. It feels like a solution, placates concerned parents, and avoids a direct conflict with the platforms.

So we get age bans that don't actually work, VPN restrictions that won't solve the problem even if they did work, and age verification systems that destroy privacy while failing to achieve the stated goal. It's security theater with extra steps.

The real solution would be difficult: platform regulation requiring algorithmic transparency, limits on engagement optimization, restrictions on targeted advertising to minors, mandated friction in habit-forming features, and genuine safety mechanisms. But that requires confronting the business model of social media itself, which governments are unwilling to do.

Instead, they're taking the easy path: restrict access, monitor behavior, and pretend this is protection.

LGBTQ+ Youth and Marginalized Communities: The Human Cost

There's a segment of this discussion that rarely gets political attention but deserves serious consideration: what happens to vulnerable teenagers when you restrict their privacy tools?

For LGBTQ+ youth, VPNs and privacy-enabling tools serve critical functions. In environments where coming out might be dangerous—whether due to family rejection, legal consequences, or simple social ostracism—these tools enable private exploration of identity. A teenager in a conservative household can safely access LGBTQ+ support communities without their parents monitoring their activity. They can find information, connect with peers, and develop self-understanding in private.

Restricting VPNs for minors means restricting that access. It forces these young people to either live in greater secrecy, abandon these resources entirely, or risk parental discovery and potential consequences. This isn't hypothetical. LGBTQ+ youth already experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, and suicide. Removing privacy tools that enable community and information access measurably worsens those mental health outcomes.

The same logic applies to teenagers in abusive situations, those experiencing gender dysphoria, those with mental health challenges, or those from marginalized communities generally. Privacy tools enable them to access help anonymously.

France's government would argue they're not restricting access to these resources, just restricting the privacy tool. But in practice, these are inseparable. Forcing a teenager to access mental health or community resources without privacy protection means forcing them to either abandon the resource or risk discovery and consequences.

This gets almost no media attention because it doesn't fit the narrative of "protecting children from social media addiction." But it's the human cost of surveillance infrastructure built under that justification. Vulnerable populations always bear the real burden.

Estimated data shows a significant gap between perceived and actual effectiveness of age restrictions on social media platforms.

Geopolitical Implications: The Fragmentation of Internet Privacy

If France successfully restricts VPNs, the implications extend far beyond France's borders. This becomes a geopolitical statement about how democracies are willing to treat internet privacy and surveillance.

Currently, VPNs operate in a gray legal space globally. Most countries tolerate them. Some encourage them as a security best practice. But no major Western democracy has explicitly banned them for any demographic. If France does, it breaks that precedent.

What happens next? Other EU nations face pressure to match France's restrictions, viewing VPN protection as a regional inconsistency. If some EU countries restrict VPNs and others don't, you create incentives for tech companies to locate data handling in permissive countries, and for users to circumvent restrictions by using services based in neighboring nations. Harmonizing regulations (meaning adopting France's model) becomes the easy political path.

Simultaneously, governments that are less committed to democratic values—or that have been looking for an excuse to implement surveillance—suddenly have cover. If France, a democracy and EU leader, has restricted VPNs for minors, then Hungary, Poland, or future authoritarian-leaning governments can justify doing the same, eventually expanding it to adults. The precedent matters less than the moral cover.

For countries that have positioned themselves as privacy leaders and counterweights to surveillance-state approaches, this is a significant strategic error. You're giving authoritarian-leaning governments the playbook for surveillance while claiming it's about child protection.

There's also an economic dimension. VPN companies, privacy-focused tech startups, and the broader ecosystem of privacy-protecting tools are disproportionately concentrated in Western countries. If those countries restrict privacy tools, it disadvantages Western companies and advantages state-controlled alternatives. It's unlikely anyone planned this that way, but the outcome is the same.

Alternative Approaches That Could Actually Work

If the genuine goal is protecting minors from harmful social media effects, several approaches would actually be more effective than banning VPNs or restricting access:

Platform regulation requiring algorithmic transparency, limiting engagement optimization, restricting targeted advertising to minors, and mandating friction in habit-forming features would address the actual harm. This is difficult and requires confronting the platforms' business models, but it actually solves the problem rather than just hiding it.

Digital literacy education that teaches young people how algorithms work, how to recognize manipulation, and how to engage critically with social media would build actual resilience. This is the unsexy solution that actually works but requires investment in education.

Family communication and guidance supported by resources for parents would be more effective than bans. Parents who understand social media and can talk to their kids about it are more protective than any technological restriction. This requires supporting families, not surveilling young people.

Restriction of algorithmic feeds to chronological order or user-controlled sorting would eliminate the engagement optimization that drives harm. Instead of restricting access, restrict the mechanism that creates addiction.

Removal of engagement metrics (likes, view counts, follower counts) would reduce comparison-driven anxiety. This addresses the psychological mechanism of harm directly. Mental health support and resources integrated into platforms would provide active protection rather than passive restriction. If young people are struggling, they need help—not surveillance.

None of these approaches require restricting privacy tools. None require building surveillance infrastructure. None require integrating government databases with private platforms. And all of them would actually address the underlying harms rather than just preventing access.

The fact that France isn't pursuing these alternatives, despite being obvious and more effective, suggests that the actual goal isn't protection. It's control, surveillance capability, and establishing the precedent that privacy protection is the enemy.

The Corporate Interest in Data Collection: Follow the Money

Let's be direct about something that rarely gets discussed: there's significant corporate interest in age verification and comprehensive data collection systems.

Social media platforms themselves don't necessarily want age restrictions. Fewer users means less engagement and advertising inventory. But they do want reliable age verification because it insulates them from regulatory liability. If they can demonstrate they've done age verification (even if it doesn't work), they have a legal defense against regulatory action.

Age verification companies have obvious incentive in expanding their market. They sell the verification services, the data storage, the integration infrastructure. A Europe-wide VPN ban that necessitates age verification is essentially a subsidy to the age verification industry.

Data brokers want access to age verification databases. Advertisers want more targeted data about teenagers. ISPs want the infrastructure and access to deep packet inspection technology. Government agencies want the surveillance capability. Each entity has profit or power motivation to support comprehensive monitoring systems.

When you follow the money and the incentives, the proposal starts to make sense—not as child protection, but as a system that benefits multiple powerful actors while appearing justified by protective rhetoric.

This isn't suggesting conspiracy. It's suggesting that the incentive structures point toward surveillance expansion, and protective rhetoric happens to align perfectly with those incentives. That's often how problematic policies gain momentum.

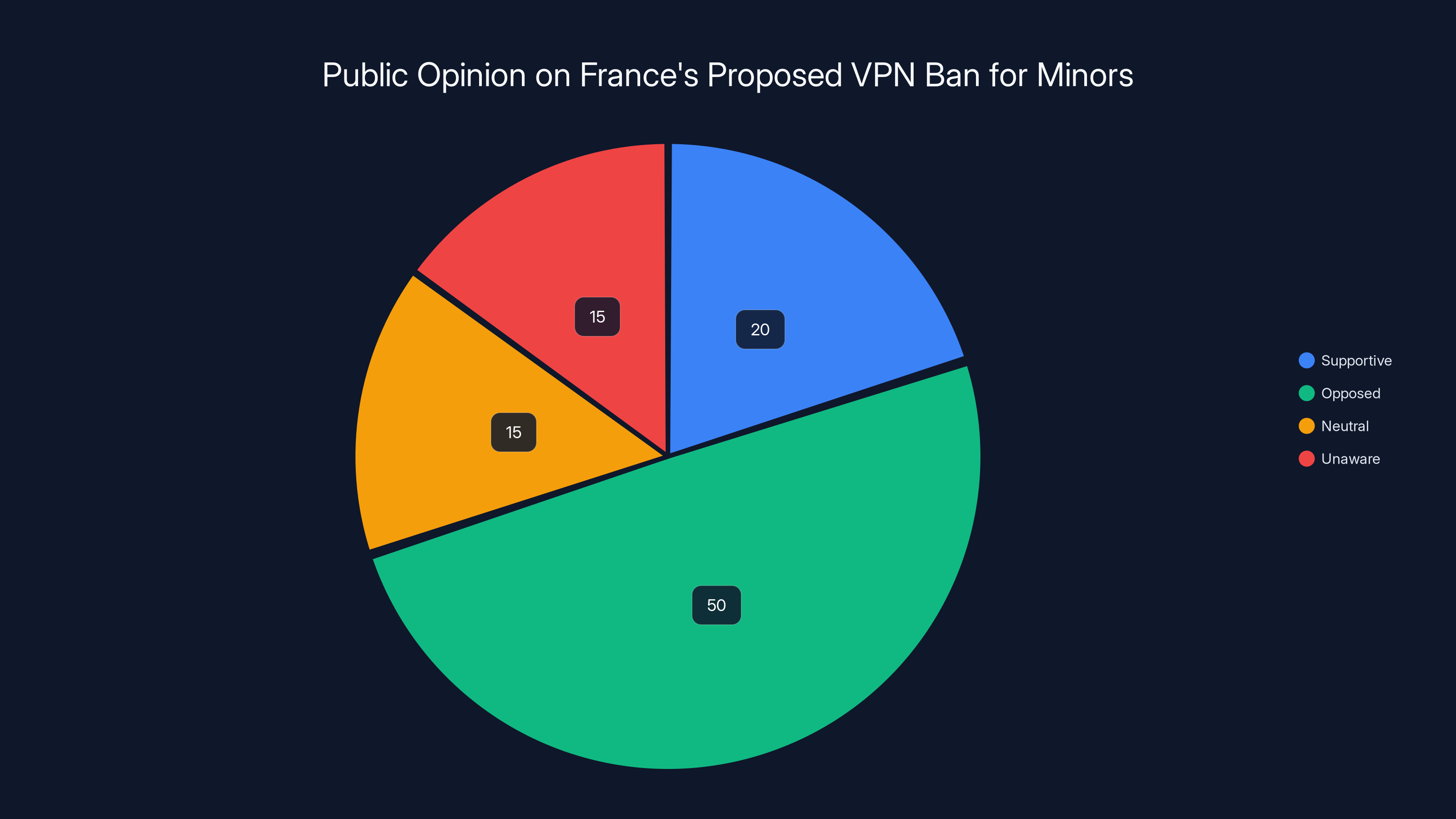

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of the public (50%) is opposed to France's proposed VPN ban for minors, reflecting concerns over privacy and digital freedom.

The Precedent Problem: How This Normalizes Surveillance

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of France's proposal is what it normalizes.

Once you accept that privacy tools should be restricted for minors, the justification for expanding those restrictions is established. If VPNs are restricted for 15-year-olds because they might bypass social media controls, what about 18-year-olds? The justification becomes protecting them from harmful content. What about 25-year-olds? Now the reasoning is protecting them from dangerous conspiracy theories or misinformation.

Once the infrastructure exists, it gets used. It gets normalized. What started as a restriction on minors becomes a tool for controlling information access for everyone. And by the time people realize the broader implications, the infrastructure is entrenched and politically difficult to remove.

This is the historical pattern of surveillance systems. They're always justified initially for a sympathetic case: protecting children, preventing terrorism, catching criminals. But once established, they inevitably expand. The scope creeps. The justification broadens. And governments that were uncomfortable with surveilling adults become comfortable doing so, having already normalized it for minors.

France's proposal, whether intentionally or not, establishes exactly this precedent. It normalizes the idea that governments should restrict access to privacy tools, monitor encrypted traffic, integrate databases across sectors, and treat privacy protection as a security threat rather than a right.

That precedent, once set, is nearly impossible to reverse. Future governments can argue they're just implementing the logical extension of existing policy. The infrastructure is in place. The political will has been demonstrated. The only thing left is gradual expansion.

What Should Actually Happen: Realistic Policy Alternatives

If there's a path forward that actually protects minors without destroying privacy, it looks substantially different from what France is proposing.

First, focus on the platforms. Don't restrict access or privacy tools—regulate platform design. Mandate that algorithms be opt-in rather than default. Require platforms to offer chronological feed options. Restrict micro-targeted advertising. Remove engagement metrics that drive comparison and anxiety. These changes protect everyone, not just minors, and they address the actual mechanism of harm.

Second, invest in education and family support. Digital literacy programs in schools that teach how algorithms work, how to recognize manipulation, and how to engage critically with social media build actual resilience. Family support programs that help parents understand and engage with their kids' online lives create natural safeguards better than any surveillance system.

Third, if age restrictions are genuinely desired, implement them through platforms themselves rather than through ISP-level monitoring or government surveillance infrastructure. Let platforms verify age (which they're incentivized to do anyway to reduce liability), rather than requiring government databases and deep packet inspection.

Fourth, protect privacy explicitly. Build legal frameworks that prevent government access to encrypted communications, restrict ISP monitoring, and protect privacy tool usage. Make it illegal for platforms to require biometric identification or government ID documentation for access.

Fifth, hold platforms accountable for actual harms. Don't just restrict access—regulate design and transparency. Require algorithmic accountability, independent audits, and real consequences for harmful practices.

Sixth, invest in mental health resources and support for young people. If the concern is mental health impacts of social media, the solution is mental health support, not privacy restriction.

These approaches are politically harder because they require confronting platforms' business models. They require actual regulation rather than surveillance theater. But they actually address the problem rather than pretending to while building surveillance infrastructure.

International Context: How Other Countries Are Handling This

France isn't isolated in wrestling with these questions. Governments globally are trying to figure out how to regulate young people's social media use without completely destroying privacy.

Australia passed Online Safety Bill amendments that focused on platform accountability and age verification, but explicitly rejected government-mandated VPN restrictions as legally problematic and technically infeasible.

The United Kingdom considered similar restrictions before abandoning them as contradicting their data protection framework and creating indefensible surveillance infrastructure.

Canada is exploring age verification approaches but focused on platform responsibility rather than restricting privacy tools.

South Korea has implemented some of the world's strictest age restrictions, but they're enforced at the platform level through biometric verification, not through VPN restrictions or ISP monitoring. Even that approach has faced legal challenges and significant privacy criticism.

The Netherlands has taken a regulatory approach focused on platform transparency and algorithmic accountability rather than access restrictions.

The pattern is informative: democracies that have thought through these issues carefully tend to reject VPN restrictions and government surveillance infrastructure as disproportionate and ineffective. France's approach stands out as more aggressive and less protective of privacy than other comparable democracies.

That doesn't mean France won't implement these restrictions. It means France is choosing a path that even other governments considering similar protection measures have rejected as going too far.

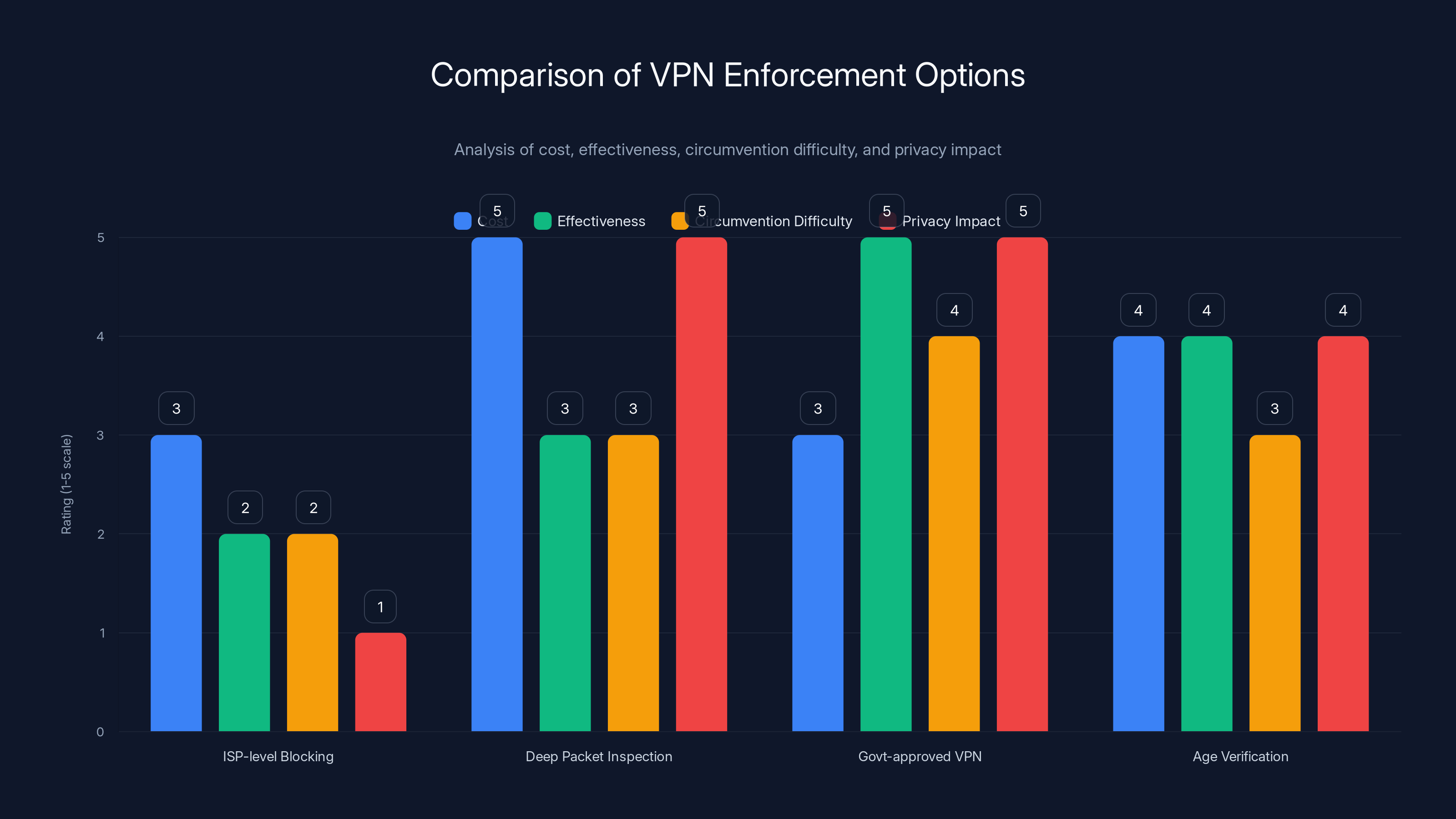

This chart compares four VPN enforcement options in France based on cost, effectiveness, circumvention difficulty, and privacy impact. The 'Govt-approved VPN' option scores highest in effectiveness but also poses the greatest privacy threat.

The Technical Reality of Enforcement: Cost, Complexity, and Ineffectiveness

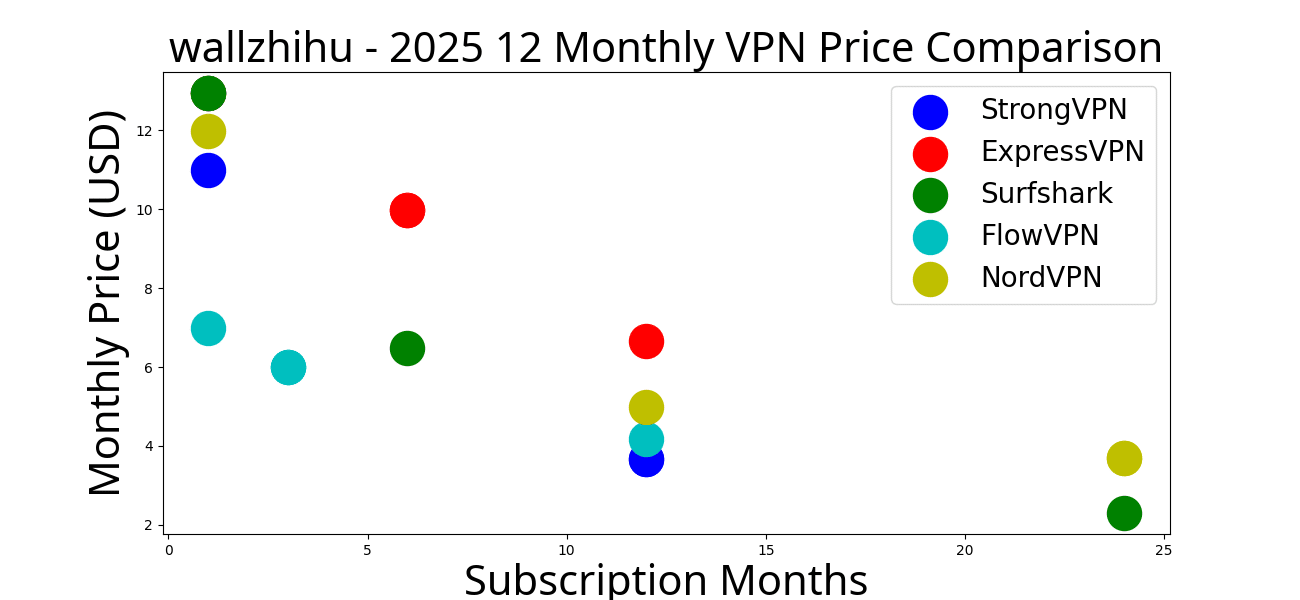

Let's get specific about what France would actually need to implement to meaningfully restrict VPN usage for minors.

Option 1: ISP-level blocking of known VPN IP addresses. This requires identifying all VPN provider IP addresses (numbering in the hundreds of thousands and constantly changing), pushing updates to blocking rules across all ISPs, maintaining the system against constant circumvention attempts, and accepting that determined users will simply find VPNs the system hasn't blocked yet or use alternative privacy tools. Cost: Moderate. Effectiveness: Low. Circumvention difficulty: Low.

Option 2: Deep packet inspection to identify and block encrypted traffic patterns consistent with VPN usage. This requires installing monitoring infrastructure on ISPs' networks, analyzing encrypted data flows to identify protocols being used, blocking traffic identified as VPN-related, and dealing with the circumvention techniques (obfuscation, protocol mixing, legitimate encrypted traffic that resembles VPN traffic). Cost: High. Effectiveness: Moderate. Circumvention difficulty: Moderate. Privacy destruction: Extreme.

Option 3: Mandatory government-approved VPN usage only, where all VPN providers must integrate with government monitoring infrastructure. This requires VPN providers to accept that they're effectively arms of government surveillance, to integrate monitoring capabilities into their systems, to maintain government-provided lists of approved endpoints, and to monitor their own users' traffic for compliance. Cost: Moderate (shifts to providers). Effectiveness: High (within the government's control). Circumvention difficulty: High legally, moderate technically (users can route around approved VPNs). Privacy destruction: Total.

Option 4: Comprehensive age verification system that requires all users under 15 to authenticate their identity and location, with government ID databases integrated with ISP systems, ISP-level monitoring of all internet usage tied to verified identities, and restrictions on service access based on age. Cost: Extreme. Effectiveness: High for identity-linked restrictions. Circumvention difficulty: Moderate (borrowing accounts, older siblings, finding unmapped services). Privacy destruction: Total and permanent.

None of these options is attractive. Options 1 and 2 are relatively inexpensive but largely ineffective. Options 3 and 4 are more effective but require unprecedented surveillance infrastructure and destroy privacy comprehensively.

If France is serious about VPN restrictions, they're looking at implementing something approximating Options 2-4. The cost is substantial. The effectiveness is partial (determined teenagers will find workarounds). The privacy destruction is total. The infrastructure, once built, will be repurposed for adult surveillance.

Global Implications: What This Means for International Tech Policy

France's proposal matters well beyond France's borders because France influences EU policy and other democracies look to France and the EU as models.

If France successfully implements VPN restrictions, it sets a precedent for the EU as a whole. Other member states will face political pressure to implement similar restrictions. You'll eventually have a patchwork of European privacy policies where some countries restrict privacy tools and others don't, creating incentive for harmonization around the most restrictive standard.

Simultaneously, the US is watching. Congress has considered various internet regulation proposals, and some legislators have looked to EU approaches as models. If the EU moves toward surveillance infrastructure, US legislation will likely follow.

Authoritarian-leaning governments get cover. When democracies implement surveillance infrastructure, autocracies can cite democratic precedent. "If France restricts VPNs, why can't we?" becomes a rhetorical argument with teeth.

Tech companies based in democratic countries face strategic disadvantage. Building privacy-protecting tools in an environment increasingly hostile to privacy protection is economically difficult. Over time, this pushes privacy-technology development to countries with different regulatory frameworks—essentially ceding leadership in privacy technology to whoever has the most permissive regulations.

More broadly, it signals a major shift in how democracies think about privacy. The narrative of privacy as a fundamental right gets replaced with surveillance as a tool for protection. That's a civilizational shift with consequences that extend far beyond teenager access to social media.

The Future: How This Plays Out Over Time

If France implements VPN restrictions and they become normalized across the EU, here's the likely trajectory:

Years 1-2: Initial implementation focuses on minors. VPN providers lobby against restrictions, some small companies exit the market. Public discussion frames this as child protection succeeding.

Years 2-5: Security researchers and privacy advocates document circumvention techniques being used by teenagers. Government argues this demonstrates the need for stronger measures (deeper monitoring, more comprehensive databases). Politicians propose expanding restrictions to older teenagers, then young adults.

Years 5-10: Age-based restrictions gradually disappear. The focus shifts from age verification to comprehensive monitoring of all VPN usage. Justifications expand: preventing terrorism, catching criminals, monitoring misinformation. Basically nobody remembers this was originally about protecting minors.

Years 10+: VPN usage becomes significantly restricted or effectively prohibited. Most citizens use only government-approved or government-monitored services. Privacy protection technology is classified as a threat to national security. Other democracies have implemented similar systems.

This isn't wild speculation. It's the historical pattern of surveillance systems. They always start with sympathetic justifications, always expand, and always end up being tools of control rather than protection.

The question isn't whether France will implement VPN restrictions. It's whether other democracies will wake up to what's being normalized before it becomes the global standard.

The Role of Tech Companies: Complicity, Resistance, or Neutrality?

Let's talk about the platforms themselves, because their role in this situation is critical and often overlooked.

Social media platforms profit from engagement. Engagement increases when algorithms optimize for emotional response rather than wellbeing. Younger users are (in terms of data collection potential and lifetime value) more valuable than older users. Restricting access to minors reduces their market. So you'd expect platforms to oppose age restrictions.

But platforms also want regulatory protection. If governments restrict platform access, the platforms are protected from liability for harm to minors. If governments require age verification, platforms have legal cover for not protecting minors as aggressively as they might otherwise.

So there's a perverse incentive structure: platforms might actually welcome age verification and access restrictions because it reduces their regulatory exposure while protecting their business model.

Regarding VPN restrictions specifically: platforms don't need to take a stance. If VPNs are restricted by governments, it happens at the ISP or government level. Platforms can claim neutrality while benefiting from reduced unauthorized access. They get the protection without the public relations cost.

What would actually challenge this? Platforms could explicitly commit to not requiring age verification, to not storing government ID information, to not integrating with government surveillance infrastructure. They could advocate for platform-level design changes (algorithmic transparency, engagement limiting, chronological feeds) that actually address harms rather than surveillance-based restrictions.

Few are doing this. Most are staying quiet because the current trajectory benefits them: governments restrict access (reducing their user base but increasing legal safety), surveillance infrastructure is built (creating barriers to entry for competitors), and nobody publicly blames platforms for building features designed to maximize engagement for minors.

What Individuals Can Do: Advocacy, Resistance, and Building Alternatives

This situation isn't inevitable. Policy change can be influenced. But it requires coordinated effort.

For individuals in France: Contact representatives. Make it clear that surveillance infrastructure is unacceptable as a solution to legitimate concerns about social media harms. Demand alternative approaches focused on platform regulation and digital literacy.

For privacy advocates and technologists: Document the implications of VPN restrictions. Build and promote privacy-protecting alternatives. Advocate for platform regulation rather than access restriction. Make it politically costly to ignore privacy implications.

For researchers: Study the actual effects of age verification systems and VPN restrictions in countries that have implemented them. Document privacy breaches, circumvention techniques, and expansion of surveillance infrastructure. Make the evidence undeniable.

For parents and educators: Instead of supporting surveillance-based solutions, support digital literacy and family engagement. Teach young people how to engage critically with social media. Create environments where they feel safe discussing online experiences.

For EU members: Push back on harmonization around France's approach. Support alternatives focused on platform regulation rather than surveillance. Make it clear that privacy is non-negotiable.

For democratic governments elsewhere: Learn from what's happening in France. Consider regulatory approaches that address actual harms (platform design, algorithmic transparency, advertising restrictions) rather than surveillance-based approaches that destroy privacy while claiming to protect children.

None of this is easy. Tech companies have significant political influence. Governments like the surveillance capability regardless of stated justification. And protecting children is genuinely sympathetic rhetoric that makes opposition seem callous.

But the alternative—normalizing surveillance infrastructure under the guise of child protection—is worse. Much worse. And it's avoidable if enough people understand what's actually being proposed.

FAQ

What exactly is France proposing regarding VPNs?

France's government, specifically Minister Anne Le Hénanff, has indicated that VPN restrictions are "the next topic on my list" as part of broader legislation to restrict minors' access to social media. While not yet formally proposed as law, this signals government intent to explore whether VPN usage can be restricted for anyone under 15, preventing them from bypassing age-verification systems on social media platforms. The proposal would likely involve ISP-level monitoring or blocking of VPN traffic, potentially requiring deep packet inspection technology.

Why would restricting VPNs actually fail to protect minors from social media?

VPN restrictions fail because determined teenagers can use alternative privacy tools (proxy servers, Tor, SSH tunnels, obfuscation protocols) that achieve similar effects but aren't technically VPNs. Additionally, VPN providers constantly rotate their IP addresses, making blocking lists obsolete quickly. The restriction creates the appearance of protection while actually just shifting teenagers toward less-detectable circumvention methods. The real issue—addictive platform design and algorithmic engagement optimization—remains unchanged regardless of whether VPNs are available.

What are the privacy implications of age verification systems for minors?

Age verification systems require collecting and storing sensitive personal data (government ID information, biometric data, financial information, or cross-referencing public records). This creates massive databases of minors' identity information that become targets for hackers. It also enables unprecedented government surveillance of which young people access which services. Once this infrastructure exists, it gets repurposed beyond its original protective intent. The systems essentially replace one form of privacy violation (circumventing restrictions) with a far larger one (comprehensive government tracking of online behavior).

How do VPN restrictions compare to what other democracies have done?

Most democracies have explicitly rejected comprehensive VPN restrictions. The UK, Canada, and Australia all considered similar approaches and concluded they're technically infeasible and legally problematic under data protection frameworks. South Korea implemented strict age verification but at the platform level rather than through government surveillance infrastructure. France's explicit focus on VPN restrictions stands out as more aggressive toward surveillance than other comparable democracies have been willing to implement.

What would actually be more effective at protecting minors from social media harms?

Effective approaches include platform regulation requiring algorithmic transparency and limits on engagement optimization, digital literacy education teaching young people how algorithms work and how to recognize manipulation, mental health support and resources available to teenagers, restricting targeted advertising to minors, removing engagement metrics that drive comparison-driven anxiety, and family support programs helping parents engage with their children's online activities. None of these require restricting privacy tools or building surveillance infrastructure, and evidence suggests they're more effective at reducing problematic social media use than access restrictions or monitoring.

Why does this matter beyond France's borders?

France influences EU policy, and other democracies look to the EU as a model for technology regulation. If France successfully implements VPN restrictions, it sets a precedent for other EU members and eventually other democracies. Authoritarian governments cite democratic precedent as cover for their own surveillance expansion. It also signals that democracies are willing to treat privacy protection as a threat rather than a right, fundamentally shifting how technology regulation evolves globally. Once surveillance infrastructure is normalized in democracies, it becomes very difficult to remove.

How can individuals actually resist or influence this policy?

Contact representatives and make clear that surveillance infrastructure is unacceptable, advocate for platform regulation and digital literacy instead of access restrictions, support research documenting privacy harms of age verification systems, teach and promote digital literacy, push for EU-level resistance to harmonizing around France's approach, and support organizations defending privacy rights. Additionally, learning about and using privacy-protecting tools normalizes their importance and makes wholesale restriction politically difficult. The key is making opposition visible and understanding that policy is influenced by constituent feedback.

What's the relationship between GDPR and France's VPN restriction proposal?

There's a fundamental contradiction. GDPR requires data minimization (collecting only necessary data), explicit informed consent, and comprehensive privacy protection. VPN restrictions necessitate age verification systems that violate all three principles: they require collecting far more data than necessary (full ID information rather than just age), they pressure-coerce consent by bundling it with service access, and they create massive databases of minors' identity information. EU legal experts have noted this contradiction, yet the EU has been largely silent on France's proposal, suggesting political reluctance to directly oppose a major member state rather than genuine acceptance of the legal framework.

Key Takeaways and Looking Forward

France's proposed restrictions on VPN usage for minors represent a critical inflection point in how democracies are willing to treat privacy and surveillance. The proposal isn't genuinely about protecting young people—other approaches would be far more effective at that goal. Instead, it's about establishing the legal and technical infrastructure for comprehensive government surveillance of encrypted communications, justified under the sympathetic banner of child protection.

The core problems are straightforward. First, VPN restrictions don't actually prevent determined access to social media—they just create incentives for using less-detectable circumvention methods. Second, restricting privacy tools doesn't solve the underlying issue (addictive platform design) that creates harm. Third, the surveillance infrastructure required to enforce restrictions gets repurposed for broader surveillance regardless of its initial justification. Fourth, once that precedent is set, it normalizes surveillance as an acceptable tool for protection, expanding inexorably beyond its original scope.

What's particularly concerning is that France is choosing this path despite more effective alternatives existing. Platform regulation, digital literacy education, family support, and actual mental health resources would address the legitimate concerns about social media harms far better than surveillance-based restrictions. That France isn't pursuing these suggests the stated goal of child protection isn't the primary motivation.

The geopolitical implications are significant. If France succeeds, other EU member states will face pressure to harmonize around similar restrictions. Authoritarian governments will cite democratic precedent as cover for their own surveillance expansion. Democracies' commitment to privacy as a fundamental right gets replaced with surveillance as a tool for control. That's a civilizational shift with consequences extending far beyond teenager access to social media.

What should concern you most: the proposal itself is concerning, but the fact that it's advancing with relatively little public resistance suggests people don't fully understand what's being normalized. Surveillance infrastructure built for minors becomes the foundation for adult surveillance. Privacy restrictions justified for protection become tools of control. And by the time this is obvious, the infrastructure is entrenched and politically impossible to reverse.

The path forward requires resisting surveillance-based "protections" while supporting genuine alternatives. It requires making clear that privacy is non-negotiable, that protecting young people doesn't require destroying privacy, and that democracies that embrace surveillance for protection are setting themselves on a path toward comprehensive government control of information access.

This isn't inevitable. Policy can change with sufficient constituent pressure. But the window for preventing normalization of these approaches is closing. Understanding what's actually being proposed—and why the alternatives are better—is the first step toward building a response.

The stakes are high. The infrastructure being discussed doesn't just affect French teenagers' ability to access social media. It fundamentally reshapes the relationship between citizens, governments, and privacy in democracies. That's worth paying attention to, regardless of where you live.

Related Articles

- France's VPN Ban for Under-15s: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why AI Image Generation Remains Uncontrolled [2025]

- Iran's Internet Shutdowns: How Regimes Control Information [2025]

- Indonesia Lifts Grok Ban: What It Means for AI Regulation [2025]

- Major Cybersecurity Threats & Digital Crime This Week [2025]

- Facial Recognition and Government Surveillance: The Global Entry Revocation Story [2025]

![France's VPN Ban for Minors: Digital Control or Privacy Destruction [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/france-s-vpn-ban-for-minors-digital-control-or-privacy-destr/image-1-1770066453711.jpg)