Why "Catch a Cheater" Spyware Apps Aren't Legal (Even If You Think They Are) [2025]

There's a moment in most relationships where trust breaks. Someone suspects infidelity, and instead of having a conversation, they reach for their phone. They google "catch a cheater app" and find dozens of options promising to reveal hidden secrets. Download this software, the ads say. Install it on your partner's phone without them knowing. Watch everything they do. Read all their messages. See everywhere they go.

It sounds like the perfect solution. And millions of people click "download."

Here's the problem: it's a federal crime.

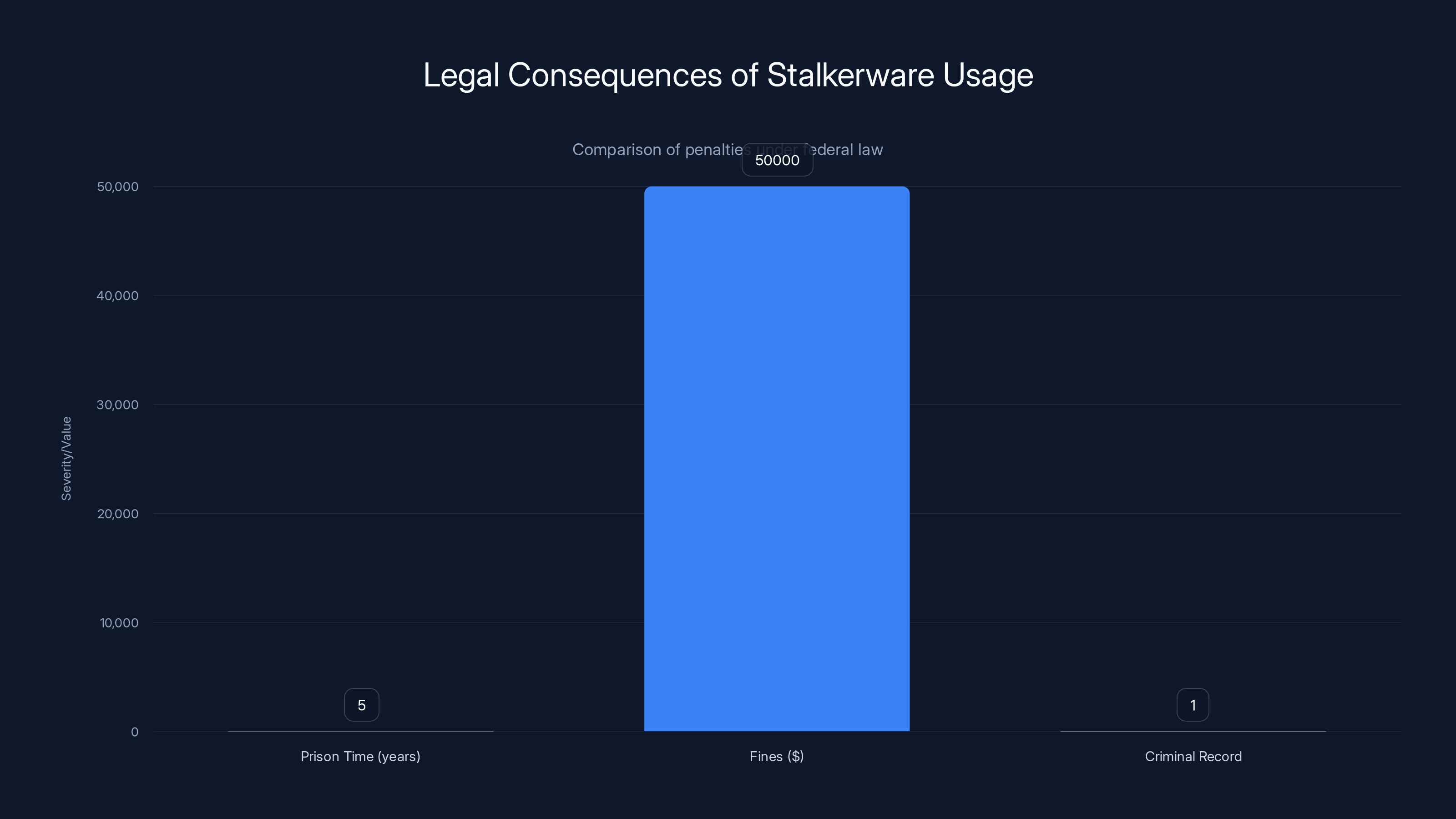

Not a legal gray area. Not a "it depends" situation. Not something that's technically illegal but nobody enforces. It's a straightforward federal offense that can result in prison time, substantial fines, and a criminal record that follows you for life.

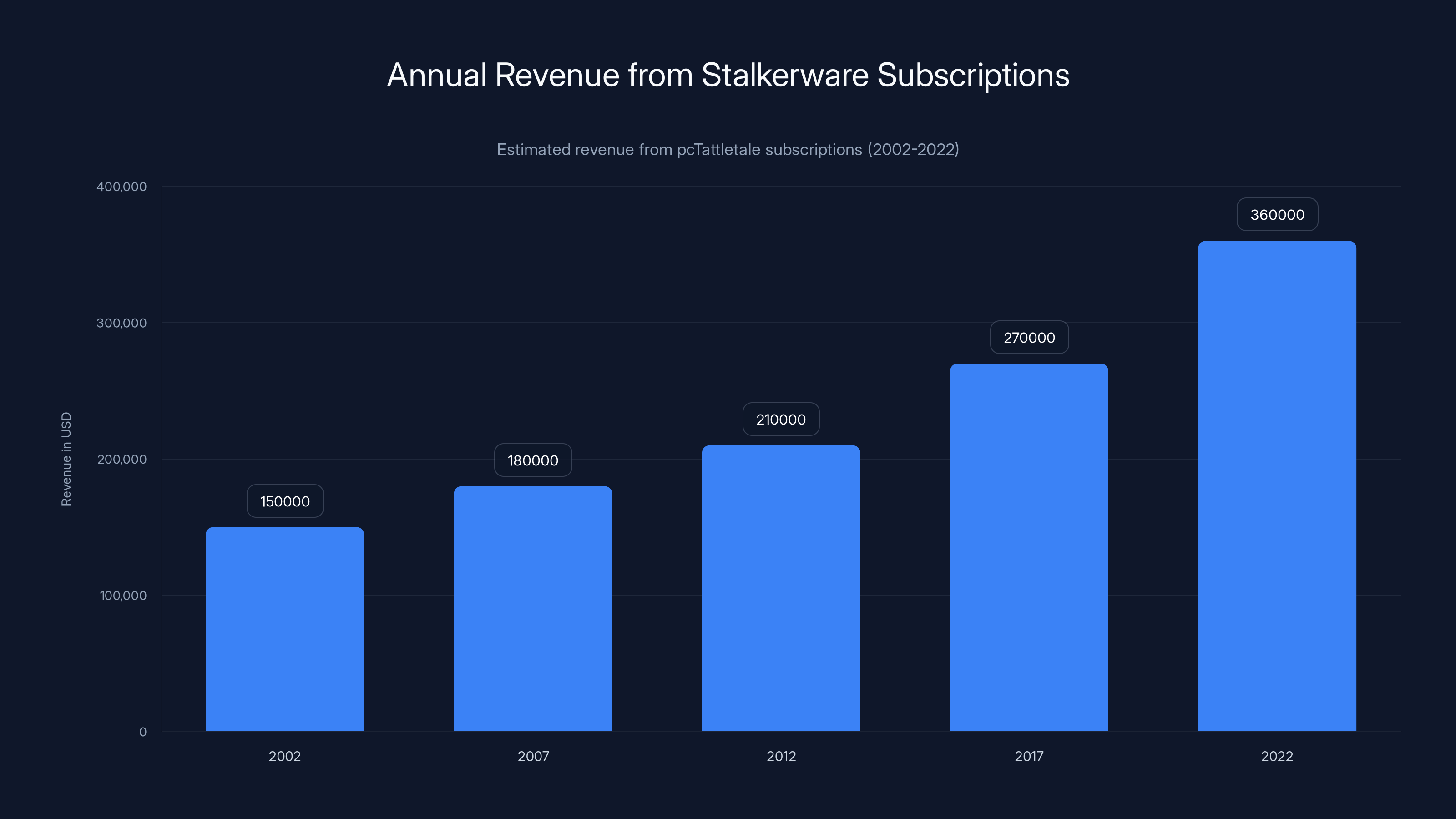

Yet the stalkerware industry thrives. Apps with names like pc Tattletale, Spy Bubble, and Flexi SPY generate millions of dollars annually by helping people spy on romantic partners, family members, and colleagues without consent. Until recently, their operators faced almost no consequences. The case of Bryan Fleming, who built and marketed pc Tattletale for nearly 25 years, shows why that's finally changing.

This article explains what stalkerware is, why it's illegal, what actually happened in the Fleming case, and what the legal landscape looks like now for anyone considering using—or operating—these apps.

TL; DR

- Stalkerware is illegal: Installing surveillance software on someone's device without their consent violates the federal Wiretap Act and Electronic Communications Privacy Act, regardless of your relationship to them

- Your intentions don't matter: Courts don't care if you suspect cheating or want to protect someone. Unauthorized surveillance is a felony

- Bryan Fleming pleaded guilty: The creator of pc Tattletale, which operated for 25 years largely without consequences, faced federal charges for knowingly marketing spyware to spy on romantic partners

- Real consequences are increasing: Federal prosecutors are actively investigating stalkerware operators, with recent convictions resulting in prison sentences and millions in fines

- The apps are still out there: Despite crackdowns, dozens of stalkerware applications continue operating, many with servers outside the US making prosecution difficult

Using stalkerware can result in up to 5 years of prison time, substantial fines, and a permanent criminal record under federal law.

What Exactly Is Stalkerware and How Does It Work?

Stalkerware is a category of surveillance software designed to monitor someone's digital activity without their knowledge or consent. Unlike legitimate monitoring tools used by parents tracking children or employers monitoring company devices, stalkerware is specifically marketed and sold for covert surveillance of adults who don't know they're being watched.

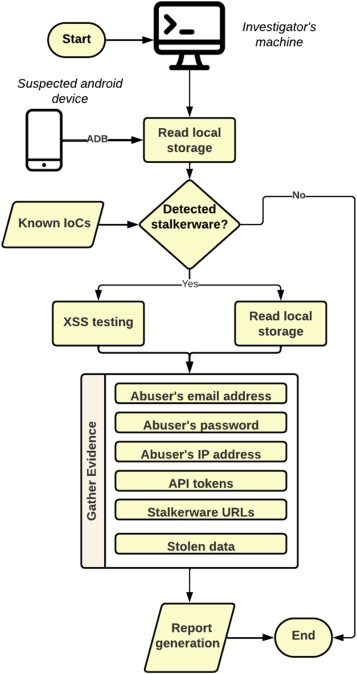

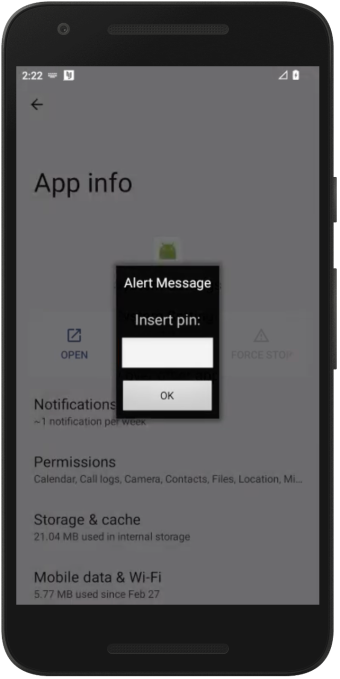

The mechanics are straightforward. A person downloads the app, installs it on someone else's device (usually by gaining temporary physical access), and then watches everything that happens on that device from a remote dashboard. The victim has no idea the software is running.

Here's what a typical stalkerware operation captures:

- Text messages and chat apps: SMS, WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal, encrypted messaging platforms

- Call logs: Who the person called, when, and for how long

- Location data: Real-time GPS tracking of the device's location

- Photos and videos: Screenshots, automatic photo capture, video recording

- Browser history: Every website visited, every search performed

- Social media activity: Posts, direct messages, friend connections

- Email: Full access to email accounts and sent messages

- Calendar and contacts: Appointments, contact information

- Keystroke logging: Every character typed on the device

Some advanced versions even activate the device's microphone and camera without the user's knowledge, creating a complete audio and video surveillance system in someone's pocket.

The apps are designed to be stealthy. Most hide their icon from the home screen and disable notifications that would alert the user to their presence. Some versions change the app name to something innocuous like "System Update" or "Device Manager." The goal is simple: the person being spied on should never know.

This is fundamentally different from parental control apps or employee monitoring software, which operate with the knowledge and consent of the person being monitored. Those tools serve legitimate purposes and operate transparently. Stalkerware operates through deception.

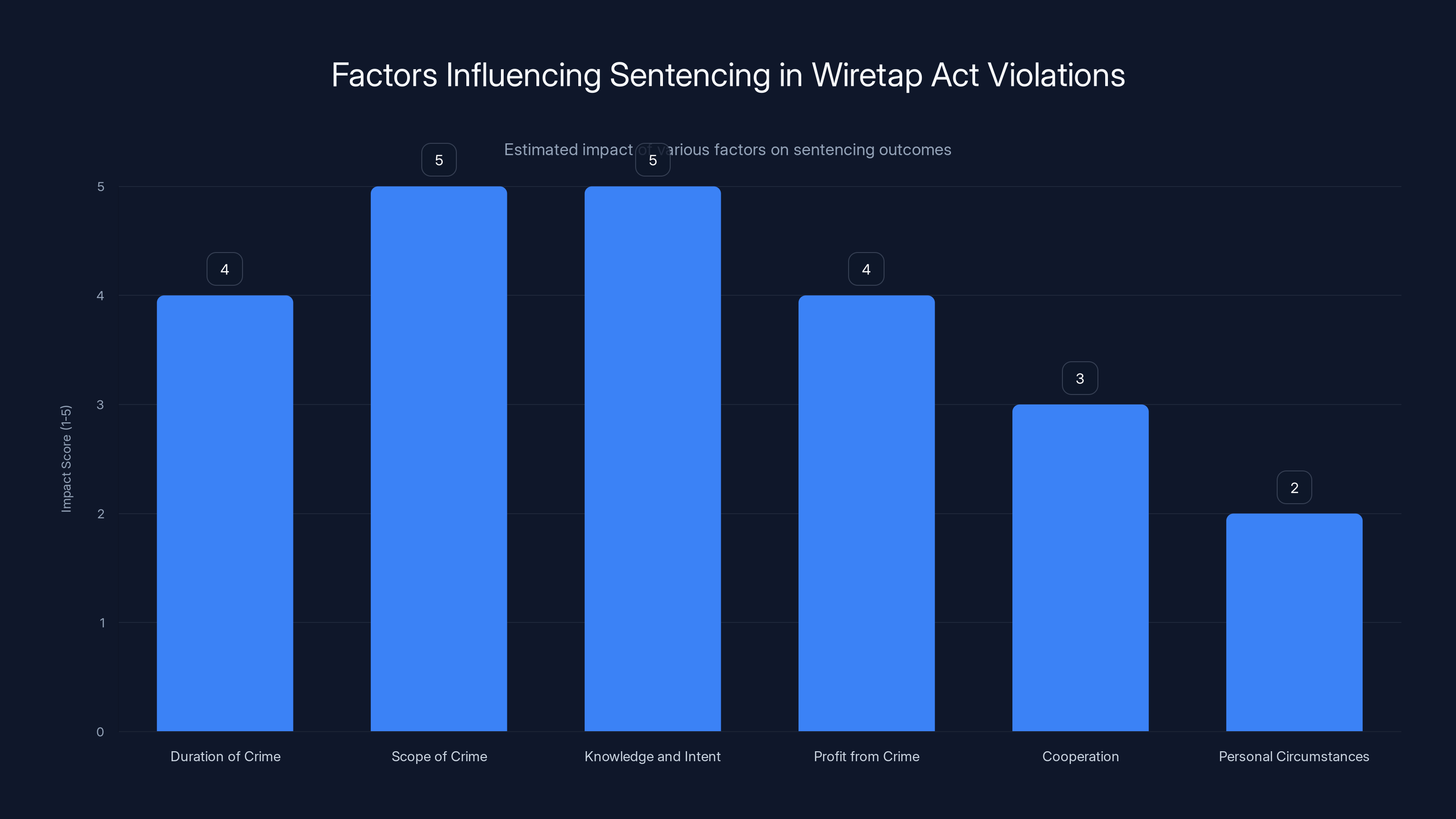

The scope of the crime and knowledge/intent are estimated to have the highest impact on sentencing decisions in Wiretap Act violations. Estimated data based on case context.

The Market for Suspicion: How Stalkerware Became a Multi-Million Dollar Industry

The stalkerware business model is ruthlessly simple: exploit relationship anxiety and insecurity, market a solution that promises to expose cheating, and charge between

Demand is enormous. People are afraid of being cheated on. They're suspicious, they're hurt, they want answers. And instead of confronting their partners or seeking professional help, they reach for technology as a shortcut to truth.

This is where apps like pc Tattletale found their market. Bryan Fleming created pc Tattletale in 2002, originally positioning it as a tool for parents to monitor their children and employers to track their employees. Those are legitimate use cases that courts have recognized as legal in certain contexts.

But somewhere along the way, Fleming realized where the real money was. His customer base shifted. The marketing changed. By 2022, the company's website featured countless blog posts with titles like "How to Catch Your Boyfriend Cheating" and "Unlock Your Husband's Phone to See What He's Doing." The app's landing pages included explicit instructions on how to install the software without the target's knowledge.

Internal emails revealed Fleming's understanding of how the app was being used. Support requests in his inbox came from people asking for help making the surveillance invisible: "Is there a way to NOT let the user know you are taking screen shots?" Another customer complained that their husband noticed when screenshots were being taken because the phone beeped. Fleming helped them figure out how to hide it.

He knew exactly what was happening. The financial records made it clear. Fleming was selling approximately 1,200 subscriptions annually at prices ranging from

And Fleming's company wasn't alone. The stalkerware industry includes dozens of active players. Flexi SPY, Spy Bubble, m Spy, Spy Era, Highster Mobile, and others operate similarly, generating tens of millions of dollars annually from surveillance-obsessed customers.

What's remarkable is how long these companies operated with almost no legal consequences. For decades, they existed in a strange zone where everyone involved knew what was happening but enforcement was practically nonexistent. The business model was openly predatory, the target population was defenseless (they didn't know they were targets), and the operators faced almost no risk.

That started to change when federal investigators began paying attention.

The Federal Investigation: How Law Enforcement Finally Caught Up

Around 2021-2022, federal investigators in California launched a coordinated investigation into stalkerware companies operating in the United States. This wasn't random. There was growing awareness within law enforcement and among digital rights advocates that an entire industry was operating with impunity, distributing tools designed specifically to violate people's privacy and autonomy.

Breaking the investigation down:

Finding the Targets: Most of the stalkerware operators being investigated were based overseas, making prosecution nearly impossible. The investigators knew they needed to find someone in the US who was actively selling these tools. Fleming was perfect. He operated out of Bruce Township, Michigan, his location was publicly listed on the company website, and he was actively maintaining and improving the software.

Building the Case: Federal investigators didn't just read blog posts and marketing materials. They went deeper. They set up their own affiliate accounts on the pc Tattletale platform and went through the process of getting marketing materials from Fleming. They accessed his email servers, finding thousands of customer support requests that proved Fleming knew exactly how his product was being used.

Those emails are devastating from a legal perspective. Customers asking Fleming how to hide the surveillance app. Fleming responding with technical assistance. Customers explicitly stating they were spying on partners without consent. Fleming helping them solve problems. This wasn't a situation where Fleming could claim he didn't know what was happening. He actively facilitated it.

Marketing to the Market: The emails also revealed something about Fleming's understanding of his customer base. In one message, he noted that pc Tattletale was "more successful when marketed at women, because there are a lot more women wanting to catch their man than the other way around." This shows Fleming wasn't just passively allowing people to misuse his tool. He was actively targeting the demographic he knew would use it for unauthorized surveillance.

The Breach: In 2024, before Fleming even faced trial, pc Tattletale was hacked. Attackers gained access to Amazon Web Services credentials stored on the pc Tattletale servers and leaked massive amounts of data, including video recordings captured by the surveillance app. Fleming later claimed the company was "out of business and completely done" following the breach. Whether that was true or a legal strategy is unclear.

Based on all this evidence, federal prosecutors charged Bryan Fleming with a single count: knowingly building and marketing software "primarily useful for the purpose of the surreptitious interception of wire, oral, or electronic communications."

This charge falls under the federal Wiretap Act, one of the nation's oldest and broadest surveillance laws.

The chart illustrates the estimated growth in annual revenue from pcTattletale subscriptions, highlighting the increasing demand for stalkerware. Estimated data.

The Legal Foundation: Why Stalkerware Violates Federal Law

There are actually multiple legal grounds for prosecuting stalkerware operations, though the primary one is the federal Wiretap Act, passed in 1968.

The Wiretap Act makes it illegal to intentionally intercept, endeavor to intercept, or procure any other person to intercept or endeavor to intercept any wire, oral, or electronic communication. This was originally designed to prevent government surveillance without warrants, but it also applies to private citizens.

Critically, there are very few exceptions. The law allows:

- Government interception with a warrant: Law enforcement can legally intercept communications with court authorization

- One-party consent: In some contexts, one party to a communication can record that communication without telling the other party

- Ordinary business communications: Companies can monitor communications on their own network for legitimate business purposes

What the law does NOT allow:

- Installing surveillance software on someone else's device: Doing this is interception

- Recording someone's private conversations without their knowledge: This is illegal in most states even with the one-party consent rule, because the person being recorded isn't a party to the decision to record them

- Accessing someone's text messages or emails: This is electronic communication interception

- Monitoring someone's location: This can violate separate statutes about unauthorized access to computer systems

There's also the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), which makes it illegal to intentionally access a computer without authorization. Installing stalkerware on someone's device could violate this statute as well.

At the state level, many jurisdictions have additional criminal stalking laws that specifically address harassment and surveillance. Some states have even passed laws specifically targeting stalkerware sales.

The key legal principle: your intention doesn't matter. You could have the best of motives. You could suspect infidelity. You could worry about your partner's safety. You could believe you're protecting yourself. None of that changes the fact that unauthorized surveillance is illegal.

This was Fleming's primary weakness in any potential defense. He couldn't argue "I didn't know what people were using this for" when his own emails showed he actively facilitated unauthorized surveillance. He couldn't argue the software had legitimate uses when his entire marketing strategy focused on catching cheating partners.

Bryan Fleming's Guilty Plea: What Actually Happened in Court

In January 2026, Bryan Fleming appeared in federal court in California and pleaded guilty to the charges against him. This is important: he didn't contest the charges, didn't go to trial, didn't claim the prosecution was unfair. He admitted that he built and marketed software specifically designed to spy on people without their consent.

Under the terms of his plea agreement, Fleming faces sentencing at a later date. At the time of his plea, he was released on his own recognizance, meaning he didn't have to post bail. But this doesn't mean the case is over. The sentencing phase is still coming, and federal judges have significant discretion in determining sentences for Wiretap Act violations.

For context on what "significant discretion" means: The statutory penalty for violating the Wiretap Act includes up to five years in federal prison and fines up to $250,000. But judges can also consider:

- Duration of the crime: Fleming operated pc Tattletale for about 25 years, though the marketing shift to "catch a cheater" use cases was more recent

- Scope of the crime: How many people were harmed? Estimates suggest pc Tattletale had tens of thousands of users over its lifetime

- Knowledge and intent: Fleming clearly knew what he was doing (the emails prove this)

- Profit from the crime: Fleming made substantial income from this activity

- Cooperation: Whether Fleming cooperated with investigators or helped expose other stalkerware operations

- Personal circumstances: Fleming's age, health, prior criminal history (if any), family situation

In recent stalkerware prosecutions, sentences have ranged from probation with no prison time to multiple years in federal prison. The varying outcomes reflect judges' different interpretations of how serious these crimes are.

What's significant about Fleming's case specifically is that it's not just a prosecution. It's a demonstration of federal law enforcement's growing capability and willingness to pursue stalkerware operators. For 25 years, Fleming operated with almost no legal risk. That era is ending.

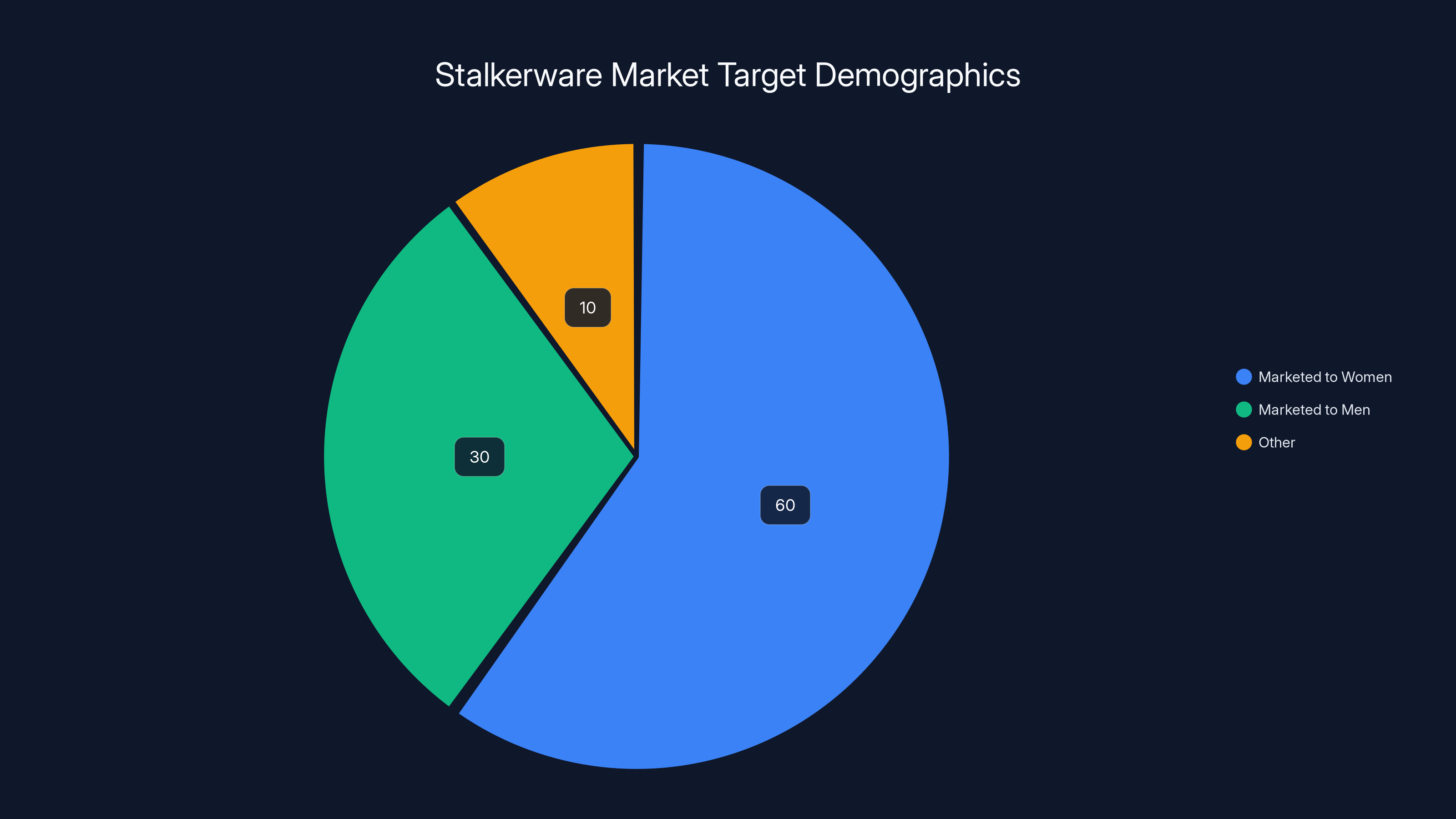

The investigation revealed that stalkerware was predominantly marketed to women, estimated at 60%, with men at 30%, and other demographics at 10%. (Estimated data)

Similar Cases: The Growing Pattern of Prosecutions

Fleming's case isn't isolated. There's been a noticeable increase in federal prosecutions related to stalkerware and unauthorized surveillance software in recent years.

The Flexi SPY Investigation: Federal agents have also targeted Flexi SPY, one of the largest stalkerware operators globally. While the U. S.-based operators are easier to prosecute, investigators have been working with international law enforcement to pursue Flexi SPY's offshore servers and financial infrastructure.

State-Level Prosecutions: Beyond federal cases, prosecutors in states including California, New York, and others have brought charges against individuals for using stalkerware to spy on intimate partners. These cases often use state-level harassment, stalking, or surveillance laws in addition to federal charges.

The Shift in Enforcement: What's changed is prosecutorial focus. For years, stalkerware was treated as a minor cybercrime or civil matter. Now, major federal task forces specifically target these operations. The change reflects growing recognition that stalkerware is used overwhelmingly to facilitate harassment, domestic abuse, and control in intimate relationships.

Research from the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative and other digital rights organizations has documented how stalkerware is frequently part of broader domestic abuse patterns. An intimate partner who installs surveillance software is often also engaging in other controlling behaviors like financial isolation, threats, and physical violence.

This context has changed how prosecutors think about stalkerware cases. It's not just a privacy violation. It's a tool of intimate partner abuse.

Why Your Reason Doesn't Excuse Your Actions: The Legal Reality

Let's be direct about something because it matters: the reason you want to spy on someone is irrelevant to whether it's legal.

You might suspect infidelity. That doesn't make it legal.

You might worry your teenager is in danger. There are legal ways to address that (transparency, open conversation, legitimate parental monitoring software with the phone in your name and the child's knowledge).

You might suspect your business partner is stealing from the company. You can't spy on their personal device, but you can hire a forensic accountant or attorney to help you investigate through legal channels.

You might fear your spouse is planning to leave and take the kids. Again, there are legal ways to address this: through attorneys, custody evaluations, and court processes.

You might think you have a right to know what your romantic partner is doing. You don't. Adults have a constitutional right to privacy. That right doesn't disappear because you're in a relationship with them.

The legal principle is consistent across all these scenarios: unauthorized surveillance is illegal regardless of motivation. The law doesn't create exceptions based on your suspicions or fears. It doesn't make an exception for people who are "just looking for the truth." It doesn't matter that you believe you have a good reason.

This is what makes cases like Fleming's so important. For 25 years, his customers could convince themselves they weren't really doing anything wrong. They were just trying to protect themselves, catch a cheater, or figure out what was going on. Fleming's marketing reinforced this rationalization. The word "spyware" wasn't even part of the common vocabulary around these tools. They were just "monitoring apps."

Now, with federal convictions and criminal prosecutions, that excuse is gone. Everyone knows: this is illegal.

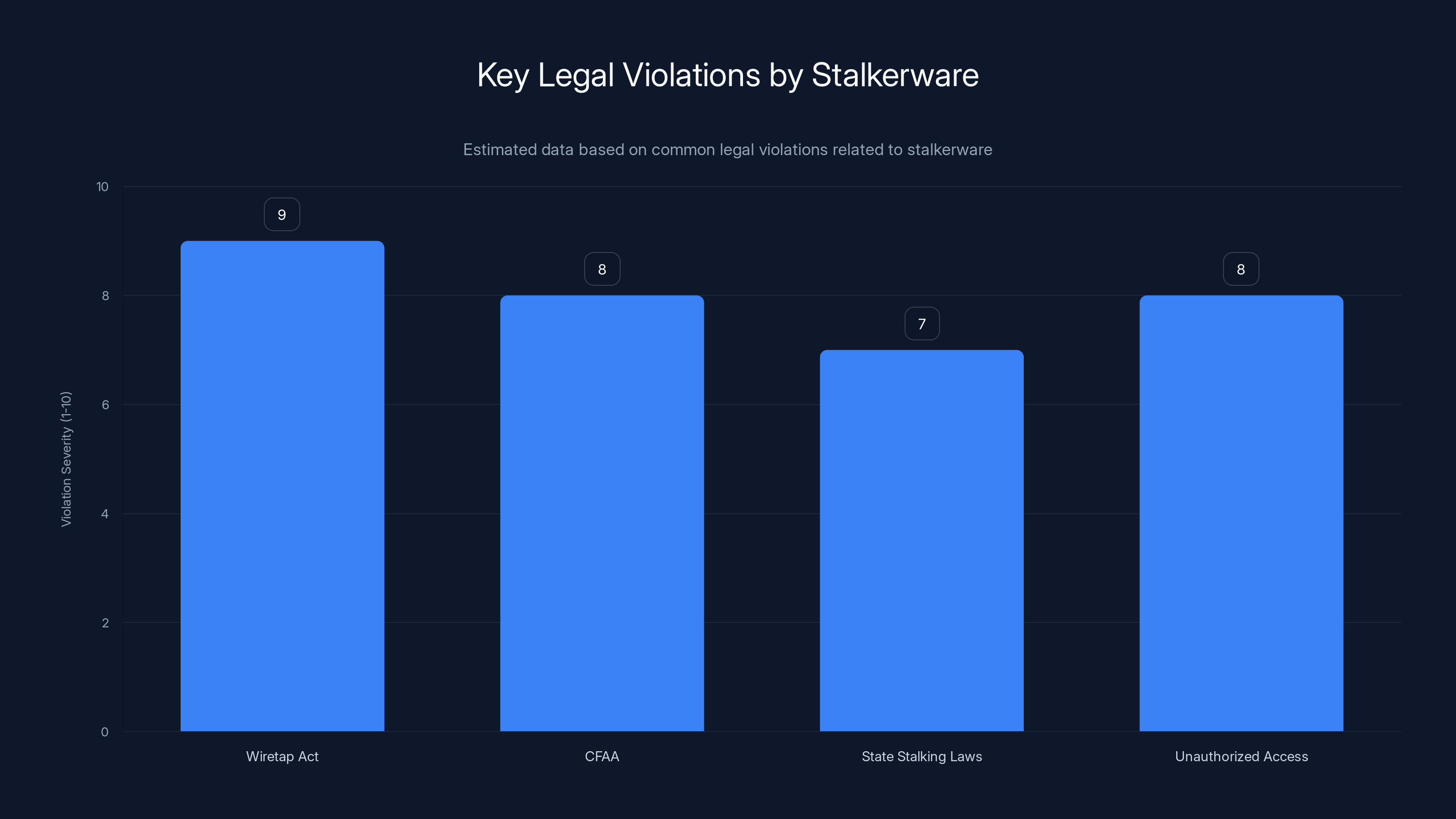

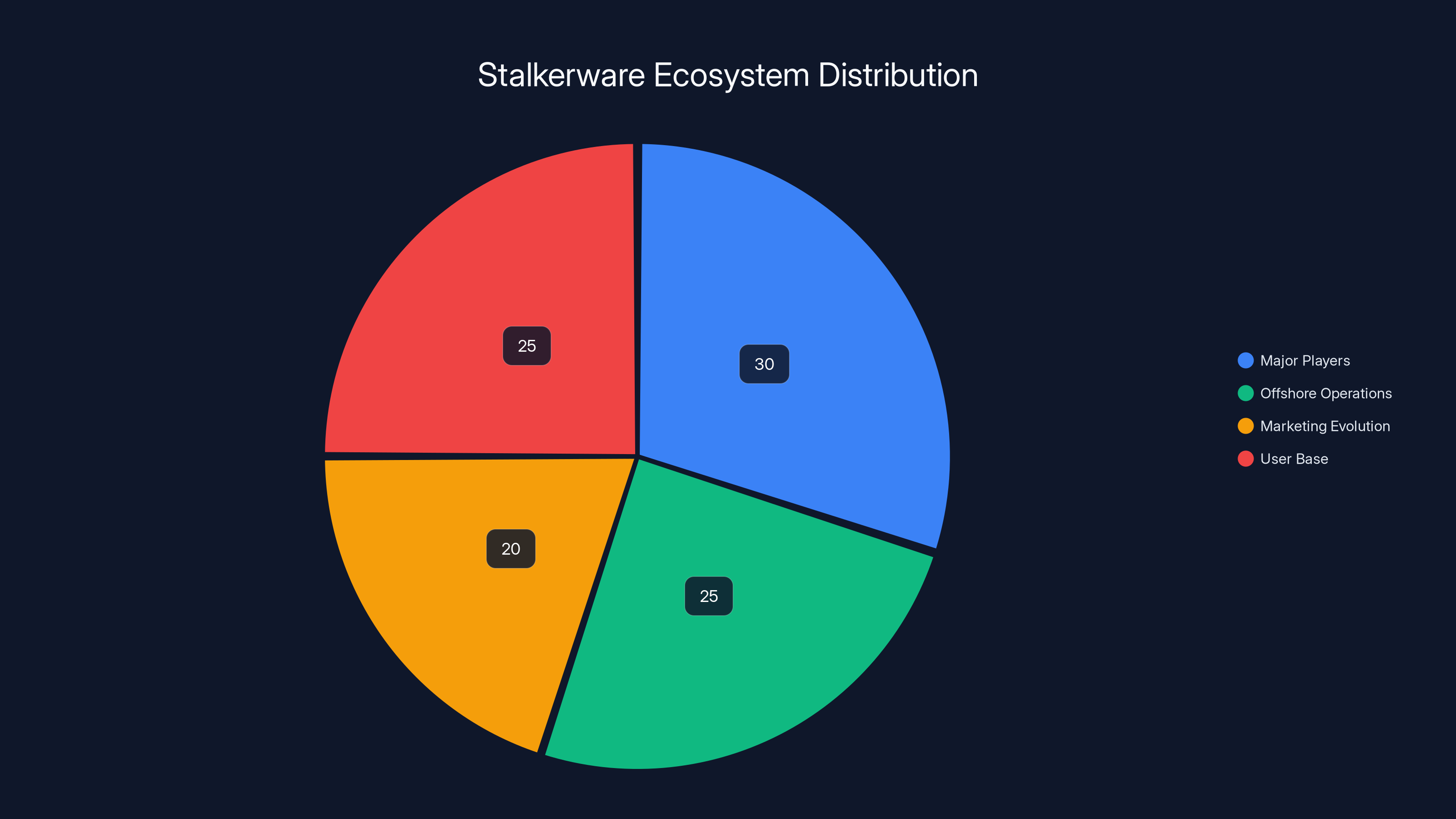

Stalkerware operations primarily violate the Wiretap Act, with significant breaches also under the CFAA and state laws. Estimated data.

The Broader Stalkerware Ecosystem: Who's Still Doing This

Despite Fleming's guilty plea and growing enforcement, dozens of stalkerware applications continue operating. The ecosystem looks something like this:

The Major Players: Apps like Spy Bubble, m Spy, Spy Era, Highster Mobile, and others continue marketing surveillance software, often with the same tactics Fleming used. Their websites feature blog posts about catching cheating partners, their ads target insecure people, and their support teams help customers install software surreptitiously.

The Offshore Strategy: Many operators have deliberately moved their servers and operations outside the United States specifically to avoid U. S. law enforcement jurisdiction. This makes prosecution more difficult but not impossible. Investigators can still pursue financial transactions, target U. S.-based affiliates, work with international law enforcement, and bring charges against U. S. citizens who use these services (yes, using stalkerware can also be a crime, not just selling it).

The Marketing Evolution: As law enforcement attention has increased, stalkerware operators have subtly shifted their marketing language. They're less likely to explicitly say "spy on your cheating boyfriend" and more likely to use euphemisms like "monitor your family" or "protect your investment." But the product is identical. The intended use case is identical. Only the marketing language has changed.

The User Base: The demand side of this equation remains constant. Millions of people continue searching for spyware apps, continue downloading them, continue trying to use them. Each one of those people is potentially committing a federal crime, though prosecution of individual users is less common than prosecution of the operators.

Law enforcement priorities typically focus on the distributors (the app makers) rather than the end users, but that could change. If prosecutors start charging individual people for using stalkerware, the legal consequences would affect not just operators but millions of customers.

The Privacy and Civil Rights Perspective: Why Stalkerware Matters Beyond Law

The legal case against stalkerware is solid. But there's also a broader privacy and civil rights argument that explains why enforcement is increasingly prioritized.

Stalkerware is a tool of control. When you install surveillance software on someone's device without their knowledge, you're not just violating their privacy. You're taking away their agency, their autonomy, their ability to make free choices about their own life.

Research on intimate partner abuse shows that surveillance and monitoring are common control tactics used by abusers. Someone who wants to control their partner might:

- Monitor their location constantly

- Read all their messages and emails

- Control who they can talk to

- Use the surveillance as evidence during arguments ("I saw you texting that person")

- Use the surveillance as a threat ("I'm always watching")

- Use the surveillance to prevent the partner from leaving (gathering information that could be used against them in custody disputes)

Stalkerware enables all of this. It's perfect for an abuser because it requires no physical presence, no ongoing interaction, just periodic checking of the dashboard to see what their victim is doing.

This is why civil rights organizations, domestic violence advocates, and privacy advocates all support aggressive prosecution of stalkerware operators. It's not just about privacy in the abstract. It's about enabling real harm to real people.

From this perspective, Fleming's prosecution isn't just a legal victory. It's a recognition that the harms caused by stalkerware are serious enough to justify federal criminal prosecution, and that those harms disproportionately affect people in vulnerable positions (overwhelmingly women in intimate relationships).

Estimated data shows that major players and user base each constitute about 25-30% of the stalkerware ecosystem, with offshore operations and marketing evolution also playing significant roles.

What About Legitimate Monitoring? Where Are the Boundaries?

Here's a natural question: if stalkerware is illegal, what about parental monitoring software? What about employee monitoring? What about Find My i Phone or Google Family Link? Aren't those also surveillance?

The difference is consent and transparency. The boundaries look roughly like this:

Legal Monitoring Scenarios:

- Parental monitoring: Parents can monitor their minor children's devices with appropriate transparency and consent. The child should know they're being monitored. The monitoring should be proportionate to the child's age and maturity level

- Employee monitoring: Employers can monitor company-owned devices and company network usage, typically with clear policies that employees know about. The key is that it's company property being monitored

- Family location sharing: Services like Find My i Phone, Google Family Link, and similar apps are legal when all participants have given informed consent and know they're using the service

- Court-ordered monitoring: Law enforcement can conduct surveillance with proper warrants and court authorization

Illegal Monitoring Scenarios:

- Spousal surveillance: Installing monitoring software on a spouse's personal device without their knowledge is illegal

- Secret monitoring: If the person being monitored doesn't know it's happening, it's illegal

- Non-consensual parental monitoring: Monitoring an adult child without their consent is illegal

- Business partner surveillance: Monitoring someone's personal device or communications without their knowledge, even if you're in business together, is illegal

The legal principle underlying all of this: the person whose device or communications are being monitored must know it's happening and must consent to it. Without knowledge and consent, it's illegal surveillance.

This is why legitimate parental control apps like Apple's Screen Time, Google Family Link, and similar services are legal. They're transparent. The child knows they're installed. The parent can monitor the device. Everyone involved has consented to the arrangement.

But if a parent secretly installed Flexi SPY on an adult child's phone without their knowledge, that would be illegal—even though the parent-child relationship exists. The key factor is consent and transparency, not the relationship.

The Technical and Practical Reality: How Hard Is It to Detect Stalkerware?

One of the frustrations people have is that stalkerware can be genuinely difficult to detect. Unlike viruses or obvious malware, stalkerware is often designed to run silently in the background, consuming minimal battery and data, showing no obvious signs of its presence.

Why It's Hard to Detect:

- Minimal resource usage: Stalkerware is built to be stealthy. It uses minimal battery, minimal data, and minimal processing power

- Hidden icons: The app can be hidden from the home screen or renamed to something inconspicuous

- No alerts: Legitimate apps often send notifications (calendar reminders, message notifications, etc.). Stalkerware typically sends nothing

- System-level access: Some advanced versions run at the system level, making them invisible to standard malware scans

- Encrypted communication: The stalkerware communicates with its servers using encryption, so network monitoring often won't detect it

How to Check for It:

If you're concerned you might be a target (perhaps you're a victim of intimate partner abuse), you can:

- Check installed apps: Go through your phone's app list and look for unfamiliar apps. Be suspicious of apps with generic names like "Device Manager" or "System Update" that actually do nothing when you tap them

- Review app permissions: Check which apps have permission to access your location, camera, microphone, and messages

- Monitor data usage: Stalkerware uses bandwidth to upload data. Check if your data usage is higher than expected

- Look at battery drain: Stalkerware might cause unusual battery drain. If your battery depletes much faster than normal, investigate

- Enable developer mode: On Android, you can enable developer mode to see more detailed system information

- Use anti-spyware tools: Several reputable security companies offer tools specifically designed to detect stalkerware, though no tool is 100% effective

- Ask your carrier: Legitimate carriers (AT&T, Verizon, etc.) might be able to identify unusual data patterns or connections

If you suspect you're being surveilled, the most important step is reaching out to trusted people—friends, family, professionals, law enforcement, or a domestic violence hotline. Stalkerware is often part of a broader pattern of abuse, and professional help is critical.

What's Next: The Future of Stalkerware Enforcement

Based on current trends, we can predict a few directions for stalkerware enforcement:

More Prosecutions: As law enforcement agencies build expertise and share information across jurisdictions, more stalkerware operators will face prosecution. The Fleming case will be cited in future cases, building legal precedent.

International Cooperation: Many stalkerware operators operate internationally. The FBI and other agencies are increasingly working with international partners (Europol, national agencies in other countries) to target offshore operations.

User Prosecutions: While most enforcement focuses on distributors, there will likely be more prosecutions of individual users, particularly in cases involving domestic violence. Using stalkerware is a crime, and prosecutors are becoming more aware of this.

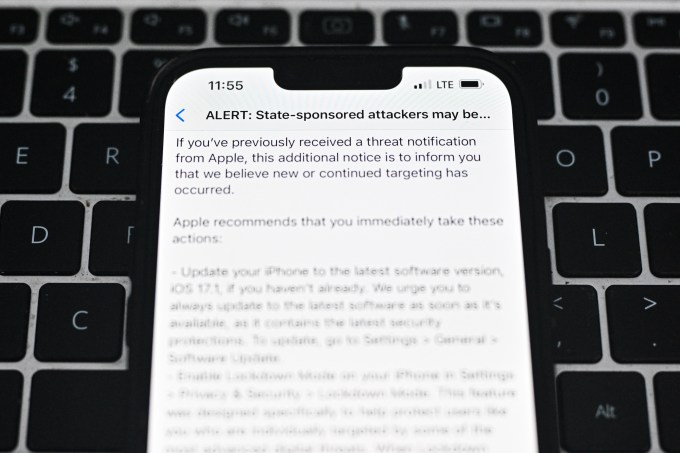

Technology Responses: Apple, Google, Microsoft, and other major tech companies are building in protections against stalkerware installation. Find My i Phone's "Air Tag detection" feature was specifically designed to alert people when unknown Apple devices are tracking them. More similar features are coming.

Legislative Updates: Several states have already passed legislation specifically targeting stalkerware. This is likely to expand as awareness grows. Some proposed legislation would make advertising stalkerware illegal, not just selling it.

Civil Lawsuits: Beyond criminal prosecution, victims of stalkerware are increasingly filing civil lawsuits against both the operators and the perpetrators. These lawsuits seek damages and can result in significant financial penalties even when criminal charges don't result in prison time.

The Fleming case accelerated this entire process. For 25 years, stalkerware operators could reasonably assume they'd never face prosecution. That assumption is now dead. Every major stalkerware operator now knows that federal law enforcement is paying attention, that prosecution is possible, and that convictions are likely.

If You've Already Used Stalkerware: What You Should Know

If you've already installed stalkerware on someone's device or used it to monitor someone, here's the legal reality:

Criminal Liability: Using stalkerware is a federal crime. You could face charges under the Wiretap Act or Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Penalties include prison time and fines. The statute of limitations for federal crimes is typically 5 years, meaning you could still be prosecuted for acts you committed years ago.

Civil Liability: The person you spied on could sue you for damages. If they can prove emotional distress, loss of privacy, or other harms, a civil court could award significant damages.

Custody and Family Law: If you're involved in any custody dispute, using stalkerware could be used against you in court. Family law judges take violations of privacy seriously and may view surveillance as evidence of unfitness as a parent.

Evidence: If you're currently using stalkerware, you should understand that your device and account history could become evidence in either a criminal or civil case. Digital forensics can recover your login information, the data you accessed, and when you accessed it.

What to Do: If you're currently using stalkerware to spy on someone, the responsible thing is to stop immediately and delete the account. If you're concerned about a relationship or a situation that led you to consider surveillance, seek help from a therapist, counselor, or attorney. If you're afraid of someone, contact law enforcement. If you're in an abusive relationship yourself, contact the National Domestic Violence Hotline (1-800-799-7233). But continuing to use surveillance software is not a solution—it's a crime.

Understanding Your Own Digital Privacy

While the Fleming case and broader stalkerware prosecutions are important, they also highlight a broader reality: most people have no idea how much their personal devices reveal about them.

Your smartphone is not just a communication device. It's a location tracker, a recording device, a document repository, a financial tool, and a window into your most intimate thoughts and relationships. The data on your phone could expose:

- Everywhere you've been

- Everyone you've communicated with

- What you're thinking and feeling

- Your health information

- Your financial status

- Your political beliefs

- Your religious affiliations

- Your sexual orientation

- Your browsing habits

- Your search history

- Your photos and videos

Stalkerware is just one threat to this data. Your information is also targeted by hackers, exploited by companies for profit, accessed by law enforcement with varying levels of legal authorization, and vulnerable to data breaches.

Protecting yourself requires:

- Strong passwords and two-factor authentication: Making it harder for unauthorized people to access your accounts

- Regular updates: Keeping your operating system and apps current to patch security vulnerabilities

- Privacy settings: Understanding and configuring what permissions you're giving to apps

- Backup security: Using encrypted backups to protect your data

- Basic awareness: Understanding that your device contains sensitive information and treating it accordingly

- Relationship awareness: Recognizing red flags in relationships (excessive suspicion, controlling behavior, monitoring) early

None of this is foolproof, but it all helps.

The Bigger Picture: Trust, Technology, and Relationships

What the stalkerware industry ultimately represents is a failure of human connection and trust. People use these apps because they don't trust their partners. They don't feel safe asking direct questions. They don't have the communication skills or emotional resources to address relationship concerns head-on.

Stalkerware offers a technological shortcut that avoids the messy, uncomfortable work of actually talking to someone about relationship concerns.

But technology can't fix relationship problems. Surveillance can't create trust. Monitoring everything your partner does won't make you feel secure—it typically does the opposite, creating anxiety, suspicion, and paranoia. As one research participant in a study on surveillance and relationships put it: "I thought if I could just see what he was doing, I'd feel better. But the more I saw, the worse I felt."

This is the real tragedy of stalkerware. It preys on people's legitimate relationship anxieties while offering a solution that actually makes things worse.

If you're suspicious in a relationship, that's worth exploring. But the exploration should involve honest conversation, professional counseling, or ending the relationship if trust is truly broken. Using hidden surveillance software is not a path to a healthy outcome.

How to Report Stalkerware or Get Help

If you're being targeted by stalkerware, you have options:

Law Enforcement: Contact your local police department or the FBI. Stalkerware use is a federal crime, and law enforcement takes these cases seriously, especially when there's a pattern of harassment or domestic abuse.

The FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center: You can file a complaint at ic 3.gov. The FBI uses these complaints to identify patterns and target major operators.

Domestic Violence Resources: If stalkerware use is part of a pattern of abuse, contact the National Domestic Violence Hotline (1-800-799-7233). They can help you develop a safety plan and access local resources.

Cybersecurity Professionals: Some security firms and nonprofit organizations offer free or low-cost services to help people remove stalkerware from their devices.

Legal Help: An attorney specializing in digital privacy or family law can advise you on both criminal reporting and civil legal action.

The key thing: don't try to handle this alone. Stalkerware use is often part of a larger pattern of control and abuse, and getting professional help is critical both for your safety and for building a case.

FAQ

What is stalkerware and how does it differ from legitimate monitoring apps?

Stalkerware is surveillance software installed on someone's device without their knowledge or consent, typically designed to capture private communications, location data, and digital activity. The key distinction from legitimate monitoring apps like parental controls is consent and transparency. Legitimate monitoring tools operate with the knowledge and agreement of the person being monitored, while stalkerware specifically hides itself and operates covertly. Stalkerware makers actively market their products for spying on romantic partners without their knowledge, which is fundamentally different from parents monitoring minor children's devices with appropriate transparency.

Is using stalkerware actually illegal, or is it just a gray area?

Using stalkerware is unambiguously illegal under federal law, specifically the Wiretap Act and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. This isn't a gray area. Both installing stalkerware on someone's device and selling stalkerware with knowledge of its intended use are federal crimes that can result in prison time (up to 5 years), substantial fines, and a permanent criminal record. The case of Bryan Fleming, who pleaded guilty to federal charges after operating pc Tattletale for 25 years, demonstrates that law enforcement is actively prosecuting these cases.

What happened to Bryan Fleming and pc Tattletale?

Bryan Fleming created pc Tattletale in 2002, originally marketed as parental monitoring and employee tracking software. By 2022, the company had shifted its marketing almost entirely to "catch a cheater" use cases, with explicit instructions on how to install the app without the target's knowledge. Federal investigators in California built a case based on customer support emails showing Fleming knew how his product was being used, financial records showing millions in revenue from these surveillance sales, and marketing materials specifically targeting people who wanted to spy on romantic partners. Fleming pleaded guilty in January 2026 to violating the federal Wiretap Act and awaits sentencing. He faced potential prison time and substantial fines.

If I suspect my partner is cheating, isn't using stalkerware justified?

No. Your suspicion, however valid it might be, does not make unauthorized surveillance legal. The law is clear that the person being monitored must consent to that monitoring. There are legal approaches to relationship concerns: having a direct conversation with your partner, seeking couples counseling, consulting with an attorney, or ending the relationship if trust is broken. Using hidden surveillance software is not only illegal (a federal crime), it also typically makes relationship problems worse rather than better, and it establishes a pattern of deception and control that compounds the original trust breach.

How can I detect if stalkerware is installed on my phone?

Detecting stalkerware is challenging because it's designed to run invisibly, but you can check for several warning signs: unfamiliar apps with generic names (like "Device Manager" or "System Update"), unusual battery drain, higher-than-normal data usage, apps with suspicious permission requests, or your phone running slowly. You can review installed apps in your phone's settings, check app permissions, and use anti-spyware tools from reputable security companies. If you suspect you're being monitored, especially in the context of an abusive relationship, contact law enforcement or the National Domestic Violence Hotline (1-800-799-7233) rather than trying to investigate alone.

What should I do if I've already used stalkerware to spy on someone?

You should immediately stop using it and delete your account. Using stalkerware is a federal crime with potential prison time and fines. Continuing to use it increases your criminal liability and could result in prosecution. If the person you were monitoring discovers this, they could file a police report. You might also face civil lawsuits. If you're concerned about a relationship or situation that led you to consider surveillance, seek help from a therapist or counselor. If you used stalkerware as part of a pattern of controlling behavior, professional mental health support is important for addressing those issues.

Are there any legal ways to monitor my spouse or partner's activity?

No, not without their explicit knowledge and consent. Adults in relationships have a constitutional right to privacy. The only exception would be if your spouse explicitly consented to shared monitoring (like Find My Friends on i Phone with mutual knowledge and agreement). Attempting to monitor your spouse's device or communications without their knowledge and consent violates federal law. If you have concerns about infidelity or financial issues, legal approaches include direct conversation, couples counseling, hiring a private investigator (which operates with different legal constraints and transparency), consulting a family law attorney, or ending the relationship.

What are the criminal penalties for using or selling stalkerware?

Violating the federal Wiretap Act carries penalties of up to 5 years in federal prison, fines up to $250,000, or both. Violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act can result in similar penalties. In addition to federal criminal charges, you could face state charges for stalking or harassment, which vary by jurisdiction but typically carry additional prison time and fines. Beyond criminal penalties, victims of stalkerware can pursue civil lawsuits for damages, potentially resulting in substantial financial liability. If stalkerware use is connected to child custody disputes, it can negatively impact custody determinations.

Is law enforcement actively investigating stalkerware companies?

Yes. Federal law enforcement agencies, particularly the FBI, have launched coordinated investigations into stalkerware operations. Recent years have seen increased prosecutions of stalkerware operators and users. The Fleming case is part of this broader trend of enforcement. While most operators based overseas are harder to prosecute, U. S.-based operators are increasingly at risk. As awareness of these crimes increases, both federal and state prosecutors are prioritizing stalkerware cases, particularly when they're connected to intimate partner abuse.

What makes something a federal crime versus just a privacy violation?

The Wiretap Act specifically makes it a federal crime to intentionally intercept private wire, oral, or electronic communications. Using stalkerware to intercept someone's text messages, emails, or other electronic communications falls squarely under this federal statute. This is why Fleming's case was prosecuted as a federal crime rather than a simple privacy violation. Federal prosecution also provides access to resources and expertise that can pursue complex cases involving digital surveillance and interstate commerce (since the internet is involved).

The Bottom Line: Why This Matters

The case of Bryan Fleming and the broader crackdown on stalkerware represent a crucial moment in digital privacy and criminal law. For decades, an entire industry operated openly and profitably from selling tools designed to violate people's privacy and autonomy, and virtually no one faced consequences.

That's changing. Federal prosecutors now understand that stalkerware is a serious crime. Technology companies are building in protections against installation. Victims are increasingly pursuing both criminal and civil remedies. And operators who thought they could hide behind the excuse that "parents and employers use similar software" are discovering that the law makes sharp distinctions between transparent, consensual monitoring and covert surveillance.

The broader lesson applies to all of us. Our smartphones contain intimate details of our lives. That data is valuable, vulnerable, and worth protecting. But the protection has to come from legal, ethical frameworks—not from giving ourselves over to surveillance anxiety and technological shortcuts that seem like solutions but are actually crimes.

If you're in a relationship where you feel compelled to monitor your partner, that's a sign something fundamental is wrong. Maybe it's infidelity. Maybe it's your own insecurity. Maybe it's a partner's controlling behavior. But surveillance isn't the answer. Conversation, counseling, or ending the relationship are the real solutions.

And if you're the one being monitored, you're not overreacting. You're not paranoid. Stalkerware is real, increasingly common, and serious. Getting help is important.

Flemi's guilty plea sends a clear message: law enforcement can and will pursue stalkerware operators. That message needs to reach the millions of people still using these apps, still downloading them, still convinced they have justifiable reasons to spy on their partners. You don't. It's illegal. The consequences are real. And there are better ways forward.

Key Takeaways

- Stalkerware violates the federal Wiretap Act and Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, making it a felony with sentences up to 5 years and $250,000 in fines

- Bryan Fleming's guilty plea for operating pcTattletale marks a turning point in law enforcement's prosecution of stalkerware operators after 25 years of the company operating with impunity

- Your reason for surveilling someone (suspicion of cheating, protective concerns) is legally irrelevant—unauthorized monitoring is a crime regardless of motivation

- Stalkerware is often used as part of broader intimate partner abuse patterns, making it a civil rights issue as well as a legal one

- Federal investigators are actively targeting stalkerware companies and users, with coordinated operations already resulting in convictions and more prosecutions expected

![Why "Catch a Cheater" Spyware Apps Aren't Legal (Even If You Think They Are) [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-catch-a-cheater-spyware-apps-aren-t-legal-even-if-you-th/image-1-1767911898316.jpg)