The Moment AI Stepped Into the Courtroom

In late 2024, something shifted in how the world views artificial intelligence. It wasn't a breakthrough in reasoning or a new model release. Instead, it was quieter, more unsettling: two men were dead in South Korea, and their killer allegedly left behind a digital trail of questions asked to Chat GPT.

The case itself is brutal. A 38-year-old man in Busan confessed to murdering two acquaintances, then dismembering their bodies. But here's what made this investigation notable: prosecutors didn't rely on security footage or witness testimony alone. They traced his searches through Chat GPT, looking at the exact questions he posed to the AI. The conversation history became exhibits A, B, and C.

This is the first major criminal investigation in the world where an AI conversation history serves as central forensic evidence. And it raises questions that courts, governments, and tech companies have been avoiding for years. If you ask Chat GPT how to dispose of a body, does that reveal intent? Can Open AI be compelled to hand over your chat logs? What happens to digital privacy when AI becomes a witness?

The case exposes a strange gap in how we've regulated technology. We've built these systems to be helpful, harmless, and honest. But we haven't really thought through what happens when they become evidence in a murder trial.

Let's dig into what this case actually reveals, why it matters more than you might think, and what's likely to happen next in the collision between artificial intelligence and the legal system.

TL; DR

- South Korea's landmark case: A confessed double murderer's Chat GPT search history became central evidence in the first major criminal prosecution involving AI conversation logs

- The investigative shift: Prosecutors moved beyond traditional forensics to analyze what questions were asked to Chat GPT, treating the AI system as a digital record of intent and planning

- Privacy implications: The case raises urgent questions about whether users have reasonable expectations of privacy in AI conversations and whether companies must preserve or disclose chat histories

- Legal precedent at stake: Courts worldwide are watching this case to determine how AI conversations will be treated in future prosecutions, potentially affecting millions of users

- Broader implications: This case signals a new era where AI usage patterns become investigable, discoverable, and admissible in courtrooms globally

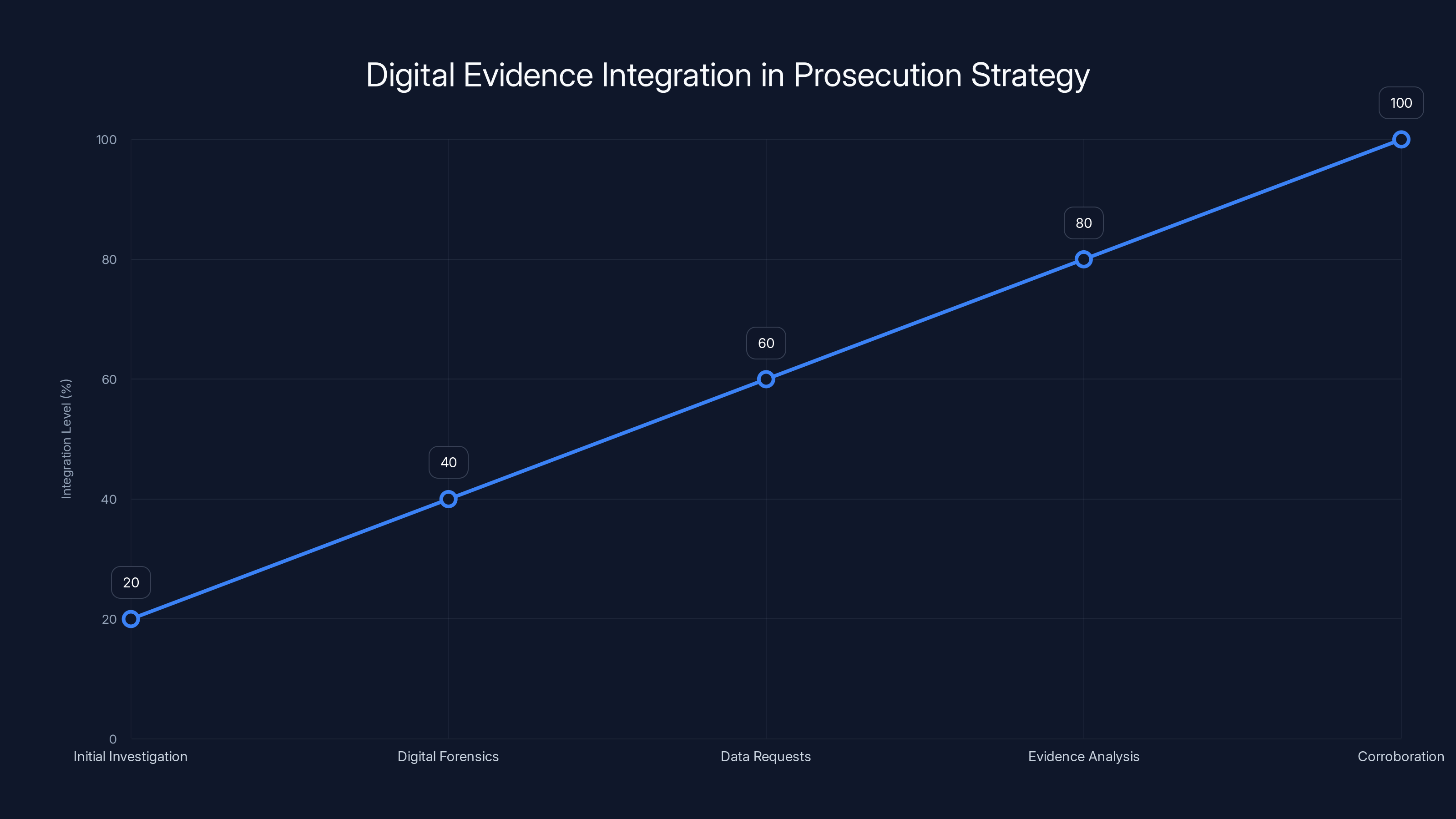

Estimated data shows increasing integration of digital evidence in prosecution strategies, highlighting a trend towards comprehensive digital case building.

What Happened: The Busan Double Murder Investigation

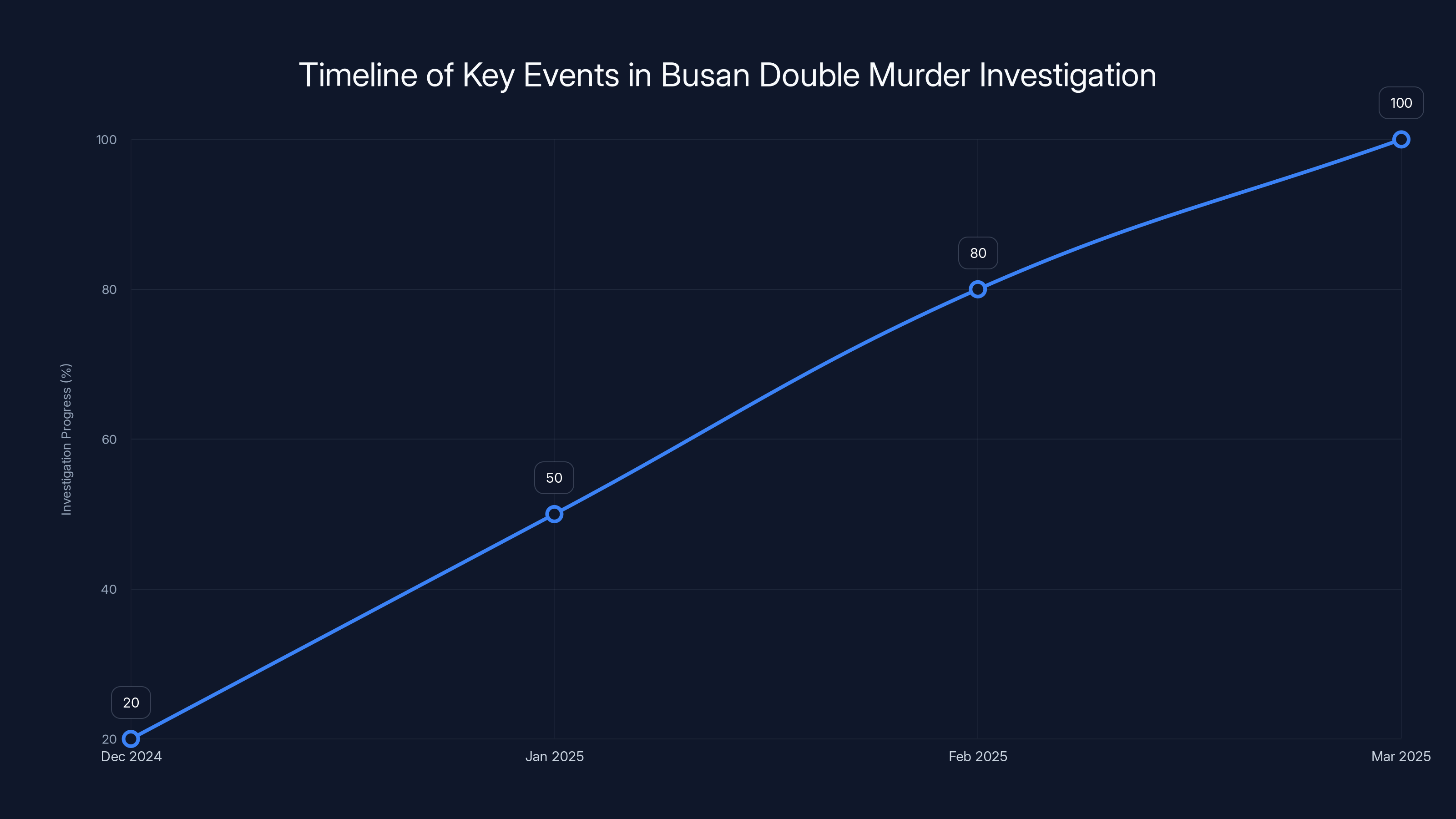

The facts are grim. In December 2024, investigators in Busan uncovered a double homicide that revealed a disturbing pattern: a suspect had allegedly used Chat GPT to research methods that would later be employed in the crimes.

The victim statements, the confession, and the timeline painted a clear narrative: premeditation. But how do you prove premeditation when there's no written diary, no recorded phone calls between conspirators? This is where the digital footprint became crucial.

When detectives obtained the suspect's device information and cross-referenced it with Open AI's user data, they found something that most murder investigations before 2025 would never have considered: a series of questions asked to Chat GPT that appeared directly related to the planned crimes.

This wasn't the suspect asking Chat GPT "how do I get away with murder?" in those exact words. That would almost be too obvious. Instead, prosecutors alleged he posed a series of technically framed questions that, when assembled together, suggested he was researching the logistics of a specific illegal act.

The investigation team worked with South Korean law enforcement authorities to obtain a legal warrant for Open AI to preserve and disclose the relevant chat logs. Open AI, as a U.S.-based company, had to navigate the complexity of a South Korean prosecution request while maintaining its privacy commitments to users. They eventually complied with what appears to have been a lawful warrant process.

This marked a crucial inflection point. For the first time in a major criminal case, an AI conversation platform was functioning as something analogous to a digital crime scene investigator, and the suspect's own words to a machine became admissible evidence of his mental state and intentions.

The confession, combined with the Chat GPT evidence, made the legal case more airtight. But it also opened a Pandora's box of questions about surveillance, privacy, and how AI platforms sit at the intersection of free speech and criminal investigation.

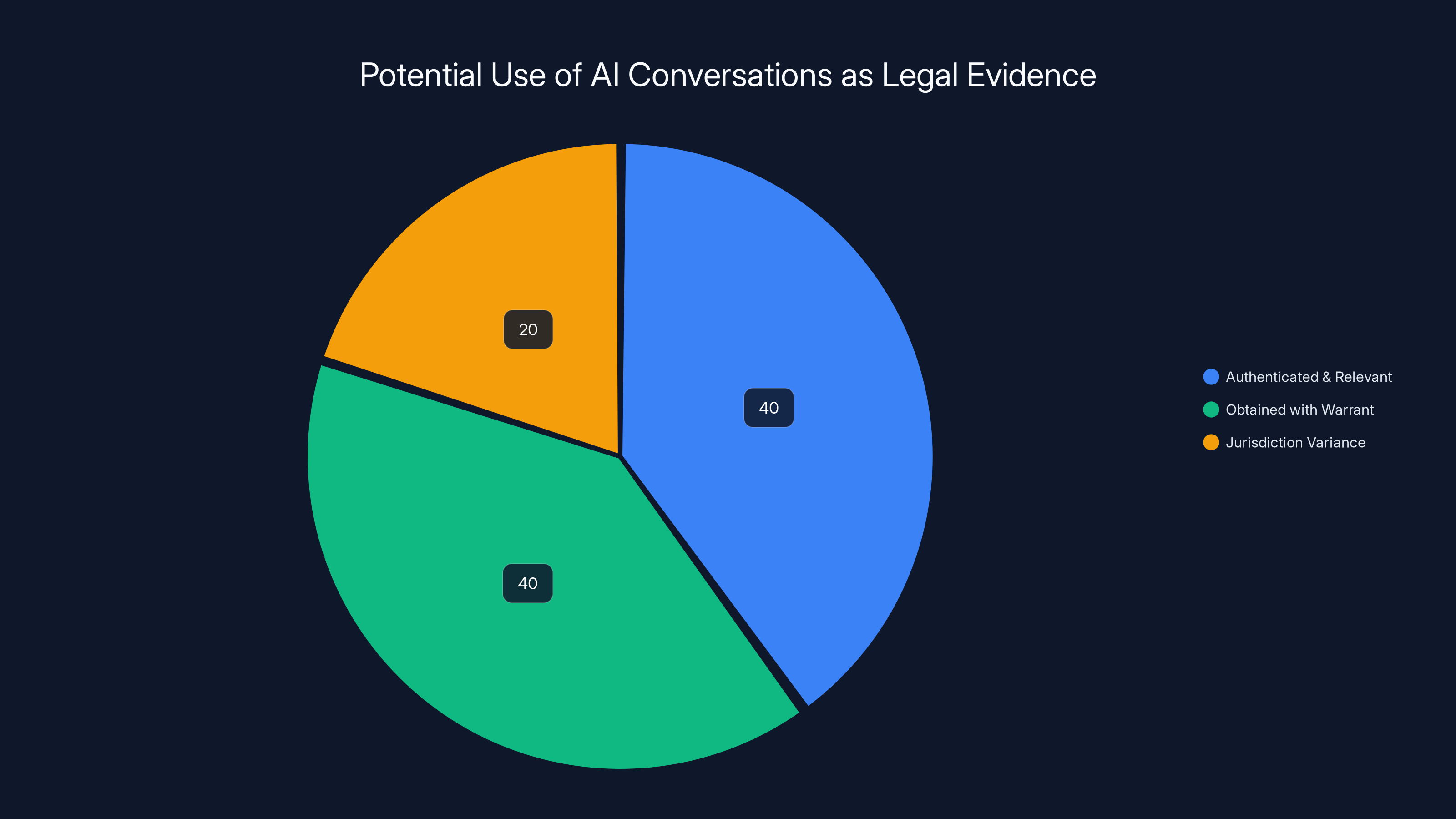

AI conversation logs can be used as evidence if authenticated, relevant, and obtained with a warrant. Jurisdictional differences may affect admissibility. Estimated data.

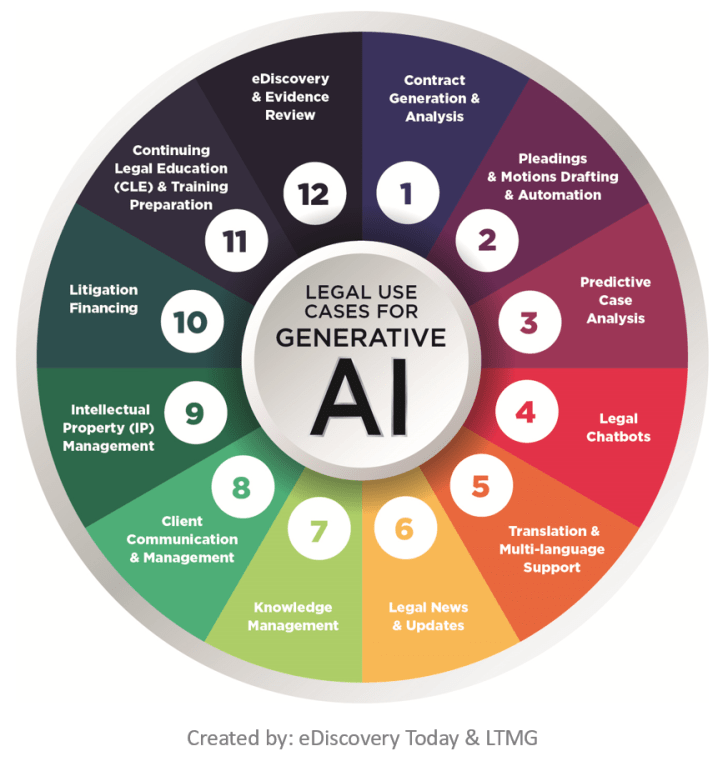

The Legal Framework: How AI Evidence Gets Admitted

In the United States and most common law jurisdictions, evidence is generally admissible if it's relevant and its probative value isn't substantially outweighed by a danger of unfair prejudice. But AI conversation logs sit in an unusual zone. They're not quite like email, because there's no expectation of communication with another human. They're not quite like search engine queries, because the AI is engaging in something closer to a dialogue.

South Korea's legal system had to make a novel determination: are Chat GPT logs admissible as evidence of state of mind, intent, or planning? The answer, based on this case, appears to be yes, provided proper legal process is followed.

The court examined several factors:

Relevance and authentication: Could prosecutors demonstrate that the logs were genuine, unaltered, and actually generated by the defendant's account? Open AI's infrastructure makes this relatively straightforward. The platform logs every interaction with timestamps, IP addresses, and user account information. When Open AI produces these records through the proper legal channels, courts can verify their authenticity.

Probative value versus prejudicial effect: Does showing that someone asked an AI system for information about a particular topic prove anything meaningful? This is thornier. Asking Chat GPT "how to hide evidence" doesn't necessarily mean you're hiding evidence. But when combined with other evidence (confessions, forensic analysis, witness testimony), the chat log becomes probative of intent.

Privacy and reasonable expectation: Users might assume their Chat GPT conversations are private. But terms of service disclaim this. Open AI can read, review, and retain user data for safety purposes. There's no encryption end-to-end in Chat GPT's standard interface. The South Korean court found that users couldn't claim a reasonable expectation of privacy that would shield these logs from lawful warrants.

This is where it gets complicated for the broader technology landscape. If you're using Chat GPT on your phone, thinking you're having a private conversation with an AI assistant, the law now suggests otherwise. Your words aren't privileged. They're stored. They can be obtained through legal process. And they can be used against you.

That's fundamentally different from the assumptions most people make when they use the service.

The Prosecution's Strategy: Building a Digital Case

Prosecutors in Busan took an approach that will likely be copied in future cases. They didn't lean on the Chat GPT evidence as the sole basis for conviction. Instead, they wove it into a larger narrative.

The investigation followed this arc:

1. Initial investigation and device seizure: When bodies were discovered and a suspect identified, law enforcement obtained a warrant to examine the suspect's devices. Like most modern investigations, this was routine.

2. Digital forensics: Investigators found evidence on the suspect's phone and computer, including browsing history, messaging apps, and account information. This is where they spotted account activity associated with Chat GPT.

3. Third-party data requests: Because Chat GPT conversations are stored on Open AI's servers, not just on the device, prosecutors needed Open AI's cooperation. They issued a legal request (the exact form likely a mutual legal assistance treaty request, given the U.S.-South Korea relationship) for Open AI to preserve and produce the relevant chat logs.

4. Evidence analysis: Once obtained, prosecutors reviewed the chat logs for relevance. They didn't publish the full contents (privacy for the defendant, interestingly), but they highlighted specific questions that appeared to relate to the crimes.

5. Corroboration: The chat logs didn't stand alone. They were combined with the suspect's confession, forensic evidence from the crime scene, and other investigative findings. The AI evidence became one piece of a larger puzzle that portrayed premeditation and planning.

This strategy is smart from a prosecutorial standpoint. It's also concerning from a civil liberties angle. Because once you've established that AI conversations can be evidence, every law enforcement agency with a warrant will start requesting them. Every AI platform will face pressure to comply. And every user will need to reconsider what they say to these systems.

The approach also highlights something subtle: the prosecution didn't need to prove that the suspect was actually trying to get away with something when he asked Chat GPT his questions. They just needed to show that someone searching for that information, combined with the fact that similar crimes were later committed, suggested planning and intent.

This is how digital evidence works in most modern cases. It's circumstantial, but it's compiling, and it's damning.

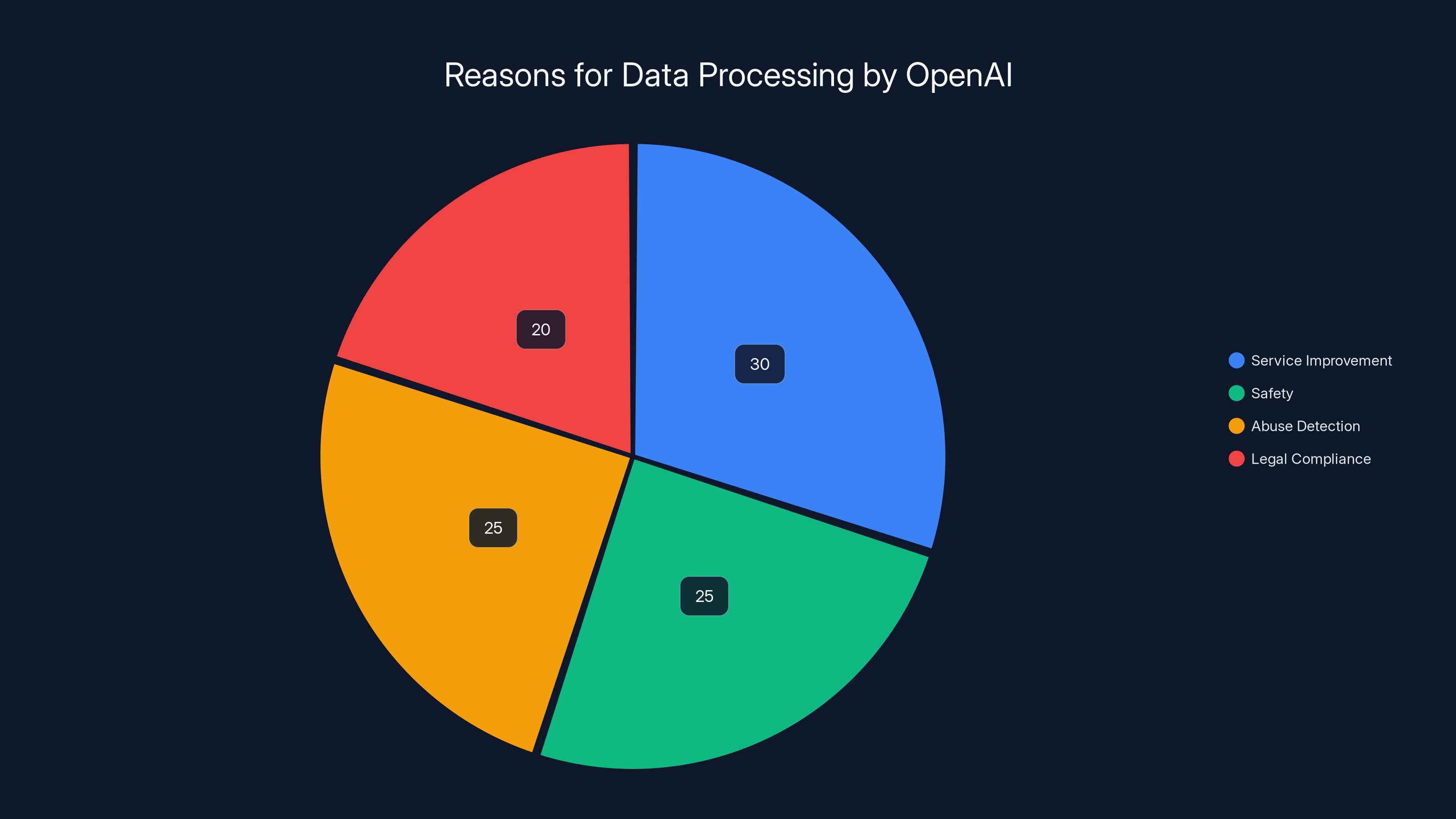

OpenAI processes user data for various reasons, with service improvement and safety being the primary purposes. Estimated data based on policy description.

Privacy Implications: What You Don't Know About Your AI Conversations

Here's what most Chat GPT users don't realize: your conversations with the AI are not encrypted end-to-end. They're not anonymous. They're not truly private in the way you might assume.

When you log into Chat GPT, you're authenticated through your account. Open AI knows who you are (or at least who you claim to be). Every message you send is routed through Open AI's servers. Every response is logged. The system records timestamps, IP addresses, device information, and the full conversation.

Open AI's privacy policy is transparent about this. They state that they process and store user data for:

- Service improvement and safety

- Abuse detection and prevention

- Legal compliance and law enforcement requests

But most users don't read the privacy policy. And even those who do often misunderstand what it means in practice. "Privacy" and "legal compliance" can be in tension. In South Korea's case, legal compliance won.

What this means, in practical terms:

Your AI conversations can be compelled by law enforcement: With a warrant or legal request, any platform hosting your conversations can be forced to produce them. Open AI has indicated it will comply with lawful requests.

There's no lawyer-client privilege for AI chats: When you talk to a lawyer, there's confidentiality. When you talk to Chat GPT, there isn't. The AI is not bound by attorney-client privilege, doctor-patient confidentiality, or any similar protection.

International requests create complexity: South Korea was able to obtain logs from a U.S. company, suggesting that mutual legal assistance treaties and international law enforcement cooperation will enable requests across borders. Your Chat GPT conversation in Taiwan could be subpoenaed for a case in Canada.

The expectation of privacy argument is weakening: Courts are increasingly finding that users of mainstream platforms don't have a reasonable expectation of privacy sufficient to shield data from warrants. This logic will likely extend to AI conversations.

The South Korea case crystallizes something that privacy advocates have been warning about: the erosion of digital privacy through the normalization of data sharing with law enforcement. Each case where evidence is admitted sets a precedent. Each precedent makes the next case easier for prosecutors. Each case normalizes the idea that your AI conversations are fair game.

This doesn't mean you shouldn't use Chat GPT or similar systems. It means you should understand that your conversations are not private in the way you might assume. If you're asking questions that could later be interpreted as planning or admitting to illegal activity, you should be aware that those questions could surface in a courtroom.

The Role of Open AI: Compliance, Responsibility, and Corporate Power

Open AI faced a fascinating dilemma in the South Korea case. They're a U.S. company bound by U.S. law, but they also operate globally and serve users in every country. When a South Korean court issued a legal request for user data, they had to decide: comply or resist?

There's no public statement from Open AI about their reasoning, but the outcome is clear: they complied. This makes sense from a business perspective. Open AI wants to operate in South Korea. They want access to South Korean users' money and data. Refusing a lawful legal request would jeopardize their market access and create legal liability.

But it also sets a precedent. Open AI has signaled to the world: "We will produce your user data when presented with lawful legal requests." This is actually good from a rule-of-law perspective. Companies should comply with lawful orders. But it also means that users in countries with authoritarian governments or invasive surveillance practices have even less privacy than they realize.

Imagine a scenario in China, Russia, or another country with active surveillance infrastructure. An AI platform could be compelled to produce all conversations related to political dissent, religious practice, or other sensitive topics. The corporate compliance that makes sense in South Korea (where the legal system has due process safeguards) becomes a tool for repression elsewhere.

Open AI, along with other AI companies, will face increasing pressure to navigate this tension. They can implement technological safeguards, like:

- End-to-end encryption for conversations (harder than it sounds, because it would prevent content moderation)

- Data minimization (storing only what's necessary, deleting the rest)

- Transparency reports (publishing how many requests they receive and how often they comply)

- User notification (letting users know if their data has been subpoenaed, when possible)

But they're unlikely to implement these voluntarily. The business model of AI assistants relies partly on being able to learn from user data and detect abuse. Strong encryption would undermine both.

What's more likely is that legislation will force the issue. As more jurisdictions recognize that AI conversation data is both valuable for law enforcement and sensitive for privacy, they'll regulate how it's stored, accessed, and disclosed.

Open AI's compliance in South Korea may prove to be the beginning of a much larger reckoning about corporate responsibility, user privacy, and the role of AI platforms in the legal system.

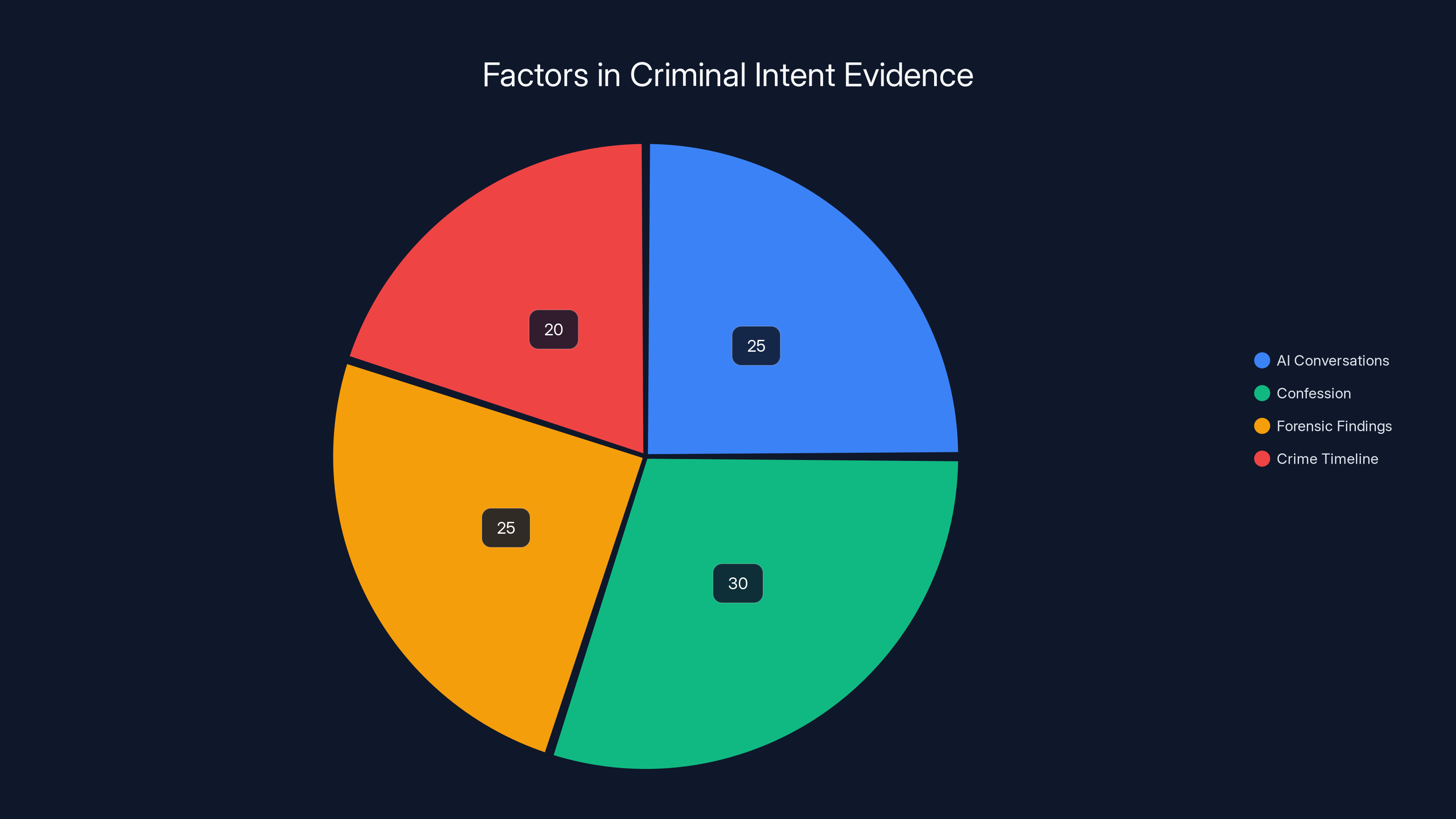

AI conversations are a growing part of criminal investigations, but they are typically one piece of a larger evidentiary puzzle. Estimated data.

Precedent and Ripple Effects: What Happens Next

The South Korea case won't remain isolated. It will inspire similar investigations worldwide.

In the United States, law enforcement agencies are already exploring how AI conversation logs might be used in criminal investigations. The FBI and local police departments receive training on digital forensics. They're learning that AI conversations, like search histories, can reveal intent, knowledge, and planning.

Prosecutors have clear incentives to pursue this path. AI conversation data is:

- Timestamped and difficult to fabricate

- Digitally signed with authentication metadata

- Centrally stored (no risk of a suspect destroying evidence)

- Often more detailed and explicit than other digital evidence

Compare this to a text message, which the suspect might delete, or a phone call, which leaves no record. An AI conversation is there, permanent and complete.

We should expect:

More warrant requests: Police departments will begin routinely requesting AI conversation data in investigations where motive, planning, or knowledge is disputed. What started as a rare case will become commonplace.

New legal battles over admissibility: As more cases use AI evidence, defense attorneys will challenge its reliability, relevance, and the way courts evaluate it. Some courts will rule differently than South Korea did. Some will find that Chat GPT logs are too speculative or prejudicial. Others will welcome them as reliable evidence.

Pressure on AI platforms: Companies will face competing demands. Law enforcement will push for easier access. Privacy advocates will push for stronger protections. Legislators will try to write rules. The companies themselves will try to minimize liability.

Legislative responses: Countries and states will likely craft new laws addressing AI conversations specifically. Some will create special protections (like treating certain AI conversations as privileged or confidential). Others will establish clearer frameworks for law enforcement access.

International differences: Some countries (like the EU, which has strong data protection laws) will probably build in stronger privacy safeguards. Others will give law enforcement freer access. This creates a patchwork where privacy protection depends on geography.

The South Korea case is a marker on a map. It shows where the technology has brought us, and it points toward where we're likely headed.

Evidentiary Standards: How Courts Will Evaluate AI Conversations

For AI conversation data to be reliably used as evidence, courts need standards. In the South Korea case, the court had to make some determinations on the fly. Other courts will face similar decisions.

Here's what a robust evidentiary framework for AI conversations might look like:

Authentication: The conversation logs must be verified as genuine. This requires establishing the chain of custody (how the data moved from Open AI's servers to the courtroom), confirming the account ownership, and verifying that the logs haven't been altered. Open AI's systems are sophisticated enough to do this, but courts need clear procedures.

Relevance: Just because a conversation exists doesn't mean it's relevant to a crime. A court must find that the conversation has a reasonable tendency to make a fact of consequence more or less probable. If someone asks Chat GPT "how to organize a surprise party," that's not relevant to a theft investigation. If they ask "how to disable security cameras," it might be.

Completeness and context: Courts should require that when AI conversations are introduced, they're presented in full context, not cherry-picked fragments. A single question taken out of context might seem incriminating when the full conversation reveals innocent intent.

Expert testimony on AI limitations: Courts should hear testimony about how AI works, how it might be misused, and how users might pose questions for innocent reasons. An expert should explain that asking Chat GPT hypothetical questions is not the same as planning to commit a crime.

Weighing prejudicial effect: There's a risk that jurors will give AI evidence more weight than it deserves. Simply showing that someone asked an AI system about illegal activity might be so inflammatory that it overshadows other evidence or leads to unfair conviction. Courts should carefully consider whether the probative value outweighs the risk of unfair prejudice.

Standards for different types of queries: Queries asking "how would someone theoretically do X" are different from queries asking "how can I specifically do X." Courts will need to develop standards for evaluating different types of questions and what they suggest about intent.

The South Korea case didn't establish all these standards. It simply found that AI conversation data could be admitted. Future cases will refine and develop clearer rules.

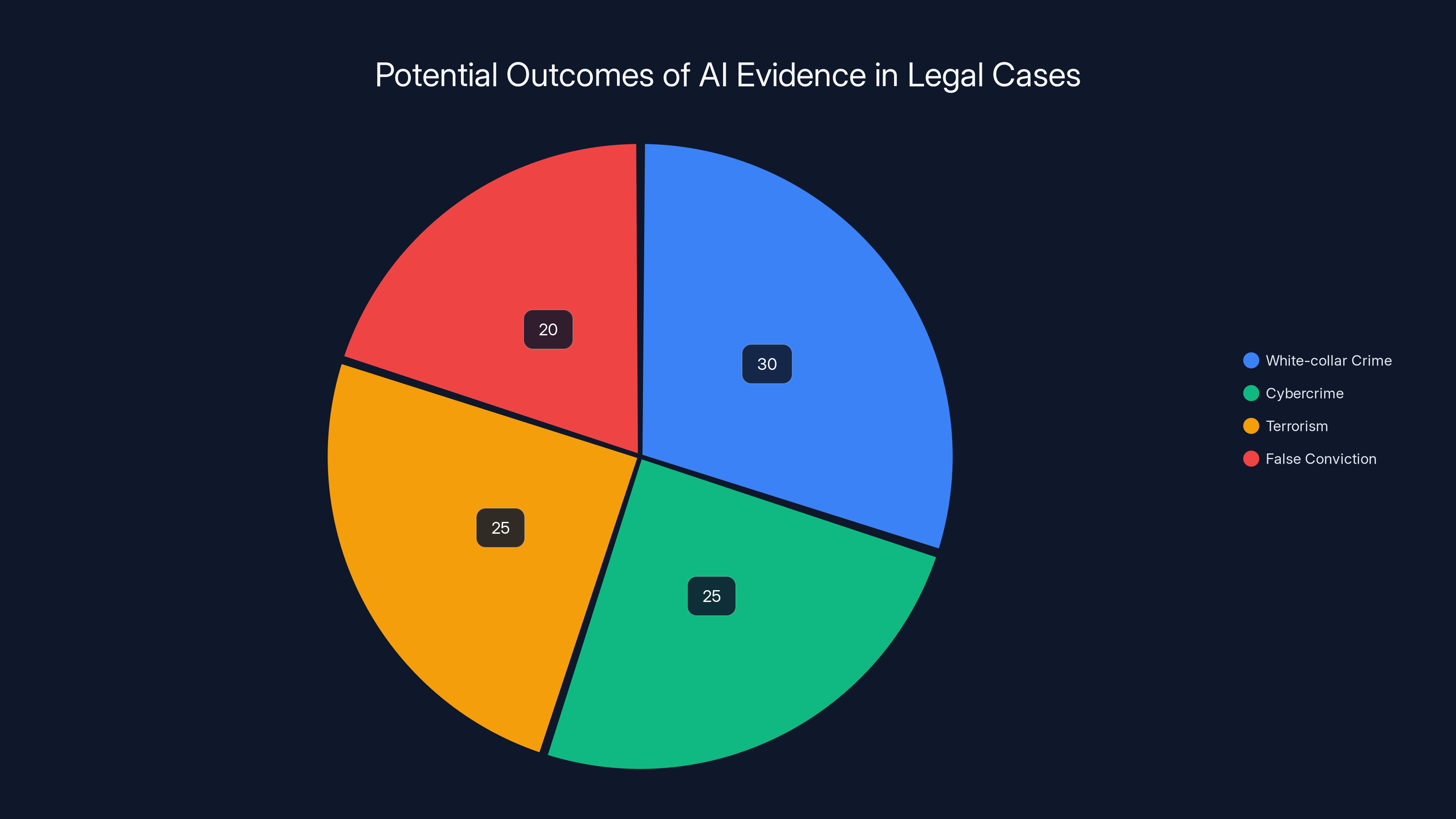

Estimated data suggests that AI evidence is most likely to be used in white-collar crime cases, followed by cybercrime and terrorism. False convictions, while less likely, highlight the need for safeguards.

The Global Legal Landscape: How Different Jurisdictions Respond

Not every country will follow South Korea's approach. Different legal systems, privacy frameworks, and cultural attitudes toward surveillance will lead to different outcomes.

The European Union: The EU has the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), one of the world's strictest privacy laws. Even if law enforcement requests AI conversation data, GDPR imposes limits on how it can be processed. The EU may also develop specific protections for conversations with AI systems, treating them as particularly sensitive. The likelihood is that EU courts will be more cautious about admitting AI evidence and more protective of user privacy than South Korean courts were.

The United States: The U.S. legal system is mixed. Federal courts might take one approach, while state courts take another. The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches, but it's not clear whether the expectation of privacy extends to AI conversations. Some states might pass legislation protecting AI conversations; others might allow unfettered law enforcement access. The U.S. is likely to see fragmented, inconsistent approaches across jurisdictions.

China and Russia: Countries with less robust rule-of-law protections might treat AI conversation data as a tool for surveillance and political control. If the government wants to know what you've been asking Chat GPT, they might simply demand access without the legal niceties that applied in South Korea. This could suppress free speech and research.

India and other emerging markets: Countries developing their legal frameworks are watching the South Korea case closely. They'll likely adopt approaches similar to either the EU or the U.S., depending on their legal tradition and their appetite for surveillance.

AI platforms' response: Open AI and other companies might develop different privacy policies or data retention practices for different jurisdictions. They might encrypt data more strongly in countries with strict privacy laws, or comply more readily in countries with strong law enforcement cooperation.

The result is a fragmented global legal landscape where your privacy protection depends on where your data is stored, which platform you use, and which country's law enforcement might request your data.

Criminal Intent: How AI Conversations Reveal State of Mind

One of the most interesting aspects of the South Korea case is that it treats Chat GPT conversations as evidence of the suspect's state of mind and intent. This is both powerful and problematic.

Powerful because intent is notoriously hard to prove. If you confess that you planned to kill someone, that's direct evidence of intent. But most criminals don't confess upfront. They leave a trail: researching methods, asking questions, discussing plans with others. By incorporating AI conversations, investigators can reconstruct a mental timeline of planning and knowledge.

Problematic because intent is also easy to infer incorrectly. People ask AI systems hypothetical questions out of curiosity, academic interest, or creative writing inspiration. Someone researching "how to poison someone" might be writing a murder mystery novel. Someone asking about "untraceable methods" might be interested in forensic science. The fact that a question was asked doesn't necessarily prove the asker intended to act on the answer.

Prosecutors in the South Korea case appear to have recognized this. They didn't rest their case on the Chat GPT evidence alone. They combined it with other evidence: the confession, the forensic findings, the timeline of the crime. The AI conversation was one piece of a larger evidentiary puzzle.

But as this becomes more common, there's a risk that courts will start reading too much into AI conversations. A judge or jury might see that a defendant asked Chat GPT about a particular method and assume that proved planning, when actually the person was just curious.

This is where expert testimony becomes crucial. Defense attorneys should hire experts in AI systems to explain how people use them, why they ask certain questions, and what assumptions shouldn't be made. Courts should demand this testimony before admitting AI evidence.

There's also a philosophical question lurking here: to what extent can a conversation with an AI reveal state of mind? The AI isn't a confidant or a co-conspirator. It's a language model that responds to queries. Talking to Chat GPT is different from talking to a friend, writing in a diary, or confessing to a priest. The mental state it reveals is more shallow, more subject to misinterpretation.

Future legal standards will need to grapple with this distinction. Until they do, there's risk of injustice: people convicted based on AI conversations that, in context, don't actually prove what prosecutors claim.

The investigation progressed significantly from December 2024 to March 2025, with key breakthroughs such as the digital evidence from ChatGPT contributing to the case. Estimated data.

Digital Forensics and Chain of Custody: Technical Challenges

When evidence is presented in court, it must be authentic and unaltered. For digital evidence, this requires establishing a "chain of custody," a documented trail showing who had access to the data, when, and under what circumstances.

For traditional physical evidence, this is straightforward. A knife is collected at a crime scene, labeled, placed in a sealed bag, and passed from one person to another. Each handoff is documented. If the knife is presented in court, the chain of custody proves it's the same knife from the scene.

For digital evidence, particularly AI conversations, the process is more complex.

When South Korean prosecutors obtained Chat GPT logs from Open AI, they had to establish:

Server integrity: The logs came from Open AI's servers. Are those servers secure? Could someone have altered the logs without detection? Open AI's infrastructure includes security measures and audit logs, so they can theoretically prove that no one tampered with the data.

Account verification: Did the logs actually come from the suspect's account? Open AI can verify account ownership and confirm that the IP addresses and device identifiers match the suspect's devices.

Completeness: Are the logs complete, or could some conversations have been deleted? Open AI's systems would show deletion history if available. The platform's design also means that conversations are stored permanently on servers, so the risk of loss is lower than with locally stored data.

Timestamp accuracy: The logs include timestamps. How accurate are they? Open AI's servers synchronize with standard time servers, so timestamps should be reliable.

Third-party integrity: When data moves from Open AI to prosecutors, how is it protected? Courts need to verify that no one altered or added data in transit. This typically involves cryptographic hashing, a mathematical technique that would reveal any alteration.

Each of these steps introduces potential vulnerabilities or areas where an expert witness might challenge the data's reliability. As more cases rely on AI conversation evidence, courts and companies will develop clearer standards for handling and verifying this data.

There's also a practical issue: scale. If law enforcement starts requesting AI conversation data in hundreds or thousands of cases, Open AI's systems will be strained. They'll need to develop streamlined processes for legal requests, and those processes will need to balance efficiency with accuracy.

The Dark Side: Misuse Risks and Unintended Consequences

While the South Korea case involved a prosecution of an apparently guilty person, the admission of AI conversation evidence creates risks for misuse.

False confessions and manufactured intent: If someone is interrogated about whether they asked Chat GPT something, they might confess falsely (a documented risk in criminal interrogations) or admit to asking questions they didn't actually ask. Later, when the logs are retrieved, the discrepancy could be blamed on faulty memory rather than false confession. Or, conversely, actual AI conversations could be presented out of context to make innocent questions seem incriminating.

Overreach by law enforcement: Once law enforcement realizes AI conversations can be evidence, they might request data in cases where it's not actually relevant. A fishing expedition for anything suspicious. Courts would need to apply strict relevance standards to prevent this.

Chilling effect on research and free speech: If people know that asking Chat GPT about sensitive topics could make them a person of interest in an investigation, they might self-censor. Someone researching a controversial topic, writing fiction, or exploring ideas might avoid using AI systems out of fear. This could chill free speech and intellectual exploration.

Discrimination and bias in investigation: If law enforcement uses AI conversation searches to build target lists, they might disproportionately target certain groups. For example, if they flag all users who ask about "how to make explosives," they might catch legitimate researchers, engineers, and educators along with actual threats. Without careful safeguards, this could entrench bias in criminal investigation.

Corporate surveillance masquerading as law enforcement: What starts as law enforcement requests might expand into corporations requesting data from AI platforms. A competitor could theoretically request to know what your company asked Chat GPT about. Or an employer could request data about employees. The legal framework needs to prevent this mission creep.

International authoritarian use: In countries without robust rule-of-law protections, AI conversation data could be used for political repression. Dissidents' conversations, religious minorities' research, political opponents' planning—all could be weaponized. The South Korea case sets a precedent that any country can follow.

These risks are not hypothetical. They're foreseeable consequences of the legal framework that's being established. Policymakers and courts need to address them proactively.

Regulation and Policy Responses: What Should Happen

The South Korea case is a wake-up call for policymakers. Without clear rules about how AI conversation data is handled, stored, and accessed, we're going to see an ad-hoc mix of legal standards, corporate policies, and law enforcement practices.

What should regulation look like?

Data minimization: AI platforms should store only the data necessary to provide the service and detect abuse. Once data is no longer needed for those purposes, it should be deleted. This would reduce the amount of conversation history available for law enforcement requests.

Encryption: End-to-end encryption of user conversations would prevent both Open AI and law enforcement from easily accessing the content. The trade-off is that Open AI wouldn't be able to use the conversations to improve models or detect abuse. But the privacy protection might be worth it.

Legal process requirements: Before law enforcement can access AI conversation data, they should be required to obtain a warrant or subpoena, not just a legal request. The standard should be high: probable cause or equivalent. In the South Korea case, prosecutors apparently followed some legal process, but it's not clear how high the bar was.

User notification: When possible, users should be notified that their AI conversation data has been requested or obtained. This transparency helps users understand the risks and challenges false or misleading law enforcement claims.

Transparency reporting: AI platforms should publish regular reports on how many data requests they receive and how often they comply. This creates public accountability.

Exemptions for certain conversations: Some conversations might deserve special protection. For example, conversations between someone and an AI while they're seeking mental health advice, or religious guidance, or legal information. These might be given status similar to confidential conversations with professionals.

International standards: Given that AI platforms operate globally, international agreements on how AI conversation data is handled could prevent a race to the bottom where authoritarian countries demand access without due process.

Judicial training: Judges need to understand AI technology, how it works, and its limitations. They need training on evaluating AI evidence, understanding chain of custody for digital data, and recognizing when AI conversations are being misused as evidence.

None of this is currently in place. Regulation is trailing far behind technology. The South Korea case highlights the urgency of closing that gap.

The Broader AI Safety Question: How This Fits Into Larger Concerns

The South Korea case sits at the intersection of criminal justice, privacy, and AI safety. It's worth stepping back and considering how this plays into larger AI safety and governance concerns.

AI systems like Chat GPT are designed to be helpful, but they're not designed with criminal investigation in mind. Open AI's safety practices focus on:

- Reducing harmful outputs

- Detecting abuse

- Improving model reliability

- Protecting user privacy

But now, those systems are being used in criminal investigations in ways the designers probably didn't fully anticipate. This is a common pattern with technology: it's built for one purpose, then repurposed for something else.

The South Korea case raises important questions:

Should AI platforms be designed differently if their data will be used in criminal cases? Should they maintain more complete logs? Better metadata? Or should they minimize logs specifically to protect user privacy?

What are the incentives for Open AI? Right now, they have competing incentives: comply with law enforcement (good for business and public safety) versus protect user privacy (good for user trust and data minimization). They haven't clearly signaled which is prioritized.

How does this affect the AI safety field broadly? If AI companies know their user data can be subpoenaed, will they collect more data or less? Will they be more cautious about user conversations, or more aggressive? These decisions have safety implications.

What role should AI platforms play in law enforcement? Should they proactively help law enforcement detect crimes? Or should they be neutral infrastructure providers? The answer affects their design and operations.

These are governance questions that extend beyond the South Korea case. They're about how AI integrates into society, how power is distributed between technology companies and governments, and how we balance innovation with safety and privacy.

Real-World Applications: How This Will Play Out

To make this concrete, let's imagine a few scenarios that are likely to unfold in the coming years.

Scenario 1: A white-collar crime investigation: A person is suspected of fraud. Law enforcement obtains a warrant for their Chat GPT conversations and finds questions about "how to hide money transfers" and "how to create shell companies." Combined with financial records showing suspicious activity, this becomes powerful evidence of intent. The person is convicted in part based on the AI evidence.

Scenario 2: A cybercrime case: A hacker is suspected of infiltrating a company's systems. Prosecutors request their Chat GPT logs and find conversations about "SQL injection techniques" and "finding zero-day vulnerabilities." Again, the AI conversations are used to prove knowledge and intent.

Scenario 3: A terrorism investigation: A person suspected of planning terrorism asked Chat GPT about explosive devices. The AI conversations become evidence in a terrorism prosecution. This is the scenario that will probably generate the most public support for using AI evidence.

Scenario 4: An innocent person falsely convicted: A person asks Chat GPT hypothetical questions about a crime, out of curiosity. Law enforcement interprets the questions as evidence of guilt. The AI conversations are used to prosecute, and the person is convicted based partly on misunderstood AI evidence. Years later, the mistake is discovered, but the damage is done.

All four scenarios are plausible. Scenarios 1-3 probably happen first and generate support for using AI evidence. Scenario 4 might not happen until after the legal precedent is established.

The question for society is: what safeguards do we want in place before scenario 4 happens?

Looking Ahead: What the Future Might Hold

In the next few years, we should expect:

More cases using AI evidence: As the South Korea case becomes known, law enforcement agencies worldwide will start requesting AI conversation data. It will become routine in criminal investigations.

Refined legal standards: Courts will develop more sophisticated rules for admitting AI evidence, similar to how they developed rules for DNA evidence and digital forensics over the past few decades.

Competing regulatory approaches: Different countries and regions will regulate AI conversation data differently. The EU will be protective; authoritarian countries will be permissive; the U.S. will be mixed.

New AI products and services: Companies might develop "privacy-first" AI assistants that delete conversations immediately, use end-to-end encryption, or don't log conversations at all. These will compete with more logging-intensive platforms.

Legislative action: Governments will pass laws addressing AI conversations specifically. Some will protect privacy; others will facilitate law enforcement access.

Societal reckoning: As more people realize their AI conversations can be used against them, there will be public debate about the trade-offs between privacy, safety, and innovation.

The South Korea case is the beginning of this story, not the end. It marks the moment when society realized that AI conversations have legal significance. Everything that follows is us figuring out what that means.

FAQ

What is the South Korea murder case about?

A 38-year-old man in Busan confessed to murdering two acquaintances and dismembering their bodies. Investigators discovered that he had used Chat GPT to search for information related to the crimes, and prosecutors obtained his chat logs through a legal warrant request to Open AI. The case is significant because it's the first major criminal prosecution where AI conversation logs served as central forensic evidence.

How did prosecutors obtain the Chat GPT logs?

Prosecutors obtained a legal warrant to request the logs from Open AI. The exact mechanism was likely a mutual legal assistance treaty (MLAT) request from South Korea to the United States, a formal process for one country to request evidence from another. Open AI, as a U.S.-based company, complied with the lawful request and provided the relevant conversation history.

Can Chat GPT conversations be used as evidence in court?

Yes, according to the South Korea case and likely future courts worldwide. Provided that the conversations are authenticated, relevant, and obtained through proper legal process (with a warrant), AI conversation logs can be admitted as evidence. However, standards are still developing, and different jurisdictions may apply different rules.

What privacy protections do Chat GPT users have?

Chat GPT users have limited privacy protections. Conversations are not encrypted end-to-end, Open AI can access and review them for safety and improvement purposes, and they can be obtained through legal warrants. Users don't have attorney-client privilege, doctor-patient confidentiality, or other special protections for their AI conversations. However, some jurisdictions (particularly the EU under GDPR) have stronger privacy laws that may provide additional protection.

What should I know about asking AI systems sensitive questions?

You should understand that questions asked to Chat GPT, Claude, or similar systems are not private. They're stored on company servers and can potentially be accessed by law enforcement with a warrant. If you're asking questions about illegal activities, you should assume those questions could surface in a legal proceeding. Consider using alternative methods for sensitive research, such as books, encrypted messaging, or offline resources.

Will AI conversation data be used in future criminal investigations?

Yes, almost certainly. The South Korea case establishes a precedent that law enforcement agencies worldwide will follow. We should expect AI conversation logs to become routine evidence in criminal investigations, similar to search engine queries and email. Standards for how they're used will develop over time through legislation and court cases.

What regulations might be coming for AI conversation data?

Governments are likely to pass laws addressing how AI conversation data is stored, accessed, and used in criminal investigations. These might include requirements for warrants before law enforcement can access data, user notification if data is requested, platform transparency reporting, and potentially special protections for sensitive conversations. The EU is likely to be more protective of privacy, while other regions may facilitate law enforcement access.

Could this lead to unfair convictions?

Yes, there's a risk. AI conversation evidence could be misinterpreted if taken out of context. Someone asking hypothetical questions might be misunderstood as planning a crime. Innocent research could be misconstrued as guilty intent. As this type of evidence becomes more common, strong legal standards and expert testimony will be critical to prevent wrongful convictions based on misunderstood AI conversations.

Key Takeaways

The South Korea double murder case represents a watershed moment for how artificial intelligence intersects with criminal justice. It's the first major prosecution where AI conversation logs served as central evidence, establishing a precedent that law enforcement worldwide will follow. Users of Chat GPT and similar systems should understand that their conversations are not truly private and can be obtained through legal warrants. Courts are still developing standards for how AI evidence should be evaluated, authenticated, and admitted. Future legislation will likely address privacy protections, law enforcement access, and platform responsibilities. The case raises important questions about the balance between public safety and individual privacy, between law enforcement tools and civil liberties, and between corporate responsibility and technological innovation. As AI becomes more integrated into daily life, how we govern its role in criminal justice will shape both the technology and our rights.

Related Articles

- Ring's Search Party Surveillance Feature Sparks Mass Backlash [2025]

- Microsoft Handed FBI Encryption Keys: What This Means for Your Data [2025]

- TikTok's Immigration Status Data Collection Explained [2025]

- Why "Catch a Cheater" Spyware Apps Aren't Legal (Even If You Think They Are) [2025]

- Digital Rights 2025: Spyware, AI Wars & EU Regulations [2025]

![ChatGPT as Evidence: Inside South Korea's Landmark Murder Case [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/chatgpt-as-evidence-inside-south-korea-s-landmark-murder-cas/image-1-1771630683769.jpg)