Introduction: When Did Phones Become So Predictable?

Remember when getting a new phone felt like Christmas morning? You'd tear open the box, marvel at the industrial design, and show everyone your new device like it was a piece of art. Now? Phones feel like slightly faster versions of last year's model dressed in marginally different colors.

This isn't paranoia. Look at the numbers. The smartphone market has matured so dramatically that year-over-year improvements in visible innovation have flatlined. A person could honestly use an iPhone 14 or Samsung Galaxy S23 from 2022 and still have a perfectly capable device in 2025. That's not necessarily bad, but it does mean the industry has stopped surprising us.

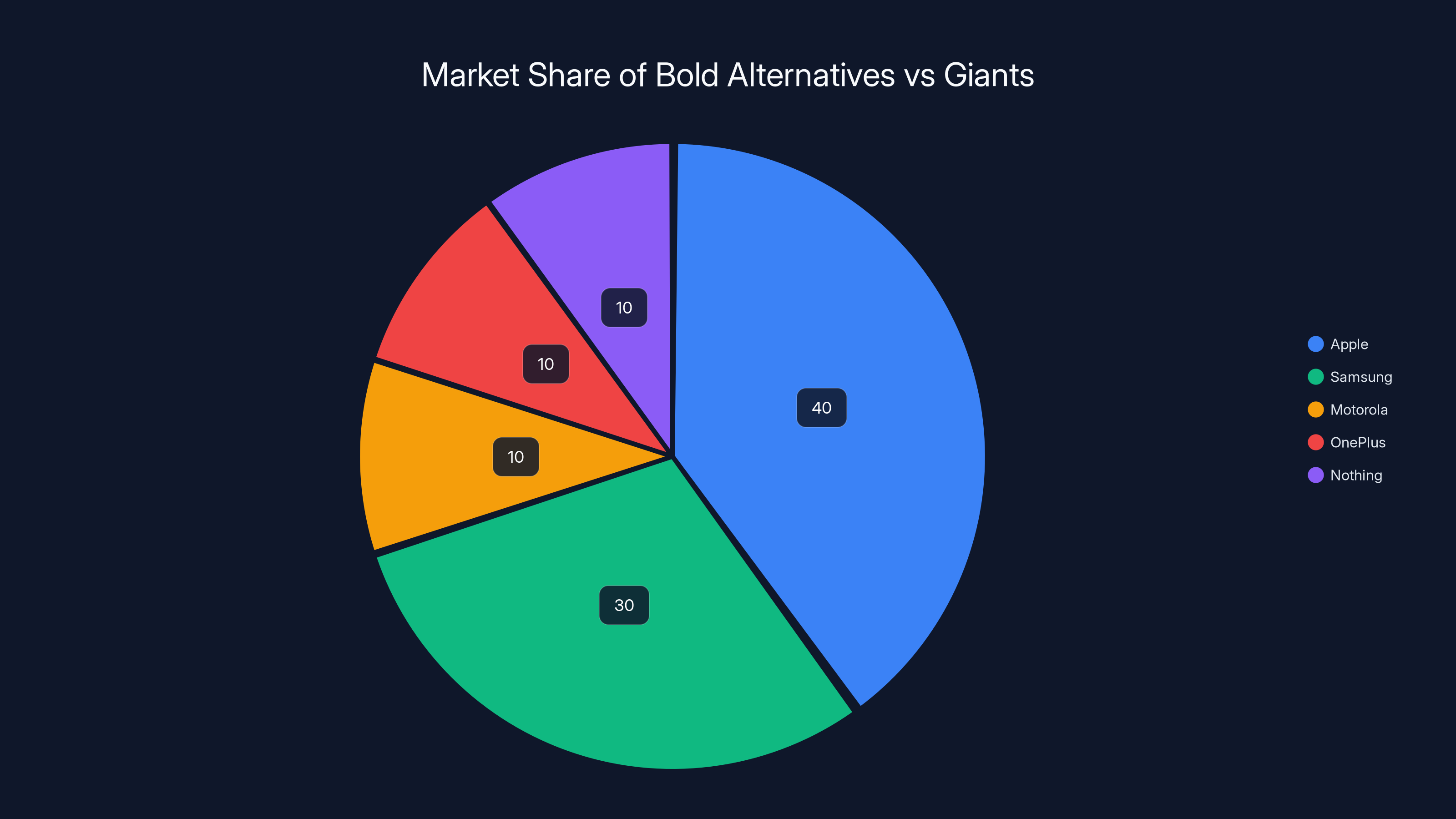

The real problem is that Apple and Samsung, which control roughly 50% of the global smartphone market, have settled into a rhythm of incremental updates. Camera bump gets bigger. Processor is 5% faster. Screen is marginally brighter. Rinse, repeat, profit. It works financially, sure. But it's boring as hell.

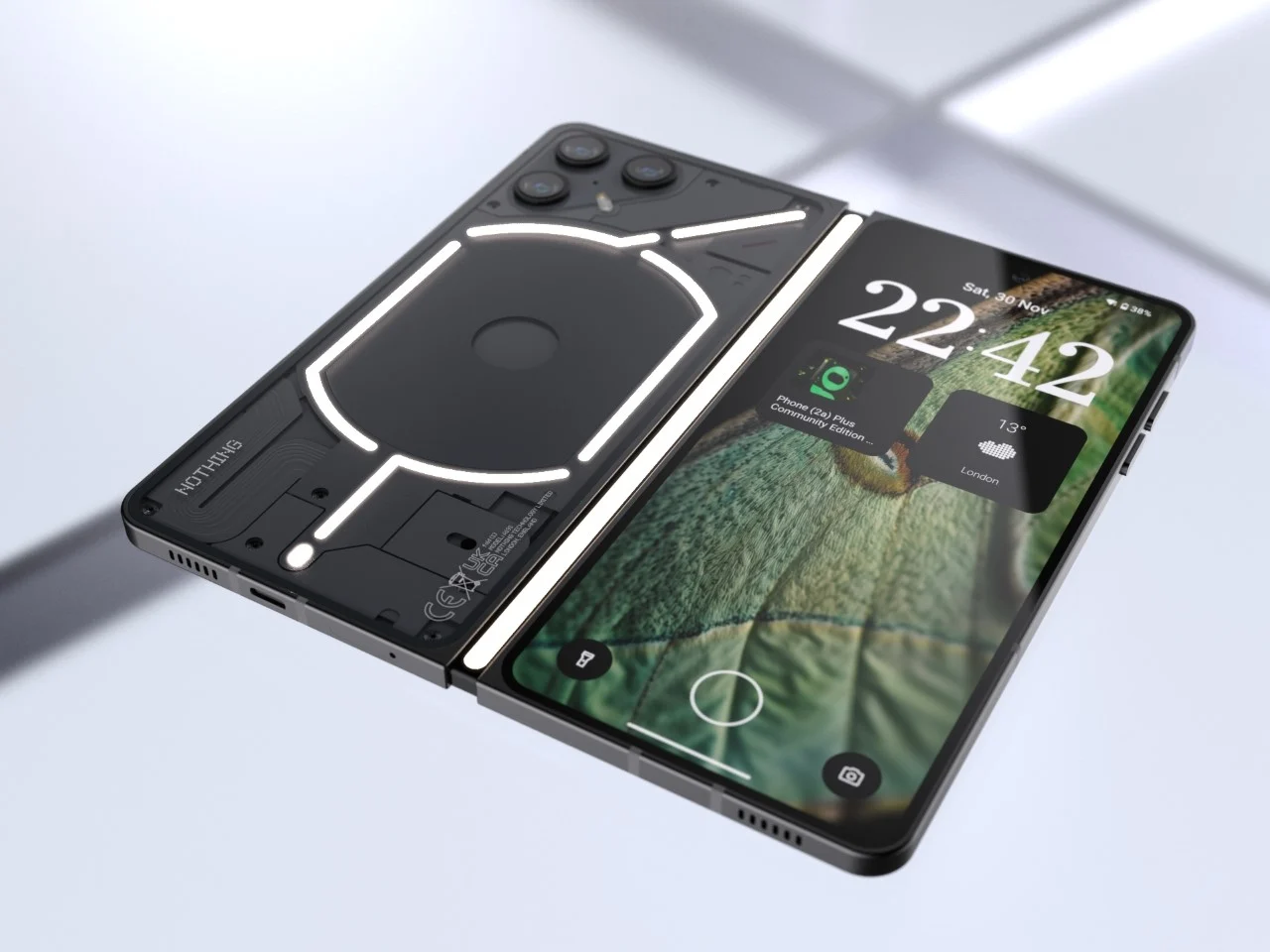

Meanwhile, brands like Nothing are proving something radical: people actually care about design. Their transparent back panels, glyph interface, and bold aesthetic choices have generated more buzz than a dozen Samsung Galaxy refreshes combined. They're reminding us that phones don't have to look like black rectangles.

This article explores why the smartphone industry got stuck in a creativity rut, how Nothing and other challengers are breaking that pattern, and what actually needs to happen for phones to feel exciting again. We're talking real design philosophy, not just marketing speak. The stakes matter because the phone in your pocket is the most personal technology you own. It deserves to be more than functional. It deserves to be interesting.

TL; DR

- Smartphone innovation has plateaued because the "good enough" threshold is too high—anything more means significant cost increases

- Design has become risk-averse at major manufacturers due to quarterly earnings pressure and conservative market research

- Nothing, Motorola, and OnePlus are proving alternative designs can succeed by betting on uniqueness over market-tested safety

- Folding phones remain niche because the technology isn't mature enough to be reliable at mainstream prices

- The future of phone design depends on manufacturers prioritizing aesthetics and durability over razor-thin margins and annual upgrade cycles

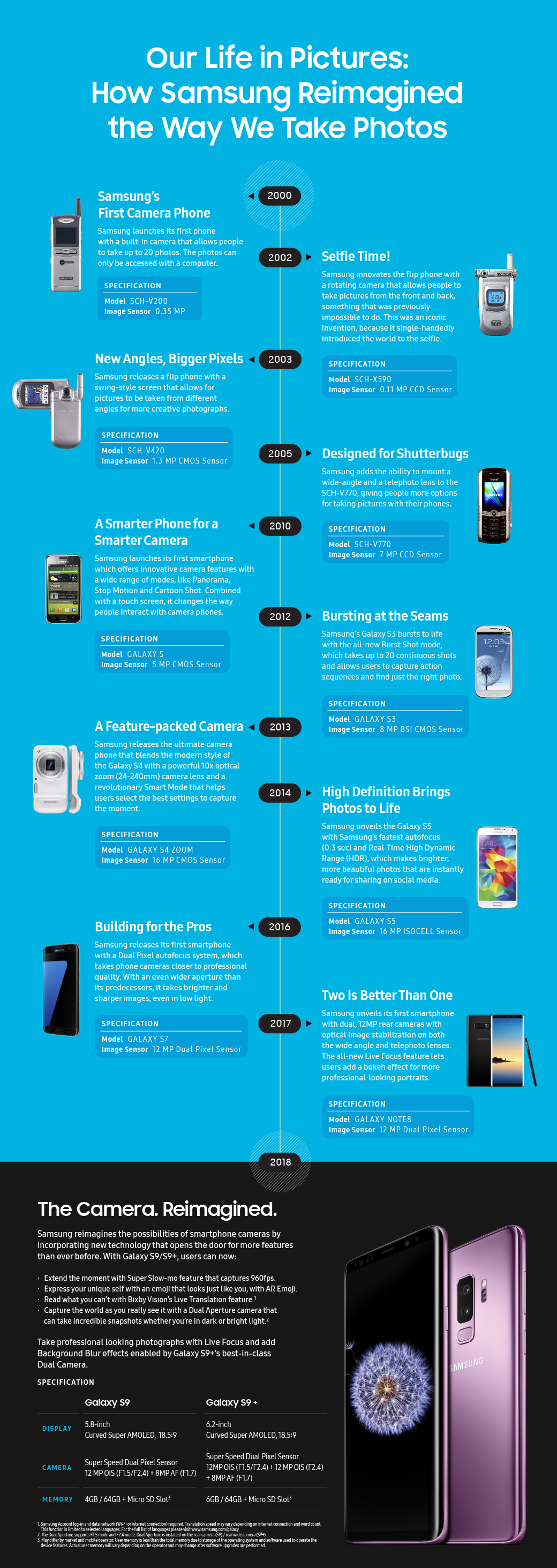

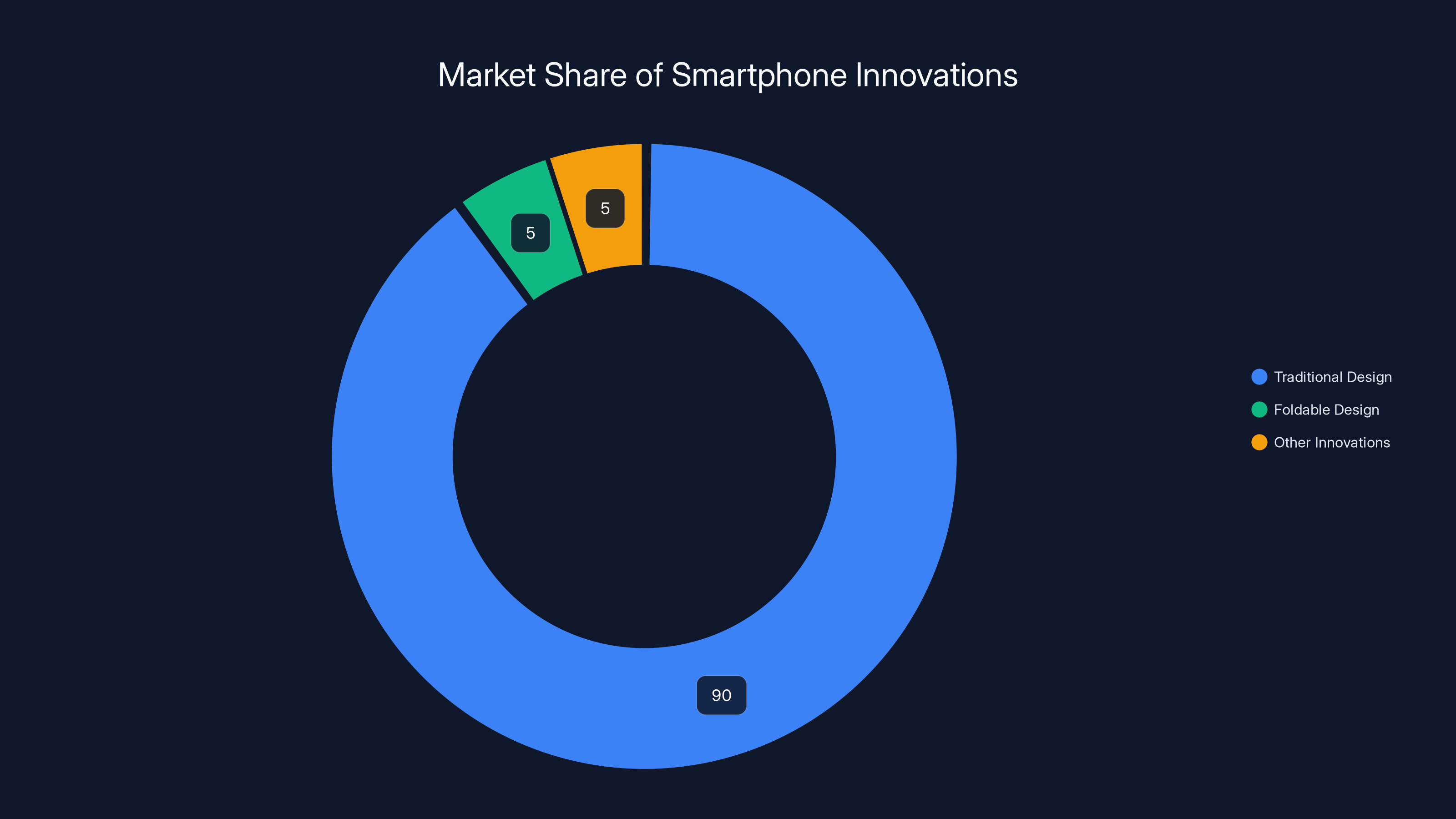

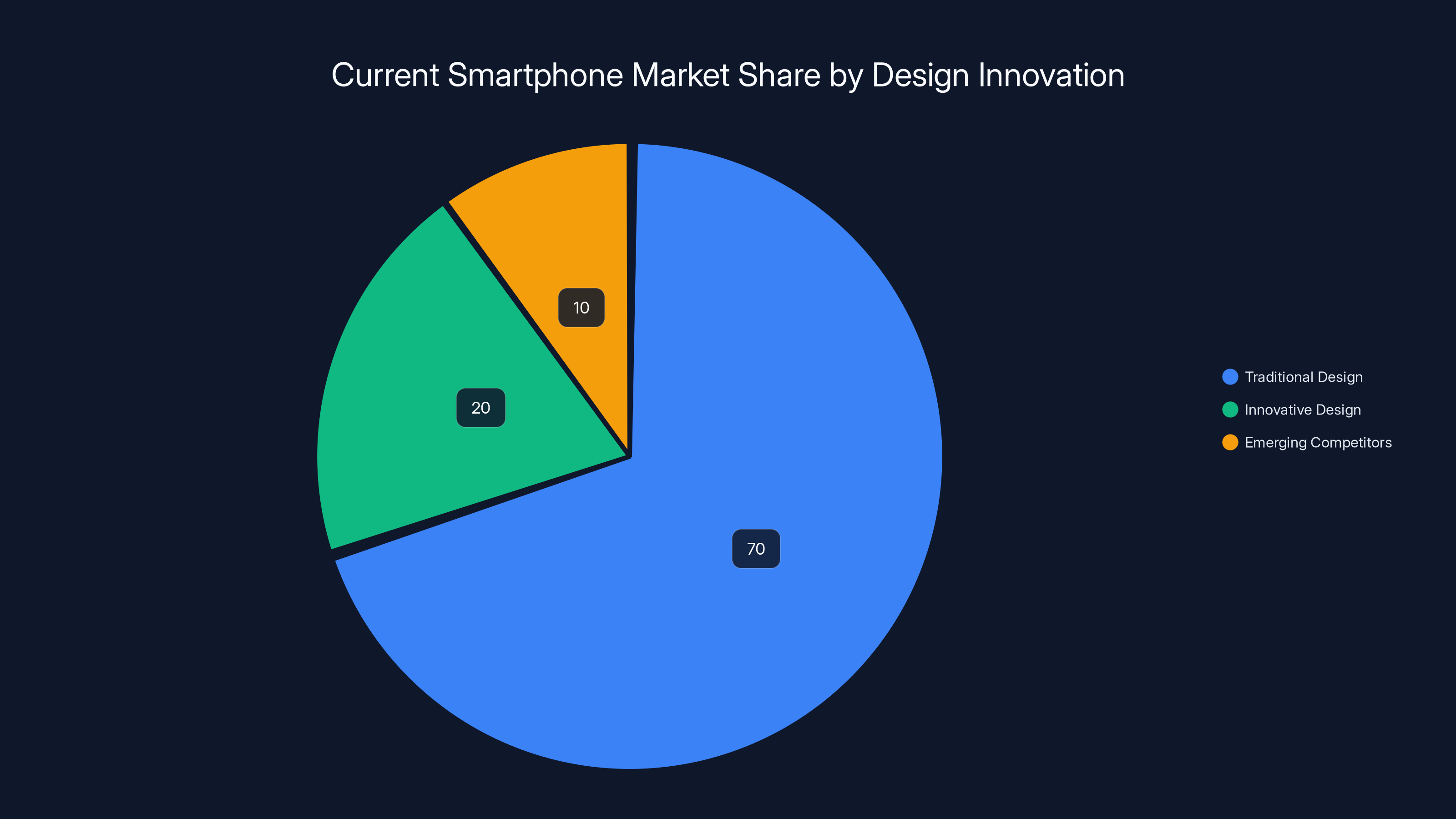

Estimated data shows that traditional smartphone designs dominate the market, with foldable and other innovative designs making up a small fraction.

Why Apple and Samsung Play It Safe

When you control the market, you have everything to lose and nothing to gain. That's the commercial reality facing Apple and Samsung. They've optimized themselves into a corner.

Apple's iPhone 15 launched in 2023 looking nearly identical to the iPhone 14, 13, and 12. The differences were real—better chip, brighter screen—but fundamentally invisible to the human eye without direct comparison. Samsung's Galaxy S24 pulled the same move. Slightly better processing. Slightly better cameras. Slightly better everything. The annual update becomes a puzzle where the differences are so marginal that most people can't justify the $1,200 price tag.

Why does this happen? The answer lies in risk mathematics.

The Cost of Innovation

Every radical design change carries enormous financial and reputational risk. When Samsung launched the Galaxy Z Fold, they invested hundreds of millions in engineering a foldable display. The first model cost $2,000 and had durability issues. The market response? Cautious interest from early adopters, but mainstream consumers stayed away. Fast forward several generations and foldables still represent less than 5% of Samsung's phone sales.

Compare that to an iterative design update. Apple released the iPhone 14 Pro with a dynamic island instead of a notch. Cost to implement? Probably manageable. Risk? Low, because people already understand the concept. The market response proved that people will upgrade for even tiny visual changes, especially if paired with a faster processor and "AI features."

This is the trap. Once you discover that people will upgrade for marginal improvements, why risk billions on radical design experiments? The math doesn't work. Shareholders expect predictable quarterly earnings. Radical design changes introduce unpredictability.

The "Slab" Prison

Let's be honest: modern flagship smartphones have converged on a single form factor. Glass back, aluminum frame, rounded corners, centered camera module, flat or slightly curved edges. This isn't because it's the only possible design—it's because it's the safest design.

The form factor itself poses genuine engineering constraints. Phones need to fit in pockets, be easy to hold, accommodate battery density, and dissipate heat efficiently. Modern processors and camera systems generate tremendous thermal stress. Push the design too far from the standard slab and you hit problems.

But here's what's frustrating: these aren't actually limiting constraints for skilled engineers. They're limiting because the industry decided years ago that maintaining thinness—something customers never asked for—was worth prioritizing. The iPhone 6 was already thin enough. The iPhone 12 was thinner. The iPhone 15 is essentially the same thickness. Apple could make an iPhone that's 2mm thicker, double the battery life, improve thermal management, and design something visually distinctive. But they won't, because tradition.

Market Research as a Creativity Killer

Modern corporations rely on focus groups and A/B testing to validate every decision. This approach works great for optimization but terrible for innovation. Focus group participants, when shown a radical new phone design, often recoil. "That's different. Will it still fit my case?" "What about resale value?" "That color seems... risky."

Apple famously ignored focus groups when designing the original iPhone, but that was two decades ago. Today's Apple runs focus groups. They test. They optimize. And optimization pushes toward the mean, toward safety, toward the familiar.

Nothing started with zero market share to protect. Their design philosophy wasn't validated by surveys—it was validated by engineering excellence and creative vision. That's a luxury that companies with 50% market share can't afford.

Estimated data shows that while Apple and Samsung dominate with a combined 70% market share, Motorola, OnePlus, and Nothing collectively hold a significant 30%, highlighting their growing influence as bold alternatives.

The Nothing Difference: How Transparency Became a Philosophy

Nothing's smartphone line proves a simple truth: if you give people something they've never seen before, they pay attention.

When Nothing launched the Phone 1 in 2023, the smartphone world had become so uniform that a transparent back panel felt genuinely radical. The phone exposed the internal components—circuit boards, chips, haptic engines—in a design language that looked more like scientific equipment than consumer device. It was the opposite of what focus groups would recommend.

The market response shocked the industry. The Nothing Phone 1 wasn't the fastest phone. It wasn't the cheapest. But it felt different. It felt like someone actually thought about design philosophy instead of just iterating on last year's blueprint.

Beyond Transparency: The Glyph Interface

But Nothing didn't stop at transparent aesthetics. They introduced the Glyph interface, a grid of LED lights on the back of the phone that serves multiple functions. Notifications light up specific areas. Different light patterns indicate different alerts. It's both functional and genuinely novel—something you can't do with a traditional back panel.

Why hasn't Apple or Samsung implemented something similar? Because it's different. Because focus group participants would ask whether it drains battery (it does, slightly). Because some people might find it gimmicky. Because integrating something that novel requires rethinking the entire phone architecture.

Nothing approached the problem differently. They asked: "What could we do on the back of a phone that nobody's doing?" instead of "What do people expect from the back of a phone?" The first question leads to innovation. The second leads to incremental updates.

The Economics of Design Risk

Nothing operates on a different economic model than Apple or Samsung. They have much lower margins, much lower volume expectations, and a core audience that specifically seeks out alternative products. This model allows them to take risks that market leaders can't.

But here's the critical insight: Nothing is profitable despite lower margins because they've captured a specific market segment that values design and differentiation over brand prestige and ecosystem lock-in. They've proven there's a real audience for distinctive smartphones.

The lesson for Apple and Samsung is that they're leaving money on the table. Not all their customers want to upgrade to a slightly faster processor. Some would happily pay for genuine design innovation. But the incumbents have structured their businesses around annual refresh cycles and predictable earnings, making it hard to pivot toward radical experimentation.

The Folding Phone Problem: Why Foldables Haven't Solved the Boredom

Samsung spent billions developing folding technology. The Galaxy Z Fold represents genuine innovation—a phone that actually transforms into a tablet. By all accounts, this should be the future. Instead, foldables remain a niche luxury product bought mainly by tech enthusiasts and corporate executives with unlimited budgets.

Why? Because foldables solved an engineering problem that consumers never asked for.

The Technology Maturity Gap

Folding phones require breakthrough materials, novel hinge mechanisms, and completely redesigned software interfaces. Samsung's latest Z Fold is genuinely impressive engineering. But the crease on the display is still visible. The outer screen is narrower than any practical phone. Battery life suffers because the form factor makes thermal management harder. The durability still feels fragile compared to a traditional glass phone.

Meanwhile, the benefit is... what, exactly? You can use a wider screen when unfolded? But Android apps weren't designed for that aspect ratio, so most apps just add weird spacing or force a tablet view that looks wrong. The multitasking potential is interesting, but most users don't need to run three apps simultaneously on a phone.

The Price Reality Check

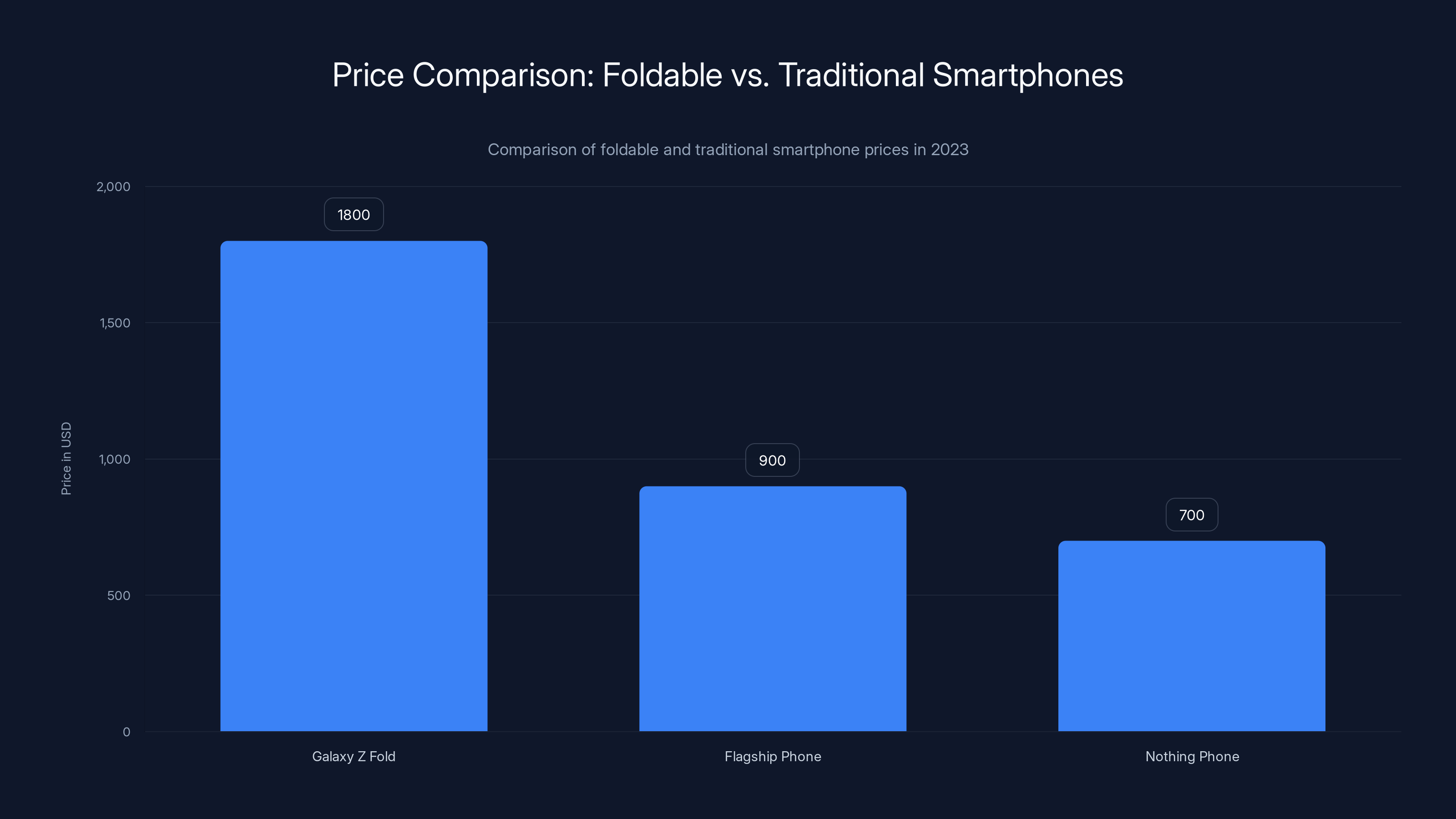

Galaxy Z Fold devices start around $1,800. That's nearly twice the cost of a comparable flagship phone with more processing power, better durability, and longer battery life. The value proposition is murky. You're paying premium prices for technology that's still first-generation in many respects.

Compare that to Nothing's approach. They proved you could build a distinctive phone at a mainstream price point (

What Foldables Got Wrong

Folding phones approached innovation through engineering rather than user experience. Samsung said, "We can build a folding display," and worked backward to figure out why people would want it. They should have started with the user need—"What would actually improve the daily experience of smartphone usage?"—and then engineered a solution.

The honest answer is that most people don't need a folding phone. They need better battery life, more distinctive design, better durability, and faster charge times. None of those require folding technology.

Samsung's folding strategy has distracted them from solving problems that actually matter to the mainstream market. Meanwhile, competitors are winning by addressing those basic needs with distinctive design.

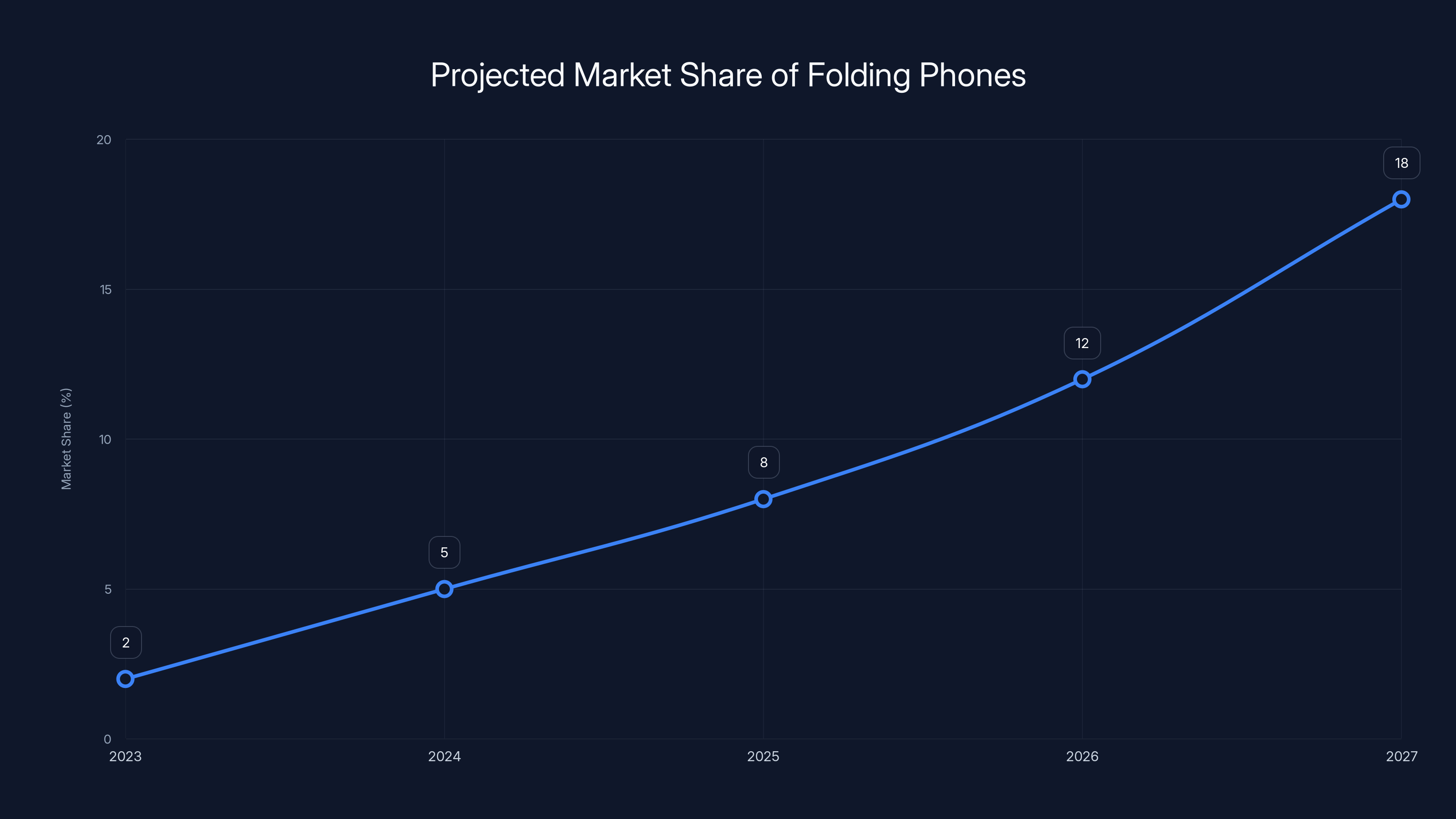

Folding phones are projected to increase their market share from 2% in 2023 to 18% by 2027 as technology matures and prices decrease. Estimated data.

The Rise of Bold Alternatives: Motorola, OnePlus, and the Underdog Effect

While Apple and Samsung play it safe, other manufacturers are quietly building loyal audiences through personality.

Motorola has been experimenting with distinctive designs for years. The Moto Edge series uses curved glass that wraps around the edges in ways that feel different from the flat glass standard. It's not revolutionary, but it demonstrates that alternative approaches don't require engineering magic—just willingness to deviate from convention.

OnePlus built their entire brand on the principle that flagship phones should cost

These brands haven't captured mass market share, but they've captured mindshare. They've shown that there's a viable business model for being different.

The Personality Factor

What separates these brands from Apple and Samsung isn't just design—it's willingness to take opinions. Motorola releases phones with distinct color schemes that don't appeal to everyone, but feel intentional. OnePlus uses software interfaces that don't adhere to Android conventions. Nothing designs transparent phones that some people find impractical but most find refreshing.

Apple and Samsung try to be inoffensive to everyone, which makes them inoffensive to anyone. There's a market inefficiency here. By trying to maximize market share, they've surrendered distinctive brand identity.

Why Underdogs Can Afford Risk

Motorola has nothing to lose. They're not the market leader. Their shareholders aren't expecting them to capture 25% market share. They can experiment. When an experiment fails, it affects a smaller user base. When it succeeds, it builds brand loyalty among customers who feel heard.

Apple and Samsung, by contrast, have global supply chains supporting billions in annual revenue. Every decision gets vetted by risk committees. Manufacturing changes require retooling factories that cost hundreds of millions. The organizational inertia is enormous.

This creates a structural advantage for challengers. They can move faster, take bigger risks, and build brand affinity through distinctiveness. The market leader responds with incremental improvements that feel increasingly disconnected from what customers actually want.

Material Science and Durability: Where Innovation Actually Matters

Here's something interesting nobody talks about: phones have gotten worse in some practical ways while staying the same in others.

Modern flagship phones are thinner but more fragile. Glass backs shatter easily. Even small drops can crack screens. Apple's "Ceramic Shield" is harder than typical glass, but it's still not durable enough to survive real-world use without a case. Most people carry their $1,200 phone inside a thick protective case that completely obscures whatever design effort went into the device.

This is backwards. If manufacturers spent less time optimizing thinness and more time optimizing durability, they could create genuinely better products that feel better to use.

The Case Problem

Think about the absurdity: companies spend millions designing beautiful phones, then most customers immediately wrap them in protective cases. The design becomes invisible. The premium materials are hidden. All the aesthetic effort becomes pointless.

Why? Because phones are fragile. A 2-foot drop can destroy a $1,200 device. That shouldn't be normal. The durability standards for consumer electronics are shockingly low.

Imagine if instead, manufacturers optimized for drop resistance. Used materials that don't shatter. Designed phones to be slightly thicker and heavier but capable of surviving drops from hand height. Most people wouldn't need cases anymore. The distinctive design would be visible. The premium materials would actually be felt and seen.

None of this is technically impossible. It's a choice to prioritize thinness and perceived premium feel over practical durability.

Material Alternatives Worth Exploring

Some manufacturers are experimenting with alternatives to glass. Motorola has used plastic backs on some models. OnePlus has experimented with leather and alternative materials. These aren't revolutionary, but they point toward a different philosophy: what if we optimized for feel and durability instead of reflectiveness and thinness?

Glass looks premium but feels cold and fragile. A well-designed plastic or composite material could feel better in hand and be more durable. But focus groups prefer glass because glass looks expensive. So manufacturers default to glass and durability suffers.

The most interesting material innovation is happening in repairability. Framework Computers showed that you can build premium devices that are also repairable. Phone manufacturers could do the same—design phones that are easy to disassemble, with replaceable batteries and screens. But that would enable people to keep phones longer, which would reduce upgrade cycles and annual revenue.

There's no technical barrier. It's purely a business model choice.

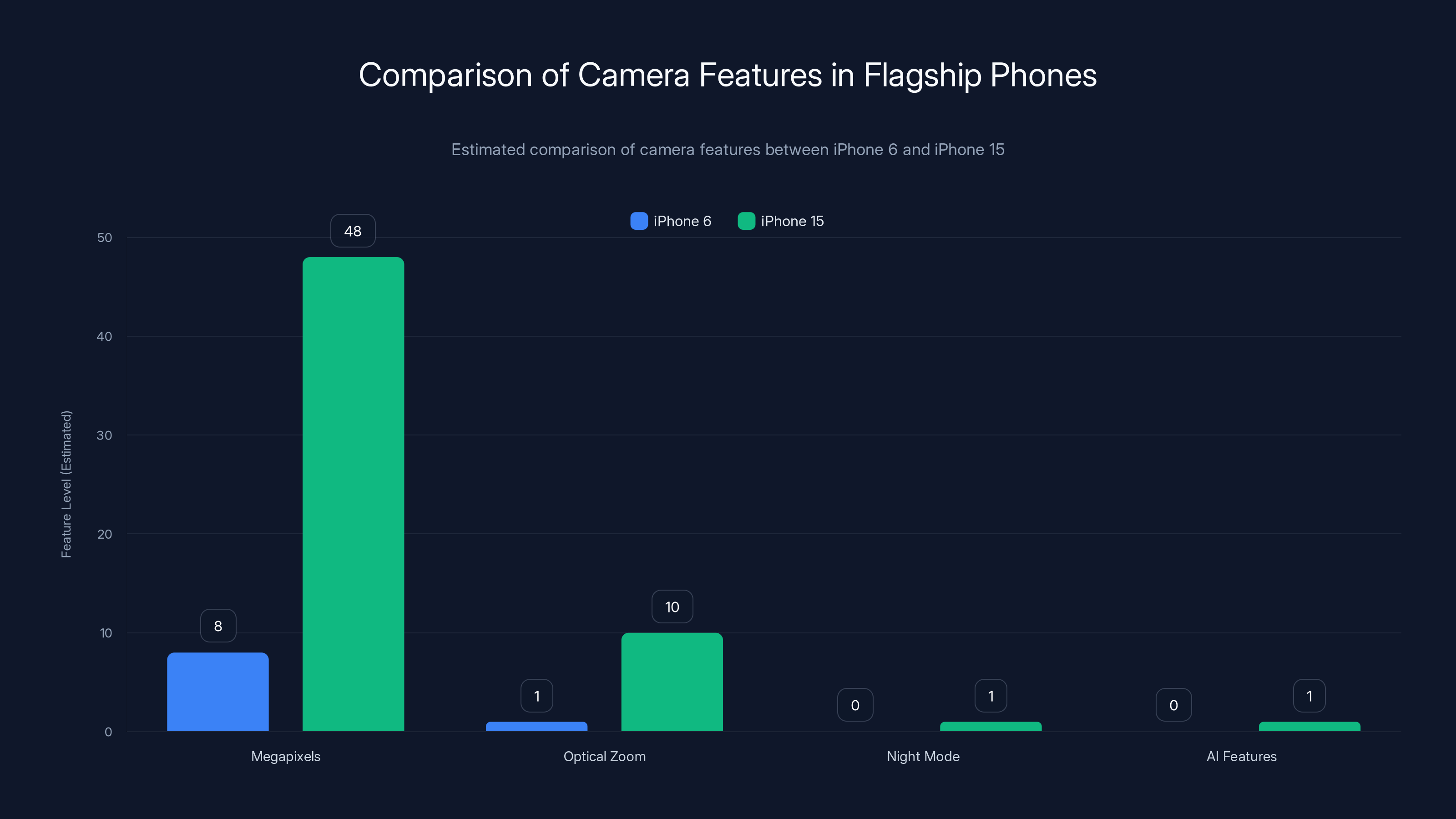

Estimated data shows the significant increase in camera features from iPhone 6 to iPhone 15, highlighting the trade-off between design and specs.

The Software Design Problem: UI Stagnation

Hardware isn't the only place where smartphone design has stalled. Software interfaces have remained essentially unchanged for a decade.

Android phones still use app grids and notification panels that wouldn't surprise someone from 2015. iPhones have slightly evolved the home screen but maintained the same fundamental interaction model. The lock screen is still primarily for showing time and notifications. Gesture controls exist but remain hidden and under-documented.

What iOS 16 and Android 14 Got Right (And Mostly Wrong)

When Apple introduced the dynamic island on iPhone 14 Pro, it was genuinely clever. Taking the notch—a constraint that nobody wanted—and turning it into interactive UI was smart design. But it was also a Band-Aid. Apple took an engineering limitation and made lemonade instead of redesigning the camera system to avoid the limitation entirely.

Android's customization philosophy should theoretically lead to more distinctive software experiences. Some manufacturers try. One UI (Samsung) looks different from Pixel Experience (Google) looks different from Oxygen OS (OnePlus). But the differences are cosmetic. The interaction model is identical.

What's missing is fundamental rethinking about how people actually use phones. We spend 3-4 hours daily on smartphones, yet the interface design hasn't evolved substantially since 2010. We still tap tiny app icons. We still swipe in predefined gesture patterns. We still experience content in vertical scrolls optimized for novelty feeds rather than depth and focus.

The Customization Opportunity

Nothing's approach with the Glyph interface suggests a different direction. What if phones could adapt their interface to individual needs? The back of the phone becomes a secondary interface. You could customize which apps get light patterns. Different light intensities for different notification priorities. The lock screen becomes genuinely personalized instead of generic.

Apple's lock screen customization was a step toward this but implemented in ways that feel like an afterthought. You can change colors and widgets, but the core interaction model is unchanged. Imagine if the lock screen actually solved problems: instantly showing you the weather because you check it first thing in the morning; displaying your calendar because most of your day is scheduled; showing your fitness data because you track it constantly.

Software innovation requires design thinking—understanding user behavior deeply and then designing interfaces around actual needs instead of theoretical possibilities.

Why Annual Release Cycles Kill Innovation

The most underrated factor in smartphone design stagnation is the calendar.

Manufacturers commit to annual product launches roughly 2 years in advance. Designers begin prototyping ideas 3 years before launch. By the time a phone ships, the design decisions are 3 years old. During those years, other challenges emerge, engineering constraints tighten, and market research indicates that people prefer safer designs.

This timeline creates massive inertia. If Samsung decided tomorrow that they wanted to redesign the Galaxy completely, they couldn't do it for 2024. The 2025 lineup is already locked. The earliest a radical rethink could ship is 2026, assuming nobody runs into major engineering obstacles (which they definitely will).

Apple operates on a similar timeline. The iPhone 15 design was finalized in 2021. By 2021 standards, it made sense. By 2024, it felt dated. The iPhone 16 will ship in 2024 with designs finalized in 2022. This creates a perpetual situation where flagship phones feel slightly behind the curve.

The Upgrade Cycle Problem

Annual releases create artificial scarcity. There's always a new model coming in 12 months. That encourages upgrade behavior that isn't driven by genuine need but by calendar dates. Someone with a perfectly functional iPhone 12 sees the iPhone 15 launch and feels like they should upgrade because it's the new thing.

If instead manufacturers released phones when they were ready (every 18-24 months for major refreshes), two positive things would happen:

- More time for engineering exploration and radical design iteration

- More realistic upgrade messaging focused on actual improvements rather than calendar-based cycles

People would upgrade when their current phone genuinely couldn't meet their needs. That might extend the average phone lifespan from 3-4 years to 5-6 years. For manufacturers, that means lower volume but potentially higher margins and more loyal customers who feel like their devices were worth the investment.

Foldable phones like the Galaxy Z Fold are nearly twice as expensive as traditional flagship phones, highlighting a significant price barrier for consumers. Estimated data based on typical market prices.

The Camera Trap: Design Compromised for Specs

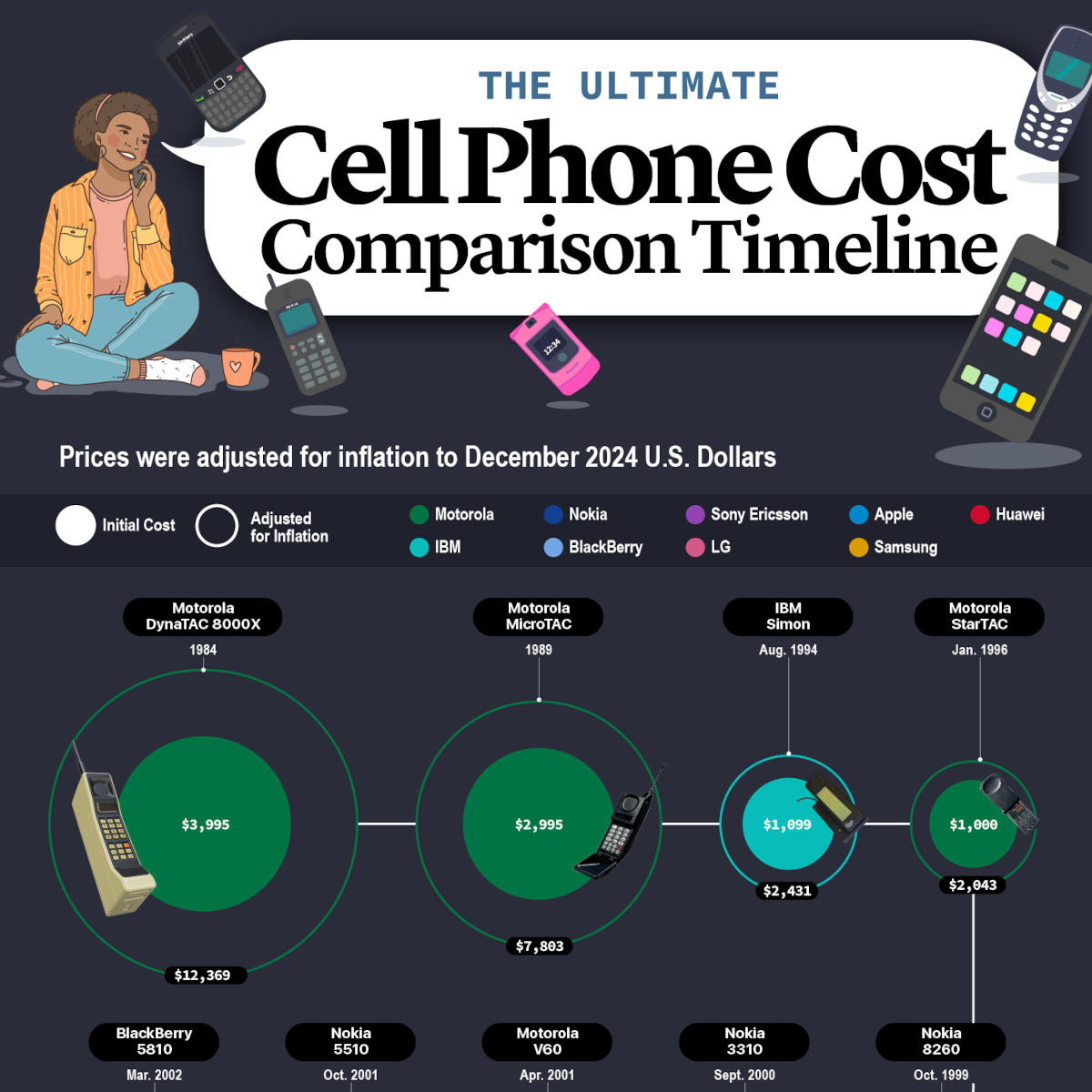

Camera systems have become the primary differentiator for flagship phones. Apple and Samsung compete on megapixels, optical zoom, computational photography, and AI enhancement. This competition has created increasingly large camera bumps that dominate phone aesthetics.

Compare the iPhone 6 to the iPhone 15. The original iPhone had a simple, elegant circular camera module. Modern iPhones have a large protruding bump housing multiple lenses and sensors. The design has become dominated by this functional requirement.

Larger sensors require larger optics. Multiple focal lengths mean multiple lenses. Thermal concerns from computational processing require engineering space. The camera tail wags the phone dog.

When More Isn't Better

Here's the frustrating part: most people don't need the computational photography that modern flagship cameras offer. They want a phone that takes good photos in normal lighting. A basic 48-megapixel sensor with good processing would be sufficient for 95% of use cases.

But flagship marketing emphasizes specs. "100x zoom!" "Advanced night mode!" "AI scene detection!" These sell phones. The actual benefit of these features versus mid-range alternatives is marginal for typical users.

What if a manufacturer designed a flagship phone where the camera system fit smoothly into the body? Where it didn't protrude? Where the back of the phone was actually flat and elegant? You'd have to make tradeoffs: maybe limit optical zoom to 2x instead of 10x. Accept that night mode is good but not best-in-class. Use a 48-megapixel sensor instead of 108 megapixels.

Would the vast majority of customers notice? No. Would the phone be more durable and better looking? Absolutely.

Manufacturers optimize for reviewers' camera benchmarks instead of user experience. Reviewers care about zoom range and night mode performance. Users care about taking decent photos without their phone looking ridiculous.

Color and Finish: Why All Phones Look Like This

One of the easiest ways to make phones more interesting would be to offer genuinely different color and finish options. Instead, the industry has converged on a narrow palette: black, white, silver, gold, sometimes a muted blue or green.

Why? Because these colors are safe. They appeal to the broadest audience. They photograph well. They hide fingerprints reasonably well. They feel expensive (especially black and white). Focus groups approve of them.

But the cumulative effect is that entering an Apple Store or Samsung counter means looking at dozens of phones that differ only in processor and screen size. The design language is identical.

The Motorola Moto Edge Counterexample

Motorola has been less conservative with color options. They offer distinctive options like "Forest Green" and "Stellar Black" with different finishes. These aren't revolutionary, but they signal that the company thinks about color as part of design rather than an afterthought.

None of these colors will appeal to everyone. That's the point. Good design makes intentional choices rather than trying to please everyone.

Apple released the (Product)Red iPhone which was genuinely distinctive. The color was vibrant, intentional, and felt different. It sold well. Yet Apple doesn't extend this philosophy broadly. You can get (Product)Red only in specific models. The standard color palette remains conservative.

Matte Finishes and Texture

Apple introduced matte finishes on iPhone 12 Pro, which was genuinely better than the previous generation's glossy back. Matte finishes resist fingerprints, feel better in hand, and are more durable. It's a clear win.

Yet the standard colors still feature glossy glass on most models. Matte finishes are relegated to premium tiers. This is backwards. Matte should be standard. Glossy should be the premium option if anything.

The point is that small finish choices make enormous differences in daily experience, yet manufacturers treat them as low-priority details rather than core design elements.

Estimated data shows that while traditional designs dominate the market, innovative designs and emerging competitors are gaining traction, indicating potential shifts in consumer preferences.

Battery Capacity: The Unspoken Design Choice

Here's something that drives me crazy: phone battery capacity has barely improved in 5 years despite significant advances in battery chemistry.

The iPhone 12 had a 2,815 mAh battery. The iPhone 15 has a 3,582 mAh battery. That sounds like good improvement until you realize that phones got slightly larger and processors got much more efficient. The battery-to-phone-size ratio is nearly identical.

Samsung's Galaxy S10 had a 4,000 mAh battery. Galaxy S24 has a 4,000 mAh battery. Same capacity, similar size. The efficiency improvements have gone entirely toward maintaining similar battery life rather than extending it.

The Thinness Problem Again

This comes back to the obsession with thinness. A phone could easily have a 5,000-6,000 mAh battery without being significantly thicker. Most people would prefer a phone that lasts 2 days to a phone that's 1mm thinner.

Yet manufacturers prioritize thinness, which requires holding battery capacity roughly constant. This is a design choice with no engineering necessity. It's a choice driven by marketing perception that "thin equals premium."

Battery life is arguably more important than processing speed for actual user satisfaction. A flagship phone with 18-hour battery life would be notably better than a flagship with 12-hour battery life, even if the processor was slightly slower. But nobody markets phones this way because battery capacity doesn't photograph well in advertisements.

Fast Charging as a Crutch

Manufacturers compensate for limited capacity with fast charging. 120W charging allows you to refill a small battery quickly. But charging generates heat, degrades battery health over time, and requires carrying a charger everywhere.

What if instead phones came with enormous batteries and moderate charging speeds? A 6,000 mAh battery at 30W charging would outlast any realistic daily use and charge overnight without degradation concerns.

Again, this is possible today. It's simply not prioritized because marketing teams believe thin phones sell better than practical phones.

The Ecosystem Lock-in Problem

One often-overlooked reason that phones have become boring is that the ecosystem creates switching costs so high that manufacturers don't need to compete on design.

If you own an iPhone, you're invested in iTunes, iCloud, Apple Watch integration, AirDrop, Handoff, and dozens of other integrated services. Switching to Android means losing all that integration. The cost of switching is measured in hours of reconfiguration and lost functionality.

Samsung created One UI to lock people into the Galaxy ecosystem. Apple's ecosystem lock-in is even more comprehensive. Google is building this with Google One and Play ecosystem integration.

When customers are locked in by ecosystem, manufacturers can de-prioritize design innovation because switching costs already keep people from leaving. A customer with 5 years of iCloud photos, App Store apps, and Apple Watch integration isn't leaving for an Android phone that looks better. The ecosystem friction is too high.

Why This Kills Innovation

Without serious switching cost pressure, there's no incentive to innovate on design. The incumbent can just iterate. Customers stay because leaving is annoying, not because they're genuinely satisfied with the product design.

This is why challengers like Nothing and OnePlus can build momentum—they're attracting customers who haven't yet built heavy ecosystem investment. Once you've bought in, leaving becomes harder. The incumbent uses that lock-in to reduce pressure on product innovation.

The smartphone market would be far more dynamic if ecosystems were less sticky, forcing manufacturers to compete on design and user experience rather than relying on switching costs.

What Manufacturers Should Actually Do

If Apple, Samsung, and others wanted to make phones interesting again, the path is clear. It doesn't require new technology. It requires different priorities.

Prioritize Durability Over Thinness

Make phones 2-3mm thicker and engineer them to survive drops from 2 meters onto concrete. Use materials that don't shatter. Design with durability as the primary constraint instead of afterthought. Most people don't carry cases around premium designs anymore—they hide them. Eliminate that need and people will actually see the design.

Extend Battery Capacity

A 6,000-7,000 mAh battery would transform daily phone usage. Two full days of moderate use without charging fundamentally changes how you relate to the device. This isn't revolutionary technology. It's a design choice.

Design Distinctive Software Experiences

Android manufacturers should lean harder into customization. Create UI that feels significantly different from stock Android. iPhones should stop pretending to have customization and either commit to it or stop offering customization options that mostly feel pointless.

Extend Release Cycles

Commit to major redesigns every 2-3 years instead of annual refreshes. Between major releases, offer modest spec bumps without changing the design. This gives design teams time to explore radical ideas without quarterly pressure forcing compromises.

Take Color Seriously

Offers colors that make intentional statements. Not every color option needs to appeal to everyone. Let some phones be aggressively colorful. Let some be minimally aesthetic. Let design philosophy guide the palette instead of market research.

Rethink Camera Systems

Optimize for practical photography instead of benchmark specs. 48MP with great processing beats 108MP with mediocre processing for actual users. Limit optical zoom to 2-3x and lean into computational zoom. Flat back panels are worth more than 10x zoom capability for the majority of use cases.

The Foldable Future (Maybe)

Folding phones might eventually become mainstream, but not until the technology matures significantly and the use case is clearer than it currently is.

Next-generation folding phones need to solve several problems: the crease needs to become invisible or accepted as a design element rather than a flaw; the hinge needs to be genuinely durable (thousands of folds without failure); the price needs to come down to

Samsung is moving in the right direction, but we're probably 3-5 years away from foldables that feel truly practical rather than specialized. By then, they might capture 10-20% of the market instead of current 5%.

The real innovation window for folding phones is software. Hardware is mostly solved. The software experience of having three apps open simultaneously in a tablet mode is awkward because Android apps weren't designed for it. When manufacturers solve that problem—creating truly functional multitasking on unfolded screens—foldables will become compelling for mainstream users.

What Consumers Actually Want

This is the real insight that manufacturers miss. When asked what they want in a new phone, most people don't say "more powerful processor" or "slimmer design." They say:

- "Battery that lasts all day without worrying"

- "Screen that's bright enough to use in sunlight"

- "Something that doesn't break when dropped"

- "A design that looks different from everyone else's phone"

- "Faster updates and security support"

- "Affordable without being cheap"

None of this requires revolutionary technology. It requires prioritizing user experience over specification marketing.

Apple understands this in some domains. AirPods succeeds because they prioritize seamless pairing and reliable connection over the specs audiophiles care about. Apple Watch succeeds because it solves practical problems (notifications, fitness tracking, payments) rather than trying to be a tiny iPhone.

But iPhones themselves have abandoned this philosophy. Specification marketing has taken over. The same thing happened with Samsung's Galaxy phones.

The Emerging Companies Challenge

Nothing's success has inspired other emerging brands to take design seriously. Fairphone focuses on repairability and sustainability. Google Pixel (under new leadership) is emphasizing AI integration in thoughtful ways rather than just bolting features on. OnePlus continues building distinctiveness through clean software and bold color options.

None of these companies will overtake Apple or Samsung in total market share. But they're proving the market for alternative philosophies exists. That pressure might eventually force incumbents to reconsider their approach.

The question is whether it happens before the market becomes so consolidated that only ecosystem leaders can survive. Right now, we're probably in the middle of that transition. Within 5 years, expect significant consolidation. The survivors will be companies that either offer radical differentiation or represent a specific ecosystem.

Design as Philosophy, Not Marketing

The core issue is that smartphone design has become treated as a marketing problem rather than a philosophical problem. Manufacturers ask: "What design elements will make this look expensive?" and "What colors will appeal to the broadest demographic?" Instead of asking: "What phone would I actually want to use for 5 years?"

Nothing's approach starts with philosophy: "Let's celebrate the engineering through transparency. Let's make the interior visible because it's beautiful." That's a design philosophy. The consequences flow from it: unique aesthetic, different interaction model, bold materials.

Apple used to design this way. Jonathan Ive led design philosophy driven by ideas like "simplification" and "harmony between form and function." Modern Apple design seems driven by "what's the minimum change we can make and still justify a new generation?"

Design philosophy creates something that feels purposeful. Marketing-driven design creates something that feels calculated.

Conclusion: Hope on the Horizon

The smartphone industry is boring right now, but not irreversibly so. The ingredients for change exist:

There's proven market demand for distinctive design (Nothing's success proves this). Technology barriers don't actually exist—phones could be more durable, have better batteries, and look different with current technology. Emerging competitors are validating that alternative approaches work economically. Consumer frustration with incremental updates is growing.

What's required is willingness from major manufacturers to take design risks. That starts with leadership believing that distinctive design matters more than quarterly sales targets. It requires committing to longer development cycles rather than annual refreshes. It means accepting that not every design choice will appeal to 50% of the market—that's okay if it appeals enthusiastically to 15%.

Apple and Samsung won't transform overnight. But the market pressure is building. If they don't innovate on design, challengers will continue capturing more mindshare and slowly building momentum. In 5-10 years, we might see a very different phone landscape where multiple manufacturers compete seriously on design and user experience rather than processor speed and camera megapixels.

For now, if you're frustrated with boring flagship phones, you have options. Nothing, OnePlus, and Motorola are building phones that feel intentional. They're not perfect, but they're trying. And sometimes, trying is enough to make something worth paying attention to.

The phone in your pocket doesn't have to be a generic black rectangle. It doesn't have to iterate marginally from last year's model. It doesn't have to optimize for every possible use case while excelling at none. Manufacturers could choose differently. Some already are. The rest will eventually realize that innovation might sell fewer units to existing customers, but it builds far more loyalty among people seeking something different.

FAQ

Why have smartphones stopped evolving dramatically?

The smartphone market has matured past the inflection point where radical innovation drives sales. Processors from 2021 are still perfectly capable in 2025. Battery life is adequate. Cameras are excellent. Manufacturers discovered that customers will upgrade for incremental improvements, so radical risk-taking becomes unnecessary from a business perspective. Additionally, the annual release cycle locks in designs 2-3 years in advance, making true innovation structurally difficult. Focus groups and market research favor conservative designs over radical experiments, further dampening innovation.

What makes Nothing's design philosophy different?

Nothing started without a reputation to protect or massive market share to maintain, allowing them to take design risks that market leaders can't afford. They approached phone design from first principles: What could we do with the back of a phone that's never been done? This led to transparent panels and the Glyph LED interface. Rather than asking what focus groups prefer, they asked what would be genuinely novel. That willingness to prioritize design philosophy over market-tested safety is what separates them from Apple and Samsung's approach of optimizing for the broadest possible appeal.

Are folding phones the future?

Not in the near term. Current folding phones solve a technology problem that consumers never asked for, with a form factor that creates more problems than it solves (durability concerns, crease visibility, awkward app scaling, extreme pricing). The technology needs 3-5 more years to mature. The real bottleneck is software—Android apps need to be designed specifically for folding rather than just scaling to larger screens. Once that problem is solved and prices drop to

Why do phones need to be so thin?

They don't. The obsession with thinness is a marketing choice driven by the perception that thin equals premium. It's not a technical requirement. A phone that's 2-3mm thicker with double the battery capacity and significantly better durability would objectively be superior for most users. But manufacturers long ago decided that thinness was the design characteristic that would make phones feel expensive, and that decision created a cascade of problems: limited battery capacity, fragile construction requiring protective cases, and thermal management challenges. Breaking this cycle would require manufacturers to intentionally market phones as thicker and more durable, which goes against 15 years of messaging.

Should I upgrade my current phone?

Unless you're experiencing actual problems (battery not lasting a day, crashes, screen damage), you probably don't need to upgrade. Modern flagship phones from 2021-2022 are still perfectly capable in 2025. The upgrades offered by current models are largely marginal. If you do upgrade, consider stepping sideways to a brand with more distinctive design rather than upgrading within the same ecosystem. OnePlus, Nothing, or Motorola devices might provide a more refreshing experience than a standard flagship upgrade path.

What would actually fix smartphone design stagnation?

Several changes could reinvigorate the market: extending release cycles from annual to every 18-24 months to allow more design exploration time, prioritizing durability and battery life over thinness, offering genuinely distinctive color options and materials, designing software experiences specific to each manufacturer rather than using stock Android or minimal iOS tweaks, and rethinking camera system tradeoffs to allow flatter back panels. None of this requires new technology. It requires different priorities and willingness to accept that not every design choice will appeal to the broadest possible market.

Do I need a case for a modern flagship phone?

Unfortunately yes, if you want the phone to survive beyond 1-2 years. Modern flagship phones have poor durability. A 2-foot drop can easily crack the screen or damage the body. This is a design failure—phones should be durable enough to survive normal use without requiring protective cases. The fact that distinctive design gets hidden behind protective cases is a major lost opportunity for manufacturers. If phones were genuinely durable, that expensive design work would actually be visible and appreciated. Emerging brands like Fairphone are trying to address durability, but mainstream flagships still prioritize thinness over practical durability.

Key Takeaways

- Smartphone design has stagnated because Apple and Samsung optimized for incremental updates over radical innovation due to market dominance and quarterly earnings pressure

- Nothing's transparent design and Glyph interface proves consumer demand exists for distinctive aesthetics that flagship manufacturers ignore

- Manufacturers prioritize thinness, processor speed, and camera megapixels while customers actually want durability, longer battery life, and design that looks different

- Annual release cycles lock design decisions 2-3 years in advance, creating structural inertia that prevents rapid innovation and experimentation

- Ecosystem lock-in (iCloud, Play Services, etc.) reduces pressure on incumbents to innovate on design since switching costs keep customers regardless of aesthetic appeal

Related Articles

- Samsung Galaxy Z Trifold Price & Availability [2025]

- Nothing Phone 4 Delayed: What Carl Pei's Strategy Means for 2026 [2025]

- The Perfect Folding Phone Doesn't Exist Yet [2025]

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2025: What to Expect and What Won't Happen [2025]

- This Week in Tech: Apple's AI Pin, NexPhone's Triple OS, and the Sony-TCL Merger [2025]

- OnePlus Denies Demise Rumors: What's Really Happening [2025]

![Why Modern Smartphones Are So Boring (And How to Fix It) [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-modern-smartphones-are-so-boring-and-how-to-fix-it-2025/image-1-1769861418295.jpg)