Why Palmer Luckey Thinks Retro Tech is the Future

When the founder of Oculus and current CEO of Anduril steps on stage at CES to tell you that older technology is objectively better than what we have today, people listen. Especially when he's standing next to a Reddit co-founder who clearly agrees.

That's what happened in January 2025, when Palmer Luckey and Alexis Ohanian gave a joint talk that caught the attention of the entire tech industry. The message was simple but provocative: we've been chasing the wrong direction. The future of technology, they argued, isn't about thinner phones, more AI, or cloud-everything. It's about going backward.

Now, before you dismiss this as pure nostalgia—two successful entrepreneurs pining for the Geocities days—understand what they're actually arguing. Luckey wasn't saying AI is bad (he explicitly said the opposite). Ohanian wasn't calling for a return to dial-up. What they were saying is far more interesting: the design philosophy, the intentionality, and the form factor of vintage tech products are superior to what we're building today. And they might actually be right.

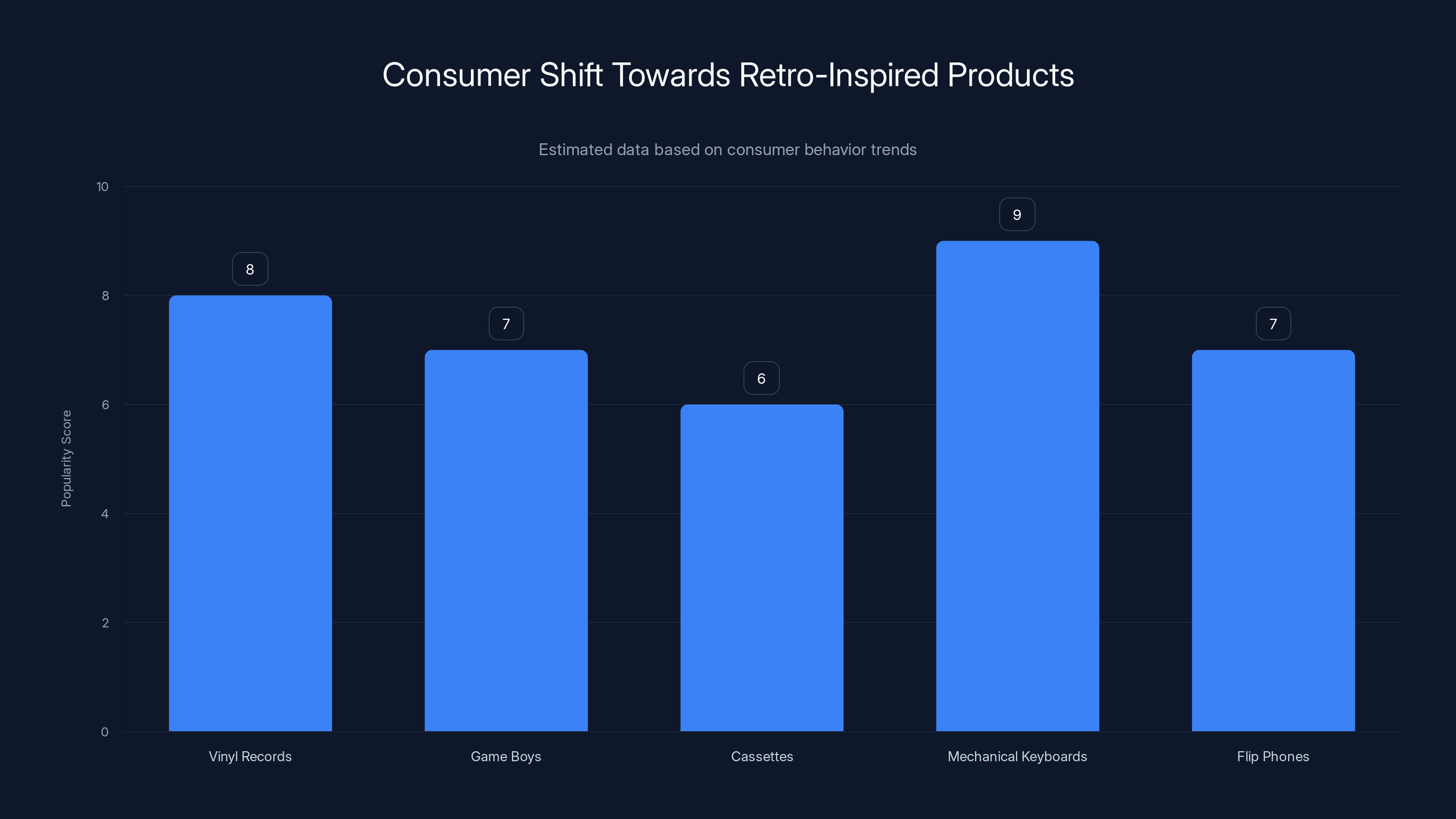

The curious thing is, consumer behavior backs them up. Vinyl sales are the highest they've been in decades. Cassette tapes are making a genuine comeback. People are buying Game Boys from the 1990s. Digital cameras are becoming status symbols. And at CES 2025, there was an entire category of new products that looked like they came from 1995. This isn't a tiny subculture anymore. This is a genuine shift in how people think about the technology they use every day.

So what's really happening here? Is it nostalgia, or is there something deeper at work? And more importantly, what does this mean for the future of tech innovation?

The Case Against Modern Tech Design

Luckey's critique wasn't vague. He pointed to something specific: intentionality. When people built music libraries in the pre-streaming era, they made deliberate choices. You bought albums because you cared about the entire work, or you made mix tapes where every song mattered. Each track was a decision. There was friction, but that friction meant something.

Contrast that with today. You have access to every song ever recorded, instantly, for about twelve bucks a month. Spotify's algorithm decides what you should listen to. Your "Discover Weekly" playlist arrives automatically. You don't choose anymore—you consume. And according to Luckey, you lose something irreplaceable in that transaction.

This isn't just philosophical hand-wringing. There's actual cognitive science behind it. When something requires effort to obtain, you value it more. Psychologists call this the "effort justification effect." When you spent money on an album or took the time to record a mix tape, you were more invested in actually listening to it. Your brain was more engaged because you had skin in the game.

The same logic applies to other technologies. When your phone had physical buttons, you had tactile feedback. You knew when something registered. Today's touchscreens are precise but alienating. You're never quite sure if you've actually pressed something. You tap and wait for feedback. It's a minor thing until you realize it happens hundreds of times per day.

Luckey also highlighted the aesthetics argument, which gets dismissed too easily. But form factor matters. The original Game Boy was chunky, green-screened, and underpowered compared to its competitors. Yet it dominated the market. Why? Because it was made to last. It had a distinctive look. People knew what they were holding. Compare that to modern gaming handhelds, which all look like black rectangles. They're technically superior in every measurable way. But do you remember owning one? Do you feel nostalgic for it?

There's a design philosophy buried in that question. Vintage tech products had personality. They were designed to be owned, held, and loved. Modern products are designed to be replaced.

Ohanian brought receipts to this argument. He kept saying things like, "It's not just about nostalgia for the old; it's objectively better." That's a bold claim, but when you start looking at specific products, you see what he means. The 1999 game Quake Arena is still played competitively today. Modern esports titles come and go. Why? Probably because Quake was designed with obsessive attention to balance and core mechanics, while newer games are designed to sell cosmetics and battle passes.

The intentionality gap between old and new is real.

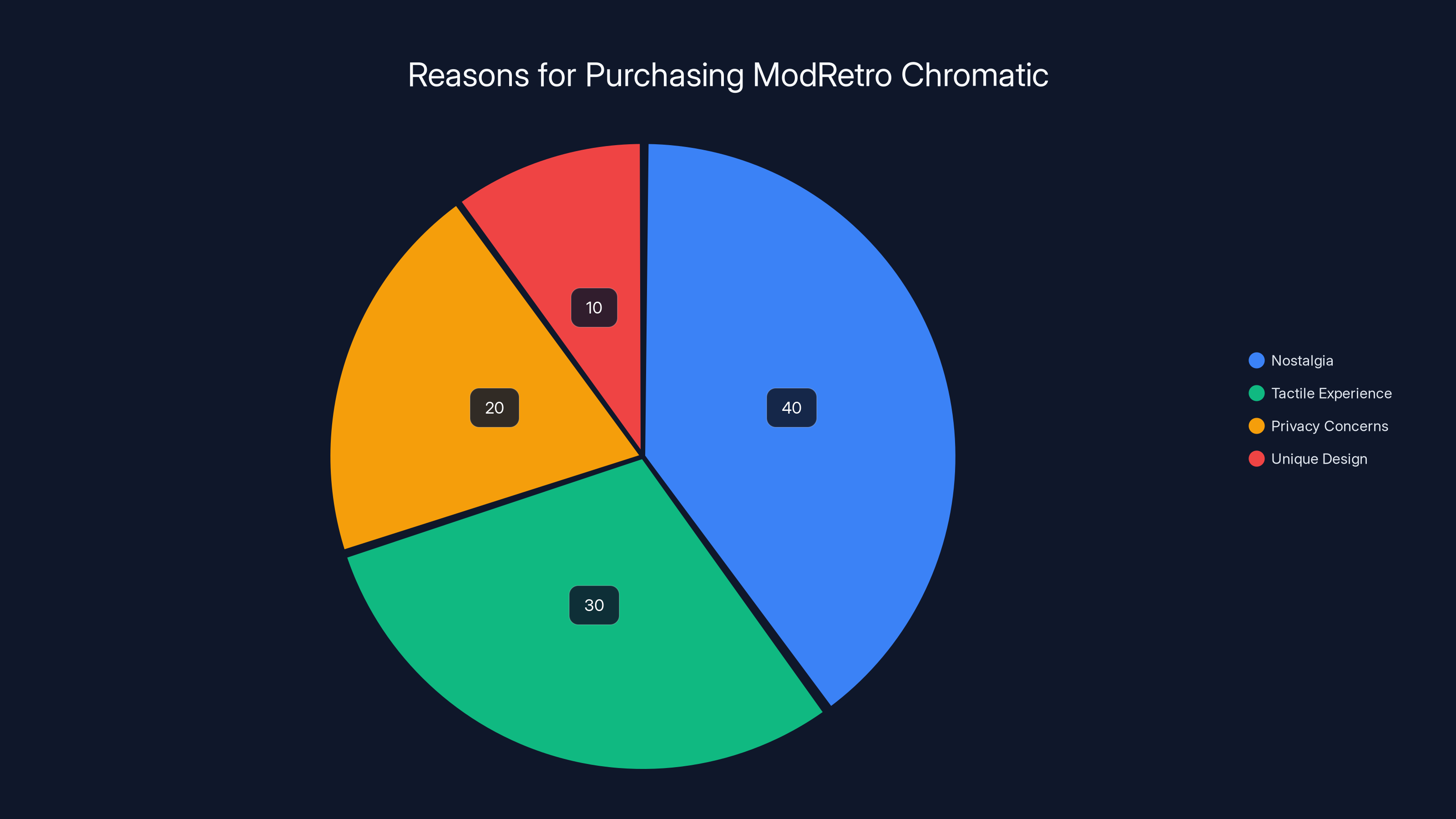

Estimated data suggests that nostalgia is the primary driver for purchasing ModRetro Chromatic, followed by the tactile experience and privacy concerns.

Why Gen Z is Obsessed with Dead Technology

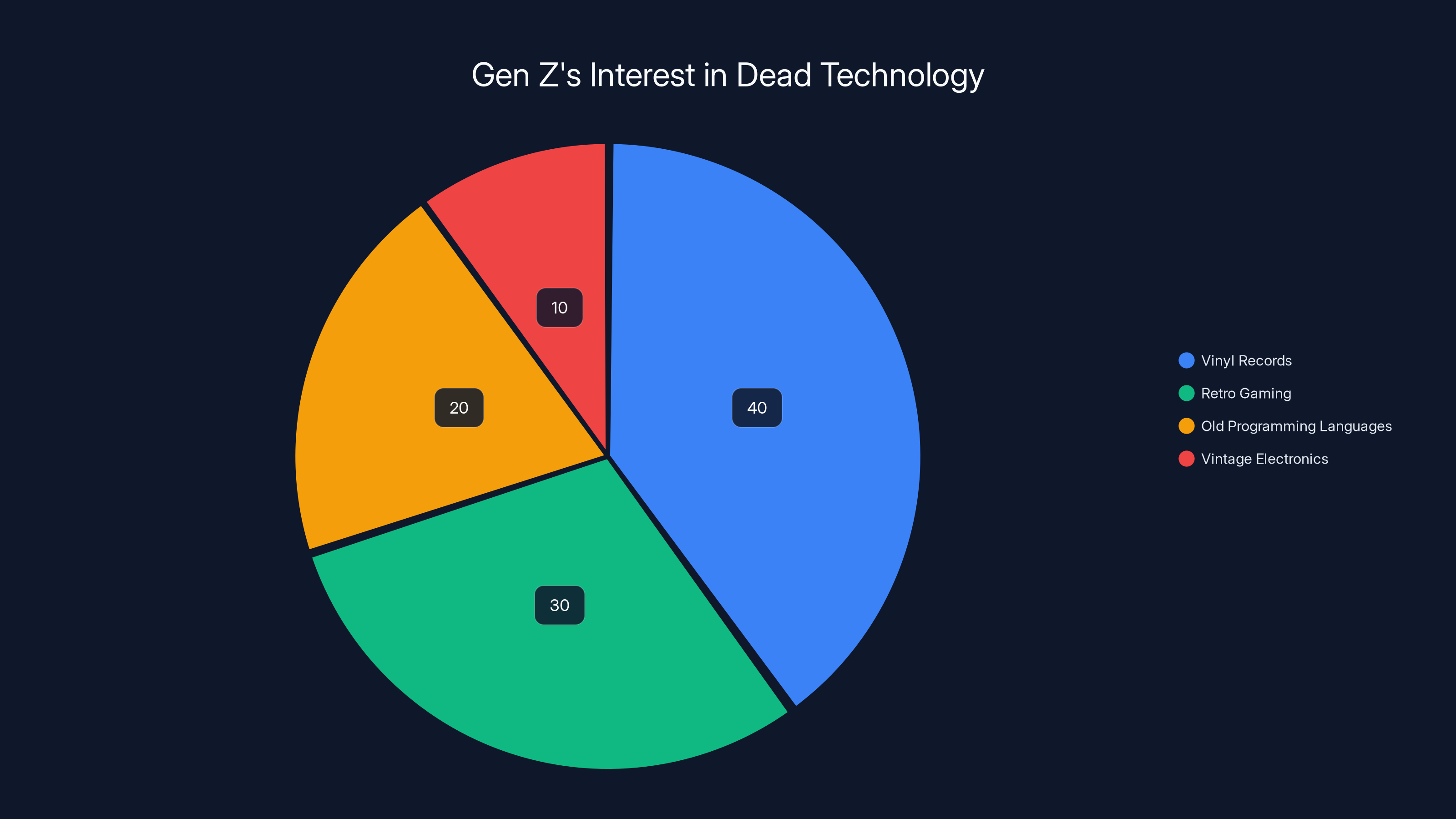

Here's something that genuinely baffled researchers a few years ago: Gen Z kids who were born after the year 2000 are nostalgic for technology and media from the 1980s and 1990s. They weren't alive. They have no personal connection to these eras. Yet they're buying vinyl records, teaching themselves to code in languages from the 1970s, and collecting vintage Game Boys.

Luckey specifically called this out. Why are people—young people, people who never experienced these technologies—convinced they're better? Luckey's answer was straightforward: because they actually are. They're not fooling themselves into liking something they remember fondly. They're recognizing, as outsiders, that these products have qualities that modern products lack.

What's happening is a cultural reckoning. Gen Z has grown up in a world of infinite choice, algorithmic curation, and endless updates. They're oversaturated with content that was optimized to keep them engaged for exactly as long as profitable. They've never experienced a time when you bought something and it just... worked. Forever. No subscriptions, no mandatory updates that broke everything, no ecosystem lock-in.

So they're seeking that out intentionally. Physical media requires no digital rights management. A vinyl record plays the same in 2025 as it did in 1985. No company can revoke your license. No algorithm decides what plays next. That's liberating.

There's also something to be said for the design restraint of old products. When manufacturing was expensive and screens were limited, you had to be clever. The original iPod UI was genius because it had to be. Modern apps are bloated because "cloud infrastructure is cheap." But that cheapness creates bloat. Every product now tries to be seventeen things. Your device is slower and more confusing as a result.

Older products did one thing, and they did it exceptionally well. Your camera took photos. Your phone called people. Your music player played music. That simplicity was enforced by technical limitations, but it created better products.

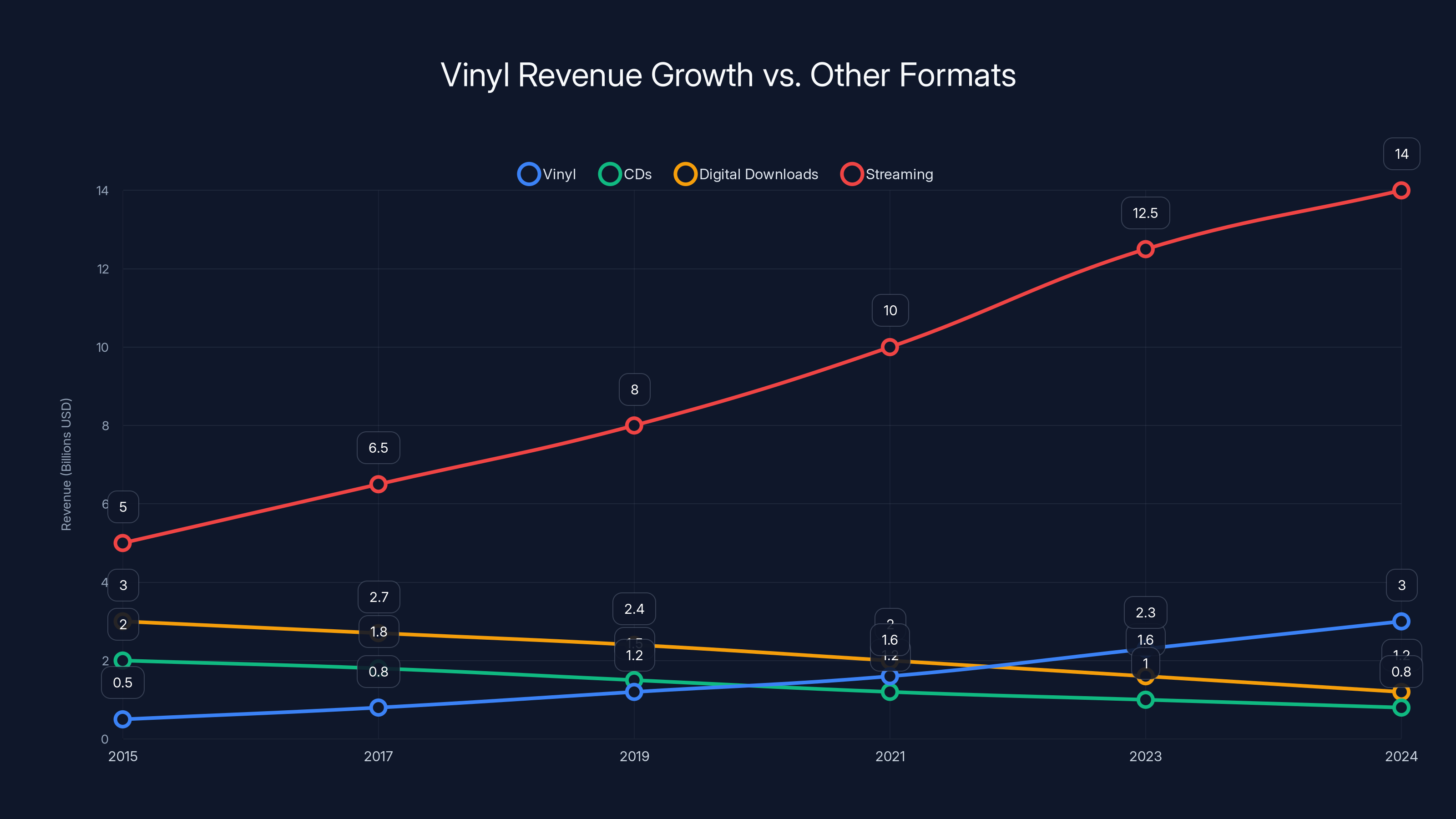

Vinyl revenue has shown significant growth since 2015, surpassing CDs and digital downloads by 2024, second only to streaming. Estimated data.

The Mod Retro Chromatic and the Nostalgia Business

Luckey isn't just talking about this stuff philosophically. He's building products around it.

In 2024, Anduril (Luckey's defense and aerospace company, which is worth

What's interesting about Mod Retro Chromatic isn't that it's retro. It's that people want it. There are dozens of ways to emulate Game Boy games on a modern phone or computer. Most of them are free. But people would rather pay $199 for a device that looks and feels like what they remember.

Why? Because the experience matters. When you hold a modern phone and play an emulator, you're playing a Game Boy game on a glass rectangle that connects to the internet and monitors your behavior. The context undermines the experience. With Mod Retro, you get the tactile feedback, the distinctive shape, the limited but intentional feature set. You're not being targeted by ads while you play. You're not getting notifications. You're just playing a game.

This is why Luckey's been quietly building a business around this stuff. He clearly sees where consumer sentiment is moving. As people get more frustrated with algorithmic feeds, subscription models, and the general surveillance apparatus of modern consumer tech, they're going to reach for alternatives. Retro products fill that gap.

Ohanian has been even more vocal about this. He's mentioned being interested in creating vintage-style games himself. Why? Because there's a market. Millions of people are actively seeking products that operate on principles from 30 years ago. That's not a niche. That's a movement.

The Clicks Communicator and a New Category of Devices

At CES 2025, there was a specific product that exemplified what Luckey and Ohanian were talking about: the Clicks Communicator. It's a phone with a physical keyboard. A real one, not an on-screen simulation. It's designed to do communication tasks and very little else. It's not smart in the modern sense. It doesn't connect to the App Store. It doesn't track your behavior.

Fifteen years ago, this would have been considered obsolete. A phone with a keyboard but no touchscreen, no apps beyond messaging? Who would want that?

Yet Clicks got significant media attention, and people pre-ordered it in meaningful numbers. Why? Because it solves a real problem that modern smartphones create. Your phone is too capable. It's designed to be a distraction. The Clicks Communicator removes that possibility by design. You can't endlessly scroll because there's no scrolling mechanism. You can't get notifications because there's no notification system.

This is the product category that emerges from Luckey and Ohanian's philosophy. Not devices that replicate old technology exactly, but devices that bring back the specific advantages of old technology while acknowledging we live in 2025.

It's the best of both worlds. Physical keyboards like the Clicks uses are actually more ergonomic for typing than touchscreens. They provide better tactile feedback. They're more accessible for people with motor control issues. We didn't switch to touchscreens because they were better. We switched because they were cheaper to manufacture at scale. Technology improved manufacturing, so we made products thinner and more fragile.

The Clicks Communicator suggests that consumers are willing to accept slightly less thin, more specialized devices if it means a better actual experience. That's a fundamental shift in how people are thinking about technology purchases.

Estimated data shows Gen Z's strongest interest is in vinyl records, followed by retro gaming. Estimated data.

The Geopolitical Context Nobody Talks About

Luckey made an interesting aside during his CES talk that didn't get much attention. He said: "I was part of the problem for a long time, making all of my stuff in China." Then he went into a brief geopolitical analysis about US-China relations and explained why manufacturing is becoming more localized.

This matters for the retro tech conversation more than people realize. Historically, the reason we switched from physical buttons to touchscreens, from replaceable batteries to soldered ones, from modular designs to all-in-one sealed devices, was cost. Manufacturing everything in China at massive scale made it cheaper to produce one unified design than multiple variants. Tooling costs became negligible when you're making 100 million units.

But supply chain assumptions are changing. If manufacturing becomes more regional or localized, the economics shift. Suddenly, modularity becomes valuable again. Having replaceable parts reduces waste and costs. Having physical buttons becomes viable because you're not betting everything on one global manufacturing strategy.

Luckey was hinting at something bigger: the retro tech movement might be enabled by fundamental shifts in global manufacturing and supply chain strategy. Companies that tried to optimize for a single global supply chain are now dealing with disruption. Companies that build for regional manufacturing and local repair are becoming more resilient.

From a business perspective, this is massive. It means the next generation of devices might not all be engineered for the Apple-level of planned obsolescence. Repairability becomes a feature. Upgradeable components become possible again. You might actually be able to replace a battery in your phone without sending it to a certified repair center.

That's not retro. That's actually forward-thinking, even though it resembles older design principles. It's called "right-to-repair," and it's gaining real regulatory and consumer traction in 2025.

Why AI Doesn't Change This Conversation

One thing Luckey made very clear: he's not anti-AI. He explicitly stated that AI is changing workflows for the better and that he supports it. So this isn't a luddite argument. It's not "old tech bad, new tech good" or vice versa.

It's much more subtle. It's about where the value is actually coming from. AI might be incredibly useful for data analysis, pattern recognition, and automating repetitive tasks. That's real value. But that doesn't change the fundamental problem with modern consumer tech design. It doesn't make your phone less addictive. It doesn't make your notifications less intrusive. It doesn't restore intentionality to the way you consume media.

If anything, AI makes the problem worse in the short term. AI-powered recommendation algorithms are even more effective at keeping you engaged. Machine learning models are even better at figuring out what will make you stay in an app for one more hour. The most advanced AI technology in consumer products is being used to optimize for engagement metrics and advertising revenue, not for user wellbeing.

So the retro tech movement isn't about rejecting innovation. It's about rejecting a specific business model. It's about saying: your AI-powered recommendation system is actually worse for me, even if it's technologically impressive.

This opens up an interesting space for AI actually. What if AI was used to remove friction instead of add it? What if machine learning was deployed to make your device simpler, not more complex? What if algorithms learned to shut themselves off instead of maximize engagement?

That kind of AI would probably be more valuable than the current generation, even if it's less technologically impressive. But it would require companies to optimize for user wellbeing instead of engagement metrics. And that's a much bigger change than any algorithm.

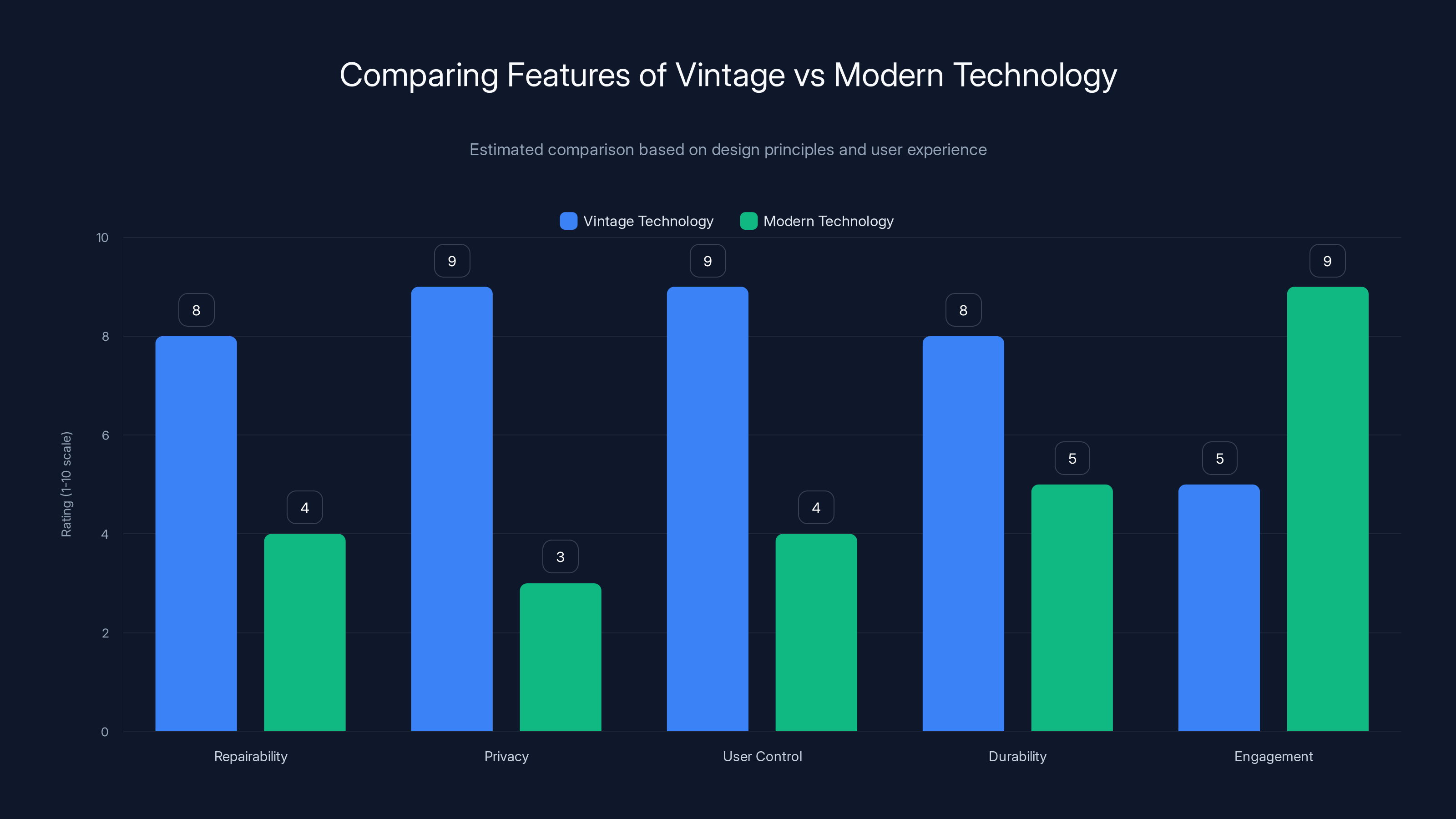

Vintage technology scores higher in repairability, privacy, user control, and durability, while modern technology excels in engagement. Estimated data based on discussed principles.

The Vinyl Renaissance as a Case Study

Vinyl records are back. This isn't speculation or niche data. In 2024, vinyl generated more revenue than any recorded music format except streaming. We're talking about billions of dollars spent on circular pieces of plastic that require special equipment to play and sound worse in objective technical terms than digital formats.

Why? Every research study on this topic points to the same factors. People value the ritual. Putting on a record is intentional. You walk to your music collection, choose an album, place it on the turntable, and listen to the whole thing. You're not passively consuming. You're actively engaging with music.

There's also something about the artifact. A vinyl record is ownership. You own the physical object. You can sell it, trade it, gift it. With streaming, you own nothing. You're renting the right to listen for as long as you pay your subscription and the company remains solvent. If Spotify goes out of business (unlikely but technically possible), your entire music library vanishes.

With vinyl, that's impossible. You own it. That creates a different relationship with the medium.

The vinyl renaissance also created entirely new product categories. Turntables from companies like Rega, Technics, and Audio Technica are selling at price points that would have seemed insane ten years ago. Vinyl is commanding premiums that make manufacturing economics weird. It's less profitable to press vinyl than to stream digital, yet people are doing it because they value the format.

This contradicts everything we learned about technology adoption in the 20th century. We thought formats always trended toward convenience. Tape to CD to MP3. Landline to mobile. Physical mail to email. The trend was always toward efficiency and accessibility.

But somewhere around 2015, consumer behavior started reversing in specific categories. People started keeping their old formats even after new ones emerged. They started buying old formats anew. Not out of habit, but out of preference.

That's a fundamental shift. It suggests that convenience isn't always what people want. Sometimes they want friction. Sometimes they want to be forced to engage more intentionally with what they're consuming.

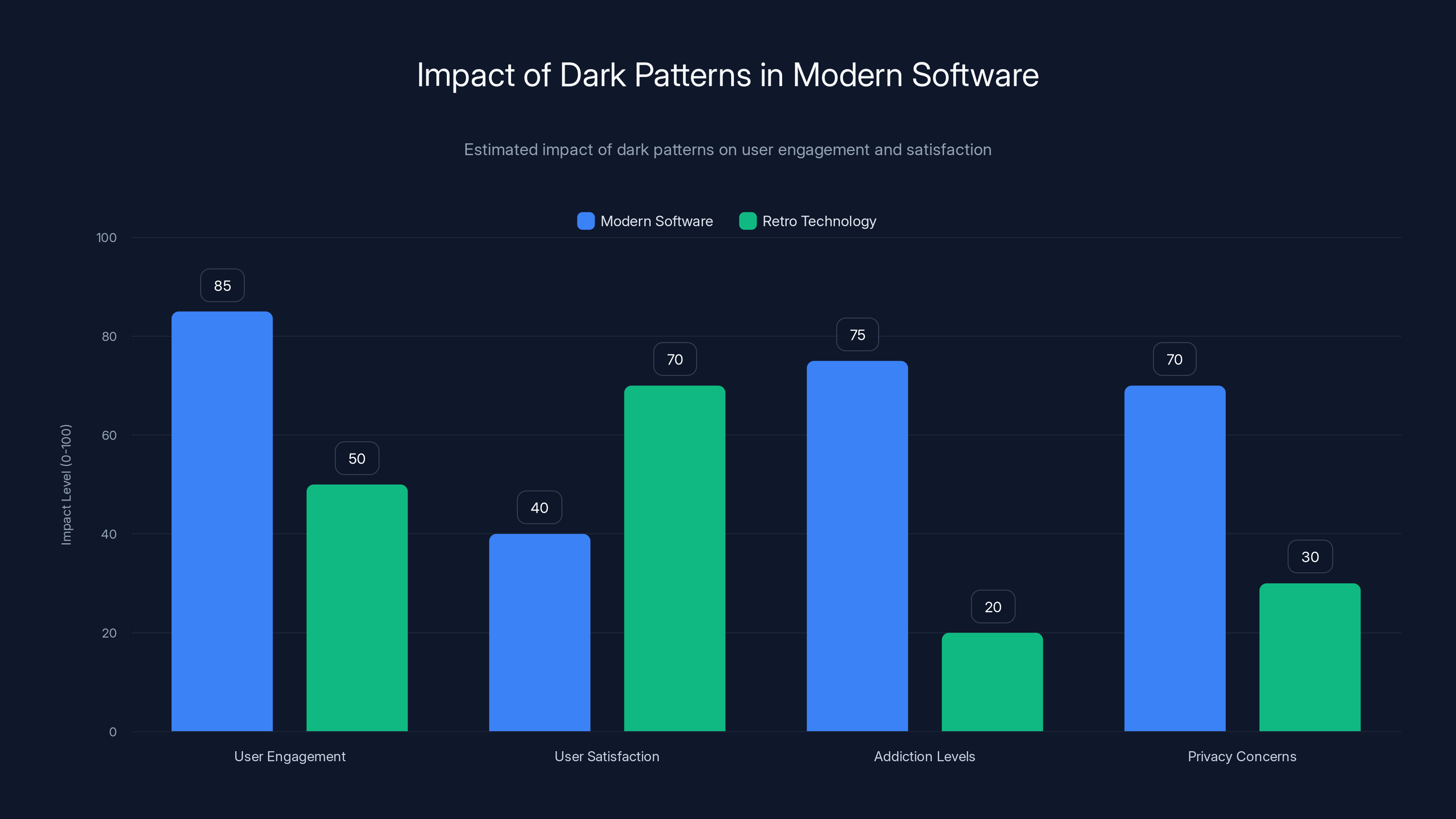

The Dark Pattern Problem in Modern Software

Underlying all of this is a truth that nobody wants to say out loud: modern consumer technology has become deliberately manipulative.

This isn't conspiracy thinking. It's documented fact. Companies hire teams of engineers and psychologists specifically to make their products harder to put down. Features are designed with addiction mechanics. Colors and sounds are chosen to trigger dopamine. Notification patterns are timed to maximize the chance you'll check back right when you're trying to focus on something else.

Apple calls these features "attention features." But that's marketing language. What they actually are is dark patterns. Design choices that benefit the company by making the product worse for the user.

Luckey never explicitly said this during his CES talk, but it's the subtext of everything he and Ohanian were arguing. When you design something in the 1990s, you couldn't employ these tactics because the technology didn't exist. You couldn't send push notifications. You couldn't track user behavior in detail. You couldn't A/B test different dopamine-triggering mechanisms.

So products from that era were necessarily more honest. They did what they were designed to do, without the psychological manipulation layer.

Retro technology appeals to people partly because it's incapable of dark patterns. A Game Boy can't send you a notification. A Walkman can't recommend songs based on a machine learning model trained on your listening history. A cassette tape doesn't track how long you listen or which songs you skip.

That's not because old technology was better designed. It's because old technology couldn't be weaponized against the user's attention in the same ways.

The retro tech movement, looked at this way, is actually a reaction to the attention economy. It's people actively choosing to use devices that can't exploit them, even when it means accepting less convenience or capability.

Estimated data shows a growing consumer interest in retro-inspired products, reflecting a shift towards valuing longevity and user respect over modern tech's disposability and engagement metrics.

The Manufacturing and Repairability Angle

There's also a practical side to this that gets overlooked. Modern devices are increasingly designed to be unrepairable. If your iPhone screen breaks, you can't easily replace it. If your laptop battery dies, you might need to replace the entire palm rest assembly. Products are engineered with the assumption that they'll be disposable.

Retro products generally didn't operate on this assumption. They were over-built. A Game Boy could survive being dropped off a roof. Modern gaming handhelds are much more fragile. Older devices used standard components. Modern devices use proprietary components that can only be obtained through official channels.

Part of the retro tech renaissance is people discovering that repairable devices are actually more valuable over time. A Game Boy from 1989 that still works is more impressive than a smartphone from 2020 that's already degraded to the point of being frustrating to use.

This intersects with environmental concerns. Landfills are full of electronics that stopped working because of planned obsolescence, not because they were fundamentally broken. People are starting to resent this waste. Buying a device that lasts 30 years is both more sustainable and often cheaper than buying a new device every three years.

Companies are starting to recognize this shift. The right-to-repair movement has gotten enough regulatory traction that manufacturers are being forced to make spare parts available. European regulations are now mandating that phones be serviceable for 5-7 years. This is changing how companies think about product design.

Incentives are shifting back toward durability and repairability, the principles that governed older products. So retro tech design philosophy is actually becoming practical again, not just nostalgic.

The Business Model Problem

Here's what Luckey and Ohanian didn't explicitly discuss but is implicit in everything they said: the business models of old tech companies were different from today's.

In the 1990s and 2000s, tech companies made money by selling you products. You bought a Game Boy, Nintendo made money. You bought a Walkman, Sony made money. The incentive was to make a product you'd love for years because happy customers bought the next product you released.

Today's tech companies make money differently. Apple makes money from the App Store. Google makes money from advertising. Meta makes money from selling your attention. The hardware is almost secondary. The device is just the platform for capturing your behavior and monetizing it.

This creates completely different incentives. The goal is no longer to make a product you love. The goal is to make a product that keeps you engaged, collects data, and makes you upgrade frequently. Longer-lasting devices are bad for business. Repairable devices are bad for business. Simple devices that do one thing well are bad for business.

When you understand this, suddenly the retro tech movement makes perfect sense. People aren't just nostalgic. They're opting out of a business model they've come to resent.

Luckey understands business models (Anduril is worth over $30 billion for a reason). So his emphasis on design principles and intentionality is actually pointing at business model change. Products designed with intentionality usually come from companies with different economic incentives.

Modern software often uses dark patterns to increase user engagement and addiction levels, but at the cost of user satisfaction and privacy. Estimated data.

What This Means for Tech Innovation

So we're at an inflection point. Consumer sentiment is shifting away from "newest and most advanced" toward "well-designed and intentional." This isn't small. This is a fundamental change in what people value.

It means innovation might look different going forward. Instead of thinner and faster, it might be more repairable and lasting. Instead of more features, it might be simpler and more focused. Instead of trying to capture every moment of your attention, it might be about respecting your time.

This doesn't mean the tech industry stops innovating. It means innovation becomes more thoughtful and directional. The goal isn't just "new," it's "better in ways that matter to users."

Companies that recognize this early have an advantage. They can build products for a market that's actively rejecting the current paradigm. Users who spend their money on vinyl, film cameras, mechanical keyboards, and retro gaming devices are showing you exactly what they value. They're willing to pay for it. That's market signal.

Luckey's already acting on this signal with Mod Retro and other projects. Smart companies will follow.

The Future of Retro Tech Design

It's worth noting that the future of tech probably isn't actually going to look like the 1990s. We're not going to go backwards. But we might synthesize old and new. Take the durability principles of retro devices, add modern engineering. Take the simplicity of vintage software, add the actual useful conveniences that technology can provide without the dark patterns.

That's where the real innovation is heading. Not backward, but toward a synthesis that takes the best of both eras.

You're already seeing this. Frameworks laptop is repairable and modular, which is retro philosophy, but it uses current technology. Nothing Phone is minimal in design but has modern specs. These products suggest a future that doesn't pit vintage against modern, but combines them.

That's probably what Luckey was really getting at. Not "we should use 1990s technology," but "we should use the design principles from when technology companies cared more about the product than about extracting value from user attention."

The Geopolitical and Supply Chain Layer

Remember when Luckey mentioned China and supply chains? That's more important than it sounds for predicting the future of design. If manufacturing becomes more localized or regional, the economics of standardization change. When everything was made in one place, standardization was efficient. When manufacturing is distributed, customization and modularity become more economical.

That means more diverse products. More options. More companies able to enter the market with novel designs. The smartphone monoculture we've lived in for the last 15 years was enabled by a specific supply chain arrangement. Change the supply chain, and you change what's possible to manufacture.

Luckey's hinting at this shift. Companies are already nearshoring manufacturing. Within ten years, this probably becomes the default for most products. That changes everything about product design.

It means devices designed for local repair become standard, not niche. It means modularity and replaceability become default features, not special options. It means aesthetics and personality become competitive advantages again, because you're not forced into the standardized mold that made sense for global manufacturing.

The retro tech movement might be the leading edge of this shift. Not people stuck in the past, but people recognizing what's coming and beginning to opt into it early.

Addressing the Criticism

The fair criticism here is that Luckey and Ohanian are incredibly wealthy and can afford to be philosophical about technology. For most people, the newest phone is a practical purchase, not a choice about philosophy. Older technology might be more intentional, but it's also less capable.

A Game Boy can't do what an iPad does. A cassette tape can't match the convenience of streaming. Vintage phones can't do what modern phones do. You're trading genuine capability for principles.

But that's exactly the point. The question isn't whether retro or modern is universally better. It's whether you get to choose what you're trading. For years, the choice was made for you. The only viable phone was the one designed with engagement optimization baked in. The only way to listen to music was through algorithmic curation. You didn't get to choose the trade.

Now, there's enough market demand that you do have choices. You can choose the convenience or the intentionality. Both exist. That's actually the win here. Not that old is better, but that you're not forced into new by the absence of alternatives.

The Real Takeaway

Luckey's argument about tech nostalgia isn't actually about nostalgia. It's about recognizing that we optimized the wrong things. We optimized for convenience and capability while ignoring intentionality and wellbeing. We built products that were worse to use because they were more profitable to make.

The retro tech movement represents people saying: stop. We'll take less convenience if it means products that respect our time and agency. We'll accept less capability if it means devices that last and can be repaired. We'll pay more if it means our data isn't harvested and our attention isn't weaponized.

That's not nostalgia. That's consumer awakening. And it's going to reshape the tech industry over the next decade in ways that most companies aren't ready for.

The companies that get ahead of this—that design for longevity instead of disposability, for simplicity instead of feature bloat, for user wellbeing instead of engagement metrics—those are the companies that will win the next era. Luckey's positioning Anduril to benefit from this shift. Others are too.

The future of tech might be in the past, as Luckey said, but not literally. It's in the principles. It's in remembering that a good product doesn't need to exploit the user. It's in recognizing that more features isn't always better. It's in understanding that people value things that work and last and can be owned, not consumed.

That's the real lesson from Luckey's CES talk. Not that we should go backward, but that we should have gone a different direction in the first place. And now that we know where the wrong path leads, we might actually choose differently.

FAQ

What does Palmer Luckey mean by saying old tech is "objectively better"?

Luckey argues that vintage technology embodied design principles that modern products have abandoned: intentionality, durability, and simplicity. He's not saying old tech was more capable, but that it was designed with different priorities. A Game Boy required deliberate choice to use, while modern devices are engineered to maximize engagement and extract user attention. The "objective" part refers to measurable factors like repairability, longevity, and the absence of exploitative design patterns, not subjective preference.

Why is Gen Z interested in retro technology they never experienced?

Younger generations recognize that vintage devices have qualities that modern products deliberately removed: repairability, privacy by design, lack of dark patterns, and straightforward functionality. They're not remembering fondly because they never owned these devices originally. They're discovering that products from 30 years ago solve actual problems that modern technology creates. A vinyl record doesn't require a subscription. A Game Boy can't send notifications. A mechanical keyboard doesn't track your keystrokes. These aren't features of age—they're features that current products deliberately engineered away in pursuit of profit.

What is intentionality in technology design and why does it matter?

Intentionality refers to the deliberate, thoughtful choices made by users when interacting with a device. With vintage tech like mix tapes or physical music collections, every selection mattered. With streaming services, algorithms decide for you. With a Game Boy, you chose what to play. With a smartphone, notifications interrupt you. Intentional design respects user agency and makes engagement a choice rather than the product's default behavior. Research shows that friction and deliberate choice actually increase satisfaction and memory formation, even though they reduce convenience.

How is the right-to-repair movement connected to the retro tech trend?

The right-to-repair movement stems from frustration with planned obsolescence in modern devices. Modern smartphones and laptops are engineered to be unrepairable, forcing replacement rather than maintenance. Retro devices were often over-engineered and used standard components that could be replaced. As environmental consciousness grows and people recognize that repairable devices last longer and cost less over time, design philosophy is shifting back toward modularity and repairability. This is both returning to older principles and using modern engineering to make it practical at scale.

Does the retro tech movement mean AI and modern innovations are bad?

No. Luckey explicitly stated he supports AI and recognizes its value for improving workflows. The criticism isn't about innovation itself, but about how innovation is being directed. Current AI applications are primarily used to optimize engagement and extract value from users' attention, rather than improve user wellbeing. The criticism is about business models that create misaligned incentives, not about the technology. AI deployed toward user benefit rather than corporate extraction could be genuinely valuable and wouldn't conflict with principles of good design.

What practical differences do retro devices have from modern ones?

Retro devices differ in several measurable ways: repairability (old devices use standard parts, modern ones use proprietary components), longevity (vintage products were designed to last, modern ones for replacement cycles), simplicity (old devices did one thing well, modern ones attempt many features), privacy (retro tech can't collect data, modern devices are designed to), and ergonomics (physical buttons provide better feedback than touchscreens, though touchscreens are cheaper to manufacture). These aren't subjective preferences but documented design tradeoffs that shifted when global supply chain economics changed.

Will the future of tech actually look like the past?

Not literally. But the design principles are shifting back toward durability, repairability, and user agency while maintaining modern capability and technology. The future probably combines old and new: modular and repairable (retro principle) with current engineering and performance (modern advantage). You can already see this in products like Framework laptops (repairable), Nothing Phone (minimal design with modern specs), and Clicks Communicator (physical keyboard with contemporary connectivity). It's a synthesis rather than a return.

Why is manufacturing and supply chain relevant to retro tech design?

When products were manufactured at massive scale in single locations (China), standardization was economically optimal. When manufacturing becomes regional or nearshored, the cost calculus changes. Modularity and customization become economical. Repairability becomes a feature rather than a liability. Local production supports local repair ecosystems. This shift in supply chain strategy might enable the return of product diversity and repairability not for nostalgic reasons, but for practical economic ones. Luckey was hinting at this geopolitical shift as an enabling force for design evolution.

How does the attention economy drive people toward retro tech?

Modern consumer devices are designed with engagement optimization baked in. Notifications, algorithmic recommendations, color choices, and interaction patterns are deliberately engineered to maximize the time you spend using the device. This is documented. Older devices couldn't employ these tactics because the technology didn't exist, making them incapable of the same psychological manipulation. People buying retro tech aren't just choosing simplicity—they're actively opting out of devices designed to exploit their attention. It's a rebellion against dark patterns, not a rejection of innovation.

What does the vinyl record comeback tell us about consumer preferences?

Vinyl sales exceed all other physical formats and rival streaming revenue, despite being technically inferior and inconvenient. This reveals that consumers value ritual, ownership, and intentional engagement over pure convenience. Buying and playing a record is an active choice, not passive consumption. You own the physical object permanently. This trend among Gen Z (not just older generations) shows that convenience isn't always what people optimize for—sometimes they prefer friction that creates genuine engagement and value.

Conclusion

What Palmer Luckey and Alexis Ohanian were really saying at CES isn't that we should dust off our 1990s Game Boys and pretend the internet never happened. What they were saying is much more important: we've been optimizing for the wrong things.

The tech industry has spent the last two decades maximizing growth metrics, engagement rates, and data extraction. We've built devices and platforms that are technologically impressive but fundamentally disrespectful of human time and agency. We've engineered addiction into the fabric of consumer technology. And we've done it while telling ourselves we were making things better.

But consumer behavior is quietly rejecting this. People are buying vinyl records and Game Boys and cassettes and mechanical keyboards and flip phones. Not because they can't use modern technology, but because they've learned that modern technology comes with costs that weren't baked into older products.

The companies that understand this shift early—that recognize that the next wave of innovation is about respect rather than capability, longevity rather than disposability, and user wellbeing rather than engagement metrics—those companies will win the next era.

Luckey's already building for this future with Mod Retro and his other ventures. Smaller companies are launching products like the Clicks Communicator and Framework laptop for the same reasons. There's money in this shift. More importantly, there's meaning. People want products that respect them. That actually works. That last. That can be repaired.

The future of tech isn't retro. But it might learn a lot from the past.

Key Takeaways

- Retro tech isn't about nostalgia—it's about recognizing that modern consumer devices sacrifice user wellbeing for engagement optimization and profit extraction

- Gen Z adoption of vinyl, Game Boys, and cassettes shows younger consumers actively rejecting algorithmic curation and dark patterns in favor of intentional design

- Vintage products prioritized durability and repairability by design, while modern devices deliberately engineer planned obsolescence and irreplaceability

- Shifting global supply chains and nearshoring may enable a return to modular, repairable design as a practical economic choice, not just nostalgic preference

- The future of tech may synthesize old and new: retro principles of intentionality and longevity combined with modern capability and performance

Related Articles

- Bose Open-Sources SoundTouch Speakers: How to Keep Them Alive [2025]

- Bose Open-Sources SoundTouch Speakers: A Better Way to Kill Products [2025]

- Wearable Health Devices & E-Waste Crisis by 2050 [2025]

- Realme GT8 Pro's Interchangeable Camera Design: The Future of Phones [2025]

- Fujifilm's Super 8 Video Camera: A Weird, Wonderful Instax [2025]

- Complete Guide to New Tech Laws Coming in 2026 [2025]

![Why Palmer Luckey Thinks Retro Tech is the Future [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-palmer-luckey-thinks-retro-tech-is-the-future-2025/image-1-1767897608800.jpg)