The Day Bluepoint Games Died: What Really Happened

On a Tuesday in early 2025, 70 employees at Bluepoint Games logged in to discover their studio was shutting down. Just five years after PlayStation acquired them for an undisclosed sum, the company that remade Shadow of the Colossus and Demon's Souls was done. No new announcement. No grand final project. Just closure.

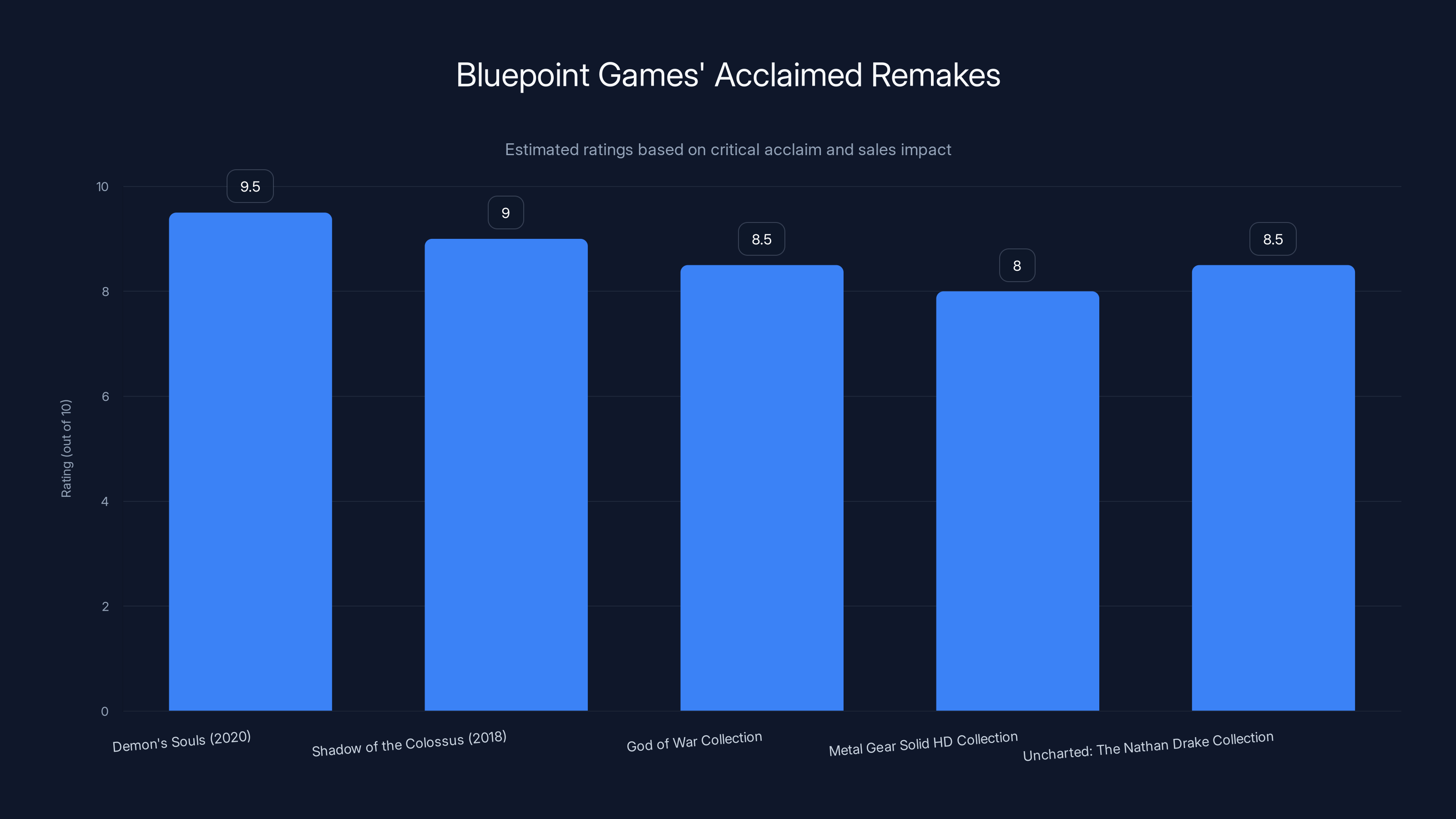

This wasn't some struggling indie team. Bluepoint Games had built its entire reputation on one thing: taking beloved classics and rebuilding them from the ground up. Their remakes weren't lazy cash-grabs. They were technical showcases that made you appreciate the originals while proving these old games still had life left in them. Demon's Souls on PS5 became a launch title that made people actually buy the console. Shadow of the Colossus in 2018 was good enough that a whole new generation discovered it.

So why did PlayStation kill it?

The short answer is money. Development costs are skyrocketing. The industry is broken in ways it wasn't a decade ago. And Sony, despite all its success, is making hard decisions about what it can actually afford to keep running. But there's so much more happening here than a simple budget cut.

This shutdown reveals something uncomfortable about the state of gaming in 2025. It's not just about one studio. It's about what happens when AAA development becomes unsustainable. It's about live-service games that nobody asked for. It's about studios acquired for their talent, then slowly starved of actual projects until the cost of keeping them open just doesn't make sense anymore.

Let's dig into what really went wrong at Bluepoint, and what it means for the rest of the industry.

The Acquisition That Seemed Perfect

When PlayStation bought Bluepoint in 2021, it looked like the ultimate power move. Sony was getting a studio with unmatched technical expertise. These weren't people who could just make a good game. They were masters at taking existing code, existing art, existing design, and elevating it to current-gen standards.

Their track record was sterling. The God of War Collection. The Metal Gear Solid HD Collection. The Uncharted: The Nathan Drake Collection. These were remasters and remakes done right. They respected the source material while pushing technology forward. More importantly, they consistently shipped on time and on budget.

So when PlayStation signed them, the thinking was clear: give this team a bigger budget, more resources, and more ambitious projects. Let them work on new ground-up remakes of iconic franchises. Let them prove they could do more than remaster.

And they did prove it. The 2018 Shadow of the Colossus remake was stunning. Critics loved it. Players loved it. Then came Demon's Souls as a PS5 launch title in 2020. That game sold over a million copies and helped convince people the new console was worth buying. For a remake, that's extraordinary success.

At that point, Bluepoint Games should have felt secure. They'd delivered exactly what Sony wanted. They'd shown they could handle major projects. The future should have been wide open. Instead, everything started to go sideways.

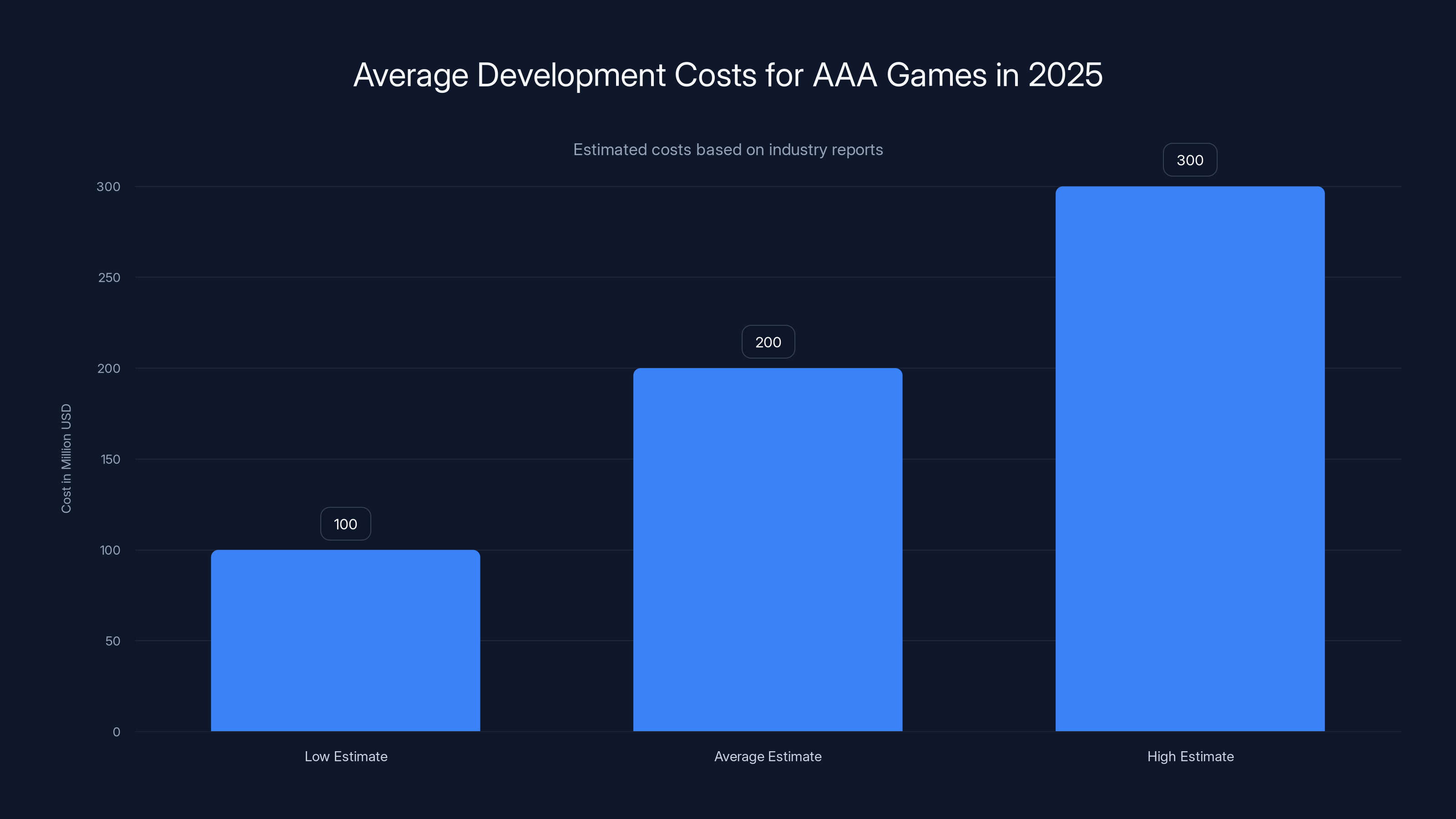

The average cost to develop a AAA game in 2025 ranges from

The God of War Live-Service Disaster

Here's where the story takes a dark turn. After successfully delivering both Shadow of the Colossus and Demon's Souls, PlayStation decided to give Bluepoint an even bigger assignment: make a live-service God of War game.

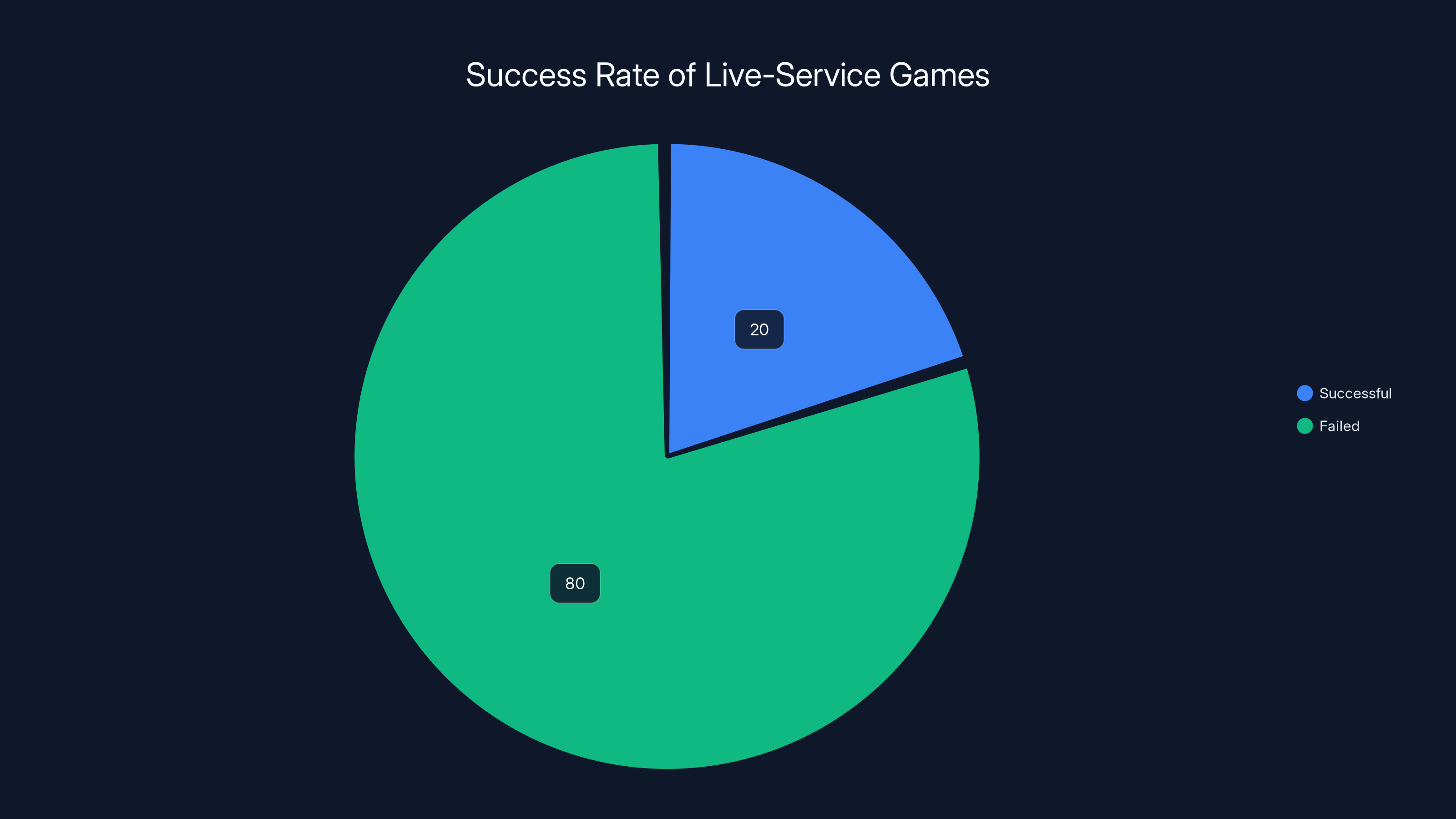

Live-service. Two words that have destroyed more studios than almost anything else in gaming. The entire industry watched live-service games explode in the 2010s. Fortnite, Valorant, Apex Legends. These games printed money and dominated player time. Every publisher wanted a piece. Even though most live-service games failed spectacularly, the ones that succeeded were so profitable that it felt like the smart business bet.

Except it wasn't smart. It was desperate.

PlayStation wanted Bluepoint to build something in that mold. A live-service God of War game that would generate ongoing revenue, keep players engaged, and compete with the biggest live-service titles in the world. Except Bluepoint had never made a live-service game. They'd never had to maintain a game post-launch, manage seasonal updates, balance multiplayer economies, or deal with the endless server costs that live-service games demand.

They were being asked to completely reinvent themselves as a studio. Not just to make a different type of game, but to fundamentally change how they worked, how they planned, how they managed resources. This wasn't a remaster anymore. This was uncharted territory.

For over two years, they apparently worked on this project. They poured resources into it. They probably hired new people with live-service experience. They probably spent months figuring out what this game would even be. And then, by January 2025, the entire project was canceled.

That cancellation is the moment everything fell apart. A studio that had just shipped two of PlayStation's most acclaimed games of the past five years was suddenly sitting with nothing. No finished game. No upcoming release. No clear path forward.

What Happened After the Cancellation

Once the God of War live-service project was killed, Bluepoint spent the rest of 2025 in pitch mode. According to reports, the studio was thrown into a difficult position: figure out what to work on next. Generate new ideas. Pitch them back to PlayStation leadership. Hope one gets greenlit.

This is where things get really rough for mid-tier studios. The blame isn't really on Bluepoint. It's on the entire system that created this situation. Once you've shipped a major remake or two, what do you do next? You can't keep remaking the same franchises. The industry moves fast. Players want new experiences. And yet Bluepoint's whole identity was built on remaking old games brilliantly.

So what's a studio like that supposed to pitch? An original remake of some lesser-known PlayStation title? A prequel to Shadow of the Colossus? Something completely new and original? All of these options have problems. Do it wrong and you're competing in spaces where there's already tons of competition. Do it right and you've probably tripled your budget expectations.

PlayStation looked at Bluepoint sitting there in pitch limbo, burning money, with no approved project, and made a calculation. The cost of keeping the studio open for another six months, another year, just hoping something would get approved, was more expensive than shutting them down. So they shut them down.

But here's the thing that makes this so frustrating: this wasn't inevitable. This was a choice. A series of choices, really. The choice to push a remake-focused studio into live-service. The choice to cancel that live-service project without having a backup plan. The choice to put them in pitch mode instead of assigning them a clear project immediately.

Bluepoint Games' remakes received high critical acclaim, with Demon's Souls (2020) leading due to its role as a PS5 launch title. Estimated data.

The Rising Development Cost Spiral

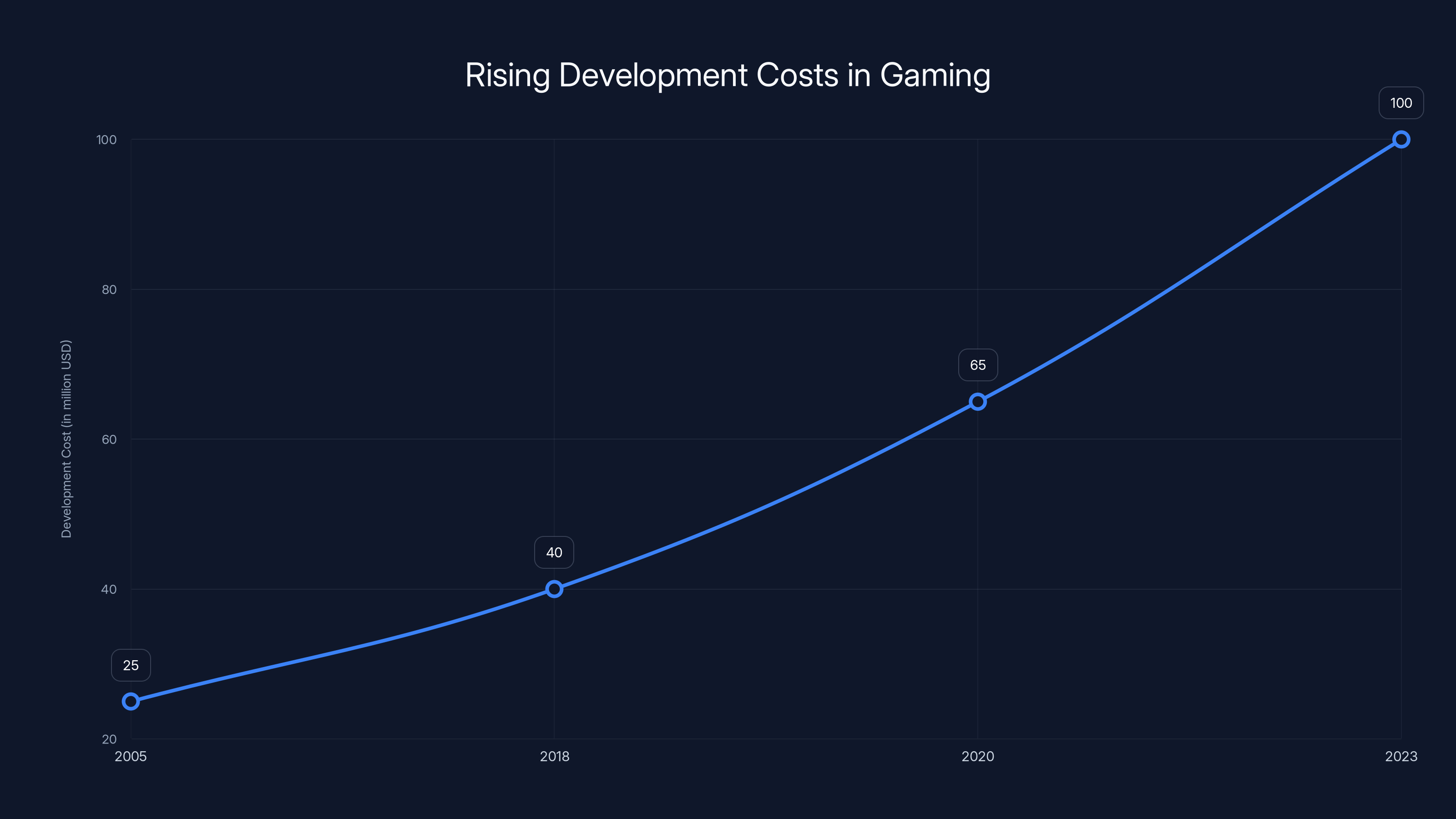

In Sony CEO Hermen Hulst's statement about the closure, he mentioned "rising development costs" as a key factor. This is the real issue underneath everything that happened to Bluepoint. It's not unique to them. It's an industry-wide problem that's reshaping gaming as we know it.

When Shadow of the Colossus shipped in 2005, the game had a development budget that, by today's standards, would seem quaint. Maybe $20-30 million? When Bluepoint remade it in 2018, the budget was probably higher, but still reasonable. The game was gorgeous, detailed, technically impressive. But it wasn't competing on scope with the biggest AAA games.

Then Demon's Souls remake came out in 2020. This is where costs really started to show. Next-gen technology meant higher polygon counts, better lighting, more detailed environments, more complex systems. The remake probably cost $50-80 million. Still a solid budget, but noticeably bigger.

Now imagine trying to launch an original game, or even an ambitious new remake. You're not just increasing budgets incrementally. You're hitting a brick wall. To make a game that looks good on current hardware, to compete visually with what people expect, you need massive teams. You need years of development. You need budget reserves for delays, for rework, for features that don't work out.

The math breaks down fast. A $100 million game needs to sell multiple millions of copies to break even. Most games don't. Only franchises with built-in audiences can reliably hit those numbers. Which means fewer studios are willing to green-light truly new, unproven concepts.

Bluepoint, stuck between what they were (the best remake studio in the industry) and what PlayStation wanted them to become (a live-service studio), ended up in a position where neither path made financial sense anymore.

The Broader Pattern: Studio Consolidation and Closures

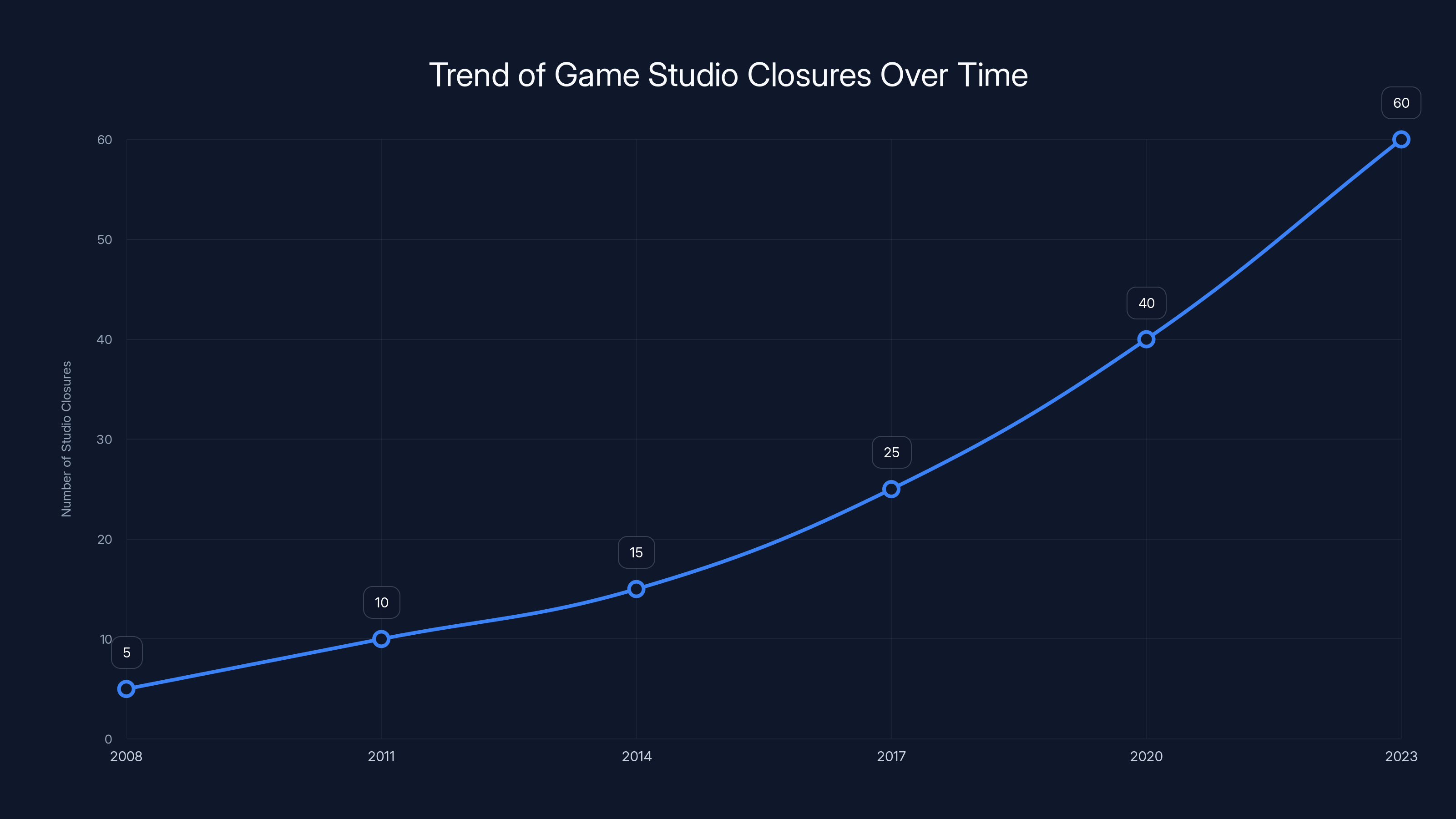

Bluepoint's shutdown is part of a much larger pattern in gaming. Over the past few years, dozens of studios have shut down. Telltale shut down, laid off hundreds, came back smaller. Visceral Games shut down. Telltale shut down again. Scavenger Studio shut down. And those are just a few. The actual number is much, much higher.

This isn't random. It's the result of how the industry organized itself over the past 15 years. Publishers bought up studios aggressively. They consolidated talent. They promised security and resources. And then, when market conditions changed, they had no choice but to lay people off or shut studios down because the cost structure didn't support keeping everyone employed.

PlayStation alone owns a massive portfolio of studios. They've got teams working on Spider-Man games, God of War games, Ghost of Tsushima, Horizon, The Last of Us. That's a lot of games. That's a lot of budgets. And when the industry is tough, when live-service bets don't work out, when new IP underperforms, someone has to get cut.

Bluepoint was relatively isolated. They didn't have a guaranteed franchise. They didn't have a live-service game generating revenue. They were a specialized team that did what they did incredibly well, but in a market where that specialization became less valuable over time.

The tragedy is that they probably could have thrived as an independent studio again. There's still a market for excellent remakes. But as part of a major publisher, keeping them around costs money every month. That's a hard budget pill to swallow.

Why The Live-Service Pivot Failed So Badly

Looking back, forcing Bluepoint into live-service development seems almost absurd. These were people who excelled at understanding classic game design, preserving what made those games work, and translating them to modern hardware. Live-service games operate on completely different principles.

Live-service is about engagement metrics, retention curves, monetization hooks, seasonal content calendars, balance updates, and server infrastructure. It's about designing the game to keep people playing for years, spending money regularly. It's about metrics and analytics and player behavior tracking.

Bluepoint's strength was the opposite. They understood game feel. They understood pacing. They understood the artistic intent behind a design decision from 15 years ago and why changing it would break something about the experience.

Asking them to make a live-service God of War is like asking a master watchmaker to design a smartphone factory. Sure, they're both products. Sure, both require technical skill. But the fundamental approaches are incompatible.

What probably happened is someone at PlayStation looked at the success of games like Fortnite and Valorant and thought, "We need that." And they looked at their available teams and thought, "Bluepoint is talented. Give them the resources." And they didn't account for the fact that live-service development is a completely different discipline that requires different experience, different intuition, and different organizational infrastructure.

Industry reports indicate that approximately 70-80% of live-service games failed to generate sufficient revenue, highlighting the high risk associated with this model.

The 70 Employees Left Behind

There's something that gets lost in talking about studio closures at a business level. There were real people working at Bluepoint. Seventy of them, according to reports. Programmers, artists, designers, producers, engineers, managers. People who went to work every day trying to make great games.

Some of them had been at Bluepoint for over a decade. They'd survived as an independent studio for years before getting acquired. They'd made some of the best remakes ever created. And then, through no fault of their own, through decisions made in corporate boardrooms, their studio was done.

PlayStation said they'd try to find positions for them at other studios in the Sony network. That's something. But it's not guaranteed. Not everyone will get an offer. Not everyone wants to move to a different studio, a different project, a different team. For people who'd built their careers at Bluepoint, who'd developed relationships, who understood the culture and the way that studio worked, being shuffled into a different team is jarring.

There's also the question of what happens to their expertise. Bluepoint had accumulated specialized knowledge about remake development. That knowledge walks out the door when the studio closes. Some of it might transfer to other teams. Some of it just disappears.

This is the human cost of the business decisions we've been discussing. Studio closures are always abstract when you're reading about them. But they represent real disruption for the people involved.

What Bluepoint's Closure Reveals About PlayStation's Strategy

When you look at the Bluepoint closure in context, it reveals some interesting things about how PlayStation is managing its studio portfolio. First, the company is clearly being aggressive about cost management. Second, it's willing to make hard cuts when projects don't work out. Third, it's not wedded to the idea that bigger is always better.

There's actually something defensible about this approach. PlayStation has limited resources. They can't keep every studio running on speculation. They need to make bets and kill ones that aren't working out. That's basic business.

But the question is whether the right bets are being made. Killing a live-service God of War project that nobody was asking for? That's reasonable. But putting Bluepoint in that position in the first place? That's where the real mistake was.

It also raises questions about how PlayStation is thinking about its future. The company spent 2024-2025 dealing with fallout from live-service bets that didn't work out. Concord was a live-service Overwatch competitor that shut down after two weeks. The live-service Star Wars game got canceled. Over and over, these bets failed.

Yet the strategy seems to persist. Kill individual projects, but keep trying to find the next live-service unicorn. It's the sunk cost fallacy playing out at the corporate level.

Meanwhile, you've got a studio that proved it could execute brilliantly within a specific domain, and that domain is being abandoned.

The State of Remake Development in 2025

Here's an interesting wrinkle to this story. Remakes are actually incredibly popular with players. The Shadow of the Colossus remake sold well. Demon's Souls is still being played on PS5. And elsewhere in the industry, remakes are thriving. Resident Evil's remake trilogy has been massively successful. The upcoming Final Fantasy 7 Rebirth is a remake in spirit, if not in name.

Remakes are in high demand. But they're also expensive to make well. You can't cut corners. If you're remaking a beloved classic, players will immediately notice if you've compromised on quality, on faithfulness to the source material, on feel.

So remakes exist in this weird economic space. They're popular, but they don't have a guaranteed audience like a brand new entry in an established franchise. They're expensive to make, but they might not sell as well as an original game in the same franchise. And they're risky because if the remake doesn't capture what made the original special, it fails spectacularly.

Bluepoint was one of the only studios that had genuinely mastered this category. They understood remake development deeply. They had built a process, a culture, a set of tools and expertise around doing this specific thing exceptionally well.

By closing Bluepoint, PlayStation has lost access to that specialized knowledge. If they want to make another remake down the road, they'll have to rebuild that expertise internally, hire external consultants, or partner with another studio. All of those options are less efficient than just keeping Bluepoint open.

But efficiency isn't just about money. It's also about whether the company can justify the cost. And if Bluepoint isn't working on anything approved, they become a sunk cost.

Estimated data shows a significant increase in development costs from

The Timing: Why Now, Why March 2025?

One detail worth examining is the specific timing. The announcement came in early 2025. The closure was slated for March 2025. Why then? Why not earlier? Why not later?

The likely answer is that Sony was waiting to see if any of Bluepoint's pitched ideas would get approved. They gave the studio a window. Pitched concepts to leadership. Waited for greenlight decisions. When those decisions didn't come through positively, they made the call to shut things down.

March is also a strategic choice. It's Q4 in Japan's fiscal year system, which Sony uses. Closing a studio before the fiscal year ends gets the financial impact into the right reporting period. It's not cynical, just accounting. But it does suggest this decision was made relatively recently and methodically executed.

It also suggests that the pitch process probably dragged on longer than anyone wanted. If Bluepoint had pitched ideas that got greenlit, the studio would still exist. The fact that the studio is being closed means whatever was pitched didn't meet the company's approval thresholds.

We don't know what those pitches were. Could have been ambitious original games. Could have been new remakes. Could have been live-service projects with different IP. Whatever they were, they apparently didn't clear the bar.

Lessons for Other Acquired Studios

If you're running a studio that's been acquired by a major publisher, the Bluepoint situation offers some hard lessons. First, don't let the acquisition make you complacent. You've proven you can execute once. You need to prove it again and again. Second, diversify your capabilities. Don't be the studio that can only do one thing, even if you do it brilliantly.

Third, and most important, always be generating ideas that excite corporate leadership. The moment you stop being actively useful to the acquiring company, you become a cost center. And cost centers get cut when times are tough.

Bluepoint made beautiful remakes. But remakes are a means to an end for most publishers. They're ways to generate revenue while developing new IP. They're not the core business. So when Bluepoint couldn't move beyond remakes into bigger, newer, more ambitious territory, the corporate calculus changed.

This creates a really toxic situation for specialized studios. You can be exceptional at your specialty, but if that specialty doesn't fit into the publisher's strategic vision, you're vulnerable. The solution would be for studios to push themselves beyond their core competency. But that's hard to do while also maintaining the excellence in what you're known for.

Bluepoint tried to do that with the live-service God of War project. It didn't work out. And there aren't many second chances in this industry.

What Happens to Their Games?

One immediate question: what happens to Demon's Souls? To Shadow of the Colossus? These are still being played on PlayStation systems. These are still valuable pieces of the company's library.

The answer is they'll just exist. They'll stay on the PlayStation Store. People will keep buying them. Updates and support will probably diminish, but the games themselves aren't going anywhere. PlayStation isn't going to pull them or anything like that.

But future maintenance, future ports to new systems, future updates? That becomes unclear. If a future PlayStation system comes out and someone wants to port these games, who does that? They'll probably have to build a team or find external developers. The internal expertise that made these games exist and could iterate on them is gone.

This is another hidden cost of studio closures. It's not just the immediate loss of the team's capacity to work on new projects. It's the loss of the ongoing knowledge and capability to maintain and update existing work.

The gaming industry has seen a significant increase in studio closures over the past 15 years, with an estimated peak in recent years due to market conditions and consolidation trends. Estimated data.

The Broader Industry Context: Why This Matters Now

Bluepoint's closure happens at a specific moment in gaming history. The industry has been going through a reckoning. Post-pandemic, money tightened. Consumers are buying fewer new games. Live-service bets have mostly failed. The "metaverse" gaming revolution never happened. And everyone's scrambling to figure out what works.

In that environment, companies are being hyper-rational about budgets. Studios without approved projects get cut. Experimental divisions get shut down. Resources get concentrated on proven franchises and clear revenue sources.

This is economically rational. But creatively, it's devastating. Because the path from "crazy experiment" to "proven franchise" requires someone to fund the experiments. If every company is cutting the experimental budget, where do new ideas come from?

Bluepoint wasn't even experimental, really. They were a specialized studio. But the principle is the same. They represented a specific capability and expertise that didn't fit neatly into the company's strategic portfolio anymore.

The result is an industry that's becoming more conservative, more focused on franchises, less willing to bet on specialized teams doing specialized things.

What Could Have Been Done Differently

Looking back at this situation, there were probably moments where different choices could have led to a different outcome. The most obvious: don't push Bluepoint into live-service development. If you want a live-service God of War game, partner with a studio that has live-service experience. Let Bluepoint stay focused on what they do best.

Second: have a backup project ready before canceling the primary project. Don't leave a studio in limbo wondering what to work on next. That's a recipe for failure. If the live-service God of War is on shaky ground, greenlight a new remake or original project immediately so the team has something to transition into.

Third: be more strategic about acquisitions. Acquiring Bluepoint made sense in 2021 because remakes were hot and the team was talented. But did PlayStation have a long-term vision for them? Or was it just, "We like this team, let's add them to the collection"? The former creates stability. The latter creates the situation Bluepoint ended up in.

Finally, and most radically: maybe some studios are better off staying independent. Bluepoint existed successfully for over two decades before PlayStation acquired them. They had a business model that worked. They had creative autonomy. What did acquisition really provide them beyond initial security that later evaporated? That's a question worth asking.

The Future of Remake Development

With Bluepoint gone, who's going to make world-class remakes going forward? The market is still there. Demand is still there. Nostalgia is still a powerful force in gaming. But the specialist studio that excelled at this specific craft is now closed.

Other studios could learn from Bluepoint's work and try to replicate it. But knowledge transfer isn't perfect. Some of the excellence in Bluepoint's remakes came from specific people, specific processes, specific ways of thinking about the problem. That doesn't transfer easily.

Or maybe remakes become something that AAA studios handle as a side project while working on their main franchises. That's a different approach and probably results in less-excellent remakes overall.

Or maybe the economics just don't work anymore and we get fewer high-quality remakes going forward. That would be a loss for players who love this genre.

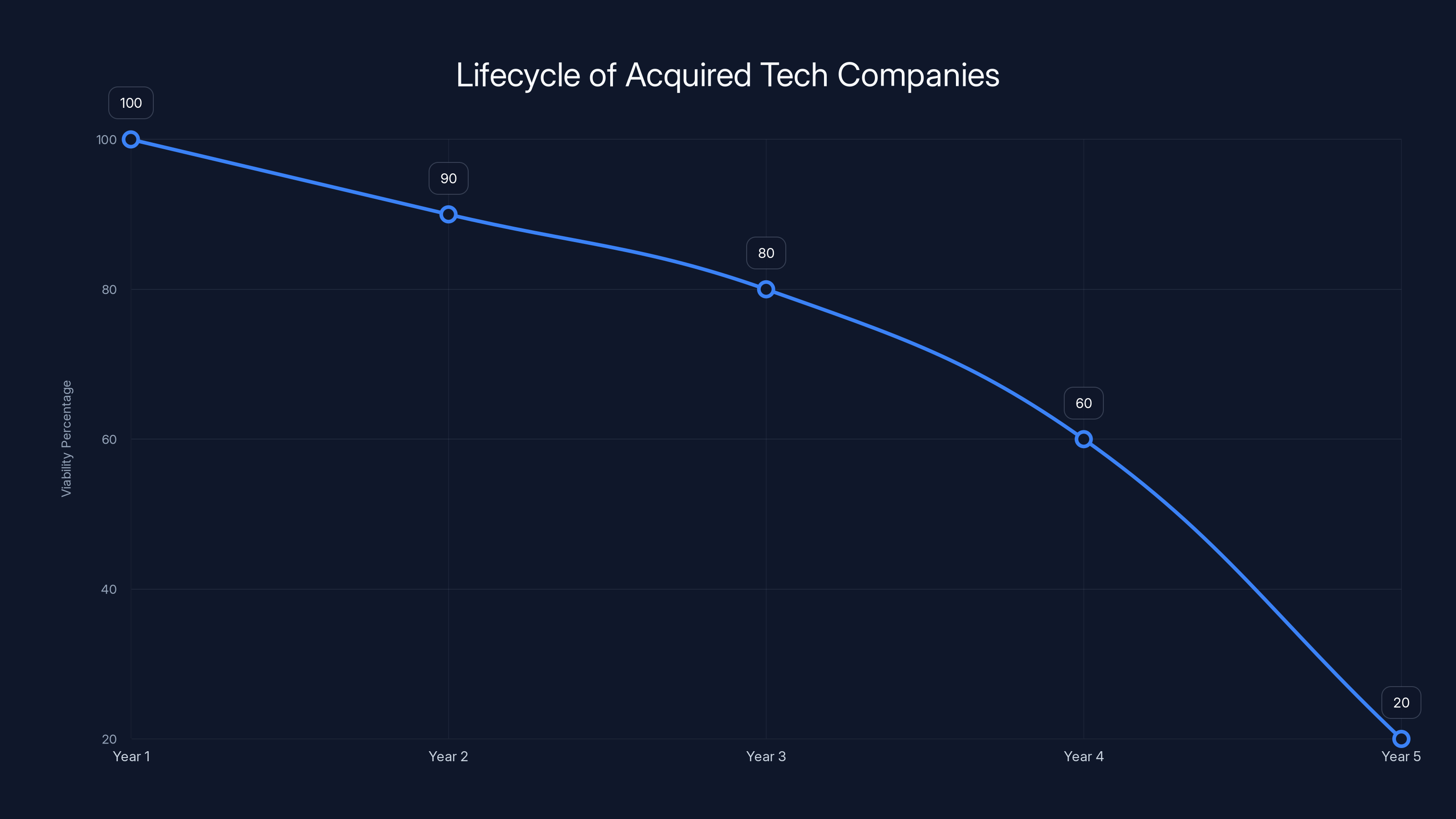

Estimated data shows a decline in company viability post-acquisition, highlighting the risk of strategic misalignment over time.

The Hermen Hulst Statement: Reading Between the Lines

The official communication from PlayStation CEO Hermen Hulst about the closure is worth analyzing closely. He mentions success: Ghost of Yōtei, Death Stranding 2, Helldivers 2, MLB The Show. He acknowledges challenges: rising costs, slowed growth, changing player behavior, economic headwinds.

Then he says the company needs to adapt and evolve. Which is true. All companies need to adapt. But the question is whether closing Bluepoint was the right form of adaptation.

Hulst also says the decision was "not made lightly." That's probably true. Closing a studio, laying off 70 people, ending a brand that had been around for decades, none of that is easy. But the fact that it happened anyway suggests the pressure was significant enough to overcome institutional inertia.

He also promises to try to find positions for affected employees in PlayStation's wider network. That's good in principle. In practice, it might not work out for everyone. Some employees might not want to move. Some might not be a good fit for other projects. Some might just not want to continue in this industry.

The statement reads like someone who made a hard business decision and is trying to explain it and soften the blow. It's professional. It's not trying to be cruel. But it's also clear: Bluepoint Games is done, and the company is moving forward.

What This Means for PlayStation's Next Generation

Looking ahead, the Bluepoint closure tells us something about what PlayStation is planning. They're being selective about studios. They're cutting fat. They're concentrating on franchises and proven leaders. Ghost of Tsushima worked. God of War works. Spider-Man works. Horizon works. The company is going to lean into those.

But what about reaching into the vault and remaking the really old stuff? What about projects that take risks and might fail? What about specialized studios that do one thing incredibly well but can't scale beyond that?

Those things are apparently no longer in the PlayStation budget. Which might be fine. Maybe the company is at a point in its lifecycle where it needs to be disciplined about resource allocation. But it does mean the industry is shifting toward consolidation and franchising and away from experimentation.

That's not necessarily bad. But it's worth noting.

The Ripple Effects: What Happens to Contract Work

One thing people don't always think about with studio closures is the ecosystem of contract workers and smaller companies that depend on them. Game development isn't just employed studios. There are contractors, freelancers, middleware companies, specialized shops that do specific technical work.

When Bluepoint shuts down, all those vendor relationships end. That's lost revenue for the smaller companies. It might not be dramatic for anyone in particular, but across the ecosystem, there's definitely an impact.

This is another way that consolidation can be more damaging than it initially appears. It's not just the studio and the employees. It's the whole network around them.

Could Bluepoint Have Been Spun Off?

One interesting alternative that apparently wasn't considered: could PlayStation have spun Bluepoint back out as an independent studio? Given them some funding to operate as a contractor to PlayStation while maintaining independence?

That probably would have been hard to execute. Bluepoint had been part of PlayStation Studios for several years. The infrastructure would have had to be untangled. Employees would have had to agree to move back to contractor status. Financing would have had to be arranged.

And from PlayStation's perspective, the question would be: why do this? If Bluepoint isn't directly valuable to the company anymore, why keep any relationship with them at all?

But it does raise the question of whether there are models other than acquisition or closure. Could PlayStation have created an arrangement where Bluepoint operated semi-independently while still having access to PlayStation resources? Could they have licensed the Bluepoint name and expertise while letting the team run itself?

These are speculative counterfactuals. But they're worth thinking about because they point to the limited options companies like PlayStation feel they have when an acquisition isn't working out the way they hoped.

The Message This Sends to Future Acquisitions

The Bluepoint closure sends a clear message to other studios considering acquisition by major publishers: there are no guarantees. You might succeed wildly. But you might also end up in a situation where the company has no clear role for you and decides to cut their losses.

This message might make talented studios more hesitant to accept acquisition offers. Which could actually be healthy. There's an argument that the industry would be better off with more independent studios, more diverse ownership, more variety in what kinds of games get made.

On the other hand, acquisition offers resources and security that independent studios often desperately need. So this doesn't solve the problem. It just makes the risk calculation more complicated.

What it does do is make it clear that being part of a big company isn't a safe harbor. You need to remain perpetually valuable. And that's a hard thing to maintain over decades.

The Question of Sustainability in AAA Game Development

Ultimately, the Bluepoint closure raises a fundamental question: is the current model of AAA game development sustainable? We have rising costs, slowed growth, hit-driven economics, and companies consolidating around proven franchises. That's not a recipe for long-term health.

Something has to change. Either costs need to come down, or revenue models need to diversify, or companies need to be willing to take on more risk in exchange for potential long-term payoffs. Right now, most companies are choosing the opposite path: protecting their investments, reducing risk, consolidating around what works.

That might work in the short term. But over a decade or two, it could result in an industry with less innovation, less variety, and less reason for players to be excited.

Bluepoint was a small contributor to solving this problem. They were a studio that did one thing exceptionally well. In a healthier industry, that kind of specialization would be valued and sustained. Instead, it became a liability.

What The Industry Needs to Learn

From the Bluepoint situation, there are a few lessons the broader industry should take away. First, live-service games are not a universal solution. They work for specific types of games and specific audiences. Trying to force every studio into that mold is a mistake.

Second, specialized expertise is valuable. A studio that can remake classic games better than anyone else is providing genuine value. That shouldn't be discounted just because it doesn't fit the current strategic trend.

Third, acquired studios need clear direction and support. If you acquire a team, you're making a commitment to them. Leaving them in limbo, forcing them to pitch ideas repeatedly, hoping something sticks, is not a recipe for success. Either commit resources to a specific project or accept that the acquisition might not work out.

Fourth, cost management needs to balance short-term budgeting with long-term strategy. Killing Bluepoint saves money now. But it also destroys a capability that might be valuable later. The optimal approach is rarely the most immediately cost-effective approach.

Finally, remember that these are real people's careers and lives being disrupted. The business decision to close a studio is legitimate. But the human impact is significant and shouldn't be treated as a side effect of budget optimization.

FAQ

What was Bluepoint Games known for?

Bluepoint was most famous for creating exceptional remakes and remasters of classic games. Their most acclaimed work included the 2020 Demon's Souls remake for PS5, which became a launch title that helped drive console sales, and the 2018 Shadow of the Colossus remake. Before PlayStation acquired them, they'd also created the God of War Collection, the Metal Gear Solid HD Collection, and the Uncharted: The Nathan Drake Collection. These weren't simple ports—they were complete reconstructions that updated the original games for modern hardware while preserving what made them special.

Why did PlayStation acquire Bluepoint Games in 2021?

PlayStation acquired Bluepoint in 2021 because the studio had proven expertise in remake development. After the critical success of their Shadow of the Colossus remake and the strong sales of the Demon's Souls remake, PlayStation wanted to bring this specialized capability in-house. The acquisition gave Bluepoint access to bigger budgets and PlayStation-owned franchises while giving PlayStation direct access to a team that had mastered a specific technical and creative discipline. The deal seemed like a natural fit at the time, as both parties benefited from each other's strengths.

What was the God of War live-service project that Bluepoint was working on?

After shipping Demon's Souls, Bluepoint was assigned to develop a live-service God of War game, which would have been a significant departure from their previous work. Instead of creating a single-player remake or remaster, they were tasked with building a game designed to generate ongoing revenue through continuous updates, seasonal content, cosmetics, and in-game purchases. The project ran for over two years before being canceled in January 2025, reportedly because the concept and execution didn't align with what PlayStation wanted or because the financial projections didn't justify the investment and ongoing operational costs.

How many employees were affected by the Bluepoint Games shutdown?

Approximately 70 employees were affected by the closure of Bluepoint Games. When PlayStation announced the shutdown in early 2025, with the studio officially closing in March 2025, it meant 70 people lost their jobs. PlayStation stated they would attempt to find positions for affected employees within other PlayStation Studios globally, though not all employees necessarily took those opportunities. The closure represented a significant loss of specialized expertise and institutional knowledge accumulated over Bluepoint's nearly three-decade history as an independent studio.

What does the closure of Bluepoint mean for future PlayStation remakes?

The closure of Bluepoint means PlayStation no longer has an in-house specialist studio for remake development. If the company wants to create more remakes in the future, they'll need to either develop that expertise within another studio, hire external consultants, or partner with outside developers. This could result in fewer remakes being developed, remakes of lower quality than what Bluepoint produced, or longer development timelines while internal teams rebuild the specialized knowledge that Bluepoint had accumulated over decades. The loss of this capability is particularly significant because Bluepoint had developed unique processes and deep understanding of how to approach remake development.

Will PlayStation continue supporting Demon's Souls and Shadow of the Colossus?

Yes, these games will continue to exist and be playable on PlayStation systems. They'll remain available for purchase on the PlayStation Store and won't be removed from player libraries. However, ongoing support, maintenance updates, bug fixes, and potential ports to future PlayStation hardware might be handled differently now that Bluepoint doesn't exist. Major content updates are unlikely, but the games themselves are stable and complete, so they should continue to be playable for the foreseeable future. If ports to future platforms become necessary, PlayStation will need to assign that work to another team.

Why did live-service development fail for Bluepoint?

Live-service development represents a fundamentally different discipline than remake development. Bluepoint had built its identity and expertise around understanding classic game design, preserving the feel and intent of original games, and translating them to modern hardware. Live-service games require expertise in engagement metrics, retention design, seasonal content planning, player behavior analytics, monetization systems, and ongoing server management. Pushing a remake-focused studio into live-service development was essentially asking them to completely reinvent how they work as a team. The company apparently didn't have the existing knowledge or talent to successfully execute in this new space, and building that expertise from scratch while also delivering a AAA live-service game proved too ambitious.

What financial challenges drove the decision to close Bluepoint?

According to PlayStation CEO Hermen Hulst's statement, rising development costs, slowed industry growth, changing player behavior, and broader economic headwinds made it harder to sustain the business. Specifically for Bluepoint, the studio was in "pitch mode" after the live-service God of War project was canceled, meaning they were proposing new projects to leadership without having any approved work. The cost of keeping 70 employees on payroll without an assigned project, hoping that one of their pitches would be approved, was apparently too expensive to justify. When no pitches achieved greenlight status, the financial calculus led to closure rather than continued funding while waiting for approvals.

Could Bluepoint have been restructured instead of closed?

It's possible in theory, but apparently not practical in reality. Restructuring would have required reassigning the team to different projects, reducing headcount, or reorganizing their role within PlayStation Studios. The challenge is that Bluepoint's core identity was remake development, and with no remakes on the horizon and no other clear projects approved for them, there wasn't a natural fit for the team within PlayStation's broader studio portfolio. Spinning them off as an independent studio again would have required unwinding the acquisition and establishing new financial and operational arrangements. From PlayStation's perspective, closure appeared to be more straightforward than the alternatives.

How does the Bluepoint closure reflect broader industry trends?

The Bluepoint closure is part of a larger pattern of industry consolidation and cost management. Over recent years, dozens of studios have shut down or experienced significant layoffs as publishers tighten budgets and focus resources on proven franchises. The broader trend shows an industry becoming more conservative and risk-averse, where specialized capabilities are valued less than they once were, and where acquired studios without guaranteed profitable projects face significant vulnerability. This reflects economic pressures including rising development costs, slower industry growth, failed live-service experiments, and publishers seeking to maximize profits. The trend potentially results in less innovation and less diversity in the types of games being developed across the industry.

What does this mean for employees of acquired game studios?

The Bluepoint closure sends a cautionary message to employees of acquired studios: acquisition by a major publisher doesn't guarantee job security. Even if you've proven yourself with successful projects, circumstances can change quickly if the acquiring company's strategic direction shifts or if approved projects fail to materialize. Employees should maintain diverse skill sets, build portable expertise that's valuable beyond their current studio, and understand that being part of a large company's portfolio means you're subject to budget cycles and strategic pivots beyond your control. Networking and building industry relationships becomes even more important in this environment, as those connections can help facilitate job transitions when studios shut down.

The Final Word: Why This Matters Beyond Gaming

The shutdown of Bluepoint Games might seem like niche industry news, but it reveals something important about how modern technology companies work. They acquire talent and expertise, integrate it into their operations, and then make hard decisions about profitability that can erase entire teams and capabilities.

This pattern plays out across the tech industry. A company buys a promising startup, integrates it, and then shuts it down when it no longer fits the strategic vision. It happens in software, in hardware, in every corner of tech.

The human cost is always present, even if corporate statements try to soften it. The loss of accumulated expertise is real. The cultural damage of seeing a studio you built get shut down is significant.

Bluepoint Games existed as an independent company for more than two decades, thriving in a competitive market. Five years after acquisition, it was gone. That's not a cautionary tale about one studio's failure. It's a cautionary tale about how modern consolidation works and what it costs when optimization happens at the expense of everything else.

Key Takeaways

- Bluepoint Games, known for exceptional remakes of Shadow of the Colossus and Demon's Souls, was shut down by PlayStation in March 2025 after five years of ownership, affecting approximately 70 employees.

- The studio's failure stemmed from a failed live-service God of War project that was canceled in January 2025, leaving the team without approved work and forcing them into unproductive pitch cycles.

- Rising AAA development costs (estimated at $100-200 million+ per game), slowed industry growth, and changing player behavior made it economically unsustainable to maintain the studio without active projects generating revenue.

- The closure reveals broader industry trends toward consolidation, reduced risk-taking, and focus on proven franchises, potentially limiting innovation and specialized expertise in game development.

- Acquired studios without clear long-term strategic direction face significant vulnerability, suggesting that independent operation might be preferable to acquisition by major publishers that deprioritize specialized capabilities.

Related Articles

- Sony's Live Service Strategy: Horizon Hunters Gathering Changes Everything [2025]

- AI Voice Acting in Games: Why Studios Are Going Back to Humans [2025]

- Crimson Desert No Microtransactions: Why This Premium Model Matters [2025]

- God of War Sons of Sparta: Why Jaffe's Critique Matters [2025]

- PlayStation 6 Release Delayed, Switch 2 Pricing Hike: AI Memory Crisis [2025]

- Metal Gear Solid 4 Leaves PS3: Console Exclusivity Death [2025]

![Why PlayStation Shut Down Bluepoint Games in 2025 [Complete Analysis]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-playstation-shut-down-bluepoint-games-in-2025-complete-a/image-1-1771585594326.jpg)