Why The Trade Desk Stock Collapsed: The Ultimate SaaS Growth Lesson [2025]

There's a moment every founder dreams about. Your company hits escape velocity. Revenue scales predictably. The market rewards you with a premium valuation. Investors fight for allocation. Your stock price becomes a kind of permanent victory lap.

Then growth slows by 5 percentage points.

And the entire story gets repriced.

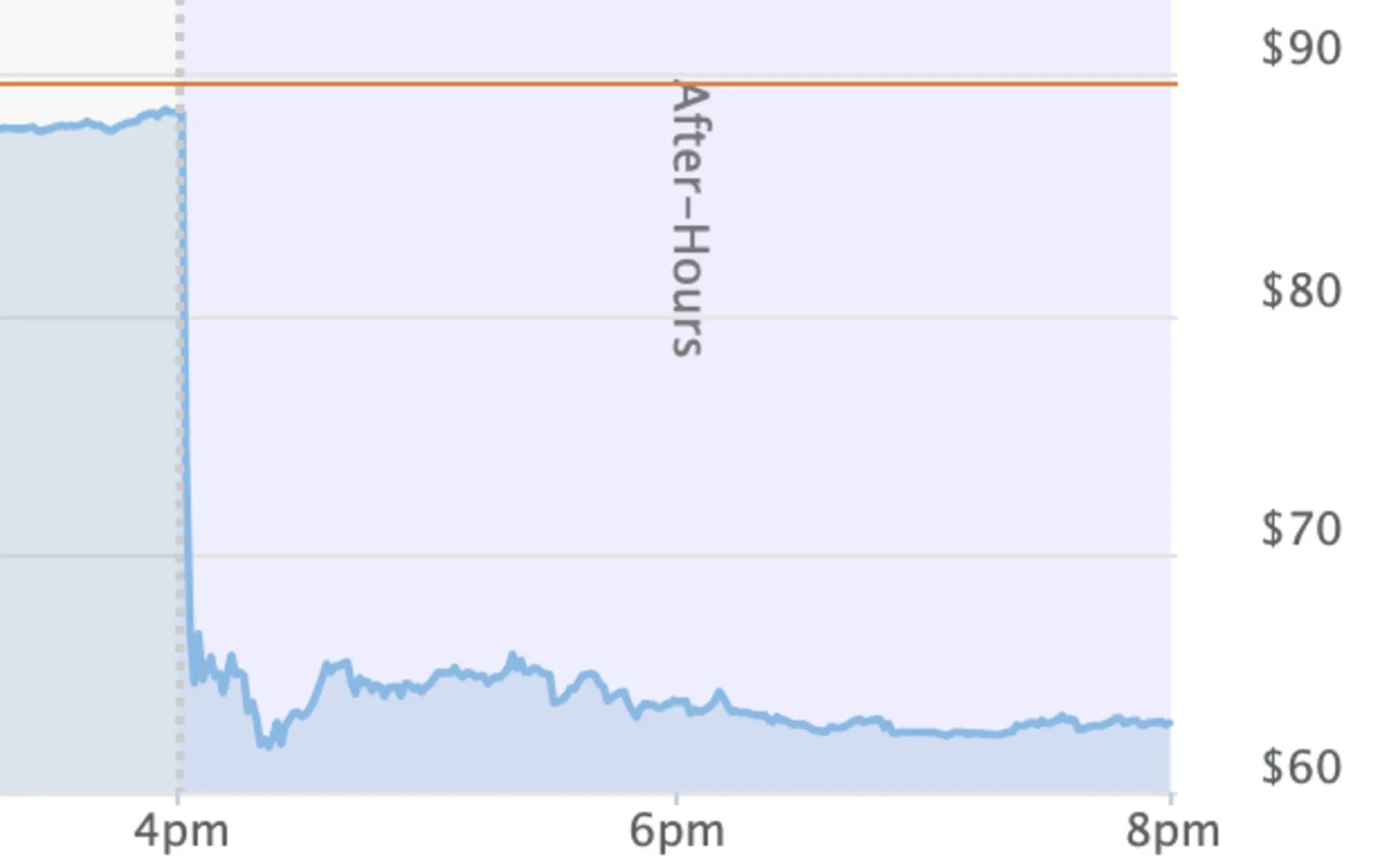

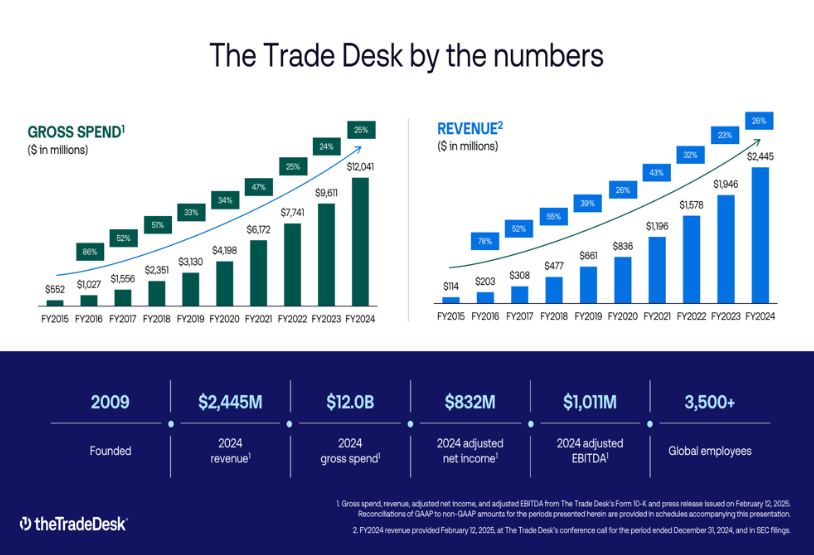

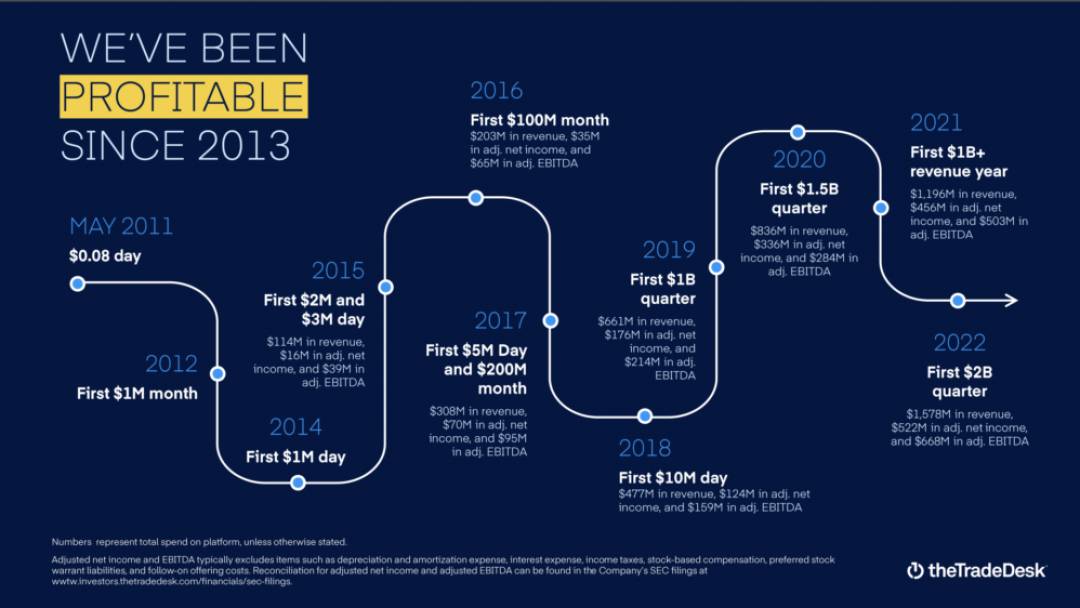

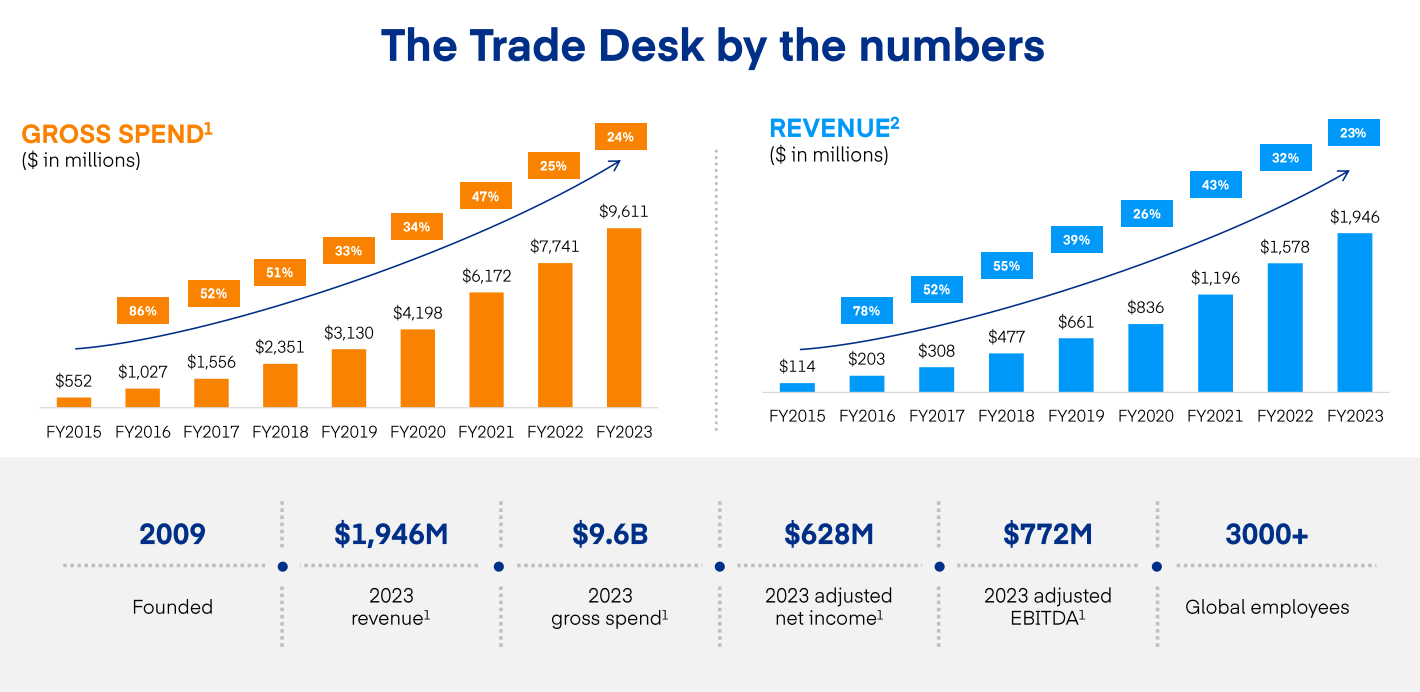

This is what happened to The Trade Desk, one of the most celebrated adtech companies in history. A founder-led, profitable software company that built the leading independent demand-side platform (DSP) in programmatic advertising. They grew at 26% annually while generating over $1 billion in adjusted EBITDA. By every operational metric, they were executing flawlessly.

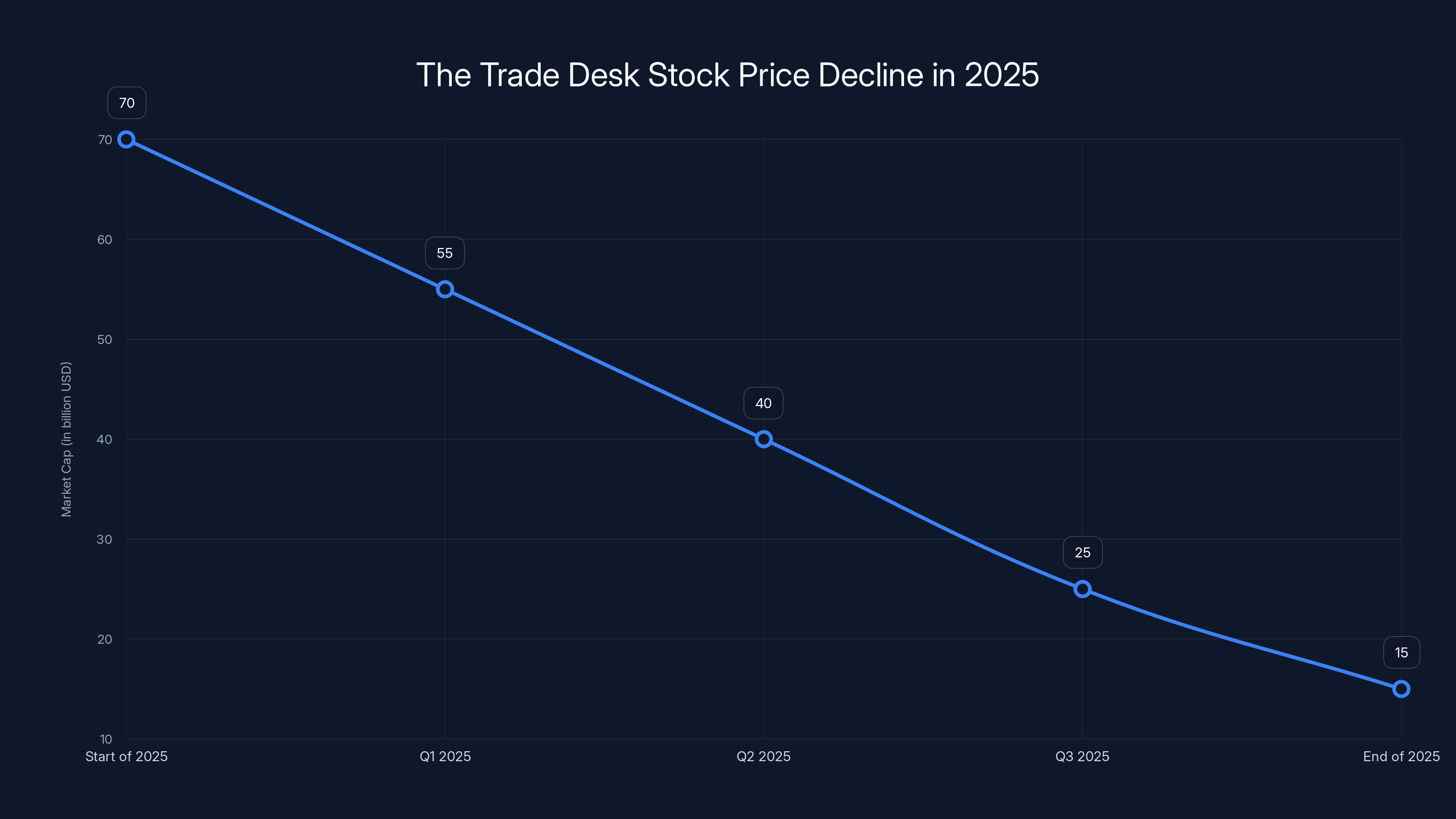

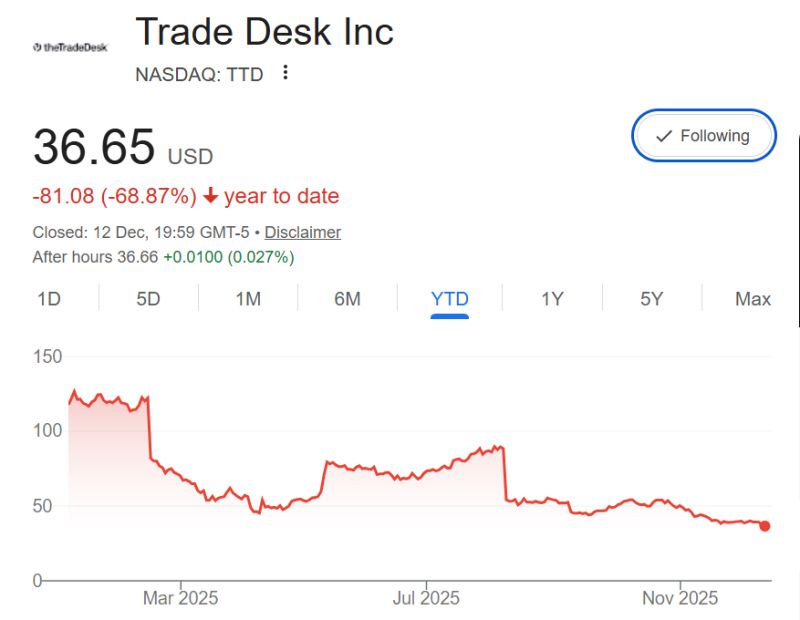

Then the stock fell 73% in 12 months.

Market cap cratered from

Here's what happened, and why it matters to every B2B founder scaling toward $100 million ARR and beyond.

TL; DR

- The Trade Desk fell 73% because growth decelerated from 25% to 18%, triggering a complete valuation reset for a stock priced at 90x+ earnings

- At premium multiples, profitability doesn't protect you: The market was paying for growth, not margins. Rule of 40 compliance became irrelevant when the narrative broke

- Competition from Amazon, Google, and Meta compressed Trade Desk's competitive moat as the giants closed the targeting and measurement gaps

- C-suite instability (two CFO departures in six months) amplified the crisis by creating uncertainty when confidence was already fragile

- The core lesson: If you're valued like a hyper-growth company, you need to deliver hyper-growth. When you don't, the fall is ruthless and immediate

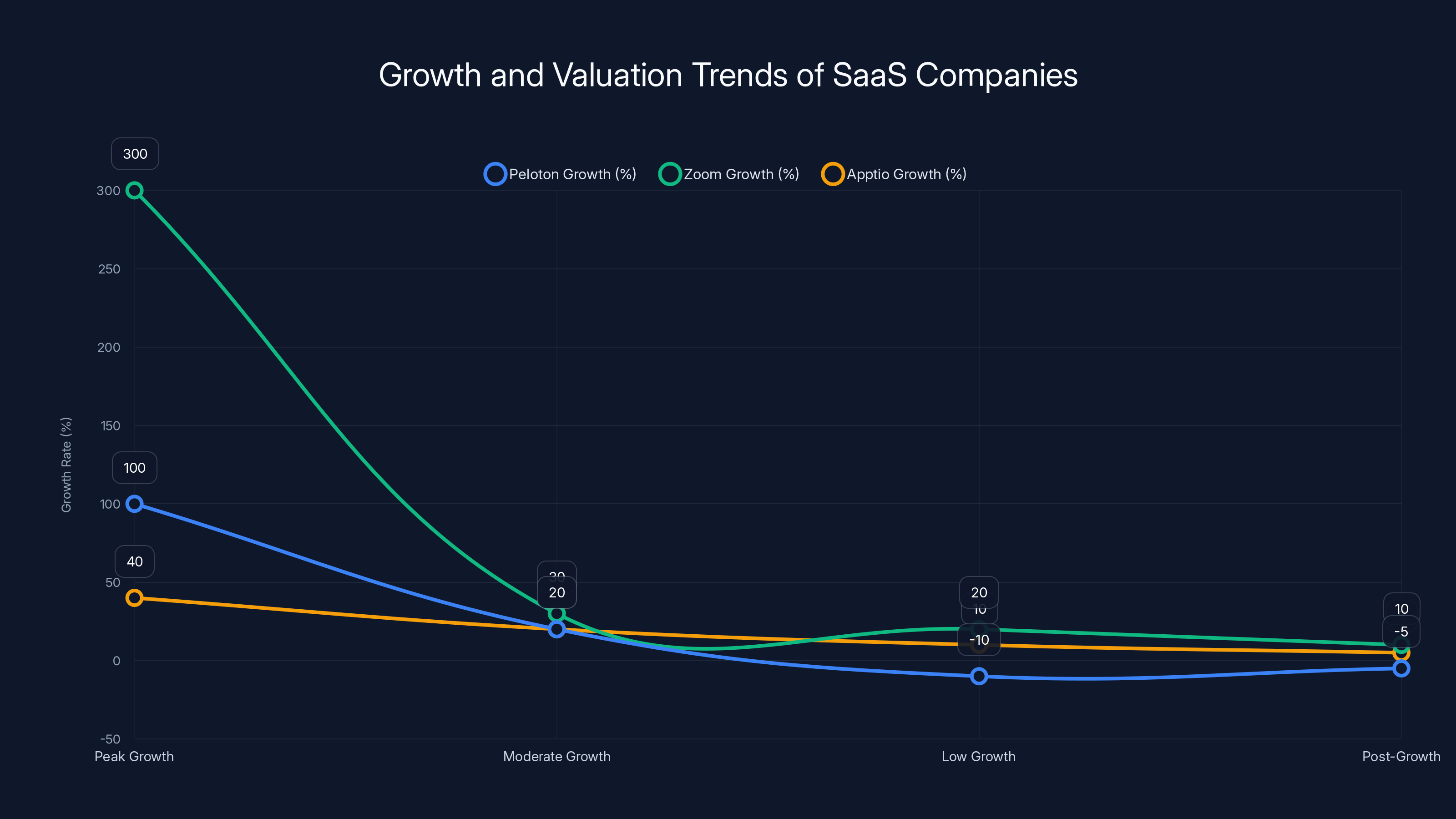

Estimated data shows how SaaS companies like Peloton, Zoom, and Apptio experienced significant growth during peak periods, followed by a sharp decline as market conditions changed.

The Setup: When Premium Multiples Meet Slowing Growth

Let's start with what The Trade Desk actually did right. For years, they were executing a textbook SaaS scaling playbook.

The company dominates independent programmatic advertising. Unlike Google, Amazon, or Meta, they don't own media inventory. They don't compete with their customers. They position themselves as neutral infrastructure—the Switzerland of digital advertising.

It's a brilliant position.

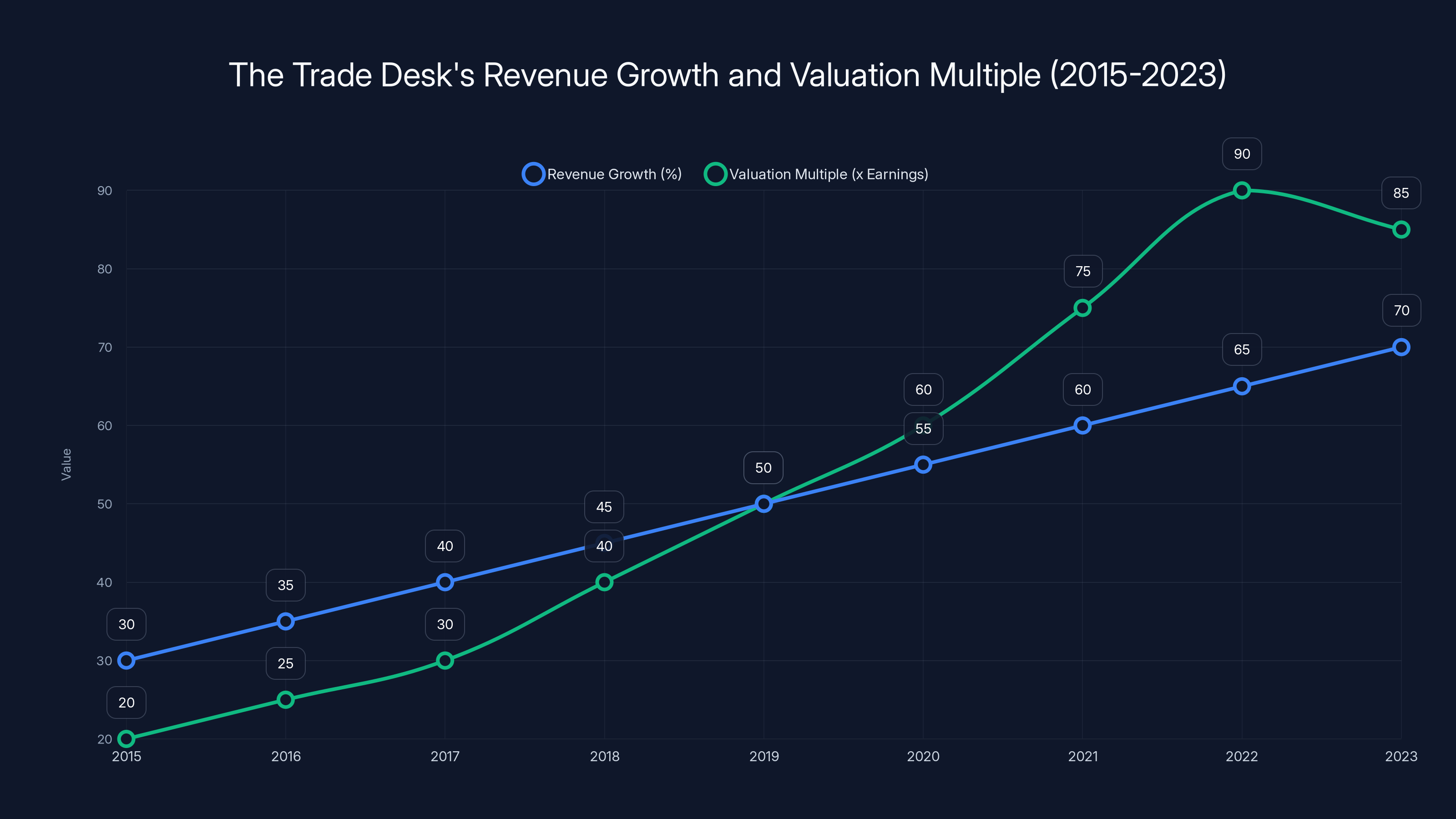

From 2015 through 2023, this positioning combined with explosive market tailwinds (connected TV adoption, mobile growth, programmatic standardization) to create an almost perfect growth story. The company scaled revenue while maintaining industry-leading margins. They hit their guidance. They grew their customer base. They expanded internationally. By all operational measures, this was a company executing at the highest level.

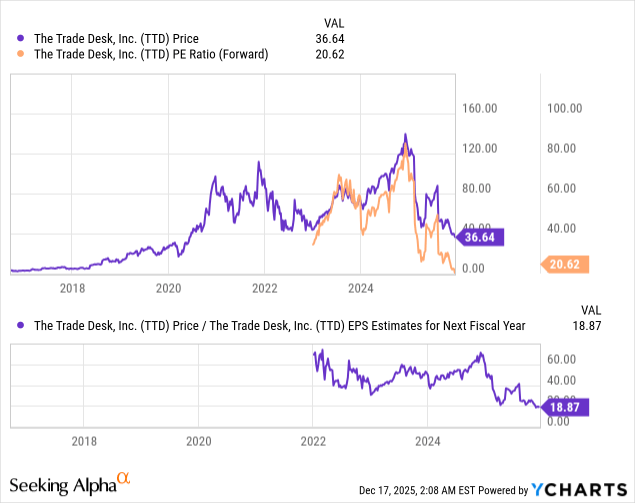

By 2021-2022, Wall Street had basically fallen in love. The stock traded at 90x+ earnings. Let that sink in. At that valuation, investors weren't paying for The Trade Desk as it exists today. They were paying for The Trade Desk as a perpetual growth machine—compounding revenue at 20%+ forever.

This is the trap that catches most founders by surprise.

When you're trading at 90x earnings instead of 15x earnings (like a typical mature software company), the market isn't paying for what you do today. It's paying for a narrative about perpetual acceleration. The multiple embeds aggressive growth expectations into the stock price.

Here's the math:

When the growth rate (the denominator's rightmost component) decreases, the entire equation compresses. It doesn't adjust linearly. The multiple doesn't just compress down to 60x or 70x. Investors immediately start asking: "What's the sustainable growth rate here? Is this a 15% compounder now? A 10% compounder?"

And that's when the repricing becomes brutal.

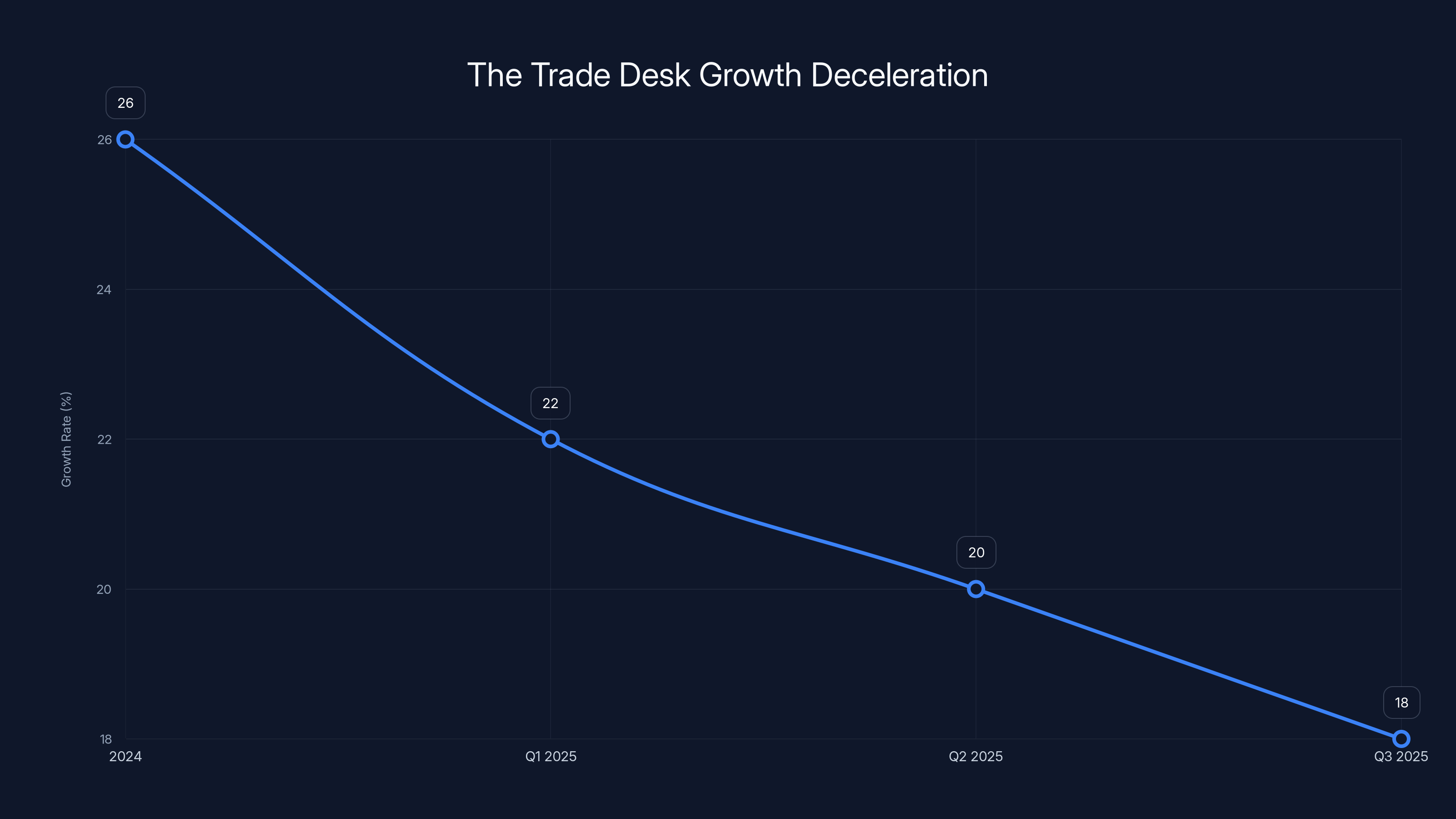

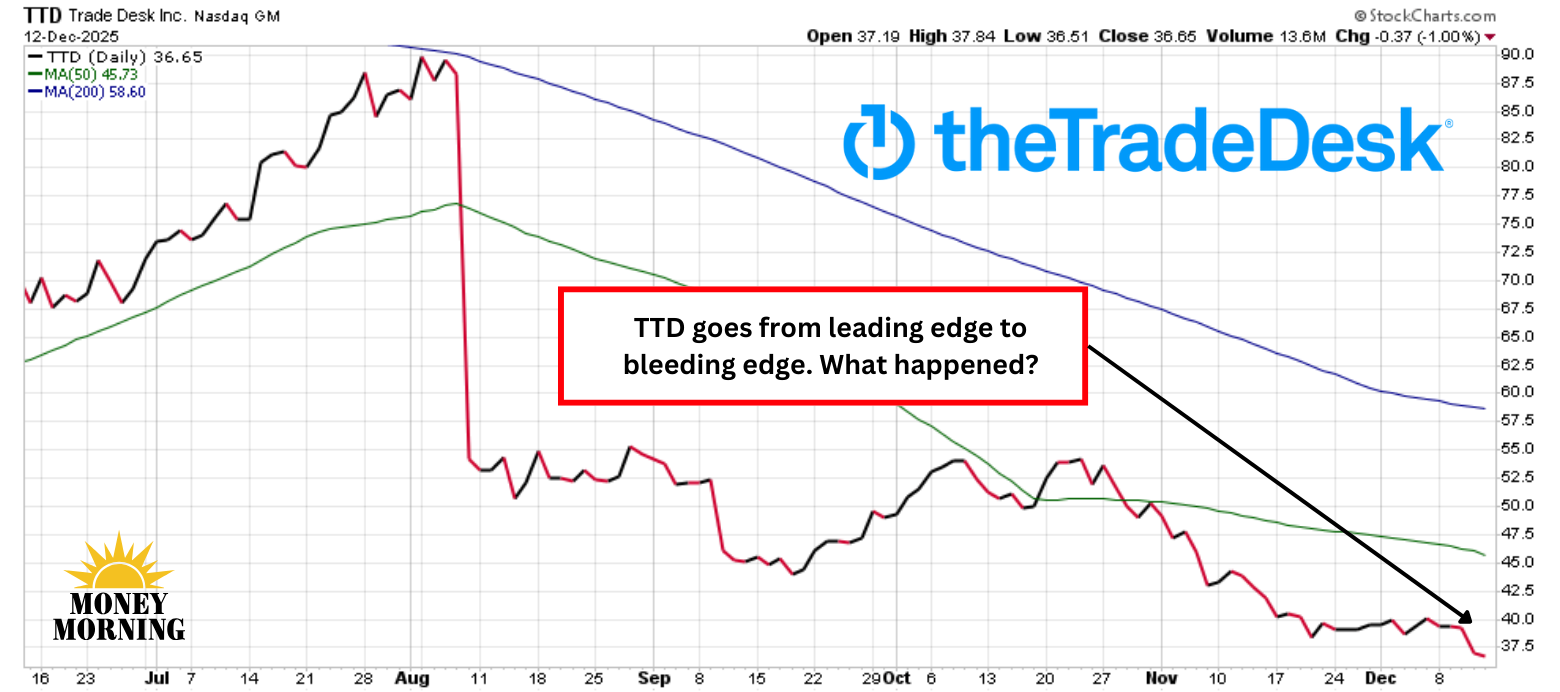

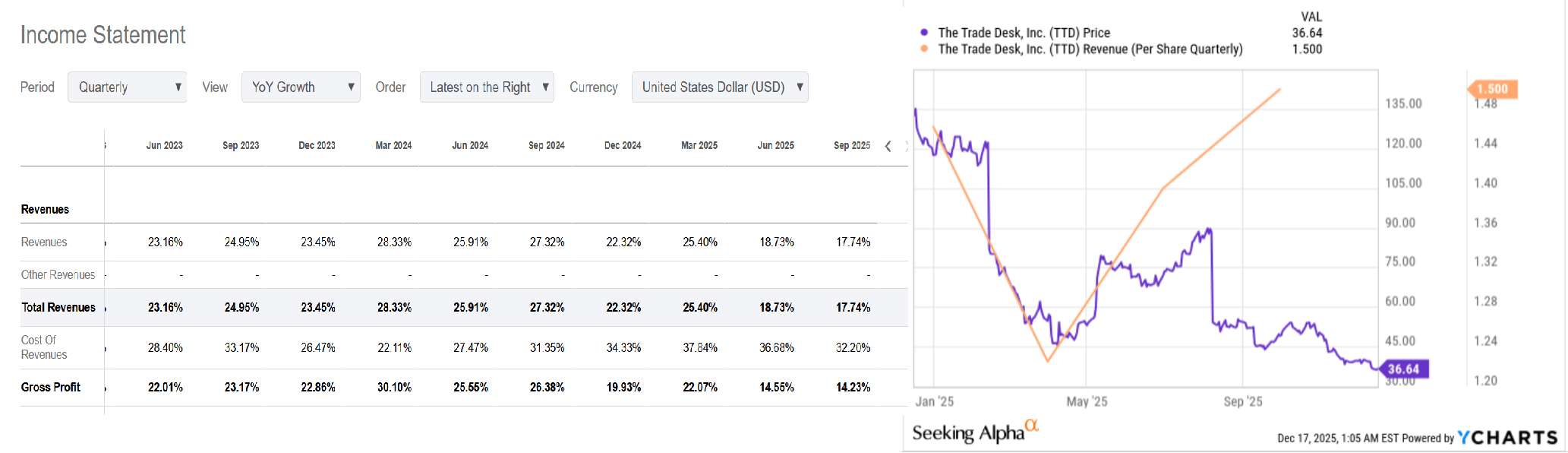

The Trade Desk's growth rate decelerated from 26% in 2024 to 18% by Q3 2025, contributing to a 73% stock price drop. Estimated data.

The Deceleration: 26% Growth Becomes 18% Growth

Trade Desk grew revenue 26% in 2024. Still solid by most standards. But that masked a troubling trend underneath.

By the first nine months of 2025, growth had slipped to ~20%. Q3 came in at 18%. On the surface, this doesn't sound catastrophic. Mature software companies would dream of 18% growth.

But context matters.

For Trade Desk, every analyst model, every investor pitch deck, every earnings call guidance had been predicated on a company that grows 20%+ indefinitely. Not 18%. Not 15%. 20%+.

When you're valued at 90x earnings, you're in what I call the "growth treadmill." You can't step off. The market has priced in perpetual acceleration. Miss by a few points, and the entire thesis breaks.

Here's what happened in the market's eyes:

2024: "Trade Desk still growing at 26%. We're pricing this at 90x because we believe it's a 25% grower forever."

Q3 2025: "Wait, 18% growth? Are we looking at a 15% terminal growth rate? A 10% compounder? Nobody knows."

Market repricing: Stock down 40%. Then 50%. Then 73% as investors rush for the exits, each one asking progressively more conservative questions about terminal growth rates.

The brutal truth: The Trade Desk didn't suddenly become a bad company. They became a slower-growing company. And in a market that priced them for perpetual hypergrowth, slowness is the worst possible sin.

Why Profitability Didn't Save Them

This is where founders often misunderstand what actually drives public company valuations.

Trade Desk is absurdly profitable. Over $1 billion in adjusted EBITDA in 2024. They generate real, tangible cash flow. They don't burn money. They hit their margin targets consistently. By every operational measure, they're a tier-one company.

And none of it mattered.

Why? Because at a $70 billion market cap, profitability is table stakes, not a differentiator. The market wasn't paying for EBITDA margins. EBITDA is assumed. What the market pays for, at those multiples, is growth trajectory.

This is the blind spot that catches so many scaled founders.

You optimize for Rule of 40 (revenue growth rate + free cash flow margin = 40+). You hit your EBITDA targets. You reduce churn. You improve CAC payback. You think: "We're executing flawlessly. We deserve premium multiples."

But if you're priced for 25% growth and you deliver 18%, you're going to get crushed. The profitability doesn't save you. The Rule of 40 doesn't save you. The cash flow doesn't save you. Because the market is buying a story about growth, not a fact about margins.

Trade Desk proved this empirically.

During the stock collapse, their profitability actually improved slightly. Margins stayed strong. Cash generation remained healthy. But the stock kept falling. Why? Because the growth narrative broke, and profitability is invisible to a growth-focused market.

This has massive implications for how you should think about scaling and profitability as you approach

Most founders assume profitability = safety. They assume better margins protect them from valuation volatility. Trade Desk is living proof that assumption is wrong. At premium valuations, profitability is table stakes. The market pays for growth narrative, not margin optimization.

This chart illustrates the disparity between actual growth rates and market expectations for SaaS companies. Trade Desk's growth fell short of market expectations, highlighting the limitations of the Rule of 40 in protecting premium multiples.

The Competition Problem: When Giants Close the Moat

Let's talk about the second issue that Trade Desk faced, because this one is more existential.

Trade Desk's entire pitch—the core reason they deserve premium pricing—is that they're independent. They're not Google (which owns YouTube). They're not Meta (which owns Instagram and Facebook). They're not Amazon (which is increasingly buying and selling ads). They're Switzerland. They sit in the middle of the programmatic ecosystem, helping buyers reach audiences across all these platforms.

The beauty of this positioning is it creates a moat. If you're a media buyer, you need a DSP that doesn't compete with you. Google's DSP will deprioritize your ads to show Google-owned inventory. Amazon's DSP will favor Amazon-owned properties. Meta's DSP will bias toward Meta properties.

Trade Desk doesn't have these conflicts. That's the entire value prop.

Then Amazon started building their own DSP.

They signed Netflix. They have better retail data than anyone on the planet. They're aggressively going after connected TV budgets, which happen to be Trade Desk's fastest-growing segment. And unlike Trade Desk, Amazon has the resources to invest $500 million to close targeting and measurement gaps if needed.

Suddenly, "we're independent" becomes a lot less compelling. Because Amazon isn't just building a DSP. They're building an Amazon-owned DSP with Amazon-owned inventory (advertising on their retail site, Prime Video, etc.). And if Amazon can match Trade Desk's targeting quality and offer exclusive access to retail data and premium inventory, the independence argument starts to fade.

Here's the trap: Positioning only matters if you can defend it.

"We're not them" works great as long as "them" isn't closing the gap. But when you're competing with companies with 100x your resources—Google, Meta, Amazon—and your entire moat is based on them not doing something, that moat gets very thin, very fast.

Trade Desk is now a small player in a market increasingly dominated by giants. They have better technology than a pure independent player would. But they're a minnow in a tank with sharks. And once the sharks decide to compete directly in your space, positioning matters less than product quality, inventory access, and data. Trade Desk has the first. The others have all three.

For founders scaling B2B companies, this is the core vulnerability: Your positioning is strongest when it's based on something structural, not just on what you don't do. "We're not Big Tech" works until Big Tech decides to compete with you directly. Then you need superior product, data, or platform effects to survive.

Trade Desk has good product. But they don't have unique data, and they don't have platform effects. So when Amazon decided to compete, Trade Desk's answer was basically: "We're better because we're independent." That turned out to be not enough.

The C-Suite Chaos Amplifier

Now here's where the story gets genuinely weird, and where you see how fragile confidence really is at public companies.

While Trade Desk was dealing with fundamental challenges (growth deceleration, competition from giants), they also experienced what you might charitably call "C-suite turbulence."

They hired a CFO in August 2024. Five months later, they fired him. No explanation given. The CFO remained on the board, which is unusual. Meanwhile, management conducted an external search for a replacement while their stock was in freefall.

Then the previous CFO had departed a few months prior.

Two CFO changes in six months.

Look, this might mean nothing. CFO transitions happen. But in a moment when the market is already questioning the company's growth narrative and competitive position, leadership instability becomes a confidence killer.

Analysts immediately started asking questions. What happened with the CFO? Was there a disagreement about guidance? About the budget? About accounting? Why wasn't a replacement named immediately? Why is the CEO serving as acting CFO while they search? (Spoiler: Because they wanted the person to understand the business before external candidates arrived.)

None of these questions had clear answers. And when investors are already scared, unclear answers create fear-driven selling.

Wells Fargo noted the announcement signaled "continued fundamental and narrative volatility." Truist cut their price target, citing "greater uncertainty." The analyst community started losing confidence that management had a clear plan to address the fundamental issues (growth deceleration, competitive pressures).

Here's the truth about public company dynamics that most founders don't fully appreciate until they live it:

At 90x earnings, confidence is everything. The valuation isn't rational. It's an expression of market belief about a future that doesn't exist yet. The moment confidence cracks—whether from growth deceleration, competitive threat, or C-suite weirdness—the entire valuation structure becomes suspect.

And then everyone heads for the exits at the same time.

Estimated data shows The Trade Desk's revenue growth and valuation multiple peaking in 2021-2022, reflecting high market expectations.

The Rule of 40 Trap: Why Profitability Doesn't Protect Premium Multiples

Let's dig deeper into this concept because it's so misunderstood and so important for founders scaling toward IPO.

The "Rule of 40" is a famous SaaS metric. It states that if you add your revenue growth rate and your free cash flow margin, the sum should be at least 40. So a 30% grower with 10% margins hits Rule of 40. A 25% grower with 15% margins hits Rule of 40. A 15% grower with 25% margins hits Rule of 40.

The theory: Rule of 40 means you're in a good place. You're growing fast and you're profitable. You're balancing growth and unit economics. You're not sacrificing long-term health for short-term revenue.

Trade Desk was a Rule of 40 company. They were hitting it consistently. Strong growth. Strong margins. The full package.

And it meant nothing the moment growth decelerated.

Why? Because Rule of 40 assumes a certain baseline of growth. It says: "If you grow 20% and generate 20% margins, you're doing great." But if your company is priced as a 25% grower, and you start doing 18% growth, the Rule of 40 is irrelevant. The market isn't paying for Rule of 40 compliance. It's paying for the growth narrative.

Here's how the math works:

Let's say Trade Desk had traded at 30x earnings (reasonable for a Rule of 40 company). A 73% stock decline would have been off the table. Investors would have been like, "Fine, you grew slower than expected, but you're still profitable, still generating cash, still hitting Rule of 40." The stock would drop, sure, but maybe 15-20%.

But Trade Desk traded at 90x earnings. That multiple assumes growth in the 22-25% range indefinitely. Rule of 40 didn't save them because the valuation was never based on Rule of 40. It was based on growth perpetuation.

This has a massive implication for how you should think about your business as you scale past

The Rule of 40 doesn't protect you at premium multiples. Profitability is the price of admission, not a differentiator.

If you want the premium valuation, you need to deliver premium growth. The moment you can't, the entire valuation collapses, regardless of how profitable you are.

Trade Desk proved this with their balance sheet. Over $1 billion in adjusted EBITDA. Expanding margins. Growing cash flow. All irrelevant to the 73% stock decline. The market repriced them based on growth trajectory, not margin quality.

What Happens When Growth Expectations Get Repriced

Let's zoom out and understand the mechanics of what happened to Trade Desk's valuation, because this is the core lesson every SaaS founder needs to internalize.

Public company valuations work backward from terminal value.

Investors don't just pay for what you do this year. They pay for a projection of all future cash flows, discounted back to present value. The calculation looks roughly like this:

Where

The Terminal Value is usually the biggest component of valuation. If you're projecting 20 years of cash flows, the Terminal Value might represent 60-70% of the total stock price.

Now here's where it gets interesting:

Terminal value assumes a perpetual growth rate. Usually 2-3% for mature tech companies (matching overall GDP growth). If investors believe a company will grow 20% for 10 years, then settle into 2.5% perpetual growth, they'll calculate the terminal value based on that assumption.

But the moment growth disappoints, investors have to recalculate that entire projection. They're now modeling a company that grows 18% instead of 20%. Maybe it peaks at 18% instead of 20%. Maybe it decelerates faster toward terminal growth.

Each of these tweaks changes the terminal value materially. And since terminal value is 60-70% of the stock price, changing the terminal value changes the entire stock price.

Trade Desk's situation:

Pre-deceleration model: 25% growth for 5 years, then gradual deceleration to 2.5% by year 10. Terminal value assumes stable ~20% retention of that value perpetually.

Post-deceleration model: 18% growth for 2-3 years, then faster deceleration to 8-10% by year 5, then gradual decline to 2.5% by year 10. Terminal value drops significantly.

The difference between those two models can easily be 70%+ in stock price. And that's what we saw.

The key insight: At premium multiples, small changes in growth rate create massive changes in valuation. This is why growth deceleration is so brutal for highly valued companies. You're not just losing a few percentage points of growth. You're losing all the discounted future value that the market assumed would compound forever.

A 73% stock drop significantly impacts operations, with talent recruitment and customer contracts facing the highest challenges. Estimated data.

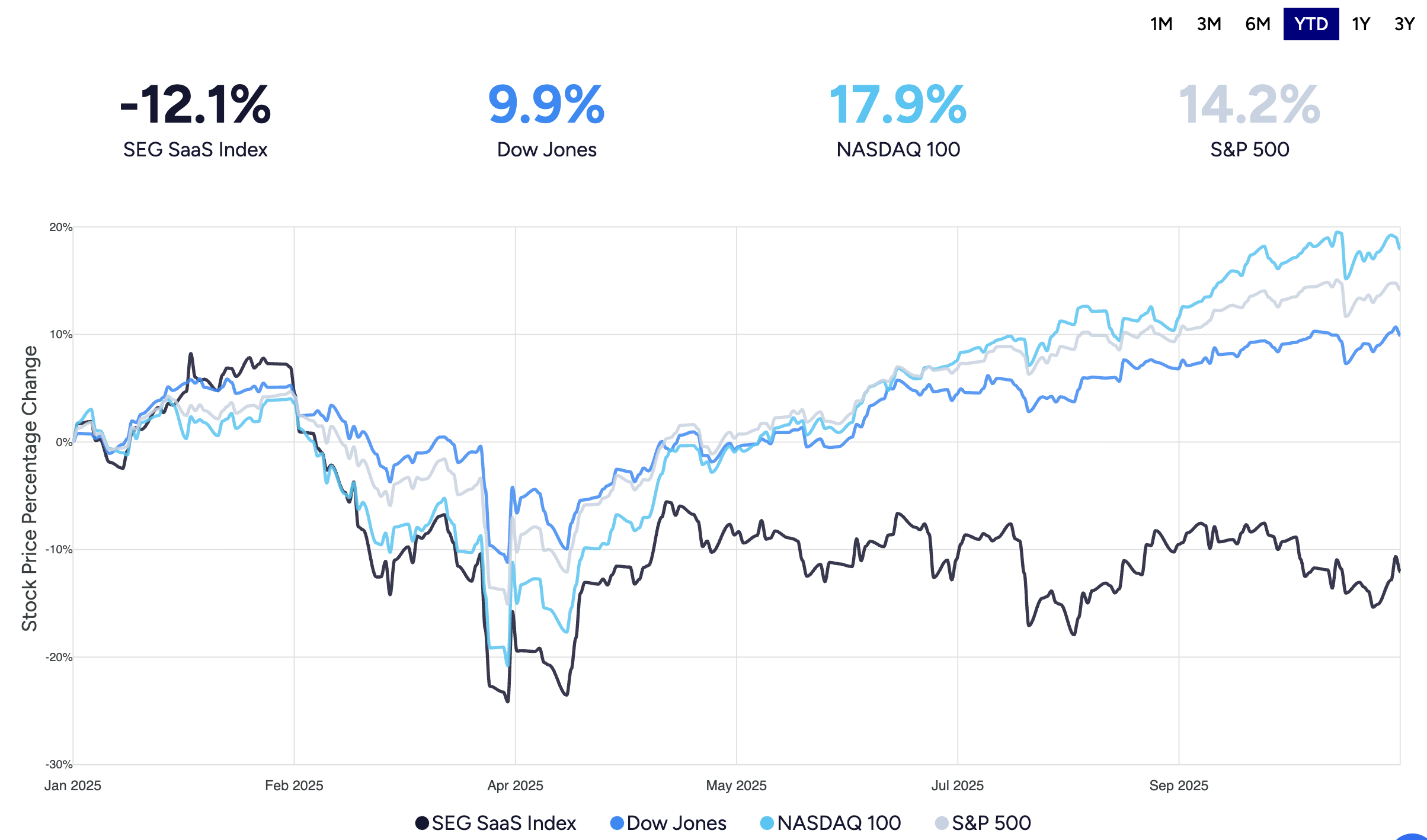

The Sector Compression: When Everyone Gets Repriced

There's another dynamic at play here that deserves attention: sector-wide valuation compression.

Trade Desk didn't collapse in a vacuum. The entire adtech and martech sector experienced what analysts called "contraction of peer multiples" in 2024-2025.

Companies like Criteo, Fluent, and other adtech players all faced repricing. The sector went from being the darling of growth investors to being seen as mature, slow-growth infrastructure.

But Trade Desk got hit hardest. Why? Because they had the furthest to fall.

Criteo traded at 15x earnings even at its peak. Not super premium, but respectable. When the sector compressed, Criteo dropped 20-30%. Painful, but survivable.

Trade Desk traded at 90x earnings. When the sector compressed and growth decelerated, Criteo's fall was 20-30%. Trade Desk's was 73%.

This is the mathematical reality of premium multiples: they amplify downside when the narrative breaks.

For founders, the lesson is simple: The higher your valuation multiple, the more you're exposed to sentiment shifts in your sector. If the entire adtech market decides "this sector doesn't grow 20% anymore," you're going to get hurt worse than a competitor trading at lower multiples.

The Operational Reality: Why Growth Slowed (The Harder Question)

So far, we've talked about valuation mechanics and market repricing. But there's a harder question underneath: Why did Trade Desk's growth actually slow?

It's not like the company suddenly stopped executing. They didn't have a product failure. They didn't lose major customers. There were fundamental reasons for the slowdown, and they're worth understanding because they apply to many scaling SaaS companies.

First, market saturation in core segments. Connected TV (CTV) was Trade Desk's fastest-growing segment for years. But you can only grow 40% YoY in a segment for so long. Eventually, you saturate the market. You've sold to all the available buyers. Growth naturally decelerates to the growth rate of the underlying market.

Trade Desk's mistake (arguably): They extrapolated CTV growth forward at 40%+ rates indefinitely. The market did too. But when CTV growth naturally decelerated to 20-25% (still fast, but not hypergrowth), the overall company growth decelerated from 26% to 18%.

Second, customer concentration risk. As Trade Desk grew, they became increasingly dependent on a smaller number of mega-customers. Netflix, for example, became a huge customer. Amazon's new DSP directly competes for the same Netflix inventory that Trade Desk had been selling to them.

When your top 5 customers represent 30-40% of revenue (not unusual at scale), you lose flexibility. Any one customer changing behavior impacts your growth rate materially.

Third, headwinds in emerging categories. While CTV matured, Trade Desk bet on several emerging categories (audio, video, retail media) to drive future growth. These markets didn't develop as fast as hoped. Retail media growth has been strong, but not fast enough to offset mature segment deceleration.

All of this is normal stuff that happens to scaling companies. Markets mature. Growth decelerates. You have to find new growth engines. It's the growth business equivalent of hitting the wall.

But the market didn't price Trade Desk for normal. It priced them for perpetual hypergrowth. So when normal growth deceleration happened, the repricing was brutal.

The Trade Desk experienced a dramatic stock price decline in 2025, with market cap falling from

The Ripple Effects: What Deceleration Means for Operations

Here's what most founders don't think about: When your stock drops 73%, the operational consequences are real and they make the problem worse.

Your ability to recruit talent gets harder. Stock options become worthless. Your best engineers start getting recruiter calls. (They were always getting recruiter calls, but now they answer them.)

Your ability to M&A gets harder. You can't use stock as currency anymore. You have to pay cash, which costs real value.

Your ability to set aggressive roadmaps gets harder. When your stock was at $70B market cap, you could pitch bold bets. "We're going to dominate retail media advertising." Now you have to focus on cash preservation.

Your customer contracts get harder. Every renewal becomes a negotiation. Customers that used to renew automatically start asking for discounts. "Your stock is down 73%. Why shouldn't we switch to Amazon's DSP?"

This is the vicious cycle of deceleration. It's not just that your growth slowed. It's that the slowdown triggers a series of operational consequences that make future growth harder.

Trade Desk is living through this right now. They're trying to execute against headwinds that didn't exist three months ago. Talent retention is harder. Recruiting is harder. Customer wins are harder. Everything becomes slightly more difficult just as you need it to be easier.

This is why growth deceleration is so dangerous for public companies. It's not a one-time repricing. It's a downward spiral that creates operational headwinds that make future growth harder.

The Investor Perspective: Why Wall Street Moved So Fast

There's been some criticism of the 73% stock decline as being "irrational" or "too harsh." But let's think about this from an investor's perspective.

You bought Trade Desk at 90x earnings because you believed the growth would continue. You were betting on management's ability to compound revenue at 20%+ forever.

Then growth dropped to 18%. Then you learned that Amazon is building a competing product. Then the CFO left. Then it got weird about the replacement.

At that point, what do you do?

You could try to stay. You could assume growth will re-accelerate. But the problem is, you don't know. And if you're an institutional investor managing billions of dollars, you're evaluated on quarterly and annual returns. Betting on a repriced company to re-accelerate is a multi-year bet. Your performance board wants you taking profits.

So you sell. Not because Trade Desk is worthless. But because the narrative broke and you need to redeploy that capital to somewhere with a clearer growth story.

When millions of investors have the same realization at the same time, you get fast, brutal selling.

Trade Desk's stock didn't fall 73% because the company is bad. It fell because:

- The growth narrative broke

- Investor confidence cracked

- Everyone headed for the exits

- The stock repriced to a much lower multiple

Each of these is rational from an individual investor's perspective. Collectively, they create a devastating outcome for shareholders.

For founders approaching IPO or dealing with premium valuations, the implication is clear: Your stock price is ultimately a reflection of growth expectations. Maintain growth. Communicate clearly about slowdowns. Don't let the market surprise you.

The Comparison to Other SaaS Implosions

Trade Desk's story isn't unique. It's part of a pattern that repeats regularly in SaaS.

Take Peloton. At its peak, Peloton traded at 15x+ revenues with a $50 billion market cap. They were growing 100%+ YoY. The market was convinced they'd created the future of fitness.

Then pandemic-driven demand saturated. Growth decelerated from 100% to 20% to negative. The stock collapsed from

Or look at Zoom. They grew 300%+ in 2020 (pandemic boost). Then growth normalized to 30%, then 20%. The stock fell from

Or Apptio, which went from 40% growth to 10% growth and saw its valuation cut in half.

The pattern is consistent: Premium valuations assume perpetual growth. When growth decelerates, valuations reprice violently. It doesn't matter how profitable you are. It doesn't matter if you're well-run. The repricing is mechanical.

Trade Desk is extreme (73% is worse than most), but it's part of the same pattern.

Building a Business That Survives Premium Valuations

Okay, so the question for founders is: How do you scale a company to $100M+ ARR, potentially get a premium valuation, and not end up like Trade Desk?

Here are the lessons:

First, sustain growth longer than you think you need to. Trade Desk's growth slowdown from 26% to 18% was partly inevitable (market maturation). But it was also partly choice. As a founder/management team, you can choose to invest to maintain growth longer. It costs more profit margin. But it protects valuation.

The companies that don't get crushed on repricing are the ones that manage to stay in "high growth" (20%+ range) even as competitors decelerate. This requires relentless reinvestment.

Second, diversify growth drivers. Trade Desk was too dependent on CTV growth (their fastest-growing segment). When CTV matured, overall growth decelerated. If you can build a portfolio of growth engines—some maturing, some new—you smooth out deceleration.

Third, be honest about market saturation. Trade Desk didn't clearly communicate that CTV was maturing. The market discovered it themselves. If you communicate clearly about market saturation and your plans to address it, the repricing is less brutal because it's less surprising.

Fourth, don't let your valuation get ahead of your execution. If you're trading at 90x earnings, the market is pricing in 25%+ growth forever. If you don't believe you can deliver that, you should be talking about it. Surprise misses crush premium-priced stocks. Proactive communication about slowdowns is far less punishing.

Fifth, build real defensibility beyond positioning. "We're independent" isn't a moat if the giants can replicate it with better resources. Build data advantages, network effects, switching costs, or switching friction. Trade Desk has some of this but not enough to prevent Amazon from competing directly.

The Path Forward for Trade Desk

Trade Desk isn't dead. They're not going bankrupt. They still have $1B in annual EBITDA. They still have the leading independent DSP. They still have great technologists and a strong product.

But they're in a hard position.

They need to demonstrate that growth can re-accelerate. That Amazon's DSP won't meaningfully eat into their market share. That they can find new growth vectors beyond mature CTV. All of this while their stock is under pressure, their ability to attract and retain talent is compromised, and their customers are getting more aggressive in negotiations.

It's doable. But it requires execution excellence. No more surprises. No more growth misses. No more C-suite weirdness.

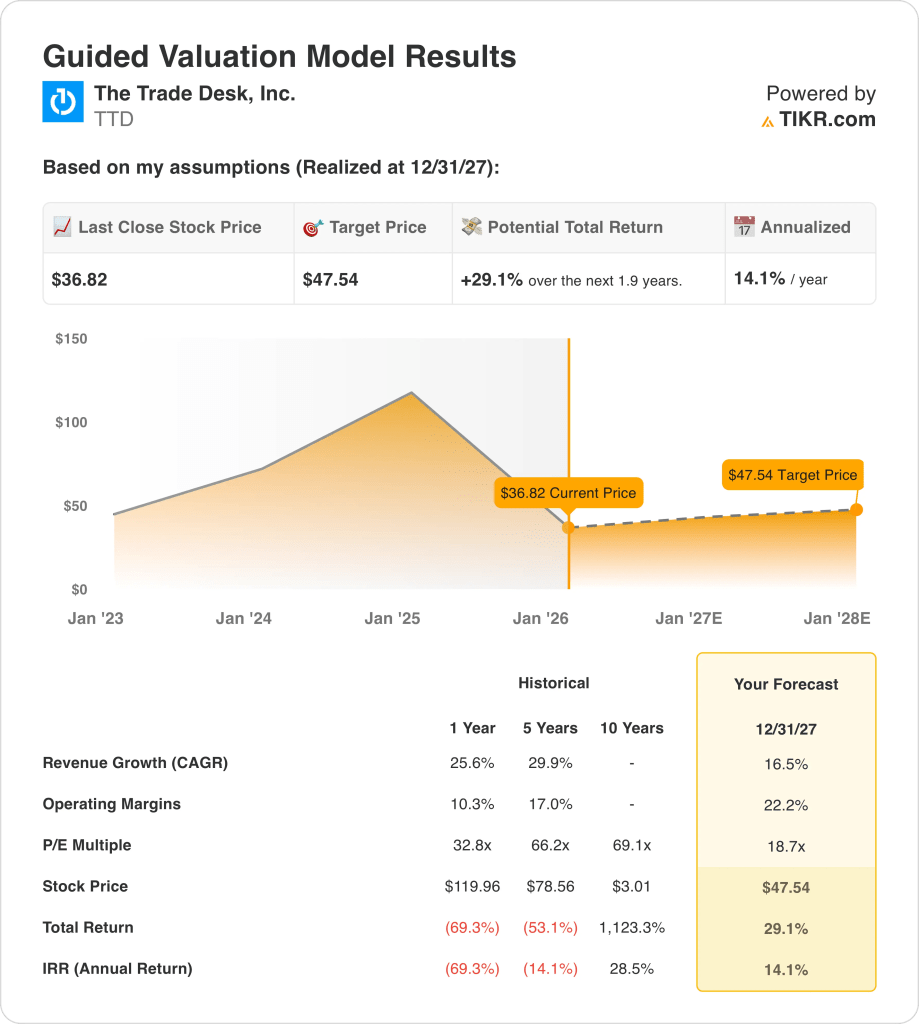

The next 2-3 quarters will be critical. If they can stabilize growth around 18-20% and communicate confidently about the path to re-acceleration, the stock will likely recover some losses. Maybe not back to

If they continue to disappoint, the stock could fall further.

For investors, Trade Desk is a classic value trap waiting to be a value investment. For employees, it's a company worth watching. They might re-accelerate and become a huge winner again. Or they might be a slow grind toward stagnation.

Founders should watch closely and ask: "What would I do differently in Trade Desk's position?" The answer to that question is worth gold.

What This Means for Your SaaS Company

Let's zoom back out to the meta-lesson here, because this isn't just about Trade Desk. It's about valuation mechanics and how premium-priced SaaS companies behave under pressure.

If you're building a B2B SaaS company and you eventually want to go public or raise growth capital at a premium valuation, you need to understand what you're actually signing up for.

A premium valuation (30x+ revenue, 60x+ earnings) is not a reward for good execution. It's a bet on continued growth. The moment you can't deliver that growth, the entire story reprices.

This is actually important for founders to understand before they take venture capital at a premium valuation, because it shapes how you have to run the company.

If you raise capital at 10x revenue, you have flexibility. Investors expect 20-25% growth and you have room to maneuver. Miss guidance by 5 points? No big deal.

If you raise capital at 40x revenue, you're signing up to deliver 25%+ growth consistently. Miss guidance by 5 points and investors get nervous. Miss by 10 points and you're in trouble.

The premium valuation comes with expectations baked in. You can't just "execute well" and manage that multiple. You have to execute at a specific level: persistent high growth.

Trade Desk is what happens when that execution bar isn't cleared. The repricing isn't irrational. It's mechanical. And it's brutal.

The Broader Market Lesson: Why This Matters Beyond Trade Desk

We can talk about Trade Desk in isolation, but the broader context is important too.

2020-2021 saw an explosion of premium-priced SaaS companies. The market was hungry for growth. Investors were willing to pay 40x, 50x, 60x+ revenue for companies growing 50%+ YoY.

Some of those companies (Datadog, Cloudflare, etc.) have managed to maintain high growth and justify premium multiples. Good for them.

But many have decelerated. And as they've decelerated, they've been repriced. This has happened to:

- Snowflake (though they've recovered some)

- MongoDB (repriced multiple times)

- Elastic (struggled with growth deceleration)

- Various other "unicorn" SaaS companies that were priced for perpetual 40%+ growth

The pattern is consistent: Companies priced for hypergrowth that deliver normalization-rate growth get crushed.

For founders raising capital now, the lesson is: Don't become seduced by premium valuations if you can't sustain premium growth. It's better to raise at 15x revenue and have flexibility than to raise at 40x revenue and be trapped on a growth treadmill.

Similarly, if you've already raised at a premium valuation, you now understand the obligation you've taken on. You need to sustain growth. You need to be honest about headwinds. You need to avoid surprises. It's a higher bar than running a "normal" SaaS company.

Trade Desk is expensive tuition for this lesson. Pay attention.

FAQ

What caused The Trade Desk stock to fall 73%?

The Trade Desk stock collapsed due to three interconnected factors: growth deceleration from 26% (2024) to 18% (Q3 2025), creating a valuation repricing for a company trading at 90x earnings; intensifying competition from Amazon, Google, and Meta building competing DSP capabilities; and C-suite instability with two CFO departures in six months, eroding investor confidence. The company was priced for perpetual 20%+ growth, so even a small miss triggered a complete narrative reset.

Why didn't Trade Desk's profitability protect the stock from falling?

Trade Desk generated over $1 billion in adjusted EBITDA in 2024 with strong margins, but profitability is table stakes at 90x earnings, not a differentiator. At premium valuations, the market pays for growth narrative, not profit optimization. When growth decelerated, the entire valuation thesis broke regardless of margins. This illustrates that Rule of 40 compliance doesn't protect premium-priced stocks from growth disappointments.

How does Amazon's new DSP threaten The Trade Desk's business model?

Trade Desk's core value proposition is independence—they serve as a neutral DSP that doesn't compete with customers. Amazon's DSP, combined with their retail data advantages and owned inventory (including Netflix partnerships), allows them to compete directly while offering exclusive resources Trade Desk can't match. Once giants start competing directly in your space, a positioning based on "not being them" becomes much less defensible.

What is the Rule of 40 and why didn't it save The Trade Desk?

The Rule of 40 states that revenue growth rate plus free cash flow margin should equal 40 or higher, indicating a healthy, balanced company. Trade Desk was hitting this metric (25%+ growth plus 25%+ margins), but it's irrelevant when a company is priced at 90x earnings. Premium valuations embed aggressive growth expectations, so Rule of 40 compliance is assumed, not rewarded. The market reprices based on growth trajectory, not margin quality.

How does valuation multiple compression affect stock price decline?

Stock price decline from growth deceleration isn't linear because it's driven by terminal value repricing. If investors reduce growth rate assumptions from 25% to 18%, they must recalculate all future cash flows discounted backward. Terminal value typically represents 60-70% of total valuation, so adjusting growth assumptions can change stock price 50-80%. Trade Desk's 73% decline reflects this mathematical repricing, not a judgment that the business became bad.

What should founders learn from The Trade Desk's collapse?

Founders scaling toward $100M+ ARR should understand that premium valuations carry obligations: you must sustain premium growth, communicate proactively about headwinds, diversify growth drivers to avoid relying on maturing segments, build defensible competitive advantages beyond positioning, and avoid surprise misses at all costs. If you can't deliver 20%+ growth consistently, don't accept a valuation that assumes it. Surprise misses trigger disproportionate repricing because premium multiples are fragile.

Can The Trade Desk recover from this stock decline?

Recovery requires The Trade Desk to stabilize growth at 18-20%, clearly communicate the path to re-acceleration, defend market share against Amazon and other giants, and restore C-suite stability. The company still has strong fundamentals (

The Final Word: Growth Is Everything at the Top

There's a tendency to look at Trade Desk's collapse and think, "Well, that's a weird edge case." It's not.

What happened to Trade Desk happens to most premium-priced SaaS companies when growth decelerates. Sometimes it's 40%. Sometimes it's 60%. Trade Desk got 73% because they had the furthest to fall and hit the headwinds all at once.

But the pattern is consistent across every premium-priced company that decelerates: The stock reprices viciously.

For founders, this should shape how you think about growth, valuation, and the obligations you take on when you raise capital at premium multiples.

You can run a $100M ARR company that grows 12% and be very profitable. That's a great business. You can raise capital for it at a reasonable multiple (maybe 8-10x revenue). You'll have flexibility. You can optimize for profitability. You can be patient about growth initiatives.

Or you can build a $100M ARR company that grows 30% and raise capital at a premium multiple. You'll have more prestige, more capital, more resources. But you'll also have higher expectations. You'll be on a growth treadmill. You can't step off. The moment you decelerate, the valuation resets.

Trade Desk chose the second path. For years, it was brilliant. Hypergrowth, premium valuations, founder credibility, everything working.

Then growth slowed. And everything repriced.

The lesson isn't that growth slowing is bad. The lesson is that being priced for perpetual growth is dangerous. Once you're priced that way, you're trapped. You have to deliver. Miss by even a few points, and the entire story breaks.

Understand this dynamic before you raise at premium multiples. Because once you're there, you're on the treadmill. And stepping off costs everything.

That's the real lesson of Trade Desk. Not that they're a bad company. But that they got priced for perfection. And when perfection slipped just a few points, the market repriced everything.

Make sure your company doesn't end up there.

Key Takeaways

-

Premium valuations embed perpetual growth assumptions: At 90x earnings, investors pay for 20%+ growth forever. Deliver 18% and the entire valuation reprices brutally.

-

Profitability doesn't protect premium-priced stocks: Trade Desk generated $1B+ in EBITDA while their stock fell 73%. Margins are table stakes at premium multiples, not differentiators.

-

Competition from giants destroys positioning-based moats: "We're independent" only matters if giants can't replicate independence. Amazon did, making Trade Desk's core value prop less unique.

-

Growth deceleration creates operational headwinds: Lower stock prices trigger talent retention issues, harder customer negotiations, and reduced M&A flexibility that make future growth even harder.

-

Be honest about growth expectations before taking premium capital: Don't raise at 40x revenue if you can only deliver 18% growth. The repricing when you miss is mechanical and brutal.

-

Sector-wide compression amplifies individual company repricing: When the whole adtech sector reprices down, premium-priced players like Trade Desk fall hardest because they have the furthest to drop.

-

C-suite instability kills confidence in premium-priced companies: Leadership changes get interpreted as "the ship is in trouble" when the stock is already under pressure, accelerating the decline.

Related Articles

- This Week in Tech: Samsung's TriFold Craze, Google's New OS, and Browser Wars [2025]

- Extraordinary Under Salt Marsh Episode 2: The Unscripted Scene That Changes Everything [2025]

- How to Film ICE & CBP Agents Legally and Safely [2025]

- Tech News January 2025: Samsung S26 & Garmin Whoop Features

- Best Netflix Action Movies for an Epic Weekend Binge [2025]

- Why Businesses Fail at AI: The Data Gap Behind the Divide [2025]

![Why The Trade Desk Stock Collapsed: SaaS Growth Lessons [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-the-trade-desk-stock-collapsed-saas-growth-lessons-2025/image-1-1769861210330.jpg)