The Real Estate Industry's Uncomfortable Truth About Climate Risk

Last November, millions of homebuyers lost access to critical information about their properties. Zillow, the nation's largest real estate platform, quietly removed climate risk scores from its listings. No announcement. No warning. Just gone.

The move shocked climate scientists, environmental advocates, and informed consumers alike. After all, this wasn't some niche feature. Climate risk data had been live for just over a year, and it was doing exactly what it was supposed to do: helping people understand real threats to their homes and investments.

So why did Zillow pull the plug? The answer reveals something uncomfortable about how American real estate markets operate. The California Regional Multiple Listing Service, which controls property listing databases for thousands of agents across the state, pressured Zillow to remove the data. Their concern? They questioned the accuracy of flood risk models from First Street, a climate risk modeling company that powers climate risk displays across the industry.

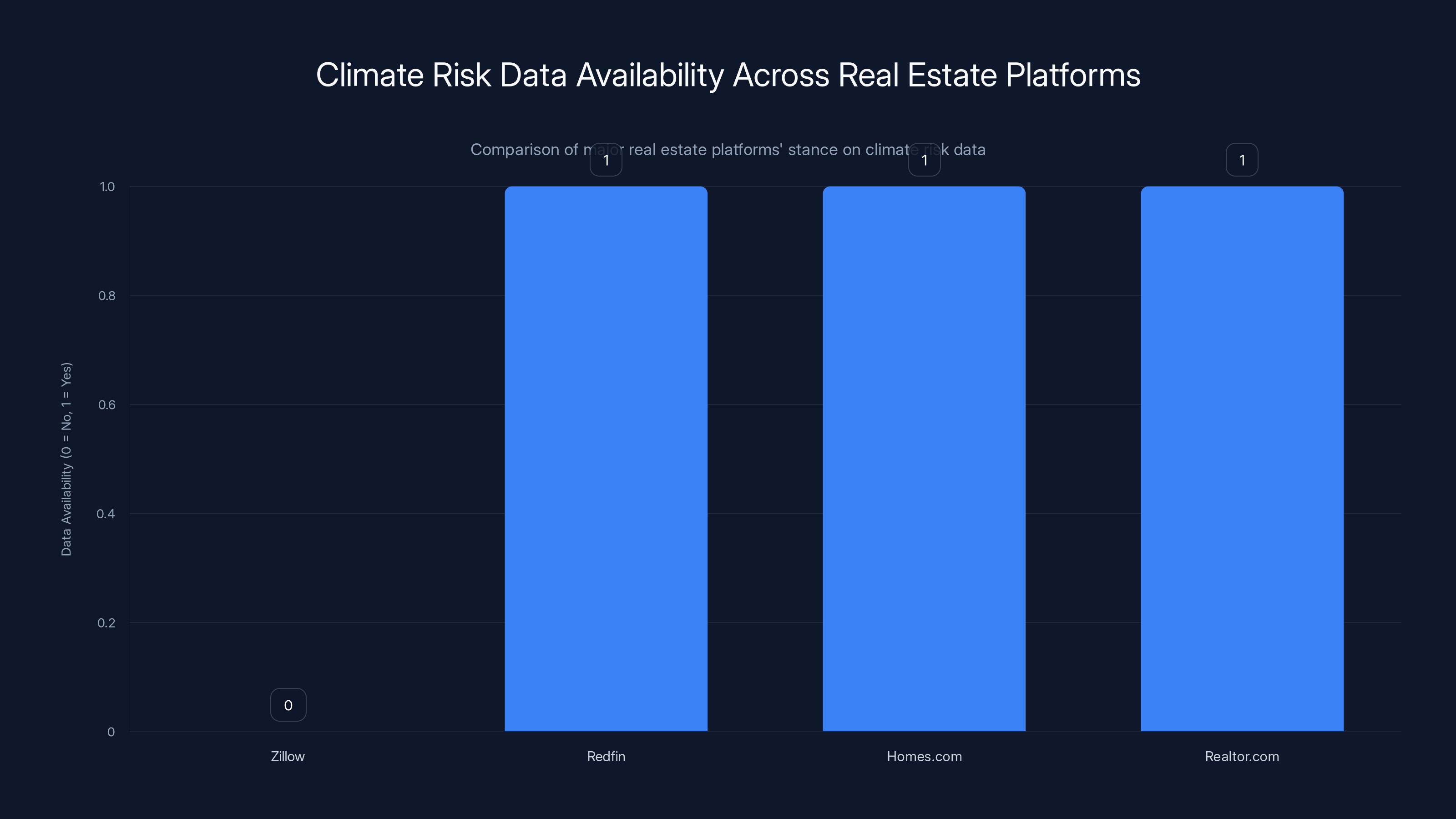

But here's where things get interesting. Other major real estate platforms continued displaying First Street data. Redfin kept it. Homes.com kept it. Realtor.com kept it. Only Zillow capitulated. And now, a climate policy expert named Neil Matouka is working to restore what the market tried to hide.

This isn't just a story about real estate marketing. It's about information asymmetry, climate risk quantification, and who gets to decide what homebuyers are allowed to know about their investment. And it matters more than you might think.

The Perfect Storm of Market Pressure and Climate Uncertainty

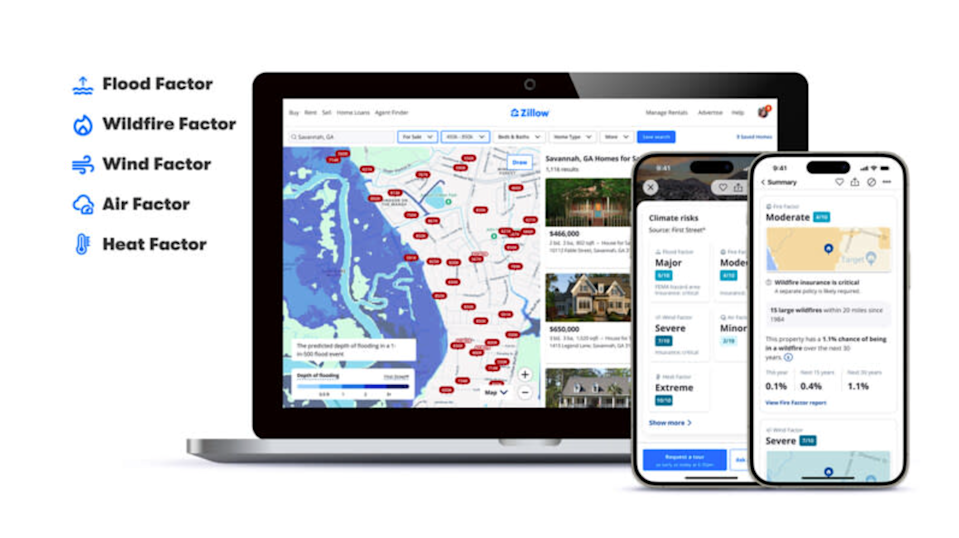

Zillow introduced climate risk data in October 2024, marking the first time a major real estate platform integrated comprehensive climate scoring into property listings at scale. The data covered five categories: flood risk, wildfire risk, wind risk, heat exposure, and air quality. For homebuyers accustomed to opaque climate disclosures, it felt like a breakthrough.

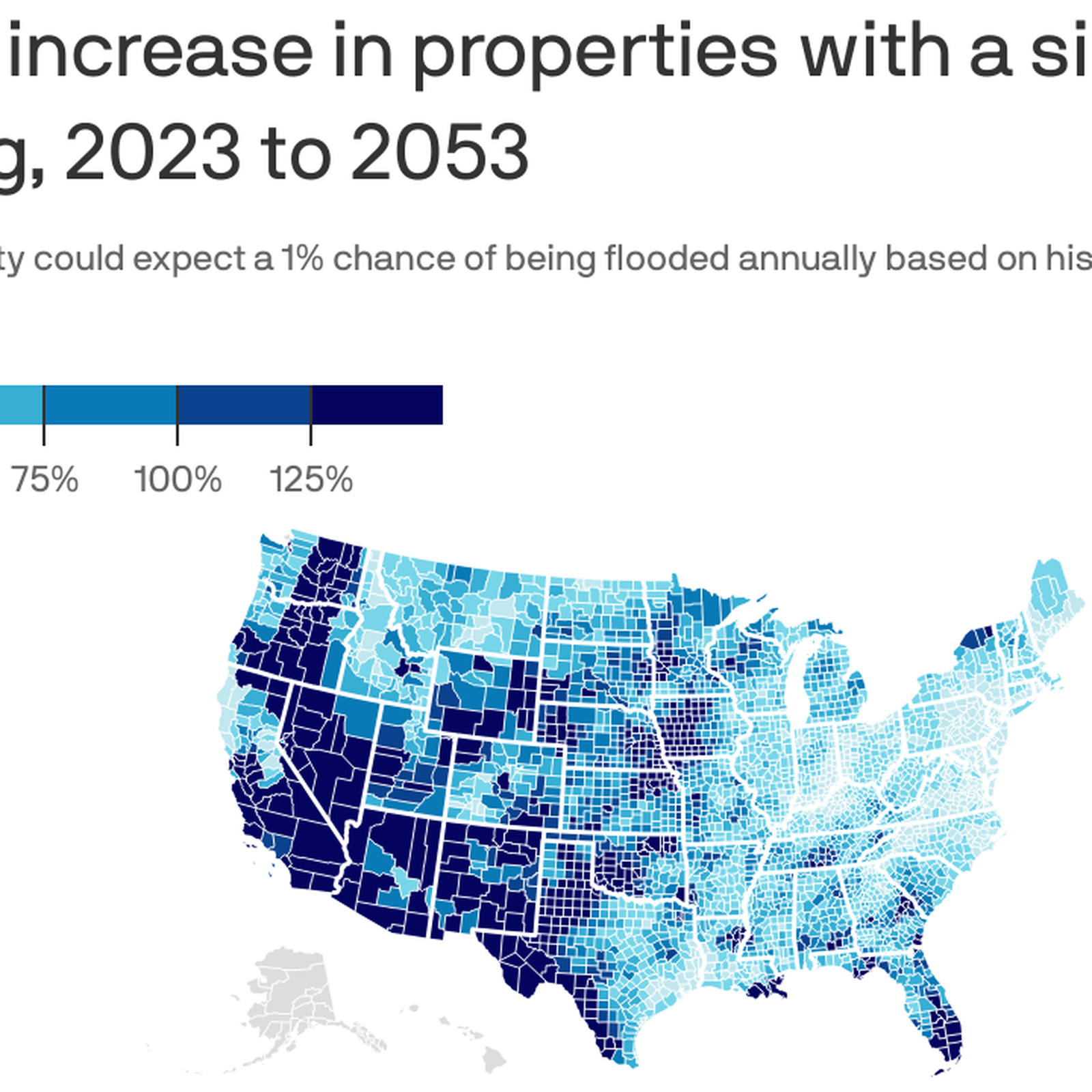

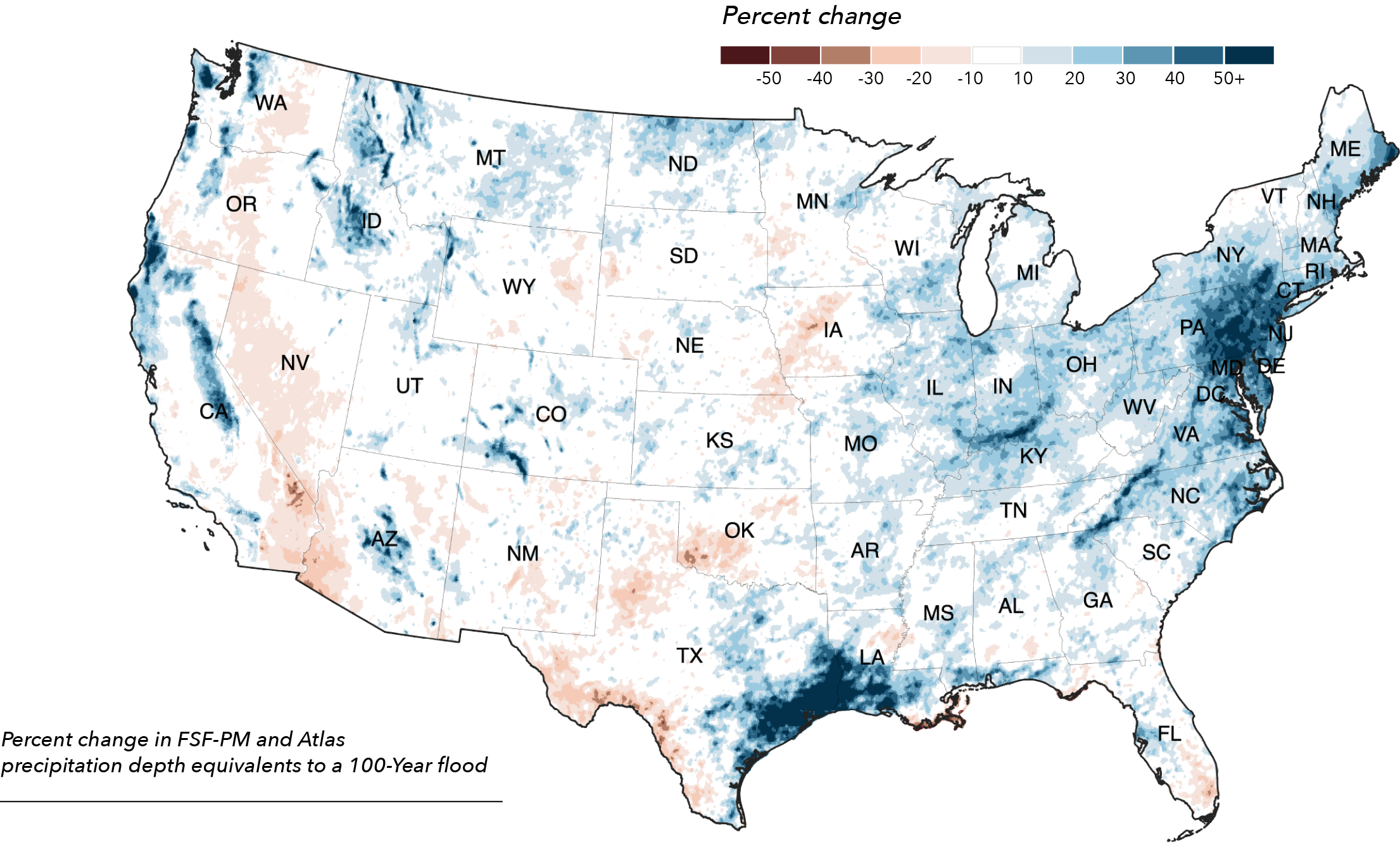

Then the California Real Estate Association's largest database provider got nervous. The California Regional Multiple Listing Service issued a statement questioning First Street's flood modeling methodology. Their specific concern: First Street's models showed significantly more properties at flood risk compared to Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) flood maps.

Now, this criticism wasn't entirely unfounded. FEMA's flood maps are genuinely problematic. They're outdated, use crude modeling, and fail to account for modern climate patterns. Academic researchers have documented these shortcomings for years. But here's the catch: even if FEMA's maps are worse, that doesn't make them less legally binding or less influential in property transactions.

Zillow faced a difficult choice. Stand firm on accurate climate data and face potential listing disputes in California, or remove the feature to appease the MLS. The company chose the latter.

Understanding the Climate Risk Data Gap

When Zillow removed its climate risk feature, it didn't just eliminate a convenience for homebuyers. It created an information vacuum in one of the most important financial transactions people make.

Climate risk isn't theoretical anymore. Across the United States, communities face increasingly severe exposure to floods, wildfires, extreme heat, and other climate-related hazards. In California specifically, where Zillow made its retreat, wildfire exposure has become catastrophic. The state experiences more acres burned annually than any other state, with 2023 seeing over 2.6 million acres burned. Flood risk is similarly intensifying, with atmospheric rivers delivering unprecedented precipitation.

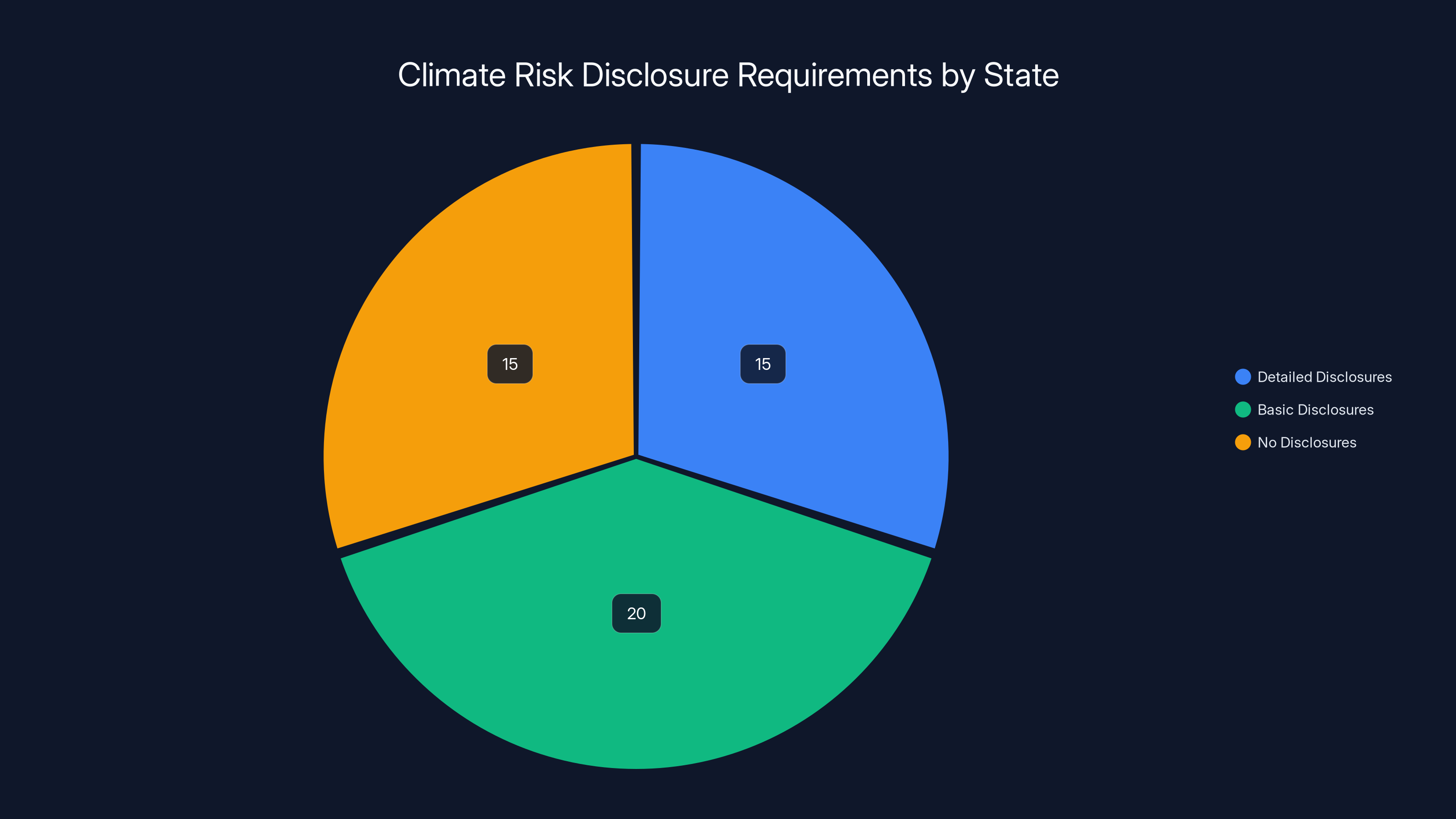

Yet despite this reality, property disclosures remain fragmented and inconsistent. Some states require detailed climate risk disclosures. Others mandate almost nothing. Homebuyers interested in understanding climate exposure to their potential purchase often find themselves navigating a patchwork of federal, state, and private data sources, each with different methodologies and varying degrees of accuracy.

This creates a fundamental market failure. Sellers have incentives to downplay climate risks. Real estate agents have incentives to keep transactions moving. Platforms like Zillow face regulatory pressure from industry groups. And homebuyers—the people actually bearing climate risk through their property purchases—are left with incomplete information.

The First Street Methodology Question

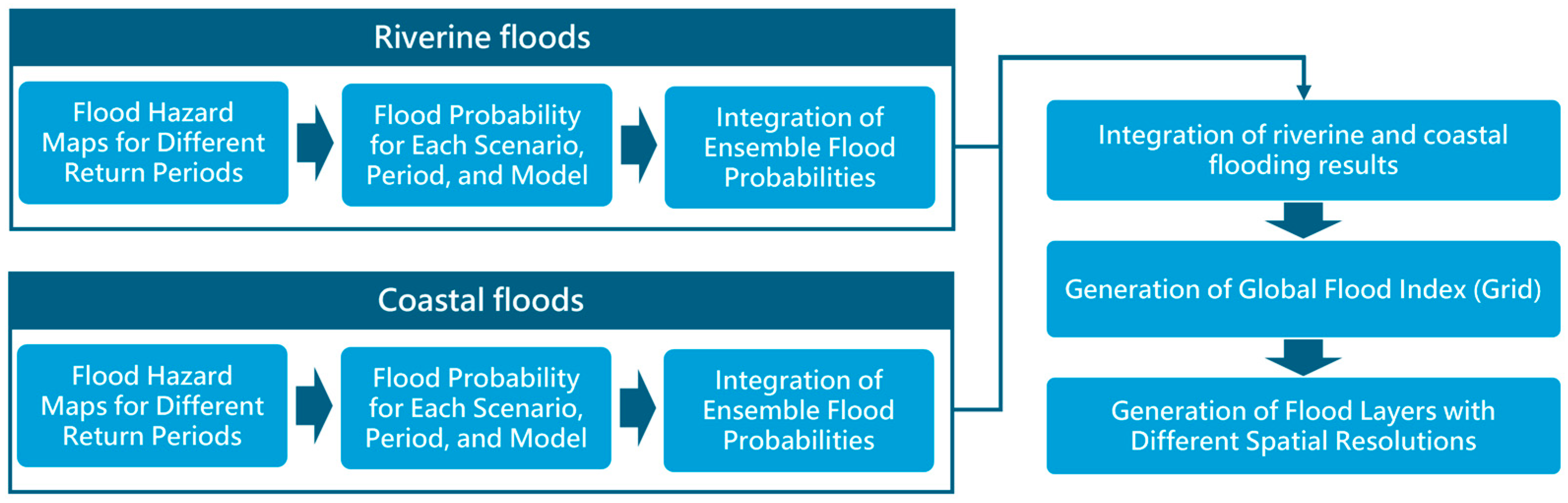

First Street Foundation, the climate risk modeling company behind the data Zillow removed, uses sophisticated machine learning and hydrological modeling to generate property-level climate risk assessments. Their flood models incorporate historical flood events, precipitation patterns, elevation data, and infrastructure information to generate probabilistic flood risk estimates.

Their approach differs from FEMA's in important ways. First Street models use higher-resolution data and account for modern climate patterns. They don't rely solely on historical 100-year flood delineations. Instead, they generate probability distributions showing risk across multiple return periods.

But this sophistication creates communication challenges. When First Street's models show a property at flood risk that FEMA's maps don't include, confusion follows. Real estate professionals unfamiliar with probabilistic modeling interpret this as inaccuracy. In reality, First Street might be capturing legitimate risk that FEMA's maps miss entirely.

First Street has defended its methodology rigorously. The company notes that their models are built on peer-reviewed science, validated against real-world flood outcomes, and continuously refined based on actual events. When flooding occurs, First Street researchers compare predicted risk to actual outcomes, using real-world data to improve their models iteratively.

Independent research supports First Street's approach. Studies have shown that First Street's flood risk designations correlate strongly with actual flood damage patterns, while FEMA's designations often miss properties that experience repeated flooding.

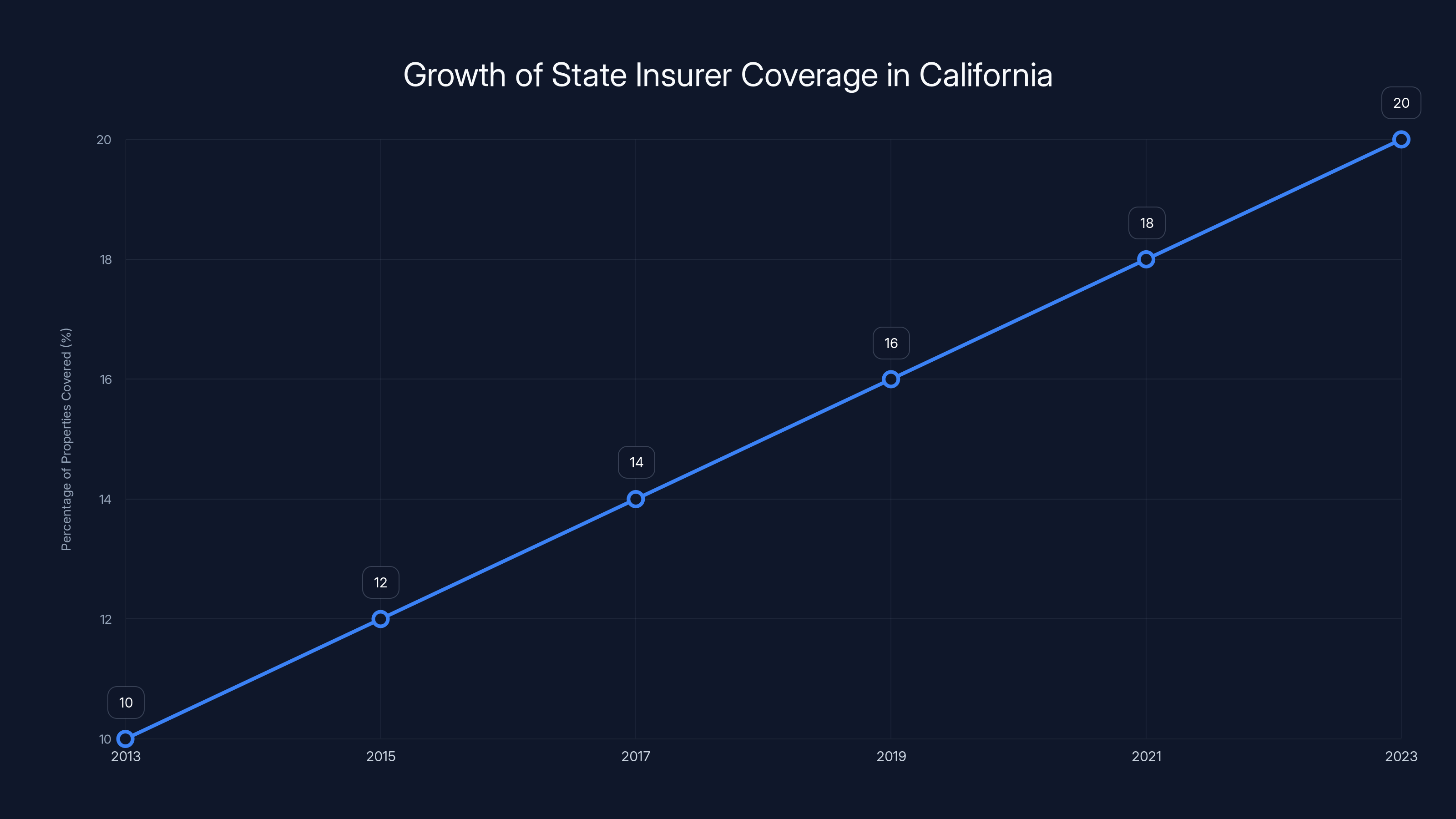

The state insurer's coverage in California has doubled over the past decade, primarily due to increased wildfire risks. Estimated data.

The Academic Perspective on Climate Risk Modeling

Chris Field, director of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, has written extensively about the trade-offs in climate risk modeling. His work highlights a fundamental tension: the more geographically specific you try to make climate projections, the less precise they become.

This isn't because modelers are incompetent. It's because climate systems are chaotic at local scales. A microclimate on one side of a hill can differ dramatically from the other side. In flood risk modeling specifically, elevation differences of just a few feet can determine whether a property floods in a 50-year storm. These details matter enormously for individual properties but are genuinely difficult to capture with perfect accuracy.

Field argues that climate risk models are most useful for characterizing "broad environment of risk" rather than making precise property-specific predictions. This distinction matters because it shifts the conversation. Instead of asking whether a model is perfectly accurate for a specific property, we should ask whether it reliably identifies areas of elevated risk and helps people understand relative exposure.

Another key insight from environmental economists: people making decisions involving risk benefit substantially from exposure to multiple independent credible estimates. If you only see FEMA's assessment, you're missing information. If you only see First Street's assessment, you're potentially overweighting one methodological approach. Ideally, homebuyers would see multiple risk assessments and understand where they converge and diverge.

Jesse Gourevitch, an economist at the Environmental Defense Fund, emphasizes that moving toward better climate risk transparency requires transparency in modeling methodology. When private companies develop climate risk models but keep their methods proprietary, it becomes impossible for regulators, researchers, or consumers to audit their accuracy or understand their limitations.

The California Advantage: Public Data as a Solution

California possesses climate risk data assets that most states envy. The state maintains extensive public databases on fire risk, flood risk, heat exposure, and air quality. These datasets are freely available, come with detailed methodology documentation, and are updated regularly based on new science.

This public data infrastructure enabled Neil Matouka to develop his proof-of-concept plugin without relying on proprietary models. Matouka, who previously managed California's Fifth Climate Change Assessment (a comprehensive scientific review of climate impacts statewide), understands how to synthesize complex climate information into usable formats.

His plugin pulls from multiple California state datasets and federal resources, including the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection's fire hazard severity zones, flood inundation mapping from state water agencies, and heat exposure analysis from California's own climate research institutes. The plugin automatically displays this information when users view properties on Zillow in California.

The approach has significant advantages. All underlying data comes from public sources with transparent methodologies. The data collection and maintenance is funded by public agencies with no financial incentive to downplay climate risks. And because California's climate agencies regularly update their assessments, the plugin data reflects current scientific understanding.

But here's the limitation: California's advantage is geographic. Other states haven't invested as heavily in public climate risk databases. Replicating Matouka's approach nationwide would require either massive public data infrastructure investment or reliance on proprietary models from companies like First Street.

The Challenge of Scaling Transparency

Roslyn Dakin, a climate adaptation specialist, points out that public data availability varies dramatically across regions. Colorado has invested in detailed wildfire risk mapping. Florida has flood risk data from state water management districts. But many states have gaps. Some rural counties have virtually no high-resolution climate risk data available in public form.

Private sector companies have filled this gap by investing billions in climate risk modeling. Companies like First Street, Jupiter Intelligence, and others have developed proprietary models using machine learning, satellite data, and historical outcomes. This innovation is genuinely valuable. But it comes with a cost: these models aren't transparent, and companies have financial incentives to maintain market advantage rather than open-source their approaches.

For climate risk transparency to become standard in real estate markets, we need both public data infrastructure investment and clearer standards for private models. That means funding state and local climate risk assessments at scale, establishing clear disclosure requirements for properties in high-risk areas, and creating standards for how climate risk information gets displayed in real estate transactions.

Modern climate risk models are estimated to be 10% more accurate than FEMA flood maps in identifying flood hazards. Estimated data.

Why Homebuyers Actually Care About Climate Risk Data

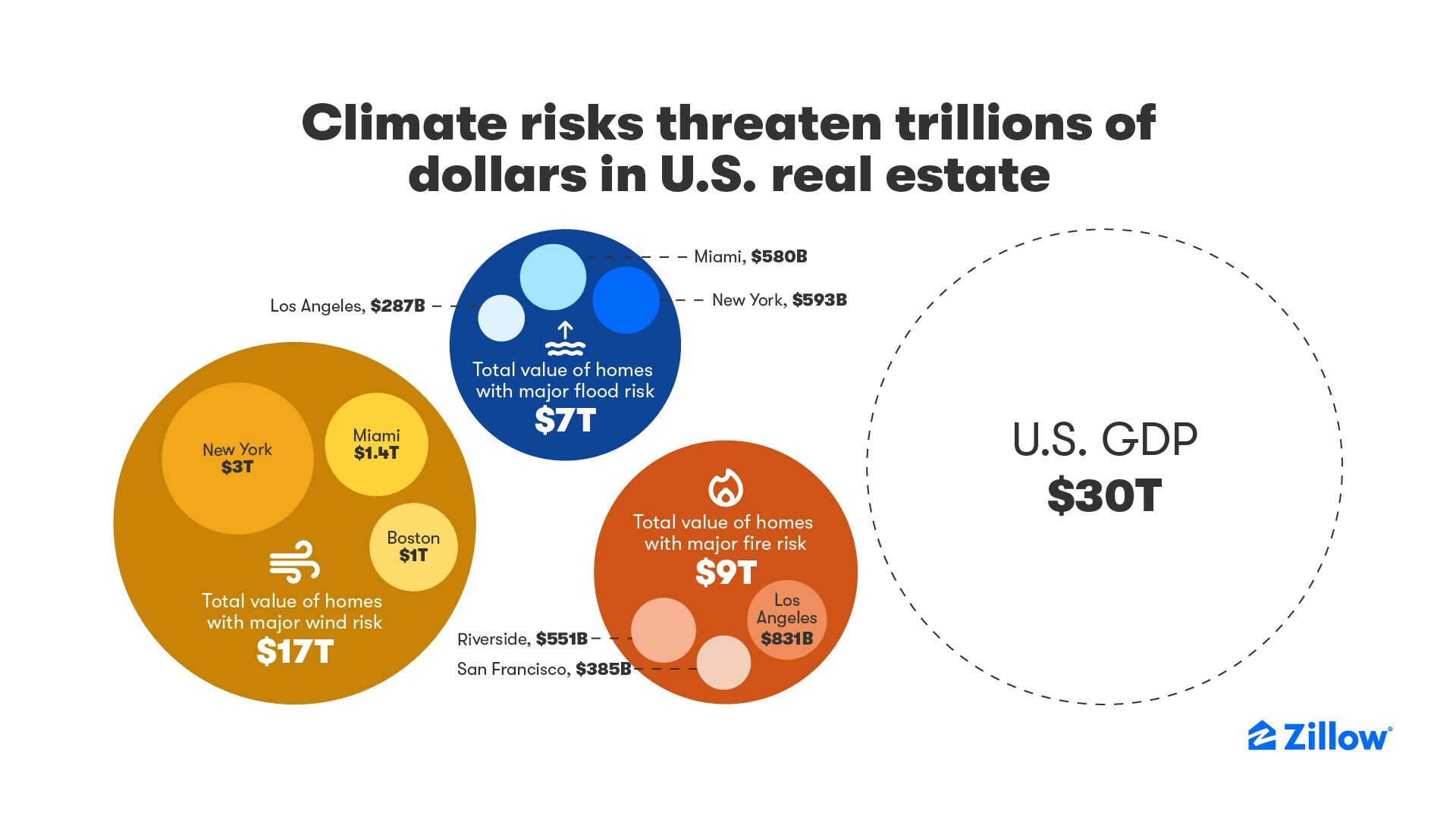

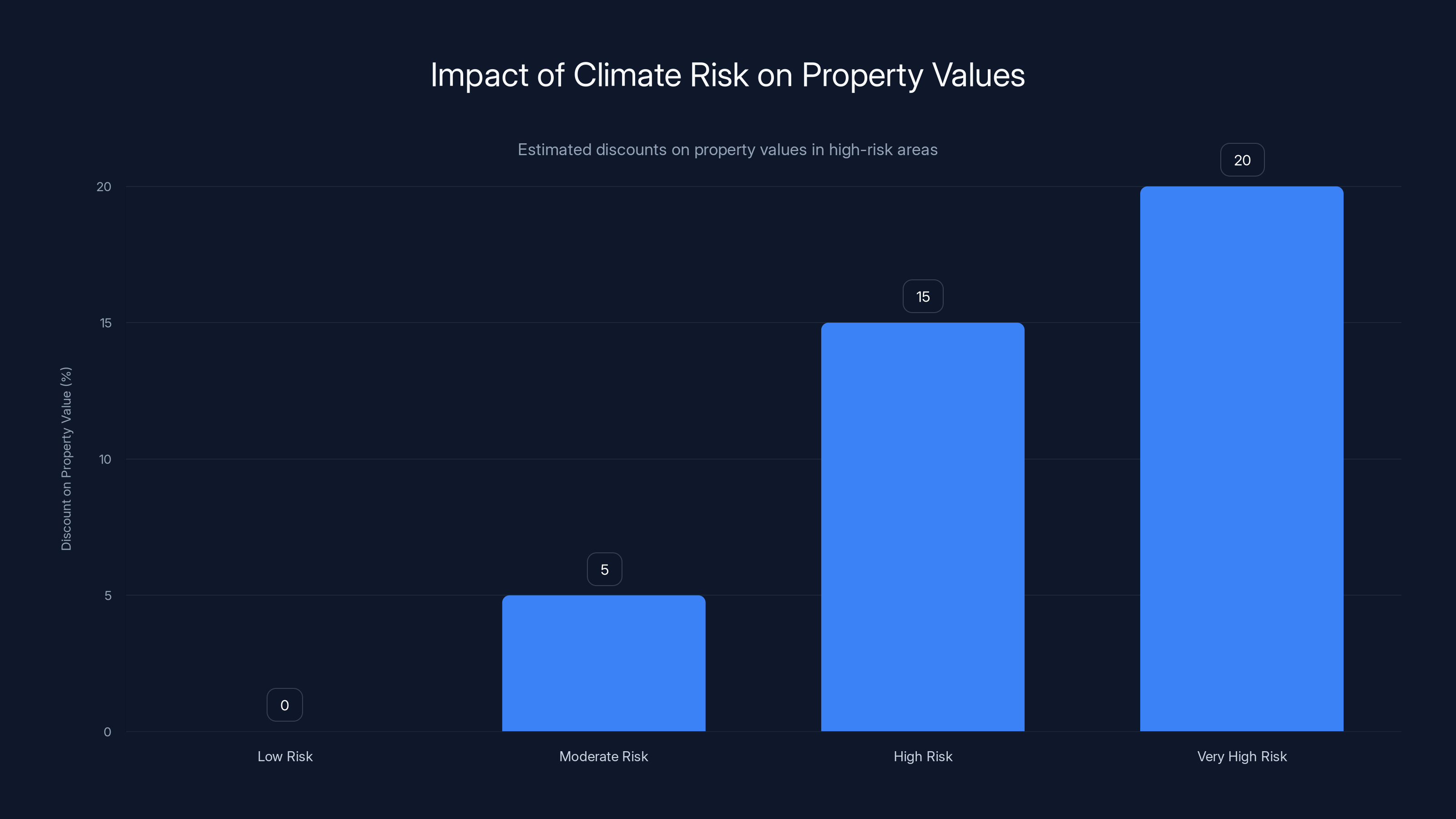

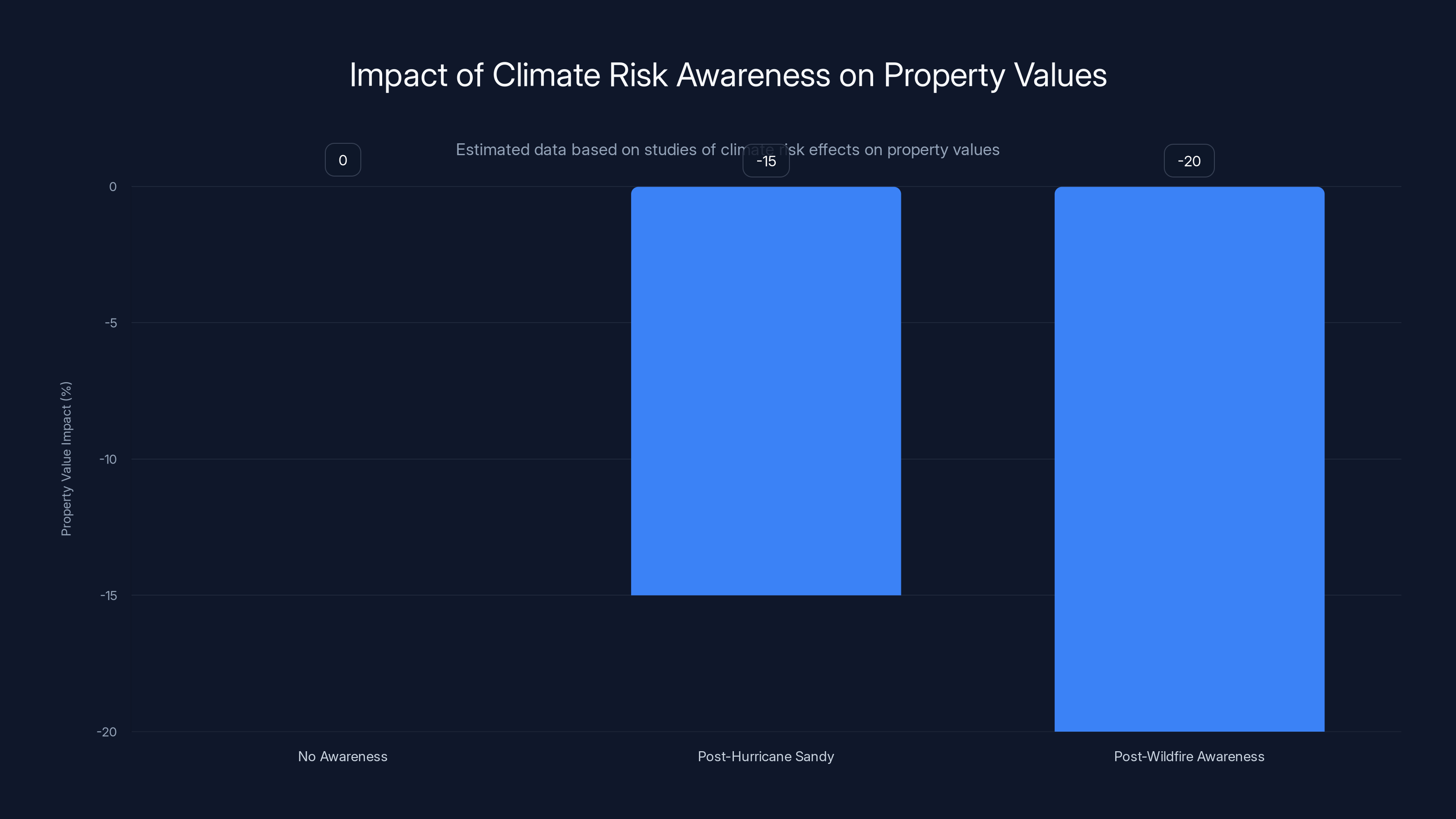

The stakes aren't abstract. Climate risk affects property values, insurance costs, and long-term livability. Research from both academic institutions and Zillow itself has documented that flood risk disclosure significantly impacts property values. Homes in high-risk areas face discounts ranging from 5% to 20% once risk becomes widely known.

This creates perverse incentives. If you're a homebuyer and climate risk information is hidden, you might overpay for a property. If you're a seller or real estate agent, you have incentives to keep that information hidden. The information asymmetry directly impacts wealth transfer, which is why the industry fought so hard to keep climate data off Zillow.

But beyond property values, climate risk affects insurance costs. Homeowners insurance is increasingly becoming unavailable or unaffordable in high-risk areas. Some California counties have seen homeowners insurance companies exit entirely, forcing residents into the state insurer of last resort. If you buy a property without understanding flood or fire risk, you might discover after closing that insurance is either impossible to obtain or costs $4,000+ annually.

Long-term livability matters too. Extreme heat exposure affects quality of life, health outcomes, and utility costs. Wildfire smoke impacts air quality and respiratory health. Flooding threatens both property and personal safety. These aren't just financial considerations; they're fundamental quality-of-life issues.

The Matouka Plugin: Restoring Information Access

Neil Matouka's solution is elegant in its simplicity. Instead of trying to convince Zillow or other platforms to reinstate climate data, he built a browser plugin that overlays climate information directly on property listings. When a user views a California property on Zillow, the plugin automatically displays wildfire risk, flood risk, sea level rise potential, and extreme heat exposure.

The plugin is designed to communicate what Matouka calls "standing potential risks in the area" rather than making specific property-level predictions. This distinction is important. The plugin shows risk categories and severity levels but acknowledges the inherent uncertainty in property-specific climate projections.

The beta version uses public California data sources exclusively. The data comes from the state's climate assessment process, the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, water agencies, and other public sources with transparent methodologies. This approach sidesteps the proprietary model debate entirely.

Matouka is particularly thoughtful about accuracy and transparency. He's explicit about data limitations, clearly labels which data comes from which source, and explains the underlying methodologies. Rather than presenting climate risk as a single definitive score, the plugin shows multiple data types so users understand the full picture.

The reception so far has been positive among climate advocates and informed consumers. Environmental nonprofits see the plugin as an important tool for democratizing climate risk information. Real estate professionals have been less enthusiastic, which is unsurprising given that transparent climate data tends to complicate transactions in high-risk areas.

Practical Implementation and Technical Details

Matouka's plugin works by injecting climate risk data into Zillow's property pages using publicly available APIs and datasets. When the plugin loads a property, it queries California's climate databases, retrieves relevant risk data for that geographic location, and displays it prominently.

The plugin integrates data from multiple sources:

- California's fire hazard severity zones (from the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection)

- Flood inundation mapping (from the state's water agencies and USGS)

- Sea level rise projections (from the California Coastal Commission)

- Heat exposure analysis (from California's own climate research institutions)

One challenge is matching property locations to the resolution of available climate data. Some datasets use fine resolution (down to individual properties), while others use broader geographic units. The plugin handles this by showing both specific property-level data where available and area-level risk where property-specific data doesn't exist.

The technical architecture is intentionally simple. Rather than requiring users to install software or create accounts, the plugin works as a browser extension that intercepts Zillow pages and adds information automatically. This keeps the barrier to adoption minimal.

Matouka is transparent about the plugin's limitations. It only works in California (where public data is most available). It doesn't replace comprehensive due diligence by homebuyers. And it relies on the assumption that users can interpret climate risk data accurately, which isn't always true.

The Broader Real Estate Market Response

While Zillow retreated from climate risk disclosure, competitors didn't follow. Redfin, Homes.com, and Realtor.com all continued displaying First Street data. This fragmentation creates its own problems. Sophisticated homebuyers can find climate risk data elsewhere, while less savvy buyers might miss it entirely.

The divergent responses also reveal something about competitive dynamics. Companies willing to absorb the friction with real estate industry groups maintain transparency. Companies prioritizing relationships with real estate professionals step back. This isn't necessarily cynical; it reflects genuine tension between different stakeholder interests.

Some regional real estate platforms have started developing their own climate risk assessments rather than relying on First Street. These platforms invest in proprietary models tailored to regional risks. In Florida, for example, several platforms have developed specialized flood and hurricane risk assessments that account for local infrastructure, elevation data, and storm surge modeling.

The market response suggests that complete transparency is possible—some platforms are doing it successfully. But it requires either significant investment in proprietary model development or willingness to integrate external data even when it complicates transactions.

Homes in high-risk areas face property value discounts ranging from 5% to 20% due to climate risk. Estimated data based on typical risk assessments.

Why Information Asymmetry Matters in Real Estate

Real estate markets are fundamentally different from other commodity markets because properties are unique, illiquid, and expensive. When information asymmetries exist, the impact is magnified. A homebuyer making the largest purchase of their life with incomplete information faces dramatically different risk than a consumer buying a commodity product.

Economic research on disclosure requirements in real estate shows consistent patterns. When previously hidden information becomes public, prices adjust. Properties facing climate risks see discounts. But the discount occurs unevenly—first to sophisticated buyers who understand climate science, then more broadly as awareness spreads.

This creates both social and economic concerns. Economically, it raises fairness questions about who bears the cost of information asymmetry. Socially, it affects which communities face climate impacts without adequate preparation or adaptation investment.

Shelly Sorensen, a policy researcher at the National Bureau of Economic Research, has studied how climate risk disclosure affects different demographic groups. Her research shows that homebuyers in lower-income communities and communities of color are less likely to have access to climate risk information, and more likely to face discrimination in lending once risks become widely known. Information transparency, in this context, is actually a fairness issue.

The Role of Transparency in Market Correction

Economic theory suggests that transparent information improves market efficiency. When buyers understand property risks, prices reflect true expected values. Without that information, prices deviate from fundamentals, creating mispricing.

Climate risk information is particularly important because it affects both current property values and long-term risk. A property that seems like a good purchase at current prices might become uninhabitable or uninsurable in 20 years. Buyers without climate risk information can't accurately assess long-term value.

The research on climate disclosure effects is pretty clear: once climate risk becomes salient to homebuyers, it significantly impacts value. Studies of Hurricane Sandy in New York, for example, showed that properties in affected areas faced permanent value adjustments even years after the hurricane. This wasn't temporary shock; it reflected permanent shifts in risk perception.

Similarly, research on wildfire-exposed properties in California and Colorado shows that once residents become aware of fire risk (usually through experiencing actual fires), property values in high-risk areas decline substantially. The decline isn't uniform; properties with defensible space and fire-hardening features face smaller discounts. But overall, risk awareness creates value correction.

This is actually efficient market behavior. The question isn't whether climate information should affect prices (it should). The question is whether that price adjustment should happen through informed consumer choice or through costly experience (actual property loss, insurance denial, etc.).

Matouka's argument is straightforward: better information enables better decisions earlier, before people experience loss. That's both economically efficient and humane.

Expert Opinions on Climate Risk Transparency

The scientific and policy communities are broadly aligned on the importance of climate risk transparency. Where they diverge is on the best mechanisms for implementation.

Climate scientists emphasize that perfect accuracy shouldn't be the enemy of useful information. Climate change is inherently uncertain, and local impacts are difficult to predict with precision. But that uncertainty shouldn't eliminate disclosure. Instead, it should shape how information is presented—with clear uncertainty bounds, multiple data sources, and honest acknowledgment of limitations.

Economic researchers emphasize that transparency creates more efficient markets. When homebuyers understand risks, they price them into their offers. This creates appropriate price signals that encourage adaptation investment in high-risk areas. Without transparency, adaptation investment is delayed until after costly experiences force action.

Insurance industry experts note that insurers already incorporate climate risk into pricing. So climate risk information that homebuyers use isn't novel from a risk assessment perspective—it's just making explicit what the insurance industry already prices in. From this perspective, transparency simply makes price signals more visible.

Real estate industry professionals raise legitimate concerns about model accuracy and the risk of oversimplifying complex local conditions. A property might face elevated flood risk according to one model but have protective infrastructure that significantly reduces actual risk. These nuances matter and shouldn't be lost in broad climate risk categories.

Estimated data shows that climate risk disclosure requirements vary across states, with a significant number having basic or no requirements.

The Data Quality Debate: FEMA vs. Modern Models

FEMA's National Flood Insurance Program was established in 1968. The flood maps that delineate 100-year flood zones were designed to create a standard for insurance requirements and land use planning. But they use methodology that's, frankly, outdated.

FEMA's maps are based on statistical analysis of historical flood records. They identify 100-year floodplains by analyzing where floods have occurred in the past and projecting that pattern forward. The problem is that climate change is fundamentally altering precipitation patterns, extreme weather frequency, and flood behavior. Historical patterns are increasingly poor predictors of future risk.

Research from the U.S. Geological Survey and independent academic studies has documented systematic underestimation of flood risk in FEMA maps, particularly for urban areas with altered hydrology, for properties near streams in rapidly developing watersheds, and for regions experiencing climate-change-intensified precipitation.

Modern models like First Street's use machine learning to incorporate diverse data sources: satellite imagery of terrain and infrastructure, detailed elevation data from LIDAR mapping, historical flood events, current precipitation patterns, climate change projections, and more. These models can generate probabilistic risk estimates showing risk across different return periods (10-year, 50-year, 100-year, 500-year flood events).

The trade-off is complexity. FEMA maps are simple (you're either in the floodplain or not). Modern models are nuanced (you face a 2.4% annual probability of flooding, which compounds to a 27% probability over a 30-year mortgage). Simplicity is easy to communicate but potentially misleading. Nuance is more accurate but harder to understand.

Neither approach is perfect. But the question isn't whether to use perfect data. It's whether to use better data. By that standard, modern climate risk models represent genuine improvement over FEMA's maps, even if they're not perfect.

The Insurance Market Response to Climate Risk

The insurance industry has been ahead of real estate on climate risk quantification. Insurers have sophisticated models of climate risk because their business model depends on accurate risk pricing. If they underestimate climate risk, they face catastrophic losses.

Homeowners insurance has become increasingly difficult to obtain in high-risk areas. State insurers of last resort (which exist in most states) are filling gaps left by private insurers fleeing high-risk regions. In California, the state insurer has grown from covering about 10% of properties a decade ago to covering nearly 20% today. This growth is almost entirely driven by properties in wildfire-risk zones.

Insurance costs have become a leading indicator of climate risk. Properties facing significant climate risk often face insurance costs that exceed 3-5% of property value annually. In extreme cases, insurance becomes unavailable at any price, effectively making properties unsellable through conventional financing.

This creates an ironic situation: by keeping climate risk information off real estate platforms, the industry creates information asymmetry that allows people to buy properties they couldn't profitably insure. The insurance market then corrects this with massive price shocks when policies renew.

Matouka's approach, which makes climate risk visible before purchase, actually aligns with insurance market incentives. If buyers understand climate risk upfront, they can make informed decisions about whether the property's price reflects true expected costs including insurance.

Environmental Justice Dimensions of Climate Risk

Climate risk disclosure has profound environmental justice implications. Lower-income communities and communities of color have historically been more exposed to environmental hazards. Research shows these communities often face disproportionate exposure to flood risk, wildfire risk, heat exposure, and air quality degradation.

When climate risk information is hidden from property markets, these disparities become entrenched. Wealthier communities (often more informed and better positioned to seek out climate data) can make informed decisions. Less affluent communities proceed without that information and end up bearing disproportionate climate impacts.

Conversely, transparent climate risk information can help equalize access to reliable property risk assessment. If climate data is freely available, all homebuyers have access regardless of wealth or education level. This doesn't automatically solve disparities (wealthier people can still outbid others for climate-safe properties), but it eliminates one layer of disadvantage.

Matouka's emphasis on using publicly available data is explicitly motivated by environmental justice concerns. Public data is free and available to everyone. Proprietary models require expensive subscriptions or sophisticated knowledge to access. By using California's public climate data, the plugin makes sophisticated climate risk assessment available to everyone without cost.

This gets at a fundamental question: should understanding your property's climate risk be a privilege available only to wealthy homebuyers with access to expensive private models, or should it be a public right available to everyone? Matouka comes down clearly on the latter side.

Estimated data shows that awareness of climate risks leads to significant property value adjustments. Properties impacted by Hurricane Sandy saw a 15% decrease, while wildfire awareness led to a 20% decrease.

Building Resilience Through Information Access

Climate adaptation requires information. Homeowners can't take protective measures if they don't understand what threats they face. Communities can't plan resilience investments without knowing which areas face greatest risk. Cities can't design infrastructure upgrades without understanding projected climate impacts.

Matouka's work is part of a broader shift toward using better information as a foundation for climate adaptation. In California, this has led to more detailed building codes in fire-risk zones, updated flood insurance requirements based on improved risk maps, and land use planning that accounts for climate impacts.

But this adaptation only works if information is widely accessible. If climate risk data is hidden by industry pressure, adaptation is delayed. Resources get invested reactively (after disasters) rather than proactively (before impacts materialize).

The research on disaster costs is sobering. Every dollar invested in pre-disaster mitigation saves approximately four dollars in disaster recovery costs. Yet most investment happens after disasters, not before. Better information can help shift that balance by highlighting risk before disaster strikes.

The Future of Real Estate Transparency

Matouka's plugin represents a prototype for what transparency in real estate could look like. But scaling this approach will require addressing several challenges.

First, it requires developing or accessing climate risk data at property level or small area level. California's public data infrastructure makes this possible in California but is exceptional nationally. Other states would need to invest in comparable public data infrastructure or develop standards for how private models get integrated into real estate platforms.

Second, it requires communicating climate risk in ways homebuyers can actually understand. Climate science is complex. Probabilistic risk is harder to communicate than simple categories. The research on risk communication suggests that visual displays and relative comparisons help people understand risk better than absolute numbers. Matouka's plugin attempts this through clear visual presentation, but design choices matter enormously for how information gets understood.

Third, it requires navigating the political economy of real estate markets. The California Regional Multiple Listing Service fought against transparency because transparency complicate transactions in high-risk areas. That same incentive structure exists everywhere. Any serious effort to expand transparency nationally will face industry opposition.

But there's also momentum toward transparency. More states are requiring climate risk disclosure in property transactions. More real estate platforms are voluntarily incorporating climate data. More homebuyers are demanding this information. The trend is clearly toward greater transparency even if progress is slower than climate advocates would prefer.

Matouka's work contributes to this shift by demonstrating that transparency is technically feasible, that it doesn't require waiting for regulators to mandate it, and that thoughtful approaches can present complex climate information in accessible ways.

Practical Steps for Homebuyers Today

Given that climate risk data isn't uniformly available through real estate platforms, homebuyers need to take initiative.

Start with public sources. FEMA's flood maps are available online for free. Most states maintain fire hazard severity zone maps. Climate and weather agencies publish heat exposure and air quality data. These public sources are free and worth checking.

Next, research historical events. Has the property flooded before? Has it been affected by wildfires? Talking to neighbors and reviewing historical news can reveal patterns not visible in current data.

Consider getting a private climate risk assessment. Companies like First Street provide detailed reports. These aren't free, but the cost is minimal compared to the property purchase and can reveal risks that public data misses.

Evaluate insurance carefully. Call insurance agents to get quotes for your specific property. Insurance cost should factor into your offered price. If insurance is unusually expensive or unavailable, that's a critical warning signal.

Think long-term. A property might be fine today but face serious risk in 20 years. Ask about climate projections, not just current conditions. Will the area face more frequent flooding? Severe heat? These aren't theoretical concerns; they affect long-term property value and livability.

Consider adaptation costs. Some risks are manageable with investment. Flood-prone properties can have sump pumps installed. Properties in fire-risk zones can be hardened. Properties facing heat exposure can have cooling systems upgraded. Factor adaptation costs into your purchase decision.

While Zillow removed climate risk data, other major platforms like Redfin, Homes.com, and Realtor.com continued to provide it, highlighting differing approaches to climate risk transparency.

The Role of Policy in Climate Risk Transparency

Real estate markets are heavily regulated. Disclosure requirements, lending standards, insurance regulations, and land use rules all shape how properties get bought and sold. Policy changes could mandate climate risk transparency relatively straightforwardly.

Some states are already moving this direction. California's new building standards incorporate climate resilience requirements. Some states are working toward requiring climate risk disclosure in property transactions. The Biden administration has encouraged mortgage lenders to incorporate climate risk into underwriting.

But there's genuine tension between different policy goals. Requiring transparent climate risk disclosure might reduce property values in high-risk areas, which could affect property tax revenue and community economics. Conversely, allowing climate risk to remain hidden perpetuates information asymmetry and delays adaptation investment.

The sustainable policy approach probably involves multiple elements: requiring climate risk disclosure, investing in public climate data infrastructure, updating building codes based on climate risk, and helping communities adapt to unavoidable climate impacts. Climate risk transparency is part of this suite of policies, not a standalone solution.

Matouka's work suggests that transparency doesn't require waiting for policy changes. Determined individuals and organizations can implement transparency independently using publicly available data and modern technology. But scaling this approach would benefit enormously from supportive policy.

Comparing Climate Risk Models: What Actually Works

There are now multiple commercial climate risk assessment platforms. Understanding how they differ helps evaluate their reliability.

First Street Foundation's models focus on property-level flood, wildfire, wind, and heat risk. They use detailed elevation data, infrastructure mapping, and historical outcomes to generate probabilistic risk estimates. Their approach is particularly strong for flood risk.

Jupiter Intelligence provides climate risk assessment integrated into broader environmental and sustainability platform. They focus on enterprise clients but their models are sophisticated and regularly validated.

Tru Value Labs uses satellite imagery and machine learning to assess property vulnerability to various climate hazards. Their approach is relatively new but shows promise.

Kara specializes in water risk, using hydrological modeling to assess flood and water scarcity risk. Their models are particularly detailed for properties near streams and rivers.

None of these models is perfect. All involve trade-offs between spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and computational feasibility. But they're collectively more sophisticated than FEMA's approach and worth considering as part of due diligence.

Matouka's plugin uses public data rather than proprietary models, which is a different approach entirely. The advantage is transparency and public availability. The potential disadvantage is that property-level modeling might be less detailed than sophisticated proprietary models.

What's at Stake: The Economic and Human Dimensions

Zillow's decision to remove climate risk data seemed like a minor platform change. But it symbolizes something much larger: the question of who controls information in markets that shape people's lives.

Property ownership is central to most people's financial security and wellbeing. For many families, their home represents the largest asset they'll ever own. A misinformed property purchase can have consequences that reverberate for decades.

Climate change makes this more consequential. A property that seemed safe when purchased might face serious risk within years. Families counting on home equity for retirement might find that asset eroded by climate impacts and resulting value depreciation.

This isn't abstract. A family that overpays for a property facing serious flood risk might face financial ruin if that risk materializes before they sell. A community concentrated in high-risk areas faces both economic impacts and potential displacement if climate impacts force residents to abandon properties.

Matouka's work recognizes this human dimension. By making climate risk data accessible to all homebuyers without cost, the plugin aims to prevent these outcomes by enabling informed decisions earlier.

The Carbon Emissions Calculation in Real Estate Decision-Making

One angle that deserves mention: climate risk assessment should influence not just where people live but how people evaluate the decision itself. Property location affects commute distances, which affects transportation emissions. Some climate-resilient properties are in dense urban areas where transit is available; others are in sprawling suburban areas requiring extensive driving.

Optimal climate adaptation involves not just moving to safer areas but also considering the carbon footprint of where you move. A home in a high-density area might face less physical climate risk than a home in sprawling exurbs, but the exurban option might require more driving.

This is complex to optimize. Individual homebuyers can't solve the coordination problem of urban development. But they can recognize that their property choice affects both climate risk exposure and carbon footprint.

Matouka's plugin focuses on climate hazard risk (flood, fire, heat) rather than carbon implications. But comprehensive climate-informed property decision-making would incorporate both.

Moving Forward: What Needs to Happen

Matouka's work is a genuinely important contribution, but it can't solve the problem alone. Scaling transparent climate risk assessment requires:

Public investment in climate data infrastructure. States need to fund high-resolution climate risk mapping. The research base exists; what's needed is operational funding to maintain and update maps, make data accessible, and ensure consistent methodology across regions.

Standards for how climate risk gets communicated. Different models produce different results. Without standards, homebuyers comparing properties across different platforms encounter inconsistent information. Standards don't require uniform models but should require transparent methodology and comparable communication approaches.

Regulatory requirements for disclosure. Some states could require climate risk disclosure in property transactions, similar to lead-based paint disclosure. This would create level playing fields where all properties face the same transparency requirements.

Integration into lending standards. Mortgage lenders could require climate risk assessment as part of underwriting. This would create market pressure for platforms like Zillow to display climate data since lenders would demand it for their decisions.

Education and outreach. Homebuyers need to understand climate risk and why it matters. Public education campaigns could help ensure that when climate information becomes available, people understand how to use it.

Matouka is actively working on many of these dimensions. He's engaged with policy discussions, collaborating with researchers, and iterating on the plugin based on user feedback. His work suggests that determined individuals can move this agenda forward even without waiting for large-scale policy changes.

Conclusion: Information as Climate Adaptation Infrastructure

Zillow's removal of climate risk data was a setback for transparency, but it wasn't the end of the story. Matouka's response demonstrates that alternatives exist. If major platforms won't provide transparency, determined individuals can build tools that do.

This might seem like a patchwork solution. One plugin for California properties isn't comprehensive. But it's exactly the kind of bottom-up innovation that often precedes broader policy change. Matouka's plugin shows that climate risk transparency is technically feasible, useful to homebuyers, and can be implemented using openly available data.

The larger argument Matouka makes is profound: climate risk information is too important to be left to corporate platforms responding to industry pressure. When information asymmetries prevent people from understanding risks that materially affect their lives and finances, that's a problem worth solving.

As climate change intensifies, property-level climate risk will become increasingly important. Homebuyers need to understand not just current market conditions but long-term livability and risk. Real estate platforms should provide that information. If they won't, individuals and communities should build alternatives.

Matouka's plugin is one version of that alternative. It demonstrates what transparency could look like. Whether California's approach becomes a model for national climate risk disclosure, or whether Zillow and other platforms voluntarily restore climate risk data, the trend is clearly toward greater transparency.

The question isn't whether climate risk information will eventually become standard in real estate transactions. It will. The question is whether that transition happens through informed consumer choice enabled by transparent data, or through costly experience as people gradually discover risks they should have known about upfront.

Matouka's work is actively pushing that transition in the right direction.

FAQ

What is climate risk in real estate?

Climate risk refers to the exposure of a property to climate-related hazards including flooding, wildfires, extreme heat, sea level rise, and severe weather. These risks affect property value, insurance cost, long-term livability, and investment returns. Climate risk assessment has become increasingly important as climate change intensifies weather extremes and alters regional climate patterns.

Why did Zillow remove climate risk scores?

Zillow removed its climate risk feature in November after the California Regional Multiple Listing Service questioned the accuracy of flood risk models provided by First Street Foundation. The MLS pressured the platform to remove the data, citing concerns about model accuracy. Zillow chose to comply rather than face conflicts with the real estate industry's database provider, prioritizing relationships with real estate professionals over consumer transparency.

How accurate are climate risk models compared to FEMA flood maps?

Modern climate risk models like First Street's are generally more accurate than FEMA flood maps for identifying actual flood hazard. Research shows FEMA maps miss approximately 20% of properties that actually experience flooding. However, both approaches involve trade-offs: FEMA maps are simple but potentially misleading, while modern models are more accurate but more complex. Neither should be treated as definitive; the best approach is comparing multiple data sources.

What is Neil Matouka's climate risk plugin and how does it work?

Matouka's plugin is a browser extension that automatically displays climate risk data when users view properties on Zillow in California. It pulls from publicly available state and federal datasets on wildfire risk, flood risk, sea level rise, and heat exposure, eliminating reliance on proprietary models. The plugin was developed by Matouka, who previously managed California's Fifth Climate Change Assessment, using transparent public data that's freely available to everyone.

How should homebuyers assess climate risk when purchasing property?

Homebuyers should consult multiple sources: FEMA flood maps, state fire hazard severity zone data, and private climate risk assessments like First Street. Researching historical events (previous flooding or fires) provides real-world context. Getting insurance quotes reveals what insurers think about the property's risk. For long-term decisions, reviewing climate projections rather than just current conditions is essential, as risk will likely increase over a 30-year mortgage.

Why does climate risk transparency matter for environmental justice?

Climate risk transparency has environmental justice implications because lower-income communities and communities of color have historically faced disproportionate exposure to climate hazards. When climate information is hidden, wealthier informed buyers can avoid risks while disadvantaged communities remain unaware. Public access to climate data (as Matouka's approach provides) helps level this information asymmetry, allowing all homebuyers to make informed decisions regardless of education level or wealth.

How does climate risk affect property values and insurance costs?

Research consistently shows that climate risk disclosure decreases property values by 5-20%, with larger discounts for properties in high-risk areas. Insurance costs are even more dramatic—properties facing serious climate risk often face insurance premiums exceeding 3-5% of property value annually. In extreme cases, insurance becomes unavailable at any price. These financial impacts underscore why climate risk assessment should influence purchase decisions.

What data sources does Matouka's plugin use and why publicly available data?

Matouka's plugin uses exclusively public data from California state agencies and federal sources, including wildfire hazard severity zones from the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, flood inundation mapping from state water agencies, and heat exposure analysis from California's climate research institutions. Matouka chose public data specifically for transparency, accessibility (it's free to everyone), and environmental justice considerations, avoiding expensive proprietary models available only to wealthy users.

How do First Street Foundation's models differ from FEMA's approach?

First Street uses machine learning, satellite imagery, detailed elevation data from LIDAR mapping, and climate change projections to generate property-level probabilistic risk estimates. FEMA's approach uses historical flood records to delineate 100-year floodplains through statistical analysis. First Street's methodology is more sophisticated and accounts for modern climate patterns, but it's more complex to communicate. FEMA's approach is simpler but increasingly inaccurate due to changing climate patterns.

Why are other real estate platforms continuing to display climate risk data while Zillow removed it?

Redfin, Homes.com, and Realtor.com have all continued displaying First Street climate risk data despite similar industry pressure. This suggests that different platforms prioritize different stakeholder relationships—some value consumer transparency more than industry approval. The divergence also reveals that complete transparency is achievable; it requires willingness to absorb friction with real estate professionals who prefer opacity around risks that complicate transactions.

Key Takeaways

- Zillow removed climate risk data after industry pressure, but competitors like Redfin continued displaying it, showing transparency is achievable

- Modern climate models are more accurate than FEMA flood maps but involve legitimate trade-offs between accuracy and simplicity

- Neil Matouka's browser plugin uses public California data to restore climate risk transparency, making sophisticated risk assessment free and accessible to all homebuyers

- Climate risk information affects property values (5-20% discounts), insurance costs (3-5% of property value annually), and long-term livability—making transparency crucial for informed decisions

- Information asymmetry in climate risk perpetuates environmental injustice; transparent public data helps level the playing field across income and education levels

Related Articles

- Casio G-Shock Metal Smartwatch: The Garmin Rival Fans Have Waited For [2025]

- LastPass Phishing Scam: How to Spot Fake Support Messages [2025]

- YouTube TV Custom Multiview and Channel Packages: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- NYT Games' Crossplay: The Ad-Free Word Game Disrupting Mobile Gaming [2025]

- Polar Loop Review: Screen-Free Fitness Tracker Analysis [2025]

- Instagram's AI Problem Isn't AI at All—It's the Algorithm [2025]

![Why Zillow Removed Climate Risk Scores and How Experts Are Fighting Back [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-zillow-removed-climate-risk-scores-and-how-experts-are-f/image-1-1769008280396.jpg)