Will Stancil and ICE Commuting in Minneapolis: When Activism Becomes Spectacle [2025]

There's a guy in Minneapolis driving around in a gray Honda Fit with his phone out, waiting for federal immigration agents to show up. His name is Will Stancil, and he's become one of the most polarizing figures in the city's immigration resistance movement.

The concept sounds simple enough: follow Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, record their interactions with community members, and post the footage online. What locals call "commuting" has become a lightning rod for debate about protest strategy, personal safety, media attention, and whether viral activism helps or hurts the people it claims to protect.

Here's the thing that makes this story worth paying attention to: Stancil isn't your typical activist. He's a former education researcher who spent years working on school desegregation issues. He's articulate, media-savvy, and completely unbothered by confrontation, whether that confrontation comes from federal agents with pepper spray or fellow activists through encrypted chat groups. Some people in Minneapolis see him as a necessary witness to ICE's most violent moments. Others think he's a reckless attention-seeker putting vulnerable people at greater risk.

The truth, as is often the case, is messier and more complicated than either side wants to admit.

TL; DR

- Will Stancil has become the face of "commuting": a practice where activists follow ICE agents to document arrests and alleged abuses in real-time

- The tactic has serious trade-offs: It creates a record of federal enforcement but potentially endangers undocumented immigrants and other community members

- Stancil's media engagement is intentional but controversial: He's given interviews to major outlets, which some fellow activists view as bad operational security

- The community is deeply divided: Local organizers disagree on whether video documentation helps or hurts the resistance effort

- The central tension is unresolved: How do you balance transparency and accountability with protecting vulnerable people from increased scrutiny?

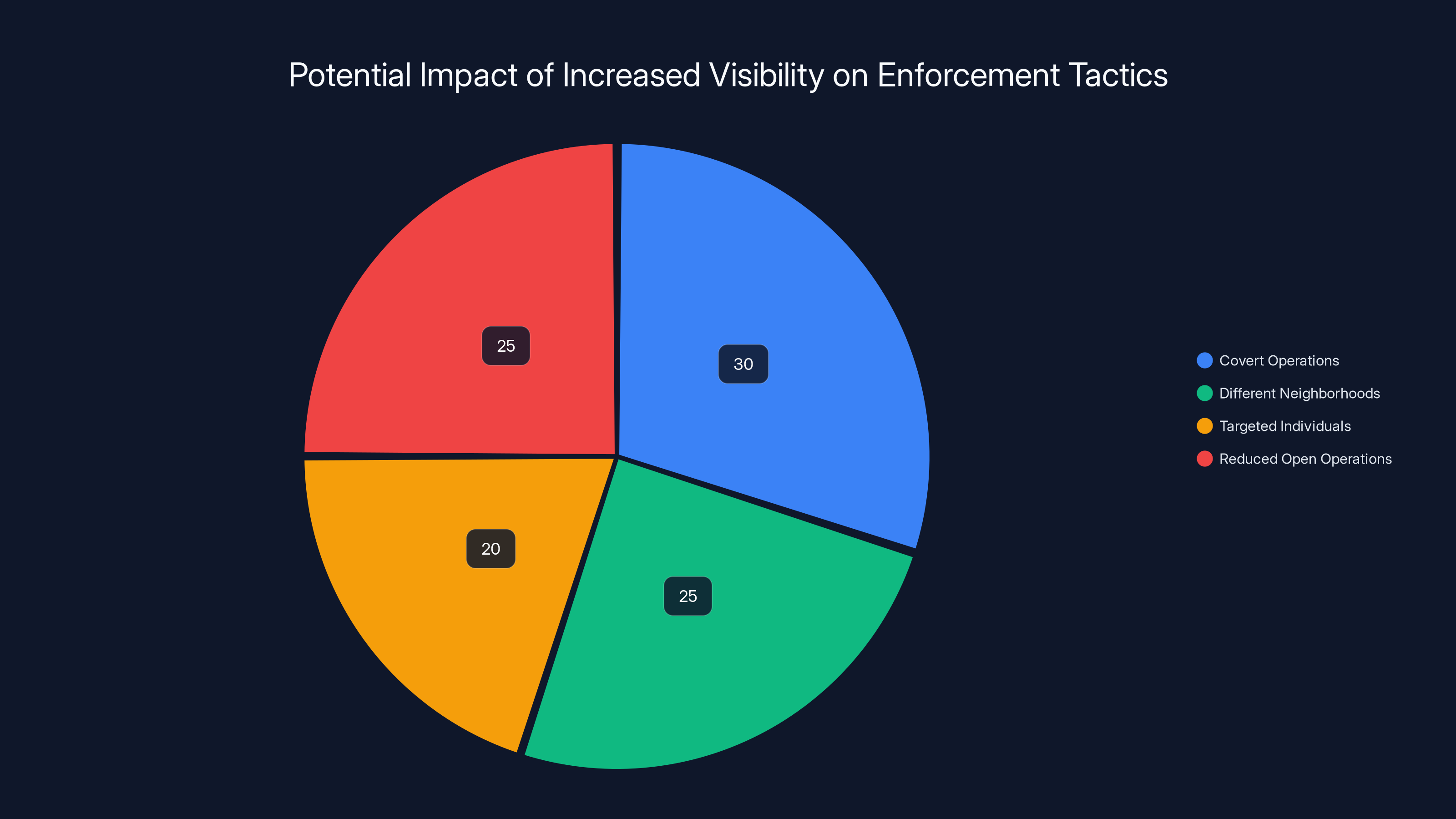

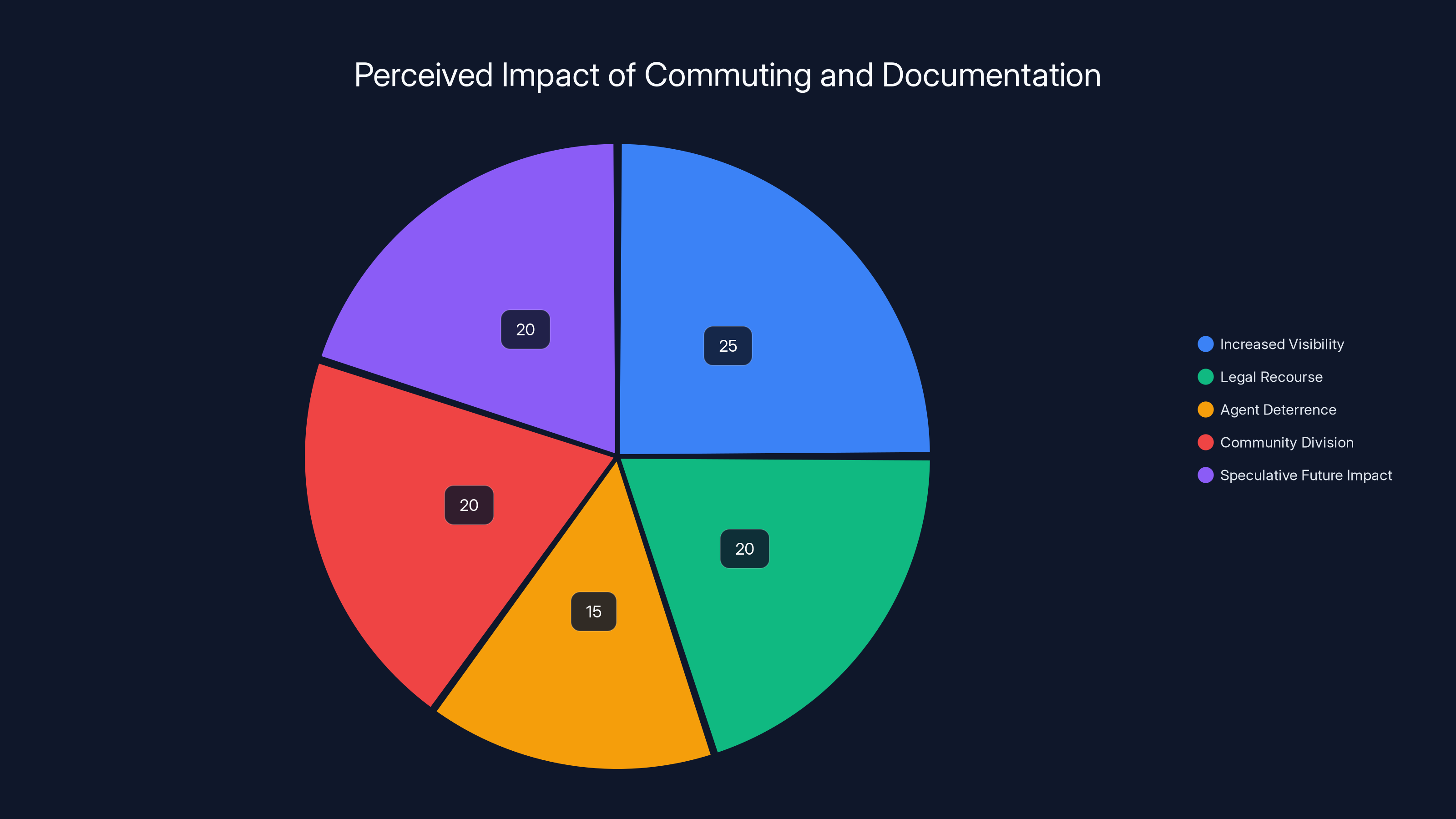

Increased visibility and documentation may lead to a shift in enforcement tactics, with a rise in covert operations and targeting of specific individuals. Estimated data.

Who Is Will Stancil and Why Does He Matter?

Will Stancil isn't an accidental activist. He's been organizing in Minneapolis for over a decade, mostly focused on education policy and school integration. If you're not paying attention to K-12 policy debates, you probably haven't heard of him. But within those circles, he had built a reputation as someone who doesn't back down from arguments, regardless of who's on the other side.

Then ICE intensified its operations in Minneapolis, and Stancil pivoted. He started showing up wherever federal agents were conducting raids. He brought his phone. He started recording. And he started talking to journalists.

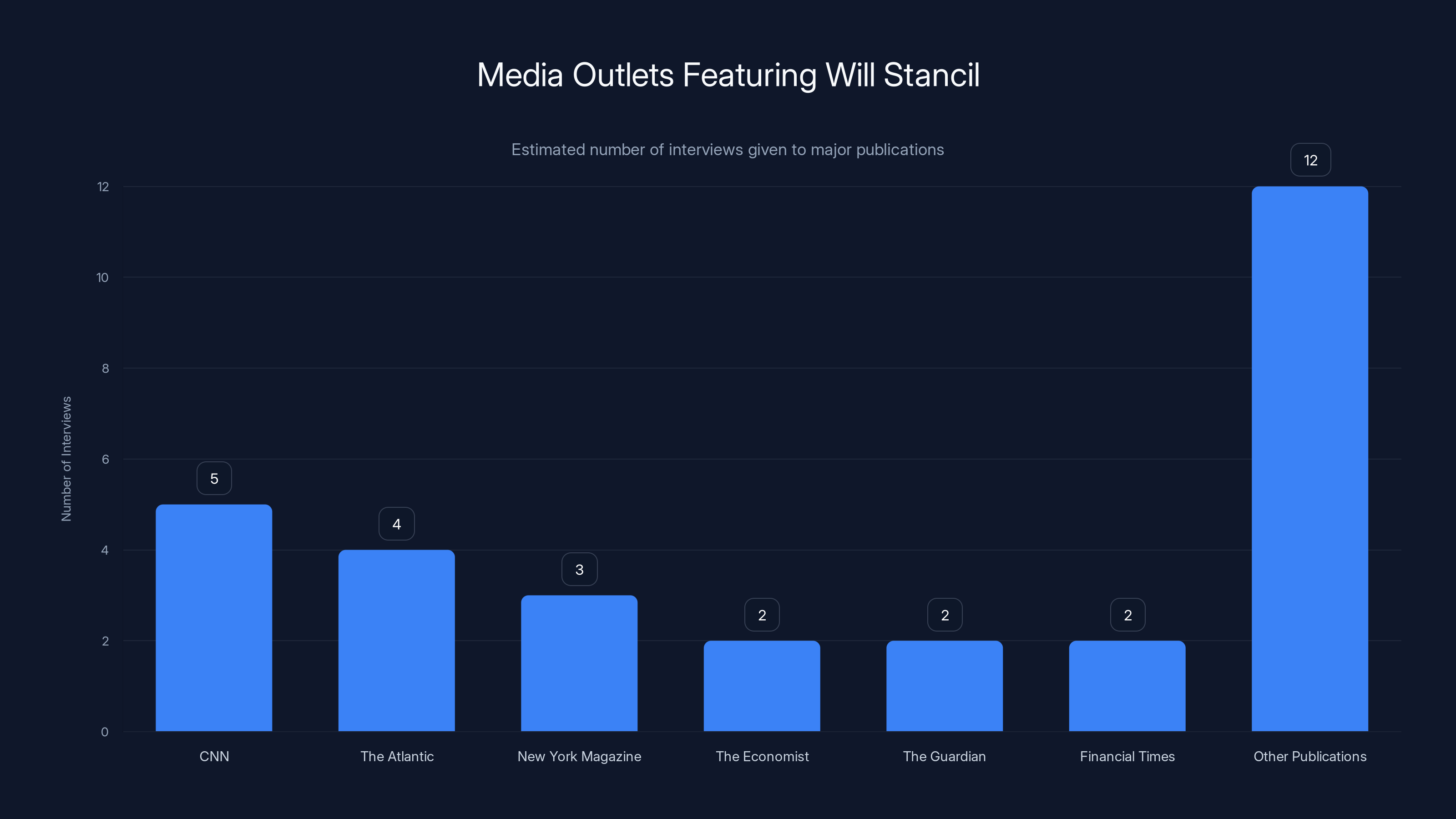

This is where things get complicated. Stancil is boyish-looking, articulate, and completely at ease in front of cameras. He's willing to be quoted. He's willing to explain his strategy. He's willing to let reporters tag along. When CNN wants a local activist to comment on ICE enforcement, he's available. When The Atlantic wants to profile the resistance movement, he'll sit for an interview.

For many journalists parachuting into Minneapolis to cover the immigration enforcement story, Stancil became the default source. He was accessible. He had good footage. He had coherent arguments about why witnessing federal overreach matters.

But accessibility isn't neutrality, and visibility isn't the same as effectiveness.

The Practice of "Commuting": What It Actually Means

Let's be clear about what commuting is and isn't.

It's not a coordinated militia operation. It's not an organized legal defense strategy. It's not even a formal tactic that emerged from years of activist strategy sessions. Commuting is what locals started calling the practice of following ICE agents around Minneapolis, usually on foot or in personal vehicles, to witness and document what happens.

The stated goal is accountability. When federal agents conduct arrests, especially in neighborhoods with large immigrant populations, there are often no witnesses. Families don't know where people are being taken. There's no real-time record of what happened. Commuting attempts to create that record.

You follow the agents. You keep your phone camera running. You stay at a safe distance. You record the arrest, the language used, the force applied. Then you post it online. The idea is simple: if everything is being filmed, maybe agents will hesitate before using excessive force.

Does it work? That's the central question dividing Minneapolis's activist community right now.

Stancil himself has been tear-gassed multiple times. He's taken pepper spray directly to the face. He's been yelled at, threatened, and physically confronted by federal agents who presumably do not appreciate being filmed. In one incident, he was arrested and charged with obstructing federal agents. He's become, in some ways, the human embodiment of the commuting practice.

Will Stancil has been featured in numerous major publications, with an estimated total of over 30 interviews, highlighting his prominence in the Minneapolis resistance movement. (Estimated data)

The Arguments in Stancil's Favor: Creating an Undeniable Record

Let's start with the strongest case for what Stancil is doing, because it's genuinely compelling.

Federal enforcement happens in the shadows. Most ICE operations occur in neighborhoods where many people don't speak English as a first language, where people are afraid of authorities for documented reasons, and where the power imbalance is completely one-sided. An agent with a gun and legal authority versus someone who might not have status, who definitely doesn't have legal representation, who is terrified.

When there's no witness, the story is simple: the agent says what happened, the person being arrested either can't contest it or won't contest it because they're afraid. There's no record. There's no accountability.

Commuting changes that. When someone is filming, suddenly there's a record that can be shared with families, lawyers, and the public. The narrative can't be controlled entirely by the people with power.

Stancil has documented situations where ICE agents have been aggressive in ways that might have gone unnoticed otherwise. He's also used his footage as raw material for other organizers to work with. He's given lawyers actual video evidence to work from.

Furthermore, if you believe that ICE operations depend on speed, surprise, and minimal oversight, then having people in the neighborhood who know to show up when raids are happening could theoretically increase the pressure on federal agents to justify their actions.

There's also a moral argument here: someone needs to be watching. Someone needs to refuse to look away. Stancil has positioned himself as willing to do that, consequences be damned.

This isn't nothing. This matters. The question is whether it matters enough to justify the rest of it.

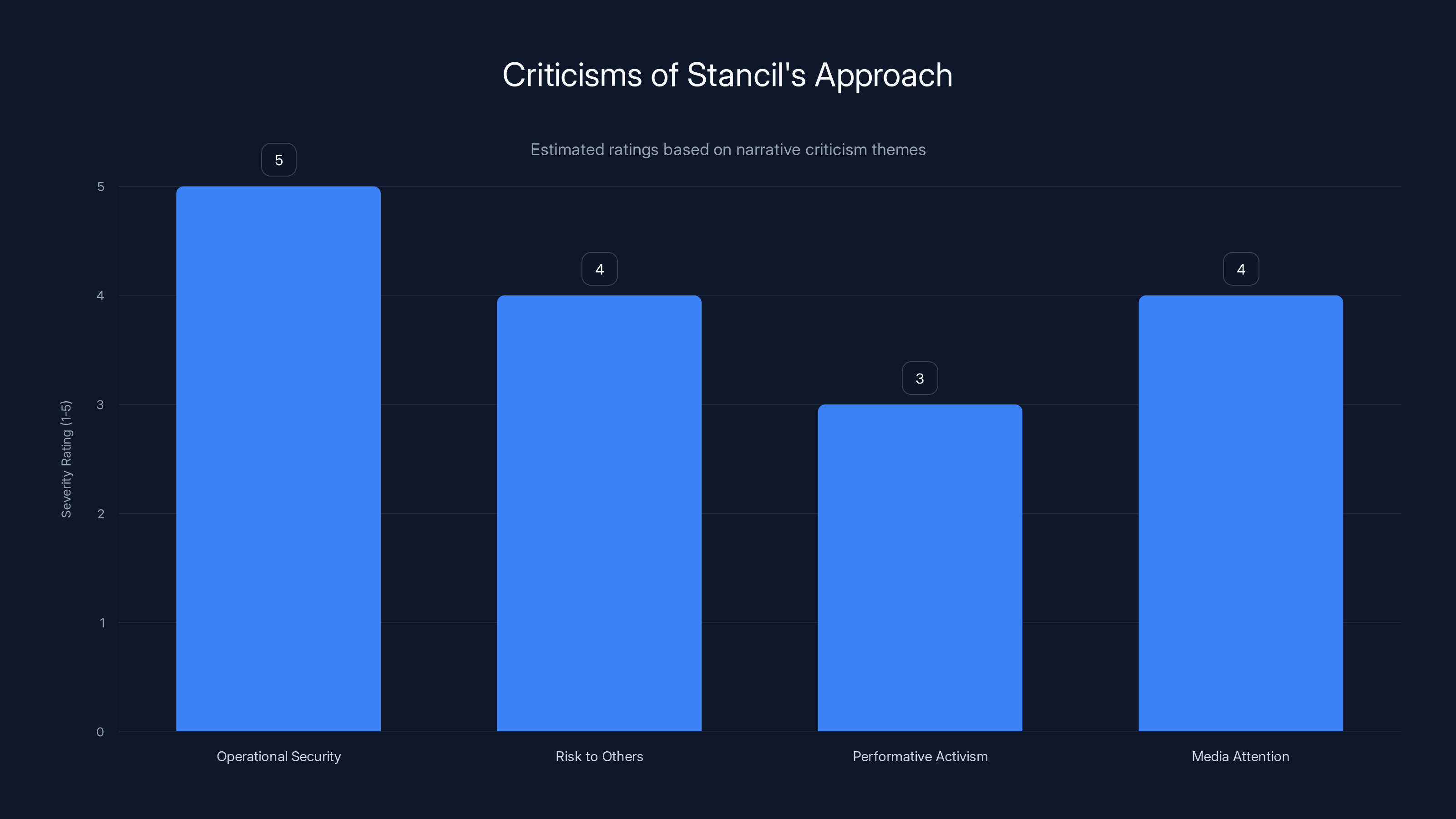

The Arguments Against Stancil: OPSEC, Risk, and Performative Activism

Now let's look at the strongest criticism, which comes primarily from other people doing similar work in Minneapolis.

The first criticism is straightforward: Stancil is bad at operational security, and that endangers other people.

When you talk to reporters about what you're doing, when you document your activities and post them online, when you make yourself a public figure, you become trackable. Federal agents can see your face. They can learn your patterns. They can build a case against you if they want to. That's a personal choice—many would say it's a brave choice.

But when you talk to reporters about the network of people around you, when you discuss other people's activities in interviews, when you create a public record of how the commuting network operates, you're not just risking yourself. You're potentially compromising everyone else.

This is why Stancil got kicked out of the Uptown Signal chat. The moderators weren't being opaque or unfair—they were following a clear operational security principle: no press. Ever. The reason isn't paranoia. It's that the more journalists know about what you're doing, the more vulnerable you become.

Stancil's position was that this was overly secretive and that the tactics only work because there are "so many people doing it" that authorities can't shut it down. The moderators' position was that secrecy is the entire point, and that Stancil was being reckless with other people's safety.

The second criticism is about attention and incentives. Some critics worry that Stancil is drawn to commuting partly because it's a way to stay relevant, to maintain a media profile, potentially to build a platform that could help him in future political runs. Stancil ran for State House in 2024 and lost. After a loss like that, building a media presence around activism could be instrumentally useful.

Stancil denies this explicitly. "I'm not saying, 'Look at me!' It's really not about that," he told the journalist who interviewed him. But incentives are complicated. You can genuinely believe you're doing something important and also genuinely enjoy the attention and platform it brings. Those things aren't mutually exclusive.

The third criticism is about effectiveness. Some experienced organizers in Minneapolis think that Stancil's approach—visible, recorded, media-friendly—actually makes things worse for vulnerable people.

Here's the logic: if you're documenting every raid in real-time and posting it online, federal agents know they're being filmed. That might make them slightly more cautious in some ways, but it also means they're prepared for the documentation. It means they can adjust their tactics based on what they've seen before. It means they know exactly where to expect resistance.

Meanwhile, people in the community are now aware that ICE is active in their neighborhood, which could either help them (they can be more careful) or hurt them (agents know where to expect people to be watching, which means they adjust their operations).

Some organizers think the real work is quieter, less visible stuff: working with immigration lawyers, building defense networks, creating legal funds, helping people with paperwork. The work that helps actual people instead of building a media narrative.

The Role of Media Attention: Blessing or Curse?

Here's something you need to understand about contemporary activism: media attention is simultaneously essential and poisonous.

It's essential because without it, powerful institutions can do terrible things in complete obscurity. The public doesn't know. The press doesn't care. The government operates without any external pressure or scrutiny.

It's poisonous because attention makes you vulnerable. It makes you a target. It changes how others perceive you. It creates incentives that weren't there before.

Stancil has attracted a lot of media attention. Major publications want to talk to him. He's become the public face of commuting in Minneapolis. That's a position of significant influence and significant vulnerability.

When journalists ask him to explain the tactic, he does. He explains it clearly, coherently, in ways that make it understandable. This is good for public understanding of what's happening in Minneapolis. It's bad for operational security, because he's now explained the tactic to the entire internet, including federal agents who are presumably reading the same articles.

When he gets tear-gassed and posts about it, the story goes viral. That raises awareness about ICE tactics and violence. It also creates a narrative where Stancil is the main character, which some worry shifts attention away from the actual targets of ICE enforcement—the immigrants whose lives are being disrupted.

There's also something subtly problematic about media narratives around activism. Journalists often look for individual heroes because individual heroes make better stories. "Activist Movement Has Complex Strategy That Requires Decentralized Coordination" doesn't make for a compelling article. "One Man Keeps Getting Tear-Gassed to Expose Federal Abuse" does.

So when Stancil exists as an extremely media-accessible, extremely camera-friendly activist who's willing to explain everything and get arrested doing it, media outlets naturally gravitate toward him. This isn't intentional manipulation on either side, but it does shape the narrative in ways that might not reflect the actual views or strategies of the broader movement.

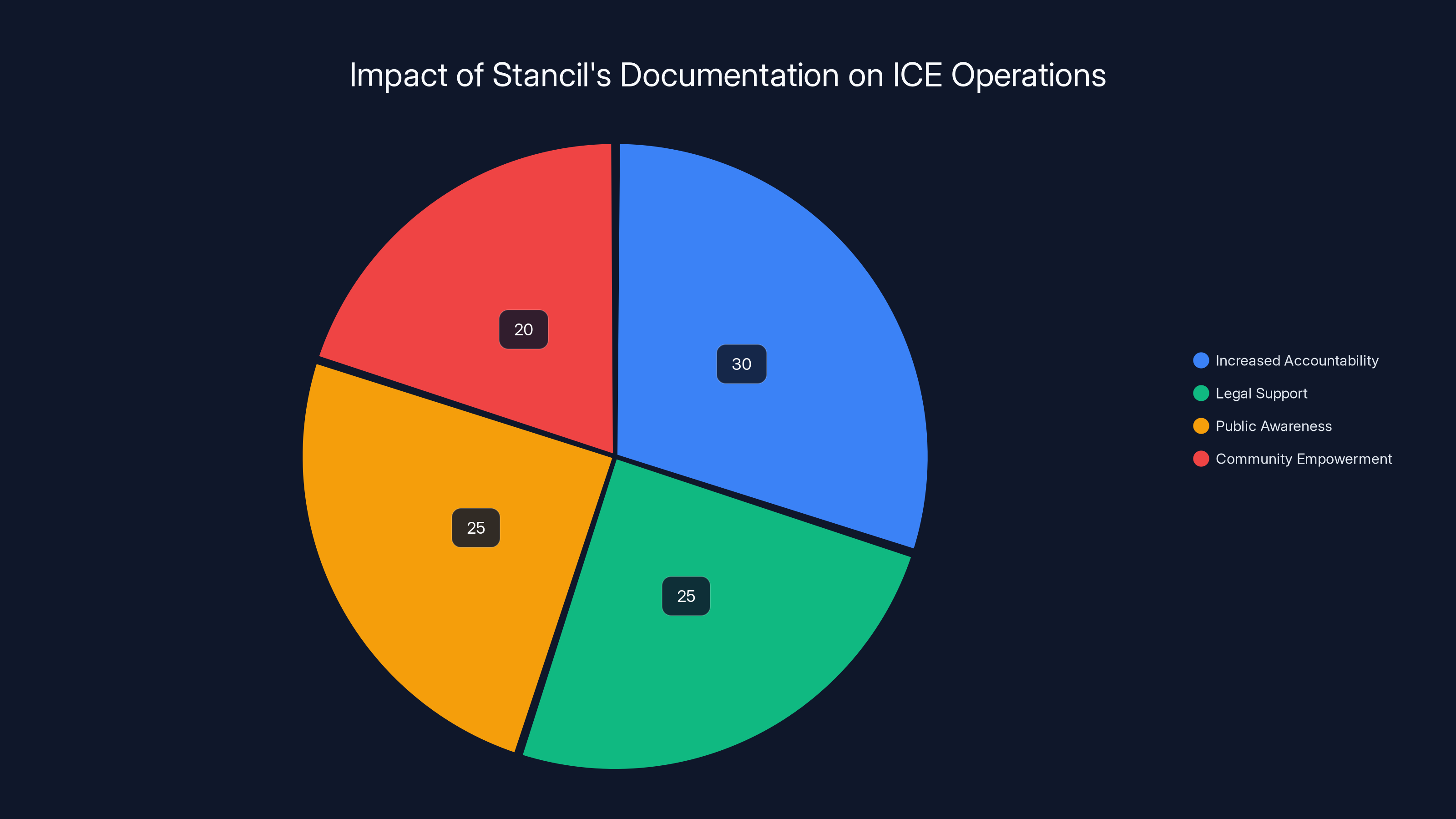

Stancil's documentation efforts are estimated to increase accountability (30%), provide legal support (25%), raise public awareness (25%), and empower communities (20%). Estimated data.

The Signal Chat Conflict: When Your Own Community Rejects You

So Stancil got kicked out of the Signal chat. This seems like a small thing, but it's actually the moment that crystallized all the tensions.

A Signal chat is private, encrypted, and relatively small. It's where people coordinating actual commuting activities talk about logistics, share information, and plan actions. It's where the real coordination happens.

Stancil was in this chat. Then he got booted. The official reason: he talked to press about being in the chat, he publicized that he was getting kicked out, and in doing so he violated the implicit understanding that what happens in the chat stays in the chat.

Stancil's response was to ask for an appeal. The moderators basically gave him a shrug emoji.

This frustrated him intensely. He saw it as unjust opacity. He saw people he saw as allies suddenly treating him like an outsider. He couldn't understand why the rules hadn't been clearly communicated beforehand, why the enforcement felt arbitrary, why the moderators wouldn't even have a conversation about it.

But here's the thing: from the moderators' perspective, the rules were obvious. Everyone in that chat knew that operational security required no media access. Everyone knew that meant not talking to press about the chat or about what happened in it. Stancil either didn't know or didn't care, and then when he got called out, he made it worse by publicizing the conflict.

This is the kind of conflict that emerges when you have fundamentally different strategies and assumptions about what activism should look like.

Stancil's model: transparency, media engagement, making everything as visible as possible so that power has nowhere to hide.

The moderators' model: operational security, limited visibility, protecting the identity and safety of everyone involved by keeping activities quiet and contained.

Neither model is obviously wrong. But they're incompatible. You can't have a single network operate simultaneously on both principles. At some point, you have to choose: are we building something that's visible and media-friendly, or something that's hidden and secure?

The chat moderators chose. Stancil was out.

Documented Violence: What the Footage Actually Shows

We should probably talk about what Stancil has actually recorded, because it's not just random footage of routine stops.

He's documented situations where ICE agents used force that looks, by reasonable standards, excessive. He's recorded agents pepper-spraying people in residential neighborhoods. He's gotten tear gas in his own face. He's documented the moment someone gets loaded into a vehicle, sometimes with physical force applied.

This footage has been valuable. Immigration lawyers have used it in cases. Families have used it to understand what happened to their loved ones. Advocacy organizations have used it to make arguments about federal overreach.

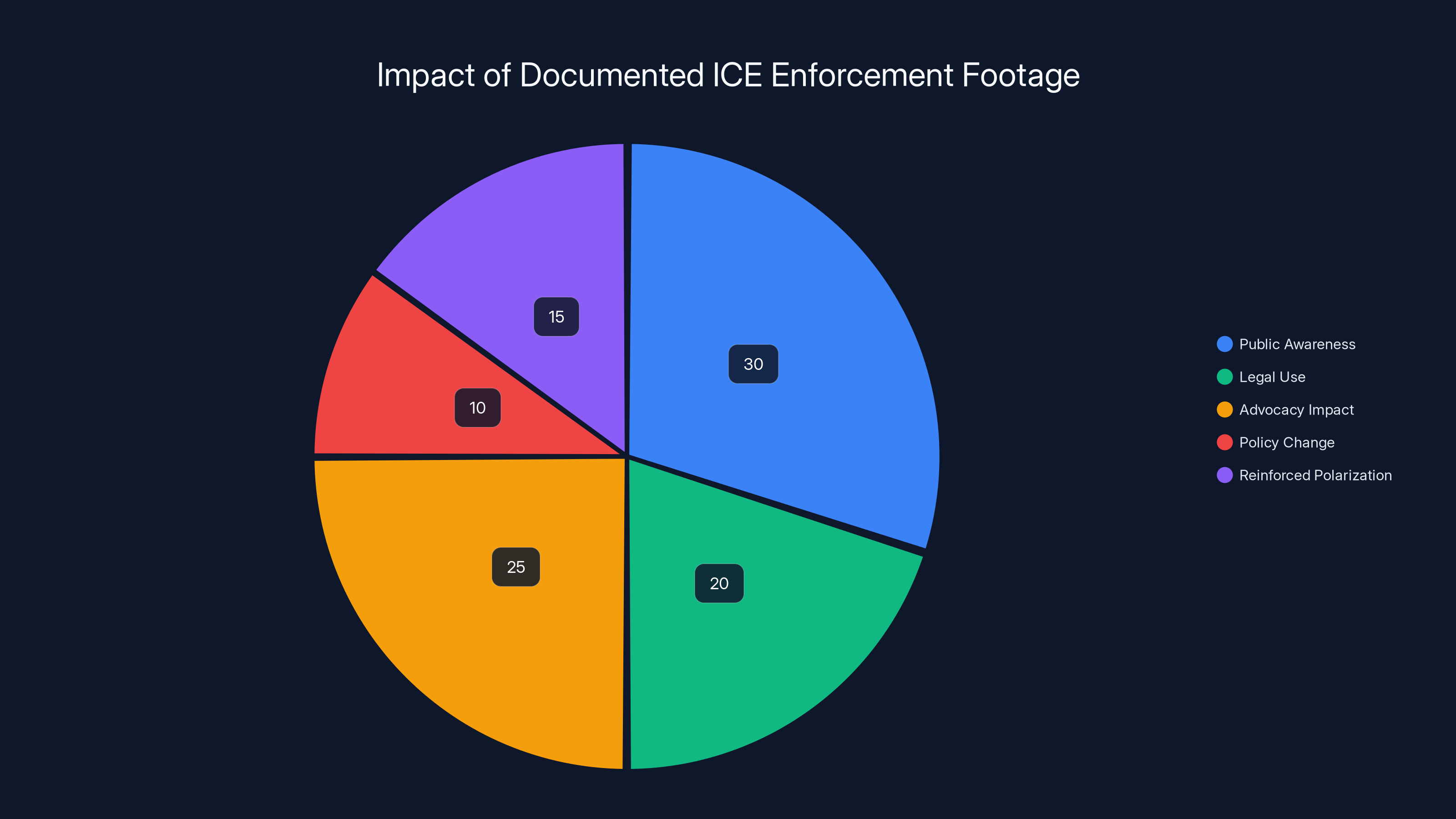

The question is: does having this footage change anything structurally?

ICE continues operating. Federal enforcement continues. People continue being arrested and detained. The footage creates a record, but does it actually stop abuses or just document them?

This is where Stancil's implicit theory of change emerges. He seems to believe that if you can make federal overreach visible enough, undeniable enough, widely-shared enough, then public pressure will force policy change. If people see what ICE is doing, they'll demand that their representatives do something about it.

There's historical precedent for this working. Civil rights era footage of police violence helped mobilize public opinion and pressure for change. Documenting state overreach can matter.

But context matters too. We live in a moment of significant political polarization where a lot of people see ICE enforcement as appropriate federal action, not overreach. The same footage that horrifies one group might confirm the views of another group. So the question becomes: does documentation change minds, or does it just reinforce existing polarization?

Stancil seems to assume the former. The moderators who kicked him out seem to assume the latter, or that the documentation risk simply outweighs any benefit.

The Broader Activist Ecosystem in Minneapolis

Here's something important: Stancil isn't the only person doing this work, and he's not the only activist in Minneapolis working on immigration issues.

There are organizations doing legal work. There are people coordinating rapid response networks. There are folks managing community funds to help people with bail and legal costs. There are people doing direct community care—helping families understand their rights, their options, what to do if a family member gets detained.

Most of this work is not visible. Most of it doesn't have media coverage. Most of the people doing it aren't getting interviews in major publications.

Stancil's visibility creates a subtle problem: he becomes the narrative. People think about immigration activism in Minneapolis and they think about Stancil and commuting. They don't think about the less visible work that's also happening.

This might distort how resources flow, where attention goes, what people outside Minneapolis think activism in the city looks like.

It's not necessarily Stancil's fault. He didn't ask to be the main character. But in existing as the main character, visible and accessible and continuously getting tear-gassed, he inevitably shapes how others perceive the entire movement.

Operational security is the most severe criticism against Stancil, highlighting potential risks to others. (Estimated data)

Personal Motivations and Honest Assessment

Let's just get real for a moment.

Stancil is human. He has incentives. He runs for office. He cares about his reputation. He enjoys media attention (most people do, even if they say they don't). He likes being right in arguments. He likes confrontation.

None of this means he's not sincere. None of this means the work doesn't matter. But it means we should be honest about what's motivating him.

If someone does activist work and that work makes them more visible and more influential, and then they do more of that same work, we should probably ask whether the work is driving the visibility or whether the visibility is driving the work.

Stancil's answer would presumably be: both are happening, and that's fine. The work matters, and the visibility helps amplify the message, so it's a good thing.

The moderators' answer would presumably be: the visibility is actually making the work harder and more dangerous, so the visibility is a net negative no matter what his intentions are.

Both assessments have some validity. But you can't hold them simultaneously. At some point, you have to acknowledge that these are contradictory and that you're not sure which one is right.

Here's what we know for certain: Stancil is doing work that has some documented effects (footage that's been used in legal cases) and some unknown effects (whether the visibility helps or hurts long-term movement goals). The people doing the same work as him are divided about whether he's helping or hurting. And he himself seems convinced that he's helping while being unwilling to acknowledge that the attention and visibility he's attracted might not be entirely separated from his genuine belief in the work's importance.

The Question of Physical Safety and Risk Distribution

Here's a practical concern that's worth taking seriously.

When Stancil gets tear-gassed, he knows it's coming. He's chosen to put himself in that situation. He's made a decision about his own risk tolerance.

But when federal agents know that someone is always watching and documenting, they might change their tactics. They might go to different neighborhoods. They might operate at different times. They might target specific people to avoid being documented.

If that happens, then other people—people who didn't sign up for commuting, people who weren't aware ICE was in their neighborhood, people who just wanted to not get arrested—might face increased risk.

It's a hypothetical, but it's a plausible one. If your tactic makes you visible and makes it harder for agents to operate openly in certain neighborhoods, agents might respond by operating more covertly in different neighborhoods, or in ways that are harder to document.

From the commuters' perspective, they're creating a visible presence that might deter enforcement. From the perspective of people not involved in commuting, that same visible presence might just shift where enforcement happens, putting them at greater risk.

Stancil would probably argue that increased documentation and visibility across the entire city would be better. But that requires scaling the commuting tactic in ways that might not be possible.

This is where the operational security concerns connect to physical safety concerns. The people worried about OPSEC aren't just worried about getting arrested. They're worried about creating a tactic that attracts federal attention and makes things harder for everyone else.

Legal Consequences and the Cost of Confrontation

Stancil has been arrested. He's been charged with obstructing federal officers. He's facing potential legal consequences for his activism.

That's brave. It's also something he can afford to do in ways that many other people cannot.

If you have legal resources, if you have a support network that can help with bail and legal fees, if you have some insulation from the absolute worst consequences of federal legal action, then getting arrested becomes a tactic you can use.

But if you don't have those resources, if you're undocumented or partially documented, if getting arrested creates massive complications for your life, then the tactic is much riskier.

This is another way that Stancil's approach might be creating unequal risk distribution. The most visible person advocating for confrontation is also the person most able to withstand the legal consequences of confrontation.

That doesn't mean he shouldn't do it. But it's worth acknowledging that his ability to take this risk isn't available to everyone.

Estimated data shows that increased visibility and legal recourse are perceived as the most significant impacts of documentation efforts, each accounting for 20-25% of perceived impact.

The Role of Social Media in Shaping Perception

Stancil posts about his activities on social media. The posts get shared. They go viral. People see him getting tear-gassed and feel angry about it. They feel like they're witnessing something they should care about.

This is powerful. This is how social movements spread in the 21st century.

But it also means that the actual tactic (following ICE agents, documenting arrests) gets collapsed into the persona (Stancil, the courageous activist, the guy getting tear-gassed).

The tactic itself might be just one piece of a larger strategy. But in the social media narrative, it becomes the core of the story because the story is focused on a person, not on systems or strategies.

This is partly why the moderators were concerned about Stancil's media engagement. The more he talks to press, the more the tactic gets associated with his persona, the more it becomes about him personally rather than about the broader movement.

Comparing Approaches: Visible vs. Invisible Activism

Let's be clear about the different models that are present in Minneapolis's activism scene.

Model 1: Visible, Media-Friendly Activism You make everything as public as possible. You talk to journalists. You document everything. You build a narrative that the public can understand and engage with. The theory of change is that public pressure, once informed by your documentation and explanation, will force policy change.

Model 2: Invisible, Security-Focused Activism You stay hidden. You limit who knows what you're doing. You build networks that are strong internally but invisible externally. The theory of change is that the actual work—legal defense, mutual aid, rapid response—is what matters, not the narrative about it.

Both models have worked in different contexts. Civil rights activists needed visibility to build public pressure. Underground railroad organizers needed invisibility to protect enslaved people.

The question in Minneapolis is: which model makes sense for the current moment?

Stancil is clearly team visibility. He believes that ICE depends on operating in shadows, and that light is the best disinfectant.

The moderators are clearly team invisibility. They believe that the work is too vulnerable, too dependent on operational security, to survive media scrutiny.

They can't both be right. Or rather, they can both be right about the advantages of their respective models, but they can't both operate in the same organization using the same tactic without creating exactly the conflict that happened.

The Legitimacy Question: Who Gets to Define the Movement?

Here's something that's underneath all of this.

When Stancil got kicked out of the Signal chat, he wasn't just kicked out of a chat. He was rejected by people who were doing the same work he was doing. He was told that his approach didn't align with the movement's values.

But whose movement is it? Who gets to define what the "right" way to do this work is?

Stancil would probably argue that commuting has value regardless of whether the Signal chat moderators approve. He's attracting attention, documenting abuses, creating a record. The work stands on its own merits.

The moderators would probably argue that if you're not willing to follow the basic security principles the movement has agreed on, then you're not really part of the movement anymore. You're doing your own thing.

Both are right. Stancil can do his own thing. The movement can exclude him. These things are both true simultaneously.

But there's an asymmetry here. Stancil is more visible, more media-accessible, more likely to be quoted in national publications. So when people think about Minneapolis immigration activism, they think about him. When national outlets want someone to explain what's happening, he's the person they call.

So even though the movement kicked him out, he might still be the most visible representative of the movement. That's a weird position to be in.

Estimated data suggests that while documented footage raises public awareness and aids legal and advocacy efforts, its impact on policy change is limited, with some reinforcement of existing polarization.

What Has Changed Since Stancil Started Commuting?

Let's zoom out and ask the basic question: has this tactic actually accomplished anything?

This is hard to measure. How do you quantify the impact of documentation? How do you know whether things would have been better or worse without it?

What we know:

- ICE continues operating in Minneapolis

- People continue being arrested and detained

- Federal enforcement continues

- The visibility around this enforcement has increased

- Some immigrants and their families have legal recourse through footage

- Some federal agents have presumably been somewhat deterred by the presence of cameras

- The activist community in Minneapolis is divided about whether this is helping

That's not nothing. But it's also not a fundamental change in how enforcement operates.

Maybe the real impact is something quieter: individual families helped by documentation, individual legal cases won with footage, individual agents slightly more cautious because they know they might be recorded. Those things matter, even if they don't show up in systemic change.

Or maybe the real impact is in the future: as more people do this work, as documentation becomes ubiquitous, as it becomes impossible for federal agents to operate without being recorded, the calculation might change. But that's speculative.

The Broader Context: Federal Enforcement and Resistance

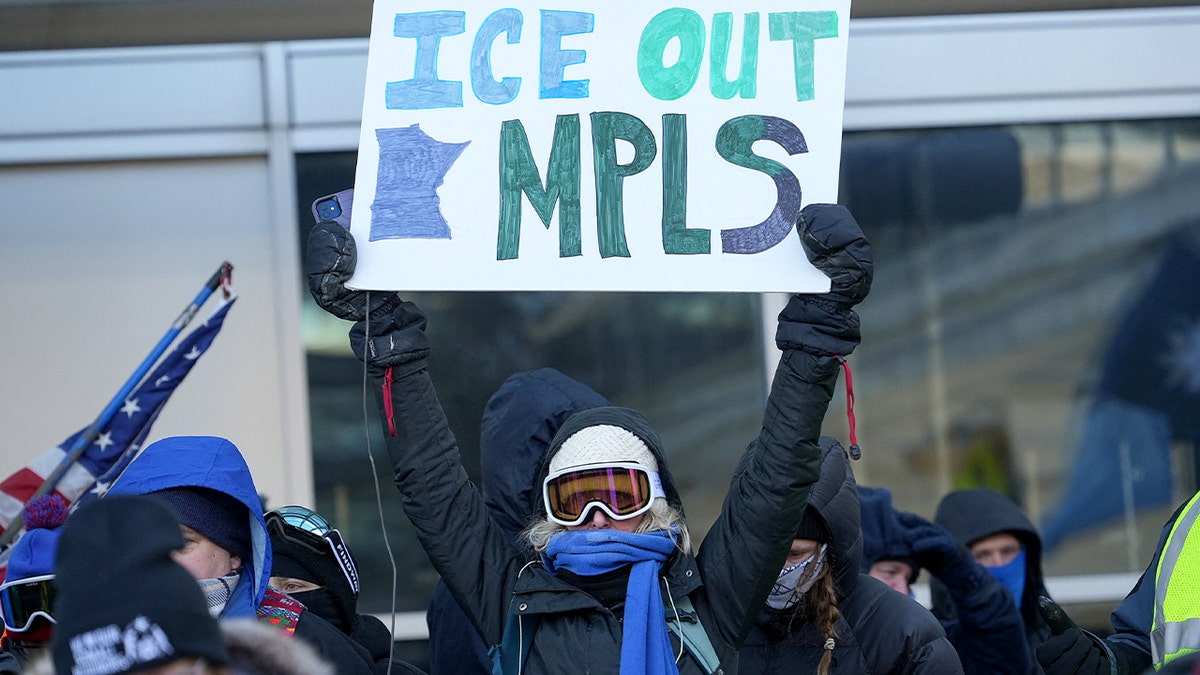

Stancil's commuting doesn't exist in a vacuum. It exists in a specific moment where federal immigration enforcement has intensified, where some people in Minneapolis decided they needed to do something visible and direct, and where the question of how to resist federal power is very real.

The Trump administration has made immigration enforcement a priority. ICE has increased operations. People who've been in the country for decades without incidents are suddenly facing deportation.

In that context, Stancil's decision to show up and document and bear witness makes some sense. Someone needs to say: this is happening. Someone needs to create a record that this happened.

But that same context also explains why some organizers are cautious. If federal enforcement is intensifying, the last thing you want is to attract more federal attention. You want to stay hidden, keep your networks protected, do the work that actually helps people without drawing scrutiny.

So the conflict between Stancil and the moderators isn't really about him as a person. It's about fundamental disagreements about how to respond to federal power in an intensified moment.

Complicating the Narrative: What the Critics Might Be Missing

Okay, I've laid out the case against Stancil pretty thoroughly. Let me try to complicate it a bit.

First, the safety concern cuts both ways. Yes, visibility might put some people at risk. But invisibility also puts people at risk—it means abuses can happen without consequence, it means there's no deterrent against the worst federal behavior. Which approach actually creates more safety long-term is genuinely unclear.

Second, the criticism about Stancil's attention-seeking might be unfair. It's possible to genuinely believe in the work and also benefit from the attention. Those things aren't contradictory. Lots of people do important work that happens to also benefit them. That's just human.

Third, the OPSEC critique assumes that federal agents couldn't figure out what's happening anyway. But ICE is probably smarter than activists think. They're probably paying attention to movements, networks, tactics. The idea that Stancil's media presence is fundamentally compromising something that would otherwise be secret might overestimate how much secrecy was ever possible.

Fourth, commuting might actually be more of a grassroots tactic than the critics acknowledge. It's not something Stancil invented. It's something that people organically started doing. He just happened to be the most visible person doing it. That's different from him imposing a tactic on the movement.

These counterarguments don't resolve the conflict. But they suggest that the situation is more complicated than a simple narrative of reckless activist vs. responsible organizers.

The Future of Commuting in Minneapolis

What happens next? That's genuinely unclear.

Stancil could stop. He could get arrested and decide it's not worth it. He could move on to other work. The visibility could decrease.

Or commuting could become a more established tactic, more people could get involved, it could become an expected part of how Minneapolis responds to ICE. The practice could normalize and scale.

Or there could be some middle ground where people stop fighting about it and just accept that different people are using different tactics, some visible and some invisible, and that's fine.

The moderators kicked Stancil out, but they didn't stop commuting. Other people are still doing it. The tactic persists even without the most visible practitioner.

What will matter going forward is whether commuting actually helps people. Does it prevent arrests? Does it reduce violence? Does it give immigrants more power in their interactions with federal agents? Does it create legal consequences for agents who abuse their power?

Or does it mostly just create documentation and spectacle while structural enforcement continues unchanged?

The answer probably involves some of both. But the balance matters for assessing whether this is a worthwhile tactic.

Reflections on What This Conflict Reveals

When you step back from the specific conflict in Minneapolis, you see something bigger.

You see the fundamental tension between transparency and security that exists in all movements. You see the difficulty of coordinating people with different values and different risk tolerances. You see how media attention shapes movements in ways that aren't always positive. You see how individual activists become the face of movements even when the movements might wish they weren't.

You also see something about contemporary activism more broadly: we're figuring out how to resist power in a moment where everything is filmed, everything is documented, everything becomes content.

There's no clear answer about whether that's good or bad. It's both. It creates accountability, but it also creates new vulnerabilities. It amplifies movements, but it also distorts them.

Stancil is, in some ways, a product of this moment. He's a person who's comfortable being visible, being recorded, being a character in a story. The moderators are also a product of this moment, people who are skeptical of visibility, who understand the risks of documentation, who want to work in ways that feel more traditional and more secure.

Both instincts make sense. The tragedy is that they can't both operate in the same organization.

FAQ

What is "commuting" in the context of immigration activism?

Commuting is a tactic where activists follow Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents to document arrests, alleged abuses, and use of force in real-time. Activists film these interactions and post the footage online with the goal of creating a public record of federal enforcement and potentially deterring excessive force through visibility.

Who is Will Stancil and what made him prominent in Minneapolis activism?

Will Stancil is an education researcher who became one of the most visible activists engaged in commuting against ICE operations in Minneapolis. He gained prominence through his willingness to be publicly associated with the tactic, engage with media outlets, and document his confrontations with federal agents, sometimes resulting in injuries from pepper spray or tear gas.

Why did the activist community in Minneapolis get divided over Stancil's approach?

The division stems from disagreements about operational security, media engagement, and effectiveness. While some activists view Stancil's documentation as valuable for accountability, others believe his media engagement compromises the safety of the broader activist network and that the tactic's visibility doesn't justify the risks it creates for undocumented immigrants and other vulnerable community members.

What are the operational security concerns about commuting and media visibility?

Activists concerned about operational security worry that publicly discussing commuting tactics, explaining them to journalists, and making the tactic visible to federal agents allows those agents to prepare for and counter the tactic. They also fear that detailed media coverage could be used to identify participants and potentially target them for prosecution or surveillance.

Has commuting actually changed how ICE operates in Minneapolis?

The tactic's measurable impact remains unclear. While commuting has produced documentation used in some legal cases and potentially made agents more cautious in specific instances, structural federal enforcement in Minneapolis has continued. Whether the visibility provided by commuting creates sufficient deterrent effects to justify the risks involved remains a contested question within the activist community.

What's the difference between visible and invisible activism strategies?

Visible activism prioritizes public documentation, media engagement, and building narrative pressure through public awareness. Invisible activism prioritizes operational security, limited visibility, and focuses on direct services like legal aid, mutual aid networks, and rapid response assistance. Both approaches have historical precedent and neither is objectively superior, though they're incompatible within a single organization.

How does Stancil's media accessibility shape public perception of the movement?

Because Stancil is highly accessible to journalists, frequently quoted in major publications, and willing to explain his tactics and appear on camera, he's become the public face of immigration activism in Minneapolis. This means people outside the city often know about commuting primarily through Stancil's narrative, which may or may not reflect how other activists view the tactic's importance or effectiveness.

What are the legitimate critiques of Stancil's approach that don't involve personal attacks?

The main substantive critiques are: commuting might shift enforcement to less-visible areas and endanger people not involved in the tactic; media visibility about tactics can help federal agents prepare countermeasures; the focus on individual visible activism might distract from less visible but potentially more effective work like legal aid and community networks; and Stancil's position as the most visible activist might create incentive structures that prioritize visibility over effectiveness.

Why do some experienced organizers think operational security should override media engagement?

Organizers with experience in movements facing government repression understand that the more information about tactics and participants that enters the public record, the more vulnerable everyone becomes to surveillance and prosecution. They believe that protecting the network and the people in it is more important than building a public narrative, especially if the public narrative doesn't actually change policy outcomes.

What would it take for commuting to become a more accepted tactic within Minneapolis activism?

Acceptance would likely require some combination of: clear evidence that commuting actually prevents arrests or reduces violence in specific measurable ways; agreement from broad sections of the activist community about what the tactic's goals are and how success will be measured; explicit discussion of how the tactic's risks are distributed and whether that distribution is just; and potentially stronger operational security protocols that allow commuting to proceed with less media visibility and exposure.

What Comes Next

The conflict between Stancil and the moderators isn't resolved. It probably won't be, not cleanly. People will keep commuting. People will keep criticizing it. Some will think it's crucial work. Others will think it's performative. Both views will have some validity.

What matters is that people in Minneapolis are trying to respond to federal power in real time, without a clear playbook, with genuine disagreement about strategy and tactics. That's what real movements look like. Not unified. Not certain. But trying.

Stancil is one person trying in a particular way. The moderators are other people trying in a different way. They're in conflict because they're trying different things, and those different things can't coexist in the same space without friction.

That friction is uncomfortable. But it's also honest. It's what happens when people care enough about something to fight over the right way to do it.

The actual immigrants facing federal enforcement probably don't care whether Stancil is right or the moderators are right. They care whether they get arrested. They care whether they have legal representation. They care whether they have community support. Whether that help comes through visible or invisible means is secondary to whether it works.

That's the real test. Not whether Stancil is a good activist or a bad one. Not whether his media engagement helps or hurts the narrative. But whether anyone is actually better off because of what he's doing.

The evidence on that question is mixed. Some people are better off. Some people might be worse off. Some of the impact is too small or too long-term to measure right now.

That's honest. And it's probably the best we can do with this question right now.

Key Takeaways

- Will Stancil's commuting tactic documents ICE enforcement but divides Minneapolis activists over operational security and effectiveness

- Media visibility helps amplify the narrative but creates friction with organizers prioritizing security and protecting vulnerable communities

- The core tension is unresolved: does documentation create accountability or just shift where enforcement happens?

- Stancil's accessibility to journalists makes him the public face of the movement, which distorts external perception of broader resistance efforts

- The conflict reveals fundamental disagreements about visibility vs. security that most social movements must navigate without clear answers

Related Articles

- Inside Minneapolis ICE Shooting and Protest Response [2025]

- Minneapolis General Strike Against ICE: Inside the Movement [2026]

- DIY Resistance: How Makers Are 3D-Printing Tools Against ICE [2025]

- Government Censorship of ICE Critics: How Tech Platforms Enable Suppression [2025]

- How ICE Shifted From Visible Raids to Underground Terror in Minneapolis [2025]

- Tech Workers' Fear Culture: Inside the ICE Silence Crisis [2025]

![Will Stancil and ICE Commuting in Minneapolis: Activism, Controversy, and Community Divide [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/will-stancil-and-ice-commuting-in-minneapolis-activism-contr/image-1-1771585590237.jpg)