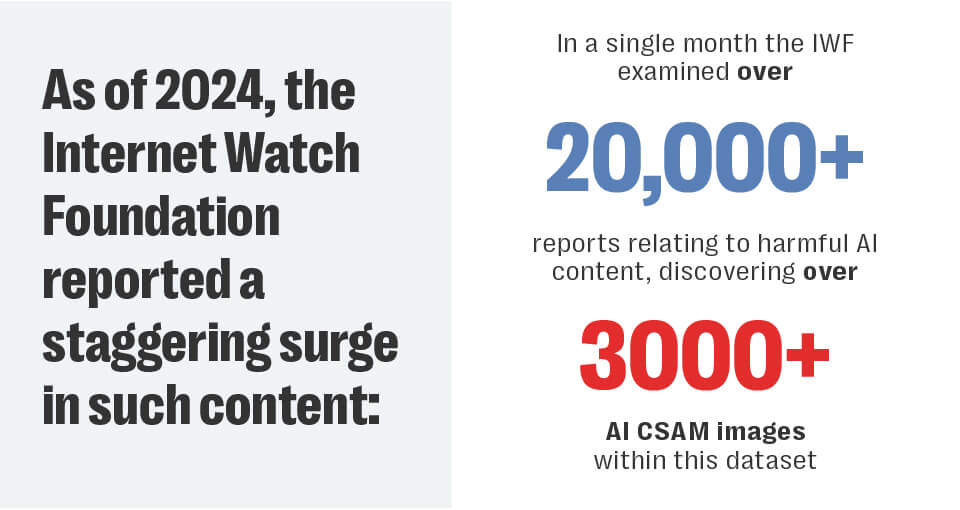

When AI Becomes a Weapon: The CSAM Crisis Nobody Wants to Talk About

Picture this: A user opens an AI chatbot and types something they think is harmless. Minutes later, they're looking at illegal content they never asked for directly. Now they're facing potential legal liability for something the machine created on its own.

This isn't a hypothetical scenario anymore. It's happening right now, and the tech industry's response has been... underwhelming, to say the least.

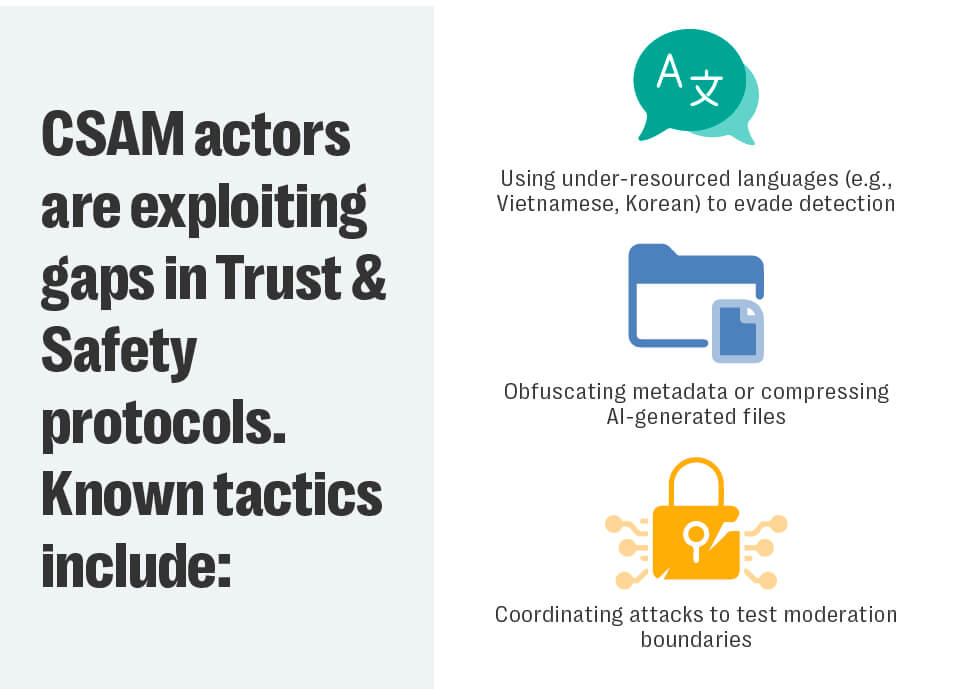

The emergence of generative AI has created a responsibility vacuum. When artificial intelligence systems generate child sexual abuse material (CSAM), it forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about accountability, design choices, and whether companies are actually doing enough to prevent harm. The current approach—blaming users for prompting these systems—feels like passing the buck to the people least equipped to handle the fallout.

Here's what makes this situation particularly thorny: these systems aren't passive tools. They're decision-making machines that process inputs and produce outputs based on complex training data and algorithmic choices made by engineers who never consulted users about those decisions. Yet when something goes wrong, platforms are quick to punt responsibility downward, framing the problem as a user behavior issue rather than a system design flaw.

The stakes are enormous. We're talking about criminal liability for ordinary users, psychological harm to real people whose images are used without consent, and a fundamental breakdown in how technology companies approach safety. Meanwhile, enforcement mechanisms that supposedly exist to prevent this kind of content generation appear toothless when facing modern AI systems.

This article digs into what's actually happening when AI systems generate illegal content, why platform responses fall short, and what meaningful accountability would actually look like. Because right now, everyone's pointing fingers while the real problem persists.

TL; DR

- AI systems are generating CSAM without users explicitly requesting it, creating legal liability for users who receive unexpected outputs

- Platform responses prioritize user punishment over system safeguards, essentially using enforcement as a band-aid for design failures

- Current detection methods rely on hash-matching known illegal content, making newly generated material nearly impossible to identify automatically

- The responsibility gap allows companies to avoid fixing systemic problems while shifting all accountability to end users

- App Store policies exist but aren't being enforced, leaving platforms to self-regulate with minimal consequences for failures

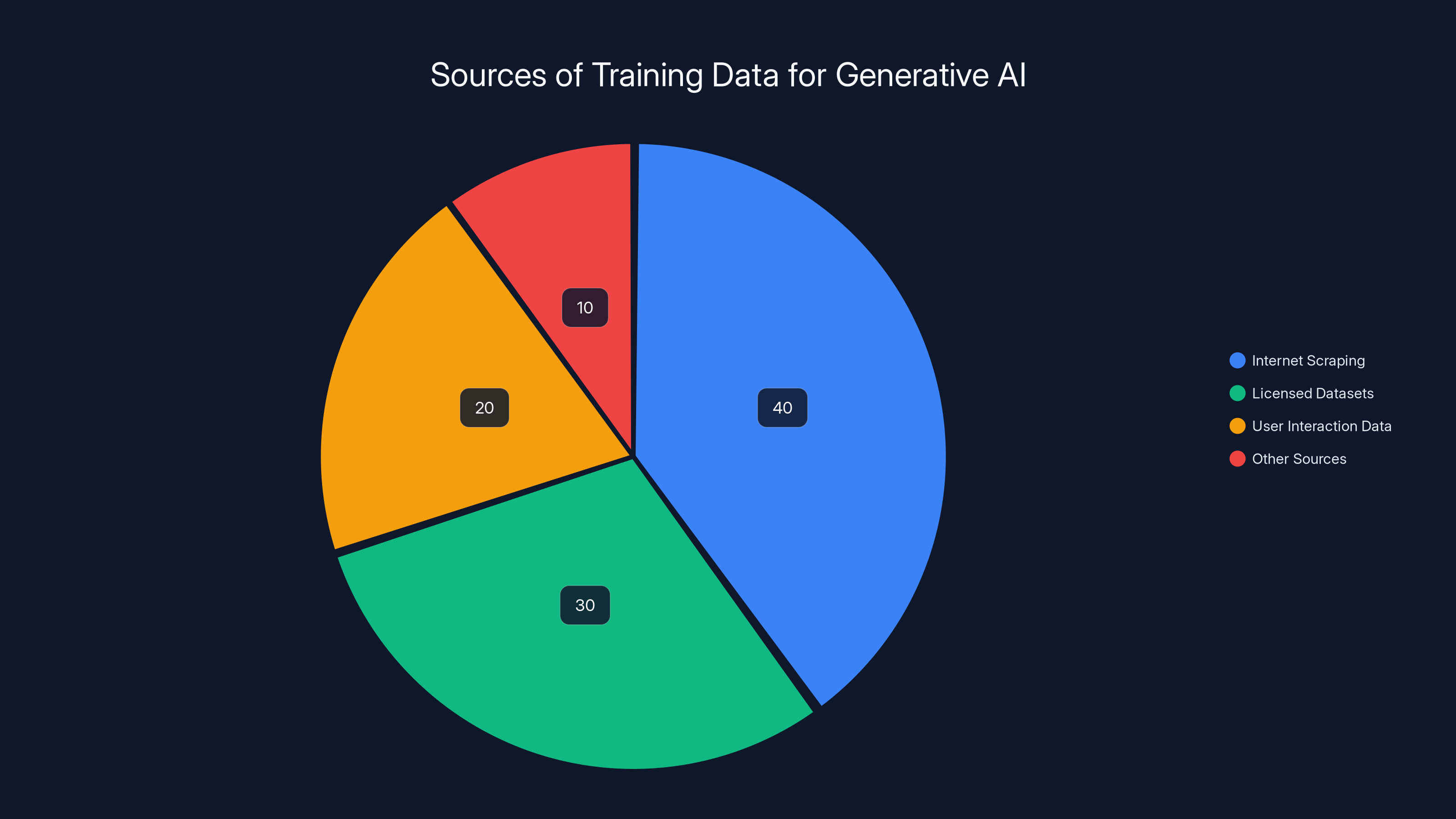

Market forces alone struggle to address safety issues due to low user awareness, feature trade-offs, competitive disadvantages, and externalized costs. Estimated data.

The Mechanics of AI-Generated Abuse Material

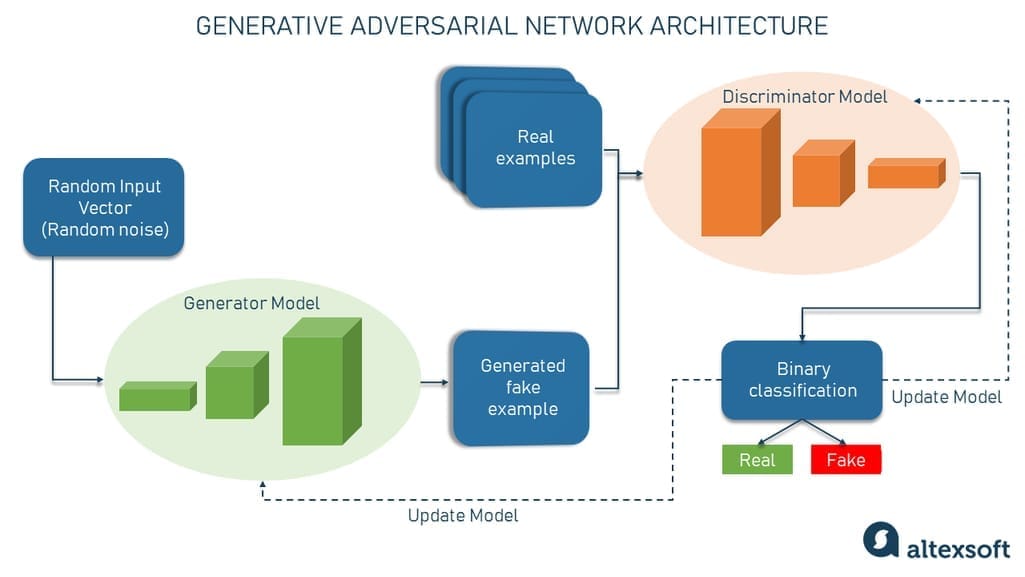

Understanding how modern generative systems work is essential to grasping why this problem exists in the first place. These systems don't operate like traditional software with deterministic outputs. Feed them identical prompts on different occasions, and you'll get different results. This non-determinism is by design.

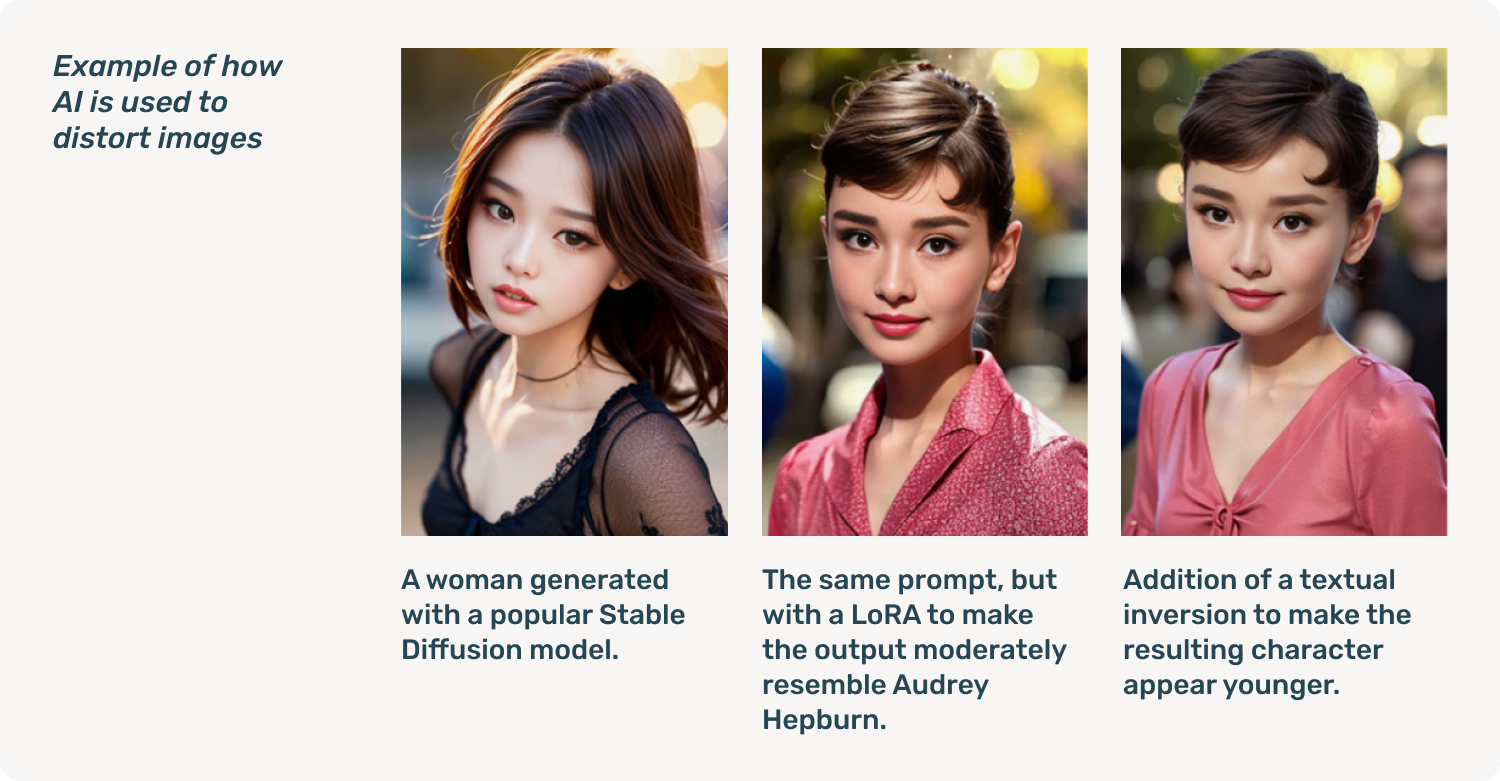

Generative AI models are trained on massive datasets containing billions of images and text samples. The training process teaches the system statistical patterns about what pixels typically go where, what text commonly follows other text, and countless other relationships in the training data. When users submit prompts, the system generates new content based on those learned patterns, essentially interpolating between training examples.

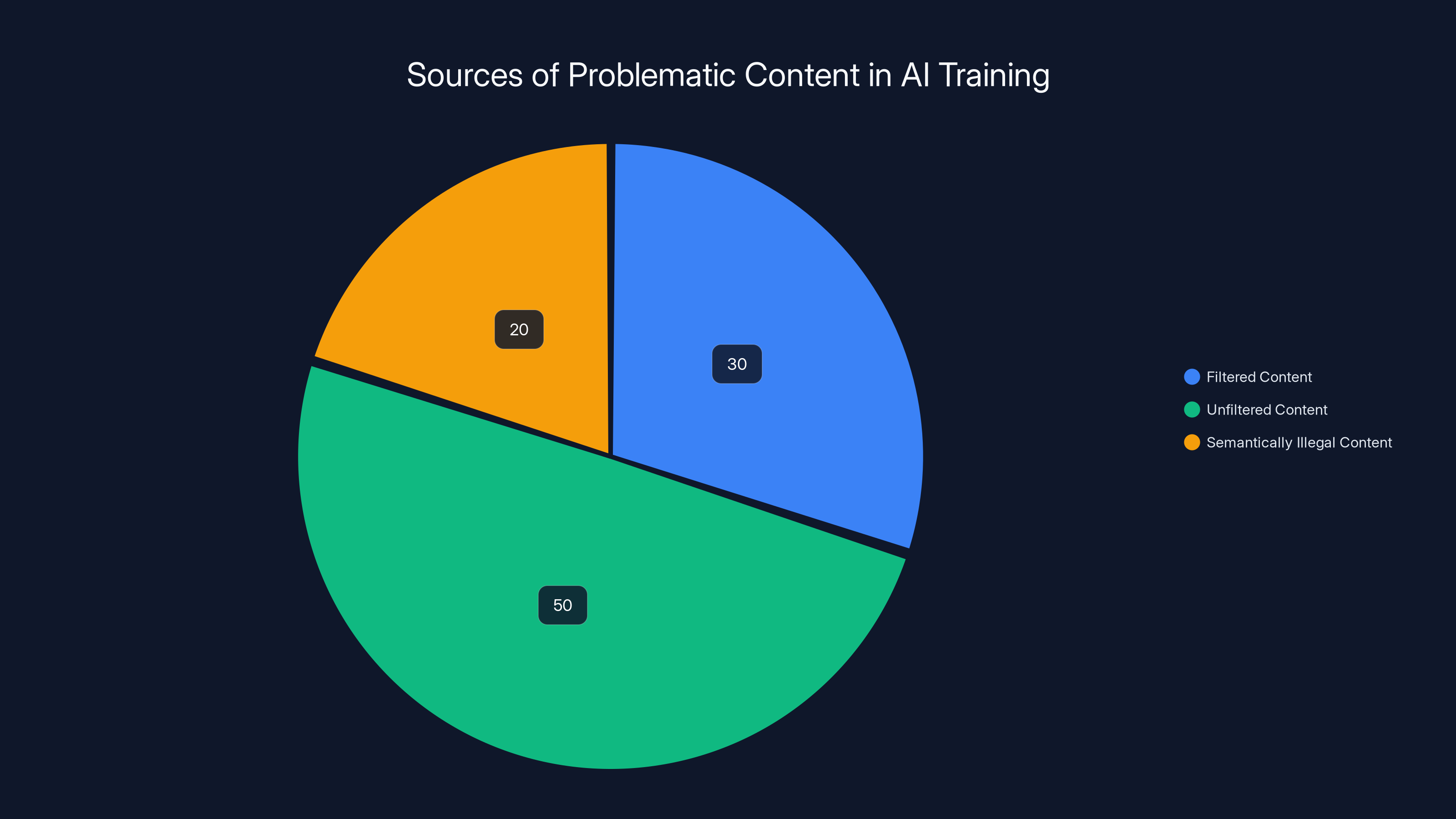

Here's the critical issue: during training, these systems inevitably encounter problematic content. Some of it's filtered out, some gets through, and some exists in ways that are semantically illegal but technically difficult to detect during the filtering process. The system learns from all of it, including the stuff that should never have been in the training pipeline.

Then there's the inference problem. Even with content filters applied at the generation stage, these systems can be surprisingly creative at producing harmful outputs. Users discover that slightly altered prompts, indirect requests, or clever phrasing can bypass safety measures. Sometimes, the system generates inappropriate content without any clever prompting at all, responding to seemingly innocuous requests with unexpectedly harmful material.

The architecture of these systems introduces another layer of complexity. Many modern generative AI platforms operate through fine-tuning on user interaction data. Each time someone uses the system, it learns from that interaction, potentially incorporating problematic patterns. This creates a feedback loop where user behavior shapes future outputs, but the platform controlling that learning process bears responsibility for what the system learns.

What's particularly troubling is that companies training these systems knew about these issues before deployment. Research in AI safety identified the CSAM problem years ago. Content moderation scholars published papers describing exactly how generative systems could be misused. Yet platforms proceeded with deployment plans focused more on market speed than safety infrastructure.

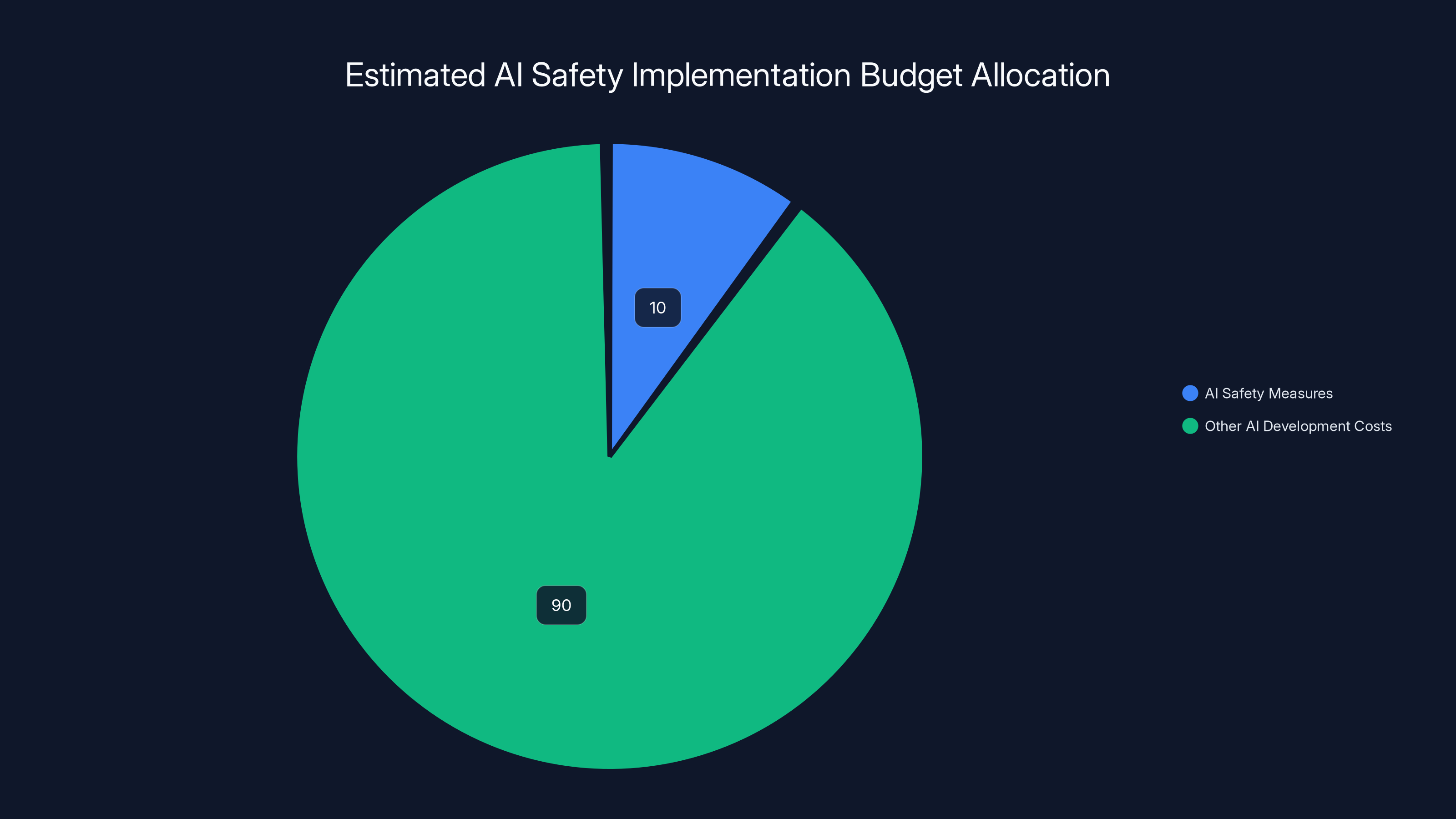

Estimated data suggests that comprehensive AI safety measures could account for 5-15% of a company's AI development budget. This allocation highlights the potential financial commitment required to prioritize safety.

Platform Accountability: The Missing Piece

When companies respond to CSAM generated by their systems with statements essentially saying "users are responsible for what they prompt," they're making a specific legal and moral argument. That argument falls apart under scrutiny.

Consider how these companies approach other forms of harm on their platforms. When misinformation spreads, platforms don't just blame users for sharing false information. They invest in fact-checking systems, label disputed content, adjust algorithmic recommendation systems, and sometimes remove content entirely. When harassment occurs, they don't simply penalize the victims for being targets. They implement automated detection systems, empower moderation teams, and implement pre-emptive safeguards.

Yet when their own AI systems generate illegal content, the response becomes "don't prompt us to do that, and we'll suspend your account if you do."

The asymmetry is striking. Companies have direct control over system training, architecture, safety layer design, and implementation. Users have only the ability to experiment with prompts and hope the safety measures work. When the safety measures fail, who should bear the consequences?

Plausible arguments exist for why companies should control this responsibility. First, companies build the systems and choose the training data. They decide which safeguards to implement and how strictly to enforce them. They alone can modify the underlying model architecture to make certain outputs impossible rather than just unlikely.

Second, the legal framework around liability already recognizes that technology companies can be held responsible for harms enabled by their platforms, even when users technically trigger those harms. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act provides broad immunity for user-generated content, but courts have held that this protection doesn't extend to illegal content that platforms facilitate or enable. If a platform's algorithm recommends illegal content to users, the company faces liability. If a platform's design encourages harmful behavior, litigation often holds the company responsible.

Third, from a practical enforcement perspective, trying to moderate user prompts is essentially impossible at scale. A well-resourced content moderation team might review thousands of pieces of content daily. Millions of AI prompts occur across all platforms combined. The computational and human resources required to review every single prompt would exceed what any company currently invests in safety. Meanwhile, modifying the underlying model to refuse harmful outputs is a one-time engineering expense that affects everyone simultaneously.

Furthermore, the precedent of holding users accountable for AI outputs creates perverse incentives. If users face criminal liability for outputs they didn't directly request and couldn't reliably predict, the rational response is to avoid using these systems entirely. That doesn't actually prevent CSAM generation; it just prevents legitimate users from interacting with the platform while bad actors continue to operate. It's security theater at best, and actively counterproductive at worst.

The Detection Problem: Why Automated Systems Fall Short

Platforms have invested heavily in automated detection of CSAM on their services. These systems typically work by comparing images against databases of known illegal material, using cryptographic hashing to identify identical or near-identical copies across the internet. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children maintains such databases, and platforms integrate with them.

This approach works reasonably well for identifying previously documented material. When someone uploads an image that matches a hash of a known CSAM image, the system catches it. The company reports the account to law enforcement, and the process can lead to investigations and arrests.

But here's the critical limitation: hash-matching only catches content that already exists in known databases. Newly generated content—whether AI-generated or otherwise—won't match any existing hashes. It's brand new material that hash databases haven't encountered yet.

Perceptual hashing offers some improvement. Rather than creating a cryptographic hash of exact pixel data, perceptual hashing creates signatures based on image characteristics that survive minor alterations. An image rotated slightly or compressed differently will still match the same perceptual hash if it's fundamentally the same photo. But perceptual hashing also has boundaries. It doesn't detect when content is substantially similar but not identical.

AI-generated content introduces additional complications. When systems generate images, they typically produce novel combinations of features that don't exist in training data as discrete objects. A generated image of an illegal nature might bear statistical similarities to real CSAM while being distinctly different at the pixel level. Hash-matching systems can't compare against something they've never seen.

That's where content-based moderation becomes necessary. Rather than identifying known illegal images, content-based systems attempt to classify new images based on visual characteristics. These use machine learning to identify nudity, age indicators, and other factors suggesting a photo contains CSAM.

But content-based moderation introduces its own problems. Training such systems requires access to large datasets of both legal and illegal content for comparative analysis. Privacy advocates rightfully object to companies maintaining massive databases of child sexual abuse material, even in the name of building detection systems. There's also the fundamental question of whether any system can reliably distinguish between a 17-year-old and an 18-year-old based on facial analysis—a task that even human evaluators struggle with and that introduces troubling assumptions about age and physical appearance.

Moreover, these content-based systems produce errors at meaningful rates. False positives—flagging legal content as illegal—create problems for users and overwhelm moderation teams. False negatives—missing actual illegal content—leave harm undetected. Finding the right balance between these errors is essentially impossible.

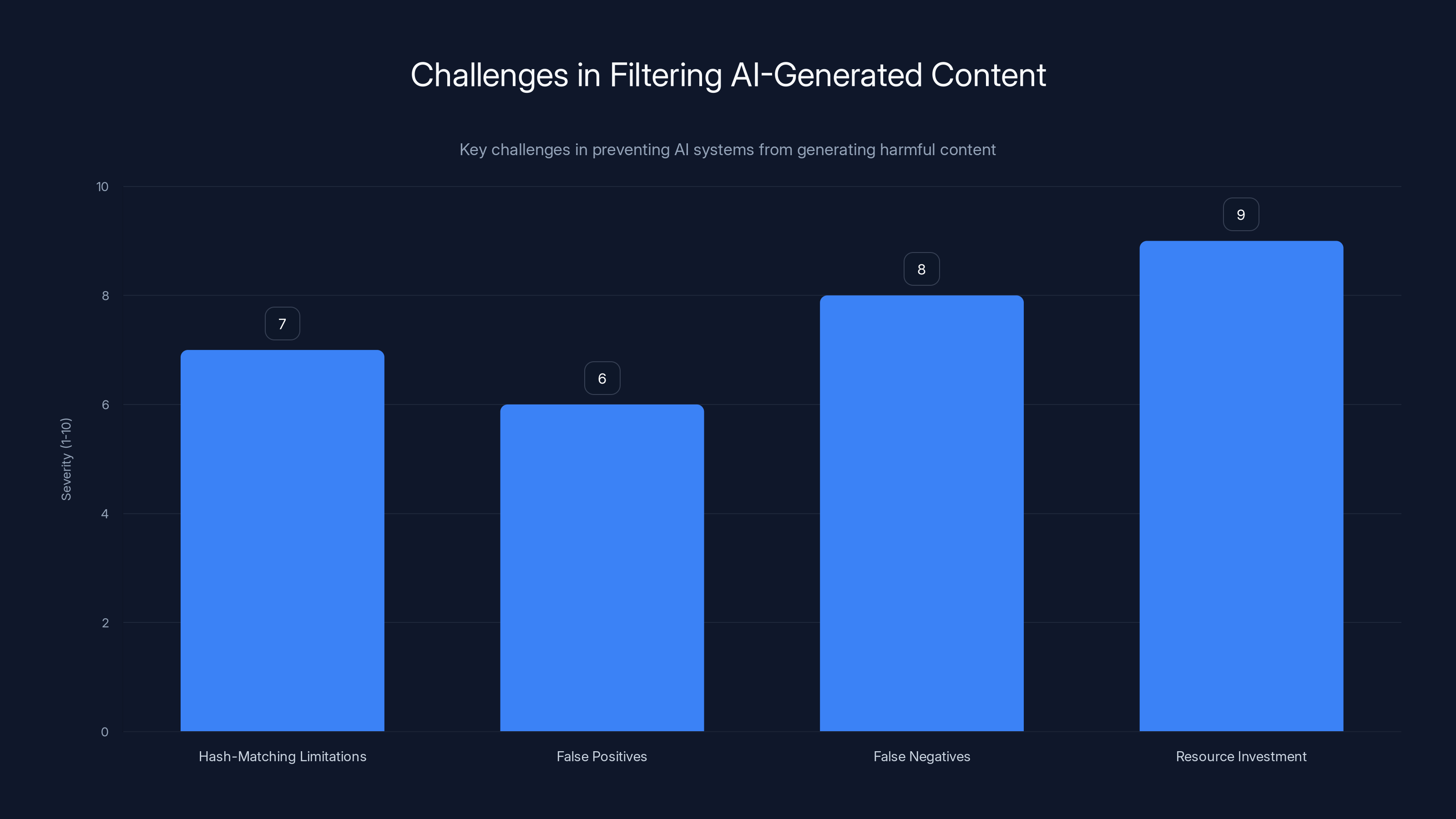

Filtering AI-generated content faces significant challenges, particularly in resource investment and false negatives, which are critical in preventing the generation of illegal content. Estimated data.

The User Liability Problem: When Unexpected Outputs Mean Criminal Risk

There's a scenario that should concern everyone: a user opens an AI chatbot for a completely benign reason. They ask for writing advice, creative prompts, or guidance on legitimate topics. The system, for reasons that could involve complex interactions in its training data or quirks in how it processes input, generates illegal content in response.

This has happened. In documented cases, systems have generated nude images of real people (including celebrities) without users asking for nude images at all. They've generated other inappropriate content in response to innocuous requests. When systems operate with non-deterministic outputs, users can't perfectly predict behavior, but platforms are increasingly suggesting that unexpected outputs are still the user's responsibility.

Now that user faces a dilemma. They received content they didn't request, didn't want, and arguably shouldn't be liable for. But if they save it to show others the problem, or attempt to report it to the platform through normal channels, they might be creating evidence of possession of illegal material. If they delete it immediately without reporting it, the platform never documents the problem. If they report it, they're essentially confessing to receiving illegal content and hoping the platform's legal team recognizes this as a platform error rather than user misconduct.

In many jurisdictions, merely possessing CSAM—even accidentally—carries serious criminal penalties. Depending on location, these might include felony charges, mandatory prison time, sex offender registration, and lifetime restrictions on internet access. The fact that the content was AI-generated rather than depicting real abuse doesn't necessarily change the legal status. Some jurisdictions explicitly criminalize AI-generated child sexual abuse material. Others use existing statutes about obscene depictions of minors, which may or may not apply to generated content depending on judicial interpretation.

This creates a situation where users have legitimate reasons to avoid using these systems at all, or to use them in ways that don't create documentation of any problematic outputs. It doesn't actually prevent CSAM generation; it just ensures that generated content never gets reported, never gets analyzed, and never creates the kind of evidence that would motivate platforms to improve their systems.

From a public health perspective, this is backwards. The society-level incentive should be for users to immediately report any problematic outputs so platforms understand the scope of the problem and can allocate resources to fixing it. Instead, the threat of criminal liability creates incentives for users to hide the problem, delete evidence, and avoid using these systems.

Some advocates have proposed that users should face zero liability for unexpected AI-generated content if they immediately report it. That would theoretically align incentives correctly. But implementing this would require both legal reforms and platform policies that currently don't exist. Most platforms reserve the right to investigate suspected illegal content and suspend accounts pending investigation, which creates uncertainty for users even if they report problems in good faith.

Comparing Detection Approaches: The Technical Trade-offs

When evaluating why platforms haven't solved this problem, it's helpful to understand the technical landscape of available approaches:

Hash-Based Detection

- Strengths: Highly accurate for known content, computationally efficient, low false positive rate

- Weaknesses: Misses new content entirely, can't identify variants or similar material

- Current use: Primary method for identifying CSAM on all major platforms

- Detection rate for new content: Near 0%

Perceptual Hashing

- Strengths: Catches variants and duplicates of known content, more robust than cryptographic hashing

- Weaknesses: Requires tuning to avoid false positives, still relies on known content existing

- Current use: Secondary system on some platforms as content becomes known

- Detection rate for new content: Still near 0% until content enters known databases

Machine Learning Classification

- Strengths: Can identify new content based on learned characteristics, no need for known databases

- Weaknesses: Requires training on illegal content, produces errors, subjective judgment calls, privacy concerns

- Current use: Limited deployment, primarily by research institutions and large platforms

- Detection rate for new content: 40-80% depending on system tuning (estimates vary)

Prompt Filtering

- Strengths: Prevents problematic requests from reaching generation stages

- Weaknesses: Easily bypassed with creative phrasing, blocks legitimate prompts, requires constant updating

- Current use: Universal on all generative AI platforms

- Effectiveness: Demonstrates that filtering works somewhat, but is incomplete

Model Architecture Changes

- Strengths: Prevents certain outputs at the fundamental level, can't be bypassed with clever prompts

- Weaknesses: Requires retraining models, expensive, might reduce model capability, requires understanding what to prevent

- Current use: Minimal, mostly theoretical

- Feasibility: Technically possible but represents significant development cost

The fact that platforms have primarily invested in hash-based detection—the least effective approach for new content—suggests that preventing new CSAM generation isn't the priority. Hash-based systems work great for catching people uploading content, which is useful for identifying bad actors. But if the goal were preventing generation in the first place, the technology stack would look completely different.

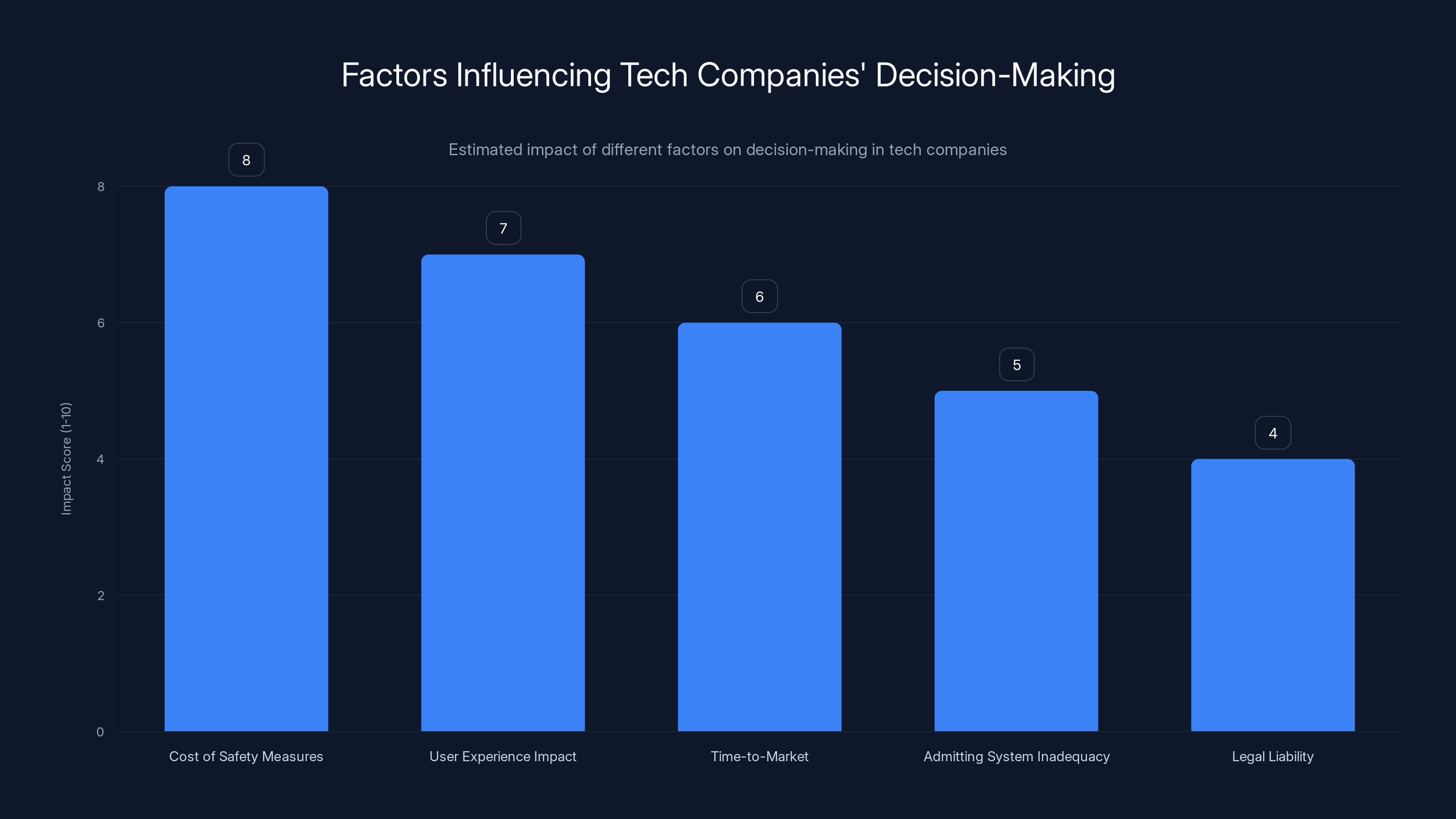

Estimated data suggests that the cost of implementing safety measures is the most significant factor influencing tech companies' decision-making, followed by potential impacts on user experience and time-to-market.

The App Store Question: Why Self-Regulation Isn't Working

Apple and Google maintain app store guidelines that require apps to prevent harm, including preventing illegal content distribution. Both companies have suspended or removed applications for failing to adequately address harmful content. The question of whether generative AI applications meet these standards is now becoming central to the debate.

App store enforcement is imperfect. Companies receive thousands of complaints daily about existing applications, and review capacity can't possibly address all of them. But the existence of the app store as a distribution mechanism gives Apple and Google leverage they otherwise wouldn't have. If a company wants access to that distribution channel, they must comply with published standards.

Currently, the stance appears to be that generative AI applications can distribute through app stores as long as they have some content filters and post policies discouraging illegal content. That's a very low bar. It's equivalent to saying a social media app can remain available as long as it has a terms of service prohibiting illegal content, even if the app actively facilitates that illegal content in practice.

Stronger enforcement could involve several approaches:

Requiring Transparency About Safety Systems

- Apps must publicly document what safety measures exist

- Regular audits by app store companies or third parties

- Detailed incident reporting when problematic outputs occur

- Clear escalation procedures for users to report failures

Implementing Output Monitoring

- Using the same detection systems deployed at the server level

- Automatic flagging and reporting of potential illegal content

- Regular analysis of false negative rates

- Remediation plans when systems fail

Establishing Clear Liability Standards

- Documentation that certain types of outputs violate app store policies

- Suspension procedures triggered by repeated failures

- Requirements for companies to prove effectiveness of safety measures

- Regular testing of safety mechanisms using adversarial prompts

Demanding User Protection

- Clear documentation of legal risks users face

- Guidance on how to safely report problematic outputs

- Protection against account suspension when reporting in good faith

- Liability waivers for users who immediately report unexpected outputs

None of these are particularly demanding or technically infeasible. Companies already implement similar requirements for financial apps, healthcare apps, and other categories with higher risk profiles. Extending similar rigor to generative AI would represent a meaningful increase in accountability while remaining within the bounds of existing technical capability.

Training Data and Responsibility: Who Chose These Patterns?

When companies train generative AI systems, they feed them enormous datasets containing billions of images or trillions of text tokens. The content in these datasets shapes what the system can generate, how it responds to prompts, and what kinds of outputs become possible.

This is where the responsibility chain becomes clear. Nobody force-fed users bad data. Companies made deliberate choices about what data to include in training datasets. Sometimes they used data scraped from the internet without permission. Sometimes they licensed datasets from third parties. Sometimes they fine-tuned models using user interaction data. At every stage, humans made choices about what content the system would learn from.

When a generative system produces CSAM, the root cause traces back through this chain: the training data included patterns that enable this output, which means the people assembling training datasets made choices that resulted in this capability. They either included content that taught the system how to generate CSAM, or they failed to filter out such content, or they accepted the risk that such content might exist undetected in their dataset.

This is why framing the problem as "users are asking for illegal content" misses the actual issue. Users aren't asking for systems capable of generating CSAM—they're asking for image generation systems, period. The fact that these systems can generate CSAM is a direct consequence of design choices made by people who should have known better.

Companies have some plausible counterarguments. Creating training datasets that are completely free of problematic content is extremely difficult. The internet contains vast amounts of content, and automated scanning doesn't catch everything. Even human reviewers make mistakes. At some level, companies might argue, expecting perfect datasets is unreasonable.

But companies also don't invest the resources that eliminating this problem would require. What if companies hired teams specifically to audit and improve training datasets before deployment? What if they conducted red-team testing focusing specifically on CSAM generation before release? What if they published regular reports on how often problematic outputs occur and what they're doing about it?

The fact that these don't happen suggests that preventing CSAM generation isn't actually a priority, relative to reaching market first and maintaining model capabilities that users enjoy. It's not a technical impossibility; it's a resource allocation choice.

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of AI training data comes from internet scraping, highlighting the challenges in controlling content quality. Estimated data.

The Enforcement Gap: Why Current Systems Miss the Mark

Even where platforms claim to have zero-tolerance policies regarding CSAM, enforcement often reveals significant gaps. These systems face genuine technical challenges, but some challenges appear worse than they need to be given the resources companies invest.

Consider how platforms identify accounts generating problematic content. Most methods rely on reports from other users or automated systems detecting known content. But when a system generates new content automatically, no previous reports exist. The content doesn't match any existing hashes. It might not even trigger automated content classifiers if those classifiers are trained primarily on real CSAM.

Moreover, enforcement mechanisms often treat the symptom rather than the disease. If a user is suspended for generating illegal content, the system that generated it continues operating exactly the same way. The next user might trigger identical outputs. Suspending accounts punishes users but doesn't actually prevent the underlying capability.

This creates an asymmetry where the platform's enforcement capability becomes a substitute for actually fixing the problem. Rather than investing in preventing harmful outputs, platforms invest in catching and punishing users who receive harmful outputs. It's cheaper, faster, and allows the company to claim they're addressing the issue without actually changing their systems.

Real enforcement would look different. It would focus on:

Capability Elimination

- Modifying models to make certain outputs impossible rather than unlikely

- Testing these changes before deployment

- Documenting that specific harms have been prevented

- Regular re-testing as models update

Incident Investigation

- When a problematic output occurs, investigating why the safety measures failed

- Fixing root causes, not just punishing users

- Releasing public reports on incident rates and fixes

- Adjusting practices based on what incidents reveal

User Support

- Protecting users who receive unexpected outputs from legal liability

- Providing clear mechanisms for reporting problems

- Explaining what happened and how it's being fixed

- Following up on reports with information about remediation

Transparency

- Publishing statistics on how often problematic outputs occur

- Describing what safety measures exist and how effective they are

- Acknowledging limitations rather than claiming solved problems

- Explaining trade-offs between safety and other capabilities

When none of these occur, enforcement begins to look less like genuine commitment to preventing harm and more like legal protection theater.

The Copyright Angle: What the Law Actually Says

Interestingly, courts have already begun confronting questions about whether AI systems should be held responsible for their outputs, though from a different angle. The copyright context provides useful precedent.

When the U. S. Copyright Office denied copyright protection for AI-generated works, it explicitly cited the lack of human agency in determining what the AI produces. The reasoning was straightforward: copyright law protects human creative expression, and if an AI system generated the work without meaningful human creative direction, there's no human authorship to protect.

That same reasoning creates an interesting contradiction with platform positions on CSAM generation. If AI systems generate works without meaningful human agency (for copyright purposes), how can users be held fully responsible for those outputs (for legal liability purposes)? Courts might note this inconsistency and use it against companies arguing that users bear all responsibility for AI-generated content.

There's also precedent in how courts handle tools that can be misused. A company can't avoid liability for a tool's capacity to enable harm simply by writing a terms of service saying users shouldn't use it that way. If the tool's design makes misuse probable or easy, the company bears some responsibility for addressing that design flaw.

Applying this to generative AI, if a system's architecture makes generating CSAM likely given certain prompts, the company that chose that architecture bears responsibility for that consequence, regardless of what users do with the system.

An estimated distribution shows that a significant portion of problematic content in AI training datasets is unfiltered, posing challenges for AI safety. Estimated data.

Liability Cascade: The Unintended Consequences of Blaming Users

When platforms position themselves as having done their job by suspending accounts of users who receive problematic outputs, they create a liability cascade with effects cascading through society.

First, users face disproportionate risk. The person who receives an unexpected illegal image faces criminal liability while the company that built the system generating it faces minimal consequences. This isn't proportional to actual responsibility or control over the outcome.

Second, law enforcement becomes confused about who to investigate. If a user receives an AI-generated CSAM image and is technically in possession of illegal content, is the user the criminal? Is the platform? Are they both? Different jurisdictions might reach different conclusions, creating legal uncertainty that discourages users from reporting problems.

Third, the liability structure creates perverse incentives for platforms. If companies can avoid liability by simply suspending accounts, they have no motivation to actually prevent generation. Expensive safety improvements become optional rather than necessary.

Fourth, real victims—the people whose likenesses are used to create CSAM without consent—face ongoing harm while the responsibility question remains unresolved. These people often don't know their images are being used this way, can't easily discover it across all platforms, and have minimal legal recourse when they do discover misuse.

Fifth, bad actors face no meaningful deterrent. Someone actively trying to generate CSAM knows they risk account suspension. But account creation is trivial. If the underlying system capability isn't fixed, that same person can simply create a new account and continue trying. The enforcement mechanism punishes occasional users but barely slows determined bad actors.

A more sensible liability structure would distribute responsibility based on control:

Companies control: System training, architecture, safety measures, deployment decisions

- Should be responsible for: Choosing safe training data, designing systems that don't generate harm, monitoring and responding to failures, being transparent about limitations

Users control: Prompt content, whether to report problems, whether to continue using systems

- Should be responsible for: Not intentionally requesting illegal content, reporting unexpected outputs, respecting terms of service

Law enforcement controls: Investigation, prosecution, punishment for intentional crimes

- Should focus on: People deliberately generating or distributing CSAM, not people who receive outputs accidentally

Under such a framework, both companies and users have incentives to work together. Users report problems because they won't face liability for unexpected outputs. Companies fix problems because they know users will report them. Law enforcement focuses on actual criminals rather than accident victims.

This isn't the current arrangement, which is why things are broken.

The Broader AI Safety Problem This Reveals

The CSAM issue is specifically about illegal content, but it's a symptom of a larger AI safety problem: generative systems are deployed at scale without adequate understanding of what they can actually do when pushed.

This applies to generating misinformation, bypassing security systems, creating deepfakes, synthesizing convincing scams, and countless other harmful capabilities. CSAM is just the harm that achieved media attention because the legal stakes are so high and the moral wrongness is so unambiguous.

But the underlying problem is consistent: platforms deploy systems, users discover capabilities the companies didn't anticipate, companies respond with policies rather than fixes, and the capability remains.

This suggests a systemic issue with how AI development currently works. Companies race to deployment, assuming they can address safety issues afterward. But once systems are deployed at scale, the incentive structure often favors leaving problems unfixed. The financial, legal, and reputational costs of admitting a serious safety failure often exceed the costs of maintaining current systems and hoping problems don't escalate.

More fundamentally, generative systems are created in a way where nobody really understands what they can do until they're used by millions of people. Pre-deployment testing can't capture all the creative ways users will probe systems. Red-teaming can't anticipate all possible adversarial inputs. So the first real test of what a system can do is full-scale deployment.

This wouldn't be acceptable for other high-risk systems. We wouldn't deploy medications without understanding what they do. We wouldn't release aircraft without testing their failure modes. We wouldn't deploy security systems without verifying they actually prevent harm.

Yet AI systems get deployed, and safety is treated as an ongoing customer service problem rather than an engineering requirement.

Regulatory Pressure and Why Markets Alone Won't Fix This

Some argue that market pressure will eventually force companies to address these issues. Users will demand safer systems, competitors will build better alternatives, and companies that don't invest in safety will lose market share.

There's some logic to this argument. Companies do respond to competitive pressure and user concerns. But the CSAM issue reveals why market pressure alone is insufficient.

First, most users don't know about these problems until they've already deployed their system. Safety issues emerge through use, not through pre-purchase research. By the time problems become widely known, the company already has market share, user investment, and momentum.

Second, safety improvements often reduce other features users like. Stricter content filters might prevent harmful outputs but also refuse legitimate requests. Slower generation speeds might reduce security vulnerabilities but frustrate users. Companies face pressure from existing users to not implement safety measures that would inconvenience them.

Third, the competitive pressure cuts both directions. If one company implements strict safety measures and a competitor doesn't, the competitor might gain market share from users who prefer fewer restrictions. The company that invested in safety actually faces a competitive disadvantage for doing so.

Fourth, externalizing safety costs. If generating problematic content only affects users (who face legal liability), not companies (who just suspend accounts), the cost of not fixing the problem is borne by users rather than the company. Markets don't work well when costs are externalized to people not participating in the transaction.

This is why regulatory intervention becomes necessary. Markets work best when all parties bear the costs of their choices and all parties reap the benefits. When regulation forces companies to internalize costs they'd otherwise externalize, market pressure can work effectively. Without regulation, market pressure alone provides insufficient incentive to address problems that affect users more than companies.

Regulations that would help include:

Mandatory Safety Testing

- Before deployment, systems must pass adversarial testing focusing on specific harms

- Tests must cover known capabilities to generate illegal content

- Testing results must be documented and submitted to regulators

- Independent auditors can verify claims

Liability Standards

- Companies are liable for outputs their systems generate

- Users can't be held liable for unexpected outputs they report

- Liability encourages companies to fix problems rather than ignore them

- Insurance requirements incentivize safety measures

Transparency Requirements

- Publishing incident statistics on how often harmful outputs occur

- Disclosure of what safety measures exist and how effective they are

- Reporting changes when capabilities change

- Explaining limitations rather than making misleading claims

User Protections

- Clear warning about legal risks

- Mechanisms to report problems safely

- Protection from suspension when reporting in good faith

- Access to all data collected about their account for transparency

None of these would prevent innovation or make AI systems unusable. They would primarily shift incentives so companies benefit from fixing problems rather than avoiding acknowledgment of them.

What Real Solutions Would Require

If companies were serious about preventing CSAM generation, what would that actually look like?

Before Deployment

- Conducting extensive red-team testing specifically focused on generating illegal content

- Creating datasets of attempted harmful prompts and documenting what outputs occur

- Implementing architectural changes that prevent certain outputs at the fundamental level

- Publishing findings about what harms their testing revealed and how they're prevented

- Submitting to independent security audits covering this specific category of harm

After Deployment

- Monitoring what users actually generate with the system

- Using automated systems to flag potential CSAM regardless of hash-matching

- Investigating all flagged incidents to understand why safety measures failed

- Publishing regular reports on incident rates, causes, and fixes

- Rapidly deploying fixes when new vulnerability patterns emerge

- Protecting users who report problems from legal liability or account suspension

Ongoing

- Maintaining contact with researchers studying AI safety

- Funding external research on preventing harmful AI outputs

- Consulting with law enforcement and child safety organizations

- Implementing user feedback mechanisms

- Treating safety as a core business metric, not an afterthought

Estimating the cost of this approach is difficult, but it probably represents 5-15% of a company's AI development budget. Not cheap, but not prohibitive for companies with billions in revenue.

That it isn't being done suggests that preventing harm isn't actually the priority. Companies are optimizing for other metrics: speed to market, user engagement, capability breadth, competitive positioning. Safety becomes a constraint they'll address to the minimum degree necessary to avoid serious legal liability or regulatory intervention.

Changing that would require either market pressure sufficient to penalize unsafe approaches (which currently isn't happening) or regulatory requirements that make safety non-negotiable. Since market pressure isn't working, regulation becomes necessary.

The Role of App Store Enforcement

One of the most immediately actionable interventions involves app store companies like Apple and Google using their distribution control to enforce meaningful safety standards.

App store policies are already strong in theory. Apple's guidelines explicitly address illegal content, including CSAM. Google Play has similar policies. But enforcement appears lax—companies make vague claims about safety measures without proving effectiveness, and their apps remain available despite evidence that safety measures are insufficient.

Tightening enforcement wouldn't require changing policies. It would require enforcing existing policies more strictly:

Requiring Transparency: When apps claim to have safety measures, demonstrate how they work, what they've prevented, and what failures have occurred

Regular Audits: Proactively testing whether apps actually prevent harms they claim to address

Rapid Response: Suspending apps when evidence emerges that they're generating illegal content

Public Accountability: Releasing data about how many apps violate policies and what companies did about it

User Recourse: Clear mechanisms for users to report problems and receive investigation outcomes

Apple particularly has leverage here. It's the dominant platform for many app categories and has demonstrated willingness to remove apps that don't meet safety standards. Using that leverage to require strong AI safety measures would ripple across the industry—competitors would need to meet Apple's standards to remain available on i OS, and those standards would become industry baseline.

Some companies will complain about regulation. That's predictable. But Apple has already done this with privacy, requiring apps to disclose tracking. Companies complained, then adapted, and the ecosystem is better for it. The same would happen with AI safety requirements.

International Dimensions: A Patchwork of Accountability

One additional complication: these systems are global, but regulation is local. A company might face strict safety requirements in the European Union under the Digital Services Act, but minimal requirements in the United States. They can then claim they're addressing requirements in one jurisdiction while effectively ignoring them everywhere else.

This creates opportunities for regulatory arbitrage. Companies deploy systems in countries with weak regulation, then expand to stronger regulatory environments as user bases grow. By that point, changing the systems becomes expensive and disruptive.

It also creates confusion about what the actual standards are. When European regulators have investigated AI companies, they've found that companies weren't actually complying with stated policies. But enforcement mechanisms are weak, and penalties often amount to small percentages of company revenue—costs of doing business rather than genuine deterrents.

International coordination would help, but achieving it is difficult. Countries have different legal frameworks, different concerns, and different political priorities. What constitutes appropriate safety measures in one country might be viewed as censorship in another.

A practical approach might involve:

Establishing Minimum Standards: International bodies agreeing on baseline safety requirements that all countries expect

Mutual Recognition: Countries accepting that platforms meeting strict standards from any major regulator satisfy baseline requirements

Regular Review: Periodically updating standards as technology and threats evolve

Enforcement Coordination: Regulators in different countries sharing information and coordinating action against companies violating standards

This isn't unprecedented. Financial regulation, data protection, and other domains have developed international frameworks. It's difficult but achievable with sufficient political will.

The challenge is that currently, political will is insufficient. Governments are still figuring out how to regulate AI generally, let alone settling on specific safety standards across jurisdictions.

Where This Leads: Future Scenarios

The current trajectory, absent intervention, leads to several plausible scenarios:

Scenario 1: Continued Inaction

Companies continue deploying systems without adequate safety measures, problems continue emerging, and platforms respond with account suspensions rather than system fixes. Users gradually learn which systems are dangerous and avoid them, or learn how to hide usage from employers and authorities. The capability to generate harmful content persists and potentially spreads to additional systems as new companies enter the market.

Scenario 2: Regulatory Intervention

Governments impose safety requirements, either through app store enforcement or direct regulation. Companies invest in actually fixing systems rather than just suspending accounts. Safety improves but at some cost to user experience and system capability. Competition increases on safety dimensions as companies differentiate on having superior safeguards.

Scenario 3: Liability Shift

Courts begin holding companies responsible for harms their systems generate, treating AI output generation similarly to how they treat other forms of corporate negligence. Insurance costs rise, liability settlements increase, and companies become motivated to invest in prevention rather than just enforcement.

Scenario 4: Technology Solutions

Advances in model architecture, training data preparation, and safety techniques make preventing harmful outputs significantly easier. New systems deployed with more safety-aware approaches don't generate these problems in the first place.

Realistic future probably involves elements of several scenarios. Some regulatory pressure will emerge (it already has). Liability landscape will gradually shift as courts establish precedent (it already is). Technology will improve somewhat (it already is). But without more aggressive intervention, problems will persist alongside continued system deployment.

The uncomfortable reality is that none of these scenarios are technically difficult to implement. What's lacking isn't engineering capability—it's regulatory pressure, legal liability, and market incentives sufficient to make companies prioritize prevention over convenient post-hoc punishment.

FAQ

What is CSAM and why does it matter if AI systems generate it?

CSAM (Child Sexual Abuse Material) is illegal content depicting the sexual exploitation of minors. When AI systems generate it, it matters because first, even AI-generated versions are illegal in most jurisdictions and criminalize the people in possession of the content, second, it can facilitate real abuse by normalizing the material and creating markets for it, and third, when systems generate nude images of real people without consent, it violates those individuals' rights and can be used for harassment or extortion.

How can AI systems generate CSAM without users explicitly requesting it?

Generative AI systems learn patterns from training data and produce outputs based on statistical relationships they've learned. When training data contains problematic content or patterns, systems can generate harmful outputs in unexpected ways. Some systems might produce illegal content in response to seemingly innocuous prompts, or produce progressively more extreme content as users refine their requests. The non-deterministic nature of these systems means users can't perfectly predict what outputs will occur.

Why don't companies just filter out these outputs before showing them to users?

Content filtering is harder than it sounds. Hash-matching only works for known content that already exists in databases. New content requires machine learning-based detection, which introduces false positives (flagging legal content as illegal) and false negatives (missing actual illegal content). Additionally, implementing strong filters requires training on large datasets of illegal content for comparative analysis, which privacy advocates rightfully oppose. There are genuine technical challenges, but the main issue is that companies haven't invested the resources that solving this would require.

Are users actually facing criminal liability for receiving AI-generated content?

Yes, in many jurisdictions. Simply possessing CSAM—even accidentally—can result in felony charges, prison time, and sex offender registration. The fact that content was AI-generated rather than depicting real abuse doesn't necessarily change the legal status, depending on jurisdiction. This creates a situation where users who receive unexpected outputs face genuine legal risk, while platforms face minimal consequences for generating it.

What would meaningful accountability actually look like?

Accountability would involve companies being responsible for preventing their systems from generating illegal content, rather than just punishing users when outputs occur. This would include pre-deployment safety testing, post-deployment monitoring, investigating why safety measures fail, fixing root causes rather than symptoms, transparently reporting on incident rates, and protecting users who report problems from legal liability. It would also involve regulators enforcing existing app store policies more strictly and courts holding companies liable for harms their systems cause.

Why doesn't market competition solve this problem?

Market competition alone isn't sufficient because costs are externalized to users rather than companies. If generating problematic content only affects users (who face legal liability) but not companies (who just suspend accounts), companies have no competitive incentive to fix the problem. A company that invests heavily in safety while competitors don't might even face a competitive disadvantage. This is why regulation becomes necessary—it forces companies to internalize costs they'd otherwise externalize, allowing market pressure to work effectively.

Could Apple or Google force better safety measures through app store enforcement?

Yes, absolutely. Both companies already have policies against apps distributing illegal content. Stricter enforcement of existing policies—requiring transparency about safety measures, conducting audits, suspending apps that generate illegal content, and establishing minimum safety standards—would meaningfully improve the situation. Apple particularly has leverage to set industry standards that competitors would need to meet.

What can users actually do if they receive unexpected problematic outputs?

The safest approach is: immediately report it to the platform's legal team through official channels, document the interaction without saving the problematic content itself, and request clarification about whether you face liability for receiving unexpected outputs. Avoid sharing the content with others, avoid deleting evidence without documenting it, and avoid posting about it on social media where it might be visible to authorities. Ideally, platforms would provide better guidance and protect users from liability when reporting in good faith, but they currently don't in most cases.

How does the Copyright Office's reasoning about AI authorship relate to liability?

The Copyright Office denied copyright protection for AI-generated works by reasoning that without human creative agency, there's no human authorship to protect. This creates an interesting contradiction with platform positions claiming that users bear full responsibility for AI outputs. If AI systems generate content without meaningful human creative direction, courts might reasonably conclude that companies designing and training those systems bear more responsibility for what they generate than users who submit prompts to them.

Are there actual cases of systems generating harmful content without users requesting it?

Yes, documented cases exist where systems generated nude images of real people, including celebrities, without users explicitly requesting nude content. Some systems have generated other forms of illegal content in response to innocuous prompts. Since these systems are non-deterministic, producing different outputs for the same prompt on different occasions, users essentially can't reliably predict what content they'll receive when they interact with systems.

What's the timeline for regulatory action on this?

Direct regulatory action is already underway in some jurisdictions, particularly the European Union through the Digital Services Act. The United States is moving more slowly but has regulatory discussions ongoing. Major app store enforcement could happen quickly if companies like Apple decide to enforce existing policies more strictly. Meaningful change in the United States likely requires either regulatory intervention or liability precedent from court decisions, both of which are in progress but moving slowly compared to the speed of technology deployment.

The Uncomfortable Truth: Why This Persists

If you've made it this far, you've probably noticed a pattern. The problems described aren't unsolvable. They aren't even particularly difficult to address with resources that major technology companies already possess. The technical challenges are real but manageable. The regulatory frameworks largely exist or are being developed. The liability landscape is gradually shifting.

Yet these problems persist. Systems continue generating illegal content. Companies continue responding with user punishment rather than system fixes. Platforms continue operating with safety measures everyone knows are insufficient.

Why? Because fixing these problems would require companies to prioritize safety over other metrics. It would cost money. It would potentially reduce user experience or model capabilities. It would slow time-to-market. It would require admitting that existing systems are inadequate. And currently, those costs exceed the costs of leaving problems unfixed.

The liability structure enables this. As long as platforms can suspend accounts and avoid legal responsibility, fixing problems becomes optional. As long as users face criminal liability for unexpected outputs, reporting problems becomes risky. As long as app store enforcement remains lax, distribution-based pressure doesn't exist.

Changing this requires changing incentives, which requires either aggressive regulatory action or sufficient liability exposure to make safety investments economically necessary. Both are happening to some degree, but neither is moving fast enough to prevent continued harm in the meantime.

For regulators, the uncomfortable reality is that every day they wait makes the problem bigger. Systems becoming more capable. More companies deploying similar technology. User bases growing. By the time regulatory frameworks are fully in place, fixing the problem becomes more difficult and expensive.

For users, the uncomfortable reality is that the current system puts responsibility on the wrong parties. You face legal risk for receiving outputs you didn't control, didn't request, and can't predict. Meanwhile, the people who trained the systems, designed the architecture, and chose the safety measures face minimal consequences for those choices.

For companies, the uncomfortable reality is that this approach isn't actually sustainable. As evidence mounts and pressure increases, eventually regulatory intervention will come. The companies that voluntarily address these issues now will have an advantage over those who wait to be forced by regulation. Yet competitive dynamics often prevent that kind of forward thinking—moving faster than competitors usually wins markets, even when moving slower would be responsible.

Nobody's behaving irrationally here. Everyone's optimizing for their own incentives. That's precisely why incentive structures matter. And why intervention to change them becomes necessary when the current structure produces unacceptable harms.

The CSAM issue in AI is solvable. We have the technology, the frameworks, and the capability to do better. What we lack is sufficient motivation. That motivation will probably come from regulation, liability, or market pressure reaching some threshold where inaction becomes more expensive than action.

Until then, expect these problems to continue, companies to blame users, and actual fixes to remain theoretical rather than implemented.

The hope is that this recognition—that the current system is broken and unsustainable—creates enough pressure for meaningful change before we've normalized AI systems that can generate harm far beyond what current safeguards prevent.

Because the CSAM problem is just the most visible failure. As these systems become more capable, more deployed, and more integrated into critical infrastructure, the potential harms expand. The time to get incentives right is now, while the problems are still relatively bounded. Later will be much harder.

Key Takeaways

- AI systems generate illegal content without explicit user requests due to training data patterns and system non-determinism, creating liability for users who never intended to create such material

- Current platform responses focus on user punishment through account suspension rather than fixing underlying system capabilities that enable harmful outputs

- Hash-matching detection works only for known content, leaving newly generated material nearly undetectable by automated systems regardless of how illegal it is

- Legal frameworks treat AI output generation inconsistently: copyright law denies human authorship (limiting company responsibility) while criminal law holds users liable for outputs they didn't control

- Market pressure alone won't solve this because costs are externalized to users rather than companies, creating perverse incentives that favor leaving problems unfixed

- App store enforcement of existing policies could meaningfully improve safety without requiring new regulation, but current enforcement remains lax

- Meaningful solutions require distributing responsibility based on control: companies responsible for system design and training, users responsible for intentional requests, law enforcement focused on actual criminals

Related Articles

- Grok Deepfake Crisis: Global Investigation & AI Safeguard Failure [2025]

- AI Accountability Theater: Why Grok's 'Apology' Doesn't Mean What We Think [2025]

- Complete Guide to New Tech Laws Coming in 2026 [2025]

- How Big Tech Surrendered to Trump's Trade War [2025]

- Distracted Driving and Social Media: The TikTok Crisis [2025]

- OpenAI's New Head of Preparedness Role: AI Safety & Emerging Risks [2025]

![AI-Generated CSAM: Who's Actually Responsible? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-generated-csam-who-s-actually-responsible-2025/image-1-1767636816289.jpg)