How Big Tech Surrendered to Trump's Trade War [2025]

Last year, the tech industry faced something it hadn't dealt with in decades: a US president willing to weaponize tariffs as a negotiating tool, and willing to do it on a whim.

Donald Trump's second term started with a bang. By February 2025, his administration issued tariffs ranging from 10 to 25 percent on imports from Canada, China, Mexico, and other major trading partners. Industry groups panicked. Economists warned of cost increases. Tech CEOs started making calls.

But here's what didn't happen: a sustained, coordinated pushback.

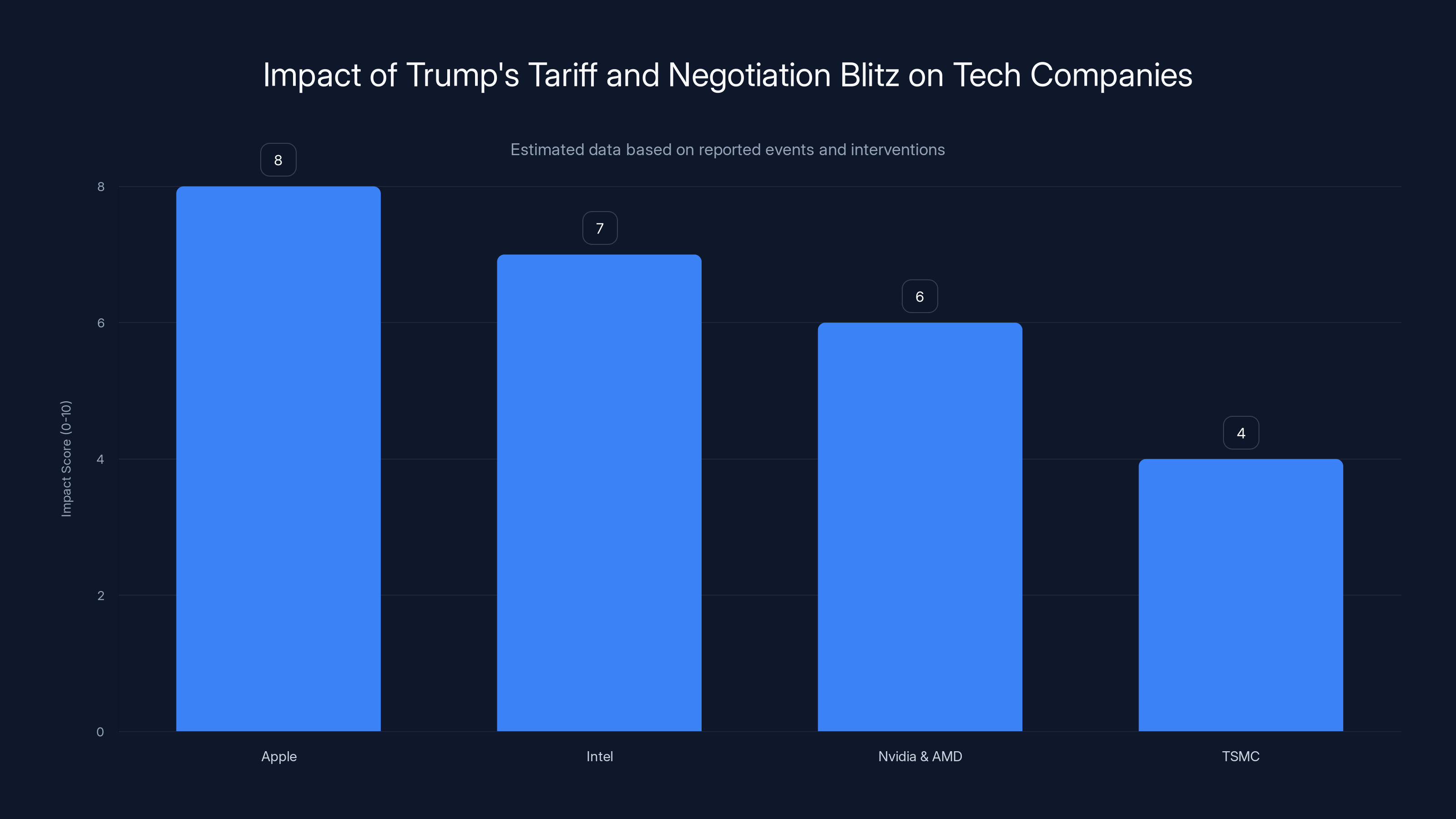

Instead, what we got was a series of surrenders so complete, and sometimes so absurd, that it's hard to tell whether Big Tech was playing 4D chess or just capitulating under pressure. Apple gave Trump a custom gold statue. Nvidia and AMD agreed to pay the US government a percentage of their international sales. Intel accepted a government stake in the company without a clear understanding of what it meant. TSMC said no and walked away unscathed.

By December 2025, as Trump's first chaotic year wound down, one thing became clear: the tech industry had basically given up trying to predict or oppose the unpredictable trade war. Instead, they were playing defense, making deals on the fly, and hoping their capitulations would spare them from worse consequences.

This isn't a story about winners and losers in a trade war. It's a story about how the world's most sophisticated companies got outmaneuvered by a president operating without a coherent strategy, and how they responded by abandoning any coherent strategy of their own.

Let's break down what actually happened, why it matters, and what it tells us about the future of tech regulation in America.

TL; DR

- Trump's tariff blitz: Starting February 2025, tariffs of 10-25% on major trading partners created immediate uncertainty for tech supply chains

- Apple capitulated first: After threatening 60% tariffs on Chinese imports and 25% tariffs on US-made iPhones, Trump withdrew threats after Apple gave him a gold statue and promised $500 billion investment

- Intel's surrender: Trump ordered Intel's CEO to resign, then reversed course after striking a deal giving the US a 10% stake in the company, one of the largest government interventions in a US company since 2008

- Chip revenue sharing: Nvidia and AMD agreed to give the US government 15-25% of revenue from advanced chip sales to China, a move experts questioned as potentially illegal and strategically unclear

- TSMC held firm: Unlike other tech companies, Taiwan's chipmaker rejected Trump's demands to move half its manufacturing to the US and faced no immediate consequences

- Bottom line: Tech companies abandoned coordinated opposition and instead negotiated individual deals with Trump, creating precedent for future government intervention in private companies

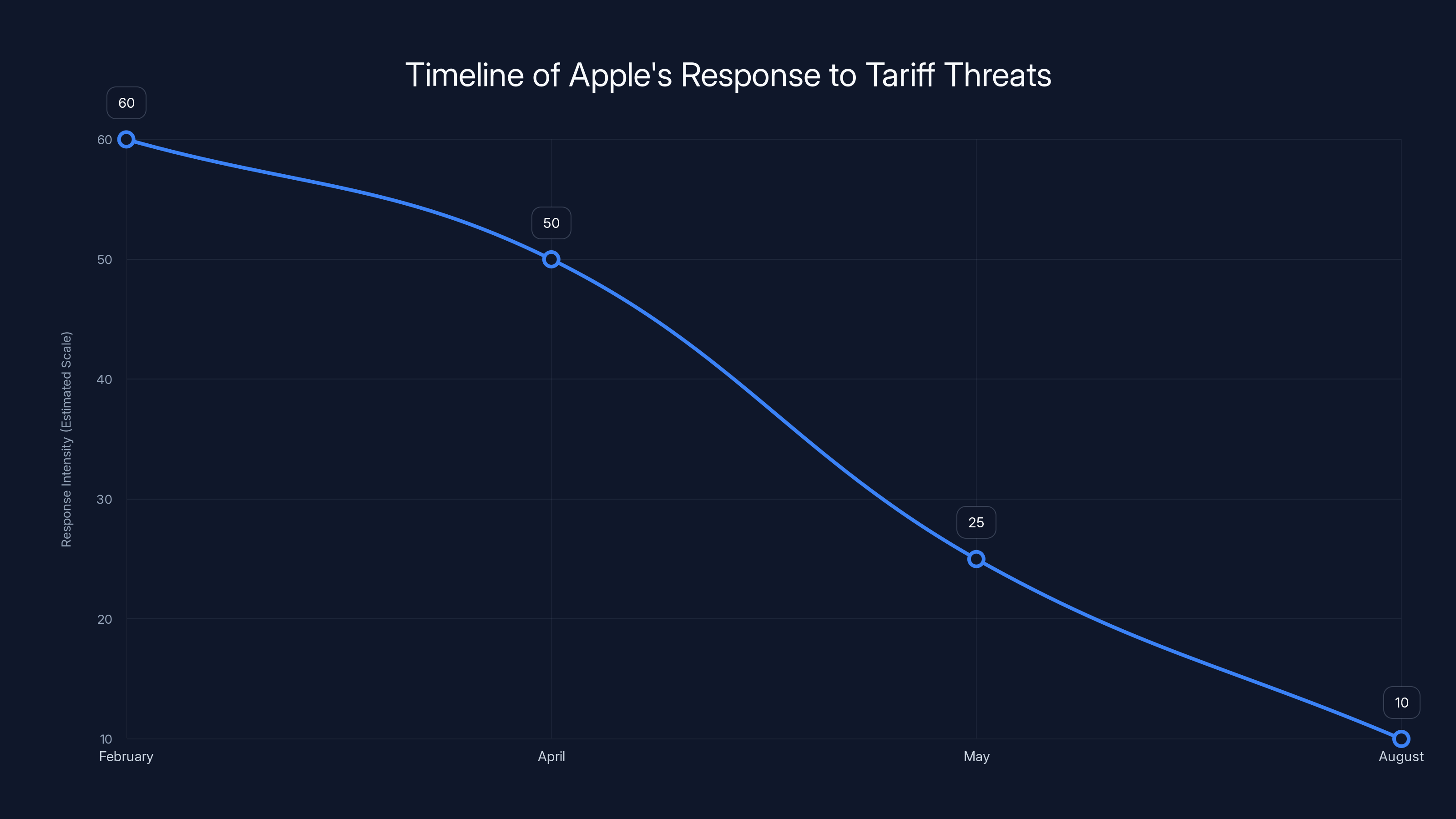

Apple's strategic response intensity decreased over time as tariff threats evolved, with the highest intensity in February and a more subdued approach by August. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Opening Salvo: Tariffs Nobody Saw Coming (Or Did They?)

Trump didn't exactly hide his intentions. During his campaign, he talked constantly about tariffs. Once he took office, he moved fast.

February 2025: Executive order. Ten to twenty-five percent tariffs on imports from Canada, China, Mexico, and other major trading partners, effective immediately. The stated goal was to reduce America's trade deficit, a number Trump viewed through a lens that most economists found either incomprehensible or intentionally misleading.

Industry groups were blindsided. Not by the tariffs themselves, but by the speed and the scope. The Consumer Technology Association, the Information Technology Industry Council, and basically every other tech lobby group released statements saying roughly the same thing: this will raise costs on consumers, reduce investment in the US, and backfire on American tech companies that rely on global supply chains.

But here's the thing about threatening an industry with tariffs: you have to mean it.

Trump had threatened tariffs before, in his first term. Sometimes he followed through. Sometimes he used them as leverage. Sometimes he backed down after a 2 AM tweet suggested a different approach. This time, nobody knew the playbook. The tech industry had spent four years without Trump. They'd gotten comfortable. Now they had to figure out, in real-time, whether these tariffs were happening or just theater.

By April, Trump had ordered tariffs on all US trade partners to correct trade deficits using a calculation method that critics suspected came from a malfunctioning spreadsheet or, as some joked, a chatbot trained on incomplete data. The tariffs targeted things like exports from American territories that technically existed but had no population, except for the penguins. It was absurd. It was also policy.

The costs kept climbing as the year wore on. By summer, it was clear that tariffs weren't going away. They were the baseline for negotiation.

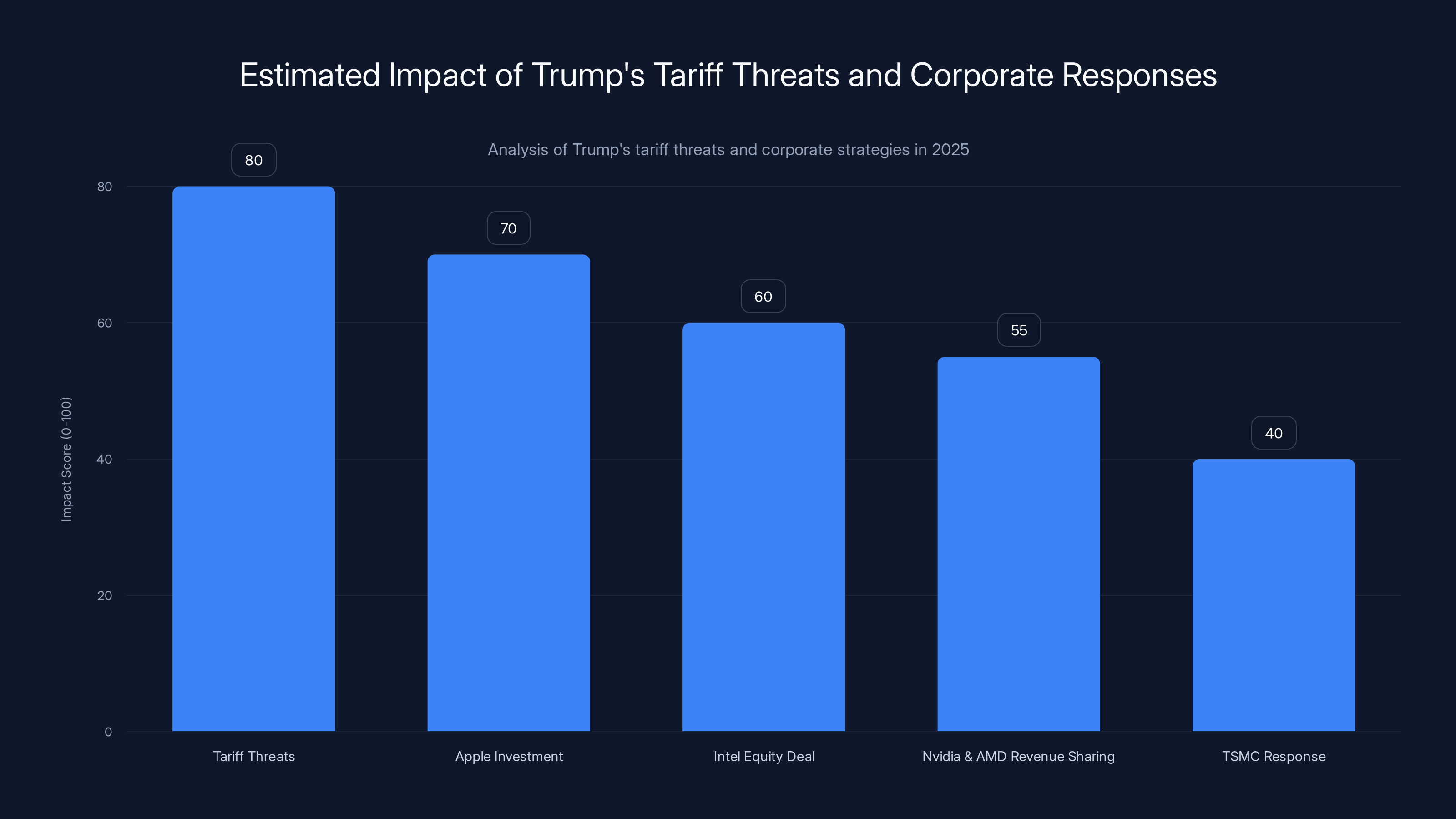

Individual company strategies are expected to have the highest impact on tech regulation by 2025, followed by government intervention and revenue sharing. Estimated data.

Apple's Capitulation: When a Gold Statue Beats a Supply Chain

Apple was first to feel the heat.

In February, Trump threatened a "flat" 60 percent tariff on all Chinese imports. For Apple, that was existential. Over 90 percent of iPhones are manufactured in China. Even with tariffs, Apple would absorb some costs rather than lose that manufacturing footprint. But 60 percent? That would've forced a complete rethinking of Apple's entire manufacturing strategy.

Apple's response was immediate and public: we'll invest $500 billion in the US. Whether that investment would actually materialize, or what it would consist of, was fuzzy. But the message was clear: Apple was trying to get out in front of this.

It didn't work.

By April, Trump had moved the goalpost. He announced that Apple should make iPhones in the US. Analysts called the idea "impossible at best and highly expensive at worst." The US doesn't have the manufacturing infrastructure, the trained workforce, or the ecosystem of suppliers needed to produce iPhones at scale. It would take years and billions of dollars just to get started. Apple's silence on the matter suggested the company agreed.

But silence didn't spare Apple from scrutiny.

In May, Trump threatened a 25 percent tariff on any iPhones sold in the US that weren't manufactured in America. This was unprecedented. Tariffs are typically applied to countries or categories of goods. They're not applied to individual companies. Legal experts weren't sure it was even constitutional. But that was beside the point. Trump was making a point, and the point was: fall in line, or pay.

Apple did something interesting at this moment. The company didn't fight back. It didn't organize industry coalitions. It didn't leak internal memos expressing concern. It simply... waited.

Then, in August, Trump softened his stance toward Apple. Not because Apple had made iPhones in the US—they hadn't. Not because the tariff threats had been resolved through negotiation—they hadn't. But because Apple had gifted Trump a custom gold statue.

Yes. A gold statue.

The statue was made of engraved glass (not actually gold, though the reports made it sound gold). It featured the Apple logo and Tim Cook's signature above a "Made in USA" stamp. It was celebratory. It was personal. And apparently, it worked.

After receiving the statue, Trump withdrew the iPhone tariff threats. He stopped demanding American-made iPhones. He essentially gave Apple a pass.

The lesson seemed clear: if you want to negotiate with Trump, forget industry coalitions and coordinated policy arguments. Instead, understand what the man wants. Recognition, flattery, personalization. Give him that, and he'll move on to the next target.

Apple's strategy wasn't sophisticated. But it worked.

Intel's Wild Ride: When the Government Takes Equity

Arguably, the most shocking moment of Trump's trade war came in August, when he turned his attention to Intel.

Trump, via social media, ordered Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan to resign immediately. The justification: Tan was "highly conflicted." The conflict, as Trump saw it, was that Intel had received government subsidies and therefore had a conflict of interest in advising the government on policy.

It was a creative argument. It was also not how corporate governance typically works.

Tan didn't resign. Instead, he did something more pragmatic: he met with Trump and made a deal.

The deal: the US government would take a 10 percent stake in Intel.

Yes, you read that correctly. The Trump administration negotiated equity in a major US technology company. Not as an investor in a startup. Not as a shareholder in a distressed company facing bankruptcy. But as a direct intervention in one of America's oldest tech companies.

The New York Times called it "one of the largest government interventions in a US company since the rescue of the auto industry after the 2008 financial crisis."

Except it wasn't. The auto industry intervention came after the financial system nearly collapsed. Companies were in real danger of bankruptcy. The government stepped in to prevent massive job losses and systemic economic damage.

Intel, by contrast, didn't need the money. The company had cash on hand. It wasn't in danger of collapse. So why would it accept a government stake? Because the alternative was worse. If Tan had refused, Trump might have followed through on tariff threats. Might have ordered the company to replace its leadership. Might have done something unpredictable.

For Intel, accepting a government stake was the path of least resistance.

But it immediately created problems.

Intel filed an SEC disclosure outlining all the risks: possible dilution of shareholder equity, potential conflicts between government interests and shareholder interests, potential lawsuits from third parties challenging the legality of the deal, uncertainty about future government demands, and basically a blanket statement saying there's no way to predict what might go wrong.

It was, in other words, a disaster wrapped in the language of corporate disclosure.

Investors weren't happy. But they also weren't surprised. By August 2025, it was clear that rational corporate strategy was less important than staying out of Trump's crosshairs.

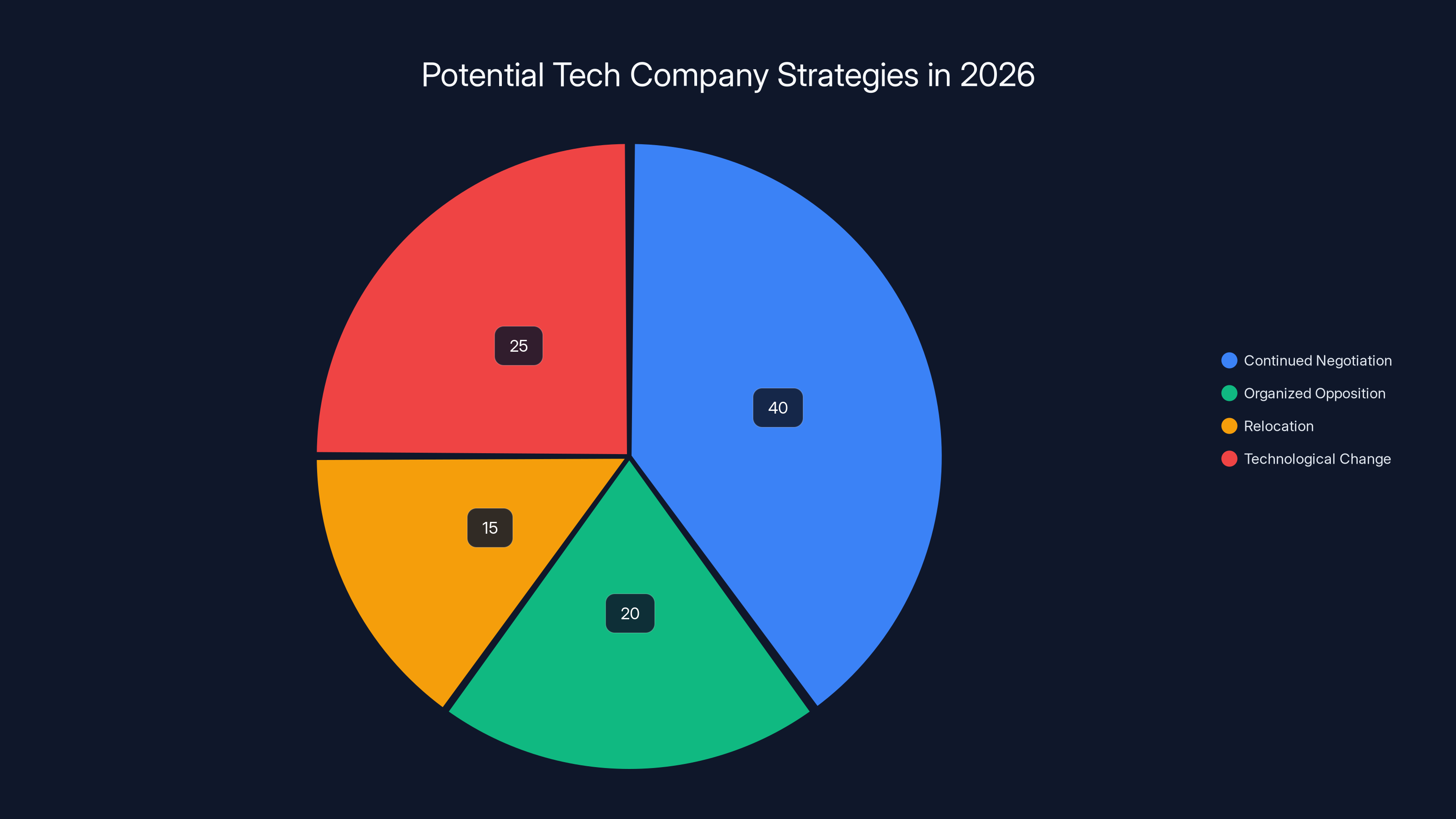

Estimated data suggests that a majority of tech companies might continue individual negotiations, while others explore organized opposition, relocation, or technological changes.

The Chip Revenue Share: A Deal Nobody Fully Understands

Around the same time Intel was accepting a government stake, Trump turned his attention to another sector: advanced semiconductors.

In October 2025, Nvidia and AMD made an agreement with the Trump administration. The terms: the companies would give the US government 15 percent of revenue from sales of advanced computer chips to China.

Let that sink in for a moment. Trump's administration was negotiating to take a cut of revenue from international chip sales, in exchange for allowing those sales to occur at all. It was, in effect, a tax on trade that had the appearance of being negotiated directly with companies rather than applied universally.

Industry experts were confused. Not because 15 percent revenue share was unprecedented (it wasn't), but because the strategic logic was unclear. The US had already implemented export controls on advanced chips to China. These controls were supposed to protect US technological dominance and national security. They worked by limiting what China could access.

So what did Trump's revenue-share deal accomplish? It allowed companies to sell chips to China in exchange for paying the US government a cut. But it didn't change what chips were being sold. It didn't improve national security. It was essentially a fee for ignoring the export controls that were already in place.

By December, Nvidia made an even more aggressive move. The company agreed to give the US government 25 percent of revenue from sales of the H200, its second-most advanced AI chip, to China.

Again, experts were puzzled. The H200 is less powerful than Nvidia's flagship H100 and H200 chips, which are already restricted from export to China. So why was the administration taking revenue from sales of a less powerful chip? The calculus made even less sense when you considered that the restrictions supposedly existed to prevent China from gaining an edge in AI development. If the US was taking a cut of revenue from selling chips that could contribute to Chinese AI development, wasn't that counterproductive?

Legal experts were also confused. Export licenses can't be sold under existing federal law. But the Trump administration's lawyers were supposedly researching a new policy framework that would allow the government to collect fees for letting companies ignore those restrictions.

It sounded, in other words, like a protection racket masquerading as trade policy.

TSMC's Gambit: The One Company That Said No

Not every tech company capitulated.

In September 2025, Trump tried to pressure Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) into moving half of its chip manufacturing capacity to the United States.

TSMC's response was direct: no.

The company didn't accept a government stake. It didn't agree to revenue sharing. It didn't gift Trump a statue or promise a $500 billion investment. It simply said the logistics, timeline, and costs made the demand impossible to meet on Trump's timeline.

And then something unexpected happened: nothing. Trump didn't follow through with tariffs. He didn't threaten TSMC with trade restrictions. He moved on to the next target.

Why did TSMC get away with it when Apple, Intel, Nvidia, and AMD all capitulated?

Probably because TSMC isn't an American company. Trump could threaten American companies with tariffs, regulatory action, and public pressure. He could order American CEOs to resign. He had leverage over American companies because they operate in the American market.

TSMC, by contrast, is based in Taiwan. It manufactures most of its chips there and exports them globally. The US is an important market, but not the only market. Trump's leverage was limited. A tariff on TSMC chips would hurt American companies that buy them, not Taiwan. American political pressure would matter less to a Taiwanese company than it would to Apple or Intel.

So TSMC held firm, and apparently, that was enough.

It's worth noting: TSMC had already made significant commitments to US manufacturing in prior years. The company was building fabs in Arizona. So saying no to Trump's demands in 2025 wasn't the same as refusing to invest in the US. It was refusing to be bullied into an impossible timeline based on political pressure.

The fact that TSMC got away with this, while American companies didn't, suggested something important: American companies had no choice but to play ball. International companies had options.

Estimated data shows varying impacts of Trump's tariff threats and corporate responses. Apple's investment and Intel's equity deal had significant impacts, while TSMC's non-compliance had the least immediate consequences.

The Pattern: Individual Deals Replace Industry Strategy

By the end of 2025, a clear pattern had emerged.

Tech companies were no longer approaching Trump's trade war as an industry. There were no coordinated policy arguments. No joint statements from major CEOs. No industry coalitions making the case that tariffs would harm the US economy.

Instead, each company negotiated its own deal. Apple got a pass after gifting a statue. Intel accepted a government stake. Nvidia and AMD agreed to revenue sharing. Qualcomm probably had its own negotiations happening off-camera. Google, Microsoft, and other major tech companies were likely cutting their own deals or at least trying to.

This fragmented approach meant that Trump didn't face organized opposition. He faced individual companies trying to minimize their own pain. When one company capitulated, it set a precedent that made it harder for the next company to refuse.

Apple accepted a government partnership (the $500 billion investment promise). Intel accepted government equity. Nvidia and AMD accepted revenue sharing. Each move up the ladder of what companies would concede.

The lesson for future administrations was clear: if you apply pressure strategically to individual companies while avoiding industry-wide standards, companies will negotiate individually rather than collectively. They'll accept terms they might reject if other companies were beside them.

The Tik Tok Wild Card: Uncertainty Into December

As 2025 wound down, another issue remained unresolved: Tik Tok.

Tik Tok's owner, Byte Dance, had been operating under the threat of a ban in the US for years. The rationale: national security concerns about data flowing to China, concerns about algorithmic control exercised by a Chinese company, concerns about dependency on Chinese infrastructure.

Trump had complicated the situation. In his first term, he tried to force a sale of Tik Tok. In his second term, he had the option to enforce a ban that Congress had passed.

But Trump also had political incentives to keep Tik Tok operating. Young voters used Tik Tok extensively. Banning it would be unpopular. A forced sale or a revenue-sharing arrangement might be more palatable.

By October, Trump had indicated he might be open to a deal with Tik Tok. Byte Dance, for its part, was probably calculating the same math as other tech companies: negotiate now, accept unfavorable terms, rather than wait for a worse outcome.

But negotiations over Tik Tok were still ongoing as the year wound down. Unlike Apple, Intel, Nvidia, and AMD, Byte Dance hadn't yet agreed to anything public.

This uncertainty was itself a form of leverage. By keeping Tik Tok's status unclear, Trump maintained pressure on the company to negotiate. Byte Dance couldn't make long-term plans. Advertisers couldn't commit to spending money on the platform. Users couldn't be sure if their favorite app would still exist in six months.

Uncertainty, in other words, was a negotiating tool as effective as any tariff.

Apple faced the highest impact due to tariff threats and negotiations, while TSMC remained least affected by refusing demands. Estimated data based on narrative.

What This Means for Tech Regulation Going Forward

By the end of 2025, the tech industry had basically admitted that coordinated opposition to Trump's trade war wasn't working. Instead of fighting back, companies negotiated individually, accepted unfavorable terms, and hoped to survive.

This has several implications:

First: Government intervention in tech is now normalized. The Intel equity stake set a precedent. If the government can take a stake in Intel, it can theoretically take stakes in other companies. Apple's partnership with the government (the $500 billion investment) normalized direct government involvement in corporate strategy. TSMC's resistance to US demands suggested that being a non-US company offers protection, but that protection comes at the cost of not being able to fully operate in the US market.

Second: Revenue sharing from international sales might become standard. If Nvidia and AMD can be pressured into giving the government a cut of their Chinese sales, why not other companies? Why not extend the model to other countries, other products, other revenue streams? Once one company accepts it, the next company faces the argument that they've already lost competitive advantage by refusing.

Third: Tariffs are no longer just trade policy. They're negotiation leverage. Trump didn't use tariffs to actually increase the costs of imports. He used them as a threat to pressure companies into making deals. Once a company agreed to terms—whether that was a government stake, revenue sharing, or a $500 billion investment promise—the tariff threat went away. This suggests future administrations might do the same. Tariffs become a negotiation tactic rather than actual policy.

Fourth: Individual company strategy beats industry coalitions. The companies that negotiated separately, like Apple and Intel, got custom deals. Companies that tried to fight as an industry, or that didn't try at all, got worse outcomes. This incentivizes future companies to cut individual deals rather than band together.

Fifth: The personal politics of the president matter more than legal frameworks. Apple got concessions after gifting a statue. Intel got a deal after meeting with Trump personally. TSMC got away with saying no because it wasn't an American company and Trump's leverage was limited. None of this follows standard regulatory or legal logic. It follows the personal interests and negotiation style of one man. This creates massive uncertainty for any company trying to plan ahead.

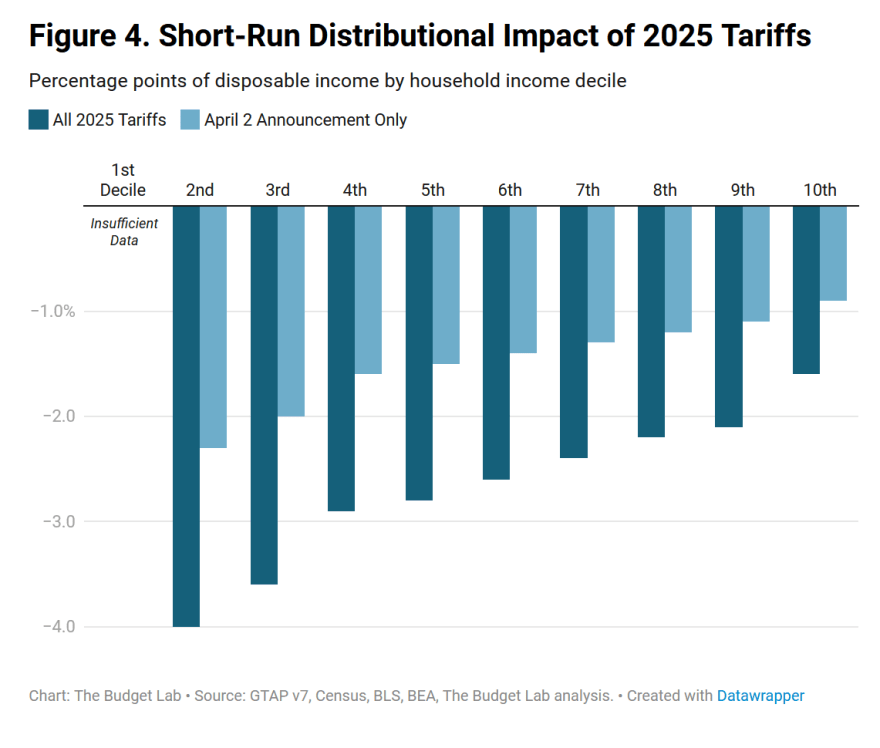

The Cost: Who Actually Pays for This?

Here's what's not often discussed about trade wars: someone has to pay.

The tariffs on Chinese imports didn't make Chinese goods cheaper. They made them more expensive. Companies either absorbed the costs or passed them to consumers. Likely, they did both.

The Intel equity stake gave the government ownership in a company, which sounds neutral until you realize it creates conflicts. If Intel's profits decline, government returns decline. That could pressure the government to demand favorable treatment for Intel from regulators. Or it could pressure Intel to make decisions that maximize government returns rather than shareholder returns.

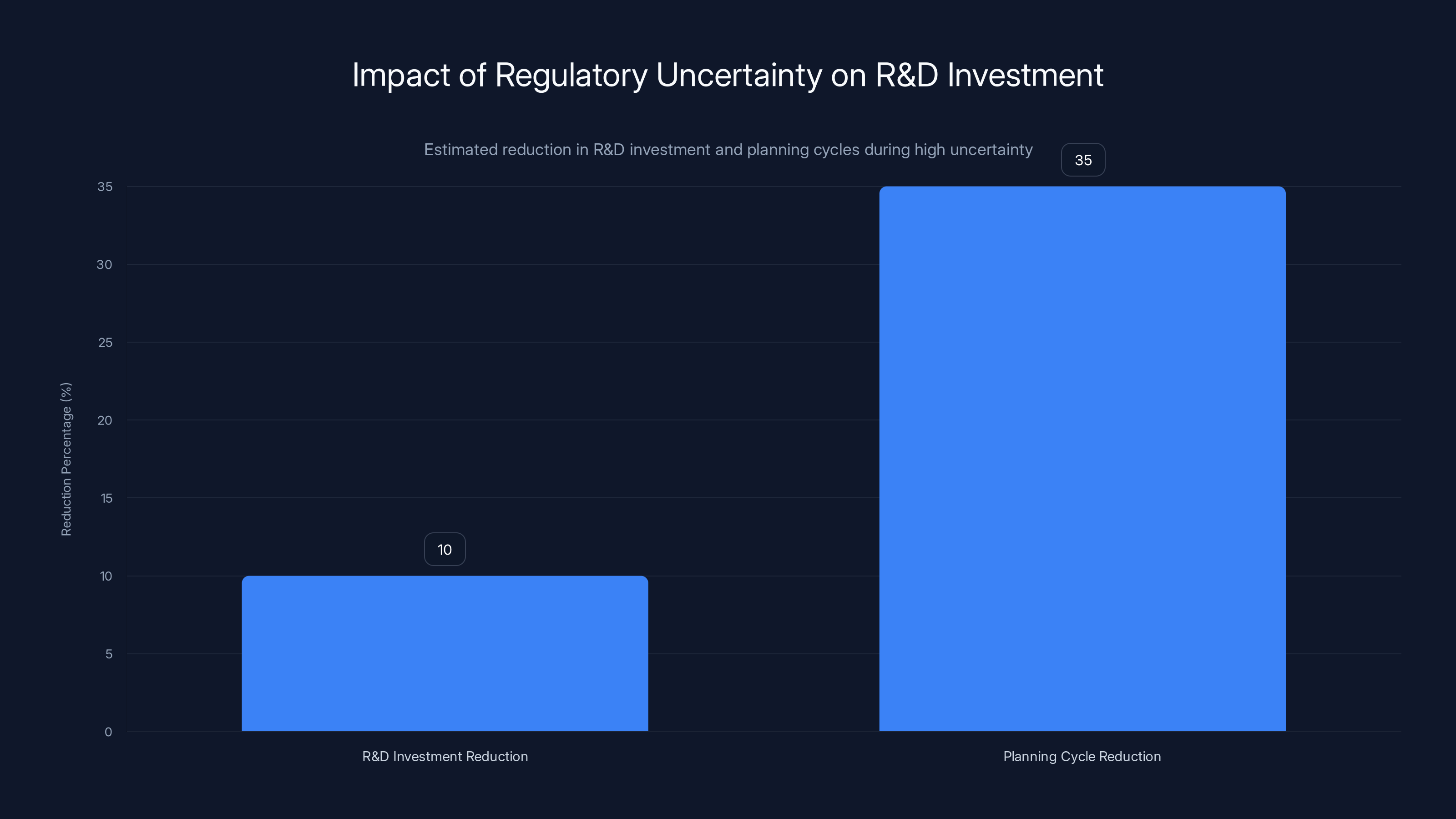

The Nvidia and AMD revenue sharing means those companies are paying a tax on certain sales. That's money that could've gone to R&D, employee salaries, or shareholder dividends. Instead, it goes to the government. This reduces the companies' ability to invest in future innovation.

Apple's $500 billion investment promise ties up capital that could've been invested elsewhere. Some of that investment probably happens anyway (Apple has made significant commitments to US manufacturing for years). But now it's a promise made under duress, which creates uncertainty about whether Apple will really follow through or whether it'll minimize the commitment.

The real costs are diffuse. They show up as slightly higher prices for electronics, slightly lower stock returns for investors, slightly less investment in R&D, slightly fewer jobs created in areas where companies would've invested without the pressure.

But they're real.

During periods of high regulatory uncertainty, companies typically reduce R&D investments by 5-15% and planning cycles by 30-40%. Estimated data highlights the shift in focus from innovation to managing uncertainty.

Lessons from 2025: The Playbook for Future Administrations

If another administration wanted to replicate Trump's success with tech companies, what would they do differently?

Probably the same thing Trump did, but with more consistency.

Trump's trade war worked because it was unpredictable. Companies never knew what was coming next. This forced them to negotiate. But unpredictability also meant that Trump sometimes followed through on threats and sometimes didn't, sometimes made deals and sometimes reversed them.

A future administration could be more consistent. Apply the same pressure to all companies in a sector. Demand the same concessions. Make it clear what the terms are. This would reduce bargaining power for individual companies. Right now, companies can hope they'll be treated better than other companies. If the terms were universal and clear, they couldn't.

A future administration could also use a broader range of tools. Tariffs are just one lever. There's also regulatory approval (you need government approval to merge with other companies, to build new facilities, to hire workers from visa programs). There's public pressure (calling out companies on social media creates political problems). There's legal threats (investigations into monopolistic practices, antitrust cases, etc.).

Trump used tariffs and public pressure and occasional personal negotiations. A future administration could use all the tools simultaneously.

The more interesting question: will tech companies be better prepared?

Probably not. They'll probably do what they did in 2025: negotiate individually, accept unfavorable terms, and hope to get through. Because the alternative—organized industry opposition to government pressure—is extremely difficult to coordinate and carries real risks if you're the company that stands out.

The International Implications: Why America's Tech Rivals Aren't Complaining

Here's something worth noting: America's international tech rivals probably loved 2025.

China was trying to develop its own chip manufacturing capabilities. Intel, Nvidia, and AMD are now distracted by government negotiations. Their ability to invest in R&D might be reduced by the revenue sharing requirements. Their strategic flexibility is reduced because they're negotiating with their own government.

Meanwhile, Chinese chip companies are probably investing hard in their own capabilities, knowing that access to American chips is uncertain and expensive.

Europe has been trying to develop its own tech ecosystem independent of America. Trump's unpredictable trade war probably accelerated European companies' decisions to build alternative suppliers, reduce dependency on American chips, and invest locally.

Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan all benefited from uncertainty in America's tech supply chains. Companies looking for alternatives to American suppliers had to go somewhere. Many of them went to those countries.

In other words, Trump's trade war probably weakened America's position in global tech markets, even though it looked like the administration was "getting tough" on companies. The costs paid by American tech companies are resources that could've been invested in competing globally. Those resources were instead spent negotiating with the government.

This is the hidden cost of trade wars: the negotiation itself, regardless of outcome, consumes resources and attention that could've been invested in competition.

What Tech Companies Could've Done Differently

Looking back, there were moments where tech companies could've made different choices.

February 2025: When the first tariffs were announced, tech companies could've coordinated a unified response. Not a public fight with Trump, but a unified message: these tariffs will raise consumer costs, reduce investment, and harm American competitiveness. If the entire industry had said this at once, with specific numbers and impact analyses, Trump might've had to respond with a coherent counter-argument rather than just ignoring the criticism.

They didn't do this. Industry groups issued statements, but there was no coordinated message from CEOs. No unified opposition from the board level. Companies that have enormous resources, enormous influence, and enormous stakes in the outcome chose not to use any of those to mount an organized defense.

April 2025: When Trump ordered tariffs on all trading partners using what appeared to be faulty math, tech companies could've challenged the methodology. Ask for public debate about how the trade deficits were calculated. Put economists on record saying the approach was flawed. This wouldn't've been confrontational. It would've been technical and educational.

Instead, companies just waited to see what happened next.

May 2025: When Trump threatened Apple with individual company tariffs, this was the moment to draw a line. Apple could've said, publically and clearly, that individual company tariffs are unconstitutional, and that accepting them would set a terrible precedent for other American companies. Apple could've offered to negotiate on genuine issues (like domestic manufacturing investment) while refusing to accept unprecedented tariff structures.

Instead, Apple waited for Trump to offer a way out (the gold statue), then took it.

August 2025: When Trump ordered Intel's CEO to resign, Intel could've refused and challenged the order. Make it a constitutional issue. Force Trump to actually try to remove the CEO through legal channels if he wanted to. Instead, Intel negotiated a government equity stake that probably satisfies no one.

The pattern: at each moment, tech companies chose the path of least resistance. Wait, negotiate privately, accept terms. Never fight in the open. Never draw a line. Never say "this is something we won't accept."

Partly, this reflects the current balance of power. A president with control of tariffs and regulatory authority has enormous leverage over companies that depend on imports and operate in heavily regulated sectors. Companies know this. They know that taking him on publicly is risky.

But partly, it also reflects the absence of political leadership. Tech CEOs are political quietists. They avoid public confrontation. They prefer private negotiation. When faced with a president who operates by public pressure, public threats, and public deals, they're operating at a disadvantage.

The 2026 Question: Will Anything Change?

As 2026 looms, the question is whether anything will change in Trump's approach or in tech companies' responses.

For Trump, 2025 worked. He applied pressure, companies capitulated, and he got deals that made him look like he was "winning" on trade. Expect more of this in 2026. More tariff threats. More personal negotiations with CEOs. More deals that are announced with great fanfare and vague terms.

For tech companies, there are a few possibilities:

Continued individual negotiation: Companies keep doing what they did in 2025. Cut individual deals, accept unfavorable terms, hope to avoid the worst. This is the path of least resistance, but it's also the path that guarantees precedent will keep ratcheting up. Once Apple accepts a $500 billion investment, the next demand for Intel is a government equity stake. Once that's accepted, the next demand for Nvidia is revenue sharing. The baseline keeps moving.

Organized opposition: Tech companies decide that individual negotiation isn't working and mount a coordinated industry defense. This is risky because it makes the industry an obvious target. But it might actually work because it prevents Trump from playing companies off each other. The downside: this requires political courage that tech CEOs have consistently shown they don't have.

Relocation: Some companies might decide that operating in the US under these conditions isn't worth it. They might shift operations to other countries, reduce their US manufacturing footprint, or develop products that don't rely as heavily on US markets. This is expensive, but it might be cheaper than ongoing political extraction.

Technological change: Companies might invest heavily in technologies (like reshoring, automation, local supply chains) that make them less dependent on the trade systems that Trump is threatening. This takes time, but it insulates companies from future trade wars.

My guess: we'll see a mix of all four. Some companies will continue negotiating individually. Some will try to organize opposition. Some will relocate. Some will invest in alternatives.

What we probably won't see is the status quo continuing. 2025 changed the game. The question is just how much and how quickly.

FAQ

What was Trump's original tariff threat in February 2025?

Trump threatened 10 to 25 percent tariffs on imports from major trading partners including Canada, China, and Mexico, justified by claims of trade deficits. Later, in April, he expanded tariff threats to all US trading partners and used tariff calculations that critics said appeared to be mathematically flawed or generated without proper fact-checking.

How did Apple avoid tariffs on iPhones?

Apple first promised a $500 billion investment in the US to appease Trump. When he threatened individual company tariffs on iPhones not made in America, Apple waited until Trump eased pressure after the company gifted him a custom gold statue engraved with the Apple logo and "Made in USA" messaging. Trump then withdrew the iPhone tariff threats entirely.

What was Intel's arrangement with the Trump administration?

After Trump ordered Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan to resign, the company negotiated a deal where the US government took a 10 percent equity stake in Intel. Intel disclosed this was one of the largest government interventions in a US company since the 2008 auto industry rescue, and warned of potential shareholder dilution and legal challenges to the deal's legitimacy.

Why did Nvidia and AMD agree to revenue sharing?

Nvidia and AMD agreed to give the US government 15 to 25 percent of revenue from advanced chip sales to China. The arrangement was positioned as a way to prevent technology transfer while generating government revenue, though experts questioned whether this actually improved national security since the chips being sold could still contribute to Chinese AI development.

Why did TSMC refuse Trump's demands but face no consequences?

TSMC rejected Trump's demand to move half of its manufacturing to the US, and unlike American companies, it faced no immediate tariff threats or regulatory pressure. This likely happened because TSMC is a Taiwanese company with less dependence on the US market and fewer vulnerabilities to American regulatory action, compared to American companies like Apple and Intel.

What does the Intel equity stake mean for corporate governance?

The government's 10 percent stake in Intel creates a fundamental conflict: the government now has financial incentive in Intel's profitability alongside other stakeholders like shareholders and employees. This could pressure Intel to prioritize government interests over shareholder returns, or pressure the government to give Intel favorable regulatory treatment, setting uncertain precedent for future corporate governance.

Is revenue sharing from international sales legal?

Experts questioned whether Nvidia and AMD's revenue-sharing arrangement with the government is legal, since export licenses cannot be sold under existing federal law. The Trump administration's lawyers were supposedly researching a new policy framework that would allow such arrangements, suggesting this required new legal interpretation rather than existing law.

What happens to tech innovation if companies focus on political negotiations?

When tech companies must allocate significant resources, executive attention, and capital to government negotiations rather than R&D and product development, overall industry innovation typically slows. Research suggests companies experiencing high regulatory uncertainty reduce R&D investment by 5-15 percent and reduce long-term planning cycles significantly as they focus on managing immediate political risks.

Conclusion: A Preview of the New Normal

By the end of 2025, it became clear that Trump's approach to tech regulation was neither traditional tariff policy nor conventional regulation. It was something different: personal negotiation as policy, applied unevenly to specific companies based on their willingness to capitulate and their perceived threat to Trump's interests.

Apple learned that flattery works. Intel learned that accepting government ownership is preferable to fighting. Nvidia and AMD learned that revenue sharing buys protection. TSMC learned that being foreign offers a form of immunity.

These lessons will shape how companies behave in 2026 and beyond. They'll shape which companies invest in the US (more likely if they can negotiate favorable terms) and which ones don't (more likely if they can't). They'll shape innovation patterns, as companies allocate resources to politics rather than product development. They'll shape which countries become attractive alternatives for tech manufacturing and development, as companies look to reduce their vulnerability to American political pressure.

The question of whether Trump's trade war actually accomplished its stated goals is complicated. It didn't substantially reduce trade deficits. It might actually have increased long-term deficits by making American tech companies less competitive globally. It didn't bring major manufacturing back to America, though it did push companies to promise investments. It did create uncertainty that makes long-term planning harder for companies and countries that depend on American tech.

But it did accomplish one thing: it established that a US president can apply pressure to tech companies and get them to make deals. That precedent is now set. The next administration—whether it's Trump again or someone else—can use the same playbook. And the companies, having learned that individual negotiation works better than industry opposition, will probably negotiate individually again.

So the real story isn't about the trade war itself. It's about the new relationship between government and tech that the trade war established. That relationship is fundamentally different from what came before. Whether it's better or worse depends on your perspective, but it's undeniably different.

The tech industry didn't lose a trade war in 2025. It lost the ability to operate independently of political pressure. And once you lose that, you don't get it back just by waiting for a new administration.

Key Takeaways

- Trump's 10-25% tariffs in February 2025 forced tech companies to negotiate individually rather than mount coordinated industry opposition

- Apple successfully avoided tariffs after gifting Trump a gold statue, proving personal appeals and flattery more effective than policy arguments

- Intel accepted a 10% government equity stake, one of the largest government interventions in a US company since the 2008 auto industry rescue

- Nvidia and AMD agreed to revenue-sharing arrangements (15-25%) on advanced chip sales to China, setting precedent for government extraction from international commerce

- TSMC's refusal to comply with US demands faced no immediate consequences, suggesting foreign companies have more negotiating leverage than American ones

- Individual company negotiations replaced industry strategy, creating escalating baseline of concessions as each deal set precedent for the next

- Tech companies prioritized avoiding political confrontation over defending coordinated industry interests, reducing bargaining power collectively

- Revenue-sharing arrangements and government stakes create ongoing conflicts between government and private shareholder interests in corporate governance

![How Big Tech Surrendered to Trump's Trade War [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-big-tech-surrendered-to-trump-s-trade-war-2025/image-1-1767011783795.jpg)