The Invisible Constraint Crushing AI Infrastructure

Everyone's talking about GPUs. The headlines scream about AI chips, processing power, and computational throughput. But there's a problem with that narrative. It's incomplete.

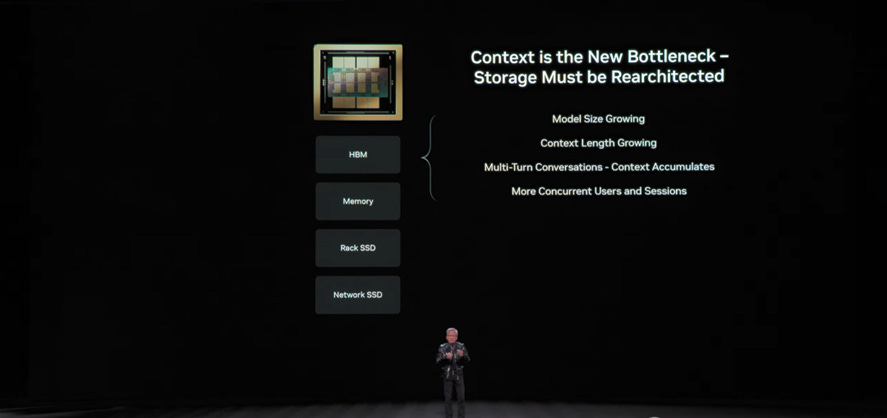

The real bottleneck in AI isn't whether your GPU can crunch numbers fast enough. It's whether your system has enough memory to hold the data those GPUs need to process. As highlighted by TechRadar, this distinction matters more than you'd think. It's reshaping how companies build data centers, how engineers deploy local AI models, and ultimately, whether cloud service providers actually make money from their massive GPU investments. Storage capacity isn't just a supporting role in AI infrastructure—it's become the foundational constraint that determines what's even possible.

We're at an inflection point. Cloud service providers have poured over $200 billion into GPU infrastructure in recent years. But here's the uncomfortable truth: they're not making money directly from GPUs. The money comes from inference—and inference is almost entirely constrained by storage. You can have the fastest GPU on Earth. If it's starving for data, that speed is worthless.

This is forcing a recalibration across the entire AI hardware ecosystem. Massive SSDs are entering production. NAND flash manufacturers are pushing toward higher densities. Startups and established players are experimenting with new architectures to bridge the gap between slow storage and fast compute. Some are even talking about integrating NAND directly into GPU packages—though not everyone thinks that's a good idea.

To understand where this is heading, we need to pull back from the hype cycle and examine the actual physics and economics of AI systems. We need to understand why memory limitations show up everywhere, from your laptop running a local language model to hyperscale data centers running inference for millions of users. And we need to understand what solutions are actually being built to solve this problem.

TL; DR

- Storage, not compute, is the bottleneck: GPUs are idle waiting for data most of the time in AI workloads, not limited by processing capacity, as noted by HPCwire.

- Time to First Token matters: Users won't tolerate latency above 10 seconds; NAND flash solutions can dramatically improve this metric.

- 244TB SSDs are coming: Phison and others are building extreme-capacity drives to handle hyperscaler inference demands.

- Modular beats integrated: Putting NAND directly into GPUs creates endurance problems that make entire expensive cards disposable.

- CSP profit = storage capacity: Cloud providers' revenue model depends on storage scaling, not raw GPU count, as discussed in The Motley Fool.

Estimated data shows that as storage capacity increases, CSP revenue potential grows significantly, highlighting storage as a key factor in profitability.

Understanding Why Memory Is Actually the Constraint

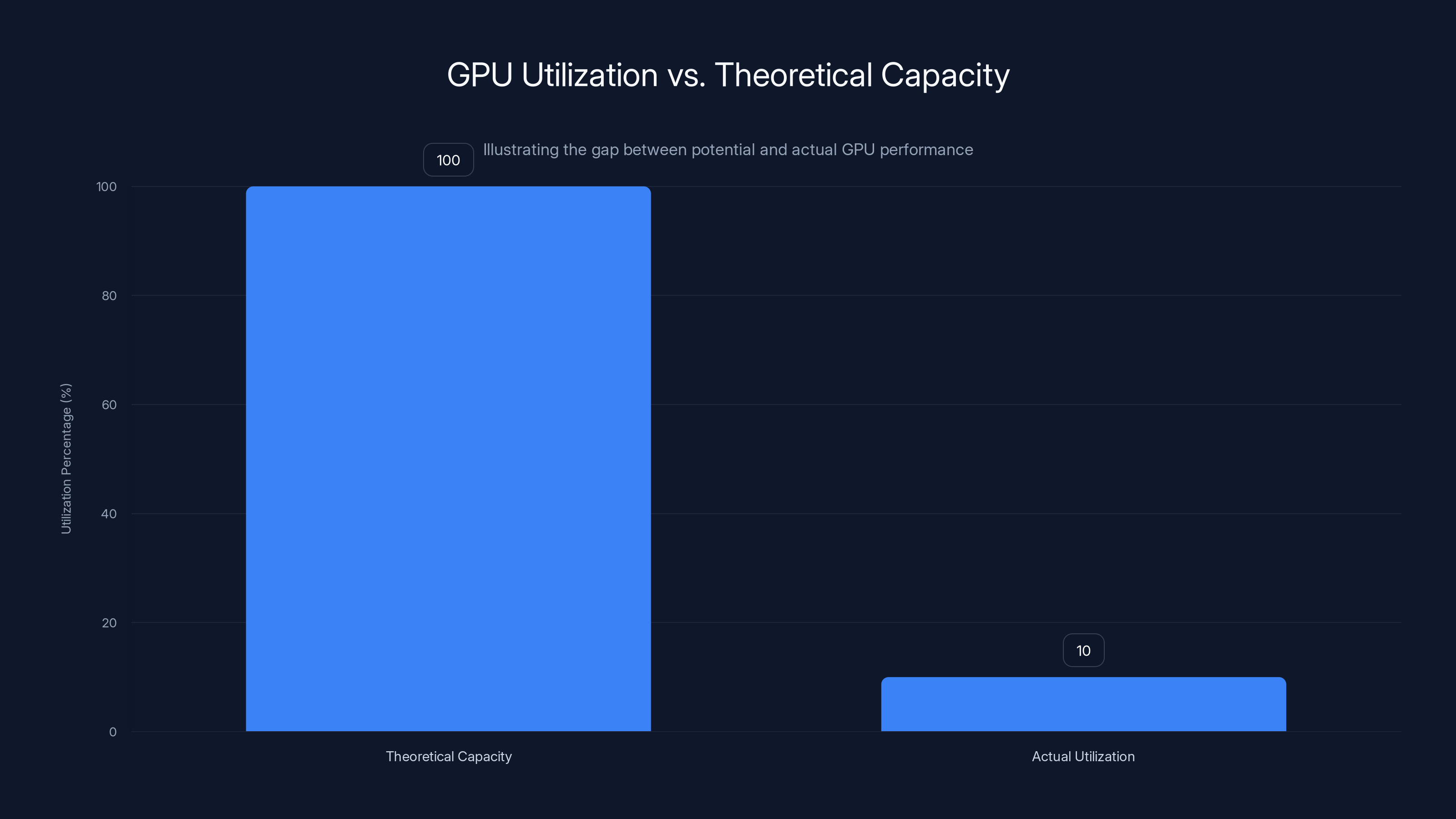

Let's start with the most counterintuitive insight: your GPU probably isn't doing much right now.

When you think about AI inference, you imagine a GPU processing data at peak speed. In reality, modern GPUs spend a shocking amount of time waiting. They're waiting for data to load from storage. They're waiting for the next batch of inputs. They're waiting for memory management operations to complete.

The gap between what a GPU could do and what it actually does is enormous. A top-tier GPU might be capable of performing 1,000 trillion floating-point operations per second (that's a petaflop). But if you're feeding it data from conventional storage, you're nowhere close to that theoretical peak. You're hitting something closer to 10% of maximum utilization. The rest of the time, the GPU is just... idle.

This isn't a GPU problem. It's a memory problem.

Consider what happens when you run a language model. The model itself—the weights, the parameters, everything that defines how the model behaves—needs to sit in memory where the GPU can access it quickly. For large models, this is measured in dozens of gigabytes or even terabytes. Then you have the input data. Then you have intermediate computations. Then you have the cache of previous tokens that helps the model generate the next token faster.

All of this needs to be accessible with minimal latency. DRAM is fast, but it's expensive and limited. A high-end GPU might have 80GB of VRAM. That sounds like a lot until you're trying to load a 400-billion-parameter model. Suddenly, you're out of memory. The system crashes, or you have to resort to techniques that drastically slow down processing.

This is why companies buy multiple GPUs. Not for more compute—they don't need it. They buy them for the extra VRAM. A GPU that's 90% idle is still cheaper than having your entire inference pipeline stall because you ran out of memory.

That's wasteful. And it's not even the worst part.

Flash-as-memory and TTFT optimization have the highest estimated impact on improving AI inference performance, followed closely by addressing VRAM limitations. Estimated data.

The Rise of Flash as Memory Expansion

When you realize the bottleneck is memory, not compute, the solution becomes obvious: expand your memory pool. But DRAM expansion hits physics limits. You can only stuff so much onto a GPU. Adding extra GPU cards for memory is wasteful and expensive.

Enter NAND flash storage. It's slower than DRAM by orders of magnitude. But it's available in massive quantities—terabytes, not gigabytes. It's cheap. And it's getting faster every year.

The idea is simple: use high-capacity SSDs as a memory expansion layer. When your GPU needs data that isn't in VRAM, instead of stalling or swapping to system RAM, it can pull from the SSD layer. The latency penalty is real—we're talking microseconds instead of nanoseconds—but for many workloads, it's acceptable. And the capacity benefit is enormous.

This is what companies are calling flash-as-memory or memory expansion architectures. You're not replacing DRAM with SSDs. You're augmenting it. You're creating a hybrid memory hierarchy that lets you keep expensive, fast memory for the working set while pushing everything else to cheap, large storage.

The practical benefit is radical. Suddenly, a single GPU with 80GB of VRAM can effectively work with 80GB of fast memory plus several terabytes of slower—but still acceptable—storage. The GPU doesn't have to idle waiting for data that's on the SSD. The data is there, available, waiting to be pulled.

This changes everything about how you architect an AI system. You stop buying multiple GPUs for memory aggregation. You stop overprovisioning compute that sits idle. You focus on actual processing needs.

But there's a catch: latency variability. If your SSD access is inconsistent, your inference performance becomes unpredictable. Responsiveness degrades. This is where extreme-capacity SSDs become important—they're not just bigger, they're optimized for the access patterns that AI workloads demand.

The Time to First Token Problem

There's a metric that matters far more than you'd expect in AI systems: Time to First Token (TTFT).

It sounds technical. It's actually about user experience.

When you prompt a language model, there's a delay before the first output appears. During this delay, nothing is happening—at least from the user's perspective. The model is processing context, warming up memory, preparing the computation. Then the first token arrives, and streaming begins.

That initial delay is TTFT. And it's a user experience killer.

If TTFT is 2 seconds, users feel like the system is responsive. It's fast. They'll wait. If TTFT is 10 seconds, users think the system is broken. They stop using it. The model might eventually produce perfect output, but nobody waits that long.

This is why TTFT is obsessed over in production AI systems. It's not a compute metric. It's a user experience metric. And it's almost entirely driven by how quickly you can move data through your memory hierarchy.

With local inference (running a model on your personal machine), TTFT is particularly brutal. You're loading a multi-gigabyte model from disk into RAM, preparing cache structures, and generating the first token. If you're using a conventional hard drive or a slow SSD, this can easily hit 60+ seconds. That's not a system anyone will actually use.

Flash-based memory expansion helps here dramatically. But there's an even smarter approach: KV cache management.

In transformer-based language models, generating each token requires computing something called the Key-Value (KV) cache. This cache contains precomputed information from all previous tokens in the conversation. It's huge. For a 70-billion-parameter model maintaining context about a 4,000-token conversation, the KV cache alone can be tens of gigabytes.

Most systems recompute this cache from scratch every single time. It's wasteful. Imagine a doctor who forgets every patient's medical history and recomputes their entire file from original documents every visit. That's what's happening in most AI inference systems.

A smarter approach: store frequently accessed KV cache on fast storage (or even faster SSDs). Retrieve it when needed. The computational savings are enormous. Users who ask similar questions repeatedly suddenly get dramatically lower TTFT on subsequent queries because the system doesn't have to recompute everything.

This is a concrete example of why storage capacity isn't just important—it's the actual limiting factor. Better compute doesn't help if the system is waiting on data that's trapped in slow storage.

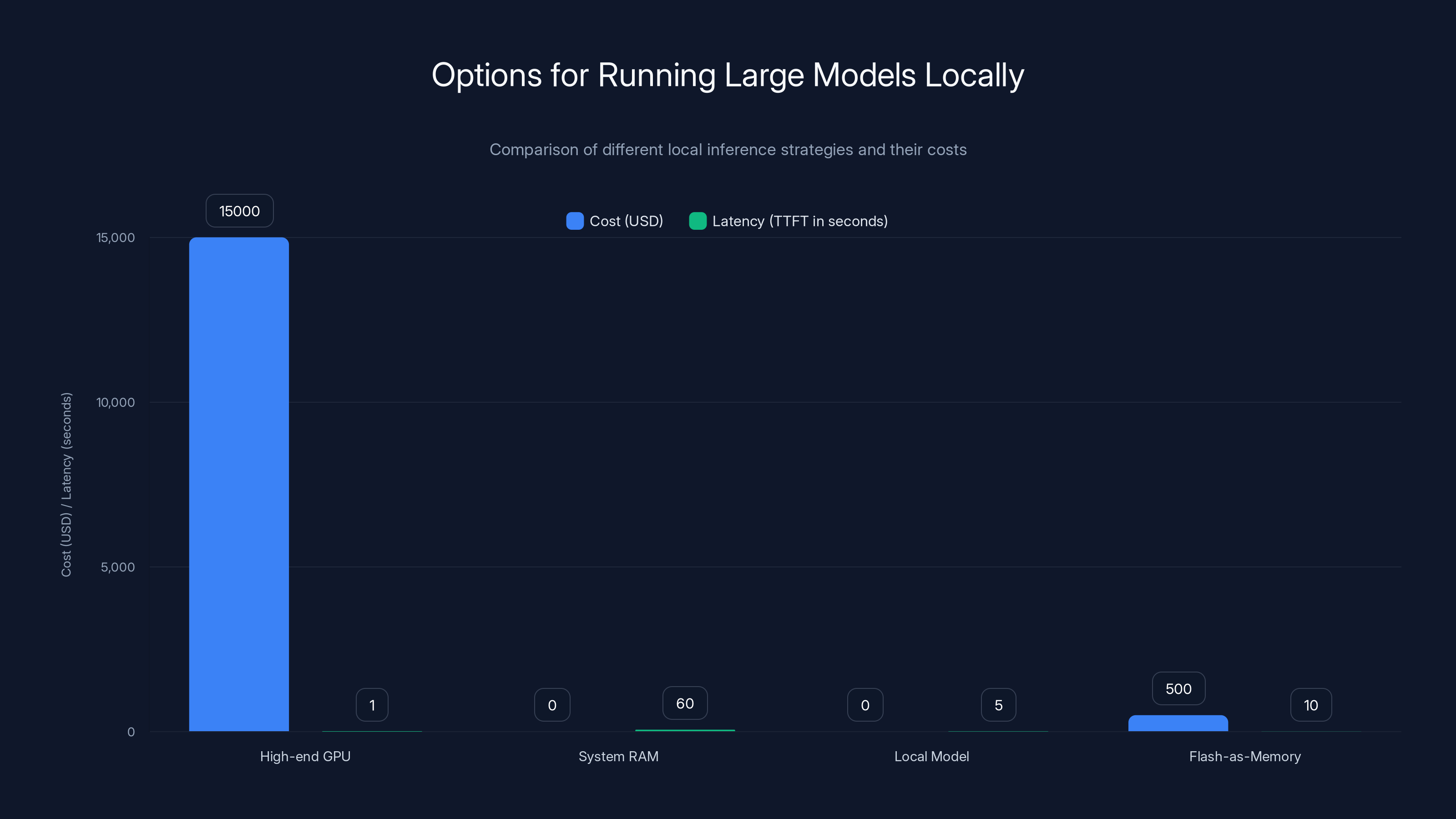

Using a high-end GPU is costly but offers low latency. Flash-as-memory solutions provide a balance between cost and latency, making local inference more practical. Estimated data.

DRAM Is Expensive. Storage Is Abundant.

The economics are relentless.

DRAM costs roughly

High-capacity enterprise SSDs cost roughly

The math is absurd. Storage is 10x cheaper per gigabyte than DRAM. It's not close.

Given that price disparity, the question isn't whether to use storage for memory expansion. It's why you wouldn't.

The only trade-off is latency. DRAM latency is measured in nanoseconds (billionths of a second). SSD latency is measured in microseconds (millionths of a second). That's roughly a 1,000x slowdown. But for many operations—especially ones where you're moving large blocks of data—that slowdown is acceptable. You're paying a latency penalty for a capacity upgrade that's orders of magnitude larger and costs a fraction as much.

This is why every major cloud provider is suddenly obsessed with storage capacity. It's not a supporting role. It's the main event. The more storage you can attach to each compute unit, the more models you can serve, the more concurrent users you can handle, and the more revenue you generate.

For cloud service providers running hyperscale inference, this becomes a critical constraint. They need storage that's not just large, but also consistent, reliable, and optimized for the access patterns that AI workloads create. A 30TB SSD that has occasional bad blocks or inconsistent latency is worse than useless—it breaks your SLA and costs you customers.

The Rise of 244TB and Beyond

SSDs are getting absurdly large.

Five years ago, a 2TB SSD was enterprise-grade. Now it's basically consumer equipment. 4TB is standard. 8TB is common. And the frontier? There are now 244TB SSDs actually in production or imminent production, as noted by Financial Content.

Yes, 244 terabytes. That's not a typo.

To put that in perspective: 244TB is roughly equivalent to 3,000 movies in 4K. Or the entire Library of Congress in digital format. Multiple times over. Stored on a single drive the size of a large book.

How is this even possible? NAND flash density has improved exponentially. We've gone from single-level cells (SLC) storing 1 bit per cell, to multi-level cells (MLC) storing 2 bits, to triple-level cells (TLC) storing 3 bits. We're now seeing quad-level cells (QLC) storing 4 bits, and pentaevel cells (PLC) on the horizon storing 5 bits.

Bit density is only part of the story. The other part is stacking. Instead of having cells arranged in 2D, manufacturers now stack them vertically. We've gone from single-digit layers to 32, 64, even 176 layers of NAND cells stacked on top of each other. This is where the real capacity explosion comes from.

To hit 244TB, you typically need:

- 32-layer NAND stacking (compared to 16 layers for today's mainstream 122TB drives)

- QLC or PLC NAND (4-5 bits per cell instead of 3)

- Advanced controller architecture capable of managing the added complexity

The engineering challenge isn't conceptual—the design is done. The challenge is manufacturing yield. When you're stacking 32 layers of NAND cells and trying to fit them onto a single die, defects become catastrophic. A single bad cell in layer 28 ruins the entire die. Yields are low, which means costs are high, which means prices are prohibitive.

But yields improve over time. Manufacturing processes mature. Competition drives innovation. In 3-5 years, 244TB drives will become standard. Then the frontier will push to 488TB or beyond.

Why does this matter? Because every major cloud provider is racing to deploy these massive drives. The capacity expansion directly translates to revenue. A data center with 100 244TB drives instead of 100 122TB drives can serve roughly twice as many concurrent inference requests, without adding a single GPU. It's pure economics.

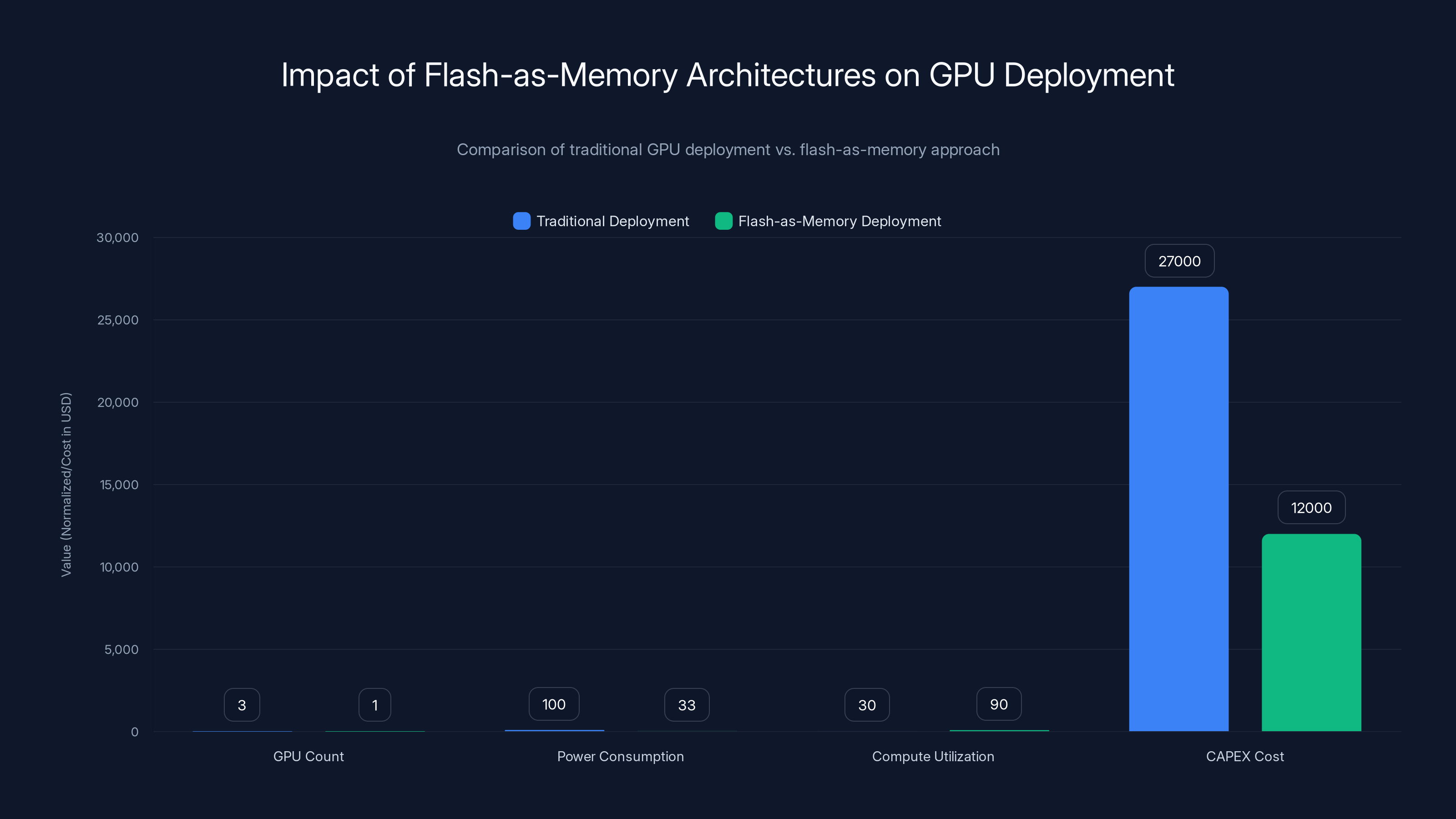

Flash-as-memory architectures significantly reduce GPU count and CAPEX costs while improving compute utilization and reducing power consumption. Estimated data based on typical deployment scenarios.

The Controller Problem: Why 244TB Is Hard

Bigger isn't just harder—it's exponentially harder.

When you double capacity from 122TB to 244TB, you're not just doubling the NAND chips. You're doubling the number of cells, doubling the potential failure modes, and dramatically increasing the complexity of the electronics that manage those cells.

The SSD controller is the brain of the drive. It handles reading, writing, error correction, wear leveling, power management, and a thousand other functions. As capacity increases, controller complexity skyrockets.

At 122TB with 16-layer NAND, the controller needs to manage roughly 17 trillion cells. At 244TB with 32-layer NAND, it's managing 34 trillion cells. Each cell has error rates. Each cell can wear out. Each cell needs to be tracked, monitored, and compensated for.

The error correction codes (ECC) that prevent bit flips from corrupting data become more complex. The wear-leveling algorithms that try to distribute writes evenly become more computationally intensive. The temperature management systems that keep the drive from overheating become more critical. Everything scales nonlinearly.

For a manufacturer, this is a test of engineering. You need controllers that can:

- Track billions of cells individually for error correction

- Redistribute data proactively to avoid endurance failure

- Respond to thermal stress in real-time

- Maintain consistent latency despite increased complexity

- Provide enterprise-grade reliability in high-stress environments

Small mistakes in controller design don't cause minor performance drops. They cause catastrophic failures. An SSD that loses data is worthless—worse than worthless, it's a liability. Enterprise customers will reject entire product lines if there's even a hint of reliability issues.

This is why extreme-capacity drives are still rare. It takes serious engineering expertise to pull it off. Only a handful of manufacturers have demonstrated the ability to do this at scale.

But once manufacturing matures and yields improve, the cost curve becomes attractive. A 244TB drive costs slightly more than two 122TB drives, but you get a single drive instead of two. Less power consumption. Less physical footprint. Less controller overhead. Better reliability through simpler architecture.

The transition from 122TB to 244TB represents a miniature revolution in data center economics. It's the kind of change that forces infrastructure redesigns.

PLC NAND: The Next Frontier (Maybe)

PLC NAND is the theoretical next step in density improvement.

Instead of 4 bits per cell (QLC), PLC pushes to 5 bits per cell. That's a 25% density improvement without any change to physical cell size. With PLC, you could theoretically hit 244TB with just 16 layers of NAND instead of 32. Simpler controller, easier manufacturing, lower cost.

But PLC has a problem: it's hard. Really hard.

When you cram 5 bits of information into a single cell, you have to distinguish between 32 different voltage levels. The margin for error shrinks. Manufacturing tolerances become absurdly tight. Error correction becomes ferociously complex. And endurance gets worse—PLC cells typically wear out faster than QLC cells because the voltage levels are tighter and smaller perturbations cause bit flips.

No major NAND manufacturer has shipped PLC at scale yet. Some have demonstrated prototypes. But production? That's years away at minimum.

Will it happen? Almost certainly. The pressure to increase density is relentless. But it won't happen on a timeline anyone should count on for 2025 planning.

For now, the path to extreme capacity is through stacking (more layers) rather than higher bit density per cell. It's the safe, proven approach. It works. It's just less elegant than PLC would be.

When PLC does mature and ship in volume, it will represent another discontinuity in storage economics. But that's a future conversation. For the next few years, 32-layer QLC is the mainstream frontier.

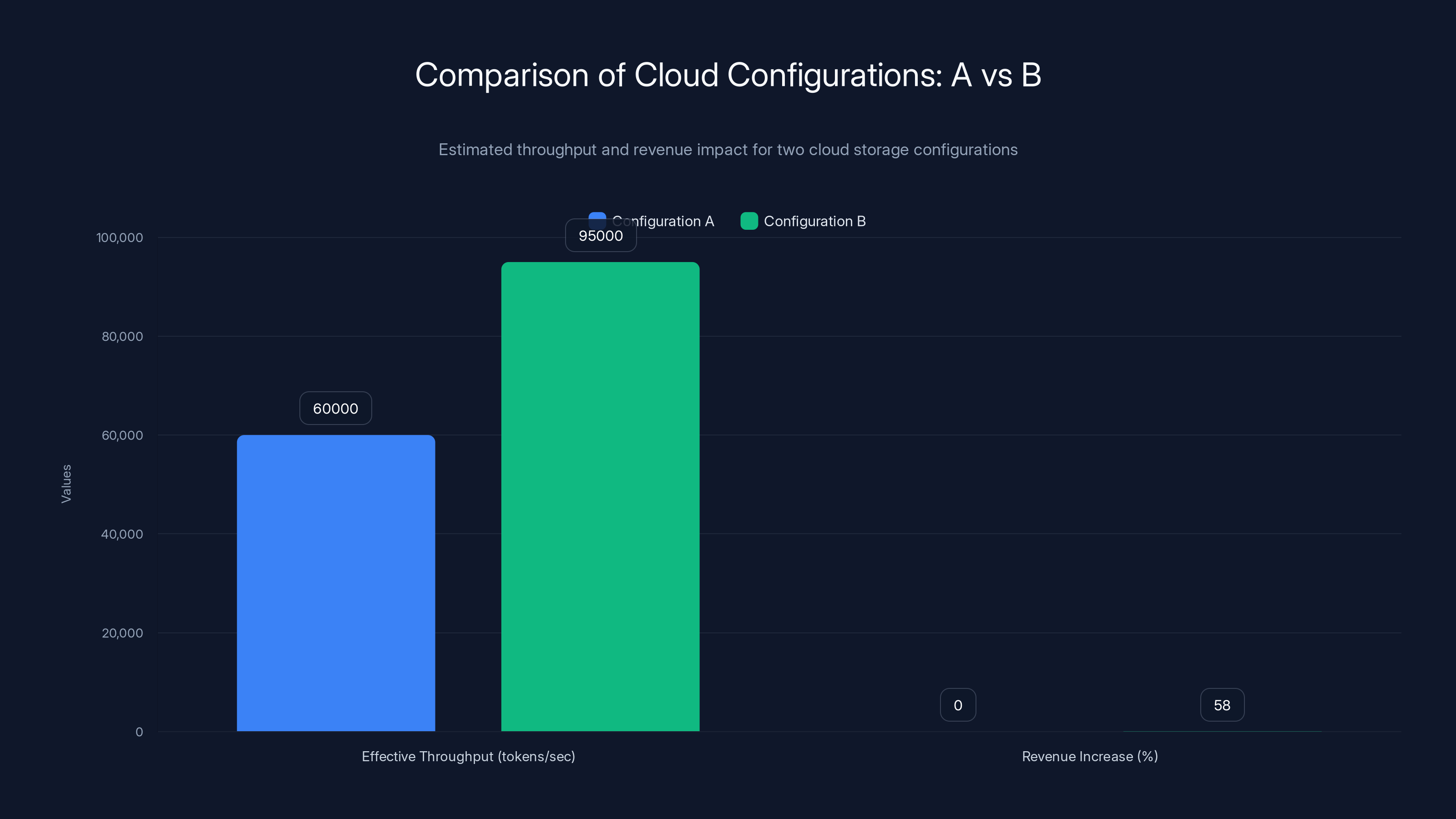

Configuration B, with increased storage capacity, achieves 58% more revenue due to higher effective throughput compared to Configuration A. Estimated data.

High-Bandwidth Flash: A Bad Idea With Sound Intentions

There's a trend in the industry toward integrating NAND flash directly into GPU memory stacks.

The pitch sounds reasonable: combine the speed of GPU-attached memory with the capacity of flash storage. Create a unified memory hierarchy. Eliminate the overhead of traveling across the PCIe bus to fetch data from SSDs.

The engineering logic is sound. The business logic is... questionable.

The fundamental problem is endurance mismatch.

GPUs are built to last. A high-end GPU might operate for 5+ years in continuous service. They're engineered for stability and longevity. The silicon rarely fails. The cooling systems prevent thermal stress. These are devices you expect to work, basically forever (in hardware terms).

NAND flash is fundamentally different. Each cell has a finite number of write cycles. This is called endurance, measured in P/E cycles (program/erase cycles). A TLC NAND cell might tolerate 500-1000 P/E cycles before reliability degrades. QLC cells are even worse—200-500 cycles. PLC cells are expected to be even lower.

Over the lifespan of a GPU (5 years, continuous operation), a write-intensive workload will absolutely exhaust NAND endurance. The flash will fail. And when it does, what happens?

You throw away the entire GPU package.

You can't replace the flash. You can't repair it. It's integrated into the GPU package. It's not modular. When the flash wears out, the GPU becomes expensive electronic waste.

For a $10,000 GPU, that's catastrophic. You're not just losing the flash—you're losing the entire GPU.

Contrast this with modular, replaceable SSDs. When an SSD wears out (which they do, eventually), you unplug it, trash it, and plug in a new one. Thirty seconds. The GPU stays functional. The system stays operational.

This is why integrated high-bandwidth flash is a mistake. The endurance problem creates a failure mode that manufacturers and customers should both want to avoid. It couples the lifespan of a storage medium with a computing device that otherwise would last much longer. It wastes resources.

The modular approach—keeping SSDs as separate, replaceable components—is more pragmatic. Yes, there's some latency cost to going through PCIe to reach external SSDs. But that trade-off is worth avoiding the disaster scenario of exhausted NAND taking down your entire GPU.

This is an example of a good idea executed poorly. The intention (reduce latency) is sound. The implementation (integrate directly into GPU) creates problems worse than the problem you're solving.

CSP Profit Equals Storage Capacity

Here's the uncomfortable economic reality that nobody wants to talk about at GPU conferences:

Cloud service providers are not making money from GPU compute.

They're making money from inference, which is almost entirely limited by storage capacity.

Consider the capital allocation. Major cloud providers have invested over $200 billion in GPU infrastructure over the past few years. That's insane money. And what's the ROI?

GPUs are commodity. The market is hypercompetitive. Margins are thin. You can rent GPU compute, but everybody can. Everybody has GPUs. Pricing pressure is relentless.

Where the real value is? Inference. Running models at scale. Serving models to millions of users. That's where CSPs make margins.

But inference at scale is fundamentally limited by storage. You can provision unlimited GPUs, but if you don't have storage to feed them data, they're just expensive paperweights. The bottleneck isn't compute—it's data availability.

Imagine a cloud provider deploying an inference cluster: 1,000 GPUs, each with 80GB of VRAM. That's 80TB of memory for models and cache. To serve diverse models with good throughput and acceptable latency, you probably need 5-10x that in external storage. So 400-800TB of SSDs.

If the provider doubles storage capacity to 800-1600TB, they can:

- Serve different model versions in parallel

- Cache more results to reduce recomputation

- Serve concurrent requests with less queuing

- Maintain better SLA latency

- Ultimately charge more per token processed

Revenue scales with storage capacity. Not compute. Storage.

This is why Phison, Samsung, SK Hynix, and Kioxia are seeing explosive demand for high-capacity SSDs. Cloud providers are desperate for storage. They'll buy whatever the factories can produce. It's not GPUs they're short on—it's storage.

The business formula is straightforward:

Price per token is set by competition. You can't change that. Models served is limited by compute, sure, but more fundamentally by storage. Tokens generated depends on user demand, which depends on service quality, which depends on latency, which depends on storage consistency.

So the practical formula becomes:

Where f is some function that increases with both variables. More storage means more inference capacity. Consistent, reliable storage means predictable latency and better SLAs.

This insight is driving acquisition strategies. CSPs aren't racing to be the cheapest GPU provider. They're racing to have the most storage. They're signing long-term contracts with NAND manufacturers. They're funding new SSD designs. They're pushing for higher densities and better reliability.

The capital allocation is shifting. It's subtle, but it's happening. Less money flowing to GPU R&D. More money flowing to storage infrastructure.

GPUs are often underutilized, achieving only about 10% of their theoretical capacity due to memory constraints. Estimated data.

The GPU Memory Aggregation Waste Problem

Right now, there's massive inefficiency in how companies deploy GPUs for AI.

Because VRAM is scarce and expensive, organizations buy extra GPUs primarily for memory, not for compute power. You need one GPU for actual processing. You buy two or three more just to have enough VRAM to hold your model.

Those extra GPUs sit idle, maybe hitting 20-30% utilization. They're pulling power. They're taking up rack space. They're costing thousands of dollars. They're barely being used for what they're actually good at—computation.

It's like buying three luxury sports cars because you need three parking spaces. The cars are tremendously expensive. You only drive one. The other two just sit there.

This is happening in thousands of companies right now. It's a massive economic drag.

Flash-as-memory architectures solve this directly. You buy one GPU for compute. You add high-capacity SSDs for memory expansion. Suddenly, you don't need three GPUs anymore. The one GPU handles compute efficiently. The SSDs provide the memory pool.

The financial impact is enormous:

- Fewer GPUs: Maybe 1/3 the GPU count for the same workload

- Lower power consumption: GPUs are power hogs; fewer of them means better efficiency

- Better compute utilization: Existing GPUs now run at higher utilization rates

- Massive CAPEX savings: You're replacing 3,000-5,000 SSDs for equivalent capacity

For a company deploying hundreds or thousands of GPUs, this changes the economics dramatically.

It's why the shift is happening so aggressively. It's not because people suddenly realized SSDs are useful. It's because the economic pressure is relentless. Companies are forced to optimize. Storage-based memory expansion is often the most cost-effective path forward.

But adoption hasn't been universal because it requires rearchitecting systems. You need software that can seamlessly move data between VRAM and SSD. You need controllers that can manage that seamlessly without degrading latency. You need infrastructure designed around this hierarchy.

Companies with greenfield AI deployments are adopting this now. Legacy systems are stuck with traditional GPU stacking for another few years. But the trajectory is clear.

Local Inference and the Consumer Storage Revolution

The bottleneck-is-storage insight doesn't only matter for hyperscalers.

It matters just as much for people running AI models locally on their own machines.

Let's say you want to run a large language model on your laptop. Maybe a 70-billion-parameter open-source model. It's about 140GB of weights (16-bit precision). You need that loaded quickly or accessible with fast response times.

Your laptop probably has 16GB of RAM and a moderately fast SSD. You can't fit 140GB of model weights in RAM. So what happens?

Option 1: Load everything into VRAM on a GPU. This requires a high-end GPU (H100 or RTX 6000). Cost: $5,000-20,000.

Option 2: Load into system RAM and page everything to disk. Cost: Free (you have the hardware already). Result: Awful latency (60+ second TTFT). Unusable.

Option 3: Use a local model that fits in your available memory. Cost: Free. Result: Smaller, less capable models.

The storage bottleneck is crushing the local inference experience. For most people, running local models is just painful. The latency is unacceptable. So they use cloud APIs instead, which costs money and raises privacy concerns.

Flash-as-memory approaches are attempting to bridge this gap. If you can efficiently spill VRAM to a fast SSD, latency becomes tolerable. TTFT drops from 60 seconds to 5-10 seconds. Suddenly, local inference is practical.

This is driving demand for better storage solutions in consumer hardware. Manufacturers are pushing faster NVMe SSDs. Operating systems are improving memory hierarchies. There's pressure to make local AI more practical by improving storage efficiency.

It's a slower change than what's happening in data centers, but it's real. As storage speeds improve and software optimizations mature, local inference will become genuinely practical for ordinary people. Today it's a toy. In 3-5 years, it might be mainstream.

That changes everything about AI adoption. If people can run capable models locally—with acceptable latency, acceptable cost, and no privacy concerns—the entire paradigm shifts. Cloud API dependency decreases. Edge deployment increases. Distribution becomes possible.

The Inference Economics: Why Capacity Scales Revenue

Let's dig into the actual math of how cloud providers monetize AI services.

Inference is typically priced per token processed. A large language model might cost

For a cloud provider, the relevant metric is tokens per second per dollar of infrastructure.

Consider two configurations:

Configuration A: 100 GPUs, 10TB of storage

- Can serve roughly 100,000 tokens per second aggregate (rough estimate)

- Storage is bottleneck for concurrent user support

- Actual utilization: ~60% due to queuing and latency constraints

- Effective throughput: 60,000 tokens/sec

Configuration B: 100 GPUs, 100TB of storage

- Can serve the same 100,000 tokens per second of raw compute

- Storage is not a bottleneck—models are diverse, cache is deep

- Actual utilization: ~95% due to reduced queuing and consistent latency

- Effective throughput: 95,000 tokens/sec

Configuration B costs more (extra $3-5 million in storage), but generates 58% more revenue with the same GPU count. That's a 58% increase in ROI on the compute portion.

The math works out aggressively in favor of more storage.

For extreme-capacity drives, this becomes even more pronounced. A 244TB drive instead of two 122TB drives costs maybe 10% more but provides organizational simplicity, lower power consumption, and better reliability. Over a 5-year lifespan, that's significant margin improvement.

This is why cloud providers are so desperate for storage. It's not because storage is expensive—it's because storage is how you monetize expensive compute.

The formula:

GPU count is set by capital allocation. But storage capacity is easier to scale—it's cheaper, uses less power, takes up less space. So providers optimize for storage. They buy more storage. They push for higher densities. They contract long-term with NAND manufacturers.

The business logic is relentless. Capacity is profit.

The Endurance Paradox: Why Bigger Drives Last Longer

There's a counterintuitive phenomenon with high-capacity SSDs: they often last longer than smaller drives.

This isn't because the NAND is better. It's because of wear leveling and capacity overhead.

Wear leveling is an algorithm inside the SSD controller. When you write to an SSD, the controller doesn't write to the first available cell. It distributes writes across the entire drive, rotating which cells handle new data. This spreads wear evenly.

But there's a trade-off: overhead. A drive operating near full capacity has less headroom for wear distribution. If you write 100GB per day to a 200GB drive, you're cycling through 50% of the drive. If you write 100GB per day to a 2TB drive, you're cycling through 5% of the drive. The 2TB drive's wear-leveling algorithm can balance the load across much more space.

Over time, the smaller drive's cells get more write cycles, wear out faster, and reliability degrades.

This is compounded by spare blocks. SSDs reserve a portion of capacity (typically 10-20%) for error correction and replacement blocks. Larger drives have proportionally more spare capacity, which means more flexibility for dealing with worn cells.

So here's the strange reality: a 244TB drive used for similar daily throughput as a 122TB drive will likely last longer. Not just in absolute time, but in data written before failure.

This is another economic argument for extreme-capacity drives. You're not just getting more capacity. You're getting better reliability and longer lifespan. The cost per petabyte-year drops substantially.

Cloud providers understand this. They optimize infrastructure for large capacity drives precisely because of this endurance benefit.

Building the Storage Infrastructure for AI: Practical Considerations

If you're actually tasked with deploying AI infrastructure—whether that's a small team running local models or a cloud provider scaling to millions of users—storage decisions become critical and complex.

First: capacity planning. You need to estimate peak concurrent model serving. A 70B model with a 4K context window needs roughly 140GB for weights plus 30-40GB for KV cache and temporary buffers. If you want to serve 10 concurrent instances in parallel (different users, different queries), you need 1.4TB just for model weights, plus additional storage for KV cache management, model versioning, and fallback models.

Second: latency budgeting. You've set a TTFT target (probably 2-5 seconds for production). That includes network latency (10-100ms), GPU context switching (10-100ms), and everything else. Storage access latency needs to fit into the remaining budget. If you're accessing SSD, you need sub-5ms access times consistently. This rules out older mechanical storage and even some older SSDs.

Third: reliability planning. When an SSD fails, what happens? In a modular architecture, you swap it out and keep running. In an integrated architecture, you lose an entire GPU. The difference in operational complexity is vast.

Fourth: power and thermal management. Large SSDs consume power—maybe 10-15 watts under load. Multiply by dozens or hundreds, and you're talking serious cooling infrastructure. GPU data centers are already thermally challenged. Adding massive storage can push cooling systems past limits.

Fifth: data locality. Where does data live? Is it replicated across SSDs? Is it tiered (hot data in fast storage, cold data in cheaper storage)? How does this interact with your compute scheduling?

These aren't small decisions. Getting them wrong means you deploy expensive infrastructure that doesn't perform, costs more than expected, or fails when you need it most.

The best practice approach:

- Measure first: Profile your actual access patterns for 2-4 weeks. Don't guess.

- Prototype: Build a small-scale version with planned storage architecture. Test failure scenarios.

- Over-provision slightly: You want headroom. A drive running at 85% capacity for extended periods degrades faster.

- Plan for replacement: SSDs will eventually fail. Build processes for swapping drives without downtime.

- Monitor relentlessly: Track capacity trends, latency distribution, and error rates. When storage is the bottleneck, visibility is critical.

The Future: Extreme Density, Extreme Scale

Where is this heading?

The trend is obvious: ever-larger SSDs, ever-denser NAND, ever-more-capable controllers. We're moving toward a world where a data center contains storage measured in exabytes per building (millions of terabytes). Where the effective memory hierarchy for an AI system spans from nanosecond VRAM to microsecond NAND to millisecond spinning disk to seconds of external cloud storage.

The hardware path forward:

- 244TB drives by 2025-2026, deployed at massive scale

- PLC NAND by 2027-2028, improving density further

- 500TB+ drives by 2028-2030, using multiple dies stacked

- Better controllers that handle the complexity transparently

- Improved memory hierarchies in software that seamlessly migrate data

The software path forward:

- Transparent memory expansion, where developers don't have to think about VRAM limits

- Smarter caching that predicts what data will be needed and pre-stages it

- Distributed inference that spans multiple machines transparently

- Better TTFT optimization through aggressive caching and prediction

The economic path forward:

- Storage becomes the primary cost driver in inference infrastructure

- Compute becomes a commodity with thin margins

- CSPs optimize for storage efficiency rather than raw throughput

- Edge deployment increases as local inference becomes practical

The constraint that's holding all of this back? Manufacturing capacity. We can design 244TB drives. We can engineer systems to use them efficiently. What we can't do (yet) is manufacture enough of them to meet demand. NAND fabrication plants are capacity-limited. That's the real bottleneck.

Once fabrication catches up—probably by 2027-2028—the flood gates open. Storage-based AI infrastructure becomes the default. Hyperscalers don't build their next generation of data centers around compute. They build around storage, with compute as the supporting component.

That's a fundamental inversion of how we talk about AI infrastructure today. But it's where the data points. It's where the money is flowing. And it's where the architecture is heading.

FAQ

What is the AI memory bottleneck?

The AI memory bottleneck refers to the constraint imposed by limited VRAM (video RAM) on graphics processors, preventing models from being served efficiently. While GPUs have significant computational capacity, they frequently sit idle waiting for data to load from storage, making memory availability and data access speed the actual limiting factor in AI inference systems, not raw computing power.

How does flash-as-memory architecture improve AI inference performance?

Flash-as-memory creates a hybrid memory hierarchy where high-capacity SSDs complement limited VRAM, allowing systems to store larger models and more cache data at a lower cost than pure DRAM expansion. When GPU VRAM fills up, frequently accessed data spills to fast SSDs (with microsecond latency) rather than system RAM or causing failures, dramatically improving time-to-first-token and enabling better resource utilization across inference clusters.

Why is Time to First Token (TTFT) critical for AI services?

Time to First Token is the delay between when a user submits a prompt and when the first output appears. Research shows users abandon AI applications if TTFT exceeds 10 seconds, and mobile thresholds drop to 3 seconds. TTFT is almost entirely a storage latency problem, as GPUs spend most time waiting for model weights and cache data to load. Optimizing TTFT requires optimizing storage access patterns and capacity.

What advantages do extreme-capacity SSDs like 244TB drives provide?

Extreme-capacity drives (244TB and above) provide enormous economic advantages: a single drive replaces multiple smaller drives, reducing power consumption, physical footprint, and controller overhead. These drives also benefit from improved wear-leveling algorithms and larger spare capacity pools, often achieving better reliability and longer operational lifespans than smaller drives. For cloud providers, larger drives directly translate to more inference capacity with the same GPU count.

Why isn't integrating NAND flash directly into GPU packages a good solution?

Integrating NAND directly into GPU packages creates an endurance mismatch problem. NAND cells have finite write cycles (500-1000 for TLC, 200-500 for QLC). When the flash reaches end-of-life in an integrated package, the entire expensive GPU becomes unusable and must be discarded. Modular, replaceable SSDs solve this by allowing storage replacement without losing compute hardware, providing better economics and reliability for enterprise deployments.

How does storage capacity directly impact cloud service provider (CSP) revenue?

CSPs generate revenue through inference serving (processing tokens), which is fundamentally limited by available storage capacity rather than GPU count. With more storage, providers can serve more diverse models concurrently, cache more results to avoid recomputation, and maintain better latency SLAs for more users simultaneously. The formula simplifies to: CSP Profit = f(Storage Capacity, Storage Consistency), making storage the primary driver of inference revenue scaling.

What is PLC NAND and when will it be available at scale?

PLC (Penta-Level Cell) NAND stores 5 bits per cell compared to 4 bits for current QLC cells, theoretically providing 25% higher density without physical size changes. PLC would enable 244TB drives with fewer stacked layers, simplifying manufacturing. However, PLC is not yet available at production scale due to engineering challenges in voltage-level discrimination and error correction. Industry expectations suggest volume production by 2027-2028 at earliest.

How can companies reduce GPU over-provisioning through better storage utilization?

Traditionally, organizations buy multiple GPUs primarily for memory aggregation (VRAM), leaving most GPU compute unused. By implementing flash-as-memory architectures with high-capacity SSDs, companies can reduce GPU counts by 2-3x while maintaining or improving performance. A single GPU handles computation; SSDs provide the expanded memory pool. This can reduce CAPEX by 60-70% while improving GPU utilization from 20-30% to 70-90%, with direct impact on operational efficiency and profitability.

What manufacturing challenges prevent faster SSD capacity scaling?

The main constraint is manufacturing yield at extreme scales. Stacking 32+ layers of NAND cells on a single die and connecting billions of cells introduces exponential complexity. A single defect in layer 28 can destroy the entire die. Manufacturers must continuously improve fabrication processes to increase yields. Even with complete design documentation for 244TB drives, production yields may be too low for cost-effective manufacture until processes mature, typically taking 1-2 years after design completion.

Conclusion: Storage Reshaping AI Economics

The AI revolution is often told as a story about GPUs and compute. That narrative is incomplete.

The real story is about storage becoming the foundational constraint in AI systems, from local inference on laptops to hyperscale data centers serving millions of users. It's about realizing that $20,000 GPUs sitting idle waiting for data is wasteful. It's about rearchitecting everything to optimize for the constraint that actually matters.

This shift is happening faster than the industry publicly acknowledges. Cloud providers are desperately acquiring storage. Engineers are redesigning systems to use SSDs as memory expansion. Manufacturers are racing to scale capacity. The capital flows are shifting from compute to storage.

For organizations building AI infrastructure, this means the old playbook doesn't work anymore. You can't just buy the biggest GPUs and expect everything to work efficiently. You have to think deeply about storage architecture. You have to optimize latency. You have to understand that storage capacity, not GPU count, is what actually scales your revenue.

For people running local models, the implication is hopeful: as storage access becomes faster and software improves, local inference will become practical. You won't need expensive GPUs or cloud API fees. Your computer will have enough storage and access speed to run capable models with acceptable latency.

For NAND manufacturers, the implication is obvious: the demand for storage is inexhaustible. Every advance in capacity gets consumed immediately. The constraint isn't technical—it's manufacturing capacity. Whoever can scale production fastest wins.

The bottleneck isn't computing power. It never was. We just needed to look past the hype to see what actually mattered.

Storage. Always storage.

Key Takeaways

- Storage capacity, not GPU compute, is the actual bottleneck limiting AI model deployment and inference scaling

- Flash-as-memory architectures using high-capacity SSDs reduce GPU over-provisioning waste by 60-70% and improve utilization from 20% to 80%+

- Time to First Token is a user experience metric determined almost entirely by storage access latency, not compute speed

- Cloud service providers' revenue is fundamentally tied to storage capacity: CSP Profit approximately equals function of storage capacity and consistency

- 244TB SSDs are entering production with 32-layer NAND stacking; PLC NAND will achieve similar capacity with 16 layers but manufacturing challenges delay 2027-2028 availability

- Integrating NAND directly into GPU packages creates endurance mismatch problems, making modular replaceable SSDs the superior architecture

- Local AI inference becomes practically viable when storage access enables acceptable TTFT (under 10 seconds) through optimized cache management

Related Articles

- Skild AI Hits $14B Valuation: Robotics Foundation Models Explained [2025]

- VoiceRun's $5.5M Funding: Building the Voice Agent Factory [2025]

- Microsoft's Community-First Data Centers: Who Really Pays for AI Infrastructure [2025]

- Microsoft's Data Center Expansion: How Tech Giants Are Managing Energy Costs [2025]

- Microsoft's $0 Power Cost Pledge: What It Means for AI Infrastructure [2025]

- DeepSeek's Conditional Memory: How Engram Fixes Silent LLM Waste [2025]

![AI's Real Bottleneck: Why Storage, Not GPUs, Limits AI Models [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-s-real-bottleneck-why-storage-not-gpus-limits-ai-models-2/image-1-1768414679250.jpg)