Introduction: The Paradox of Building Your Own AI Chip While Buying from Competitors

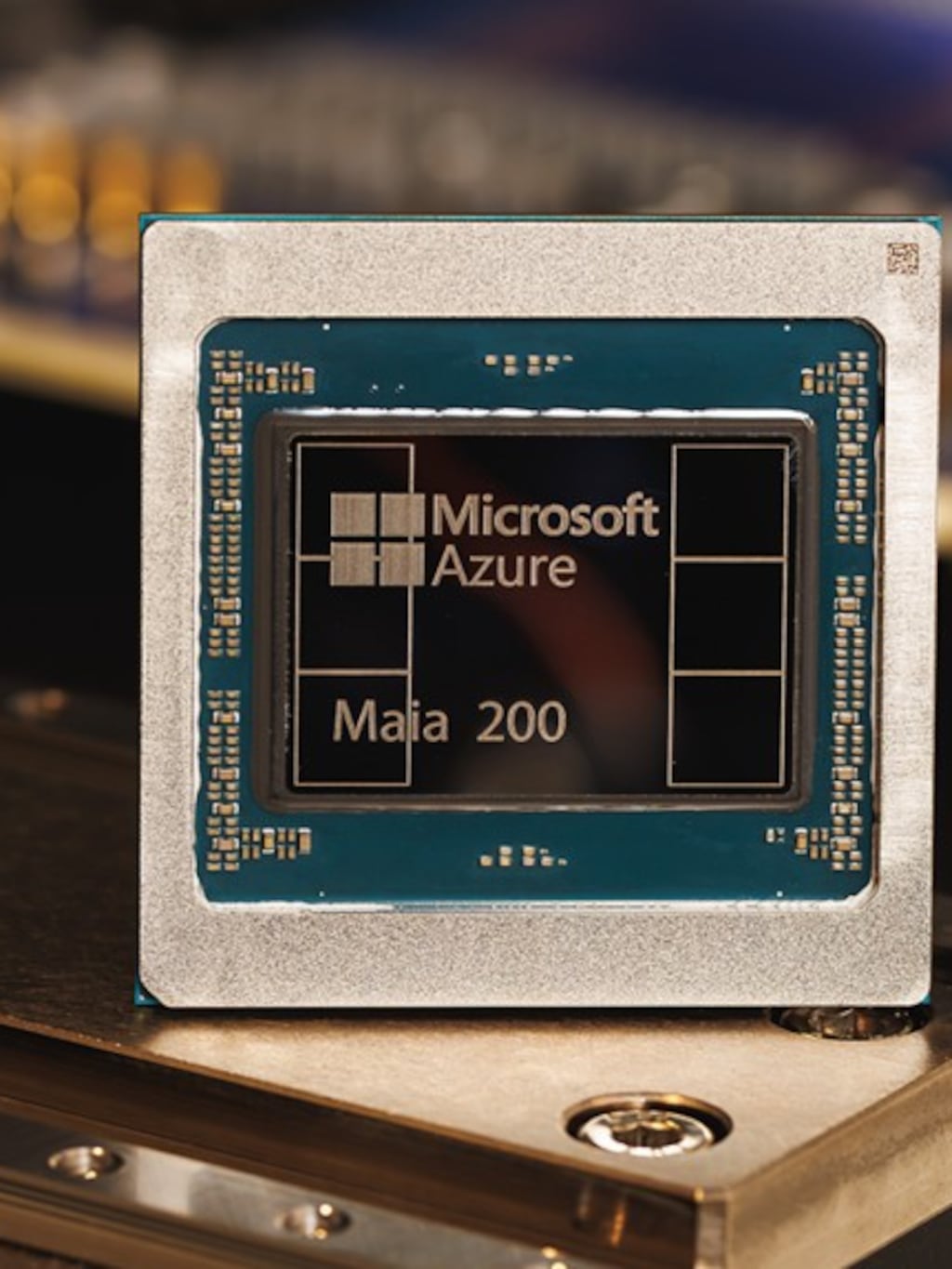

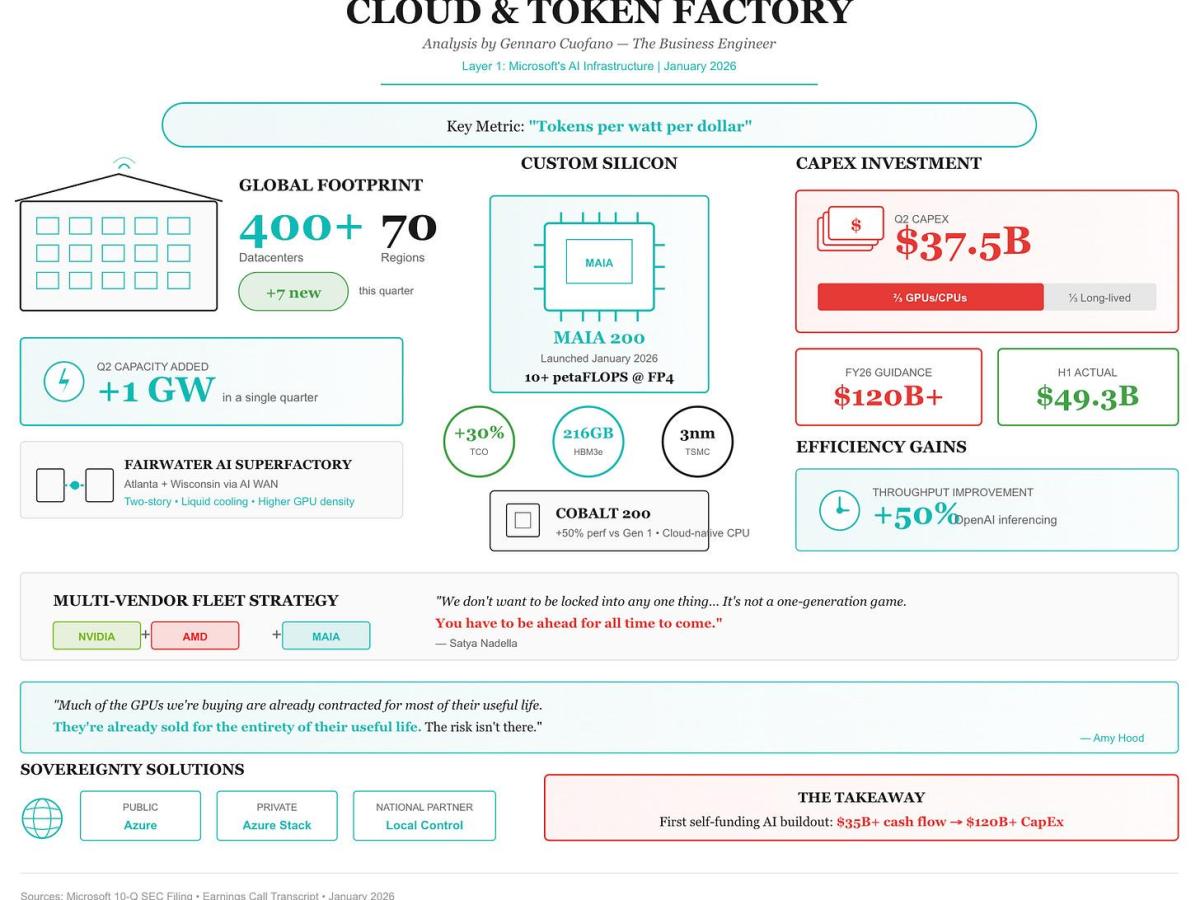

Here's something that caught everyone off guard last year: Microsoft launched its own AI chip, the Maia 200, while publicly committing to keep buying from Nvidia and AMD. It sounds contradictory, right? Why invest billions in custom silicon if you're going to keep relying on the same vendors everyone else depends on?

But that's exactly what's happening in the cloud computing world right now, and it reveals something crucial about the current state of AI infrastructure. The demand for compute is so massive, and supply is so constrained, that no single company can afford to put all its eggs in one basket, even if that basket is their own creation.

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella made this crystal clear when he said something that stuck with people: "You have to be ahead for all time to come." Not just today. Not just this quarter. All the time. That means building your own chips to reduce dependency, but simultaneously keeping relationships with partners who are pushing innovation forward faster than any single company can manage internally.

This dual strategy isn't a compromise or a failure of internal development. It's a calculated hedge against an industry moving too fast for any one player to control alone. And it's reshaping how every major cloud provider thinks about hardware, competition, and the future of AI at scale.

In this article, we're going to dig into why Microsoft made this move, what the Maia 200 actually does, why the company can't (and shouldn't) abandon Nvidia and AMD, and what this all means for the broader AI infrastructure landscape.

TL; DR

- Microsoft's Maia 200 is inference-focused hardware designed to run trained AI models efficiently, not train them from scratch

- The company continues buying Nvidia and AMD chips despite launching its own because demand vastly exceeds supply across the industry

- Custom silicon reduces dependency but doesn't eliminate it because no single architecture handles all compute workloads optimally

- Supply constraints are the real driver behind Microsoft's custom chip strategy, not a desire to replace established vendors

- This trend is spreading as Google, Amazon, and Meta all develop custom AI chips while maintaining vendor relationships

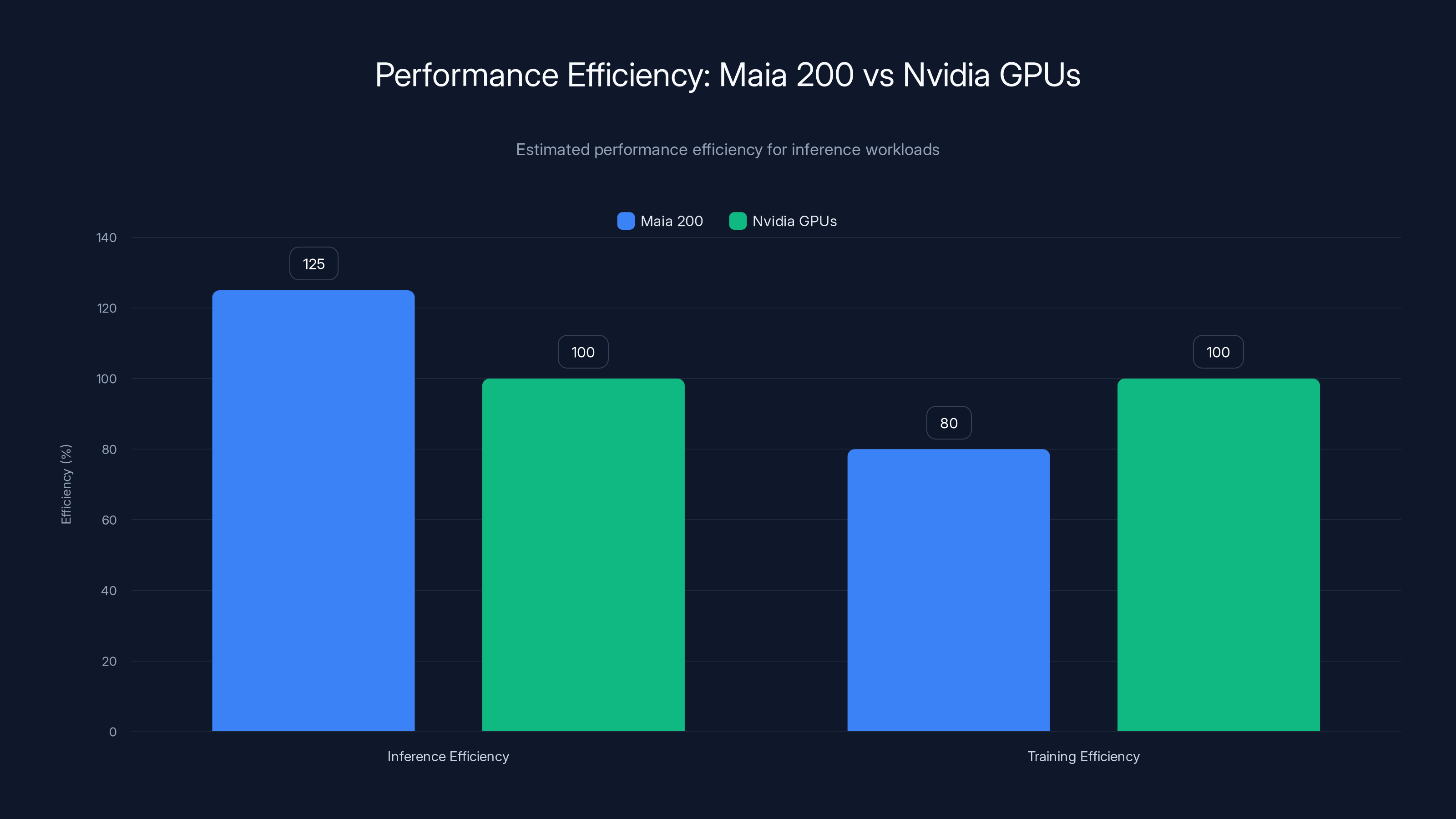

Maia 200 shows an estimated 25% efficiency improvement over Nvidia GPUs for inference workloads, while Nvidia remains superior for training tasks. Estimated data.

Why Microsoft Built Maia 200: The Supply Crisis That Changed Everything

Let's back up. Two years ago, the conversation in enterprise cloud was straightforward: buy Nvidia GPUs, whatever it takes. That was the playbook. Everyone wanted the same chips. Nobody had alternatives that actually worked at scale. Nvidia's dominant position was almost unquestioned.

Then two things happened simultaneously.

First, the demand for AI compute exploded. Chat GPT hit 100 million users in two months. Every major corporation suddenly needed to train and run large language models. The appetite for GPUs went from high to "where's the nearest emergency room" levels of critical.

Second, Nvidia couldn't keep up. Not because they didn't want to. Not because they weren't manufacturing like crazy. But because the bottlenecks in semiconductor production run deep. It takes months to spin up new fabrication capacity. New GPU architectures take years to design. And suddenly, everyone on Earth wanted them at the same time.

Microsoft faced a specific problem: its data centers needed more compute than Nvidia could deliver. Building more data centers doesn't help if you can't fill them with processors. So the company made the strategic decision to design its own silicon. Not to abandon Nvidia. Not to prove it could do better on every metric. But to add optionality when constraints threatened to limit growth.

This is why Satya Nadella's statement matters so much. He wasn't saying "we'll use our chip for everything." He was saying "we need multiple sources of supply because relying on any single vendor creates unacceptable risk when demand is this high."

Microsoft's move forced other companies to follow. Google had been building its TPUs for years, but suddenly they made sense as primary infrastructure rather than nice-to-haves. Amazon accelerated its Trainium and Inferentia chip programs. Meta went all-in on custom ASIC development. The entire industry shifted from "let's buy what Nvidia makes" to "let's design what we actually need."

But here's the key insight everyone misses: this didn't kill the GPU market. It fragmented it. And that fragmentation created new problems.

The Maia 200 Explained: What It Does and Why It's Specialized

Let's talk about what Maia 200 actually is, because the marketing materials make it sound like a Nvidia killer, and it absolutely isn't.

Maia 200 is an inference accelerator. That's the crucial detail. Inference means running a model that's already been trained to generate outputs. You feed it input. It produces predictions. That's it. You're not doing the computationally brutal work of training a billion-parameter model from scratch.

Why does this distinction matter? Because training and inference have completely different hardware requirements.

Training a large language model is like mining for gold. You need massive parallelism, extremely high floating-point throughput, and the ability to coordinate computations across hundreds or thousands of processors simultaneously. Nvidia's A100 and H100 GPUs are designed exactly for this. They're built to process massive tensor operations super efficiently because that's 80% of what deep learning training requires.

Inference is different. It's more like running a search query through a prepared database. You still need processing power, sure, but the bottleneck isn't raw compute. It's memory bandwidth and latency. You're moving data in and out of memory. You're accessing weights stored in massive matrices. The speed at which you can fetch data and move it between your processing units matters more than how many floating-point operations you can squeeze per second.

This is where Maia 200 shines. Microsoft optimized it specifically for sustained inference workloads with heavy dependence on memory throughput. According to Microsoft's internal benchmarks, it handles memory-bound operations more efficiently than general-purpose GPUs designed primarily for training.

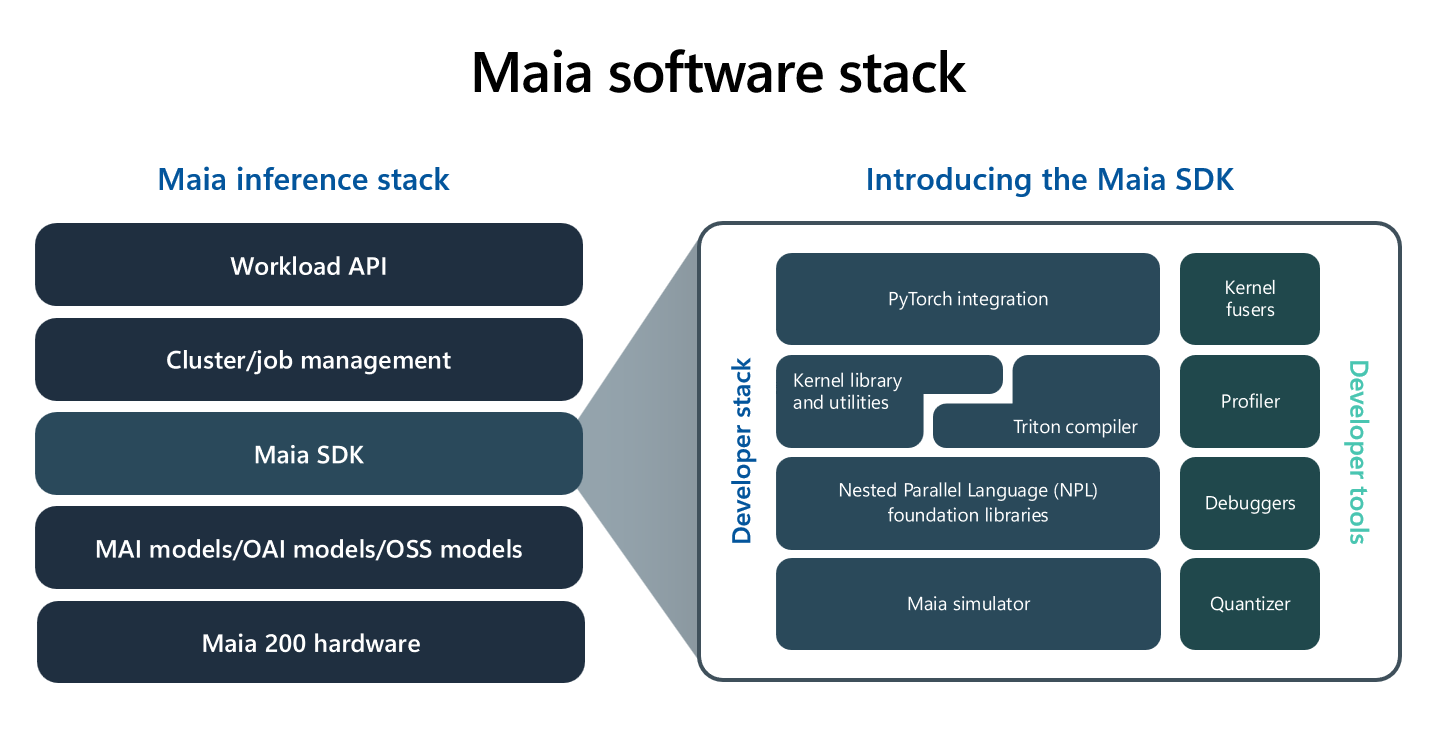

The technical specs are interesting. Maia 200 emphasizes:

- High memory bandwidth: Critical for moving data between GPU and system RAM efficiently

- SSD throughput optimization: Handling access patterns that involve fast storage

- Reduced latency on memory operations: Inference workloads are sensitive to how quickly you can fetch model weights

- Cost efficiency at scale: The design focuses on cost per inference operation, not peak theoretical performance

Microsoft's claim is that Maia 200 delivers better price-to-performance for inference than comparable third-party options. Is this true? The honest answer is we don't have independent benchmarks yet. Microsoft hasn't published detailed technical specifications, and no one outside the company has run rigorous tests. So the verdict is still out.

But here's what matters more than the raw numbers: Microsoft built this chip because the company needed it. That need is real. The company is running inference workloads at such massive scale that having hardware specifically optimized for that workload provides real value.

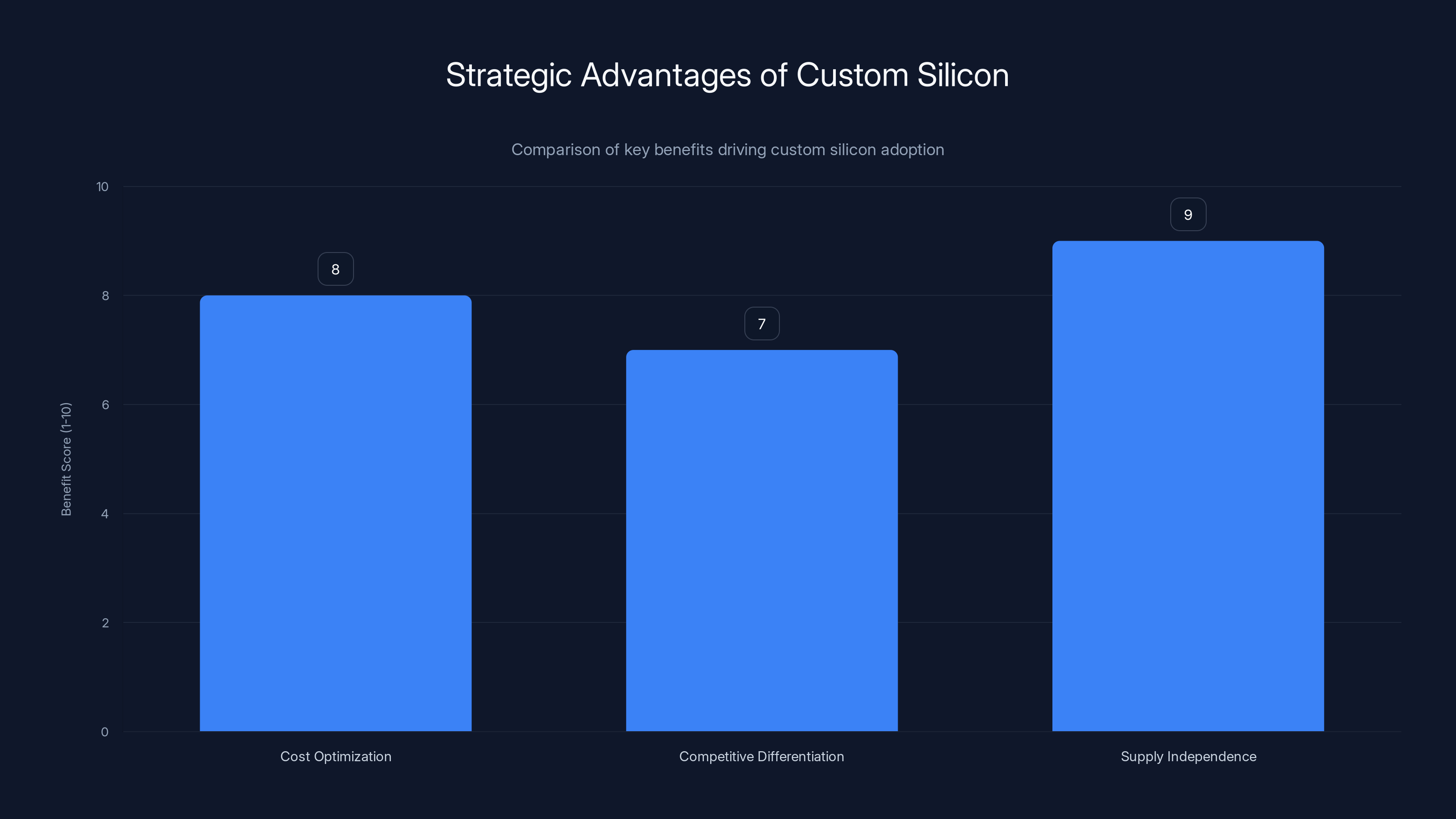

Custom silicon remains valuable due to cost optimization, competitive differentiation, and supply independence, even as Nvidia's supply normalizes. Estimated data based on strategic insights.

Why Microsoft Can't Abandon Nvidia and AMD (And Why They Don't Want To)

Now we get to the question people actually care about: if Microsoft has its own chip, why do they still need Nvidia and AMD?

The simple answer: one chip can't do everything.

Maia 200 is optimized for a specific workload pattern: large-scale inference with high memory bandwidth demands. It's phenomenal at that. But it's not phenomenal at everything else cloud computing requires.

Consider what happens when you try to force a specialized tool to do work outside its specialty. You get suboptimal results. The same way a hammer works great for nails but is terrible for sawing wood, a chip optimized for inference-heavy workloads isn't necessarily ideal for training, real-time computing, or other emerging AI applications.

Microsoft needs multiple chip types:

Training-focused workloads: When Microsoft helps customers build new models or fine-tune existing ones, those jobs still run most efficiently on Nvidia's H100 GPUs. The company could use Maia 200, but it would work against the chip's design principles. You'd get worse performance and spend more compute cycles.

Emerging workloads: New AI applications pop up constantly. Some require different memory access patterns, different precision requirements (float 32 vs. float 16 vs. bfloat 16), or different interconnect needs. Nvidia and AMD have huge families of processors at different performance tiers. Microsoft can't build a different custom chip every quarter.

Time-to-market: Nvidia releases new GPU architectures every 18-24 months. AMD follows a similar cadence. Microsoft's custom silicon takes years from design to production. By the time a new internal design ships, the external landscape has already moved forward. Maintaining vendor relationships lets Microsoft adopt new capabilities faster.

Scaling flexibility: When demand for compute spikes unpredictably, you need access to whatever inventory is available. Microsoft has relationships with Nvidia, AMD, and other suppliers that give the company priority access during shortages. These relationships only stay strong if Microsoft actually buys and uses their products.

Satya Nadella's statement really does capture this perfectly. "We can vertically integrate doesn't mean we just only vertically integrate." In other words: we can build our own chips, and that's awesome for specific problems. But we don't want to limit ourselves to only our own innovation.

There's also a geopolitical element here that people don't talk about enough. Nvidia is an American company with global supply chains. AMD is American too. But both have complex manufacturing relationships across different countries. If Microsoft relies exclusively on its own silicon, the company becomes dependent on its own ability to navigate advanced chip manufacturing. That's extremely risky.

By maintaining strong relationships with multiple external vendors while simultaneously developing custom silicon, Microsoft creates optionality. The company can shift workloads between chip types based on cost, availability, and performance. When Nvidia has supply constraints, Microsoft can route work to AMD or internal chips. When custom silicon reaches capacity, external suppliers fill the gap. This flexibility is worth more than raw efficiency gains from any single chip.

The Broader Hardware Ecosystem: How Everyone Is Copying This Strategy

Microsoft isn't alone here. Every major cloud provider recognized this same constraint and made similar decisions.

Google's TPU journey started earlier than most people realize. Google began developing Tensor Processing Units back in 2016, years before the AI explosion. But TPUs were originally internal tools, used to speed up Google's ML operations. When the company finally went public with TPU availability in 2018, it was almost incidental. What changed is that Google now positions TPU availability as a core offering, and the company still buys massive quantities of Nvidia GPUs for customer workloads that perform better on them.

Amazon's Trainium and Inferentia chips launched more quietly but follow the same playbook. Trainium handles training workloads optimized for deep learning. Inferentia focuses on inference. Together, they give Amazon optionality. But if you look at AWS's compute offerings, the Nvidia GPU options are still front and center.

Meta's MTIA (Meta Training and Inference Accelerator) represents one of the most aggressive custom silicon programs. Meta is building chips that the company initially reserved for its own AI training needs, then gradually opened to external customers. Like Microsoft, Meta continues to buy significant quantities of Nvidia GPUs.

This trend reveals something important: the custom silicon wave isn't about replacement. It's about specialization. It's about having the right tool for each job instead of forcing every workload through a general-purpose GPU.

The competition here isn't between custom chips and Nvidia GPUs. It's between companies that can orchestrate multiple chip types efficiently and those that can't. Nvidia's dominance remains genuine because no other company has matched their breadth of applications and market share. But that dominance is increasingly constrained to specific workload categories.

Supply Constraints and Market Dynamics: The Hidden Driver of Hardware Diversity

Let's zoom out and look at the real economics here.

In 2023 and early 2024, Nvidia couldn't manufacture enough GPUs to meet demand. The company was backlogged for months. Pricing went absurd. Some customers reported effective per-unit costs of $40,000 or more when you factored in supply chain intermediaries.

This created a weird market dynamic: cloud providers couldn't reliably get the chips they needed, but demand from customers was climbing exponentially. Something had to give.

Microsoft's response was to build Maia 200. Google accelerated TPU production. Amazon ramped Trainium and Inferentia. Meta committed even more resources to MTIA. All of these happened roughly simultaneously, driven by the same constraint: insufficient supply from traditional vendors.

But here's the tricky part: custom silicon doesn't immediately solve the supply problem. There's a multi-year lag between deciding to build a chip and actually deploying it at scale. By the time Maia 200 hit production deployments in 2024, Nvidia had already expanded manufacturing significantly. The supply squeeze eased.

So now the question becomes: what happens to custom silicon demand when supply normalizes?

The answer is nuanced. Custom silicon remains valuable even with healthy Nvidia supply because it provides three strategic advantages:

-

Cost optimization: A chip designed specifically for your workload is always more efficient than a general-purpose GPU. That efficiency compounds at massive scale.

-

Competitive differentiation: If Microsoft can offer inference capacity that's 20-30% cheaper than competitors, that's a meaningful competitive advantage for the company's Azure cloud platform.

-

Supply independence: Even if Nvidia isn't backlogged right now, the company could be hit by geopolitical disruptions, manufacturing issues, or other unforeseen constraints. Having internal capacity provides a safety buffer.

These advantages persist regardless of short-term supply conditions. So custom silicon is here to stay. But it's an addition to the ecosystem, not a replacement.

Custom silicon like Microsoft's Maia 200 can reduce standard inference costs by 15-25%, while premium Nvidia-based services and training workloads remain unchanged. (Estimated data)

The Mustafa Suleyman Factor: How Internal AI Teams Shape Hardware Strategy

There's a detail in the original reporting that deserves more attention: Mustafa Suleyman's Superintelligence team gets first access to Maia 200 hardware.

Why does this matter? Because it reveals how hardware strategy is actually decided at major tech companies.

Suleyman leads Microsoft's most advanced internal AI research. The work he's overseeing involves training and running frontier models, the cutting-edge stuff that pushes against current hardware limits. If anyone inside Microsoft can justify custom silicon, it's this team.

Giving Superintelligence first access to Maia 200 serves multiple purposes:

- Validates the investment: Using the chip for breakthrough research proves the hardware actually works for meaningful tasks

- Iterates the design: Real-world usage from advanced teams informs the next generation of improvements

- Generates competitive advantage: If Suleyman's team can build better models faster with Maia 200, that translates to better products for Azure customers

- Builds internal expertise: Engineers working with the hardware daily learn how to optimize it

This is actually how Google and Meta operate too. Their most advanced research teams get first access to custom silicon. The chips mature through production workloads before being offered broadly to external customers.

But notice what this also means: Maia 200 is not yet optimized for average workloads. It's optimized for Microsoft's most advanced use cases. General Azure customers might see it as an option, but they'll probably continue using Nvidia GPUs for production workloads until Maia 200 proves itself at scale.

This also explains why Microsoft keeps buying from Nvidia and AMD. Until Maia 200 proves itself broadly, customers need alternatives. Offering Maia 200 as the only option would immediately drive customers to Google Cloud, AWS, or other providers.

Memory Bandwidth: The Real Bottleneck That Maia 200 Solves

Let's dig into the technical specifics a bit more, because understanding what Maia 200 actually optimizes reveals why the chip is valuable despite not being a Nvidia replacement.

Here's a fact about modern deep learning inference that surprises people: the bottleneck usually isn't computation. It's memory bandwidth.

Consider what happens when you run an inference job on a GPU. You load a trained model into memory. That model might be 70 billion parameters. Each parameter is a floating-point number. The GPU needs to fetch these parameters repeatedly as it processes input tokens.

The computation itself is fast. Modern GPUs can do trillions of floating-point operations per second. But fetching those parameters from memory to the GPU's internal compute units? That's slow. Really slow. Relatively speaking.

There's a concept in computer architecture called the "arithmetic intensity" or "compute-to-memory ratio." It measures how many floating-point operations you can do per byte of data fetched from main memory.

For inference workloads on large language models, this ratio is terrible. You need to move massive amounts of data relative to the computations performed. That means the GPU spends most of its time waiting for data, not computing.

Microsoft optimized Maia 200 specifically to reduce this memory bottleneck. The chip features:

- Higher memory bandwidth: More bytes per second flowing between the GPU and system RAM

- Optimized memory hierarchy: Better caching strategies to reduce round-trip latency on frequent accesses

- Efficient interconnect: Faster communication between the GPU and storage systems

Quantitatively, the difference might be 20-30% improvement in inference throughput compared to general-purpose GPUs on the same workload. That sounds modest, but at cloud scale, it's enormous.

Imagine you're running inference on 100,000 GPUs. A 25% improvement in throughput means you can serve 25% more inference requests without adding hardware. Or equivalently, you can handle current request volume with 20% fewer GPUs. At

Nvidia's GPUs have high memory bandwidth too, but they optimize for a broader set of workloads. Maia 200 optimizes specifically for this pattern. That focus creates efficiency gains.

But this also illustrates why Microsoft can't replace Nvidia entirely. When you have diverse workloads—training, inference, real-time prediction, data processing, graphics—you need broad optimization, not narrow specialization.

Cost Implications: How Custom Silicon Changes Cloud Pricing

Here's a question people don't ask enough: what does custom silicon mean for cloud pricing?

Microsoft isn't going to reduce pricing just because the company has cheaper inference hardware. That's not how cloud economics work. Instead, custom silicon creates new market segments and competitive dynamics.

What probably happens is this:

Segment 1: Standard inference on Maia 200 Microsoft offers inference capacity that's 15-25% cheaper than premium GPU-backed inference. This targets customers willing to use Microsoft's custom hardware.

Segment 2: Premium inference on Nvidia GPUs Clients needing specific Nvidia features, better support, or proven performance benchmarks pay a premium. This segment shrinks as Maia 200 proves itself, but doesn't disappear.

Segment 3: Training workloads Remains almost entirely dependent on Nvidia because custom silicon here is even more specialized and harder to justify economically.

The net effect is that cloud computing becomes slightly cheaper for inference-heavy workloads, but not because providers are racing to the bottom. It's because competition intensifies between different hardware options.

What probably also happens is that Nvidia cuts GPU pricing slightly to stay competitive. The company has enormous margins, so pricing pressure is survivable. But it's real.

Over a 5-10 year horizon, this dynamic favors cloud providers with diversified silicon strategies. Companies like Microsoft, Google, and Amazon can optimize costs for specific workload categories. Smaller cloud providers stuck buying Nvidia exclusively face declining margins.

This is actually good news for enterprises. More competition in hardware means more options. More options means better pricing. The flip side is that you need to understand trade-offs between different hardware types rather than just defaulting to whatever's most popular.

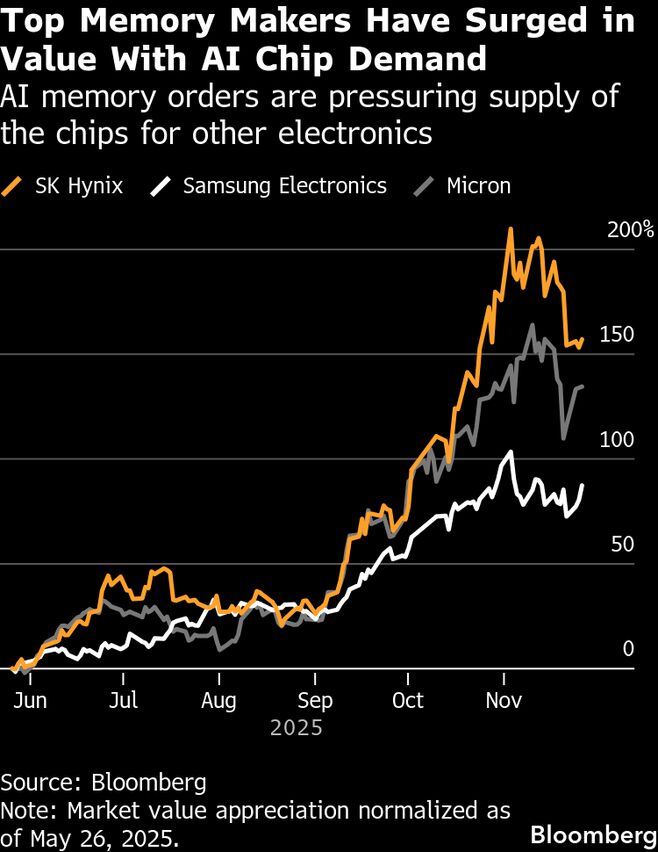

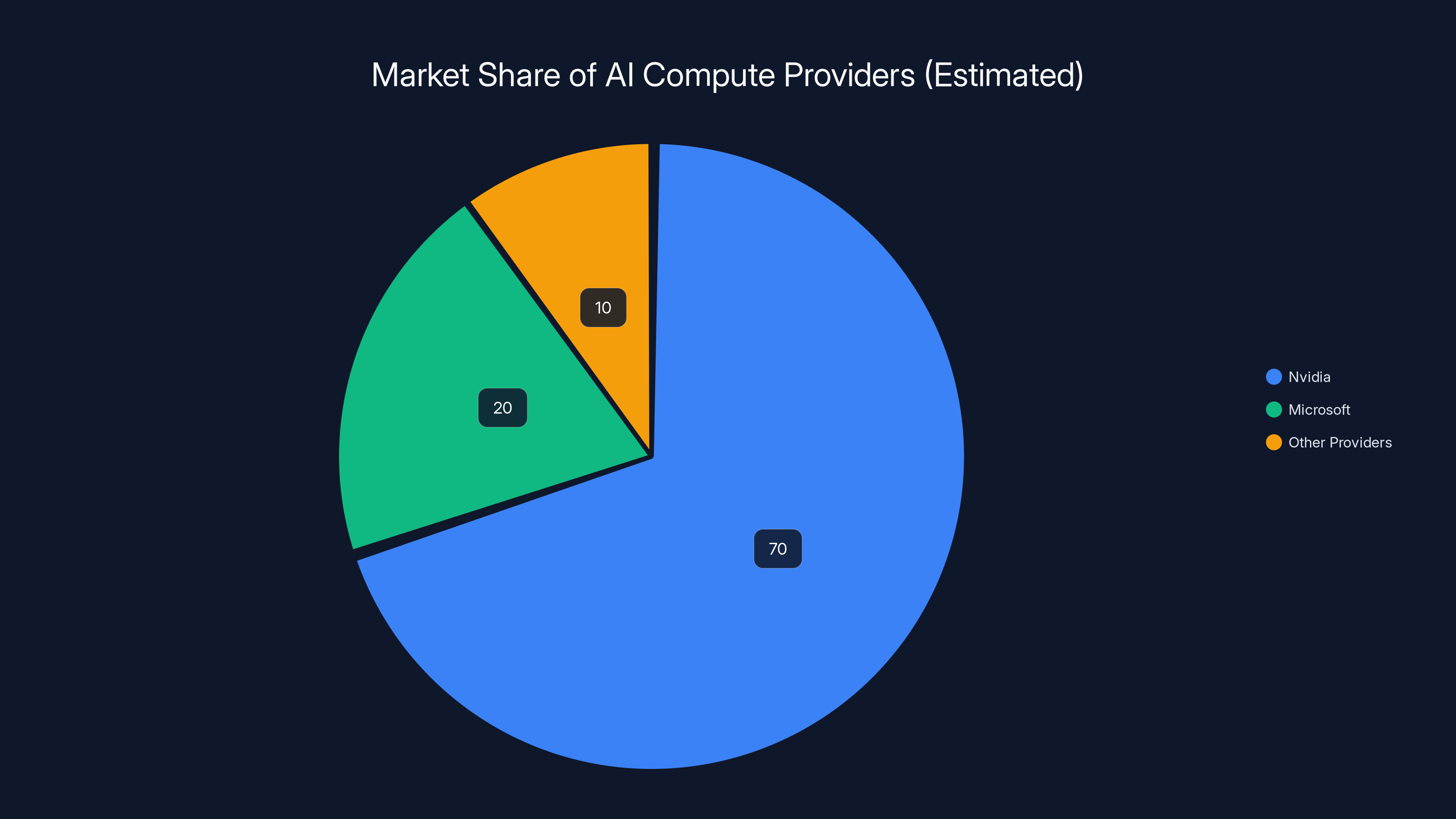

Nvidia holds the majority market share in AI compute, but Microsoft's entry with Maia 200 aims to diversify supply options. (Estimated data)

The Open AI Consideration: How Microsoft's Custom Silicon Supports Its AI Partnership

One detail from the original reporting deserves emphasis: Maia 200 will support Open AI workloads running on Azure.

Why is this important?

Microsoft has invested $13 billion into Open AI and deeply integrated the partnership into Azure. Azure is Microsoft's cloud platform. Open AI's models are exclusive to Microsoft for some capabilities. The entire strategy only works if Microsoft can offer best-in-class infrastructure for Open AI workloads.

If Microsoft relied exclusively on Nvidia GPUs, the company faces a problem: Nvidia controls the supply. If a supply crunch happens again (and it probably will), Microsoft can't guarantee capacity for its flagship Open AI offerings.

But with Maia 200, Microsoft gains negotiating leverage. The company can run Open AI workloads on either Nvidia or custom silicon. This lets the company guarantee capacity for customers. If supply gets tight, Microsoft routes workloads to Maia 200. If pricing gets aggressive, the company threatens to use more custom silicon.

This is ruthlessly practical competitive strategy. Microsoft isn't trying to maximize the number of custom chips in production. The company is trying to maximize its own optionality and ensure it can serve customers reliably.

Open AI benefits too. The more compute options Microsoft has, the better rates Microsoft can negotiate with other vendors, and the more capacity Microsoft can reserve. This means cheaper and more reliable compute for running Open AI models.

Scaling the Maia 200: From Limited Deployment to Production

Microsoft is deploying Maia 200 in "selected data centers," according to the reporting. This is deliberate language. It means the chip isn't everywhere yet. It's being tested in specific locations with specific workloads.

This makes sense from an operational perspective. You don't roll out new hardware globally until you've:

- Validated reliability: Run the chips under production load to catch thermal issues, reliability problems, or unexpected performance issues

- Trained operations teams: Your data center staff needs to understand how to maintain and troubleshoot new hardware

- Optimized software: Compilers, libraries, and frameworks need optimization for the new architecture

- Managed customer expectations: Not every workload works equally well on new hardware

The rollout pattern probably looks like this:

Phase 1 (Current): Selected internal deployments for Microsoft's own AI teams and carefully chosen early adopter customers. This phase focuses on validation and optimization.

Phase 2 (6-12 months): Broader deployment to Azure regions in North America and Europe. More customers get access, but workload selection remains selective.

Phase 3 (1-2 years): Global availability with production-ready software stacks. Maia 200 becomes a standard offering alongside Nvidia GPUs.

Phase 4 (2+ years): Maia 200 forms a meaningful percentage of Azure's total inference capacity.

This timeline is typical for major hardware rollouts. Google took 3-4 years to move TPUs from internal research to production-grade cloud offering. Amazon's custom silicon followed a similar trajectory.

The implication is that Maia 200 won't meaningfully impact Microsoft's Nvidia purchasing for at least 12-18 months. In fact, Microsoft probably continues buying similar or increased quantities of Nvidia GPUs during this period to meet growing overall demand.

The Competitive Response: What Nvidia and AMD Do Now

Here's a question that matters strategically: how do Nvidia and AMD respond to custom silicon from cloud providers?

The honest answer is: not with panic. At least not publicly.

Nvidia's position remains extremely strong. The company has:

- Overwhelming market share: 80%+ of the GPU market

- The best software ecosystem: CUDA, cu DNN, and thousands of third-party libraries

- Continuous innovation: New architectures every 18-24 months

- Enormous customer switching costs: Rewriting code for a new platform is hard

- Massive scale advantages: Investing more in R&D than any competitor

Custom silicon from cloud providers doesn't change any of these facts. It just adds one more competitor in a specific segment (inference on specific workloads) that Nvidia doesn't optimize for anyway.

But Nvidia isn't ignoring the trend either. The company is:

- Broadening the product line: New chips at different price points and performance levels

- Optimizing for inference: The L40 and newer products focus more explicitly on inference workloads

- Improving software: Better libraries and frameworks for common production scenarios

- Partnering with cloud providers: Working closely with Microsoft, Google, and Amazon to ensure Nvidia products remain best-in-class

AMD's position is different. The company has been fighting for GPU market share for years with mixed success. Custom silicon from cloud providers is threatening because it reduces the total addressable market for external GPU sales.

But AMD also benefits from custom silicon competition in subtle ways. When cloud providers develop their own chips, they discover specific optimization needs. AMD can potentially address those needs with specialized GPU products. Additionally, having multiple chip suppliers gives cloud providers more confidence negotiating with AMD.

The broader market dynamics actually favor AMD more than most analysts realize. As custom silicon proliferates, the market fragments. Fragmentation reduces Nvidia's dominance. AMD's goal isn't to beat Nvidia on every metric. It's to own specific niches where the company can compete effectively. Custom silicon creates more niches.

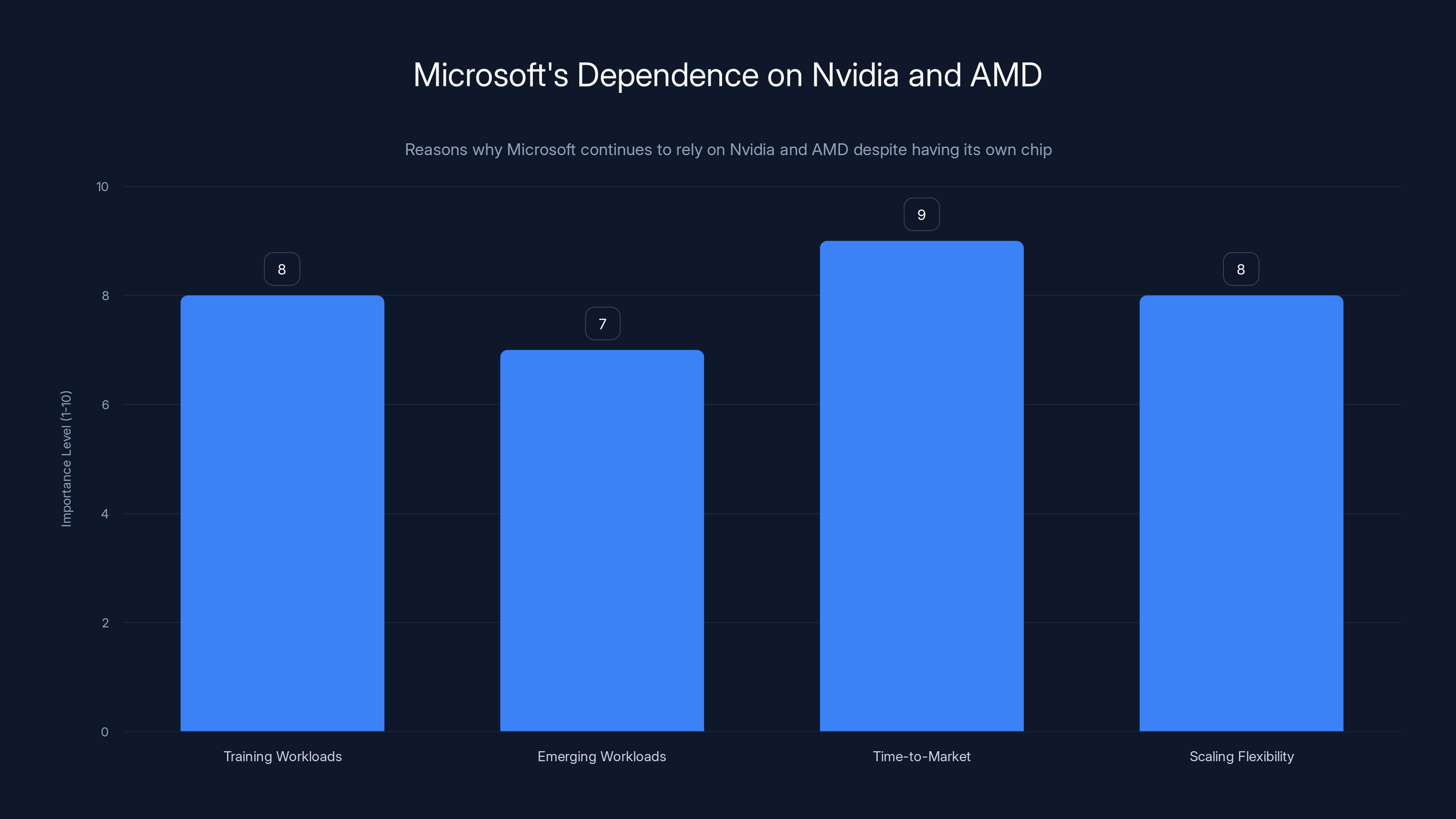

Microsoft continues to rely on Nvidia and AMD due to the high importance of training workloads, emerging workloads, time-to-market, and scaling flexibility. Estimated data based on narrative context.

Broader Implications: What This Means for the AI Infrastructure Industry

Zoom out to the 10,000-foot view. What does Microsoft's Maia 200 and the broader custom silicon wave mean for the industry?

First, it signals that the era of single-vendor dominance is over.

For decades, major infrastructure markets had one or two dominant vendors. Intel in CPUs. Nvidia in GPUs for deep learning. This simplified procurement but created leverage for the dominant vendor. Custom silicon breaks that pattern by enabling large consumers to build alternatives.

This doesn't mean Nvidia loses dominance in the next few years. But over a decade, we'll likely see fragmentation. Different cloud providers will optimize different types of chips. Enterprise customers will have real choices beyond "pay whatever Nvidia charges."

Second, it raises the barriers to entry for competing cloud providers.

Building custom silicon requires

The effect is paradoxical: custom silicon increases diversity in the hardware market, but it consolidates power among the mega-cap cloud providers. Only the biggest companies can afford this game.

Third, it changes the relationship between cloud providers and their customers.

When everyone uses Nvidia GPUs, cloud pricing is relatively transparent. You're buying a commodity. Margins are thin. Competition is price-based.

When cloud providers have custom silicon, pricing becomes murkier. Different providers have different cost structures. A workload that's cheap on Azure might be expensive on AWS, depending on chip optimization. This creates opportunities for cloud providers to differentiate on price-to-performance for specific workloads.

Smarter customers will optimize workload placement. Less savvy customers might leave money on the table.

Fourth, it creates new software engineering challenges.

When all GPUs are Nvidia, your code ports relatively easily. With custom silicon from different providers, each with different architectures, you face fragmentation.

Compile once, run anywhere? Forget it. Code written for Maia 200 might not run optimally on Google TPUs or Amazon Trainium. Developers need to choose which platform to target, or spend extra effort optimizing for multiple backends.

This isn't new—it's how the software industry always works. But it's a friction point that didn't exist when Nvidia had monopoly power.

Future Generations: What Comes After Maia 200

Microsoft didn't announce Maia 200.5 or Maia 300 explicitly, but the company will definitely build next-generation silicon.

History suggests the trajectory:

Generation 2 (2026-2027): Likely focused on training-specific optimizations. Maia 200 does inference well, but Microsoft will eventually want custom silicon for training workloads too. This is harder to build but strategically important.

Generation 3 (2027-2028): Potentially multi-chip designs. Just like CPUs evolved from single-core to multi-core, future AI accelerators might combine inference, training, and general-purpose compute on a single package.

Generation 4 (2028+): Novel architectures exploring memory types (HBM3, HBM4), interconnects (chiplet-based designs), and software innovations we haven't seen yet.

Each generation becomes more ambitious and more capital-intensive. This is why partnerships with established vendors remain critical. You need Nvidia's money funding GPU innovation to force the industry forward.

The companies that win long-term aren't those that bet everything on custom silicon. They're the ones that combine custom silicon with best-in-class external partnerships. Microsoft is executing that strategy correctly.

The Geopolitical Dimension: Why Supply Diversity Matters

Here's something worth mentioning that doesn't get enough attention: custom silicon development is partially driven by geopolitical concerns.

Advanced semiconductors depend on global supply chains. Taiwan manufactures most advanced chips. China is restricted from accessing certain technologies. The US has imposed sanctions on advanced chip exports. The situation is genuinely fragile.

If US-China tensions escalate, or if Taiwan experiences political disruption, global semiconductor supply could face major shocks. Companies that rely entirely on Nvidia are extremely vulnerable because Nvidia relies entirely on these same global supply chains.

By developing internal capabilities, Microsoft reduces dependency on any single supplier or country. The company still depends on contract manufacturers like TSMC for actual production, but having its own designs provides strategic flexibility.

This geopolitical dimension doesn't drive all custom silicon development, but it's a factor. It's why companies are willing to spend billions developing chips that provide only 20-30% efficiency gains. The upside isn't just better performance. It's resilience.

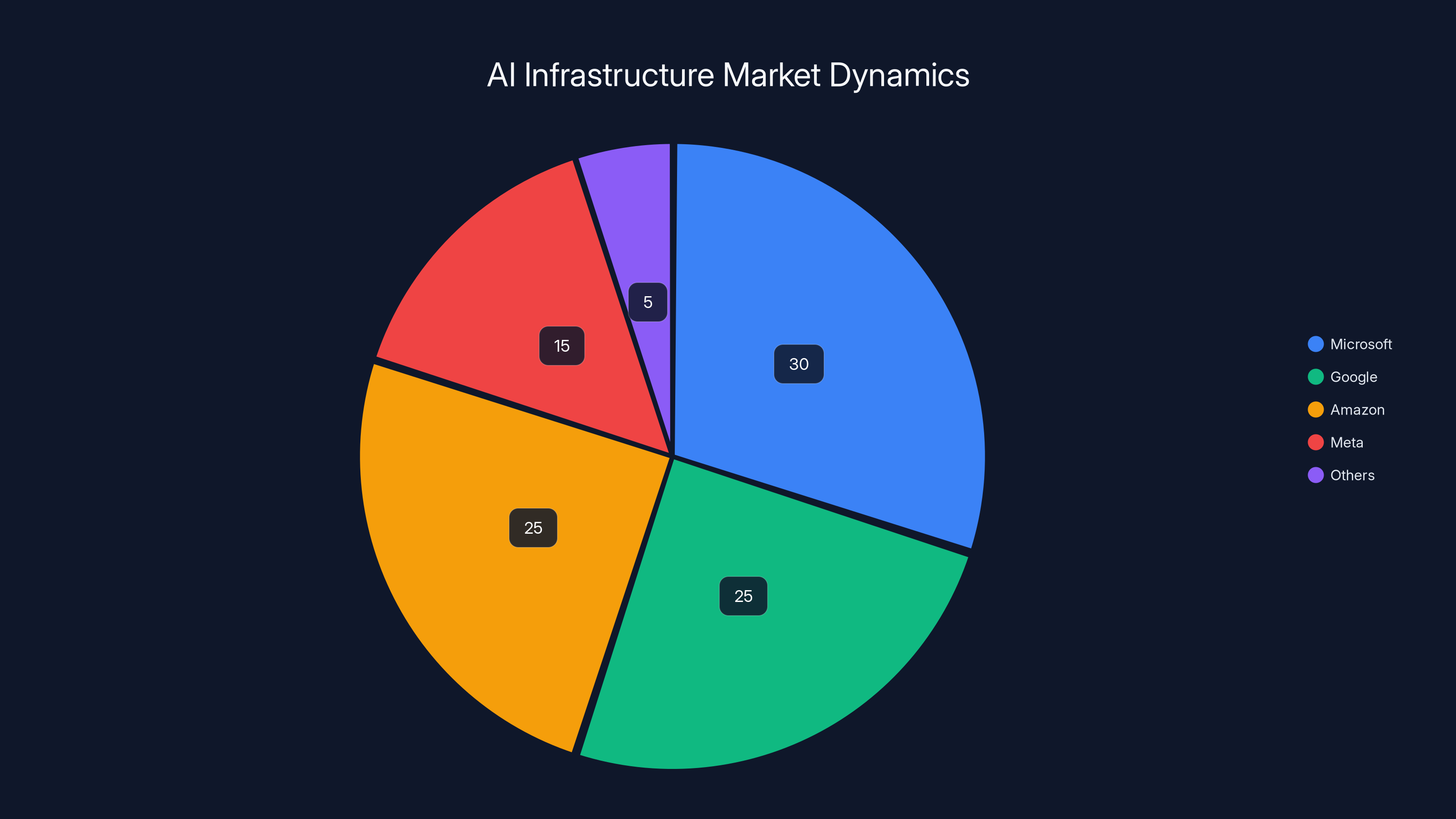

The AI infrastructure market is expected to see increased diversity in hardware but consolidation among major cloud providers. Estimated data reflects potential market share shifts due to custom silicon adoption.

Comparing Custom Chips: Who's Building What

Let's do a quick survey of what different companies are building:

Microsoft Maia 200: Inference-optimized, launched 2024, deployed selectively, focuses on memory bandwidth

Google TPU (Fifth generation): Originally for training, now spanning inference to specialized tasks, deeply integrated with Tensor Flow and JAX

Amazon Trainium: Training-focused, optimized for Py Torch and Tensor Flow, available since 2021

Amazon Inferentia: Inference-focused, optimized for deployment, launched earlier than Trainium

Meta MTIA: Started internal, gradually opening to external customers, balanced design for both training and inference

Cerebras Wafer Scale Engine: Novel design with a giant chip covering an entire wafer, focused on training

Graphcore IPU: Novel architecture with hybrid training-inference capability, struggled to achieve market traction

The pattern is clear: everyone is building, everyone is different, and most are complementary to Nvidia rather than replacements.

What's worth noting is that some companies (Graphcore, Cerebras) tried radical new architectures. Graphcore invented a completely different processor design called the IPU. Cerebras built an insanely large monolithic chip.

Both companies found that radical innovation makes it hard to compete against Nvidia's mature ecosystem. It's easier for cloud providers like Microsoft and Google because they can control the software stack and drive adoption through their platforms.

How Organizations Should Think About This

If you're running AI workloads on cloud platforms, how should you think about custom silicon?

Don't over-rotate on it yet. Maia 200 is still being deployed selectively. For most use cases, Nvidia GPU options remain the safe choice. This changes in 2-3 years, but not today.

Understand your workload. Is it training or inference? Memory-bound or compute-bound? Batch processing or real-time prediction? Different workloads suit different hardware. Don't assume your current setup is optimal just because it's what everyone uses.

Build flexibility into your code. Abstract away hardware-specific optimizations. Use frameworks like ONNX that can compile to multiple targets. Make it easy to switch between chip types without rewriting everything.

Monitor cloud provider hardware announcements. When Google, Microsoft, or Amazon announce new silicon, evaluate it for your specific workload. You might find cost or performance improvements you're leaving on the table.

Negotiate with your cloud provider. As custom silicon becomes available, you have more bargaining power. Cloud providers want to push customers toward their own chips to improve margins. Exploit this competition to negotiate better pricing on Nvidia-based compute.

The Question Nobody Can Answer Yet: Will This Work?

Here's the truth: we don't know if Maia 200 will be successful. We don't know if any custom silicon effort will achieve meaningful market penetration.

There are reasons for skepticism:

- Unproven at scale: Real production workloads are messier than benchmarks

- Software maturity: Nvidia has decades of CUDA development. Custom chips need comparable tooling

- Talent scarcity: Building chip-optimized applications requires specialized skills. Microsoft doesn't have enough experts

- Customer inertia: People know how to build for Nvidia. They don't know how to optimize for Maia 200

But there are also reasons for confidence:

- Strong economic incentives: Microsoft would save billions if the chip works

- Focused target: Inference is a specific enough problem that the company can optimize well

- Proven methodology: Google's TPUs show that custom silicon can work at scale in cloud platforms

- Strong execution: Microsoft has the engineering talent and resources to pull this off

Most likely scenario: Maia 200 will be moderately successful. It'll power a meaningful percentage of Azure's inference workloads within 3-5 years. It won't replace Nvidia, but it will reduce Microsoft's dependence on external vendors and improve the company's competitive position.

This outcome is already valuable. Microsoft doesn't need custom silicon to be world-changing. It just needs to work reliably on Microsoft's own use cases. Success at that level delivers real strategic value.

Why This Matters for the Future

Microsoft's Maia 200 is more interesting than just a new chip. It represents a shift in how technology infrastructure is built.

For the past decade, cloud computing architecture was determined by what Nvidia built. Workloads had to fit GPU capabilities. Optimization meant CUDA programming. Procurement meant paying Nvidia's prices.

Now cloud providers have agency. They can design silicon for their actual workloads instead of adapting workloads to available hardware. Over time, this creates better infrastructure.

It also creates more competition. Nvidia's dominance was so complete that it became hard to imagine alternatives. But alternatives are emerging. Within a decade, Nvidia might control 60% of the AI accelerator market instead of 85%. That's still dominant, but it's not monopolistic.

This dynamic applies beyond chips. As custom silicon becomes normal, cloud providers will develop more custom infrastructure. Custom networking. Custom storage. Custom everything. The industry moves from "assembling components from vendors" to "integrating purpose-built systems." Microsoft is just the first major player getting serious about this transition.

Satya Nadella's comment about being "ahead for all time to come" captures this perfectly. In a fast-moving industry, you can't just build once and hope it works. You have to keep innovating, keep improving, keep pushing forward. Custom silicon is one tool in that broader strategy.

For customers, this is mostly good. More competition means better pricing, more choices, and better tailored solutions. The downside is complexity. You need to understand hardware trade-offs instead of just picking the most popular option.

But complexity is a price worth paying for better technology.

FAQ

What is Microsoft's Maia 200 chip?

Maia 200 is Microsoft's custom-designed AI accelerator chip optimized specifically for inference workloads on large language models. Unlike general-purpose GPUs, Maia 200 is designed to excel at moving data between memory and compute units efficiently, making it ideal for running trained models at scale. The chip is currently being deployed in selected Microsoft data centers to power Azure's AI services and internal AI research.

Why did Microsoft build its own AI chip if Nvidia GPUs already exist?

Microsoft built Maia 200 primarily due to supply constraints and cost optimization needs. During the AI boom, Nvidia couldn't manufacture enough GPUs to meet demand, forcing cloud providers to seek alternatives. Additionally, custom silicon optimized for specific workloads like inference can deliver 20-30% better efficiency than general-purpose GPUs, which translates to significant cost savings at cloud scale. A 25% efficiency improvement on 100,000 GPUs saves hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Will Microsoft stop buying Nvidia and AMD chips now that it has its own hardware?

No. CEO Satya Nadella explicitly confirmed that Microsoft will continue buying from both Nvidia and AMD despite launching Maia 200. This is because no single chip excels at all AI workloads. Maia 200 is optimized for inference, but training, emerging applications, and diverse customer needs require access to multiple hardware types. Maintaining vendor relationships also provides supply flexibility and ensures Microsoft can always meet customer demand.

How does Maia 200 compare to Nvidia's GPUs in performance?

Maia 200 isn't designed to beat Nvidia across the board. Instead, it's optimized for specific inference patterns where memory bandwidth is the bottleneck. For these workloads, internal benchmarks suggest 20-30% performance advantages, but independent verification is limited. For training, Nvidia GPUs remain superior. Maia 200 and Nvidia hardware are complementary, not competitive, in Microsoft's strategy.

When will Maia 200 be widely available to Azure customers?

Microsoft is currently deploying Maia 200 in selected data centers. Broader availability will likely follow a phased rollout over 12-24 months, similar to how Google introduced TPUs. Customers should expect selective availability by mid-2025, expanding to most regions by 2026. During this rollout, Nvidia GPU options will remain the primary inference offering.

How does Maia 200 affect cloud pricing for AI workloads?

Custom silicon introduces competition into the inference market, likely pushing prices down slightly as cloud providers compete on efficiency. However, pricing won't drop dramatically because cloud providers still need to fund custom silicon R&D and maintain relationships with external vendors. Expect a modest decrease in inference costs over 2-3 years as competition intensifies, with the biggest savings for customers willing to use a mix of chip types.

Why do other cloud providers like Google and Amazon also build custom silicon?

Every major cloud provider faces the same constraints: massive AI workload demand, supply constraints on traditional GPUs, and opportunities to optimize for specific use cases. Google started with TPUs for internal research around 2016, then productized them. Amazon followed with Trainium and Inferentia. Meta developed MTIA. Each company follows similar logic: custom silicon provides cost advantages, supply independence, and competitive differentiation that justify the R&D investment.

Does custom silicon from cloud providers compete with Nvidia directly?

Not really. Custom silicon fills niches that Nvidia doesn't optimize for (like inference-focused workloads), rather than replacing Nvidia's general-purpose GPUs. Nvidia still dominates GPU market share and continues innovating rapidly. The better way to think about it is fragmentation rather than replacement. Nvidia's dominance decreases from 85% to 60-70% market share over time, but the company remains the largest player.

What about Mustafa Suleyman's Superintelligence team getting first access to Maia 200?

This allocation is strategic rather than exclusive. Suleyman's team leads Microsoft's most advanced AI research, so they're the ideal first users to validate the hardware and identify optimization opportunities. Success with cutting-edge use cases builds confidence that Maia 200 works for production workloads. External customers will eventually get access, but only after the chip proves itself on Microsoft's internal workloads.

How long until custom silicon significantly impacts Nvidia's market position?

Realistic timeline is 3-5 years for meaningful impact. Maia 200 won't replace Nvidia in any major workload category. Instead, it'll reduce Microsoft's Nvidia spending by 10-20% in certain categories and inspire similar efforts by other cloud providers. Over a decade, custom silicon probably limits Nvidia's market share growth rather than shrinking current dominance. The company will remain profitable and dominant, just less dominant than today.

Conclusion: The Hardware Strategy That Defines Cloud's Future

Microsoft's Maia 200 tells a bigger story than just a new chip. It reveals how technology infrastructure is evolving in the age of AI.

For decades, compute was determined by what major vendors built. You adapted your workloads to available hardware. You paid prices set by monopolistic suppliers. Innovation happened in the vendor's labs, not your data center.

Custom silicon changes this equation. Now large organizations can say: here's how we actually run workloads, build hardware optimized for that, and achieve dramatic efficiency gains. This shift happens slowly, but it's inevitable.

Satya Nadella's statement about needing to be "ahead for all time to come" captures this reality perfectly. In fast-moving technology, you can't build once and relax. You need to continuously innovate, continuously improve, continuously push forward. Custom silicon is one tool in that strategy.

What makes Microsoft's approach smart is that the company isn't betting everything on internal silicon. Maia 200 is an addition to the strategy, not a replacement. Microsoft continues buying from Nvidia and AMD, continues building partnerships, continues maintaining optionality.

This isn't risk aversion. It's sophisticated strategy. By building custom silicon for specific problems while maintaining vendor relationships for everything else, Microsoft gains more flexibility than pursuing either path exclusively.

The impact will unfold slowly. In 2025, Maia 200 remains a specialized offering in selected data centers. By 2027, it's a standard option alongside Nvidia GPUs. By 2030, it probably powers 15-25% of Azure's AI compute.

But here's what matters most: customers benefit. More competition in hardware means better pricing, better service, and better technology. The days of single-vendor dominance in AI infrastructure are ending. What replaces it isn't chaos, but a more competitive and innovative ecosystem.

Microsoft's Maia 200 isn't revolutionary. It's not going to defeat Nvidia. But it's the opening move in a new game where cloud providers control more of their own destiny. And that game, ultimately, benefits everyone using cloud infrastructure.

The race for AI hardware is accelerating. Nvidia will compete harder. AMD will push harder. Google, Amazon, and Meta will invest more aggressively in their own silicon. All of this competition drives innovation forward.

Microsoft understood this early and moved decisively. That decisiveness, not the technical specifications of Maia 200, is what makes this moment significant for the future of cloud infrastructure.

Key Takeaways

- Microsoft's Maia 200 is an inference-optimized chip designed for specific workloads, not a replacement for Nvidia's general-purpose GPUs

- Supply constraints during 2023-2024 AI boom forced cloud providers to develop custom silicon as strategic hedge, not as primary solution

- Satya Nadella's 'ahead for all time to come' statement reflects reality that staying competitive requires continuous innovation across multiple hardware types

- Custom silicon development will gradually fragment the $126 billion AI accelerator market, reducing Nvidia dominance from 85% toward 60-70% over 5-10 years

- Cloud providers with diverse silicon strategies (Microsoft, Google, Amazon) gain negotiating leverage and supply flexibility that single-vendor dependent competitors cannot match

Related Articles

- SpaceX's 1 Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]

- Enterprise AI Race: Multi-Model Strategy Reshapes Competition [2025]

- TikTok's Oracle Data Center Outage: What Really Happened [2025]

- TikTok Outages 2025: Infrastructure Issues, Recovery & Platform Reliability

- Thermodynamic Computing: The Future of AI Image Generation [2025]

- NVIDIA's $100B OpenAI Investment: What the Deal Really Means [2025]

![Microsoft's Maia 200 AI Chip Strategy: Why Nvidia Isn't Going Away [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-s-maia-200-ai-chip-strategy-why-nvidia-isn-t-going/image-1-1770066424601.jpg)