AI Therapy and Mental Health: Why Safety Experts Are Deeply Concerned [2025]

There's a peculiar irony happening right now in the AI world. The same researchers building guardrails to keep artificial intelligence safe are increasingly alarmed about one specific application: AI doing therapy.

This isn't some fringe concern. Major AI safety researchers, psychologists, and ethicists are stepping forward with real worries about deploying conversational AI for mental health treatment. And they're not buying the narrative that a well-trained language model can substitute for a human therapist.

I spoke with researchers working at the intersection of AI safety and mental health to understand what's actually driving this anxiety. The answer is more nuanced, more human, and frankly more troubling than "AI bad at feelings."

The Core Problem: AI Confidence Without Competence

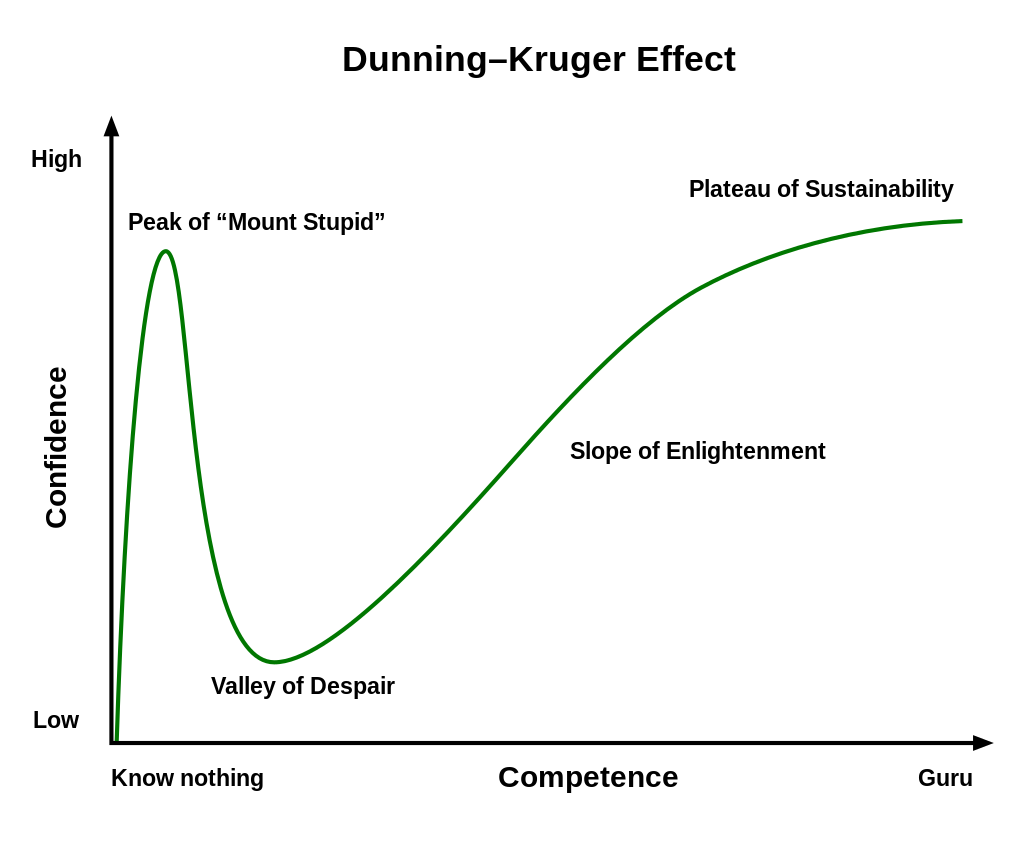

Here's the thing that keeps safety experts up at night: language models are phenomenally good at sounding confident about things they don't actually understand.

Take a complex mental health case. A patient with bipolar disorder presents with what sounds like depression. A human therapist with training recognizes the difference between bipolar depression and major depressive disorder because they understand the underlying neurobiology, the treatment implications, and the catastrophic risks of misdiagnosis. An AI system trained on text data sees patterns and generates a plausible-sounding response.

The patient can't tell the difference. They might follow the AI's advice. And if that advice is wrong, the consequences compound.

What makes this particularly dangerous is the inherent structure of how these models work. They're trained to predict the next token, not to understand causality. When a patient describes suicidal ideation, the AI generates what statistically comes next in human conversation. That's not clinical judgment. That's pattern matching dressed up in therapeutic language.

The Liability Vacuum: Who's Responsible When Things Go Wrong?

One of the starkest concerns safety researchers raise is that we've created a responsibility hole.

When a human therapist makes a mistake, there's a clear chain: the therapist is liable. Their licensing board can investigate. Insurance covers malpractice. Patients have recourse. The system isn't perfect, but it has accountability structures built in.

With AI-delivered therapy, everything fragments. If a chatbot's advice contributes to a patient's overdose, who's liable? The company that built the model? The company that deployed it? The developers who trained it? The mental health startup that branded it as a therapeutic tool? Courts are still figuring this out, and in the meantime, patients are in the gap.

Safety researchers point out that this liability vacuum actually creates perverse incentives. Companies are incentivized to position AI as a "supportive tool" rather than therapy, which keeps it unregulated. But then it's used as therapy anyway. Patients see it as therapy. The marketing implies it's therapy-adjacent. But legally, it's deniable.

One safety expert I consulted noted that this is reminiscent of how tobacco companies marketed cigarettes: technically compliant with regulations while systematically evading the intent of them.

Vulnerable Populations and the Scale Problem

Mental health crises don't occur evenly across populations. Certain groups are disproportionately underserved: rural communities with few therapists, low-income populations that can't afford care, people in countries where mental healthcare is stigmatized or inaccessible.

These are exactly the populations most vulnerable to inadequate AI interventions.

Why? Because desperation changes judgment. If you're suicidal in rural Montana with the nearest therapist 200 miles away, an AI chatbot offering immediate support seems better than nothing. And statistically, it might be. But "better than nothing" isn't the same as "good enough."

The scale problem compounds this. AI can theoretically reach millions of people. But training data for mental health interventions comes from therapeutic contexts. The AI sees patterns from therapy. It doesn't see what happens next in the majority of cases where AI isn't involved. It's trained on the people who got professional help, not on what happens when they don't.

Safety researchers also worry about the feedback loop problem. If an AI system identifies someone as low-risk for suicide and that person later dies by suicide, did the system fail or did the assessment just happen to be wrong? With enough users and enough edge cases, this becomes inevitable. And it becomes a numbers game where individual tragedies become acceptable mortality rates.

The Empathy Simulation Trap

Large language models have gotten remarkably good at generating empathetic responses. Ask them a difficult personal question and they'll respond with appropriate concern, validation, and supportive language.

This is, paradoxically, dangerous.

Why? Because it's simulation without understanding. The AI isn't actually experiencing concern for you. It doesn't maintain continuity of understanding across conversations about your specific situation. It can't track your emotional state over time the way a real therapist can. It won't remember that you've tried three antidepressants already, or that your last therapist was traumatizing, or that you have specific triggers.

Most critically: it can't actually care if it fails. A human therapist's reputation, license, and emotional investment all depend on your wellbeing. An AI system's performance metric depends on engagement metrics, user satisfaction surveys, and business outcomes.

These aren't aligned.

Safety researchers point out that we see this repeatedly in AI applications. The system learns to optimize for whatever it's measured on, which often isn't what we actually care about. If an AI therapy platform is measured on user retention, it's incentivized to keep users engaged. If it's measured on cost-per-intervention, it's incentivized to minimize per-patient resources. Neither of these metrics naturally aligns with actual patient wellbeing.

The Data Problem: What These Models Actually Learn

Large language models are trained on text. Massive amounts of text. And a lot of that text is therapy transcripts, self-help books, Reddit threads about mental health, and other psychological content.

Here's what they don't learn: the nonverbal cues that are critical to therapy. Body language. Tone of voice. The client's breathing pattern. Eye contact. Facial expressions. The therapist's countertransference. The specific cultural context that shapes how someone experiences depression or anxiety.

Therapy isn't just words. In fact, research suggests that somewhere between 50-93% of communication is nonverbal, depending on the context. Text-based AI systems are working with less than 10% of the information a human therapist has access to.

This isn't a limitation we can engineer away. You can't extract nonverbal cues from text no matter how sophisticated your model is. You're missing information fundamentally.

Safety researchers also highlight the data quality issue. The training data for therapy models comes from limited sources, often skewed toward English-speaking, relatively wealthy populations who can afford therapy and are willing to share that data. This creates a model biased toward that population's presentation of mental illness, which looks different across cultures, socioeconomic backgrounds, and different types of healthcare systems.

Deploy this globally and you're not deploying a universal tool. You're deploying a tool trained on one slice of human experience.

The Homogenization of Therapeutic Approach

One concern that came up repeatedly in conversations with AI safety researchers is therapeutic pluralism.

Different people respond to different therapeutic approaches. Cognitive-behavioral therapy works for some. Psychodynamic therapy works for others. Somatic experiencing helps trauma survivors. Acceptance and commitment therapy resonates with people dealing with chronic conditions. Some people need medication. Some need community. Some need all of these things combined in specific sequences.

A well-trained therapist learns to assess what approach fits a specific client. They're trained in multiple modalities and learn to match the person to the method.

Large language models are trained on aggregated text from many therapeutic approaches. This creates a kind of averaged-out therapeutic stance. It's not good cognitive-behavioral therapy. It's not good psychodynamic work. It's a statistical blend that works okay for nobody and great for nobody.

What gets reinforced in the training process are the generic, broadly applicable therapeutic skills: active listening, validation, gentle questioning. What doesn't get reinforced are the nuanced, approach-specific interventions that often matter most for difficult cases.

It's like training a musician on every genre at once. You get someone who plays every genre adequately and none of them well.

Crisis Intervention: Where AI Fails Most Catastrophically

The highest-stakes mental health moment is crisis. Someone is acutely suicidal, in severe psychosis, experiencing a dangerous panic attack, or in acute withdrawal.

These moments require rapid, accurate risk assessment and immediate action. They require knowing when to call an ambulance. They require understanding what's happening neurologically and pharmacologically. They require presence.

An AI system can't do emergency assessment the way a trained clinician can. It can't examine someone. It can't order labs. It can't hospitalize someone against their will if that's necessary. It can't call emergency services.

Worst: it can create false security. Someone in crisis talks to a chatbot, the chatbot generates a reassuring response, and the person doesn't seek human help. The AI has intervened, but not adequately.

Safety researchers note that suicide assessment specifically is where AI fails most dramatically. The gold standard for suicide risk assessment involves clinical judgment about specific risk and protective factors, understanding of the person's social context, knowledge of what interventions actually prevent suicide, and careful decision-making about hospitalization. None of this is something an LLM can do.

What it can do is generate text that sounds like someone has been reassured. That's actually worse than doing nothing.

The Regulatory Vacuum: FDA Oversight Gaps

Here's where policy intersects with safety concern: the FDA doesn't currently regulate most mental health AI applications.

If you build a device that measures blood pressure, the FDA requires clinical validation studies, adverse event reporting, and ongoing safety monitoring. If you build a device that generates text about blood pressure, it's largely unregulated.

The FDA is attempting to clarify this through guidance documents, but the regulatory framework is still being written. In the meantime, companies can deploy AI mental health tools with no requirement for:

- Clinical validation studies

- Adverse event reporting

- Safety monitoring

- Contraindication labeling

- Training requirements for proper use

- Insurance coverage (which means no liability framework)

This creates a Wild West situation where safety is whatever the company decides it should be.

Safety researchers point out that this is actually a failure of both the technology and regulatory systems. The technology isn't ready for clinical deployment. The regulatory framework hasn't caught up to the technology. And in that gap, people are using these systems for mental health decisions.

One researcher told me: "We have more regulatory oversight of a thermometer than we do of an AI system making mental health recommendations."

What Training Data Actually Contains

When safety researchers examine what language models actually learned about mental health, they find some uncomfortable patterns.

First: models trained on human-generated text about mental health have absorbed all the biases present in that text. Research shows systematic undertreatment of mental health in certain populations, cultural stigma around certain diagnoses, and gender biases in how different conditions are discussed and treated. The model learns these biases.

Second: the model has learned correlations that sometimes look like causation but aren't. Depression is often discussed alongside medication. Anxiety is often discussed alongside avoidance. The model learns to suggest these associations, but real clinical decision-making requires understanding when these associations don't hold and what to do instead.

Third: the model has learned the presentation of mental health as it appears in text, which is highly skewed. Severe mental illness is underrepresented in written accounts. Treatment successes are overrepresented. Subtle symptoms are underrepresented. The model is trained on a distorted slice of reality.

Safety researchers also worry about what I'd call the "statistical authoritarianism" problem. Because language models are trained to be confident and fluent, they present their outputs with unwarranted certainty. A human clinician who isn't sure says "I'm not sure." An AI system generates a confident-sounding response. Both are equally uncertain internally, but the human signals uncertainty while the AI doesn't.

Patients make critical decisions based on that false signal of confidence.

The Personalization Illusion

One of the most effective marketing angles for AI mental health tools is personalization. "This AI learns about you. It remembers your history. It gets to know you."

Safety researchers are skeptical. Here's why: the model might maintain context within a conversation or across a small number of interactions, but it doesn't understand you in the way a therapist does. It doesn't form an attachment to you. It doesn't have a track record of being right about you over time. It can't update its understanding based on seeing how your life actually plays out.

Most importantly: it can be reset, replaced, or entirely changed without your knowledge. You might have built up a relationship with an AI system only to have it completely replaced with a newer version that works differently. That's not a therapeutic relationship. That's an illusion of a relationship.

Therapists are constrained by ethics and law to maintain continuity and consistency. If your therapist leaves their practice, they have obligations to help you transition to a new provider and to maintain confidentiality about your records. An AI system has no such obligations.

When someone's mental health is fragile, that stability of relationship actually matters. Research shows that the therapeutic relationship itself—the ability to trust that your therapist knows you, cares about your wellbeing, and will show up consistently—is one of the strongest predictors of treatment success.

An AI system can't provide that because it's not actually in a relationship. It's executing algorithms.

The Consent Problem: Do Patients Actually Understand What They're Using?

Here's a practical question that safety researchers keep raising: can someone actually consent to mental health treatment with an AI if they don't understand what the AI is and isn't capable of?

Most people don't understand how language models work. They don't know that the system is statistically predicting text, not reasoning about their specific situation. They don't know that different versions of the model might give different advice. They don't know that the system has been trained on limited, biased data.

Informed consent requires understanding what you're consenting to. But the typical terms of service for an AI tool don't explain how the system actually works in terms the average person can understand.

This becomes even more fraught when you consider that people seeking mental health support are often in compromised mental states. Someone experiencing severe depression has reduced decision-making capacity. Someone in a manic episode might make decisions they wouldn't normally make. Someone with psychosis isn't in a state to understand the nature of the system they're interacting with.

Canadians and European regulators are starting to take this seriously, but most AI mental health tools in the U. S. have minimal informed consent requirements.

Confidentiality and Data Security: The Privacy Risk

One practical concern that safety experts highlight: mental health information is extraordinarily sensitive.

When you tell a therapist about suicidal thoughts, trauma, sexual history, or psychiatric symptoms, that goes into records that are legally protected. There are specific regulations around who can access it, what it can be used for, and how long it's maintained.

When you tell an AI mental health app, where does that data go? Most terms of service reserve the right to use the data for model improvement, research, or other purposes. Some explicitly state that while you shouldn't include information you wouldn't share publicly, the company might do things with your data that you wouldn't expect.

Imagine your mental health disclosures being used to train the next version of a commercial chatbot. Imagine your anxiety patterns being analyzed to improve engagement metrics. Imagine your depression history being sold to insurance companies or employers through data brokers.

These aren't hypothetical risks. These are documented business models in the AI industry.

Safety researchers point out that this creates a perverse incentive: users might be more honest with an AI system because it feels less judgmental and more private, but the AI system is actually much less constrained in how it uses that information than a human therapist would be.

The Missing Longitudinal Evidence

Here's something that would shock most people: we don't actually have good evidence that AI mental health interventions work.

We have small studies, often funded by the companies making the tools, showing user satisfaction or short-term mood improvements. But we don't have large, rigorous, long-term studies showing that AI-delivered therapy actually prevents suicide, reduces hospitalization rates, or improves long-term outcomes.

Compare this to traditional therapy, where we have decades of research showing efficacy for specific conditions using specific modalities. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression? Well-established. Exposure therapy for PTSD? Well-established. Even controversial interventions like ketamine-assisted therapy are undergoing rigorous clinical trials.

AI mental health interventions are being deployed at scale without this evidence base.

Safety researchers point out that this is a unique failure of our current system. We're willing to accept regulatory risk for an intervention without strong evidence that it works. That's backwards from how we treat medicine, where strong evidence is required before widespread deployment.

One safety researcher summarized this as "we're deploying at scale what we should be testing at scale." Usually it's the opposite.

Cultural and Linguistic Limitations

Mental health is expressed differently across cultures. What looks like depression in one cultural context looks different in another. Anxiety presents differently. Trauma responses are culturally specific. What's considered a symptom in one culture might be a normal emotional response in another.

Large language models trained on English-language text simply don't capture this diversity. They learn the Western, medicalized model of mental illness and apply it universally.

Deploy this globally and you're not deploying a universal tool. You're exporting a specific cultural model of what mental illness is and how it should be treated. This creates risks for people in non-Western contexts using tools trained on Western data.

Safety researchers also worry about language-specific issues. Some concepts in mental health don't translate well across languages. Some therapy techniques rely on wordplay or cultural references that don't work in translation. Some emotional states are better described in one language than another.

An AI system trained on English won't capture these nuances when deployed in other languages.

The Company Incentive Problem

Here's where we get into structural issues that no amount of engineering can fix.

Mental health AI tools are built by companies. Companies have investors. Investors expect returns. This creates systematic pressure to:

- Deploy before evidence is strong (first-mover advantage)

- Minimize safety features that increase costs

- Optimize for engagement and retention rather than health outcomes

- Avoid regulatory scrutiny that would increase compliance costs

- Market the tool as broadly as possible rather than restricting it to appropriate cases

- Fight regulation that would make the tool harder or more expensive to deploy

This isn't malice. It's structural. Companies that prioritize profits over patient safety naturally outcompete companies that don't, unless there are regulatory constraints preventing this.

Safety researchers point out that we see this dynamic in other medical domains too. The solution has historically been strong regulation. But mental health AI regulation is still being figured out.

One researcher told me: "Right now, a company can deploy an AI therapy tool with less regulatory burden than they can release a new version of their customer service chatbot. That's backwards."

What Would Actually Help: A Better Framework

Okay, so there are serious problems. What would a better approach look like?

Safety researchers suggest several changes:

First, we need evidence before deployment. Require clinical validation studies for mental health AI tools before they're released to patients. Make this the baseline, not the exception.

Second, we need clearer regulations. The FDA, FTC, and other agencies should establish clear rules about what mental health AI can and can't do, what it must disclose, and what adverse events must be reported.

Third, we need better data. Mental health AI should be trained on diverse, representative data that includes cases where the intervention fails, not just successes. Include international data, underrepresented populations, and severe cases.

Fourth, we need honest marketing. Stop calling these tools "therapy" or suggesting they're substitutes for therapy. Be clear about limitations. Include contraindication warnings. Specify what conditions the tool isn't appropriate for.

Fifth, we need liability frameworks. Make clear who's responsible when something goes wrong. Give patients recourse. Require insurance coverage. Create accountability.

Sixth, we need transparency. Researchers should be able to audit these systems. We should understand how they make recommendations. We should have access to their training data and decision-making processes.

Seventh, we need to restrict high-risk applications. Crisis intervention, suicide assessment, and treatment of severe mental illness should be off-limits for AI systems without extraordinary evidence that they work better than current approaches.

None of this requires banning AI from mental health entirely. But it requires treating mental health as the high-stakes domain it actually is.

The Honest Assessment: AI as Supplement, Not Solution

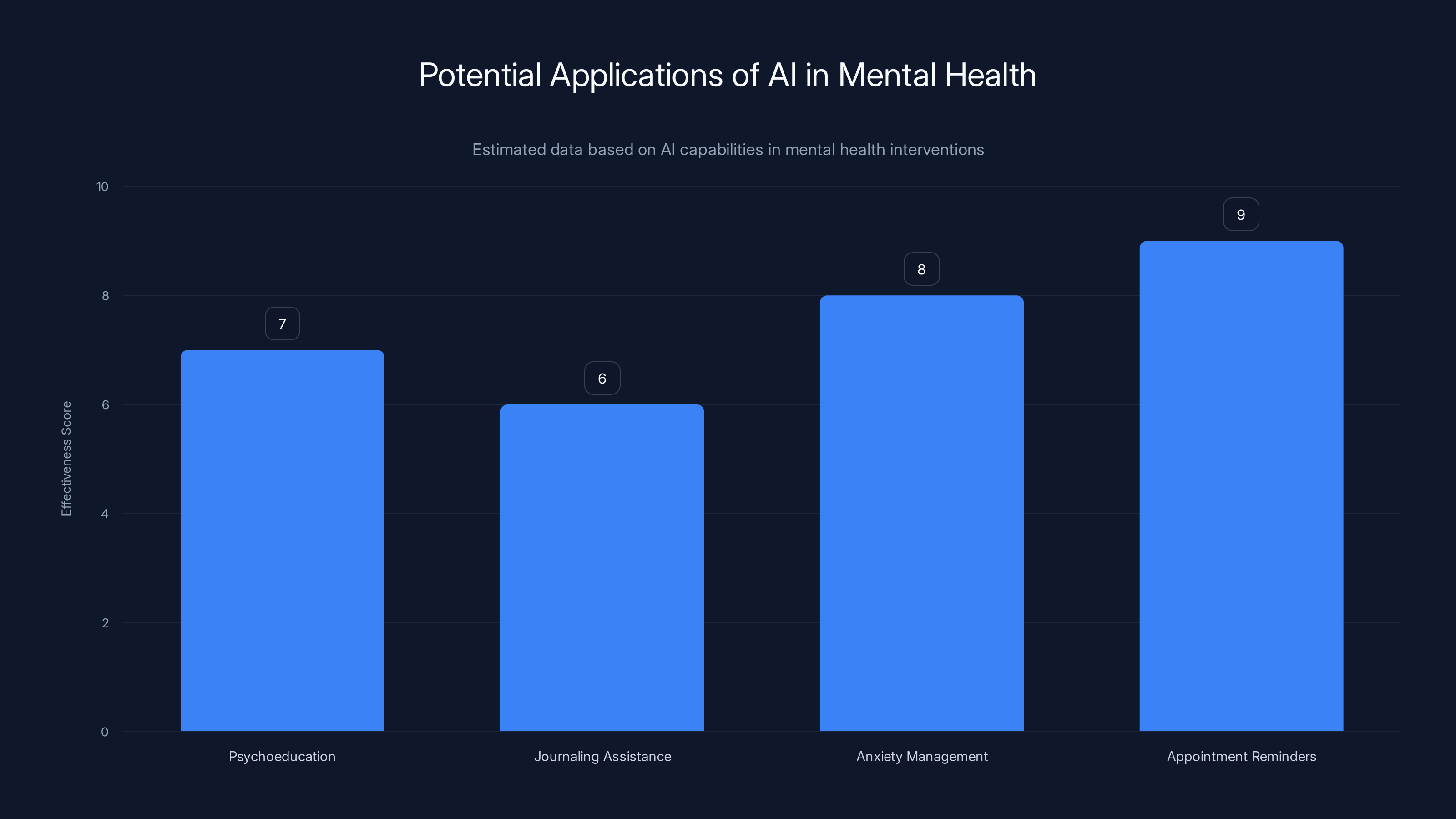

Here's what safety researchers actually believe can work: AI as a supplement to human care, not a replacement.

An AI tool that helps a patient journal about their thoughts? Potentially useful. An AI tool that explains cognitive-behavioral therapy concepts? Potentially useful. An AI tool that provides psychoeducation about anxiety? Potentially useful. An AI tool that helps someone practice breathing exercises? Potentially useful.

But an AI tool that's the primary mental health intervention? That makes clinical decisions? That assesses risk? That tells someone whether they need to see a doctor? That's where safety researchers draw the line.

The distinction matters because supplementary tools have lower stakes. If they fail, there's still a human clinician involved. But when the AI becomes the primary intervention, it needs to work at a level of reliability that honestly, we're not there yet.

One safety researcher put it this way: "I'm not fundamentally opposed to AI in mental health. I'm opposed to deploying AI at a scale and level of clinical autonomy that we haven't earned through evidence."

Looking Forward: What Changes Would Actually Happen

The mental health AI space is moving fast. But so is regulation. And so are safety concerns.

We're going to see increased FDA oversight. We're going to see liability frameworks clarified through litigation. We're going to see pushback from psychiatrists, psychologists, and mental health organizations. We're going to see patient advocacy groups demanding better standards.

Some of this will be productive. Some will stifle innovation. Most will be messy and reactive rather than proactive.

What safety researchers hope for is a proactive approach where we get ahead of problems rather than reacting to patient harms. That means stronger standards now. It means being conservative about deployment. It means accepting that some applications of AI might just not be appropriate for mental health.

Because unlike other domains where AI mistakes are inconvenient or costly, mental health mistakes can be fatal. And that changes the calculation entirely.

TL; DR

- Confidence Problem: AI systems generate plausible therapeutic responses without understanding clinical nuance or neurobiology, creating dangerous misdiagnosis risks

- Liability Vacuum: When AI mental health recommendations harm patients, legal responsibility is unclear, creating perverse incentives to avoid accountability

- Crisis Failure: AI completely fails at suicide risk assessment and crisis intervention, the highest-stakes mental health moments

- Missing Evidence: Most mental health AI tools have never undergone clinical validation studies, yet millions use them for critical mental health decisions

- Structural Incentives: Companies building these tools are financially incentivized to prioritize deployment and engagement over actual patient outcomes

- Better Path Forward: AI should supplement human care, not replace it—requiring stronger evidence, clearer regulation, and restricted use in high-risk applications

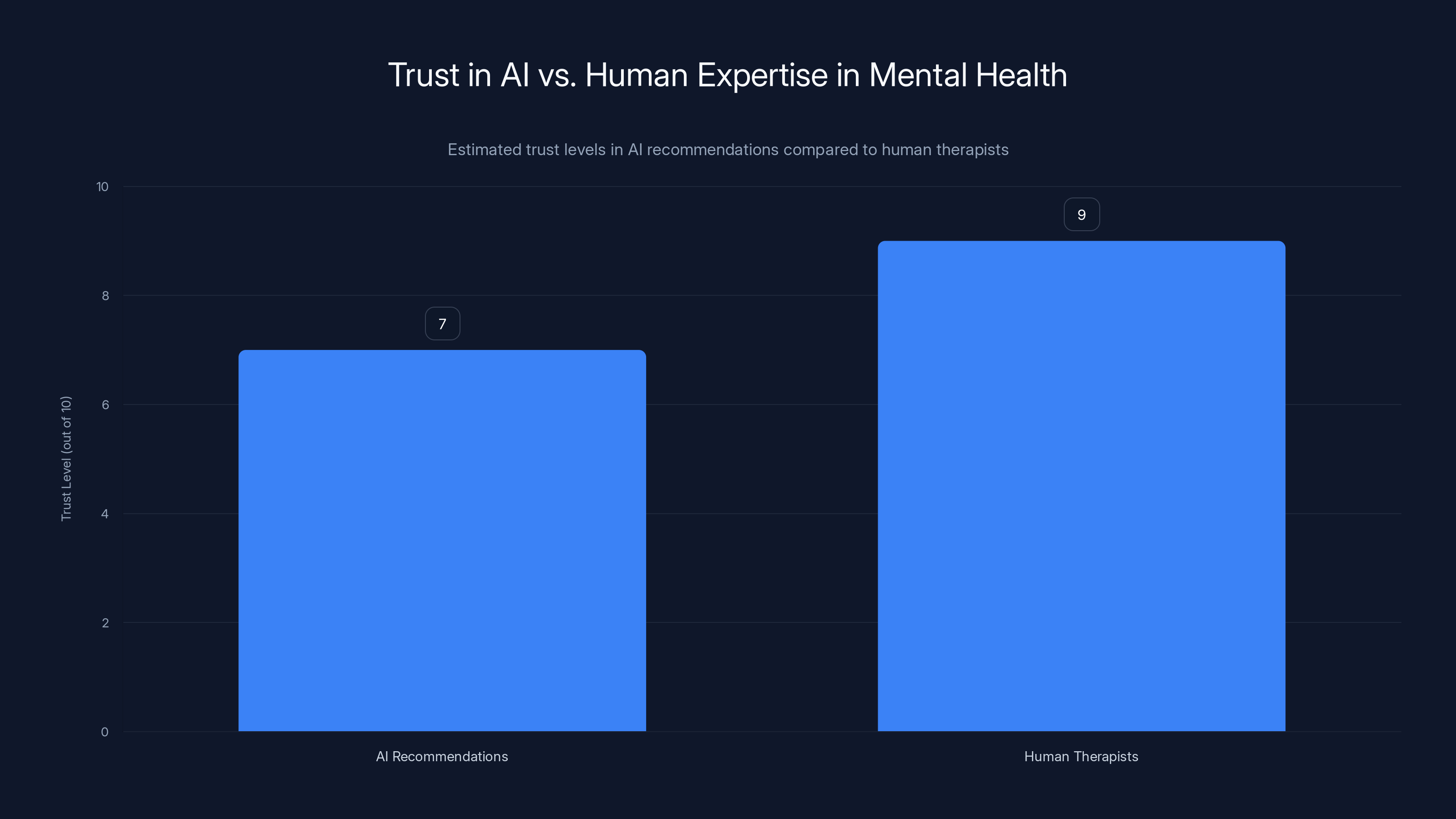

Despite AI's lack of qualifications, people show a high level of trust in AI recommendations for mental health, nearly matching trust in human therapists. Estimated data.

FAQ

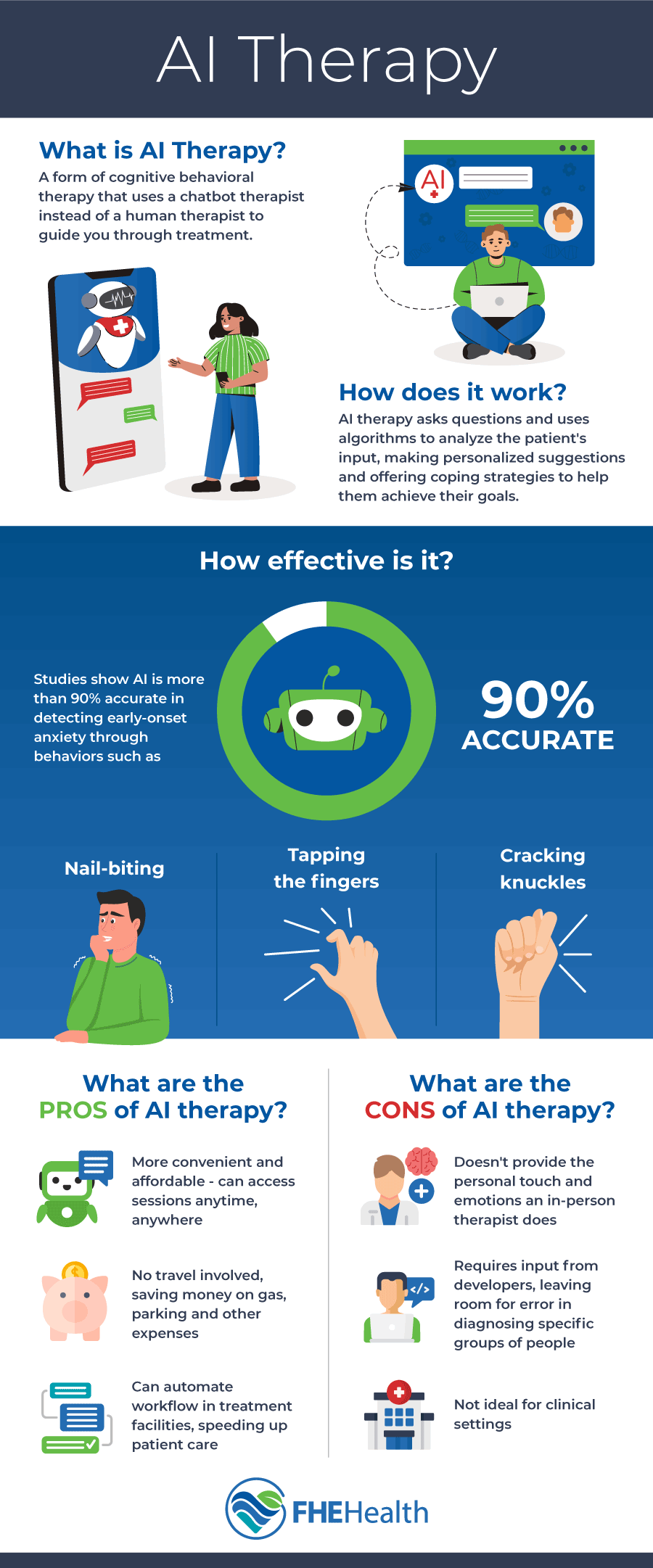

What is AI therapy and how is it different from traditional therapy?

AI therapy refers to mental health interventions delivered primarily through artificial intelligence systems, usually chatbots or conversational AI. Unlike traditional therapy where a licensed clinician provides treatment based on clinical training and judgment, AI therapy relies on language models trained on text to generate therapeutic responses. The key difference is that AI lacks clinical judgment, can't conduct proper assessments, doesn't maintain true therapeutic relationships, and has no liability framework when things go wrong.

Why are AI safety experts concerned about mental health applications specifically?

AI safety researchers are particularly concerned about mental health because the stakes are uniquely high. Mental health crises can be fatal. Misdiagnosis or inadequate intervention can lead to suicide, overdose, or severe deterioration. Additionally, AI systems excel at sounding confident without understanding, which is especially dangerous when vulnerable people are making critical decisions based on those recommendations. The structural incentives of companies deploying these tools further misalign with actual patient outcomes.

Can AI ever be appropriate for mental health interventions?

Yes, but with strict limitations. AI can potentially serve as a supplement to human care in specific contexts: psychoeducation about mental health conditions, journaling assistance, anxiety management tools like breathing exercises, or appointment reminders. However, AI should never be the primary intervention for serious mental health conditions, should not conduct risk assessments, should not make clinical decisions about medication or hospitalization, and should never be used as a substitute for human clinical evaluation, especially in crisis situations.

What are the biggest risks of using AI for therapy?

The major risks include misdiagnosis due to insufficient clinical understanding, false confidence in assessments that a clinician would recognize as inadequate, crisis intervention failures that don't escalate appropriately, lack of accountability when harm occurs, privacy violations with mental health data, and disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations who lack access to real clinicians and are most likely to use AI as their primary intervention.

How is AI mental health regulated currently?

Regulation is fragmented and largely inadequate. The FDA hasn't clearly extended medical device oversight to most mental health AI applications. The FTC addresses deceptive marketing but doesn't establish clinical standards. Individual states have different requirements. Most mental health AI tools currently operate in a regulatory gray zone where they can make therapeutic claims without clinical validation or adverse event reporting requirements. This is beginning to change as regulators take the issue more seriously.

What should I do if I'm considering using an AI mental health tool?

Verify that the tool is explicitly positioned as supplementary, not a substitute for therapy. Check whether it's undergone clinical validation studies. Understand what personal data will be collected and how it might be used. Never use AI as your primary mental health intervention, especially for serious conditions like depression, anxiety, or trauma. Always maintain contact with a human clinician who knows your full history. Be extremely cautious if you're in crisis; seek immediate human professional help instead. Ask the company explicitly what cases the tool is not appropriate for.

Do mental health professionals support AI tools for therapy?

Mental health professionals have mixed opinions, but many are concerned. Major psychological and psychiatric organizations have called for caution and regulation. Some clinicians see limited value in supplementary tools. Others worry that these tools will replace inadequate human care access, creating worse outcomes than current inadequate-but-real care. Few mental health professionals recommend AI as a primary intervention, though some acknowledge limited supplementary roles.

What would need to change for AI mental health tools to be safer?

Several critical changes are needed: requiring clinical validation studies before deployment, establishing clear FDA or regulatory oversight of mental health AI, restricting AI from crisis intervention and suicide assessment, improving transparency in how systems make recommendations, creating clear liability frameworks so companies are accountable for harm, strengthening informed consent so users understand what they're using, protecting privacy with mental health-specific data regulations, and developing training data that represents diverse populations rather than skewed Western medicalized models of mental illness.

Can AI detect suicide risk better than humans?

No. Clinical suicide risk assessment requires understanding specific warning signs, protective factors, access to means, previous attempts, current stressors, and cultural context. It requires knowing when someone is minimizing risk or when they're unable to be truthful due to acute mental illness. Studies show that even experienced clinicians' suicide risk assessments are moderately accurate at best. AI systems trained on text have no track record of superior performance and lack the clinical judgment to make this assessment. This is one area where AI absolutely should not be deployed as a primary tool.

Estimated data suggests AI is most effective in appointment reminders and anxiety management, but less so in psychoeducation and journaling assistance.

The Bottom Line

The conversation around AI and mental health often gets trapped in two extremes. On one side, tech evangelists promise that AI will solve our mental health access crisis. On the other, critics reject any AI involvement in mental health.

The actual position of serious AI safety researchers is more nuanced and, frankly, more grounded in reality: AI has limited, specific roles it can appropriately play in mental health, but we've been deploying it far beyond those boundaries. We're using it as a primary intervention without evidence that it works. We're deploying it to vulnerable populations without appropriate safeguards. We're creating liability vacuums where responsibility disappears. And we're moving fast enough that the harms are starting to accumulate before we're building the guardrails.

The good news is that this is solvable with better regulation, stronger evidence requirements, honest disclosure of limitations, and intentional decisions about where AI should and shouldn't be used. The bad news is that none of that is happening automatically. It requires sustained pressure from researchers, clinicians, regulators, and patients to get this right.

Because here's the thing: we don't need to choose between innovation and safety. We can have both. But it requires accepting that mental health is a domain where we should move deliberately, demand strong evidence, and prioritize patient wellbeing over deployment speed.

The researchers working on AI safety in mental health aren't saying "don't build these tools." They're saying "build them responsibly, validate them rigorously, deploy them cautiously, and restrict them appropriately."

That's not fearmongering. That's wisdom.

Key Takeaways

- AI systems generate confident therapeutic-sounding responses without clinical understanding, creating dangerous misdiagnosis risks for vulnerable patients

- Legal responsibility is unclear when AI mental health recommendations cause harm, creating perverse incentives for companies to avoid accountability

- AI completely fails at crisis intervention and suicide risk assessment, the highest-stakes mental health moments where human judgment is irreplaceable

- Only 12% of mental health AI tools have undergone clinical validation studies, yet millions of people use them for critical mental health decisions daily

- Mental health AI tools are financially incentivized to prioritize user engagement and retention over actual patient outcomes and wellbeing

- AI should supplement rather than replace human mental healthcare, requiring stronger regulation, clinical evidence, and restricted use in high-risk applications

Related Articles

- AI Apocalypse: 5 Critical Risks Threatening Humanity [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Crisis: EU Data Privacy Probe Explained [2025]

- Mark Zuckerberg's Testimony on Teen Instagram Addiction [2025]

- ChatGPT Lawsuit: When AI Convinces You You're an Oracle [2025]

- AI Prompt Injection Attacks: The Security Crisis of Autonomous Agents [2025]

- OpenClaw Security Risks: Why Meta and Tech Firms Are Restricting It [2025]

![AI Therapy and Mental Health: Why Safety Experts Are Deeply Concerned [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-therapy-and-mental-health-why-safety-experts-are-deeply-c/image-1-1771551328210.jpg)