Nvidia's Campaign to Sell AI Chips to China: The Policy Reversal That Changes Everything

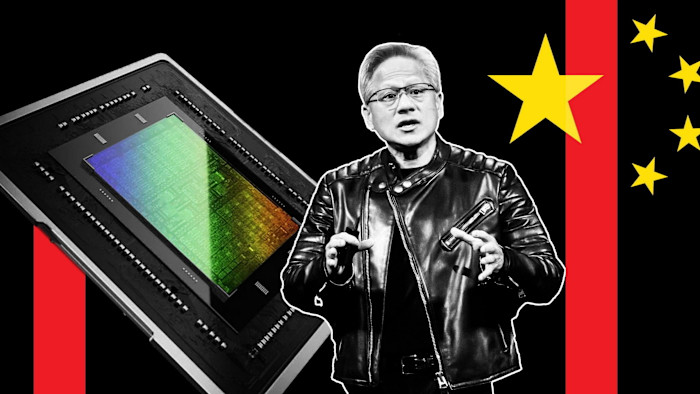

Jensen Huang, Nvidia's CEO, was having the time of his life in China. Casual bike rides through Shanghai, browsing fruit stands, enjoying hot pot in Shenzhen—the images flooding social media made it look like a victory lap. And frankly, it was.

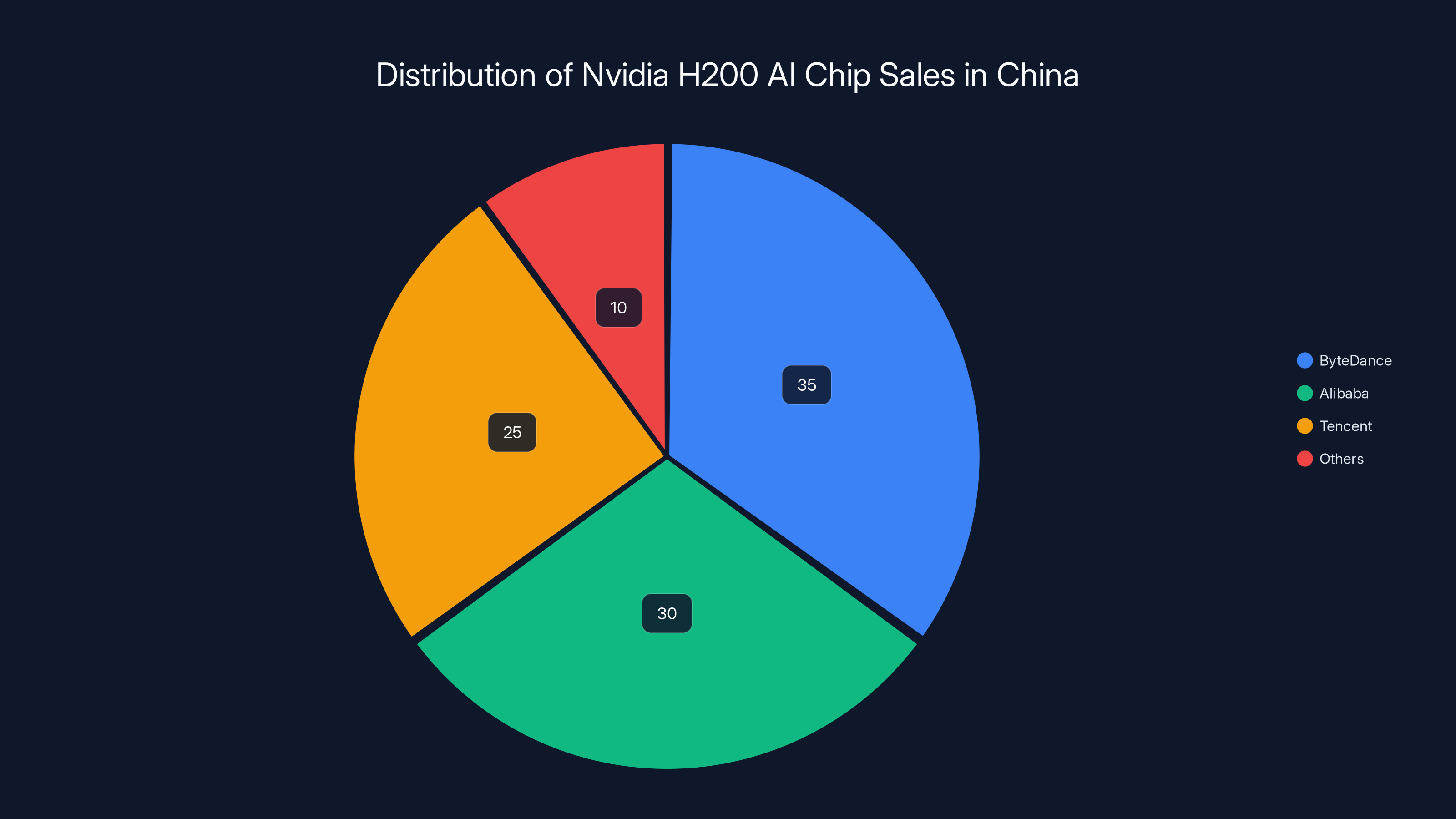

Behind the carefully curated moments of leisure was something far more significant: Beijing had reportedly approved the sale of more than 400,000 Nvidia H200 AI chips to major Chinese tech companies, including Byte Dance, Alibaba, and Tencent. This isn't just a business deal. It's a fundamental reversal of US technology policy that's been in the making for over a year, and it signals something crucial about how the global AI race is actually going to unfold.

For months, the Biden administration had imposed strict export controls on advanced AI semiconductors, blocking chips like the H200 from reaching Chinese customers. The rationale was straightforward: prevent Beijing from developing powerful AI systems that could have military applications. It was hardline, it was principled, and it was ineffective. Now, under a different political logic championed by Huang and Trump administration officials like David Sacks, the US has decided that keeping China dependent on American technology is better than losing the market entirely. Whether that strategy actually works is the question that's going to define the next decade of geopolitics.

What's happening right now is more than just Nvidia making money off Chinese customers (though that's certainly part of it). It's a window into how tech policy actually gets made at the highest levels, how much leverage a single CEO can have, and how quickly American strategic priorities can flip based on economic arguments. But it also reveals something uncomfortable: the assumption that you can keep a superpower "hooked" on your technology while simultaneously trying to contain it might be one of the most dangerous miscalculations Silicon Valley has ever made.

TL; DR

- Beijing approved 400,000+ H200 chips to Chinese AI companies under conditional licenses, representing a dramatic policy reversal from strict Biden-era export controls

- Trump administration logic: Allowing regulated sales keeps Chinese companies dependent on US tech while preventing them from buying from competitors or smuggled sources

- China's dual strategy: Companies get compute access they desperately need while Beijing maintains tight control, supporting domestic semiconductor competition

- Whiplash problem: Years of mixed signals about export controls give China incentive to both access US chips AND develop domestic alternatives simultaneously

- National security gamble: The assumption that regulated dependency can coexist with containment may be fundamentally flawed

Estimated data suggests ByteDance, Alibaba, and Tencent are major recipients of Nvidia H200 AI chips, reflecting their need for computational power.

The Export Control Regime That Almost Worked

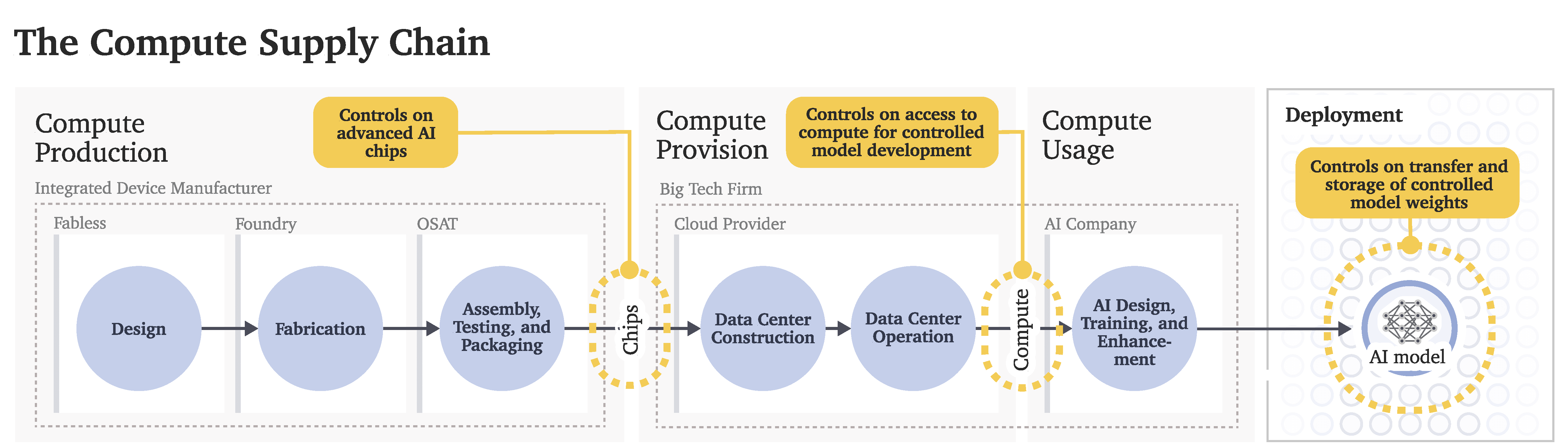

When the Biden administration tightened semiconductor export controls in late 2023, it was one of the most significant tech policy moves in recent memory. The strategy was technically sound: identify the bottleneck technology (advanced AI chips), restrict supply to potential adversaries, and hope that technological leadership would translate into geopolitical advantage.

The targets were specific. Nvidia's H100 and H200 chips are among the most powerful AI accelerators on the planet. Training large language models requires massive amounts of computational horsepower, and these chips provide it at scale. The logic was ironclad: if you control the chips, you control the pace of AI development. China couldn't build frontier AI models if it didn't have access to frontier hardware.

For approximately 18 months, this strategy appeared to be working. Chinese AI companies found themselves boxed in. Alibaba, Tencent, and Byte Dance all needed GPUs to train their competing large language models, but American export controls made acquiring H100s and H200s legally impossible for most use cases. They improvised. Some companies bought older Nvidia chips that weren't restricted. Others developed workarounds using less powerful accelerators. Some probably engaged in smuggling, though the extent was debated.

But here's where the strategy started cracking: the restrictions were never truly comprehensive enough to stop all semiconductor access, and enforcement became increasingly difficult. Gray market sales flourished. Used chips ended up in China through intermediaries. Smaller companies found loopholes in the licensing requirements. Every month of enforcement revealed new gaps.

Meanwhile, the restrictions carried a cost for American companies that wasn't being paid by American taxpayers. Nvidia lost an enormous market. The company had been deriving a meaningful percentage of its revenue from China, and that spigot shut off overnight. Other American chip companies faced similar constraints. The economic hit was real, and the lobbyists were vocal.

This is where Huang's campaign began in earnest. His argument was economically intuitive: if you're going to lose the market anyway—through smuggling, through customers switching to domestic alternatives, through competitors filling the gap—then why not maintain regulatory visibility by allowing controlled sales? At least you'd know where the chips were going. At least you'd maintain influence over Chinese tech development. At least you'd make money while doing it.

It's a seductive argument. It sounds rational. But it rests on a critical assumption that might not hold up to scrutiny: that you can simultaneously provide access to cutting-edge technology and maintain the technological gap that made you powerful in the first place.

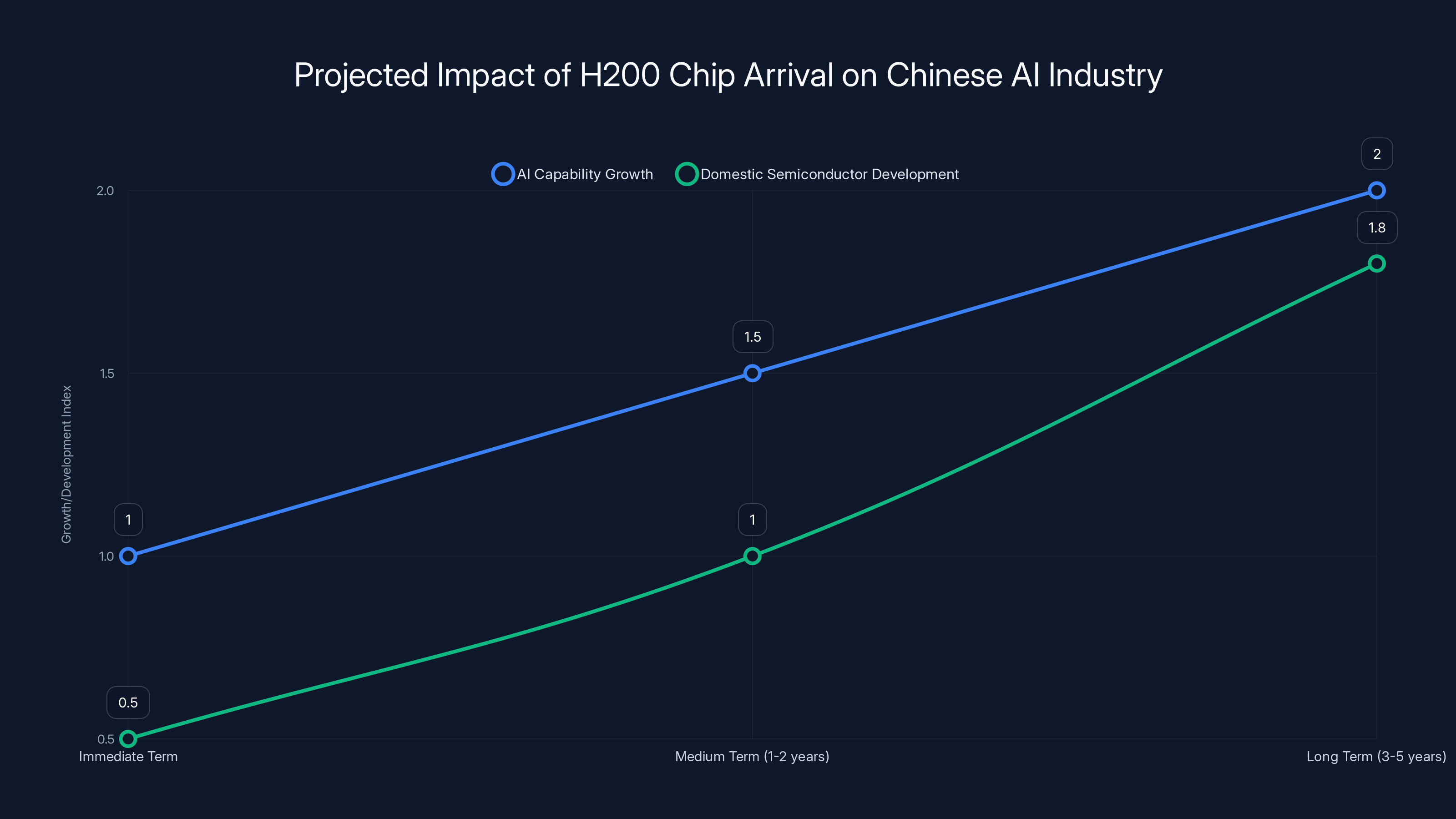

The arrival of H200 chips is expected to significantly boost China's AI capabilities and semiconductor development, with AI capabilities potentially doubling in 3-5 years. (Estimated data)

Inside the Lobbying Campaign

Jensen Huang didn't just show up in China one day and leave with approvals. The campaign to shift American export policy has been running for a year, and it involved multiple constituencies, strategic messaging, and a careful exploitation of the Trump administration's different priorities.

Huang's core argument evolved over time. Initially, it was purely economic: China represents a massive market, and American companies shouldn't cede it entirely to competitors. If US policy prevents American companies from selling H200s to Chinese customers, those customers will eventually buy from someone else. They'll pressure Huawei to develop alternatives. They'll support Chinese semiconductor startups. They'll source from secondary markets. In other words, the restriction accomplishes the opposite of its intended purpose.

Then came the dependency argument. Huang and his allies pointed out that allowing limited, regulated access to American chips would actually keep China dependent on US technology in a way that stricter restrictions couldn't. If Chinese companies get some H200s through official channels, why would they invest heavily in developing domestic alternatives? If they can access American technology legally, they're less incentivized to build their own. It's the inverse of what national security experts actually argue, but the logic is seductive.

The third argument emerged from internal White House discussions and is perhaps the most cynical: smuggling is happening anyway, and you have no control over where those chips ultimately end up. Better to allow some regulated sales where you have visibility than to ban all sales and watch them disappear into gray markets. This is the argument of someone who's accepted defeat on the core objective (preventing China from accessing advanced chips) and is settling for visibility instead. It's a harm-reduction argument, and it's harder to counter directly because it acknowledges the failure of the previous policy.

What made this campaign effective was timing. The Trump administration came into office with different priorities. Sacks, the White House AI czar, has been vocal about wanting to maintain US dominance in AI, and he appears to have concluded that blocking China from chips is counterproductive to that goal. If Nvidia can keep selling to Chinese customers, Nvidia profits, and Nvidia has the resources and incentive to maintain technological leadership.

It's not difficult to see how Huang made this case directly to Trump: "If we lose this market, China wins. If we keep selling, we maintain profit, we maintain dominance, and we keep Chinese companies dependent on us." The logic is almost irresistible to a businessman, which Trump certainly is.

The advocacy wasn't conducted with explicit pressure tactics, at least not publicly. Instead, it was done through the normal channels of elite persuasion: meetings with White House officials, conversations with policy advisors, public statements about the economic damage of restrictions. By all accounts, Huang was personally involved in many of these discussions, using his platform as one of the most visible tech CEOs in the world.

What's notable is how quickly the policy shifted once the new administration took office. There were no dramatic Congressional debates, no long policy review processes, no public controversy. Instead, within weeks of Trump's return to power, the signals from the White House changed. Officials began suggesting that some export controls should be relaxed. Suddenly, the H200 approval for Chinese companies moved from impossible to imminent.

Why China Actually Wants This (And Doesn't Want It)

This is where the story gets genuinely interesting, because Beijing's position is far more complex than "we want American chips." Chinese policymakers are engaged in a sophisticated balancing act, trying to accomplish two objectives that pull in opposite directions.

On one hand, Chinese AI companies desperately need compute power. They're trying to develop large language models that can compete with Open AI's GPT-4, with Google's Gemini, with Anthropic's Claude. These models require training on massive datasets using powerful hardware. Without access to the world's best accelerators, Chinese AI companies fall further behind. Every month they can't access H200s is a month their competitors gain ground.

Byte Dance's AI division has been burning through capital trying to develop competitive models without access to American chips. Alibaba's AI initiatives are similarly constrained. Tencent, which has deep pockets and significant AI expertise, is probably in the best position to develop workarounds. But all of them would prefer to just buy the best hardware on the market, which happens to be made by Nvidia.

Approving the H200 sales solves this problem directly. With access to hundreds of thousands of chips, Chinese companies can finally train models at scale. They can hire top talent and actually give them the tools to be competitive. They can stop wasting energy on engineering workarounds and start focusing on actual AI development.

But here's the complication: Beijing also has a strategic interest in developing China's domestic semiconductor industry. Huawei has been working on AI accelerators. Domestic startups have been pouring resources into competing designs. For years, the narrative from Chinese policymakers has been that the country needs to reduce its dependence on American technology. This is both an economic goal and a strategic one.

If Beijing simply opens the floodgates and allows unlimited H200 sales, it undermines years of investment in the domestic semiconductor ecosystem. Why would companies spend billions developing Huawei chips if they can just buy the better American version? The market would choose American technology, and the domestic industry would atrophy.

So Beijing's actual strategy appears to be calibrated: allow access to H200s, but keep it tightly controlled. Grant licenses to specific companies. Limit the quantities. Make the government the gatekeeper of American chip access. This accomplishes both goals simultaneously. Companies like Alibaba and Tencent get the compute they need, so they're not making desperate investments in domestic alternatives. But because access is limited and controlled, demand for Huawei chips remains strong. The incentive structure supports continued development of the domestic semiconductor industry.

It's a sophisticated approach, and it reveals something important about how Beijing thinks about technological competition. It's not pursuing complete independence from American technology (that's probably impossible anyway). Instead, it's trying to maintain leverage over American companies while building alternatives that can't be cut off by future policy changes. If Nvidia stops selling H200s tomorrow, China has domestic chips ready to go. If Nvidia keeps selling indefinitely, Chinese companies are competitive. It's optionality through diversification.

For Nvidia and the Trump administration, this arrangement looks like a win: China remains somewhat dependent on American hardware, and Nvidia keeps a massive revenue stream. For Beijing, it looks like calculated progress: Chinese companies get what they need, and the domestic semiconductor industry stays viable. Everyone walks away thinking they won.

The problem is that this logic might not survive contact with reality.

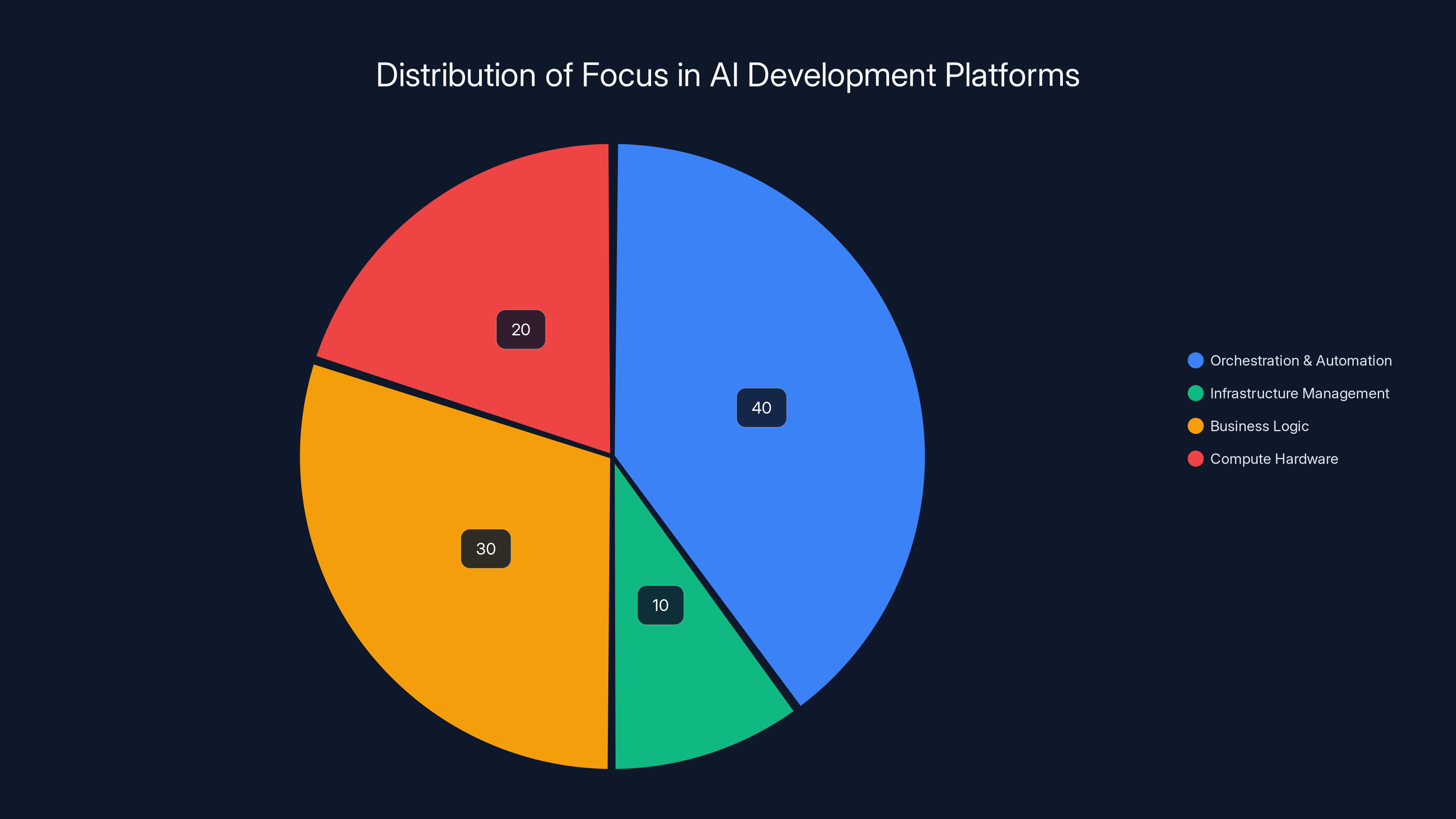

Estimated data shows that platforms like Runable focus heavily on orchestration and automation (40%) and business logic (30%), reducing the need for direct infrastructure management (10%) and compute hardware concerns (20%).

The National Security Paradox

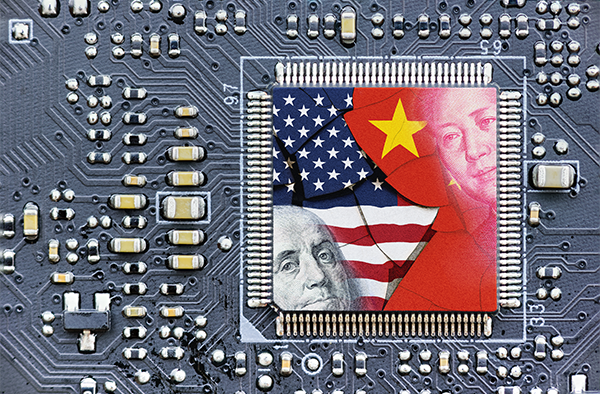

Here's the tension at the heart of this policy shift: the argument for allowing H200 sales to China rests on the assumption that you can simultaneously provide access to cutting-edge technology and maintain a technological gap. History suggests this doesn't work.

Consider the logic carefully. The Trump administration argues that allowing China regulated access to H200s will keep Chinese companies dependent on American technology, preventing them from investing in domestic alternatives. But China's response has been to take the regulated access AND invest heavily in domestic alternatives. These aren't mutually exclusive strategies. Beijing can have both.

In fact, the ideal scenario for Chinese policymakers is exactly what's happening: get access to the world's best chips from America while simultaneously building the infrastructure to reduce dependence on them. The more pressure America applies through restrictions, the more China invests in domestic alternatives. The more America relaxes restrictions to keep companies dependent, the more resources become available for companies to fund domestic programs. You can't solve both problems with a single approach.

The historical precedent is semiconductor manufacturing itself. In the 1970s and 1980s, American companies were the dominant chip manufacturers globally. Then Congress started imposing restrictions on certain technologies going to certain countries. The response wasn't for those countries to accept permanent dependence on American companies. The response was for them to build their own semiconductor industries. Today, Taiwan, South Korea, and China all have substantial semiconductor sectors, and American dominance is qualified at best.

The assumption that you can create permanent technological dependence through regulated access to your products has never really worked. At some point, the target country either develops alternatives or finds ways around the restrictions. The time window during which restrictions create leverage is shorter than policymakers typically assume.

There's also a more immediate problem: every month that Chinese companies have access to H200s is a month their engineers spend learning how these chips work. It's a month of accumulated knowledge about American hardware architecture, about optimization techniques, about what's possible at scale. Over time, this knowledge transfers into domestic chip development. An engineer who's spent two years optimizing code for H200s can apply that expertise to developing Huawei accelerators. The chips themselves become a template for competitive products.

This is the actual risk the Biden administration was trying to mitigate. It's not primarily about preventing China from training large language models in the near term (they'll do that anyway, through smuggling or workarounds or less powerful hardware). It's about preventing the long-term transfer of knowledge and capability that allows China to develop world-class semiconductor alternatives.

By allowing H200 sales under the assumption of creating dependence, the Trump administration might actually be accelerating the very outcome it's trying to prevent. China gets the chips they need, their companies develop expertise with American technology, and their engineers apply that expertise to building competitors. Within five years, Huawei might have chips that are 80% as good as H200s, at a lower price point, without any dependence on American supply chains.

The Trump administration's counter-argument is that this is going to happen anyway because of smuggling. And there's truth to that. The question is whether allowing regulated sales accelerates the timeline or not. It almost certainly does.

What's genuinely lost in this policy shift is the temporary window where America had leverage through restriction. That window is probably closing now, and it won't open again.

The Economic Case for Unlimited Sales

From Nvidia's perspective, the economics of this situation are overwhelmingly clear. China represents one of the largest technology markets in the world. Excluding Nvidia from that market means billions in lost revenue. More importantly, it means Nvidia's competitors might step in. If Nvidia isn't selling to China, other companies will be, and market share is what matters for maintaining long-term dominance.

The H200 isn't just a commodity. It's the flagship product that generates enormous margins. Every unit sold to Alibaba or Tencent is a unit that's not sold to someone else, and it's revenue that supports Nvidia's ability to invest in the next generation of chips. The opportunity cost of being excluded from the Chinese market is existentially significant for Nvidia's business.

Beyond just the immediate revenue, there's a strategic argument for why Nvidia benefits from selling to China. If Chinese AI companies are using Nvidia hardware, they're building their entire software stack around Nvidia's ecosystem. They're writing code optimized for Nvidia's architecture. They're training models that run best on Nvidia GPUs. This creates lock-in. Even if a competitor developed chips that were technically superior, switching would require rewriting massive amounts of code and retraining models. Software inertia is more powerful than hardware superiority.

This is actually where Huang's argument gets most compelling. By selling H200s to China, Nvidia isn't primarily creating dependence on the hardware itself. It's creating dependence on the software ecosystem. Chinese companies and engineers become deeply invested in Nvidia's toolkit. They learn the APIs, the optimization techniques, the workflow. They build teams around Nvidia's platform. That knowledge is sticky.

For Nvidia shareholders, this is incredibly valuable. The company gets to access a massive market while simultaneously locking in long-term customer dependence. It's win-win from a pure business perspective.

The question is whether it's win-win from a national security perspective, and the answer is almost certainly no. What's good for Nvidia's bottom line isn't necessarily good for American strategic interests. In fact, the two are likely in direct conflict in this case.

The Biden administration understood this tradeoff and decided that national security concerns outweighed the economic interests of one company, even if that company was the most important semiconductor vendor in the world. The Trump administration has explicitly prioritized the economic interests, betting that the national security risks are overblown or manageable.

It's a values choice, and it's worth examining directly. Is it more important that Nvidia grows its revenue and market share, or that the United States maintains a technological advantage in AI? The Biden answer was the latter. The Trump answer is that you can have both, which is probably wishful thinking.

As U.S. technology restrictions increased, countries like China, Taiwan, and South Korea significantly ramped up investments in domestic semiconductor alternatives. Estimated data based on historical trends.

The Smuggling Problem That Justifies Everything

One argument that keeps reappearing in justifications for the H200 sales is worth examining closely: smuggling is happening anyway, so you might as well allow regulated sales.

The evidence that advanced chips are reaching China through gray markets is not disputed. The Wall Street Journal and other outlets have reported extensively on the underground networks through which American semiconductors end up in the hands of Chinese buyers despite export restrictions. Middlemen buy chips domestically, then resell them internationally. Companies in third countries act as fronts for Chinese purchases. Used chips get refurbished and shipped abroad.

The scale of this smuggling is debated. Some security experts say it's a small percentage of total Chinese chip usage. Others argue it's substantial and growing. But everyone agrees it's happening and that enforcement is difficult.

The White House argument is that if smuggling is going to happen regardless, you might as well allow some regulated sales where you have visibility over the supply chain. At least you know how many chips are being sold, where they're going, and who's buying them. With smuggling, you have no visibility. The chips disappear into black markets and you have no idea what happens next.

It's a harm-reduction argument, and it has intuitive appeal. But it only works if you believe that the total volume of chips reaching China would remain constant regardless of the official policy. If allowing regulated sales actually increases the total volume of chips reaching China (by making it easier for companies to acquire them, by reducing the price through legal channels, by normalizing access), then you're not just making the smuggling problem visible. You're making it worse.

This is where the argument gets circularity. White House officials are using the failure of previous export controls (the smuggling that's still occurring) to justify adopting a policy that would almost certainly increase the total volume of chips reaching China. They're saying, "Well, the export controls didn't work, so let's just allow sales." But the reason the export controls didn't work completely is because smuggling is profitable, which means allowing legal sales would make smuggling even more profitable and easier.

The most honest version of the Trump administration's argument would be: "We've decided that containing China's AI capability is impossible, so we might as well profit from it while we can." That would be a coherent position. The version they're actually articulating (that regulated sales will keep China dependent on American technology while preventing smuggling) is less coherent.

It's not clear that this is wrong from a pure pragmatism perspective. If you genuinely believe that the containment effort is doomed to fail, then capturing market share while you can makes some economic sense. But let's not pretend that this is a strategic victory. It's a capitulation dressed up in strategic language.

Beijing's Long Game: Dual Dependency

China's response to this situation reveals something important about how authoritarian regimes think about technological strategy. Beijing isn't interested in permanent independence from American technology (that's probably impossible and probably not necessary). Instead, Beijing is interested in optionality.

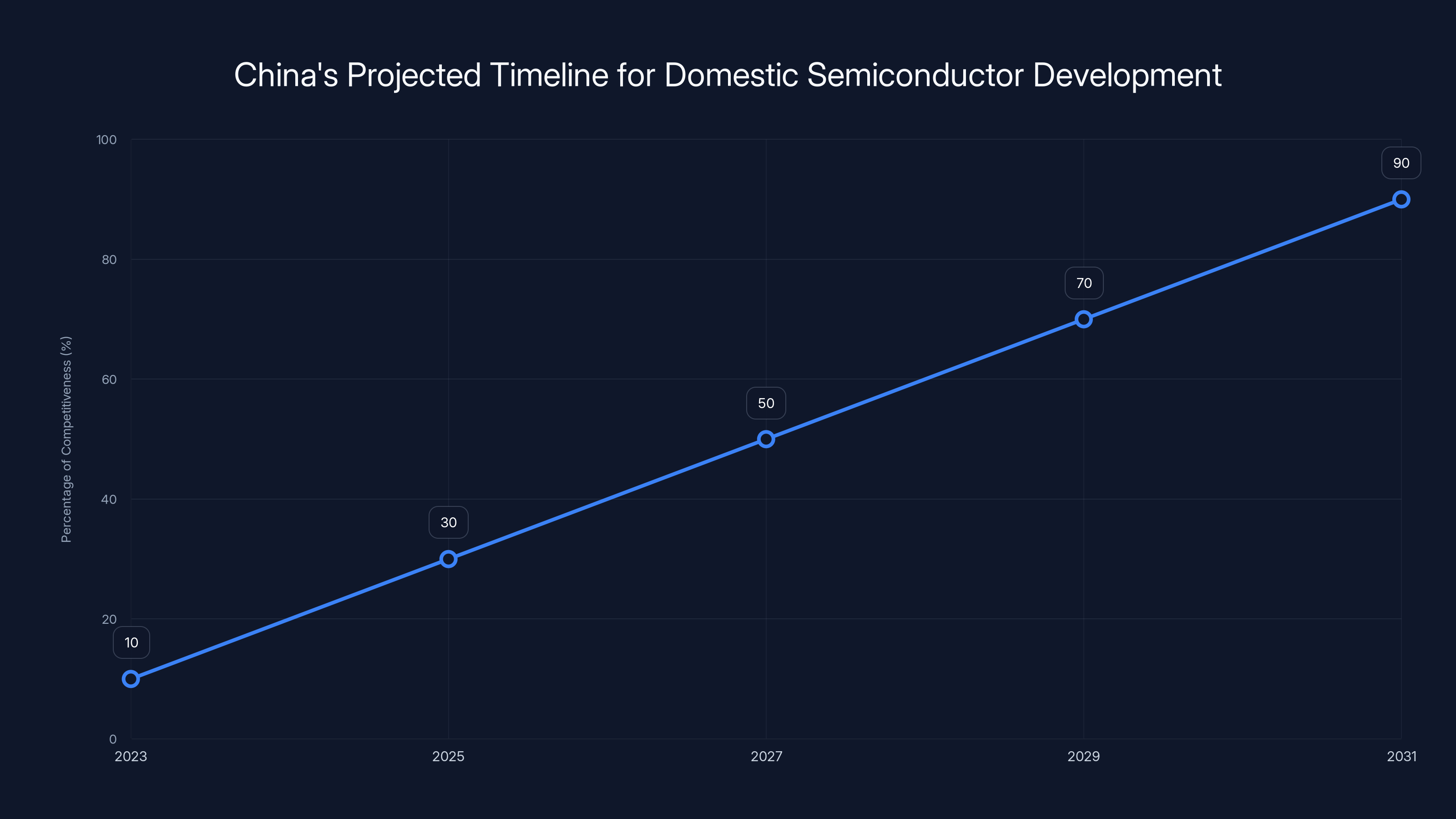

The strategy appears to be: maintain access to the best American technology where possible, while simultaneously developing viable alternatives. This creates a situation where China is never more than 12-18 months away from having a functional alternative if America cuts off supply again.

The benefits of this approach are substantial. Chinese companies get access to world-class technology immediately, which accelerates their AI development in the near term. But the government also maintains the incentive structure that supports domestic semiconductor development. Engineers at Huawei aren't competing against American companies that have unlimited market access. Instead, they're developing chips that will fill the gap if American supply is restricted.

This is actually more sophisticated than the American strategy of trying to maintain dependence through controlled access. Beijing is betting on progress and optionality. They expect that within 5-10 years, China will have domestic chips that are competitive with American offerings. They're not trying to prevent this or slow it down. They're accelerating it while buying time with access to American hardware.

From a strategic perspective, this is the more defensible position. You're not pretending that restrictions will work forever. You're not assuming that you can keep a superpower hooked on your technology. You're acknowledging that the competitive landscape will change, and you're preparing for it.

The irony is that by agreeing to sell H200s to China (assuming the reported approvals are accurate), Nvidia and the Trump administration are actually playing into Beijing's strategy perfectly. They're providing the capital and knowledge transfer that accelerates China's domestic semiconductor development. They're shortening the timeline on which China will have viable alternatives.

Estimated data suggests that China aims to achieve 90% competitiveness with American chips by 2031, leveraging both American technology and domestic development.

The Whiplash Problem and Credibility Collapse

Perhaps the most important long-term cost of this policy reversal isn't the immediate economic or strategic impact. It's the collapse of credibility in American technology policy more broadly.

For nearly two years, the Biden administration sent a consistent signal: America is imposing export controls on advanced chips to protect national security. The policy was controversial, it was economically costly, but it was clear. Companies knew where they stood.

Then a new administration came into power and reversed the policy. Now the signal is: America will allow regulated sales to China if it's economically beneficial to do so.

What does this tell Chinese policymakers about the durability of American policy? It tells them that American technology export restrictions are contingent on politics, not strategy. If the political winds change, the policy changes. If an American CEO has enough influence, the policy changes. If the economic interest is strong enough, the policy changes.

From Beijing's perspective, this is genuinely valuable information. It means that any American export restriction can be worked around, not by violating the rule, but by waiting for the political conditions to shift. It means that lobbying American officials and business leaders to put economic pressure on policymakers is a viable strategy for reversing restrictions.

Samuel Bresnick, a researcher focused on AI and security at Georgetown University, has made this point explicitly: the whiplash between policies gives China the exact wrong incentives. It tells them that they should simultaneously pursue two strategies: develop domestic alternatives (because restrictions might come back), and maintain access to American technology (because restrictions can be lifted if you wait long enough). This is the worst possible signal to send if you want China to choose one path or the other.

The credibility cost extends beyond just China. Allied countries are watching too. If you restrict technology exports based on national security concerns, but then lift those restrictions for economic reasons when the winds shift, what does that say about how serious you are about the national security rationale? It suggests you were never really serious about it, and that you were using national security language to mask economic interests.

This is corrosive to the entire export control system. Once countries learn that restrictions are impermanent and can be reversed by lobbying, the restrictions lose their force. Countries won't invest as heavily in developing alternatives because they know that access to American technology will eventually be available. They'll wait it out.

It's not clear that this is worse than maintaining ineffective restrictions that drive smuggling and underground markets. But it's certainly different, and the long-term consequences of a credibility collapse in American export policy aren't fully understood yet.

What This Means for American AI Competitiveness

There's a specific narrative that supporters of the H200 sales are promoting, and it's worth examining directly: allowing China to buy American chips will actually help American AI companies stay competitive in the long run because it keeps Nvidia profitable and able to invest in the next generation of technology.

The logic is straightforward. Nvidia's profits fund Nvidia's R&D. If Nvidia is excluded from the Chinese market, its profits decline, its R&D spending declines, and its ability to stay ahead of competitors (including Huawei, including other Chinese startups, including TSMC and Samsung) diminishes. Conversely, if Nvidia can access the Chinese market, it has more resources to invest in maintaining technological leadership.

This is probably true in a narrow sense. Nvidia's profits would be higher if it could sell to China, and those profits could theoretically fund better R&D. The question is whether the benefit to American AI competitiveness from Nvidia's higher profits is greater than the cost of giving China access to cutting-edge chip technology.

It's genuinely not obvious which effect dominates. On one hand, Nvidia's stronger financial position would support American AI leadership. On the other hand, China's access to H200 chips accelerates Chinese AI development. You could have a scenario where Nvidia profits are higher but American AI companies are overall less competitive because China has closed the gap.

What seems clear is that this is a bet on Nvidia's continued technological dominance. The assumption is that even with access to American chips, China won't be able to develop competitive alternatives quickly enough to matter. That Nvidia will always be a few years ahead. That the technological gap will persist even as the commercial gap narrows.

This assumption seems increasingly shaky. China has massive resources dedicated to semiconductor development. Chinese engineers are among the world's best. The talent is there. The capital is there. The only constraint has been access to advanced manufacturing technology (which TSMC controls) and knowledge about what's possible at scale (which access to H200s provides).

Removing that constraint seems more likely to accelerate Chinese catch-up than to maintain American dominance.

Still, from a pure corporate perspective, Nvidia's interests are clear. The company benefits from selling more chips, and if the political constraint is lifted, the company will certainly sell. Whether this is good for broader American interests is a different question, and it's one that's being answered without serious public debate.

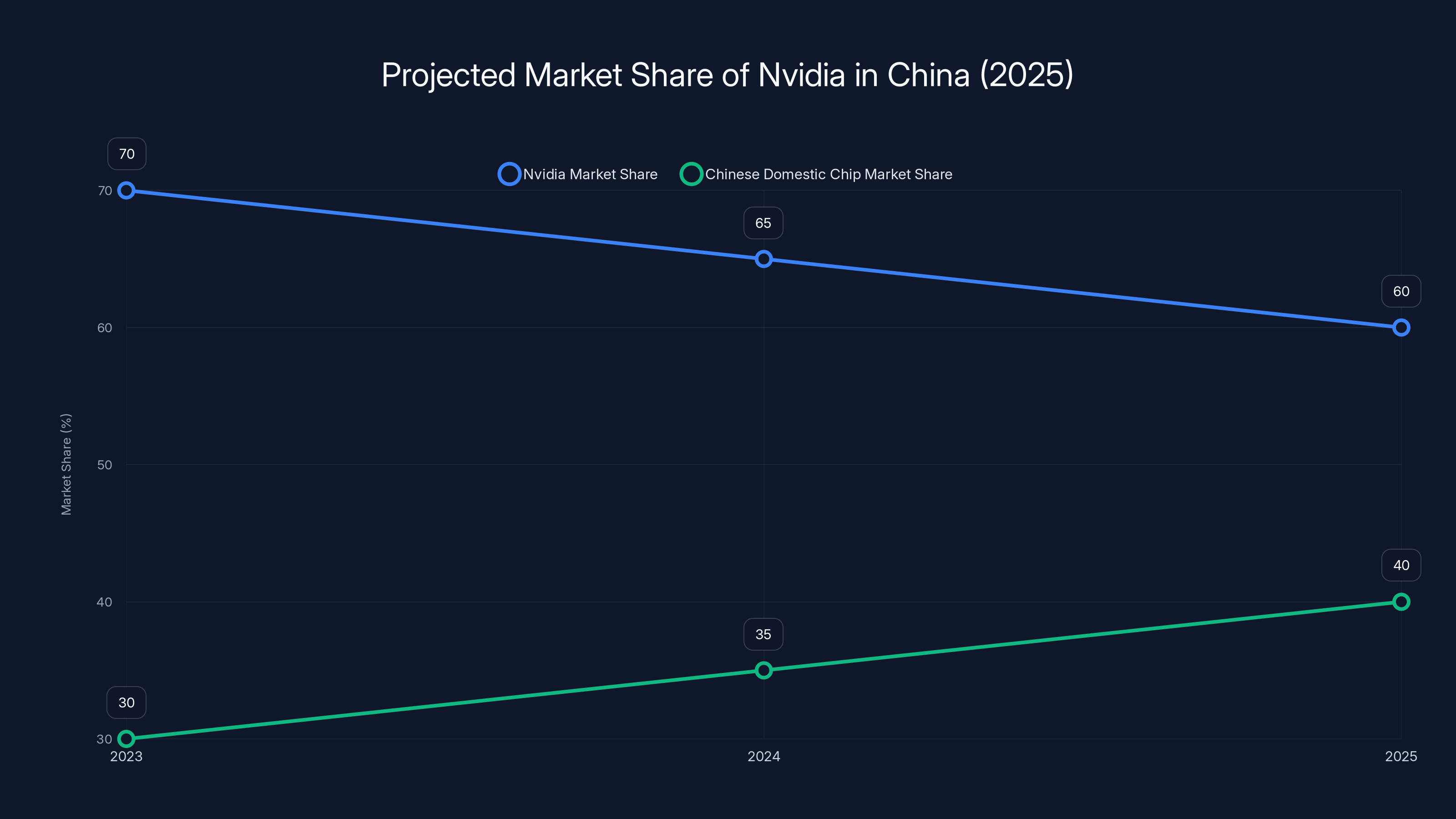

Estimated data suggests Nvidia's market share in China may decline by 2025, while Chinese domestic chip market share could increase, reflecting potential shifts in the semiconductor landscape.

The Gray Market as a Policy Failure Signal

The fact that gray market sales of American semiconductors to China are ongoing despite export controls is worth examining as a policy failure, because it reveals something important about how difficult it actually is to control technology flows.

Export controls work through a combination of legal restrictions, enforcement mechanisms, and private sector compliance. Companies know they can't legally export restricted items, so they don't. Enforcement agencies catch violators and punish them. The system maintains itself through a combination of law and incentive structure.

The problem is that when the product is valuable enough, the incentive to circumvent the restrictions becomes overwhelming. If you can buy an H200 chip domestically for

The fact that this is happening suggests that the export controls are fundamentally undersized relative to the value of the product and the motivation of the parties involved. Which means that you have two choices: make the controls even more strict and comprehensive (which is politically difficult and economically costly), or allow some regulated sales to capture the market that would otherwise be served by gray markets.

The Trump administration has chosen the second approach. But this reveals something uncomfortable about export controls as a policy tool: they work best against countries or actors that you have some cooperative relationship with. Against determined adversaries with resources and networks, they're permeable.

This doesn't mean export controls should be abandoned. It means they need to be realistic about what they can actually accomplish and should be paired with other strategic approaches (like building relationships with allied semiconductor manufacturers, like investing in alternative technologies, like developing economic incentives for compliance).

What's notable is that the shift from the Biden approach (strict controls) to the Trump approach (regulated sales) doesn't actually solve the gray market problem. It just shifts the problem around. Instead of gray market sales existing because export controls are too restrictive, gray market sales might accelerate because legal sales make it more profitable for middlemen to route chips through intermediary countries and back to China at a markup.

The TSMC Question: Taiwan's Leverage

One crucial element of this whole situation that hasn't received enough attention is Taiwan's role. TSMC is the world's leading semiconductor manufacturer, and it manufactures chips for Nvidia. Taiwan is also a U. S. ally with complex relationships with both Washington and Beijing.

When the U. S. imposed export controls on advanced chips to China, TSMC faced a difficult choice. The company is headquartered in Taiwan, a democratic ally of the U. S., but it also has substantial business interests in China and significant Chinese customers who depend on the company's advanced manufacturing services.

The new policy of allowing H200 sales to China potentially shifts TSMC's position. If American companies like Nvidia are selling directly to Chinese customers, TSMC faces less direct pressure to enforce export controls. But TSMC also benefits from maintaining good relationships with both Washington and Beijing, so the company's interests are genuinely complex.

The broader question is whether allowing Nvidia to sell directly to Chinese customers actually strengthens Taiwan's position relative to the U. S. and China, or whether it weakens it. If Taiwan manufactures the chips that Nvidia sells to China, then Taiwan is still a crucial part of the supply chain. But if China develops domestic manufacturing capacity and reduces dependence on TSMC, then Taiwan's leverage declines.

The H200 sales approval might actually accelerate Chinese efforts to develop independent semiconductor manufacturing, which would reduce TSMC's long-term leverage and make Taiwan's strategic position more vulnerable. This is another example of how the policy shift has second-order consequences that aren't fully being considered.

What Happens When the Chips Arrive?

Assume for a moment that the reported approvals are accurate and that Alibaba, Tencent, and Byte Dance are about to receive hundreds of thousands of H200 chips. What happens next?

In the immediate term, Chinese AI companies will finally have the compute resources they've been lacking. They'll accelerate their large language model training. They'll hire more talent. They'll launch products that are closer to competitive with American equivalents. The timeline on which China's AI capabilities reach rough parity with America's probably compresses by 6-12 months.

In the medium term (next 1-2 years), Chinese companies will be running AI workloads at scale. Their engineers will become deeply familiar with H200 architecture. Some of those engineers will move to work on domestic semiconductor development. Some will move to other countries and share knowledge with allies. The knowledge transfer that always accompanies access to cutting-edge technology will accelerate.

In the longer term (3-5 years), China's domestic semiconductor industry will produce alternatives to the H200. These alternatives might be 70-80% as powerful initially, but they'll improve rapidly. They'll be cheaper because they don't need to include all the features of the H200. They'll be fine-tuned for Chinese software and use cases. They'll offer independence from American supply chains.

By the time this happens, Nvidia will no longer have the advantage of selling to China legally (assuming some future administration imposes new restrictions). The company will have had a few years of high profits from selling H200s and other products to Chinese customers. But the long-term consequences will be a Chinese semiconductor industry that can compete, at least partially, with Nvidia's offerings.

For companies like Alibaba and Tencent, having H200 access in the near term and domestic alternatives in the medium term is ideal. They get the best of both worlds. They're never dependent on a single supply, and they have the most competitive technology available at each moment.

For America, the outcome is less clear. Nvidia benefits economically in the near term but potentially faces more competition in the medium term. The broader American semiconductor industry faces new Chinese competitors. The American AI industry faces Chinese AI companies that aren't artificially constrained by lack of compute access.

It's possible that this is the right tradeoff and that the near-term economic benefits outweigh the medium-term competitive costs. But that case isn't being made explicitly, and it's worth examining directly.

The Precedent This Sets

One final consideration is what this policy shift signals about how America will handle technology exports in the future. If the decision to relax restrictions on H200 sales is based primarily on lobbying pressure from Nvidia and economic arguments, what does that signal to other companies with restricted products?

There are other technologies on the export control list. Other companies with products that are currently restricted. Other policymakers who will face similar pressure from industry to relax restrictions. The precedent being set here is that such restrictions are conditional on politics and economics, not on strategy.

This could lead to a more general erosion of American export controls as a tool of statecraft. Every company with a restricted product will have an incentive to lobby for relaxation. Every new administration will face pressure to revisit restrictions. Every recession or profit downturn will create arguments for opening up markets to boost revenues.

Alternatively, this could lead to a bifurcation of American export policy, where some countries have access to American technology and others don't, based on economic and political relationships rather than on security concerns. That might actually be more honest, but it's also more fragile. Once the fiction that exports are restricted for security reasons is dropped, the system is vulnerable to pressure from countries that claim they should also have access.

There's also a question about how allies interpret this. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan all have important semiconductor interests. If those countries are watching the U. S. decide to allow advanced chip sales to China based on lobbying pressure, what does that tell them about how secure their own technology interests are? It tells them that American promises to prioritize security concerns can be overridden by economic arguments. That might encourage them to diversify their supply chains and reduce dependence on American technology.

Which is to say: the policy shift might have implications that extend far beyond the specific case of Nvidia and China.

How Runable Fits Into Modern Tech Infrastructure

While Nvidia chips power the computation that trains and runs AI models, the orchestration layer that actually manages these resources and enables developers to build with them is increasingly important. Platforms like Runable represent the next layer of the stack that abstracts away semiconductor complexity and allows teams to focus on building rather than managing infrastructure.

Runable offers AI-powered automation for creating presentations, documents, reports, and other business outputs. While the underlying computation might run on Nvidia chips (whether sold to America, China, or elsewhere), the orchestration and automation layer is where developers actually spend their time. This kind of platform abstraction becomes even more important in a world where chip access is fragmented and the underlying compute landscape is more complex.

Startups building AI applications today don't need to care whether their compute is running on H200s, domestic Huawei chips, or older Nvidia models. What they need is a development platform that abstracts away those details and lets them focus on business logic. Platforms like Runable starting at $9/month enable this abstraction, making it easier for teams to build AI-powered features without managing the underlying infrastructure themselves.

Use Case: Building internal tools and dashboards without worrying about whether the underlying compute comes from American or Chinese chips

Try Runable For Free

Looking Forward: What 2025 Looks Like

Assuming the H200 sales proceed as reported, the next 12-24 months will be crucial for understanding whether the Trump administration's strategy actually works.

The test is straightforward: does allowing H200 sales to China actually keep Chinese companies dependent on American chips, or does it accelerate their development of domestic alternatives?

If the former is true, then we'll see continued Chinese purchases of Nvidia chips even as domestic alternatives improve. We'll see Nvidia profits growing. We'll see Chinese AI companies remain tethered to American technology and unable to develop competitive domestic alternatives. The strategy will have worked.

If the latter is true, then we'll see Chinese companies gradually shift to domestic chips as they improve. We'll see Nvidia's share of the Chinese market decline over 3-5 years. We'll see Chinese semiconductor companies receiving massive investment and support. We'll see a fragmented global AI chip market where American dominance is qualified. And we'll realize that the policy shift accelerated the outcome it was trying to prevent.

There's not a clear way to know which scenario will occur until we're several years into it. But the bet the Trump administration is making is explicit: short-term economic benefit (Nvidia's profits) outweighs medium-term strategic cost (China developing competitive chip alternatives).

Whether that's the right bet depends on your view of how fast China can develop competitive semiconductor technology and how important it is for America to maintain a significant technological edge in AI. Those are genuinely consequential questions, and they're being answered by a CEO's lobbying campaign and a shift in political winds, not by systematic strategic analysis.

Whatever happens next, one thing is clear: the era of straightforward American semiconductor dominance is ending. Whether it ends because of export controls that were never quite tight enough, or because of a deliberate policy shift that prioritized short-term profits, the result is the same. China will have better access to advanced chips, Chinese companies will develop faster, and the global AI chip market will become more competitive.

From Nvidia's perspective, that's fine as long as the company stays ahead and can maintain dominance through innovation. From America's broader perspective, it's worth thinking carefully about what that future actually looks like.

FAQ

What exactly did Beijing approve regarding Nvidia chips?

Beijing reportedly approved the sale of more than 400,000 Nvidia H200 AI chips to major Chinese companies including Byte Dance, Alibaba, and Tencent under conditional licenses. These approvals represent a significant reversal from the Biden administration's strict export controls that had previously blocked such sales on national security grounds. The deal came during Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang's visit to China and signals a dramatic shift in U. S. technology export policy under the Trump administration.

Why did the Trump administration allow these sales when the Biden administration blocked them?

The Trump administration has adopted a different strategic logic promoted by Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang and White House officials like David Sacks. Their argument is that allowing regulated sales to China is better than losing the market entirely to competitors or smugglers, and that it keeps Chinese companies dependent on American technology. The administration also cites ongoing smuggling of advanced chips to China as evidence that strict export controls are ineffective and that visibility through regulated sales is preferable to blind gray markets.

What does China actually want with these H200 chips?

Chinese AI companies desperately need computational power to train large language models competitive with Open AI and other American firms. Companies like Byte Dance, Alibaba, and Tencent have been severely constrained without access to world-class hardware. However, Beijing's strategy is more nuanced: they want the chips to accelerate near-term AI development while maintaining incentives for domestic semiconductor development that would reduce future dependence on American technology.

How does this affect Nvidia's business and competitiveness?

The approval directly benefits Nvidia by giving the company access to a massive market it had been excluded from for nearly two years. This should significantly increase Nvidia's revenues and profits, which fund the company's research and development for future chip generations. However, the long-term competitive implication is more complex: by providing China with access to cutting-edge hardware, Nvidia may be accelerating China's ability to develop competitive domestic semiconductor alternatives within 3-5 years.

What are the national security implications of allowing H200 sales to China?

The primary concern is that providing access to advanced AI chips accelerates China's development of competitive AI capabilities and reduces the technological gap between American and Chinese AI systems. Additionally, knowledge transfer from Chinese engineers working with H200s could accelerate domestic Chinese semiconductor development, ultimately creating competitors for Nvidia. The longer-term risk is that the policy reversal signals to other countries that American export restrictions are conditional on politics and economics rather than strategy, potentially eroding the credibility of U. S. technology export policy.

How will China actually use these H200 chips?

Chinese companies will use the chips for training large language models and other AI applications at scale. The computing power will allow them to process massive datasets and develop models that are more competitive with American offerings. Additionally, Chinese engineers will gain deep knowledge of Nvidia's hardware architecture, which could inform the development of domestic semiconductor alternatives. The chips will also enable Chinese companies to offer competitive AI services to Chinese customers and enterprises, reducing dependence on American AI platforms.

What's the gray market argument, and does it actually justify allowing these sales?

White House officials argue that advanced chips are already reaching China through smuggling and gray markets despite export controls, so allowing regulated sales provides visibility over the supply chain. However, this argument has a logical flaw: allowing regulated sales likely increases the total volume of chips reaching China rather than simply redirecting contraband. If legal channels become available at lower prices, it might actually accelerate gray market activity as well, since arbitrage opportunities increase.

What happens to TSMC and Taiwan's position in all of this?

TSMC manufactures Nvidia's chips, which means Taiwan remains crucial to the supply chain. However, allowing Nvidia to sell directly to Chinese customers might accelerate Chinese efforts to develop independent semiconductor manufacturing. This could reduce TSMC's market share and strategic leverage long-term. Additionally, if China develops viable domestic chip manufacturing alternatives, Taiwan's position as a critical chokepoint in global semiconductor supply could be undermined.

Could the Trump administration reverse this policy again in the future?

Absolutely. The reversal from Biden's strict controls to Trump's regulated sales demonstrates how contingent technology policy can be on political winds. If future administrations adopt different priorities, export restrictions could be reimposed. This unpredictability is itself strategically costly because it signals to China that restrictions are temporary and can be worked around, providing no long-term strategic anchor.

How does this affect American companies besides Nvidia?

Other American chip companies and tech firms face similar questions about market access and export controls. The precedent being set suggests that lobbying and economic arguments can override export restrictions, which could encourage other companies to push for relaxation of controls on their products. Additionally, American AI companies now face Chinese competitors that have better access to computation resources, potentially narrowing the competitive gap in AI capabilities.

The Bottom Line

Jensen Huang's casual bike ride through Shanghai isn't just a victory lap for Nvidia. It's a symbol of a more fundamental shift in how America is approaching technology competition with China. The decision to allow H200 sales represents a gamble that short-term economic benefits and maintained software lock-in will outweigh the medium-term cost of accelerating China's semiconductor capabilities.

Whether that gamble pays off depends entirely on whether the assumption holding up the entire strategy is correct: that you can simultaneously provide access to cutting-edge technology and maintain technological dominance. History suggests this assumption doesn't survive contact with reality. China has demonstrated repeatedly that it can take access to foreign technology and develop competitive domestic alternatives within a reasonable timeframe.

What's most concerning isn't necessarily the immediate economic impact. It's the signal this sends about the durability and credibility of American technology policy. By reversing course in response to corporate lobbying and political winds, the administration has signaled that export restrictions are conditional on politics, not strategy. That creates exactly the wrong incentives for China: invest in both accessing American technology and developing domestic alternatives simultaneously.

The next decade will reveal whether this policy shift was pragmatic realism or strategic miscalculation. The decision-makers clearly believe the former. The evidence increasingly suggests it might be the latter. But by the time we know for sure, the strategic window to shape the outcome will have closed. That's the real cost of this policy reversal.

Key Takeaways

- Beijing approved 400,000+ H200 chip sales to Chinese companies, reversing 18 months of strict Biden-era export controls

- Trump administration prioritizes economic benefits and maintained software dependency over absolute technological containment of China

- China's dual strategy of accessing American chips while developing domestic alternatives may be more sophisticated than U.S. assumptions

- Gray market smuggling provides convenient justification for policy reversal, though allowing legal sales likely increases total chip flow to China

- Policy whiplash signals to China that export restrictions are temporary and politically contingent, creating wrong incentives for dependency

Related Articles

- SpaceX's Starlink Broadband Grant Demands: What States Need to Know [2025]

- Data Centers & The Natural Gas Boom: AI's Hidden Energy Crisis [2025]

- Tesla's $2B xAI Investment: What It Means for AI and Robotics [2025]

- Doomsday Clock at 85 Seconds to Midnight: What It Means [2025]

- Moltbot AI Assistant: The Future of Desktop Automation (And Why You Should Be Careful) [2025]

- Chrome's Gemini Side Panel: AI Agents, Multitasking & Nano [2025]

![Nvidia's AI Chip Strategy in China: How Policy Shifted [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nvidia-s-ai-chip-strategy-in-china-how-policy-shifted-2025/image-1-1769704891662.jpg)