Introduction: When Court Orders Meet Digital Defiance

A federal judge in Ohio handed down a ruling that sounded definitive. Delete the data. Stop scraping. Cease distribution. The order landed like a gavel strike in a quiet courtroom, and legally speaking, it was airtight. Except nobody expects it to matter.

That's the strange reality of modern copyright enforcement. In January 2024, OCLC (the nonprofit behind World Cat, the world's largest library catalog) sued Anna's Archive for stealing 2.2 terabytes of library metadata. They alleged hacking, server damage, and unauthorized distribution. The shadow library didn't even show up to court.

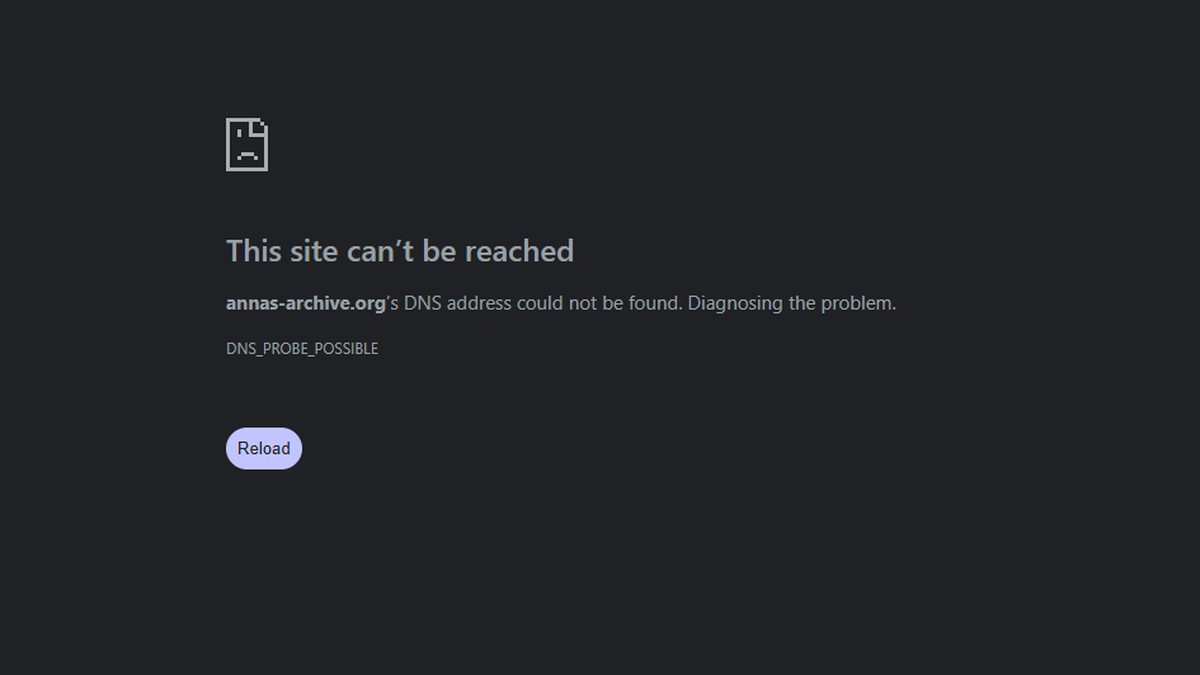

So the judge issued a default judgment. Anna's Archive lost by default. But here's the thing: Anna's Archive is already gone from its original .org domain. It's hosted across multiple jurisdictions. The people running it have made it clear they operate in deliberate violation of copyright law. And the court order, while legally binding, has almost no mechanism for enforcement against an entity that doesn't operate within traditional legal structures.

This case reveals something fundamental about the internet in 2025. Traditional copyright law moves at the speed of courts and injunctions. Digital dissidents move at the speed of code and distributed systems. One operates in the physical world with property rights and enforceable penalties. The other operates in the digital void where jurisdiction is fiction and servers can be anywhere.

The real question isn't whether Anna's Archive will comply with the order. It won't. The question is whether OCLC's strategy of taking this judgment to web hosts will actually work. And more broadly, this case exposes the deepest tension in modern copyright: how do you enforce rules against people who've decided the rules don't apply to them?

What Is Anna's Archive? Understanding the Shadow Library Movement

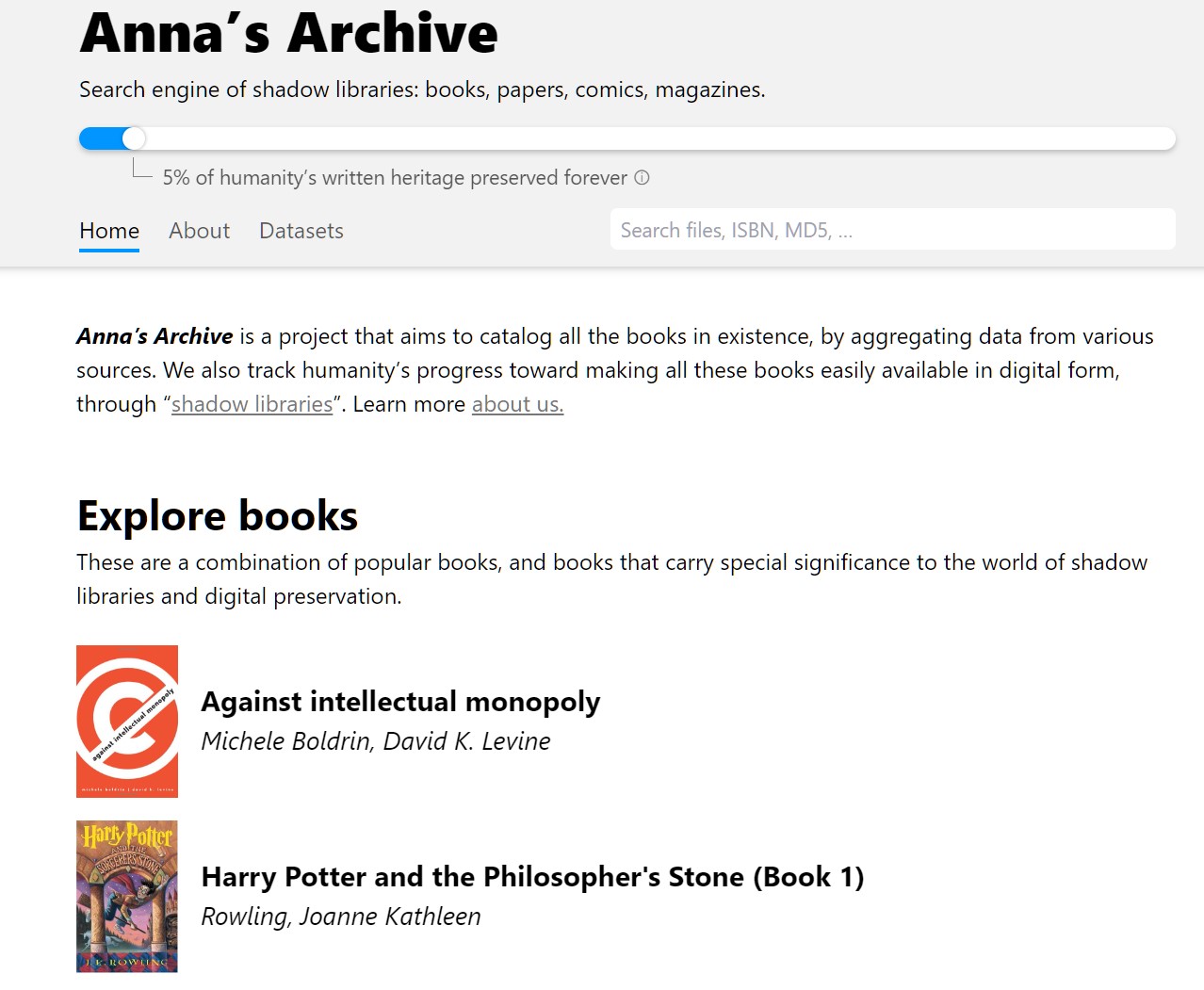

Anna's Archive isn't a traditional torrent site. It's something more sophisticated and more troubling to copyright holders: it's a search engine and index for shadow libraries. Think of it this way. Regular torrents are scattered across the internet like books left in random apartments. You need to know exactly what you're looking for, and you need to search through dozens of sites to find it. Anna's Archive built a unified catalog. Everything in one searchable place.

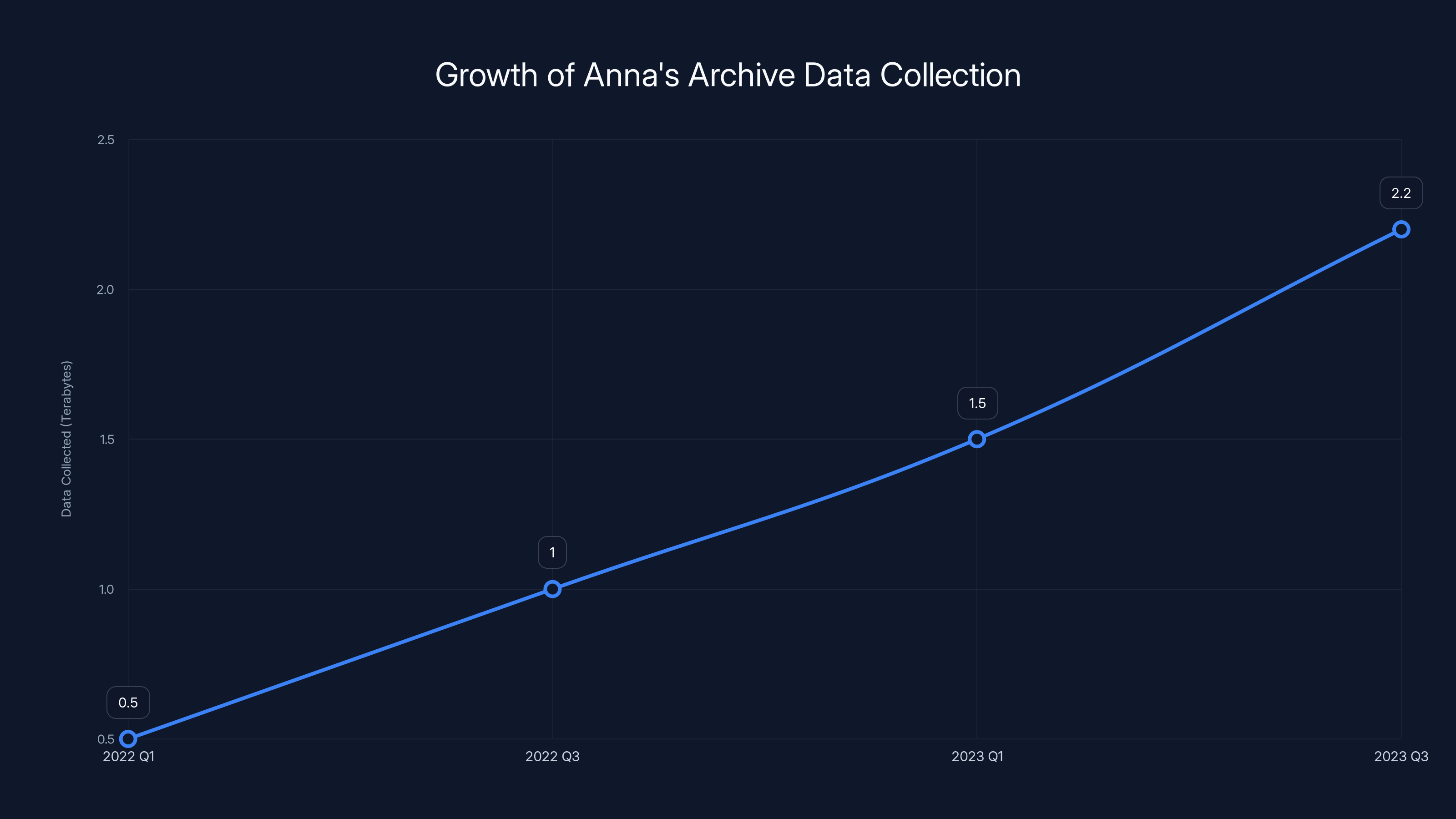

The operation started in 2022 with an ambitious mission: preserve human knowledge by creating redundant copies of books, journals, and academic papers. The founder (known only as "Anna") released archives of major academic publishing databases, including copies of material from standard databases and library catalogs. The site grew rapidly because it solved a real problem: legitimate researchers, students in developing countries, and autodidacts suddenly had access to materials that were otherwise locked behind paywalls or institutional accounts.

But Anna's Archive didn't stop at passive distribution. It actively expanded its scope. The platform began scraping data from World Cat, one of the largest and most valuable library resources in the world. Operated by OCLC on behalf of thousands of member libraries, World Cat contains detailed metadata about millions of books: publication data, language, subject classifications, and links to where copies exist in libraries worldwide.

This metadata is valuable precisely because it's comprehensive and well-organized. In October 2023, Anna's Archive publicly announced it had scraped all 2.2 terabytes of World Cat data. The founder published a blog post explaining the reasoning: OCLC maintains monopoly-like control over library metadata. By distributing it freely, Anna's Archive could help identify which books desperately needed preservation and create backup systems that couldn't be controlled by any single organization.

The scraping operation was sophisticated. It disguised automated requests as legitimate search engine bots from Bing and Google. It took place over the course of a year, exploiting security vulnerabilities that OCLC gradually patched. According to the court documents, by the time OCLC fully closed the gaps, Anna's Archive had already obtained essentially complete copies of the database.

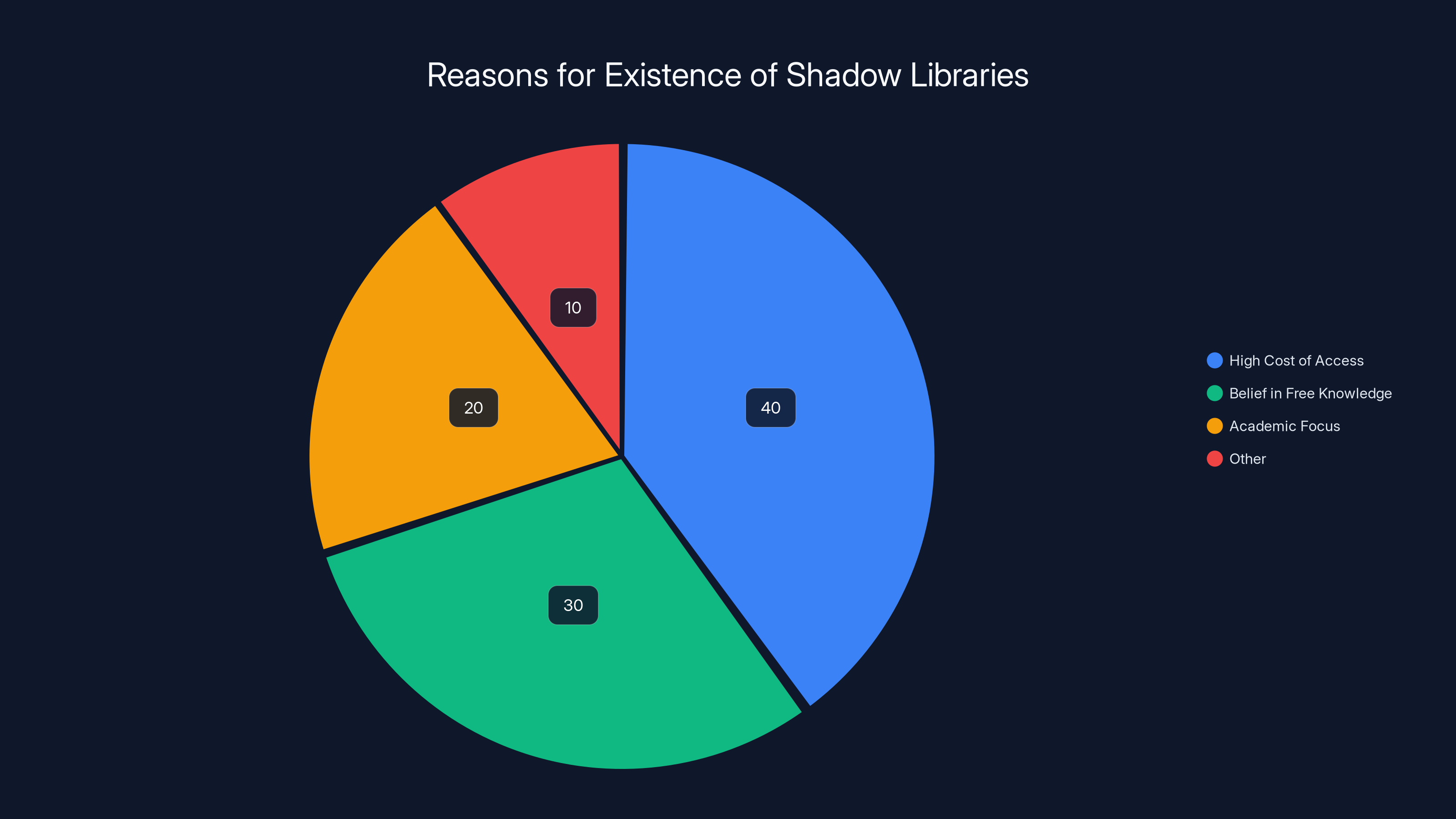

Estimated data shows that high access costs and belief in free knowledge are major drivers for the existence of shadow libraries. These libraries aim to make academic materials more accessible.

The Cyberattack Claims: What Actually Happened at World Cat

OCLC framed this as a cyberattack. The language in the lawsuit is serious and specific: persistent attacks that crashed the website, slowed it dramatically, damaged servers, and forced OCLC to devote significant resources to network infrastructure enhancements.

The legal framing makes sense from OCLC's perspective. If you're a nonprofit maintaining a critical library resource, and someone starts hammering your servers with thousands of automated requests per minute, it does look like an attack. Your users experience outages. Your engineers spend nights doing emergency infrastructure work. Your organization suffers real costs.

But there's another way to describe the same technical phenomenon: it's what happens when you aggressively scrape a website that wasn't designed for aggressive scraping.

Anna's Archive's own description of the process was remarkably candid. The founder explained that the scraping took advantage of security flaws in World Cat's infrastructure. These weren't catastrophic security breaches requiring sophisticated hacking. They were the ordinary vulnerabilities that emerge when a service built decades ago encounters modern automated scraping techniques. Anna's Archive found them, exploited them, and gradually watched OCLC patch them over the course of a year.

Was this an attack? Technically yes. Was it also a form of civil disobedience rooted in genuine ethical conviction? Absolutely.

The court accepted OCLC's framing. Judge Michael Watson granted a default judgment on breach-of-contract claims related to World Cat.org's terms of service and on trespass-to-chattels claims (an old legal concept that essentially means damaging or interfering with someone else's property). The ruling was unambiguous about the facts: Anna's Archive deliberately scraped World Cat, caused harm to the system, and refused to acknowledge the lawsuit.

But what the court order didn't address was the deeper question of whether this harm was proportional to the scope of the copyright infringement at stake, or whether the public interest in preserving access to library metadata outweighed OCLC's property rights.

The Default Judgment: What It Means and What It Doesn't

Default judgments are a legal cudgel. When a defendant doesn't appear in court or respond to claims, the court assumes the allegations are true and rules against them automatically. The judgment against Anna's Archive was clear: delete all copies of World Cat data, stop scraping, stop distributing, and never do it again.

But here's where reality diverges from legal theory.

Default judgments work when the defendant is a company with assets, employees, and a physical location. You can seize bank accounts. You can garnish wages. You can block business operations. The legal system has leverage.

Anna's Archive has none of those characteristics. It's run by unknown individuals operating across multiple jurisdictions. There are no employee payroll records to subpoena, no headquarters to raid, no bank accounts registered under the organization's name. The site exists as distributed code, hosted on servers whose locations are deliberately obscured.

OCLC clearly understood this limitation. That's why they explicitly stated in their court filings that the judgment's real purpose was to pressure web hosts and infrastructure providers. OCLC said they planned to take the judgment to hosting companies and demand they remove Anna's Archive from their platforms.

This is the actual enforcement mechanism for internet-based copyright claims in 2025: you can't go after the infringer directly, so you pressure the infrastructure providers who host them. You convince payment processors to cut them off. You get ISPs to block their domains. You make it expensive and inconvenient to operate.

It's not perfect, but it's the closest thing we have to enforcement against distributed systems that deliberately operate outside national jurisdictions.

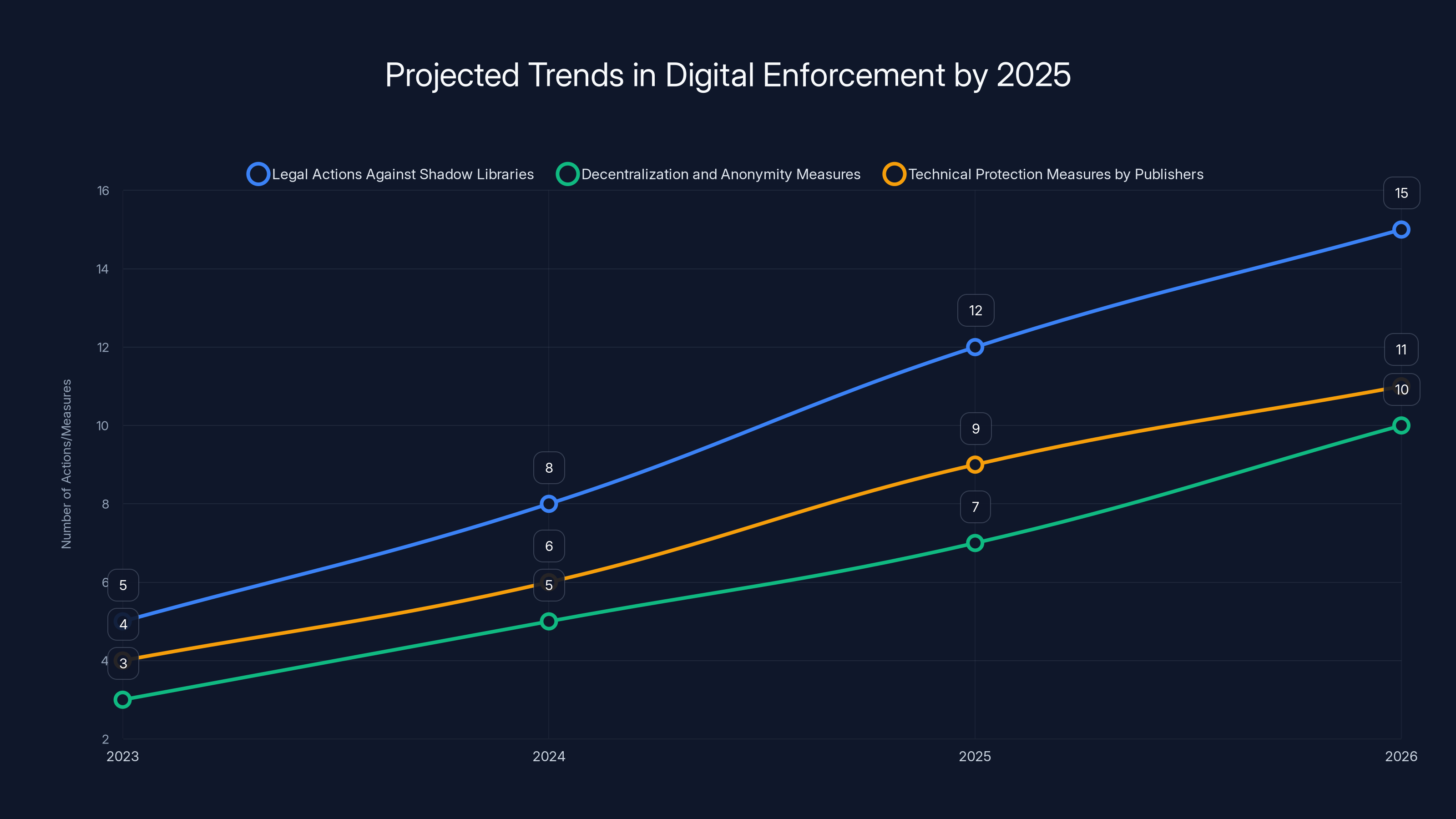

Estimated data suggests an increase in both legal actions against shadow libraries and the sophistication of decentralization measures by 2025.

Why the Court Order Probably Won't Work: The Infrastructure Challenge

Let's be blunt about the obstacles OCLC faces.

First, Anna's Archive lost its original .org domain, but it didn't disappear. It simply migrated to other domain extensions and infrastructure providers. The core lesson of modern internet censorship is that you can't kill a service that's prepared to be decentralized. Every time a domain gets seized or a host shuts down an account, the content reappears somewhere else.

Second, the data is already copied everywhere. OCLC can demand that Anna's Archive delete the World Cat data, but copies of that data are now hosted on distributed archival systems, torrent networks, and private servers. The horse left the barn in 2023 when Anna's Archive announced the scrape publicly. You can't un-announce something on the internet.

Third, and most critically, OCLC has no jurisdiction over most of the infrastructure hosting Anna's Archive's content. Internet hosting is global. If Anna's Archive uses servers in countries with weak IP enforcement, or in jurisdictions that don't recognize OCLC's copyright claims, the court order becomes a symbolic gesture rather than a practical tool.

The hosting infrastructure argument is interesting because it shows the limits of one legal system trying to control a borderless technology. OCLC can threaten hosting companies registered in the United States, the European Union, or other copyright-respecting jurisdictions. But for every major host that complies, there are smaller providers, privacy-focused services, and international companies that either can't comply or won't prioritize a U. S. court order.

Fourth, Anna's Archive has explicitly stated that it operates in intentional violation of copyright law. The founder wrote that they deliberately violate copyright "in most countries" because it allows them to accomplish something "legal entities cannot do: making sure books are mirrored far and wide." This isn't an organization that's going to wake up one day and suddenly decide to respect intellectual property.

It's a profound statement about motivation. Anna's Archive isn't trying to make money from copyright infringement. It's not a business model. It's an ideological position: that certain knowledge should be freely available, and that legal restrictions on knowledge distribution are unjust.

When your opponent's core conviction is that your legal rights are illegitimate, court orders become less persuasive.

The World Cat Metadata Question: Is This Really Copyright Infringement?

Here's where the case gets philosophically complicated.

OCLC owns World Cat. That part is clear. But what exactly is OCLC owning? Is it the creative expression in the literary works themselves? Or is it the database compilation of metadata about those works?

These are different things with different legal protections.

Copyright protects creative expression. The text of a novel, the illustrations in a picture book, the specific words a journalist used to describe an event. But copyright explicitly does not protect facts. You can't copyright the fact that the Earth orbits the Sun, or that Napoleon died in 1821, or that a particular book was published in 1984 by Penguin Press.

World Cat is primarily a compilation of facts about books. Author names. Publication dates. ISBN numbers. Subject classifications. Call numbers. These are facts, not creative expression. Copyright law does protect compilations through what's called "database rights," but the protection is narrower and more contested than copyright in creative works.

Anna's Archive's argument (though not explicitly articulated in court) would be that copying factual metadata is different from copying a copyrighted book. OCLC didn't create the facts in World Cat—they compiled existing facts. That compilation might be valuable, but is it the kind of intellectual property that should justify blocking access to library information?

OCLC's argument is different. They invested decades and substantial resources in building, maintaining, and improving World Cat. The database is their product. Libraries pay for access to it. Even if the underlying facts are uncopyrightable, the arrangement, structure, and enhancement of those facts represents valuable intellectual property.

The court accepted OCLC's framing without seriously examining this distinction. The default judgment assumed the allegations were true, which meant the judge never had to grapple with the question of whether copying library metadata truly constitutes copyright infringement in the way that copying actual books does.

This matters because it defines what kind of precedent this case sets. If courts treat database metadata the same as copyrighted creative works, it strengthens corporate control over information. If courts recognize that facts are facts, even when compiled into databases, it suggests that some information should be more freely available.

The Broader Shadow Library Ecosystem: Anna's Archive Isn't Alone

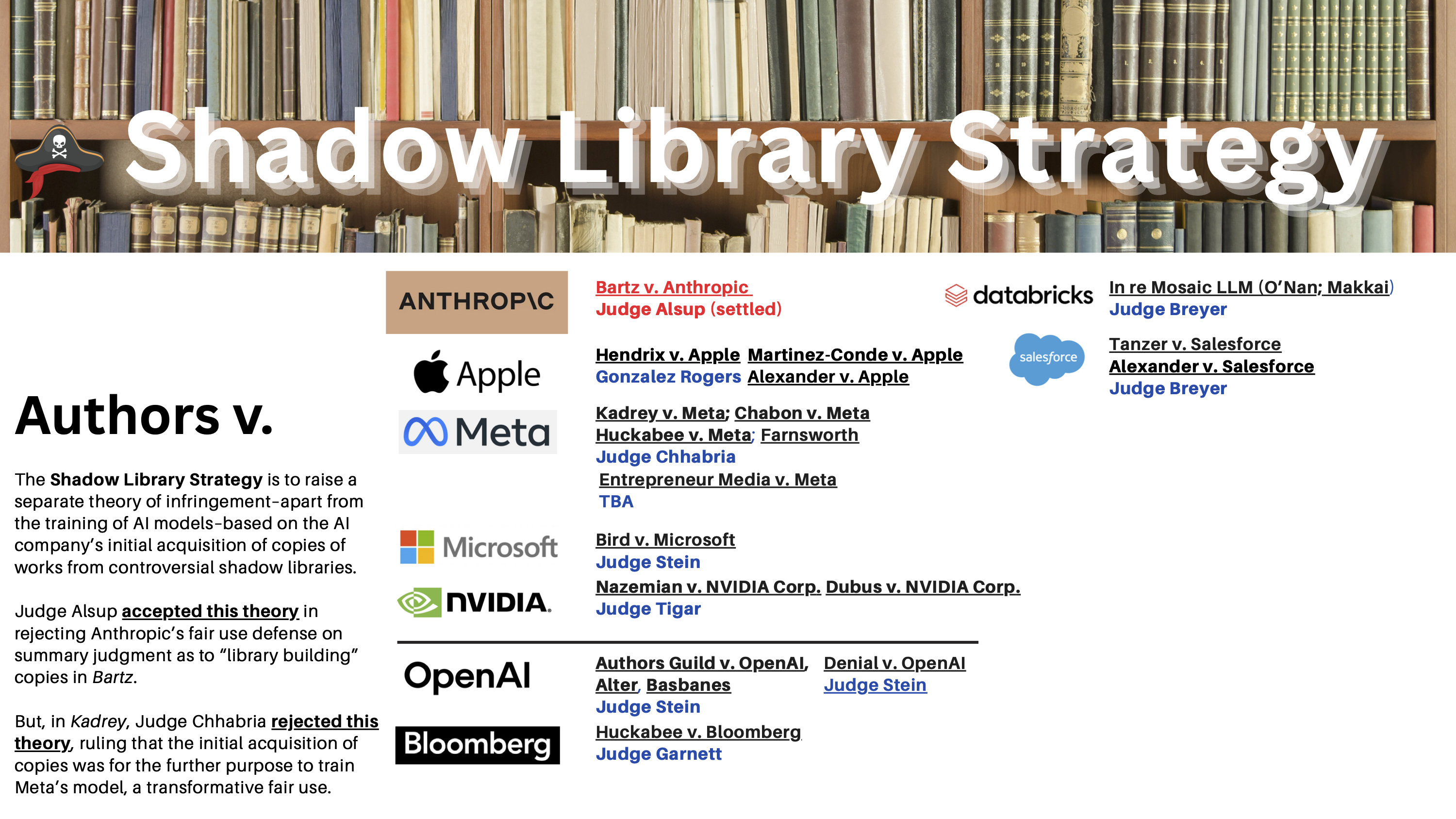

Anna's Archive exists within a broader movement of digital preservation and knowledge distribution that operates in the legal gray zone.

Lib Gen, the Library Genesis project, has been operating for over a decade. It hosts millions of academic papers and textbooks, all freely available. Sci-Hub, created by Kazakhstani programmer Alexandra Elbakyan, focuses specifically on academic journals and has been the subject of intense legal battles with the publishing industry.

These aren't isolated rebels. They're part of a growing conviction, particularly among scientists and educators in developing countries, that academic paywalls are fundamentally unjust. Why should a researcher at a wealthy American university have access to cutting-edge research that a brilliant researcher in Nigeria cannot afford?

The traditional publishing industry's response has been to aggressively pursue legal action. Elsevier has sued Sci-Hub repeatedly. Various publishers have gone after Lib Gen. But the response has been like trying to stop water flowing downhill with a dam made of wet paper.

Each legal action generates more attention, more supporters, and more distributed copies. The more famous the legal battle, the more people mirror and backup the content.

Anna's Archive's expansion beyond books into music (the 300TB Spotify mirror) suggests the shadow library movement sees itself as a more general response to artificial scarcity and digital gatekeeping. If knowledge is cordoned off by paywalls and subscriptions, shadow libraries position themselves as a counterweight.

The court order against Anna's Archive lands in this context. It's one enforcement action against one service, but it's part of a larger pattern of copyright holders attempting to use law and infrastructure pressure to maintain control over digital information.

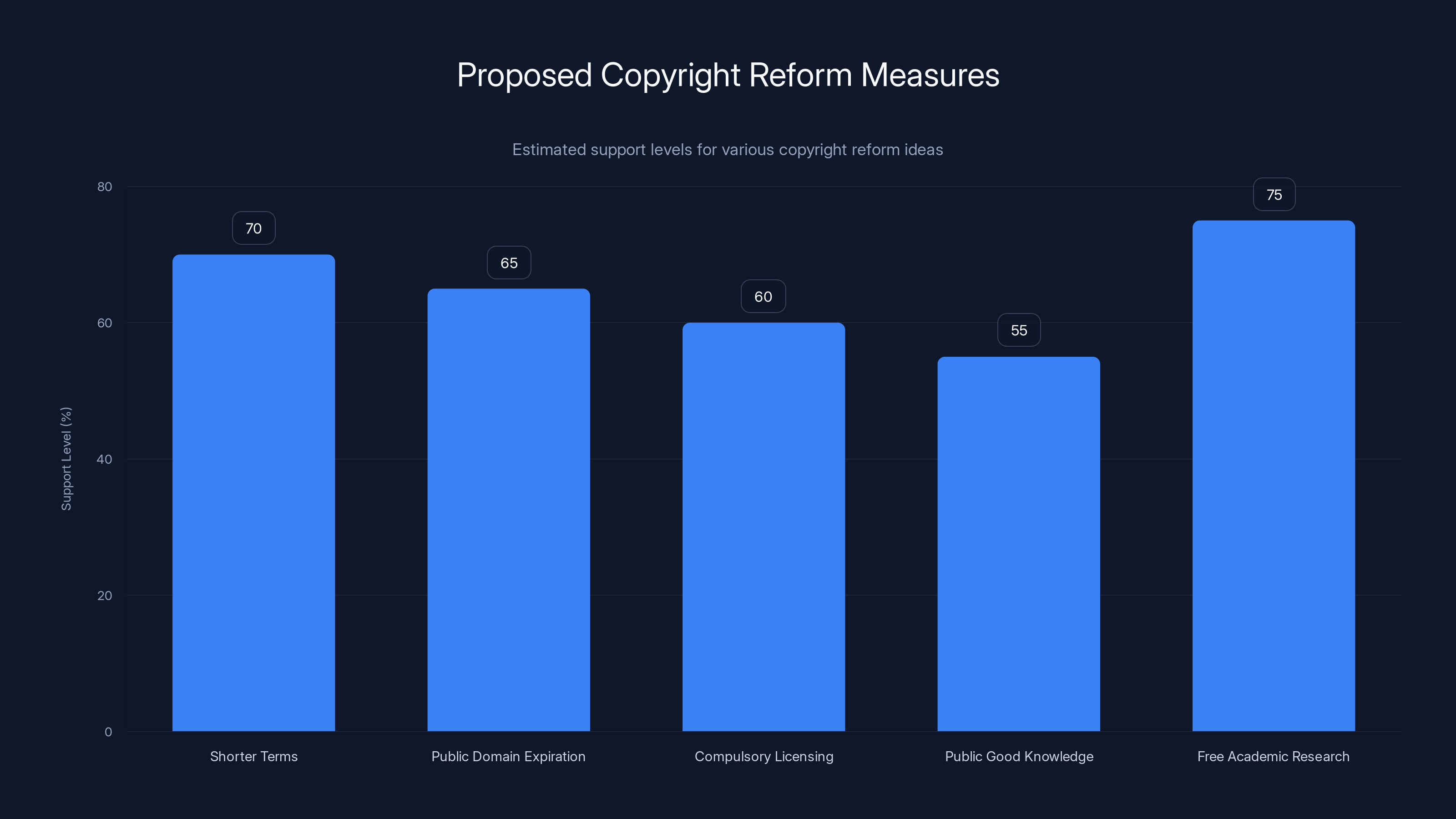

Estimated data suggests varying levels of support for different copyright reform proposals, with free academic research and shorter copyright terms receiving the highest support.

OCLC's Enforcement Strategy: Targeting the Hosting Layer

OCLC's plan to leverage the judgment against web hosts is strategically smart, and it's the only realistic enforcement mechanism available.

The strategy works like this: Take the default judgment to hosting companies. Show them they're potentially liable for facilitating copyright infringement if they continue hosting Anna's Archive. Create legal liability for the infrastructure provider rather than trying to pursue the infringer.

This approach has worked before. The MPAA used similar strategies to get sites like The Pirate Bay removed from various hosting providers. The threat of legal action, combined with public pressure, convinced many companies to shut down services.

But there are practical limits.

First, hosting infrastructure is increasingly distributed. Anna's Archive can use content delivery networks that are deliberately designed to resist takedowns. They can use bulletproof hosting services that cater specifically to legally controversial content and are registered in jurisdictions where U. S. court orders have limited effect.

Second, the cost-benefit calculation for hosting providers is different today than it was a decade ago. A major U. S.-based hosting company (AWS, Google Cloud, Azure) will probably comply with a U. S. court order. But a mid-tier hosting provider in Eastern Europe or Southeast Asia might see compliance as harmful to their customer base and decline.

Third, content distribution has evolved. Anna's Archive could rely on distributed systems like IPFS (Inter Planetary File System) or BitTorrent networks where there's no central host to pressure. In such systems, the "hosting" is done by thousands of individual users, making centralized takedowns essentially impossible.

OCLC understands this. Their statement about leveraging the judgment against hosts acknowledges they're going for what's achievable rather than what's comprehensive. They're hoping to raise the friction high enough that some users turn away.

The Ideological Divide: Property Rights vs. Knowledge Access

This case isn't really about the World Cat data specifically. It's a surface expression of a deeper conflict about what should and shouldn't be owned.

On one side: Organizations like OCLC and the publishing industry argue that intellectual property rights create incentives for investment and quality. OCLC invested resources in building a comprehensive library catalog. They should be able to control and monetize that investment. Without property rights, they argue, there's no motivation to build valuable information systems.

On the other side: Advocates for open knowledge argue that information has network effects. Knowledge becomes more valuable when it's widely distributed and built upon. Restrictions on knowledge distribution are fundamentally anti-innovative and harm society, particularly in developing countries where paywalls create insurmountable barriers to education and research.

Anna's Archive's founder articulated this clearly: "We deliberately violate the copyright law in most countries. This allows us to do something that legal entities cannot do: making sure books are mirrored far and wide."

Notice the assumption embedded in that statement: legitimate, legal organizations can't distribute books freely because copyright law prevents them. So someone operating outside the law is necessary to accomplish something the law actually prevents.

This is where digital civil disobedience enters the conversation. It's not that Anna's Archive is trying to make money or shirk responsibility. It's that they believe copyright law itself is wrong, and they're willing to violate it openly to prove a point.

Court orders have limited power against that conviction. Laws are most effective when people believe in their legitimacy. When a substantial portion of the population—particularly in academic and developer communities—view copyright law as unjust rather than merely inconvenient, enforcement becomes a war of attrition with no clear victor.

The 2.2TB Question: What Exactly Did Anna's Archive Steal?

The court described the World Cat theft as 2.2 terabytes of data. That's a large number that sounds massive.

But context matters. 2.2TB is mostly metadata: structured information about books rather than the books themselves. It's the difference between stealing a library's card catalog versus stealing its entire book collection.

Metadata is lightweight compared to content. 2.2TB could represent metadata about tens of millions of books, academic papers, and other resources. It's comprehensive, but it's not the full text of every work in the catalog.

This distinction matters legally. OCLC's lawsuit focused on the metadata theft and the damage to their servers from the scraping process. They didn't claim that Anna's Archive had stolen copyright-protected creative works (though Anna's Archive has separately republished those).

The question becomes: Is metadata theft the same kind of offense as copyright infringement?

For database compilation, maybe. OCLC invested in organizing and structuring this information. That arrangement has value. But the underlying facts—that a particular book was published in 1984, or that it was classified under a particular subject heading—remain uncopyrightable facts.

The court order doesn't really distinguish between metadata and content. It just says delete all copies and stop using World Cat data. But the practical impact of that order falls unevenly. Deleting copies of book metadata is one thing. Trying to delete copies of actual books from the shadow library ecosystem is essentially impossible.

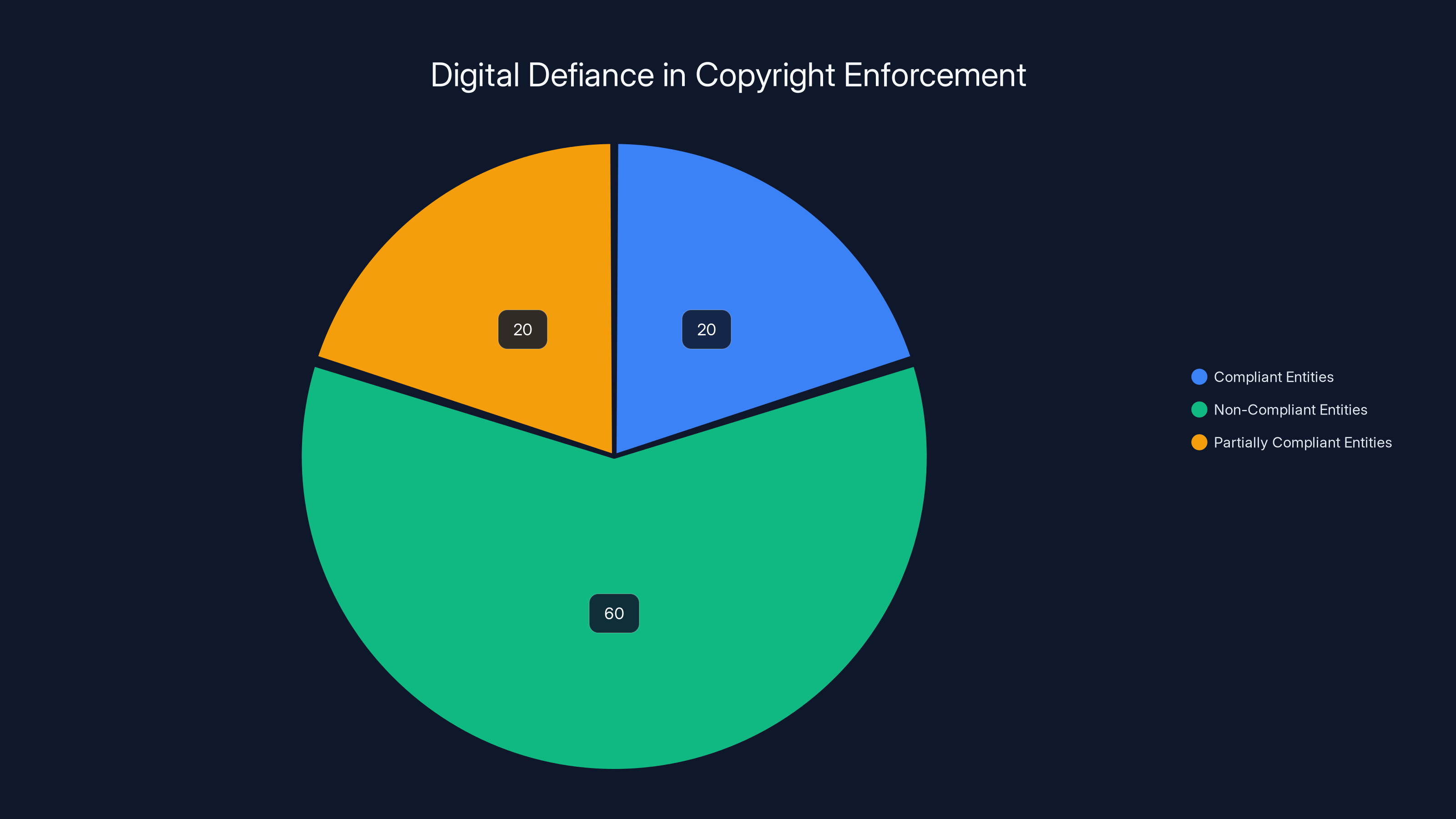

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of digital entities choose non-compliance with copyright orders, highlighting challenges in enforcement.

The Jurisdiction Problem: Why U. S. Courts Struggle With Global Internet Issues

One of the most fundamental problems with enforcement is jurisdiction.

A U. S. federal judge in Ohio issued an order. That order is legally binding within the United States. But Anna's Archive isn't necessarily operating from U. S. servers, and the individuals running it aren't necessarily within U. S. jurisdiction.

If Anna's Archive is being run from a country that doesn't recognize U. S. copyright law, or doesn't have an extradition treaty with the United States, then the judgment is symbolic rather than enforceable.

This is true for most shadow libraries and digital services that deliberately position themselves outside the Western legal system. Sci-Hub's creator is in Kazakhstan. Lib Gen's operators have been in multiple countries. Anna's Archive's founder is anonymous and could be anywhere.

U. S. courts can order compliance, but they can't force compliance for services that are deliberately structured to be beyond their reach.

This is where the hosting layer becomes so important. By pressuring U. S.-based or EU-based companies that host content, OCLC can indirectly enforce the judgment even against operators who are personally outside U. S. jurisdiction.

But that's also where it breaks down. If Anna's Archive moves to hosting providers outside U. S. jurisdiction, the enforcement mechanism fails completely.

The broader lesson is that the internet has outpaced the jurisdictional assumptions underlying copyright law. Copyright enforcement assumes a world where creators and distributors operate from fixed locations with identifiable assets. But digital services can be distributed, decentralized, and deliberately jurisdictionally ambiguous.

Previous Shadow Library Takedowns: What Actually Works?

OCLC isn't the first organization to take legal action against shadow libraries. The track record is instructive.

The MPAA and RIAA have spent decades suing individual infringers and services. They've had some successes. The original Pirate Bay was seized and its founders prosecuted. Megaupload was shut down with dramatic FBI raids. But torrenting and file-sharing didn't disappear. They evolved.

Sci-Hub has faced repeated lawsuits from Elsevier and other publishers. Publishers have obtained default judgments against it, got its domains seized, and pushed payment processors to cut it off. And yet Sci-Hub remains online and widely used.

The pattern suggests that legal enforcement against shadow libraries operates at a friction level rather than a stopping point. Every legal victory raises the friction—makes the service harder to access, more dangerous to use, more technically complex to operate. But it rarely eliminates the service entirely.

Part of this is technical. Distributed systems and decentralized hosting are genuinely difficult to take down at scale. Part of it is cultural. Once knowledge is widely copied and backed up, it's essentially impossible to delete.

Part of it is ideological. The operators of these services often see legal opposition as validation of their moral position. A court order against Sci-Hub doesn't persuade its creator that copyright law is just. It confirms her conviction that the law is unjust.

The Reality of Digital Enforcement in 2025: What the Future Holds

The Anna's Archive case represents a collision between two legal philosophies that are increasingly incompatible.

One philosophy says that property rights—including intellectual property—are foundational. Organizations invest resources based on the assumption that they'll maintain exclusive control over their creations. Without that protection, investment incentives disappear.

The other philosophy says that certain kinds of information (educational materials, scientific knowledge, cultural works) are too important to restrict. That the internet has made unlimited copying possible, making artificial scarcity both technically impossible and morally questionable.

These aren't easily reconcilable positions.

For OCLC and the publishing industry, the path forward involves better technical protection, more aggressive legal action, and infrastructure pressure. They'll pursue cases like this one, trying to establish that unauthorized database scraping has serious consequences.

For shadow library operators, the path involves further decentralization, better anonymity, and more sophisticated hosting infrastructure. They'll argue (and arguably prove) that knowledge distribution is too important to be controlled by paywalls.

The court order against Anna's Archive will probably result in some friction for the service. It might pressure certain hosting providers to remove content. It might raise the operational costs of running the service. But it probably won't kill the service or eliminate the data already distributed.

The most likely outcome is that Anna's Archive continues operating on different infrastructure, the World Cat data remains available to users who know how to find it, and a few years from now there's another lawsuit against another shadow library making the same arguments and reaching the same practical stalemate.

This is what copyright enforcement looks like in an age of digital abundance and decentralized systems. Legal victories that feel thorough but prove incomplete. Orders that sound definitive but can't be enforced. Cases that set precedent without changing behavior.

Anna's Archive rapidly expanded its data collection, reaching 2.2 TB by late 2023, driven by its mission to preserve knowledge. (Estimated data)

The World Cat Monopoly Question: Is OCLC's Control Justified?

Before we move past the merits of the case, it's worth examining whether OCLC's control over World Cat is actually justified.

OCLC is a nonprofit cooperative of libraries. It was founded in 1967 to provide shared cataloging and resource-sharing services. The mission was noble: help libraries pool resources and serve users better through shared data and systems.

But over time, World Cat became a monopoly. It's not that other organizations couldn't build library catalogs. It's that World Cat was so comprehensive and well-maintained that alternatives couldn't compete. Libraries integrated their catalogs with World Cat. Researchers and librarians became dependent on it.

Now OCLC controls the most comprehensive library metadata in existence. They charge libraries for access. They restrict how the data can be used. They maintain absolute control over who can download it and for what purpose.

Anna's Archive's argument was essentially that this monopolistic control is harmful. A nonprofit shouldn't maintain a stranglehold over library metadata. That data should be openly available so that alternative services could emerge and libraries could control their own information.

It's a legitimate argument about market power and access.

OCLC's counter-argument is that they maintain the database for the benefit of libraries, that the data quality and comprehensiveness requires ongoing investment, and that open distribution would harm their ability to fund that work.

Both arguments have merit. But the court order decided the case without really examining the monopoly question. The judgment was on the narrow grounds of unauthorized access and breach of terms of service.

The broader question—whether certain library metadata should be publicly available as a matter of principle—remains unresolved. And that's arguably the more important question than whether Anna's Archive has the legal right to scrape worldcat.org.

Copyright Law's Failure to Adapt: Why We Keep Having These Conflicts

Underlying the Anna's Archive case is a more fundamental problem with modern copyright law: it was designed for a world where copying was expensive.

In 1976, when the current Copyright Act was written, copying a book required a printing press and distribution infrastructure. Copying a song required manufacturing vinyl records or cassette tapes. The law was built assuming that copying would remain expensive and logistically complex.

Then the internet happened.

Copying a digital file is now free and instantaneous. You can distribute something to millions of people with a mouse click. The scarcity that copyright law assumed—that unauthorized copies would be rare and difficult—disappeared completely.

Copyright law responded by getting more restrictive. Digital Rights Management (DRM), the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), takedown notices, and aggressive litigation became standard. The legal system tried to recreate artificial scarcity through technological and legal restrictions since natural scarcity no longer existed.

But this approach creates obvious injustices. A researcher in a developing country can't afford academic journal subscriptions that cost thousands per year. Knowledge that should be freely available becomes locked behind paywalls. Educational materials become prohibitively expensive.

Shadow libraries like Anna's Archive emerge in response to these injustices. They're not primarily motivated by profit or theft. They're motivated by the conviction that restricting knowledge is wrong.

The legal system keeps issuing court orders as if the problem is technical—if we can just shut down the service, access will be restricted. But the real problem is structural. As long as knowledge restriction is perceived as unjust, people will find ways to distribute knowledge regardless of legal consequences.

Solving this problem requires rethinking copyright law itself, not just enforcing existing law more aggressively.

The Academic Research Ecosystem: How Shadow Libraries Enable Innovation

One reason shadow libraries have such cultural support is their role in the academic research ecosystem.

Academic publishing creates a weird economic situation. Researchers write papers as part of their jobs (funded by universities and grants). Academic journals peer-review and publish those papers, adding value through editorial and review processes. But then universities have to pay exorbitant subscription fees to access the papers that their own researchers wrote.

It's a system where researchers are essentially paying publishers to read their own work.

Sci-Hub was created specifically to break this cycle. Alexandra Elbakyan, a programmer frustrated by paywalls preventing her from accessing research, built a tool that could bypass paywalls and distribute research freely.

Courts have repeatedly ruled against Sci-Hub. Elsevier and other publishers have pursued injunctions, takedowns, and legal action. And yet Sci-Hub is still operating and widely used in the academic community, particularly in developing countries where journal subscriptions are economically impossible.

Anna's Archive serves a similar function for books and academic materials beyond journal articles. Researchers, students, and autodidacts use it to access materials they couldn't otherwise afford.

Does this reduce publisher and author revenue? Probably. Does it also enable research and learning that wouldn't otherwise happen? Definitely.

The court order against Anna's Archive treats this as a straightforward intellectual property violation. But the academic community increasingly sees shadow libraries as a necessary response to a broken publishing system.

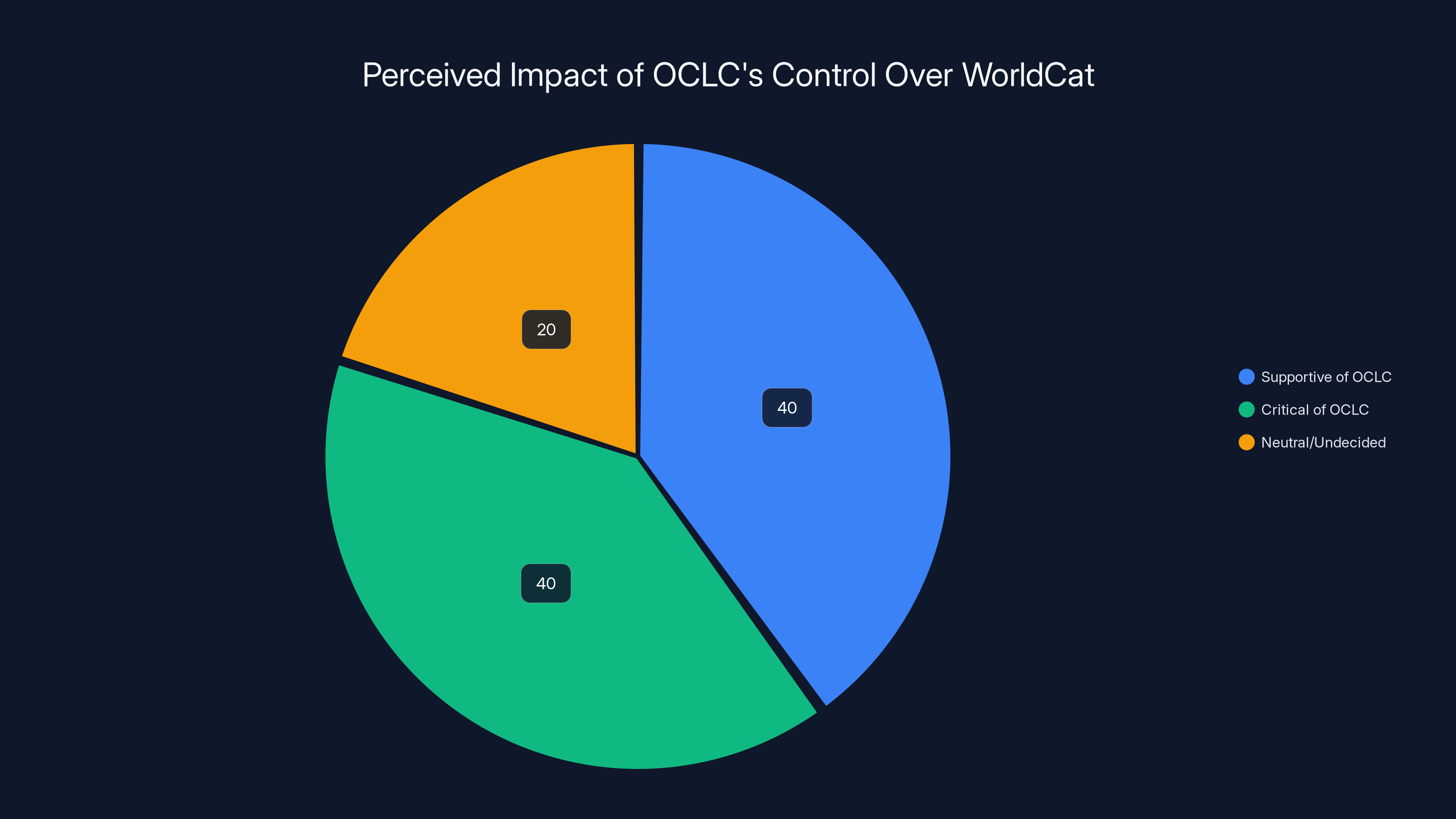

Estimated data suggests a balanced distribution of opinions on OCLC's control over WorldCat, with equal portions supporting and criticizing the monopoly, and a smaller portion remaining neutral or undecided.

What Happens Next: The Remaining Claims and Future Litigation

The default judgment against Anna's Archive wasn't the end of the case.

OCLC filed additional claims beyond breach of contract and trespass-to-chattels. They alleged tortious interference with contract (claiming Anna's Archive was interfering with OCLC's relationships with its member libraries) and unjust enrichment.

The court rejected both of these claims. The tortious interference claim lacked necessary legal components. The unjust enrichment claim was preempted by federal copyright law, which means copyright law supersedes any state law claims about unfair enrichment.

This is actually significant. It suggests that if OCLC wants to pursue additional claims, they're going to be limited to federal copyright claims or the breach-of-contract and trespass-to-chattels claims already decided.

OCLC has 30 days to file a status report or a motion to dismiss its remaining claims. This suggests they might pursue additional litigation, or they might decide the default judgment is enough leverage for their hosting-provider strategy.

The case is likely far from over, but the most important ruling has already been issued. The judgment establishes that scraping World Cat is legally prohibited and creates a documented basis for pressure on hosting providers.

Whether that's actually effective at stopping Anna's Archive from continuing operations is a separate question.

The International Dimension: How Global Services Operate Outside U. S. Law

One factor that hasn't been extensively discussed in coverage of the Anna's Archive case is the international dimension.

Anna's Archive has users worldwide. Its mission is global knowledge preservation. But copyright law, particularly strong copyright protection, is primarily a Western phenomenon.

Countries like China, Russia, India, and many developing nations have weaker copyright enforcement. In some cases, they explicitly reject certain Western copyright restrictions as harmful to their own development.

This means that even if OCLC successfully pressures U. S.-based hosting providers, Anna's Archive could relocate to servers in countries with weaker intellectual property enforcement.

This is actually a strategic advantage for shadow libraries. Copyright enforcement is ultimately enforced by national governments, and not all governments prioritize intellectual property protection with equal vigor.

Furthermore, many of Anna's Archive's users are in countries where affordable legal access to knowledge is simply not available. The service serves a real need that the legal market doesn't fulfill.

This international dimension means that OCLC's legal victory in U. S. court might have limited practical effect. The service can operate elsewhere. Users will continue accessing it. The distributed nature of the internet means location is increasingly irrelevant for digital services.

The Broader Copyright Reform Conversation

The Anna's Archive case is one data point in a larger conversation about copyright reform.

Many technologists, legal scholars, and advocates argue that copyright law is too broad and too long. Copyright terms have been extended repeatedly, lasting far longer than the original constitutional idea of "limited times" to incentivize creation.

Some suggest major reforms: Shorter copyright terms (perhaps 20 years instead of life-plus-70 years). Automatic expiration of works into the public domain. Compulsory licensing for educational and research use. Reclassification of certain factual databases as public information.

Others argue for more radical changes: Treating knowledge as a public good and restricting copyright to commercial contexts. Making academic research freely available by default. Separating copyright from access (you can copy for personal use, but can't commercially republish).

These reform efforts are slow and often blocked by industries with strong lobbying power. But they represent a genuine conversation about whether copyright law as currently written serves the public interest.

Anna's Archive exists precisely because these reforms haven't happened. Faced with copyright law that the operators believe is unjust, they've decided to violate it openly and distribute knowledge anyway.

The court order against them doesn't address this underlying reform conversation. It just enforces the law as it exists. But the ongoing operation of shadow libraries despite repeated legal defeats suggests that law enforcement alone might not be sufficient to change behavior when the underlying law is seen as illegitimate.

Practical Implications for Libraries, Researchers, and Users

For people actually using Anna's Archive and similar services, what does the court order mean?

Short term: Probably not much. The service will likely continue operating on different infrastructure. Users who are already using it will probably continue to do so. The World Cat data they've already accessed remains accessible to them.

Medium term: There might be friction. Some hosting providers might shut down related services. Payment processors might cut off donations or funding. Domain registrars might refuse to register new domains. These create inconvenience without necessarily killing the service.

Long term: The precedent might discourage some organizations from creating similar services. If you're building a library preservation project and you know you'll face legal action and default judgments, it might change your risk calculus.

For researchers and students relying on shadow libraries, the practical takeaway is that legal access to knowledge remains expensive and restricted in many parts of the world. The existence of shadow libraries represents an attempt to solve that problem outside the legal system.

Whether you view that as admirable civil disobedience or troubling copyright theft probably depends on your baseline assumptions about whether copyright law is just.

FAQ

What is Anna's Archive?

Anna's Archive is a shadow library and search engine that indexes and distributes copies of books, academic papers, and other written materials. Created in 2022, it functions as a unified catalog for searching content that's typically restricted by copyright or paywall restrictions. The service distinguishes itself by providing metadata organization and searchability across multiple shadow library sources.

How does the court order against Anna's Archive work?

A federal judge in Ohio issued a default judgment against Anna's Archive for scraping 2.2 terabytes of data from World Cat, the library catalog operated by OCLC. The order requires Anna's Archive to delete all copied World Cat data, cease scraping activities, and stop distributing the data. The judgment was issued by default because Anna's Archive didn't respond to the lawsuit, so the court assumed the allegations were true.

Why doesn't OCLC expect the court order to be enforced?

OCLC acknowledged that they expect limited compliance because Anna's Archive operates without identifiable assets, employees, or physical location. The organization has deliberately structured itself to be beyond the reach of traditional legal enforcement. OCLC's stated strategy is to use the judgment as leverage against web hosting providers rather than trying to force Anna's Archive itself to comply.

What is a shadow library and why do they exist?

Shadow libraries are online repositories that distribute copyrighted materials freely, typically including academic journals, textbooks, and books that would otherwise be behind paywalls or restricted. They exist because legal access to knowledge is prohibitively expensive in many parts of the world, and their operators believe that knowledge should be freely available. Services like Sci-Hub and Lib Gen operate similarly, focusing on academic materials.

Is copying library metadata the same as copyright infringement?

The legal distinction between metadata (information about books like titles, authors, publication dates) and actual copyrighted content is debated. While metadata consists of facts that can't be copyrighted, OCLC argues that the specific compilation and arrangement of that metadata represents valuable intellectual property subject to database rights. Anna's Archive treats all information as legitimately shareable, while OCLC maintains it as proprietary.

What happens if web hosting providers don't comply with the judgment?

If hosting providers don't remove Anna's Archive, they could face legal liability for facilitating copyright infringement. However, providers outside U. S. jurisdiction aren't bound by U. S. court orders, and Anna's Archive can migrate to international hosting providers with weaker copyright enforcement. The effectiveness of OCLC's strategy depends on whether major hosting companies comply and whether Anna's Archive can find reliable infrastructure elsewhere.

Could this court order be enforced against Anna's Archive founders personally?

Theoretically, OCLC could pursue criminal copyright enforcement against the individuals running Anna's Archive if they could identify them and they were located in jurisdictions that recognize U. S. copyright law. However, Anna's Archive's operators have deliberately maintained anonymity and potentially operate from countries with weak IP enforcement, making personal prosecution extremely difficult.

How does this case compare to previous shadow library lawsuits?

The Anna's Archive case mirrors lawsuits against Sci-Hub and other shadow libraries. Previous legal actions have obtained judgments and domain seizures but haven't eliminated the services. The pattern suggests that legal enforcement raises operational friction without achieving complete suppression. Shadow libraries typically migrate to new infrastructure after legal defeats and continue operating.

Will the Anna's Archive judgment affect other online services that use scraping?

The judgment could set a precedent that aggressive scraping of protected databases constitutes trespass-to-chattels and breach of contract. This might influence the legal strategies of other organizations that engage in scraping, though the specific application would depend on whether they're scraping protected databases versus publicly available data with fewer legal restrictions.

What legal reforms would need to happen to make shadow libraries unnecessary?

Major copyright reforms could include: shorter copyright terms, automatic public domain conversion, compulsory licensing for educational use, open access requirements for publicly-funded research, and reclassification of certain factual databases as public information. These reforms are debated in academic and policy circles but face strong industry opposition.

Conclusion: When Legal Victories Don't Translate to Practical Enforcement

The federal court's order against Anna's Archive represents a curious artifact of 2025 internet law: a technically complete legal victory with uncertain practical effects.

On paper, the ruling is decisive. A judge found that Anna's Archive violated contractual terms, caused harm to OCLC's systems through aggressive scraping, and must now delete all copied data. The order is signed and enforceable.

But enforcement is another matter entirely.

Anna's Archive wasn't in court and doesn't intend to comply. The organization's operators view copyright law as illegitimate. They've deliberately structured the service to be distributed across multiple jurisdictions and hosting providers. The data they scraped is now redundantly copied across multiple systems. And the ideological conviction that motivated the scraping in the first place remains unchanged.

OCLC understands this. Their plan to leverage the judgment against hosting providers is actually a sophisticated acknowledgment of enforcement's real limits. You can't force a decentralized service to comply with orders issued in a single jurisdiction. But you can pressure infrastructure providers who are subject to U. S. law and might face liability.

This strategy might work to some degree. Some hosting providers will probably comply. Some users will probably face friction accessing the service. Some infrastructure will probably be disrupted.

But the core problem won't be solved. The data is too widely distributed. The conviction too deeply held. The service too technically resilient.

In that sense, the Anna's Archive case reveals something fundamental about the limits of copyright law in the digital age. Laws are most effective when they're seen as legitimate and when people believe in their underlying justice. But copyright law increasingly faces opposition from people who believe it restricts knowledge unjustly.

When your opponent's position is that the law itself is wrong, court orders become less persuasive. When your opponent has deliberately structured themselves beyond your jurisdiction, enforcement becomes impossible.

So OCLC will take the judgment to hosting providers. Anna's Archive will shift to new infrastructure. Users will continue accessing the service if they need it. And in a few years, there will probably be another lawsuit against another shadow library making the same arguments and reaching the same practical stalemate.

This is what copyright enforcement looks like in the age of digital abundance and decentralized systems. Technically clean legal victories that practically change very little. Orders that sound authoritative but can't be executed. Cases that establish precedent without changing behavior.

The real question isn't whether Anna's Archive will comply with the court order. It won't. The real question is whether copyright law as currently structured can survive in a world where copying is free and information wants to be free. That's a question no court order can answer.

Key Takeaways

- Federal courts can issue default judgments against shadow libraries, but enforcement mechanisms are limited when defendants operate in decentralized, jurisdictionally ambiguous systems

- Anna's Archive operates in deliberate violation of copyright law, viewing restrictions on knowledge distribution as fundamentally illegitimate—making court orders less persuasive than traditional enforcement against profit-motivated entities

- OCLC's enforcement strategy relies on pressuring hosting providers rather than directly pursuing Anna's Archive, but international infrastructure alternatives undermine the effectiveness of this approach

- Shadow libraries persist despite repeated legal defeats because copyright law itself is increasingly seen as unjust by researchers and knowledge-sharing advocates, particularly in developing countries where paywalls create information inequality

- The case reveals fundamental limits of copyright enforcement in the digital age: legal victories that sound authoritative often produce minimal practical effects against services designed to be beyond jurisdictional control

Related Articles

- Anna's Archive .org Domain Suspension: What It Means for Shadow Libraries [2025]

- Public Domain 2026: Betty Boop, Pluto, Nancy Drew [2025]

- AI Identity Crisis: When Celebrities Own Their Digital Selves [2025]

- Bully Online Mod Shutdown: Why Rockstar Killed the Viral Game [2025]

- Matthew McConaughey Trademarks Himself: The New AI Likeness Battle [2025]

- OpenAI Contractors Uploading Real Work: IP Legal Risks [2025]

![Anna's Archive Court Order: Why Judges Can't Stop Shadow Libraries [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/anna-s-archive-court-order-why-judges-can-t-stop-shadow-libr/image-1-1768601228118.jpg)