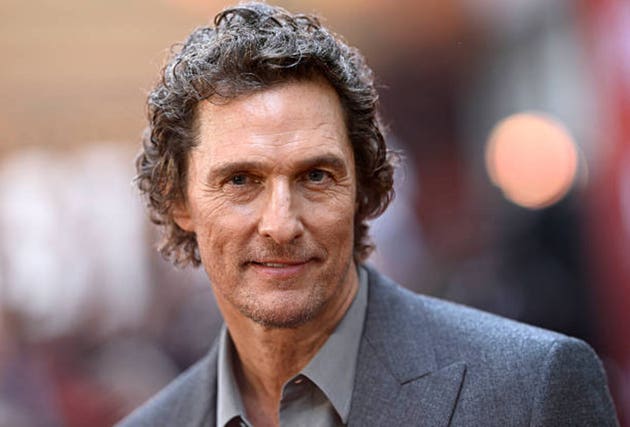

Matthew McConaughey Trademarks Himself: The New AI Likeness Battle [2025]

TL; DR

- 8 trademarks approved: Matthew McConaughey successfully trademarked his image, voice, and signature phrases to block unauthorized AI use, as reported by the Wall Street Journal.

- Proactive legal strategy: His approach addresses legal gaps between existing likeness laws and emerging AI technology.

- Industry precedent: Other celebrities and athletes are following similar strategies to protect digital personas, as noted by Stimson Center.

- Undefined rules: Courts haven't yet ruled on how trademarks apply to AI-generated likenesses, making this a critical test case.

- Bottom Line: The entertainment industry is racing to secure intellectual property before AI synthetic media becomes impossible to control.

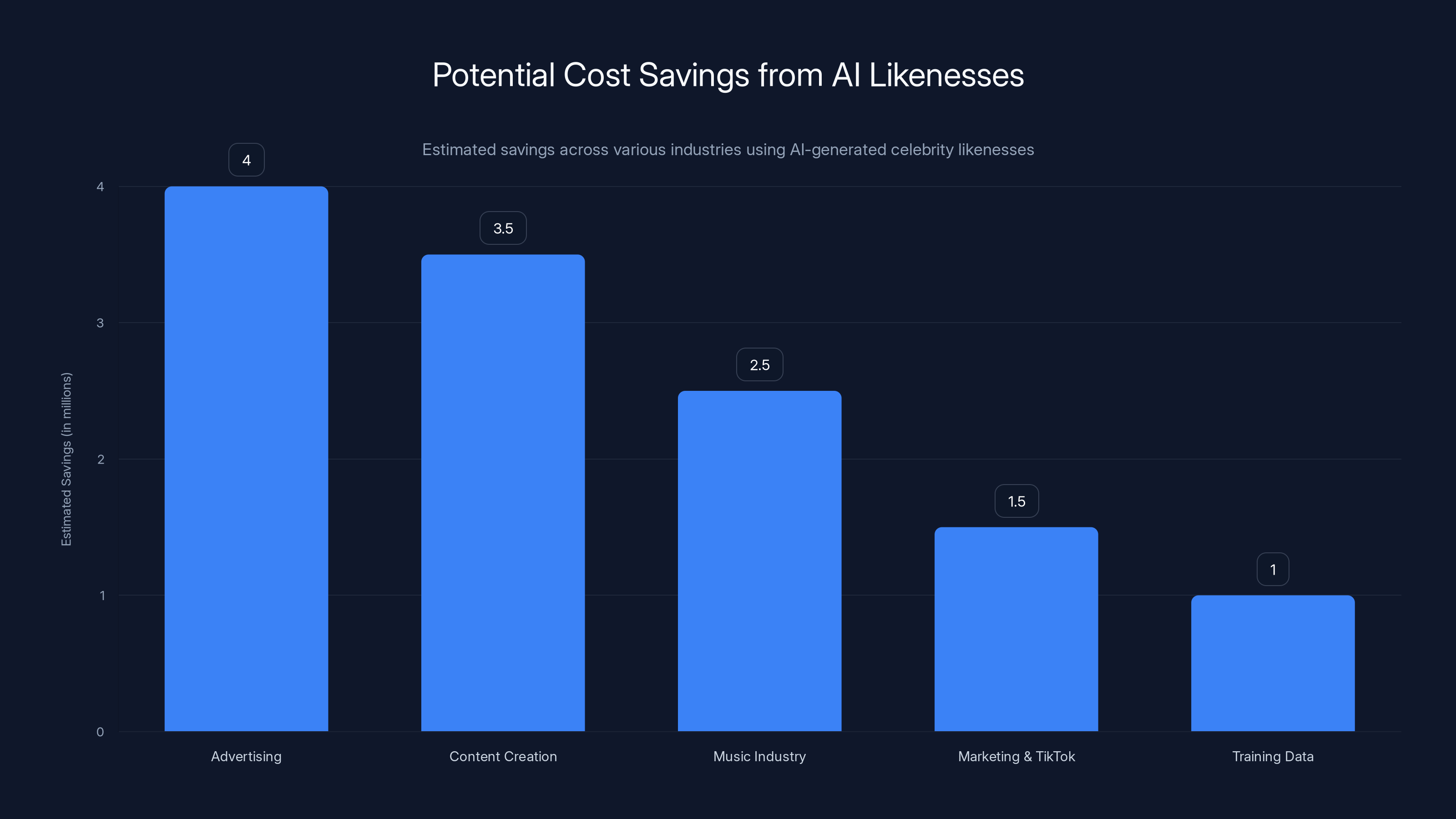

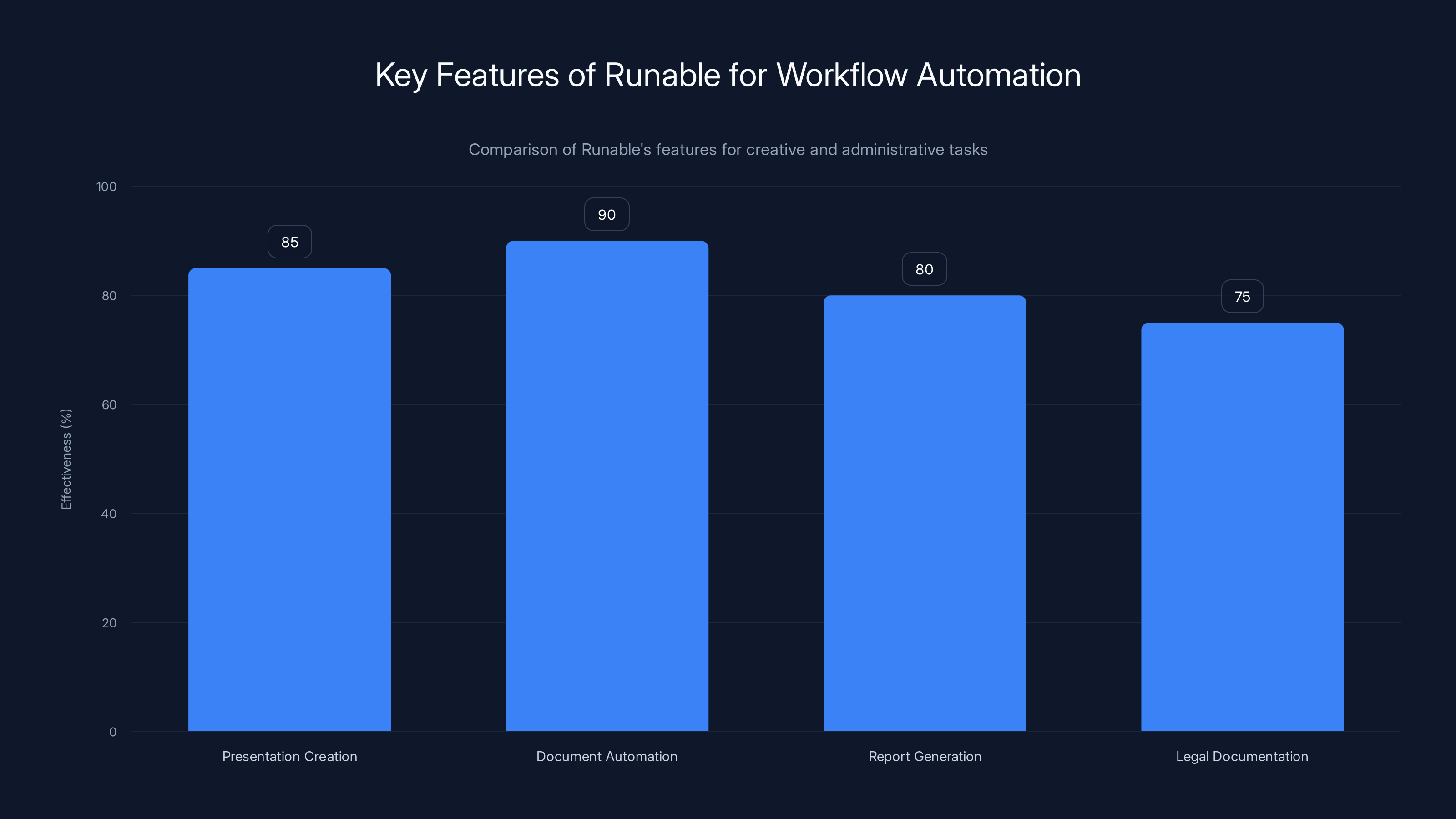

Companies can save millions by using AI-generated celebrity likenesses instead of hiring real celebrities, with advertising seeing the highest potential savings. Estimated data.

Introduction: When Your Voice Becomes Property You Must Defend

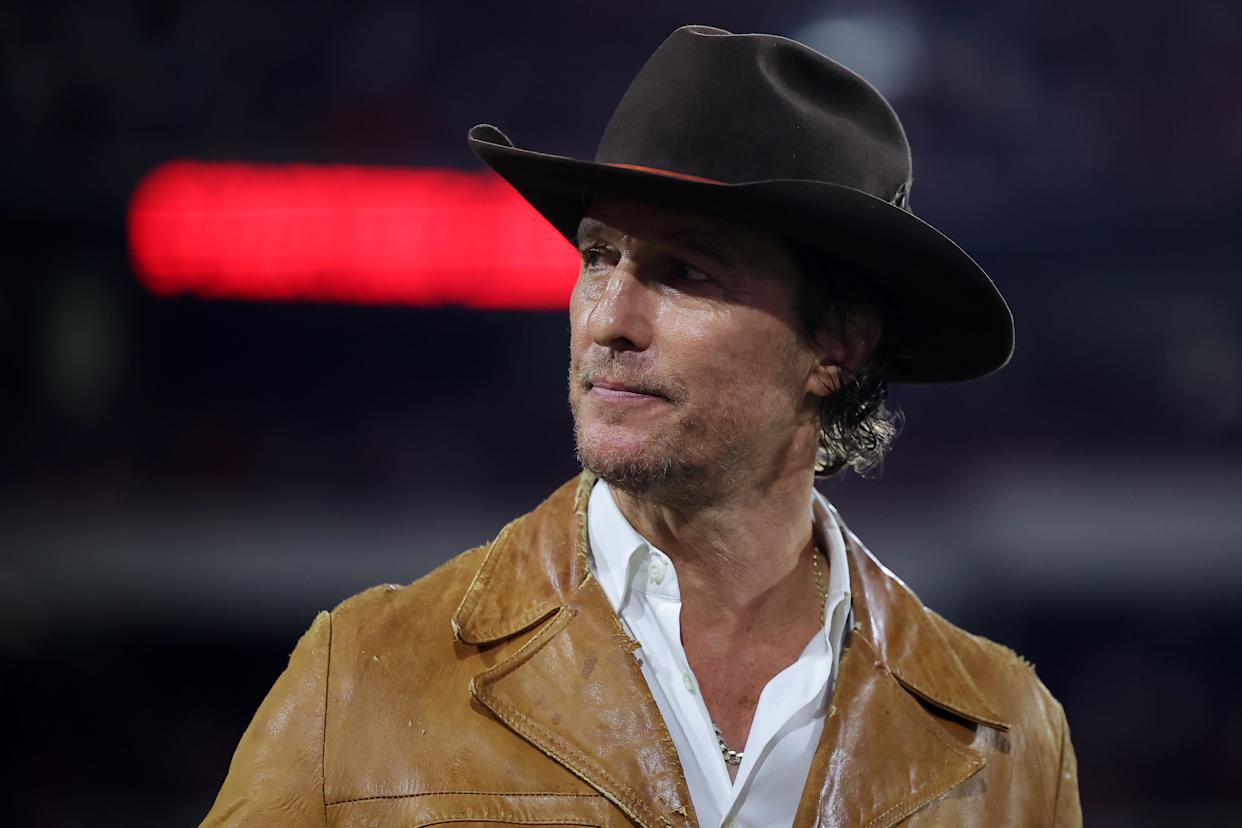

Matthew McConaughey didn't wait around for Hollywood's AI problem to fix itself. In one of the most pragmatic celebrity moves of 2025, the actor behind "alright, alright, alright" decided to claim ownership of his own likeness in the most literal way possible: by trademarking himself.

This isn't your typical celebrity vanity project. McConaughey filed trademark applications for eight specific representations of his likeness, voice, and signature phrases. The US Patent and Trademark Office has approved them all so far. These aren't abstract rights either. They're concrete digital assets: a video of him standing on a porch, an audio clip of his famous catchphrase, recordings of him staring, smiling, and talking.

On the surface, this looks like overkill. Isn't it already illegal to steal someone's likeness? Technically, yes. But here's where it gets complicated. The law protecting people's likenesses was written for a different era. It addressed unauthorized use of your face on a t-shirt or your voice in a commercial. It didn't anticipate a world where AI could generate perfect replicas of your voice, face, and mannerisms in seconds without your permission.

McConaughey's move reveals something important about the current state of digital rights: the legal infrastructure is broken. Existing laws assume you're either using someone's actual image or not. They don't account for the middle ground where AI creates something that looks, sounds, and acts like Matthew McConaughey but was never actually recorded or authorized.

The trademark strategy is clever because it takes advantage of a different legal framework. Trademarks are designed to protect commercial identity and prevent consumer confusion. By trademarking his specific likenesses and phrases, McConaughey is essentially claiming ownership of his commercial identity in a form that AI companies can't legally use without his permission. It's not a perfect solution, but it's a shield built from existing law adapted to a new threat.

What makes this story significant isn't just that one actor is protecting himself. It's that this move signals how celebrities, tech companies, and lawmakers are all figuring out digital rights in real time. McConaughey's trademark strategy might become the template that everyone else follows. Or it might become obsolete the moment courts rule on whether trademarks actually apply to synthetic media.

The real question isn't whether McConaughey will win if someone challenges his trademarks. It's whether his strategy will become the new standard for anyone with a valuable public image. And that answer could reshape how entertainment, advertising, and technology companies interact with the celebrities they use to sell products.

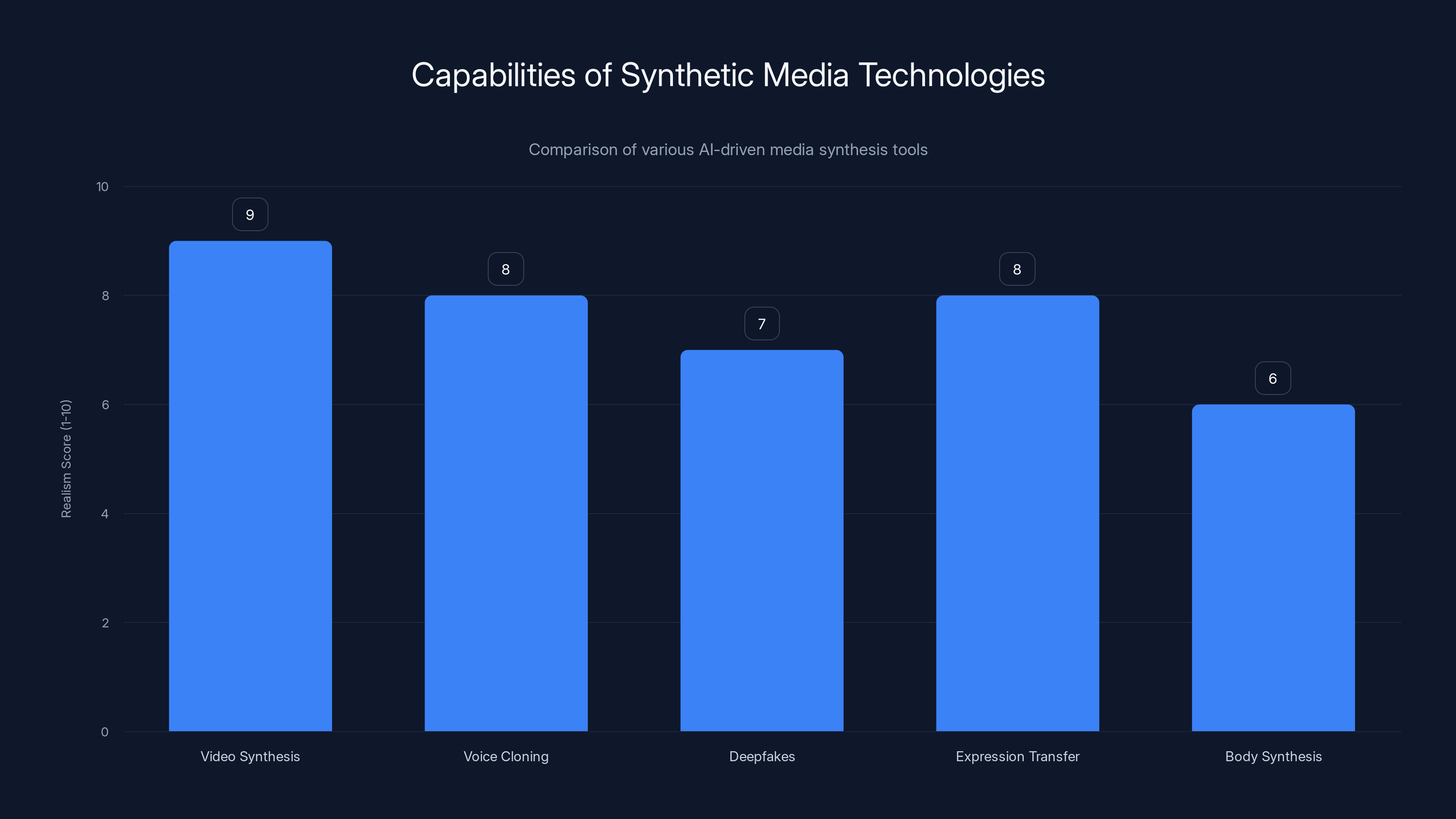

Estimated data: Video synthesis and voice cloning achieve the highest realism scores, making them particularly effective for creating convincing synthetic media.

The Problem: AI Can Copy Your Face Better Than You Can

Why Existing Laws Are Broken

The law protecting someone's likeness has a fundamental assumption built into it: there's a difference between using the real thing and faking it. A company that puts your face on merchandise without permission is clearly stealing your likeness. A company that creates a deepfake video of you saying something you never said is obviously infringing on your rights. This seems straightforward.

Except modern AI makes that distinction meaningless. Tools like Synthesia, Runway, and others can generate video of a person speaking with perfect lip sync and natural expression. Eleven Labs can clone a voice from a few minutes of audio. These aren't cheap Hollywood tricks anymore. They're scalable, affordable, and getting better every month. A small marketing company can now create synthetic media that would've required a major studio budget five years ago.

The legal problem is timing. Existing likeness laws require proof of actual commercial harm. You have to show that someone used your likeness to sell something and that it damaged your reputation or cost you money. The process takes years. By the time you win a lawsuit, the deepfake has been seen by millions of people and is essentially impossible to remove from the internet.

Also, there's the question of what counts as "your likeness" when AI is involved. If someone creates an AI video of you that you never recorded, is that still your likeness? Or is it a synthetic creation that happens to look like you? Courts haven't decided. Some argue that once you've given permission to use your image, companies can use that image for any purpose with AI. Others argue your likeness is your property regardless of how it's generated.

McConaughey's lawyer, Kevin Yorn, put it bluntly: they don't know how courts would rule if someone challenged the trademarks. That's the real problem. There's no clear legal path forward, so celebrities are improvising. Some hire lawyers to send cease-and-desist letters. Others pursue DMCA takedown notices. McConaughey is trying the trademark approach, which transforms the problem from "did you damage my reputation" to "are you using my trademarked commercial identity without permission."

It's a different burden of proof. It's stronger. It's also completely untested.

The 2023 SAG-AFTRA Strike as a Warning Signal

McConaughey's trademark move didn't happen in a vacuum. It followed directly from one of Hollywood's biggest labor battles. In 2023, the Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA) went on strike against major studios. AI was one of the central issues. Actors wanted explicit protections: studios couldn't create digital replicas of their performances without consent and compensation. Actors couldn't be deepfaked into nude scenes or other roles they didn't agree to. Digital likenesses couldn't be sold or reused indefinitely.

The union won some protections. Studios agreed not to use an actor's digital likeness in a film without explicit consent. They agreed to compensate actors for these digital doubles. But the agreement only covers traditional studio productions. It doesn't touch advertising, social media, independent films, or smaller productions. And it definitely doesn't touch AI companies creating synthetic media for fun.

The strike revealed a scary gap in how the entertainment industry was thinking about AI. For decades, studios used stunt doubles and body doubles. That was a solved problem. AI doubles are different. They're scalable. They're economical. They make it possible for a studio to create an actor's performance without that actor ever showing up to set. For budget-conscious production, that's incredibly appealing.

Actors saw this coming. The strike was partly about putting legal guardrails around that technology before it became standard. But it was also a warning signal that the existing legal framework wasn't going to cut it. McConaughey's trademark strategy suggests he took that warning seriously and decided to build his own guardrails.

How Trademark Protection Works: A Stronger Legal Foundation

Why Trademarks Beat Likeness Laws

Here's the key difference: trademark law operates on a simpler principle than likeness law. A trademark protects a mark (image, word, phrase, sound) that identifies your commercial source. If someone uses your trademarked mark in a way that confuses consumers about the source of a product or service, that's infringement. Done. There's no need to prove financial harm or intent to steal your reputation. You just have to show the mark is registered and someone used it without permission.

This is powerful for McConaughey because trademark law doesn't care how the mark is created or replicated. It doesn't matter if the video of him staring and smiling is original footage or AI-generated. If his video is trademarked and someone uses a similar video to sell a product or service, they're infringing.

The legal theory goes like this: McConaughey's trademarked likenesses are commercial marks. They identify him as the source of entertainment and endorsements. If an AI company creates a synthetic video of Matthew McConaughey speaking about their product, consumers might believe McConaughey actually endorsed it. That's trademark confusion. That's infringement.

Trademark infringement is also faster to address than likeness theft. You can file a takedown notice. You can get a court order blocking use. You don't have to wait years for a jury to decide if damage occurred. The mark is either used without permission or it isn't.

But there's a catch. Trademark law has limits. The mark has to be used "in commerce" in a way that identifies a source of goods or services. If someone just posts a deepfake video on social media for entertainment purposes, is that using the mark in commerce? Maybe not. Trademark law might not cover that.

Also, trademark protection depends on continuous use and enforcement. If McConaughey doesn't actively police his trademarks and stop infringing uses, the marks could become genericized or abandoned. That means maintaining a permanent legal operation to monitor AI companies, send letters, and file lawsuits. It's exhausting.

What Gets Protected: Eight Approved Trademarks

McConaughey's eight approved trademarks are specific. They're not a blanket protection of his image. They're discrete, identifiable marks:

Video likenesses: A video of him standing on a porch. Videos of him staring. Videos of him smiling. Videos of him talking. These aren't his entire persona. They're specific moments and gestures that identify him commercially.

Audio likenesses: An audio recording of him saying "alright, alright, alright," his signature catchphrase from the 1993 movie Dazed and Confused. This one is brilliant because it's so distinctive. There's probably no other way to say that phrase that sounds like Matthew McConaughey.

The strategy: Each trademark targets a specific commercial identity marker. When an AI company wants to create synthetic media of McConaughey, they'd have to avoid these specific marks. They could probably create a video of him talking (different from the trademarked "talking" video). But they probably can't create a video of him saying "alright, alright, alright" without using the trademarked audio mark.

The trademark applications don't protect McConaughey's entire identity. They protect specific commercial representations that are distinctive and recognizable. That's actually smart legal strategy. It avoids overreaching claims that a judge might reject. It targets the most valuable and distinctive elements of his commercial image.

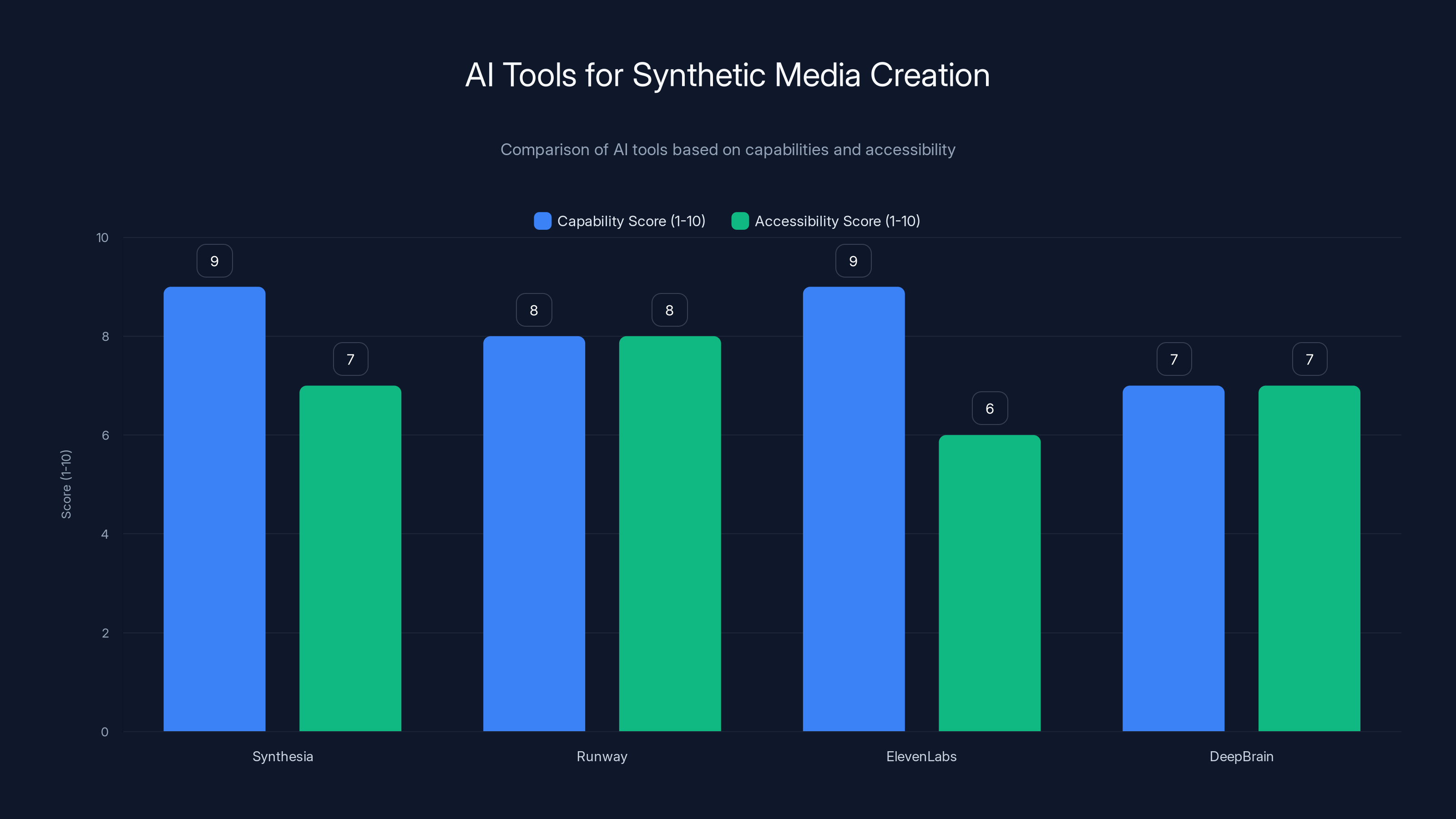

AI tools like Synthesia and ElevenLabs score high in capability, making synthetic media creation accessible and effective. (Estimated data)

The Unknowns: Why This Is a Legal Gamble

Courts Haven't Ruled on AI Synthetic Media Yet

McConaughey's trademark strategy is bold partly because it's unproven. His lawyer, Kevin Yorn, admitted to the Wall Street Journal that they don't actually know how a court would rule if someone challenged the trademarks. This isn't speculation. It's a fundamental uncertainty in how trademark law applies to AI-generated content.

Consider this scenario: An AI marketing company creates a synthetic video of McConaughey endorsing a product. The video looks and sounds like him. But it was created entirely from AI without using any of his original footage. Does that infringe on his trademarked likenesses? Arguably yes, it's using marks that identify him commercially in a way that confuses consumers. Arguably no, the trademark only protects the specific registered mark, not anything that looks like him.

Courts could rule either way. The trademark system was designed to protect specific marks (logos, catchphrases, distinctive designs) from being copied or imitated. It wasn't designed to give someone exclusive rights to their general appearance or voice. So there's a real question about whether a court would interpret McConaughey's registered likenesses as protected marks or as an overreach of trademark law.

Then there's the question of what counts as "use in commerce." Trademark law only protects against use in commerce, not against all uses. If someone creates a deepfake video of McConaughey for entertainment purposes and posts it on social media, are they using his marks in commerce? Only if they're selling something. But what if they're using his likeness to attract viewers so they can sell advertising? Is that commercial use? These questions are genuinely unresolved.

Another uncertainty: international enforcement. McConaughey's trademarks are approved in the United States. But AI companies operating in other countries might not be bound by US trademark law. An AI startup in Singapore could create synthetic McConaughey content and be outside the reach of US courts. Enforcement would require filing in foreign jurisdictions, which is expensive and time-consuming.

McConaughey and his legal team are betting that the threat of a lawsuit will deter most companies from using his likeness without permission. That's probably smart. Most companies will see a registered trademark and decide it's not worth the legal risk. But that means the strategy works through intimidation rather than legal certainty.

The Deepfake Defense: "It's Not Actually You"

One critical vulnerability in the trademark strategy is the deepfake defense. If a company creates synthetic video of McConaughey using AI, they could argue they didn't use his actual likeness. They used an AI model trained on publicly available footage. They used machine learning algorithms. They didn't use any of his registered trademarked marks.

This argument sounds absurd on its face. The video looks like McConaughey. It sounds like McConaughey. Consumers think it's McConaughey. But from a strict legal perspective, a deepfake is a synthetic creation, not a reproduction of the original.

Trademark law protects against using the actual mark. If the argument succeeds, then creating a synthetic version of McConaughey wouldn't technically infringe his trademarks. It would just create something that looks and sounds like him without using any of the registered marks.

This is where likeness law and trademark law conflict. Likeness law would protect against this because the synthetic video still violates the right of publicity. But likeness law is slower and weaker. Trademark law would probably not protect against it if courts accept the deepfake defense.

McConaughey's legal team presumably anticipated this. But they also admitted they don't know how courts would rule. So there's a real possibility that someone could successfully challenge his trademarks by arguing they created synthetic media, not infringing marks.

The Broader Trend: Celebrities Rush to Protect Their Digital Selves

Who's Protecting Their Likeness

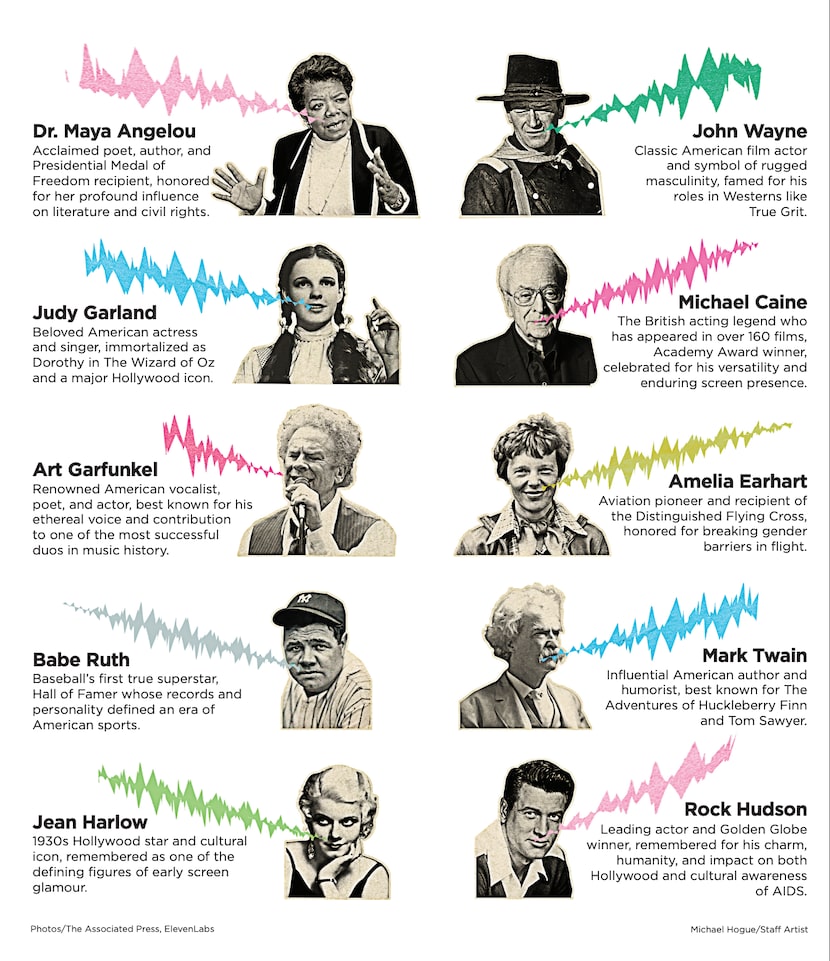

McConaughey isn't alone. The moment it became possible to trademark likenesses for AI protection, other celebrities and public figures started doing the same thing. Actors, musicians, athletes, and influencers with valuable public images all face the same problem: AI companies can now replicate their likeness without permission.

The rush to trademark started after the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike. Union members realized the legal protections they negotiated only covered traditional film and television. Everything else was exposed. Musicians saw AI companies training voice models on their music without permission. Athletes saw deepfakes of themselves endorsing products they'd never agree to. Influencers saw AI companies generating their likenesses for synthetic content.

So they started trademarking. The US Patent and Trademark Office has seen a surge in applications for registered likenesses, voice marks, and distinctive phrases. Some have been approved. Others are pending. A few have been rejected for being too generic or too similar to existing marks.

What's interesting is how different celebrities are choosing different marks to protect. Some focus on distinctive phrases or catchphrases because those are easily trademarked. Others focus on specific gestures or poses that are instantly recognizable. A few are trademarking their entire name as a commercial mark, though that's harder to protect since names are generally considered more informational than distinctive.

The strategy reveals something important about how different celebrities understand their commercial value. McConaughey's "alright, alright, alright" is perfect for trademark because it's instantly distinctive. Someone hearing those words knows exactly who said them. Other celebrities don't have such clear distinctive marks, so they have to be more creative.

The Arms Race: Trademark vs. AI Innovation

Here's the uncomfortable dynamic: as celebrities trademark their likenesses, AI companies are actively working to create synthetic media that doesn't infringe on those marks. They're training models on public footage but making sure not to use the specific registered marks. They're generating variations of people's likenesses that look similar but aren't technically the registered trademarked version.

It's an arms race. Celebrities lock down their distinctive marks. AI companies find workarounds. Celebrities patent new marks. AI companies develop new techniques to generate synthetic media that falls outside those marks.

This is exactly what happened with music and sampling. When musicians started protecting their recordings, producers learned to create new sounds that were inspired by but not directly copying the original. Music evolved because of copyright protection. The same thing might happen with video and audio likenesses.

But there's a difference. With music, the underlying art form (making music) wasn't threatened by copyright protection. Producers could still make music, just not by copying existing recordings. With AI likenesses, the entire point is to replicate people. If trademark protection prevents replication, it could severely constrain the technology.

That's the tension at the core of this issue. Celebrities have legitimate rights to control their image and profit from their likeness. But AI companies have legitimate interests in developing technology that can generate synthetic media. Right now, those interests are in direct conflict.

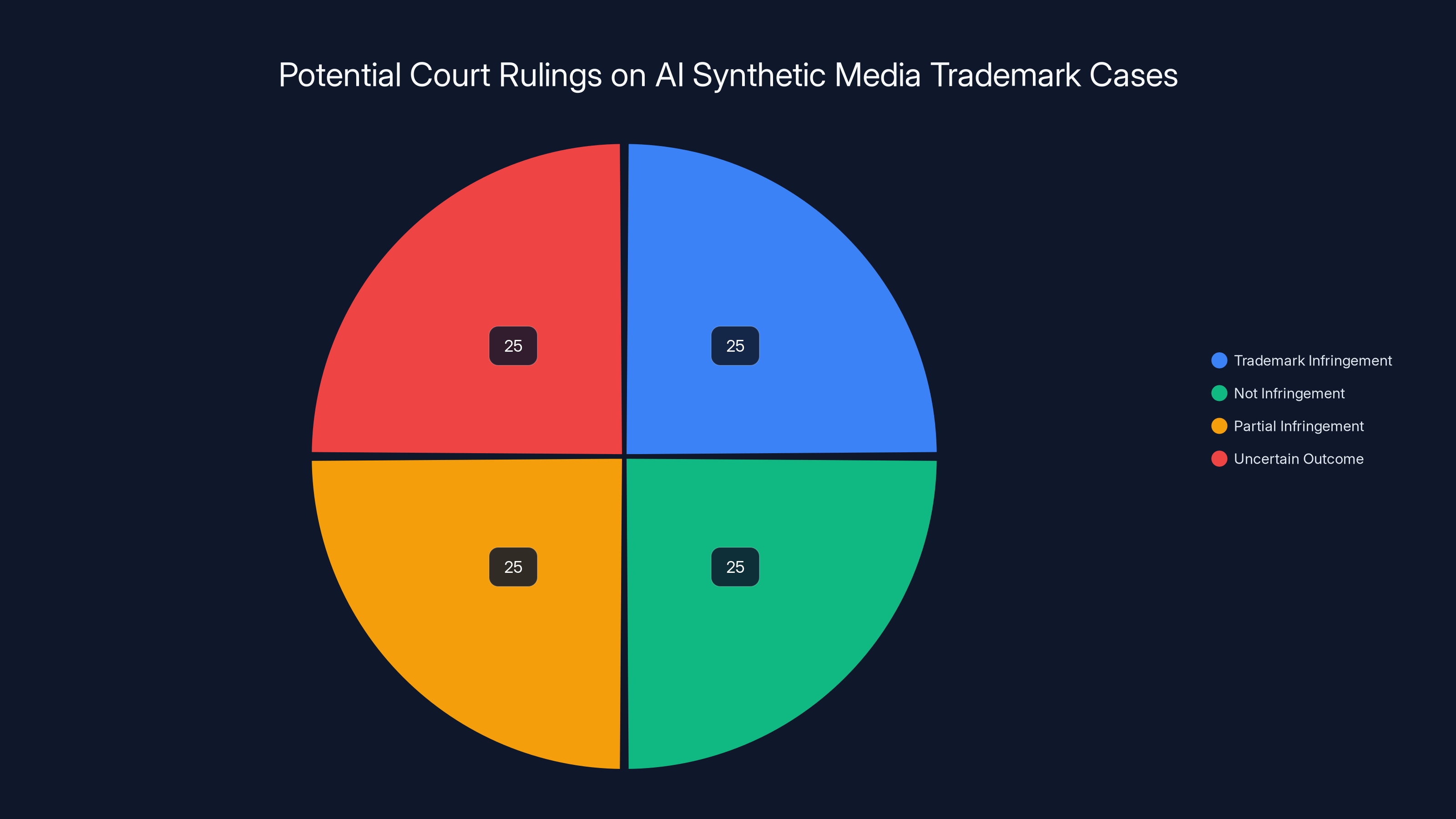

Estimated data suggests an equal distribution of potential court rulings on AI-generated likenesses, highlighting the uncertainty in current trademark law.

The Technology Layer: How Synthetic Media Actually Works

What AI Can Do (Spoiler: Almost Everything)

To understand why McConaughey's trademark protection is necessary, you need to understand what modern AI can actually do. The technology has evolved rapidly in the past three years. What required a team of visual effects artists five years ago now takes a single person with a laptop.

Video synthesis: Tools like Synthesia, D-ID, and Runway can take a photo of a person and a script of text, then generate a video of that person speaking the text with perfect lip sync, natural expression, and appropriate hand gestures. The output looks realistic enough to fool most people. The technology works better with more training data, but even a short video or photo set can generate convincing output.

Voice cloning: Eleven Labs, Descript, and other tools can clone someone's voice from a few minutes of audio. Once cloned, you can generate that voice saying anything. The results are creepy accurate. Most people can't distinguish between the real voice and the cloned version, especially if there's background audio or music.

Deepfakes: The original technology that spawned all this controversy. Deepfakes use machine learning to swap someone's face onto a video of another person. The results are improving constantly. What looked obviously fake two years ago now looks pretty realistic, especially to viewers who aren't looking closely.

Expression transfer: AI can analyze your facial expressions in one video and apply them to another person in another video. This lets someone else express emotions and gestures exactly like you.

Body synthesis: AI can generate synthetic video of someone's entire body, not just their face. This is useful for creating training content, marketing videos, or any scenario where you need video of a specific person doing specific things.

All of these technologies are becoming cheaper and more accessible. A year ago, you needed a small production budget to create convincing synthetic media. Today, the tools cost money but are within reach of any company with a decent marketing budget. In another year, they might be cheap enough that individual creators can use them.

The Quality Threshold: When Deepfakes Become Indistinguishable

There's a critical threshold in synthetic media technology: the point at which AI-generated content is indistinguishable from real content to average viewers. We're approaching that threshold but haven't quite crossed it yet. Most synthetic video still has some artifacts. Skin texture might be slightly off. Eye contact might seem unnatural. Lip sync might be slightly delayed.

But these artifacts are getting smaller every month. In 2024, you could spot a deepfake by looking for weird skin tone transitions or unnatural eye movements. In 2025, many synthetic videos pass casual inspection. And by 2026 or 2027, the technology might be indistinguishable from real video for most purposes.

That threshold matters because it determines when synthetic media becomes a serious threat to celebrity likenesses. Right now, people can look at a deepfake and say "that's not really Matthew McConaughey." But in a couple years, they might not be able to tell. At that point, synthetic media of celebrities becomes functionally identical to real footage.

McConaughey's trademark protection makes sense partly because he's racing against that threshold. He's building legal barriers before the technology becomes so good that people can't tell what's real anymore. Once that happens, the problem becomes exponentially harder to solve.

Legal Gaps: Where Existing Laws Fail

Right of Publicity vs. Copyright vs. Trademark

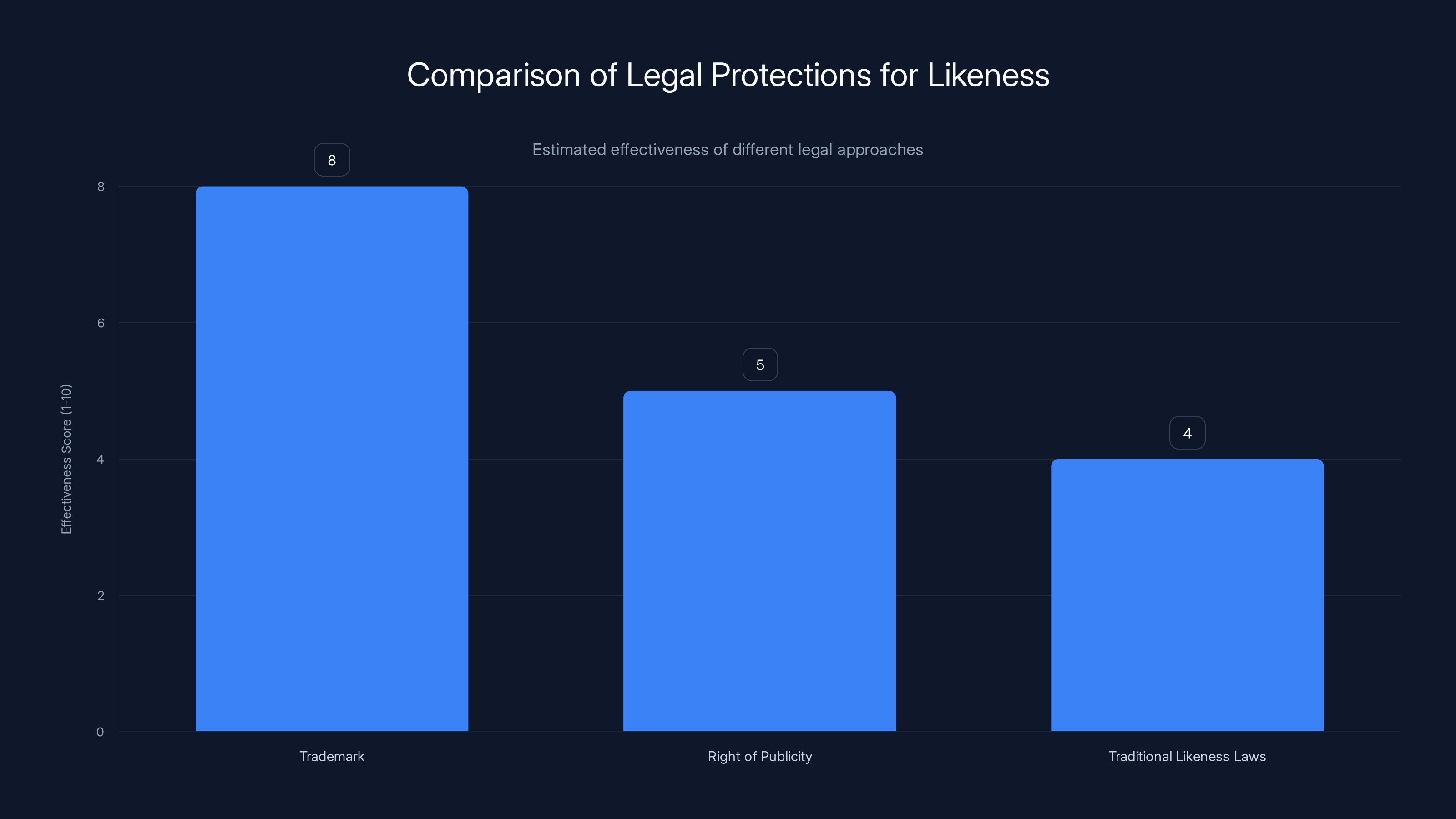

The frustrating reality is that celebrities' rights are protected by three different legal frameworks, and none of them are perfect for AI synthetic media.

Right of Publicity: This protects your ability to profit from your own identity. It prevents companies from using your face or voice to sell products without permission. It's strong protection, but it only applies to commercial use and only covers actual unauthorized use, not synthetic creation. Courts haven't decided whether synthetic media violates the right of publicity.

Copyright: This protects original creative works. If someone records video of you, the copyright belongs to the creator. You don't automatically own copyright in footage of yourself. This gap is huge. A company can film you, own the footage, and then use it however they want (unless your contract says otherwise). Copyright doesn't help you control synthetic media created from your own footage.

Trademark: This protects distinctive marks that identify commercial source. It's designed for logos and catchphrases, not for general likeness. But it can be adapted to protect distinctive likenesses used commercially. The weakness is that it only protects the specific registered mark, not anything similar or inspired by it.

None of these frameworks perfectly protects against AI synthetic media. So celebrities have to use all three and hope something works.

The State-by-State Problem

Here's another mess: the right of publicity varies by state. Some states have strong right of publicity laws. Others have virtually none. California, New York, and a few other major entertainment hubs have well-developed right of publicity protections. Most other states have minimal protection or no protection at all.

This creates perverse incentives. If you're a company wanting to create synthetic media of celebrities, you just set up operations in a state with weak right of publicity laws. Your legal risk drops dramatically.

Similarly, if you're a celebrity, you have to file legal claims in multiple states to get full protection. McConaughey's trademark protection in federal court solves this problem because trademarks are federal. That's actually another reason why the trademark strategy makes sense. It gives him nationwide protection regardless of state law.

But it also highlights how broken the legal system is. We have fifty different states with different rules about who owns their own likeness and how they can protect it. For a technology like AI that operates nationwide and internationally, that's ridiculous.

Trademark law offers a more consistent and effective protection for likeness in commercial use compared to right of publicity and traditional likeness laws. Estimated data.

The Business Model Problem: How Do Companies Profit from AI Likenesses?

Why Companies Want to Use Celebrity Likenesses

Understanding the business incentives helps explain why this is such a big problem. There are several profitable reasons why companies want to create synthetic media of celebrities without permission.

Advertising: The most obvious use case. Imagine a company could hire Matthew McConaughey for an ad without actually hiring Matthew McConaughey. No salary negotiations. No scheduling conflicts. No demands for approval of the final product. They could create synthetic video of him endorsing their product exactly how they want it. The cost savings are enormous. A high-profile celebrity endorsement might cost $1-5 million. Synthetic media could cost a few thousand dollars.

Content creation: Media companies could create new content featuring celebrities without licensing their performances. Imagine a streaming service could generate new episodes of a show featuring a specific actor without that actor doing any work. The financial incentives are massive.

Music industry: Artists could see their voice cloned and used on songs they never recorded. A producer could create a Drake song using AI-generated Drake vocals, potentially reaching millions of listeners and generating millions of dollars in streams.

Marketing and Tik Tok: Influencers and content creators could see their likenesses used to create viral videos they never made. Someone could impersonate them to gain followers, which they could then monetize.

Training data: AI companies could use celebrity likenesses as training data to improve their models, with or without permission.

The financial incentives are enormous. That's why this is such a serious problem. It's not about a few bad actors trying to create deepfakes for fun. It's about legitimate businesses realizing they can save millions of dollars by using synthetic media instead of hiring the real person.

The Counterfeit Celebrity Economy

One specific threat is what we might call the counterfeit celebrity economy. Imagine a company creates synthetic videos of Matthew McConaughey doing an entire commercial campaign. The videos look perfect. Consumers have no idea they're synthetic. The company pays McConaughey nothing. McConaughey gets no control over his image.

This is functionally identical to counterfeiting. A counterfeiter creates fake Rolex watches. A company creating synthetic celebrity endorsements is creating fake celebrity endorsements. The economics are similar: lower cost, higher profit margin, consumer deception.

But counterfeiting Rolex watches is illegal. Creating synthetic celebrity endorsements is... unclear. The company isn't violating trademark law if they're not using a registered mark. They might be violating right of publicity laws, but that depends on state law and requires a lawsuit. They might not be violating copyright law at all because they're not copying copyrighted footage.

This is the legal gap that McConaughey's trademark strategy is trying to bridge. By trademarking his distinctive likenesses, he's creating a legal framework that treats synthetic celebrity endorsements more like trademark counterfeiting. It's not a perfect solution, but it's better than the ambiguous situation that existed before.

Who Else Is Protecting Their Likeness: Case Studies

Athletes Leading the Way

Athletes have been faster to protect their likenesses than actors in many cases. Why? Because the business model for athlete likenesses is clearer and more threatening. A company can create synthetic video of Tom Brady endorsing a product. They can use his likeness in a video game without paying him. They can deepfake him into a commercial.

Some major athletes started filing trademark applications for their names, slogans, and distinctive gestures. Others pursued right of publicity protections at the state level. A few hired tech companies to monitor the internet for unauthorized synthetic media.

The problem for athletes is that trademark and right of publicity protections have limits. An athlete's name or image is valuable partly because it's not distinctive in the trademark sense. Tom Brady is valuable because he's a famous quarterback, not because he has a unique catchphrase or gesture. So trademark protection is harder to get.

But athletes have been more aggressive about pursuing right of publicity claims and cease-and-desist letters. Some have successfully shut down AI companies creating deepfakes. Others have negotiated licensing deals where AI companies pay for the right to use their likeness.

Musicians and Voice Cloning

Musicians face a specific threat from voice cloning. An artist's voice is their most distinctive characteristic. Voice cloning technology makes it possible to generate new songs in someone's voice without their participation.

Some musicians have started trademarking their distinctive vocal characteristics: specific vibrato patterns, signature ad-libs, unique pronunciation quirks. Others have pursued copyright claims against companies that clone their voices without permission.

Drake, Grimes, and other artists have been targets of AI voice cloning. Some have sued. Others have accepted it as inevitable. The legal situation is still unsettled, partly because copyright law is also ambiguous about synthetic versions of copyrighted performances.

Influencers and the Long Tail

While major celebrities get attention, micro-influencers and content creators are also being harmed by synthetic media. An influencer's entire business model is based on their distinctive personality and appearance. If an AI company can clone that and use it to create content without permission, the influencer's unique value disappears.

Some platforms like Tik Tok and Instagram have started implementing policies against synthetic media of real people. But enforcement is difficult because the technology is improving faster than detection.

Runable excels in document automation and presentation creation, making it a valuable tool for managing digital assets efficiently. Estimated data based on typical feature effectiveness.

The Counterargument: Why AI Companies Say This Is Unfair

The Training Data Problem

AI companies argue that creating synthetic media models requires training data, and most of that training data includes celebrities' public footage. Should celebrities be able to block companies from using their own publicly available footage as training data?

From a technology perspective, this is tricky. An AI company might scrape millions of hours of public video from YouTube, TikTok, and other sources to train their model. That footage includes celebrities but also millions of regular people. Should celebrities have special rights to block training data that includes them?

The argument against: it's unfair to give special protection to celebrities' public footage while regular people's footage is used for free. If celebrities can block training data, then so should everyone else. But then you can't train AI models at all, which might mean blocking development of synthetic media technology entirely.

The argument for: celebrities have valuable likenesses that companies want to monetize. There's a difference between someone's footage being used for training (which is less harmful) and someone's synthetic likeness being used to create fake endorsements (which is very harmful). You can protect against the second while allowing the first.

The Fair Use Argument

AI companies also argue that training machine learning models should be protected as fair use. Just like researchers can study copyrighted works for research purposes, AI companies should be able to use copyrighted footage to train models.

Courts haven't fully settled this question, but the trend is toward protecting AI training as fair use under limited circumstances. This would allow AI companies to scrape public footage, including footage of celebrities, as training data without permission.

But training data and synthetic generation are different. You could allow training on public footage while still restricting the commercial use of synthetic media generated from that training. That's the balance that makes sense to most people.

The Innovation Argument

AI companies argue that overly restrictive protections will stifle innovation. If celebrities can block any commercial use of synthetic media that involves their likeness, then entire categories of AI tools become impossible to develop.

This is a legitimate concern. Overly broad protections could prevent useful applications of synthetic media technology. There might be valuable uses (like creating historical documentaries with synthetic performances, or helping disabled people communicate with synthesized voices) that get blocked if celebrities have absolute rights to their likenesses.

But this argument is also used to dismiss legitimate concerns about deepfakes and synthetic media misuse. Just because a technology has some legitimate uses doesn't mean it should be unregulated.

The Legislative Landscape: What Lawmakers Are Actually Doing

Federal Action (or Lack Thereof)

Congress has been mostly absent from this conversation. There's no federal law specifically protecting against deepfakes or synthetic media of celebrities. There's no federal right of publicity law. The US Patent and Trademark Office approved McConaughey's applications under existing trademark law, not under any new AI-specific legislation.

This gap is partly intentional. Lawmakers are hesitant to pass laws regulating AI without understanding the full implications. They're worried about stifling innovation. They're also concerned about free speech implications. If you make deepfakes illegal, are you violating free speech? Courts might say yes.

So federal legislation is moving slowly. There's the Synthetic Age Bill and other proposals, but nothing has passed that specifically addresses celebrity likeness protection and AI synthetic media.

State-Level Efforts

Some states have been more proactive. California, with its strong entertainment industry, has been exploring laws protecting against deepfake synthetic media. Other states have passed or are considering laws against nonconsensual deepfake pornography.

But these state laws are piecemeal and inconsistent. What's illegal in California might be legal in Texas. What's protected in New York might be exposed in Florida. This creates the same problem that state-by-state right of publicity laws create: incomplete protection.

Lawmakers also face a timing problem. By the time legislation passes, the technology has evolved beyond what the law anticipated. Laws written in 2025 might be obsolete by 2027.

International Fragmentation

There's also international fragmentation. Different countries have different laws about synthetic media, deepfakes, and likeness protection. The EU has stricter privacy and likeness laws than the US. China has different rules. India has different rules.

McConaughey's trademark protection is primarily effective in the United States. An AI company operating in another country might not be bound by US trademark law. This creates a situation where companies can offshore their synthetic media generation to avoid legal consequences.

The Future: What Happens Next?

The Test Case Question

McConaughey's trademarks are essentially waiting to be tested in court. At some point, an AI company will probably use synthetic media of him in a way that seems to infringe on his registered trademarks. If they do, it'll likely lead to a lawsuit. That lawsuit will establish how trademark law actually applies to AI synthetic media.

The outcome of that lawsuit will matter enormously. If courts rule that synthetic media doesn't infringe on likeness trademarks (because it's not actually using the registered mark), then trademark protection becomes much weaker. If courts rule that creating synthetic versions of trademarked likenesses is infringement, then trademark protection becomes very strong and other celebrities will rush to register.

Either way, there will be a precedent that shapes how AI companies operate and how celebrities protect themselves.

The Technology Arms Race

As celebrities lock down their trademarks, AI companies will develop workarounds. They'll create synthetic media that looks similar but isn't technically infringing. They'll use lookalikes instead of direct replications. They'll focus on less famous people who haven't trademarked their likenesses.

The result will probably be a world where AI synthetic media is everywhere, but direct replications of trademarked celebrity likenesses become illegal or at least legally risky. Companies will adapt by using synthetic actors who look like celebrities but aren't them.

The Licensing Market

One positive outcome could be the emergence of a legitimate licensing market for AI synthetic media. Celebrities could license companies to use their likeness in synthetic media. This would create a new revenue stream for celebrities while giving AI companies legal cover to use likenesses they've licensed.

Some companies are already exploring this model. They're negotiating with celebrities and talent agents to get permission to include their likenesses in AI tools. If this market grows, it could become a significant part of entertainment industry revenue.

The Regulatory Inevitability

Eventually, governments will have to regulate AI synthetic media more directly. The question is what form that regulation will take. It could be laws against nonconsensual deepfakes. It could be laws requiring disclosure when synthetic media is used in commercial contexts. It could be laws protecting against synthetic media in certain sensitive contexts (elections, court testimony, etc.).

McConaughey's trademark strategy is a stopgap. It works for now. But eventually, the legal system will develop more comprehensive rules for AI synthetic media. When that happens, trademark protection might become obsolete or might be supplemented by more specific synthetic media laws.

Expert Perspective: What Do Lawyers Actually Think About This?

The legal community is divided on McConaughey's approach. Some intellectual property lawyers think it's clever strategy that other celebrities should copy. Others think it's an overreach of trademark law and won't hold up if challenged.

Kevin Yorn, McConaughey's lawyer, is clearly a believer in the strategy. But he's also honest about its limits. He told the Wall Street Journal they don't know how courts would rule if challenged. That's realistic.

Other IP lawyers have pointed out that trademark protection works best for distinctive marks, not for general likenesses. McConaughey's catchphrase is easy to protect. His general image is harder. So the strategy is stronger for some elements of his likeness than others.

There's also disagreement about whether trademark law should be stretched to cover AI synthetic media. Some argue it's a creative solution to a real problem. Others argue it's distorting trademark law beyond its intended purpose and that synthetic media should be addressed through right of publicity law or new legislation, not trademark.

Practical Steps: What Celebrities Should Do Now

The Trademark Strategy

Based on McConaughey's approach, here's what a celebrity with a valuable public image should do:

-

Identify distinctive marks: What makes your image distinctive? Is it a catchphrase? A signature gesture? A specific look? Your voice? Focus on the most distinctive elements of your image.

-

File trademark applications: Work with an intellectual property lawyer to file trademark applications for your distinctive marks. Be specific (trademark particular videos or audio recordings), not generic (don't try to trademark "my face").

-

Maintain continuous use: Trademark law requires continuous use. Keep using your distinctive marks in commerce. Don't let them go unused or they might be abandoned.

-

Monitor infringement: Once trademarked, actively monitor for use of your marks. Set up alerts. Subscribe to AI monitoring services. Watch for deepfakes and synthetic media.

-

Enforce aggressively: When you find infringement, send cease-and-desist letters. File DMCA takedown notices. Be willing to sue if necessary. The value of the trademark depends on enforcement.

The Licensing Approach

Parallel to trademark protection, celebrities should consider licensing their likenesses to AI companies. This creates revenue and gives them control over how their image is used.

-

Create a licensing agreement: Define what companies can do with your likeness, how they can use it, and what you'll be paid.

-

Negotiate exclusivity: Do you want exclusivity (only one company can use your likeness for AI synthesis) or non-exclusive (multiple companies can license it)? Exclusivity commands higher prices.

-

Set usage limits: Can they use your likeness in advertising? Entertainment content? Both? Educational content? Each has different value.

-

Include approval rights: Do you get to approve how your likeness is used? Some celebrities will insist on this. Others will accept a higher price in exchange for less control.

The Cease-and-Desist Approach

Immediately, celebrities should:

-

Hire monitoring services: Companies like Notchmeister and others monitor the internet for unauthorized use of your image and send takedown notices.

-

Build relationships with platforms: Work with social media platforms to set up rapid response to deepfakes and synthetic media.

-

Document everything: If you find synthetic media of yourself, save it, document it, and build a record. This helps prove damages if you need to sue.

The Broader Implications: Society, Ethics, and Trust

The Crisis of Epistemic Trust

One of the most concerning implications of synthetic media is what philosophers call the epistemic trust crisis. If you can't tell what's real and what's synthetic, how do you know what to believe?

McConaughey's trademark protection is partly about protecting his economic interests (stopping unauthorized commercial use of his image). But it's also about protecting something deeper: the ability of society to trust that video and audio evidence is real.

If synthetic media of celebrities becomes common and indistinguishable from real footage, it undermines social trust. People stop believing video evidence. They stop trusting news reports that include video. They become more skeptical of everything they see online.

This has implications far beyond celebrity endorsements. It affects elections, courts, and public discourse. If deepfakes of politicians become common, how do voters know what's real? If synthetic testimony is indistinguishable from real testimony, how do courts function?

McConaughey's trademark protection is partly a response to this concern. By restricting who can use his likeness, he's trying to maintain the integrity of video evidence of Matthew McConaughey.

The Power Imbalance

Another concern is the power imbalance between celebrities who can afford trademark protection and everyone else. McConaughey can hire top intellectual property lawyers. He can afford to sue companies that infringe. He can constantly monitor for unauthorized use.

Most people can't do any of that. Most people have no ability to protect their likeness from synthetic media. They're exposed to deepfakes, voice cloning, and identity theft while celebrities get legal protection.

This creates a two-tier system where the powerful get protection and the vulnerable don't. It's arguably unfair, but it's the logical consequence of making trademark protection the primary defense against synthetic media.

The Free Speech Tension

There's also an underlying tension between protecting likeness and protecting free speech. If you make synthetic media of people illegal, you're restricting what people can create and express. That raises free speech concerns, especially in the US where free speech protections are quite strong.

Some synthetic media is legitimate expression: political satire, artistic commentary, historical recreation. Making all synthetic media illegal would be an overreach. But making it legal enables bad actors to create harmful deepfakes.

Trademark law tries to navigate this by only protecting commercial uses. You can create synthetic media for noncommercial purposes. You just can't use it to make money or sell products. That's a reasonable compromise, though it's not perfect.

The Integration Question: How Do We Solve This Properly?

Ultimately, McConaughey's trademark strategy is a Band-Aid on a deeper problem. The real solution requires integration of several approaches:

Legal clarity: We need laws that specifically address synthetic media and AI-generated likenesses. Current laws are ambiguous and incomplete. New legislation should clarify what's allowed and what's not.

Technology solutions: We also need technological solutions. Watermarking, digital signatures, and other technologies can help identify synthetic media. Platforms can use detection algorithms to flag deepfakes and synthetic content.

Industry standards: The AI and entertainment industries need to establish standards for how synthetic media can be used, what permissions are required, and how compensation works.

Education: People need to understand synthetic media is possible and learn how to identify it. Media literacy becomes critical.

Enforcement: Whoever makes the rules needs to enforce them. That means platforms removing deepfakes, courts ruling on synthetic media cases, and regulators monitoring for violations.

McConaughey's trademark protection addresses only the legal clarity part and only for celebrities wealthy enough to hire lawyers and file applications. It's not a complete solution.

But it's the best tool available right now, which says something about how underprepared we are for the synthetic media age.

Conclusion: The Matthew McConaughey Template

Matthew McConaughey trademarked himself not because he's paranoid but because the legal system failed to protect his likeness adequately. Existing laws were written for a different era. Trademark law was designed for logos and catchphrases, not likenesses. Right of publicity law varies by state and is slow and expensive to enforce. Copyright law doesn't protect people from their own publicly available footage being used without permission.

So McConaughey and his legal team improvised. They took trademark law, a tool designed for something completely different, and repurposed it as a shield against synthetic media. It might work. It might not. But right now, it's the best option available.

The approval of his eight trademark applications signals something important: the legal system is starting to adapt to synthetic media technology, even if lawmakers haven't officially done anything yet. Trademark examiners at the US Patent and Trademark Office looked at McConaughey's applications and said yes, these are distinctive marks that should be protected.

That opens the door for other celebrities. It establishes a template: identify your distinctive marks, file trademark applications, and you've got legal grounds to sue anyone using those marks without permission.

But the template has limits. It works well for distinctive catchphrases and specific gestures. It works less well for general likeness. It doesn't address the deepfake defense. It doesn't solve the problem of companies creating synthetic media that doesn't technically use the registered mark.

What McConaughey's trademark strategy really represents is the gap between technology and law. Technology (AI synthetic media) is advancing rapidly. Law is advancing slowly. Until law catches up, people with resources will improvise solutions using existing legal frameworks. That's what McConaughey did.

The lesson isn't that trademark law is the right answer. The lesson is that we don't have the right answer yet. We have trademark law, right of publicity law, copyright law, and a patchwork of state regulations. None of them perfectly address synthetic media.

Eventually, lawmakers will recognize this gap and pass legislation specifically designed for AI and synthetic media. That legislation will probably draw on lessons from McConaughey's trademark strategy. But it will also create new rules specific to synthetic media: requirements for disclosure, restrictions on commercial use without consent, possibly a licensing market regulated by law.

In the meantime, McConaughey's trademarked likenesses represent a creative solution to an unsolved problem. Whether the solution actually works remains to be seen. But at least he's trying. At least he's not waiting for a court to decide his rights. He's taking the tools available to him and adapting them to a new threat.

That's what intellectual property law is really about: giving people the tools to protect what's valuable to them. McConaughey's trademark protection is imperfect, but it's better than nothing. And in the absence of better legal frameworks, it might become the standard that other celebrities follow.

Alright, alright, alright—the future of celebrity likeness protection might just come down to trademarking yourself.

FAQ

What is a trademark, and how does it apply to likeness protection?

A trademark is a registered mark (image, word, phrase, sound, or distinctive design) that identifies your commercial source and prevents others from using confusingly similar marks. McConaughey trademarked specific videos and audio recordings of himself, turning his distinctive likenesses into protected commercial marks. If someone uses a similar mark without permission in a commercial context, they're technically infringing the trademark, which is faster to address than traditional likeness theft claims. Trademark law doesn't care how the mark is created or replicated—just that it's used without authorization.

How does AI synthetic media differ from traditional likeness theft?

Traditional likeness theft involves using someone's actual image or voice that was previously recorded or created. Synthetic media is AI-generated content that looks and sounds like a person but was never actually recorded by them. The legal distinction matters because traditional likeness laws assume someone used your "actual" likeness, whereas synthetic media creates something new that merely resembles you. This gap is why McConaughey's trademark strategy targets specific likenesses rather than relying solely on traditional likeness laws, which haven't been tested thoroughly in court for synthetic media scenarios.

Why didn't Matthew McConaughey use right of publicity laws instead of trademarking?

Right of publicity laws exist in most states but vary significantly in strength and scope. State-by-state variation means someone could use McConaughey's likeness in a state with weak protection without consequence. Trademark law, by contrast, is federal and consistent nationwide. Also, right of publicity lawsuits are slow and require proving financial harm or intent to damage reputation. Trademark infringement is simpler: if someone uses your protected mark in commerce without permission, they're infringing, regardless of intent or damage. McConaughey's legal team likely chose trademark because it's faster, stronger, and more predictable than state-by-state right of publicity claims.

What are the limitations of trademarking your likeness for AI protection?

Trademark protection only covers the specific registered marks, not your general likeness. McConaughey trademarked eight specific things (videos of him staring, his "alright, alright, alright" phrase, etc.), but someone could potentially create synthetic video of him saying something different without technically infringing the trademark. Additionally, trademark only protects against commercial use. If someone creates a deepfake of McConaughey for entertainment purposes with no commercial intent, trademark law might not apply. Finally, the strategy is completely untested in courts—we don't actually know how judges will rule if someone challenges the trademarks and argues they created synthetic media, not infringing marks.

Why did celebrities wait until 2025 to start trademarking their likenesses?

The technology for creating convincing synthetic media only became accessible and affordable in the past few years. Before 2022-2023, deepfakes and voice cloning required significant technical expertise and resources. The 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike also drew major attention to AI threats to celebrity likenesses, encouraging legal action. Additionally, the US Patent and Trademark Office only recently started accepting applications for likeness-based trademarks, suggesting the office itself was evolving its policies to accommodate AI-age protection strategies. The timing represents the moment when both technology maturity and legal possibility aligned.

Could AI companies successfully argue that synthetic media doesn't infringe McConaughey's trademarks?

Yes, this is a significant vulnerability in the trademark strategy. AI companies could argue that synthesized video of McConaughey is a new creation, not a reproduction of his registered trademark. They could claim they didn't use his actual likeness marks but instead created synthetic versions from machine learning models. Courts haven't ruled on this distinction yet, so it's genuinely unclear whether trademark law extends to synthetic replications. If courts accept the "deepfake defense"—that AI-generated content isn't technically using the registered mark—then trademark protection becomes much weaker than McConaughey's team hopes.

How will other industries be affected by this trademark precedent?

If McConaughey's trademarks hold up in court, other public figures (athletes, musicians, politicians, influencers) will likely file similar applications. This could accelerate the development of AI tools designed to work around trademarked likenesses. The music industry might see voice cloning restricted. Sports leagues might see stricter rules against synthetic media of athletes. The entertainment industry could develop licensing markets where companies pay for rights to use synthetic likenesses. The broader implication is that trademark law might become the primary tool for likeness protection until comprehensive synthetic media legislation passes.

What happens if McConaughey's trademarks are challenged in court?

When (not if) someone challenges the trademarks—whether through infringement litigation or a TTAB (Trademark Trial and Appeal Board) proceeding—courts will have to decide several important questions: Does trademark law extend to synthetic versions of protected marks? Are AI-generated likenesses considered "use in commerce"? Does trademark protection prevent creating synthetic media that looks like but technically doesn't replicate the registered mark? The outcome will establish precedent for how trademark law applies to AI, likely determining whether this strategy becomes standard or becomes obsolete.

Are there alternative legal strategies celebrities should consider besides trademark?

Yes. Celebrities should pursue multiple approaches: right of publicity lawsuits in states with strong protection, copyright claims for footage created with their participation, licensing agreements allowing AI companies to legally use their likenesses in exchange for compensation, cease-and-desist letters against deepfake creators, and DMCA takedown notices against platforms hosting unauthorized synthetic media. Some are also exploring technology solutions like digital watermarking and synthetic media detection. The most secure approach combines trademark protection (for speed and certainty) with traditional legal tools (for comprehensive coverage) and licensing (for revenue generation).

Final Thoughts on Runable and Workflow Automation

As creative industries grapple with AI-generated content and legal protections, teams need tools that help them manage digital assets responsibly and efficiently. Runable provides AI-powered automation for creating presentations, documents, and reports that keep your team's creative and administrative workflows running smoothly. Whether you're documenting contracts, creating client presentations about licensing rights, or generating reports on synthetic media usage, Runable's automation capabilities help teams focus on strategy rather than repetitive content creation tasks.

Use Case: Automate creation of licensing agreement templates and IP protection documentation to streamline your legal review process.

Try Runable For FreeKey Takeaways

- Matthew McConaughey filed 8 approved trademark applications to protect his likeness from unauthorized AI commercial use, establishing a new legal template for celebrity protection.

- Existing laws (right of publicity, copyright, trademark) are inadequate for synthetic media because courts haven't ruled on whether AI-generated likenesses violate these protections.

- The 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike revealed AI likeness threats but only protected traditional film and TV, leaving advertising, social media, and smaller productions exposed.

- Trademark protection works faster than likeness law but has vulnerabilities: it only protects specific registered marks, requires commercial use, and hasn't been tested against deepfake defenses.

- Courts haven't yet ruled whether trademark law applies to synthetic versions of protected marks, making McConaughey's strategy a legal gamble that will establish important precedent.

Related Articles

- Senate Passes DEFIANCE Act: Deepfake Victims Can Now Sue [2025]

- OpenAI Contractors Uploading Real Work: IP Legal Risks [2025]

- Indonesia Blocks Grok Over Deepfakes: What Happened [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why the Paywall Isn't Working [2025]

- Senate Defiance Act: Holding Creators Liable for Nonconsensual Deepfakes [2025]

- Internet Censorship Hit Half the World in 2025: What It Means [2026]

![Matthew McConaughey Trademarks Himself: The New AI Likeness Battle [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/matthew-mcconaughey-trademarks-himself-the-new-ai-likeness-b/image-1-1768398217683.jpg)