The Moment Celebrity Identity Became Intellectual Property

Matthew McConaughey didn't just say three words in a movie. He created a brand. In 2022, the actor filed a trademark for "Alright, alright, alright"—his iconic catchphrase from "Dazed and Confused." On the surface, it looks like standard celebrity IP protection. You trademark your catchphrase. You control its use. You get paid when someone else wants to use it. According to Variety, this move is part of a broader trend where celebrities are taking steps to protect their identities from AI misuse.

But here's the thing: this trademark filing is a canary in the coal mine for something much bigger.

We're entering an era where the line between a person and their digital representation is blurring faster than most people realize. McConaughey's trademark isn't just protecting words he said on film. It's protecting the essence of Matthew McConaughey—the mannerisms, the vocal patterns, the personality quirks that make him instantly recognizable. And if someone can own those elements, what happens when AI gets good enough to recreate them without the original person's involvement?

That's not hypothetical anymore. It's happening right now.

The entertainment industry is facing its biggest existential threat since the internet itself. Not from streaming platforms or piracy. But from the ability to create convincing digital replicas of celebrities—sometimes without their permission, always without clear legal frameworks governing who owns what. According to Storyboard18, this lack of legal clarity is driving many creators to court to protect their identities.

This isn't just about protecting Matthew McConaughey's three-word catchphrase. It's about whether actors, musicians, and public figures will retain control over their likenesses, voices, and personas in an age where AI can generate them on demand. And the answer, right now, is: nobody really knows.

Why This Trademark Actually Matters

Most people heard about McConaughey's trademark and shrugged. It seemed quaint. A celebrity protecting his catchphrase. Old news.

But trademark law exists in a world that predates deepfakes, voice synthesis, and generative AI. When the Lanham Act was written in 1946, nobody was thinking about synthetic celebrities. The law protects you from unauthorized commercial use of your name, image, or distinctive characteristics. It was designed for physical world problems: someone selling fake Coca-Cola bottles or bootleg concert merchandise.

Now we have entirely new problems.

Consider what happened with Drake and the AI-generated diss track that circulated on social media in 2023. Someone used AI to clone Drake's voice and create a song featuring him alongside The Weeknd. It sounded authentic. Most people couldn't tell it wasn't actually Drake. But Drake never consented to it. He didn't perform it. He didn't profit from it. And legally? The situation was murky as hell.

Underneath that murkiness is a fundamental problem: our legal system hasn't caught up with what's technologically possible.

McConaughey's trademark filing is a defensive move. It's saying: "I own this distinctive characteristic. I get to decide who uses it commercially." But here's the gap: trademark law protects against commercial confusion (selling a fake McConaughey product) but doesn't necessarily protect against someone synthesizing McConaughey's voice for non-commercial purposes, or creating a deepfake for entertainment.

It's like trying to protect your car from being stolen by locking the doors, only to realize thieves now have the ability to teleport the car to another dimension. The lock wasn't designed for that.

Right now, celebrities like McConaughey are doing what they can within existing legal frameworks. But those frameworks are built for a world where creating a convincing replica of someone required millions in production budgets and months of work. Now it requires a laptop and about three hours.

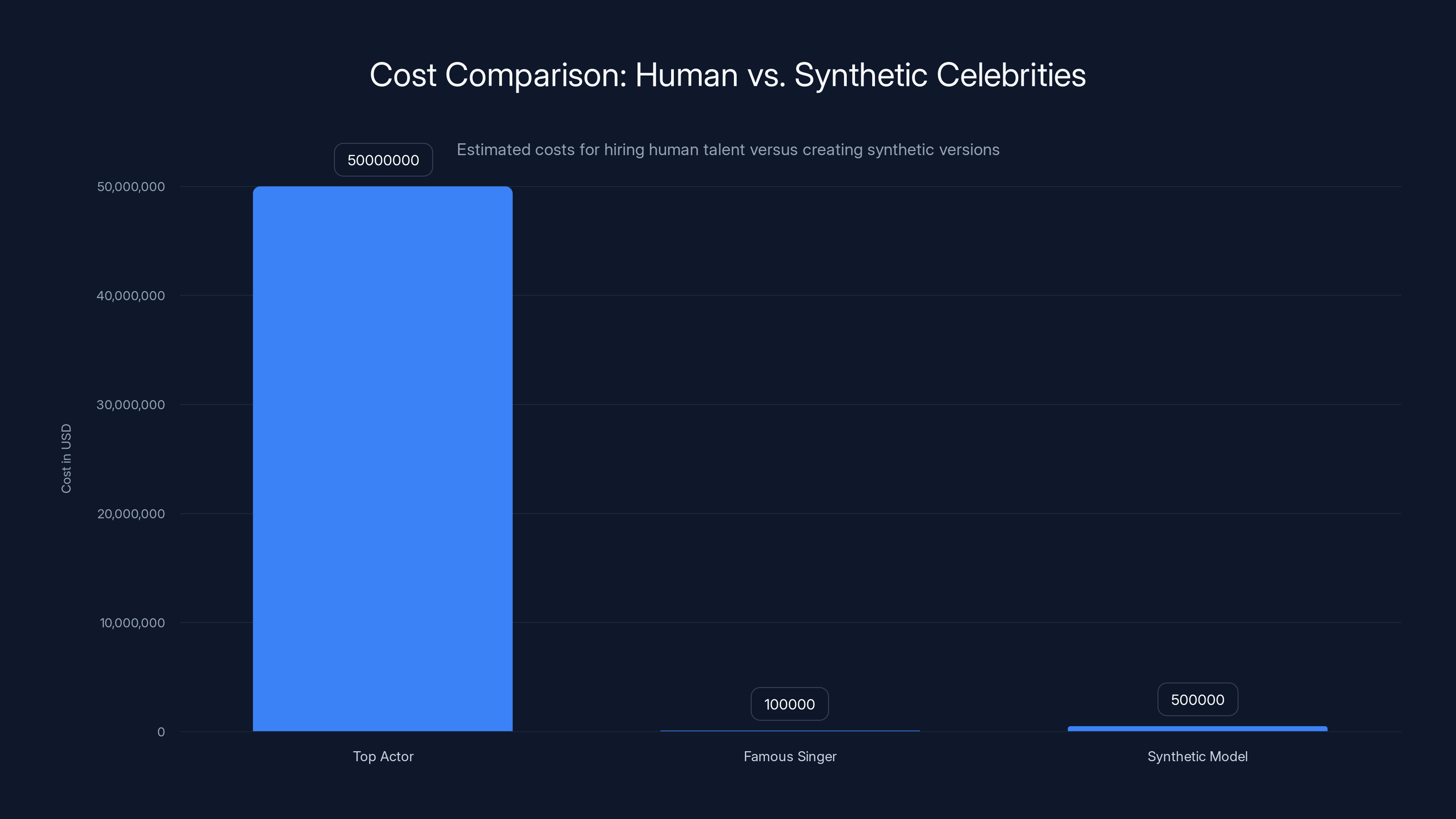

Estimated data shows that synthetic models could drastically reduce costs compared to hiring top-tier human celebrities.

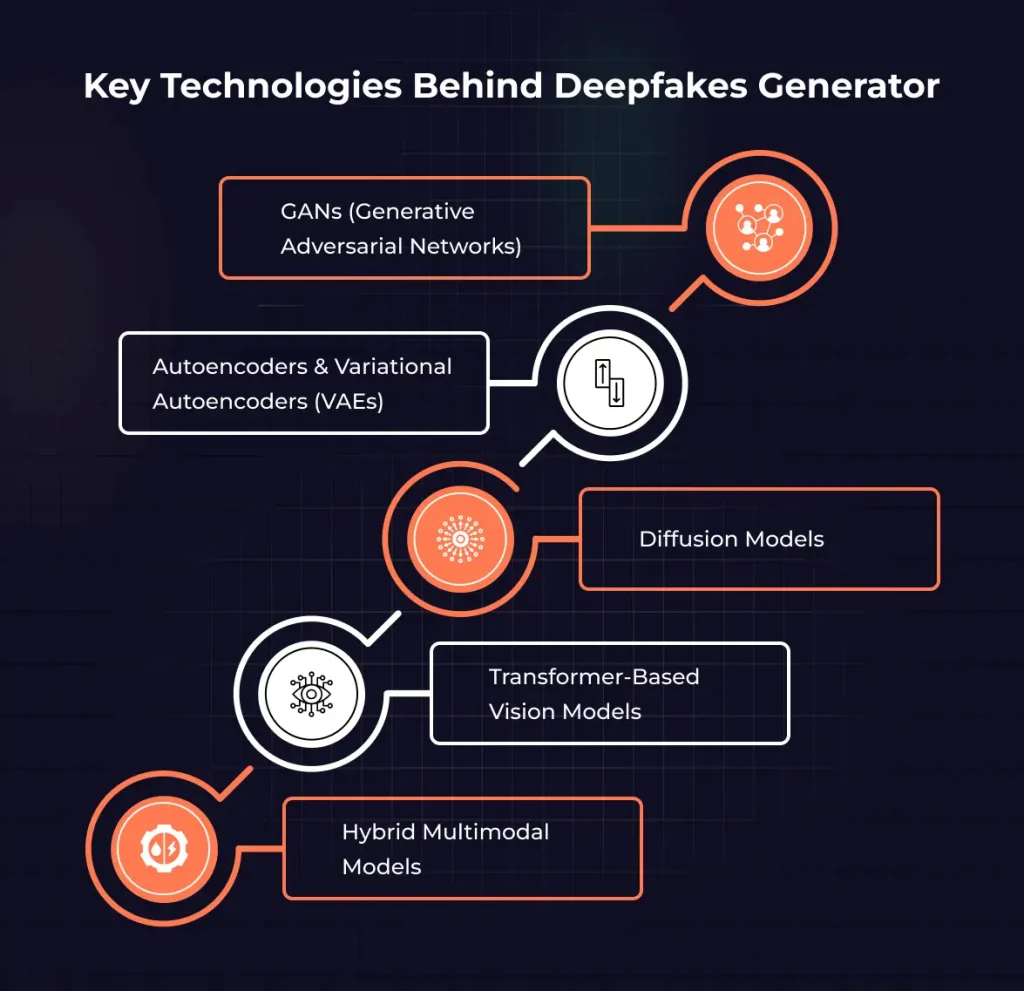

The Deepfake Explosion: What's Actually Possible Right Now

Let's get specific about what AI can do today, because the capabilities are genuinely unsettling.

Voice synthesis has reached a point where it can clone someone's voice from as little as 3-5 minutes of audio. That means someone could take clips of a celebrity from interviews, podcasts, or movies and create a synthetic voice that sounds nearly indistinguishable from the original. Companies like Eleven Labs have created voice cloning tools that are publicly available. The technology isn't perfect, but it's close enough for most casual listeners.

Facial synthesis is more complex because it requires body movement, lighting, and spatial awareness. But it's getting there. Tools like Synthesia and D-ID can create convincing talking heads from still images. More advanced models trained on hours of video footage can generate increasingly realistic facial expressions and body movements.

When you combine these technologies—synthetic voice plus synthetic face plus synthetic body—you can create a digital person who can say and do things the original never did or approved.

Put a synthesized Matthew McConaughey in a commercial for a product he never endorsed. Have a synthetic Tom Cruise give a political speech. Create a fake Beyoncé pop single. The technical barriers are falling.

Some of these experiments have already happened. In 2021, a company created a deepfake of Tom Cruise doing magic tricks on Tik Tok, and it fooled millions of people. It was clearly a technical demonstration, but it proved the point: synthetic celebrities are already here.

The legal question is: who owns the right to create that? Who profits from it? What happens if someone creates a synthetic celebrity endorsement that misleads consumers?

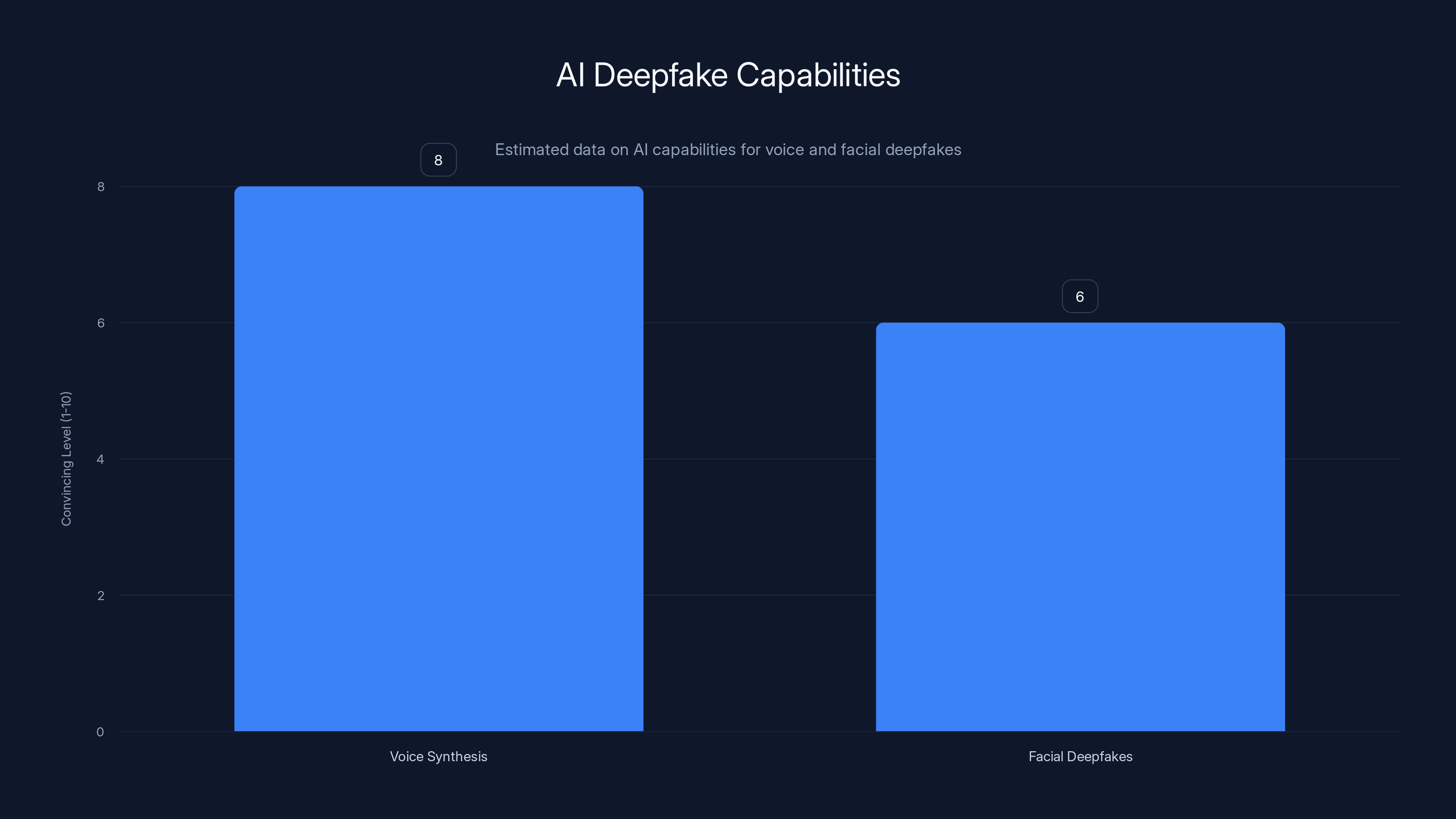

Voice synthesis is currently more convincing than facial deepfakes, with a score of 8 out of 10 compared to 6. Estimated data.

The Voice Rights Crisis: Who Owns Your Acoustic Identity?

Voice is becoming the battleground.

Unlike a face (which requires capturing expressions and micro-movements), a voice can be cloned from relatively short audio samples. And voices appear everywhere: podcasts, interviews, audiobooks, voice acting, singing. That's a lot of training data.

Here's a concrete example: In 2022, a company called Respeecher created a synthetic version of Ukranian actor Roman Lysniak's voice to create war announcements during Russia's invasion of Ukraine. The deepfake was used for a genuinely noble purpose—spreading accurate information during a conflict. But it raised an uncomfortable question: if that voice could be used for good, what stops it from being used for bad?

For musicians, this gets even more complex. Your voice is your primary asset. When a singer records an album, they're not just capturing words—they're capturing their unique vocal characteristics: tone, timbre, vibrato, breath patterns. All of that is trainable now. Someone could theoretically create new music in your voice without your participation.

To make it worse, there's no federal voice rights law in the United States. Some states have right of publicity laws that might cover voice, but it's unclear. A celebrity's voice protection depends on which state they live in, what contracts they've signed, and how courts interpret ambiguous language.

And here's the thing that should keep entertainment executives up at night: voice synthesis is improving faster than facial synthesis. The technology is cheaper, more accessible, and harder to detect.

Some singers have started proactively trademarking their vocals. But trademark is imperfect protection for something as fluid and characteristic as a human voice. You can trademark the phrase "Alright, alright, alright," but how do you trademark your voice itself? How do you prevent someone from synthesizing your voice to say different words?

You can't. Not yet. And that's the problem.

Hollywood's Unpreparedness: The Legal Vacuum

Hollywood has contracts for everything. If you want an actor to appear in a movie, you get a contract. If you want a stunt double, you get a contract. If you want someone to take a shower scene, there's a rider that specifies exact dimensions of coverage and body placement.

But there's no standard contract for "synthetic me." Because until recently, it wasn't possible.

The SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild) strike in 2023 directly addressed this. One of the major negotiation points was whether studios could use AI to replicate actors' faces, voices, and likenesses without consent or additional payment. According to The Skinny, this strike highlighted the growing concerns over AI's impact on the entertainment industry.

They fought hard on this, and they got some protections. The new contract requires explicit consent for digital replicas and mandates extra compensation. But here's the gap: that contract only covers SAG-AFTRA members. Outside that, there's almost nothing.

Smaller actors, voice actors, background extras, social media creators—they're not protected. If a production company wants to create a synthetic version of a non-union actor, there's no contract protecting them. There's no industry standard compensation.

And for non-actors? For musicians, athletes, influencers, or just regular people? There's essentially zero protection. Someone could clone your voice right now and synthesize you saying whatever they want, and you'd have a hard time proving you didn't say it.

This legal vacuum exists because of how fast the technology has developed. Courts move slowly. Legislators move slowly. AI moved incredibly fast. Now we have a technological capability that's years ahead of the legal frameworks meant to govern it.

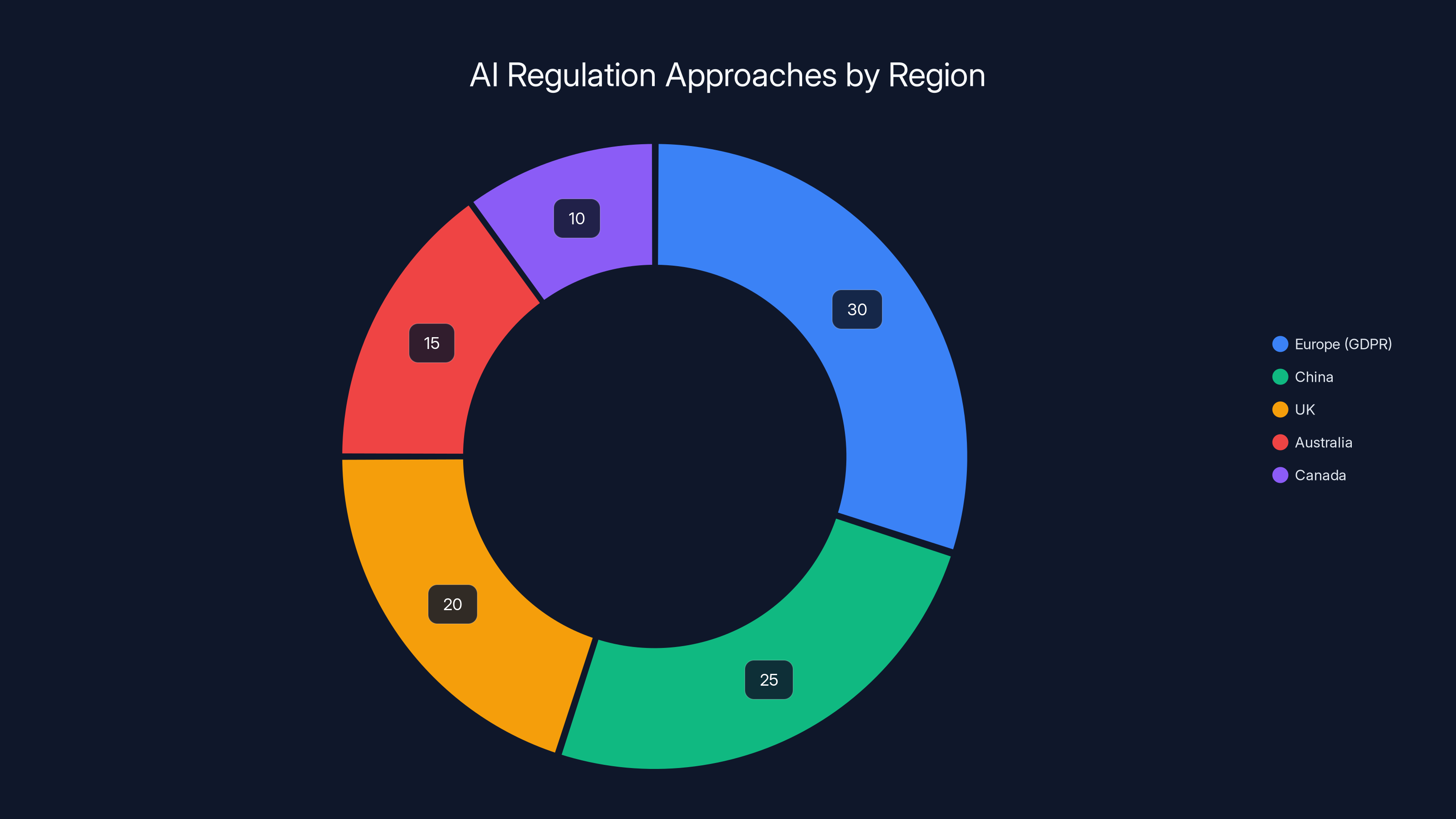

Estimated data shows Europe focusing most on privacy with GDPR, while China emphasizes political control. Other regions like the UK, Australia, and Canada are developing unique frameworks.

The Personality Trademark Problem

McConaughey's trademark on "Alright, alright, alright" works because it's a distinct phrase associated with him. Courts understand that. But what about less tangible characteristics?

Consider someone like Elon Musk. His entire public identity is built on eccentricity, irreverent humor, and distinctive communication style. Could someone trademark "Elon Musk's way of tweeting"? Could they prevent AI from generating content that mimics his voice and mannerisms?

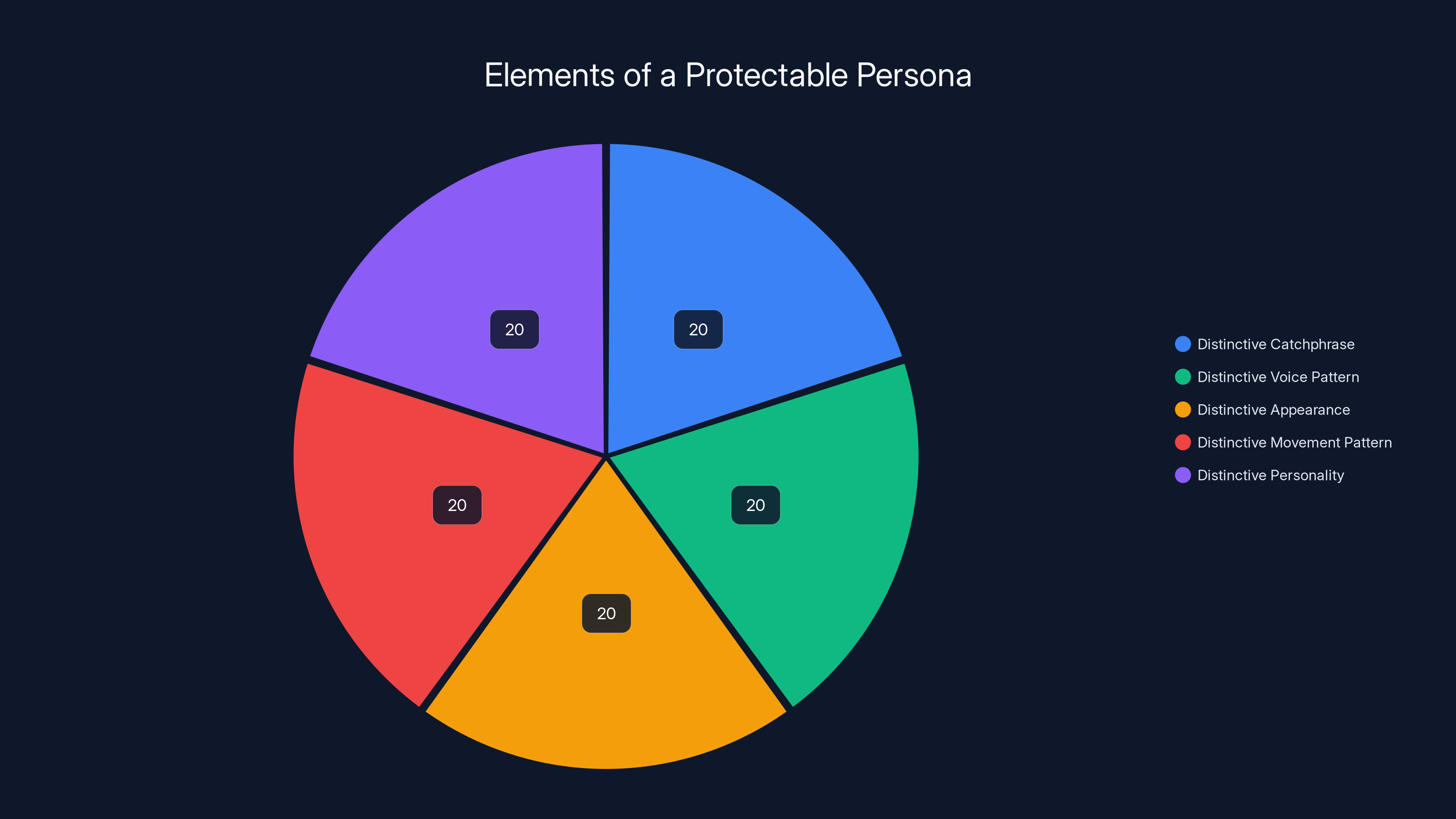

There's also a fundamental question about what constitutes a protectable "persona." Is it:

- A distinctive catchphrase (McConaughey's case)

- A distinctive voice pattern (a singer's unique timbre)

- A distinctive appearance (a celebrity's recognizable features)

- A distinctive movement pattern (someone's walk, gestures, dance moves)

- A distinctive personality (their humor style, communication patterns)

- All of the above?

Most people would say it should be all of the above. But legally proving that someone else is using "your" sense of humor or communication style is nearly impossible. You can't trademark an attitude.

This creates a strange incentive structure. It rewards celebrities who have filed trademarks for specific catchphrases or distinctive elements but leaves everything else unprotected. So if you're famous for a specific way of speaking (like Morgan Freeman's narration voice, or Marilyn Monroe's breathy delivery), you should absolutely be trademarking that now. But if you're just famous for being generally charming or attractive, you're mostly out of luck.

It also creates perverse incentives for studios. If a celebrity's personality is hard to protect legally, studios might see it as fair game to replicate without additional compensation. Why pay Tom Cruise millions to do a commercial if you can synthesize Tom Cruise for a fraction of the cost?

The problem is that this doesn't just affect A-list celebrities. It affects anyone whose likeness or voice has commercial value. And that's becoming increasingly broad as AI gets cheaper and more accessible.

Right of Publicity: The Stronger But Messy Alternative

Right of publicity is a different legal concept from trademark. It protects your right to control the commercial use of your name, image, likeness, and distinctive characteristics. Unlike trademark, which protects consumers from confusion, right of publicity protects the person themselves from unauthorized commercial exploitation.

It sounds like it should handle the deepfake problem perfectly. It should. But there are complications.

First, right of publicity varies dramatically by state. Some states have strong protections. California has one of the best right of publicity statutes in the country. Other states basically don't recognize it at all. This creates the weird situation where you might be protected in California but not in New York, even though both are major entertainment hubs.

Second, right of publicity is built around the assumption that someone is using your actual likeness. A court can see a photo of you and determine that's your image. But what about a synthetic image that looks similar but isn't actually you? Is that "your" likeness, or is it a new creation?

The case law is sparse because this is all so new. But early indications suggest courts might distinguish between "actual likeness" (which is clearly protected) and "synthesized version that resembles you" (which is murkier). If a deepfake doesn't actually use any of your real footage, just AI-generated content that looks like you, does your right of publicity even apply?

Third, right of publicity doesn't necessarily protect non-commercial uses. Someone might create a deepfake for entertainment, parody, or political speech. These might fall under free speech protections even if they violate someone's right of publicity. The courts have to balance two competing rights: your right to control your image versus the public's right to free expression.

This is where things get genuinely complicated. If a political group creates a deepfake of a politician to mock them, is that copyright infringement or protected speech? What if they synthesize a celebrity saying something embarrassing to make a political point?

Right now, there's no clear answer. Courts are going to have to figure this out case by case.

Estimated data showing equal distribution of potential trademark elements in a persona. Each element contributes equally to the concept of a protectable persona.

The Business Incentive Problem: Why Studios Want Synthetic Celebrities

Let's talk about why this matters economically.

A top-tier actor commands enormous fees. Tom Cruise reportedly earned

But a synthetic version? You pay one time for the AI model (maybe

From a pure business perspective, this is wildly attractive. Why would a studio choose to pay a human actor millions of dollars if they could pay once for a synthetic version?

The obvious answer is: because the synthetic version isn't as good. People can tell. There's still an uncanny valley where something looks almost human but not quite, and it triggers a revulsion response.

But "not quite good enough yet" is the key phrase. The technology is improving. Within five years, probably within two years for voice work, the quality gap might close entirely.

When that happens, you're going to see an economic shock in Hollywood.

Extras and background actors could be almost entirely replaced by synthetic humans. Voice acting could become automated. Even lead actors in action films might find themselves getting replaced—their digital likeness doing the stunts and action sequences while they do voice work in a booth.

This isn't theoretical. Studios are already experimenting. Some productions have used AI-generated extras to fill crowd scenes. Voice synthesis is being tested for minor characters. The economic pressure is real and it's pushing in only one direction: toward more AI, less human talent.

Unless there are legal restrictions that make synthetic celebrity use prohibitively expensive or complicated, the incentive structure will push studios toward synthetic talent as soon as the quality is high enough.

And that's where the real conflict lies. It's not about protecting artistic integrity or creative control (though those matter). It's about economic competition. If you're a studio and your competitor can produce content 50% cheaper using synthetic actors, you have to do the same or lose market share.

It's a race to the bottom driven by economic pressure, not by creative vision.

The Consent Crisis: Synthetic You Without Permission

Here's a scenario that should worry you: a production company scrapes thousands of hours of your interviews, podcasts, or videos. They use that footage to train an AI model of your voice. Then they use that model to synthesize lines you never recorded, for a project you never agreed to.

Is that legal? Should it be?

Right now, the answer is: it depends.

If they're using your footage without permission to create a derivative work (synthesized speech), that might violate copyright. But copyright law gets weird with AI training data. Some argue that training AI on public footage is "fair use" similar to how Google can index websites without permission.

If they're using your synthesized voice to trick people into thinking you said something you didn't, that could be defamation or fraud. But proving that your synthesized voice was used deceptively is complicated.

If they're using it for commercial purposes without paying you, that should violate right of publicity. But as mentioned, right of publicity is state-dependent and mostly designed for situations where your actual likeness is being used.

The core problem is that AI makes the concept of "consent" murky. You give consent to appear in a movie. You don't give consent to have your image and voice used to synthesize appearances in other movies. Those should be different legal situations, but the law hasn't caught up to making that distinction.

SAG-AFTRA's new contract addresses this for actors, but it's a union agreement, not a law. Independent creators don't have that protection. Once SAG-AFTRA reaches agreements, other entertainment unions (voice actors, musicians, etc.) will probably push for similar protections. But smaller creators? Random people whose videos go viral?

They're out of luck.

Some states are starting to address this. California passed a law in 2023 banning nonconsensual deepfake sexual imagery. Illinois has had a biometric privacy law (BIPA) for years. But these are narrow protections. They don't cover the general case of someone synthesizing your voice or likeness for other purposes.

We need broader frameworks. But getting those takes years—probably a decade before comprehensive legislation covers deepfakes, voice cloning, and synthetic likeness across the board.

In the meantime, the technology keeps advancing.

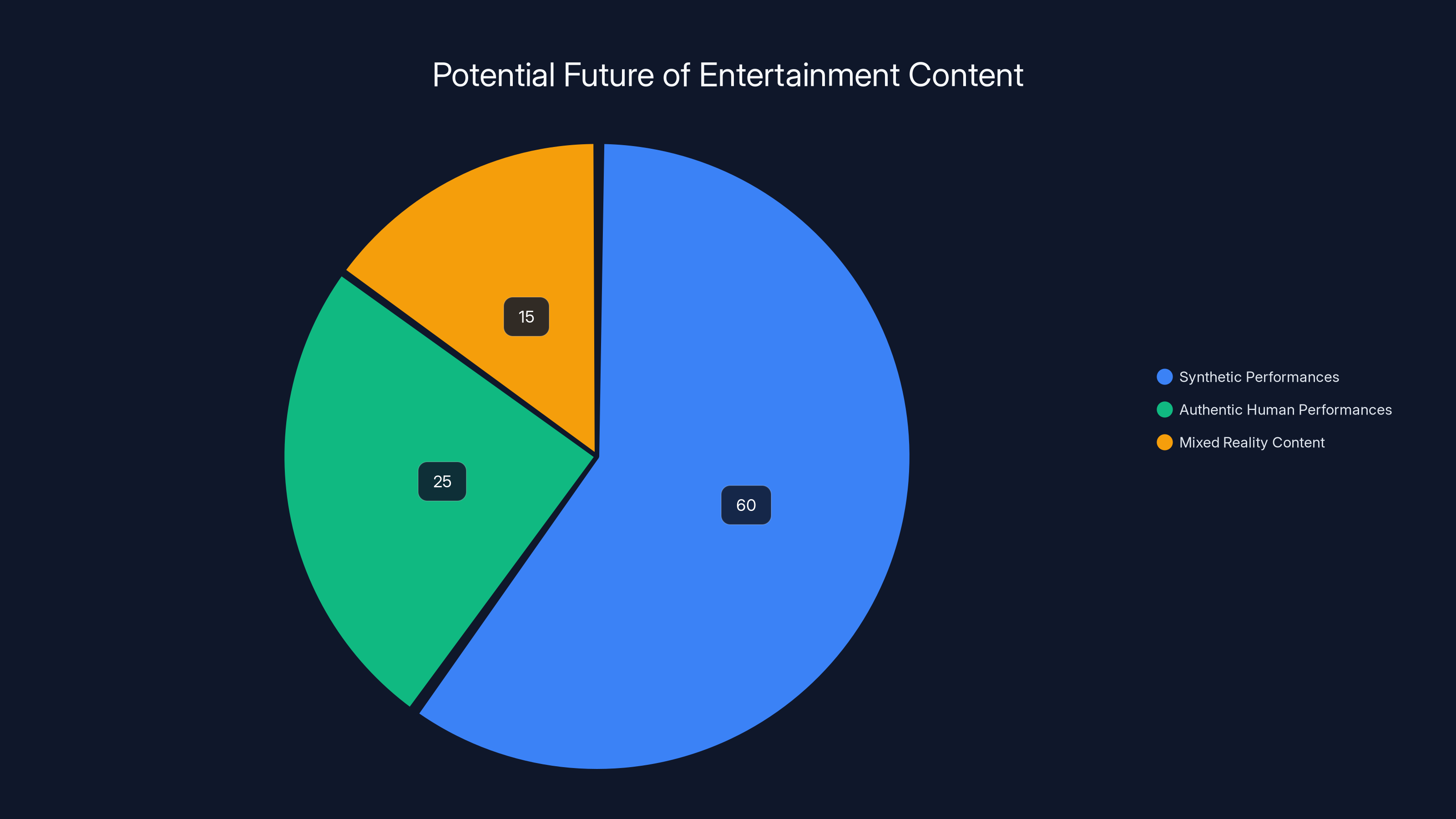

Estimated data suggests synthetic performances could dominate future content, with authentic human performances becoming a niche market.

International Complications: Different Laws, Same Problem

The entertainment industry is global. A movie made in the US gets distributed in Europe, Asia, Australia, everywhere. But AI likeness law is national (or even state-level in the US).

Europe has GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), which provides strong privacy protections. Technically, you probably can't train an AI on someone's biometric data without their explicit consent under GDPR. That's a more protective standard than what exists in the US.

But GDPR has enforcement challenges, especially for AI trained on publicly available data. And it doesn't necessarily address the synthetic likeness question.

China is moving faster than most countries on AI regulation, but their approach is more about controlling political speech than protecting individual rights.

The UK has been deliberating on AI regulation separately from GDPR. Australia, Canada, and other countries are all developing their own frameworks. And they're all different.

For someone in the entertainment industry, this creates a nightmare compliance scenario. You might be protected under California law but not under UK law. Something that's legal to do in Singapore might be illegal in Germany.

Studios will end up following the most restrictive rule globally just to be safe. But that's not guaranteed. It's more likely that different rules will apply in different markets, creating a patchwork where some productions are available in some countries but not others.

This also creates opportunities for bad actors. If something is illegal in the US but legal in another jurisdiction, a bad actor could produce it elsewhere and distribute it globally. It's similar to how deepfake porn has been such a problem—it's produced in jurisdictions with lax laws and then distributed everywhere.

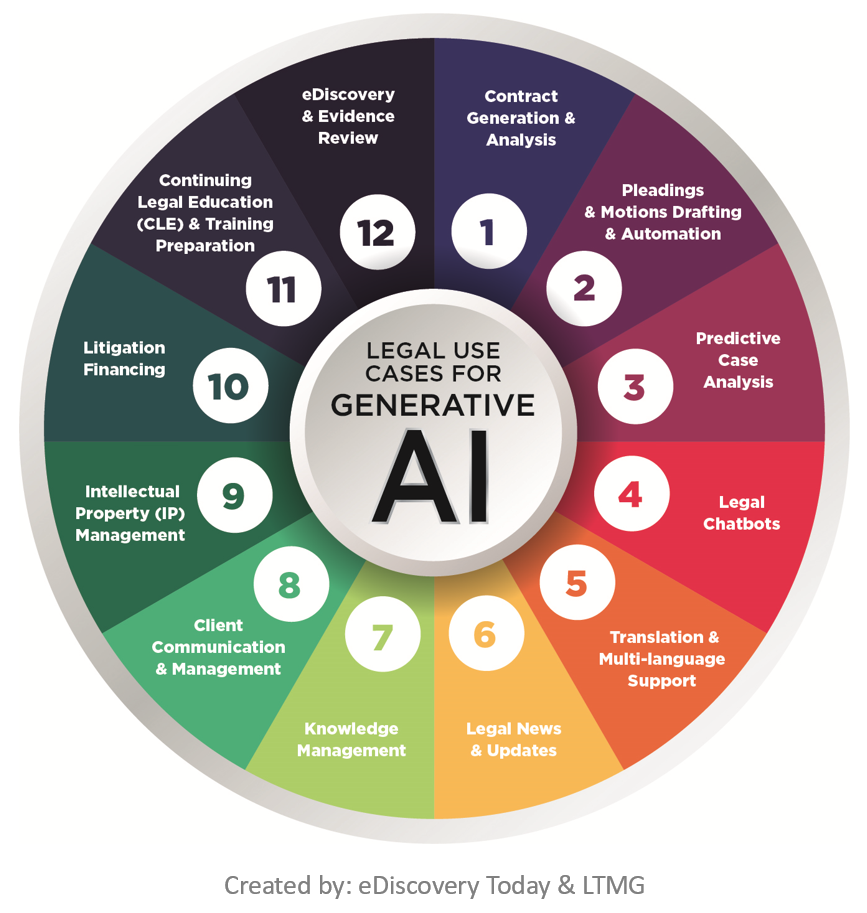

The Positive AI Use Cases (They Exist, But Are Underrated)

It's important to note that synthetic celebrities aren't entirely bad. There are genuinely useful applications.

One example: accessibility. If you could have synthetic versions of actors' performances dubbed into different languages instantly, with their actual face and voice, that would improve accessibility dramatically. Right now, dubbing requires hiring voice actors who approximate the original actor's performance. With synthesis, you could create perfect linguistic localization while preserving the original actor's face and voice.

Another example: preserving performances. Actors age. Some actors have died. But if you could synthesize a younger version of an actor for archival or educational purposes, you could preserve their work indefinitely. Imagine being able to show someone's entire career arc with perfect visual consistency.

There's also potential for consent-based, profitable collaboration. An actor could license their likeness to studios, and then that synthetic version could work continuously without the actor needing to be physically present. They'd earn ongoing royalties for minimal additional work.

These are all positive use cases that require the same technology as the problematic ones. The difference is consent and payment. If you're using synthetic celebrities with explicit permission and compensating them fairly, it's great technology. If you're doing it without permission, it's exploitation.

The challenge is creating legal frameworks that enable the good uses while preventing the bad ones. That's what legislators are struggling with.

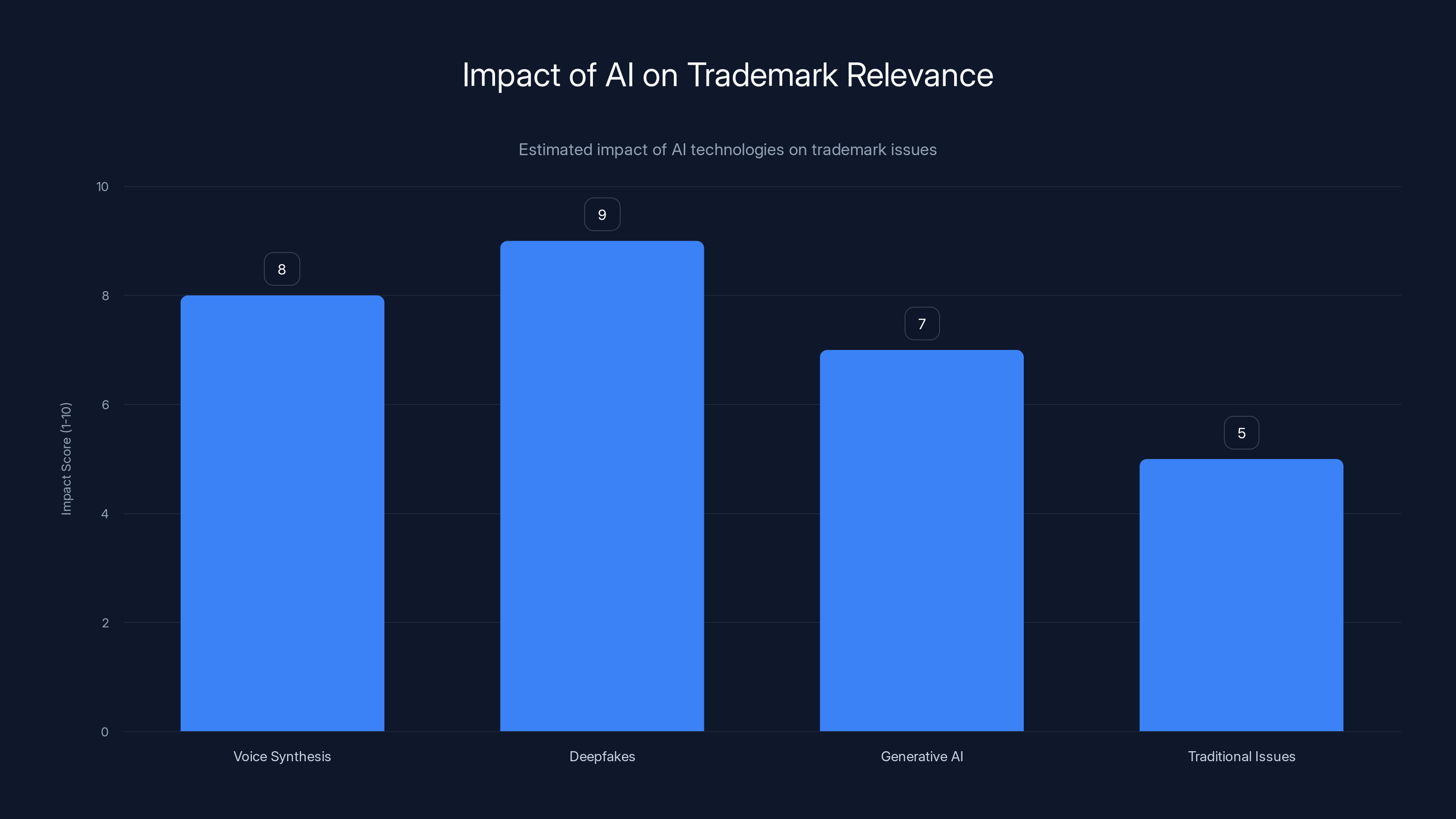

AI technologies like voice synthesis and deepfakes have significantly increased the complexity of trademark issues, surpassing traditional concerns. Estimated data.

What McConaughey's Trademark Actually Protects (And Doesn't)

Circling back to the original point: McConaughey's "Alright, alright, alright" trademark is a defensive move in a game that's just begun.

What it protects:

- Someone else using the phrase directly in commercial contexts without permission

- Merchandise with the phrase sold under another brand's name

- Commercial services that use the phrase to imply his endorsement

What it doesn't protect:

- Someone creating a deepfake of him saying something different

- Someone synthesizing his voice to perform in another context

- Someone creating a synthetic version of him for non-commercial purposes

- Someone creating parody or political speech using his likeness

- Someone using the phrase in transformative art or commentary

In some ways, the trademark is almost quaint. It's protecting against a form of exploitation (unauthorized commercial use of a catchphrase) while leaving him vulnerable to a more sophisticated form of exploitation (perfect synthesis of his entire persona).

But it's a start. And it's emblematic of what celebrities are going to do: grab whatever legal protections are available right now, knowing that they're incomplete but hoping they at least create a baseline.

The real protection will have to come from new laws specifically addressing digital likenesses, voice cloning, and synthetic celebrities. Those are coming. But they'll take years to develop and implement.

In the meantime, everyone is operating in a legal gray zone where the technology is advancing faster than the rules governing it.

The Future: What Happens Next?

There are a few possible futures.

Scenario one: strong regulation. Congress or other legislative bodies pass laws requiring explicit consent for AI likeness use, mandating compensation, and creating clear penalties for violation. This protects individuals but makes it much more expensive to use synthetic celebrities, potentially limiting the technology's adoption.

Scenario two: industry self-regulation. Entertainment industry organizations (studios, unions, guilds) create standards and best practices that limit synthetic celebrity use to consensual, compensated situations. This protects industry members but leaves independent creators vulnerable.

Scenario three: limited protection. Scattered state and international laws create a patchwork where some people are protected and others aren't. The most vulnerable (small creators, non-union workers) get exploited, while A-list celebrities negotiate individual protections.

Scenario four: no real protection. Courts and legislatures fail to keep pace with technology, synthetic celebrities become normalized, and there's mass disruption to entertainment labor markets with minimal legal recourse for affected individuals.

I'd guess we're heading toward a combination of scenarios two and three: some industry standards, some state laws, continued legal ambiguity. It's the path of least resistance politically and legislatively.

But the economic pressures are real. Studios will use synthetic celebrities if the quality is good enough and the legal risk is manageable. And good enough is coming fast.

What's most likely is that synthetic celebrities become increasingly common for secondary roles, stunts, and background work before reaching lead roles. The transition will be gradual, which means people affected will have some time to adapt. But it will happen.

The Ethical Layer: Beyond Legal Protection

Laws and contracts are important, but there's also an ethical question that's separate from the legal one: just because you can create a synthetic version of someone doesn't mean you should.

Consider the weird implications. If a studio owns the rights to a synthetic version of an actor, does that actor lose control of their own image? What if they want to retire and stop working, but a studio has the rights to generate new content with their synthetic version indefinitely?

Or consider legacy: what happens to the synthetic version of a deceased actor? Can their heirs control it? Can a studio keep profiting from it forever, creating new performances in perpetuity?

These questions sound like science fiction but they're coming. And the legal system hasn't even begun to address them.

There's also the question of authenticity. There's something about knowing that a performance was real—that a human actually did the thing you're watching—that matters to audiences. Once people get comfortable with synthetic celebrities, will that sense of authenticity disappear?

Or will there be a market premium for "authentic" human performances, similar to how vinyl records have made a comeback despite digital music being objectively higher quality? Maybe seeing a human actor perform will become a luxury good, while synthetic celebrities handle the bulk of content production.

These are speculative questions, but they're worth thinking about now before the technology becomes so embedded in entertainment that these choices feel inevitable rather than chosen.

What Creators Should Do Right Now

If you're a creator, entertainer, or anyone with commercial value in your likeness or voice, here are concrete steps you should take today.

First, document everything. Create recordings of your voice, video of your appearance, descriptions of your distinctive mannerisms. Register these somehow—through a lawyer, a notary, a service that provides timestamped evidence. This creates a baseline of what's authentically "you."

Second, audit your digital footprint. How many hours of video of you exist online? Where is it? Is it in contexts where you explicitly gave permission? Could it be scraped and used to train an AI model of you? Consider whether you want to make strategic decisions about what you share publicly.

Third, update your contracts. If you're signing with any company that might want to use your image, voice, or likeness—or create a synthetic version—be explicit about what you're authorizing and what you're not. Specify whether synthetic versions are allowed and at what compensation. Don't assume silence means protection.

Fourth, consider trademarking distinctive phrases or characteristics. If there's something unique about your communication style or appearance, trademark it if possible. It won't be perfect protection, but it's better than nothing.

Fifth, stay informed. Follow the legal developments in your state and country around AI regulation, right of publicity, and likeness protection. The laws are changing rapidly.

Sixth, join or support organizations pushing for stronger protections. If you're in entertainment, unions matter now more than ever. If you're not in a union, professional organizations and advocacy groups are becoming important.

Lastly, think about what you're comfortable with. If a company offered you money to use your synthetic likeness in perpetuity, would you do it? Most creators probably should, depending on the compensation. But think about it proactively rather than reactively.

The McConaughey Moment

Matthew McConaughey's trademark on "Alright, alright, alright" is going to look like a relic in twenty years.

Right now, trademarking a catchphrase feels like the appropriate legal tool for protecting a celebrity's identity. But it's a band-aid on a much larger problem. The real issue is that in an AI-powered future, your identity itself becomes reproducible, synthesizable, and infinitely copyable.

A trademark protects a phrase. It doesn't protect you from being cloned.

What we're seeing with McConaughey is the beginning of celebrities fighting back against that reality. But fighting within existing legal frameworks (trademarks, contracts, right of publicity) is like fighting a fire with a garden hose. It might slow things down, but it won't stop the underlying trend.

The real battle will be fought in legislatures, courtrooms, and corporate boardrooms over the next decade. It will determine whether actors, musicians, and creators maintain control of their likenesses in the age of AI, or whether they become assets that can be stripped, copied, and exploited.

Right now, the outcome is uncertain. The technology is advancing faster than protections are being built. But consciousness is rising. People are paying attention. McConaughey's trademark is a signal that this fight is real.

The question isn't whether synthetic celebrities are coming. They're already here. The question is whether the people they're based on will have any say in what they do.

TL; DR

- Synthetic Celebrities Are Here: AI can now clone voices and create deepfakes convincingly enough to fool most viewers. The technology has reached "good enough" for mainstream use.

- Legal Frameworks Are Decades Behind: Trademark law, copyright law, and right of publicity were all designed before AI could synthesize people. McConaughey's trademark protects a phrase but not his synthetic likeness.

- SAG-AFTRA Won Protections: The 2023 strike resulted in stronger AI-related protections for union actors, but non-union workers and independent creators have minimal protection.

- Studios Have Economic Incentives: Synthetic actors cost a fraction of human actors and can be reused forever without royalties or scheduling conflicts. The economic pressure to adopt synthetic celebrities is immense.

- Bottom Line: A legal and ethical framework for synthetic celebrities is developing, but it's lagging behind technology. Action on this issue is necessary before the entertainment industry faces massive disruption.

FAQ

What does Matthew McConaughey's trademark actually protect?

McConaughey's "Alright, alright, alright" trademark protects against unauthorized commercial use of that specific phrase. It prevents companies from using the phrase to sell products or services without his permission or implying his endorsement. However, it doesn't prevent someone from creating a deepfake of him saying different words, synthesizing his voice, or creating synthetic performances. The trademark is narrow—it protects a phrase, not his entire identity.

Can AI actually create a convincing deepfake of any celebrity?

It depends on the type of deepfake and the quality required. Voice synthesis can create convincing vocal replicas from as little as 3-5 minutes of audio sample, and these tools are publicly available. Facial deepfakes are more complex and require more training data, but they're improving rapidly. For most non-expert viewers, high-quality deepfakes are difficult to distinguish from authentic footage. However, forensic analysis can often detect artifacts in deepfakes, especially around the eyes, teeth, and lighting inconsistencies.

Who owns the rights to my voice if it's synthesized without permission?

This is legally ambiguous and varies by jurisdiction. You likely have a right of publicity claim in most states, meaning you can sue for unauthorized commercial use of your likeness (which includes voice). However, right of publicity protections are state-dependent and not always clear-cut for synthesized content. If your voice was cloned from your actual recordings without permission, you might have copyright claims as well. Your strongest protection is a contractual clause explicitly prohibiting voice synthesis, which is why unions like SAG-AFTRA negotiated this into contracts.

Will AI-generated synthetic actors replace human actors?

Partial replacement is almost certain. Background actors, extras, and lower-budget productions will likely transition to synthetic performers first because the cost difference is dramatic. Voice acting and stand-in/stunt work are also vulnerable. However, lead actors will probably be replaced more slowly because audiences value authenticity and there are established star systems with financial incentives to use famous human actors. The transition will be gradual—probably 10-20 years before synthetic actors dominate secondary roles in major productions.

What legal protections exist for voice actors and singers?

Right now, protections are weak and state-dependent. Union voice actors have some protections through their guilds. SAG-AFTRA's 2023 contract includes voice protections. For non-union voice actors and singers, protections are mainly limited to copyright claims if someone uses your actual recordings without permission, or right of publicity claims for commercial unauthorized use of your synthesized voice. However, synthesizing someone's voice for non-commercial purposes is largely unregulated. This gap is intentional—Congress hasn't yet passed federal legislation specifically addressing voice cloning.

Should I trademark my catchphrase or distinctive characteristics?

Probably yes, if you have something distinctive. It's a limited form of protection—it prevents direct commercial use of the phrase or characteristic—but it's better than nothing. However, trademark is most effective for specific phrases or logos. You can't trademark your overall personality or communication style as effectively. Pairing trademark with explicit contractual language about synthetic likeness use is more comprehensive protection.

How do I prevent my voice from being cloned?

You can't entirely prevent it if your voice is available publicly (interviews, podcasts, performances). The best strategies are: (1) document your voice professionally and ensure you have proof of authentic samples; (2) use contractual protections to prevent anyone from collecting voice data without consent; (3) stay informed about where your voice appears and audit the contexts; (4) support legislation restricting non-consensual voice cloning. In the immediate term, if someone creates a synthetic version of your voice used deceptively (like synthesized endorsements), you have potential legal claims for fraud or right of publicity violation.

What does the SAG-AFTRA AI agreement actually do?

The 2023 SAG-AFTRA agreement requires studios to obtain explicit consent from actors before creating digital replicas and mandates additional compensation for synthetic likeness use (background actors get a baseline payment, principal actors negotiate individually). It sets a precedent for other unions but only covers union members. It also creates mandatory disclosure when digital replicas are used, which helps protect audiences from deception. However, it doesn't address non-union actors or non-commercial deepfakes.

Is deepfaking someone illegal?

It depends on context and jurisdiction. Creating a deepfake of someone for political parody or commentary might be protected speech. Creating a deepfake for non-consensual sexual content is illegal in several states and countries. Using a deepfake to defraud people (synthesizing fake endorsements or financial statements) is likely fraud. Using someone's synthetic likeness for commercial purposes without consent likely violates right of publicity laws in most states. But the legal landscape is still developing and varies dramatically by location.

Why don't we have federal legislation on deepfakes and synthetic likenesses?

Legislation is slow, especially when the technology is rapidly evolving. Lawmakers are cautious about restricting free speech or innovation too heavily. There's also disagreement about where to draw lines—should all deepfakes be illegal? Only deceptive ones? Only commercial ones? Different interest groups (tech companies, entertainment unions, civil liberties organizations) have conflicting priorities. In the meantime, some states have passed limited protections (California, Illinois), and international frameworks are developing separately. Federal legislation is probably coming in the next few years, but it's not guaranteed to be comprehensive or well-designed.

Key Takeaways

- AI can now synthesize celebrity voices and faces convincingly enough to fool most viewers, but legal protections haven't evolved to address this capability

- Trademark law (like McConaughey's) protects specific phrases but fails against deepfakes and voice synthesis—existing legal frameworks are decades behind technology

- The 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike achieved protections for union actors, but non-union workers and independent creators remain essentially unprotected from synthetic exploitation

- Studios have enormous economic incentive to adopt synthetic actors: one-time training cost (2M per human actor, with unlimited reuse—a financial pressure that will drive adoption regardless of ethical concerns

- A comprehensive legal framework addressing synthetic likenesses is still 2-5 years away, meaning the technology will likely be deeply embedded in entertainment production before meaningful protections exist

Related Articles

- Matthew McConaughey Trademarks Himself: The New AI Likeness Battle [2025]

- OpenAI Contractors Uploading Real Work: IP Legal Risks [2025]

- AI Accountability & Society: Who Bears Responsibility? [2025]

- Wikipedia's Enterprise Access Program: How Tech Giants Pay for AI Training Data [2025]

- Grok AI Regulation: Elon Musk vs UK Government [2025]

- Why Grok's Image Generation Problem Demands Immediate Action [2025]

![AI Identity Crisis: When Celebrities Own Their Digital Selves [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-identity-crisis-when-celebrities-own-their-digital-selves/image-1-1768568961897.jpg)