Artificial Lung Machine Kept Patient Alive 48 Hours Without Lungs: A Medical Breakthrough

Here's something that shouldn't be possible: a person living without lungs for two full days while surgeons fought a septic infection that had literally liquified his lung tissue. In January 2026, at Northwestern University's surgical suite, a 33-year-old man became the first to survive a bilateral pneumonectomy, the removal of both lungs, by relying entirely on a custom-engineered artificial lung system. No lungs. No native breathing. Just engineering, desperation, and a team of surgeons who decided the impossible was worth attempting.

The patient arrived at the hospital in the grip of a medical nightmare. Influenza B had complicated into a secondary infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacteria resistant to nearly every antibiotic in the arsenal. The infections triggered acute respiratory distress syndrome, the kind that doesn't just damage lungs—it turns them into a soupy, non-functional mass incapable of gas exchange. His kidneys were shutting down. His heart had stopped. He was on the edge of death in every measurable way.

But the surgeons faced an impossible choice: the only thing that could save him was removing the very organs that were killing him. Yet removing both lungs creates a physiological nightmare that's kept surgeons from attempting bilateral pneumonectomy for decades. The heart, the bloodstream, the entire circulatory system—they're all designed around the presence of lungs. Remove them both simultaneously, and you don't have minutes. You have seconds before the right side of the heart collapses from nowhere to pump.

So the team did something radical. They built a device. A custom artificial lung system engineered specifically for this patient, designed to solve a problem most surgeons thought was permanently unsolvable. The system worked. It kept him alive for 48 hours without native lungs, long enough for the sepsis to clear, long enough for a transplant to arrive. This isn't just a medical anecdote. It's a blueprint for saving people previously written off as beyond hope.

The Physiology Problem Nobody Could Solve

Before you can understand why removing both lungs is so dangerous, you need to understand how the heart and lungs work together as a system. It's not just about getting oxygen into the blood. It's about pressure, flow, and the precise mechanics of how the right side of your heart functions.

Your heart is actually two pumps in one body. The left side, the systemic circuit, receives oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and pumps it throughout your entire body. That's the powerful pump. That's what you feel beating in your chest.

The right side is different. The pulmonary circuit takes oxygen-poor blood returning from the body and pumps it into the lungs for gas exchange. But here's the key: the pulmonary vascular bed, all those miles of tiny capillaries inside the lungs, isn't just there to exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide. It acts as a pressure buffer. It's a capacitor.

When the right ventricle pumps blood out, the lungs absorb that pressure and volume like a sponge. They dampen the force. They keep the pressure manageable. This is critical because the pulmonary vessels are delicate. They're designed to operate at low pressure. The right ventricle isn't a powerful pump like the left side. It's more of a gentle pusher.

Now imagine removing the lungs entirely. The right ventricle pumps and suddenly has nowhere to send the blood. The pulmonary arteries are closed. There's no capacitor. There's no buffer. The pressure spikes immediately. The right ventricle distends like an overfilled balloon. Within minutes, it begins to fail.

At the same time, the left side of the heart loses its source of blood. With no lungs to oxygenate it, no fresh blood returns to the left atrium. Blood pressure crashes. Systemic circulation collapses. Without intervention, this sequence kills you in under five minutes.

This is why most double lung transplants aren't done simultaneously. Surgeons perform them sequentially. Replace one lung, get it working, re-establish pulmonary circulation. Then replace the second lung while the first one is already handling the load. It's slower. It's safer. It works.

But it requires time, and time was something this 33-year-old man didn't have.

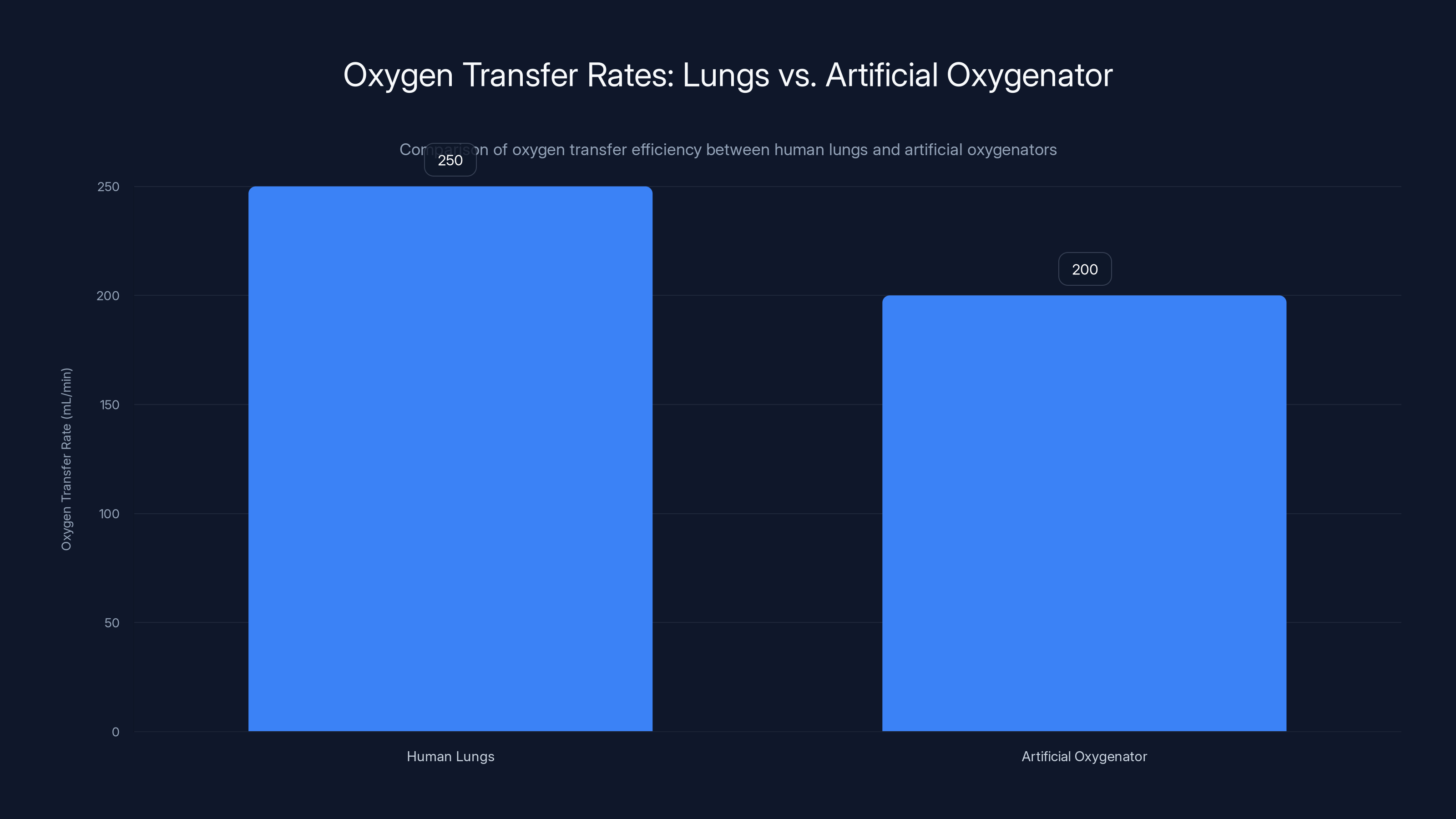

Human lungs transfer approximately 250 mL of oxygen per minute at rest, while an artificial oxygenator achieves around 200 mL/min, highlighting the efficiency gap.

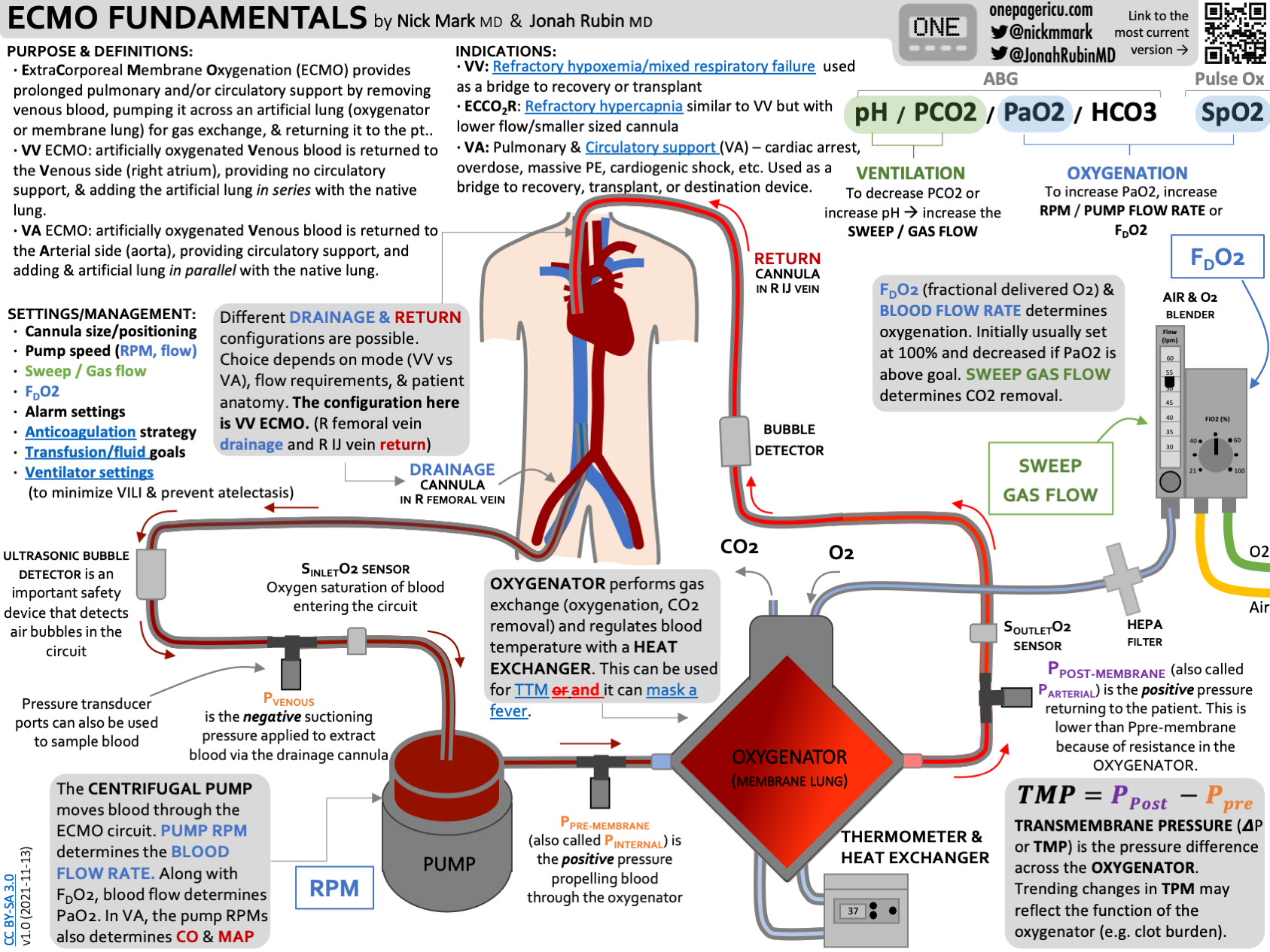

ECMO: The Existing Solution With a Fatal Flaw

For decades, when surgeons absolutely had to remove both lungs at once, they had one tool: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, or ECMO. It's a mechanical lung. A pump takes blood out of your body, runs it through an oxygenator, removes carbon dioxide, adds oxygen, and pumps it back in. It works. It's kept people alive for over a year in some cases.

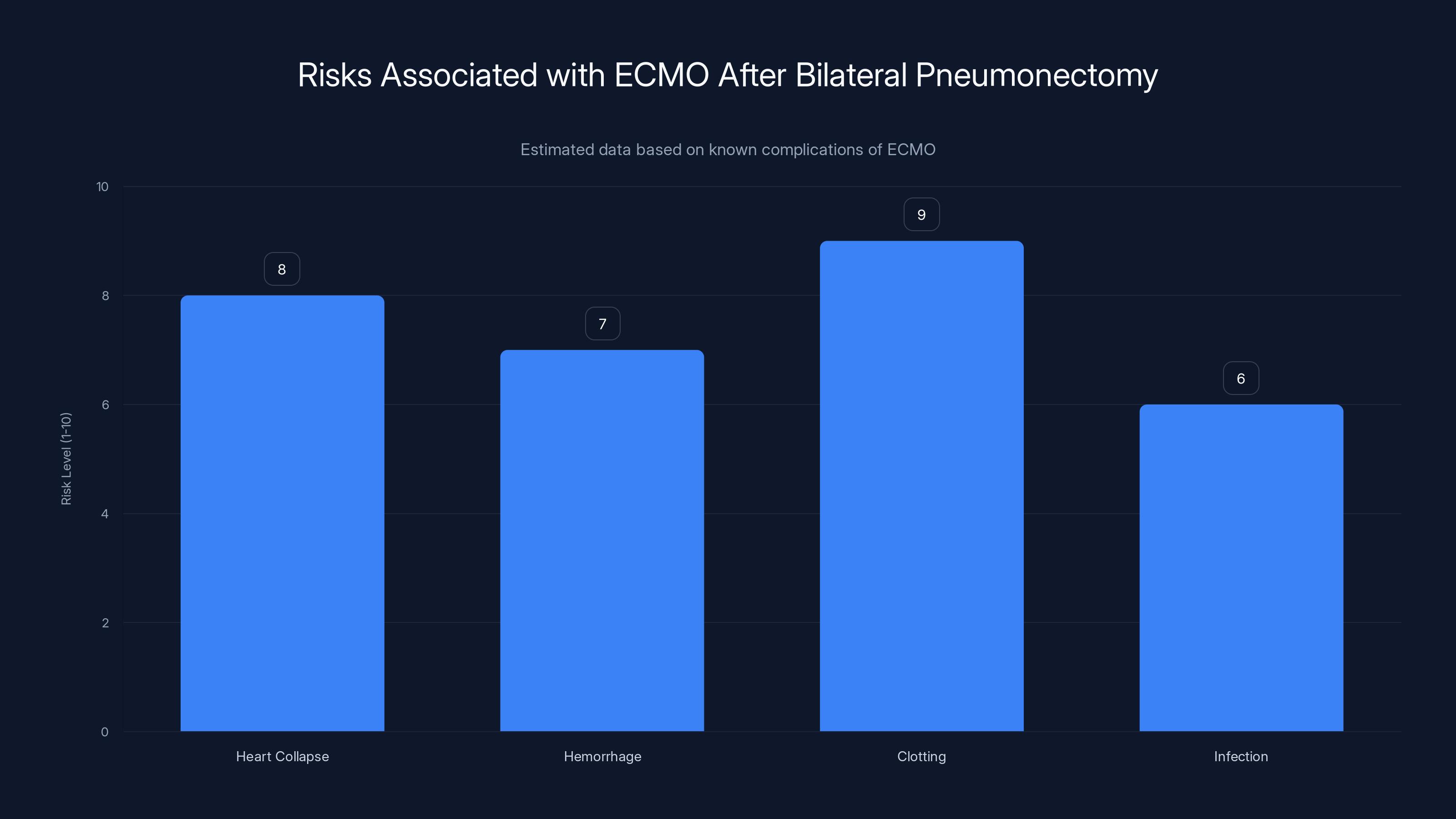

But ECMO has a catastrophic problem when both native lungs are removed: the empty chest cavity.

Your lungs take up most of the space in your thorax. They surround your heart on both sides. They provide physical structure and pressure that keeps your heart in its proper anatomical position. Remove them, and you have a void. A empty space where blood pools. Where fluids accumulate. The heart, which evolved to be supported by the physical presence of lung tissue on both sides, begins to flop around. Surgeons call this collapse. The heart can literally fold in on itself.

At the same time, that empty cavity becomes a hemorrhage zone. Without the lungs to occupy the space, internal bleeding can occur more easily. Blood loss becomes harder to control. Infection becomes easier to establish in the surgical void.

And there's more. Circulating blood through complex ECMO machinery increases your risk of clotting substantially. Clots mean stroke. Clots mean limb loss. Clots mean death. The longer blood is outside the body, running through plastic tubes and artificial membranes, the higher the clotting risk climbs.

For all these reasons, ECMO with bilateral pneumonectomy is considered a last resort, and surgeons would keep the patient in that state for the absolute shortest time possible. Hours, maybe a day at most.

This patient needed more time.

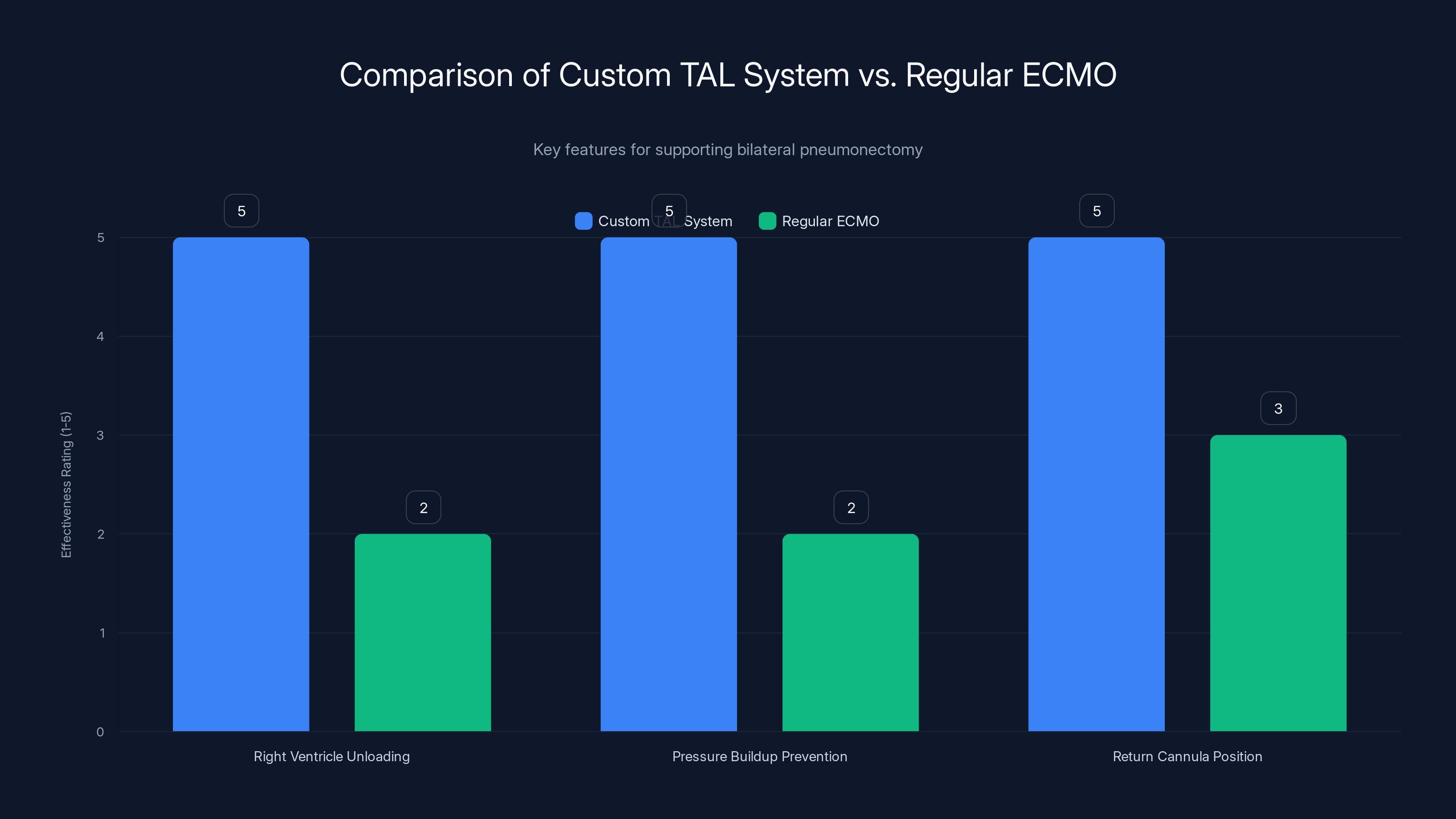

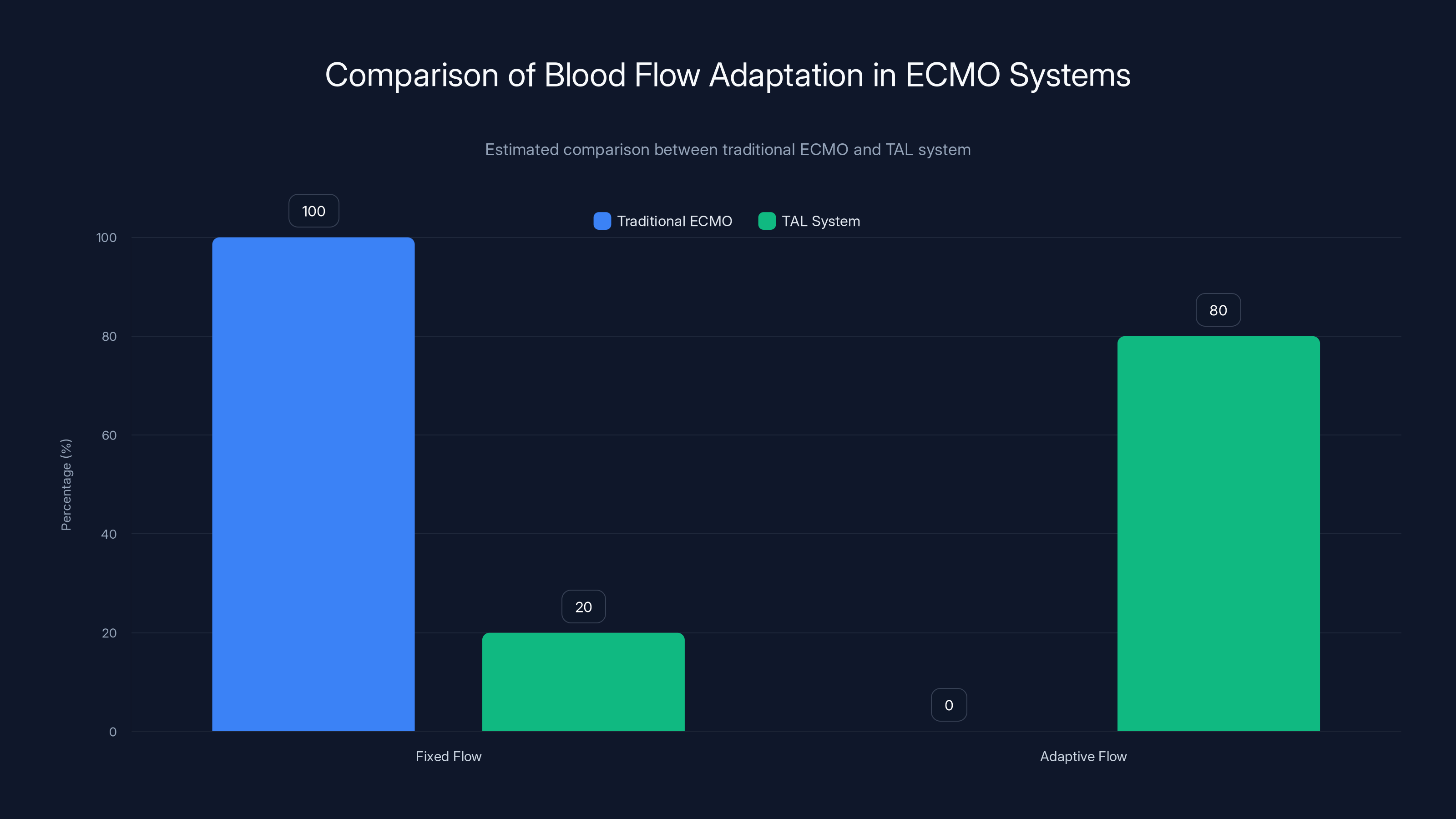

The custom TAL system is specifically designed to address the unique challenges of bilateral pneumonectomy, offering superior support in right ventricle unloading and pressure management compared to regular ECMO. Estimated data.

Enter the Custom Engineered Solution

Dr. Ankit Bharat, a surgeon and researcher at Northwestern, and his team faced a problem that had no standard answer. They needed to keep this patient alive without lungs long enough for sepsis to clear. Not just long enough for him to survive the immediate surgery, but long enough for his immune system to win the fight against Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

So they engineered something new. They called it the flow-adaptive extracorporeal total artificial lung system, or TAL. It wasn't a simple ECMO rig. It was a completely custom-designed circuit built specifically to solve the physics problem that bilateral pneumonectomy creates.

At its core was a pump and oxygenator borrowed from standard ECMO equipment. But surrounding that core were four new components, each designed to address a specific physiological challenge.

The first was a dual-lumen cannula, essentially a tube with two separate channels inside. Inserted through the internal jugular vein directly into the right atrium, this tube acted as the primary drain. Instead of pulling blood from a femoral vein in the groin like standard ECMO, this design pulled deoxygenated blood directly from where it needed to be pulled: from the right side of the heart itself.

Why does this matter? Because it unloads the right ventricle. The right ventricle doesn't have to work as hard. It doesn't have to pump against pressure that's building up with nowhere to go. By pulling blood directly from the atrium, the surgeons were essentially doing what the lungs naturally do: providing a low-resistance pathway for blood to take.

The second component was something the team called a flow-adaptive shunt. This was a tube connecting the right pulmonary artery directly back to the right atrium. When the right ventricle pumped out more blood than the external pump could handle, excess blood would recirculate back into the atrium through this low-resistance path. It's a safety valve. It protects the heart from pressure spikes. It prevents distension.

The third and fourth components worked on the problem of keeping the heart in place and preventing the physical collapse that comes with an empty chest cavity. But before we get into those details, understand what Bharat's team had done: they'd essentially replaced the lungs not just functionally but mechanically. They didn't just add oxygen to blood. They recreated the pressure dynamics, the flow characteristics, and the structural support that native lungs provide.

The 48-Hour Artificial Lung Experiment

After removing the patient's infected lungs, the surgeons connected him to the custom TAL system. The patient now had no native lungs. Every single oxygen molecule entering his blood came from the artificial oxygenator. Every carbon dioxide molecule leaving his blood went through a machine.

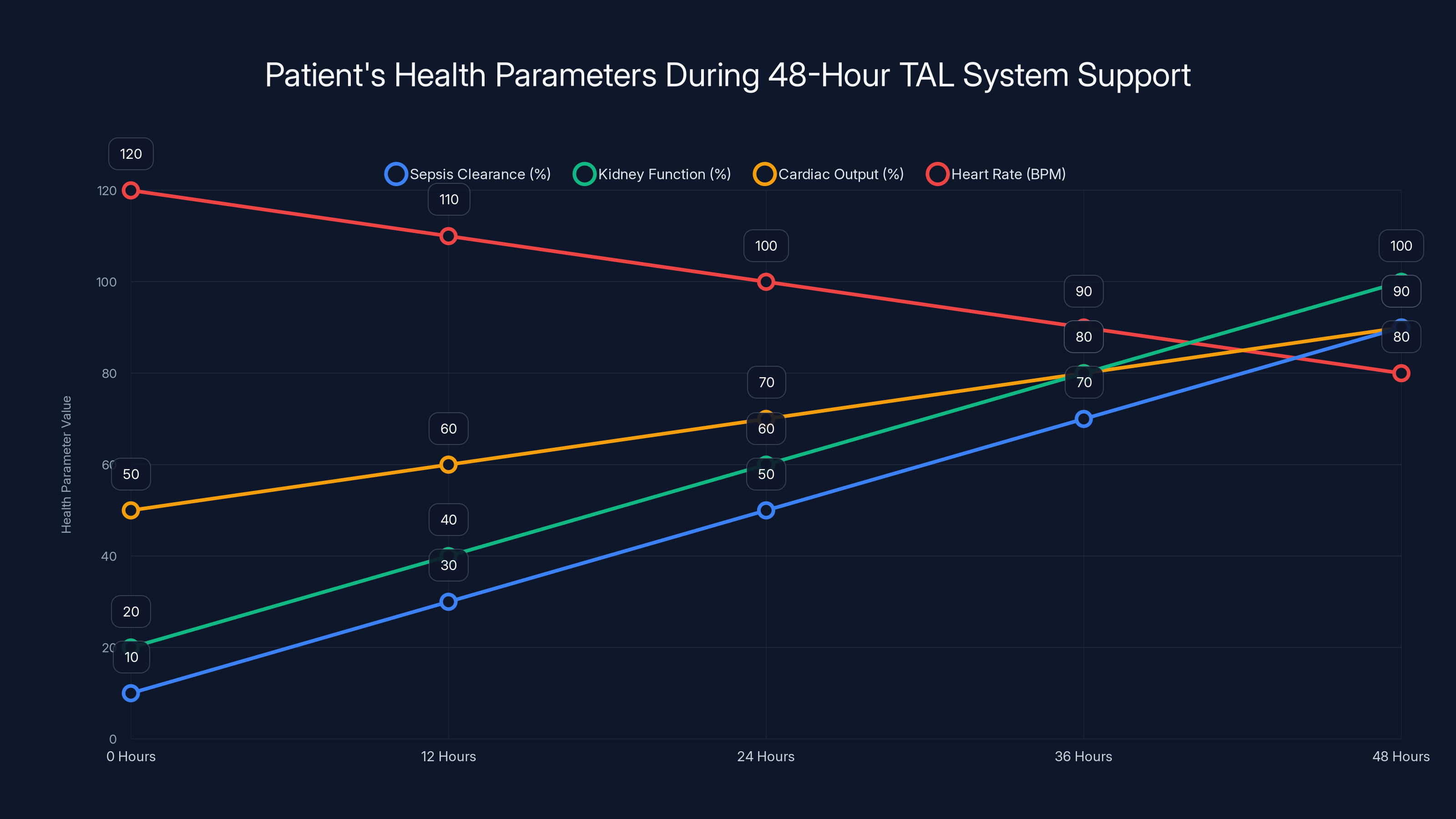

For 48 hours, this system kept him alive. More than that, it kept him stable enough for sepsis to begin clearing. The infections that had liquified his lung tissue began to lose their grip. His kidney function started to improve. His cardiac output stabilized. His heart rate normalized.

This isn't just survival. This is someone getting better while entirely dependent on artificial life support with zero native lung function. The system proved that you could maintain not just basic life signs but actual physiological improvement while a patient recovers from overwhelming sepsis, all without native lungs present.

After those 48 hours, a double lung transplant became available. The surgeons now had the option to replace his lungs with healthy donor lungs. But here's the crucial part: without the custom TAL system, that donor lung transplant never would have been possible. The patient would have been too sick. His septic shock was too severe. His cardiac function was too compromised. He would have died waiting for transplant eligibility criteria to be met.

The custom artificial lung system bought time. It created a window where he could recover enough to be a viable transplant candidate.

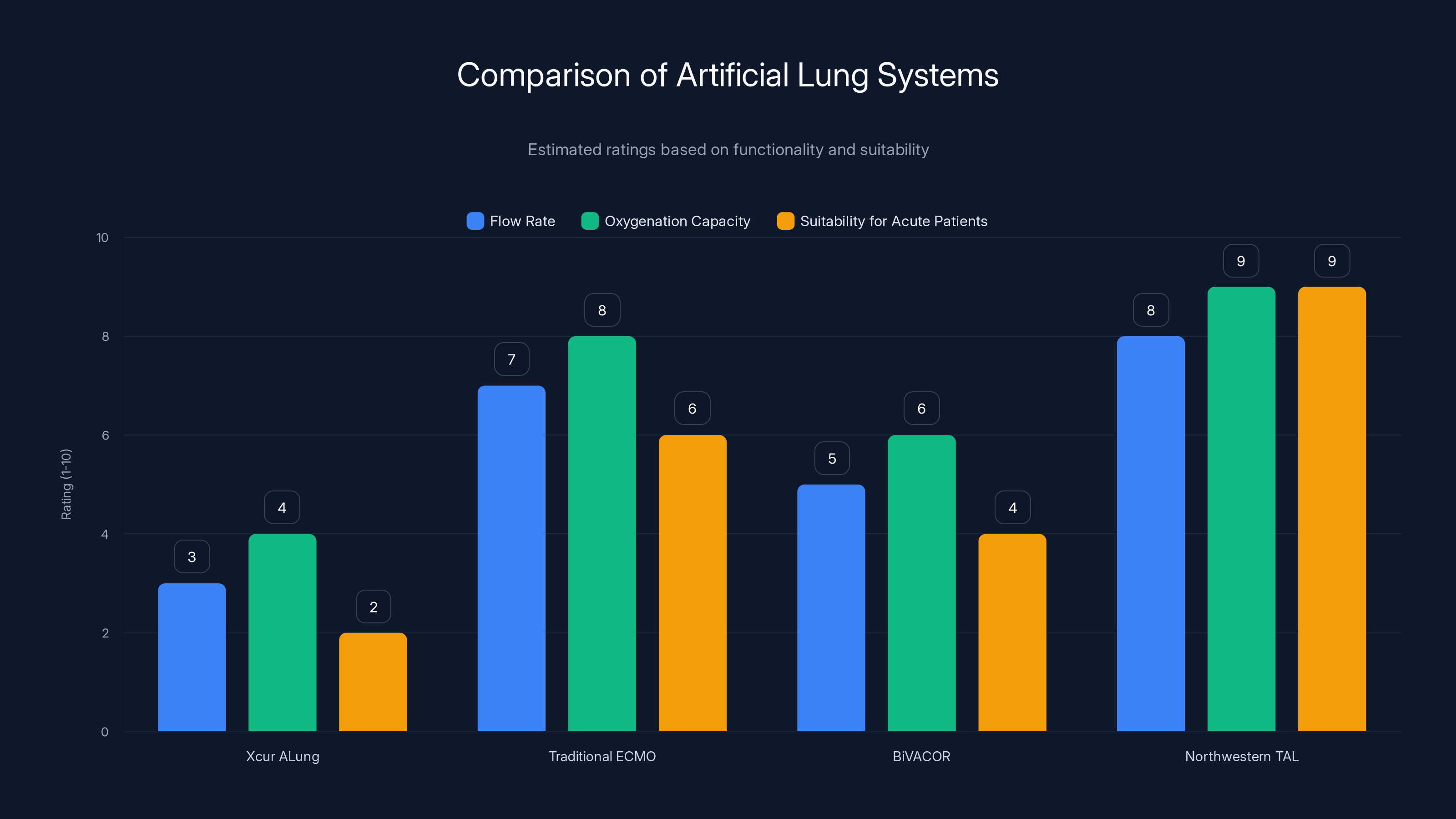

The Northwestern TAL system scores highest in flow rate, oxygenation capacity, and suitability for acute patients, making it a superior choice for specific medical conditions. Estimated data based on system descriptions.

How the Custom System Actually Worked

Let's break down the engineering more specifically, because this is where the innovation actually lives.

The dual-lumen cannula pulled blood directly from the right atrium. This blood was venous, deoxygenated, and under relatively low pressure. By draining directly from the atrium rather than from a peripheral vein, the team reduced the pressure gradient needed to get blood into the external pump. Lower pressure means less mechanical stress on the red blood cells. Less hemolysis. Less clotting.

That blood then flowed into the pump. The pump is where the engineering gets interesting. It wasn't a traditional centrifugal pump. It was adaptive. It varied its flow rate based on the demand the heart was placing on the system. If the right ventricle was trying to pump more blood than the external system could handle, the shunt would open and let excess blood recirculate. If the demand dropped, the pump would throttle back.

The oxygenator then did its job: removing carbon dioxide from the blood and adding oxygen. But unlike standard ECMO oxygenators, which run at high flows and high pressures, this system was optimized for lower pressures and adaptive flow patterns.

The blood then had to get back into the patient. This is where the surgeons faced another challenge. Standard ECMO returns blood to a peripheral artery. That works fine when lungs are still present, because the lungs absorb the pulsatile pressure and smooth out the flow. Without lungs, returning blood to a peripheral artery creates pressure waves that have nowhere to dissipate. These pressure waves can damage blood vessels. They can cause bleeding.

So the TAL system returned blood not to a peripheral artery but to a central location: the ascending aorta, the main vessel leaving the heart. This position allowed the blood to enter the systemic circulation without creating the problematic pressure spikes that would occur in the peripheral vasculature.

The flow-adaptive shunt served as both a safety mechanism and a physiological compensator. When the right ventricle was unable to function (because its normal outlet, the lungs, didn't exist), blood would naturally want to flow in the path of least resistance. The shunt provided that path. By recirculating excess blood directly back to the atrium, the shunt prevented dangerous pressure buildup while also ensuring that the right side of the heart remained adequately perfused.

The Infection That Required Everything

Pseudo aeruginosa is no joke. It's a gram-negative bacterium that thrives in biofilms and mucous secretions. It produces toxins that directly damage lung tissue. When combined with influenza, which damages the respiratory epithelium and allows secondary bacterial infection to establish, you get a perfect storm.

But the real problem wasn't just the bacteria. It was the necrotizing infection. Necrotizing means the bacteria and the body's immune response to it were actively killing lung tissue. The patient's lungs weren't just inflamed. They were dying. The tissue was liquifying. This is acute respiratory distress syndrome in its most severe form.

Antibiotics were failing. Carbapenem-resistant bacteria meant that even the drugs of last resort weren't working. The only option was to remove the source of infection entirely.

Once the lungs were gone, antibiotic therapy could finally work. Without the necrotizing infected tissue, without the biofilm that bacteria were hiding in, the antibiotics could clear the remaining Pseudomonas from the bloodstream. The septic shock began to resolve. The organs that were failing—kidneys, heart—began to recover.

This is what the 48-hour window created. Not just survival, but actual recovery. Actual physiological improvement. That's the breakthrough.

ECMO after bilateral pneumonectomy presents significant risks, notably high clotting and heart collapse risks. Estimated data.

The Physics of Oxygenation Without Lungs

Here's a question: how much oxygen do you actually need?

The human body at rest requires about 250 milliliters of oxygen per minute. That might sound like a lot, but consider that your lungs can process about 5 to 7 liters of air per minute. Most of that air is never actually used. It's just passing through.

An artificial lung system doesn't need to move that much air. It just needs to transfer that 250 milliliters of oxygen into the blood and remove an equivalent amount of carbon dioxide. It can do this with far more efficiency than your native lungs because it doesn't need to deal with all the anatomical constraints of respiratory mechanics.

But here's the catch: artificial oxygenators use membrane technology. Blood comes into contact with a semipermeable membrane. On the other side of that membrane is a gas mixture, usually containing oxygen. Oxygen diffuses across the membrane into the blood. Carbon dioxide diffuses the opposite direction.

This works, but it's not as efficient as lung tissue. Your lungs have hundreds of millions of alveoli, each one a tiny sac with a massive surface area for gas exchange. An artificial oxygenator has a single membrane, maybe a few square meters of surface area total.

The math works like this: with an oxygenator surface area of about 3 square meters and a blood flow rate of about 5 liters per minute, the system can achieve oxygen transfer rates of around 200 milliliters per minute. That's almost enough to meet resting metabolic demand.

But the patient wasn't at rest. Even sedated, in a medical coma, the body's metabolic demand was higher. Plus, there's a safety margin needed. The team probably ran the system to deliver 300 to 350 milliliters of oxygen per minute, which means running the external pump at higher flow rates than normal. This increases clotting risk, which is why anticoagulation therapy was critical.

Anticoagulation and the Clotting Crisis

Any time blood touches plastic or artificial membranes for extended periods, clotting becomes a major threat. The body recognizes foreign material and activates the coagulation cascade. Blood gets sticky. Clots form.

For a 48-hour artificial lung support, the patient would have been on aggressive anticoagulation. Likely heparin infusions to prevent clot formation. The surgeons would have been walking a razor's edge: anticoagulate enough to prevent clotting but not so much that they cause bleeding complications.

This is where the design of the TAL system mattered. By using lower-pressure flows and adaptive shunting, the system minimized the shear stress on blood cells and platelets. Lower shear stress means less platelet activation, less clotting cascade activation. Better outcomes.

Still, monitoring would have been constant. Regular blood clotting studies. Platelet counts. D-dimer levels. Prothrombin time. The ICU team would have been adjusting anticoagulation therapy in real time based on lab results.

Estimated data shows significant improvement in sepsis clearance, kidney function, and cardiac output, with heart rate normalizing over 48 hours of TAL system support.

Why Sequential Lung Transplants Couldn't Work Here

Normally, when a double lung transplant is needed, surgeons do it sequentially. Replace one lung, let it establish circulation, then replace the second. This approach has been the standard for decades because it works. It avoids the hemodynamic crisis of bilateral pneumonectomy.

But this patient couldn't wait for sequential. His lungs were actively necrotizing. They were actively generating sepsis. Every hour that passed, the infection spread further through his bloodstream. His organs were failing progressively.

Sequential transplant would have required waiting for the first lung to establish, which takes at least an hour or two. Then waiting for the second lung donor to be procured and transported. In this patient's timeline, he would have been dead before the first donor lung was even in the hospital.

Bilateral pneumonectomy with immediate TAL support was the only option that gave him a chance.

The Innovation in Adaptive Flow

The "flow-adaptive" part of the system's name is important. Traditional ECMO runs at fixed pump speeds. The pump outputs a set volume of blood per minute, whether the heart needs it or not.

The TAL system was different. It adapted. When the right ventricle was trying to pump harder, the system allowed more blood to flow through the external pump. When the heart was resting, the system allowed flow to decrease. This adaptive behavior is closer to how your native cardiovascular system actually works.

The shunt mechanism made this possible. By providing a low-resistance recirculation pathway, the shunt essentially acted as a pressure relief valve. If the right ventricle was generating too much pressure, blood would take the path of least resistance and recirculate. If pressure was adequate, blood would flow through the oxygenator and back to the systemic circulation.

This adaptive mechanism reduces unnecessary stress on the right ventricle. It prevents the distension that would occur if blood had nowhere to go. It's a elegant solution to a mechanical problem that plagued all previous artificial lung systems.

The TAL system significantly improves adaptive blood flow management compared to traditional ECMO systems, reducing stress on the heart. Estimated data.

Recovery and Transplant Success

After 48 hours on the TAL system, the patient's condition had improved enough that a double lung transplant became feasible. The sepsis was under control. Kidney function was improving. Cardiac function had stabilized. The surgeons could now perform the transplant with reasonable confidence.

The actual transplant was still risky, of course. Any lung transplant carries risks. Rejection is always a possibility. Infection can still occur. The patient would need lifelong immunosuppression.

But he survived the transplant. He recovered. He had lungs again.

More importantly, he had lungs that were transplanted into a patient who had already survived 48 hours of complete artificial lung support. The physiological stress of being connected to the TAL system for two days is itself a massive insult. Yet the team kept him stable through it. That speaks to the robustness of the design.

What This Means for Future Cases

This case creates a new pathway for patients who would previously have been considered unsalvageable. Anyone with bilateral necrotizing lung infection can now, theoretically, be saved by removing the infected lungs and connecting to a custom artificial lung system.

But building a custom device for each patient is expensive and time-consuming. It required weeks of engineering work before the surgery. It required a team of biomedical engineers, surgeons, and ICU specialists working in coordination.

The next step is standardization. Can the lessons learned from this custom device be applied to create a generalized artificial lung system that could be deployed more quickly and used for more patients?

There's also the question of how long you can actually support a patient this way. This case was 48 hours. Could you do a week? Could you do a month? What are the physiological limits of artificial lung support in the absence of any native lung function?

Researchers at Northwestern and other institutions are now investigating these questions. The hope is that this becomes not a desperate last-ditch effort but a recognized clinical tool. A way to bridge patients from overwhelming acute infection to transplantation, something that currently kills many people who would otherwise be good candidates.

The Technical Challenges Still Remaining

Despite the success of this case, artificial lung technology still faces major hurdles.

Long-term biocompatibility is one. The more time blood spends in contact with artificial surfaces, the more protein deposits build up. These deposits can impair gas exchange. They can trigger inflammatory responses. They can cause systemic problems.

Height and weight scaling is another. The device used for this patient was engineered specifically for his size and physiology. Scaling it for larger or smaller patients requires redesign. A truly clinical artificial lung system needs to be available in multiple sizes, or needs to be adaptable to different patient sizes.

Then there's the issue of mobility. A patient on ECMO typically can't move much. Can someone on long-term artificial lung support be mobilized? Can they stand? Can they walk? If the goal is to bridge from acute illness to transplant, being able to mobilize the patient accelerates recovery.

And there's the practical issue of setup time. This custom device took weeks to engineer. No surgeon can wait weeks for a patient with acute septic shock to deteriorate. The engineering would need to happen in parallel with the decision to operate, or the device would need to be standardized and kept ready.

Comparison With Other Artificial Lung Approaches

There are other artificial lung systems in development around the world. The Xcur Therapeutics ALung system is a pumpless artificial lung that uses the patient's native heart pressure to drive blood flow. The idea is elegant: use the mechanical energy your heart already generates, just passing it through an oxygenator instead of through your lungs.

But pumpless systems have limitations. They depend on the heart being able to generate enough pressure, which this patient's failing heart could not do. They have lower flow rates and lower oxygenation capacity. For acute, unstable patients, they're less suitable than a pumped system like the TAL.

Then there are traditional ECMO systems, which work well but have the problems we've already discussed. And there are Bi VACOR total artificial hearts, which replace both the lungs' gas exchange function and the heart's pumping function, but they're designed for different indications.

What makes the Northwestern TAL system special is that it was designed specifically for the problem of bilateral pneumonectomy. It solved a very specific physiological puzzle that previous systems hadn't addressed.

The Future of Acute Respiratory Failure Treatment

If this type of artificial lung support becomes standardized and more widely available, it could change how acute respiratory distress syndrome is treated.

Currently, if your lungs fail from overwhelming infection or trauma, your options are limited. You can try mechanical ventilation and hope your lungs recover. If they don't, and if you're a candidate, you might eventually get a lung transplant. But transplant candidacy requires a certain level of clinical stability. You can't be in active septic shock. You can't have multiple organ failure. Many patients die while waiting to meet eligibility criteria.

An accessible artificial lung system could change this equation. If you're too sick for transplant, but your lungs are beyond recovery, you could have them removed and be supported by artificial lungs while you recover from acute illness. Once you've stabilized, once the infection has cleared, you could receive a transplant.

This is a fundamentally different approach to the problem. Instead of waiting for the patient to recover enough to be a transplant candidate, you treat the acute illness while supporting life artificially, then transplant when the patient is stable.

For patients with necrotizing infections, trauma, or massive aspiration that destroys both lungs, this could be life-saving.

Ethical Considerations and Medical Decision-Making

This case also raises important questions about how we make decisions in the face of zero traditional options. This patient was dying. Every option available under standard protocols would lead to death. So the team chose to try something that had never been done before.

Was this ethical? I'd argue yes. The alternative was certain death. The experimental intervention offered a chance at survival. The patient (or their family, if the patient couldn't consent) understood the experimental nature and the risks involved.

But it raises a broader question: how do we decide when to try experimental approaches? There's a natural hesitation. What if the artificial lung system had failed? What if the patient had clotted massively during the procedure? What if the hemodynamic stress of the surgery had caused catastrophic bleeding?

These risks were real. The surgery could have gone horribly wrong. But the team proceeded because the certainty of death without intervention outweighed the risk of experimental intervention.

This is how medical progress actually happens. Someone says, "What if we try this?" Someone else says, "That's never been done." And a brave patient or patient family says, "We understand the risks. Let's try." And sometimes it works.

Long-Term Viability and Clinical Adoption

For this technology to become standard clinical practice, several things need to happen.

First, the system needs to be simplified enough that it can be deployed at major transplant centers without requiring weeks of engineering work for each patient. This might mean creating modular components that can be assembled quickly, or developing sizing guidelines that allow a standard system to be adapted to different patients.

Second, there needs to be research on longer-term support. How long can someone survive on artificial lung support? What are the physiological limits? What complications emerge after a week, two weeks, a month?

Third, outcomes data needs to accumulate. Right now, there's one case. One success. That's amazing, but it's anecdotal. To move this into standard clinical practice, you need multiple cases with consistent positive outcomes.

Fourth, there's the economic question. Custom engineering is expensive. Hospital systems need to figure out how to afford this technology and how to integrate it into their transplant programs.

All of these are solvable problems. They're not insurmountable obstacles. But they're the bridge between "one successful experimental case" and "new standard treatment option."

What This Tells Us About Medical Innovation

The story of this artificial lung system tells us something important about how medicine advances. It doesn't advance through incremental improvements to existing systems. It advances when someone faces an impossible problem and decides to solve it from first principles.

The standard approach to bilateral lung disease is sequential transplant. That's what the playbook says. But this patient couldn't fit into that playbook. His disease was too acute, too severe. So rather than abandon him, the team looked at the fundamental physics of the problem and engineered a solution.

They didn't try to force the patient into the existing protocol. They created a new protocol specifically for his situation.

That's real innovation. That's how medicine actually progresses.

Key Takeaways and Clinical Implications

Let's summarize what happened and why it matters.

A 33-year-old man with necrotizing bilateral pneumonia from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and influenza was admitted to Northwestern University Hospital in septic shock. Standard treatment options would have led to death because his lungs needed to be removed to stop the source of infection, but removing both lungs simultaneously creates a hemodynamic crisis that historically has been fatal or unfeasible.

The surgeons, led by Dr. Ankit Bharat, designed a custom artificial lung system called the TAL (total artificial lung). This system included novel components like a dual-lumen cannula for unloading the right ventricle, a flow-adaptive shunt to prevent pressure buildup, and careful positioning of the return cannula in the ascending aorta to avoid peripheral pressure spikes.

The system kept the patient alive for 48 hours without any native lung function. During this time, sepsis cleared, organ function improved, and he became a viable candidate for double lung transplant. The transplant was successful.

This case demonstrates that bilateral pneumonectomy is now survivable with the right technology. It opens the door to treating patients with necrotizing bilateral lung infection who would previously have been written off as unsalvageable.

The next steps are standardizing the technology, researching longer-term support capabilities, and accumulating outcomes data. If this becomes widely adopted, it could save the lives of patients with catastrophic bilateral lung disease.

FAQ

What is bilateral pneumonectomy and why is it so dangerous?

Bilateral pneumonectomy is the surgical removal of both lungs. It's dangerous because the lungs serve not just as gas-exchange organs but also as pressure buffers for the right side of the heart. When removed, the right ventricle has nowhere to pump its blood, pressure spikes dramatically, and the heart collapses within minutes without support. This is why it's been considered one of the most dangerous surgical procedures.

How does the custom artificial lung system differ from regular ECMO?

The custom TAL system uses specialized components designed specifically for bilateral pneumonectomy: a dual-lumen cannula that unloads the right ventricle directly, a flow-adaptive shunt that prevents pressure buildup, and positioning of the return cannula in the ascending aorta rather than a peripheral vessel. Regular ECMO wasn't designed to handle the unique hemodynamic challenges created by the complete absence of native lungs, making it unsuitable for prolonged bilateral pneumonectomy support.

Why couldn't the surgeons use sequential lung transplant for this patient?

Sequential transplant requires replacing one lung, letting it establish circulation, then replacing the second lung over time. However, this patient's lungs were necrotizing from severe Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. The infection was actively destroying lung tissue and generating sepsis. He needed his lungs removed immediately to stop the source of infection, and he didn't have days or hours to wait for sequential replacement. Bilateral pneumonectomy followed by immediate TAL support was the only approach that could save him.

What is acute respiratory distress syndrome and why was this patient's case so severe?

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a condition where inflammation and fluid damage the lungs, preventing oxygen from entering the blood. This patient had a severe necrotizing form where the bacteria and immune response were actively killing lung tissue, turning the lungs into non-functional fluid. This wasn't just inflammation that could be treated with ventilation—the lungs themselves were dying and had to be removed entirely.

How long can a patient survive on artificial lung support without any native lungs?

This case demonstrated 48 hours of successful support, but longer-term capabilities remain unknown. The longest published survival on artificial lung support is several months, but those patients typically had some residual native lung function or were supported differently. Research is ongoing to determine whether the TAL system could support a patient for days or weeks, which would expand its clinical applicability significantly.

What anticoagulation therapy was required to prevent blood clotting?

When blood circulates through artificial devices for extended periods, clotting becomes a major risk. The patient would have been on aggressive anticoagulation therapy, likely including heparin infusions to prevent clot formation inside the artificial system and blood vessels. The medical team would have monitored clotting studies constantly and adjusted anticoagulation levels in real-time to balance the risk of thrombosis against the risk of bleeding complications.

Could this technology be used for other conditions besides severe infections?

Potentially, yes. Any condition causing irreversible bilateral lung failure—massive trauma, chemical inhalation injury, acute aspirations—could theoretically be treated with bilateral pneumonectomy and TAL support. However, the technology would need to be standardized and more widely available before broader clinical application. Currently, it's still in the research and development phase for specialized cases.

What is Pseudomonas aeruginosa and why was it so difficult to treat?

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative bacterium that's particularly difficult to treat because many strains develop resistance to antibiotics. In this patient's case, the strain was resistant to carbapenems, which are antibiotics of last resort. This meant that antibiotic therapy alone couldn't control the infection—the infected lungs had to be removed entirely to eliminate the source of sepsis.

What happens to the right ventricle during the 48 hours of artificial lung support?

During artificial lung support, the right ventricle is significantly unloaded. Instead of pumping blood into resistant pulmonary vasculature and against pressure buildup, the right ventricle ejects blood into the low-resistance right atrium through the flow-adaptive shunt. This dramatically reduces the workload on the right ventricle, prevents distension, and allows it to recover and stabilize. Essentially, the artificial system takes over the mechanical burden that the right ventricle would normally bear.

How could this technology be adapted for wider clinical use?

To become standard clinical practice, the TAL system would need to be simplified, modularized, and standardized in different sizes. Rather than custom-engineering each device for each patient, hospitals would need to develop assembly protocols and sizing guidelines. Additionally, training programs would be needed to teach surgeons and ICU specialists how to implant and manage the system, and regulatory approval from agencies like the FDA would be required for clinical use.

Related Articles

- Resident Evil Requiem Switch 2 microSD Card: Worth $140? [2025]

- Mark Zuckerberg's AI Social Media Vision: The Future of Meta's Content Strategy [2025]

- Best Android Phones [2026]: Top Picks for Every Budget

- Gmail Spam and Email Misclassification Issues: What Went Wrong [2025]

- Did Edison Really Make Graphene in 1879? Rice Scientists Found Out [2025]

- Best Travel Camera 2025: OM System OM-5 Mark II at Record-Low Price

![Artificial Lung Machine Kept Patient Alive 48 Hours Without Lungs [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/artificial-lung-machine-kept-patient-alive-48-hours-without-/image-1-1769708240814.jpg)