The Wild Discovery That Changed How We Think About Edison's Legacy

Thomas Edison gets credit for basically everything. The light bulb, electrical distribution, motion pictures, the phonograph—the man's name is synonymous with innovation itself. But what if I told you he might have accidentally created one of the most promising materials of the 21st century without even knowing it existed?

That's exactly what researchers at Rice University discovered when they decided to recreate Edison's original 1879 light bulb experiments using modern analytical tools. The result? Parts of his carbon filaments had transformed into graphene—the same material that earned physicists Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov a Nobel Prize in Physics back in 2010 for its revolutionary properties.

Let me be clear: Edison didn't intentionally make graphene. He couldn't have. Graphene wasn't formally identified and synthesized until the 2000s, well over a century after Edison was tinkering with carbonized bamboo filaments. But this discovery reveals something deeper about how scientific progress works. Sometimes the most important breakthroughs hide in plain sight, waiting for someone to look at old problems through new lenses.

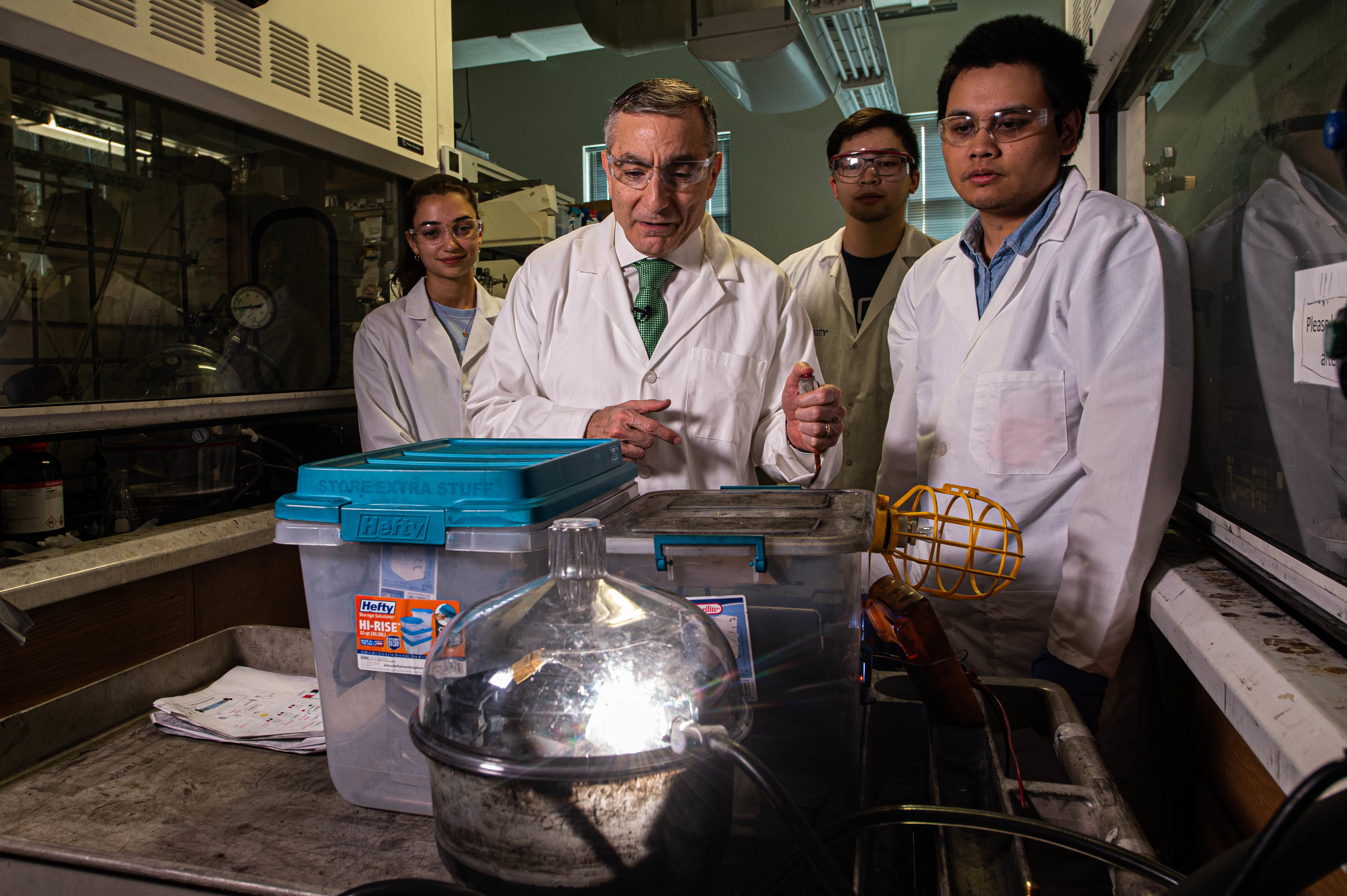

The story starts with a graduate student named Lucas Eddy at Rice University who was trying to solve a modern problem: how to mass-produce graphene using equipment that's affordable, accessible, and practical. His journey led him down a fascinating rabbit hole into 19th-century engineering, and what he found there has implications for how we approach materials science today.

Understanding Graphene: Why This Material Matters

Before we dig into Edison's accidental discovery, let's establish what graphene actually is and why scientists have been so excited about it for the past 15 years.

Graphene is fundamentally different from anything most of us encounter in daily life. It's a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice pattern, kind of like a two-dimensional sheet of chicken wire made entirely of carbon. When you're talking about a single layer of atoms, you're at the absolute edge of material physics. The thing is only about one-third of a nanometer thick—roughly 100,000 times thinner than a human hair.

Now, thinness alone wouldn't make graphene special. What makes it remarkable is what that atomic structure actually does. Graphene is stronger than steel at a fraction of the weight. It conducts electricity better than copper. It conducts heat better than diamond. It's transparent yet dense enough to block the smallest gas molecules. The list of unusual properties just keeps going.

These characteristics open doors to applications that seemed impossible a decade ago. We're talking about flexible electronics that don't crack when you bend them. Battery technology that could give your phone weeks of charge instead of days. Water purification systems that could remove contaminants and salt with unprecedented efficiency. Touch screens that are thinner and more responsive. Solar cells with dramatically improved conversion rates. Transistors that could keep Moore's Law alive when traditional silicon-based computing hits its physical limits.

The physics community recognized the potential immediately. When Geim and Novoselov demonstrated how to isolate single-layer graphene using the surprisingly low-tech method of scotch tape and graphite, their work triggered a research explosion. Universities, corporations, and government agencies worldwide started pouring money into graphene research. The material appeared on lists of transformative technologies alongside AI and quantum computing.

But here's the catch: making graphene at scale is genuinely difficult. The scotch tape method works great in a lab for research purposes, but it doesn't scale to industrial production. Other methods require expensive equipment, high temperatures, and specialized conditions. This is where Lucas Eddy's thinking diverged from conventional approaches.

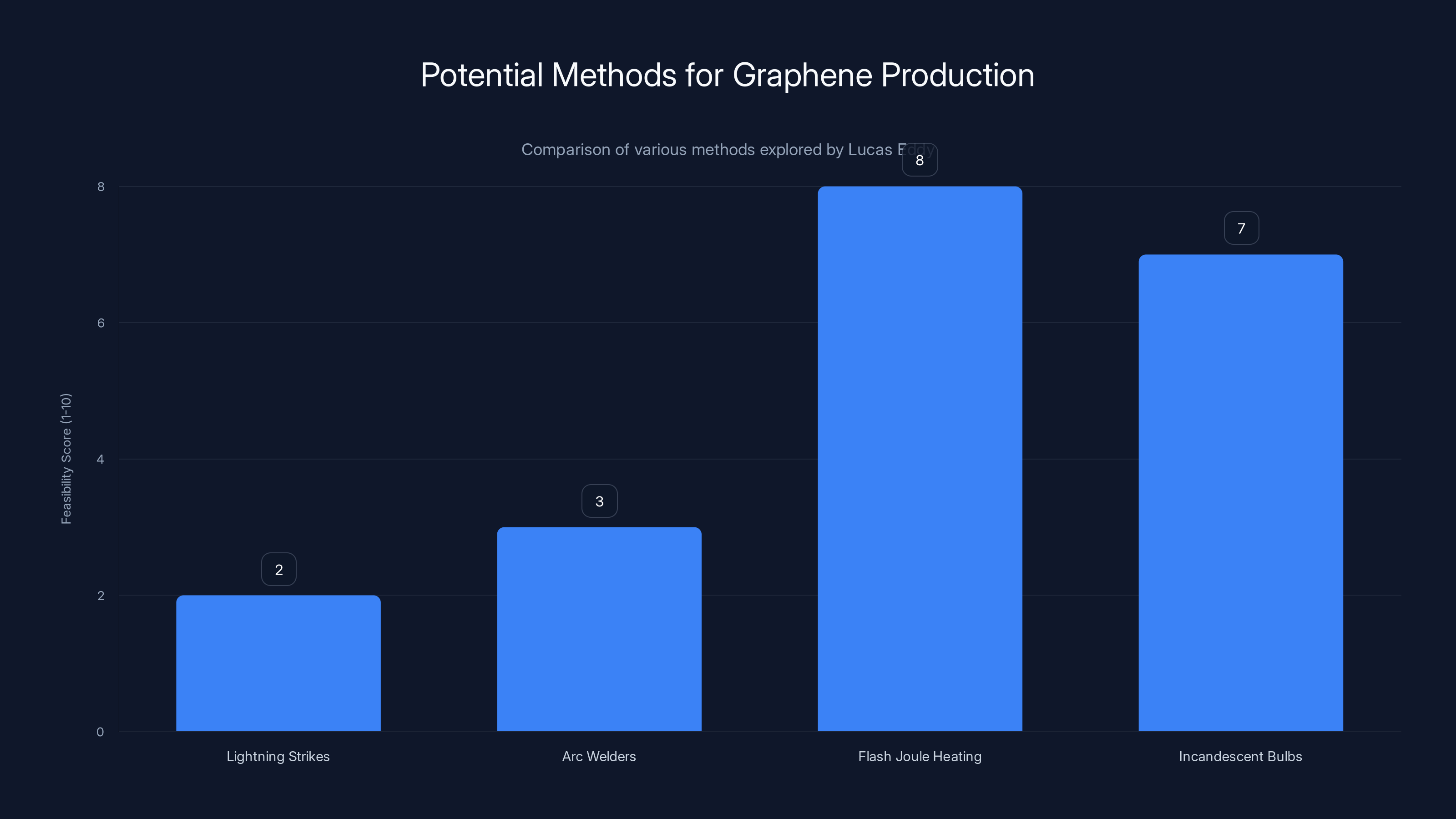

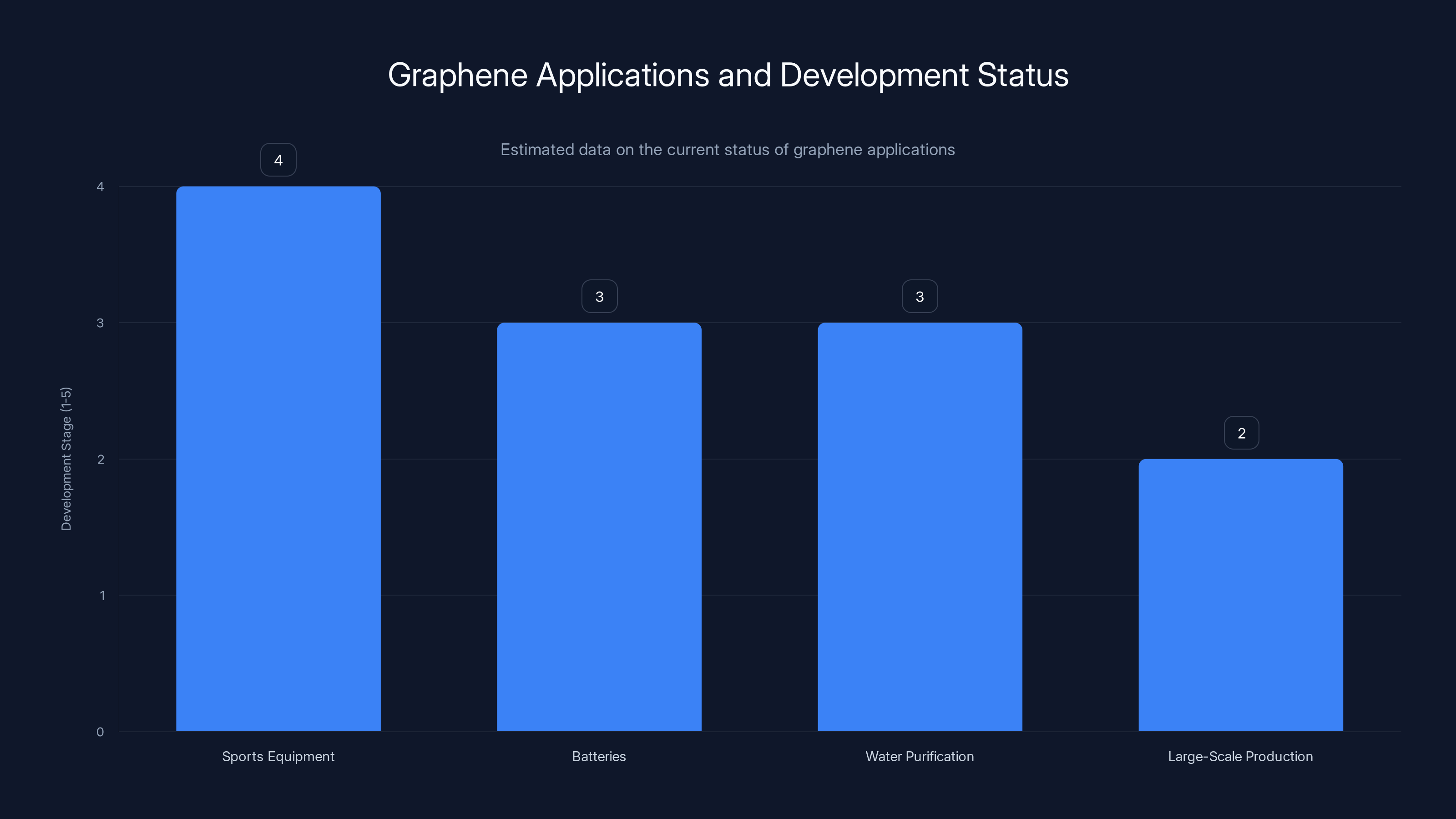

Flash Joule Heating emerged as the most feasible method for accessible graphene production, scoring highest in feasibility due to its ability to reach necessary temperatures using common materials. (Estimated data)

The Quest for Accessible Graphene Production

Lucas Eddy wasn't trying to reinvent materials science. He was trying to solve a practical problem with constraints. At Rice University's labs, he started asking himself: what if we could make graphene using equipment that already exists? What if we could use materials that are cheap and accessible? What if we didn't need million-dollar laboratories and specialized facilities?

He explored some creative avenues. Lightning strikes in trees can generate temperatures exceeding 30,000 Kelvin, way hotter than anything needed for graphene production. Could he harness that? He looked into arc welders, which can also reach extreme temperatures and are relatively common in industrial settings. Both paths became dead ends, though not before he'd spent considerable time and effort on them.

Then Eddy thought about the flash Joule heating method. This technique heats carbon-based materials extremely rapidly to temperatures between 2,000 and 3,000 degrees Celsius for brief moments. That rapid heating converts amorphous carbon into turbostratic graphene—a form with few structural defects and excellent electrical properties. The catch is you need a heat source that can reach and maintain those temperatures consistently.

What historical heat source could achieve that? Eddy's mind went back to Edison's work. He knew that Edison's incandescent light bulbs operated at around 2,000 to 3,000 degrees Celsius when lit. The bulbs achieved those temperatures by passing electrical current through a carbon filament. If you could precisely control the power and timing, you might be able to trigger the same flash Joule heating that modern materials scientists use to create graphene.

This is where the project got genuinely clever. Eddy accessed Edison's original 1879 patent documentation, which detailed the inventor's experimental process and specifications. He then obtained the actual patent itself and studied it methodically. What materials did Edison use? What were the exact dimensions? What voltage and current did his experiments employ?

Armed with that historical data, Eddy decided to replicate the experiment using modern analytical equipment to see what Edison might have actually created without knowing it.

The Experimental Setup: Replicating Edison's 1879 Work

Reproducing historical experiments is trickier than it sounds. You need period-accurate equipment or reasonable approximations of it. You need to understand the constraints and materials that were available at the time. You need to know whether the person conducting the original experiment documented everything accurately or if they omitted details that seemed obvious to them but are obscure to modern researchers.

Eddy's approach was methodical. He studied Edison's patent documentation, which specified that the inventor used carbonized bamboo filaments approximately 5 to 10 micrometers in diameter. These filaments were placed inside glass bulbs at specific spacing to maximize light output while avoiding internal arcing.

The original experiments operated on a 110-volt power supply, which was becoming standardized in Edison's time. When Edison activated the filament, current flowed through the carbon material, heating it to incandescence. The resistance of the carbon generated the extreme heat needed for illumination.

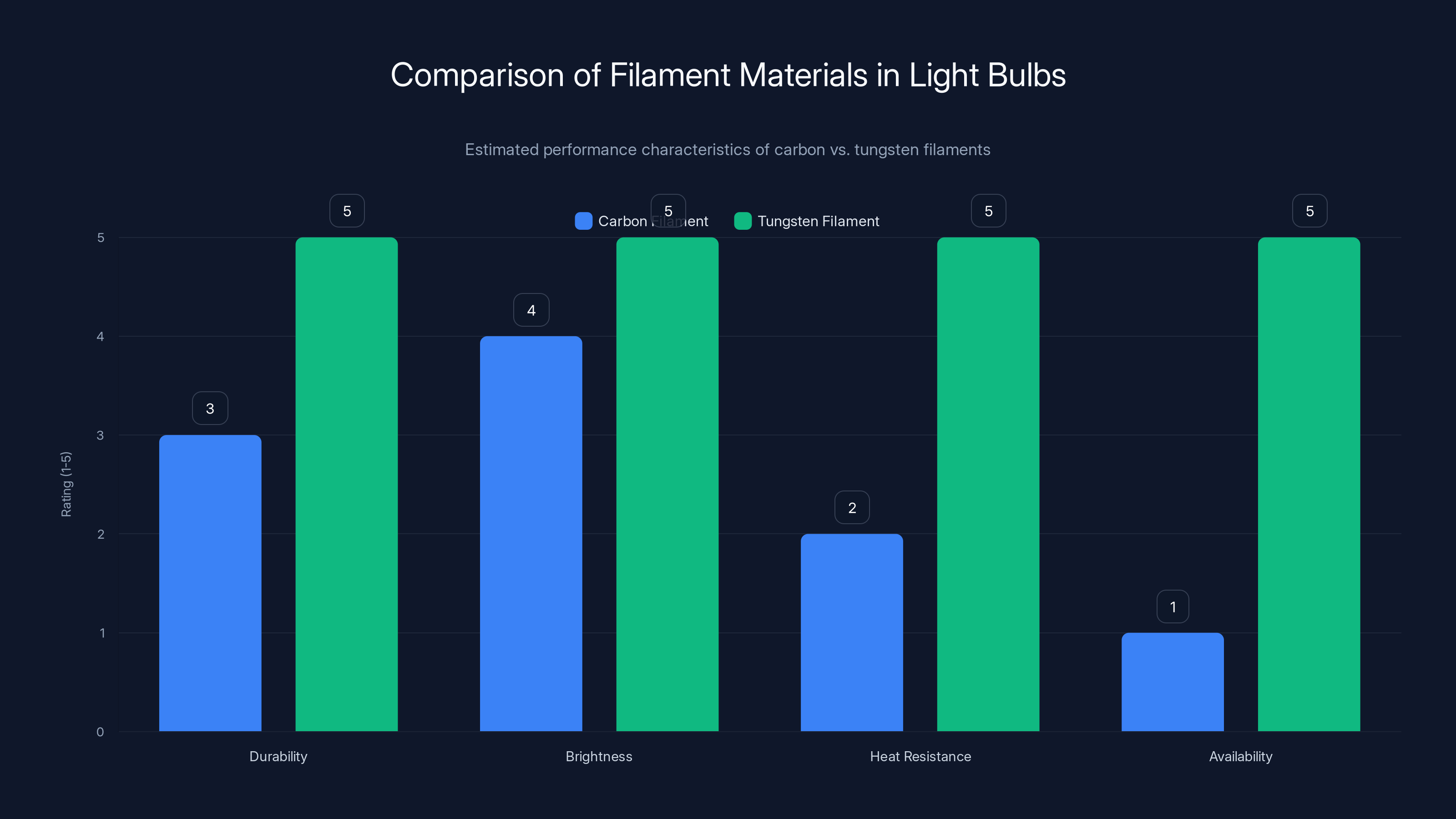

Eddy set up his replication with modern-day Edison-style light bulbs connected to a 110-volt power source. Here's where things got complicated: most contemporary light bulbs don't actually use carbon filaments anymore. The industry switched to tungsten filaments decades ago because tungsten lasts longer and reaches higher brightness levels. Tungsten has completely different properties than carbon, so it wouldn't produce the same results.

Eddy's first attempts failed not because his methodology was wrong, but because his light bulbs were the wrong material. He needed authentic carbon filament bulbs, the kind Edison originally used. These aren't sold in regular stores. They're specialty items, retro-style decorative bulbs that hobbyists and engineers occasionally track down.

Eventually, Eddy found a small art supply store in New York City that sold handmade, artisan Edison-style light bulbs with actual bamboo filaments. The filaments were approximately 5 micrometers larger in diameter than Edison's originals, but close enough to serve as a reasonable approximation for the experiment.

Estimated data suggests that reproducibility and documentation are rated highest in importance, closely followed by interdisciplinary approaches and systems thinking.

The Critical Moment: Activating the System

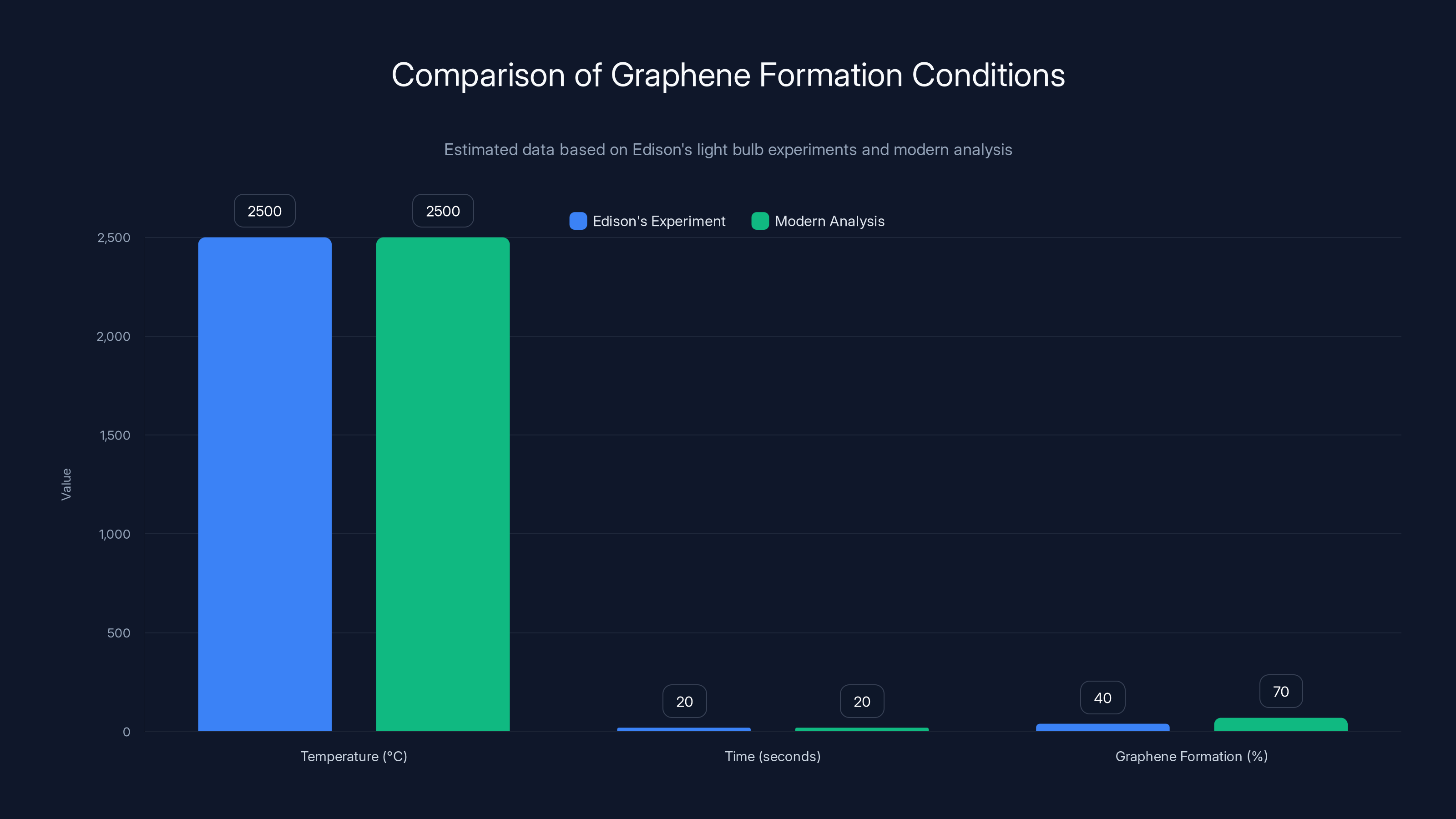

With the correct components in place, Eddy connected the artisan bulbs to the 110-volt power supply and activated them. This is where precision becomes absolutely critical. You need to heat the carbon filament to the right temperature range—above 2,000 degrees Celsius to trigger the transformation—but not so high or for so long that the carbon simply combusts entirely or transforms into graphite instead of graphene.

Eddy's solution was to switch the power on for exactly 20 seconds at a time. That duration proved crucial. Twenty seconds delivered enough energy to heat the carbon filament into the desired temperature range. Leave it on any longer, and you get graphite, which is a different form of carbon—more stable, more familiar, but not what the researchers were looking for.

The process is called flash Joule heating because the heating happens extremely rapidly through the resistance of the electrical current. As Joule's law tells us, the heat generated equals the electrical current squared multiplied by the resistance:

What Eddy observed when he examined the filaments after the heating process stopped was remarkable. The carbon filament had changed appearance. It now had a lustrous, silvery sheen instead of the dull black of raw carbon. Something had fundamentally shifted in the material's structure.

The Analytical Breakthrough: Confirming the Transformation

Changed appearance isn't proof of anything in materials science. You need analytical data. Eddy employed two sophisticated analytical techniques to determine what had actually happened to the carbon filament.

First, he used Raman spectroscopy, a technique that analyzes how light scatters off a material's atomic structure. Different materials scatter light in characteristic patterns. Graphene has a distinctive Raman signature that trained researchers can recognize. When Eddy ran Raman spectroscopy on the heated filament, the results came back positive: parts of the filament had indeed transformed into turbostratic graphene.

The second analytical tool was transmission electron microscopy (TEM). This involves firing a beam of electrons through an extremely thin slice of the material and analyzing how those electrons interact with the atomic structure. TEM can resolve individual atomic layers and reveal the precise arrangements of atoms within a material. When Eddy examined the filament using TEM, he could literally see graphene layers interspersed among regions of unconverted amorphous carbon.

The before-and-after TEM images told a compelling story. The original filament showed the typical structure of carbonized bamboo—a somewhat chaotic arrangement of carbon atoms with no particular order. After the 20-second heating cycle, clear layers of organized atomic structure appeared—the characteristic arrangement of graphene. Not the entire filament had transformed, which is actually realistic. Some regions underwent the conversion; others remained as amorphous carbon. But the evidence was unmistakable.

Why Edison Couldn't Have Known About His Discovery

Now here's the important caveat: this discovery doesn't mean Edison was secretly a materials scientist ahead of his time. Let's be clear about the limitations of what Edison could have known and observed in 1879.

First, graphene didn't exist as a recognized material concept in 1879. The term "graphene" wasn't coined until the 1980s, and it wasn't formally isolated and characterized until the 2000s. Edison couldn't have been looking for something that hadn't been discovered or named.

Second, even if Edison had somehow suspected that his filaments were undergoing an interesting transformation, he lacked the tools to detect it. Raman spectroscopy wasn't invented until 1928. Transmission electron microscopy came even later. In 1879, Edison's analytical capabilities were limited to basic optical microscopy and visual inspection. Looking at a silvery residue in a light bulb without modern equipment would tell you almost nothing about its atomic structure.

Third, any graphene that might have existed in Edison's original bulbs would have long since degraded. Graphene in air gradually oxidizes and converts to other forms of carbon. After more than 140 years, if you examined one of Edison's original bulbs today, you'd find graphite, not graphene. The atomic transformation happens over time.

So this research isn't suggesting Edison discovered graphene. Rather, it's suggesting that the process Edison developed—heating carbon filaments to specific temperatures—inadvertently created graphene as a temporary byproduct. Modern tools can detect and verify what the historical experiment actually produced, even though no one noticed at the time.

Edison's original experiments unintentionally created graphene under specific conditions. Modern analysis shows a higher potential for graphene formation. (Estimated data)

The Broader Implications: Looking at History Through Modern Eyes

What makes this finding genuinely interesting isn't that Edison made graphene. It's what this discovery reveals about scientific progress and how we approach historical innovations.

There's a fundamental principle at work here: history is written by the questions we ask. When Edison was experimenting with carbon filaments, his question was simple: "How can I make a light bulb that lasts a reasonable amount of time?" He optimized for durability and brightness. He wasn't asking about the atomic structure of carbon or what materials might be forming during the heating process.

But when Lucas Eddy asked his question—"How can we produce graphene using simple, accessible equipment?"—it led him to revisit Edison's experiment through a completely different lens. The equipment Edison used, the temperatures he achieved, the materials he employed—all of these elements suddenly became relevant to a question that wouldn't be asked for another century.

This pattern shows up throughout the history of science. X-rays were discovered by accident. Penicillin grew in a contaminated petri dish. Cosmic microwave background radiation was detected by scientists trying to eliminate noise from their radio antenna. Post-It notes came from a failed attempt to make super-strong adhesive. Sometimes the most important discoveries emerge when we approach old problems with new questions and new tools.

The Rice University team acknowledged this explicitly in their research. They noted that other early technologies might contain similar hidden materials or reactions that went unnoticed. Vacuum tubes, arc lamps, early X-ray tubes—all of these operated at extreme temperatures or under unusual conditions. Did they accidentally create materials that weren't recognized at the time? Did they trigger chemical reactions that left traces in the equipment? We might not know until someone asks the right question decades or centuries later.

Graphene's Real-World Applications: Why This Matters Now

While the Edison connection is a fun historical curiosity, the broader significance lies in graphene's actual applications. Understanding how to produce graphene through flash Joule heating in light bulbs could have practical implications for modern manufacturing.

Graphene has already transitioned from pure research material to applications in development. Some companies are incorporating graphene into sports equipment—tennis rackets, bicycles, and golf clubs that are lighter and stronger than conventional materials. Others are exploring graphene-enhanced batteries for electric vehicles and portable electronics. Graphene-based water purification systems are moving toward commercialization in some markets.

But large-scale production remains a bottleneck. Most current manufacturing methods require specialized equipment and conditions that keep costs high. If you could produce graphene using equipment as simple as a light bulb and a standard electrical outlet, that changes the economics significantly.

The flash Joule heating method that Eddy demonstrated is actually one of the more promising approaches for scaling graphene production. It's faster than many alternative methods, it uses less energy for the actual heating phase, and it produces graphene with good structural properties. The challenge has been finding the right equipment configuration to make it accessible and cost-effective.

Edison's light bulb, it turns out, is actually a surprisingly elegant solution. It delivers precise heat through electrical resistance. It confines that heat to a small volume. It allows for repeatable, controllable heating cycles. In some ways, Edison's design is almost perfectly optimized for this application, even though he had no idea.

Turbostratic Graphene vs. Other Forms: What's the Difference?

Not all graphene is created equal, and this is where the technical details matter. When researchers talk about graphene, they're usually referring to perfect, defect-free, single-layer graphene. That's the structure that won Geim and Novoselov the Nobel Prize.

But graphene exists in several variants, and they have different properties. Turbostratic graphene is what Eddy found in the Edison filaments. It's characterized by stacked graphene layers with random rotations relative to each other—hence "turbostratic." This gives it different electrical properties than perfect graphene, but different doesn't mean worse. It just means different.

Turbostratic graphene actually has some practical advantages. It's more straightforward to produce. It's often more stable than perfect graphene in certain applications. And it can exhibit different electrical and thermal properties that make it useful for specific applications where perfect crystalline graphene might be overkill.

The presence of structural defects, which turbostratic graphene contains, affects how electricity moves through the material. It changes how heat conducts. It can actually improve certain properties for some applications. Engineers have learned that a material doesn't need to be perfect to be useful—it needs to be right for the specific job.

This is another reason why finding turbostratic graphene in Edison's experiment is more interesting than just a curiosity. It shows that flash Joule heating at the temperatures Edison's filaments reached produces a graphene variant that has practical applications. You don't necessarily need to create perfect graphene for every use case.

Tungsten filaments outperform carbon in durability, brightness, and heat resistance, making them the industry standard. Estimated data based on historical and modern comparisons.

The Historical Context: Why Edison Deserves the Recognition

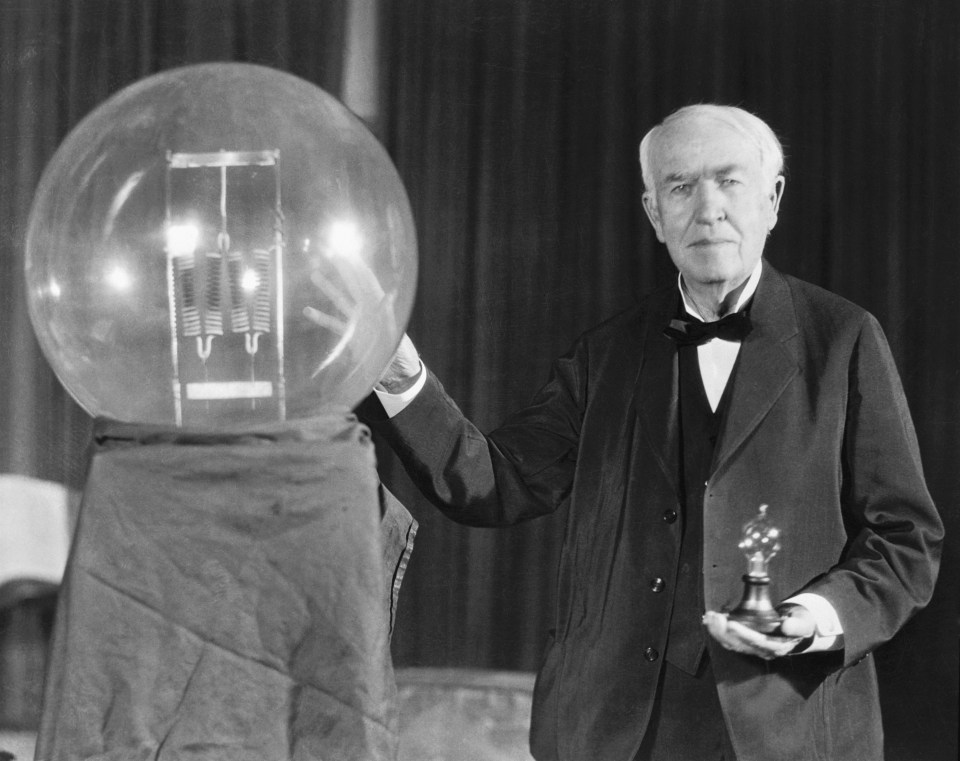

Let's take a moment to appreciate what Edison actually accomplished with his carbon filament light bulb, setting aside the accidental graphene creation.

Before Edison's work, incandescent lighting existed in various forms, but none were commercially viable. Joseph Swan in Britain had developed a working light bulb, but the filaments burned out quickly and required dangerous levels of electrical current. Other inventors had tried different materials—platinum, carbon, various metals—but nothing lasted long enough or worked reliably enough for widespread use.

Edison's insight was to test carbonized materials systematically. He eventually discovered that carbonized bamboo could produce filaments that lasted over 1,200 hours on a 110-volt circuit. That's not just a modest improvement—that's a fundamental shift in practical viability. A light bulb that lasts 1,200 hours meant you could actually install lighting systems in homes and buildings without constantly replacing failed bulbs.

Beyond the filament itself, Edison developed the distribution system that made widespread electrification possible. He understood that a single brilliant light source wouldn't transform society. You needed an entire ecosystem: generators, wiring infrastructure, customer systems, safety mechanisms. Edison built the first central power station and distribution network in lower Manhattan. He thought about the problem as a complete system, not just the light bulb.

This systems-thinking approach was revolutionary. Edison didn't just invent a product; he created an industry. That's the aspect of Edison's legacy that matters most. The accidental graphene creation is a neat footnote, but Edison's real achievement was understanding that innovation requires thinking about how everything connects.

How Modern Researchers Discovered This Historical Secret

The Rice University team's research methodology deserves attention because it represents a broader trend in science: revisiting historical work with modern tools.

Their paper, published in Nature, walked through their process methodically. They described how they located Edison's original patent documentation. They explained how they sourced materials that approximated Edison's original components. They detailed the experimental setup, the heating protocol, and the analytical techniques.

This transparency matters because it allows other researchers to replicate, verify, or extend the work. It's how science actually progresses—through reproducibility and refinement. The Rice team made their methodology clear enough that if someone wanted to test their conclusions, they could do so.

The research also prompted a broader conversation about revisiting historical experiments. James Tour, the senior researcher on the project, posed a thought-provoking question in the paper's conclusion: what would our scientific forefathers ask if they could work in modern laboratories? What answers could we find by reexamining their work through contemporary analytical lenses?

This approach has already yielded results in other fields. Historians of science have reexamined historical chemical experiments, historical astronomical observations, and historical medical treatments through modern methodologies. Sometimes they find that early researchers were more accurate than we thought. Sometimes they uncover errors that went unnoticed for centuries. Always, they gain new insights by asking different questions.

The Technical Challenge: Why 20 Seconds Matters

One detail from the Rice University experiment deserves closer examination because it illuminates a crucial aspect of materials science: timing is everything.

Eddy discovered through trial and error that 20 seconds was the precise window. This isn't arbitrary. It's the result of balancing competing chemical and physical processes occurring at extreme temperatures in carbon material.

When you heat carbon to 2,000-3,000 degrees Celsius, multiple transformations become energetically possible. The atomic bonds weaken and break. Atoms gain enough thermal energy to rearrange themselves. At these temperatures, different crystal structures can form, and the kinetics of the transformation determine which structure dominates.

Graphene formation requires the carbon atoms to arrange themselves in the characteristic hexagonal pattern. But if you keep heating for too long, even more thermal energy enters the system. The atoms rearrange again, this time forming graphite, which is more thermodynamically stable at very high temperatures. Graphite is what you get if you keep pushing the temperature up or maintain it for extended periods.

The 20-second window is the Goldilocks zone. It's long enough to provide the energy needed for carbon atoms to reorganize into graphene structures. It's short enough that you don't provide enough additional thermal energy to trigger the graphite transformation. It's a narrow window, which is why timing precision matters so much.

This principle—that materials science often requires finding the narrow range of conditions where the desired outcome is thermodynamically and kinetically favorable—explains why making new materials is so challenging. You can't just blast something with energy and hope for the best. You need to understand the underlying physics and chemistry well enough to find the conditions where the material you want to create is actually the stable outcome.

Edison didn't need to understand this. His goal was to heat the carbon hot enough to produce light, not to optimize for a specific crystal structure. But the temperatures he achieved and the duration of the heating happened to fall into the range where graphene formation becomes possible. It was luck combined with physical necessity.

Graphene is most advanced in sports equipment applications, with significant progress in batteries and water purification. Large-scale production remains challenging. (Estimated data)

Implications for Modern Graphene Manufacturing

If Edison's light bulbs can inadvertently produce graphene, could they be used intentionally as part of a manufacturing process? That's the practical question researchers are now exploring.

The advantage of using light bulbs is simplicity and accessibility. A standard electrical socket, a light bulb, a power supply—these are components available in basically any location with electricity. Compare that to conventional graphene production methods, which often require specialized equipment costing tens of thousands of dollars.

The disadvantage is scale and efficiency. Each light bulb produces a tiny amount of graphene. The heating isn't uniform across the entire filament, so the graphene yield varies. Some of the electrical energy goes into producing light rather than into the structural transformation of carbon. It's not an optimal system from an efficiency standpoint.

Researchers are currently exploring whether they could modify the light bulb design to optimize for graphene production rather than light output. If you sealed the bulb completely, you could capture all the heat without light escape. If you used a different filament geometry, you might achieve more uniform heating. If you engineered the structure differently, you might improve the graphene yield.

These modifications move away from Edison's original design, but the fundamental principle remains: using electrical resistance heating in carbon material to achieve the flash Joule heating needed for graphene production.

Another promising direction involves scaling the principle. Could you create a larger system using the same principles? If you had an array of heating elements rather than a single light bulb, could you produce graphene in useful quantities? Some researchers believe the answer is yes, but the engineering challenges increase with scale.

Why This Discovery Matters for Innovation Culture

Beyond the specific finding about Edison and graphene, this research carries a broader message about how innovation actually works.

We tend to think of scientific breakthroughs as moments of genius—someone has a brilliant idea and executes it perfectly. The reality is messier. Breakthroughs often emerge from curiosity, from asking unconventional questions, from looking at familiar things through unfamiliar lenses.

Lucas Eddy wasn't trying to prove Edison was secretly a materials scientist. He was trying to solve a practical problem: how to make graphene without expensive equipment. That practical constraint led him to think about accessible heat sources. Edison's light bulb was accessible, historically documented, and operated at the right temperatures. Everything aligned.

This type of thinking—finding innovative solutions by connecting different domains and reconsidering conventional approaches—is how many breakthrough innovations emerge. Someone from field A borrows an idea from field B. Someone recognizes that an old solution might address a new problem. Someone questions an assumption that everyone else takes for granted.

Companies and research institutions that want to foster innovation often need to think about creating space for this kind of exploration. It's not efficient in the short term. It doesn't immediately produce outcomes. But it produces the kind of thinking that leads to discoveries like this.

Future Directions: What This Means for Materials Science

The Rice University team concluded their research by suggesting that their approach—reexamining historical experiments through modern analytical tools—could uncover surprising discoveries in other areas.

Vacuum tubes, for instance, operated at extreme temperatures and electrical potentials. The interactions between electrons, gases, and metal surfaces in vacuum tube environments might have produced unusual materials or triggered interesting chemical reactions. No one analyzed them at the atomic level at the time, but modern equipment could potentially reveal what actually happened inside these devices.

Arc lamps, which powered early street lighting and spotlight applications, also achieved extreme temperatures. The carbon electrodes that created the arc would have undergone transformations under those conditions. What materials formed? What reactions occurred? Did any unusual substances accumulate inside the lamp?

Early X-ray tubes exposed materials to intense radiation and electrical fields. The electrodes, the gas inside the tubes, the glass that contained them—all would have experienced conditions unlike anything in normal industrial processes. Might they have created materials with unusual properties?

These historical technologies represent a kind of accidental experimental apparatus. Their designers were optimizing for function, not investigating materials properties. But the conditions they created might have been uniquely interesting from a materials science perspective.

Re-examining these devices through modern analytical capabilities could potentially reveal surprises. It's a research approach that costs relatively little—you're analyzing historical artifacts using existing equipment—but could yield significant insights.

This methodology also applies beyond materials science. Historical engineering projects might reveal principles that modern engineers have forgotten. Historical chemical processes might contain insights that got lost when different approaches became dominant. Historical biological observations might be more accurate than later research suggested. There's value in systematically revisiting what our predecessors actually did, rather than relying on our assumptions about what they did.

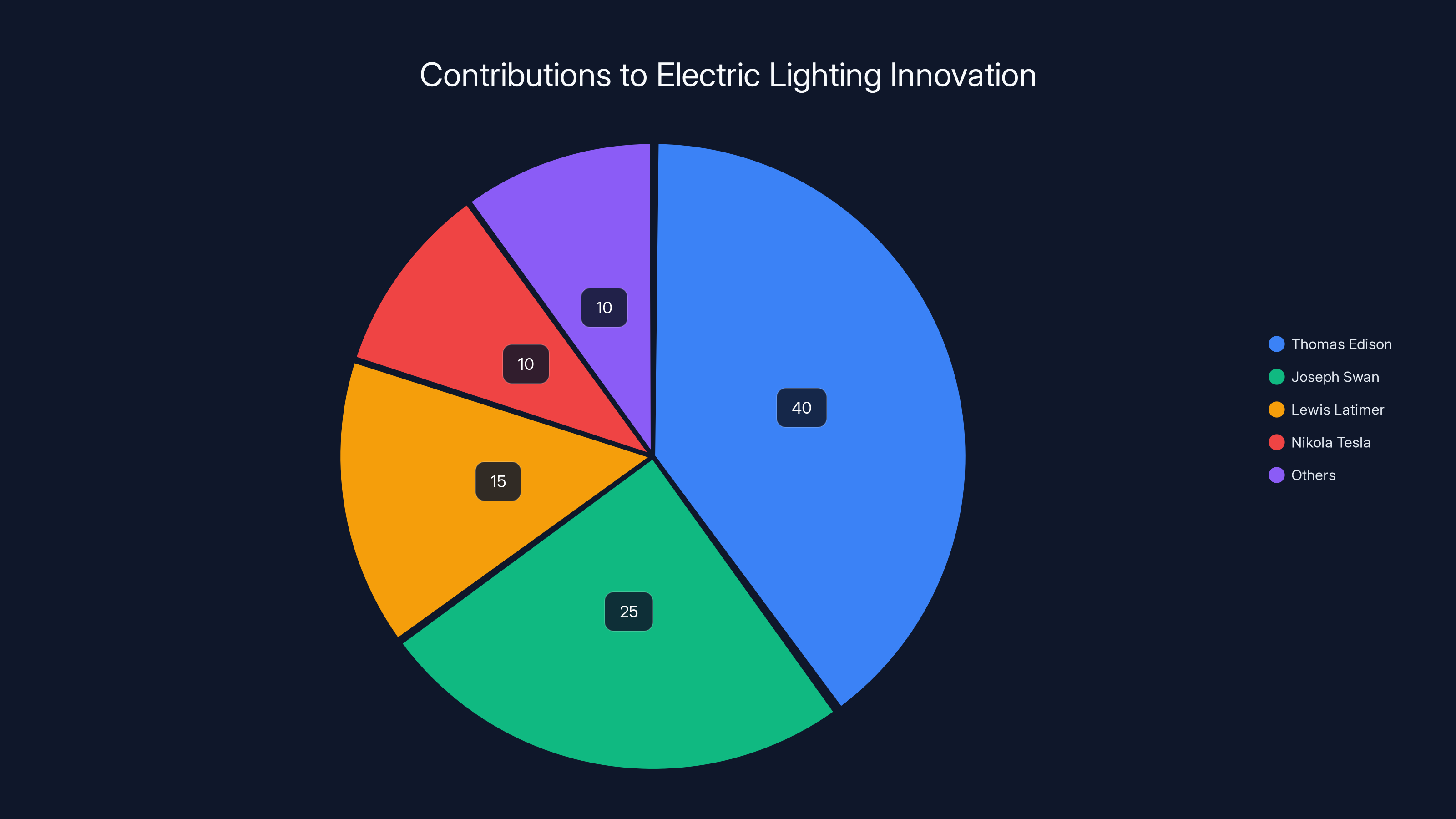

Estimated data suggests Thomas Edison had the largest share of contributions to electric lighting innovation, highlighting his role in historical memory.

The Edison Effect: How One Person Can Define a Whole Era

Thomas Edison's name has become almost synonymous with electrical innovation. When people think of the invention of electric lighting, they think of Edison. When people think of industrialization and practical innovation, Edison's name comes up. This happened despite significant contributions from other inventors—Joseph Swan, Lewis Latimer, Nikola Tesla, and others.

Why does Edison loom so large in historical memory? Part of it is genuinely his innovation—the carbonized bamboo filament was a breakthrough. But another significant part is Edison's understanding of publicity and public relations. He was brilliant at communicating his achievements. He created a laboratory that was itself designed to be impressive and symbolic. He told stories about his work that captured public imagination.

This is relevant to the graphene discovery because it shows how historical narratives get constructed. Edison's actual achievement was solving a systems problem: how to create practical electric lighting and the infrastructure to support it. But we remember him mainly for the light bulb itself.

Now, over 140 years later, we're discovering that Edison's light bulb was inadvertently creating materials that would become revolutionary in the 21st century. That's a delicious historical irony. But it also reminds us that our understanding of historical figures is always incomplete. They succeeded and failed in ways we don't fully understand, sometimes without even knowing the full significance of their own work.

Future generations might similarly discover unexpected aspects of work being done today. Someone in 2165 might recreate current experiments and find that we were inadvertently creating useful materials or triggering useful reactions without realizing it. The tools we use, the processes we optimize for, the conditions we create in pursuit of current goals—all of these might have implications we don't recognize.

Connecting the Threads: From Edison to Graphene to the Future

Let's step back and see how all these pieces connect.

Thomas Edison needed to solve a specific engineering problem in 1879: create a light bulb that lasts long enough to be commercially viable. His solution involved systematically testing carbon materials. He found that carbonized bamboo worked well. He didn't know that the temperatures his filaments achieved could create graphene, because graphene hadn't been discovered yet, and he lacked the tools to detect it.

Fast forward to the early 21st century. Scientists discovered graphene and recognized its revolutionary potential. Researchers worked to develop manufacturing methods to produce it in useful quantities. The challenge was that most methods required expensive, specialized equipment.

Fast forward a few more years to Rice University. A graduate student looking for accessible methods to produce graphene asks an unconventional question: could historical equipment achieve the right conditions? He researches Edison's experiments, discovers the specifications, and decides to replicate the work using modern analytical equipment.

The result: confirmation that Edison's process inadvertently created graphene. The discovery opens new possibilities for producing graphene through simpler, more accessible methods. It also illustrates a fundamental principle about scientific progress: sometimes the future lies in creatively reimagining the past.

This trajectory—from Edison's practical engineering to 21st-century materials science to potential future applications—shows how innovation builds on itself across centuries. The solution to today's problems often lies in understanding yesterday's approaches.

Practical Lessons: What We Can Learn From This Research

If you're involved in scientific research, engineering, product development, or innovation in any field, what lessons apply to your work?

First, the value of asking questions that bridge different domains. Eddy didn't approach this as a historian researching Edison. He approached it as a materials scientist looking for accessible solutions. The intersection of those perspectives yielded something neither would have found independently.

Second, the importance of reproducibility and documentation. Edison's work was valuable partly because he documented it thoroughly. Eddy could access and understand the original methodology because of that documentation. If you want your work to potentially inform future breakthroughs, document it clearly enough that someone could replicate it with future tools.

Third, the value of precision in specialized fields. Eddy's discovery came partly from paying attention to a seemingly small detail: heating for 20 seconds produced a different result than heating for longer or shorter periods. In many fields, these kinds of precise parameters matter tremendously. Documenting them carefully matters.

Fourth, the potential value in revisiting work that might seem solved or complete. Edison's work wasn't mysterious or unsolved. Everyone understood what he did and why. But looking at it through a modern lens revealed something unexpected. This principle applies across fields. Solved problems sometimes contain unexpected value when examined from new perspectives.

Finally, the importance of thinking in systems. Edison succeeded not just because he found a good filament material, but because he built an entire system: power generation, distribution, safety mechanisms, customer systems. Modern innovation often requires the same systems thinking. A great graphene production method isn't useful without considering how to scale it, integrate it into manufacturing, ensure safety, reduce costs, and create markets for the material.

The Broader Context: How We Approach Historical Science

This discovery is part of a broader trend in how contemporary science relates to historical work.

For much of the 20th century, the attitude was that older science was interesting mainly as historical context. We moved forward, we improved methods, we learned new things. Historical work served as a foundation, but the real action was in contemporary research.

But something has shifted. Scientists increasingly recognize that historical work contains information our predecessors couldn't extract with the tools available to them. A microscope from 1950 showed less detail than a microscope from 2025. A spectrometer from 1980 had less sensitivity than modern instruments. Historical samples might contain data that historical analysis couldn't detect.

This has led to surprising discoveries. Historical ice cores contain information about atmospheric composition that wasn't recognized when the cores were extracted. Historical soil samples contain pollen records that reveal climate patterns of ancient periods. Historical astronomical observations recorded accurate data that modern analysis can interpret differently than contemporary scientists did.

The Edison graphene discovery fits into this pattern. It's asking: what information do historical experiments actually contain, if we analyze them with contemporary tools? It's a question that leads to discoveries that couldn't have been made during the original work.

This approach also has epistemological implications. It suggests that science isn't purely about having the most advanced tools and newest theories. Sometimes the value comes from asking better questions about existing evidence. Sometimes progress means revisiting what we thought we understood.

Common Misconceptions About This Discovery

As this research gains attention, several misconceptions have emerged. Let me address them directly.

Misconception 1: Edison discovered graphene. He didn't. He created conditions where graphene could form, but he had no knowledge of it and no way to detect it. The discovery is modern. The accidental creation is historical.

Misconception 2: Edison's light bulbs could be used to mass-produce graphene commercially. Maybe eventually, but probably not in the near term. The yield is low, the process isn't optimized, and scaling presents significant engineering challenges. It's more valuable as a proof of concept and as a curiosity.

Misconception 3: This discovery completely changes our understanding of Edison's work. It doesn't, really. Edison's achievement was developing a practical light bulb and the systems to support it. The accidental graphene creation doesn't change that. It's interesting additional context, but not fundamental to understanding Edison's actual contributions.

Misconception 4: This proves that we have no idea what historical scientists actually achieved. Not quite. It shows that historical work sometimes contained interesting byproducts that weren't recognized at the time. But most historical work was analyzed fairly accurately within the context of available tools and knowledge. This is one interesting exception, not proof that everything has hidden depths.

Misconception 5: If Edison had better tools, he would have discovered graphene. Probably not. Edison was an engineer and inventor, not a materials physicist. Even with modern tools, he wouldn't have been trying to create graphene because he wouldn't have had a reason to. The discovery emerges from recontextualizing historical work in light of modern needs and knowledge.

What This Means for Your Field

Depending on your background, this research might apply differently to your work.

If you're in materials science or chemistry, the immediate relevance is potential. Flash Joule heating through simple equipment might offer a scalable graphene production method. This affects research direction, potential commercialization strategies, and the feasibility of graphene-based applications.

If you're in history of science or history of technology, the relevance is methodological. It demonstrates the value of systematically reexamining historical experiments through modern analytical capabilities. It suggests that significant discoveries might emerge from this kind of work.

If you're in innovation, product development, or engineering, the relevance is philosophical. It shows how examining problems from unconventional angles—drawing on historical approaches, connecting different domains, questioning conventional wisdom—can lead to breakthroughs.

If you're in education, the relevance is pedagogical. It shows students that science isn't just about the cutting edge. Sometimes understanding what happened in the past, examined through contemporary methods, produces genuine insights.

If you're in business or entrepreneurship, the relevance is strategic. It suggests that existing solutions to old problems might be repurposed for new challenges. It shows how maintaining perspective on historical approaches, rather than always discarding them for newer methods, can yield competitive advantages.

The Spirit of Inquiry: Why This Discovery Matters Beyond Materials Science

What makes this discovery genuinely exciting isn't just the technical finding. It's the spirit of inquiry it represents.

Lucas Eddy asked a question that broke conventional categories. He wasn't a historian studying Edison. He wasn't purely a materials scientist pursuing graphene. He was a problem-solver asking how past solutions might inform present challenges. That's the kind of thinking that produces breakthroughs.

The research also demonstrates something important about scientific culture: the value of curiosity that doesn't have immediately obvious applications. Eddy's work was driven partly by pure curiosity about Edison's historical experiments. That curiosity led to a discovery that might have practical implications.

Too often, especially in funding-constrained environments, science gets directed toward immediate applications. That's understandable. But some of the most valuable discoveries emerge when researchers have the freedom to ask interesting questions even if the practical payoff isn't obvious upfront.

This research also matters because it shows the continued relevance of foundational thinking. In a field as cutting-edge as graphene research, the solution to a key manufacturing challenge came from revisiting work from 1879. That's humbling. It suggests that no matter how advanced we think we are, older approaches might contain valuable insights if we examine them creatively.

The Future of Material Discovery: Where Does This Lead?

Assuming the Rice University findings hold up under scrutiny from the broader scientific community, where might this lead?

In the immediate term, expect more research exploring flash Joule heating as a graphene production method. Scientists will likely optimize the process, explore variations, and investigate whether similar principles apply to other materials. Some research groups will probably test whether different historical heating technologies (arc lamps, early furnaces, etc.) produced interesting materials.

Medium-term, you might see commercial efforts to develop simplified graphene production systems based on these principles. If the process can be scaled and optimized, it could reduce the cost and complexity of graphene production, which would accelerate deployment of graphene-based applications.

Longer-term, this work might inspire broader efforts to mine historical experimental work for insights. Research institutions might systematically reexamine archived experimental records, old lab notebooks, and historical equipment through modern analytical capabilities. You could imagine discovering unexpected materials, reactions, or phenomena that were created historically but never analyzed properly.

There's also potential for this to influence how we approach contemporary experiments. If scientists know that future researchers might analyze their work through tools and frameworks we can't yet imagine, they might be more careful about preserving samples, documenting procedures, and maintaining detailed records. It would mean thinking of contemporary work not just as solving today's problems, but as creating a record that might reveal insights to future researchers.

Looking Forward: The Next Frontiers

The Edison graphene discovery closes one historical loop while opening others. What historical experiments might contain data about graphene production? What about other materials we now consider revolutionary?

Historians and scientists will likely dig deeper into Edison's lab notebooks to see if there are other clues about what happened in those experiments. Did Edison notice the silvery residue? Did he document color changes or unusual properties of the filaments? Historical context might provide details that Eddy couldn't reproduce.

Other researchers will examine different historical thermal processes. The question "what materials formed under these extreme conditions?" becomes worth asking systematically. Early electric welding, early ceramics manufacturing, early metallurgy—all involved extreme temperatures and reactions that might have created interesting materials.

Scientists might also explore whether modern equipment can detect information in historical artifacts themselves. Are there traces of graphene or other interesting materials in preserved Edison light bulbs? Could we analyze the actual equipment rather than just replicate the experiments?

Beyond graphene specifically, this work opens a philosophical question: how many other important materials or chemical reactions might be hiding in plain sight in historical experiments? What breakthroughs are waiting for someone to ask the right question about the past?

FAQ

What exactly did the Rice University researchers discover?

Lucas Eddy and his team at Rice University recreated Thomas Edison's 1879 light bulb experiments using modern analytical equipment. They found that after heating carbon filaments for 20 seconds at 2,000 to 3,000 degrees Celsius, the materials had partially transformed into graphene. They confirmed this using Raman spectroscopy and transmission electron microscopy, two analytical techniques that didn't exist when Edison conducted his experiments.

Did Thomas Edison intentionally create graphene?

No. Edison couldn't have intentionally created graphene because graphene hadn't been discovered or identified as a material concept in 1879. His goal was to develop a practical light bulb filament. The graphene formation was an accidental byproduct of the thermal conditions his experiments created. Edison lacked the analytical tools to detect graphene even if he had suspected its presence.

How does the flash Joule heating process work in Edison's light bulb?

When electrical current flows through the carbon filament, the resistance generates heat according to Joule's law: Q = I²Rt. At the 110-volt power level Edison used, the carbon filament reaches extreme temperatures (2,000 to 3,000 degrees Celsius) very rapidly. This rapid heating causes some carbon atoms to rearrange into graphene's characteristic hexagonal lattice structure. However, if the heating continues too long or reaches even higher temperatures, the carbon converts to graphite instead of remaining as graphene.

Why is turbostratic graphene different from regular graphene?

Turbostratic graphene consists of stacked layers of single-layer carbon sheets arranged at random angles relative to each other, whereas perfect graphene has perfectly aligned atomic layers. This difference affects electrical conductivity, thermal properties, and mechanical characteristics. Turbostratic graphene is actually easier to produce than perfect graphene and has advantages for certain applications despite the structural imperfections.

Could Edison's light bulbs be used to manufacture graphene commercially?

Potentially, but not in their current form. The yield is low because the entire filament isn't uniformly converted to graphene. Most of the electrical energy produces light rather than driving the carbon transformation. However, researchers are exploring whether modified light bulb designs optimized for graphene production rather than light output could eventually provide an accessible, low-cost method for producing graphene at scale.

What other historical technologies might contain surprising materials or reactions?

Vacuum tubes, arc lamps, early X-ray tubes, and historical electrical apparatus all operated at extreme temperatures or under unusual conditions that might have inadvertently created interesting materials. Researchers are now systematically exploring whether reexamining these historical technologies through modern analytical capabilities could reveal unexpected materials or chemical reactions that weren't recognized at the time.

Why didn't Edison's filaments stay graphene if he created it?

Graphene is thermodynamically unstable in air at room temperature. When exposed to oxygen over extended periods, graphene gradually oxidizes and transforms into other forms of carbon, eventually becoming graphite. If you examined one of Edison's original light bulbs today (over 140 years later), the graphene would have completely converted to graphite and other carbon compounds. The graphene formation is temporary without special protective conditions.

How does this discovery affect current graphene research and production?

It provides both a conceptual direction and practical proof that flash Joule heating through accessible equipment can produce graphene. It might lead to simplified, lower-cost graphene manufacturing methods. More broadly, it demonstrates that revisiting historical experiments and technologies through modern analytical tools can reveal insights that have contemporary relevance. This opens opportunities for systematic examination of other historical work.

What does this say about our understanding of historical scientists and their work?

It suggests that historical scientists accomplished more than they realized and more than we fully understood from analyzing their work with tools available at the time. It doesn't mean we misunderstood what they tried to do, but it does suggest that their experiments sometimes created phenomena or materials that went undetected. This reinforces the value of preserving historical experiments, equipment, and documentation for future analysis.

Could this method work with other carbon-based materials to create different substances?

Possibly. Researchers are exploring whether the same flash Joule heating principle could create other interesting carbon-based materials with different properties. The method might be adaptable to other materials that undergo useful transformations at extreme temperatures. However, each application would require finding the precise temperature and timing window where the desired transformation occurs without progressing to other unwanted forms.

TL; DR

- The Discovery: Rice University researchers recreated Edison's 1879 light bulb experiments and found that the carbon filaments had partially transformed into graphene through rapid heating.

- How It Happened: Using a 20-second heating cycle at 2,000 to 3,000 degrees Celsius, the flash Joule heating process created the precise conditions for graphene formation.

- Edison's Ignorance: Edison couldn't have known about graphene because it wasn't discovered until the 2000s, and he lacked the analytical tools to detect it even if he had suspected it.

- Practical Implications: This discovery suggests graphene production might be possible through simpler, more accessible equipment than conventional manufacturing methods require.

- Broader Significance: It demonstrates how revisiting historical experiments through modern analytical tools can reveal unexpected discoveries and how innovation often comes from bridging different domains and questioning conventional approaches.

Key Takeaways

- Sometimes the most important breakthroughs hide in plain sight, waiting for someone to look at old problems through new lenses

- The catch is you need a heat source that can reach and maintain those temperatures consistently

- You need to understand the constraints and materials that were available at the time

- You need to know whether the person conducting the original experiment documented everything accurately or if they omitted details that seemed obvious to them but are obscure to modern researchers

- Key Lessons from Research Practices

Related Articles

- Best Travel Camera 2025: OM System OM-5 Mark II at Record-Low Price

- Why Curl Killed Its Bug Bounty Program: The AI Slop Crisis [2025]

- Forza Horizon 6: Japan Setting, Career Overhaul & EventLab Changes [2025]

- Ecovacs Deebot X8 Pro Omni Review: Features, Performance & Value [2025]

- AI-Generated Bug Reports Are Breaking Security: Why cURL Killed Its Bounty Program [2025]

- Bitwarden Premium & Family Plans 2025: Vault Health Alerts & Phishing Protection

![Did Edison Really Make Graphene in 1879? Rice Scientists Found Out [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/did-edison-really-make-graphene-in-1879-rice-scientists-foun/image-1-1769281627793.jpg)