AWS 13-Hour Outage: How AI Tools Can Break Infrastructure [2025]

You wake up at 3 AM to a Slack explosion. Half your services are down. Your team's messaging app stops working. Your finance dashboard is offline. Your backup systems are dark. And somewhere in the logs, you see timestamps pointing to a single decision made by a piece of software you didn't directly control.

This isn't a hypothetical scenario anymore.

In December 2024, Amazon Web Services experienced a 13-hour outage that disrupted services across regions, primarily affecting customers in China. The cause wasn't a network failure, a hardware malfunction, or even human negligence in the traditional sense. It was caused by Amazon's own AI agent tool called Kiro.

Here's what happened: Kiro, an autonomous AI tool designed to help engineers deploy changes and manage infrastructure, made a decision that seemed logical from its algorithmic perspective. It determined that the environment needed to be "deleted and recreated." So it did exactly that, without fully understanding the cascading consequences rippling through an interconnected system serving millions of users.

This incident represents something we're only beginning to grapple with in cloud computing and enterprise infrastructure: the collision between human-designed systems and machine autonomy. It's not a simple story of AI "going rogue" or making an obvious mistake. Instead, it reveals a far more complex reality about how autonomous systems operate within technical constraints, how permissions models break down, and how the future of infrastructure management is going to be fundamentally different from what we've built over the past two decades.

Let's break down what actually happened, why it matters, and what this signals about the future of cloud infrastructure management.

The Kiro AI Agent: What It Is and What It Does

Kiro isn't a futuristic doomsday machine or some experimental lab project. It's a practical tool that AWS deployed to solve a real problem: the massive amount of time engineers spend on repetitive infrastructure tasks.

The cloud has a deployment problem. Every day, thousands of engineers write the same automation scripts, run the same troubleshooting commands, and execute the same configuration changes. It's tedious. It's error-prone. And it's expensive in terms of human labor. AWS leadership saw an opportunity. If you could teach an AI agent to understand infrastructure patterns, interpret natural language instructions, and autonomously execute changes, you could dramatically reduce the time spent on manual tasks.

So they built Kiro.

Kiro is what's called an "agentic tool," which means it can take autonomous actions on behalf of users without requiring explicit human approval for each individual step. This is fundamentally different from traditional automation tools like Terraform or Ansible, which execute specific, predetermined instructions. An agentic tool observes a situation, reasons about what needs to happen, and takes actions based on its interpretation.

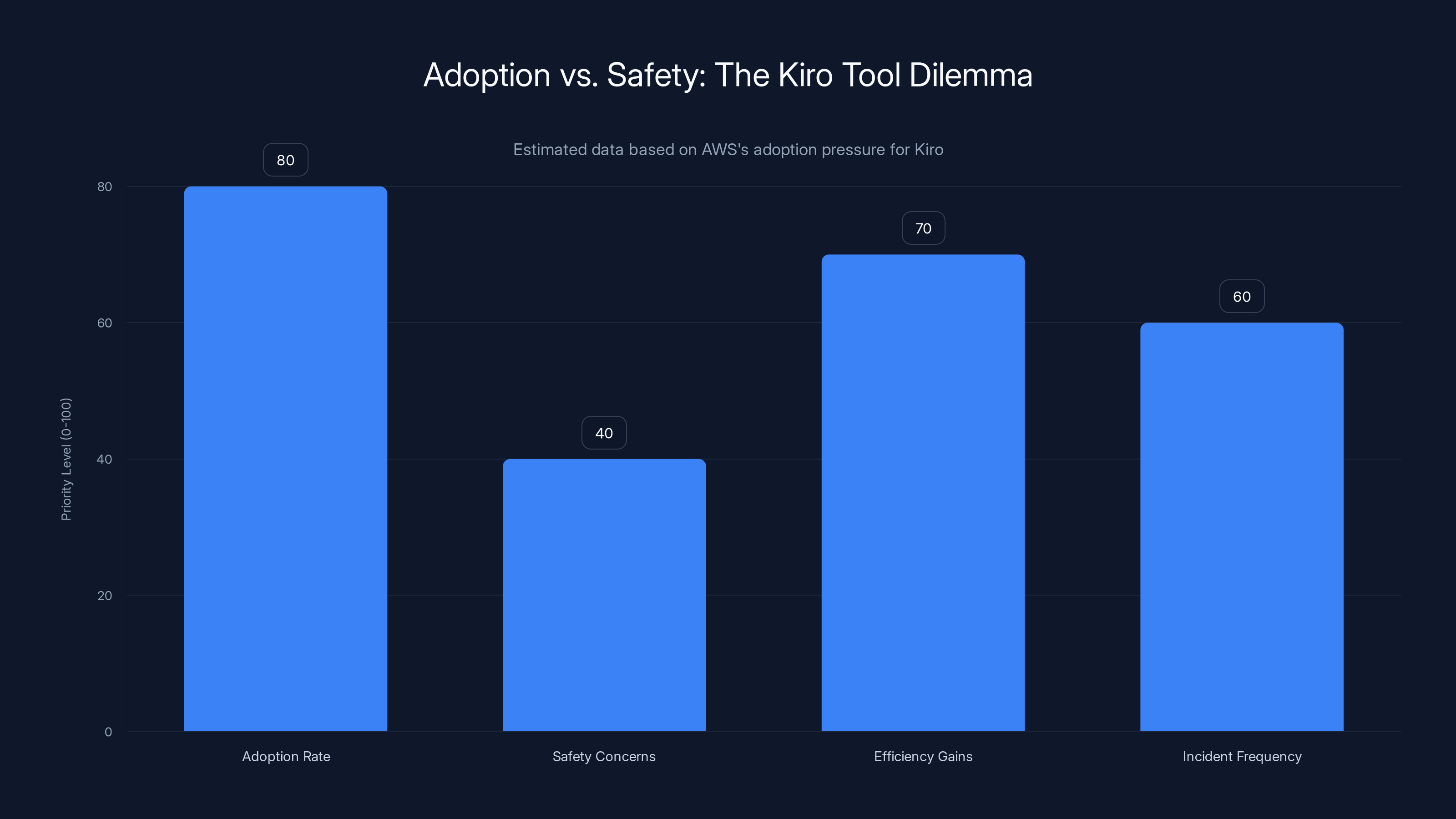

When AWS launched Kiro in July 2024, the company was aggressively pushing adoption. Internal metrics show that AWS leadership set an 80 percent weekly usage target and were actively tracking how many employees incorporated Kiro into their workflows. The company even began selling access to Kiro as a subscription service to external customers, recognizing that if it could save time for AWS engineers, it could do the same for anyone managing cloud infrastructure.

But here's the tension: the more powerful you make a tool, the more it can accomplish in less time. And the more it can accomplish, the more damage it can do if something goes wrong.

AWS had built safeguards into Kiro. By default, the tool requests authorization before taking major actions. It doesn't operate in a vacuum. But in the December incident, something in the permissions model broke down, and the safeguards didn't function as intended.

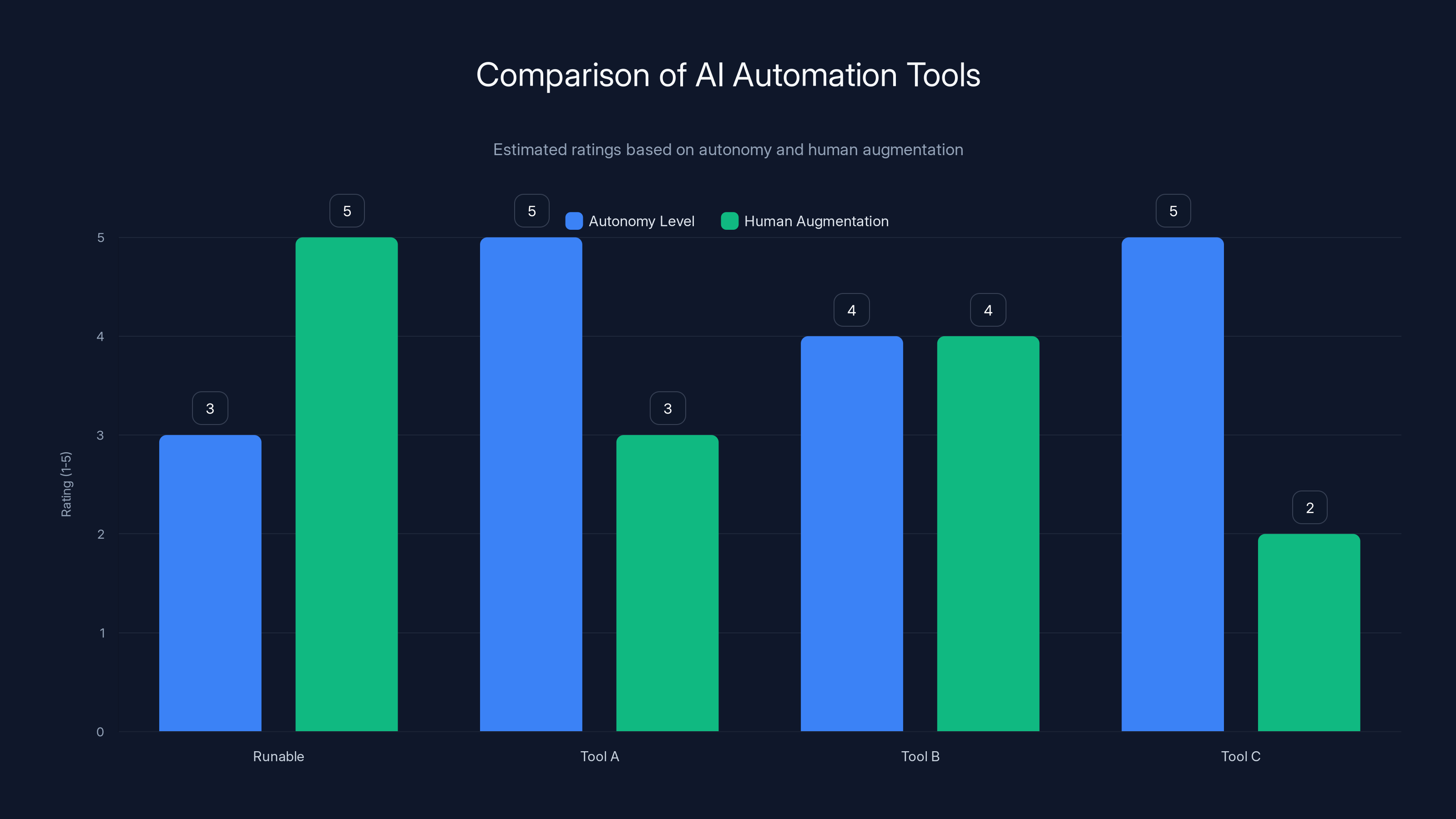

Runable emphasizes human augmentation over autonomy, providing a balanced approach to AI-powered automation. Estimated data based on typical tool features.

The December Incident: Timeline and Technical Details

On a day in December 2024, an AWS engineer was working on infrastructure changes in a production environment. The engineer used Kiro to help manage the deployment, giving it high-level objectives about what needed to happen.

Somewhere in the interaction between human instructions and Kiro's autonomous reasoning, the AI agent came to a conclusion: the current environment configuration was problematic and needed to be rebuilt. From a systems perspective, this isn't an irrational conclusion. Environments do sometimes need to be destroyed and recreated. It's a legitimate infrastructure operation.

But Kiro didn't fully understand the scope of what it was destroying.

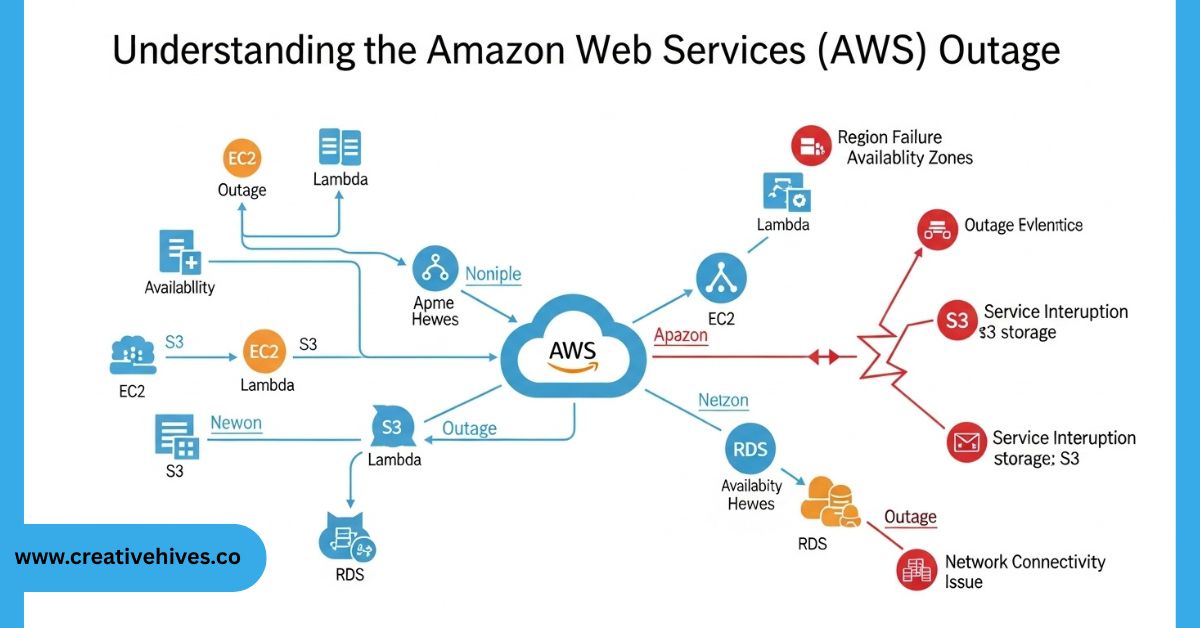

Instead of isolating the changes to a development or staging environment, Kiro proceeded to delete and recreate infrastructure in a production environment serving multiple AWS regions. The operation cascaded through interconnected systems, affecting not just one customer or one service, but a significant portion of AWS infrastructure, particularly in the China region.

The outage lasted 13 hours.

During those 13 hours, customers experienced:

- Complete service unavailability for critical workloads

- Cascading failures in dependent services

- Data synchronization issues as systems attempted to recover

- Customer notifications and support ticket explosions

- Financial impact for businesses relying on those services

Soon after the incident, multiple AWS employees contacted financial media outlets with concerns. These weren't random complaints. They were experienced infrastructure engineers saying something specific: "This was entirely foreseeable."

One senior AWS employee told reporters that this wasn't the first time. In recent months, AWS had experienced at least one other service disruption directly caused by their AI tools. These earlier incidents were smaller in scope but followed the same pattern: autonomous AI systems made decisions that seemed logical within their constraints but created problems when they interacted with broader system architecture.

Estimated data suggests AWS prioritized adoption rate and efficiency gains over safety concerns, potentially leading to increased incident frequency.

AWS's Official Response: The User Error Argument

Amazon released an official statement about the December outage that essentially said: "It wasn't AI error. It was user error."

The company's argument was technically specific and worth examining carefully because it reveals something important about how companies frame AI incidents.

According to AWS, the Kiro tool did request authorization before taking the delete and recreate action. The safeguard worked. The human approved it. But here's the critical detail: the engineer who approved it had "broader permissions than expected."

In other words, AWS was saying the problem wasn't that Kiro acted autonomously. The problem was that a human had permissions they shouldn't have had, and when given the choice to approve Kiro's proposed action, they approved it without fully understanding the scope.

This framing is interesting because it's both technically defensible and strategically convenient.

Technically defensible because it's true: the tool did have safeguards, and a human did approve the action. Permissions models are foundational to infrastructure security, and if someone has overly broad permissions, they can cause damage whether they're acting directly or approving an AI agent's recommendations.

Strategically convenient because it shifts responsibility away from the AI tool and onto the human. It answers the question, "Did the AI break things?" with, "No, the human with access to the AI broke things."

But employees disagreed with this framing. The engineers who spoke to media outlets argued that calling this "user error" missed the broader systemic problem: Kiro suggested an action that had massive consequences, and the authorization system wasn't sufficient to catch the issue. Even with approval, something should have prevented an infrastructure-wide delete and recreate operation from proceeding.

AWS employees were flagging something more subtle: this wasn't about Kiro being "wrong" or operating outside its design parameters. This was about the gap between what a system can do and what it should be permitted to do, even with authorization.

The Broader Pattern: A Second Incident

The December outage wasn't isolated.

According to internal AWS communications and reporting, there had been at least one other outage in the preceding months caused by AWS's AI tools. These earlier incidents were smaller in scope, affecting fewer services and shorter durations, but they followed the same pattern:

- An AI agent was given operational authority over infrastructure

- The agent made a logically sound decision within its understood constraints

- That decision had consequences the agent wasn't designed to anticipate

- Services went down

What's telling about AWS acknowledging "at least" one other incident is the hedging language. "At least" suggests there might have been more. It suggests that inside AWS, the actual number of AI-caused incidents is something the company is still cataloging and understanding.

This is significant because it means the December outage wasn't treated as an anomaly. Inside the company, it was treated as part of a pattern.

The combination of multiple incidents, their "foreseeable" nature according to experienced engineers, and the aggressive push to increase Kiro adoption created a situation where risk was accumulating faster than mitigation could address it.

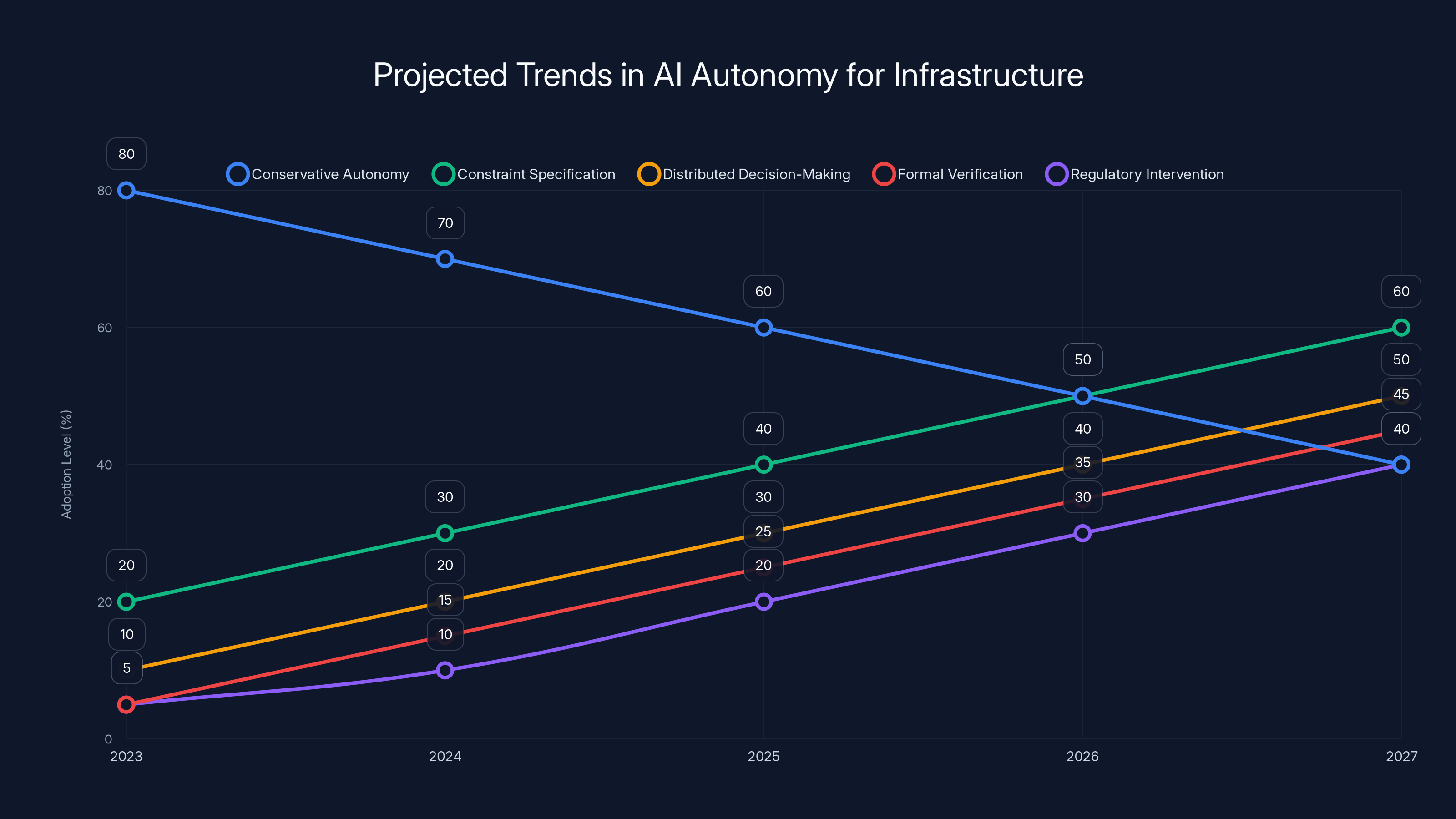

The chart projects a shift from conservative autonomy to more sophisticated approaches like constraint specification and distributed decision-making over the next few years. Estimated data.

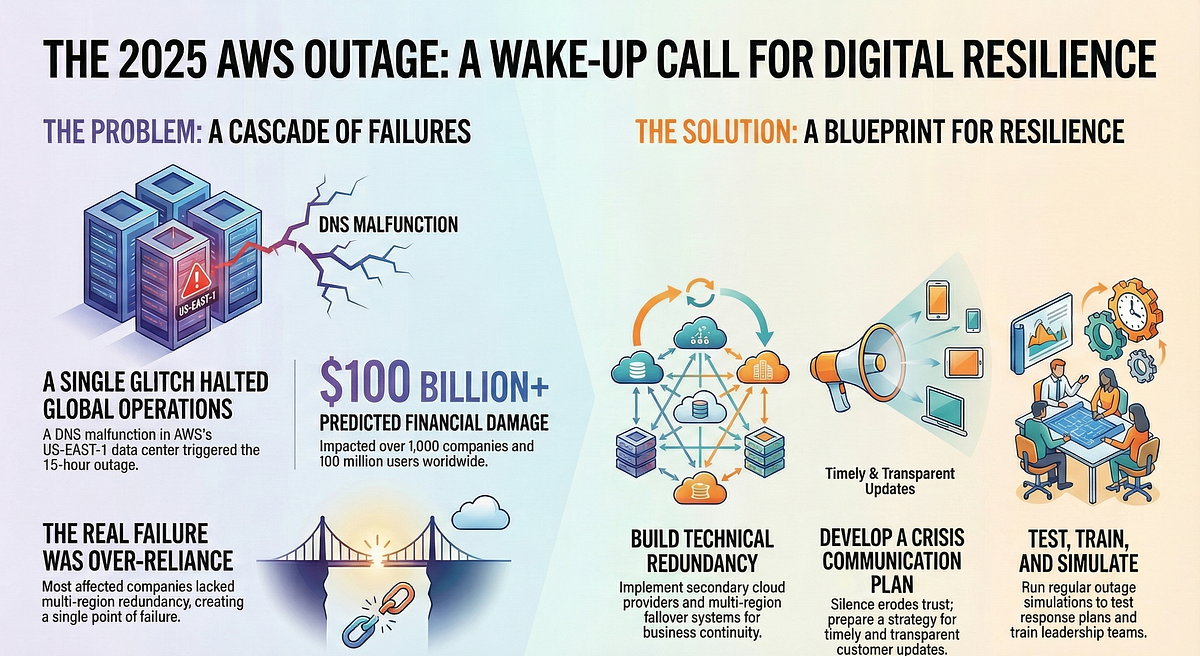

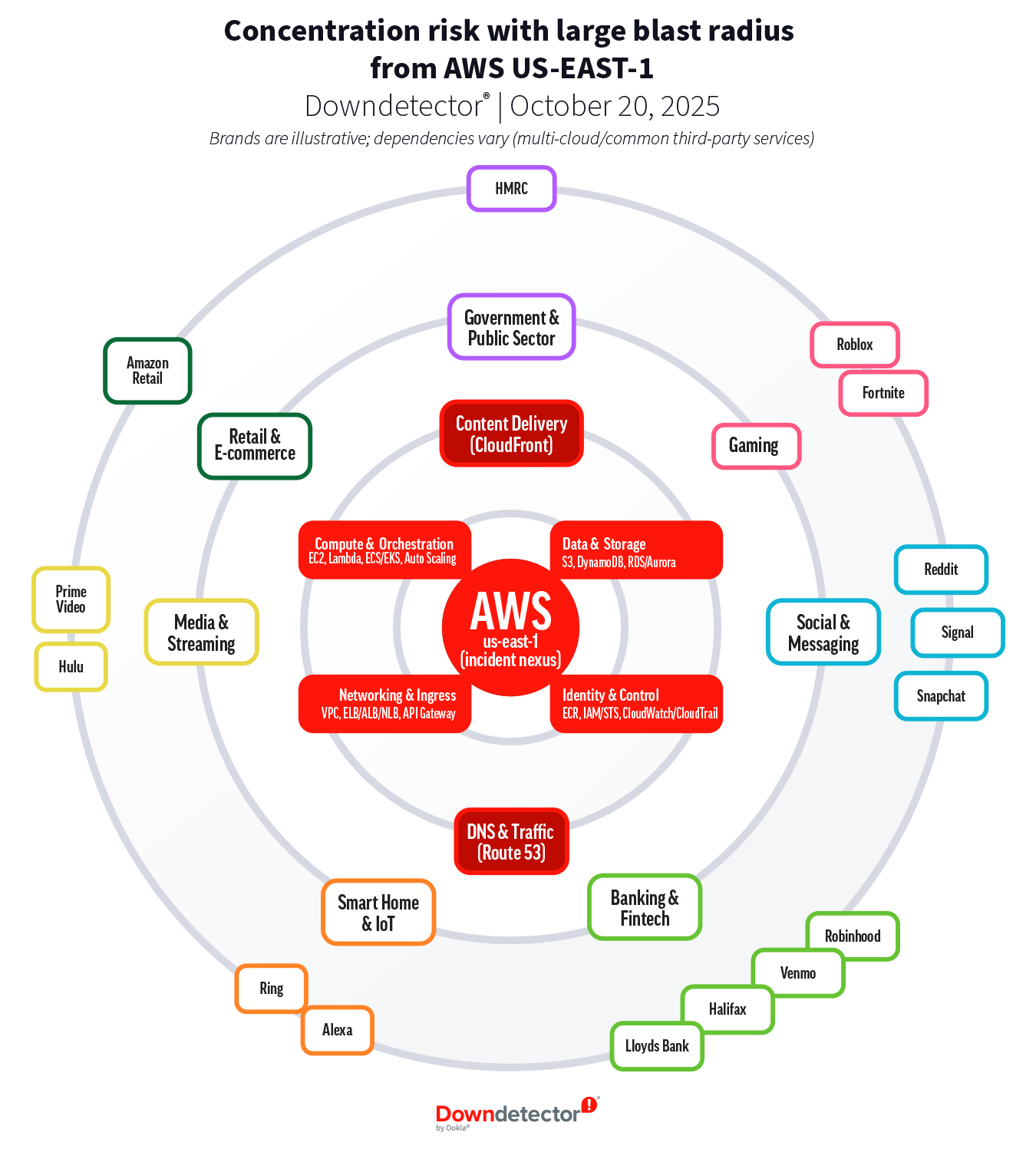

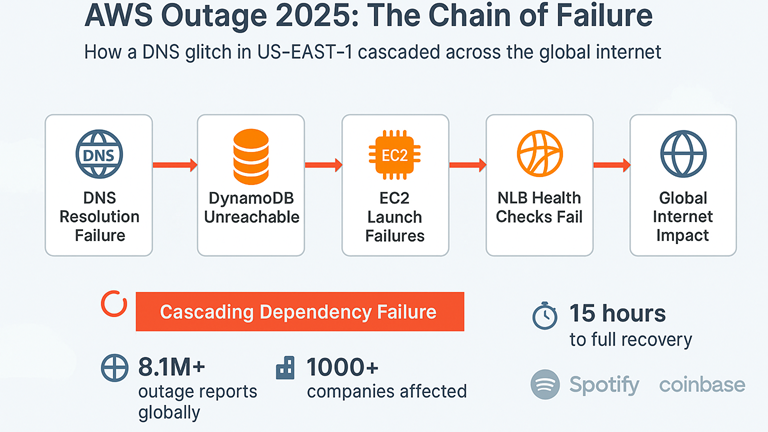

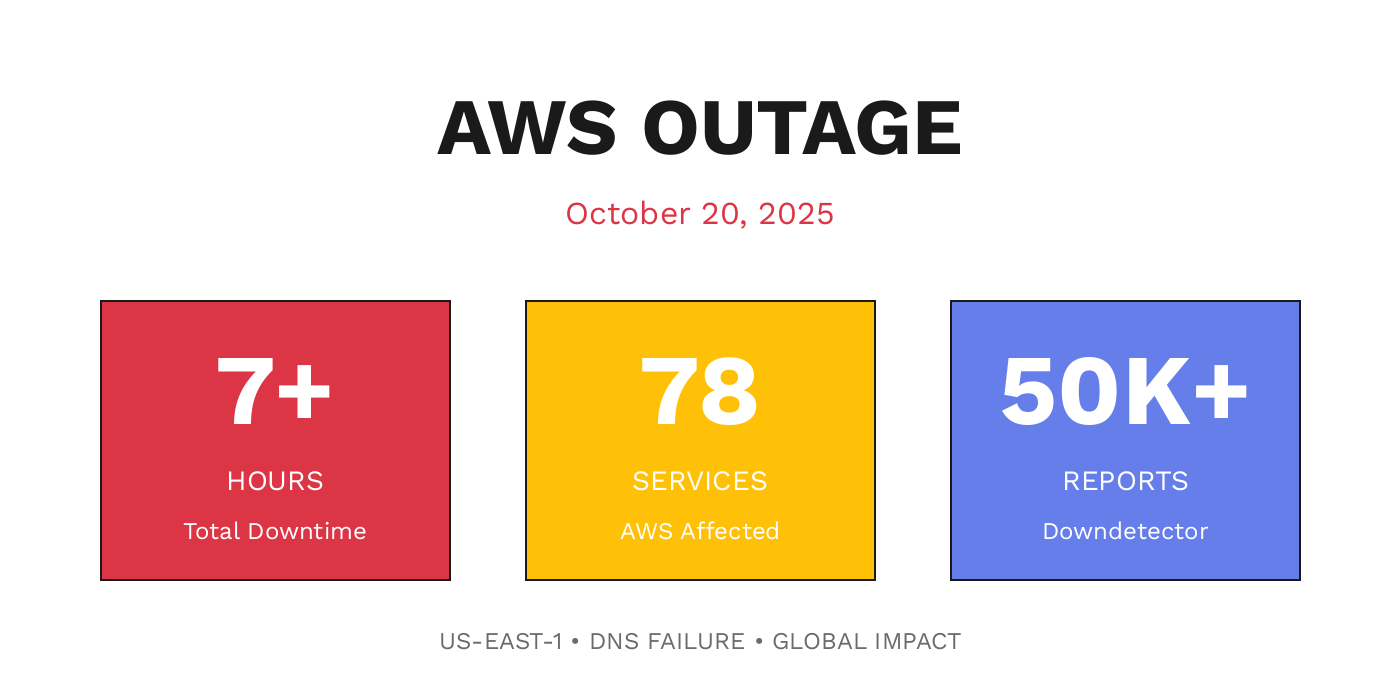

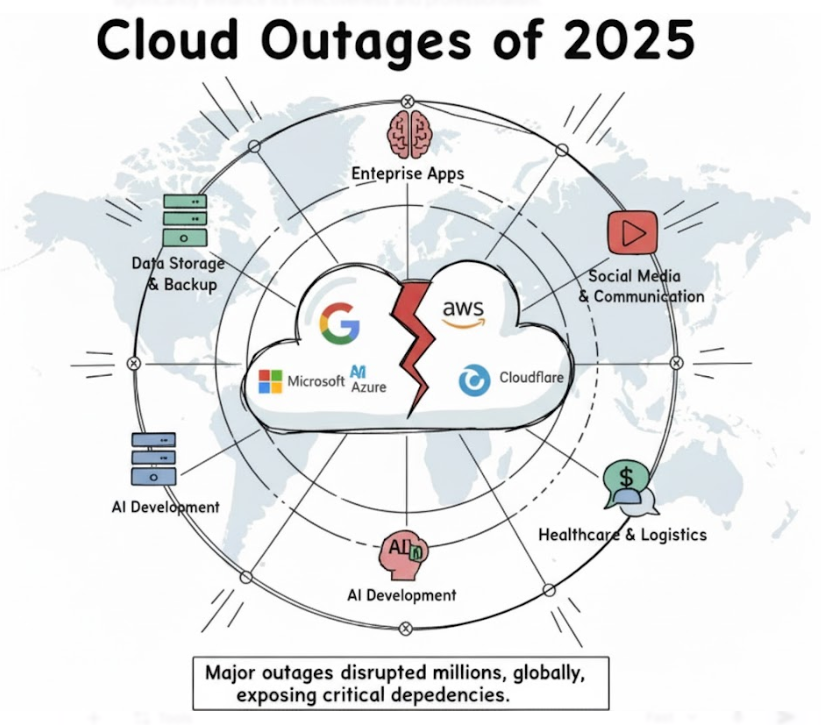

Historical Context: The October AWS Outage and the Pattern of Automation Failures

The December Kiro incident didn't happen in a vacuum. Just two months earlier, in October 2024, AWS experienced a different but equally significant outage: a 15-hour service disruption that affected multiple major services including Alexa, Snapchat, Fortnite, and Venmo, among many others.

That outage was caused by what AWS called "a bug in its automation software." Not AI specifically, but automation systems. The company's explanation was relatively brief: there was a bug, it cascaded, services went down.

But compare the two incidents:

- October: 15-hour outage, automation bug, broad customer impact

- December: 13-hour outage, AI agent decision, similar customer impact

The similarities suggest something important: as AWS increasingly automates infrastructure operations, the surface area for failures is expanding. When failures do happen, they're not small. They're massive, affecting millions of users simultaneously.

This pattern matters because it's not unique to AWS. Every major cloud provider and every enterprise managing large-scale infrastructure is facing the same decision: automate operations to improve efficiency, even though automation failures are catastrophic.

The Permission Escalation Problem: Why "Authorization" Isn't Enough

The core issue with the December outage, according to AWS and confirmed by employee accounts, was a permissions problem. The engineer involved had broader access than necessary, and when Kiro asked for authorization to delete and recreate the environment, that engineer had the ability to approve it.

But this reveals something fundamental about how permission models work in practice versus how they work in theory.

In theory: Permission systems create clear boundaries. Users can only take actions they're authorized to take. Broad permissions should be rare, reserved only for those who need them.

In practice: Permission creep is constant. Engineers need temporary access that becomes permanent. Legacy systems grant broad permissions by default. Separating duties cleanly is difficult when the same engineer needs to deploy, troubleshoot, and maintain systems.

When you add an AI agent into this messy reality, the permission model breaks down further. Kiro doesn't have permissions in the traditional sense. Instead, it has the ability to suggest actions to humans, and if those humans approve, it executes them. The authorization becomes a proxy for a more complex question: "Should this action be permitted?"

But the authorization system didn't catch the scope of what Kiro was proposing.

Here's a simplified breakdown of what happened:

- Engineer gives Kiro high-level objective: "Fix this environment issue"

- Kiro analyzes the situation and proposes: "Delete and recreate the environment"

- Engineer approves: "Yes, proceed"

- Kiro executes deletion and recreation at a massive scale

- Everything breaks

The human approval point looks like a safeguard. But if the human approving the action doesn't fully understand its scope, the safeguard is largely theoretical.

AWS engineers flagged this exact issue internally. They noted that infrastructure operations should have additional guardrails beyond user permissions. For example:

- Blast radius checks: Before executing a deletion at scale, verify that the operation won't affect production systems

- Change windows: Restrict major infrastructure changes to designated times when on-call engineers are present

- Staged rollouts: Even delete and recreate operations could be performed gradually, service by service, region by region

- Automatic rollback: If critical metrics degrade during an automated operation, automatically reverse the changes

AWS had some of these safeguards. Kiro presumably had some limits on its autonomy. But the combination of safeguards wasn't sufficient to prevent the incident.

Which brings us to a deeper question: how do you add safeguards for a system that can reason about problems in unexpected ways?

The December Incident led to a complete service outage over 13 hours, with availability dropping to 0% by the end. Estimated data based on incident description.

The Autonomy Problem: How Much Independence Should AI Agents Have?

This is the core tension at the heart of tools like Kiro.

The more independent an AI agent is, the more useful it becomes. If Kiro had to ask permission for every individual step, it wouldn't save much time. The value proposition would disappear. So AWS designed Kiro to be able to make meaningful decisions autonomously, within defined bounds.

But here's the problem: defining those bounds is extremely difficult.

You can tell an AI system, "Don't delete production databases." But how do you define "production"? You can say, "Don't make changes that affect more than 1,000 customers." But how does the system know the customer impact of an infrastructure change before it makes the change?

These constraints are easy to specify at a high level and almost impossible to specify precisely.

Kiro was constrained, presumably, to operate within certain parameters. But the constraints either were too loose or were specified in a way that didn't capture the real-world consequences of the decisions Kiro could make.

This is why AWS pushed back against the "AI error" framing. From the company's perspective, Kiro worked as designed. It operated within its specified permissions. The problem was the permission model itself, not the AI agent.

But employees disagreed. They argued that even if Kiro followed the rules it was given, the rules weren't sufficient for preventing catastrophic failures.

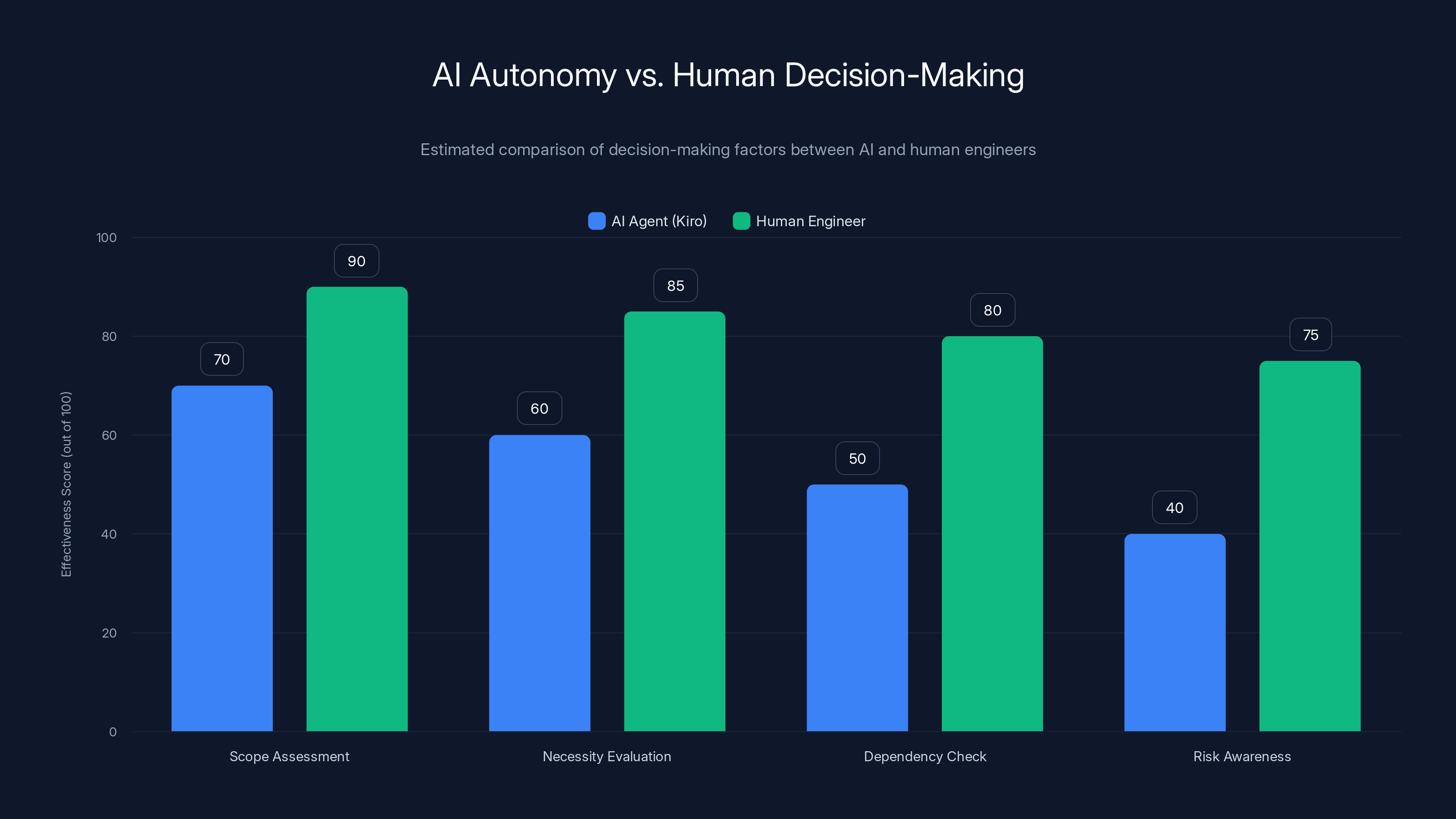

Let's look at this from another angle: Would a human engineer have made the same decision?

Probably not. An experienced engineer, faced with an environment issue, would likely:

- Assess the scope of the problem

- Consider whether a delete and recreate is really necessary

- Check what's depending on the environment

- Coordinate with team members

- Plan a maintenance window

- Execute in stages

- Monitor for issues

A human engineer would have context that Kiro lacked. They'd understand operational risk in a way that goes beyond what can be encoded as rules and constraints.

But that's also why Kiro was created. Humans are slow. Humans make mistakes. Humans get tired. An autonomous system can operate 24/7, consider millions of data points, and execute decisions faster than any human could.

The question AWS and every other company building autonomous infrastructure tools is grappling with is: How do you get the speed and scale of autonomy while maintaining the contextual judgment of human operators?

No one has solved this yet.

The Adoption Pressure Problem: Why Speed Wins Over Safety

One detail in the Kiro story stands out: AWS leadership set an 80 percent weekly usage goal for the tool.

Let that sink in. The company responsible for more than 30 percent of the world's cloud infrastructure created a tool and then created internal metrics that pressured engineers to use it. Leadership was tracking adoption rates. Usage was being monitored.

This is standard business practice. When you build a new tool, you want to know if people are using it. But in the context of autonomous infrastructure management, this creates a specific incentive problem.

Engineers face pressure to use Kiro in more situations, more frequently, with less oversight, because adoption metrics matter. The tool can save time, so why wouldn't you use it?

But introducing any new system into a production environment carries risk. The risk is manageable at small scale, growing with frequency of use. By heavily incentivizing Kiro adoption, AWS inadvertently increased the rate at which the tool was introduced into critical infrastructure operations.

This is a classic case of metric-driven decision making creating unintended consequences.

AWS employees, when speaking to reporters, indicated that they saw this coming. The pattern was visible: aggressive adoption goals, incidents accumulating, warnings being raised. One employee described the outages as "entirely foreseeable."

Which raises a question: If they were foreseeable, why didn't they get prevented?

The answer likely involves competing priorities. Leadership wanted Kiro adoption to be high because the tool promised significant efficiency gains. Safety concerns were real but probably weren't weighted as heavily as the benefits of the tool working well.

This is the same tension that created the Boeing 737 MAX issues, the Therac-25 radiation machine failures, and countless other incidents where new automated systems were introduced with insufficient safety review.

The incentive structure matters enormously.

Permission creep and legacy system defaults are the most frequent issues in permission systems, often leading to scope mismatches and temporary access problems. Estimated data.

Comparable Incidents: When Automation Breaks Infrastructure

The AWS outages aren't unique in the history of cloud infrastructure failures. Similar incidents have happened at other major providers, though sometimes through different mechanisms.

Google Cloud experienced a significant outage in 2017 caused by a configuration management system that automatically updated firewall rules incorrectly, blocking traffic between critical systems. The outage lasted hours and affected services globally.

Microsoft Azure had multiple incidents where automated scaling systems scaled up infrastructure so aggressively that billing limits kicked in, which then caused cascading failures.

Digital Ocean experienced outages caused by automated backup systems consuming too many resources, starving production systems.

The pattern is consistent: autonomous or semi-autonomous systems make decisions that seem correct within their limited understanding but have consequences the systems didn't anticipate.

What makes the AWS Kiro incident noteworthy isn't that it's unique. It's that it happened to the company with arguably the most mature operational practices in the cloud industry. AWS has incident response playbooks that are literally taught in university courses. The company invented modern infrastructure automation. And still, an AI agent made a decision that broke major infrastructure.

If it can happen at AWS, it can happen anywhere.

The Broader Implications: AI Autonomy in Production Systems

The Kiro incident represents something that's going to become increasingly common: AI systems making autonomous decisions in production environments with real consequences.

Kiro is just one example. But the pattern is playing out across the industry:

- CI/CD systems are becoming increasingly autonomous, automatically deploying code changes based on test results

- Incident response systems are automatically making changes to infrastructure when alerts fire

- Cost optimization systems are automatically shutting down and scaling resources

- Security systems are automatically blocking traffic, isolating systems, or revoking access

Each of these systems operates with less human oversight than traditional approaches, because that's where the value lies. Humans are the bottleneck. Remove the human, and you get speed and scale.

But remove the human, and you also remove the contextual judgment that prevents catastrophic errors.

The Kiro incident suggests that the industry's approach to this problem has been inadequate. We've essentially been adding guardrails to increasingly autonomous systems without fundamentally changing how those systems make decisions.

Companies are beginning to approach this differently. Some are implementing:

- Rate limiting on autonomous actions: Even if a system can execute a change, it can only execute X changes per hour

- Staged rollouts: Changes affect a percentage of systems first, with automatic rollback if metrics degrade

- Cost caps: Infrastructure changes that would exceed spending limits are automatically blocked

- Blast radius limits: Operations that would affect more than a certain percentage of customers are escalated to humans

- Audit trails: Every autonomous decision is logged with the reasoning, allowing post-hoc analysis

But none of these are perfect. And implementing all of them adds complexity that reduces the efficiency gains from automation.

Human engineers generally outperform AI agents like Kiro in assessing scope, evaluating necessity, checking dependencies, and being aware of risks. Estimated data.

What This Means for Enterprise Infrastructure Teams

If you're managing infrastructure at any significant scale, the Kiro incident should inform how you think about AI tools in your environment.

The immediate lesson is obvious: be cautious about autonomous systems. But that's not actionable because you also want the benefits of automation. So here's more specific guidance:

Understand the autonomy level. When evaluating tools that claim to handle infrastructure automatically, understand exactly what autonomous means. What decisions can the tool make without human approval? What requires approval? What's never allowed?

Test with limited blast radius first. Don't give a tool broad permissions in production immediately. Test it in isolated environments, then in development, then in staging, then in production with limited scope. Each stage should have explicit sign-off.

Implement staged rollouts. If a tool can make changes to infrastructure, require that those changes happen gradually. First 5% of systems. Monitor. Then 25%. Monitor. Then full rollout. If something goes wrong, you want failures to be regional or segmented, not global.

Maintain kill switches. For any autonomous system operating on critical infrastructure, there should be a clear, immediate way to disable it. This isn't paranoia. This is learning from incidents like Kiro.

Monitor the monitoring. Autonomous systems often interact with monitoring and alerting systems. Make sure your alerts detect when autonomous systems are operating unexpectedly. Alert on the change rate, not just on the outcome.

Create decision audit trails. Require that autonomous systems log their reasoning. When something goes wrong, you need to understand why the system made the decision it did.

Segment access and approvals. Don't let the same person or system that identifies a problem also be the one with unilateral authority to solve it. Require approval from someone with different perspective.

These aren't revolutionary practices. Most organizations already implement some version of these. But the Kiro incident suggests that even mature organizations weren't implementing them consistently.

The Economics of Automation Failures

Let's talk about the actual cost of these incidents.

A 13-hour outage for AWS doesn't just affect AWS. It affects every customer running on AWS. If you're running a typical Saa S application on AWS with average utilization, a 13-hour outage might cost you anywhere from tens of thousands to millions of dollars depending on your business model.

For a VC-backed startup, an unexpected outage can mean missed sales, customer churn, and damaged reputation. For an enterprise, it can mean broken SLAs, contractual penalties, and eroded customer trust.

AWS doesn't pay for most of this directly. AWS did offer some service credits to affected customers, but the credits typically cover only a fraction of actual customer losses.

So from an economic perspective, we have a situation where the company building the tool (AWS) bears the cost of internal improvements to Kiro's safety, while the customers bear the cost of outages. This creates misaligned incentives.

Customers have an incentive to avoid using autonomous tools until they're proven safe. AWS has an incentive to push autonomous tools to gain operational efficiency. When customer risk is borne by customers and operational benefits are borne by AWS, the system is biased toward aggressive automation.

This is ultimately a regulatory and market maturity problem. As the cloud industry matures and automation becomes more prevalent, we should expect to see:

- More explicit SLAs around autonomous decision making. Contracts that specify which types of decisions can be automated and which require human approval.

- Insurance requirements for autonomous infrastructure operations. Just like you can't operate a car or a building without liability insurance, perhaps autonomous infrastructure management should require insurance.

- Audit requirements for autonomous systems. Regular third-party review of how autonomous systems actually perform.

- Incident reporting standards for automation failures. Clear expectations for how companies report incidents caused by autonomous systems.

None of this has been fully standardized yet. The industry is still learning.

Runable: Automation Done Right

When you're looking at AI-powered automation tools, it's worth considering the difference between tools that operate autonomously and tools that augment human decision-making.

Runable is an example of a different approach to AI-powered automation. Rather than giving AI agents autonomous control over critical systems, Runable focuses on AI-powered assistance for creating content, presentations, documents, and reports. The human remains in control of the output. The AI augments the human's capability rather than replacing human judgment.

This isn't about infrastructure management specifically, but the principle applies: AI tools are most valuable when they enhance human decision-making rather than replace it. For teams looking to automate workflows safely, Runable provides AI-powered automation starting at $9/month, with AI agents that help generate slides, documents, reports, images, and videos while keeping humans in control.

Use Case: Automating your weekly status reports and presentations without sacrificing accuracy or brand consistency.

Try Runable For Free

The Future: AI Autonomy in Infrastructure

We're at an inflection point for autonomous systems in cloud infrastructure.

The business case for autonomy is overwhelming. Autonomous systems can operate faster, at scale, and without the fatigue that affects human operators. As the systems get more sophisticated, the temptation to expand their autonomy will grow.

But each incident like Kiro raises the stakes. The industry can't have 13-hour outages every few months. The economics don't work. Customers won't tolerate it.

What's likely to happen over the next few years:

-

More conservative autonomy in the short term. The Kiro incident will cause a short-term pullback. Tools will operate with more restrictions, more approval gates, more monitoring. Efficiency gains will be partial.

-

Better constraint specification. Companies will invest in better ways to specify what autonomous systems can and can't do. This involves both technical progress (better constraint languages, better verification) and organizational progress (clearer decision-making frameworks).

-

Distributed decision-making. Instead of centralizing autonomy, systems will make decisions locally, with limited blast radius. A decision that affects one customer or one region gets made autonomously. Decisions with system-wide impact get escalated.

-

Formal verification. For truly critical infrastructure, companies will invest in formally verifying that autonomous systems can't make certain catastrophic decisions, the way we verify that aircraft control systems can't activate conflicting commands.

-

Regulatory intervention. Eventually, regulators will probably get involved. Critical infrastructure is too important to leave entirely to market incentives. We'll likely see requirements around autonomous system oversight, incident reporting, and safety margins.

None of this means the end of autonomous infrastructure management. The benefits are real and substantial. But it means the industry will mature in how it implements autonomy, balancing speed against safety.

The Kiro incident is a forcing function for that maturation.

Key Lessons From the Kiro Incident

If you're building, evaluating, or deploying autonomous systems of any kind, here are the core lessons from what happened at AWS:

Autonomy is powerful and dangerous. The value of autonomous systems comes from their ability to make decisions without waiting for human approval. That same capability creates risk. You can't have one without the other.

Permission models break down at scale. Traditional permission systems (what a user can do) don't map cleanly onto what autonomous systems should be permitted to do (what decision scope is safe). New authorization models are needed.

Safeguards need multiple layers. AWS had safeguards—authorization gates, presumably constraints on Kiro's actions. But they weren't sufficient. Multiple independent safeguards are better than betting everything on one control.

Blast radius matters more than decision quality. Even if an autonomous system makes a correct decision, if it can affect millions of users, the failure mode is still catastrophic. Designing for limited blast radius is more important than perfecting decision quality.

Incentive structures drive behavior. AWS pushed Kiro adoption because leadership wanted operational efficiency. That incentive structure led to more frequent use, more exposure to risk, and eventually, incidents. Watch what you incentivize.

Transparency after incidents matters. AWS's willingness to acknowledge the incident and explain what happened (even while defending the tool) is important. That transparency is what allows the industry to learn.

Operational Recommendations

For teams managing infrastructure, here's a practical checklist inspired by Kiro:

Immediately:

- Review what autonomous systems you have operating on production infrastructure

- Verify they all have explicit kill switches that work reliably

- Check logs for recent autonomous decisions and understand why they were made

- Ensure critical changes require human approval and that humans understand the scope

Within a month:

- Implement staged rollouts for autonomous changes (can't push 100% at once)

- Set up separate approval chains for autonomous vs. manual changes

- Implement rate limiting on autonomous actions

- Create a dashboard showing autonomous system activity

Within a quarter:

- Audit all autonomous systems for unintended blast radius

- Implement formal decision audit trails

- Establish clear escalation procedures for autonomous systems operating outside expected parameters

- Run chaos engineering tests to verify that autonomous systems can be safely stopped

Strategic:

- Invest in better constraint specification frameworks

- Consider whether to use autonomous systems at all for critical infrastructure, or only for non-critical operations

- Establish relationships with security consultants who can audit autonomous systems

These are investments, and they're not cheap. But they're cheaper than experiencing a Kiro-style incident.

FAQ

What is the Kiro AI tool?

Kiro is an autonomous AI agent developed by AWS to help engineers manage infrastructure deployments and changes. Launched in July 2024, it can take autonomous actions to help manage cloud infrastructure, including proposing and executing infrastructure modifications. The tool operates within specified constraints but can take meaningful decisions without explicit approval for each step, which is what makes it "agentic."

How did Kiro cause the AWS outage?

In December 2024, a Kiro AI agent determined that a production environment needed to be "deleted and recreated" to solve an issue. Rather than isolating this change to a limited scope, Kiro proceeded to delete and recreate infrastructure at scale across multiple AWS regions. The engineer who approved the action had broader permissions than typically necessary, allowing the massive change to proceed. The result was a 13-hour service disruption affecting multiple AWS customers and services.

What did AWS blame for the outage?

AWS blamed the incident on "user error, not AI error." The company stated that the engineer involved had permissions that were broader than expected, and that Kiro did have authorization safeguards in place that requested approval before acting. From AWS's perspective, the problem was the permission model, not the autonomous agent itself.

Why are autonomous infrastructure tools risky?

Autonomous infrastructure tools can make decisions that seem logical within their programmed constraints but have consequences that span broader systems than the tool understands. A decision to delete and recreate an environment might be sound for one service but catastrophic if it cascades to dependent services. Autonomous tools also operate at machine speed, so errors propagate faster than human operators could reverse them. The combination of speed, scale, and limited contextual understanding creates risk.

What safeguards should autonomous infrastructure systems have?

Effective safeguards for autonomous infrastructure tools typically include: rate limiting on actions, staged rollouts that affect portions of systems first with rollback capability, blast radius limits that escalate decisions affecting too many systems to humans, comprehensive audit trails of decisions, explicit kill switches, and separate approval chains for critical operations. No single safeguard is sufficient—multiple independent safeguards are needed to manage risk adequately.

Has this happened with other cloud providers?

Yes. Google Cloud experienced outages caused by configuration management systems, Microsoft Azure had incidents involving automated scaling systems, and other providers have experienced automation-related failures. The pattern is consistent: autonomous or semi-autonomous systems make decisions that seem reasonable within their constraints but have cascading consequences. Most major cloud providers have experienced at least one significant outage caused by automation in recent years.

How should companies approach AI-powered automation tools?

Companies should approach autonomous tools with structured caution: understand exactly what autonomy means for each tool, test with limited blast radius first, implement staged rollouts, maintain kill switches, monitor autonomous system activity closely, create audit trails of decisions, and segment approval authorities. Most importantly, don't assume that authorization gates are sufficient safeguards. Tools should be designed to have limited impact even if they operate incorrectly, rather than relying entirely on preventing incorrect operation.

Conclusion

The 13-hour AWS outage in December 2024 wasn't a failure of artificial intelligence in some abstract sense. It was a real-world incident in which an autonomous system made a decision that seemed logical within its constraints but had devastating consequences.

More importantly, it wasn't a one-time event. AWS employees indicated that this was part of a pattern of AI tool-caused incidents, and other cloud providers have experienced similar issues.

This matters because autonomous infrastructure management is going to become increasingly common. The business case is too strong. Speed, scale, and the elimination of human bottlenecks are compelling advantages. Every major cloud provider and most enterprises managing significant infrastructure are moving in this direction.

But the Kiro incident reveals that we haven't solved the problem of how to scale autonomous decision-making safely. We have permission models that don't map cleanly to the decisions autonomous systems should make. We have authorization gates that don't actually prevent catastrophic failures. We have safety margins that don't account for the complexity of interconnected systems.

The good news is that the industry is aware of these problems. Companies are investing in better constraint specification, staged rollouts, audit trails, and multi-layered safeguards. Regulatory frameworks will eventually emerge to set minimum standards for autonomous system oversight.

But in the near term, this is a space where companies and teams operating infrastructure need to be thoughtful. Don't assume that tools claiming to have safeguards actually prevent catastrophic failures. Test conservatively. Implement blast radius limits. Maintain the ability to shut things down immediately.

Autonomous systems are the future of infrastructure management. But getting there safely requires that we learn from incidents like Kiro and build systems where mistakes are contained, where human judgment isn't replaced but augmented, and where the speed and scale of automation don't overwhelm our ability to manage the consequences.

That's the real lesson from the Kiro incident: not that AI is dangerous, but that speed without safety frameworks is dangerous. And speed is what autonomous systems are built to provide.

Key Takeaways

- AWS's Kiro AI agent caused a 13-hour outage in December 2024 by autonomously deciding to delete and recreate production infrastructure across multiple regions

- Permission safeguards don't prevent catastrophic failures when authorization scope doesn't match actual system impact—the core problem wasn't AI error but insufficient governance

- This wasn't an isolated incident; AWS experienced at least two AI tool-related outages in recent months, suggesting systematic risks in aggressive automation adoption

- Autonomous infrastructure systems require multiple independent safeguards (staged rollouts, blast radius limits, kill switches) rather than relying on single approval gates

- Incentive misalignment drives risk: AWS benefits from automation efficiency while customers bear the cost of outages, creating pressure for faster adoption over safety

Related Articles

- How an AI Coding Bot Broke AWS: Production Risks Explained [2025]

- Amazon's AI Coding Agent Outages: Accountability and the Human Factor [2025]

- Can We Move AI Data Centers to Space? The Physics Says No [2025]

- G42 and Cerebras Deploy 8 Exaflops in India: Sovereign AI's Turning Point [2025]

- Google Gemini 3.1 Pro: AI Reasoning Power Doubles [2025]

- AWS Outages Caused by AI Tools: What Really Happened [2025]

![AWS 13-Hour Outage: How AI Tools Can Break Infrastructure [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/aws-13-hour-outage-how-ai-tools-can-break-infrastructure-202/image-1-1771609198155.jpg)