Introduction: When the Unlock Button Becomes a Weapon

Imagine this: you're detained by police, your phone is taken away, and within hours—sometimes minutes—authorities have accessed your private messages, photos, location history, and financial records. No warrant. No legal process. Just a tool called UFED, and someone with the right credentials.

This isn't science fiction. It's the current reality in multiple countries where Cellebrite's phone unlocking technology operates. And here's where it gets complicated.

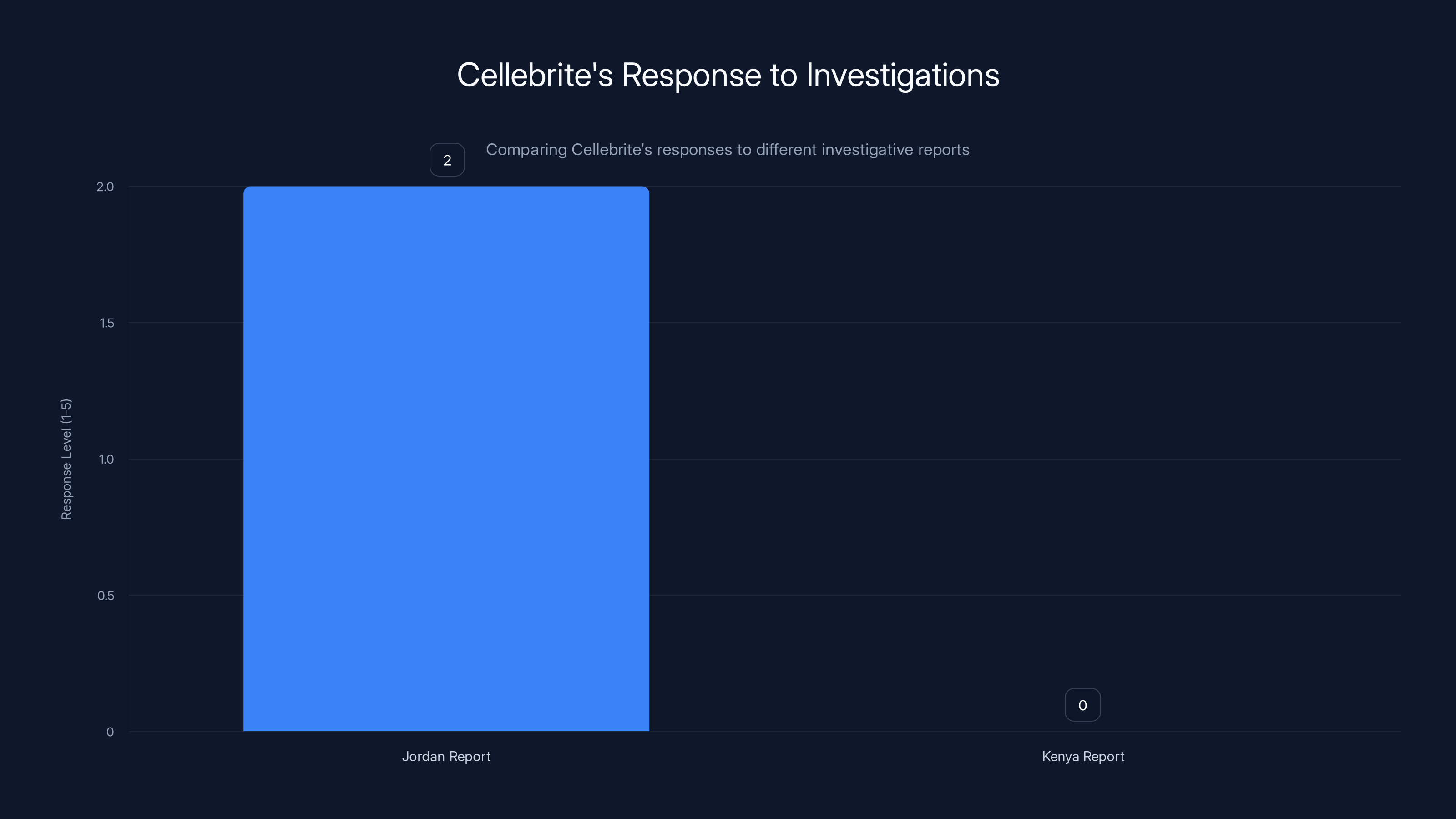

Last year, Cellebrite announced it had suspended Serbian police as customers following allegations that local authorities used its tools to hack into the phones of journalists and activists. The company cited human rights research as justification. But when nearly identical accusations surfaced in Jordan and Kenya just months later, Cellebrite's response shifted dramatically. Instead of investigating or taking action, the company dismissed the allegations as "speculation" and declined to commit to any formal inquiry.

This inconsistency raises a critical question: what determines when a surveillance tool company actually holds its customers accountable? And more importantly, who pays the price when they don't?

The answer involves digital forensics, international politics, human rights advocacy, and a multi-billion dollar market in phone hacking technology that operates in a legal gray zone. Understanding this story matters because it affects journalists, activists, whistleblowers, and ordinary people in dozens of countries worldwide.

Over the next few minutes, we'll explore how Cellebrite built a business around unlocking phones, why governments around the world desperately want this technology, what happens when authorities abuse it, and why the company's selective enforcement of its own ethical guidelines might be the most dangerous vulnerability of all.

TL; DR

- Cellebrite suspends Serbia: The Israeli phone-hacking tool maker cut off Serbian police after documented abuse of its UFED technology against journalists and activists, marking a rare public accountability measure.

- Jordan and Kenya allegations ignored: When nearly identical accusations emerged in Jordan and Kenya, Cellebrite dismissed evidence and declined to investigate, signaling a shift in corporate policy.

- Digital forensics prove abuse: Researchers at the University of Toronto's Citizen Lab identified Cellebrite application traces on victims' phones using technical analysis and digital certificates.

- 7,000+ law enforcement customers: Cellebrite claims an enormous global customer base, yet selective enforcement raises questions about vetting standards and corporate accountability.

- Pattern of inconsistency: The company previously cut off Bangladesh, Myanmar, Russia, and Belarus, but refuses to apply similar standards to newer allegations despite comparable evidence.

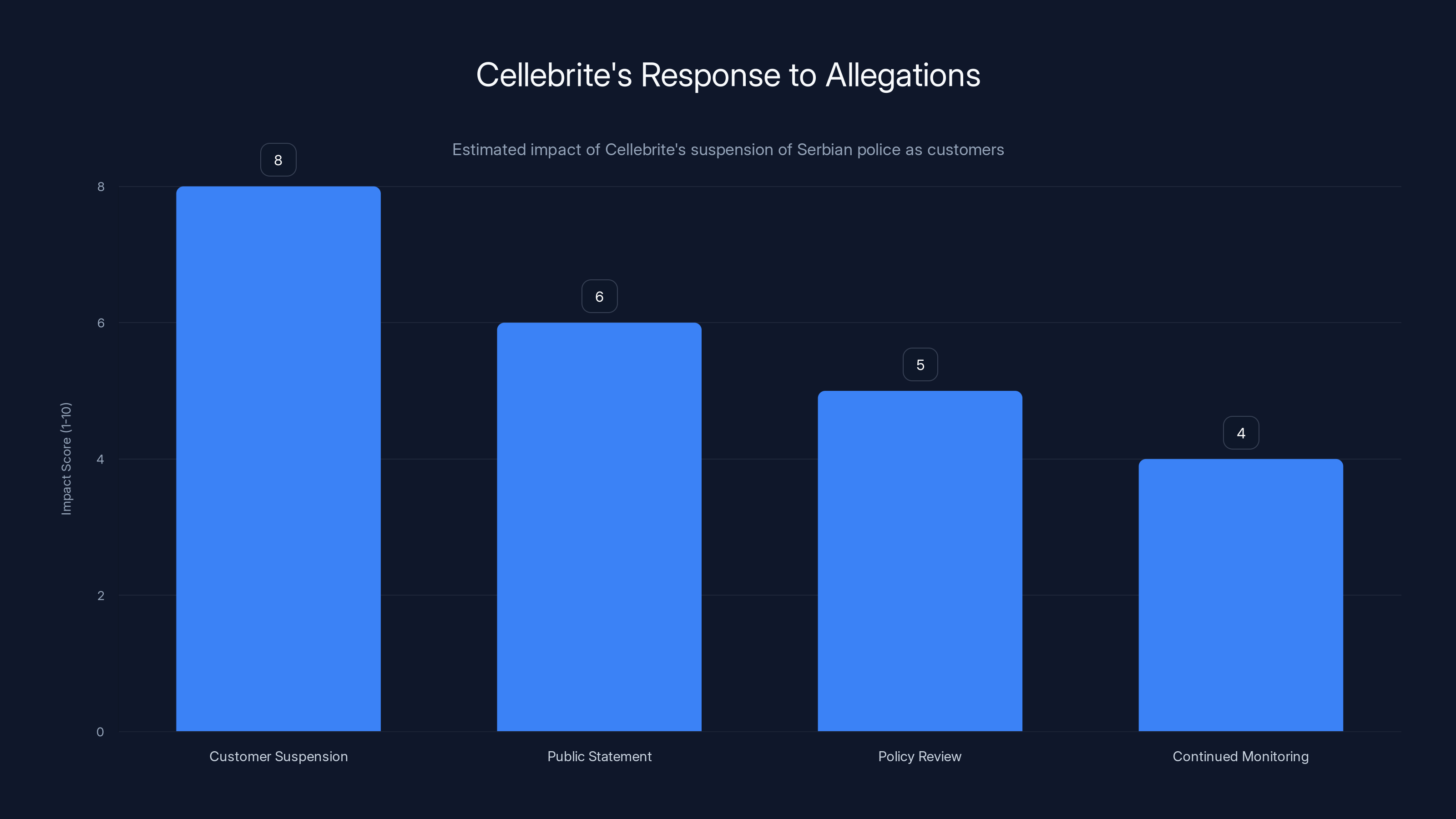

Cellebrite's suspension of Serbian police had the highest impact in addressing the allegations, showing a strong stance against misuse of their technology. (Estimated data)

The Cellebrite Business Model: Unlocking Phones, Enabling Abuses

What Cellebrite Actually Does

Cellebrite isn't a household name, but its tools are ubiquitous in law enforcement agencies worldwide. The company's flagship product, UFED (Universal Forensic Extraction Device), is essentially a specialized computer that can extract data from mobile phones even when they're locked, encrypted, or damaged.

The technology works through multiple methods. Some phones can be cracked through brute-force attacks on weak PIN codes. Others require exploiting specific vulnerabilities in operating systems. For newer, more secure devices, Cellebrite sells separate tools like Cellebrite Pathways that analyze data already extracted, helping investigators sift through millions of files.

On paper, this serves legitimate law enforcement purposes. Police investigating serious crimes need access to evidence stored on suspects' phones. A murder investigation might require text messages, location data, or photos that prove guilt or innocence. Child exploitation cases sometimes depend on extracting data from devices used to distribute illegal material.

But here's the crucial problem: the same tools that unlock a criminal's phone can unlock an activist's, a journalist's, or a political dissident's phone with identical efficiency. The technology has no built-in moral compass. It doesn't distinguish between legitimate law enforcement and authoritarian surveillance.

The Market That Drives Everything

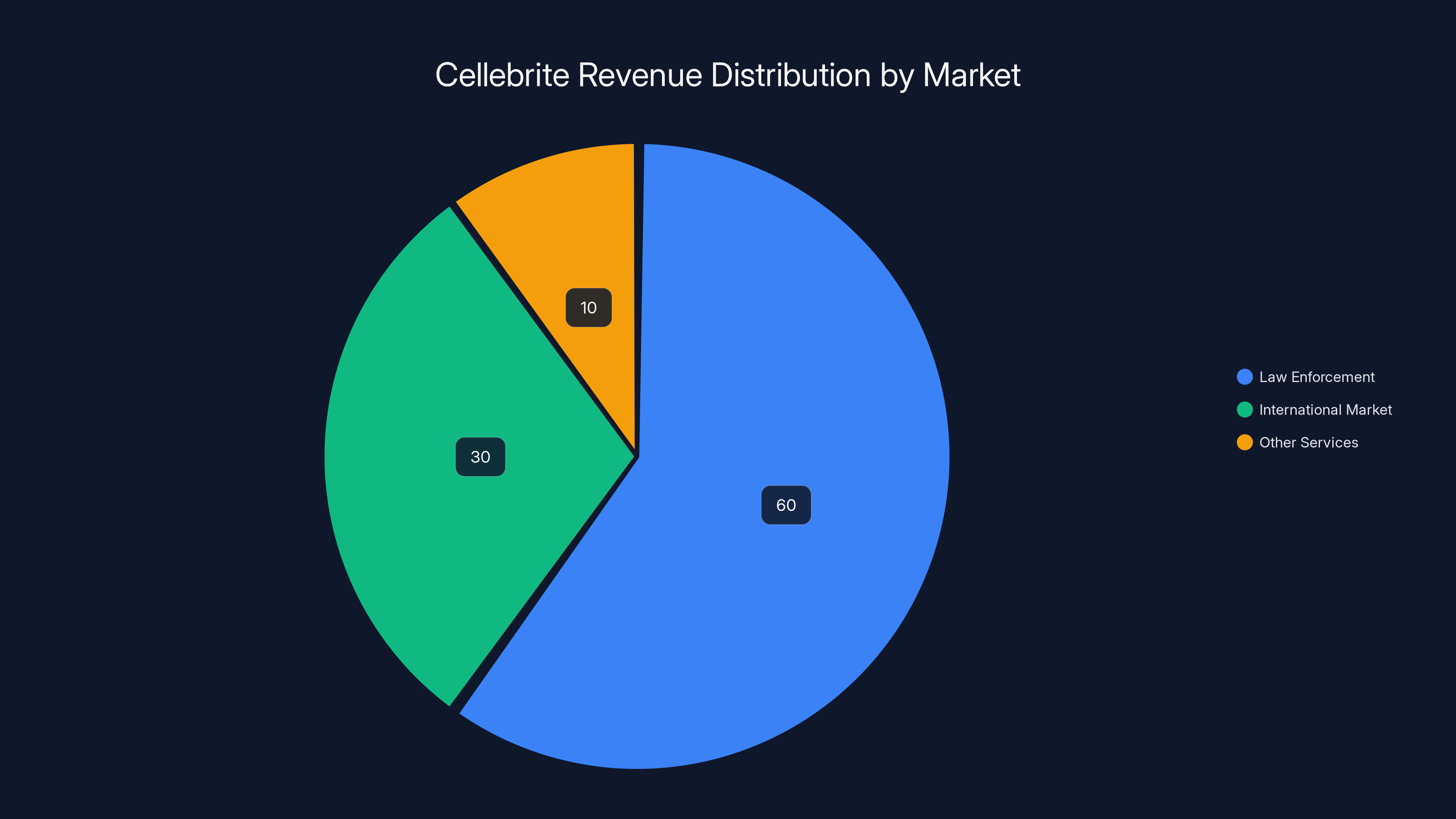

Cellebrite generated approximately $360 million in revenue in 2024, with operating margins that make venture capitalists salivate. The company went public via SPAC merger in 2021, and investor presentations emphasize the "recurring revenue" from law enforcement contracts and the "growing international market" for mobile forensics tools.

The international market part deserves emphasis. Many developing nations lack sophisticated cybercrime units or advanced digital forensics capabilities. For them, Cellebrite offers a shortcut. Instead of building expensive domestic expertise over years, they can simply purchase the tools and training.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. Cellebrite profits from volume sales, not from auditing how customers actually use the tools. Adding oversight mechanisms, investigations, or accountability processes costs money and complicates sales cycles. From a pure business perspective, it's cheaper to sell the tools and pretend abuse allegations are someone else's problem.

How the Technology Spreads

Cellebrite doesn't sell directly to corrupt officials or human rights abusers. Instead, they sell to government agencies, which supposedly include vetting processes and legal oversight. National police agencies purchase UFED units. Detective training academies get Cellebrite certification courses. Law enforcement organizations sign multi-year support contracts.

But once the technology exists within a government, controlling its use becomes virtually impossible. A tool purchased by a legitimate police homicide unit can easily be redirected toward political surveillance by an intelligence agency operating in the same building. Internal accountability mechanisms rarely exist in developing democracies or authoritarian states.

The software itself includes no watermarking or tracking that would identify when and where devices were accessed. There are no automatic logs sent to Cellebrite servers. Unlike some surveillance technologies that include built-in kill switches or reporting requirements, UFED operates as a standalone forensic tool that leaves no traces pointing back to the vendor.

Cellebrite's revenue is primarily driven by law enforcement contracts, comprising an estimated 60% of total revenue, with a significant portion from international markets. (Estimated data)

The Serbia Case: When Cellebrite Actually Took Action

The Allegations Against Serbian Authorities

In 2024, researchers at Amnesty International conducted a technical investigation into phone hacking allegations in Serbia. They examined the devices of a prominent journalist and a known activist after both reported that their phones had been compromised.

Using forensic tools and technical analysis, Amnesty International's researchers found evidence pointing specifically to Cellebrite's UFED technology. They identified digital artifacts—specialized files and application signatures—that are characteristic of Cellebrite's phone extraction process. The researchers traced these signatures back to known Cellebrite tools and published their findings in a detailed technical report.

The allegations painted a concerning picture. Serbian police and intelligence agencies had allegedly used Cellebrite's tools to unlock phones without warrants, proper legal authorization, or formal investigation frameworks. This wasn't sophisticated counterterrorism or organized crime investigation. It appeared to be surveillance targeting journalists and civil society activists.

The legal landscape in Serbia matters here. The country operates under a democratic constitution with nominal protections for privacy and press freedom. Yet throughout the 2010s and 2020s, journalists reported increasing surveillance, arbitrary detention, and harassment. Having technical evidence that government agencies used phone unlocking tools against political figures added concrete data to longstanding complaints about surveillance overreach.

Cellebrite's Response: Swift Action

What makes the Serbia case noteworthy is how decisively Cellebrite responded. After Amnesty International published its report, the company announced it was immediately suspending Serbian police as customers. This wasn't a vague "we're concerned" or "we'll monitor the situation" response. It was a direct business action with real consequences.

Cellebrite's official statement acknowledged the Amnesty International findings and committed to preventing further abuse. The company said it would implement additional verification procedures and review its customer relationships in the region.

For a surveillance technology vendor, this was genuinely unusual. Companies in this space rarely cut off customers, even when facing credible abuse allegations. Doing so risks other customers questioning the vendor's stability and reliability. It creates precedent for future accountability. It admits liability in ways that can trigger lawsuits and regulatory scrutiny.

But Cellebrite did it anyway in Serbia's case. Why?

The Leverage Point: International Reputation

One possibility involves reputational calculus. Serbia, despite its democratic aspirations, isn't a major Western market for Cellebrite. The company's primary customers exist in the United States, Western Europe, and other developed democracies where law enforcement operates under stronger constraints.

Suspending Serbian customers generates positive headlines in Western media. Human rights organizations praise the move. U.S. and European lawmakers notice that the company takes abuse seriously. Meanwhile, losing Serbian revenue has minimal financial impact on a company generating $360 million annually.

In contrast, continuing to sell to Serbia after Amnesty published evidence of abuse would trigger intense criticism from digital rights advocates, potentially affecting Cellebrite's reputation in its most profitable markets.

From this perspective, cutting off Serbia was a rational business decision, not primarily a moral one. The reputational cost of continuing the relationship exceeded the financial benefit of the Serbian market.

The Jordan Investigation: When Evidence Becomes "Speculation"

What Citizen Lab Found

In January 2025, researchers at the University of Toronto's Citizen Lab published a report alleging that Jordanian authorities had used Cellebrite's UFED technology to hack into the phones of local activists and protesters.

The Citizen Lab is crucial to understand. It's not an activist organization or fringe group. It's a university-based research institution with a two-decade track record investigating digital surveillance. The lab's researchers have been cited by the United Nations, recognized by major human rights organizations, and published in peer-reviewed academic venues.

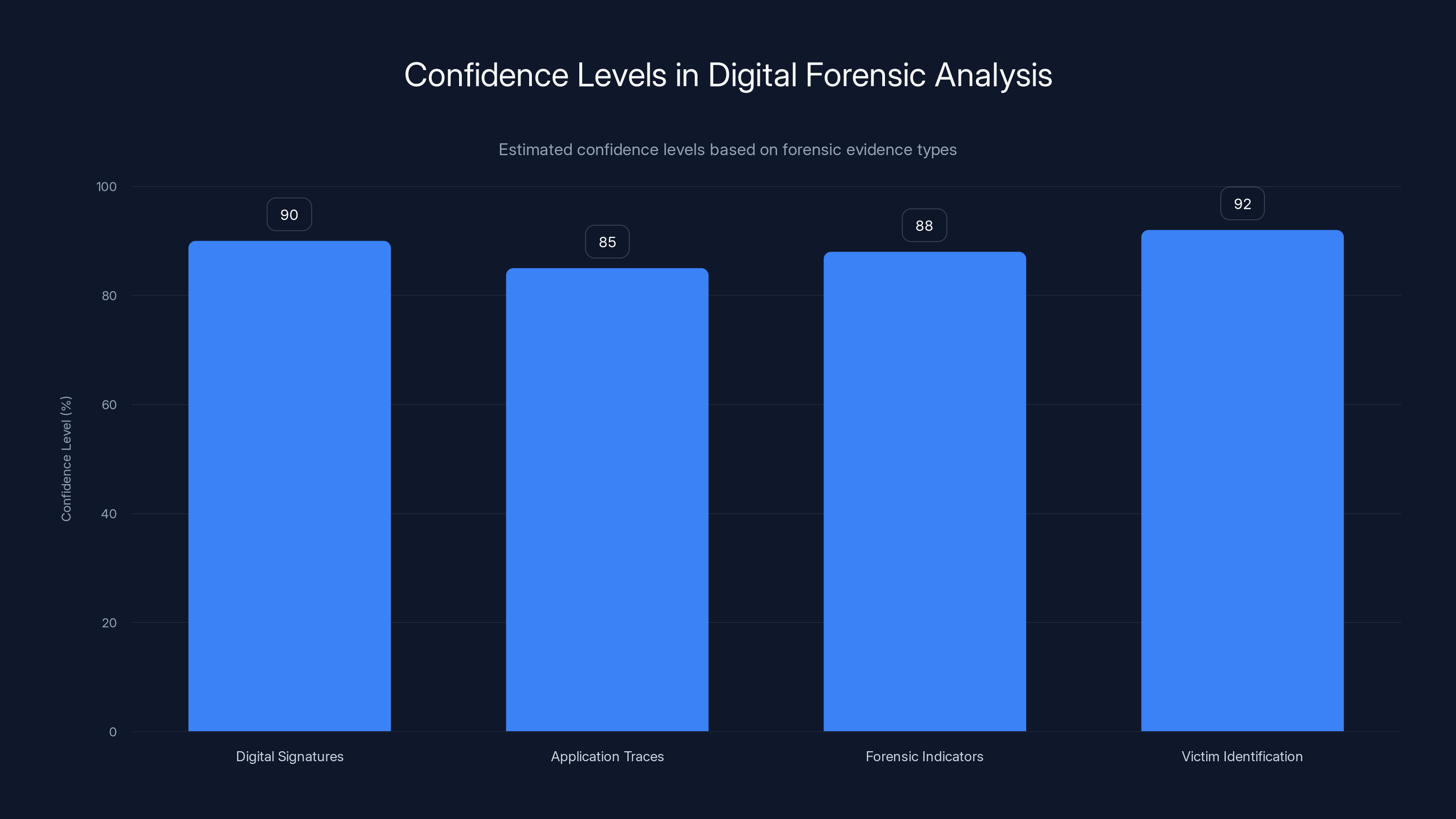

For the Jordan investigation, Citizen Lab researchers conducted forensic analysis on victims' devices and found the same digital signatures identified in the Serbia case. These signatures are highly specific to Cellebrite's technology. The researchers also noted that the same application traces had been previously found on Virus Total, a malware analysis service, and were digitally signed with certificates owned by Cellebrite.

In forensic analysis, this level of evidence is considered strong. When digital artifacts match previous known samples, when digital signatures point to a specific vendor, and when the pattern matches established methodologies, it constitutes what researchers term "high confidence" identification.

The victims in the Jordan case weren't anonymous. Citizen Lab named specific individuals, described their activities, and documented the timeline of when their phones were compromised. The researchers explained exactly which forensic indicators led them to conclude that Cellebrite tools were used.

Cellebrite's Non-Response

Here's where the story diverges from Serbia. When Citizen Lab researchers reached out to Cellebrite before publication to provide the company with a right to respond, Cellebrite's answer was essentially: "This is speculation, and we don't investigate speculation."

Official statement from Cellebrite spokesperson Victor Cooper: "We do not respond to speculation and encourage any organization with specific, evidence-based concerns to share them with us directly so we can act on them."

This phrasing is fascinating because Citizen Lab had already provided specific, evidence-based concerns. The researchers sent detailed technical documentation. They identified victims by name. They explained the forensic methodology. They provided digital signatures and certificates. By any standard definition, this qualifies as specific, evidence-based information.

Yet Cellebrite characterized it as speculation. When asked why the company was treating the Jordan allegations differently from Serbia, Cooper said the "two situations are incomparable" and that "high confidence is not direct evidence."

Note the goalpost shift. In Serbia, Amnesty International's findings were credible enough to warrant immediate customer suspension. In Jordan, nearly identical evidence from a more prestigious research organization was dismissed as insufficient.

The Accountability Vacuum

When Citizen Lab researchers followed up asking whether Cellebrite would investigate the allegations, the company declined to respond to multiple follow-up emails. This silence is itself significant.

In the Serbia case, Cellebrite moved quickly, communicated clearly, and took decisive action. In the Jordan case, the company ignored requests for clarification and refused to commit to any investigation or verification process.

This suggests that Cellebrite's decision-making framework isn't based primarily on evidence quality. If it were, similar evidence would trigger similar responses. Instead, decisions appear to depend on other factors: market considerations, reputational risks in specific jurisdictions, or political calculations about which allegations will generate international pressure.

Cellebrite suspended its services in Serbia due to human rights abuse allegations but did not take similar actions in Jordan or Kenya despite similar allegations. This suggests that factors beyond ethical standards, such as market size or geopolitical considerations, may influence their decisions.

The Kenya Report: The Pattern Becomes Undeniable

Boniface Mwangi and the Activist's Dilemma

In February 2025, just weeks after the Jordan report, Citizen Lab published another investigation alleging that Kenyan authorities had used Cellebrite tools against Boniface Mwangi, a prominent Kenyan activist and politician.

Mwangi's case carries particular significance because his profile is well-documented. He's known internationally, has media coverage, and has previously been detained by Kenyan authorities. When his phone was compromised, the incident could be cross-referenced with known periods of detention and harassment.

Forensic analysis by Citizen Lab identified the same Cellebrite application traces found in previous cases. The researchers noted that Mwangi's phone was accessed while he was in police custody, making it highly likely that law enforcement directly used the tools rather than some other party.

The technical evidence was comparable to the Jordan case. Citizen Lab provided detailed findings to Cellebrite in advance of publication. The researchers explained their methodology, showed their forensic indicators, and gave the company ample opportunity to investigate or respond.

Cellebrite's Strategic Silence

Unlike the Jordan case, where Cellebrite dismissed findings as speculation, the company's response to the Kenya report was simply silence. Cellebrite acknowledged receipt of Citizen Lab's inquiry but provided no substantive comment.

This silence creates a different kind of accountability gap. It's not just that the company rejected the findings. It's that they refused to engage at all. When researchers asked follow-up questions about Cellebrite's vetting procedures for Kenyan authorities, approval criteria, or how many licenses had been revoked, there was no response.

John Scott-Railton, one of the Citizen Lab researchers, stated publicly: "We urge Cellebrite to release the specific criteria they used to approve sales to Kenyan authorities, and disclose how many licenses have been revoked in the past. If Cellebrite is serious about their rigorous vetting, they should have no problem making it public."

The implicit accusation here is direct: if Cellebrite's vetting process were truly rigorous, the company would have nothing to hide. The refusal to disclose criteria or license revocation data suggests either that the vetting process is inadequate or that Cellebrite knows current practices wouldn't withstand public scrutiny.

Why Kenya Might Be Different

Kenya presents a different market calculation than Serbia. Kenya's government is a major U.S. ally in East Africa, with significant military and intelligence partnerships with Western powers. The country also represents a larger regional market for law enforcement technology. Alienating Kenyan authorities could have cascading effects on Cellebrite's ability to sell to other African nations.

Additionally, Kenya's government has more institutional stability than Serbia's. While both countries have documented human rights concerns, Kenya's security agencies are larger, more established, and more integrated into international law enforcement networks. Cutting off Kenyan customers might trigger diplomatic consequences that a decision to suspend Serbian sales wouldn't.

From a pure business standpoint, the Kenya market might be considered too valuable and too strategically important to sacrifice, regardless of the evidence of abuse.

The Methodology: How Researchers Prove Cellebrite Was Used

Digital Signatures and Forensic Artifacts

When Cellebrite's UFED tool extracts data from a phone, it doesn't leave no trace. Instead, it leaves very specific traces that forensic analysts can identify.

First, there are the digital signatures and cryptographic certificates. Cellebrite signs its software with specific digital keys that only the company controls. When researchers examine an extracted device, they can find files signed with these exact certificates. It's not possible for another organization to legitimately create files with Cellebrite's certificates without stealing the company's private keys.

Second, there are application artifacts. UFED creates specific file structures, databases, and metadata patterns that are characteristic of the tool's operation. When data is extracted, it's organized in recognizable formats. When analyzed, these formats match previous known samples of Cellebrite-extracted data.

Third, there's Virus Total correlation. Virus Total is a malware analysis service that aggregates samples from security researchers worldwide. When Cellebrite tools are submitted for analysis—which happens when security researchers or antivirus companies upload samples—they're cataloged in Virus Total with their signatures. Researchers can then search Virus Total for those signatures and find all known instances of similar tools.

When researchers find application traces on a victim's phone that match Cellebrite signatures found in Virus Total, that's strong corroborating evidence.

Why This Method Is Reliable

Cellebrite argues that high confidence identification based on these artifacts isn't sufficient proof. But forensic evidence rarely works like courtroom drama. In a criminal trial, you typically can't have video of the crime directly attributing the tool to the perpetrator. Instead, you have circumstantial evidence that, when combined, points to guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

The same logic applies here. Digital signatures, application artifacts, and Virus Total correlations, when combined, create a very narrow set of possible explanations. Either Cellebrite's tools were used, or someone successfully stole Cellebrite's cryptographic keys and replicated their technology perfectly, which is exponentially less likely.

Forensic analysts and digital security researchers worldwide consider this methodology reliable. Published academic papers in cybersecurity venues accept this type of evidence. International investigations by organizations like Amnesty International base conclusions on similar forensic analysis.

When Cellebrite claims this isn't "direct evidence," the company is essentially raising the evidentiary bar to an unrealistic level. Direct evidence of phone hacking would require access to logs that Cellebrite's own tools don't create, or testimony from the authorities doing the hacking, neither of which will be forthcoming.

The Practical Reality of Investigation

Human rights researchers can't simply demand that Kenyan or Jordanian authorities admit they used Cellebrite tools. These same authorities are accused of detention and abuse. They have every incentive to deny wrongdoing and claim they obtained phone data through legitimate means.

Cellebrite, in contrast, could actually investigate. The company has access to customer logs, license activation records, and technical support requests. Cellebrite knows which authorities purchased which tools. Cellebrite knows when licenses were activated and in which regions.

If Cellebrite genuinely wanted to determine whether Kenya or Jordan abused its tools, the company could cross-reference the alleged abuse dates with when tools were active in those locations, review customer support logs, or conduct interviews with Kenyan and Jordanian law enforcement officials.

The fact that Cellebrite declines to do this investigation—and refuses to even commit to conducting one—is itself highly informative. It suggests that the company either doesn't want to know the truth or already knows the truth and prefers not to acknowledge it publicly.

Estimated data showing high confidence levels in forensic analysis when multiple evidence types align, suggesting strong evidence in the Jordan investigation.

A Pattern Emerges: Selective Enforcement Across Nations

The Countries Where Cellebrite Did Act

Cellebrite's historical approach to problematic customers includes several examples beyond Serbia:

Bangladesh: Following abuse allegations, Cellebrite cut off relationships with Bangladeshi law enforcement. The country has documented human rights issues, but it's also a relatively small market for forensic tools.

Myanmar: The company suspended sales following the military coup and subsequent allegations of the regime using surveillance technology against activists and journalists. This was a reputational move with minimal financial cost, as Myanmar's law enforcement agencies aren't major Cellebrite customers.

Russia and Belarus: Following the 2021 Ukraine invasion and subsequent Western sanctions, Cellebrite suspended sales to these countries. This decision aligned with U.S. government regulations restricting the export of sensitive technologies and had strong geopolitical backing.

Hong Kong and China: The company stopped selling to Hong Kong authorities following U.S. regulations restricting exports to China. Local activists had accused authorities of using Cellebrite tools against protesters, but Cellebrite framed the decision as compliance with U.S. export controls rather than response to abuse allegations.

Notice the pattern. Cellebrite took action when:

- There was significant Western media attention and human rights organization pressure

- The decision aligned with U.S. government policy or regulations

- The affected market was relatively small or strategically unimportant

- There was plausible deniability (export regulations, not ethics)

The Countries Where Cellebrite Hasn't

Conversely, Cellebrite has maintained relationships with many countries that have documented surveillance and human rights concerns:

Egypt, Thailand, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, and numerous others where human rights organizations have documented phone hacking, torture, and extrajudicial detention. Some of these countries are major law enforcement markets or strategically important to Cellebrite's business.

The message is clear: Cellebrite's accountability is not principled. It's transactional.

The Credibility Problem

What makes Cellebrite's inconsistency particularly damaging is that it undermines the company's credibility on the cases where they do take action.

When Cellebrite suspended Serbia, they cited evidence from Amnesty International. This was presented as the company responding appropriately to credible abuse allegations. But if we now see that Cellebrite ignores nearly identical evidence from a more prestigious research organization when it comes from Jordan, what should we conclude about the Serbia decision?

Possibly that Cellebrite suspended Serbia not because the evidence was convincing, but because suspending Serbia specifically served Cellebrite's business interests.

This creates a moral hazard. Cellebrite can now claim that it takes human rights seriously while simultaneously ignoring human rights abuses. The company gets credit for action taken in one jurisdiction while evading accountability in others. This is exactly how corporate compliance schemes fail—they create the appearance of accountability without the substance.

The Business Incentives That Drive This Behavior

Why Transparency Is Expensive

Cellebrite claims it has a rigorous vetting process for customers. The company says it reviews requests to ensure they come from legitimate law enforcement, conducts due diligence on buyers, and reserves the right to refuse sales.

If this vetting process is genuinely rigorous, releasing the criteria wouldn't be difficult. Cellebrite could publish the standards used to approve customers. The company could disclose how many licenses have been revoked and in which countries. This transparency would actually strengthen Cellebrite's reputation.

The fact that Cellebrite refuses suggests the vetting process is either minimal or inconsistently applied. Publishing the criteria might reveal that authoritarian countries passed the same vetting process as democracies. Disclosing license revocation numbers might show that very few customers ever face consequences, regardless of allegations.

Transparency would require admitting that the company prioritizes sales over ethics. It's much cheaper to simply refuse all requests for information.

The Revenue Model Problem

Cellebrite generates revenue through both direct tool sales and recurring service contracts. A single UFED system costs tens of thousands of dollars. Annual support, updates, and training contracts add ongoing revenue.

When a customer is suspended, the company loses not just the initial sale but all future recurring revenue. A Kenyan police unit that's been using UFED for five years and contracts for support services represents significant annual revenue. Suspending that customer means losing immediate and future income.

For a publicly traded company with quarterly earnings expectations, losing major customers has direct consequences for stock price and executive compensation. Shareholders expect consistent revenue growth. Suspending customers for human rights concerns directly contradicts that expectation.

Cellebrite's board and shareholders have every incentive to permit executives to rationalize continued sales. As long as the company can claim it didn't have conclusive evidence of abuse, or that suspending customers would be disproportionate, or that the situation is complicated, the sales can continue.

The Regulatory Arbitrage

Cellebrite operates in a regulatory gray zone. The tools aren't controlled in most jurisdictions the way weapons or certain encryption technologies are. The company isn't regulated by the same export control regimes as defense contractors.

This creates regulatory arbitrage opportunities. Cellebrite can sell to countries where: Western regulators don't have strong restrictions, where diplomacy makes conflict unlikely, or where the country's strategic importance outweighs human rights concerns.

Kenya exemplifies this arbitrage. The U.S. government considers Kenya a strategic ally in counterterrorism and regional stability. Imposing restrictions on surveillance technology sales to Kenya would conflict with broader foreign policy goals. So instead of restricting sales, the U.S. lets Cellebrite make its own decisions, which predictably result in continued sales.

Meanwhile, Serbia has fewer strategic value and is viewed with more suspicion regarding democratic backsliding. Suspending Serbian customers aligns with broader Western concerns about Serbian governance. It's the kind of policy adjustment that doesn't create diplomatic friction.

Cellebrite's response to the Kenya report was notably silent, contrasting with their dismissive stance on the Jordan report. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Human Cost: Lives Disrupted by Accountability Gaps

Who Gets Targeted

The alleged victims in these cases—the Serbian journalist, the Jordanian activists, the Kenyan politician—weren't randomly selected. They were targeted because of their work.

Journalists investigate government corruption. Activists organize opposition to government policies. Politicians challenge ruling parties. These are the people most likely to be surveilled by authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes.

When authorities hack into their phones, they gain access to:

- Source information and confidential journalistic contacts

- Protest organizer networks and activist collaboration

- Opposition political strategy and communications

- Personal information that can be used for blackmail or intimidation

- Location history that reveals where targets go and who they meet

With this information, authorities can:

- Disrupt journalism by identifying and threatening sources

- Infiltrate activist networks and arrest organizers

- Undermine opposition political campaigns

- Manufacture charges or evidence against targets

- Detain family members or associates to create leverage

Phone hacking isn't a minor intrusion. It's a tool for dismantling civil society, eliminating political opposition, and solidifying authoritarian control.

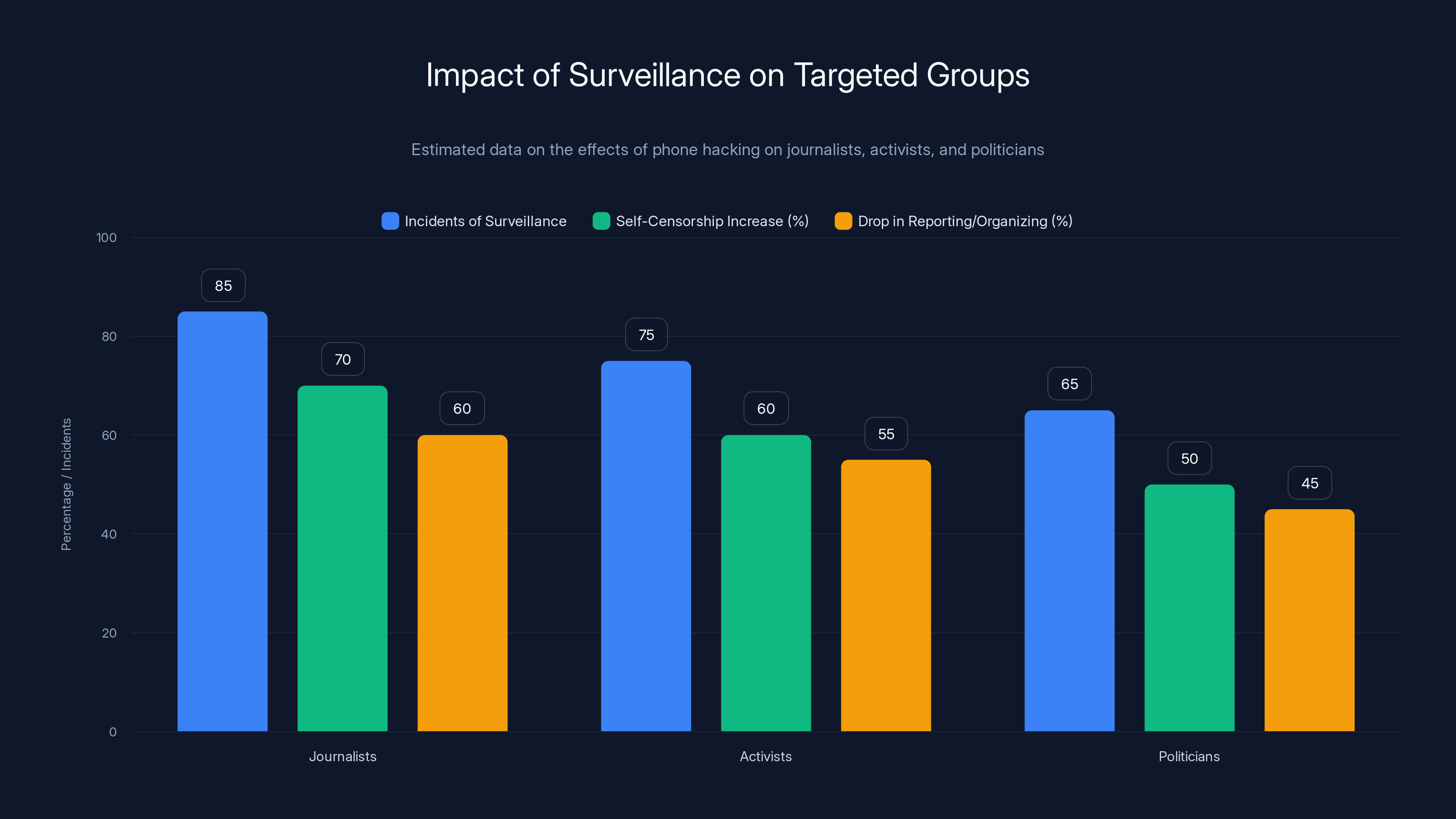

The Chilling Effect

When activists and journalists know that their phones can be easily hacked by authorities, behavior changes. Self-censorship increases. People become reluctant to document government abuses. Journalists drop stories they fear will provoke retaliation. Activists abandon organizing efforts.

This chilling effect is the intended consequence of surveillance tools. Governments use phone hacking not primarily to prosecute crimes, but to maintain control through fear.

Cellebrite's refusal to investigate alleged abuses or hold customers accountable enables this chilling effect. Each time the company sells another UFED unit to an authoritarian regime, each time it refuses to respond to abuse allegations, each time it prioritizes revenue over ethics, it strengthens the tools of repression.

The Victim's Dilemma

When Boniface Mwangi discovered his phone had been hacked, what recourse did he have? The authorities who hacked it are also the authorities that control the legal system. There's no court that will hold them accountable. Kenya has documented rule of law problems, including a judiciary influenced by executive pressure.

Mwangi could report the incident to human rights organizations, which he did. Researchers could publish findings, which Citizen Lab did. But the tools remain in the hands of Kenyan authorities. Cellebrite hasn't suspended them. No government sanctions have been imposed. The phone hacking can continue.

For victims like Mwangi, the accountability gap is deeply personal. The technology used to violate his privacy remains accessible to the authorities who violated it.

The Broader Ecosystem: Who Else Profits From This Gray Zone

Competitors and Alternatives

Cellebrite isn't the only company offering phone unlocking and hacking tools. Competitors include Oxygen Forensics, Belkasoft, and others that offer similar capabilities.

If Cellebrite ever became serious about cutting off abusive customers, those customers would simply buy from competitors. This creates a race to the bottom where the least ethical vendor captures the most problematic customers.

This dynamic actually justifies Cellebrite's reluctance to act. If the company suspends Kenya and that customer buys from a competitor with even fewer ethics safeguards, has Cellebrite improved the situation? Arguably not—they've just lost the market without reducing abuse.

This is a classic collective action problem. Individual companies have little incentive to act unilaterally. Industry-wide standards or government restrictions would be needed to actually reduce abuse.

The Role of Export Controls

The most effective constraint on Cellebrite's sales to problematic customers has been U.S. export controls. When the U.S. government restricts sales to specific countries, even an Israeli company can't easily evade those restrictions without facing consequences.

But export controls are applied inconsistently based on geopolitical considerations, not human rights. The U.S. restricts sales to adversarial countries like Iran and North Korea, but permits sales to allies with human rights concerns like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the Philippines.

So while export controls theoretically could solve the problem, in practice they reflect geopolitical interests rather than humanitarian ones.

The Intelligence Community Factor

There's another dynamic worth considering: many governments using Cellebrite tools are also intelligence partners of Western governments, including the United States.

If the Kenyan intelligence service uses Cellebrite tools, it's quite possible that partnership includes cooperation with U.S. intelligence agencies. Kenya hosts U.S. military personnel, shares intelligence, and operates as part of U.S. counterterrorism strategy.

In this context, criticizing Kenyan surveillance practices or restricting Cellebrite sales to Kenya could jeopardize that partnership. It's a foreign policy calculation where human rights concerns take backseat to strategic interests.

This partly explains why Cellebrite faces no pressure from the U.S. government to investigate Kenyan abuse allegations, while the company faced implicit pressure regarding Serbia (where there are no comparable strategic partnerships).

Estimated data shows high incidents of surveillance among journalists, activists, and politicians, leading to significant increases in self-censorship and drops in reporting or organizing efforts.

The Regulatory Vacuum: Why Nothing Mandates Cellebrite's Accountability

Export Controls Don't Solve It

The U.S. export control system, implemented through the Commerce Department and State Department, theoretically could restrict Cellebrite's sales to countries with known surveillance concerns.

But export controls operate at the country level, not the use case level. The U.S. can restrict sales to Iran broadly, but can't restrict sales to "Kenya, but only to democratic police units and excluding intelligence agencies."

Since Kenya is a strategic ally, broad export restrictions aren't imposed. And without country-level restrictions, Cellebrite can sell freely to any Kenyan agency.

Domestic Laws Vary Widely

Different countries have different laws regarding surveillance tools and accountability. Germany and some European nations have relatively strict requirements for surveillance equipment vendors to exercise due diligence regarding customer use.

The United States has minimal requirements. Companies operating from the U.S. can sell surveillance tools with minimal accountability, as long as they're not exporting to specifically restricted countries.

Israel, where Cellebrite is headquartered, also lacks strong legal requirements for surveillance vendors to investigate customer abuse. Israeli law permits companies to export surveillance tools to most countries.

With operations spanning multiple jurisdictions, Cellebrite can structure its business to minimize compliance burden in any single country.

The Absence of International Standards

There's no international agreement establishing standards for surveillance technology vendors. No UN convention requires companies to investigate abuse allegations or suspend customers based on human rights concerns.

Individual human rights organizations issue principles and guidelines—like the Siracusa Principles or the Johannesburg Principles on national security—but these aren't legally binding.

Without mandatory international standards, companies like Cellebrite can set their own policies, apply them inconsistently, and face no legal consequences.

The Self-Regulation Myth

Cellebrite claims it has a rigorous vetting process and ethical standards for customer approval. This is presented as self-regulation—the company policing itself.

But self-regulation only works if enforcement is consistent and credible. When we observe Cellebrite suspending Serbia but ignoring Jordan and Kenya despite nearly identical evidence, the self-regulation claim loses credibility.

Effective self-regulation requires:

- Transparent standards published in advance

- Consistent application across all customers

- Regular audits by independent evaluators

- Meaningful consequences for violations

- Public reporting of customer suspensions and reasons

Cellebrite has none of these elements. The company refuses to disclose its vetting criteria, applies standards inconsistently, conducts no independent audits, and provides minimal public reporting.

This isn't self-regulation. It's opacity masquerading as accountability.

The Human Rights Response: Why Organizations Keep Investigating

The Citizen Lab's Mission

The University of Toronto's Citizen Lab operates on a simple principle: when surveillance abuse occurs, researchers should investigate and publicize findings.

This work is dangerous. Authorities in countries where surveillance abuse is documented don't appreciate external scrutiny. Researchers have faced harassment, detention, and threats. Yet the Citizen Lab continues publishing findings because without documentation, the abuses can be denied and dismissed.

When Citizen Lab researchers investigate Cellebrite use in Kenya or Jordan, they're not motivated by hostility toward Cellebrite. They're motivated by commitment to documenting human rights abuses and holding powerful actors accountable.

The reports serve multiple purposes:

- Creating a documented record of abuse for victims and their advocates

- Applying public pressure that might constrain authoritarian behavior

- Providing evidence for potential future accountability mechanisms like international courts

- Alerting other researchers and journalists to surveillance patterns

- Pushing companies like Cellebrite to acknowledge problems they'd prefer to ignore

Amnesty International's Approach

Amnesty International conducts similar investigations but with a broader mandate. The organization investigates human rights abuses, documents them, and campaigns for remedies.

When Amnesty published its Serbia report identifying Cellebrite use, the organization didn't stop at documentation. It called for accountability, pushed for policy changes, and engaged directly with Cellebrite about customer conduct.

The fact that Cellebrite responded more positively to Amnesty's Serbia findings than to Citizen Lab's Jordan and Kenya findings suggests that media attention and reputational pressure matter. When Amnesty investigates, European media covers it extensively. When Citizen Lab investigates, coverage is narrower.

This creates perverse incentives for companies to respond to pressure from prestigious Western organizations while ignoring equally credible research from university-based investigators.

Why Advocacy Doesn't Substitute for Accountability

Human rights organizations can document abuses, but they can't directly punish companies or force policy changes. That requires either government action or voluntary corporate compliance.

When government action is unlikely (due to geopolitical interests), and corporate compliance is inconsistent (due to market incentives), human rights organizations can only apply pressure and hope.

This is fundamentally unequal. Cellebrite has all the power: the company controls who buys the tools, can investigate customers directly, can suspend sales, can disclose information to authorities. Human rights organizations must depend on public pressure and media coverage.

For victims like Boniface Mwangi, this asymmetry means that even when abuse is documented and publicized, the tools remain in the hands of the authorities who misused them.

Future Scenarios: What Accountability Could Look Like

Scenario 1: Regulatory Mandates

Governments could require that surveillance technology vendors:

- Disclose vetting criteria publicly

- Report all customer suspensions and reasons

- Conduct independent audits of customer use

- Establish mechanisms for reporting abuse

- Implement kill switches that disable tools in specific jurisdictions if abuse is documented

This would require new legislation in multiple countries and international cooperation. It faces opposition from companies and governments that benefit from surveillance technologies.

But this approach would directly address the accountability gap. Companies couldn't simply ignore abuse allegations or apply standards inconsistently.

Scenario 2: Market-Driven Change

Institutional investors increasingly care about environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics. If major pension funds and investment managers demanded that Cellebrite demonstrate rigorous human rights due diligence, the company would face financial pressure.

Similarly, if law enforcement agencies in Western democracies refused to buy from companies that had documented abuse in other countries, Cellebrite would face market consequences.

But this requires coordination and pressure that hasn't materialized. Law enforcement agencies want the tools regardless of ethical questions. Institutional investors have shown limited willingness to divest from surveillance companies.

Scenario 3: Litigation and Accountability Mechanisms

Victims of surveillance abuse could sue Cellebrite in jurisdictions with favorable legal standards. If courts ruled that the company had liability for knowing customer abuse, it would change the incentive structure.

Alternatively, international courts or tribunals could find that surveillance tool providers bear some responsibility for abuses. This would set precedent for future accountability.

But international litigation is slow, expensive, and faces numerous jurisdictional barriers. Companies like Cellebrite have resources to fight cases indefinitely.

Scenario 4: Industry Standards

The surveillance technology industry could adopt voluntary standards requiring all companies to investigate abuse allegations, apply standards consistently, and report publicly on enforcement.

But industry self-standards only work if enforcement is credible. Without mandatory participation and independent verification, companies can simply opt out.

This is the scenario that seems least likely, given that industry standards would reduce profit margins and constrain companies' ability to sell to problematic customers.

The Broader Question: Who Should Control Digital Access Technologies

The Legitimacy Problem

When government authorities hack into phones without warrants, without legal authorization, and without accountability, they're claiming access to private data that courts would likely refuse to authorize.

This raises a fundamental legitimacy question: should any organization have the power to bypass privacy protections and access digital information without authorization?

In democracies with functional rule of law, the answer is carefully constrained: law enforcement can access data with a warrant. Intelligence agencies operate under some oversight. There are at least theoretical limits.

But in countries with weak rule of law, that constraint disappears. Once authorities have Cellebrite tools, they can use them as they wish with no meaningful oversight.

Cellebrite's existence enables this power asymmetry. By selling to all governments without meaningful distinction, the company distributes tools that empower repression.

The Inevitable Tension

There's an inherent tension in this market. Cellebrite claims to serve law enforcement, which is a legitimate function in any society. But the tools are equally useful for authoritarians, democracies, and everyone in between.

Companies can't realistically distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate use in advance. Once sold, the tools will be used according to the purchaser's values and constraints, not the vendor's preferences.

This is why some technologists and human rights advocates argue that certain tools shouldn't be sold at all. If the technology is primarily useful for surveillance and control, and if it can't reliably be constrained to legitimate uses, maybe it shouldn't exist.

But that's an unrealistic position in a market economy. If Cellebrite doesn't sell the tools, competitors will. If all Western companies refused, other nations' companies would serve the market.

The tension persists because there's no clear solution, only tradeoffs between access and control, innovation and constraint, market freedom and social responsibility.

What Different Stakeholders Want

Democratic governments want surveillance tools to investigate crime and terrorism, but don't want other democracies using them abusively. They also don't want adversaries having the tools. This creates contradictions.

Authoritarian governments want surveillance tools to maintain control and suppress opposition. For them, this is a core function of the tools.

Companies want to sell tools to anyone, anywhere, with minimal constraints, because constraints reduce profits.

Human rights advocates want tools restricted to legitimate law enforcement with strong oversight. They recognize this is unrealistic but push anyway.

Victims of surveillance want the tools restricted or destroyed entirely, or at minimum want accountability when they're abused.

These interests are mostly incompatible. There's no policy that simultaneously satisfies all parties.

The Serbia Decision in Retrospect: Was It Principled or Strategic

The Evidence

When Cellebrite suspended Serbian customers, the company cited Amnesty International's findings. Amnesty had documented abuse using forensic analysis and technical investigation. The findings were credible and well-publicized.

But if we now observe that Cellebrite ignores nearly identical evidence from Kenya and Jordan, what does that tell us about the Serbia decision?

One possibility is that it was genuinely principled: Cellebrite realized Serbian authorities were abusing tools, concluded that continuing sales was unethical, and suspended the relationship despite financial cost.

But several factors suggest otherwise:

- Market size: Serbia is a small market with limited profitability compared to Kenya or Jordan

- Geopolitical context: Serbia is viewed skeptically by Western governments; Kenya and Jordan are allies

- Reputational calculation: Suspending Serbia generates positive press with minimal cost; suspending Kenya would create diplomatic friction

- Precedent avoidance: By never responding to similar allegations in other countries, Cellebrite avoids setting precedent that would require similar action elsewhere

- Inconsistent standards: The company uses different evidentiary standards for different cases, suggesting standards are chosen to reach predetermined conclusions

When a company applies standards inconsistently, it indicates the standards aren't actually driving decisions. Instead, other factors (profit, geopolitics, reputation) drive decisions, and standards are invoked selectively to justify them.

The Credibility Cost

Cellebrite paid a significant credibility cost for suspending Serbia while ignoring Kenya and Jordan. Human rights organizations that praised the Serbia decision now view the company as hypocritical.

John Scott-Railton's public statement—calling on Cellebrite to justify the inconsistency—crystallizes the problem. The company can't claim to take human rights seriously while applying different standards based on market size and geopolitics.

But from a business perspective, the cost of hypocrisy is lower than the cost of principle. The company sacrifices some credibility with human rights advocates (who weren't major customers anyway) while maintaining revenue from strategically important markets (Kenya, Jordan, and others with similar concerns).

This is a rational business decision if you're willing to accept being viewed as hypocritical. And Cellebrite clearly is.

The Road Forward: Pressure Points and Leverage

Where International Pressure Could Work

Countries that care deeply about internet freedom and digital rights—including Germany, many Nordic countries, Canada, and others—could impose export controls on surveillance technology.

If several countries coordinated to restrict Cellebrite sales to specific problematic nations, the company would face real constraints. But this requires political will and coordination that currently doesn't exist.

The U.S., which has the most leverage through export controls, has shown little willingness to restrict sales based on human rights concerns, especially when customers are strategic allies.

Law Enforcement Standards

Large law enforcement agencies in democracies could refuse to purchase from companies that haven't demonstrated rigorous human rights vetting.

If the FBI, European policing agencies, and others collectively demanded transparency and accountability, Cellebrite would face market pressure. But law enforcement is often technologically conservative and unwilling to advocate for restrictions that might reduce their own tool options.

Institutional Investment Pressure

Cellebrite is owned by private equity firm Thoma Bravo. Institutional investors with ESG commitments could pressure Thoma Bravo to demand better human rights standards from its portfolio companies.

But private equity firms are generally skeptical of constraints that reduce profitability. Thoma Bravo would need to face significant investor pressure to push Cellebrite toward greater accountability.

Civil Society Persistence

Organizations like Citizen Lab and Amnesty International will continue investigating surveillance abuse. They'll continue publishing findings. They'll continue applying pressure on companies and governments.

This work is valuable, but it's also limited. Without enforcement mechanisms or market consequences, companies can ignore pressure and continue problematic practices.

Human rights advocacy is necessary but insufficient without systemic change.

Technology Solutions

In the longer term, stronger device encryption, better security hardening, and technological barriers to phone unlocking might reduce the effectiveness of tools like Cellebrite.

But companies like Apple and Google face political pressure to provide law enforcement access, limiting how far they can go in locking down devices. This tension will persist.

Conclusion: Accountability in a Gray Zone

Cellebrite's decision to suspend Serbian customers while ignoring nearly identical abuse allegations in Jordan and Kenya reveals a fundamental tension in how technology companies navigate ethics and profit.

The company claimed to take human rights seriously. It positioned itself as a responsible vendor of law enforcement tools. But when applying its principles required sacrificing major markets, the company revealed its true priorities.

This isn't unusual. Most companies that claim ethical standards apply them inconsistently when ethics conflict with profit. What makes Cellebrite notable is the transparency of the double standard.

When asked why it treats similar allegations differently in different countries, the company essentially responds: "because it's convenient for us to do so." This level of candid inconsistency is rare and, in its own way, clarifying.

For Boniface Mwangi in Kenya, for activists in Jordan, for anyone whose phone is hacked by authorities using Cellebrite tools, the inconsistency is deeply personal. The tools remain in the hands of their abusers. Cellebrite faces no consequences. The authorities who violated their privacy continue operating.

This is what accountability failure looks like in practice. It's not dramatic or complex. It's simply that powerful actors prioritize profit over principles, apply standards selectively, and face no meaningful consequences for inconsistency.

Changing this would require:

- Mandatory transparency: Companies must disclose vetting criteria and enforcement actions publicly

- Consistent standards: Similar allegations must receive similar responses regardless of market considerations

- Independent oversight: External audits of vendor practices, not self-regulation

- Market consequences: Law enforcement agencies refusing to purchase from vendors with documented inconsistency

- Regulatory frameworks: Government restrictions on sales to countries with documented surveillance abuse

None of these currently exist. Until they do, Cellebrite and similar companies will continue operating in the accountability gray zone, where principle takes a backseat to profit.

For now, the message is clear: if you live in a strategically important country, or if your government can make profitable threats, Cellebrite will potentially investigate allegations against you. If you live elsewhere, you're on your own.

It's not justice. But it's how the surveillance technology market currently works.

FAQ

What is Cellebrite and what does it do?

Cellebrite is an Israeli-headquartered company that develops forensic tools for law enforcement, most notably the UFED (Universal Forensic Extraction Device). These tools can extract data from locked or damaged mobile phones, giving law enforcement access to messages, location history, photos, and other private information stored on devices.

How do researchers prove that Cellebrite tools were used to hack phones?

Researchers use digital forensic analysis to identify signatures characteristic of Cellebrite extraction. They look for specific application artifacts, files signed with Cellebrite's digital certificates, and patterns that match known samples from the UFED tool. When these multiple indicators align, forensic analysts classify it as "high confidence" identification that Cellebrite tools were used.

Why did Cellebrite suspend Serbian customers but not Jordanian or Kenyan ones?

Cellebrite cited human rights abuse allegations for the Serbia suspension, which followed a high-profile Amnesty International report. However, when nearly identical abuse allegations emerged in Jordan and Kenya with evidence from the Citizen Lab, Cellebrite dismissed the findings as "speculation" and refused to investigate. The inconsistency suggests business considerations—market size, geopolitical importance, and strategic partnerships—influence which customers face accountability rather than consistent application of ethical standards.

What is the difference between "high confidence" and "direct evidence" in digital forensics?

"High confidence" means that multiple technical indicators point to a specific tool or actor, making alternative explanations extremely unlikely. "Direct evidence" would mean having unambiguous proof like logs or testimony. In surveillance abuse cases, direct evidence is nearly impossible to obtain because the authorities committing abuse also control the evidence. High confidence identification is the standard used by forensic analysts, academic researchers, and international investigators.

How many countries does Cellebrite serve, and who are its typical customers?

Cellebrite claims to have over 7,000 law enforcement customers across more than 150 countries. Customers include national police forces, detective bureaus, border agencies, intelligence services, and federal law enforcement organizations. The company generates approximately $360 million in annual revenue from tool sales and recurring service contracts.

What happens to someone whose phone is hacked using Cellebrite tools?

Authorities gain access to all data on the device: encrypted messages, location history, banking information, private photos, email accounts, and browsing history. In cases documented by human rights researchers, this information has been used to identify sources, infiltrate activist networks, manufacture charges against political opposition, and enable blackmail or intimidation. The data breach occurs without the phone owner's knowledge or consent, and in many cases without any legal authorization.

Are there regulations or export controls on surveillance tools like Cellebrite?

Regulations vary by country. The U.S. restricts exports of sensitive technologies to specific adversarial countries through export control systems, but allies like Kenya and Jordan typically aren't restricted. Europe has some requirements for surveillance vendor due diligence, but enforcement is inconsistent. There are no comprehensive international standards requiring surveillance vendors to investigate abuse allegations or maintain consistent ethical standards across all customers.

What would meaningful accountability for Cellebrite look like?

Meaningful accountability would include mandatory disclosure of vetting criteria, public reporting of all customer suspensions and reasons, independent audits of customer use, consistent application of standards regardless of market size or geopolitical importance, and consequences for abuse (either through customer suspension, government restrictions on sales, or legal liability). Currently, Cellebrite provides none of these elements.

Runable CTA Section

While we can't control how surveillance technology companies choose to enforce their own standards, we can empower teams to operate more transparently and efficiently through better automation and documentation practices.

Use Case: Automating human rights investigation documentation and creating standardized reports from evidence collection with AI assistance

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- Cellebrite suspended Serbian customers after Amnesty International documented phone hacking abuse, but dismissed nearly identical evidence from Citizen Lab in Jordan and Kenya

- Researchers use digital forensics—analyzing cryptographic signatures, application artifacts, and VirusTotal correlations—to prove Cellebrite tool usage with high confidence

- The company's inconsistent enforcement suggests business calculations (market size, geopolitical importance) influence accountability decisions more than evidence quality

- With 7,000+ law enforcement customers globally and minimal regulatory oversight, Cellebrite operates in an accountability gap where victims have few recourse options

- Meaningful accountability would require mandatory transparency, consistent standards across all customers, independent audits, and regulatory restrictions on sales to problematic nations

Related Articles

- Ring Cancels Flock Deal After Super Bowl Ad Sparks Mass Privacy Outrage [2025]

- Russia's Telegram Ban Disrupts Military Operations in Ukraine [2025]

- Iran VPN Crisis: Millions Losing Access Due to Funding Collapse [2025]

- Why Epstein's Emails Have Equals Signs: A Technical Deep Dive [2025]

- Robot Dogs on Patrol: The Future of Sports Security at 2026 World Cup [2025]

- Social Security Data Handover to ICE: A Dangerous Precedent [2025]

![Cellebrite's Double Standard: Phone Hacking Tools & Human Rights [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/cellebrite-s-double-standard-phone-hacking-tools-human-right/image-1-1771540616222.jpg)