Ring Cancels Flock Deal After Super Bowl Ad Sparks Mass Privacy Outrage

There's a moment when a brand accidentally tells the truth. That's what happened when Amazon aired what was supposed to be a heartwarming Super Bowl commercial about finding lost dogs, but instead became a chilling portrait of mass surveillance infrastructure.

The ad looked innocent enough on the surface. A young girl receives a puppy as a gift. The narrator mentions that 10 million dogs go missing annually. Ring's new "Search Party" feature would use AI to activate searchlights across entire neighborhoods, supposedly to help find those missing pets. Except there was one frame that changed everything.

In that single shot, the technology stopped being about dogs. Neighbors' Ring cameras instantly activated. Their images illuminated. The infrastructure became visible. And for the first time, millions of Americans watching the Super Bowl saw what privacy advocates had been warning about for years: a seamless, AI-powered system designed to identify and track anyone moving through public space.

Senator Ed Markey called it what it was. Not a dog-finding feature. Mass surveillance technology dressed up in emotional storytelling. "This is definitely not about dogs," he said in correspondence with Amazon CEO Andy Jassy. The backlash that followed wasn't just complaints on social media. Ring customers posted videos of themselves destroying their own cameras. Subreddits filled with refund requests. Privacy advocates mobilized. And less than two weeks after the ad aired, Amazon and Flock Safety announced they were canceling their partnership entirely.

But here's what matters: this wasn't an isolated marketing mistake. This was a moment when the veil slipped on how facial recognition technology and biometric data collection have quietly embedded themselves into the infrastructure of American neighborhoods. And it revealed something else entirely: that when people actually see how the technology works, they reject it.

What Happened With The Ring And Flock Partnership

Amazon's partnership with Flock Safety was announced last October as a "coming soon" integration. On the surface, it sounded reasonable. Flock operates a network of traffic cameras and automated license plate readers across the United States. Ring, meanwhile, has installed millions of cameras in residential neighborhoods. Together, they would create something unprecedented: the ability to instantly cross-reference video footage from private residential cameras with Flock's law enforcement-focused surveillance network.

The integration was meant to be quiet. It would happen in the background, the kind of business deal that might get buried in tech news and go unnoticed by the general public. But the Super Bowl ad changed that calculation entirely. When you're showing your technology to 100 million people, the assumptions you made in a corporate boardroom get tested against actual human values.

What Ring and Flock apparently didn't anticipate was how differently people would react when they actually saw the capability visualized. The ad showed Ring cameras across an entire neighborhood instantly activating at once, creating a coordinated surveillance response. It was efficient. It was coordinated. It was also genuinely unsettling to watch.

The problem wasn't that people didn't understand what the technology did. The problem was that they understood it perfectly. They grasped immediately that the same system could be used for purposes other than finding lost dogs. Immigration enforcement. Police tracking. Political opposition surveillance. The technology doesn't care about intent. It just activates.

Within days, the partnership fell apart. Both companies released statements claiming the integration would require "significantly more time and resources than anticipated" and that "no Ring customers' videos were ever sent to Flock." But both statements conspicuously avoided acknowledging what actually happened: the public saw the technology, understood its implications, and rejected it.

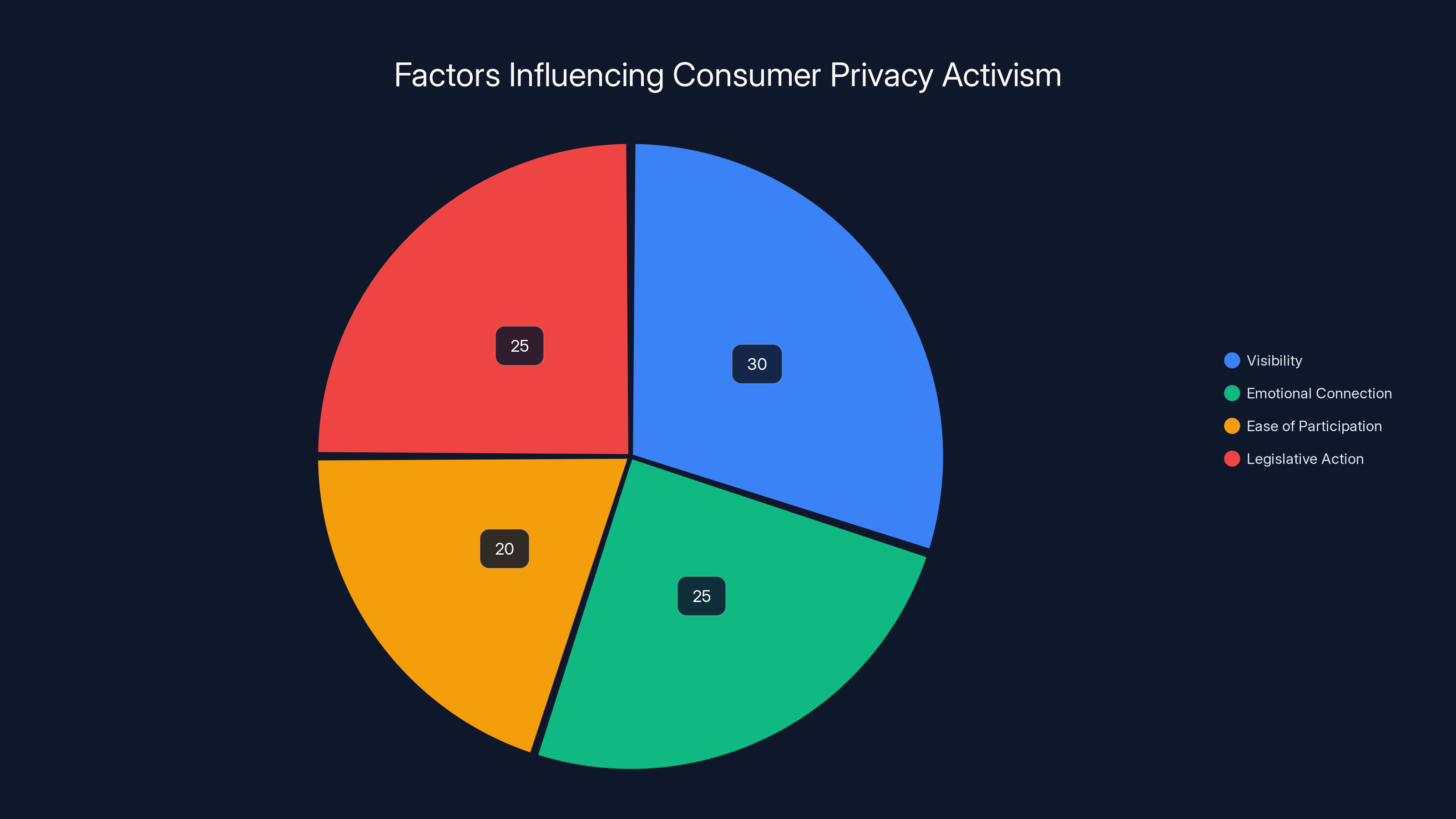

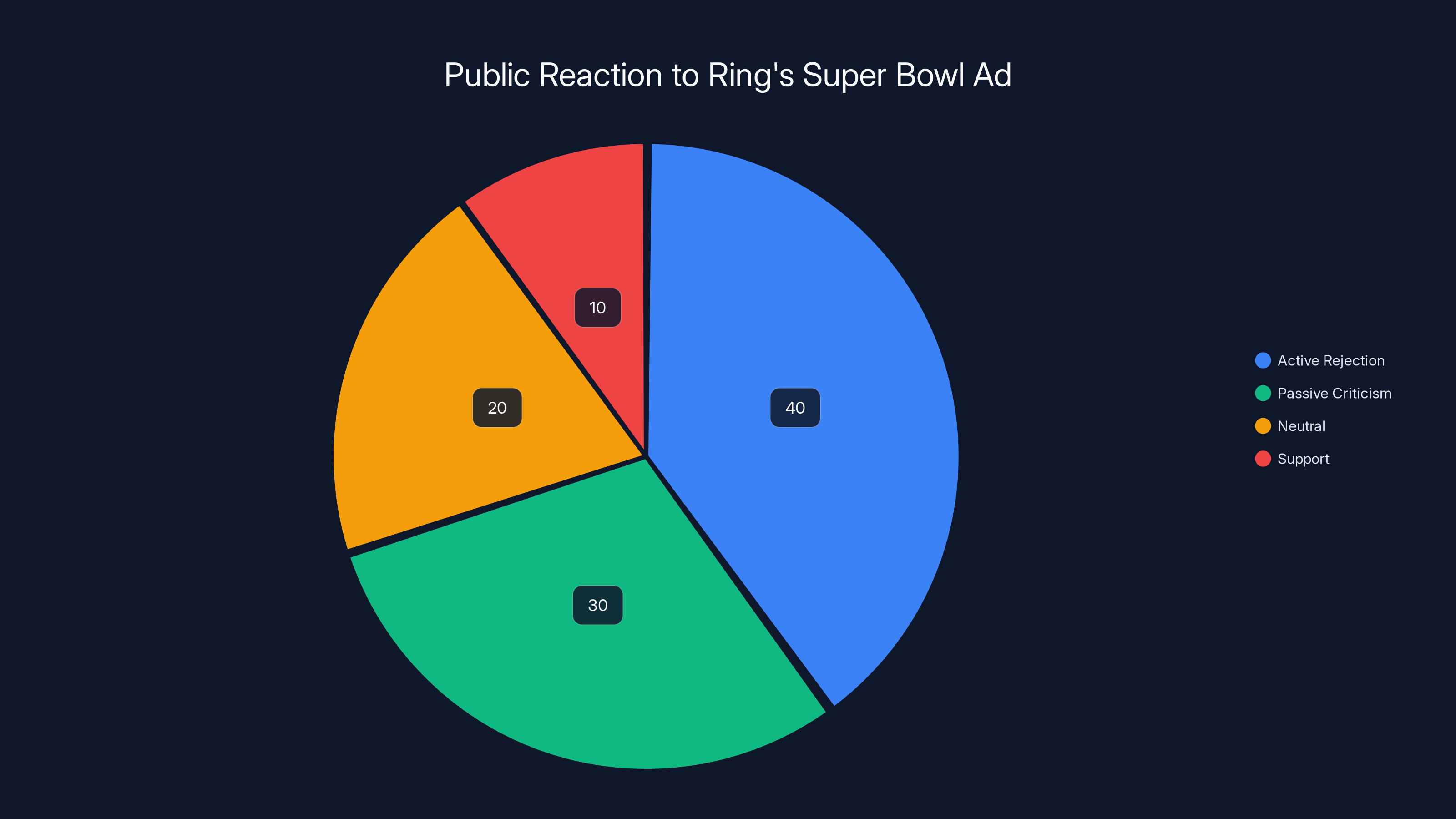

Visibility, emotional connection, and ease of participation are key factors in consumer privacy activism, but legislative action is equally crucial for systemic change. Estimated data.

The Technology Behind Ring's Biometric Data Collection

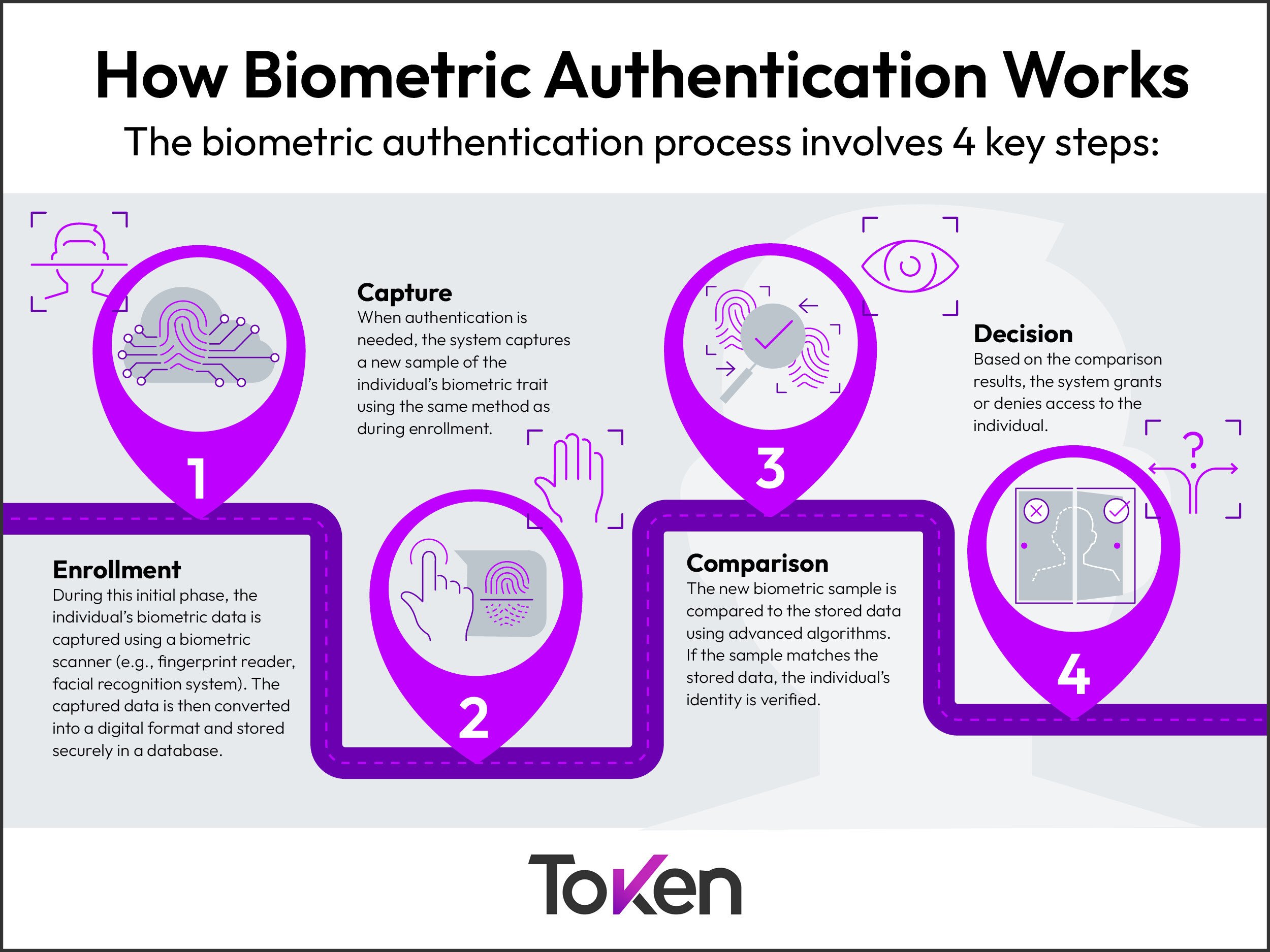

Most people who own Ring cameras think they're buying a doorbell. What they're actually buying is participation in a biometric data collection system. Understanding this distinction matters because it's the difference between a consumer product and surveillance infrastructure.

Ring cameras don't just record video. They extract biometric information from that video. Facial geometry. Iris patterns. The way you walk. The shape of your face. All of this data is stored indefinitely unless you actively request deletion. And here's the part that should concern you: the people in those videos don't need to consent. They don't need to know.

If you live in a Ring-equipped neighborhood, your face is being scanned, analyzed, and stored. You might not own a Ring camera. You might not have agreed to anything. But your neighbor did, and now your biometric profile exists in Ring's systems.

This is where Ring's "Familiar Faces" feature comes in. Rolled out to normalize facial recognition on a consumer product, it allows Ring owners to upload photos of people they want to recognize (family, delivery drivers, etc.) and then automatically identify them when they appear on camera. Sounds convenient until you think about the inverse: Ring's systems are already learning to identify unfamiliar faces too. They're building a catalog of who lives in, visits, and passes through your neighborhood.

Senator Markey raised a crucial point in his letter to Amazon: Ring owners can retain these biometric scans indefinitely with no oversight. And if someone wants their data deleted, there's no simple mechanism. They have to go door to door requesting that their face be removed from each Ring camera individually. It's deliberately cumbersome. It's designed to discourage opt-outs.

The real innovation here isn't the cameras themselves. It's the infrastructure that processes the data. Ring's AI systems analyze video 24/7, extracting faces, identifying patterns, creating behavioral profiles. This happens automatically. This happens at scale. And this happens to people who never agreed to it.

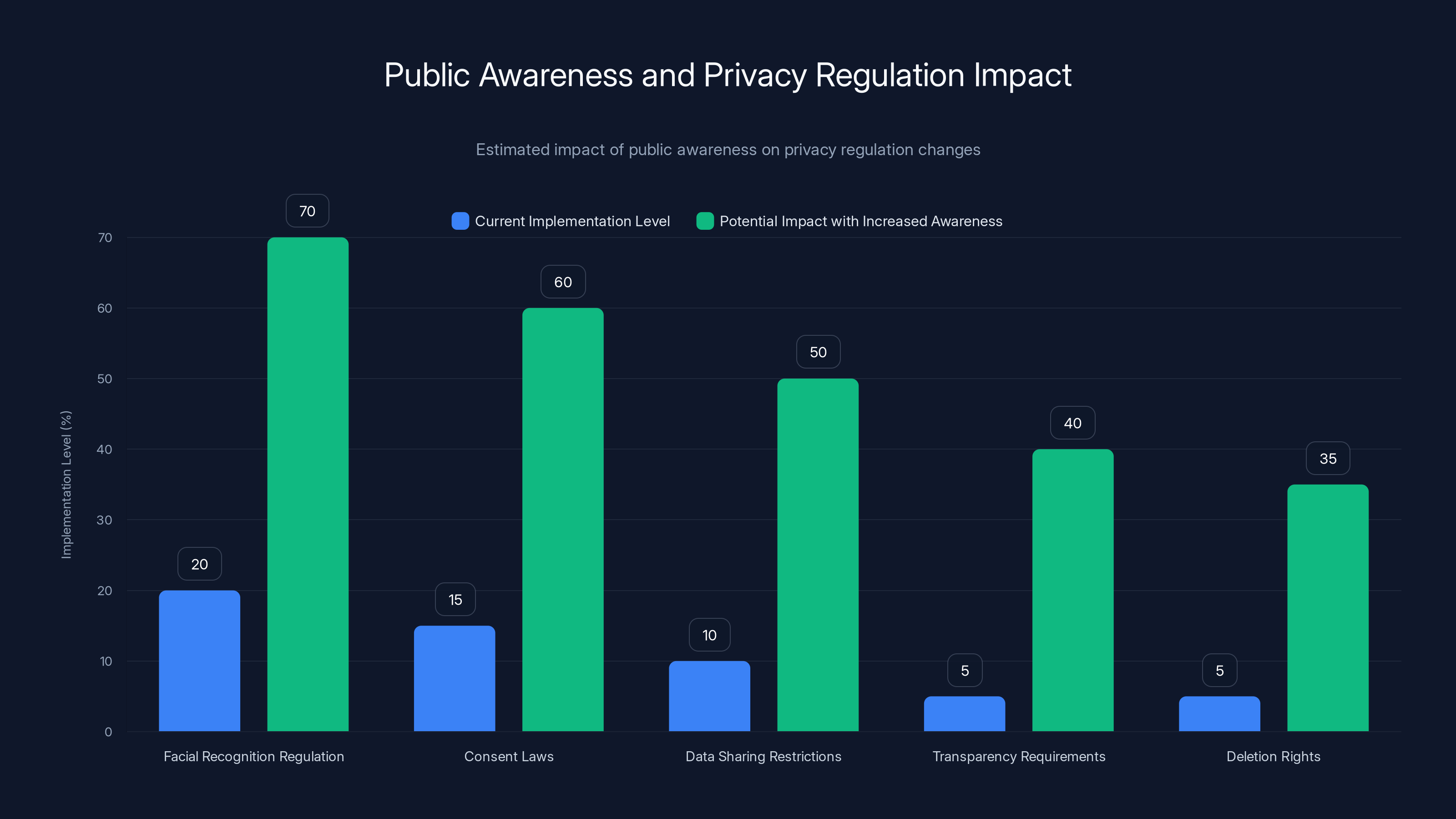

Estimated data shows that increased public awareness could significantly boost the implementation of privacy regulations, potentially increasing current levels by 50% or more.

How The Super Bowl Ad Became A Privacy Wake-Up Call

Advertising is supposed to make you want something. The Ring ad did the opposite. It made people horrified by what they were seeing.

This is unusual enough that it's worth understanding why it happened. Most surveillance technology advocacy fails because it's abstract. Explaining facial recognition technology at policy hearings doesn't capture people's attention. Writing detailed privacy briefs doesn't go viral. But showing Americans what their neighborhood surveillance infrastructure actually looks like, visualized in a Super Bowl commercial watched by 115 million people, that worked.

The frame that broke it was simple but devastating. Dozens of Ring cameras illuminating simultaneously. A coordinated network. An automated response. The visualization did what a thousand policy papers couldn't: it made the abstract concrete. It showed the infrastructure. It showed what it looked like when your neighborhood became a surveillance system.

What Ring learned the hard way is that people's privacy intuitions are often more sophisticated than companies assume. People understood immediately that this technology could be repurposed. They didn't need to be experts in facial recognition to see that a system designed to identify lost pets could equally identify suspects, track protesters, or monitor immigration patterns.

The backlash was swift and coordinated in a way that surprised corporate leadership. Ring customers weren't just complaining in comments. They created videos showing themselves destroying Ring cameras and smashing them on camera. They organized refund requests. They posted detailed instructions on Reddit about how to return devices. This wasn't passive criticism. This was active rejection.

One factor that amplified the response was timing. This happened during Super Bowl Sunday, when political figures were watching alongside regular consumers. Senator Ed Markey wasn't working from an obscure policy paper. He was watching the same ad as millions of other Americans and seeing the same unsettling implications they did. His letter to Amazon CEO Andy Jassy wasn't a delayed response to a quarterly report. It was a direct reaction to what had just aired on television.

That combination—mass audience, immediate reaction, and political validation—created a feedback loop that Amazon couldn't control. Each piece of criticism generated more coverage. Each news story generated more customer concerns. Each customer concern generated more political scrutiny. Within 13 days, the partnership was dead.

The Flock Safety Network And Law Enforcement Integration

To understand why this partnership mattered, you need to understand what Flock actually is. Flock Safety isn't a consumer company. It's enterprise infrastructure for law enforcement. The company operates a network of high-resolution traffic cameras and automated license plate readers across thousands of jurisdictions in the United States.

Flock's value proposition to police departments is straightforward: solve crimes faster. When someone commits a crime, law enforcement can query Flock's database and find every vehicle that was in a specific area at a specific time. License plate readers instantly identify the vehicles and their owners. This works. It works very well. And it's used thousands of times per month across the United States.

But automated license plate readers are just the beginning. Flock has been expanding into facial recognition. The company has been testing the ability to identify individuals from video footage, expanding beyond vehicle identification into person identification. This is where the Ring partnership became dangerous.

By connecting Ring's neighborhood camera network to Flock's law enforcement query systems, Amazon would have created something unprecedented in the United States: the ability for police to instantly search residential video footage across entire cities. Want to find everyone who walked past a specific address during a specific hour? Query the network. Want to identify protesters at a specific rally? Query the network. Want to track movement patterns of individuals law enforcement is interested in? Query the network.

The technology doesn't distinguish between legitimate law enforcement uses and inappropriate surveillance. It just processes the data. Scope creep is built in because each new law enforcement use case is justified individually while the infrastructure grows continually.

During the backlash, civil liberties organizations pointed out that Flock's systems have been used to surveil Black Lives Matter protests, immigrant communities, and political activists. The company maintains that they have policies against such use. But policies written after deployment are less effective than designing systems with restrictions built in from the start.

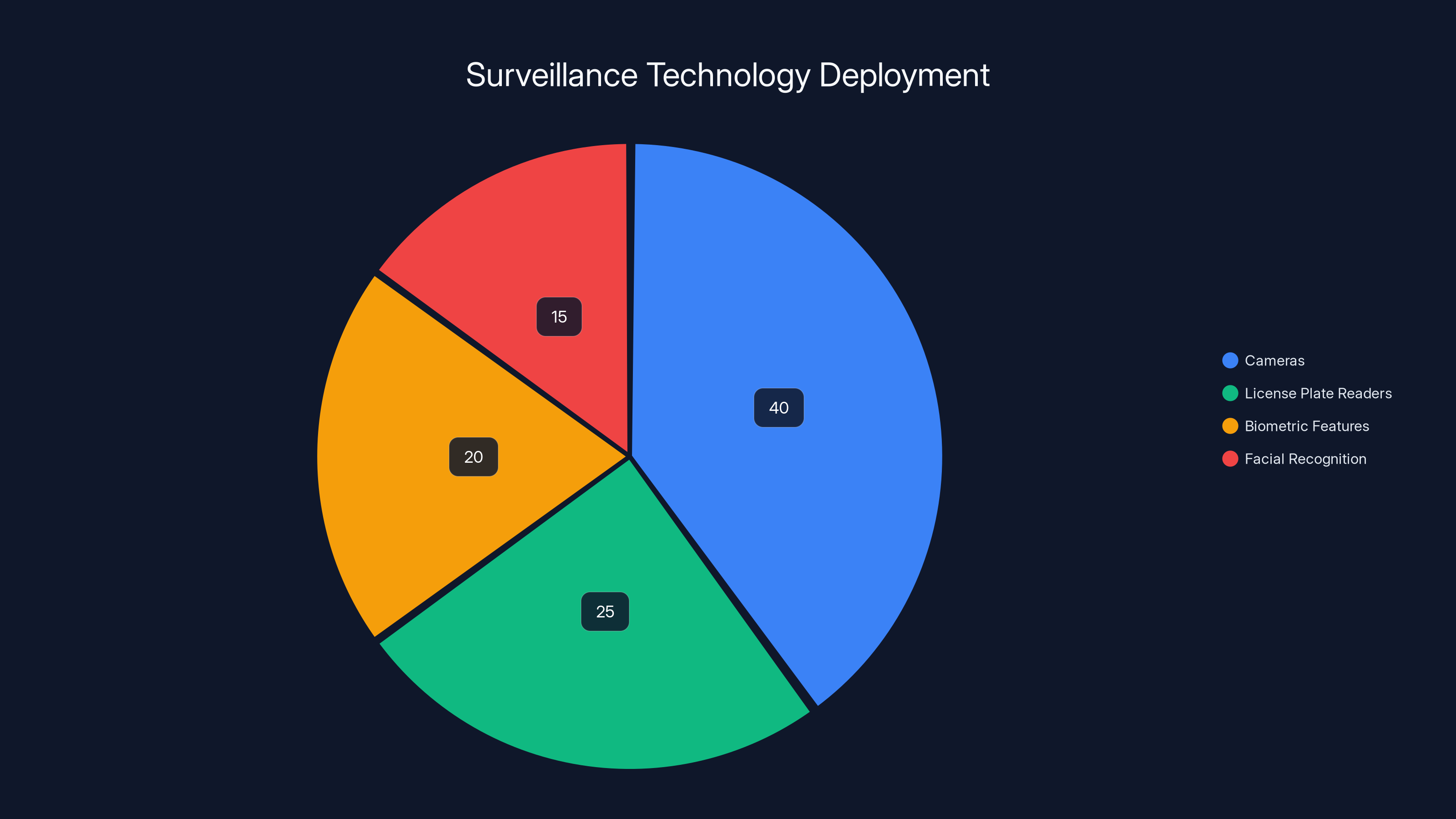

Estimated data shows cameras are the most common surveillance technology in urban areas, followed by license plate readers and biometric features.

Why Ring's Statement Missed The Point

After canceling the Flock partnership, Ring released a statement that said basically nothing. The company claimed that after "comprehensive review," they determined the integration would require "significantly more time and resources than anticipated." Translation: we got caught, we're backing away, we're not going to talk about why.

What's remarkable about Ring's non-explanation is what it doesn't acknowledge. It doesn't mention the Super Bowl ad controversy. It doesn't mention Senator Markey's letter. It doesn't mention the customer backlash or the videos of people destroying Ring cameras. It doesn't address privacy concerns at all. It just says the project was too complicated.

Cybersecurity researcher John Scott-Railton from the Citizen Lab called this out directly. He posted a side-by-side image: Ring's creepy Super Bowl ad frame on the left, and Ring's statement claiming they're not doing mass surveillance on the right. "The company cannot have it both ways," he wrote. You can't show America your surveillance infrastructure in a Super Bowl commercial and then claim you're prioritizing privacy in your press releases.

What Ring's statement reveals is a corporate strategy for handling backlash: disappear the controversy, reframe it as a logistical issue, and move forward as if nothing happened. The problem with this approach is that it doesn't address what people actually learned. People watched Ring's own advertisement and understood what the technology could do. A press release saying the project was complicated doesn't undo that knowledge.

Flock's statement was equally hollow. The company said the decision "allows both companies to best serve their respective customers and communities." But Flock's customers are law enforcement agencies. And from a law enforcement perspective, an integration that wasn't happening is not serving their interests. Flock's statement suggests this was a mutual, amicable decision. But the timing—literally days after the Super Bowl ad backlash—makes clear it was anything but.

The only hint that Ring understood public sentiment came in the very last line of their blog post: "We'll continue to carefully evaluate future partnerships to ensure they align with our standards for customer trust, safety, and privacy." But these are the same standards that allowed them to deploy biometric collection infrastructure without consent. These are the same standards that enabled indefinite retention of facial scans. These are the same standards that required customers to go door-to-door requesting data deletion.

Saying you'll evaluate partnerships against your standards for privacy is meaningless if your standards are inadequate to begin with.

The Broader Implications For Surveillance Technology

What happened with Ring and Flock matters far beyond these two companies. This was a moment when the private sector's surveillance ambitions collided with public sentiment, and the public won. That doesn't happen often.

Most surveillance technology deployment happens quietly. A police department adds cameras. A city installs license plate readers. A company releases a new biometric feature. Each decision seems reasonable in isolation. But the accumulation creates an infrastructure that can enable authoritarian practices even in democratic societies.

What the Ring ad did was compress years of incremental surveillance expansion into a single 60-second visualization. It forced people to see the totality of what the infrastructure could do. And that visualization changed minds.

Other tech companies are definitely watching. When Amazon, the second-largest technology company in the world, cancels a lucrative partnership due to privacy backlash, that sends a message. It means public opposition can actually change corporate decisions. It means surveillance infrastructure isn't inevitable. It means that sometimes, when enough people say no, the projects stop.

But there's a dangerous flip side to this victory. Having canceled the Flock partnership publicly, Ring can now claim it's prioritizing privacy. The company can point to this decision and say: "Look, we listened to concerns." And then proceed with developing increasingly invasive biometric technologies under the assumption that they've addressed the trust problem.

Ring is still deploying facial recognition. Ring is still collecting biometric data without consent. Ring is still retaining facial scans indefinitely. The Flock partnership might be dead, but the underlying surveillance infrastructure is not just alive, it's expanding.

What actually changed is that Ring paused one specific integration. The company didn't fundamentally reconsider its approach to biometric collection. It didn't introduce transparency mechanisms. It didn't offer customers meaningful consent for data collection. It didn't guarantee data retention limits. It just canceled the one partnership that made the surveillance infrastructure too visible.

That's a distinction worth understanding. Success in pushing back on one specific project is not the same as success in changing corporate surveillance practices more broadly.

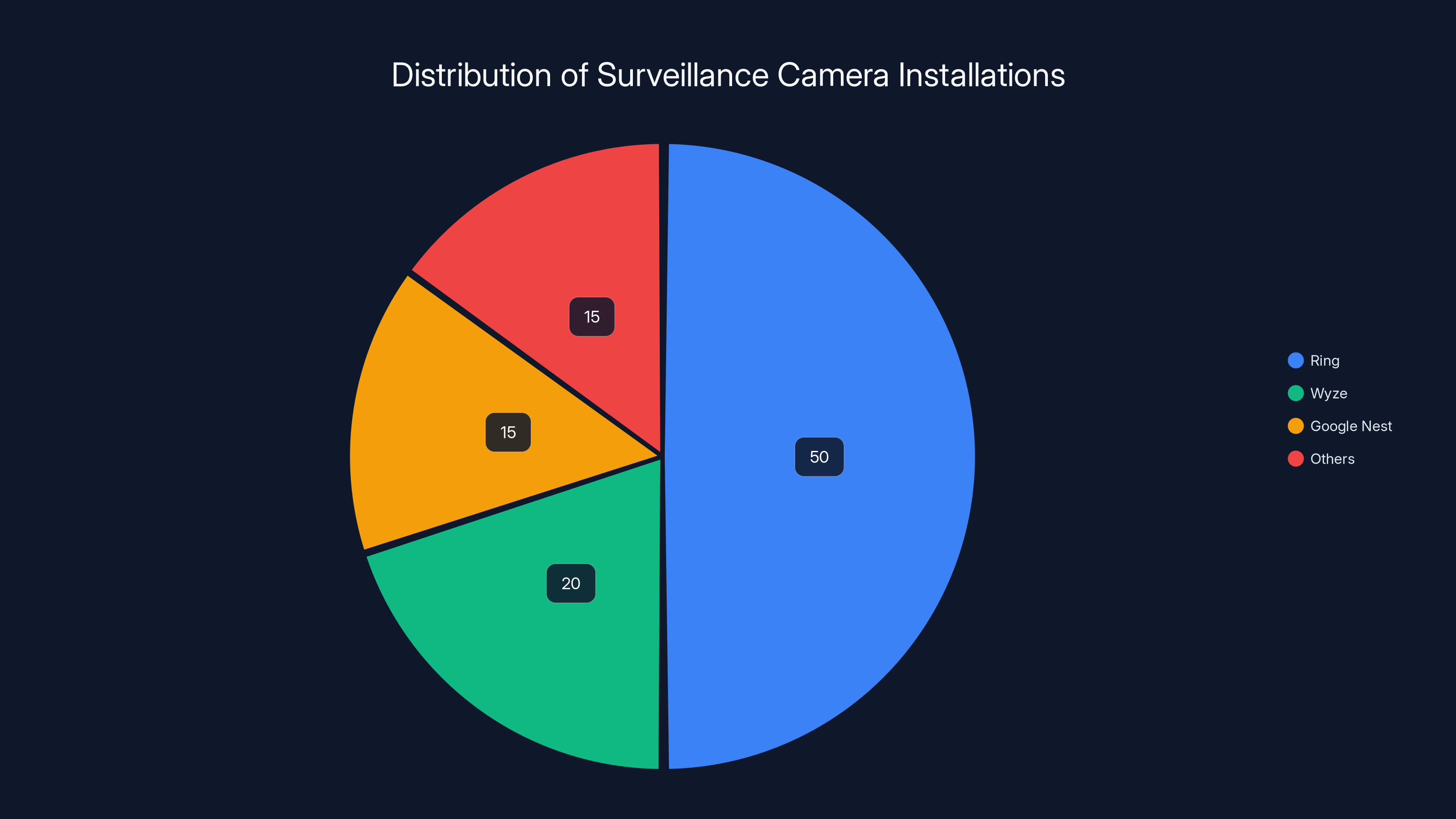

Ring dominates the residential surveillance market with an estimated 50% share, largely due to partnerships with law enforcement. Estimated data.

Why The Technology Is So Appealing To Law Enforcement

Flock Safety exists because law enforcement agencies want it. The company didn't invent a problem and convince police to adopt it. It solved a genuine problem that police were already struggling with: identifying suspects and vehicles from surveillance footage takes time, and that delay costs cases.

When law enforcement can query a database and instantly find every vehicle in a specific area during a specific timeframe, that's powerful. When they can identify individuals from video, that's transformative. From a crime-solving perspective, these tools work. They solve cases. They do what police need them to do.

This is actually the harder part of the privacy debate. These aren't tools that are ineffective. They're not tools that police don't want. They're tools that police desperately want because they work. The question isn't whether the technology is effective. The question is at what cost to everyone else.

An integrated Ring-Flock system would have given police the ability to search across millions of residential cameras. That's not abstract surveillance. That's the ability to trace anyone's movements through a city by querying residential video footage. And the problem isn't that police would use it for bad purposes. The problem is that the capability exists and can be abused regardless of intent.

Historically, when new surveillance tools are deployed, they're deployed first for their legitimate uses and then gradually expanded beyond those uses. License plate readers were deployed to catch fugitives. They're now used to track political protesters. Facial recognition systems were deployed to identify dangerous criminals. They're now used to track people at protests and shopping centers. The tool doesn't change. The uses expand.

Law enforcement's interest in an integrated Ring-Flock system is rational from their perspective. But that rationality is precisely why privacy advocates worry about it. The system would work great for the stated purpose. And then it would probably be used for other purposes too.

The Role Of Political Leadership In The Backlash

Senator Ed Markey's intervention was crucial to this outcome, but it's worth understanding what made his intervention effective. Markey isn't new to technology oversight. He's been writing to tech companies about surveillance and privacy for years. Most of those letters probably don't get public attention.

But this letter landed differently because it aligned with something Americans were actively experiencing. Markey had been warning about Ring's surveillance risks for months. Ring ignored him. Then the company aired a Super Bowl ad showing those exact risks. Suddenly, Markey's technical warnings had visual evidence supporting them.

When a politician says "this is surveillance" and the company's own advertisement proves him right, that's when political pressure actually works. The Super Bowl ad gave Markey's concerns credibility with the general public. His letter then validated what the public was already feeling.

What's interesting is that Markey's letter specifically called out the dystopian nature of the ad, not just the privacy risks. He was engaging with Ring's own framing. The company had created an emotional narrative about protecting families and finding lost pets. Markey said: no, this is actually about mass surveillance, and it reveals everything about why that's dangerous.

This kind of political intervention is rare. Most surveillance technology quietly expands. Most regulatory questions get asked behind closed doors. But the combination of a public relations disaster and a senator willing to call out what he was seeing created political pressure that Amazon couldn't ignore.

It's worth noting that this didn't result in legislation. There's no new law limiting facial recognition in residential cameras. Congress didn't pass regulations on biometric data retention. What happened was corporate backpedaling. Ring canceled one partnership. That's effective in the moment but not transformative long-term.

What would actually solve this problem is regulation. Comprehensive legislation that limits how long companies can retain biometric data, that requires affirmative consent before collection, that limits integration with law enforcement systems, that provides transparency about what data is being collected and how it's being used. But legislation is slow. It requires sustained political will. The Ring controversy generated a moment of political attention that's now fading.

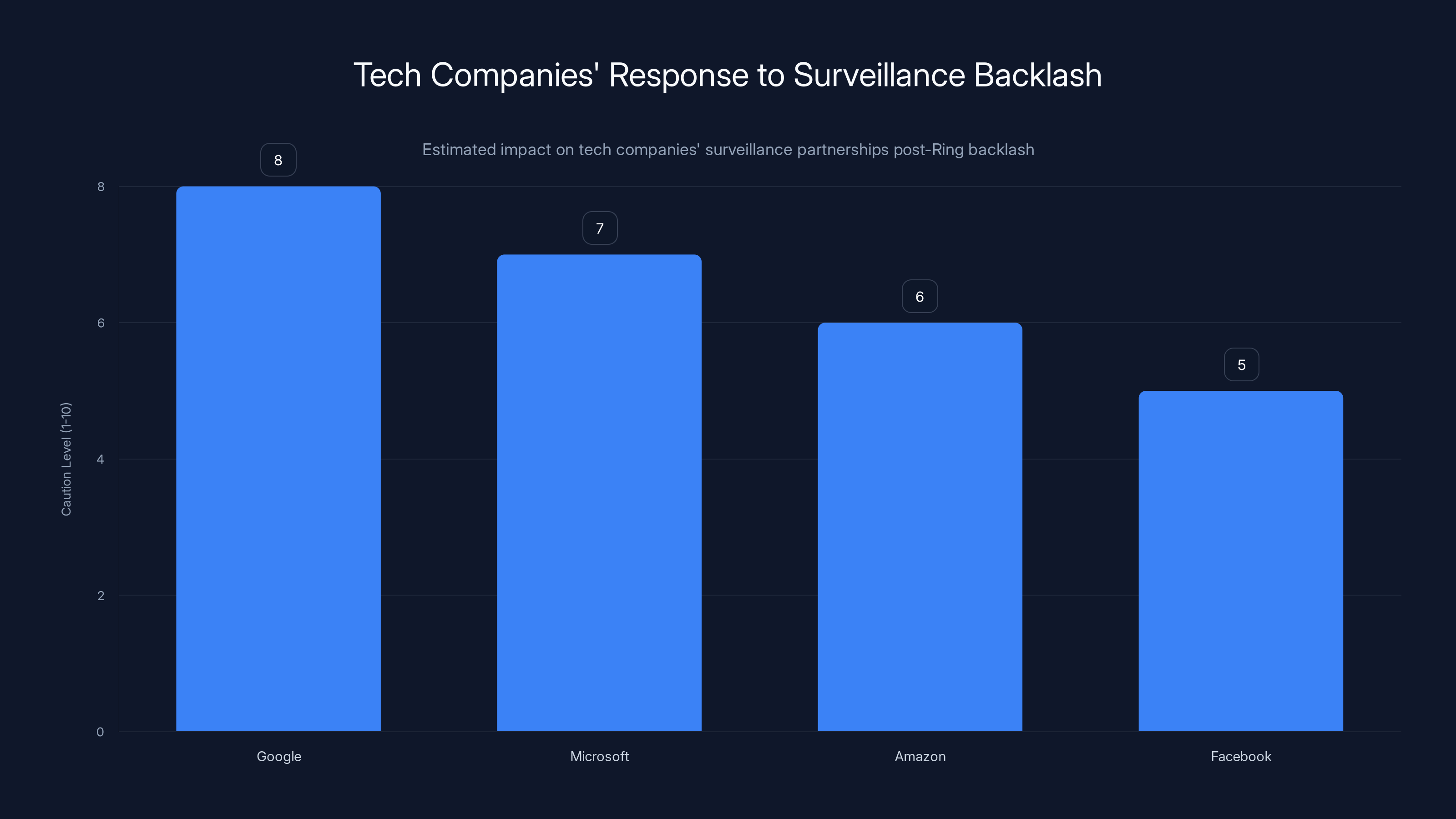

Estimated data shows that major tech companies increased caution in surveillance partnerships after Ring's backlash, with Google and Microsoft being the most cautious.

How Residential Surveillance Networks Are Reshaping American Neighborhoods

Ring's camera network isn't the only residential surveillance infrastructure being deployed. Companies like Wyze, Google Nest, and others are installing cameras in neighborhoods across America. But Ring is by far the most connected to law enforcement. Ring provides video footage to police thousands of times per month.

What this creates is a de facto surveillance network that wasn't explicitly designed or governed. It's the aggregate result of millions of individual consumer decisions to install cameras on their own property. But that aggregation creates something qualitatively different from individual camera installations. When there are enough cameras across enough neighborhoods, the infrastructure becomes something that can be queried, searched, and analyzed as a unified system.

This is particularly concerning in low-income neighborhoods where Ring has aggressively marketed through police partnerships. Ring provides cameras to police departments at discounted rates or covers the cost entirely. The company has worked with police to distribute cameras in specific neighborhoods. This isn't accidental. This is a deliberate strategy to build surveillance coverage in particular communities.

The civil liberties concerns around this are substantial. Surveillance infrastructure tends to be deployed inequitably. Wealthy neighborhoods might have cameras because residents choose to install them. Low-income neighborhoods have cameras because police encouraged installation. That creates a disparate impact on different communities.

Think about the pattern of surveillance that emerges: Ring cameras in low-income neighborhoods connected to Flock's law enforcement database, which receives queries from police departments. That infrastructure doesn't exist equally across all neighborhoods. It's concentrated where police departments prioritize enforcement. That concentration creates communities that are monitored more intensively than others.

This isn't necessarily conscious discrimination in the moment. But the pattern that emerges is discriminatory in effect. People in certain neighborhoods are surveilled more. Their movements are tracked. Their interactions are recorded. This is the kind of infrastructure that enables discriminatory policing.

What the Ring-Flock partnership would have done is accelerate and formalize this process. Instead of ad-hoc police requests for Ring footage, there would be an integrated system allowing searchable queries. That would make the infrastructure more powerful and more capable of supporting discriminatory enforcement.

The cancellation of the partnership doesn't change the underlying infrastructure. Ring cameras are still in neighborhoods. Police are still requesting footage. Biometric data is still being collected and retained. What changed is one specific integration that would have made the system too visible and too powerful to ignore.

Consumer Privacy Activism And Its Limits

What happened with Ring is a genuinely significant example of consumer backlash against surveillance technology. Millions of people saw the threat and said no. That's powerful. It's also rare. Usually, surveillance technology expands quietly.

But it's important to understand the limits of this kind of activism. Consumer backlash works best when it's: visible (everyone can see the product), emotional (it connects to how people actually feel), and easy to join (you don't need to be an expert to understand the problem). The Ring ad met all three criteria.

Most surveillance technology expansion doesn't meet those criteria. Most people don't see the cameras in their neighborhoods. Most data collection happens in the background. Most corporate partnerships happen quietly. When surveillance expands silently, consumer backlash is harder to organize.

What's also worth noting is what consumer backlash actually accomplished here. Ring is still selling cameras. Ring is still collecting biometric data. Ring is still retaining facial scans indefinitely. Ring is still deploying facial recognition features. None of those practices changed. The only thing that changed is one specific partnership.

Consumer backlash against a specific product is different from systemic change in how the technology is used. Destroying Ring cameras and requesting refunds is cathartic. It feels like victory. But if people are just switching to Google Nest cameras or Wyze cameras, the underlying surveillance infrastructure still exists. The problem hasn't been solved. It's been moved to a different company.

What would actually solve the problem is regulation. Laws that limit how long companies can retain biometric data. Requirements for affirmative consent before collection. Restrictions on integration with law enforcement. But those require legislative action, not consumer backlash.

Consumer activism has value in that it creates awareness. It puts pressure on companies. It establishes that some surveillance practices are unacceptable to significant segments of the population. But activism alone doesn't change the fundamental business model. It doesn't change the fact that surveillance is profitable. It doesn't change the fact that police want these tools. It doesn't change the fact that companies will keep trying to deploy similar systems, just with less obvious marketing.

Estimated data shows a significant portion of the public actively rejected Ring's surveillance technology after the Super Bowl ad, highlighting privacy concerns.

What Happened With Other Tech Companies' Surveillance Partnerships

Ring's cancellation of the Flock partnership had ripple effects across the tech industry. Other companies that were quietly exploring similar integrations suddenly became more cautious. Companies that had been planning announcements delayed them. The visibility of the Ring backlash created a collective pause.

Google, which owns both YouTube and has invested in various surveillance technologies, reportedly slowed its own plans for deeper law enforcement integration. Microsoft, which has faced its own criticisms about facial recognition deployments, reiterated its commitments to responsible use. The message was clear: if you announce partnerships like this publicly, you'll face the same backlash Ring did.

But here's the thing: the pause isn't permanent. The corporate desire to integrate with law enforcement systems hasn't changed. The business incentives pushing toward deeper partnerships haven't changed. What changed is the calculation about visibility and public relations.

Companies learned from Ring's mistake: don't announce these partnerships in a Super Bowl commercial. Don't make the surveillance infrastructure visible. Do it quietly. Do it through private partnerships with police departments. Do it through technical integrations that average consumers never learn about. Do it in ways that don't create viral backlash.

This is actually more dangerous than an openly discussed partnership would be. At least with Ring and Flock, the public could see what was being proposed and could mobilize against it. If similar integrations happen quietly, without public visibility, there's no opportunity for backlash.

Some of the surveillance technology integration that police wanted from the Ring-Flock partnership is probably happening anyway, just through different mechanisms. Different companies. Different integrations. Less publicity. Less opposition.

What we're likely to see in the next few years is more sophisticated privacy-conscious marketing from surveillance technology companies. They'll talk about protecting civil liberties while continuing to deploy surveillance infrastructure. They'll discuss safeguards while building systems without substantive limitations. They'll claim to prioritize privacy while quietly making deals with law enforcement.

The Ring episode is valuable precisely because it made the contradiction visible. It showed what surveillance infrastructure actually looks like when it's visualized honestly. And that visibility, temporarily, created resistance.

The Future Of Surveillance Technology And Privacy Rights

Where does this go from here? Surveillance technology is still advancing. Facial recognition is still becoming more accurate. Integration between different surveillance systems is still happening. The business incentives driving surveillance expansion haven't changed.

What has changed is public awareness. The Ring ad made millions of people think about surveillance in their neighborhoods. It made them consider what they're agreeing to when they install a camera. It made them question whether convenience is worth the privacy cost. That awareness won't last forever, but it's there now.

The real question is whether that awareness will lead to meaningful change. Meaningful change would look like:

Comprehensive facial recognition regulation limiting what companies can do with biometric data. Laws requiring affirmative consent before any biometric collection. Restrictions on sharing biometric data with law enforcement except in specific, narrow circumstances. Transparency requirements so people know when their biometric data is being collected and retained. Meaningful deletion rights so people can have their data removed.

None of that exists federally in the United States. Most of it doesn't exist at the state level either. And without it, surveillance expansion will continue, just with better public relations.

Ring's cancellation of the Flock partnership is a victory, but it's a limited one. It's the equivalent of stopping one pipeline while the broader infrastructure continues expanding. It matters for the moment. But it doesn't change the trajectory.

What would actually change the trajectory is seeing this kind of backlash repeated for other surveillance partnerships. Seeing it become politically costly for companies to announce surveillance integrations. Seeing elected officials consistently prioritize privacy rights over convenience. Seeing regulation passed that actually limits what companies can do with surveillance data.

That doesn't seem likely in the near term. But Ring's mistake—making the surveillance infrastructure so visible that millions of people had to confront what it actually was—shows that it's possible. It shows that public awareness can create resistance. It shows that surveillance isn't inevitable.

Key Takeaways And What You Should Know

The Ring-Flock situation crystallized several important truths about surveillance technology in America:

First, surveillance infrastructure is expanding faster than public awareness. Most people don't understand what Ring cameras do or what data is being collected about them. Until something makes the infrastructure visible, expansion continues quietly.

Second, when surveillance gets visible, people reject it. The Ring ad showed the infrastructure honestly and people said no. That's not a given. Most surveillance technology continues because most people don't see it. Visibility creates resistance.

Third, corporate privacy claims are often inadequate. Ring talks about "standards for customer trust, safety, and privacy" while collecting biometric data indefinitely without consent. The language sounds protective while the practices remain invasive.

Fourth, regulatory gaps enable surveillance expansion. Without federal privacy law, without restrictions on facial recognition, without limits on data sharing with law enforcement, surveillance companies can operate with minimal constraints. Corporate backpedaling in response to PR crises isn't a substitute for actual legal limits.

Fifth, consumer activism has power in specific contexts but can't solve surveillance problems at scale. Destroying Ring cameras feels like resistance but doesn't change the fundamental business model. Meaningful solutions require regulation, not just consumer choice.

Sixth, surveillance infrastructure concentrates power in ways that enable abuse. Even if Ring and Flock are using their systems responsibly today, the existence of the infrastructure enables future abuse. And history shows that surveillance capabilities are almost always eventually used in ways their creators didn't intend.

The Ring cancellation matters because it shows that public pressure can change corporate decisions. It matters because it revealed infrastructure that usually stays hidden. It matters because it gave millions of people a moment to think about what they're actually agreeing to when they install surveillance cameras in their neighborhoods.

But it doesn't solve the underlying problem. It doesn't create privacy protections. It doesn't limit surveillance expansion. It doesn't stop the next company from trying something similar, just with better marketing.

What we learned from Ring is that surveillance technology will continue expanding until something stops it. That something probably isn't consumer choice. It probably isn't corporate ethics. It probably is regulation, but only if people stay aware that the infrastructure exists and continue demanding that their elected officials actually protect privacy rights instead of just talking about them.

FAQ

What is the Ring and Flock Safety partnership?

The Ring-Flock partnership was a proposed integration between Amazon's Ring residential camera network and Flock Safety's law enforcement surveillance system. The partnership would have allowed police to instantly search across millions of residential Ring cameras to identify vehicles and individuals, creating an unprecedented infrastructure for coordinated surveillance across entire cities.

Why did Amazon cancel the Ring and Flock Safety partnership?

Amazon canceled the partnership following massive public backlash after airing a Super Bowl commercial that visualized the surveillance capability. The ad showed Ring cameras across an entire neighborhood instantly activating simultaneously. Senator Ed Markey and privacy advocates called out the technology as mass surveillance. Within two weeks, amid customer complaints, refund requests, and negative media coverage, Amazon and Flock jointly announced the partnership would not proceed.

What does Ring actually collect with its biometric data?

Ring cameras extract detailed biometric information including facial geometry, iris patterns, facial features, gait analysis, and behavioral patterns from anyone in their video range. This data is stored indefinitely unless the person requests deletion. The crucial issue is that this collection happens without the consent of people being filmed, only of the Ring camera owner.

How does Ring's Familiar Faces feature work?

Familiar Faces allows Ring owners to upload photos of people they want to recognize and automatically identify them when they appear on video. However, Ring's systems are also independently learning to identify everyone else who appears on camera. This creates a database of both familiar and unfamiliar people, which is particularly concerning when integrated with law enforcement systems.

What are the privacy concerns with residential surveillance networks?

Residential surveillance networks create infrastructure that can track individuals' movements through neighborhoods. When integrated with law enforcement databases, they enable police to instantly identify people's locations and movements. The technology enables discriminatory policing in low-income neighborhoods where Ring has prioritized deployment through police partnerships. The concern isn't just about current use but about the capability's potential for future abuse.

What would meaningful privacy protection against Ring look like?

Meaningful protection would require: federal legislation limiting biometric data retention periods, requirements for affirmative consent before any biometric collection, restrictions on sharing biometric data with law enforcement outside specific narrow circumstances, transparency requirements showing when data is collected and retained, and genuine deletion rights enabling people to have their data removed. Currently, none of these protections exist at the federal level, and most don't exist at state levels either.

Why is the Ring-Flock cancellation important but limited?

The cancellation is important because it shows public pressure can change corporate decisions and because it revealed surveillance infrastructure that usually stays hidden. It's limited because it only canceled one specific partnership. Ring continues collecting biometric data, retains facial scans indefinitely, and is deploying advanced facial recognition features. The underlying surveillance infrastructure remains in place, just without this specific law enforcement integration.

What happens next with surveillance technology regulation?

Without meaningful legislation, surveillance technology will continue expanding, likely more quietly after Ring's public relations lessons. Companies will pursue similar law enforcement integrations through less visible channels. Real change requires federal privacy legislation with specific restrictions on facial recognition, but such legislation faces significant corporate lobbying and remains unlikely in the near term without sustained political pressure.

The Ring-Flock situation reveals a crucial truth about surveillance infrastructure in America: it expands continuously in the background, mostly invisible to the people affected by it. The rare moments when it becomes visible—like Ring's Super Bowl ad—create opportunities for resistance. But temporary victories against specific partnerships don't address the systemic problem of unchecked surveillance expansion. Real protection requires regulation, sustained political will, and sustained public awareness that surveillance infrastructure is being built whether we're paying attention or not.

Related Articles

- Ring Cancels Flock Safety Partnership Amid Surveillance Backlash [2025]

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: The Privacy Reckoning [2025]

- CBP's Clearview AI Deal: What Facial Recognition at the Border Means [2025]

- Ring's Super Bowl Ad Backlash: The Surveillance Debate [2025]

- Ring's Police Partnership & Super Bowl Controversy Explained [2025]

- Social Security Data Handover to ICE: A Dangerous Precedent [2025]

![Ring Cancels Flock Deal After Super Bowl Ad Sparks Mass Privacy Outrage [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ring-cancels-flock-deal-after-super-bowl-ad-sparks-mass-priv/image-1-1771020363034.jpg)