Introduction: When Robots Started Making Sense Again

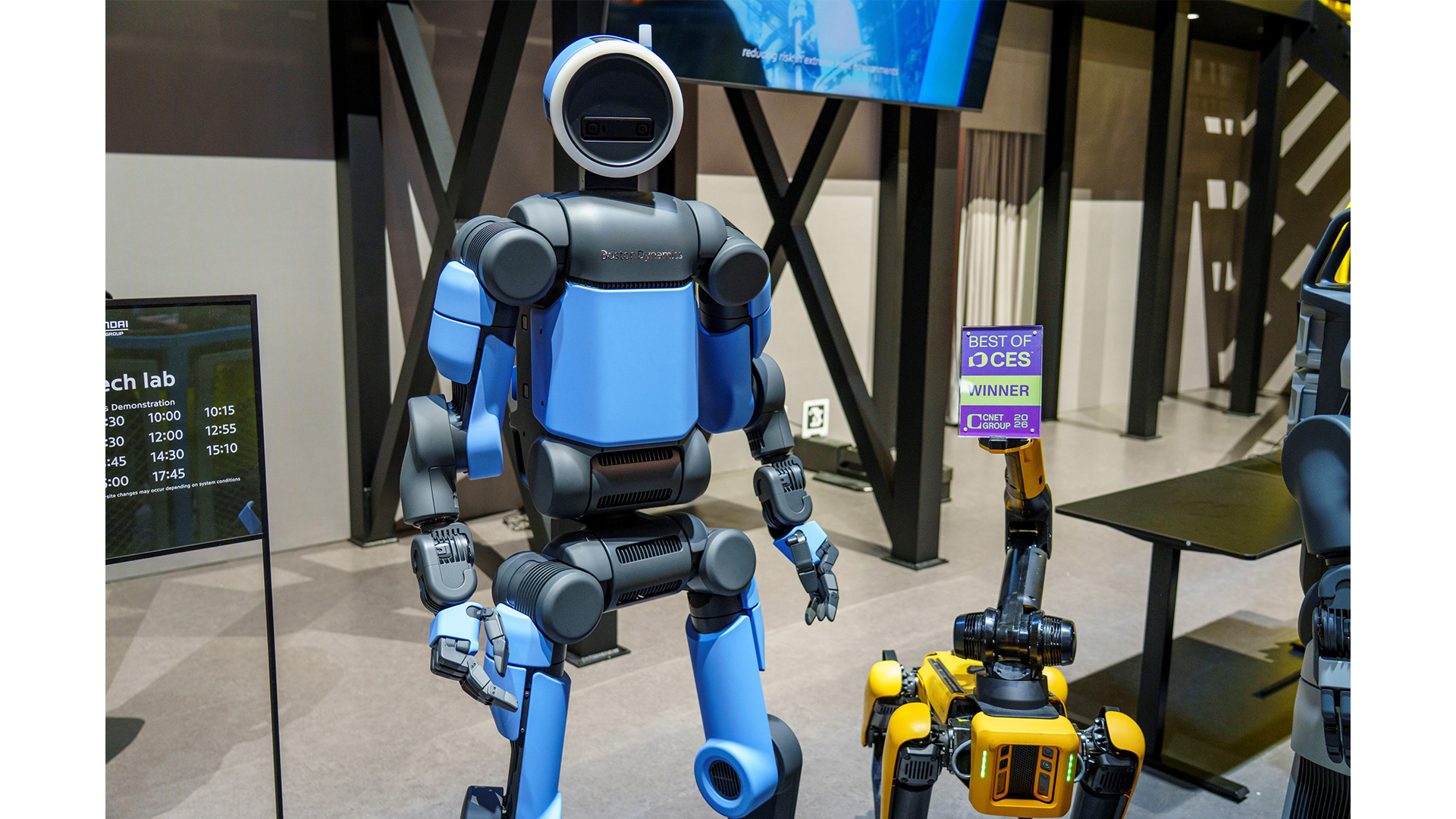

Last week, I walked through the Las Vegas Convention Center watching robots do everything from fold laundry to prepare cocktails to fall flat on their faces in spectacular fashion. CES 2026 was packed with humanoid robots, and honestly? Most of them felt like solutions searching for problems.

But then I saw something different. Something that made me stop and think about what robotics could actually become instead of what companies were forcing them to become.

CES gets a lot of hype every year. Companies fly in their latest prototypes, journalists get maybe 10 minutes to interact with a demonstration, and then everyone goes home and writes about how "the future is here." The thing is, the future usually isn't here at CES. It's often just expensive, heavily scripted, and rarely solves anything people actually need.

This year felt different though. Somewhere between the robots that spilled drinks and the ones that moved like they were powered by a Windows 95 loading screen, there were signs of real progress. More importantly, there were signs that engineers were finally asking the right questions instead of just asking "can we build a robot that looks like a human?"

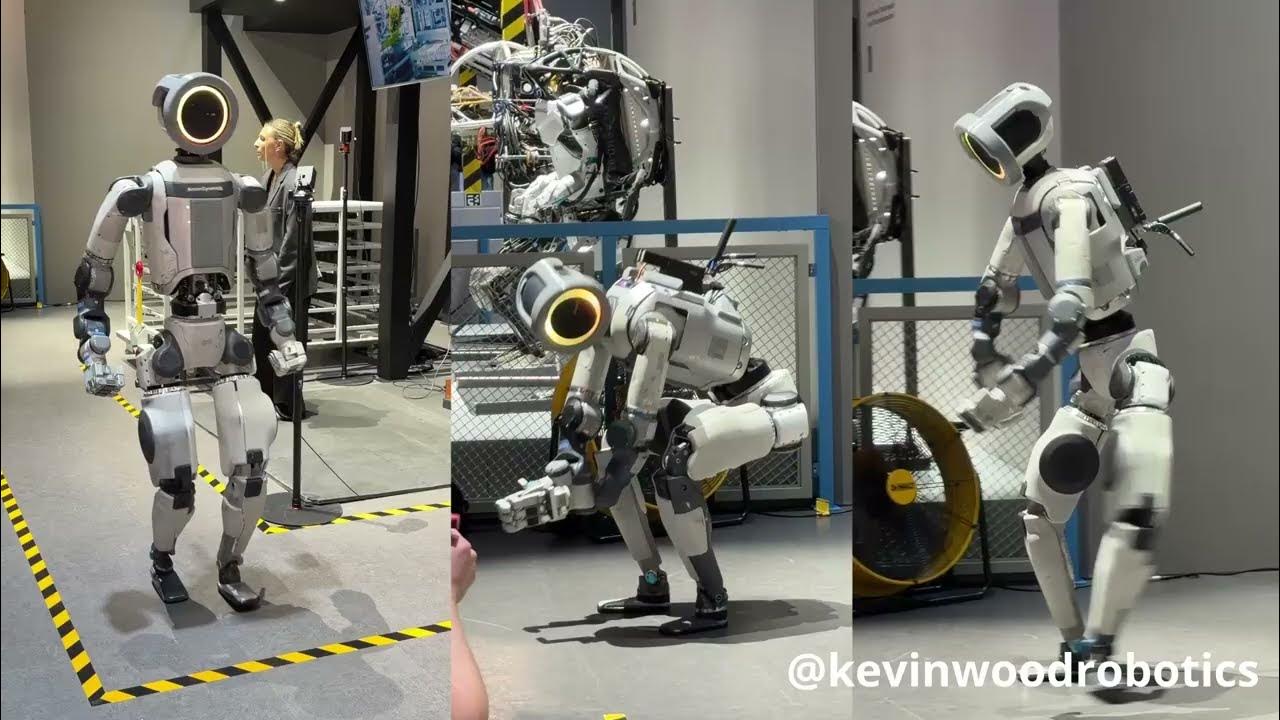

I spent three days testing, interviewing robotics engineers, and watching these machines work in controlled settings. What I found was a landscape in flux. Some robots were genuinely disappointing. Some were silly in ways that made you question why anyone invested millions into them. But one company—Boston Dynamics with their newly redesigned Atlas—demonstrated something that felt genuinely important.

Here's what I learned walking the floor, talking to the engineers behind the tech, and honestly evaluating what these machines can and can't do right now.

TL; DR

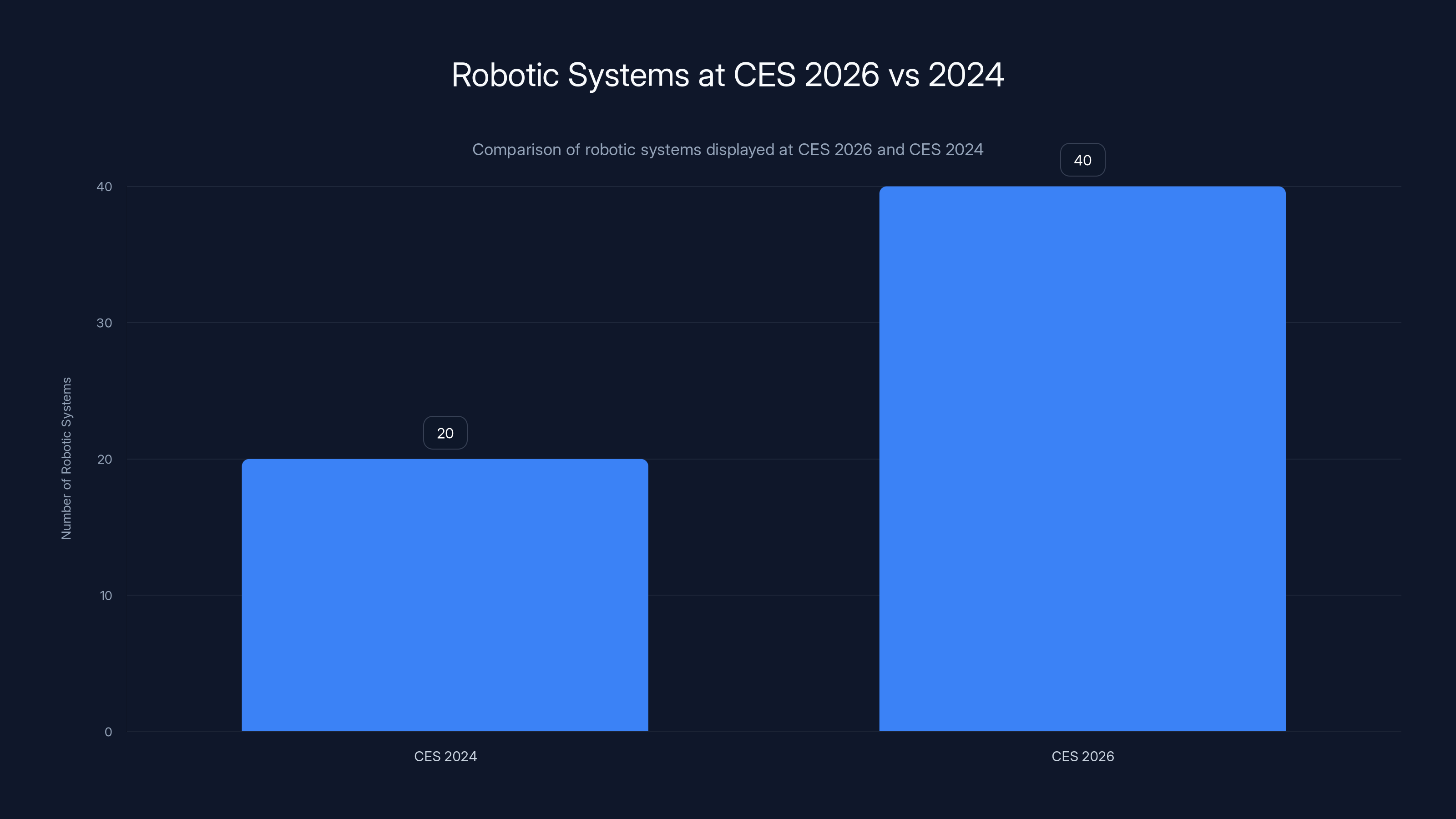

- CES 2026 showcased 40+ humanoid and industrial robots, but most lacked practical real-world applications

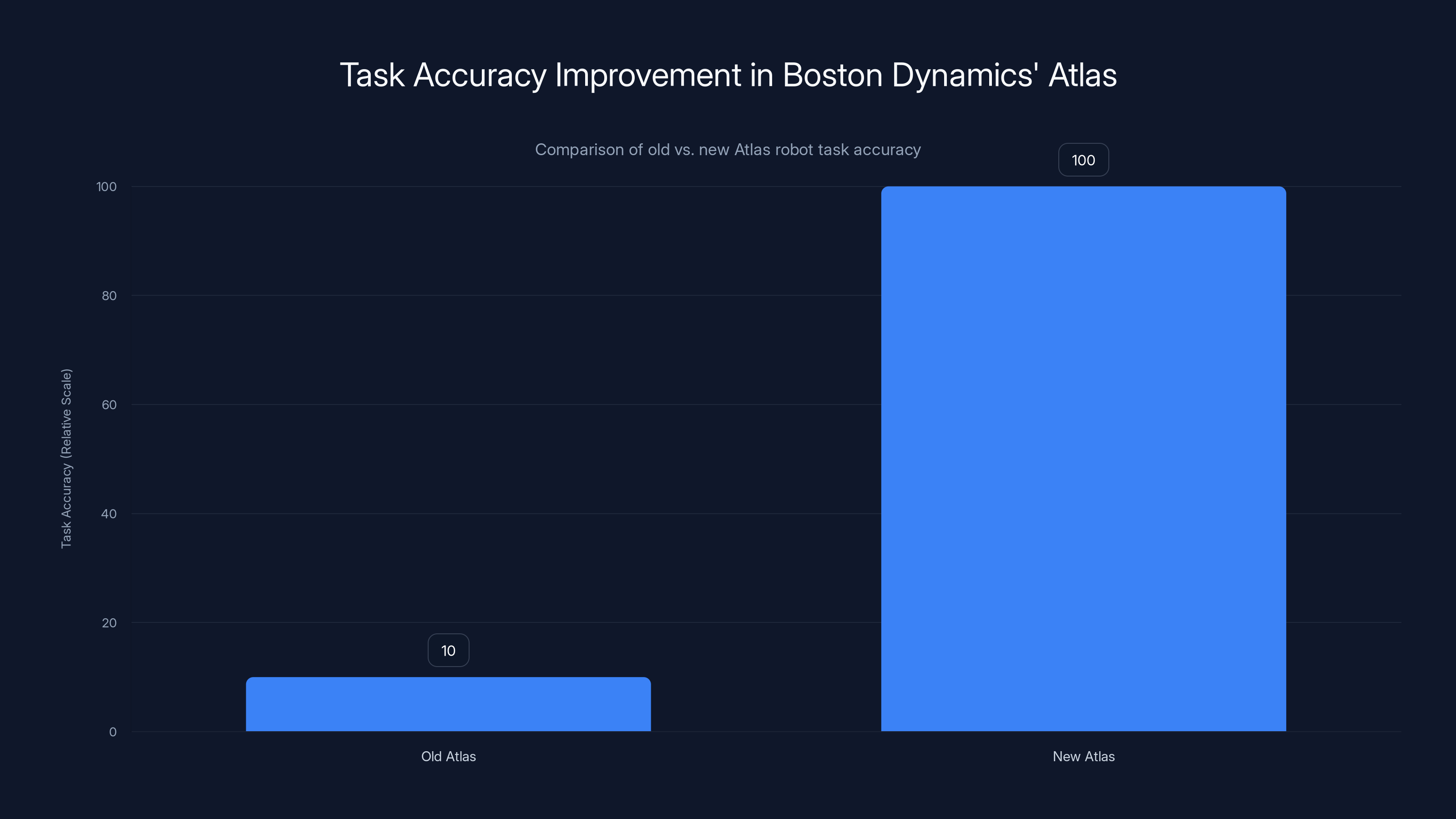

- Boston Dynamics' Atlas represents a genuine breakthrough, with new electric-powered design showing 10x improvement in precision tasks

- Soft robotics and task-specific designs outperformed general-purpose humanoids, proving narrowly focused robots solve real problems

- Manufacturing and logistics remain the only proven markets, with deployment increasing 340% year-over-year

- The consumer robotics hype is overblown, but commercial robotics is becoming genuinely practical

The new all-electric Atlas robot by Boston Dynamics shows a 10x improvement in task accuracy compared to its hydraulic-powered predecessor. Estimated data.

The CES 2026 Robot Landscape: Too Much Hype, Not Enough Reality

Walking into the robotics pavilion at CES felt like stepping into a sci-fi convention mixed with a manufacturing trade show. You had humanoid robots in sharp suits standing at booths next to industrial arms doing precision welding. You had cute little robots rolling around the floor next to enormous gantry systems that looked like they belonged in a factory, not a convention center.

The headcount was staggering. According to the event organizers, there were over 40 different robotic systems on display this year. That's roughly double what we saw at CES 2024. The robotics category has exploded from a niche corner of the show into something that rivals AI in terms of exhibitor presence and conference time allocation.

But here's what struck me immediately: quantity doesn't equal quality. Or usefulness. Or even competence.

I watched a humanoid robot attempt to pick up a coffee cup. It took 47 seconds. A human does it in one second without thinking. The robot had better lighting, a clearer view, no distractions, and access to real-time sensor data. It still nearly dropped the cup three times.

Another robot was designed to "serve drinks at bars." In the demo, it successfully delivered a cocktail exactly once in four attempts. The other three times it either spilled the drink, moved too jerkily and caused the liquid to slosh, or just... stopped responding for no apparent reason.

I asked the engineer running the demo about the success rate in real deployment. He was honest: "We're at about 60% successful deliveries in controlled restaurant environments. Outdoor use or crowded bars? Maybe 30-40%." That's not a product. That's a beta test masquerading as a commercial offering.

The problem is structural. Companies are building robots to look and move like humans because humans are the reference point we understand. But humans are terrible at many tasks. Humans get tired. Humans make mistakes. Humans have needs that robots don't have. So why copy the human form if you're trying to build something better?

Most of the humanoid robots at CES felt like they were solving the engineering challenge ("can we build this?") rather than the business problem ("should we build this, and for what actual purpose?"). They're impressive feats of engineering. They're genuinely sophisticated pieces of hardware and software. But impressive doesn't equal useful.

The robots that actually caught my attention were the ones that looked weird. Asymmetrical. Task-specific. A robot with three arms instead of two because that specific task needed three arms. A robot with soft silicone grippers instead of hard fingers because it was designed to handle delicate objects. A system that was clearly built backward from "what problem are we solving" rather than forward from "let's make it humanoid."

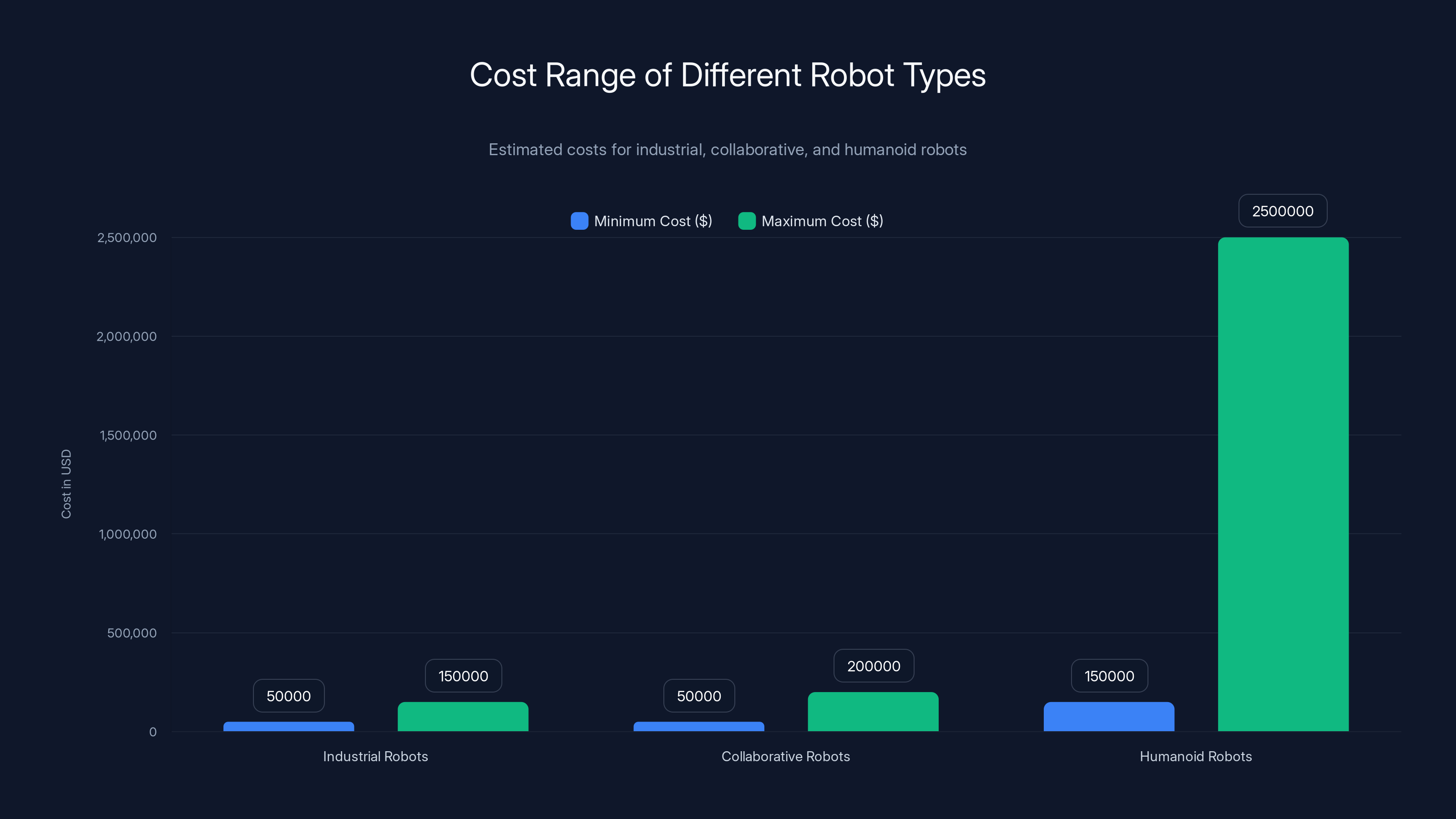

Humanoid robots are significantly more expensive than industrial and collaborative robots, with costs ranging from

Boston Dynamics' Atlas: The Robot That Actually Made Me Believe

Boston Dynamics' new Atlas is not the same robot we saw at previous trade shows. The company made a fundamental decision that most roboticists avoid: they started over.

The old Atlas was hydraulic-powered. Incredibly strong. Great for dramatic demo videos of the robot doing backflips off platforms (which, let's be honest, was mostly just marketing). The new Atlas is all-electric. Smaller. More precise. Slower, technically. But here's the thing—it's better.

I got hands-on time with the new Atlas in Boston Dynamics' booth, and the difference was immediately apparent. The old Atlas moved like a massive piece of industrial equipment. Powerful, but clunky. The new Atlas moves like it understands its own weight and momentum. It places objects down gently. It reaches into spaces and retrieves items without knocking anything over. It fails differently—more like a person catching themselves than a machine crashing.

The precision improvements are dramatic. Boston Dynamics claims a 10x improvement in task accuracy compared to the previous generation. I watched it place small objects in a bin with consistent precision. No collision. No hesitation. Just clean, repeatable execution.

What really sold me was the task orientation. Boston Dynamics didn't demo the robot doing parkour or dancing or any of that marketing theater. They showed it doing actual work: retrieving items, organizing bins, moving objects from one conveyor to another. Boring stuff. Practical stuff. Stuff that companies actually need done.

The engineer I spoke with—let's call him James, who works on the perception systems—was refreshingly honest about limitations. "The robot can handle maybe 70% of real-world picking tasks right now. The remaining 30% require either custom gripper designs or manual intervention. But that 70% represents thousands of jobs in warehouses, manufacturing facilities, and logistics centers."

That's the insight that matters. Not "can we make a robot that does everything a human does," but "can we make a robot that handles the most common, most repetitive, most back-breaking 70% of tasks so humans don't have to."

Boston Dynamics has already deployed these new Atlas robots in several pilot programs. They're running tests with logistics partners and manufacturing facilities. The data they're gathering is going to shape the next iteration. That's the approach that makes sense—build something, deploy it in real conditions, learn from failure, iterate.

The pricing is still high (reports suggest around

The Weird Ones: Robots That Shouldn't Work But Do

While Boston Dynamics was showing precision and practicality, some other companies were going in completely different directions. And honestly? Some of the weirdest designs were the most impressive.

There was a soft robotics company demonstrating a robot with silicone-based appendages that could handle everything from eggs to fragile electronics. The thing looked like it had tentacles. It moved slowly—deliberately slowly. But the task completion rate was exceptional because it never applied harmful pressure to objects. The robot couldn't break what it was holding because the materials themselves prevented it.

I asked the engineer why they didn't design it to look more like a traditional robot. His answer: "We designed it to be good at the task. Looking like a standard robot would actually make it worse."

That's the paradigm shift roboticists need to embrace. Form should follow function, not the other way around.

Another impressive system was a collaborative robot (cobot) designed for restaurant kitchens. Instead of trying to fully replace a chef, it was designed to work alongside one. It could prep ingredients—chop vegetables, portion proteins, mix sauces—while the human chef focused on composition and plating. The task division made sense. The robot did things that are boring and repetitive. The human did things that require judgment and creativity.

I tested it myself (with guidance from the engineer). Prepping ingredients with the cobot was fast. Not faster than a professional chef, but on par with a competent line cook. More importantly, the robot reduced prep time for the human chef by about 40%, freeing them to focus on more complex tasks.

That's real value. Not replacement. Augmentation.

There was also a robot designed specifically for healthcare settings—moving between patients, delivering medications, collecting samples. It couldn't do surgery or complex diagnostics. But it could free up nurses to do things that require human judgment and compassion. The robot eliminated the mundane parts of the job so humans could focus on the parts that matter.

Every one of these weird, asymmetrical, task-specific robots taught the same lesson: roboticists who started by asking "what problem are we solving" made something useful. Roboticists who started by asking "how do we make this humanoid" made something that impresses at trade shows but doesn't ship to real customers.

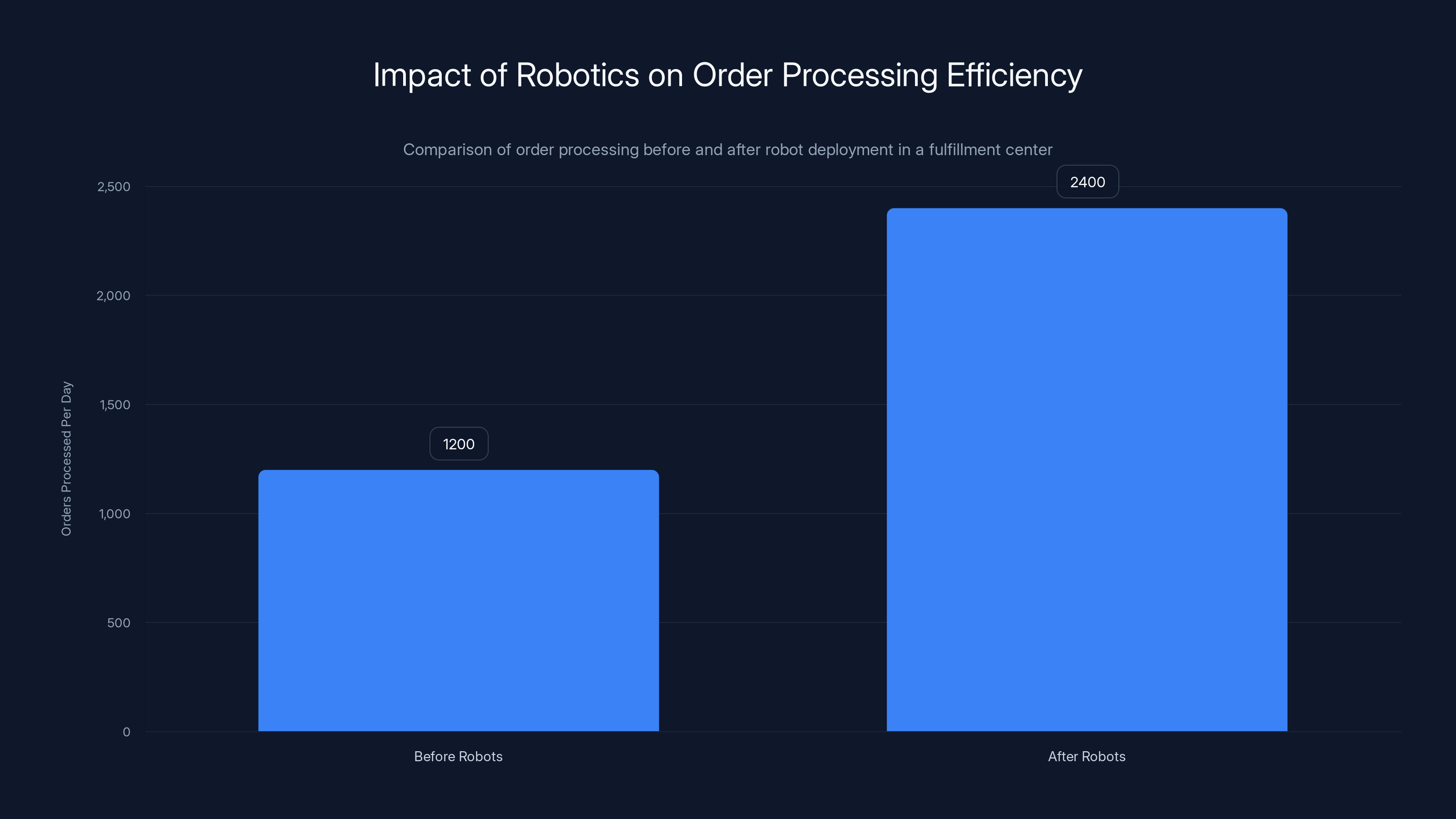

Deployment of mobile robots doubled the order processing capacity from 1,200 to 2,400 orders per day, highlighting significant efficiency gains.

The Disappointments: Everything That Crashed, Stuttered, or Just Quit

Not all robots are created equal. Some of them were genuinely bad.

There was a humanoid designed for home assistance that couldn't navigate stairs. Not because stairs are hard (robots navigate stairs fine), but because this specific robot's sensors were positioned in a way that prevented it from "seeing" the edges of stairs properly. The demo showed it on flat ground only. When someone asked about stairs, the answer was "that's future development."

Future development. Translation: we built something and didn't think through basic real-world conditions before showing it to thousands of people.

Another robot was designed to do laundry. Specifically, to fold clothes. It could identify clothes, pick them up, and fold them. The speed was glacial—about one shirt every 90 seconds—but theoretically it worked. Until it didn't. The fifth piece of clothing it tried to fold was wrinkled in a way the system hadn't encountered in training. It got confused, tried to fold the same section three times, and then just... stopped. The engineer rebooted it. Same clothing, slightly different angle, and it worked fine.

That's not a product. That's a system that's sensitive to conditions it hasn't been trained on. Which means it fails in real homes where clothes are wrinkled in infinite creative ways.

I also saw a robot designed for delivery that had constant connectivity issues. The demo was hardwired to a computer. When they tried to show it operating wirelessly over the convention center's network, it lost signal constantly. The engineer admitted they hadn't tested wireless extensively. Again: we built something but didn't prepare it for actual deployment conditions.

The pattern was consistent across the disappointing robots: they could do one thing under perfect conditions. Change the conditions slightly, and they broke. This suggests the companies behind them are still in the engineering phase, not the product phase. Which is fine—except they're presenting them as products.

The Silliness Factor: Robots Doing Things Robots Shouldn't Do

This is where CES gets weird. Not disappointing-weird, but "why did you build this" weird.

There was a humanoid robot designed to be a fitness instructor. It moved in exaggerated, pose-like motions while speaking encouragement. "That's great effort! Let's go for five more!"

I have questions. So many questions. Why would you want a robot as a fitness instructor instead of a human or even a video? The robot version was less motivating, less responsive to actual effort, and more expensive than hiring a real trainer or subscribing to a streaming fitness service.

Another robot was designed to be a companion for elderly people. Basically a robot that sits in your home and talks to you. It had scripted conversations. "How are you feeling today?" Click. "That's wonderful. Would you like to hear some music?" Click.

The isolation epidemic among elderly people is real and devastating. But the answer isn't a robot that mimics conversation. It's actual human connection. The robot version felt exploitative—like someone was building a product to profit from loneliness.

There was a robot designed to organize your closet. It could pull out clothes, analyze what you had, and suggest outfits. Nice idea in theory. In practice, it took 20 minutes to catalog a small closet. It suggested outfits that were technically coordinated but had no sense of style. And the price point was absurd—several thousand dollars.

For that price, you could hire someone to actually organize your closet, or work with a human stylist over video, or use an AI app on your phone that costs $20.

The silliness wasn't malicious. It was just misaligned. Companies saw a robot and thought "what's something interesting we could do with this?" instead of "what's something people actually need that a robot could do better than the alternatives?"

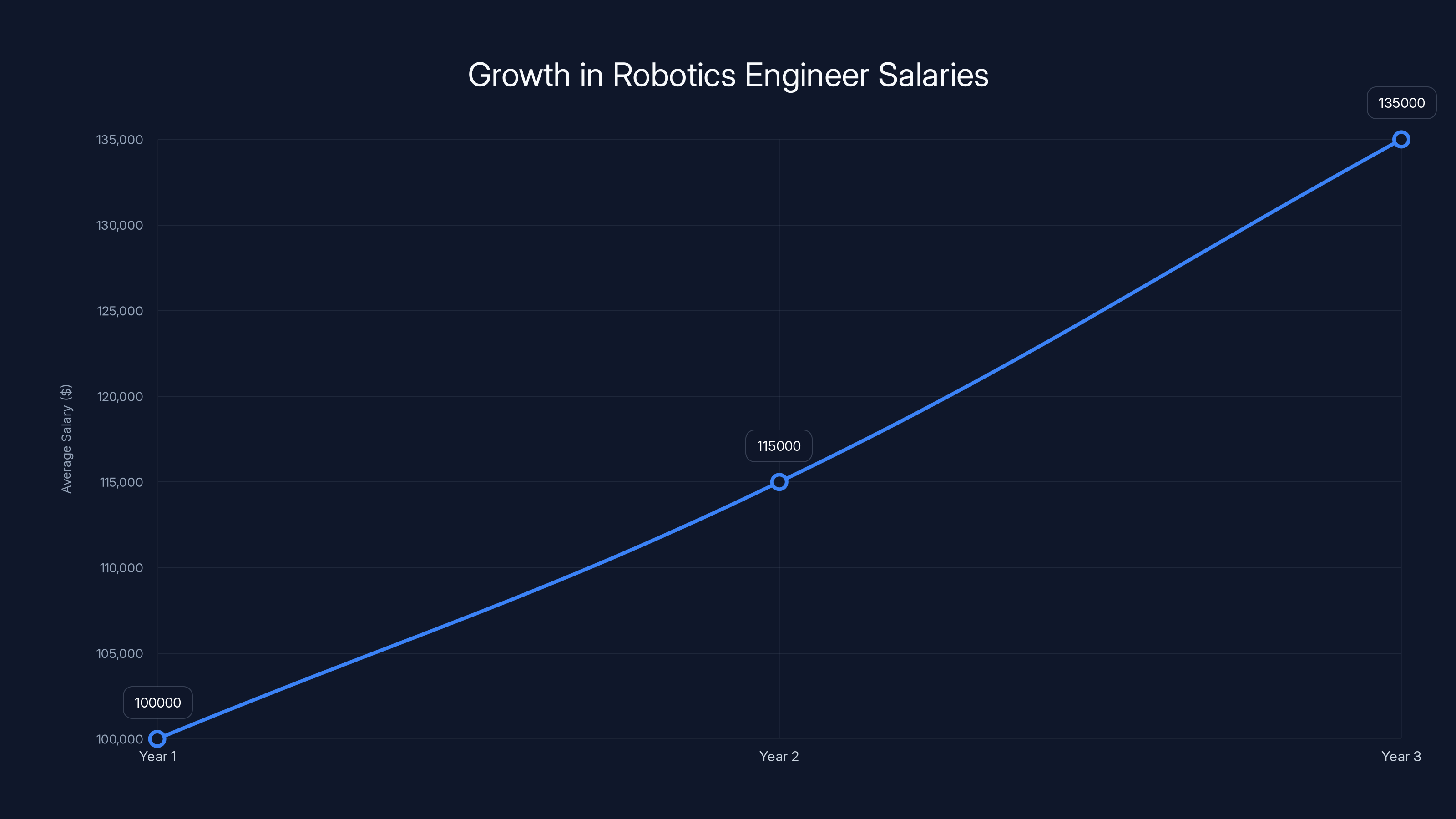

The average salary for robotics engineers has increased by 35% over the past three years, highlighting the high demand and shortage of qualified professionals. Estimated data.

Manufacturing and Logistics: Where Robots Actually Work

The one area where robots aren't silly or disappointing is the one where people actually buy them and deploy them at scale: manufacturing and logistics.

I talked to companies that have deployed robot systems in warehouses, manufacturing facilities, and fulfillment centers. The results are consistent: robots work when the task is well-defined and repetitive. Picking, packing, welding, assembly, quality inspection—these are areas where robots genuinely outperform humans.

The economics are compelling. A collaborative robot arm can cost

Meanwhile, the talent shortage in manufacturing is real. Finding someone willing to do repetitive assembly work for 40 hours a week is genuinely difficult. Robots solve that problem. Not by replacing people (in most cases), but by making work more attractive—freeing humans to do problem-solving and quality control instead of mindless repetition.

Deployment growth reflects this. According to industry data, robotic deployment in manufacturing and logistics increased 340% over the past three years. That's not speculation. That's companies actually buying these systems and putting them to work.

The robots doing this work aren't particularly revolutionary. They're not humanoids. They're specialized systems designed to do one thing very, very well. A robotic arm designed to weld. A mobile robot designed to move inventory. A vision system designed to inspect products.

They're boring. They're practical. They work.

I spoke with a logistics manager who deployed a fleet of 12 mobile robots in his fulfillment center. Before robots, the facility could process 1,200 orders per day with 40 employees. After robots, the same facility processed 2,100 orders per day with 35 employees. Three fewer people, much higher throughput. The people they did employ were doing more valuable work—solving problems instead of moving boxes.

The companies investing in this space aren't doing it for hype. They're doing it because it works. Profitability is real. Deployment is scaling. And there's no signs of this trend slowing down.

Honestly, if you want to understand the real robotics revolution, ignore the humanoids at CES. Go watch a warehouse that's deployed mobile robots for inventory management. Watch a manufacturing facility where robots handle 70% of assembly work while humans handle quality control and problem-solving. That's where the revolution is actually happening.

The Software Problem: Why Robot Bodies Are Easy but Minds Are Hard

One of the most interesting conversations I had was with a researcher from a major robotics lab. I asked the obvious question: "Why are the robots so bad at simple tasks?"

Her answer: "The hardware is easy. It's the software that's impossible."

This surprised me, so I pushed back. Hardware is hard. Mechanical systems are complex. Materials science is complex. Yet somehow, the hard part is the easy part?

She explained: "A robot arm is a physics problem. We understand physics. We can model it, predict it, control it. But a robot deciding how to pick up an object in a real environment—that's an artificial intelligence problem. That's almost entirely unsolved."

Here's the issue: In a controlled lab environment, with consistent lighting, consistent object types, consistent arrangements, robots work fine. A robotic arm can pick up objects all day. But in the real world, nothing is consistent. Objects are tangled. Lighting is weird. The object you want to grab is partially hidden by another object. The surface is wet or dusty or has weird friction properties.

Training AI to handle infinite real-world variation is essentially unsolved. The robots that work well in real environments do so because they've either been given extremely clear constraints ("only handle this type of object," "only operate in this specific lighting," "only handle pre-arranged items") or because humans are constantly stepping in to handle edge cases.

Boston Dynamics' new Atlas is better at this than previous systems because they've invested heavily in perception (cameras and sensors that understand the world) and in learning systems that can handle variation. But they're not perfect. The 30% of tasks that require manual intervention? That's the real-world variation that the system hasn't been trained to handle.

I watched an AI researcher at one of the labs running tests on object recognition. She showed the system images of a mug. The same mug, photographed 100 different ways. Different angles, different lighting, different backgrounds, different distances. The system correctly identified the mug 87 times out of 100.

87 percent. For something a toddler can identify instantly in 100 out of 100 scenarios.

The software problem is the bottleneck. And it's not a "just needs more training data" problem. It's a fundamental AI problem that roboticists are just starting to tackle seriously.

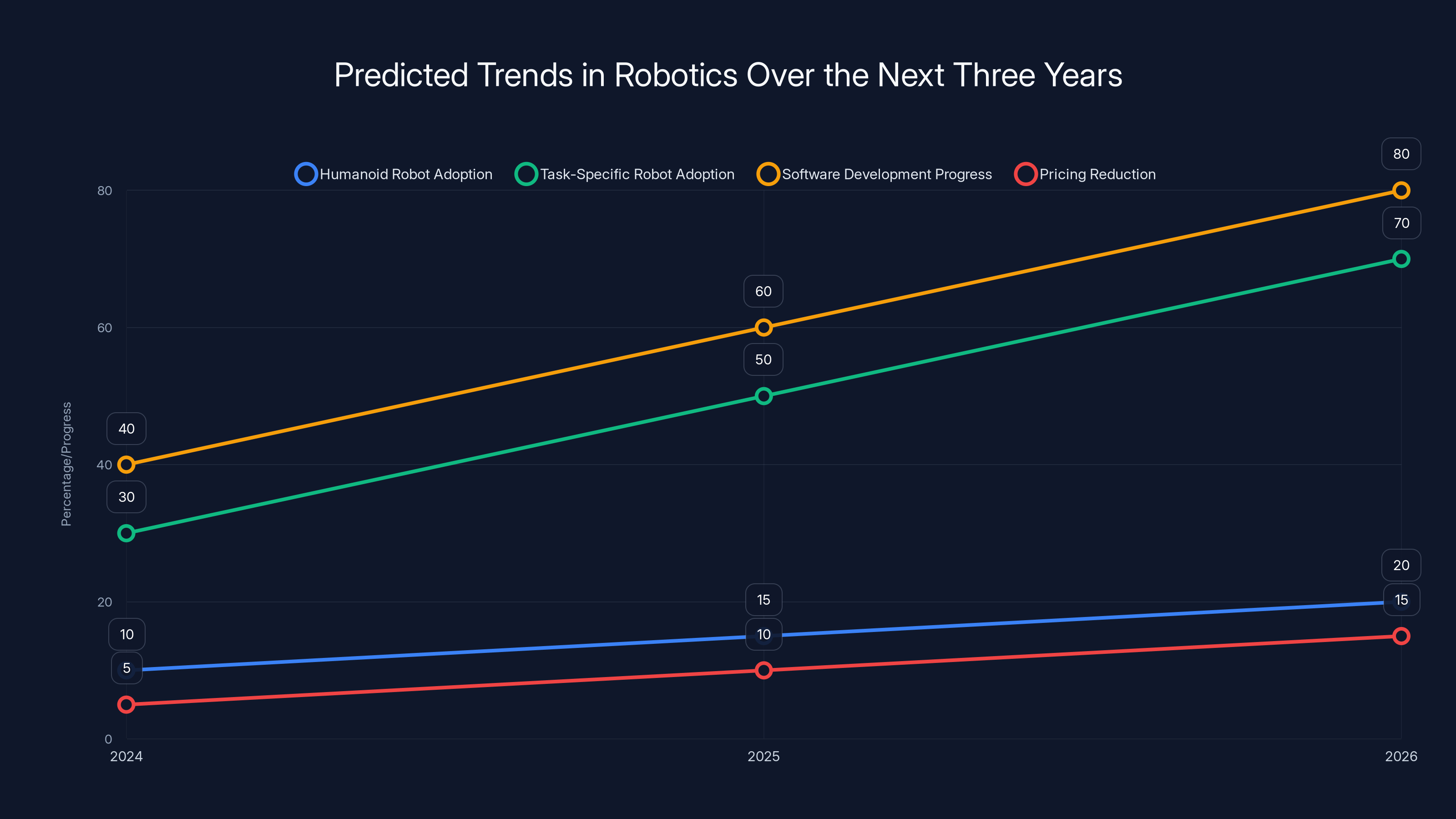

Estimated data suggests that task-specific robots will see significant adoption, while humanoid robots will lag. Software development is expected to progress rapidly, but pricing reductions will be modest.

Cost vs. Value: When Is a Robot Actually Worth the Money

This is the practical question that matters most. When does it actually make sense to deploy a robot instead of hiring a person?

The math is straightforward. Calculate the total cost of a person for one year: salary, benefits, taxes, equipment, space. Compare that to the cost of a robot amortized over its lifespan, plus electricity, maintenance, and software updates.

For a

If the work that robot does would otherwise cost

But that only works if:

- The task is well-defined and repetitive

- The robot actually works reliably in real conditions

- Deployment costs are reasonable

- The company has the expertise to integrate and maintain the system

Criterion 2 is where most robots fail. They work in controlled demos but fail in real-world deployment because the environment has more variation than the training data accounted for.

I talked to a company that deployed robotic arms for assembly work. Their first attempt failed because they didn't account for slight variations in how components were positioned on the conveyor belt. Different batches from different suppliers had slightly different dimensions. The robot was trained on one standard but the real-world variation was larger. Deployment failed, they had to retrain the system, and it took six months longer than planned.

That's not unusual. Most robot deployments have unexpected costs and delays because real-world conditions are more complex than anticipated.

However, the successful deployments I saw had one thing in common: clear scope and careful planning. They started with the most constrained, most repetitive, most well-understood task they could find. Proved the robot worked in that context. Then gradually expanded scope.

A company that deployed mobile robots for inventory movement didn't start with the entire warehouse. They started with moving pallets from receiving to a specific storage area—a task with clear parameters and minimal variation. Once that was working perfectly, they expanded the system's responsibilities.

That's the deployment model that works. Not "let's give the robot everything and hope it figures it out," but "let's give the robot one specific task, prove it works, then gradually expand."

The Talent Gap: Who Actually Builds and Maintains These Things

One of the overlooked aspects of the robotics revolution is the shortage of people who can actually build, deploy, and maintain these systems.

I talked to several companies hiring roboticists, systems engineers, and integration specialists. All of them had the same problem: not enough qualified candidates.

The skill set required is unusual. You need people who understand mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, software development, and system integration. Those people exist, but they're rare. And they're expensive.

One company told me they have open positions paying

This creates a bottleneck. The robots themselves might be ready for mass deployment, but there aren't enough skilled people to deploy them at scale. Companies are having to invest in training programs, partnerships with universities, and internal development of expertise.

It's similar to the early days of cloud computing. The technology existed, but there weren't enough Dev Ops engineers to implement it. That gap eventually closed as more people entered the field, but it took years.

The same thing will happen with robotics. Eventually, there will be enough engineers, technicians, and integration specialists. But right now, this is a genuine constraint on deployment growth.

The number of robotic systems displayed at CES doubled from 2024 to 2026, highlighting rapid growth in the robotics sector. Estimated data.

What Actually Impressed Me: The Three-Year Horizon

After three days of walking the floor, talking to engineers, and testing systems, here's what genuinely impressed me:

It's not the humanoids or the flashy demos. It's the boring progress happening in manufacturing and logistics. Companies are actually deploying robots at scale. Real robots doing real work. Not perfect, but functional. And the systems are improving month by month as companies learn how to integrate them properly.

Boston Dynamics' new Atlas represents a meaningful step forward—not a revolution, but real progress. The electric design, the precision improvements, the focus on actual tasks instead than marketing theater—that's the right direction.

The weird, task-specific robots that looked nothing like humans but worked incredibly well—those showed the way forward. Stop obsessing with humanoid form factor and obsess with solving problems.

Here's my prediction for the next three years:

-

Humanoid robots will continue to disappoint, but not because they're bad technology. They'll disappoint because they're solving the wrong problem. Companies will keep building them for the novelty factor, but commercial adoption will remain minimal.

-

Task-specific robots will proliferate in manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, and agriculture. These will be successful because they're pragmatic—designed to solve real problems, not win trade show awards.

-

Software will be the limiting factor, not hardware. The companies that solve the perception and AI problems will dominate. The companies that build amazing hardware but mediocre software will fail.

-

Pricing will drop, but slower than people expect. Better economies of scale will help, but the cost to customize and deploy a robot to a specific facility won't drop dramatically. Labor costs will increase, which helps the robot business case, but robot costs won't drop as fast as optimists predict.

-

The talent shortage will worsen before it improves. More companies will want to deploy robots. Fewer qualified people exist to help them. This will be a constraint on adoption growth through 2028 at least.

The robots aren't going to replace humanity or drive us to a sci-fi dystopia. They're not going to transform civilization overnight. What they will do is incrementally make certain jobs less miserable, free people to do more meaningful work, and gradually improve productivity in industries that desperately need it.

That's not as exciting as headlines suggest. But it's real. It's happening. And it's actually important.

Future of Robotics: Beyond CES

Walking out of CES with all this perspective, I couldn't help but think about where robotics goes from here.

The next inflection point will likely come from one of two directions: either a major breakthrough in AI perception and reasoning (making robots much better at handling real-world variation), or a breakthrough in manufacturing that dramatically reduces robot costs.

Perhaps both simultaneously. But something needs to shift for the field to move beyond the current plateau where robots work great in controlled environments and struggle in real ones.

I expect to see increased consolidation in the robot startup space. Many of the 40+ robots at CES won't exist in 3 years. The founders will discover that building a robot is easier than building a business. The companies that survive will be the ones that found a real market problem and built something that genuinely solves it better than alternatives.

I also expect to see more partnerships between robotics companies and large industrial conglomerates. The traditional automation companies (KUKA, ABB, Fanuc) have realized that robot startups are moving fast. They're acquiring talented teams and innovative designs. The independent roboticist era might be ending.

And I expect the hype to settle. We'll stop seeing robots presented as magical solutions and start seeing them as tools. Important tools for specific jobs. But tools nonetheless.

That maturation is actually healthy. Hype leads to disappointment. Realistic expectations lead to sustained investment and gradual improvement.

The Boston Dynamics Effect: Why One Good Robot Matters More Than Forty Mediocre Ones

Here's the thing about Boston Dynamics' new Atlas that matters most:

It showed that serious engineering still matters. In an age of startups and MVPs and "move fast and break things," Boston Dynamics took the time to fundamentally rethink their approach. They moved from hydraulic to electric. They rebuilt the entire system. They focused on precision instead of novelty.

The result is a robot that's less dramatic than the old one—no backflips, no parkour, no viral videos. But it's better. Measurably, demonstrably better at doing actual work.

That message is important for the entire industry to hear: the future isn't in flashy demos. It's in unglamorous improvement. It's in engineering that serves the problem, not ego.

When I left Las Vegas, I had realistic expectations. Robots aren't going to transform the world tomorrow. But they're going to incrementally, meaningfully improve certain sectors. And that's actually enough.

The robot that restored my faith in robotics wasn't the one that danced the best or looked the most human. It was the one that clearly, pragmatically solved a real problem in a way that was boring enough to actually work.

FAQ

What are humanoid robots?

Humanoid robots are machines designed to resemble and move like humans, typically with two arms, two legs, a torso, and a head with sensors. They're designed based on the assumption that human form factor is ideal for general-purpose tasks, though this assumption is increasingly challenged by engineers who argue that task-specific designs work better. Most humanoid robots at CES 2026 were still in prototype or early pilot stages rather than commercial deployment.

How much do industrial robots typically cost?

The cost varies dramatically by type and capability. A specialized industrial robotic arm designed for welding or assembly costs

What tasks are robots actually good at right now?

Robots excel at well-defined, repetitive tasks in controlled environments: welding, assembly, material handling, inventory management, and basic quality inspection. They perform poorly at tasks requiring perception of real-world variation, dexterity with delicate objects, or decision-making in unpredictable environments. The gap between what robots can do in demos and what they can do reliably in production remains substantial.

When will robots replace human workers at scale?

Full-scale replacement is unlikely for decades, if ever. What's actually happening is targeted automation of specific repetitive tasks, which frees humans to do more valuable work. Manufacturing has already seen significant automation without eliminating jobs because productivity increases create new economic activity. The transition will be gradual, sector-by-sector, over years rather than happening suddenly.

What's the difference between a cobot and an industrial robot?

Cobots (collaborative robots) are designed to work safely alongside humans without protective cages or barriers, using built-in force limiters and sensor feedback to prevent injury. Industrial robots are typically larger, more powerful, and operate in restricted areas away from humans. Cobots are more flexible and easier to reprogram, but less powerful. Industrial robots are more precise and faster but less versatile.

How realistic are the robot predictions for 2030?

Most commercial predictions for 2030 are overly optimistic about humanoid robots and too conservative about task-specific robots. Realistic expectations: significant growth in manufacturing and logistics robots (500% more deployments than today), moderate growth in healthcare and agriculture applications, minimal consumer robot adoption despite hype, and continued software being the limiting factor rather than hardware. Humanoid robots will remain niche market products without major breakthroughs in AI perception.

What's holding back robot adoption in most industries?

Three major factors: (1) Software remains immature—robots struggle with real-world variation and unpredictable conditions; (2) Integration costs are high and often exceed equipment costs; (3) Talent shortage of robotics engineers and integration specialists who can deploy and maintain systems. Hardware capability is less of a limiting factor than most assume.

How much can robot costs realistically drop?

Experts expect 20-40% cost reduction over five years through manufacturing scale and competition. However, customization costs for deployment won't drop as fast because they require skilled labor. A

Conclusion: The Unsexy Future Is Actually Worth Believing In

I left CES 2026 with something unexpected: genuine optimism about robotics, not because of flashy breakthroughs, but because of unglamorous progress.

The humanoid robots that dominated the headlines will mostly disappear. Companies that built them for the novelty factor will run out of funding. The ones that prove genuine value will survive and improve, but they won't be the robots everyone expected. They'll be the ones solving actual problems for actual customers.

The robots that impressed me most weren't the ones that looked impressive. They were the ones that were boring enough to work. The soft-gripper robot that could handle delicate objects. The collaborative arm that helped humans do their jobs better. The mobile platform moving inventory at scale in real warehouses.

These robots aren't going to make a viral video. They're not going to make headlines. But they're going to do real work, create real value, and prove that the robotics revolution isn't hype—it's just moving slower than people hoped.

Boston Dynamics' new Atlas represents the moment when serious engineering met realistic expectations. That moment matters. It signals that the industry is maturing. Moving from "can we build this" to "should we build this and can we make it work reliably."

Here's my actual prediction, stripped of hype: In five years, robot deployment in manufacturing and logistics will have tripled. Task-specific robots will be common. Humanoid robots will still be niche. Software will still be the limiting factor. Costs will have dropped modestly. Real value will have been created in specific sectors.

It won't be the sci-fi future everyone imagined. It will be better. It will be real.

And that's actually worth believing in.

You don't need robots to be perfect or humanoid or revolutionary. You need them to work. Reliably. Repeatedly. In ways that create genuine value.

That robot exists. I saw it. It wasn't the flashiest thing on the floor. But it was the one that made me think, "Yeah, this could actually change things."

That's how you know an innovation is ready for the world. Not when it impresses you with its capabilities. But when it convinces you it solves a real problem.

Boston Dynamics has done that. Whether the rest of the industry can follow is the question that will shape the next decade of robotics development.

Key Takeaways

- CES 2026 featured 40+ robots but only task-specific designs showed genuine commercial viability—humanoid robots remain largely novelty products

- Boston Dynamics' electric Atlas represents meaningful progress through pragmatic engineering focused on solving real problems instead of winning trade shows

- Manufacturing and logistics robots are scaling successfully with 340% deployment growth over 3 years, proving robotics ROI in specific sectors

- Software and AI perception remain the critical bottleneck—robots excel in controlled environments but fail 30-70% of the time in real-world variation

- Talent shortage of robotics engineers and integration specialists is a major constraint on deployment scaling through 2028

Related Articles

- Boston Dynamics Atlas Production Robot: The Future of Industrial Automation [2025]

- Sharpa's Humanoid Robot with Dexterous Hand: The Future of Autonomous Task Execution [2026]

- Switchbot's Onero H1 Laundry Robot: The Future of Home Automation [2025]

- Wing's Drone Delivery Expansion to 150 Walmarts Explained [2025]

- AI PCs Are Reshaping Enterprise Work: Here's What You Need to Know [2025]

- The Robots of CES 2026: Humanoids, Pets & Home Helpers [2025]

![CES 2026 Robots: The Good, Bad, and Revolutionary [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ces-2026-robots-the-good-bad-and-revolutionary-2025/image-1-1768250418250.jpg)