Climate Science Removed From Judicial Advisory: What Happened and Why It Matters

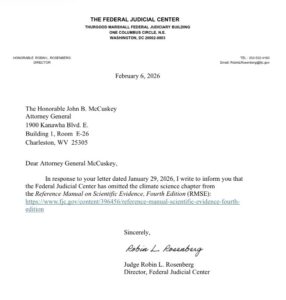

In early 2026, something quietly happened that didn't make the front page of most news outlets. A federal agency responsible for helping judges navigate scientific issues simply erased an entire chapter about climate change from one of its core reference documents. Not because the science was wrong. Not because peer reviewers found errors. But because a group of state attorneys general wrote a letter saying they didn't like what it said. According to Reuters, this decision was influenced by political pressure rather than scientific inaccuracies.

This isn't just another political squabble. It's a window into how science gets weaponized in courtrooms, how institutional independence can crumble under pressure, and what happens when political ideology starts rewriting the rules that guide our legal system.

Let me walk you through what actually happened, why it matters, and what this means for the future of science in American courts.

Understanding the Federal Judicial Center and Its Mission

The Federal Judicial Center exists for one specific reason: to help judges do their jobs better. It's a research and education agency established by statute as the backbone of judicial training and resources across the entire U.S. court system. As noted by the National Academies, the Center plays a crucial role in providing judges with reliable scientific information.

Think of it as a reference library for the judiciary. When federal judges face cases involving DNA evidence, statistical analysis, chemical exposure, or environmental science, they need reliable guidance. They're not scientists. Many haven't studied these fields since college. The Federal Judicial Center's job is to distill complex scientific concepts into language that judges can actually use to make informed decisions.

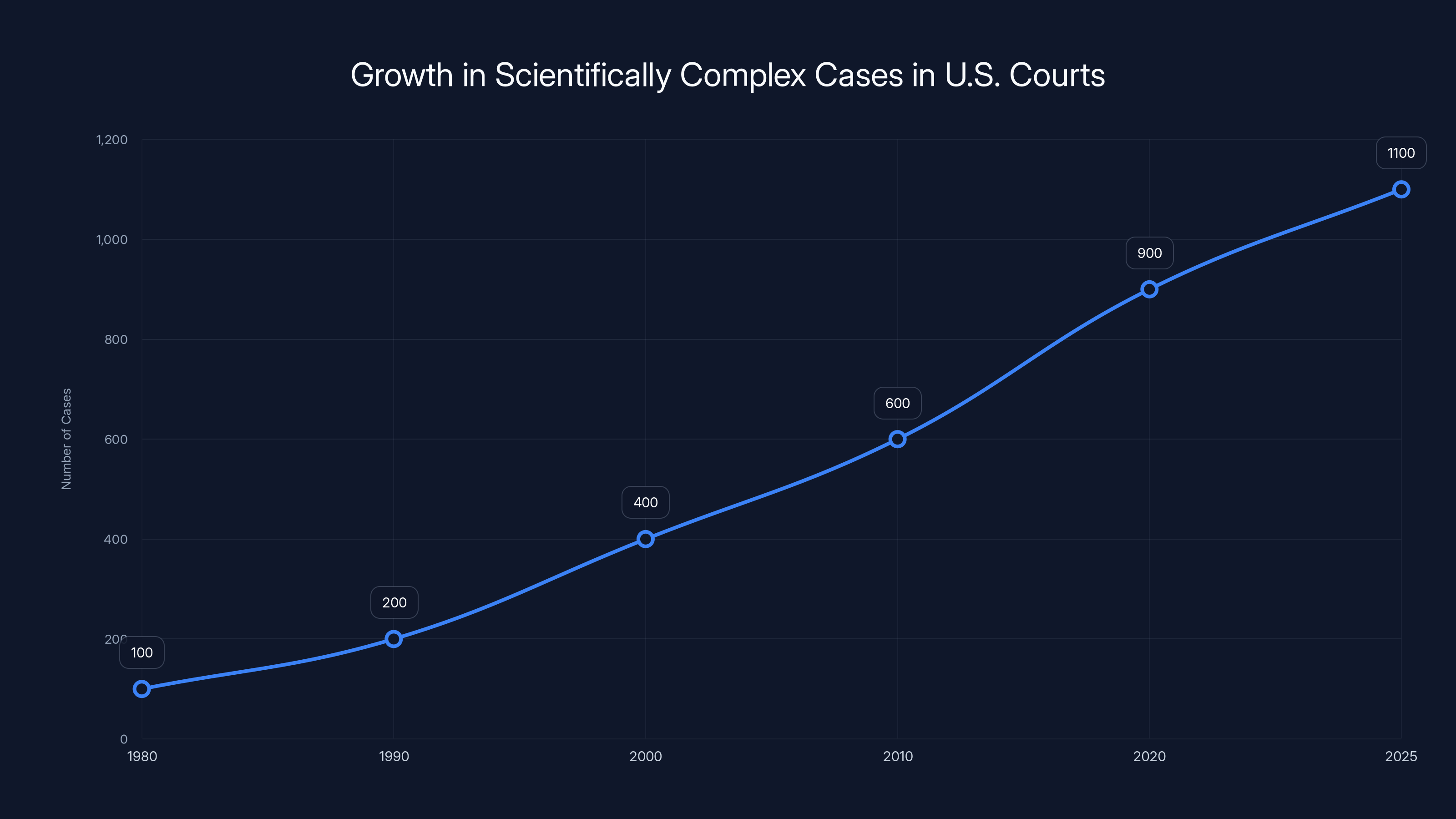

This role became even more important starting in the 1980s, when courts began seeing an explosion of scientifically complex cases. Patent disputes involving nanotechnology, medical malpractice cases hinging on toxicology, and environmental litigation requiring understanding of atmospheric chemistry. Judges needed trustworthy educational materials, fast.

In response, the Federal Judicial Center launched the "Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence" project. It became the go-to resource. Federal judges relied on it. State judges referenced it. Law schools taught from it. By the time the fourth edition was being prepared in 2025, this document had become something of a foundational text for how American courts handle scientific testimony and evidence.

The manual's development process was rigorous. The Federal Judicial Center collaborated with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, the gold standard for scientific consensus in the United States. These aren't fringe organizations. The National Academies literally advises Congress on scientific policy.

For the fourth edition, two Columbia University climate scientists were brought in to write a chapter on climate change. They weren't activists. They were academically credentialed researchers tasked with translating peer-reviewed climate science into language judges could understand and apply in court.

The chapter included information about what the scientific consensus actually said. It cited the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. It explained attribution science—the ability to determine what portion of warming is caused by human activity versus natural cycles. It provided judges with a framework for evaluating climate-related testimony and evidence that might appear in their courtrooms.

When the manual was released in December 2025, it seemed like a straightforward accomplishment. Expert-written. Peer-reviewed. Authoritative. Useful.

Then the backlash started. According to Fox News, legal experts criticized the manual for perceived bias in its presentation of climate science.

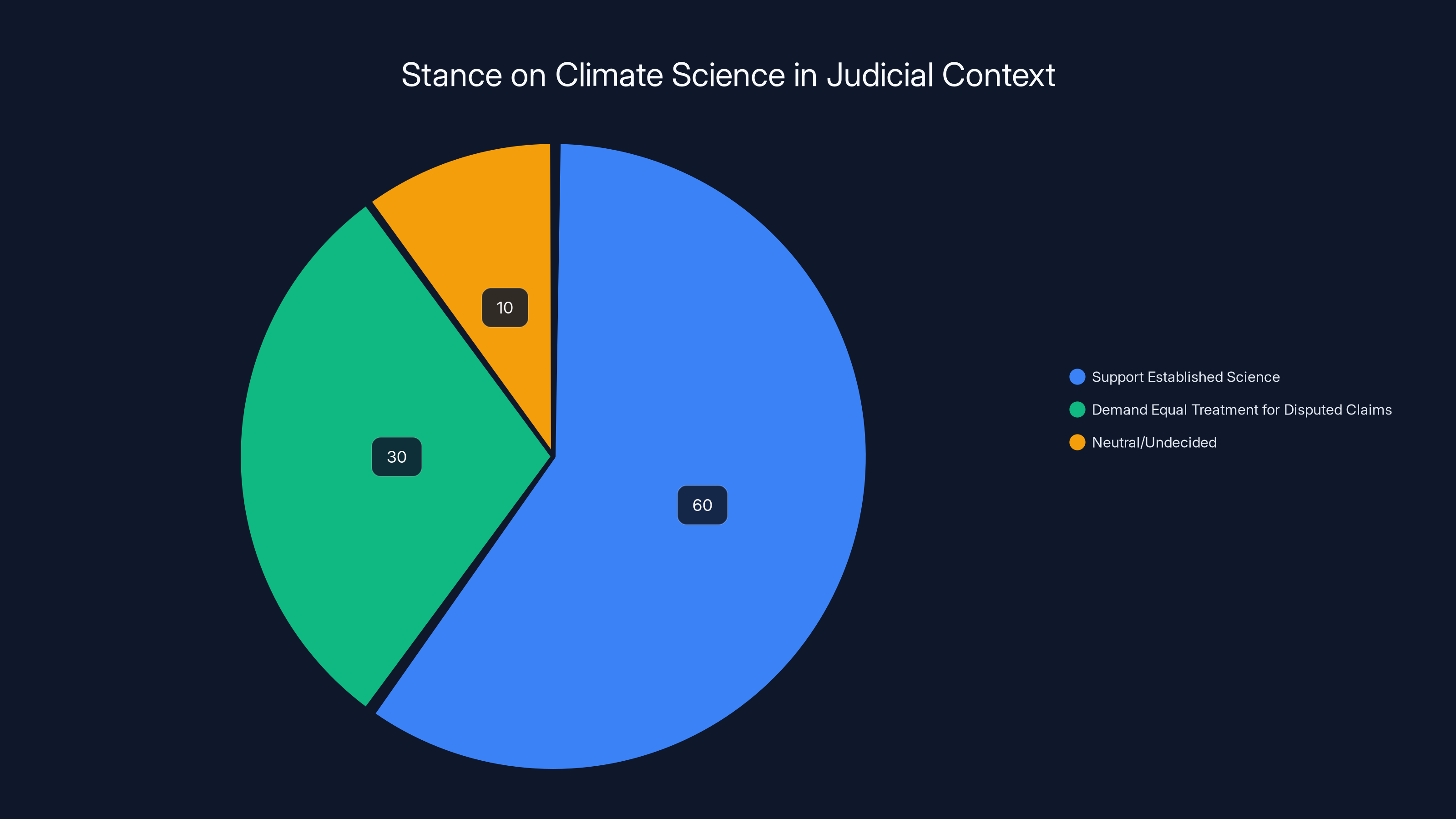

Estimated data suggests that a majority support established climate science in judicial contexts, while a significant minority demand equal treatment for disputed claims.

The Republican Attorneys General's Letter: A Closer Look at the Complaint

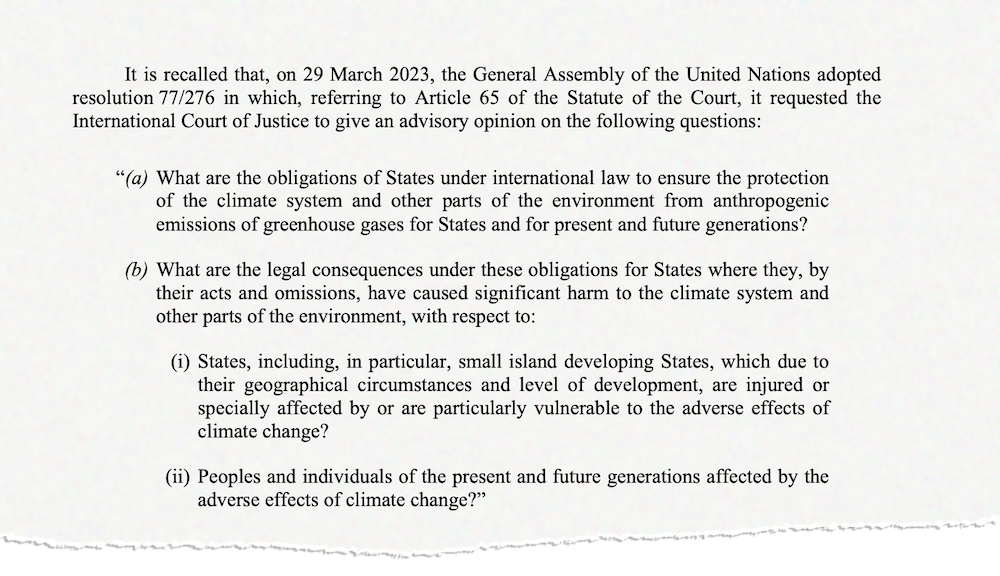

At the end of January 2026, the Federal Judicial Center received a letter that would change everything. It came from a coalition of attorneys general from Republican-leaning states. They had a problem with the climate chapter. As reported by The Center Square, the letter argued that the manual's climate chapter violated the principle of judicial impartiality.

The letter was carefully written. It wasn't a rant. It presented arguments designed to sound reasonable while obscuring something more fundamental: the signatories wanted the Federal Judicial Center to stop treating established science as established science.

Here's how they framed it. The letter argued that the manual's climate chapter violated the principle of judicial impartiality. They claimed that by stating human-caused climate change as fact, the Federal Judicial Center was "placing the judiciary firmly on one side of some of the most hotly disputed questions in current litigation."

Read that carefully. They weren't saying the science was wrong. They were saying that because people were litigating about it, the Federal Judicial Center shouldn't treat it as settled.

This is a remarkable rhetorical move. It inverts the usual relationship between science and litigation. Normally, courts rely on scientific consensus to evaluate expert testimony. The logic goes: if 99% of climate scientists agree on something, and someone wants to present testimony contradicting that consensus, judges should know that the weight of evidence is overwhelmingly against the witness.

But the attorneys general were essentially arguing that if anyone is litigating a position, no matter how scientifically baseless, the Federal Judicial Center should treat both sides as equally valid.

Let's look at their specific complaints. The letter cited three direct quotes from the climate chapter:

First, that human activities have "unequivocally warmed the climate." The attorneys general objected to the certainty language here. They claimed this was presented as fact when it should be presented as contested.

Second, that it is "extremely likely" human influence drives ocean warming. The letter treated this probabilistic language—which is actually how science communicates uncertainty—as if it were propaganda.

Third, that researchers are "virtually certain" about ocean acidification. Again, they treated established science as if it were opinion.

The letter also took issue with the manual's characterization of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as an "authoritative science body." To support their objection, they cited a Canadian public policy think tank that disagreed with this assessment. A think tank. Not peer-reviewed research. Not scientific evidence. A policy organization.

Now, to be fair, the letter did raise a few potentially legitimate points. It mentioned that the climate chapter gave specific legal suggestions for how to approach certain issues in court. It also noted that the manual emphasized one or two recent studies that hadn't yet been validated by extensive follow-up research.

These are reasonable critiques. A reference manual for judges should be careful about suggesting specific legal outcomes. It should avoid overweighting studies that lack independent verification.

But here's the thing: the attorneys general didn't ask for revisions to address these concerns. They demanded the entire chapter be deleted. "Treated contested litigation positions as settled fact," they wrote, as if litigation itself determined scientific truth.

It's hard to overstate how backward this reasoning is. In the American legal system, courts are supposed to rely on established scientific understanding to evaluate evidence. Scientific consensus should inform judicial decision-making. It shouldn't be held hostage to whoever files the most lawsuits.

Yet here's what happened next.

The number of scientifically complex cases in U.S. courts has increased significantly since the 1980s, highlighting the growing importance of resources like the Federal Judicial Center's Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence. (Estimated data)

The Federal Judicial Center's Capitulation: How Institutional Independence Failed

Within weeks of receiving the letter, the Federal Judicial Center caved. Not partially. Not with revisions addressing legitimate concerns. They deleted the entire climate chapter. This decision was covered by The Wall Street Journal, highlighting the lack of transparency in the decision-making process.

This wasn't a decision made transparently. There was no public announcement. No statement explaining the reasoning. The discovery came when reporters noticed that while the foreword by Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan still mentioned the climate chapter, the chapter itself had vanished from the actual document.

It's a strange kind of institutional cowardice. The Federal Judicial Center essentially admitted that it had the wrong answer but wouldn't say why it was changing course.

What makes this especially notable is that the Federal Judicial Center's entire purpose is to provide judges with accurate scientific information. That's literally its statutory mission. Removing a chapter on climate science doesn't serve judges. It leaves them less informed about an area of science that increasingly shows up in their courtrooms.

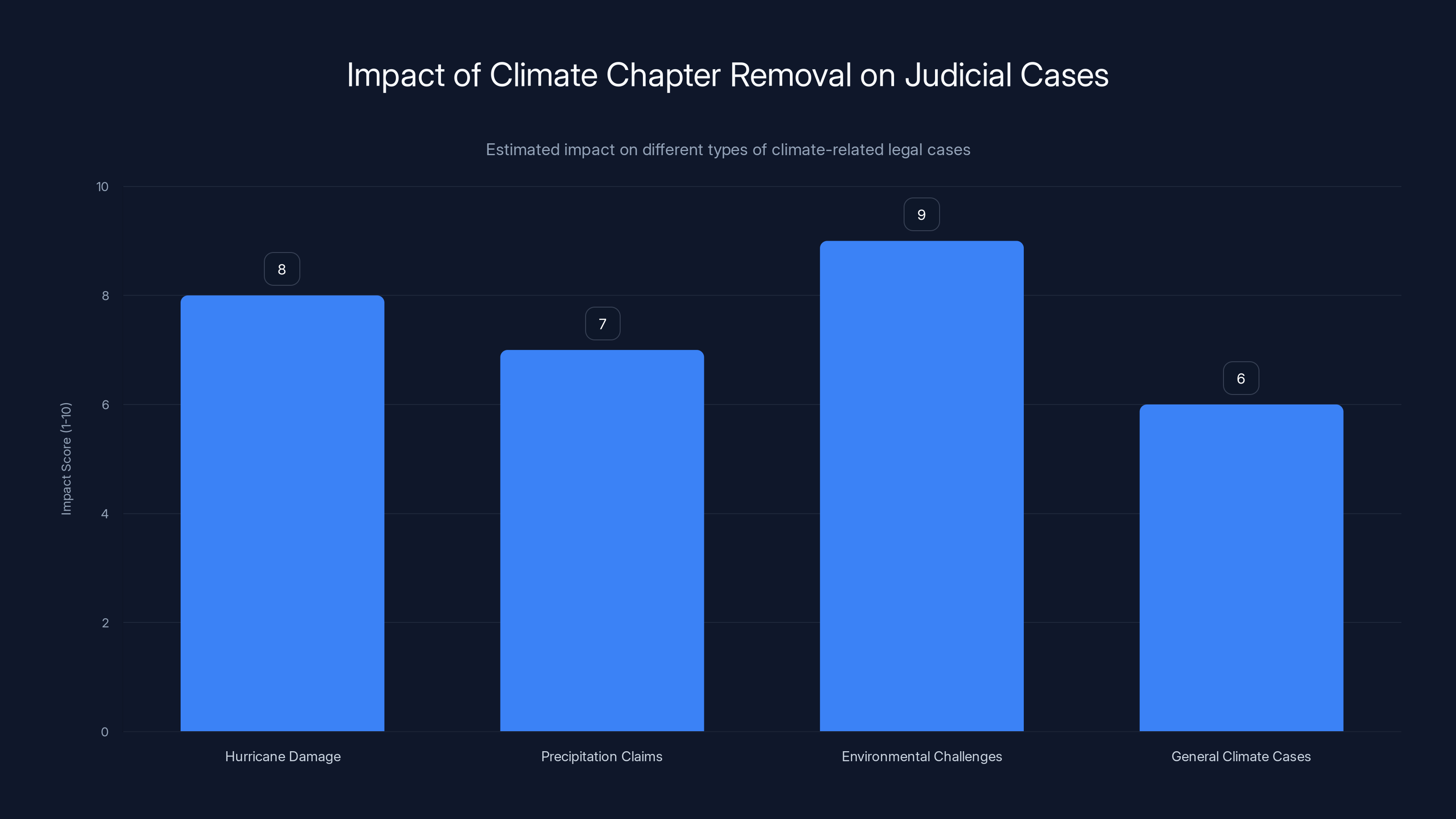

Insurance companies are suing over whether climate change was a factor in hurricane damage. Property owners are filing claims based on changing precipitation patterns. Environmental groups are challenging decisions based on outdated climate data. All of these cases require judges to understand the actual state of climate science.

By removing the chapter, the Federal Judicial Center made judges worse at their jobs. Judges now have less access to authoritative scientific information about one of the most litigated scientific questions of our time.

Why did the Federal Judicial Center fold so quickly? That's not entirely clear. Perhaps leadership feared political repercussions. Perhaps they wanted to avoid further controversy. Perhaps they underestimated how problematic their capitulation would appear.

But the result is clear: an institution designed to protect judicial independence through scientific accuracy abandoned that mission when presented with political pressure.

The Broader Context: Science in American Courtrooms

To understand why this matters, you need to understand how science actually functions in legal disputes.

When a case involves scientific evidence, both sides can hire expert witnesses. These experts testify about what the science says. The opposing side cross-examines them. A judge or jury decides which expert testimony is more credible.

But here's the problem: judges and juries aren't scientists. They don't have the training to evaluate the difference between a genuine scientific expert and a charlatan. They can't always tell the difference between a study published in a major peer-reviewed journal and a study published by an industry-funded organization pretending to be legitimate.

This is where the Federal Judicial Center's reference manuals become crucial. They help judges understand the landscape of scientific evidence. They explain how scientific uncertainty actually works. They help distinguish between consensus and fringe positions.

Without this guidance, courtrooms become susceptible to what's called "junk science." An industry can find a handful of fringe researchers willing to testify that a chemical isn't dangerous, a product doesn't cause injury, or climate change is natural. If a judge doesn't understand the actual state of scientific consensus, he or she might treat these fringe voices as equally valid to the mainstream consensus.

This has happened repeatedly throughout legal history. Tobacco companies financed researchers to testify that smoking wasn't dangerous. Asbestos manufacturers hired experts to claim asbestos exposure wasn't harmful. Lead paint makers argued that lead wasn't actually toxic.

In each case, the strategy was similar: create the appearance of scientific controversy where there was actually consensus. If you can make a judge think that the scientific community is divided, you've created reasonable doubt. And reasonable doubt wins cases.

The climate chapter in the Federal Judicial Center's reference manual was designed to prevent exactly this problem. It explained how scientific consensus actually works. It helped judges understand the difference between genuine scientific uncertainty and manufactured doubt.

Removing it makes judges more vulnerable to exactly these arguments.

Estimated data shows that the removal of the climate chapter significantly impacts judges' ability to handle climate-related cases, with environmental challenges being most affected.

What the Evidence Actually Shows: The Climate Science the Manual Described

Let's step back and consider what the removed chapter actually said. What was so threatening about it?

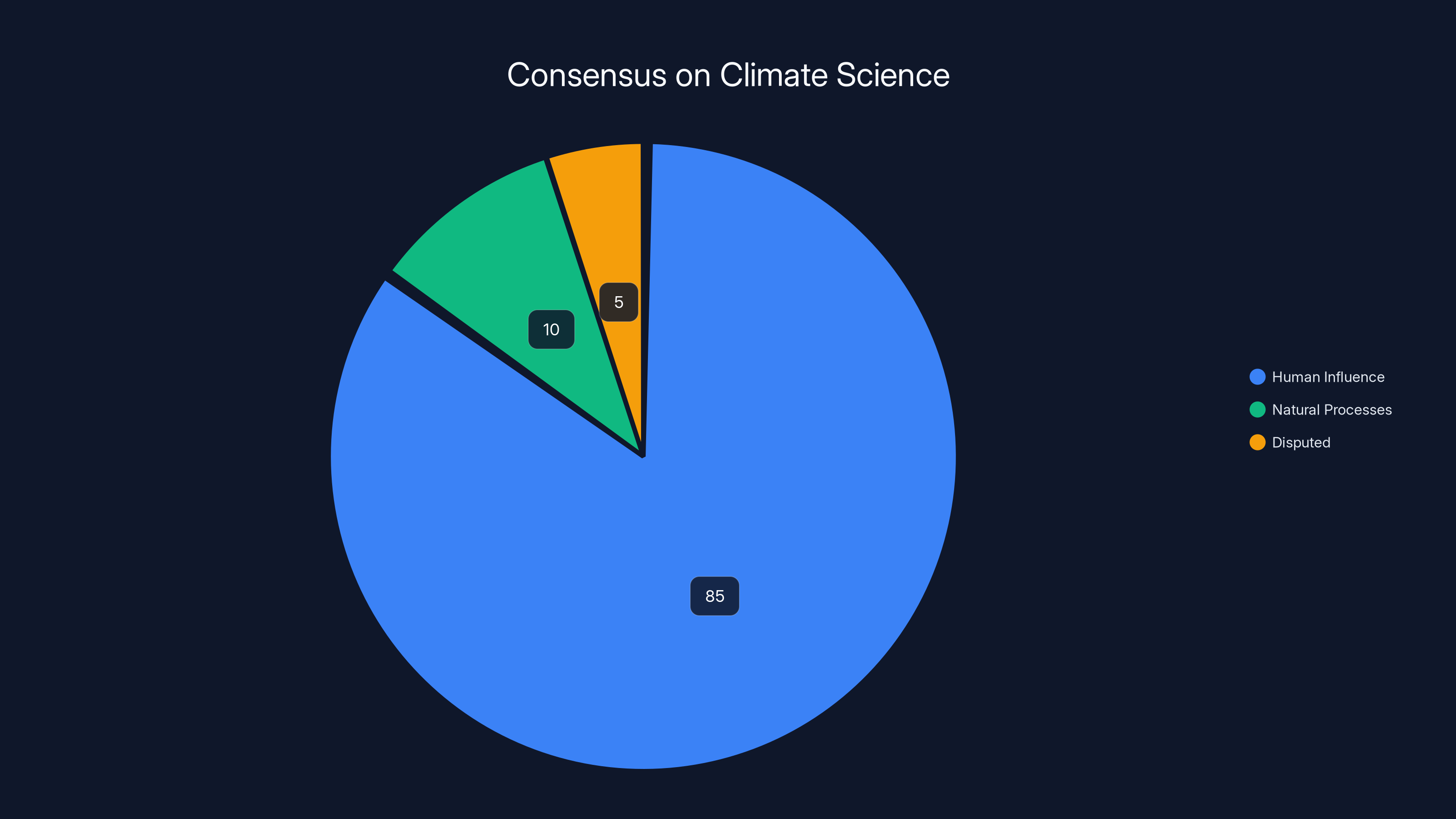

It said that human activities have unequivocally warmed the climate. This is based on decades of research. Multiple lines of evidence—atmospheric measurements, ocean temperatures, ice sheet dynamics, paleoclimate records—all point to the same conclusion. The warming is real. Humans caused it. This is true regardless of anyone's political preferences.

It said that human influence drives ocean warming with extremely high likelihood. Again, this is supported by the physics of heat retention. Carbon dioxide traps heat. More CO2 means more heat retention. Ocean warming is a direct consequence. You can replicate this in laboratory conditions.

It said researchers are virtually certain about ocean acidification. The chemistry here is straightforward. CO2 dissolves in seawater and forms carbonic acid. More CO2 means more acid. This changes the pH of seawater. The evidence is measurable and reproducible.

None of this is contested within the scientific community. Major scientific organizations worldwide—the National Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society, the European Academy of Sciences—all agree on these basic facts.

Yet the attorneys general wanted a judicial reference manual to present these facts as if they were genuinely disputed within science. They weren't. The dispute is political, not scientific.

There's an important distinction here. Science does involve genuine uncertainty and ongoing debate. Researchers argue constantly about details. They disagree about methodologies. They challenge each other's conclusions.

But this scientific debate happens within a framework of consensus about the basics. Scientists debate whether the Earth will warm by 2 degrees or 3 degrees by 2100. They don't debate whether warming is happening. Scientists debate the relative importance of different feedback mechanisms in amplifying warming. They don't debate whether those mechanisms exist.

The Federal Judicial Center's removed chapter reflected this distinction. It presented the scientific consensus clearly while acknowledging areas where genuine uncertainty remained.

Removing it doesn't serve judicial accuracy. It serves political ideology.

The Precedent This Sets: Institutional Vulnerability

Here's what should worry you about this situation, regardless of your politics.

The Federal Judicial Center isn't unique in having a mission to provide accurate, apolitical information. Most federal agencies have similar responsibilities. The National Institutes of Health provides medical guidance. The EPA provides environmental information. The USGS provides geological data. The National Weather Service provides climate forecasts.

All of these agencies are now watching what happened to the Federal Judicial Center. The message is clear: if enough politicians complain about what you're saying, you'll delete it, regardless of whether it's accurate.

This creates perverse incentives. It rewards political pressure over scientific accuracy. It suggests that the way to influence federal scientific guidance isn't through peer review or research, but through political intimidation.

Future administrations—Democratic or Republican, doesn't matter—will take note. If they don't like something a scientific agency is saying, they can pressure it to delete that information. Eventually, federal agencies won't provide any information that anyone finds politically inconvenient.

That's not how scientific institutions are supposed to work. Scientific institutions are supposed to follow evidence wherever it leads, regardless of political consequences. They're supposed to resist pressure to distort findings for political gain.

The Federal Judicial Center had an opportunity to defend that principle. To say: "We reviewed your complaints. Some had merit. We're making specific revisions to address those legitimate concerns. But we're keeping the chapter because judges need accurate information about this topic."

Instead, they folded completely. And in doing so, they weakened every other federal scientific institution.

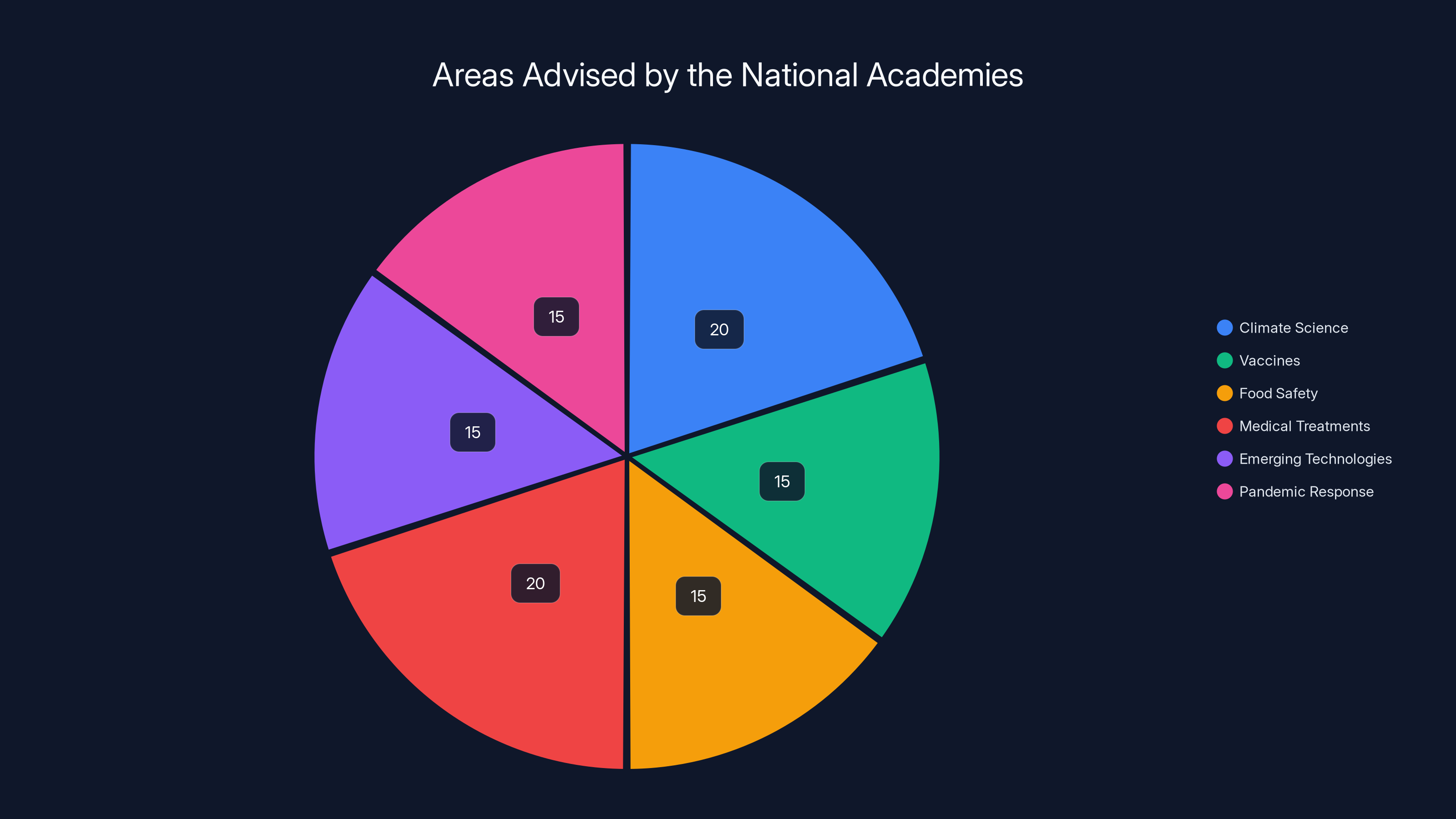

The National Academies provide guidance across diverse areas such as climate science, vaccines, and food safety, with each area receiving significant attention. Estimated data.

Why Judges Actually Need This Information: Real-World Cases

You might wonder: do judges actually need guidance on climate science? Doesn't this seem like a political issue, not a legal one?

Actually, no. Climate science shows up in courtrooms constantly, in ways that have nothing to do with partisan politics.

Consider insurance disputes. A hurricane destroys a coastal property. The insurance company denies the claim, arguing that the damage was caused by normal weather variation, not anything the policyholder should have anticipated. The property owner argues that climate change has changed hurricane behavior, increasing risk. Who's right? A judge needs to understand the science of hurricane behavior and climate change to evaluate the evidence.

Or consider property tax assessments. A property is valued based on presumed future use. If sea level rise is going to inundate it, that affects current value. But sea level rise predictions depend on understanding climate science. A judge determining whether a property valuation was accurate needs to understand what the science actually says.

Or environmental permitting. A company wants to build a power plant. Environmental groups challenge it, arguing that climate impacts weren't adequately considered in the permit decision. To evaluate this dispute, a judge needs to understand what we know about climate change and its impacts.

These are routine legal disputes. They're not political in nature. They involve genuine technical questions that benefit from expert guidance.

Without the Federal Judicial Center's reference materials, judges lack authoritative guidance. They're more likely to be swayed by whichever side presents the slicker expert witness. Scientific accuracy becomes less important than persuasive presentation.

This serves no one's interests except those with the resources to hire charismatic but questionable experts.

The Role of the National Academies: Why Their Collaboration Mattered

One detail worth emphasizing: the Federal Judicial Center didn't write this chapter alone. They partnered with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

The National Academies are the closest thing the U.S. has to an official arbiter of scientific consensus. Congress requires federal agencies to use National Academies guidance when making policy. The organization literally exists to translate scientific evidence into actionable information for decision-makers.

When the National Academies endorses something as scientifically sound, that carries enormous weight. It means hundreds of peer reviewers have examined the material. It means the organization's reputation stands behind the accuracy.

By collaborating with the National Academies on the climate chapter, the Federal Judicial Center was essentially saying: "We've taken the most authoritative scientific guidance available and translated it for judges."

Removing the chapter undermines that entire collaborative relationship. It suggests that National Academies guidance isn't actually authoritative if politicians don't like it.

This has implications beyond just climate science. The National Academies advises on vaccines, food safety, medical treatments, emerging technologies, pandemic response, and dozens of other areas where scientific accuracy matters for legal and regulatory decisions.

If Federal Judicial Center can simply erase National Academies guidance under political pressure, why should any agency rely on it? Why not just develop in-house guidance that's easier to modify when politicians complain?

It's a slow-motion dismantling of the institutional structures that keep science and politics appropriately separated.

Estimated data shows that approximately 85% of scientific consensus attributes climate change to human activities, with only 10% to natural processes and 5% as disputed, highlighting the strong agreement within the scientific community.

The Irony: Justice Elena Kagan's Foreword

There's an almost tragicomic detail here. Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan wrote the foreword to the fourth edition of the Reference Manual. In that foreword, she explicitly mentions the climate chapter.

But when the actual document was published online, the chapter was gone.

Justice Kagan didn't approve this deletion. The Federal Judicial Center simply went ahead and removed the chapter without updating her foreword or explaining the discrepancy to her.

This raises interesting questions about who actually makes decisions at the Federal Judicial Center. Did leadership make this call unilaterally? Was there any internal debate? Did anyone push back on the decision to erase an entire chapter because of political complaints?

We don't know, because the Federal Judicial Center hasn't explained its reasoning publicly.

But the existence of Kagan's foreword—mentioning a chapter that no longer exists—perfectly captures the absurdity of the situation. It's a dead text. A ghost section. Mentioned but absent. Like Schrödinger's scientific guidance.

What This Means for Future Scientific Guidance

We're now in uncertain territory. The Federal Judicial Center has implicitly established a precedent: if you get enough political pressure about something in a reference manual, that content will disappear.

Other chapters should be nervous. The manual covers DNA identification, statistical analysis, and chemical exposures. All of these have become politically charged in some contexts.

Will the next administration that views DNA evidence skeptically demand deletion of that chapter? Will pharmaceutical companies pressure the removal of sections on toxicology that might be used against them in product liability cases? Will industries opposed to environmental protection demand removal of material on environmental science?

Once you establish that political pressure can erase scientific guidance, every institution becomes vulnerable. And every scientist working within those institutions becomes cautious about what they write.

Scientists self-censor when they know that writing something politically unpopular might lead to institutional pressure. They soften their language. They hedge their conclusions. They emphasize uncertainty over consensus.

This doesn't make for better science. It makes for weaker science. And weaker science in judicial guidance means worse decisions in court.

The Contrast With Scientific Integrity Standards

Most scientific institutions have explicit policies about research integrity and the presentation of findings. The National Academies, for instance, has extensive procedures for ensuring that recommendations accurately represent the state of scientific knowledge, regardless of political implications.

Universities have faculty governance structures that protect researchers from being pressured to modify their conclusions.

Peer-reviewed journals have editorial processes designed to ensure that findings are presented accurately and that peer reviewers can't suppress inconvenient results.

The Federal Judicial Center, by removing the climate chapter without explanation, violated these principles. It didn't follow any transparent process. It didn't invite peer review of the deletion decision. It didn't explain its reasoning publicly. It simply erased content because politicians complained.

For an institution created by statute to serve the judiciary, this is a particularly troubling precedent. The Federal Judicial Center should be a model of institutional integrity. Instead, it's become a cautionary tale about what happens when institutions abandon principle under political pressure.

International Implications: What Other Countries Are Watching

This incident didn't go unnoticed internationally. Other democracies watch how America handles science in its institutions. When a major federal agency caves to political pressure and erases scientific information, it sends a signal.

Scientists in other countries note this. Scientific organizations note this. Governments note this. The message is that American scientific institutions aren't as independent or robust as they claim to be.

This matters because science is increasingly international. Climate science involves researchers from every country. Major discoveries require collaboration across borders. If American scientific institutions lose credibility because they capitulate to political pressure, American scientists lose influence in international scientific collaboration.

It also matters for the credibility of American expertise. Why should a foreign judge rely on American scientific testimony if American scientific institutions are willing to erase information under political pressure?

The Path Forward: What Could Restore Institutional Integrity

The Federal Judicial Center could reverse this decision. It could restore the climate chapter and explain why it did so. It could establish procedures to prevent future deletion of scientific material under political pressure. It could commit to transparent, peer-reviewed processes for any future modifications to reference materials.

This would require courage. It would mean absorbing more political criticism. But it would also restore the institution's credibility and its actual ability to serve its statutory mission.

Alternatively, other institutions could learn from this cautionary tale. Agencies could establish stronger protections for scientific content. Congress could pass legislation requiring transparent, peer-reviewed processes for any modifications to federal scientific guidance.

Scientists within federal agencies could organize and push back against pressure to distort findings. Not confrontationally, but clearly and publicly, explaining why accurate science matters for institutional credibility and effective decision-making.

But these things require people willing to prioritize institutional integrity over political convenience. The Federal Judicial Center decided not to be one of those institutions.

Conclusion: The Danger of Institutional Erosion

This incident matters because it's not really about climate change, even though climate change is the stated issue.

It's about whether federal institutions can maintain integrity when facing political pressure. It's about whether scientific accuracy matters more than appeasing politicians. It's about whether institutions designed to serve the public are willing to do their jobs even when it's unpopular.

Right now, the answer appears to be no.

A federal agency created to help judges make better-informed decisions about science simply erased guidance because politicians didn't like what it said. Not because the science was wrong. Not because peer reviewers found errors. But because someone complained.

This corrodes institutional credibility in subtle but profound ways. When institutions prioritize political peace over scientific accuracy, they lose the ability to serve their actual purpose. They become less useful to the people who depend on them.

Judges now have less guidance. The public has less faith in federal scientific institutions. And future agencies know that political pressure works.

That's a bad outcome for everyone who depends on accurate scientific information. Which, if you think about it, is basically all of us.

FAQ

What is the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence?

The Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence is a document prepared by the Federal Judicial Center in collaboration with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. It serves as an authoritative guide for judges handling cases involving scientific evidence, covering topics like DNA identification, statistical analysis, chemical exposures, and climate change. The fourth edition, released in December 2025, included a chapter on climate science that was subsequently removed after political complaints.

Why did the Federal Judicial Center remove the climate chapter?

The Federal Judicial Center removed the climate chapter in response to a letter from Republican state attorneys general who objected to the chapter's treatment of human-caused climate change as established scientific fact. The attorneys general argued that describing climate science in terms of scientific consensus placed the judiciary on one side of a contested legal issue. The Federal Judicial Center capitulated to this pressure without public explanation or transparent reasoning, deleting the entire chapter rather than making targeted revisions.

What specific claims in the removed chapter were controversial?

The climate chapter made three main claims that triggered complaints: first, that human activities have "unequivocally warmed the climate"; second, that it is "extremely likely" that human influence drives ocean warming; and third, that researchers are "virtually certain" about ocean acidification. The attorneys general objected to these statements being presented with scientific confidence rather than as contested positions. However, these statements accurately reflect the consensus of the global scientific community and are supported by extensive peer-reviewed research.

How does this decision affect judges in actual courtrooms?

Judges now have less authoritative guidance when evaluating climate-related scientific testimony in cases involving insurance disputes, environmental permitting, property valuations, and other climate science matters. Without the reference material, judges may be more susceptible to misleading expert testimony and less able to distinguish between mainstream scientific consensus and fringe positions. This could lead to legally incorrect decisions based on misunderstood or deliberately distorted science.

What is the relationship between scientific consensus and litigation?

Scientific consensus should inform how courts evaluate expert testimony. If 99 percent of climate scientists agree on something, courts should understand this context when evaluating testimony from the tiny minority that disagrees. However, the removed chapter's critics argued that the existence of litigation itself meant the science shouldn't be treated as settled. This inverts the proper relationship between science and law. Courts should rely on scientific consensus to evaluate evidence, not treat the fact of litigation as evidence that consensus doesn't exist.

Could other federal scientific guidance be deleted under similar political pressure?

Yes, this decision establishes a troubling precedent. Other federal agencies providing scientific guidance to decision-makers—the National Institutes of Health, the EPA, the USGS, the FDA—are now on notice that political pressure can lead to deletion of scientific content. This creates incentives for self-censorship among agency scientists and undermines the institutional independence that federal scientific agencies are designed to maintain. The precedent could encourage future administrations to demand removal of any scientific guidance they find politically inconvenient.

Why does the Supreme Court Justice's foreword still mention the removed chapter?

Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan wrote the foreword to the fourth edition of the Reference Manual, explicitly mentioning the climate chapter. The Federal Judicial Center removed the chapter without updating Kagan's foreword or explaining the deletion to her. This creates a discrepancy where the document's official introduction references a chapter that no longer exists, suggesting the decision was made by agency leadership without transparency about how it was authorized or what the justification was.

How does this compare to scientific standards at universities and journals?

Universities, peer-reviewed journals, and scientific organizations all have procedures designed to protect the integrity of scientific guidance. These include faculty governance, peer review, and transparent editorial processes. The Federal Judicial Center, by contrast, simply deleted content under political pressure without any of these protective mechanisms. For an institution created by statute to serve the judiciary, this represents a failure to maintain the scientific standards that are supposed to guide federal institutions.

Key Takeaways

- The Federal Judicial Center removed its entire climate science chapter from the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence after Republican state attorneys general complained it treated human-caused climate change as fact

- The attorneys general's strategy inverted the proper relationship between science and litigation by arguing that because climate science is contested in court, it shouldn't be presented as scientifically established

- Judges now have less authoritative guidance when evaluating climate-related expert testimony in insurance disputes, environmental cases, and property valuations

- The capitulation establishes a dangerous precedent: federal scientific institutions can be pressured to erase accurate information if politicians object, regardless of the information's accuracy

- Other federal agencies providing scientific guidance—NIH, EPA, USGS, FDA—are now on notice that political pressure can lead to deletion of scientific content, creating incentives for self-censorship

![Climate Science Removed From Judicial Advisory: What Happened [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/climate-science-removed-from-judicial-advisory-what-happened/image-1-1770727040848.jpg)