How the Government Can Demand Your Data Without a Judge's Permission

Last year, a Pennsylvania-based activist running an anonymous Instagram account documenting immigration enforcement suddenly received unexpected company. Federal agents showed up at their door asking questions about a critical email they'd sent months earlier. Unbeknownst to them, the Department of Homeland Security had already demanded their personal information from Meta. The account owner only discovered this when their lawyer filed a lawsuit.

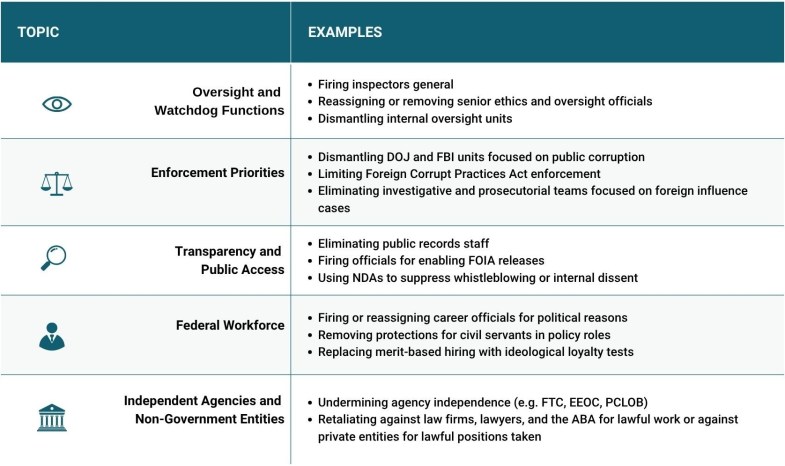

This isn't an isolated incident. It's part of a larger pattern where federal agencies have discovered a legal workaround that makes getting your data remarkably easy. They don't need a warrant. They don't need a judge. They don't even need to convince anyone they have legitimate evidence of wrongdoing.

What they use instead are administrative subpoenas.

Unlike the subpoenas you see in legal dramas where attorneys argue before a judge, administrative subpoenas are issued unilaterally by federal agencies themselves. No judicial review. No oversight. Just a demand from the government to a tech company, and increasingly, that company hands over the data.

For people who've been exercising their First Amendment rights, documenting police activity, criticizing elected officials, or simply participating in political protest, this mechanism has become a legitimate concern. And for tech companies trying to navigate the murky waters between user privacy and government pressure, it presents an ethical minefield.

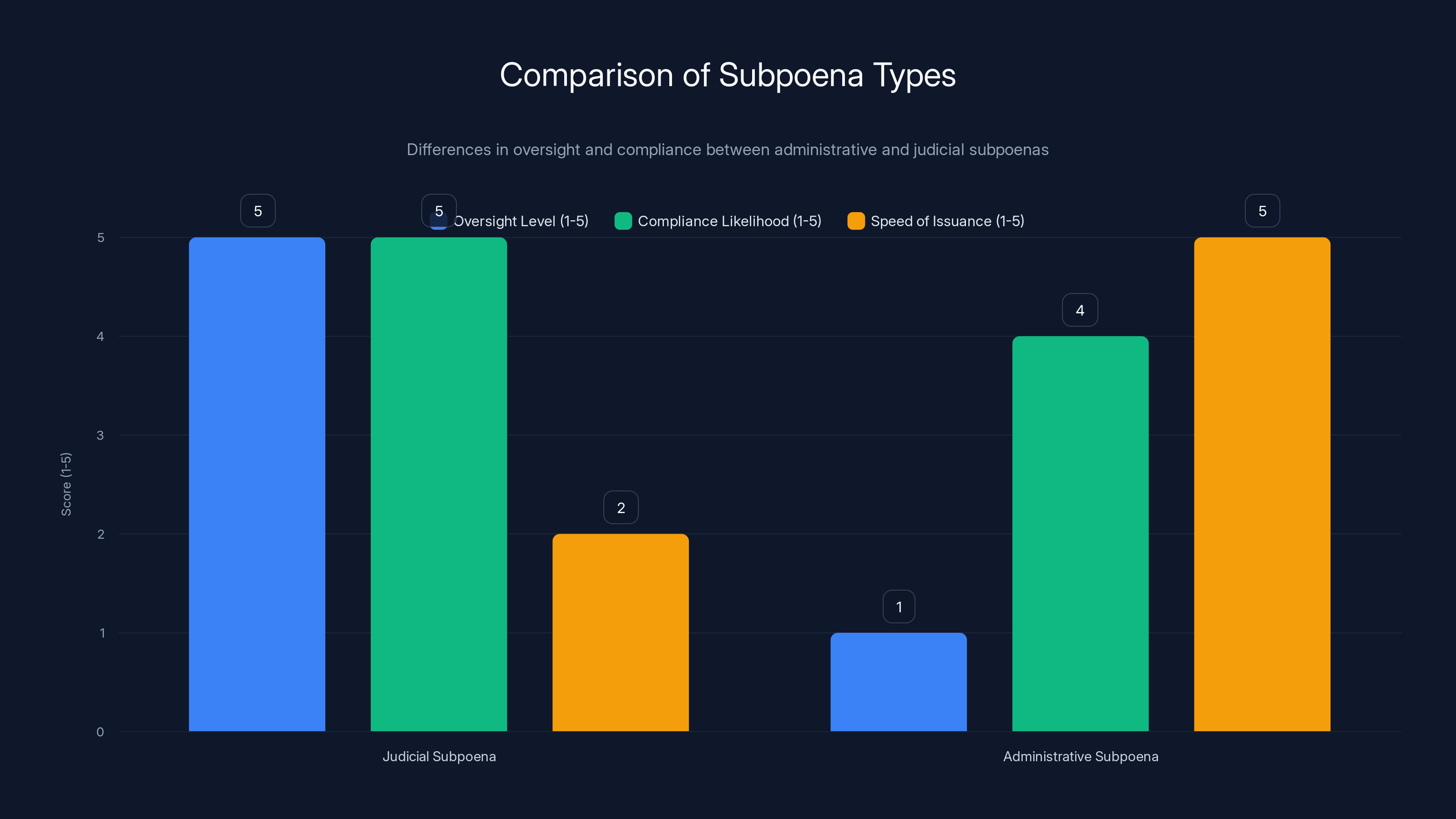

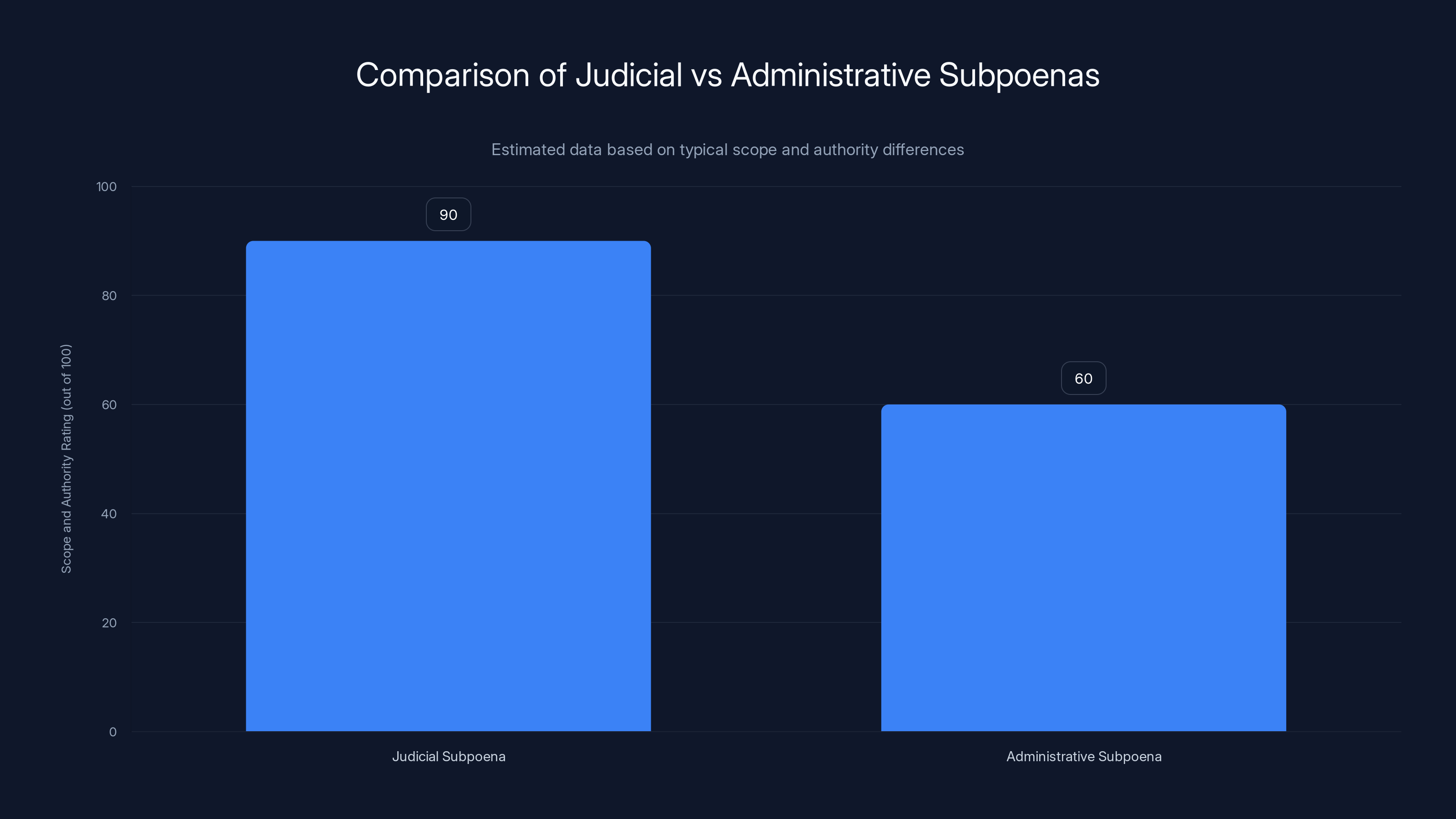

The difference between these two types of subpoenas matters enormously. A judicial subpoena requires a prosecutor or investigator to convince a judge they have sufficient evidence of a crime. An administrative subpoena requires nothing more than an agency employee deciding they want information.

Understanding how this system works, what data it can access, and how to protect yourself requires looking at the mechanics, the recent incidents, and the broader implications for digital privacy.

The Technical Difference Between Judicial and Administrative Subpoenas

When most people think about a subpoena, they picture a formal legal document authorized by a court. Judicial subpoenas work this way. Someone seeking information must demonstrate to a judge that they have a legitimate legal reason to access it. That judge then reviews the evidence, ensures the request is reasonable and proportional, and only if satisfied, authorizes the subpoena.

This process, while not perfect, creates a meaningful check on government power. The judge acts as an intermediary. They can reject unreasonable requests. They can limit the scope of what can be demanded. They can set conditions on how the information is used.

Administrative subpoenas skip this entire step.

Instead of going to a judge, a federal agency simply issues the subpoena themselves. The legal authority comes from a statute that already authorizes the agency to seek certain information. No additional approval required. No judicial review. No check on whether the request is proportional or actually connected to legitimate law enforcement activity.

The difference in scope is critical. Judicial subpoenas can demand almost anything relevant to a case. Administrative subpoenas, by statute, are technically limited to specific types of information. They cannot demand the contents of emails, messages, or other communications. They cannot demand location data. They cannot demand browsing history.

What they can demand is substantial: basic subscriber information like names, addresses, phone numbers, email addresses, account creation dates, login times, IP addresses used to access accounts, and the devices used to access them.

For an anonymous account, this information is the skeleton key. Once you know the IP address, the email used to create the account, and the approximate times of login, identifying the person behind that account becomes possible.

From a technical standpoint, tech companies receive these subpoenas and face a decision. The law doesn't require them to comply with administrative subpoenas the way it does with judicial ones. A company could theoretically refuse. But in practice, most don't. The compliance burden is lower, the legal ambiguity is higher, and pushing back requires committing resources to fight the government.

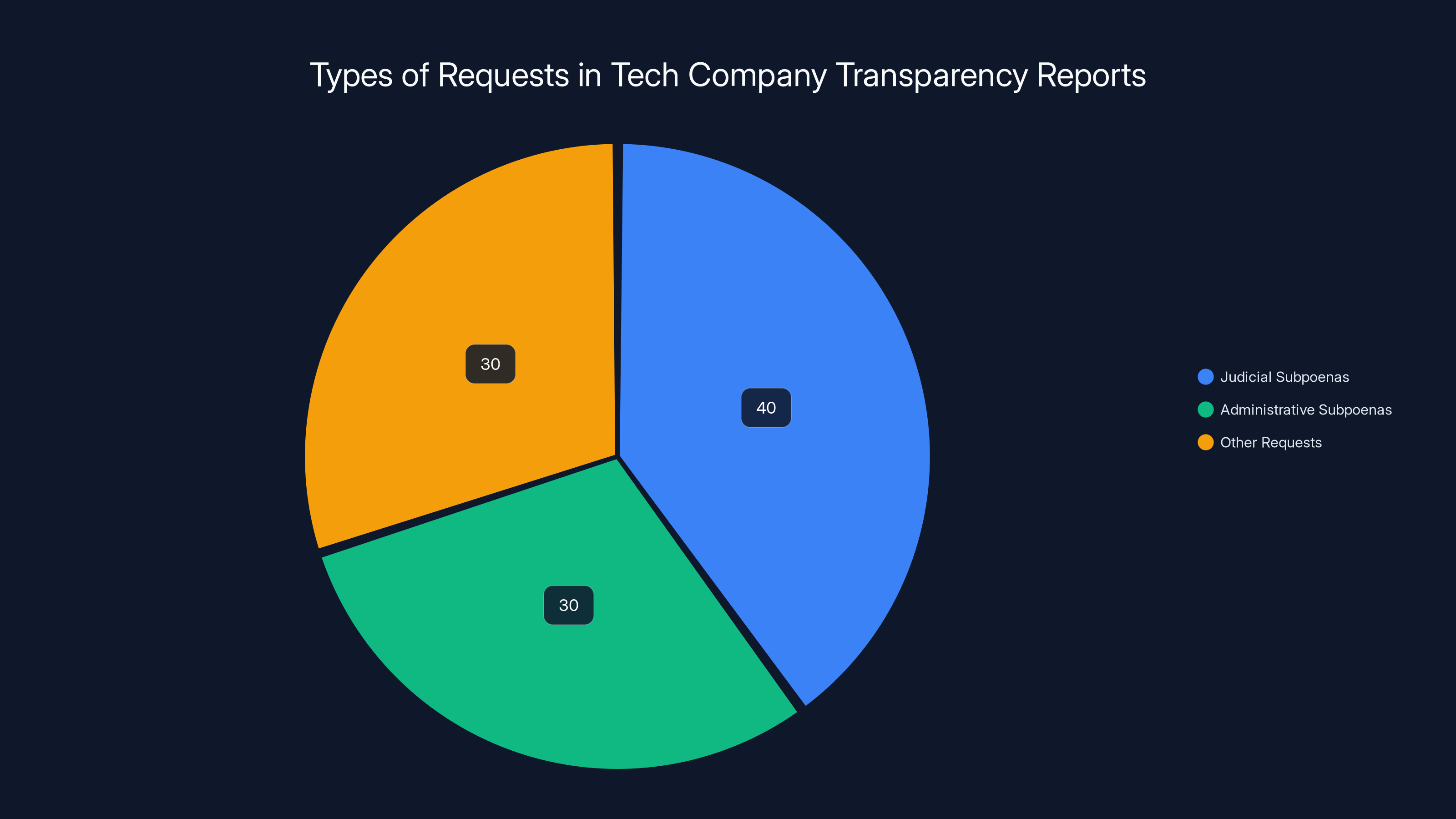

Meta has received hundreds of government demands annually, according to its transparency reports. Google receives thousands. Most companies don't publicly disclose how many of those demands are administrative subpoenas versus judicial ones, making it impossible to know the true scale of this particular surveillance mechanism.

Administrative subpoenas have less oversight and are issued faster than judicial subpoenas, but both have high compliance likelihood due to legal and practical considerations. Estimated data.

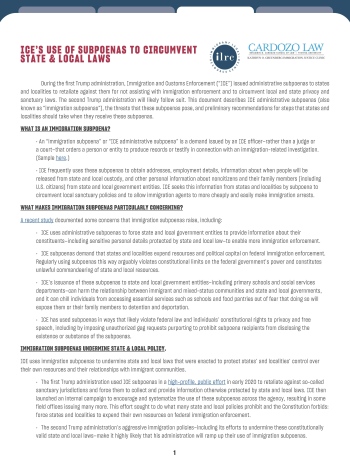

The Recent Wave of Subpoenas Targeting Immigration Activists

The pattern began emerging in late 2024 and has accelerated since. DHS officials have specifically targeted anonymous accounts documenting immigration enforcement activity. The @montcowatch account in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania serves as the clearest example.

That account was created specifically to share information about Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids in the local area. Posts included video recordings of federal agents, information about immigrant rights resources, and updates about detention activities. The account made no secret of its purpose. The bio stated clearly: help protect immigrant rights and due process.

DHS lawyers sent Meta an administrative subpoena claiming someone had tipped them off that ICE agents were being stalked. That claim was never substantiated. The account owner never made threats. Never suggested violence. Simply documented public activity by federal agents.

When the American Civil Liberties Union got involved and threatened legal action, DHS withdrew the subpoena. No explanation. No apology. The subpoena simply vanished.

But @montcowatch wasn't alone. At least four other accounts documenting immigration enforcement also received DHS subpoenas. All were eventually withdrawn after legal pressure. But the fact that DHS made these demands in the first place reveals the scope of the problem.

The justification DHS used across these cases followed a pattern. Claims of stalking. Claims of threats. Claims that seemed designed to sound serious enough to justify a government demand for information, but were either never substantiated or were based on misrepresentations of what the accounts actually did.

What makes this significant is that it demonstrates government officials discovering that administrative subpoenas are an effective tool for identifying critics. Once identified, activists can face additional scrutiny. Their accounts can be suspended. They face potential legal challenges. The chilling effect is real.

One case that drew less attention but may be even more alarming involves a retiree in Florida. This individual had been critical of the Trump administration during its first term. They attended protests, participated in demonstrations, and sent critical emails to government officials. All legal activities. All protected political speech.

This person sent an email to Joseph Dernbach, the lead attorney at DHS's Immigration and Customs Enforcement office. The email was critical. The address was publicly listed. Within hours of sending that email, DHS had requested Google provide all of the retiree's account information through an administrative subpoena.

Google complied. Two weeks later, federal agents showed up at the retiree's home. No arrest. No charges. Just agents asking about the email.

This case suggests something more troubling than targeting activist accounts. It suggests DHS is using administrative subpoenas against individuals who simply criticize government officials directly.

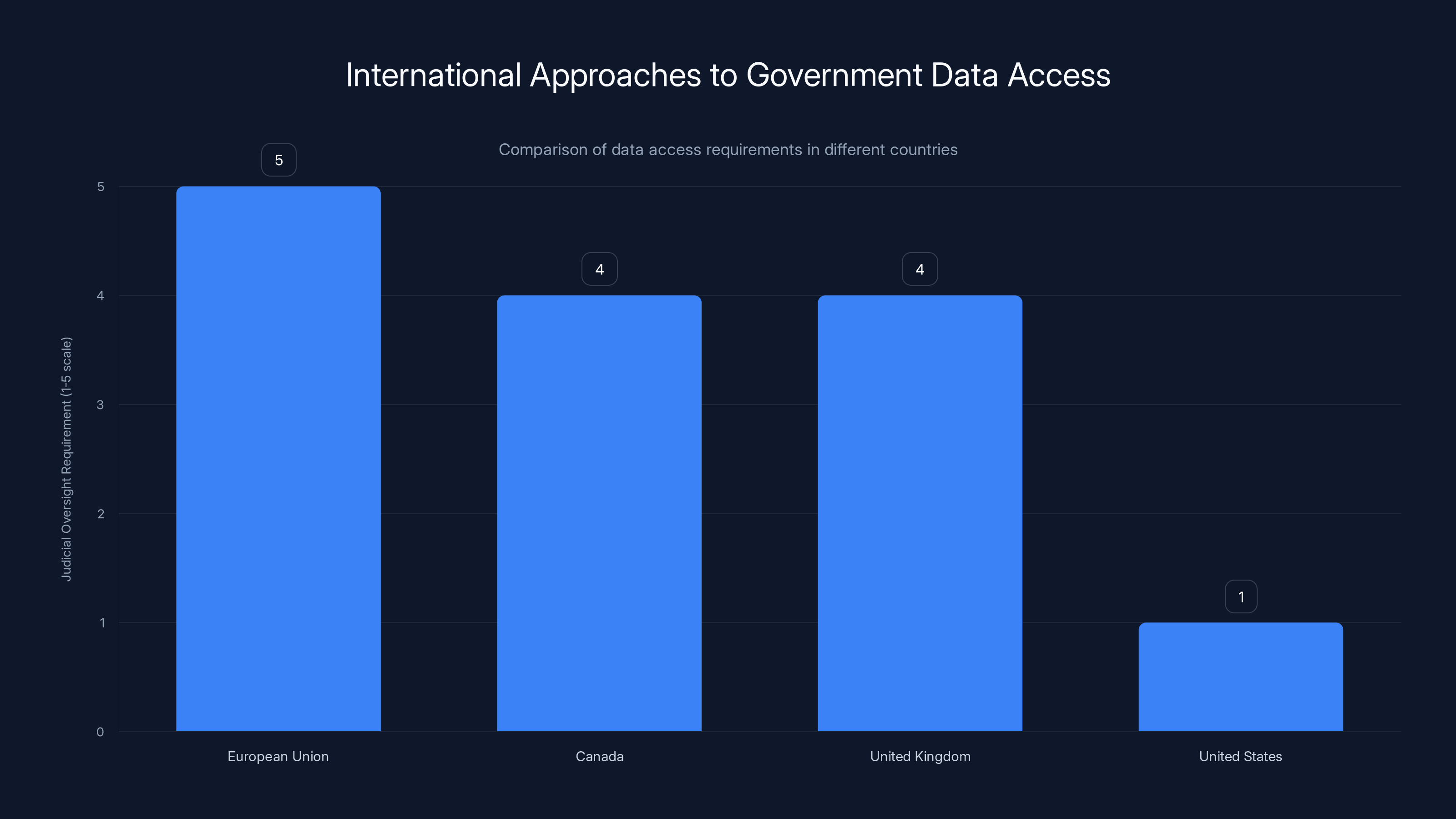

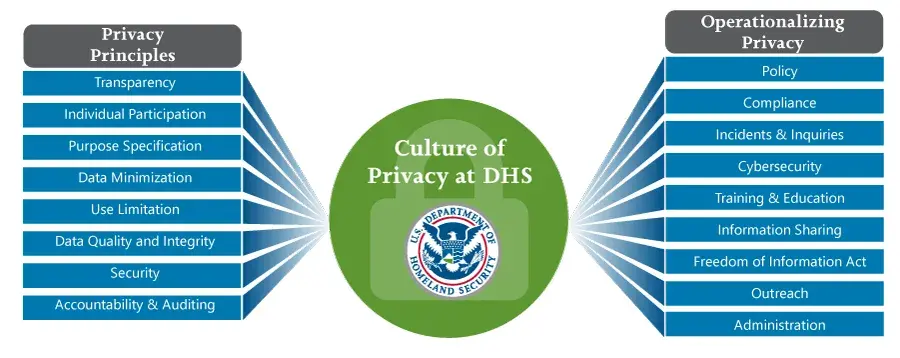

The European Union, Canada, and the United Kingdom have stronger judicial oversight for data access compared to the United States. Estimated data based on narrative.

Why Tech Companies Struggle to Resist These Demands

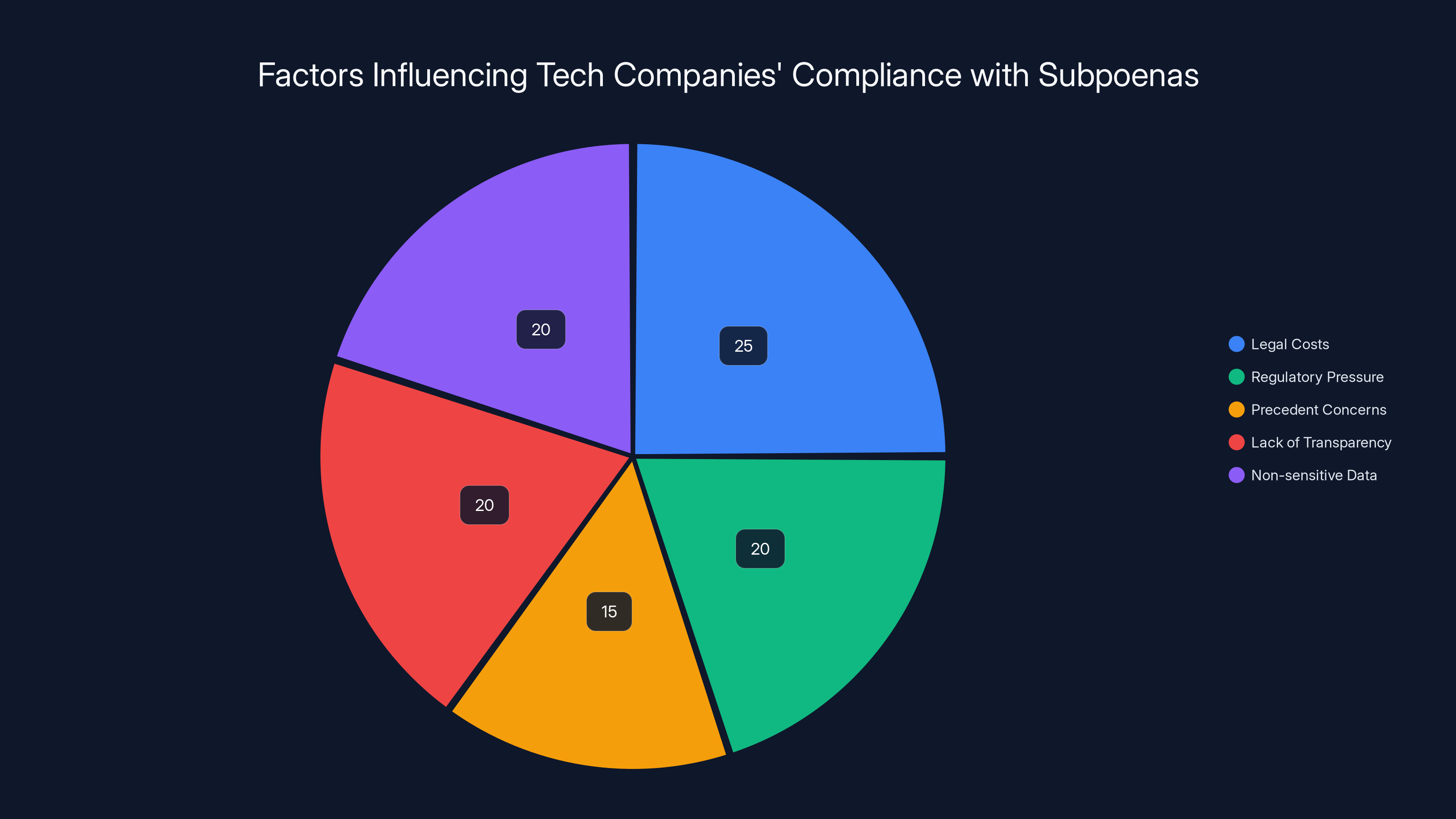

You might wonder why Meta and Google simply don't refuse these requests. If administrative subpoenas lack judicial oversight, can't the companies just say no?

Theoretically, yes. Practically, it's far more complicated.

First, there's the legal ambiguity. While companies can challenge administrative subpoenas, doing so requires litigation. Litigation costs money, time, and resources. Most companies have legal budgets but those budgets aren't infinite. Taking on the federal government in court over every questionable request isn't sustainable.

Second, there's regulatory pressure. Tech companies operate in a complex regulatory environment. They need licenses, approvals, and regulatory goodwill to operate. If a company becomes known as one that regularly refuses government requests, they face pressure in other areas.

Third, there's the precedent issue. Every time a company refuses a request, it potentially sets a precedent. If Meta refuses a DHS subpoena and wins in court, that creates ammunition for future cases. But it also creates a target. Regulatory agencies remember companies that make trouble.

Fourth, most companies simply lack transparency mechanisms for this. Meta's official transparency reports group all types of government requests together. They don't break out administrative subpoenas from other demands. Google does the same. This means users have no way to know if their data was handed over via administrative subpoena versus something else.

Finally, there's a practical reality: many administrative subpoenas are for information the companies probably don't mind disclosing anyway. IP addresses, login times, device information. From a company perspective, this isn't sensitive data like private messages. It's metadata. Metadata feels less important to protect.

But metadata is precisely the information that can unmask anonymous activists.

Meta spokesperson Francis Brennan told journalists the company was asked about @montcowatch but didn't confirm whether they complied with any requests or if they received additional demands about that account in other ways. That non-answer is itself revealing. If Meta had refused the subpoena, they would likely say so. The fact that they won't confirm compliance, combined with the account owner's surprise at learning about the subpoena, suggests Meta handed over the information.

The Legal Framework That Makes This Possible

Administrative subpoena authority isn't new. Congress granted various agencies authority to issue these subpoenas decades ago. The authority makes sense in certain contexts. If you're investigating financial fraud at a bank, you need to access financial records. If you're investigating health violations at a hospital, you need medical records. Administrative subpoenas are faster than going to court every time.

But the statute authorizing DHS to issue administrative subpoenas was written broadly. It allows DHS to demand "any books, records, documents, or other things" relevant to investigations of immigration violations or transportation security violations.

Immigration violations is a broad category. It includes everything from human trafficking to visa fraud to unauthorized entry. But immigration enforcement also encompasses deportation proceedings, detention reviews, and other activities that don't necessarily involve criminal wrongdoing.

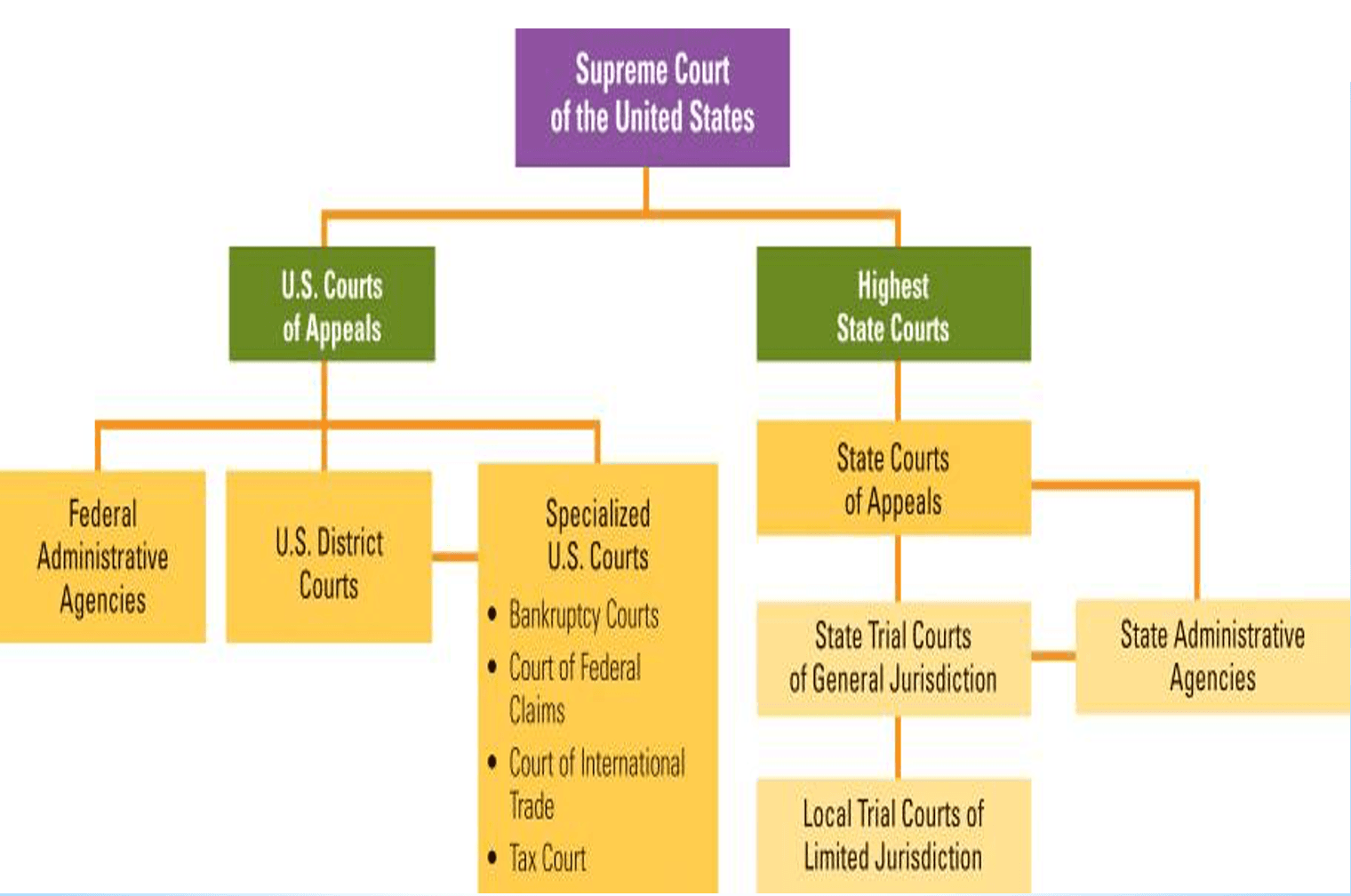

Courts have challenged administrative subpoenas in some cases. The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches, and some courts have argued that demanding personal information without any showing of relevance or reasonable investigation might violate that protection. But Fourth Amendment protections apply to everyone equally. The government's argument that they need metadata to enforce immigration law is hard to overcome in court, even when the subpoena's purpose seems pretextual.

The First Amendment provides stronger protection, theoretically. Targeting someone specifically because of speech they've made should raise constitutional concerns. But the government's response is that they're not targeting speech. They're investigating immigration violations. The speech is just metadata collected incidentally.

This distinction collapses when you look at the actual evidence. DHS wasn't randomly investigating immigration violations and happened to encounter these accounts. DHS specifically sought the identities of people running accounts critical of immigration enforcement. The speech was the reason for the investigation, even if DHS frames it as the jurisdiction.

Some courts have begun recognizing this. When the ACLU challenged the @montcowatch subpoena, the government withdrew it. That withdrawal suggests DHS lawyers knew the legal position was weak if actually litigated.

But withdrawing is different from establishing precedent. One withdrawal in one case doesn't stop the next agency from issuing the next subpoena. Without clear legal restrictions on administrative subpoena abuse, agencies will continue using them.

Estimated data shows that legal costs and regulatory pressure are significant factors influencing tech companies' decisions to comply with administrative subpoenas, alongside concerns about precedent and transparency.

How Your Data Flows Through Government Demands

When DHS sends an administrative subpoena to a tech company, here's what typically happens.

The subpoena arrives at the company's law department. It's official-looking. It cites statutory authority. It lists specific information requested. For a Meta subpoena, it might request all subscriber information for a particular IP address range during specific dates, all email addresses associated with that IP address, all device identifiers, and all account creation information.

The law department flags it for review. Some companies have dedicated teams that review government requests. Others simply forward it to whoever manages that product area. Meta's legal team probably reviewed the @montcowatch subpoena. Google's legal team probably reviewed the Florida retiree's subpoena.

At this stage, the company could challenge it. They could contact the government and ask for a narrower request. They could refuse entirely. Many companies do engage this way on certain requests. But engagement requires time and legal resources. The easier path is compliance.

If the company complies, they gather the requested information. For Meta, this means accessing their systems to find which accounts logged in from specific IP addresses during specific times. Which email addresses were used. Which devices. Which devices were added or changed. All of this metadata is stored in company databases specifically designed to be queryable.

Meta retrieves the data and sends it to DHS. The data includes identifying information. It's not encrypted. It's not anonymized. It's human-readable information that directly identifies the person who owns the account.

DHS then has that information. They can cross-reference the email address with other sources. They can look up the physical address. They can subpoena phone records using that address. They can use the device identifiers to request additional information from device manufacturers. One administrative subpoena becomes the first domino.

Within hours of sending a critical email to the wrong DHS official, a government agency had the name of the Florida retiree. Within days, they had enough information to send agents to his house.

That's how the system works when it functions as intended. And it functions according to its design: quickly, efficiently, and without judicial review.

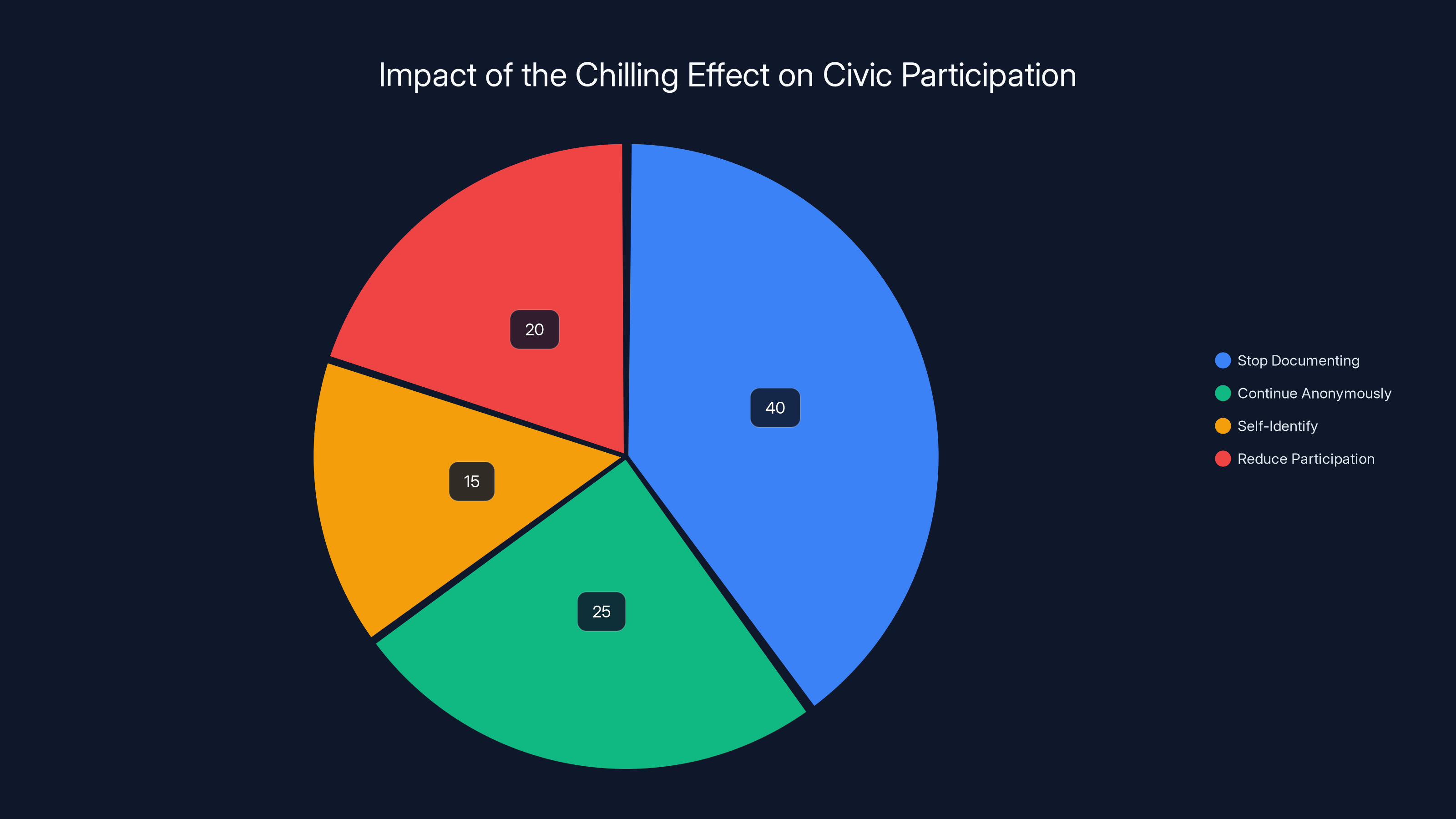

The Chilling Effect on Protected Speech

Civil liberties organizations warn about something called the chilling effect. It's the idea that even if you haven't actually been prosecuted or punished, knowing that you could be creates psychological pressure to self-censor.

Imagine running an anonymous account documenting police or government activity. You believe you're protected by the First Amendment. You think you're engaging in legitimate civic observation. You share videos of public events, information about services, resources for vulnerable populations.

Then you discover that federal agents obtained your personal information without a warrant, without a judge, without any of the normal safeguards. Even if nothing happens next, the knowledge that you can be identified, that your anonymity can be stripped away, that government agents are interested in you personally, changes the calculation.

Do you keep posting? Or do you delete the account? Do you self-identify before the government does? Do you stop documenting what you see?

Most people facing that choice choose to stop. They withdraw from civic participation. They stop documenting. They stop criticizing. They stop participating in ways that might draw government attention.

This is the chilling effect. It doesn't require prosecution. It doesn't require any negative consequence. It just requires the knowledge that identification is possible.

The ACLU specifically warned that the effort to unmask accounts documenting immigration enforcement was "part of a broader strategy to intimidate people who document immigration activity or criticize government actions." That's not speculation. That's describing the actual functional purpose these subpoenas serve.

From the government's perspective, there's efficiency in this. If critics self-censor, enforcement becomes easier. There's less documentation of controversial activities. There's less public awareness of raids or detention. There's less public mobilization against policies.

But from a democratic perspective, this is corrosive. Free speech and free assembly require the ability to criticize government without fear of retaliation. They require the ability to document government activity without fear of identification. They require anonymity to be actually protected, not just theoretically protected by the First Amendment.

When administrative subpoenas can unmask critics in hours, that protection evaporates.

Estimated data shows a balanced distribution of request types in transparency reports, highlighting the need for more detailed breakdowns.

Patterns of Abuse and the Lack of Accountability

The cases that have become public share common characteristics. They all target people engaging in protected speech. They all involve accounts critical of government action. They all use pretextual justifications like stalking claims that aren't substantiated. They all happened to be withdrawn once legal pressure was applied.

The fact that multiple subpoenas were withdrawn suggests the government understood their legal position was weak. If these were legitimate investigations with solid factual bases, DHS would defend them in court. The withdrawals indicate that either the facts didn't support the claims or the legal theory was problematic.

But here's the problem: withdrawing a subpoena in one case doesn't prevent issuing the same subpoena in the next case to a different person. Each incident stands alone. Each requires a separate legal challenge. Each requires activists to hire lawyers, file lawsuits, and fight the government.

This creates asymmetric warfare. The government can issue subpoenas indefinitely. Critics have to fight them indefinitely. Eventually, critics run out of resources or energy. The government's resources are essentially unlimited.

There's also no transparency about what happens to the subpoenas that aren't challenged. If DHS issues five subpoenas and only one is challenged through litigation, the other four become permanent records. The government has the data. Even if it's not used immediately, it's available for future use.

And there's no accountability mechanism. If a DHS official abuses an administrative subpoena, what happens? The subpoena is already issued. The company has already complied. Even if a court later rules the subpoena was improper, the damage is done. The person has been identified. They can't be un-identified.

The individual might sue for damages, but suing the government is complicated. The government has sovereign immunity protections. Even if they win, monetary damages don't undo the identification.

This asymmetry explains why civil liberties organizations have become increasingly alarmed. The system is designed to allow broad government access to information, with limited checks, and minimal accountability for abuse.

How Anonymous Accounts Get Identified

When someone creates an anonymous account on Instagram, they might think they're protected. They use a nickname. They don't provide their real name. They might use a VPN. They might use a different device.

But technical and procedural realities undermine that anonymity.

First, the account creation itself requires an email address. Even if that email address is anonymous, it exists. Someone created it. If DHS gets the email address, they can subpoena the email provider. Gmail, Outlook, Yahoo, Proton Mail. They can demand to know which phone number or alternate email was used to create it. That creates a chain.

Second, accounts leave metadata everywhere. Every time someone logs in, the platform records an IP address. The IP address is registered to an internet service provider. If the person logs in from home, the ISP can identify which customer that IP address belongs to. If they log in from work or a coffee shop, the IP address eventually traces back to the place.

Third, devices have identifiers. Phones have Android IDs or Apple IDs. Computers have MAC addresses. Browsers have fingerprints. Instagram can collect this data. When multiple accounts log in from the same device, or the same device switches between accounts, patterns emerge.

Fourth, behavior creates patterns. An account might post at specific times. Use specific language. Reference specific locations. Engage with specific communities. This behavioral metadata can help identify someone by cross-referencing with other data sources.

Fifth, one data point leads to another. Once DHS has a phone number from an email provider, they can subpoena the phone company for call records and location data. Once they have a physical address from an internet service provider, they can subpoena neighbors or local businesses for information. Once they have a name, they can pull driver's license records, voter registration, property records, and dozens of other data sources.

The initial administrative subpoena to Meta isn't the end of the chain. It's the beginning. Once one piece of information is obtained, that piece becomes the justification for obtaining other information.

This is why the Florida retiree received agents at his door within two weeks of sending a critical email. The administrative subpoena to Google was just the first step. Everything that followed was technically legal because each subsequent request was based on information gathered through the previous request.

Judicial subpoenas have a broader scope and require judicial oversight, while administrative subpoenas have a narrower focus and are issued directly by agencies. Estimated data.

The Role of Tech Company Transparency Reports

Meta publishes a transparency report twice yearly. Google does the same. These reports detail how many requests the companies receive from government agencies. But they lump all requests together. They don't break out administrative subpoenas separately from judicial subpoenas or other types of demands.

This is a strategic choice. The transparency is real but deliberately limited. Users can see that Meta receives thousands of requests from DHS. They can't see how many of those are administrative subpoenas that bypass judicial oversight.

If Meta were transparent about administrative subpoena specifically, users would have much clearer data about surveillance. They would know that a particular agency regularly makes demands for user information without judicial review. They would understand which agencies are most aggressive in seeking data.

Some researchers have tried to parse the transparency reports to identify patterns, but the information is too aggregated to be useful. The reports serve as PR documents that say we're transparent without actually being transparent about the most problematic requests.

Google has been marginally better on some points. They've published occasional special reports on specific government agencies or specific types of requests. But even Google's transparency is limited. Neither company discloses what happens after they comply with a request. They don't say if the person whose data was requested was ever notified. They don't say if the person was targeted for further investigation. They don't track whether the information was actually related to the stated purpose of the request.

Meaningful transparency would require companies to disclose administrative subpoena requests separately, to challenge questionable requests more consistently, and to notify users when their information is requested through means that lack judicial oversight.

None of this happens currently.

Constitutional Concerns and Legal Challenges

The First Amendment protects political speech, even critical speech, even anonymous political speech. The Supreme Court has held that anonymous speech is protected. Citizens have a right to engage in political activity without identifying themselves.

The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. Demanding information about a person's online activity arguably implicates Fourth Amendment protections.

But courts have been inconsistent in applying these protections to metadata. They've treated IP addresses and login times as less sensitive than the content of communications. They've allowed law enforcement broad access to metadata in criminal investigations.

Administrative subpoenas exist in this gray area. They're not searches in the traditional Fourth Amendment sense because they target information held by third parties. The government isn't physically invading someone's space. They're just asking a company for information.

But courts have increasingly recognized that metadata can be as revealing as content. Knowing every place someone went, everyone they communicated with, and every website they visited is as intrusive as reading their diary.

Some federal courts have begun imposing limits on administrative subpoenas. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers New York and surrounding areas, has ruled that administrative subpoenas must have some reasonable connection to the stated investigation. They can't be completely divorced from the agency's actual work.

But the Second Circuit's ruling doesn't apply nationwide. Other circuits haven't adopted the same reasoning. And even where the reasoning exists, enforcement is spotty. Federal agencies regularly issue questionable subpoenas and banks on companies either complying or backing down.

The constitutional questions aren't clearly resolved. Is an administrative subpoena targeting someone purely because of their speech a First Amendment violation? Courts haven't definitively said. Is using administrative subpoenas as a surveillance tool to identify critics an abuse of government power? Courts haven't established clear limits.

This uncertainty is part of the problem. The government knows the law is unsettled. They can push boundaries because the consequences of overreach aren't clearly defined.

Estimated data suggests that the majority of individuals experiencing the chilling effect choose to stop documenting activities, with others opting to reduce participation or continue anonymously.

International Comparisons and Different Approaches

Other democracies have grappled with similar questions about government access to user data. Their approaches vary.

The European Union treats this differently. The General Data Protection Regulation limits how companies can share user data. It requires that companies not hand over data except through legal processes. Law enforcement requests must follow specific procedures with requirements for demonstrating necessity and proportionality.

Companies in Europe that comply with demands for user information without proper legal process can face massive fines. This creates incentives for companies to push back on questionable requests.

Canada requires warrants for most user information beyond basic subscriber data. The government can't simply demand IP addresses or login records without judicial authorization. This is closer to requiring a warrant than an administrative subpoena.

The United Kingdom uses a process that requires a specific order from a judge even for metadata requests. Companies must demonstrate to a court that they have legitimate reasons for seeking someone's data.

These aren't perfect systems. Privacy advocates in these countries have their own concerns. But they all share a common principle: before the government gets access to user data, some neutral decision-maker should review the request and confirm it's reasonable.

The United States lacks this mechanism for administrative subpoenas. An agency can simply demand information without any judicial review.

Some privacy advocates argue the U. S. should adopt something closer to the European or Canadian model. Require judicial authorization for metadata requests that could reveal online activity. Make it harder for agencies to unmask anonymous speakers. Create real penalties for agencies that abuse subpoena power.

But implementing these changes would require Congress to pass legislation limiting agency authority. And agencies are understandably reluctant to have their authority limited.

What Activism and Journalism Community Are Doing in Response

The American Civil Liberties Union has become the primary advocate pushing back against administrative subpoena abuse. The ACLU represents account owners whose data was targeted. They've filed lawsuits. They've sent warning letters to government agencies.

Journalist organizations have also gotten involved. If DHS is using administrative subpoenas to identify journalists, that raises press freedom concerns. Several journalism organizations have filed friend-of-the-court briefs in cases challenging subpoena authority.

Some tech advocacy organizations are pushing companies to be more transparent and more resistant to questionable requests. Organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation have published analysis of the subpoena issue and called for companies to create notification systems that inform users when their data is requested.

Activist networks have begun sharing information about how to better protect anonymity. Using VPNs. Using temporary email addresses. Varying login times and devices. These are imperfect workarounds because determined government agencies can overcome them, but they raise the bar somewhat.

Some platforms are beginning to respond. Signal, the encrypted messaging app, has redesigned their systems to minimize the data they could be compelled to hand over. They don't store who messages whom. They don't log IP addresses. They retain only the absolute minimum information needed to operate.

Matrix Chat and other decentralized messaging platforms are taking similar approaches. The idea is that if the information doesn't exist, it can't be subpoenaed.

But these are niche solutions. Most people still use mainstream platforms that collect extensive metadata and are vulnerable to government demands.

The Broader Implications for Privacy and Dissent

The administrative subpoena issue is part of a larger picture of digital surveillance. Government agencies have expanded their capacity to track, identify, and monitor people in ways that previous generations would have found dystopian.

Mobile phones track location. Internet service providers track browsing. Social media platforms track social connections. Email providers track communications. All of this data exists. All of it is vulnerable to government access.

Administrative subpoenas are just one tool in a larger surveillance toolkit. But they're significant because they represent surveillance that bypasses the normal judicial checks that apply to other forms of government investigation.

The implications are serious for dissidents, activists, and anyone who engages in political speech that might displease government officials. Anonymity, which was previously protected by technological limitations, can now be stripped away through legal process that requires no judicial authorization.

This changes the calculus of political participation. It makes people hesitant to express criticism. It makes people nervous about documenting government activity. It discourages participation in ways that might draw attention.

Over time, this chilling effect accumulates. Fewer people engage in forms of speech that might be controversial. Government policies face less documentation and less public criticism. The level of public resistance to unpopular policies decreases.

This might not be the explicit intent of every administrative subpoena. Some might be issued for legitimate law enforcement reasons. But the cumulative effect is the same: a system where dissent is riskier, anonymity is less protected, and government officials can identify critics without judicial review.

Protecting Yourself in This Environment

For people wanting to maintain anonymity while engaging in speech that might draw government attention, the options are limited but not nonexistent.

First, use email services that prioritize privacy. Proton Mail, Tutanota, and similar services use encryption and don't maintain extensive user data. They're more resistant to government demands than standard email providers.

Second, use VPNs consistently. A VPN masks your IP address. When you log into an account through a VPN, the platform sees the VPN's address, not yours. This makes tracking more difficult, though determined law enforcement can potentially uncover VPN connections.

Third, vary your behavior patterns. If you always log in at the same time from the same device, that creates a distinct pattern. Varying when you log in, from which devices, and from different locations makes pattern matching harder.

Fourth, compartmentalize accounts. Don't use the same device for anonymous accounts and identified accounts. Don't use the same email. Don't use the same locations. Create actual separation between different online identities.

Fifth, stay informed about subpoena trends. Organizations like the ACLU and EFF publish information about government demands for data. Knowing which agencies are actively seeking information helps you understand the risk environment.

Sixth, use platforms and services designed for privacy. Decentralized messaging apps, encrypted messaging, platforms that minimize data retention. Services like Signal are designed specifically to limit the data available to be subpoenaed.

Seventh, understand your rights. If the government requests information about you, you have rights. You can challenge requests. You can demand judicial review in some cases. Knowing your options is crucial.

But understand the limitations here. These protections help, but they're not foolproof. A determined government agency with resources can potentially overcome most privacy measures. The goal is not to achieve perfect anonymity, which is probably impossible against a resourceful adversary. The goal is to raise the bar high enough that authorities need actual evidence of wrongdoing before investigating, rather than being able to unmask critics effortlessly.

The Legislative Landscape and Potential Reforms

Several legislative proposals have attempted to address administrative subpoena abuse. None have become law yet.

One proposal would require administrative subpoenas to be approved by a judge before being served. This would essentially require judicial oversight of administrative subpoenas, converting them into something closer to traditional warrants. The proposal has support from civil liberties organizations but opposition from law enforcement and federal agencies.

Another proposal would require companies to notify individuals when their data is sought through subpoenas. The logic is that if people knew the government was seeking information about them, they could challenge it through legal means. Currently, many people never learn that their data was requested.

A third proposal would require federal agencies to maintain records of administrative subpoena requests and publish statistics about them. This would create transparency. Agencies would have to disclose which agencies are issuing subpoenas, how many they're issuing, and whether they're being challenged or withdrawn.

A fourth proposal would limit the types of information that can be obtained through administrative subpoena. Currently, DHS can demand essentially any subscriber information. The proposal would limit them to bare minimum identifying information unless they can show to a judge that additional information is necessary.

These proposals face opposition. Federal agencies argue that imposing these restrictions would hamper investigations. They claim efficiency would be reduced if they have to go to judges before issuing subpoenas. They argue that companies shouldn't be required to notify people because that could obstruct investigations.

From the agencies' perspective, administrative subpoenas are convenient tools. They're fast. They don't require judicial approval. They frequently result in compliance. Restricting them would require agencies to change their practices.

But from a civil liberties perspective, that inconvenience is precisely the point. If the government needs to justify its information requests to a judge, fewer questionable requests will be made. If the bar is higher, government officials will think more carefully before seeking someone's information.

It's unclear if any of these proposals will become law. They require Congressional action, and Congress has other priorities. Agencies actively lobby against restrictions on their authority. Without significant public pressure or catastrophic abuse becoming widely known, legislative change is unlikely.

What the Tech Companies Should Do Differently

Tech companies are not passive bystanders in this system. They make choices about how to respond to government requests.

Meta could commit to challenging administrative subpoenas more aggressively. Instead of complying by default, they could ask the government to demonstrate the subpoena is reasonable and related to actual investigation. This wouldn't necessarily result in refusing all subpoenas, but it would require the government to justify them.

Google could commit to greater transparency about administrative subpoenas specifically. Break out administrative subpoenas separately in transparency reports so users understand the scale of this type of demand.

Both companies could establish notification systems. When a government agency requests information about a specific user, the company could notify the user (unless the government specifically requests non-notification, in which case the notification would be delayed). This would give users the opportunity to challenge requests legally.

Companies could commit to pushing back on demands for information clearly unrelated to the stated purpose. When a subpoena ostensibly seeking information about immigration violations is clearly seeking information to identify political critics, the company could refuse and invite the government to get judicial authorization if they believe they're entitled to the information.

Companies could also build their systems to minimize the data available to be subpoenaed. If they didn't store extensive metadata, there would be less information available for agencies to demand. This isn't the current trend. Companies are moving in the opposite direction, storing more data than ever.

These changes would face pressure. The government would complain. Law enforcement would argue these changes interfere with legitimate investigations. But companies have power here. They could establish that compliance with subpoenas comes with conditions.

The Precedent Set by Administrative Subpoena Abuse

What's most troubling about the recent administrative subpoena cases is the precedent they establish. If government agencies can successfully unmask activist accounts, that becomes the new normal. The next agency that wants to identify critics will think it's acceptable.

Precedent exists in two directions. If courts consistently rule against agencies and establish that administrative subpoenas can't be used to target speech, that creates a protective precedent. If courts remain silent and agencies successfully identify activists without legal consequences, that creates a dangerous precedent.

Currently, the cases that have been won were won through litigation, with organizations like the ACLU representing plaintiffs. But those litigation victories only protect the specific plaintiffs in the specific cases. They don't create binding precedent that constrains other agencies.

What's needed is either judicial precedent that clearly restricts administrative subpoena authority or legislative action that imposes restrictions. Without one or both, agencies will continue testing boundaries.

The cases we know about are just the ones that were litigated. For every account owner who hired a lawyer and fought back, there might be ten others whose data was obtained quietly, who were never even informed, and who don't know they were targeted.

The precedent being set is one where anonymous activism is riskier, where critics can be identified without judicial approval, and where government surveillance of political opponents is routine and largely unaccountable.

FAQ

What is an administrative subpoena?

An administrative subpoena is a demand for information issued directly by a federal agency without requiring approval from a judge or court. Unlike judicial subpoenas that require a judge to authorize the request after reviewing evidence, administrative subpoenas are issued unilaterally by government agencies based on their own authority. While they cannot demand email contents or location data, they can request subscriber information like names, addresses, IP addresses, email addresses, login times, and device identifiers.

How do administrative subpoenas differ from judicial subpoenas?

Judicial subpoenas require a judge to review the request and confirm it's reasonable and connected to a legitimate investigation before the subpoena is issued. This judicial review creates a check on government power. Administrative subpoenas skip this step entirely. The agency simply issues the subpoena using authority granted by statute. No judge reviews the request. No neutral third party confirms whether the demand is proportional or reasonable. This difference is significant because it allows agencies to seek information much faster and with less oversight.

Can tech companies refuse to comply with administrative subpoenas?

Tech companies can technically refuse to comply with administrative subpoenas, but most don't. Unlike judicial subpoenas which companies must generally comply with, administrative subpoenas create legal ambiguity. Companies could challenge them, but challenging requires litigation and legal resources. Most companies find it easier to comply than to fight the government. The lack of a clear legal requirement to refuse, combined with practical costs of litigation, means companies usually hand over the requested information when agencies demand it.

How does an administrative subpoena lead to someone's identification?

One administrative subpoena sets a chain reaction in motion. When a company provides an IP address, that IP address can be traced to an internet service provider, which can identify the customer. When a company provides an email address, that email address can be traced to the email provider to get phone numbers or alternate contact information. When one piece of information is obtained, that becomes the basis for obtaining additional information through more subpoenas. The initial administrative subpoena to a social media platform frequently leads to multiple additional subpoenas to other companies, eventually revealing a person's identity.

What information can administrative subpoenas demand?

Administrative subpoenas cannot demand the contents of emails, messages, or other communications. They also cannot demand location data. But they can demand subscriber information including names, physical addresses, phone numbers, email addresses associated with accounts, account creation dates and times, login times and dates, IP addresses used to access accounts, device identifiers, payment information, and any other identifying information linked to an account. For anonymous accounts, this metadata is often sufficient to identify the person behind the anonymity.

Why are administrative subpoenas concerning for anonymous activists and critics?

Administrative subpoenas undermine the ability to engage in anonymous political speech and activism. While the First Amendment protects anonymous speech, administrative subpoenas allow the government to unmask anonymous speakers without judicial review. This creates a chilling effect where people become hesitant to engage in anonymous criticism or documentation because they know the government can identify them without a judge's approval. The lack of oversight means agencies can use these subpoenas to target critics rather than investigate actual crimes, and many accounts are only unmasked because of people's speech, not evidence of wrongdoing.

Has there been court action on administrative subpoena cases?

Several administrative subpoena cases have been challenged in court, particularly those seeking to identify accounts documenting immigration enforcement. When legal action was taken, agencies typically withdrew the subpoenas rather than defending them in court. This suggests the legal position supporting the subpoenas was weak. However, withdrawing in individual cases doesn't establish precedent that constrains future subpoenas. Each case must be challenged separately, and without binding court rulings, agencies continue issuing subpoenas to other targets.

What can individuals do to protect their anonymity online?

While perfect protection against determined government agencies is unlikely, several measures can make identification harder. Use privacy-focused email services like Proton Mail that don't maintain extensive user data. Use VPNs consistently when accessing anonymous accounts so platforms see the VPN address rather than your IP address. Vary your behavior patterns by logging in at different times, from different devices, and from different locations. Compartmentalize accounts by not using the same email or device for anonymous accounts and identified accounts. Use platforms designed for privacy like Signal for communications. Stay informed about government demand patterns. And understand your legal rights if government requests information about you.

What do tech companies publish in their transparency reports about government requests?

Tech companies like Meta and Google publish transparency reports showing the total number of government requests they receive. However, these reports aggregate all types of government demands without breaking out administrative subpoenas separately. This obscures the scale of administrative subpoena use. Companies don't disclose which agencies make the most demands, whether requests were challenged, or whether users were notified when their data was requested. This limited transparency prevents the public from understanding the extent to which administrative subpoenas are used compared to other request types, making companies' transparency claims less meaningful than they initially appear.

What legislative proposals exist to address administrative subpoena abuse?

Several proposals have been introduced to address administrative subpoena concerns. One would require judicial approval before agencies can issue administrative subpoenas, essentially converting them to warrant-like documents. Another would require companies to notify individuals when their data is sought through subpoenas so they can challenge the requests. A third would require agencies to maintain and publish statistics about administrative subpoena requests. A fourth would limit what information can be obtained through administrative subpoena without additional judicial authorization. These proposals face opposition from federal agencies and law enforcement who argue the restrictions would hamper investigations. Without significant public pressure or legislative action, these reforms are unlikely to become law.

Key Takeaways

- Administrative subpoenas allow federal agencies to demand user data without judicial review, unlike traditional warrants that require court approval

- Recent cases show DHS using administrative subpoenas to unmask accounts documenting immigration enforcement and criticizing government policies

- A single administrative subpoena triggers a chain reaction of additional requests that ultimately reveals an activist's identity

- Tech companies rarely challenge administrative subpoenas, treating metadata requests as routine rather than privacy-threatening

- The lack of transparency in government demand disclosures means the true scale of administrative subpoena abuse remains unknown

Related Articles

- Facial Recognition and Government Surveillance: The Global Entry Revocation Story [2025]

- How to Film ICE & CBP Agents Legally and Safely [2025]

- France's VPN Ban for Under-15s: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Face Recognition Surveillance: How ICE Deploys Facial ID Technology [2025]

- India's Supreme Court vs WhatsApp: Privacy Rights Under Fire [2025]

- France's VPN Ban for Minors: Digital Control or Privacy Destruction [2025]

![How DHS Uses Administrative Subpoenas to Target Critics [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-dhs-uses-administrative-subpoenas-to-target-critics-2025/image-1-1770145617141.jpg)