CISA Retires 10 Emergency Directives: What Changed for Federal Cybersecurity [2025]

Introduction: A Milestone in Federal Cybersecurity Evolution

Something significant just happened in the federal cybersecurity world, and you might've missed it. The US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency announced it's retiring ten Emergency Directives all at once. That's the largest simultaneous retirement in CISA's history, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

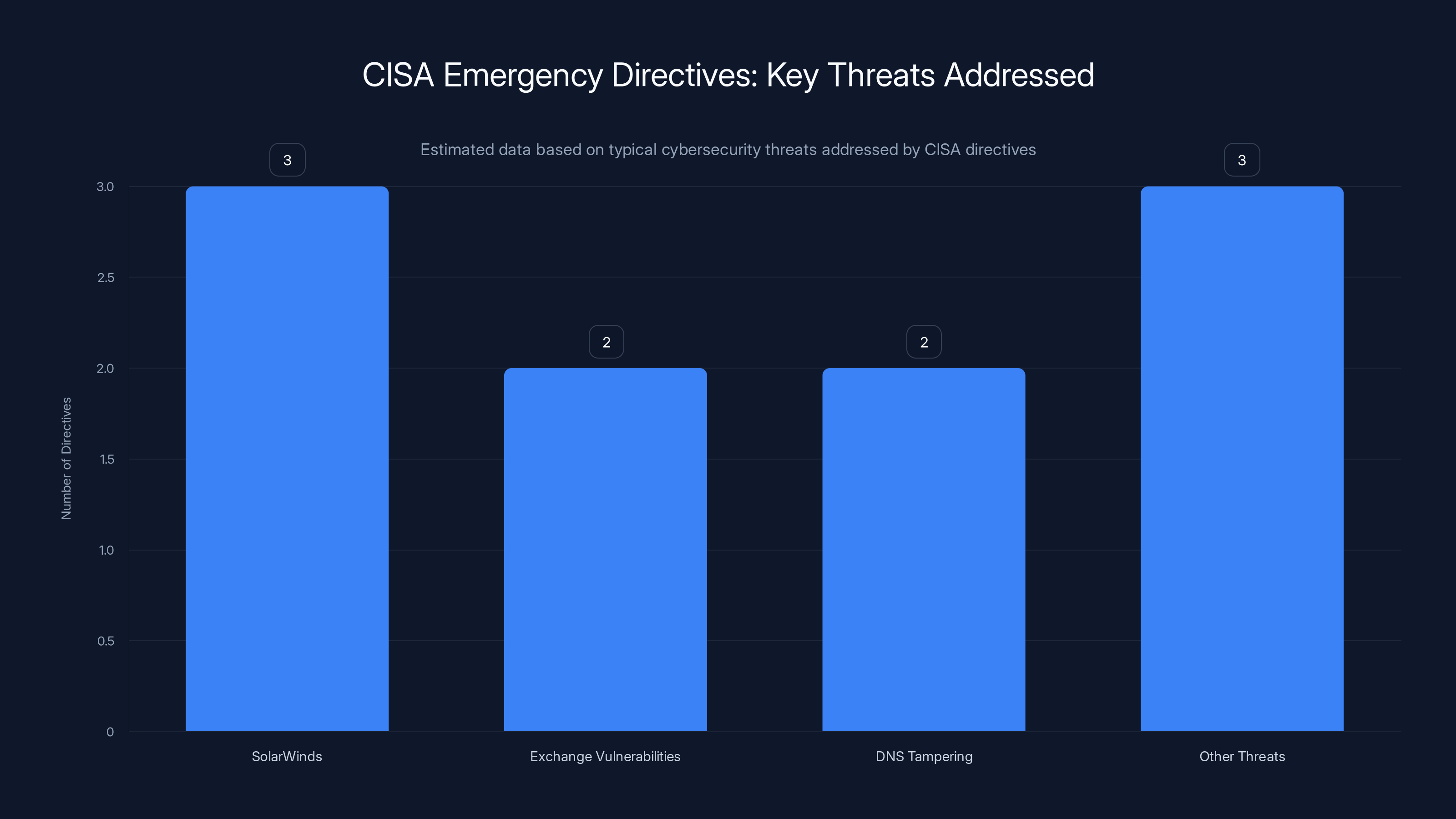

Now, here's the thing—this isn't a step backward. It's actually the opposite. These directives served their purpose. They were emergency orders issued between 2019 and 2024 to address immediate, critical threats such as DNS tampering, Windows vulnerabilities, the Solar Winds supply chain attack, and Microsoft Exchange zero-days. Each one demanded swift action, as detailed in The Hacker News.

But emergency measures aren't meant to last forever. They're designed to buy time while more permanent solutions get built. And that's exactly what happened. Over the past few years, CISA created something better: Binding Operational Directive 22-01 (BOD 22-01), a comprehensive framework for managing known exploited vulnerabilities across all federal agencies, as explained in the NCUA's annual report.

The retirement of these ten directives sends a clear message. Federal cybersecurity is maturing. Instead of reactive emergency orders every time a new zero-day drops, agencies now have a systematic process for identifying, prioritizing, and patching the vulnerabilities that actually matter, according to CISA's official directives.

But what does this mean for you, your organization, and the broader cybersecurity landscape? Let's dig in.

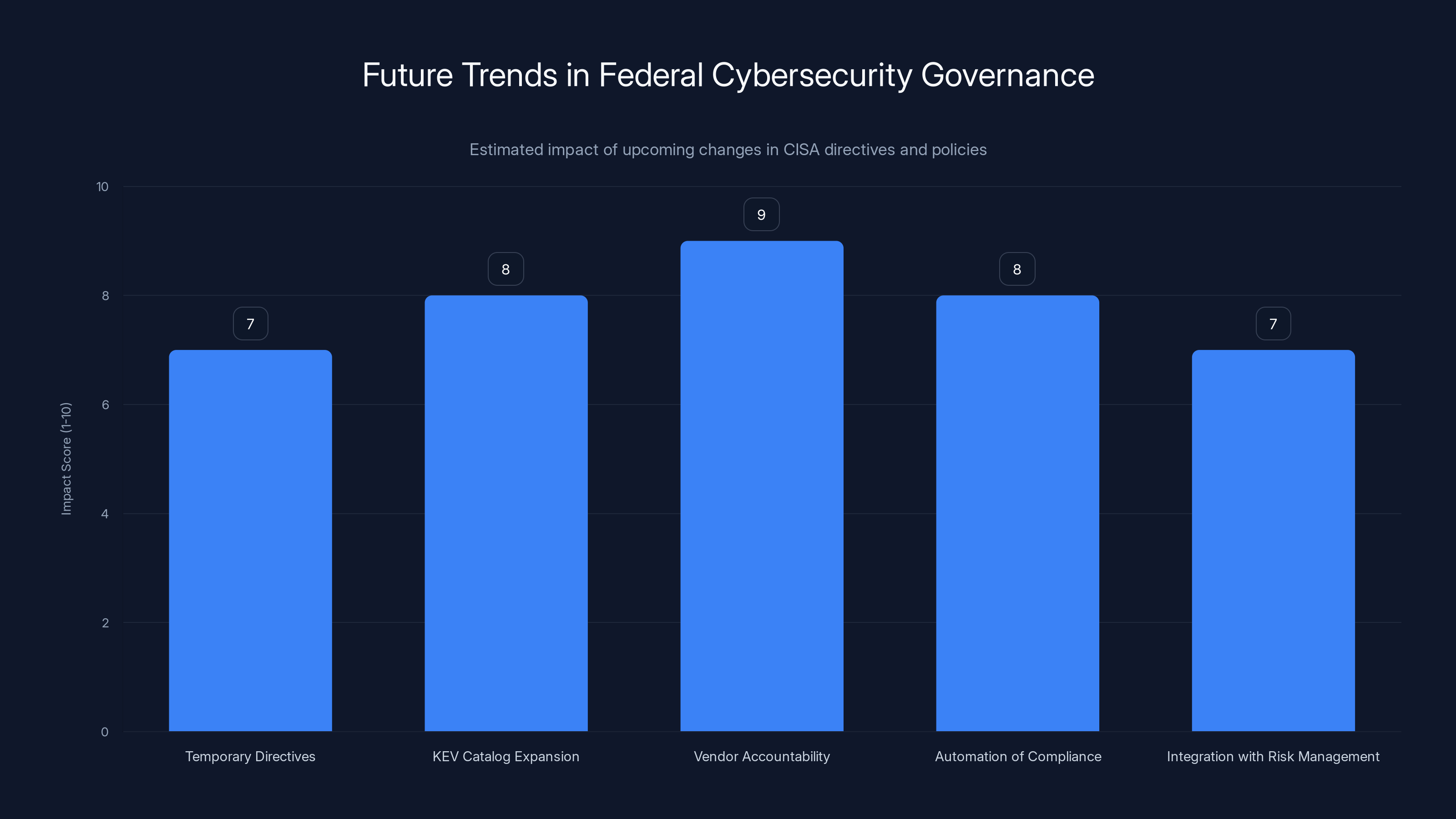

The future of federal cybersecurity governance will see significant impacts from increased vendor accountability and expanded KEV catalog coverage, with automation and integration into broader risk management frameworks also playing key roles. (Estimated data)

TL; DR

- CISA retired 10 emergency directives between 2019 and 2024, the largest simultaneous retirement in agency history, as reported by Industrial Cyber.

- BOD 22-01 replaced them with a comprehensive framework requiring federal agencies to patch known exploited vulnerabilities within strict deadlines, according to NCUA's report.

- This reflects Secure by Design principles, shifting from reactive emergency responses to proactive vulnerability management, as noted by LinkedIn Pulse.

- Federal agencies now have standardized timelines for patching critical vulnerabilities instead of emergency directives, as highlighted by The Hacker News.

- The move signals maturity in federal cybersecurity governance, though it requires sustained compliance efforts, as discussed by Industrial Cyber.

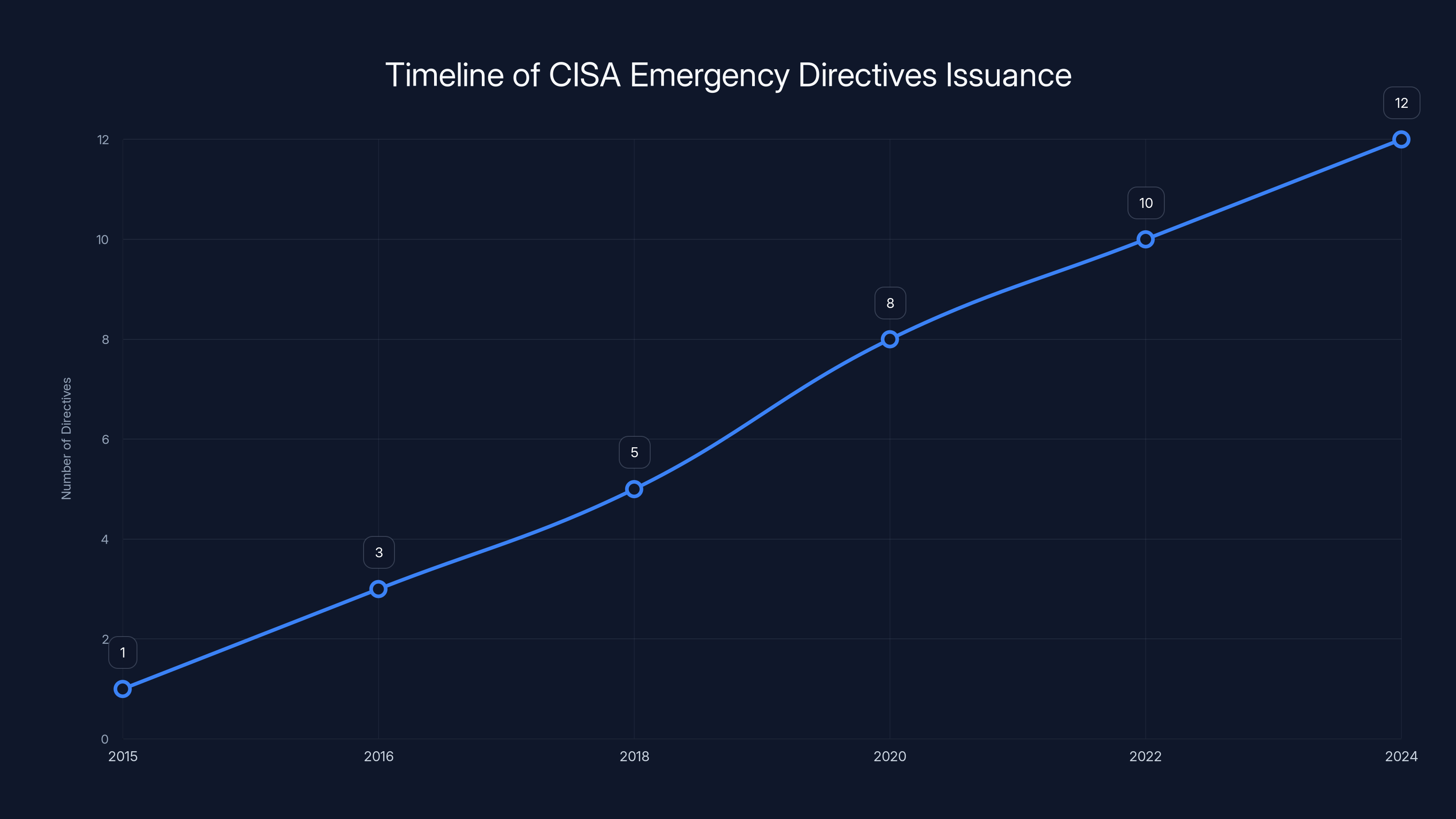

The issuance of Emergency Directives by CISA increased over time, reflecting growing cybersecurity challenges. Estimated data based on typical trends.

What Are Emergency Directives? Understanding CISA's Most Powerful Tool

Let me start with basics, because this matters. Emergency Directives are CISA's nuclear option for cybersecurity. When CISA issues an ED, it's not a suggestion. It's a mandatory order for all Federal Civilian Executive Branch agencies, as explained in CISA's official directives.

Think of regular cybersecurity guidance as recommendations. "Here's a best practice. Consider implementing it." Emergency Directives are different. They say, "Do this now. Verify compliance within 24 to 72 hours. Report back to us."

CISA created this tool because the traditional pace of cybersecurity governance moves too slowly. A vulnerability gets discovered. It enters the normal advisory process. Agencies discuss it, plan implementation, allocate budget. By the time action happens, the exploit is already in the wild.

Emergency Directives short-circuit that process. When CISA identifies a threat significant enough, it bypasses normal channels and issues a direct order, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

But here's the catch—and this is important—Emergency Directives are exhausting to maintain. Each one requires specific compliance tracking, separate reporting mechanisms, and continuous monitoring. Agencies have to manage multiple overlapping directives, each with different deadlines, different vulnerability catalogs, and different remediation requirements, as highlighted by NCUA's report.

For CISA, maintaining dozens of active directives meant constant resource allocation just to track compliance. For agencies, it meant fragmented vulnerability management programs. Nobody wanted this permanently. It was always meant to be temporary.

That temporary measure lasted up to five years for some of these directives. By 2024, CISA had built something better, as discussed in The Hacker News.

The Ten Retired Directives: What They Protected Against

Let's look at what just got retired. Each directive was a response to a specific, major threat. Understanding what they protected against helps you understand the vulnerability landscape they were managing.

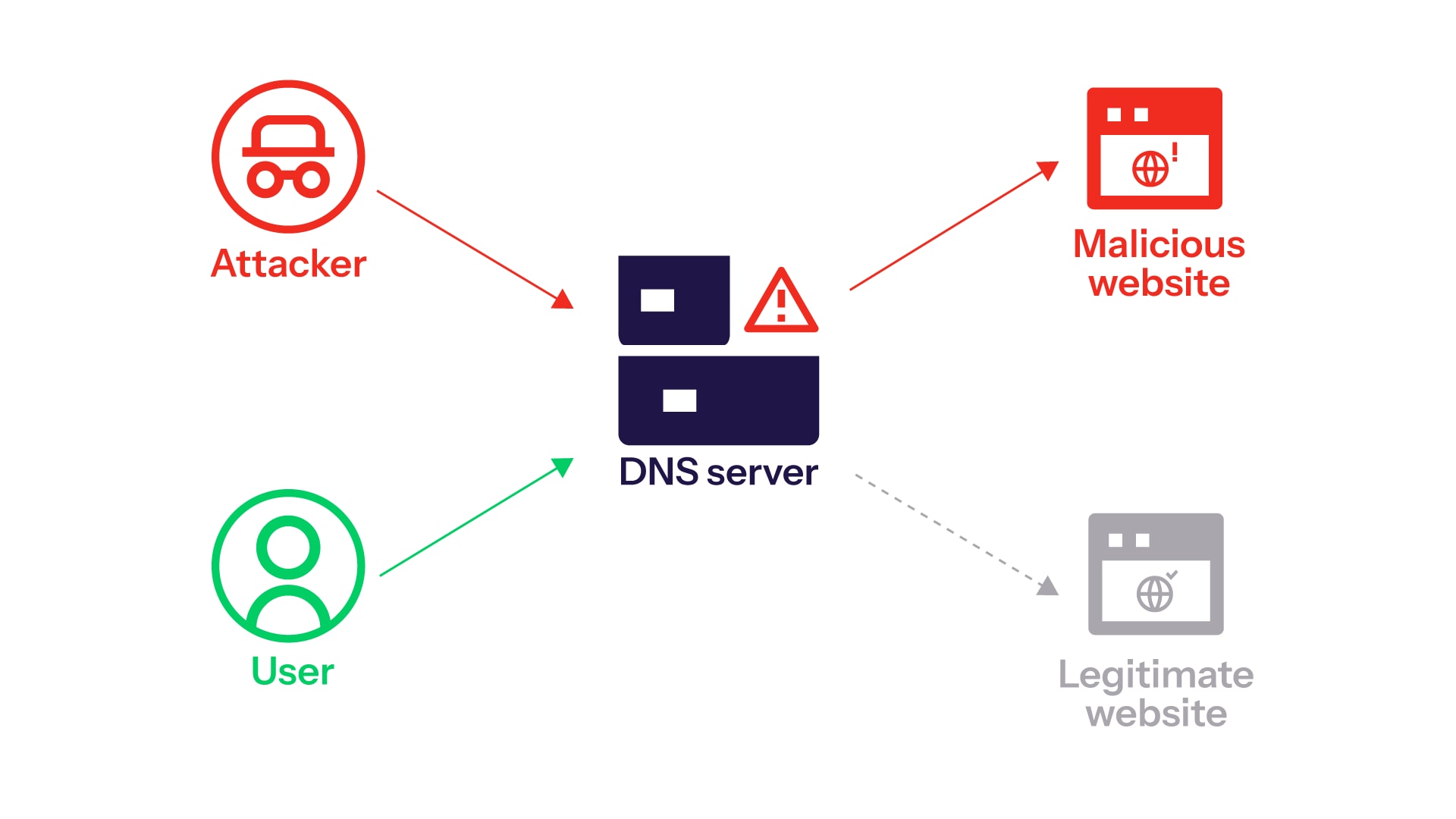

ED 19-01: Mitigating DNS Infrastructure Tampering

DNS is the internet's address book. If you compromise DNS, you can redirect traffic anywhere. ED 19-01 required federal agencies to implement DNS security measures across their infrastructure, as explained by CISA's official directives.

The threat was real. Advanced persistent threat actors were tampering with DNS responses, redirecting agency traffic to malicious servers. This wasn't a sophisticated exploit requiring zero-days. It was elegant and devastating in its simplicity.

Agencies had to deploy DNSSEC, implement DNS filtering, and monitor for tampering. This directive alone pushed hundreds of federal systems to modernize their DNS infrastructure, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

ED 20-02, ED 20-03, ED 20-04: The Patch Tuesday Directives

Windows runs federal government systems at massive scale. When Microsoft's Patch Tuesday updates included critical vulnerabilities, CISA couldn't wait for normal patch cycles. These three directives targeted specific vulnerabilities from January, July, and August 2020 Patch Tuesdays, as detailed in The Hacker News.

ED 20-04 was particularly significant—it targeted Netlogon Elevation of Privilege, a vulnerability that allowed attackers to escalate privileges on Windows domain networks. For a federal government running thousands of interconnected Windows systems, this was nightmare fuel.

Agencies had to patch these systems on accelerated timelines, often within days rather than months, as highlighted by NCUA's report.

ED 21-01: Mitigating Solar Winds Orion Code Compromise

This one changed everything. In December 2019, Russian state-sponsored attackers inserted malicious code into Solar Winds Orion software updates. When Solar Winds pushed updates, the backdoor spread to 18,000 customers, including multiple federal agencies, as reported by Industrial Cyber.

ED 21-01 was issued in response. Agencies had to immediately disconnect or isolate affected Solar Winds systems, scan for indicators of compromise, and implement detection mechanisms.

The Solar Winds breach showed that supply chain compromise wasn't theoretical. It was a present-day threat that could affect even well-managed organizations, as discussed in The Hacker News.

ED 21-02: Microsoft Exchange On-Premises Vulnerabilities

In early 2021, Microsoft disclosed zero-day vulnerabilities in Exchange Server. Attackers were actively exploiting these vulnerabilities in the wild. ED 21-02 demanded immediate patching or remediation of all on-premises Exchange systems, as noted by CISA's official directives.

This was particularly urgent because Exchange is widely deployed across federal agencies for email and communication. Leaving it unpatched meant potential breach of federal communications.

ED 21-03: Pulse Connect Secure Product Vulnerabilities

Pulse Connect Secure is a remote access VPN solution. Vulnerabilities in this product could allow attackers to bypass authentication and gain remote access to agency networks. ED 21-03 required agencies to patch or disable vulnerable instances, as highlighted by NCUA's report.

For federal agencies with distributed workforces, this created real operational challenges. Disable VPN access? That impacts thousands of remote workers. But leaving vulnerabilities unpatched risked the entire network.

ED 21-04: Windows Print Spooler Service Vulnerability

The Windows Print Spooler vulnerability (Print Nightmare) was almost embarrassing in its simplicity. A vulnerability in a service that manages printers could be exploited for privilege escalation. Attackers could gain system-level access through a printer, as discussed in Industrial Cyber.

ED 21-04 required immediate patching or disabling of the Print Spooler service. Most agencies disabled it rather than wait for patches.

ED 22-03: VMware Vulnerabilities

VMware runs virtualization infrastructure across federal data centers. Critical vulnerabilities in VMware v Center and other products could allow attackers to compromise entire virtualized environments. ED 22-03 required patching of multiple critical CVEs, as noted by The Hacker News.

ED 24-02: Nation-State Compromise of Microsoft Corporate Email

This is the most recent retired directive. In 2024, Chinese state-sponsored actors compromised Microsoft's corporate email systems. This wasn't a product vulnerability—it was a compromise of Microsoft's internal infrastructure, as reported by Industrial Cyber.

ED 24-02 required federal agencies to scan their environments for indicators of compromise from this breach, implement additional monitoring, and verify email security measures.

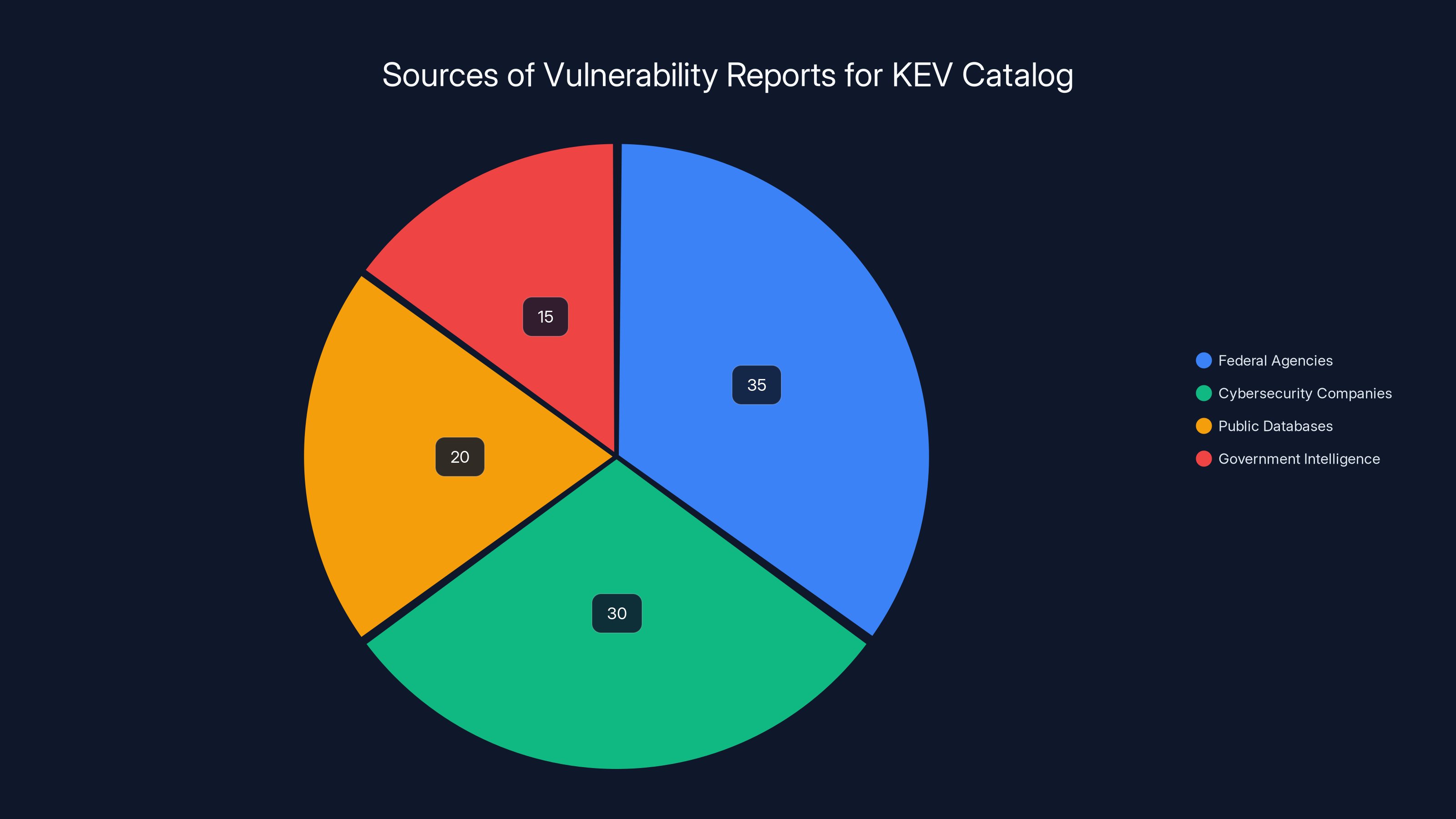

The pie chart illustrates the estimated distribution of sources contributing to the KEV catalog, highlighting the significant role of federal agencies and cybersecurity companies. Estimated data.

BOD 22-01: The Framework That Replaces Emergency Directives

So what replaces all of these Emergency Directives? Binding Operational Directive 22-01, issued on November 3, 2021: Reducing the Significant Risk of Known Exploited Vulnerabilities.

BOD 22-01 is fundamentally different from Emergency Directives. It's not a response to a specific threat. It's a systematic framework for managing the vulnerabilities most likely to be exploited in the real world, as explained by CISA's official directives.

Here's how it works. CISA maintains a catalog of known exploited vulnerabilities—the KEV catalog. This isn't every vulnerability ever discovered. It's a curated list of vulnerabilities that CISA has evidence are actively being exploited by threat actors, as noted by NCUA's report.

Agencies don't have to guess which vulnerabilities matter most. CISA tells them explicitly. "Here are the vulnerabilities that matter. These have evidence of active exploitation. You need to remediate them."

For each vulnerability in the KEV catalog, BOD 22-01 establishes a deadline. The deadline depends on whether the vulnerability affects systems directly connected to the internet or systems on internal networks, as discussed in The Hacker News.

Internet-facing systems? Tighter deadlines, usually 14 days. Internal systems? More time, but still mandatory. The point is to force prioritization. Agencies can't remediate everything immediately. BOD 22-01 tells them what to remediate first.

BOD 22-01 also includes a mechanism for exceptions. If an agency can't patch a vulnerability within the deadline, they can request an exception and propose compensating controls. But those exceptions require documentation, justification, and regular review, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

This creates accountability. Agencies can't just ignore deadlines. They have to actively justify every unpatched system.

Why BOD 22-01 Is Better Than Emergency Directives

Emergency Directives are reactive. A vulnerability is exploited, CISA issues a directive. BOD 22-01 is proactive. It establishes a standing mechanism that automatically applies to newly discovered vulnerabilities without requiring new directives, as explained by CISA's official directives.

Emergency Directives create fragmented compliance efforts. Each directive has different reporting requirements and deadlines. BOD 22-01 creates a unified framework.

Emergency Directives require CISA to maintain ongoing enforcement of old directives while responding to new threats. BOD 22-01 allows CISA to focus resources on identifying which vulnerabilities matter, not enforcing individual directives, as noted by NCUA's report.

For agencies, the benefit is clearer prioritization. Instead of managing multiple overlapping directives, they have one clear framework: focus on known exploited vulnerabilities first, follow the deadlines, and document exceptions.

Secure by Design: The Philosophy Behind the Retirement

The decision to retire these directives reflects a broader shift in CISA's approach: Secure by Design.

Secure by Design means that security should be built into products from the start, not bolted on after the fact. It means vendors should make security the default, not an optional feature, as discussed in Industrial Cyber.

CISA Acting Director Madhu Gottumukkala explained it in the announcement: "The closure of these ten Emergency Directives reflects CISA's commitment to operational collaboration across the federal enterprise. Looking ahead, CISA continues to advance Secure by Design principles—prioritizing transparency, configurability, and interoperability so every organization can better defend their diverse environments."

What does Secure by Design actually mean in practice?

Transparency: Vendors should disclose security issues clearly and quickly. Agencies need to know what vulnerabilities exist and how serious they are.

Configurability: Products should allow agencies to enable security controls they need and disable features they don't. One-size-fits-all security doesn't work in diverse federal environments.

Interoperability: Security tools should work together. The best security isn't a single product. It's a coordinated system of tools that share information and coordinate responses.

The logic is elegant. If vendors built products securely from the start, if they disclosed vulnerabilities promptly, if they made security configurable, then CISA wouldn't need to issue Emergency Directives in response to compromises, as noted by NCUA's report.

But that's aspirational. The real world is messier. So in the meantime, BOD 22-01 provides the systematic approach.

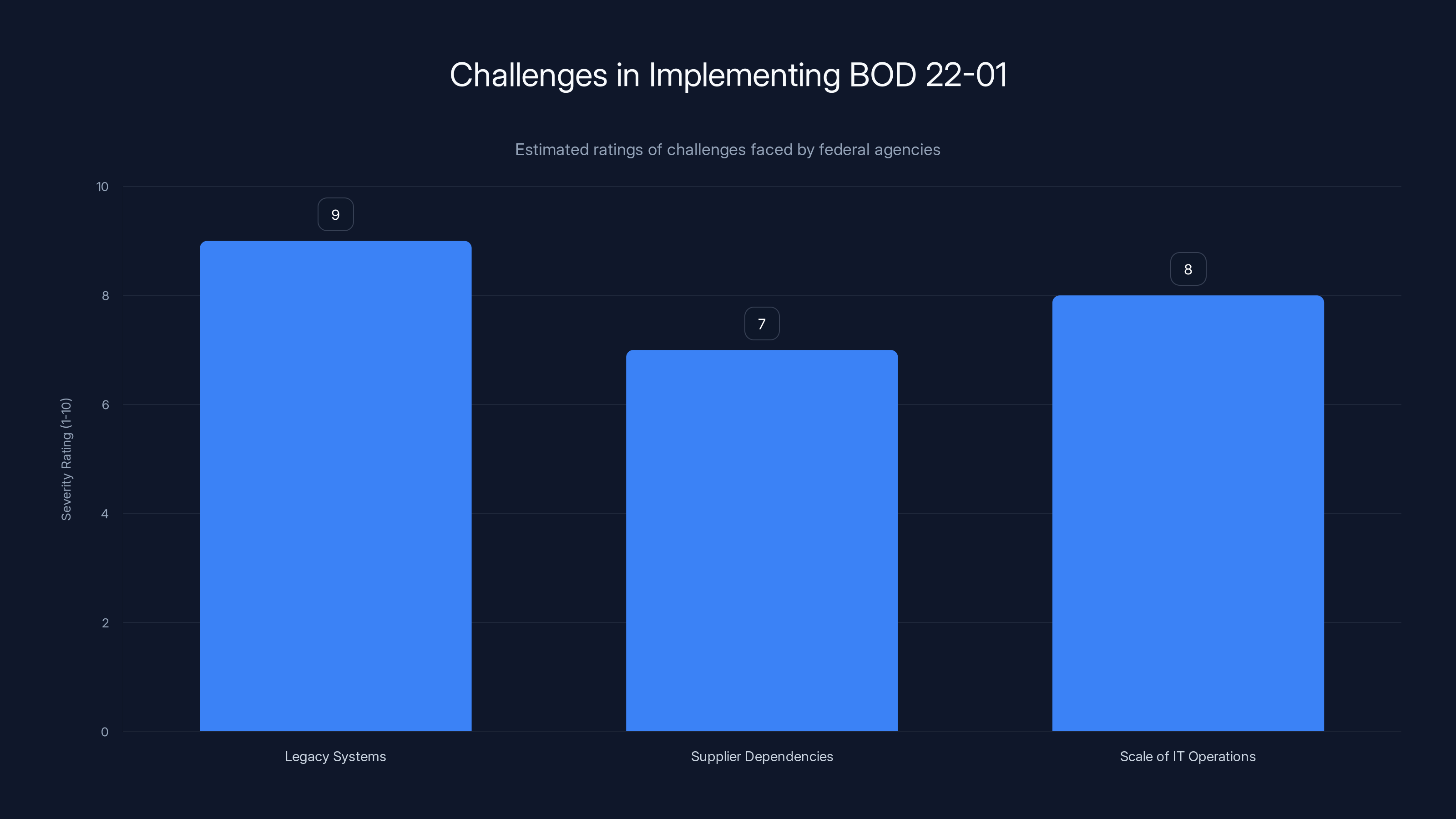

Legacy systems pose the greatest challenge in implementing BOD 22-01, followed by the scale of IT operations and supplier dependencies. Estimated data.

Impact on Federal Agencies: What Changes Now

For federal agency cybersecurity teams, this retirement creates both opportunities and challenges.

Simplified Compliance Structure

Agencies no longer need to maintain separate compliance tracking for ten different Emergency Directives. They consolidate everything under BOD 22-01. This reduces administrative overhead, as explained by Industrial Cyber.

But it also requires migration. Agencies need to ensure that vulnerabilities previously tracked under Emergency Directives are now tracked under BOD 22-01. The KEV catalog should capture them, but teams need to verify.

Increased Focus on Prioritization

Emergency Directives often came with specific guidance about which systems to patch first and how to validate compliance. BOD 22-01 is more flexible. Agencies have responsibility for prioritization, as noted by NCUA's report.

This is actually good—it allows agencies to prioritize based on their specific risk landscape. But it requires more internal decision-making.

Continuous Vulnerability Management

Emergency Directives had endpoints. Compliance deadline arrives, agencies achieve compliance, the directive closes. BOD 22-01 is continuous. The KEV catalog keeps growing. New vulnerabilities keep getting added, as highlighted by The Hacker News.

This means agencies can't treat vulnerability management as periodic projects. They need continuous processes.

Exception Management Becomes Critical

Each unpatched system requires justification and documentation. This sounds burdensome, but it's actually powerful. It forces organizations to think critically about risk. Why can't this system be patched? What compensating controls do we have? How often do we review this decision?

Agencies that treat exceptions casually will struggle. Agencies that use exceptions as a forcing function for security decision-making will improve their security posture, as discussed in Industrial Cyber.

The Evolution of Federal Cybersecurity Governance

This retirement represents a notable evolution in how federal government approaches cybersecurity.

In the early 2010s, federal cybersecurity was largely voluntary compliance. Agencies adopted security standards, but enforcement was weak. The result was predictable—inconsistent security across agencies, as noted by NCUA's report.

Then came major breaches. The Office of Personnel Management breach exposed background investigations of millions of federal employees. The IRS faced major security incidents. Agencies got hacked regularly.

CISA responded with more aggressive governance. Emergency Directives became the mechanism. When something urgent happened, CISA had a tool to force action, as highlighted by Industrial Cyber.

But Emergency Directives proved to be a blunt instrument. They work when you have a specific, immediate threat. But they're exhausting to maintain at scale. Each directive requires ongoing enforcement.

BOD 22-01 represents the next evolution. It's still mandatory—it has binding authority. But it's systematic rather than reactive. It tells agencies what matters and gives them mechanisms for prioritization, as discussed in The Hacker News.

Secure by Design is the next phase. If it works, vendors will build better products. Agencies will face fewer emergency situations. CISA will spend less time issuing emergency orders and more time preventing problems.

It's a logical progression: reactive emergency response → systematic framework → proactive prevention.

We're in the middle phases right now.

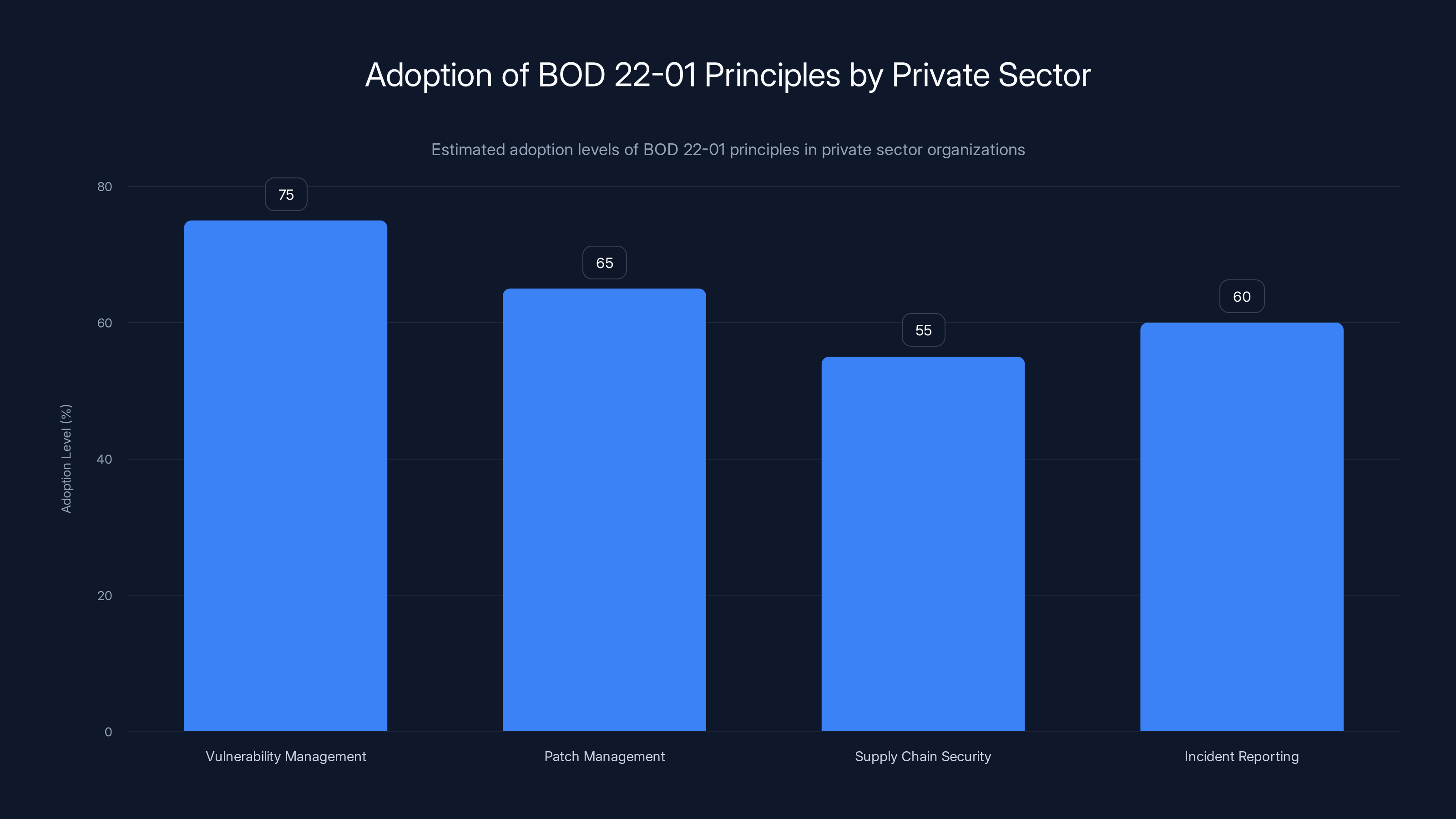

Estimated data shows that private sector organizations are increasingly adopting BOD 22-01 principles, particularly in vulnerability management and patch management.

The KEV Catalog: CISA's Most Important Asset

BOD 22-01's success depends entirely on one thing: the quality of the KEV catalog.

The KEV catalog is a database of known exploited vulnerabilities. "Known" means CISA has evidence—not suspicion, but actual evidence—that the vulnerability is being actively exploited by threat actors in the wild, as explained by CISA's official directives.

This is crucial. There are tens of thousands of published vulnerabilities. Agencies can't patch everything immediately. They need to know which ones matter.

CISA maintains the KEV catalog through a combination of sources. Intelligence from federal agencies about attacks. Information from commercial cybersecurity companies. Public exploit databases. Government threat intelligence, as noted by NCUA's report.

When evidence emerges that a vulnerability is being actively exploited, it gets added to the KEV catalog. That triggers BOD 22-01 deadlines. Agencies have to prioritize it, as discussed in The Hacker News.

The catalog now tracks over 1,000 vulnerabilities with evidence of active exploitation. That's not hypothetical vulnerabilities. That's vulnerabilities that threat actors are actually using right now.

How Vulnerabilities Get Into the KEV Catalog

CISA doesn't add vulnerabilities casually. There's a process.

Vulnerability reports come in from various sources. A federal agency reports they were attacked via a specific vulnerability. A cybersecurity company publishes research showing active exploitation. Threat intelligence from foreign governments indicates attack activity, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

CISA analysts review the evidence. Is this actually being exploited in the wild, or is this just theoretical risk? They look for multiple indicators: exploit code availability, attack telemetry, victim reports.

Once evidence is confirmed, the vulnerability gets added. The KEV catalog entry includes the CVE identifier, the affected products, the deadline for remediation, and links to guidance.

Agencies start tracking compliance. They have to patch or mitigate within the deadline. If they can't, they document why and propose compensating controls.

CISA periodically reviews compliance. Agencies that consistently miss deadlines without justification face escalated status, as highlighted by NCUA's report.

The Value of Known Exploitation Evidence

Why does CISA require evidence of active exploitation rather than just severity? Because vulnerability severity is subjective, as discussed in The Hacker News.

Vendors rate vulnerabilities based on potential impact. A vulnerability rated 9.8 out of 10 in severity might never actually be exploited. It might require specific, rare conditions. Or exploit code might not exist.

Meanwhile, a vulnerability rated 7.5 in severity might be trivial to exploit and actively weaponized.

By focusing on known exploited vulnerabilities, CISA cuts through the noise. "Don't waste time patching theoretical vulnerabilities. Focus on the ones that threat actors are actually using right now."

This is practical risk management. It forces prioritization, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

Implementation Challenges: The Reality of BOD 22-01

BOD 22-01 looks good in theory. In practice, federal agencies face real challenges implementing it.

Legacy Systems That Can't Be Patched

Federal agencies run systems that predate the internet. Some are decades old. They support critical functions. You can't just shut them down to patch them, as noted by NCUA's report.

For example, some federal financial systems run on mainframes from the 1980s. The original vendors don't exist anymore. Source code is lost. You can't patch them. You can implement network segmentation, intrusion detection, and other compensating controls. But you can't patch.

BOD 22-01 allows exceptions for exactly this reason. But exceptions require documentation and justification, as discussed in Industrial Cyber.

Supplier Chain Dependencies

Federal agencies don't develop their own software. They depend on vendors. If a vulnerability exists in a vendor's product, agencies have to wait for the vendor to release a patch, as noted by The Hacker News.

Some vendors are good about this. They respond quickly. Others are slow. Some vendors have gone out of business.

Agencies can't control vendor patch release schedules. But they still have BOD 22-01 deadlines.

Again, exceptions exist. But the burden is on the agency to document that they're waiting for a vendor patch and to track when that patch becomes available.

The Sheer Scale of Federal IT

Federal agencies run millions of systems. Thousands of different software products. Dozens of different operating systems and platforms, as discussed in Industrial Cyber.

Scanning all of these for known exploited vulnerabilities, assessing patch applicability, testing patches, deploying patches, validating compliance—it's a massive operational effort.

Agencies with mature security programs can handle this. Agencies with smaller cybersecurity teams struggle.

CISA provides tools and guidance, but the actual work falls on agencies.

Balancing Security With Operational Continuity

Security patches sometimes break things. You deploy a patch, and suddenly a critical application stops working, as noted by NCUA's report.

Federal agencies can't tolerate downtime. Disrupting a federal service can affect millions of citizens. So they're cautious about patching.

But BOD 22-01 has firm deadlines. Agencies face a trade-off: risk security by delaying patches to ensure stability, or patch quickly and risk operational disruption.

Good agencies solve this with staged deployments. Test patches in development environments. Deploy to low-risk systems first. Monitor carefully. Escalate gradually.

But this takes time. And the BOD 22-01 deadlines are firm, as highlighted by Industrial Cyber.

Estimated data showing the distribution of CISA Emergency Directives addressing key cybersecurity threats. SolarWinds and other threats had the highest number of directives.

Looking Forward: The Future of Federal Cybersecurity Governance

This retirement of Emergency Directives isn't an endpoint. It's a waypoint in CISA's evolution.

More Binding Operational Directives Coming

Emergency Directives aren't going away. CISA will still issue them when necessary. But new ones will likely be shorter-lived, as discussed in NCUA's report.

When a new zero-day emerges, CISA might issue an emergency directive requiring immediate action while it works on incorporating the vulnerability into BOD 22-01's framework.

But the directives will increasingly be temporary measures, not permanent governance mechanisms.

Expanded KEV Catalog Coverage

The KEV catalog will grow. CISA is constantly identifying newly exploited vulnerabilities. The catalog will expand to cover emerging threat landscapes, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

This creates ongoing work for agencies. But it also creates clearer prioritization.

Vendor Accountability Increasing

Secure by Design isn't just philosophy. CISA is starting to enforce it, as highlighted by The Hacker News.

Vendors who release products with easily exploitable vulnerabilities, who are slow to patch, who don't disclose vulnerabilities transparently—they're finding it harder to do business with federal agencies.

Expect to see more vendor accountability mechanisms in coming years.

Automation of Compliance

Manual compliance tracking isn't sustainable at federal scale. Expect to see more automated tools for vulnerability scanning, patch compliance reporting, and exception management, as noted by NCUA's report.

CISA provides some tools. But the market will likely develop commercial solutions specifically designed for BOD 22-01 compliance.

Integration With Broader Risk Management

Currently, BOD 22-01 focuses on known exploited vulnerabilities. In the future, expect to see integration with broader risk management frameworks, as discussed in Industrial Cyber.

For example, vulnerabilities affecting systems that handle sensitive data might get tighter deadlines. Vulnerabilities affecting internet-exposed systems might get priority over internal systems.

This would create more sophisticated risk-based governance.

Implications for Private Sector Organizations

Though BOD 22-01 applies to federal agencies, private sector organizations should pay attention.

Increased Expectations From Federal Customers

If your organization does business with federal agencies, expect them to ask about your vulnerability management practices. They'll want to know how you prioritize patches, how you handle known exploited vulnerabilities, how you meet deadlines, as noted by The Hacker News.

Federal agencies are increasingly implementing vendor management programs that align with BOD 22-01 principles.

Supply Chain Pressure

Federal agencies depend on vendors. If a critical vendor is compromised, federal agencies suffer. Expect federal agencies to increase scrutiny of their supply chain partners' security practices, as discussed in Industrial Cyber.

This includes your development security practices, your patch management, your vulnerability disclosure processes.

Benchmarking Best Practices

BOD 22-01 represents federal government best practices for vulnerability management. If your organization wants to be secure, these are good practices to adopt, as noted by NCUA's report.

Focusing on known exploited vulnerabilities, maintaining clear deadlines, documenting exceptions, continuous monitoring—these aren't just federal requirements. They're good security hygiene.

Many commercial organizations are adopting BOD 22-01 principles not because they're required to, but because the practices are sound.

The Expanding Scope of Mandatory Cybersecurity Requirements

BOD 22-01 is one of several binding directives now in place. CISA has also issued binding directives on incident reporting, email security, and other topics, as highlighted by Industrial Cyber.

For organizations seeking federal contracts, familiarity with these directives is increasingly important.

The Broader Context: A Maturing Security Landscape

The retirement of these ten Emergency Directives tells a larger story about how cybersecurity governance is maturing.

Ten years ago, cybersecurity was largely reactive. An attack happened, organizations responded. Governance was incident-driven, as noted by NCUA's report.

Now, governance is becoming proactive and systematic. Organizations identify risks before attacks happen. They implement controls to prevent compromise.

Emergency Directives worked when used rarely. But they can't be the primary governance mechanism. There are too many vulnerabilities, too many threats, too much attack activity, as discussed in Industrial Cyber.

Systematic governance—BOD 22-01—is necessary to scale. It tells organizations what matters, gives them clear deadlines, and creates accountability.

Secure by Design is the next evolution. Instead of constantly responding to vulnerabilities in insecure products, vendors build products that are secure from the start.

This progression—from reactive emergency response to systematic governance to proactive security—is happening across cybersecurity, as highlighted by The Hacker News.

Emergency Directives aren't disappearing. CISA will still issue them when necessary. But they're no longer the primary mechanism. They're supplementary to a more mature governance framework.

For federal agencies, this is good news. It means clearer expectations, more predictable requirements, and better-defined paths to compliance.

For vendors, it means they need to focus on security from the start. Disclosure transparency. Rapid patching. Configurability.

For the broader security landscape, it means vulnerability management is becoming more systematic and evidence-based.

Key Takeaways for Security Leaders

If you lead security for a federal agency or organization doing business with federal agencies, here's what matters.

First, understand BOD 22-01 intimately. It's your new baseline for federal cybersecurity compliance. Familiarize your team with the KEV catalog, the deadlines, the exception process, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

Second, implement continuous vulnerability scanning and discovery. You can't manage what you can't see. Build systems that automatically identify which of your systems are running vulnerable software.

Third, develop documented exception processes. Not every system can be patched within BOD 22-01 timelines. Create a process for documenting why, implementing compensating controls, and tracking review schedules, as discussed in NCUA's report.

Fourth, focus on prioritization. You probably can't patch everything immediately. Use the KEV catalog to prioritize. Focus on known exploited vulnerabilities first.

Fifth, track compliance carefully. CISA audits compliance. Keep detailed records of what you patched, when you patched it, what exceptions you have, and what compensating controls you've implemented, as highlighted by The Hacker News.

Sixth, engage with your vendors. If a vendor is slow to patch, make your concerns known. Vendor behavior matters for federal compliance.

Seventh, think about Secure by Design in your vendor selection. When evaluating new products, consider the vendor's security practices. Do they disclose vulnerabilities promptly? Do they patch quickly? Is their product configurable?

FAQ

What is an Emergency Directive?

An Emergency Directive is a mandatory order issued by CISA to all Federal Civilian Executive Branch agencies requiring immediate action in response to a significant cybersecurity threat. Unlike advisory guidance, Emergency Directives have binding authority and agencies must verify compliance within 24 to 72 hours. They're CISA's most powerful enforcement tool, used only when immediate action is necessary to prevent widespread compromise, as explained by CISA's official directives.

Why did CISA retire these specific Emergency Directives?

CISA retired these ten Emergency Directives because they were successfully implemented and are now redundant under BOD 22-01. Each directive addressed a specific threat (Solar Winds, Exchange vulnerabilities, DNS tampering, etc.) and once agencies achieved compliance and implemented permanent fixes, the directives outlived their purpose. BOD 22-01 provides a more systematic framework for managing known exploited vulnerabilities without requiring individual emergency directives for each threat, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

What is BOD 22-01 and how does it work?

Binding Operational Directive 22-01 is a mandatory framework requiring federal agencies to prioritize remediation of known exploited vulnerabilities. CISA maintains a curated catalog (KEV catalog) of vulnerabilities with evidence of active exploitation. The directive establishes strict deadlines for patching based on system exposure (14 days for internet-facing systems, longer for internal systems). Agencies that can't meet deadlines must document exceptions and implement compensating controls. It's a systematic replacement for reactive Emergency Directives, as explained by NCUA's report.

What does Secure by Design mean for vendors?

Secure by Design means vendors should build security into products from the start rather than adding it afterward. It requires transparency (disclosing vulnerabilities clearly and promptly), configurability (allowing organizations to enable security controls they need), and interoperability (ensuring security tools work together). The principle shifts security responsibility partly back to vendors rather than forcing customers to apply endless patches and workarounds to insecure products, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

How does BOD 22-01 affect private sector organizations?

Private sector organizations are affected indirectly. If they do business with federal agencies, expect increased vendor management scrutiny aligned with BOD 22-01 principles. Additionally, many organizations adopt BOD 22-01 practices voluntarily because the principles are sound—focusing on known exploited vulnerabilities, maintaining clear deadlines, and documenting exceptions all improve security posture. The framework represents federal government best practices that benefit any organization's vulnerability management, as highlighted by The Hacker News.

What happens if an agency can't meet a BOD 22-01 deadline?

Agencies don't automatically fail compliance. They can request an exception and document why they can't patch the vulnerability within the deadline (legacy systems that can't be patched, waiting for vendor patches, etc.). However, they must implement compensating controls and submit documentation. These exceptions are tracked and CISA audits them. Unjustified exceptions or patterns of non-compliance result in escalated compliance status and potential enforcement action, as discussed in NCUA's report.

What is the KEV catalog?

The KEV (Known Exploited Vulnerabilities) catalog is CISA's curated database of vulnerabilities with confirmed evidence of active exploitation in the wild. It includes CVE identifiers, affected products, remediation deadlines, and guidance links. Organizations use it to prioritize patching efforts—vulnerabilities in the KEV catalog get priority because there's evidence threat actors are actively using them. The catalog now tracks over 1,000 vulnerabilities and grows regularly as new exploitations are discovered, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

Will CISA still issue Emergency Directives?

Yes, CISA will continue issuing Emergency Directives when necessary for immediate threats that require urgent action. However, the retirement of these ten directives suggests Emergency Directives will increasingly be temporary measures (days to weeks) rather than long-term governance mechanisms. New zero-days will likely trigger emergency directives while CISA works on incorporating them into BOD 22-01's systematic framework. The trend is toward more systematic governance and fewer permanent emergency orders, as highlighted by The Hacker News.

Conclusion: A Mature Approach to Federal Cybersecurity

The retirement of these ten Emergency Directives marks more than just administrative housekeeping. It signals evolution in how federal government approaches cybersecurity.

For years, federal cybersecurity relied on reactive emergency response. A critical vulnerability was exploited, CISA issued an emergency directive, agencies scrambled to comply. It worked, but it wasn't sustainable. You can't run an organization on permanent emergency mode, as noted by Industrial Cyber.

BOD 22-01 represents a shift to systematic governance. Clear criteria (known exploited vulnerabilities). Clear deadlines. Clear accountability. Organizations know what matters and when it matters. They can plan accordingly, as discussed in NCUA's report.

This is more mature. It's also more demanding. Continuous vulnerability management requires ongoing investment. Exception documentation requires rigor. Compliance tracking requires discipline.

But the result is better security. Not perfect security—that's impossible. But focused security. Organizations prioritize the vulnerabilities that threat actors are actually exploiting, not theoretical risks, as highlighted by The Hacker News.

For federal agencies, this retirement should be welcomed. It means clearer expectations, more predictable requirements, and a framework that scales to the complexity of modern IT.

For vendors, it means the expectations are rising. Security by design isn't optional. Disclosure transparency is expected. Rapid patching is necessary.

For the broader security landscape, it signals that cybersecurity governance is maturing from crisis management to systematic risk reduction.

The threats are still real. Vulnerabilities will still be discovered. Threat actors will still exploit them.

But the response mechanisms are becoming more systematic, more evidence-based, and ultimately more effective.

These ten Emergency Directives did their job. They forced urgent action when urgent action was needed. Now the federal government has a more mature framework.

That's progress worth acknowledging.

Related Articles

- CrowdStrike SGNL Acquisition: Identity Security for the AI Era [2025]

- AI-Generated Non-Consensual Nudity: The Global Regulatory Crisis [2025]

- Illinois Data Breach Exposes 700,000: How Government Failed [2025]

- NSO's Transparency Claims Under Fire: Inside the Spyware Maker's US Market Push [2025]

- Iran's Internet Collapse: What Happened and Why It Matters [2025]

- US Withdraws From Internet Freedom Bodies: What It Means [2025]

![CISA Retires 10 Emergency Directives: What Changed for Federal Cybersecurity [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/cisa-retires-10-emergency-directives-what-changed-for-federa/image-1-1767987451522.jpg)