Digital Authoritarianism and Free Speech: The 2025 Turning Point

The digital landscape of 2025 marks a watershed moment for American free expression. What began as relatively neutral content moderation policies designed to protect communities from harm has evolved into a sophisticated system of speech suppression coordinated between government agencies and private technology platforms. The convergence of political will, corporate interests, and algorithmic power has created what experts describe as an era of digital authoritarianism—one where the tools meant to govern online discourse have become instruments of governmental control.

This transformation didn't happen overnight. It represents the culmination of years of pressure, regulatory threats, legal maneuvering, and behind-the-scenes negotiations between federal agencies and technology companies. Yet 2025 stands out as the year when the infrastructure of digital control became undeniably visible, when the mechanisms of suppression moved from theoretical possibility to documented practice.

The removal of immigration-focused applications like ICEBlock and Eyes Up from major app stores illustrates this shift perfectly. These apps, designed to alert communities to Immigration and Customs Enforcement operations, were removed not because they violated traditional app store policies but because platforms reclassified ICE agents as a "vulnerable group" requiring protection—a classification that has no historical precedent in platform governance. The legal challenge filed by Joshua Aaron, the developer behind ICEBlock, exposes the constitutional questions at the heart of this moment: when private platforms become de facto government actors, can they legally suppress speech the government disfavors? According to FindArticles, this lawsuit highlights the tension between private platform policies and government influence.

Simultaneously, the Trump administration has employed traditional tools of speech suppression with renewed vigor. Federal prosecutors have filed lawsuits against journalists covering Trump, many settling with financial agreements that resemble protection payments more than legal resolutions. Immigration organizers have faced deportation threats over their political speech. The Federal Communications Commission has been weaponized against broadcast programs deemed insufficiently friendly to administration priorities. These aren't isolated incidents—they represent a coordinated campaign to control narrative and suppress dissent, as reported by New York Post.

What makes 2025 historically significant is the complete convergence of control mechanisms. For the first time in American history, every major social media platform is owned or controlled by Trump-friendly billionaires. This consolidation coincides with a fundamental shift in how Americans consume news: social media has become the primary news source for most citizens, replacing traditional media gatekeepers. When platform control, news consumption patterns, and government pressure align, the conditions for systematic speech suppression become optimal.

The mechanics of this suppression operate through multiple channels simultaneously. Content moderation policies, once relatively transparent guidelines for community safety, have become opaque instruments of political control. Algorithms that determine reach and visibility operate as invisible censors, amplifying some voices while silencing others based on criteria users cannot see or challenge. Government pressure, applied through regulatory threats and legal intimidation, influences how platforms interpret and enforce these policies. The result is a system where suppression feels distributed and inevitable rather than deliberate and illegal—making it simultaneously more effective and harder to oppose.

Understanding this moment requires examining not just individual instances of suppression but the systematic architecture that enables them. It requires understanding how content moderation evolved from a safety tool into a control mechanism, how platform consolidation eliminated alternatives, how government pressure became normalized, and what legal and technological barriers exist to challenging this system. It also requires understanding what's at stake: the ability of citizens to organize, resist, and advocate for change in a supposedly democratic system.

The Evolution of Content Moderation: From Safety Tool to Control Mechanism

The Original Purpose: Community Safety and Harm Reduction

When social media platforms first emerged, they operated with minimal moderation. Early internet culture celebrated "free speech" as an absolute value, with platforms serving primarily as neutral distribution channels. As these platforms grew, they encountered genuine harms: child exploitation, coordinated harassment, incitement to violence, and other content that threatened user safety and platform viability. This genuine harm prompted the development of content moderation systems.

Initially, these systems focused on relatively clear-cut categories of harm. Child sexual abuse material was flagged and removed. Terrorist content that incited immediate violence was taken down. Coordinated harassment campaigns that targeted individuals were disrupted. These early moderation policies operated under a harm-reduction framework: remove content that causes direct, demonstrable harm while preserving as much speech as possible.

This approach made intuitive sense. Platforms were private entities with legitimate interests in preventing their systems from being used to harm people. Users generally supported removing content they felt threatened their safety. Moderators, often underpaid workers in developing countries, applied rules that seemed relatively straightforward. The system was imperfect but appeared to balance competing interests reasonably.

However, this harm-reduction framework contained an inherent problem: defining harm is inherently political. What counts as harmful to one group may be considered valuable speech by another. Attempts to remove "misinformation" about elections involve judgments about political facts. Removing "harassment" requires distinguishing between harsh criticism and targeted abuse. Flagging "extremist" content involves determining which political movements deserve protection. Every expansion of moderation categories beyond the clearest harms—child exploitation, terrorist incitement, non-consensual intimate imagery—involves political choices disguised as technical safety decisions.

The Mission Creep: From Harms to "Harmful Misinformation"

Beginning around 2016, content moderation underwent dramatic expansion. Platforms began removing not just content that directly caused harm but content deemed "harmful misinformation." This represented a fundamental shift in moderation philosophy. Misinformation is false or misleading information, but its removal requires platforms to make truth judgments. Those judgments inevitably reflect political positions.

The 2016 election provided the impetus for this expansion. Platforms faced pressure from politicians, journalists, and civil society groups concerned about false information's electoral impact. Simultaneously, concerns about Russian disinformation campaigns highlighted how false narratives could be weaponized to manipulate political outcomes. This genuine problem—foreign actors using platforms to spread false information—became the justification for vastly expanding what platforms would remove.

What followed was a continuous expansion of moderation categories. If false election information was dangerous, shouldn't platforms remove all election misinformation? If Russian disinformation was a problem, shouldn't platforms flag state media? If false health information could cause deaths, shouldn't platforms remove vaccine skepticism? If political extremism could lead to violence, shouldn't platforms remove content from extremist groups? Each expansion seemed logical in isolation but collectively transformed platforms from forums for public discourse into arbiters of truth and legitimacy.

The crucial problem with this evolution was that it eliminated meaningful appellate processes or transparency. Users couldn't understand why their content was removed. Researchers couldn't examine moderation decisions at scale. Journalists couldn't document patterns of removal. Platforms operated as judge, jury, and executioner with no accountability mechanisms, claiming that transparency about moderation rules would help bad actors circumvent them.

The Infrastructure of Invisible Control

As content moderation expanded, the infrastructure supporting it became increasingly invisible. Most content isn't removed by humans reviewing reports; it's caught by automated systems trained on massive datasets of previous removals. These systems make millions of decisions daily, but their logic remains opaque. A user might have content removed for violating policies they never read, applying rules they don't understand, judged by a system they can't see.

Parallel to removal systems are visibility algorithms that determine which content appears to users. These algorithms don't require content removal to suppress speech; they simply reduce visibility. A post might appear to your friends but not to the broader network. A creator's reach might drop dramatically overnight due to algorithmic changes they can't see or challenge. Content that violates no explicit policies can be made effectively invisible through algorithmic suppression.

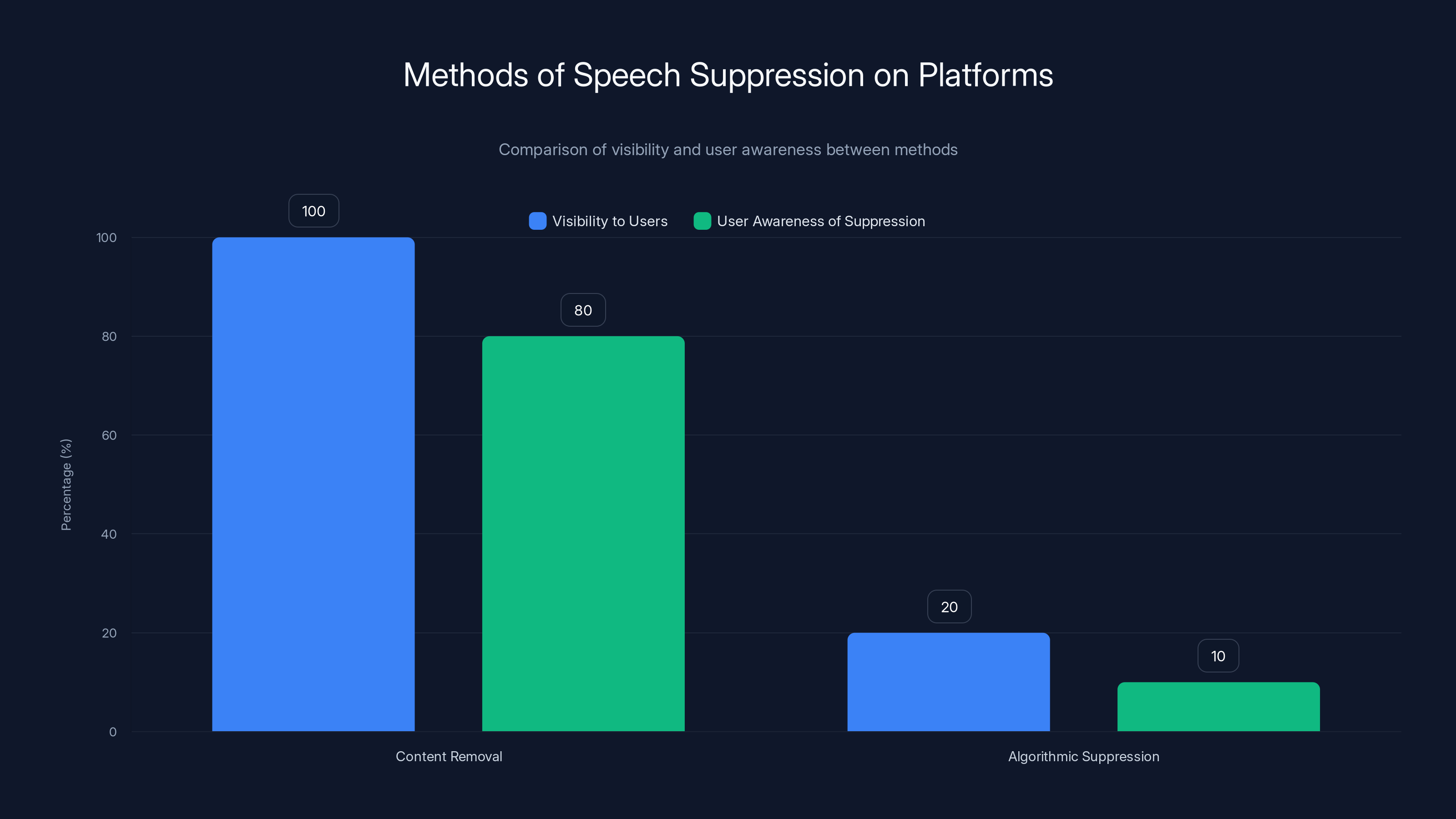

This distinction between removal and suppression is critical. Removal is obvious—the user knows their content was taken down. Suppression is subtle—they don't know their reach has been reduced, so they continue posting, believing they're being read when they're actually talking to themselves. From a government perspective, suppression is preferable: it controls speech without creating the visible martyrs that removal can generate.

The combination of opaque moderation policies, automated enforcement systems, and invisible algorithmic suppression created perfect infrastructure for political control. A government could pressure a platform to suppress certain speech, the platform could implement it through algorithmic changes and policy reinterpretations, and the suppression would appear to be neutral technical decisions rather than political censorship. The invisibility of the mechanism made it nearly impossible to prove coordination or challenge the decisions.

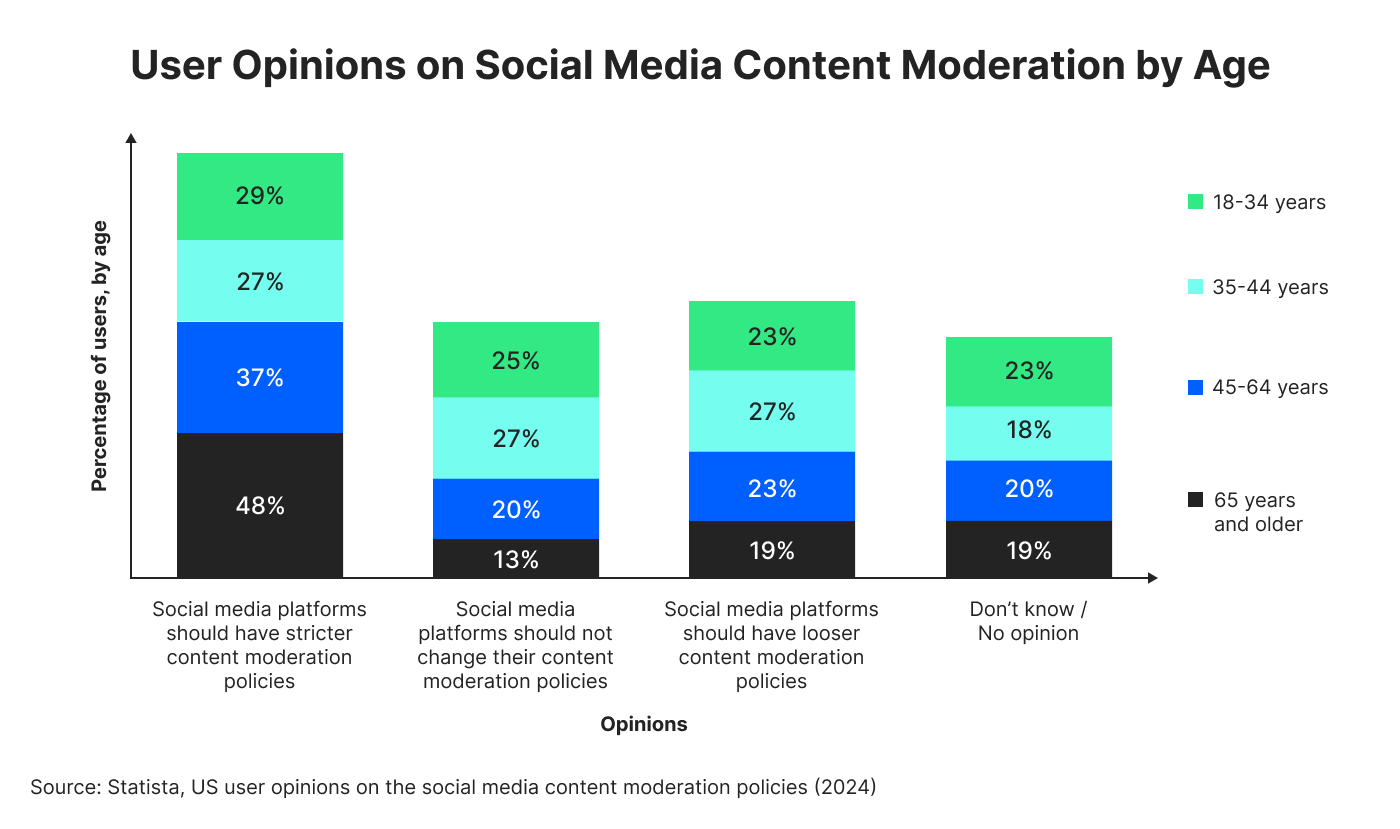

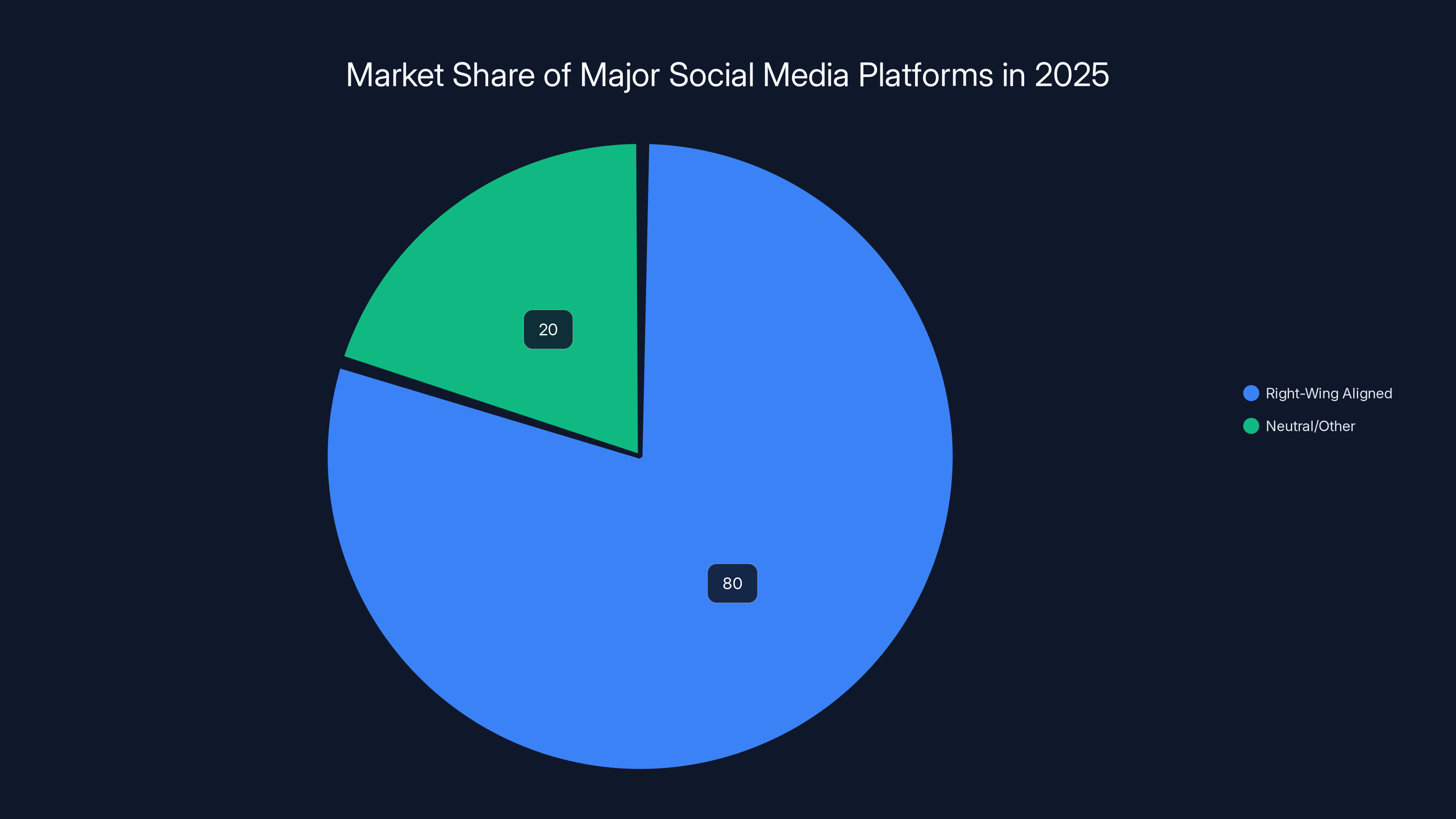

By 2025, an estimated 80% of major social media platforms are controlled by right-wing aligned billionaires, indicating a significant shift in digital gatekeeping. Estimated data.

Platform Consolidation: The Centralization of Digital Gatekeeping

The Concentration of Power in Private Hands

Throughout the 2010s, critics warned that social media was becoming dangerously concentrated. Facebook, Google (YouTube), Twitter, TikTok, and Amazon dominated digital communication and commerce. These platforms controlled how billions of people communicated, what information they received, and which voices reached audiences. Despite these warnings, consolidation continued. According to R Street Institute, this consolidation has significant implications for digital gatekeeping.

By 2025, the concentration had reached unprecedented levels. More significantly, ownership had consolidated around a specific political faction. Elon Musk purchased Twitter in 2022 and transformed it into a platform explicitly aligned with right-wing politics. Mark Zuckerberg, facing regulatory pressure, shifted toward a similar alignment, appointing executives known for opposing content moderation restrictions. When TikTok, the one major platform not explicitly aligned with Trump supporters, faced a ban, the consortium that purchased it included Larry Ellison's company—Ellison being a Trump supporter and financial backer.

The result is remarkable: for the first time in American history, every major social media platform is controlled by politically aligned billionaires. This isn't a diverse ecosystem where suppression at one platform means users can migrate to alternatives. This is a unified system where suppression is coordinated and unavoidable.

The significance of this cannot be overstated. In earlier eras, when governments wanted to suppress speech, they faced a fundamental problem: media outlets could refuse to cooperate, underground publications could circulate, alternative channels could emerge. The government's control was incomplete because communication technology was distributed. In 2025, that distribution is gone. If you want to reach a broad audience, you must use platforms controlled by politically aligned billionaires who willingly collaborate with government suppression.

The Illusion of Alternatives

When critics point out this monopoly, the standard response is that alternatives exist. People can use Mastodon, Bluesky, or other decentralized platforms. This response fundamentally misunderstands how network effects work. A communication platform's value lies not in its technical features but in who uses it. A superior platform used by 10,000 people has less value than an inferior platform used by billions. Network effects mean that alternatives aren't genuinely competitive—they're niche communities for the technologically sophisticated.

Moreover, alternative platforms face their own challenges. Bluesky, presented as a Twitter alternative, remains small and accessible primarily to tech-savvy users. Mastodon requires users to understand server selection and federation. Signal offers encrypted messaging but lacks the social network effects of Instagram or WhatsApp. These alternatives might offer superior privacy or better alignment with user values, but they can't replicate the reach and social connectivity of major platforms.

Governments understand this implicitly. Why invest resources in suppressing speech on niche platforms when you can pressure the three platforms where 90% of people consume content? The consolidation of platforms means that suppressing speech at those platforms effectively suppresses it for most citizens.

The Asymmetry of Platform Power

Platform power is inherently asymmetrical. Users are entirely dependent on platforms for access. Platforms depend on users for content and engagement, but this dependence is mediated through algorithms they control. A user can't make their content visible—the platform's algorithm decides visibility. A user can't ensure their account isn't suspended—the platform's moderation teams make that decision. A user can't migrate their social network—the platform controls who they're connected to.

Governments have learned to exploit this asymmetry. By pressuring platforms, they can control speech without directly suppressing citizens. The platform becomes the intermediary, the apparent source of suppression, while government pressure remains hidden. Citizens might blame the platform's policies rather than recognizing government coordination.

This is why Joshua Aaron's lawsuit against Apple is so significant. It makes explicit what's usually implicit: platforms are making moderation decisions they wouldn't otherwise make in response to government pressure. By proving government coordination, the lawsuit exposes the mechanism of suppression that typically remains hidden, as highlighted by Al Jazeera.

Content removal is more visible and users are more aware of it compared to algorithmic suppression, which is less visible and often goes unnoticed. Estimated data.

Government Pressure Mechanisms: The Carrots and Sticks

Regulatory Threats and Antitrust Concerns

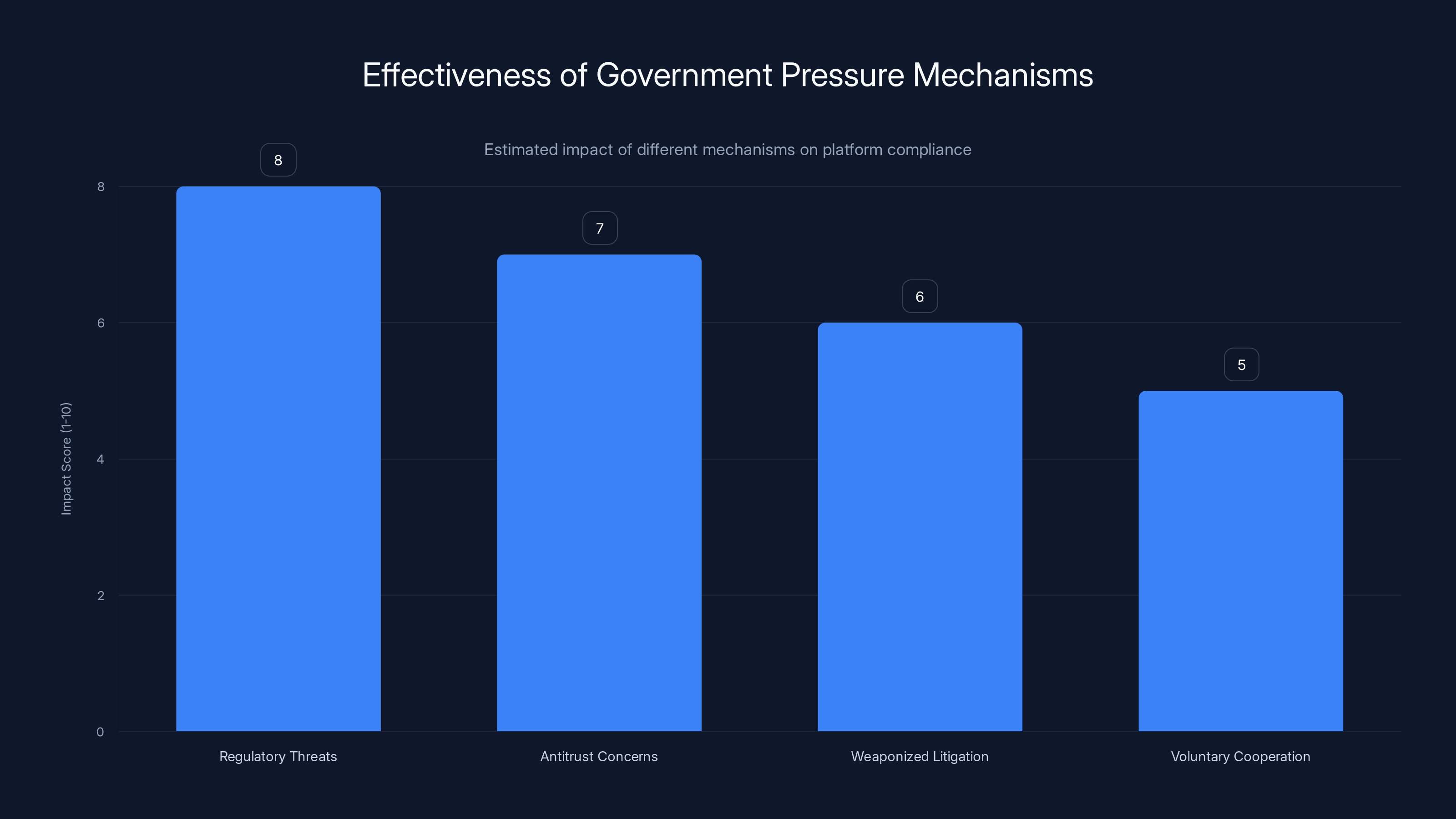

The Trump administration's approach to platform control relies heavily on regulatory threats. Platforms face potential antitrust action, regulatory crackdowns, and legislative restrictions. These threats are effective because platforms have genuine regulatory vulnerabilities. The concentration of platform power has made antitrust concerns legitimate—the question isn't whether these platforms are monopolies but how to address their monopolistic behavior.

Governments can exploit these legitimate concerns to pressure compliance with speech suppression. When the Department of Justice suggests to Apple that an app might endanger government employees, the implication is clear: cooperate with this moderation request or face regulatory consequences. The threat might not be explicit, but it's understood. Platforms that face pressure can either comply with suppression requests or risk regulatory action that would be far more costly.

This mechanism is particularly effective because it operates in the space between explicit coercion and voluntary cooperation. Platforms can claim they're making independent moderation decisions, and in one sense they are—no government official is directly ordering them to suppress speech. But the regulatory context makes voluntary suppression practically mandatory. Refusing a government suggestion risks regulatory retaliation; complying requires minimal resources and keeps regulators happy.

Weaponized Litigation

Parallel to regulatory threats, the administration has deployed litigation as a speech suppression tool. Filing lawsuits against journalists who cover Trump unfavorably, initiating legal action against immigration organizers for their political speech, and pursuing prosecutions against political opponents all serve a dual purpose: they target individual speakers while signaling to platforms what speech the government disfavors.

These lawsuits often lack legal merit—that's the point. The goal isn't necessarily to win in court but to impose costs on speakers. Defending litigation is expensive and time-consuming, creating a chilling effect on speech even if the cases are eventually dismissed. Moreover, settlements that emerge from these suits often include silence clauses, preventing speakers from discussing the government's pressure on them. This creates a hidden landscape of suppressed speech where speakers have been effectively silenced through legal costs rather than criminal prosecution.

From a platform perspective, these lawsuits indicate which types of speech the government prioritizes suppressing. If the government is aggressively litigating against journalists covering Trump, platforms understand the government's position on that speech. The message is clear without requiring explicit coordination: suppress this type of speech or expect legal problems.

The Revolving Door Between Government and Platforms

A less visible but crucial mechanism of government influence over platforms is personnel movement. Government officials move to platform policy positions, bringing regulatory relationships and perspectives with them. Conversely, platform officials move to government positions, ensuring that government agencies understand how to effectively pressure platforms. This revolving door creates informal networks and shared interests that facilitate coordination without explicit orders.

These personnel movements aren't inherently problematic—they're how government and industry routinely cooperate. But they create opportunities for informal influence that's difficult to document. A former platform executive now in the government can suggest policy changes to former colleagues still at the platform. These conversations happen outside formal channels, aren't recorded, and can't be FOIA-requested. But they're effective.

The revolving door also creates cultural alignment. Government officials understand how platforms operate from personal experience. Platform officials understand government priorities from their time in government. This shared understanding facilitates cooperation that feels natural rather than coordinated, voluntary rather than coerced.

The ICEBlock Case: Suppressing Immigration-Focused Speech

The Genesis of Anti-ICE Applications

The ICEBlock app emerged from genuine grassroots organizing. Immigration activists developed tools to warn communities about ICE operations, allowing immigrants to avoid enforcement actions and protect themselves. The app was simple in concept: users could report ICE sightings, and other users would see warnings in their locations. This wasn't novel—similar warning systems exist for police checkpoints and other enforcement operations.

From a technical and legal perspective, the app didn't violate App Store policies. It didn't facilitate violence, harassment, or illegal activity. It was a communication tool that helped citizens warn each other about government enforcement activity—a straightforward exercise of First Amendment rights. Yet Apple moved to remove it.

Other similar apps faced removal as well. Eyes Up, designed to archive and catalog ICE operations, was removed. Red Dot and De ICER, apps that tracked law enforcement activity broadly, were removed specifically citing protection of ICE agents. The pattern is unmistakable: apps designed to inform citizens about ICE activities were systematically removed.

The Extraordinary Reclassification: ICE Agents as Vulnerable Groups

What makes the ICEBlock removal remarkable is the justification. Apple cited protection of a "vulnerable group"—but the vulnerable group allegedly in need of protection was ICE agents. This classification has no precedent in content moderation history. Police officers and government agents aren't treated as vulnerable groups requiring App Store protection. The classification was invented specifically to justify removing anti-ICE speech.

This represents content moderation at its most political. The policy was created to suppress particular speech, not to address genuine safety concerns. Daphne Keller, a former Google associate general counsel, stated bluntly: "I've never seen a policy like that, where cops are a protected class." She speculated that platforms "really needed to make this concession to the government for whatever reason—because of whatever pressure they were under or whatever benefit they thought they would get from making the concession."

Keller's assessment highlights the political nature of the removals. They're not justified by genuine safety concerns or consistent policy application. They're political decisions disguised as neutral moderation. The invention of a new policy classification to suppress anti-ICE speech reveals the coordination between government priorities and platform actions. Without government pressure, Apple would have no reason to create a novel policy protecting law enforcement agents from warnings about their activities.

The Legal Challenge and Constitutional Questions

Joshua Aaron's lawsuit alleges that by removing ICEBlock in response to Department of Justice pressure, Apple violated his First Amendment rights. This raises a fundamental question: when private platforms become essential infrastructure for public speech, and when government pressure drives moderation decisions, do First Amendment protections extend to those platforms?

Traditionally, the First Amendment restricts government action, not private action. Private companies can set their own speech policies. But this doctrine presumes meaningful alternatives exist—that speakers can use other channels if one platform suppresses their speech. When platforms become monopolistic gatekeepers, and when government pressure drives moderation decisions, the distinction between private action and government censorship becomes blurred.

The lawsuit raises the specter of state action doctrine: if government pressure causes a private entity to suppress speech, does the private action constitute unconstitutional government censorship? The Supreme Court has occasionally found state action in cases where government pressure overcomes the private entity's independent judgment. If Aaron can prove that Apple's moderation decision was driven by DOJ pressure rather than independent policy application, the lawsuit has legs.

Moreover, the lawsuit exposes what's typically hidden. Most government-platform coordination remains confidential. By documenting the DOJ's suggestion that Apple remove the app, followed by Apple's compliance, the lawsuit makes the mechanism visible. This visibility alone is valuable—it proves coordination that platforms would prefer to deny, as discussed in PBS NewsHour.

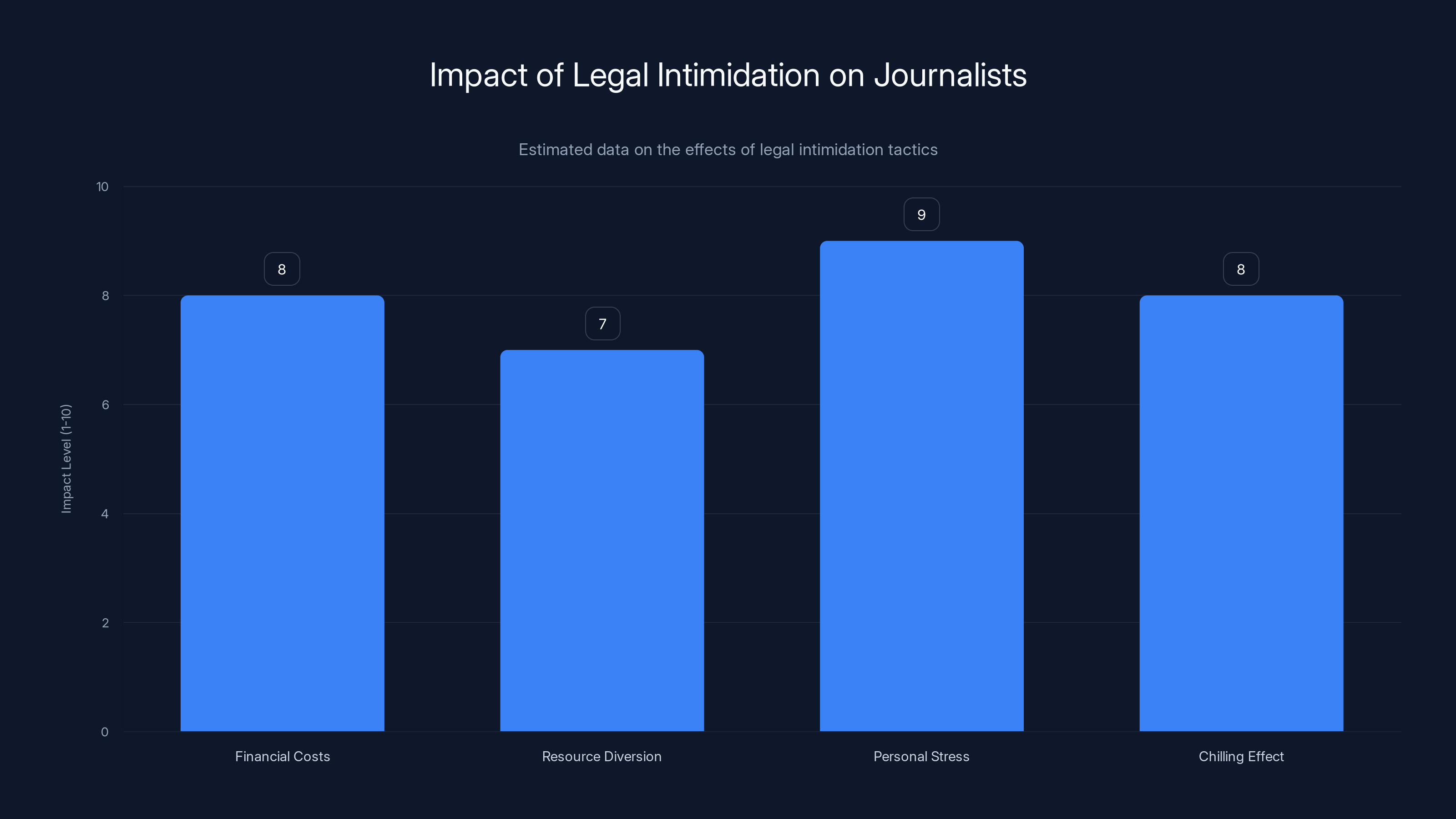

Legal intimidation tactics create significant financial burdens, stress, and a chilling effect on journalists, discouraging critical reporting. (Estimated data)

Traditional Speech Suppression Tools: Legal Intimidation and Prosecution

Frivolous Litigation Against Journalists

Parallel to app removals and platform suppression, the Trump administration has employed traditional speech suppression tools with renewed vigor. Journalists who reported negatively on Trump have faced lawsuits alleging defamation or false reporting. These lawsuits typically lack legal merit—courts have consistently ruled against them. But they serve their purpose: they impose costs on journalists and signal to media outlets what coverage the government opposes.

The financial costs of defending litigation are substantial. Even a meritless case requires paying lawyers for months or years. News organizations must divert resources from reporting to legal defense. Journalists face personal stress from being sued. These costs create a chilling effect—journalists and outlets become more cautious about critical reporting because the costs are real, even if the legal exposure isn't.

Moreover, some lawsuits have settled rather than proceeding to judgment. These settlements often include payments to the plaintiff that look suspiciously like hush money, combined with agreements not to discuss the settlement. The effect is to silence both the original reporting and the fact of government retaliation for the reporting. The public never learns that the government paid a journalist to stop reporting critically.

Deportation Threats Against Immigration Organizers

Another suppression mechanism involves targeting the citizenship status of immigration advocates. Immigration organizers and researchers who engage in political speech against the Trump administration have faced deportation proceedings. These proceedings operate on several levels. First, they directly suppress the speaker—if you're deported, you can't continue organizing or speaking. Second, they create a chilling effect—immigrants who advocate for more humane immigration policies understand the risk they face for political speech. Third, they delegitimize the speaker—once someone is in deportation proceedings, their political speech can be dismissed as coming from someone without legitimate standing.

The connection between political speech and deportation proceedings is sometimes direct, sometimes implied. In some cases, government documents explicitly reference the person's political organizing as the reason for pursuing deportation. In other cases, the connection is more subtle—people who engaged in particular political speech suddenly find themselves targeted for enforcement action they'd previously evaded. Either way, the message is clear: engage in certain political speech and face immigration consequences.

This is a particularly powerful suppression mechanism because it targets the most vulnerable speakers—immigrants who lack citizenship and thus lack constitutional protections that citizens enjoy. By targeting these speakers, the government suppresses not just their individual voices but the entire advocacy network they're part of. Other immigrants understand that political speech carries personal risk, creating a self-enforcing suppression system.

FCC Weaponization Against Broadcast Media

The Federal Communications Commission, which licenses broadcast television and radio stations, has been weaponized to suppress disfavored content. The administration has threatened FCC enforcement action against stations that broadcast critical coverage, particularly threatening their license renewals. For broadcast stations that depend on FCC licenses, this represents an existential threat.

The First Amendment nominally protects broadcast speech, but the FCC has regulatory authority over broadcast content through its authority to grant and revoke licenses. This creates leverage—stations can't ignore FCC threats without risking license loss. The mechanism is subtle: instead of ordering stations to suppress certain content, the FCC suggests that critical coverage constitutes harmful or unfair speech that could jeopardize license renewal. Stations understand the message without explicit censorship orders.

This is particularly effective against local broadcast stations, which lack the corporate resources of networks. A major network might risk FCC enforcement action. A local station probably can't afford extended litigation with the FCC and will self-censor rather than risk its license. This creates pressure on networks through their local affiliates, ensuring that controversial coverage becomes less likely throughout the broadcast ecosystem.

The News Consumption Crisis: When Platforms Become the Primary News Source

The Shift to Social Media News

For the first time in American history, a majority of citizens report getting their news from social media rather than traditional news outlets. This represents a fundamental shift in how information reaches the public. Traditional news had gatekeepers—editors who decided what stories were important, journalists who investigated and verified information. These gatekeepers had flaws and biases, but they had professional incentives to report accurately and institutional accountability for major errors.

Social media news lacks these gatekeepers. Stories spread based on engagement algorithms, not newsworthiness. Misinformation can circulate as quickly as accurate reporting. Sensationalism is rewarded because it drives engagement. Most users can't distinguish between reporting from established news outlets and posts from random accounts. The algorithm presents them equally, judging importance by engagement rather than accuracy or significance.

When social media becomes the primary news source, control of social media becomes control of the information environment. Platforms that suppress certain speech or elevate certain narratives are determining what information the public receives. This isn't newspaper editors making editorial decisions—it's algorithmic determination made by undisclosed criteria in service of platform business interests and government pressure.

The combination of platform consolidation and platform-dependent news consumption creates unprecedented concentration of information control. Governments no longer need to suppress newspapers or arrest journalists to control the information environment. They can pressure platforms, which control what billions of people see. The suppression is distributed through the algorithm, making it appear inevitable rather than political.

The Network Effects of Misinformation

When social media dominates news consumption, misinformation propagates through different mechanisms than in traditional media. A false story in a newspaper is limited to that outlet's readers and might be quickly corrected by competitors. A false story on social media spreads through networks, algorithmic amplification, and shares across platforms. Users see the misinformation shared by friends, making it appear more credible. Platforms amplify engagement-driving content regardless of accuracy.

This means that even when platforms claim to be fighting misinformation, their economic incentives work against effective suppression. Misinformation drives engagement—people share false stories, comment on them, argue about them. Removing misinformation reduces engagement. From a platform perspective, misinformation is valuable content that keeps users active and returning to the platform. Suppressing it conflicts with platform interests.

Moreover, determining misinformation is inherently political. What one side calls misinformation, the other calls suppressed truth. Removing stories about election procedures might be labeled as fighting misinformation or suppressing legitimate questions about election integrity, depending on your perspective. This political ambiguity gives platforms cover to suppress whatever information the government pressure them to suppress, framing it as fighting misinformation.

The Information Environment as Control Mechanism

When social media dominates news consumption and platforms are consolidated under political control, the information environment becomes a control mechanism. This isn't about preventing any particular message from spreading—it's about shaping what the public understands about reality itself.

Consider immigration policy. If social media platforms are controlled by people and forces opposed to immigration, and they algorithmically amplify content that portrays immigrants negatively while suppressing counter-narratives, the public information environment will skew toward anti-immigration perspectives. This isn't necessarily because individual stories are false. It's because of cumulative emphasis and suppression—what stories are visible, which are highlighted, whose experts are platformed, which arguments are amplified.

The public ends up with a systematically distorted view of reality that benefits those controlling the platforms. This is far more powerful than suppressing individual dissidents or blocking specific speech. It's shaping the entire information environment to support preferred narratives and suppress alternatives.

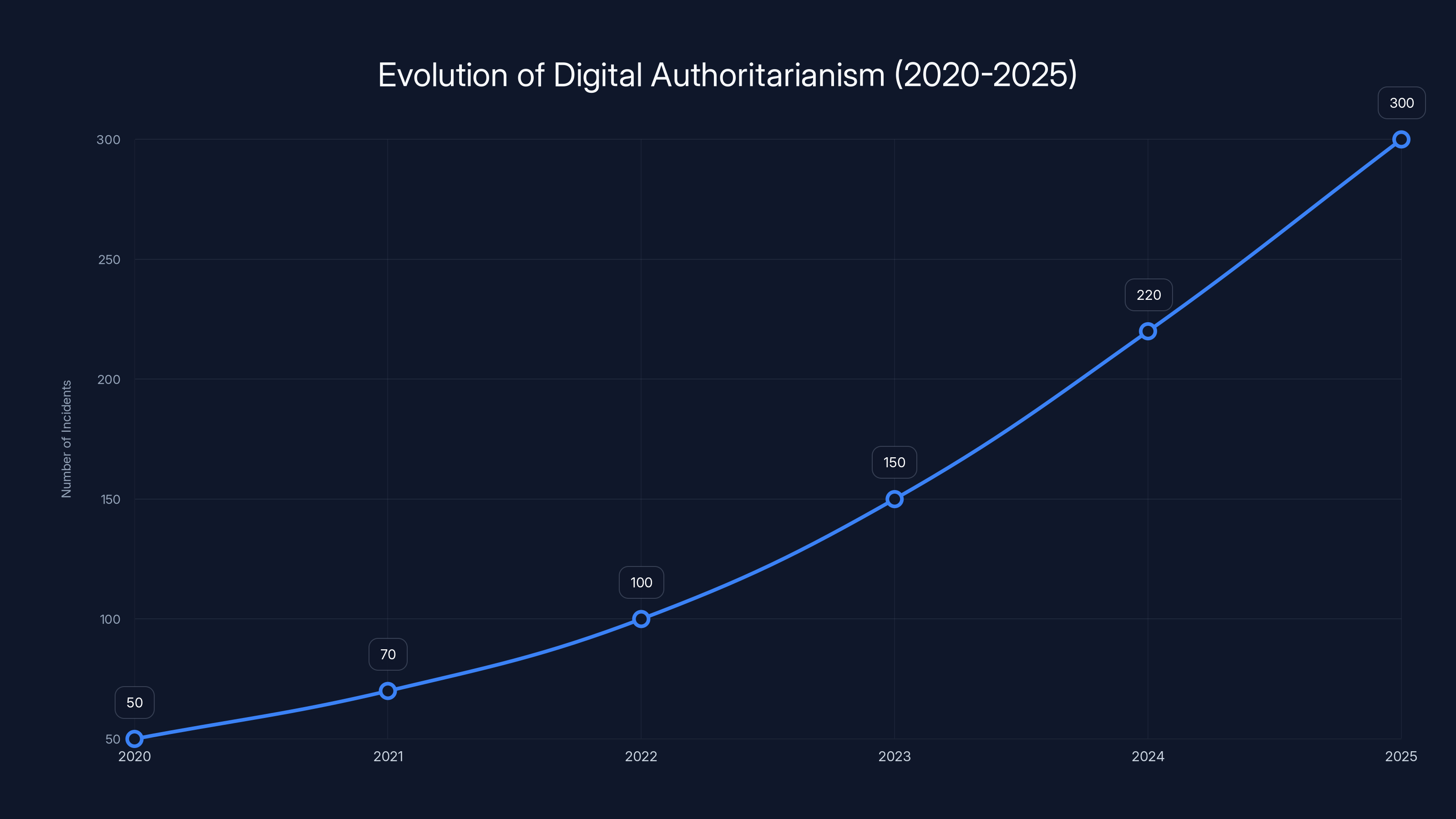

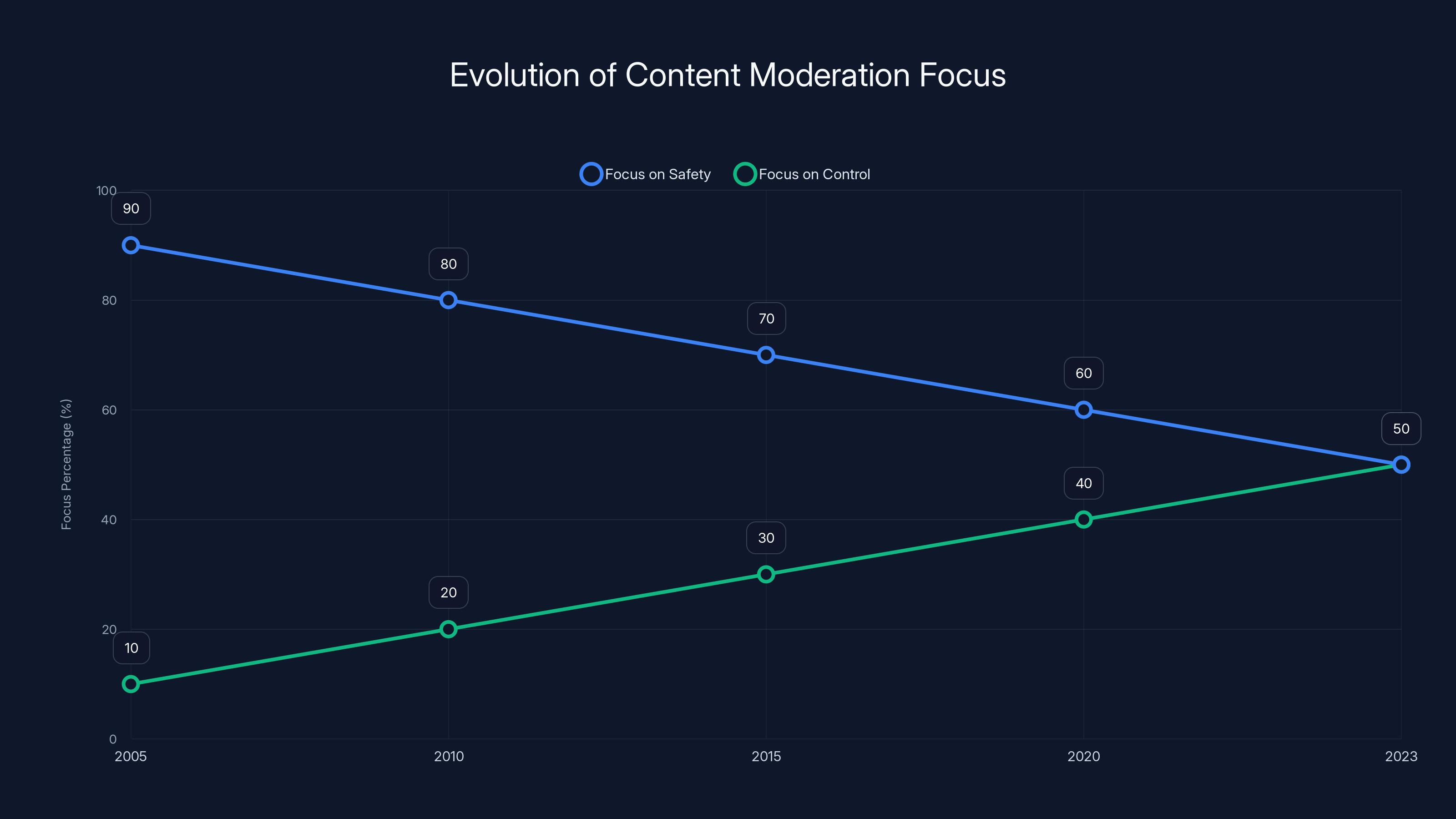

The line chart illustrates the estimated increase in digital speech suppression incidents from 2020 to 2025, highlighting 2025 as a significant turning point. Estimated data.

Algorithmic Suppression: The Invisible Mechanism

How Algorithms Suppress Without Removal

Most speech suppression on social media doesn't involve content removal. Instead, it works through algorithmic visibility control. A post might not violate any policies and might remain on the platform, but its visibility is reduced through algorithmic changes. The poster's reach drops dramatically, limiting who sees their content. From the poster's perspective, they're still able to post, so there's no obvious censorship. But they're effectively silenced—their speech reaches no one.

Algorithmic suppression is preferable to removal from a government perspective. Removal creates visible censorship that can generate backlash and martyrdom. When someone's content is removed, they know it—they can document it, complain about it, and potentially challenge it legally. When visibility is algorithmically reduced, the suppression is invisible. The person doesn't know they're being suppressed; they just notice that nobody's engaging with their posts. They might blame their lack of engagement on bad timing or uninteresting content, never realizing they're being algorithmically suppressed.

Moreover, algorithmic suppression can be plausibly denied. Platforms can claim they're making recommendations based on user engagement and quality—that certain content simply doesn't resonate with users. The algorithm appears neutral, not political. The fact that the algorithm consistently reduces visibility for speech the government disfavors while amplifying speech the government supports appears to be coincidence, not coordination.

The Black Box Problem

Algorithms are famously opaque. Platforms don't fully disclose how their recommendation systems work. Users can't see the decisions being made about their content visibility. Researchers can't systematically study algorithmic bias. Regulators can't effectively oversee algorithmic decisions. This opacity is justified as necessary to prevent gaming the system—if people knew how to game the algorithm, they could manipulate their visibility.

But the opacity also prevents accountability. If an algorithm suppresses speech in a politically skewed way, proving it is nearly impossible. Platforms can claim the algorithm is neutral, based purely on engagement and quality metrics. Without access to algorithmic internals, critics can't prove otherwise. The black box nature of algorithms becomes a shield against accusations of political bias.

Moreover, algorithms can be modified without the public knowing. A platform can change its recommendation system tomorrow, significantly altering whose voices are amplified and whose are suppressed. Users won't know the change happened. Researchers won't be able to study it. But the political effects could be substantial. Governments and platforms can coordinate algorithmic changes that alter the information environment in favor of preferred narratives, with no public knowledge or accountability.

The Feedback Loop Between Government Pressure and Algorithmic Suppression

Government pressure influences algorithmic suppression through multiple channels. Platforms might modify algorithms to suppress speech the government opposes, framing it as responding to user feedback or improving content quality. Government officials might appear at platform policy meetings and discuss concerning speech trends, implying that platforms should suppress such speech. Platform executives might anticipate government preferences and modify algorithms preemptively, avoiding explicit pressure by demonstrating voluntary compliance.

Once government-influenced algorithmic suppression begins, it creates self-reinforcing dynamics. Suppressed speech gets less visibility, accumulates less engagement, and can be pointed to as low-quality content that the algorithm correctly suppressed. The fact that suppression reduced engagement appears to justify continued suppression. The political bias becomes invisible behind the appearance of neutral quality judgments.

This creates a feedback loop where government pressure, algorithmic suppression, and platform policies reinforce each other. Government suggests that certain speech is problematic. Platforms modify algorithms to suppress it. The suppression reduces visibility and engagement for that speech. The reduced engagement is cited as evidence that the speech is low-quality and doesn't resonate with users. Further algorithmic suppression appears justified. The political origin of suppression becomes hidden behind layers of technical justification.

The Legal Framework Inadequacy: How Constitutional Law Failed to Adapt

The First Amendment's Limited Scope

The First Amendment protects speech from government suppression, but it applies only to government action, not private action. When private companies moderate speech on their platforms, they're not violating the First Amendment. This doctrine made sense when communication alternatives existed—if Facebook suppressed your speech, you could publish in other forums or on your own website. The First Amendment wasn't needed because market competition and technological alternatives provided checks on private power.

But when platforms became monopolistic gatekeepers, this legal framework failed. The alternatives that justified narrow First Amendment protection disappeared. A person suppressed on all major social media platforms has nowhere else to go that could reach significant audiences. The platforms have become essential infrastructure for public discourse, yet they remain legally private entities free to suppress whatever speech they choose.

Constitutional lawyers and scholars recognized this gap years ago. If platforms became so central to public discourse that they functioned as "digital commons," they argued, perhaps First Amendment protections should extend to them. Perhaps the government couldn't use platforms to suppress speech. Perhaps platforms couldn't suppress speech in ways that undermined democratic discourse. Yet these arguments made no progress in courts or legislatures. Platforms remained legally private, free to suppress speech, while performing functions traditionally associated with public forums.

The State Action Doctrine Problem

One potential legal avenue is state action doctrine. If government pressure causes a private platform to suppress speech, can that suppression be challenged as unconstitutional government action? The Supreme Court has occasionally found that government pressure effectively converted private action into government action warranting constitutional protection.

But applying state action doctrine to platforms is difficult. First, proving government pressure requires documenting what would typically remain confidential. The Department of Justice suggesting to Apple that it remove an app is informal coordination that leaves minimal paper trail. Second, the line between permissible government suggestion and impermissible coercion is unclear. Suggesting that a platform might face regulatory problems if it doesn't suppress speech is different from explicitly ordering suppression, yet it might be equally effective in producing compliance.

Third, platforms have legitimate reasons to moderate speech that don't depend on government pressure. Even without government interference, platforms might remove anti-ICE apps if they genuinely believed that law enforcement officer safety was important. Proving that government pressure, not independent judgment, drove the decision is extremely difficult. Platforms can always claim they made independent moderation decisions that happened to align with government preferences.

The Inadequate Remedies for Platform Suppression

Even if speech suppression on platforms violates constitutional rights, remedies are inadequate. No government agency effectively monitors or enforces platform compliance with free speech principles. The FCC regulates some broadcast media but has no authority over social media. The Federal Trade Commission can take action for deceptive practices but not for speech suppression. Congress has shown no willingness to regulate platform speech moderation, fearing that doing so would require government to mandate speech—another constitutional problem.

Private litigation is the main remedy, but it's expensive and slow. Joshua Aaron can sue Apple, but the litigation will take years and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Even if he wins, the remedy is uncertain—courts might order Apple to restore his app, but Apple could impose other barriers or modify the app before restoration. Individual lawsuits can't address systemic suppression across all platforms.

Moreover, most people suppressed on platforms don't have the resources for litigation. They can't prove their speech was suppressed, can't identify the specific government pressure that motivated the suppression, and can't afford lawyers to pursue claims. The legal system effectively provides remedy only for well-resourced litigants, making it inadequate as a check on platform suppression.

Regulatory threats and antitrust concerns are the most effective government pressure mechanisms, with high impact scores. Estimated data.

The Coordination Problem: Implicit vs. Explicit Collaboration

How Coordination Happens Without Explicit Orders

One of the most challenging aspects of understanding digital authoritarianism is that it doesn't require explicit coordination. Government officials don't need to call platform executives and order them to suppress speech. The system works through implicit understandings and aligned interests.

Government officials understand that platforms want to avoid regulatory trouble. When officials suggest that certain speech is problematic or indicate that platforms should be concerned about particular topics, platforms understand the message. They can implement suppression while claiming they're making independent decisions. Neither side needs to explicitly acknowledge the coordination.

Moreover, platforms have their own interests in suppressing certain speech. Platforms want to avoid controversy, maintain advertiser support, and prevent regulatory problems. Speech that antagonizes government, advertisers, or mainstream media can be suppressed not because government demands it but because suppression serves platform interests. When government interests and platform interests align, coordination happens naturally without anyone needing to order it.

This is particularly effective because it's deniable. If explicit coordination occurred—if a government official ordered a platform to suppress speech—that would be visible and potentially illegal. But when suppression happens through the implicit interplay of government pressure and platform interests, it appears natural and consensual.

The Revolving Door Facilitation of Coordination

Personnel movement between government and platforms facilitates coordination. Platform employees who have worked in government understand how government operates and what officials care about. Government officials who came from platforms understand platform capabilities and constraints. These informal networks enable coordination that doesn't require explicit communication.

A government official might know someone who works at a platform. They might discuss concerning speech trends in informal conversation. The platform employee understands that addressing the concerns would be appreciated. The conversation never involves explicit ordering or coercion, but it produces results. Without documentation, it's impossible to prove coordination occurred.

This revolving door also creates cultural alignment. People who work in both government and platforms develop shared perspectives about what speech is problematic and what role platforms should play in addressing it. These shared perspectives facilitate coordination because both sides want similar outcomes. They're not collaborating against their will; they're voluntarily pursuing aligned objectives.

The Information Asymmetry Enabling Coordination

Coordination is facilitated by dramatic information asymmetry. Platforms know far more about their own operations, algorithms, and capabilities than government knows. Government knows more about its regulatory authorities and enforcement capabilities than platforms fully understand. Neither side has complete information.

This asymmetry enables coordination through suggestion. Government can suggest that certain speech is concerning without knowing exactly how platforms could suppress it. Platforms can suppress it through mechanisms the government doesn't understand. Both sides benefit without needing to coordinate explicitly on methods. The government gets suppression without having to explain exactly what it wants. Platforms get government satisfaction without having to acknowledge they're suppressing speech in response to government pressure.

This information asymmetry also makes it nearly impossible for outsiders to understand what coordination is occurring. Researchers studying platform operations can't see government communications. Journalists investigating government actions can't get platform data. The public can't understand the full scope of coordination because that coordination is distributed across multiple institutions with asymmetric information.

The Chilling Effect: How Suppression Creates Self-Censorship

From Explicit Suppression to Internalized Restriction

The most effective form of speech suppression is self-censorship. If people suppress their own speech, platforms don't need to remove it. Government doesn't need to pressure platforms. The system maintains control without requiring active suppression.

Chilling effects work by creating costs for certain speech. If journalists are sued for critical reporting, other journalists become more cautious. If immigrants are deported for political organizing, other immigrants self-censor. If platform users see their posts algorithmically suppressed, they modify what they post. Over time, the most costly speech disappears not because platforms removed it but because people stopped creating it.

The brilliant aspect of the system from a suppression perspective is that it appears to respect freedom. Nobody's speech is formally banned. People can technically say whatever they want. But the costs of certain speech make it impractical. This appears like free choice—people choosing not to speak—rather than coerced suppression.

Yet it's suppression nonetheless. The speech that disappears would have been created if costs weren't imposed. The silence is enforced through financial penalty, reputation risk, legal jeopardy, or algorithmic invisibility. From a society perspective, important speech is suppressed not by force but by making it too costly to produce.

The Geographic and Temporal Spread of Chilling Effects

Chilling effects spread beyond the directly targeted speakers. When journalists are sued for reporting, other journalists become cautious. When immigration organizers face deportation, other activists reduce their work. When users see content algorithmically suppressed, they adjust what they post. The suppression of individual speakers creates a chilling effect that suppresses speech throughout networks.

Moreover, chilling effects persist even if particular suppression actions are reversed. If a lawsuit against a journalist is dismissed, other journalists remain cautious—the demonstration of government willingness to litigate has lasting impact. If a suppressed post is restored, the poster remains aware that posts can be suppressed, potentially affecting future posting. The threat of suppression becomes as effective as actual suppression.

Chilling effects also spread through time. When a government demonstrates its willingness to suppress certain speech in a particular way, people learn to avoid that speech. Journalists learn what reporting will be litigated. Immigrants learn what organizing will be targeted. Users learn what posts get algorithmically suppressed. Over time, people develop sophisticated understanding of what speech is risky and modify behavior accordingly.

The Internalization of Suppression

As chilling effects spread and persist, people internalize the restrictions. They develop norms around what speech is safe and what's risky. They learn institutional rules about what can be criticized and what's protected. They model their speech on what they observe being tolerated. Eventually, people restrict their own speech without any external pressure—they've absorbed the restrictions into their own thinking about what's appropriate.

This internalized suppression is particularly effective because it requires no ongoing enforcement. Once people have learned the boundaries and incorporated them into their thinking, they need not be reminded. The system maintains control through education rather than force. People aren't suppressed; they're socialized into restricted speech.

More troublingly, people stop recognizing their own suppression as suppression. They think they're choosing not to speak about certain topics because those topics are offensive, dangerous, or inappropriate. They don't recognize that their sense of what's appropriate has been shaped by exposure to suppression and chilling effects. Their restriction appears to be their own judgment rather than coerced compliance.

Estimated data shows a gradual shift in content moderation focus from primarily ensuring user safety to increasingly exerting control over content. This reflects the growing complexity and politicization of moderation decisions.

The Democratic Crisis: Speech Suppression and Authoritarian Drift

How Speech Suppression Enables Authoritarian Governance

Free speech is foundational to democracy. Democratic decision-making requires citizens to have access to diverse information, the ability to discuss and criticize government, and the capacity to organize opposition to government policies. When speech is suppressed, these democratic functions deteriorate.

Authoritarian governments suppress speech to eliminate criticism and opposition. By controlling what information citizens receive, authoritarians can prevent people from understanding threats to their liberty. By suppressing organization and criticism, authoritarians prevent the formation of political opposition. By controlling the information environment, authoritarians can maintain power despite causing substantial harm.

What's remarkable about 2025 is that these authoritarian techniques are being deployed in a nominally democratic system. The mechanisms are different from classic authoritarian suppression—no secret police knocking on doors, no publicly announced bans on speech. Instead, suppression works through platform moderation, algorithmic control, and regulatory pressure. But the effect is similar: critics are silenced, opposition is suppressed, the information environment is controlled to benefit those in power.

This creates what some call soft authoritarianism—suppression that achieves authoritarian control without the overt repression that would trigger resistance. Citizens aren't aware they're being oppressed. They think suppressed speech is being removed for legitimate safety reasons. They believe the information environment is accurate. They don't recognize that opposition to government policies is being systematically suppressed. The authoritarian control is invisible because it operates through mechanisms that seem neutral and apolitical.

The Erosion of Democratic Institutions

As speech suppression expands, democratic institutions erode. Investigative journalism deteriorates when journalists fear litigation. Civic engagement declines when people self-censor about politics. Organized opposition becomes difficult when platforms suppress organizing. The institutional capacity for democracy—the ability of citizens to deliberate, organize, and hold government accountable—weakens.

Moreover, suppression of opposition speech removes constraints on government power. Governments are typically constrained by the threat of political opposition—the knowledge that voters can organize and remove them. When opposition is suppressed, this constraint disappears. Government can act without fear of electoral consequences because opposition to government action is suppressed before it can develop.

This creates a vicious cycle. Government suppresses opposition. The suppression removes electoral constraints. Government acts without opposition. The absence of opposition removes the political consequences for suppression. Government feels freer to suppress more speech and act more autocratically. Democratic governance becomes progressively more difficult.

The Irreversibility Problem

Once suppression infrastructure is built and normalized, it's extremely difficult to reverse. Platforms have invested in moderation systems, trained moderators in suppression policies, and built business models around content control. Reversing this would require substantial change. Government has shown it's willing to pressure platforms and suppress speech. Reversing this would require political change.

Moreover, suppression infrastructure can be repurposed. The systems built to suppress anti-ICE speech can be used to suppress any dissent. The regulatory threats used to pressure Apple can be used to pressure other platforms. The legal mechanisms used against journalists can be used against any critic. Once installed, suppression infrastructure is available to be used against any speaker.

This means that reestablishing free speech after suppression infrastructure is normalized is extremely difficult. Restoring suppressed content doesn't remove the threat of future suppression. Changing government officials doesn't eliminate the infrastructure they built. Breaking up platforms might destroy communication networks faster than replacing them with better alternatives. The suppression infrastructure, once built, becomes a permanent feature of the system.

Technical Solutions and Their Limitations

Decentralized Platforms as an Alternative

One proposed solution to centralized platform control is decentralized social media—platforms owned and operated by users rather than corporations. Systems like Mastodon, Bluesky, and others operate on decentralized models where no single entity controls the entire network. Users can operate their own servers, choose their own moderation policies, and move between servers if unsatisfied.

Decentralized platforms offer genuine advantages. They eliminate the single point of control that enables systematic suppression. They distribute power so that suppressing speech requires coordination across multiple independent operators rather than control of a single corporation. They give users more agency in choosing what speech to be exposed to rather than accepting algorithmic curation.

However, decentralized platforms face significant obstacles. First, they lack the network effects that make centralized platforms valuable. A decentralized social media network with 10,000 users has less value than a centralized platform with billions of users. Most users prefer to be on platforms where they can reach the most people, even if those platforms aren't optimal. Second, they require more technical sophistication from users. Choosing servers and understanding federation is complicated for non-technical people. Third, they lack the funding and corporate support that centralized platforms have, making it difficult to build competitive features and scale to millions of users.

Most importantly, even if decentralized platforms became competitive with centralized ones, governments could still pressure them. If a decentralized platform's primary developer is in the US, the government could threaten enforcement action against that developer. If a decentralized platform's funding comes from US investors, the government could regulate those investors. Decentralization helps but doesn't eliminate government pressure.

Encryption and End-to-End Communication

Another proposed solution is end-to-end encrypted communication where platforms can't see what users are communicating. If platforms can't see the content, they can't suppress it. Encryption shifts power from platforms to users by making platform moderation impossible.

End-to-end encryption does provide real benefits for privacy and security. But it doesn't solve all problems. First, encryption doesn't prevent algorithmic suppression of visibility—even encrypted content can be algorithmically suppressed from users' feeds. Second, encryption doesn't prevent government pressure. Governments can still pressure platforms to require encryption backdoors, allowing government surveillance. Third, encryption doesn't prevent platform pressure on users—platforms can still require certain behaviors, block certain accounts, or control access.

Moreover, full encryption creates its own problems. Platforms can't moderate content even if they want to. This means encrypted platforms can become havens for illegal content, abuse, and harassment. It also means lost messages if encryption keys are lost and content can't be recovered. Encryption is powerful but not a complete solution to platform control.

Interoperability and Portability

A third proposed solution is interoperability—allowing users to move between platforms while maintaining connections and communities. If you could leave Facebook while keeping your followers and maintaining access to Facebook users, platform monopoly power would diminish. Users could move to better platforms without abandoning their networks.

Interoperability could genuinely reduce platform power by creating competitive pressure. Platforms that suppress speech would lose users to alternative platforms. This would require platforms to be more cautious about suppression to avoid losing users. Interoperability could also reduce switching costs—if you can move between platforms without losing networks, you're not locked in to particular platforms.

However, interoperability faces technical and structural challenges. Platforms have invested in proprietary systems and aren't eager to share. Interoperability would require coordination across platforms with different technical standards. User networks are valuable assets that platforms want to control. Mandating interoperability would require regulatory intervention that faces political obstacles.

Moreover, interoperability doesn't solve government pressure. Even if users could move between interoperable platforms, governments could pressure all platforms simultaneously. If every major platform participates in interoperability, suppressing speech across all of them would suppress it everywhere. Interoperability helps users compete with platforms but doesn't solve the problem of government-coordinated suppression.

Regulatory Approaches and Their Challenges

The Digital Services Acts and Content Moderation Regulation

Europe has taken a regulatory approach to platform power through the Digital Services Act, which requires platforms to moderate illegal content, provide transparency about moderation decisions, and allow users to appeal removals. Similar legislation has been proposed in the US. The idea is to regulate platforms so they're accountable for moderation decisions while preventing censorship.

These regulations offer benefits—they create transparency and appeal mechanisms that don't exist in current platform governance. They establish that platforms have responsibilities regarding content moderation. They create some accountability for suppression. But they also have substantial limitations.

First, regulation can be weaponized. If government can pressure regulators, it can use regulation to mandate suppression. The Digital Services Act requires moderation of illegal content, but defining illegality is political. If government can pressure regulators to define certain speech as illegal, regulation becomes a tool of suppression. Second, regulation is difficult to enforce against well-resourced platforms. Platforms can engage in regulatory capture, influencing regulators to adopt favorable rules. Third, regulation can stifle innovation and speech by requiring moderation that platforms can't provide without restricting speech.

Most importantly, regulation can't solve the fundamental problem: government pressure. If government is pressuring platforms to suppress speech, no amount of regulation requiring transparency and appeal mechanisms will prevent suppression. Transparency doesn't help if suppression is happening through government pressure rather than platform policy. Appeals don't help if government pressure overrides independent judgment.

Antitrust Enforcement Against Platform Monopolies

Breaking up platform monopolies could reduce their power and eliminate the single points of control that enable systematic suppression. If Facebook, Google, and other platforms were broken into smaller competitors, no single entity would control the information environment. Users could move between platforms, creating competitive pressure against suppression.

Antitrust enforcement could be effective in limiting platform power. But it faces substantial political obstacles. Platforms are politically powerful, employing armies of lobbyists and contributing to political campaigns. Political leaders in both parties have relationships with platform executives. Breaking up platforms would be economically disruptive, affecting millions of users and billions of dollars. The political will to pursue antitrust enforcement against platforms is weak.

Moreover, breaking up platforms takes years. Litigation against platforms could take a decade or more. By the time antitrust enforcement occurs, the damage to speech suppression would be enormous. Additionally, breaking up platforms doesn't solve government pressure. Even smaller platforms can be pressured to suppress speech. Decentralized platforms can be coordinated to suppress simultaneously. Breaking up platforms helps but doesn't fundamentally solve the problem of government coordination with whoever controls platforms.

First Amendment Reform and State Action Doctrine Expansion

Constitutional reform could expand First Amendment protections to apply to platforms. If platforms were treated as state actors, they couldn't suppress speech the government disfavored even if nominally privately owned. This would provide direct constitutional protection against the suppression mechanisms discussed above.

Expanding state action doctrine would face substantial legal and political obstacles. The Supreme Court has generally narrowed state action doctrine, not expanded it. Treating platforms as state actors would be a dramatic reversal of precedent. Moreover, expanding state action to private companies would be economically disruptive, potentially requiring all private companies to provide First Amendment protections, not just platforms.

Constitutional amendment would be required for more fundamental reforms. But amending the Constitution is extremely difficult. It requires two-thirds majorities in both houses of Congress and ratification by three-fourths of states. Getting this level of consensus on anything is difficult. Getting it on speech regulation while the government is suppressing speech is politically impossible.

First Amendment reform is important but can't happen quickly enough to address current suppression. By the time constitutional changes occur, the suppression infrastructure would be deeply embedded.

International Implications and Global Authoritarianism

The Model for Other Authoritarian Systems

What's happening in the US with digital speech suppression is being studied by authoritarian governments worldwide. China's social credit system, Russia's speech suppression infrastructure, and other authoritarian controls represent earlier versions of what's emerging in the US. But the US approach is more sophisticated because it works through private companies rather than direct government control, making it less obviously authoritarian.

Authoritarian governments worldwide are learning from US suppression techniques. They're observing how platforms can be pressured to suppress speech. They're studying how algorithms can be modified to reduce visibility for disfavored content. They're noting how government and platform interests can align to suppress opposition. They're implementing similar systems in their own countries.

The irony is that the US, while claiming to champion democracy and free speech globally, is developing suppression infrastructure that other authoritarian systems can study and emulate. The sophisticated mechanisms the US has developed for suppressing speech aren't constrained to the US—they can be replicated globally. Democratic movements fighting authoritarianism worldwide will face not just crude suppression from their own governments but sophisticated suppression infrastructure based on the US model.

The Export of Suppression Technology

US technology companies export not just platforms but suppression infrastructure. When US companies build content moderation systems, those systems are available to authoritarian governments worldwide. When platforms develop algorithmic suppression mechanisms, those mechanisms can be adopted by other platforms operating under authoritarian control. When platforms develop methods of government coordination, those methods can be learned by authoritarian systems.

The globalization of platform power means that suppression infrastructure developed in the US is available globally. An authoritarian government can adopt Facebook's moderation systems, implement similar algorithms, and coordinate with government in similar ways. The US isn't just developing suppression infrastructure for itself—it's creating a global model for digital authoritarianism.

This is particularly troubling because the US has historically been a source of free speech values globally. Pro-democracy movements worldwide cite American free speech principles. When the US itself develops sophisticated suppression infrastructure, it undermines its credibility as a free speech advocate. It provides justification for authoritarian systems: if the US suppresses speech, why shouldn't we?

The Precedent for Global Free Speech Decline

The normalization of speech suppression in the US sets precedent for similar suppression globally. If platform suppression of speech is acceptable in the US, why shouldn't it be acceptable elsewhere? If government coordination with platforms is normal in the US, why shouldn't it be normal elsewhere? If regulatory threats to platforms are a normal tool of governance in the US, why shouldn't they be normal elsewhere?

The globalization of authoritarianism doesn't require all countries to develop independent suppression infrastructure. It simply requires them to observe what's possible and imitate. The US is demonstrating that systematic speech suppression can be achieved while maintaining the appearance of free speech and democracy. That demonstration has global impact.

Future historians may look back at 2025 as the beginning of a global authoritarian transition. Not because force was used but because free speech was hollowed out through technical means and government-platform coordination. The US, a historical advocate for free speech, pioneered suppression infrastructure that other countries adopted, leading to a global decline in free expression.

The Path Forward: What Needs to Change

Immediate Actions: Transparency and Accountability

Short-term changes that could begin addressing speech suppression include platform transparency and accountability. Platforms should be required to disclose moderation decisions, allow appeals, and publish regular reports on what content is removed and why. Users should have the right to understand why their speech was suppressed and to challenge suppression decisions.

Government pressure on platforms should be disclosed. Communications between government agencies and platforms about content moderation should be made public, subject to legitimate national security exceptions. Citizens should know when government is pressuring platforms to suppress speech. Public disclosure would create accountability and expose coordination that currently remains hidden.

Judicial review of platform moderation decisions should be available. If a platform removes content or suppresses visibility based on government pressure, the suppression should be judicially reviewable. Courts could determine whether government pressure violated First Amendment principles and order restoration of suppressed speech. This wouldn't require treating platforms as government actors but would create a mechanism to review government-influenced suppression.

These immediate actions are difficult but achievable. Transparency requires only disclosure—platforms already know what they're suppressing and how. Accountability requires only existing legal mechanisms. Judicial review requires only recognition that government-influenced suppression might violate the Constitution. These changes wouldn't eliminate speech suppression but would make it visible and subject to legal challenge.

Medium-Term Structural Changes: Decentralization and Competition

Medium-term changes should focus on reducing the concentration of platform power. Breaking up monopolistic platforms, promoting competing platforms, and developing interoperability standards would reduce the ability of any single entity to suppress speech comprehensively. Users could move between platforms, creating competitive pressure against suppression. Government would need to pressure multiple platforms simultaneously rather than controlling a single monopoly.

Regulatory frameworks should be developed that allow platforms to operate under diverse moderation philosophies. Instead of requiring all platforms to adopt identical moderation rules, regulations should allow platforms to choose different approaches, allowing users to select platforms aligned with their values. A platform prioritizing free expression could compete with platforms prioritizing content moderation. Users could choose which moderation philosophy they prefer rather than accepting the moderation imposed by monopolistic platforms.

Investment in alternative communication infrastructure should be prioritized. Rather than relying on commercial platforms, investment should develop publicly operated or cooperatively owned communication infrastructure where suppression would require democratic decision-making rather than corporate discretion. Public digital commons would ensure that communication infrastructure isn't controlled by private entities subject to government pressure.

These medium-term changes require regulatory and legislative action. They're achievable with political will but require overcoming platform resistance and regulatory capture. They would take years to implement but would meaningfully reduce suppression capacity.

Long-Term Systemic Changes: Constitutional and Cultural

Long-term solutions require constitutional and cultural changes recognizing that private platforms performing public functions need to respect free speech principles. This might involve expanding state action doctrine, amending the Constitution to extend First Amendment protections to platforms, or developing new legal frameworks specifically for platforms as essential communication infrastructure.

Culturally, society needs to recognize that speech suppression through platforms and algorithms is censorship even when technically private. When platforms suppress speech in response to government pressure, it's government censorship by proxy. When algorithms suppress speech based on political criteria, it's systematic suppression regardless of the mechanism. Recognizing these realities would allow legal and social accountability for suppression.

Education about algorithmic literacy and platform manipulation should be widespread. If citizens understood how algorithms control their information environment, they'd be better positioned to recognize and resist manipulation. Understanding how to identify and counter suppression would make suppression less effective.

More fundamentally, society needs to decide whether platforms should play the role they currently play in determining the information environment. Perhaps platforms shouldn't be news distribution mechanisms. Perhaps algorithms shouldn't determine public discourse. Perhaps platforms shouldn't mediate human communication. These are large questions without easy answers, but they need to be addressed.

FAQ

What is digital authoritarianism?

Digital authoritarianism refers to the use of technology platforms, algorithmic control, and digital infrastructure to suppress speech and control public discourse while maintaining the appearance of free expression. Unlike traditional authoritarianism that uses visible repression, digital authoritarianism operates through mechanisms that appear neutral and technical—content moderation policies, algorithmic visibility control, and platform design—making suppression invisible and difficult to challenge.

How does government pressure on platforms suppress speech?

Government agencies can suppress speech through implicit coordination with platforms rather than explicit orders. Regulatory threats, legal action, and suggestions about problematic content create incentives for platforms to suppress speech the government disfavors. Platforms can implement suppression through moderation policies and algorithms while claiming to make independent decisions, obscuring the government pressure that motivated the suppression.

What are the differences between content removal and algorithmic suppression?

Content removal involves platforms deleting posts or accounts, which is visible to the user. Algorithmic suppression reduces the visibility of content through recommendation systems—posts remain on platforms but don't appear to audiences. Algorithmic suppression is more effective from a control perspective because users don't know their speech is being suppressed, so they don't recognize censorship or challenge it.

Why is platform consolidation a free speech problem?

When a small number of corporations control most social media platforms, no meaningful alternatives exist for suppressed speakers. If one platform suppresses your speech, you can move to another platform only if that platform also hasn't suppressed you. When all major platforms are under unified control or aligned politically, suppression becomes unavoidable. This concentration of power eliminates the competition and alternatives that previously protected speech.

How do chilling effects suppress speech without visible censorship?

Chilling effects make speech costly or risky, causing people to self-censor without platforms or government needing to suppress speech. When journalists are sued for reporting, others become cautious. When users see posts algorithmically suppressed, they adjust what they post. When activists face legal threats, they reduce organizing. The threat of suppression becomes as effective as actual suppression in reducing speech.

What legal frameworks currently protect speech on private platforms?

Currently, the First Amendment doesn't protect speech on private platforms—it restricts only government action. Private companies have broad legal authority to suppress whatever speech they choose. Some proposed solutions include treating platforms as state actors, expanding First Amendment doctrine to cover platforms, developing platform-specific regulations requiring transparency, and using antitrust enforcement to break up monopolistic platforms. However, none of these approaches have been fully implemented.

How can algorithmic suppression be detected and challenged?

Detecting algorithmic suppression is difficult because algorithms are opaque and constantly changing. Research can compare visibility for different types of content and look for patterns, but platforms don't disclose algorithmic details. Challenging suppression requires proving that algorithms suppress content based on political criteria rather than quality metrics—difficult without access to algorithmic internals. Transparency requirements and algorithmic audits could make detection and challenge more feasible.

What role do social media platforms play in news consumption?