Digital Consent is Broken: How to Fix It With Contextual Controls

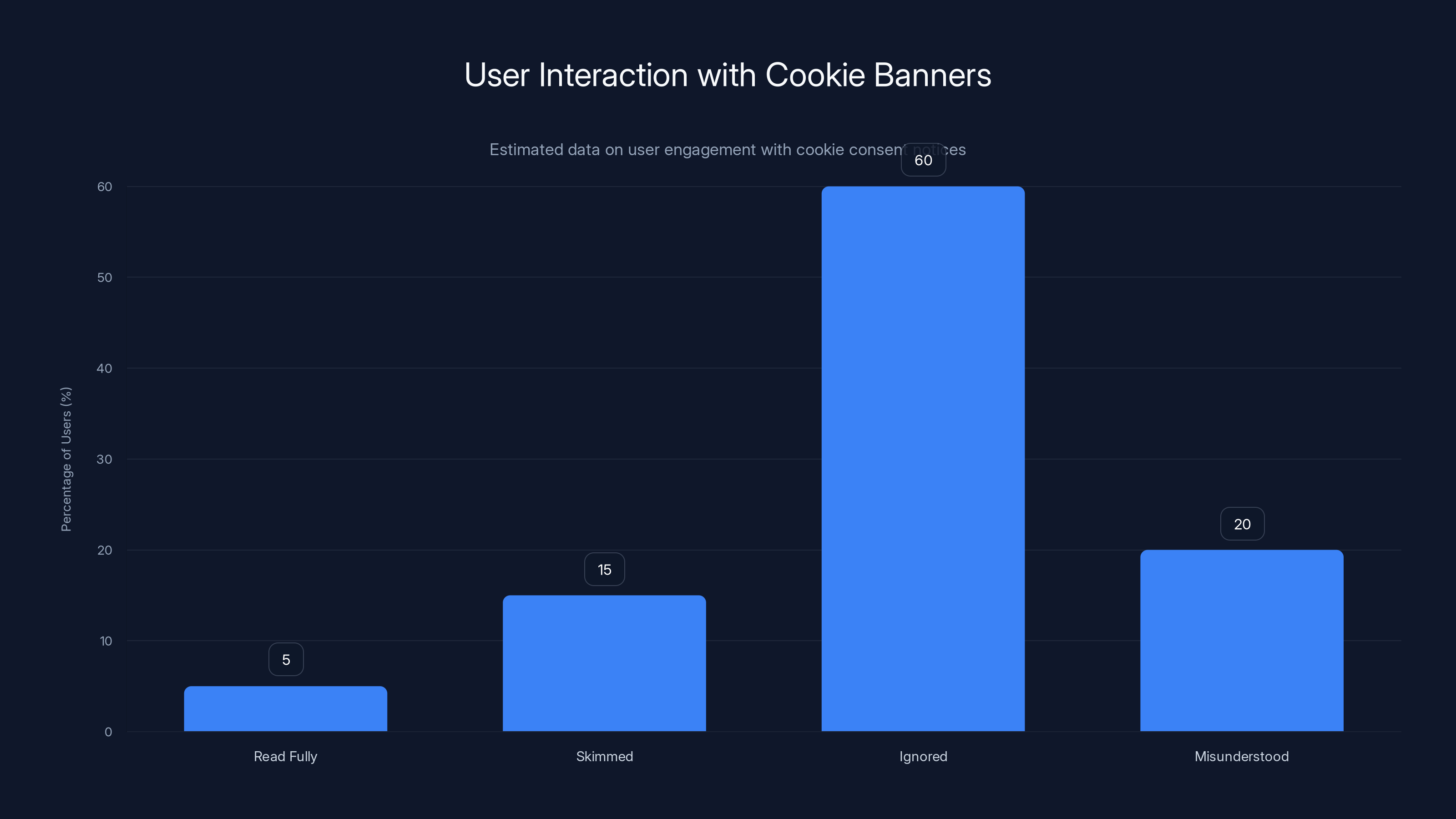

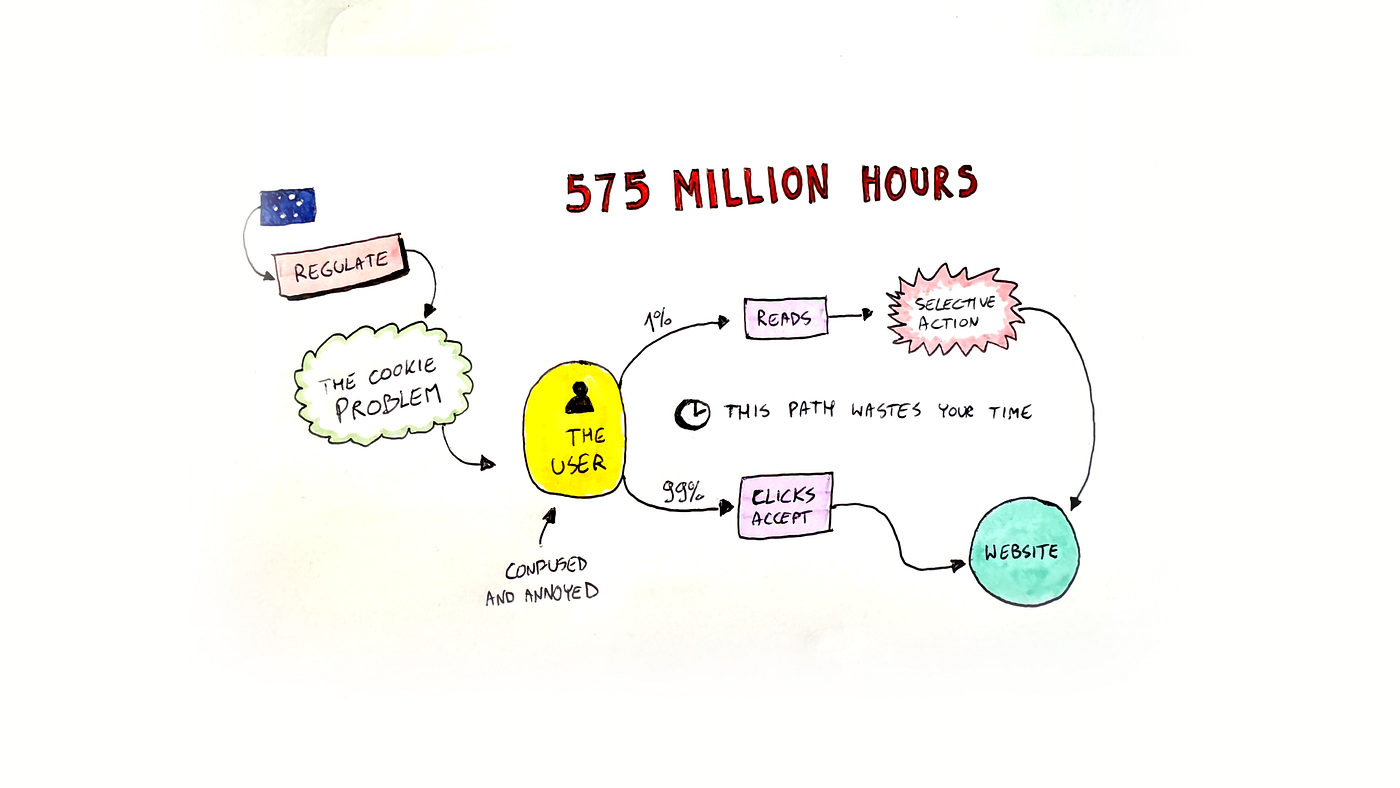

You've seen it a thousand times. A website loads, and before you can read a single article, a banner appears asking you to accept cookies. Most people don't even look at it. They just click "accept all" to get it out of the way. And that's exactly the problem.

Consent, as it exists today, isn't about giving people control over their data. It's about checking a legal box and moving on. The banner appears, you click, and the company records a "yes." But nothing changes. Your data still gets collected, shared, and sold the exact same way it would have if you'd said no.

This isn't accidental. It's the result of building consent systems for compliance, not for people.

TL; DR

- Consent is compliance theater: Cookie banners satisfy legal requirements but don't actually give users meaningful control over their data

- Consent must travel with data: Permissions need to be enforced across APIs, data warehouses, and third-party integrations, not just on the browser

- Contextual consent works better: Asking for permission at the moment of use, when value is clear, generates more meaningful and reliable consent

- Sensitivity emerges dynamically: Data that seems harmless individually can combine to reveal sensitive information without explicit disclosure

- Testing and proof matter: Organizations need continuous validation that user choices are actually being respected in real systems

- The fix requires infrastructure: Building consent that works requires changes to data architecture, analytics systems, and organizational processes

Estimated data shows that a majority of users (60%) ignore cookie banners, while only 5% read them fully. This highlights the ineffectiveness of cookie banners in obtaining informed consent.

Why Cookie Banners Failed at Consent

When privacy regulations like the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) first mandated explicit consent, companies deployed cookie banners as the quick solution. The logic was simple: show a message, collect a choice, record it, move on.

The problem is that this model was designed in the browser, for the browser. It worked when cookies were the primary privacy concern. But consent today is about far more than cookies. It's about data collection, retention, sharing, inference, and processing. A cookie banner can't possibly communicate all of that complexity in a way users actually understand.

In fact, research shows that most users don't read consent notices at all. They're cookie banner blind. The average person spends less than 10 seconds looking at these notices before making a choice, often without actually comprehending what they're agreeing to. Some never read them at all.

But here's what really breaks consent: even when a user makes a deliberate choice, even when they say no to cookies or opt out of data sharing, that choice doesn't actually propagate beyond the initial banner. A user clicks "reject all" on a website. A cookie is set recording that decision. Then data still leaves the device, gets sent to multiple ad platforms, processed through data management platforms, and monetized in real-time bidding auctions.

The user said no. But the company didn't actually honor that choice because the decision never made it past the browser.

That gap between user choice and actual system behavior is what makes consent feel broken. And it's not primarily a technology problem. It's an organizational one. Most companies built consent for compliance, not for operation. They have a privacy team that manages the banner, but that team doesn't own the data infrastructure, the marketing stack, or the analytics pipeline. So even if they wanted to honor user choices, they couldn't without massive coordination.

Consent became something you display, not something you enforce.

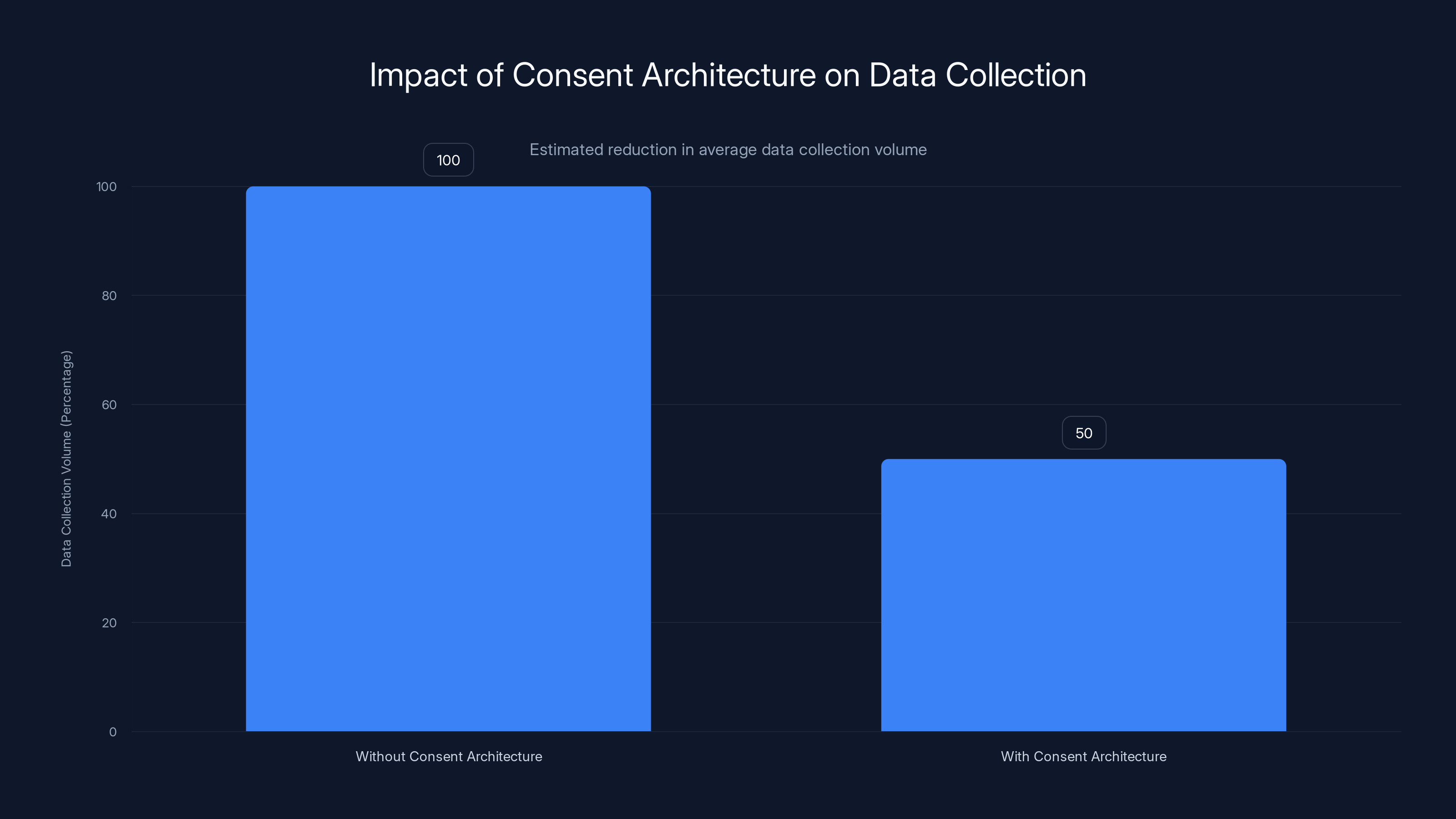

Implementing a true consent architecture can reduce data collection volume by 40-60%, highlighting unnecessary data collection practices. Estimated data.

Consent Has Grown Far Beyond Cookies

The word "cookies" has become almost meaningless in privacy discussions. When GDPR rolled out, cookies were the primary vector for tracking across the web. Set a cookie, track behavior, profit. That was the model.

But the privacy landscape has evolved dramatically. Today, websites can track users through pixels, server-side implementations, mobile SDKs, fingerprinting, email hashes, and dozens of other methods. Cookies are actually one of the least sophisticated tracking mechanisms now.

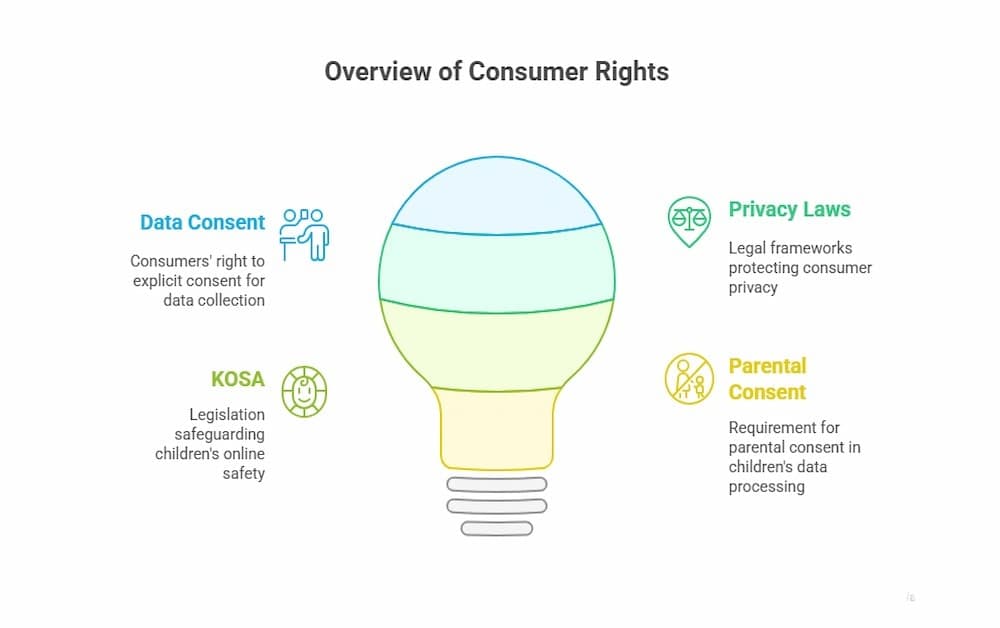

More importantly, privacy laws today aren't really about cookies anymore. They're about data collection writ large. The question regulators are asking isn't "Did you set a cookie?" It's "Why are you collecting this data? Who are you sharing it with? What are you inferring from it? How long are you keeping it?"

California's Consumer Privacy Act (CPRA), Virginia's Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA), and newer frameworks across the globe all share a common thread: they regulate data practices, not just cookies. They require transparency about collection, sharing, and use. They give consumers the right to access, delete, and opt out of certain uses. They impose responsibilities on companies to implement safeguards.

A cookie banner can't express any of this. It's the wrong tool for the job.

When an organization treats consent as purely a cookie consent problem, they miss the bigger picture. A user might opt out of "selling or sharing" data. But that message only touches the browser cookie management system. Pixels still fire. Server-side parameters still get collected. SDKs still transmit data to ad platforms. And that data, once sent, is legally possessed by the ad platform. The user said no. The cookie banner was set. But the practical reality is that the data still gets monetized.

The same applies to other data uses. A user might consent to analytics for site improvement. But if that consent doesn't travel through the analytics pipeline, if it doesn't restrict what parameters get sent, if it doesn't limit retention, if it doesn't prevent sharing with third-party analytics vendors, then consent is just theater.

Proper consent requires understanding what data actually leaves the system, where it goes, and who controls it. Then consent needs to be enforced at all those points.

The Architecture Problem: Consent Must Travel With Data

Here's the core technical problem that makes consent fail in practice: the choice a user makes on a website is usually recorded in one place (the consent management system), but the data that choice should control gets sent to dozens of other places.

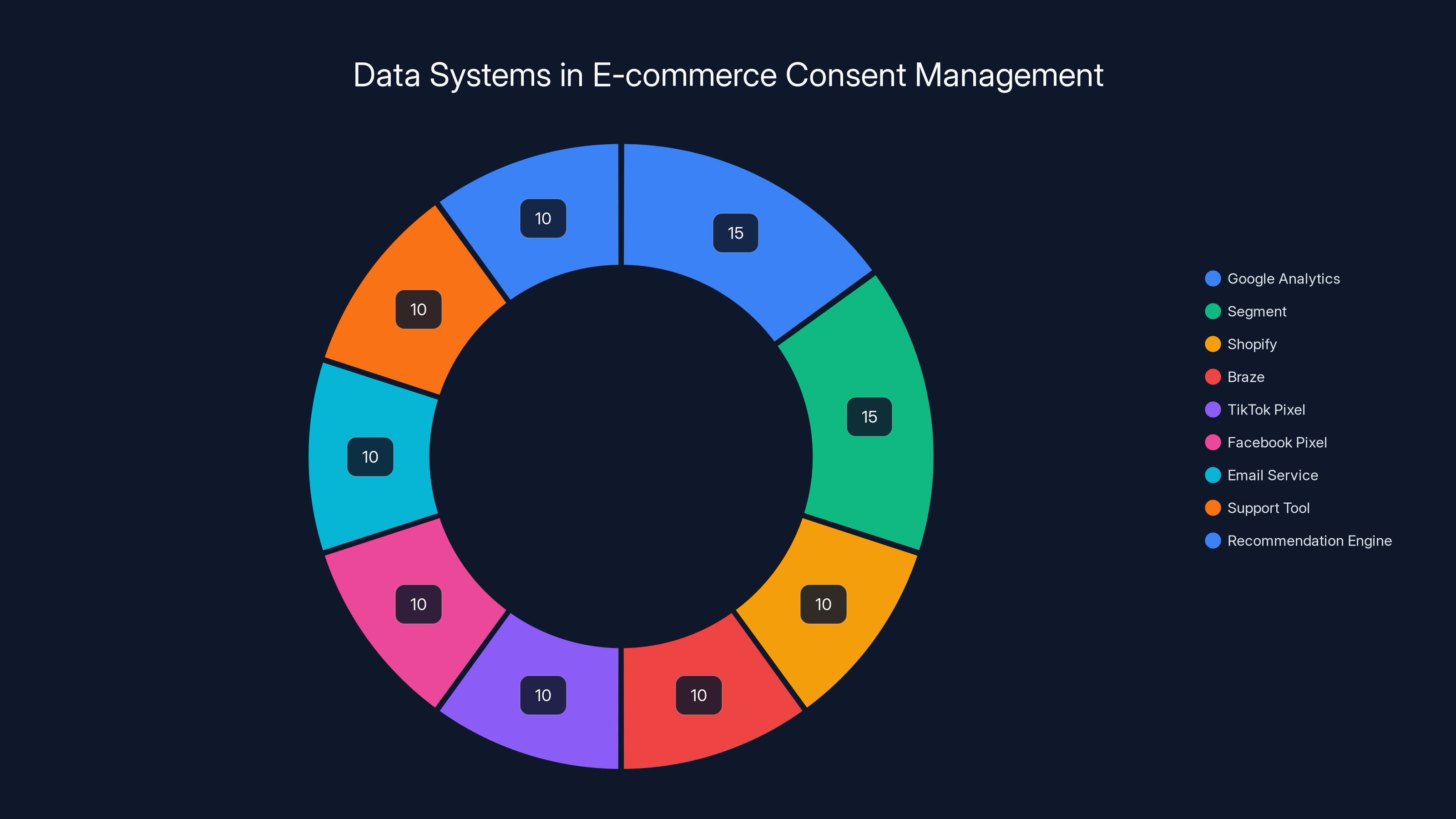

Imagine a user visits an e-commerce site. The site uses Google Analytics, Segment for a customer data platform, Shopify for the store, Braze for marketing automation, Tik Tok Pixel for ads, Facebook Pixel for ads, an email service provider, a customer support tool, and a third-party recommendation engine. That's eight different systems that might collect or receive data about this user's behavior.

When someone manages to navigate a consent banner and actually opt out of something, does that choice instantly propagate to all eight of those systems? Usually not. Some are enforced through the consent management platform removing tags from the page. Some are enforced through API calls that update preferences in the third-party system. Some aren't enforced at all, because the company doesn't have an integration to push that preference to the vendor.

So the user's choice is fragmented. It exists in the consent management system. It might exist in the CDP. It probably doesn't exist in the analytics tool, because no one built an integration for that. It definitely doesn't exist in the ad pixels, which fire independently of preference management.

This is why consent has to be architecturally baked into data flow, not bolted on afterward. The way to do that is with a centralized source of truth for permissions.

Organizations should maintain a system that says: User X consented to analytics on August 3. User X revoked that consent on September 14. User X consented to marketing on August 3 but with a 30-day retention window. User X has not consented to data sharing with third parties.

That record needs to be queryable by every system that touches that user's data. When data is sent to the analytics platform, the system should query: "Does this user have active analytics consent?" If yes, send the data. If no, don't. When the CDP prepares a segment for a marketing campaign, it should query: "Which users in this segment have active marketing consent?" and exclude the others.

When a user revokes consent, that central record updates instantly. From that moment forward, every downstream system sees the updated permission state and behaves accordingly. No manual updates. No delays. No inconsistency.

But this requires infrastructure that most organizations don't have. It requires a unified consent platform that can talk to analytics systems, CDPs, data warehouses, ad platforms, and marketing tools. It requires engineering effort to build those integrations. It requires processes to keep systems in sync.

Most companies find it easier to ignore the problem and hope users don't notice.

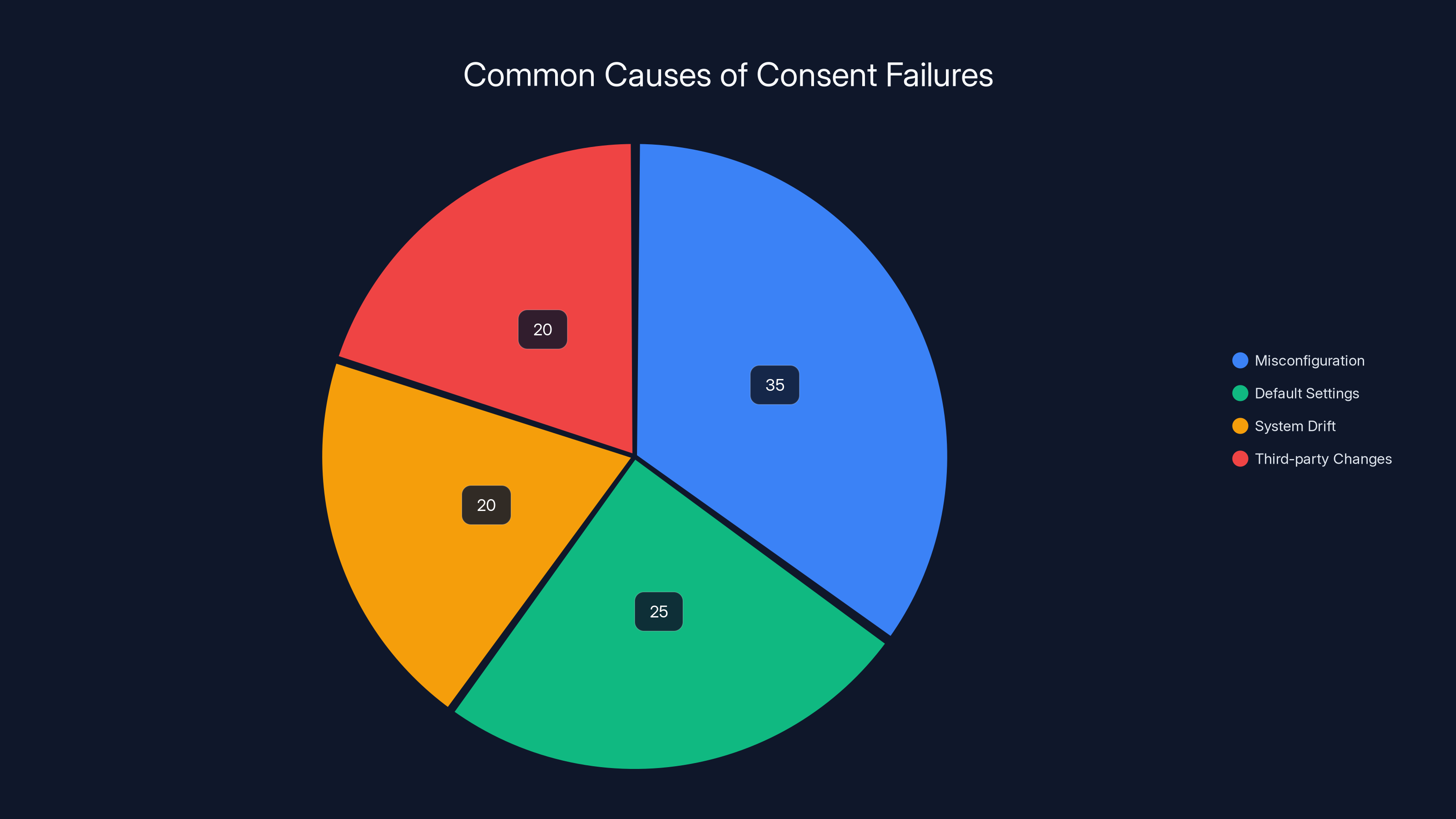

Misconfiguration is the leading cause of consent failures, followed by default settings and system drift. Estimated data based on industry insights.

Contextual Consent: Asking at the Right Moment

Here's something that seems obvious but almost never happens: asking for consent at the exact moment when the user understands what they're agreeing to.

Consider the typical website experience. A user lands on a site. Before they've read anything, before they've interacted with anything, a banner asks them to accept cookies. At this point, the user knows nothing about what data will be collected, why it will be collected, or who will see it. They know they want to read the article or check a product or get information. They don't know the technical details of the data collection infrastructure.

So they make a choice from ignorance. Accept, reject, or ignore. Either way, it's not an informed decision.

Contextual consent is the opposite. It asks for permission at the moment when context is clear and the value exchange is visible.

Example: A user is checking out on an e-commerce site. At the cart stage, you ask: "Would you like us to save your cart and send you a reminder if you abandon it?" Now the user understands exactly what data will be collected (cart contents, email), why it will be collected (reminder functionality), and what benefit they receive (not losing their cart). They can make an informed choice.

Another example: A user presses play on a video. The video player explains: "We'll collect analytics data about your viewing behavior to improve recommendations." The user sees the benefit immediately. They'll get better recommendations. And they understand exactly what's being tracked. They can consent or decline from an informed position.

Contextual consent has multiple advantages. First, it generates higher-quality consent. When users understand what they're agreeing to, they make more deliberate choices. Second, it allows for granularity. Instead of one global cookie acceptance that covers everything, permissions can be tied to specific purposes. Analytics consent is separate from marketing consent is separate from personalization consent. Third, it gives companies better legal defensibility. When a user consents to something while fully understanding it, that consent is much harder to challenge.

But contextual consent also requires a different technical and organizational approach. You can't bolt it on top of a traditional consent banner system. You need the infrastructure to manage multiple consent states tied to different purposes. You need to think through all the moments in a user journey where consent makes sense. You need to design those moments in ways that don't feel intrusive.

This is harder than a banner that appears on page load. But it's also more honest.

Sensitivity Isn't Always Obvious at the Collection Point

Most data privacy frameworks recognize certain information as explicitly sensitive: health information, financial data, precise location, biometric information. These are protected separately under most privacy laws. They require explicit consent, explicit deletion rights, and additional safeguards.

But here's the trap: sensitive information often emerges through inference and combination, not through explicit collection.

Consider these examples. A user searches for "bipolar disorder" on a website. That's not explicitly health information being collected. It's a search query. But it clearly reveals health status. A product view for "prenatal vitamins" isn't explicitly pregnancy data, but it strongly infers it. A referral from a specialized clinic website isn't explicitly medical, but it signals probable condition.

Take these individually and they might not seem sensitive. But combine them with other signals and the inferences become stronger. Search for "depression medication side effects" plus views of therapy booking sites plus visits to mental health forums equals a fairly clear signal of mental health challenges. That's sensitive information, even though none of the individual data points were collected as explicit health information.

Or consider location. A person's precise location (latitude and longitude) is regulated as sensitive. But you can infer fairly precise location from much less regulated data: Wi-Fi network names, which retail stores someone shops at, which restaurant they eat at. Combine enough of these signals and you have a location profile that's nearly as revealing as explicit GPS data.

The problem is that most consent frameworks only protect explicitly classified sensitive data. They don't account for sensitivity that emerges through combination and inference. A user might consent to analytics because they think it means "how many people visit the page." They don't realize it means their behavior can be analyzed in combination with other data to infer sensitive attributes.

This requires a more sophisticated approach to consent. Organizations need to classify not just the data they explicitly collect, but also the data that might be inferred from it and the combinations that create sensitivity. They need consent mechanisms that can account for these inferences. They need to be transparent about what can be inferred from the data they collect.

In practice, this often means being more conservative with consent. If collecting someone's search behavior could infer health status, treat it as if health data is being collected. If behavioral data could infer financial status, treat it as financial data for consent purposes.

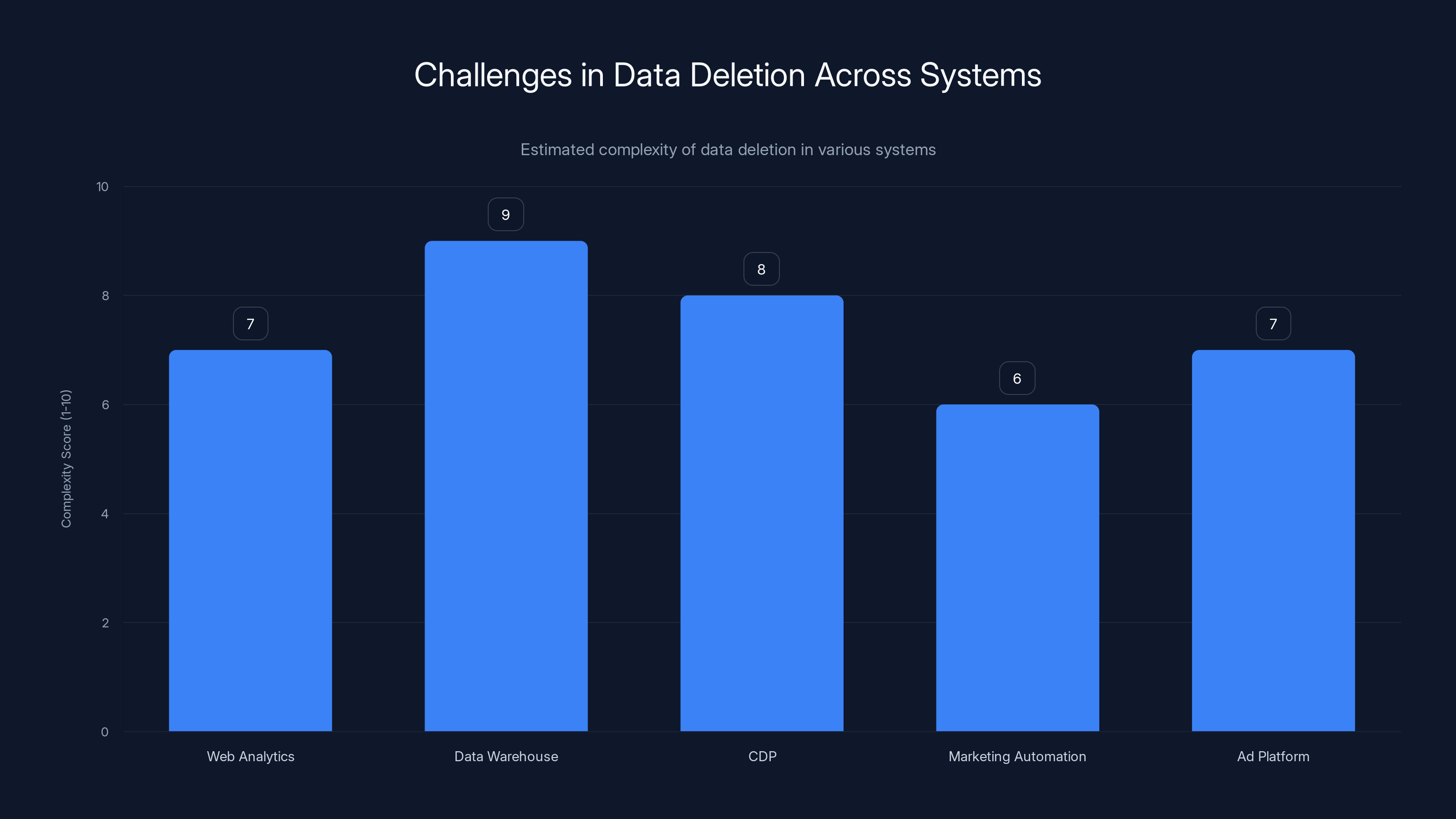

Data deletion complexity varies across systems, with data warehouses often presenting the highest challenge due to their central role in data storage and processing. (Estimated data)

Data Classification as a Prerequisite for Real Consent

Before you can meaningfully ask for consent, you need to know what data you're actually collecting.

This sounds basic, but it's where most organizations fail. Many companies don't have a clear inventory of what data their various systems collect. They've integrated dozens of tools over years. Each tool collects its own set of parameters. No one maintains a master list of what's actually going out.

Data classification is the process of cataloging this. You inventory all the data your systems collect. You categorize it by type (behavioral, personally identifiable, sensitive, inferred). You map it to purposes (analytics, marketing, personalization, fraud detection). You track where it's sent (which third parties receive what information). You assess sensitivity and regulatory implications.

Once you've done this, something interesting happens. You realize you're collecting far more than you thought. You're capturing information you don't even use. You're sharing data with vendors that don't need it. You're retaining information long past when it's useful.

This creates an opportunity. Instead of asking users to consent to "marketing" or "analytics" (categories so broad they're meaningless), you can ask for consent to specific purposes tied to specific data types. "We'll collect your product searches to improve product recommendations." "We'll collect your behavior to measure which content performs best." "We'll share your email and purchase history with our email marketing platform."

This is simultaneously more honest and more granular.

The classification process also reveals sensitive data that might have been invisible. You might discover that a particular data combination reveals health status, or financial situation, or political affiliation. You can then adjust your consent approach accordingly. Maybe that data doesn't need to be collected at all. Maybe it needs explicit consent. Maybe it needs to be processed differently.

Data classification also has practical benefits. Once you know what data you collect and where it goes, you can actually build automated systems to enforce consent. You can set up rules: "If user X has not consented to analytics, don't send these parameters to the analytics platform." Without classification, you're just guessing.

Consent Enforcement: From Promises to Proof

Here's a hard truth: most consent failures aren't caused by bad intentions. They're caused by misconfiguration, defaults, and drift.

A marketing platform adds a new data parameter by default in an update. Nobody notices. Now that parameter is being sent to every vendor, despite the fact that users never consented to it. A tracking tag is added to the site through a CMS plugin and nobody realizes it's running. A third-party vendor updates their implementation and starts collecting additional information. The consent system was never told about the new implementation.

These aren't conspiracies. They're the normal chaos of operating complex technology systems.

This is why consent needs enforcement mechanisms with continuous validation.

Instead of treating consent as a one-time decision (banner on load, checkbox checked, job done), organizations need to treat it like security testing. Just as companies run continuous tests to verify that their systems aren't vulnerable, they need continuous tests to verify that they're honoring user consent.

How does this work? Automated privacy testing simulates user journeys. Set a user profile with specific consent preferences (opted out of analytics, opted in to marketing, etc.). Run that user through the website and all the backend systems. Check whether disallowed tags fire. Verify whether disallowed data gets sent to disallowed platforms. Confirm whether user data is properly suppressed from disallowed processes.

This testing should run continuously, not once. Because systems change constantly. New vendors get added. Parameters get updated. Configurations shift. Without continuous verification, you can't know whether you're actually honoring consent.

This is resource-intensive. But it's the only way to move consent from a promise ("We respect your choices") to proof ("We can demonstrate that our systems behave according to your choices").

The benefit is that you can now produce evidence if regulators ask questions. You can show logs of testing. You can demonstrate that user preferences are being enforced. You can document exactly what happened when a user revoked consent. That evidence is far more valuable than promises.

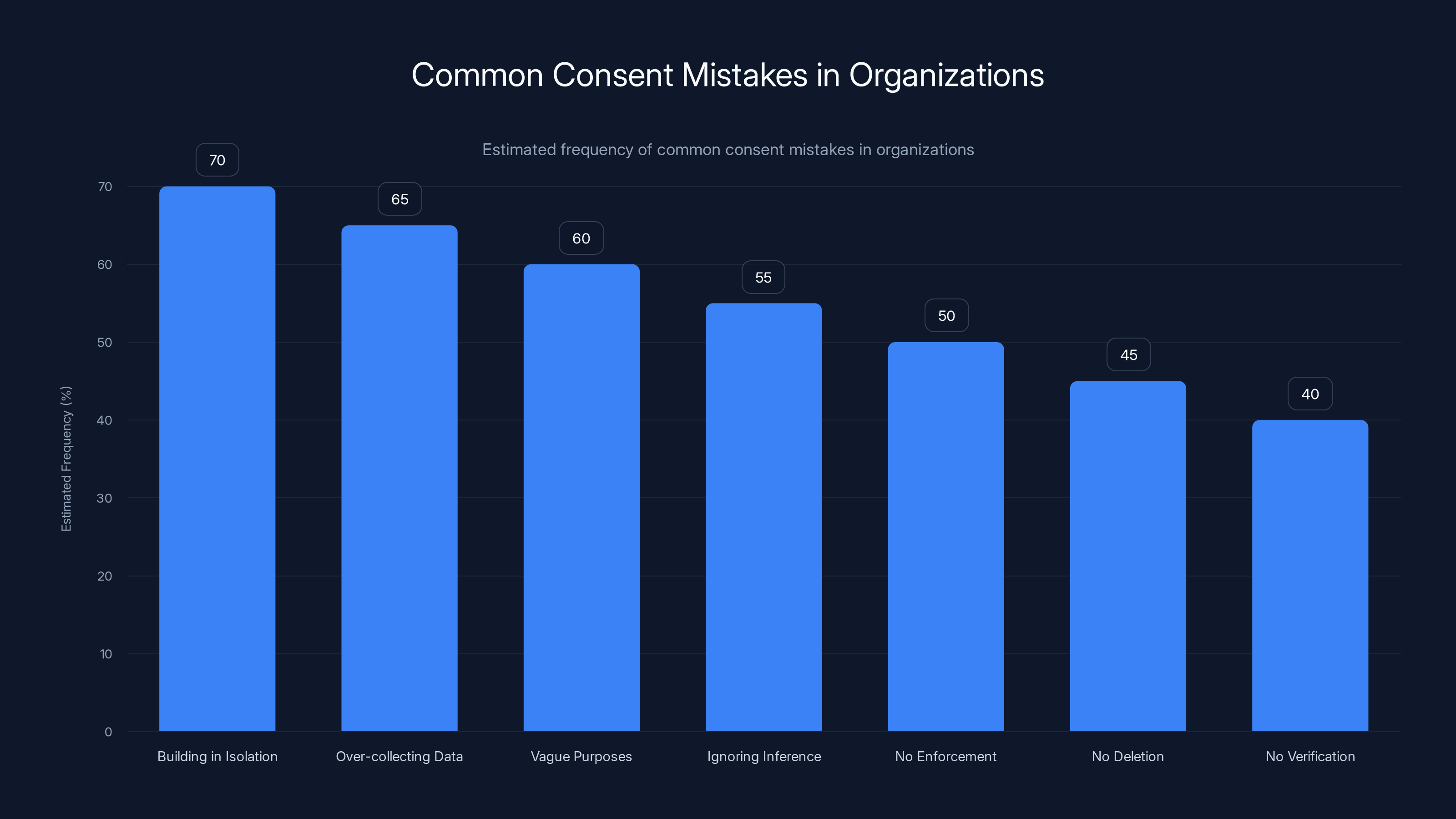

Building consent systems in isolation is the most common mistake, affecting 70% of organizations. Ensuring cross-functional collaboration can mitigate this issue. (Estimated data)

Purpose Mapping: Tying Data Use to Permission

One of the clearest signals that consent is broken is how vaguely most companies describe their data uses.

"Cookies help us provide a better user experience." What does that mean exactly? Better in what way? Through what mechanism?

"We use analytics to improve our site." Analytics of what? Improved in what way? What metrics matter?

"We may share data with partners." What partners? For what purposes? What data specifically?

This vagueness isn't accidental. It's intentional. The vaguer the purpose, the more latitude you have in how you use the data. If you say "analytics," you could mean anything from measuring page load times to building predictive models about user behavior.

Proper consent requires specific purpose mapping. Each piece of data collection should map to a specific, defined purpose. That purpose should be specific enough that a user understands exactly what will happen to their data.

Instead of "analytics," try this: "We collect page view data to measure which content drives the most traffic and which pages have the highest bounce rates. We retain this data for 12 months, then delete it. We do not share this with third parties."

Instead of "improve personalization," try: "We track your product views to improve product recommendations on your next visit. We also use this data to adjust the order of search results to show you relevant products first. This data is retained for 90 days, then deleted. We share this with our AI recommendation vendor but not with ad platforms."

Now the user actually understands what they're consenting to.

Purpose mapping also drives better data practices internally. When you force yourself to specify purposes, you often realize you're collecting data that doesn't map to any legitimate purpose. That's data you should delete. When you specify retention periods, you're forced to think about how long you actually need the data. When you specify who can access it, you eliminate unnecessary sharing.

Purpose mapping becomes a constraint that improves privacy while actually making consent work.

Retention and Deletion: Making Consent Reversible

Consent is only meaningful if it's reversible. A user should be able to revoke consent and expect that their data is actually removed or stopped being used.

But for most organizations, data deletion is complicated. Data lives in multiple systems: the web analytics platform, the data warehouse, the CDP, the marketing automation platform, the ad platform. Once it gets distributed across these systems, it's hard to track where it all is and delete it from everywhere.

Many companies end up with a compromise: they stop using the data going forward, but they don't delete the data already collected. So they technically honor the revocation (no new data collection), but the old data is still there, still potentially being processed, still potentially creating risk.

Real consent requires real deletion. When a user revokes consent, organizations need to:

- Stop collecting that type of data going forward

- Delete that data from all systems where it's stored

- Suppress the user from any ongoing processes built on that data

- Verify that deletion actually happened

Point 4 is critical. It's easy to set a flag saying "don't use this user's data." It's harder to verify that every system actually honored that flag.

This is why retention policies matter. If data is only retained for 30 days, then deletion is easy. After 30 days, the data expires regardless. If data is retained indefinitely, deletion becomes a complex operation. The company has to actively delete it from multiple systems.

The best approach is to make retention policies aggressive. Retain data only as long as necessary for its stated purpose. Once the retention window closes, delete automatically. This makes consent more tractable because you're not managing permanent datasets, you're managing time-limited ones.

It also reduces risk. The longer data is retained, the more likely it is to be breached, subpoenaed, or sold. Aggressive deletion is the best privacy mechanism.

When retention is short and deletion is built-in, consent becomes real. Revoking consent actually results in data being removed. And the technical debt that usually builds up around consent compliance becomes minimal.

Estimated data shows a typical e-commerce site uses a variety of systems, with analytics and customer data platforms being prominent. Ensuring consent travels across these systems is crucial.

Transparency: Making Consent Decisions Possible

For consent to work, users need transparency. They need to understand what data is being collected, why, who has access, and what risks exist.

Most organizations provide transparency through privacy policies. Multi-thousand-word legal documents that almost nobody reads.

This satisfies legal requirements but doesn't actually enable meaningful consent. Users can't consent to something they don't understand, and privacy policies are designed by and for lawyers, not for regular people.

Better transparency requires different approaches. Machine-readable privacy policies that can show users exactly what data a service collects in plain language. Privacy labels similar to nutrition labels on food, showing at a glance what data is collected and shared. In-context disclosures at the moment of data collection, explaining why that specific data is being collected.

Some innovative organizations are experimenting with interactive privacy tools. Show users a map of their data: where it goes, who can access it, how long it's retained. Let users adjust their preferences and see how the map changes. Make privacy tangible rather than theoretical.

Transparency also needs to extend to inferences and sensitivity. Explain not just what data is collected, but what can be inferred from it. If a company is inferring health status from behavior, say that explicitly. If combining data creates sensitivity that wouldn't exist alone, disclose that.

Transparency is often resisted because it's scary. If you're actually transparent about data practices, many users will say no. But that's the point. If data practices only work if you hide them, the practices need to change, not the disclosure.

Building a Consent Architecture

Bringing all of this together requires an actual architecture for managing consent. It's not just a banner and a database. It's a system that touches multiple layers of the organization.

At the bottom layer is the data layer. Where does data actually live? In what databases, data warehouses, and third-party platforms?

On top of that is a consent state layer. A centralized system that knows the consent preferences for each user and each purpose. This system should be queryable and updateable in real-time.

On top of that is the enforcement layer. Rules that say: "If user X has not consented to analytics, don't send analytics data to the analytics platform." These rules are implemented in the data pipeline, in APIs, in SDKs, and in third-party integrations.

On top of that is the interface layer. How users actually make, manage, and revoke consent decisions. This includes banners, but also preference centers, profile pages, and contextual prompts.

Finally, there's a verification layer. Continuous testing that confirms that consent decisions are actually being honored throughout the system.

Building this is work. It's engineering work, product work, legal work, and organizational work. It requires coordination between teams that usually don't coordinate well. Privacy, Engineering, Marketing, Product, Legal.

But the alternative is consent theater: banners that are ignored, choices that are dishonored, and trust that's broken.

Regulatory Trends: Pushing Toward Better Consent

Regulators are getting smarter about consent. They're realizing that cookie banners don't actually work and they're starting to impose stricter requirements.

The EU, which pioneered GDPR, is now pushing regulators and platforms toward a "privacy by default" model. Under this model, consent isn't the primary mechanism. Instead, data collection defaults to "off" unless the user explicitly opts in. This is harder to implement but more honest about user preferences.

Multiple US states are now regulating not just consent but also data minimization. Virginia's VCDPA, Colorado's CPA, and others require that companies only collect data they actually need. This is a subtle but important shift. Instead of asking "Can we collect this?" the question becomes "Do we actually need to collect this?"

California's CPRA is pushing toward automated enforcement and penalties that hurt. The CPRA explicitly requires that companies implement technical and organizational measures to honor consumer rights. And it imposes penalties per violation per user, not per company violation. So if 10 million users don't get their deletion request honored, that's 10 million violations.

International regulations like Singapore's Personal Data Protection Act and Brazil's LGPD are pushing similar directions.

The trend is clear: regulators are losing patience with consent theater. They're moving toward requiring actual enforcement, auditing, and consequences.

This is forcing organizations to actually build the infrastructure for consent. It's no longer optional. It's becoming a regulatory mandate.

The Business Case for Better Consent

Better consent doesn't have to be framed as a regulatory burden. There's actually a business case.

First, trust. When users see that a company actually respects their preferences, they engage more. They're more willing to share data for purposes they care about. They're more likely to come back. Trust becomes a competitive advantage.

Second, efficiency. As mentioned earlier, companies implementing true consent architecture often realize they don't need most of the data they were collecting. Less data means less infrastructure cost. Smaller datasets mean faster processing. Fewer third-party integrations mean lower vendor costs.

Third, risk reduction. Companies with strong consent practices have fewer compliance violations. They're less likely to be fined. They're less likely to have data breaches (less data = lower breach risk). They're less likely to have negative publicity from privacy scandals.

Fourth, data quality. When data collection is purposeful and transparent, the data you collect is more accurate and more useful. You're collecting from people who actually want to share it, who've given thought to their preferences, who are more likely to be truthful.

None of this is theoretical. Companies that have implemented strong consent practices report all of these benefits.

Common Consent Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Here are the pitfalls organizations encounter when trying to improve consent:

Mistake 1: Building consent systems in isolation. The privacy team builds a consent platform without coordinating with engineering, product, and marketing. The consent system can't actually enforce anything because it doesn't integrate with the rest of the infrastructure. Avoid this by making consent a cross-functional initiative from the start.

Mistake 2: Over-collecting to prepare for future use. Companies collect every possible piece of data "just in case" they might want to use it later. This violates data minimization principles and makes consent harder to manage. Avoid this by being strict about collection. Only collect what you actually need today.

Mistake 3: Vague purposes. Privacy teams write purposes that are so broad they're meaningless. Users can't consent to something they don't understand. Avoid this by writing purposes as if you're explaining them to a non-technical user.

Mistake 4: Ignoring inference. Companies think consent is about what's explicitly collected, not what can be inferred. They don't account for combinations of data that reveal sensitive information. Avoid this by thinking through inference chains and treating inferred sensitivity as if explicit sensitivity was collected.

Mistake 5: No enforcement. Consent decisions exist in the consent management system but never actually get implemented in data systems. Users opt out but data still flows. Avoid this by building enforcement from the start. Don't deploy consent without enforcement.

Mistake 6: No deletion. When users revoke consent, the system stops future collection but doesn't delete what's already been collected. Avoid this by implementing automatic deletion when retention periods expire and enforcement of deletion when users request it.

Mistake 7: No verification. Companies assume their consent systems work without actually testing. Avoid this by implementing continuous automated testing to verify that consent decisions are being honored.

Technology Solutions for Consent Management

A range of tools has emerged to help organizations manage consent. These typically fall into a few categories.

Consent Management Platforms (CMPs). These are the banner-and-database systems. They display consent interfaces, record user choices, and store preferences. Examples include One Trust, Trust Arc, and Osano. These are useful but limited. A CMP alone can't enforce consent across systems.

Customer Data Platforms (CDPs). These aggregate data from multiple sources and provide unified access. Many CDPs have consent management features built in. Because CDPs control the data that flows between systems, they're better positioned to actually enforce consent than standalone CMPs. Examples include Segment, mParticle, and Tealium.

Privacy Operations Platforms. These go beyond CMPs and CDPs to provide enforcement and verification across the entire data ecosystem. They handle consent state management, data minimization, retention enforcement, and deletion. These are emerging as the most comprehensive approach.

Data Governance Platforms. These focus on understanding what data exists where and how it's being used. They map data flows and highlight sensitive data. They often have consent features but are primarily focused on governance and discovery.

No single tool solves the consent problem. Most organizations need multiple tools working together: a CMP for user interfaces, a CDP for managing authenticated data flows, and a privacy operations platform for enforcement and verification.

The Future of Consent: Where This Is Heading

If you look at where regulation is trending and where innovative companies are heading, some patterns emerge.

Privacy by default. More regulations will likely move toward requiring privacy by default, where data collection defaults to "off" unless users explicitly opt in. This is harder to implement but more honest.

Automated rights. Tools for managing consent will become more automated. When a user deletes their account, all their data is automatically deleted from all systems without manual intervention. When a user revokes consent, suppression happens automatically across systems.

Transparency standards. Standards will likely emerge for how privacy information is communicated. Similar to nutrition labels on food or auto labels on cars, privacy labels on services will become standard. Users will see at a glance what data is collected, retained, and shared.

Federated identity and privacy. Instead of centralized data silos, more systems will move toward federated approaches where data stays with users and permissions travel with them. Technologies like decentralized identity and zero-knowledge proofs enable this.

Consent as a business feature. More companies will realize that strong consent practices are a competitive advantage. They'll market their privacy practices as a feature, not a burden.

Decentralization. As blockchain and decentralized technologies mature, expect more decentralized approaches to consent and data management. Instead of companies holding centralized databases of personal information, data could be held by users and accessed through permission protocols.

These trends suggest a future where consent is actually meaningful, actually enforced, and actually gives users control.

Practical Implementation: Getting Started

If you're tasked with improving consent practices, here's a path forward.

Phase 1: Audit. Document what data your organization actually collects, who it goes to, and how long it's retained. You'll probably be shocked. Most companies collect far more than they thought and share far more widely.

Phase 2: Classification. Categorize that data. What's personal? What's sensitive? What's inferred? What's shared? What can be inferred from combinations?

Phase 3: Purpose mapping. For each data collection, define the specific purpose. What problem does this data solve? Write it in plain language.

Phase 4: Streamlining. Remove data collection that doesn't map to a clear purpose. Remove sharing that isn't necessary. Aggressively reduce the scope of collection.

Phase 5: Consent design. Design consent experiences for the data you're actually keeping. Prioritize contextual consent. Make purposes clear. Start small and expand.

Phase 6: Enforcement. Build technical controls to actually enforce consent. Add rules to your data pipelines. Update third-party integrations. This is the most work but also the most important.

Phase 7: Verification. Set up automated testing to confirm that consent is being honored. Run this continuously.

Phase 8: Expansion. Once the foundation is solid, expand to more sophisticated consent approaches. Add preference centers. Implement data access tools. Build deletion workflows.

This takes time. It's not a quick project. But it's foundational to a trustworthy organization.

Making Consent Meaningful

The path forward is clear: consent has to move from a compliance checkbox to an actual operational system. That requires infrastructure, organization, persistence, and commitment.

But it's worth doing. Because in a world where data is increasingly valuable and increasingly intrusive, consent is the mechanism that prevents companies from treating users as raw material to be extracted.

Consent done right means users actually understand what's happening to their data. It means users can actually control what happens. It means companies can actually prove they're respecting those choices. It means trust can be real.

Consent broken means none of those things. It means banners that are ignored. It means choices that don't matter. It means trust that's hollow.

The decision is which kind of consent you want to build. And the decision matters more than you probably think.

FAQ

What is contextual consent and why is it better than banner-based consent?

Contextual consent asks for user permission at the moment when the purpose is clear and value is visible, like asking to save a cart during checkout or explaining analytics when a video starts playing. It's better than banner-based consent because users actually understand what they're agreeing to, consent is tied to specific purposes rather than being a vague "accept all," and it generates more informed, meaningful decisions. Banner-based consent appears before users interact with anything and when they know the least about data practices.

How can organizations actually enforce consent across their data systems?

Organizations need to establish a centralized source of truth for consent preferences that's queryable by every system handling user data. When data flows through APIs, SDKs, or into data warehouses, those systems check the central consent record before processing. When a user revokes consent, that central record updates immediately, and all downstream systems automatically stop using that data or suppress that user from relevant processes. This requires integration between the consent management platform and analytics systems, CDPs, data warehouses, and third-party vendors.

What's the difference between explicitly collected sensitive data and inferred sensitive data for consent purposes?

Explicitly collected sensitive data is information directly provided or obviously revealed, like health information typed into a form or financial account numbers. Inferred sensitive data emerges through combinations of seemingly innocuous information, like searching for "bipolar disorder" plus browsing therapy booking sites that together clearly indicate mental health status. For consent purposes, organizations should treat inferred sensitivity the same as explicit sensitivity because the privacy risk is similar, even though the collection mechanism is different.

Why do most organizations fail to honor user consent choices even when they try?

Most organizations fail because consent decisions are recorded in one system (the consent platform) but data flows to dozens of other systems (analytics, ad platforms, marketing tools, data warehouses) that don't automatically check consent status. Additionally, much consent is broken through misconfiguration, like marketing platforms adding new parameters by default or vendors updating their implementations without notification. Without continuous automated verification that systems are respecting consent, drift and misconfiguration are inevitable.

What are the key differences between privacy laws like GDPR, CCPA, and newer regulations like CPRA?

GDPR (EU) pioneered consent as the primary mechanism for lawful data processing, though it's now pushing toward privacy by default. CCPA (California) created the right to know, delete, and opt-out but allowed many uses without explicit consent. CPRA (California) is stricter, requiring data minimization, automated rights enforcement, and per-violation penalties (not just per-company). Newer state laws like VCDPA (Virginia) and CPA (Colorado) emphasize data minimization and consumer rights more than explicit consent. The trend is toward regulations that require actual operational enforcement, not just consent banners.

How should organizations handle data retention in relation to consent?

Organizations should implement strict retention policies: data is kept only as long as necessary for its stated purpose, then automatically deleted. Short retention windows make consent tractable because companies aren't managing permanent datasets. They reduce risk because less data means lower breach potential. Aggressive deletion also aligns with data minimization principles. When a user revokes consent, deletion should be immediate for recent data and automatic for data reaching the retention window.

What practical steps should organizations take to improve consent implementation?

Start with an audit of what data is collected, where it goes, and how long it's retained. Classify that data by type and sensitivity. Map each collection to specific purposes. Remove data collection that doesn't serve a clear purpose. Design consent experiences that are contextual and transparent. Build technical enforcement into data pipelines so choices actually propagate to all systems. Set up automated testing to verify consent is being honored. This is foundational work that takes time but is essential for trustworthy data practices.

Digital consent is broken today. But it doesn't have to stay broken. Organizations that take the work seriously, invest in the infrastructure, and prioritize user understanding can rebuild something that's actually meaningful. That's the path forward.

Key Takeaways

- Cookie banners are compliance theater that don't give users real control over data

- Consent decisions must propagate through entire data systems through centralized source of truth

- Contextual consent (asking when value is clear) generates more meaningful user choices

- Sensitive information often emerges through data combination and inference, not explicit collection

- Real enforcement requires continuous automated testing, not one-time banner implementation

- Regulations are evolving toward requiring operational enforcement and data minimization

- Building consent architecture is cross-functional work requiring coordination across teams

Related Articles

- Humanoid Robots & Privacy: Redefining Trust in 2025

- Europe's Sovereign Cloud Revolution: Investment to Triple by 2027 [2025]

- Flickr Data Breach 2025: What Was Stolen & How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- The Hidden Threat of Typosquatting: Protecting Your VPN Experience [2025]

- Surfshark VPN Two-Year Deal: Save Up to 87% in 2025

- Zettlab D6 Ultra NAS Review: AI Storage Done Right [2025]

![Digital Consent is Broken: How to Fix It With Contextual Controls [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/digital-consent-is-broken-how-to-fix-it-with-contextual-cont/image-1-1770824373119.jpg)