Humanoid Robots and Privacy: Redefining Trust, Dignity, and Control in the Age of Physical AI

TL; DR

- Humanoid robots observe continuously, capturing intimate data through gesture, tone, and proximity that exceeds traditional sensors.

- Privacy law is broken, designed for static files and screens, not dynamic real-time interaction with learning machines.

- Cryptography becomes essential, with federated learning, homomorphic encryption, and secure multi-party computation making privacy mathematically enforceable.

- Cultural sensitivity matters, because respect, discretion, and care must be embedded in code, not just policy.

- The window to act is now, before humanoid units surpass one million in 2035, making regulatory catch-up nearly impossible.

You're sitting on your couch. A humanoid robot enters the room. It watches you stand, notices you wince slightly, observes the tremor in your hand. It doesn't ask permission to analyze your movement. It just does.

That single moment contains everything we need to understand about privacy in the age of humanoids.

For decades, we've treated privacy like a checkbox—a thing you consent to in fine print. But a humanoid doesn't care about your checkbox. It cares about your posture, your breathing, your emotional state. It learns from these observations continuously, storing them, processing them, potentially sharing them with manufacturers, insurance companies, or anyone with access to the system.

We're standing at the threshold of a fundamentally different future. Not because technology is advancing faster, but because machines are about to become witnesses to our most intimate moments. And we're woefully unprepared.

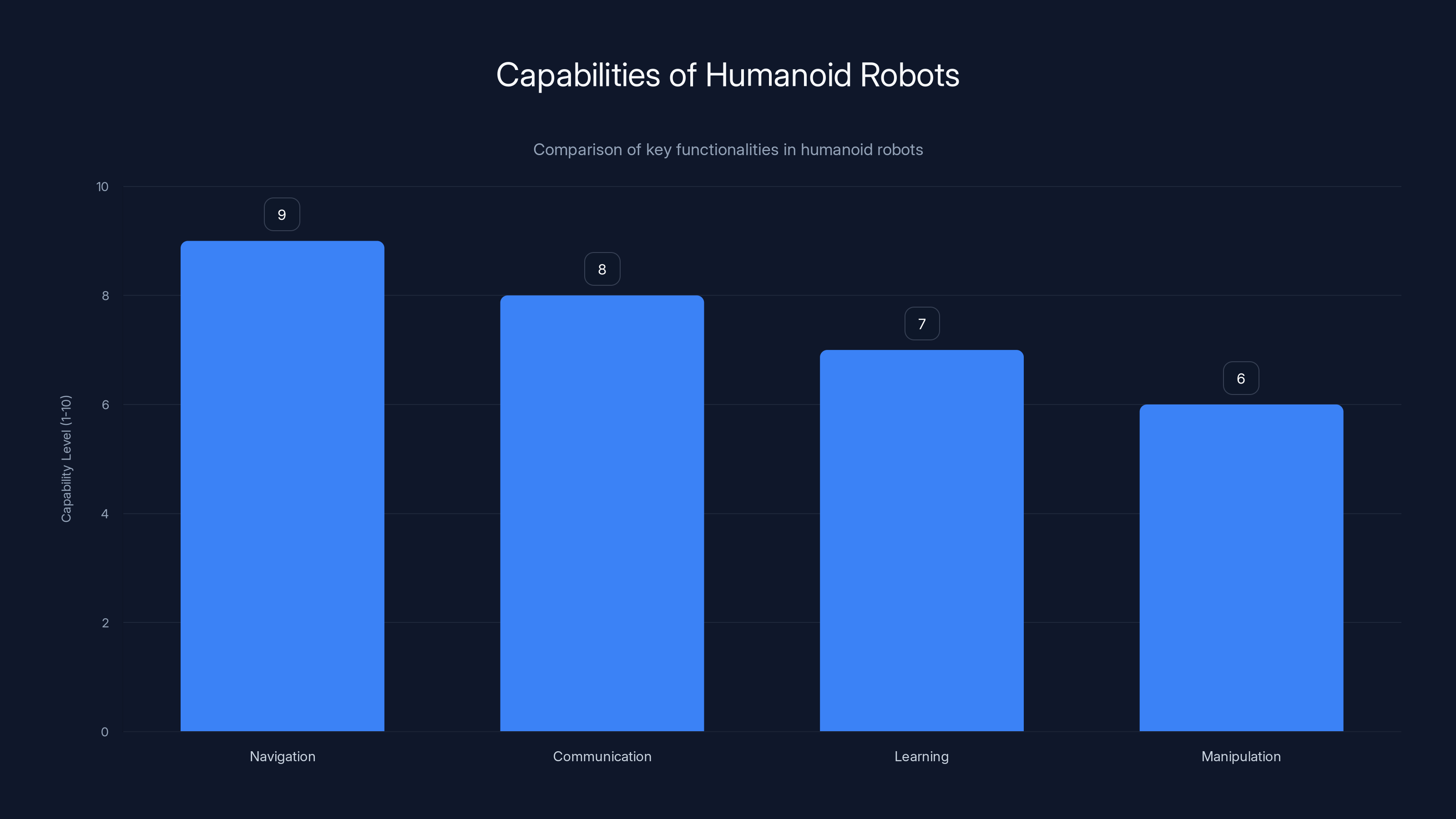

Humanoid robots excel in navigation and communication, with strong capabilities in learning and manipulation. Estimated data based on typical functionalities.

The Humanoid Horizon: From Lab to Living Room

Let's be clear about what's coming. Goldman Sachs doesn't throw around forecasts lightly, yet they're projecting consumer humanoid robot sales will surpass one million units by 2035. That's not science fiction. That's nine years from now. Some estimate we'll see 10 million units by 2050.

These aren't robots that sit in factories. They're entering hotels as greeters, hospitals as patient assistants, schools as tutors, and homes as caregivers. Your neighbor probably has one before you notice the trend started.

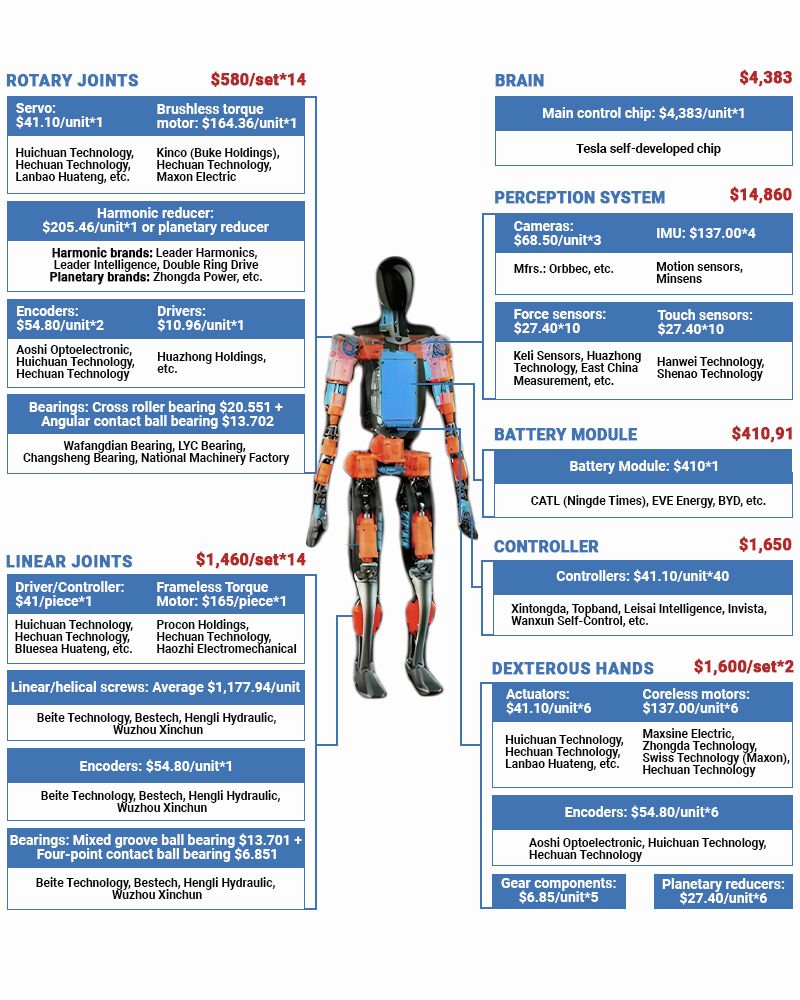

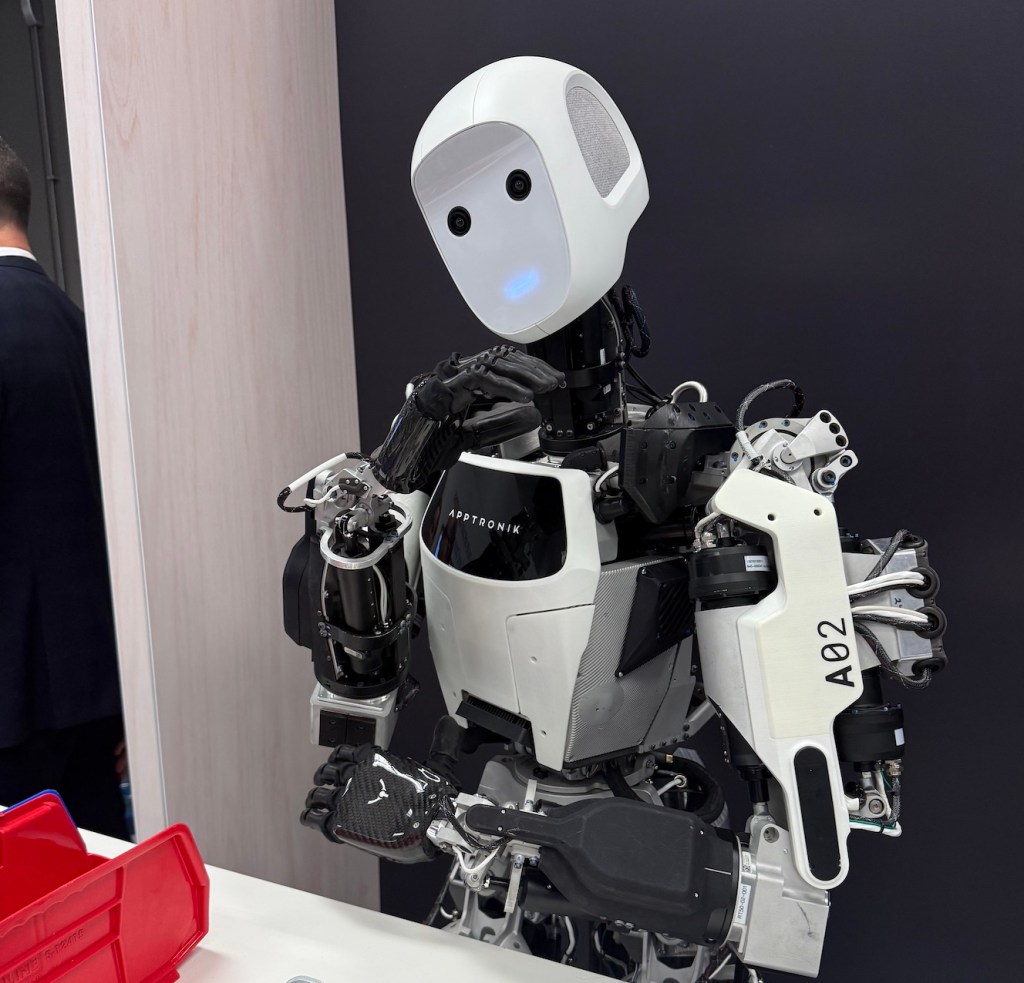

Companies like Tesla with Optimus, Boston Dynamics with their biped systems, and dozens of startups are racing toward the same finish line: a machine that can navigate human spaces, learn human preferences, and interact with human complexity. They're getting closer faster than most people realize.

The technology is advancing because the problems they solve are genuinely valuable. An elderly person living alone can maintain independence with robotic assistance. A hospital can extend care capacity without hiring thousands of new staff. A family can reclaim hours previously spent on household drudgery.

But here's what gets glossed over in every press release: these machines don't just perform tasks. They observe. They collect data. They build models of the people they interact with.

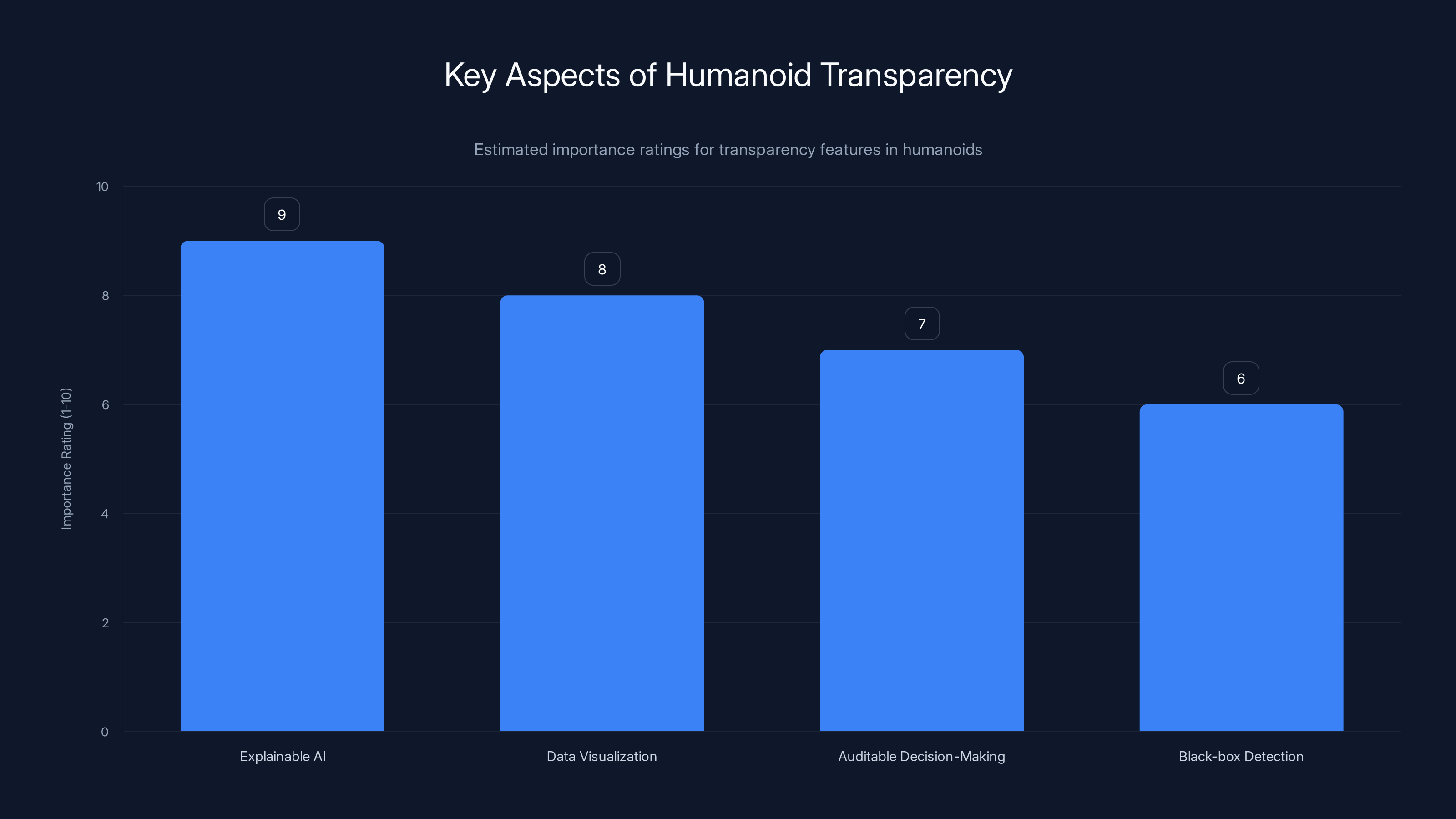

Explainable AI is rated as the most important feature for transparency in humanoids, followed by data visualization and auditable decision-making. Estimated data.

Why Humanoids Are Different From Every Tech That Came Before

Your phone collects data. Your smart home collects data. Your fitness tracker collects data. You know this. You've accepted it, mostly, because you can put your phone down. You can unplug your speaker. You can choose not to wear the tracker.

A humanoid is always present. It's not a device you turn off when you're done with it. It's a presence in your space, continuously perceiving, learning, adapting.

Consider what a humanoid actually observes in a single day:

Movement and posture data: How you walk, whether you favor one leg, how quickly you can stand, the steadiness of your gait. This reveals information about your health status, mobility limitations, neurological conditions, and aging trajectory.

Facial expressions and micro-expressions: These happen faster than conscious control. A humanoid trained to recognize them can infer emotional states, reactions to news, preferences before you speak them aloud.

Vocal patterns: Tone, pace, pitch, hesitation. A robot can detect stress, deception, exhaustion, excitement with remarkable accuracy. Combined with content analysis, it builds a complete emotional profile.

Proximity and spatial behavior: How close you stand to people, which rooms you spend time in, what times you're active. This reveals your relationships, your routines, your mental state.

Behavioral patterns: What you eat, when you eat it, how much time you spend on activities. Repeated observations build predictive models of your preferences, habits, and decision-making patterns.

None of this requires explicit data collection. A traditional camera and microphone capture some of it. But a humanoid has something more: context. It understands the situation. It reasons about causation. It learns from interaction.

A security camera records what you do. A humanoid understands why you do it.

This distinction matters enormously because it changes the nature of the privacy threat. We've spent twenty years building regulations around data collection: what data is collected, where it's stored, who can access it, how long it's retained.

But a humanoid doesn't need to store much data to be dangerous. It needs to understand you. And understanding happens in real time, in the robot's neural networks, potentially invisible to any external audit.

The Obsolescence of Consent: Why Your Checkbox Doesn't Matter Anymore

Here's what we've been doing wrong: we've treated privacy as a compliance problem instead of a design problem.

Fill out a privacy policy. Check the box. Add another checkbox. Now users have "consented." Problem solved, right?

Wrong. And humanoids expose why completely.

When a humanoid helps an elderly person stand, it must analyze their posture, predict their balance, detect hesitation, and respond in milliseconds. There's no time for consent negotiation. There's no interface to explain what data is being collected. There's no way for the user to meaningfully control what the robot observes.

Moreover, the data being collected is about your body, your movements, your vulnerabilities. Some of it you might not even consciously know about yourself. A humanoid might detect the early signs of a neurological condition before you do. Should it tell you? Should it tell your insurance company? Your employer? Your family?

These aren't edge cases. They're the common case.

Traditional privacy law was built for different times. GDPR, CCPA, and similar regulations assume data is collected, stored, and potentially accessed later. They provide rights to access, deletion, portability. But they assume humans, not machines, make decisions about your data.

With a humanoid, the decision-making is distributed across:

- The robot itself (making local decisions)

- The cloud infrastructure (processing data, training models)

- The manufacturer (setting system policies)

- Third parties (accessing logs, analyzing patterns)

- Government agencies (accessing data for law enforcement)

You can't meaningfully consent to all of this. You can't fully understand the implications. Checkboxes are theater.

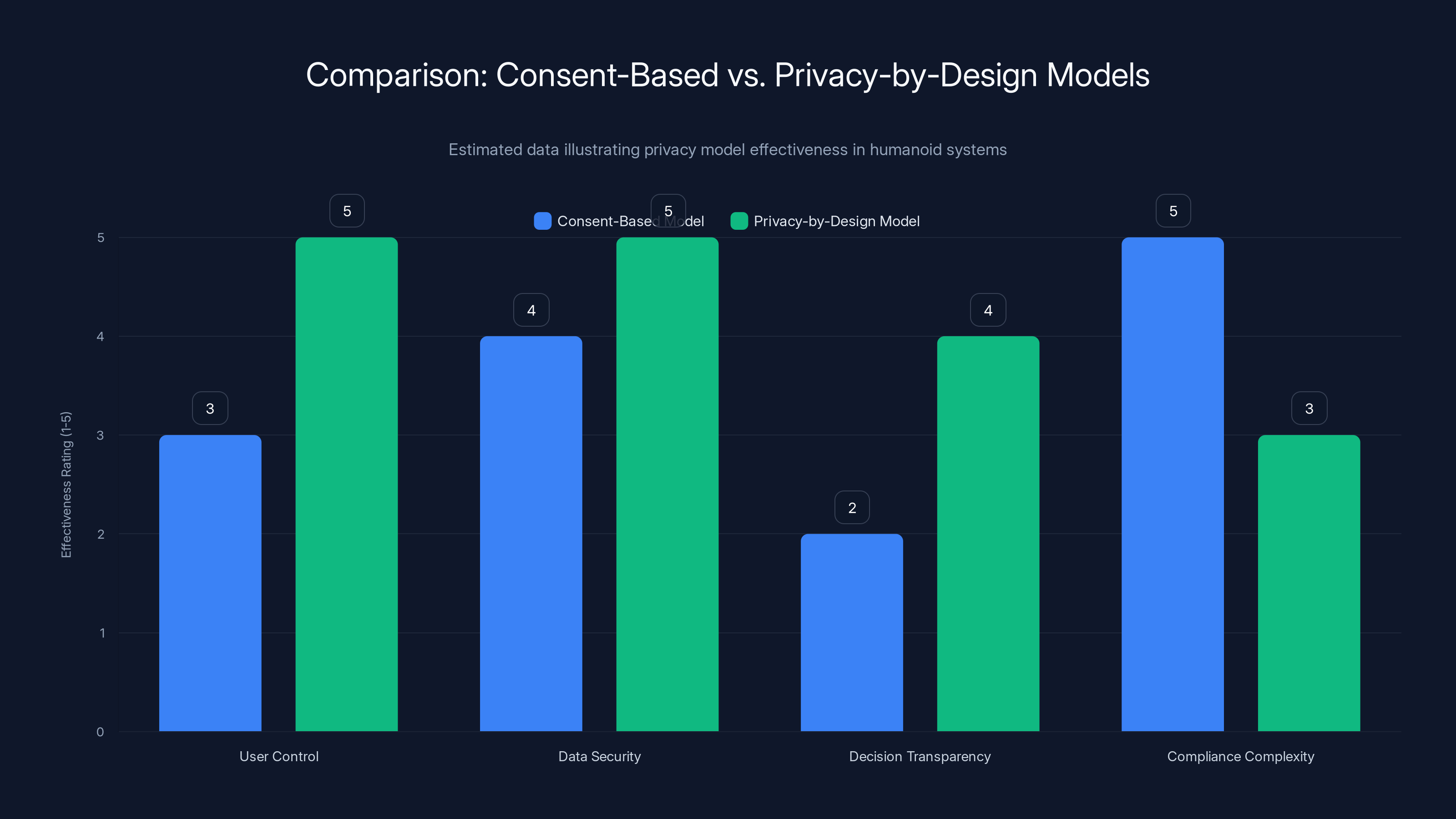

What we need instead is something far more radical: privacy by design, not by consent.

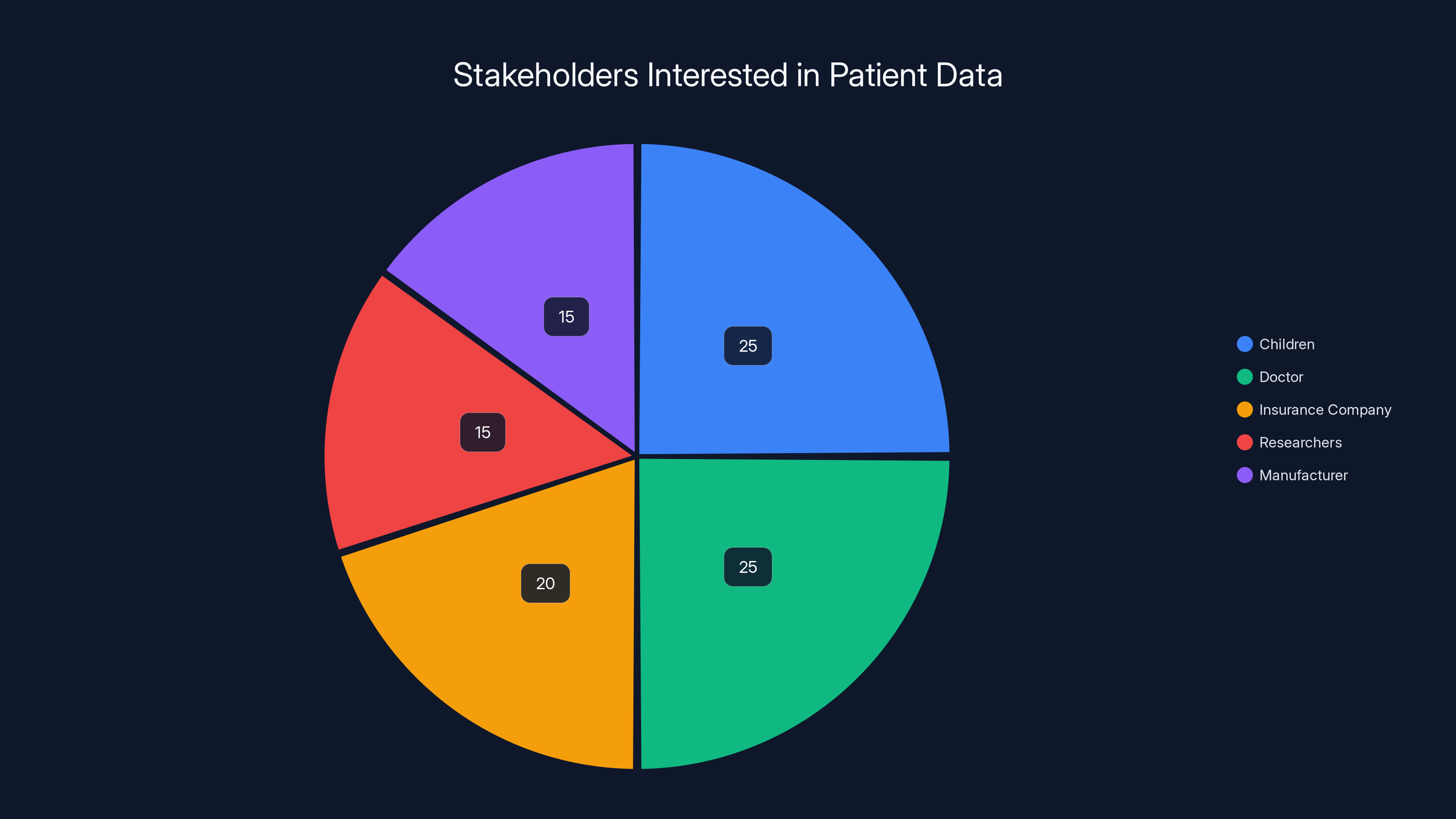

Estimated data shows that children and doctors have the highest interest in patient data for caregiving, while insurance companies, researchers, and manufacturers also have significant interest for their respective purposes.

Privacy by Architecture: Making Privacy Mathematically Enforceable

Let's talk about what actually works.

Cryptography is old technology. It's been around for thousands of years in various forms. But modern cryptographic protocols offer something revolutionary: the ability to prove that data has not been accessed, without requiring trust.

Instead of trusting a company's policies, you trust mathematics.

Here's how this works in practice. Imagine a humanoid is monitoring an elderly person's sleep patterns to detect changes that might indicate health problems. The robot needs to learn from this data to improve its care. But the data is deeply private.

Traditional approach: Collect the data, send it to the cloud, store it, process it, hope nobody hacks it or sells it.

Modern cryptographic approach: The robot processes the data locally. It uses a cryptographic protocol that allows it to extract useful learning signals without ever reconstructing the raw data. The manufacturer can verify the robot is functioning correctly without ever seeing what the robot observed.

This is the difference between policy promises and mathematical guarantees.

Several specific technologies make this possible:

Federated learning allows AI models to improve by learning from data without centralizing that data. Instead of sending your movement data to a cloud server, the humanoid learns locally and only shares model updates (abstract patterns) with the central system. Your specific movements remain private.

Homomorphic encryption lets you perform computations on encrypted data without decrypting it first. The manufacturer can analyze patterns in your health data without ever seeing your actual measurements. The math guarantees they're analyzing what they claim.

Secure multi-party computation enables multiple parties (robot, manufacturer, hospital, researcher) to jointly analyze data without any single party seeing the raw information. Each party contributes data in encrypted form. Only the final result is revealed.

Differential privacy adds mathematical noise to datasets in a way that preserves useful patterns while making it impossible to reverse-engineer individual records. Analysis is still possible, but privacy is mathematically guaranteed.

These aren't theoretical. They're implemented in systems right now. But they're rarely the default. They require intentional engineering decisions.

The key insight: privacy isn't something you add at the end. It's something you design in from the beginning. And when done correctly, it's not a tradeoff with functionality. The humanoid functions better because the privacy architecture forces cleaner system design.

The Cultural Dimension: Respect, Proximity, and Shared Dignity

Here's something most technologists miss: privacy isn't purely a technical problem. It's cultural.

In some cultures, direct eye contact is respectful. In others, it's aggressive. In some, a person's gait is a source of pride. In others, it's deeply private. Some cultures value independence above all; others prioritize family interdependence.

When a humanoid robot enters a space, it needs to understand these boundaries. Not just legally—culturally.

A humanoid designed in Silicon Valley might interpret facial expressions in ways that are deeply offensive to someone from a different cultural background. It might maintain eye contact in a way that feels intrusive. It might respect personal space in ways that feel cold and rejecting to cultures that value physical proximity.

This matters because when a humanoid misunderstands cultural norms, it's not just uncomfortable. It can be a violation of dignity.

Consider a humanoid designed to assist in healthcare. In the United States, patient autonomy is paramount—the robot should defer to patient preferences even when it disagrees. In many Asian cultures, family input is central—the robot should involve family members in decision-making. In some African cultures, community context matters—the robot should understand the patient's role within their wider community.

A robot designed with only U.S. assumptions isn't just culturally insensitive. It's actively disrespectful to people from other backgrounds.

This is why privacy and dignity must be embedded in code, not left to interpretation.

When engineering a humanoid:

Design for transparent reasoning: The robot should be able to explain why it's observing something. "I'm detecting your movement pattern to improve my ability to assist with mobility" is different from silent observation.

Implement boundary settings: Users should be able to define which observations are acceptable in which contexts. "In the bedroom, monitor only audio for emergencies. In the kitchen, monitor movement to prevent falls."

Respect cultural preferences: Build in adaptable models for different cultural contexts. Don't assume Western assumptions about personal space, eye contact, or emotional expression.

Implement graceful degradation: If a humanoid doesn't understand a cultural context, it should ask. It should defer. It should err on the side of respect.

Enable human override: At any moment, a user should be able to temporarily disable observation, require explicit consent for specific activities, or request that certain data be forgotten.

These aren't nice-to-haves. They're essential for the robot to actually respect the people it serves.

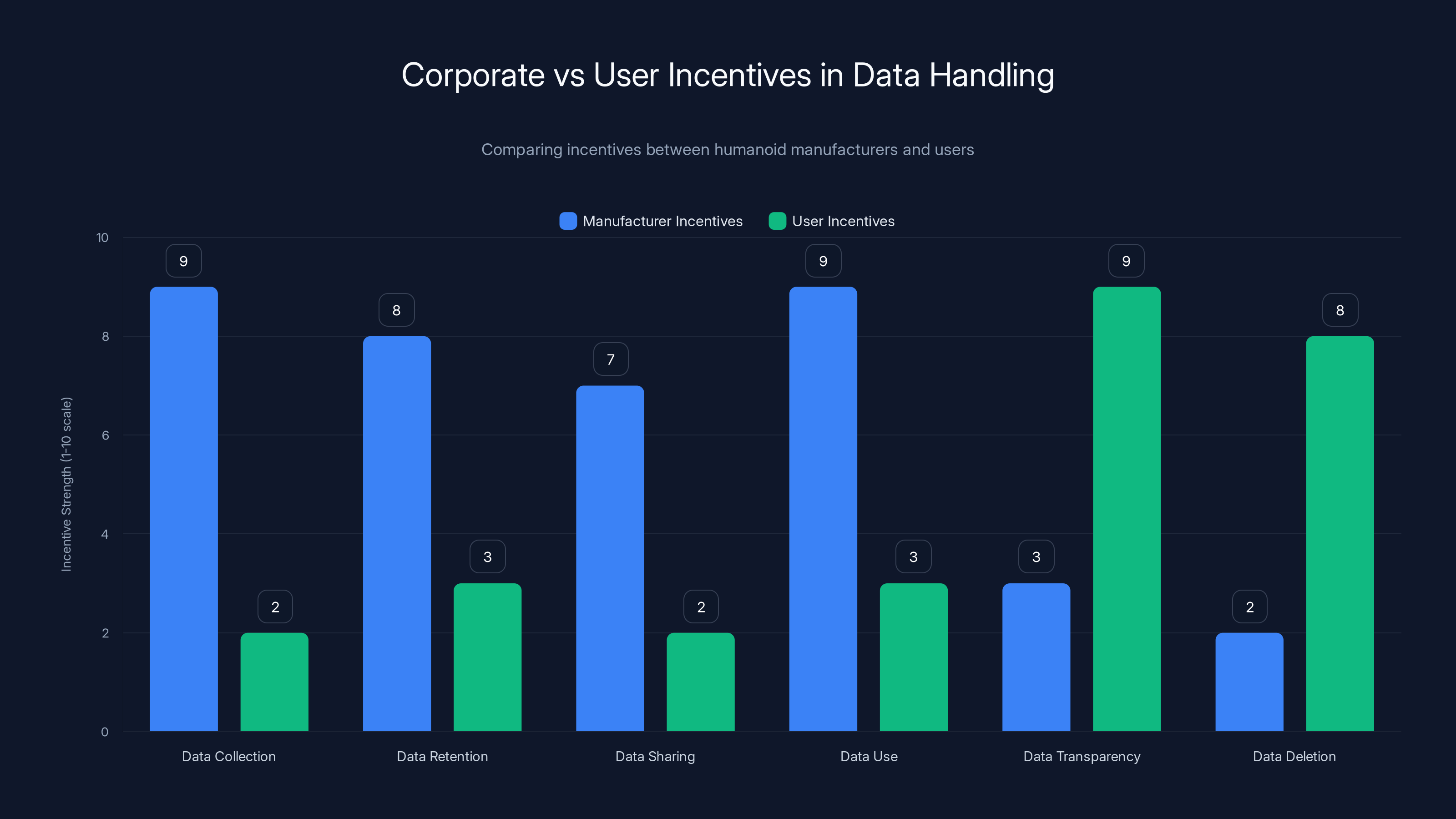

Manufacturers prioritize data collection and retention, while users focus on privacy and data control. Estimated data highlights the opposing nature of these incentives.

The Data Ownership Question: Who Owns Your Movements?

Let's get concrete about a real scenario.

A patient in a hospital is assisted by a humanoid robot. Over three months, the robot collects detailed data about the patient's movements, recovery patterns, response to therapy, and behavioral changes. This data is incredibly valuable for medical research, insurance optimization, and understanding treatment effectiveness.

But who owns it?

The patient might argue they own it because it's data about their body. They might want compensation if the hospital sells it. They might want it deleted if it reveals something embarrassing.

The hospital might argue they own it because they purchased the robot and implemented the care protocol. They might want to use it to improve outcomes for future patients.

The robot manufacturer might argue they own it because the robot generated the insights. They might want to use it to improve their AI models.

The insurance company might argue they own it because they're paying for the treatment. They might want to use it to optimize coverage decisions.

Researchers might argue they own it because aggregate analysis could benefit society. They might want it to study treatment effectiveness.

Everyone has a claim. The patient has a claim rooted in bodily autonomy. The hospital has a claim rooted in operational necessity. The manufacturer has a claim rooted in technological innovation. The insurer has a claim rooted in financial responsibility.

Current law doesn't give clear answers. Different jurisdictions have different frameworks. Some treat health data as personal (belongs to the patient). Some treat it as medical information (belongs to the healthcare provider). Some treat it as research data (should be openly shared for public benefit).

This ambiguity is exactly where abuse happens.

A thoughtful approach would establish clear rules:

-

Data about your body belongs to you, full stop. You own the right to control who sees it and how it's used.

-

The hospital or care provider has rights to use that data for your direct care without additional consent. But they need explicit permission to use it for research or commercialization.

-

Aggregate, truly anonymized data can be shared for research, but individuals should have the right to opt out entirely, even if it means slightly less personalized care.

-

Commercial use requires explicit compensation and consent. If someone profits from data about your body, you share that profit.

-

You have the right to delete, with limited exceptions for care continuity. You can demand your data be forgotten.

Setting clear rules now, before humanoid systems are ubiquitous, is vastly easier than trying to regulate retroactively when billions of people have years of intimate robot-collected data.

Transparency: Making the Invisible Visible

Here's a challenge that doesn't have a perfect solution but desperately needs one: how do you make visible what a humanoid is actually doing?

A traditional camera is transparent. You can see what it's observing. A microphone is transparent. You know it's recording sound. But a humanoid's observation is distributed across multiple sensors, processed through neural networks, abstracted into learned patterns, and stored in ways that don't correspond to human-readable data.

You can't "see" what a humanoid learned about your emotional state. You can't read the abstract representations of your movement patterns. The data isn't in a form that humans can easily understand.

This transparency problem matters because without visibility, there's no meaningful control. And without control, there's no real consent or dignity.

What might actual transparency look like?

Explainable AI: The humanoid should be able to say why it made a decision. Not just "I detected a fall risk" but "I detected a fall risk because your walking speed decreased 15% compared to yesterday, and your balance corrections are smaller than typical." This is technically challenging but possible.

Data visualization: Periodically, show users what data has been collected about them in a human-readable form. Here are your movement patterns over the past week. Here are the emotional states I inferred. Here are the predictions I've made about your preferences.

Auditable decision-making: When the humanoid makes an important decision (recommending a medical intervention, adjusting assistance level, alerting a caregiver), it should create an audit trail explaining the reasoning. You should be able to review why the robot did what it did.

Black-box detection: Systems should automatically flag when the humanoid makes a decision it can't explain. "I decided to increase monitoring, but I can't articulate why." This signals that something about the decision-making has become opaque and needs human review.

Third-party auditing: Independent parties (regulators, patient advocates, researchers) should be able to audit the humanoid's decision-making without compromising individual privacy. This requires cryptographic techniques that enable verification without exposure.

Transparency is computationally expensive and sometimes at odds with privacy (explaining a decision sometimes requires revealing the data that informed it). But the alternative—opaque machines making intimate decisions about our lives—is unacceptable.

The privacy-by-design model scores higher in user control, data security, and decision transparency, while reducing compliance complexity compared to traditional consent-based models. Estimated data.

Regulatory Frameworks: The Race Against Time

Policymakers are scrambling. And they should be scrambling because the window to establish rules is closing fast.

Right now, humanoid robots are rare enough that their impact is limited. Most people have never interacted with one. Regulations can still be developed, tested, refined, and implemented before widespread deployment.

But this window closes in years, not decades.

Once millions of humanoids are in homes, hospitals, schools, and workplaces, retroactive regulation becomes nearly impossible. You can't uninvent the technology. You can't undo the data that's already been collected. You can't restore privacy to interactions that already happened.

What should effective regulation look like?

Privacy impact assessments before deployment. Any humanoid system should be required to conduct a thorough analysis of what data it collects, how it uses that data, what risks exist, and what safeguards are in place. This assessment should be public (without revealing security vulnerabilities).

Mandatory privacy-by-design standards. Humanoids shouldn't be allowed on the market unless they meet architectural standards for privacy protection. Not optional security, not policies that can be changed later. Built-in, uncompromisable technical standards.

Regular auditing and certification. Just as medical devices are certified and monitored, humanoid robots should be certified for privacy and security. This certification should be renewed regularly, not just once at approval.

Robust individual rights. Users should have meaningful rights to:

- Know what data is being collected

- Control which data is collected in which contexts

- Request deletion

- Receive compensation if data is misused

- Sue for damages if privacy is violated

Liability rules. Who's responsible when a humanoid violates privacy? The manufacturer? The operator? The user? Rules need to be clear so that someone has incentive to actually implement good practices.

Cross-border coordination. Unlike earlier technologies, humanoid robots will be deployed globally. A regulation that only applies in the EU is insufficient if the robot is manufactured in Asia and deployed in North America. Harmonized standards, mutual recognition agreements, and enforcement cooperation are necessary.

Developing these frameworks requires input from technologists, policymakers, ethicists, privacy experts, and most importantly, people from diverse communities who will actually live with these machines.

It's also urgent. Most experts estimate we have 3-5 years before the regulatory moment passes. After that, inertia takes over, and change becomes exponentially harder.

The Healthcare Case Study: Where Privacy Becomes Life-or-Death

Healthcare is where the stakes get real. This isn't abstract philosophical privacy concern. This is about whether a robot caring for your parent reveals information that affects their insurance, their independence, their dignity.

Consider a realistic scenario:

An 78-year-old woman with mild cognitive decline lives at home. Her family is concerned about falls and safety, so they hire a humanoid robot to assist. The robot helps her bathe, dress, move around the house, and reminds her about meals and medications.

Over three months, the robot collects extensive data:

- She forgets things about 40% more often than average

- Her gait is slightly unsteady, particularly after 6 PM

- She sometimes stands confused for 30 seconds before acting

- Her emotional state shifts significantly based on whether her children visit

- She often avoids the bathroom late at night, suggesting concern about falling

All of this data is medically relevant. It tells a story about her cognitive trajectory and physical safety.

But here's the problem: who should know?

Her children absolutely need to know, so they can help her. Her doctor needs to know to optimize her care. Her insurance company probably wants to know, to assess whether she needs more expensive coverage or could be dropped. Researchers studying cognitive decline would love access to this data. The manufacturer wants it to improve the AI model.

Each stakeholder has a reasonable argument. But each creates risk.

If insurance companies know she's experiencing cognitive decline, will they drop her? Deny coverage? Raise her premiums? These outcomes are illegal in many places, but insurance companies are sophisticated at finding proxies.

If her employer knew she had this data, could they force her to resign? Not openly, but subtle pressure could do it.

If her estranged husband knew she was experiencing cognitive decline, could he use that to challenge her independence or override her decisions?

Worse: what if the data is simply wrong? What if the robot's inference of cognitive decline is incorrect? What if it's flagging patterns that are actually irrelevant?

In healthcare, humanoid privacy isn't about comfort. It's about autonomy, dignity, and outcomes.

A thoughtful approach:

-

Design the humanoid with the patient's welfare as sole priority, not the hospital's, insurance company's, or manufacturer's.

-

Collect the absolute minimum data needed for safe, effective care. If balance monitoring is sufficient, don't collect emotional state data.

-

Keep data local by default. Process it on the robot. Only share with the care team when medically necessary.

-

Require explicit consent for non-care use. If research is conducted, the patient must consent and receive transparency about findings.

-

Implement independent verification. Before data is used for any consequential decision (changing care level, affecting insurance, etc.), an independent party should verify the data is accurate and properly interpreted.

-

Establish clear deletion timelines. Data should be deleted when no longer medically necessary, not kept indefinitely "just in case."

These rules shift the default from "collect everything and hope for the best" to "collect only what's necessary and protect what we collect."

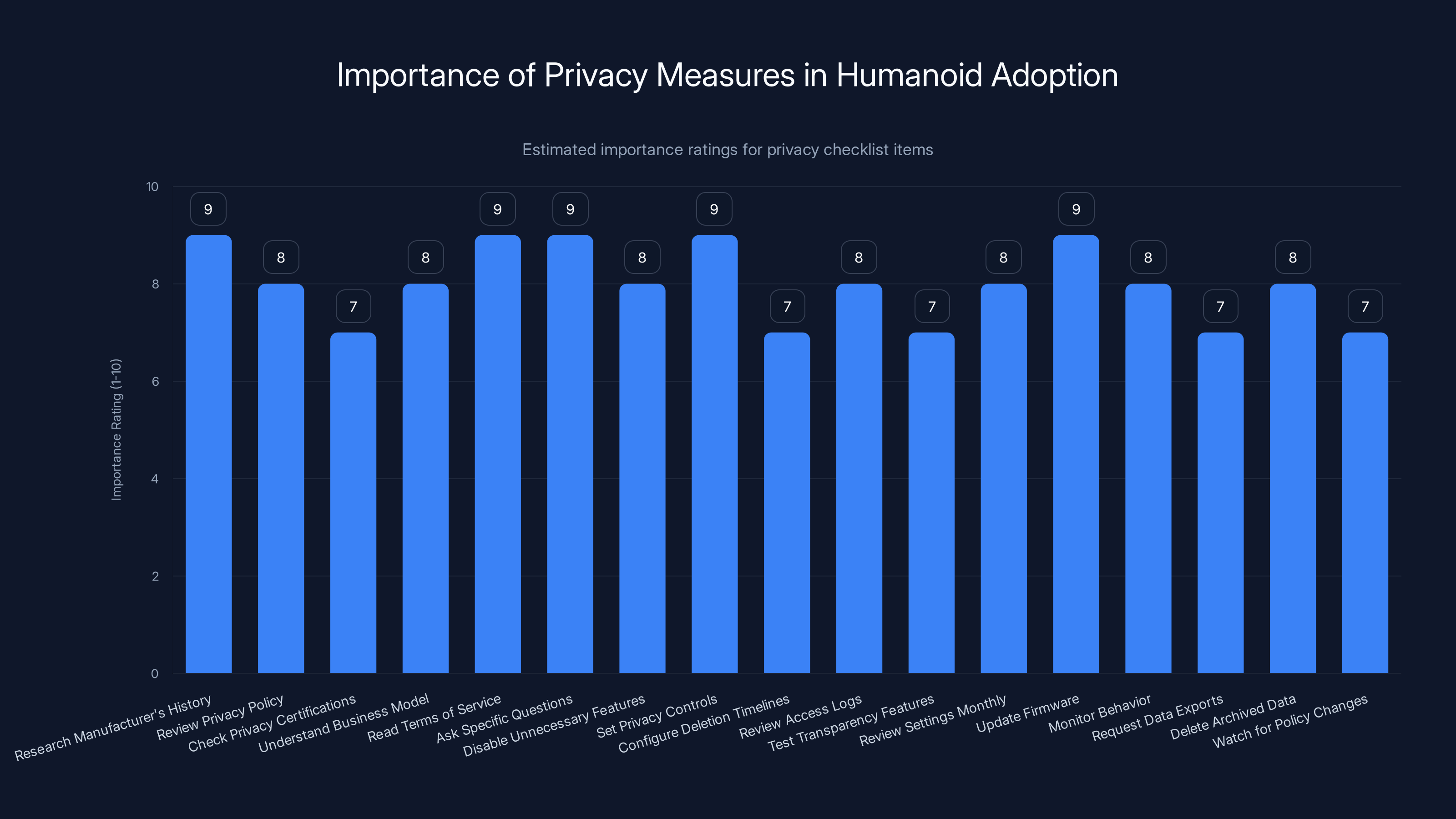

Estimated importance ratings suggest that understanding the manufacturer's history and terms of service are crucial for privacy in humanoid adoption. (Estimated data)

Corporate Incentives: The Fundamental Problem

Let's be honest about something: technology companies profit from data. It's their business model.

Google doesn't make money selling search. It makes money selling insights about what you search for. Facebook doesn't make money selling social networking. It makes money selling insights about your relationships and interests. The manufacturer of your humanoid robot wants to do the same thing: collect data about you and monetize insights derived from that data.

This isn't evil. It's just business. But it's fundamentally misaligned with privacy and dignity.

A humanoid manufacturer has incentive to:

- Collect as much data as possible (more data = better models)

- Keep data indefinitely (future monetization opportunities)

- Share data widely (partnerships create revenue)

- Use data for purposes beyond stated care (more profit)

- Hide what data is collected (less user objection)

- Resist deletion requests (it costs money)

Meanwhile, users have incentives to:

- Minimize data collection (protect privacy)

- Delete data frequently (reduce risk)

- Limit who sees data (reduce misuse)

- Know exactly what data is collected (meaningful control)

- Receive compensation if data is used commercially (offset risk)

These incentives don't just differ. They're opposed.

Regulation works when it realigns incentives. Make privacy protection profitable. Make data abuse expensive. Make transparency rewarded and opacity punished.

Here are mechanisms that might work:

Privacy certification as a selling point: If humanoids with strong privacy protections are certified and consumers prefer them, manufacturers will implement them. This requires consumer awareness and choice.

Liability for data breaches: If manufacturers are personally liable for damages when user data is exposed, they'll invest heavily in security. Current liability rules are too weak.

Data minimization incentives: If companies are taxed for data retention (higher storage costs for longer retention), they'll naturally minimize collection and delete promptly.

Transparency rewards: If privacy audits are public and consumers choose robots with higher privacy ratings, transparent companies gain market advantage.

Individual data compensation: If users must be paid when their data is commercialized, companies will think carefully about monetization and users gain incentive to monitor what's happening.

Regulatory enforcement with teeth: Fines that actually hurt (not tiny percentages of revenue), executive liability (not just corporate liability), and mandatory remediation (not just apologies).

None of these are perfect. But together they might create enough pressure to align manufacturer incentives with user interests.

The alternative is what we've accepted in digital platforms: a world where companies know everything about you and you know nothing about what they're doing with that knowledge.

We don't have to repeat that mistake with humanoids.

Technical Standards: Making Privacy Enforceable

Regulation only works if there's a way to actually enforce it. And enforcement requires technical standards that everyone can measure against.

What might technical standards for humanoid privacy look like?

Data minimization audit: Independent verification that the humanoid collects the minimum data necessary for stated function. If it can safely assist with mobility monitoring movement, it shouldn't also collect facial expression data.

Encryption standards: All data in transit and at rest must be encrypted with specific algorithms (AES-256 or equivalent) using keys the user controls. Manufacturer-controlled encryption is insufficient.

Local processing verification: Cryptographic verification that specific data never leaves the device. The humanoid's privacy-critical processing must happen locally with mathematically verifiable proofs.

Retention compliance: Automated deletion of data based on user-defined or regulatory-mandated timelines. Data can't be kept "by accident."

Access logging: Every access to user data must be logged, timestamped, and attributable. These logs should be accessible to the user and reviewed by independent auditors.

Anonymization verification: If data is anonymized for research, statistical verification that re-identification is computationally infeasible. Not just pseudonymization (replacing names with IDs), true anonymization.

Interoperability and portability: Users should be able to migrate to a different manufacturer and take their data with them. This prevents lock-in and creates pressure for better privacy practices.

Third-party auditing: Manufacturers must allow independent security and privacy researchers to audit systems (under appropriate confidentiality agreements). No security through obscurity.

Firmware transparency: Users should be able to verify what version of software is running and have assurance that only manufacturer-signed updates can run. Otherwise, a compromised robot could spy on you without your knowledge.

These standards are technically achievable. Some companies already implement several. The question is whether they'll become mandatory.

The International Dimension: Who Sets Standards?

Humanoid robots won't stay in one country. A robot manufactured in one place will be deployed globally. This creates a coordination problem.

Imagine a scenario:

- The EU requires strong privacy protections and regular auditing

- The US requires strong innovation incentives and limited regulation

- China requires government access to certain data

- India requires local data storage

A manufacturer can't easily meet all these requirements. Either they develop multiple versions, or they develop for the most restrictive market and deploy everywhere, or they develop for the least restrictive market and face exclusion from better-regulated markets.

This coordination problem isn't new. We faced it with digital privacy (GDPR essentially became global standard), with chemicals (Montreal Protocol), with food safety.

The pattern is: one jurisdiction sets strict standards, others gradually follow because manufacturers prefer harmony over fragmentation.

EU-like privacy standards for humanoids will likely become global not because everyone agrees they're best, but because manufacturers will find it easier to build one compliant system than multiple systems.

However, this requires the EU (or equivalent) to act decisively and soon. The longer fragmented standards exist, the harder it becomes to align them.

Alternatively, industry standard-setting organizations could develop common frameworks. The IEEE, ISO, and other organizations have experience with technical standards. A "Privacy and Dignity for Humanoid Robots" standard could be adopted globally.

The risk: industry-led standards are typically weaker than government regulation because companies influence the process.

The opportunity: industry standards can be more technically precise and adaptable than government regulation, which often lags behind technology.

The likely outcome: a mix. Government regulation sets floor standards (basic minimum protections). Industry standards fill in technical details. Companies compete partly on privacy as a differentiator.

This still leaves gaps. Developing nations might not have regulatory capacity. Companies might arbitrage weaker jurisdictions. Corporate incentives might still dominate despite standards.

But it's probably better than the unregulated alternative.

The Cultural Imperative: Privacy as Human Right

Let's step back from technical details and remember what we're actually talking about.

Privacy isn't a feature. It's not a feature you can add or remove based on cost-benefit analysis. It's a human right recognized by the UN, the EU, and most democratic constitutions.

Privacy is the basis for dignity. It's the ability to control which parts of yourself you reveal to whom. It's the space where you can be yourself without performance, without judgment, without surveillance.

When we accept humanoids into intimate spaces without strong privacy protections, we're accepting a world where:

- Your body is continuously interpreted by machines

- Your emotional states are inferred without consent

- Your behaviors are recorded and analyzed

- Your vulnerabilities are documented

- Your autonomy is conditional on acceptance of observation

This isn't the future we have to accept. We have time to do better.

Privacy for humanoids isn't a technical problem with a technical solution. It's a social choice about what kind of world we want to live in. Do we want machines that respect boundaries? Or machines that maximize data collection and minimize user control?

The answer matters. Because unlike digital privacy, which we can somewhat opt out of, humanoid privacy will be inescapable. If we don't get this right, every interaction with a robot will be an act of exposure.

We can build robots that learn from interaction while respecting privacy. We can build systems where the manufacturer doesn't profit from intimate observations. We can build technology where users maintain control and dignity.

But we have to decide to do so. And we have to decide now.

Practical Privacy Checklist for Humanoid Adoption

If you're considering adopting a humanoid robot (or if you work at an organization considering deployment), here's a practical checklist:

Before Purchase:

- Research the manufacturer's privacy history. How have they handled data in other products?

- Review the privacy policy. Is it specific about what data is collected or vague?

- Check for privacy certifications. Has an independent auditor verified privacy claims?

- Understand the business model. How does the manufacturer make money? Do they profit from your data?

- Read the terms of service carefully. Can you actually control what data is collected?

- Ask the manufacturer specific questions: Where is data stored? Who has access? How long is it retained?

During Setup:

- Disable data collection features you don't need. If you only need mobility assistance, disable emotional state inference.

- Set strict privacy controls. Minimize what data leaves the robot's local system.

- Configure deletion timelines. Data should be automatically deleted on a schedule.

- Review access logs regularly. Who is accessing your data and why?

- Test transparency features. Ask the robot to explain its recent decisions.

Ongoing:

- Review privacy settings monthly. Policies change; make sure your preferences are still configured.

- Update firmware promptly. Security patches matter for privacy protection.

- Monitor for suspicious behavior. Is the robot collecting more data than it should?

- Request data exports periodically. Understand what the manufacturer knows about you.

- Delete archived data. Don't let it accumulate indefinitely.

- Watch for policy changes. Manufacturers sometimes expand data collection without notice.

These steps don't guarantee privacy. But they significantly reduce risk and send a market signal that you care about privacy.

The Path Forward: Five Critical Actions

So what actually needs to happen?

1. Government Action (Immediate, 2025-2026)

Policymakers need to establish baseline standards before widespread deployment. This means:

- Privacy impact assessment requirements

- Data minimization mandates

- User rights specifications

- Liability rules

- Enforcement mechanisms

This doesn't require waiting for perfect frameworks. Good enough now is better than perfect too late.

2. Technical Standards Development (2025-2027)

Industry organizations and academic researchers need to develop concrete technical standards. Not just principles, but measurable, testable specifications:

- Encryption requirements

- Local processing verification

- Anonymization techniques

- Auditing methods

- Interoperability standards

3. Corporate Commitment (Now)

Manufacturers should commit to privacy-first design principles:

- Publish privacy roadmaps

- Implement strong privacy protections voluntarily (before regulation forces it)

- Support third-party auditing

- Engage with ethicists and privacy experts during design

- Be transparent about what changed between versions

4. Public Literacy (Ongoing)

People need to understand humanoid privacy risks:

- Mainstream coverage of privacy implications

- Educational materials about what data humanoids collect

- Practical guidance for deployment decisions

- Community discussion about acceptable use cases

5. International Coordination (2025-2028)

Countries need to work toward harmonized standards:

- Mutual recognition of privacy certifications

- Data protection agreements

- Enforcement cooperation

- Technology transfer to developing nations

None of this is technologically impossible. None of it requires inventing new capability. It requires decision and commitment.

Conclusion: Dignity as the Starting Point

We've reached an inflection point where we still have choices about the future of human-robot interaction.

We can accept a world where humanoid robots observe us continuously, collect intimate data, and use that data in ways we don't control. We can tell ourselves it's inevitable, that this is the price of progress.

Or we can decide differently.

We can build robots that are capable and helpful while respecting human dignity. We can develop technology where privacy is mathematically enforced, not just policy-promised. We can create systems where people maintain control over what machines know about them.

This isn't theoretical idealism. It's pragmatic, it's achievable, and it's the only path that actually sustains trust.

Humanoid robots will arrive in homes and workplaces whether we're ready or not. The question is whether they arrive in a regulatory and technical environment that protects privacy and dignity, or whether they arrive in a vacuum where manufacturers make the rules.

We have years, not decades, to decide. The window is open, but it's closing.

The machines are coming. What matters now is who owns the relationship between humans and machines. Will it be a relationship built on mutual respect and privacy? Or will it be built on asymmetric observation and control?

The answer depends on decisions we make right now.

FAQ

What exactly is a humanoid robot?

A humanoid robot is a machine designed to resemble and interact with humans in human-like ways. Unlike industrial robots that are purpose-built for specific factory tasks, humanoids are designed to navigate human environments, understand human communication, and learn from human interaction. Current examples include Tesla's Optimus, Boston Dynamics' humanoid systems, and several research platforms that can walk, manipulate objects, perceive their environment, and respond to natural language. These robots combine mobile manipulation, perception, and reasoning to operate effectively in unstructured, human-designed spaces.

How do humanoids collect data differently from other smart devices?

Humanoids are fundamentally different from smartphones or smart speakers because they're physically present in space, mobile, and equipped with multiple sensor modalities operating continuously. While a phone is something you hold and can put down, a humanoid is an autonomous presence that observes movement, interprets gestures, analyzes facial expressions, detects emotional states, and builds behavioral models without explicit permission or constant awareness. A smart speaker mainly records audio when activated; a humanoid collects visual data, proprioceptive data about physical interaction, and temporal patterns across days and weeks. This continuous, multi-modal observation in shared physical space creates privacy risks that traditional digital privacy regulations weren't designed to address.

Why can't existing privacy laws protect us from humanoid robots?

Existing privacy regulations like GDPR and CCPA were designed for digital data: files, databases, records that could be deleted, accessed, or transferred. They assume humans control when data is collected and can meaningfully consent to collection. Humanoids operate in real time, making autonomous decisions about what to observe and how to respond without pausing for consent. Moreover, many of the insights a humanoid generates (emotional state, health trajectory, behavioral patterns) aren't stored as traditional data but embedded in the robot's learned models. You can't delete "your emotional profile" from a neural network the way you can delete a file. The frameworks also assume data flows centrally; humanoids distribute decision-making across the robot, manufacturer, and third parties simultaneously. New legal and technical frameworks are needed.

What is federated learning and how does it protect privacy?

Federated learning is an approach where AI systems learn from data that stays local to individual devices rather than centralizing all data. Instead of sending your health measurements to a cloud server for training, the humanoid learns locally on your device using your data. It then shares only the learned patterns (abstract mathematical representations) with the manufacturer's central system. This allows the system to improve continuously while your specific data never leaves your physical environment. The manufacturer can develop better models and offer personalized assistance without ever seeing your raw data. It's like a teacher learning general principles from multiple classrooms without needing to read every student's private notebook.

Should I trust privacy promises from humanoid manufacturers?

No. Trust should be verified through technical standards, independent auditing, and strong liability rules, not manufacturer promises. History shows that companies change policies, get hacked, or cut corners when profits are at stake. Instead of trusting promises, verify through: independent privacy certifications, transparent source code audits (or equivalent for proprietary systems), regular third-party security assessments, clear liability rules if data is misused, and market competition where privacy-respecting robots gain advantage. The best trust is trust enforced by mathematics (cryptography), regulation (liability and fines), and incentives (competitors offering better privacy), not by hoping manufacturers behave well.

What are homomorphic encryption and secure multi-party computation?

These are cryptographic techniques that allow computation on encrypted data without decrypting it. Homomorphic encryption lets you analyze health data patterns without ever seeing the raw measurements. A researcher might ask: "What percentage of users show declining mobility?" The system computes the answer without revealing any individual's data. Secure multi-party computation lets multiple parties (robot, hospital, insurance) jointly analyze data while each party keeps their information encrypted. Only the final answer is revealed, not the underlying data. Both are computationally expensive and not yet practical for all use cases, but they represent the future of privacy-preserving analysis. They transform privacy from a policy promise into a mathematical guarantee.

How should humanoids handle cultural differences in privacy expectations?

Humanoids should be designed with adaptable models that recognize and respect cultural variations in personal space, eye contact, emotional expression, family involvement, and information sharing. A robot that maintains direct eye contact is respectful in Western contexts but aggressive in many others. A robot that defers to individual patient preference might be disrespectful in cultures where family input is essential. Robots should include explicit settings allowing users and communities to configure privacy expectations, consent requirements, and interaction styles. They should be trained on diverse populations to recognize different cultural norms. And deployment should involve extensive community consultation before introduction into new cultural contexts, not just translation of Western assumptions.

What happens to humanoid-collected data if the company goes bankrupt or is acquired?

This is a critical gap in current regulation. If a humanoid manufacturer goes bankrupt, what happens to millions of intimate recordings and behavioral analyses? Current law doesn't clearly answer this. A thoughtful approach would establish clear rules: mandatory data deletion upon bankruptcy (not sale of data to highest bidder), user notification if a company with user data is acquired, and escrow arrangements where sensitive data is held by neutral third party pending user direction. Companies should be required to maintain security bonds ensuring they can secure data even if operations cease. These rules prevent scenarios where your intimate data becomes a valuable asset in bankruptcy proceedings, sold off to the highest bidder.

How can individuals maintain privacy while still getting benefits from humanoid assistance?

The ideal is not to reject humanoids but to adopt them mindfully. Practical steps include: disable non-essential data collection (if you only need mobility assistance, disable emotional inference), configure local processing where possible (process data on the robot, not in the cloud), use encryption end-to-end, review and delete stored data regularly, understand the manufacturer's business model before committing, request regular transparency reports about what data exists, set strict access controls about who can see what, and maintain the right to temporarily disable observation for sensitive activities. The goal is informed consent through technical control, not blind trust in manufacturer promises.

What regulatory models might work best for humanoid privacy?

The most effective approach combines multiple mechanisms: government baseline standards (minimum privacy requirements all manufacturers must meet), industry technical standards (specific verification methods and test suites), liability rules with real penalties (making privacy violations expensive), mandatory third-party auditing (external verification), user rights with enforcement mechanisms (individuals can actually sue), and competitive advantage for privacy-respecting products. The EU's approach of setting strict standards that manufacturers then adopt globally as the least-cost solution may become the pattern. However, this only works if standards are established before widespread deployment. Once billions of robots are in homes, regulatory change becomes nearly impossible.

Use Case: Humanoid data is becoming a critical compliance issue. Teams managing robotics deployments need to document privacy architecture, generate compliance reports, and track regulatory updates.

Try Runable For FreeKey Takeaways:

- Humanoid robots will observe continuously, capturing intimate data that exceeds traditional sensor limitations.

- Consent-based privacy frameworks fail because meaningful consent is impossible with autonomous learning machines.

- Cryptographic techniques like federated learning and homomorphic encryption make privacy enforceable by mathematics rather than policy.

- Cultural respect and dignity must be embedded in robot design, not left to interpretation.

- The regulatory window is narrow (3-5 years); standards established now will shape the technology for decades.

- Corporate incentives currently favor data collection over privacy; this misalignment must be corrected through liability and regulation.

- International coordination is essential to prevent regulatory arbitrage and ensure consistent protections.

- Practical adoption should verify privacy through standards and auditing, not trust manufacturer promises.

Key Takeaways

- Humanoid robots observe continuously through multiple sensor modalities, capturing intimate behavioral and emotional data that far exceeds traditional camera or microphone limitations.

- Existing privacy regulations designed for digital data and static storage are fundamentally inadequate for dynamic real-time interaction with learning autonomous machines.

- Cryptographic approaches like federated learning, homomorphic encryption, and secure multi-party computation enable mathematically enforceable privacy protections instead of policy-based promises.

- Privacy protection must account for cultural variations in personal space, eye contact, emotional expression, and information sharing norms across different societies and communities.

- The regulatory window for establishing protective standards is closing rapidly; most experts estimate 3-5 years remain before widespread deployment makes retroactive regulation nearly impossible.

- Corporate incentives currently favor unlimited data collection and monetization; realignment toward privacy requires liability rules, certification systems, and competitive market pressure.

- Technical standards must be developed and adopted before humanoid proliferation; standards that work retroactively are exponentially harder to implement.

- Healthcare humanoid deployment demonstrates the complexity of privacy in real-world scenarios where multiple stakeholders have competing but legitimate interests.

- International coordination is essential to prevent regulatory arbitrage where manufacturers concentrate deployment in weak-privacy jurisdictions.

- Privacy is fundamentally about human dignity and autonomy; machines designed without privacy respect cannot maintain meaningful trust or respect human agency.

Related Articles

- Europe's Sovereign Cloud Revolution: Investment to Triple by 2027 [2025]

- Stalkerware Apps Hacked: 27 Data Breaches & Why You Should Never Use Them [2025]

- Stalkerware Data Breach: 500,000 Records Leaked by Hacktivists [2025]

- DOJ Investigation: Apple, Google Pressured to Remove ICE Tracking Apps [2025]

- Flickr Data Breach 2025: What Was Stolen & How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- OpenAI's ChatGPT Ads Strategy: What You Need to Know [2025]