Introduction: When Government Efficiency Goes Wrong

Here's the thing: when a government agency tasked with reducing inefficiency accidentally becomes the inefficiency itself, something's fundamentally broken.

That's exactly what happened with the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, at the Social Security Administration. A routine audit uncovered something alarming. DOGE staffers working inside the SSA had accessed restricted personal data on millions of Americans. They shared information through unapproved channels. They signed data-sharing agreements without proper oversight. And in at least one case, they were communicating with a political advocacy group actively searching for election fraud. According to Democracy Docket, the Trump administration admitted all of this in a federal court filing in early 2025, correcting statements they'd previously made under oath. Justice Department officials essentially told the court: "Yeah, we didn't tell you the whole story before. Here's what actually happened."

This isn't just a data security incident. It's a window into how the push for government reorganization can create massive vulnerabilities. It raises uncomfortable questions about oversight, political motivations, and whether efficiency measures can coexist with protecting citizens' most sensitive information.

The Social Security Administration holds some of the most protected data the federal government maintains. Your Social Security number, earnings history, benefit records, and personal details are supposed to be behind multiple layers of security. Law enforcement needs warrants. Researchers need complex approval processes. Regular government employees need legitimate business reasons to access even fragments of the data.

Yet somehow, DOGE employees had direct access. They could pull files. Send encrypted packages to DOGE advisors. Upload information to third-party cloud servers. And nobody caught it until much later.

What makes this story even more troubling is the political angle. When you combine unrestricted data access with a stated goal of finding election fraud, you're in territory that historically makes democracies uncomfortable. The line between government efficiency and government overreach blurs fast.

Let's break down what actually happened, why it matters, and what's still unclear.

TL; DR

- The Core Problem: DOGE employees at the SSA had unauthorized access to Social Security records on millions of Americans, including names, SSNs, and earnings histories

- The Scope: Two DOGE staffers were contacted by a political group seeking to prove voter fraud, and at least one signed a data-sharing agreement without proper authorization

- The Cover-Up: The Trump administration initially made false statements to the court, later admitting these weren't true in a corrected filing

- The Vulnerability: Data was shared through unapproved channels like Cloudflare, and the SSA still doesn't know exactly what information was transmitted or if it still exists on external servers

- Bottom Line: This reveals serious gaps in how government data is protected when new agencies gain operational access to sensitive systems

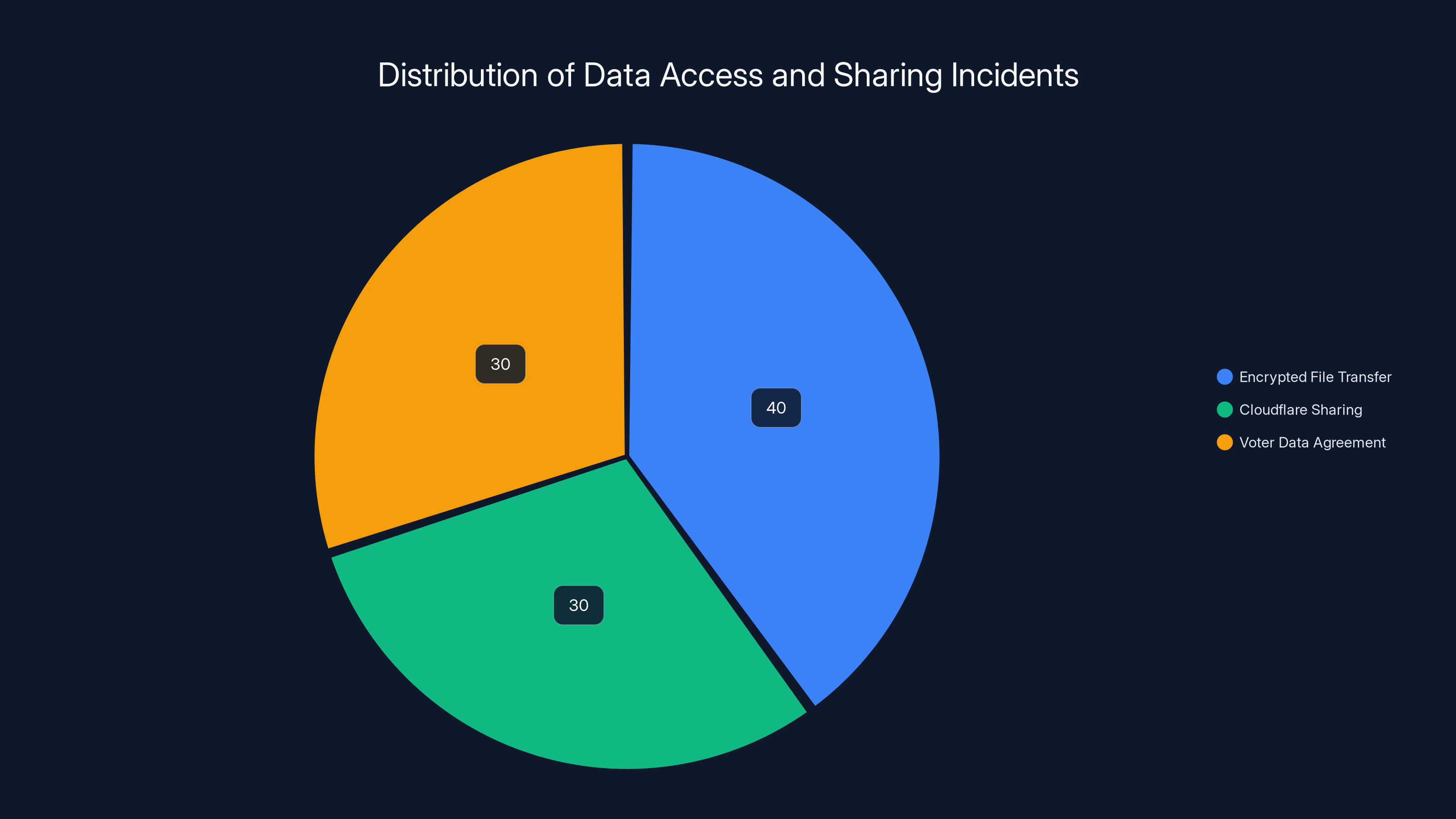

Estimated data shows that encrypted file transfer, Cloudflare sharing, and Voter Data Agreement each contributed significantly to data access incidents.

The DOGE Timeline: When Efficiency Met Access

Department of Government Efficiency wasn't created to operate like a traditional government agency. It was designed to be lean, flexible, and embedded directly into existing bureaucracies. That embedding is where the problem started.

DOGE staffers were physically present at the Social Security Administration. They had desk space. They had network access. They had institutional credentials. From a practical standpoint, they looked like regular SSA employees. But from a security and compliance standpoint, they operated in a gray zone that nobody had thought to properly regulate.

In March 2025, something happened that triggered the chain of events we're now examining. Two DOGE team members working at the SSA were contacted by a political advocacy group. This wasn't a random cold call. The group specifically wanted DOGE's help analyzing state voter rolls they'd obtained. The stated objective was straightforward: find evidence of voter fraud and overturn election results in certain states. That's not an ambiguous goal. That's an explicitly political mission.

Instead of declining the request or escalating it through proper channels, one of the DOGE members signed a "Voter Data Agreement" with the group. This agreement appears to have been a data-sharing contract that would allow the political group access to Social Security information for their election fraud research.

The problem? This agreement wasn't reviewed through SSA's standard process for data exchanges. There was no legal review. No compliance check. No approval from agency leadership. A DOGE employee simply signed it unilaterally. Neither the SSA nor the White House discovered this agreement existed until November 2025, during a completely separate audit. By then, months had passed. Nobody even knew what data might have been shared or whether the political group had actually accessed the records they were seeking.

This timeline matters because it shows how easily unauthorized access can happen when oversight structures aren't properly designed. There were no checkpoints. No approvals required. Just a DOGE employee making a decision that potentially exposed sensitive data to a political organization.

What DOGE Really Is: Efficiency or a Blank Check?

Before we go deeper into the security failures, we need to understand what DOGE actually is and why it was given the access it had.

DOGE is framed as a government efficiency initiative. The concept sounds reasonable on its surface: identify waste, redundancy, and inefficiency in federal agencies, then streamline operations. Every government could probably stand to be more efficient. Bloated processes exist. Outdated systems persist. Unnecessary positions multiply.

The problem is in the execution. To identify inefficiency, DOGE staffers need visibility into how agencies actually operate. That means access to systems, data, and processes. It means being embedded inside the agencies they're auditing. It means having the credentials and permissions necessary to see behind the curtain.

But there's a fundamental tension here. The more access you give an efficiency auditor, the more potential they have to cause harm if they abuse that access. You're essentially giving them a master key to sensitive systems, then hoping they use it responsibly.

In the SSA's case, the oversight mechanisms that should have caught this abuse were either nonexistent or too weak to matter. DOGE employees had access to systems containing personal information on millions of Americans. Nobody was apparently monitoring whether they were accessing that information for legitimate efficiency purposes or for something else entirely.

When one of those employees decided to sign a data-sharing agreement with a political group, the system failed to catch it. When they potentially shared Social Security data, nobody immediately noticed. When they uploaded information to unapproved servers like Cloudflare, it wasn't flagged as a violation.

This reveals a critical gap in how government agencies handle access by external groups embedded within their operations. The SSA trusted DOGE because DOGE was officially part of the administration. But trust without monitoring is just a recipe for problems waiting to happen.

The Political Angle: Election Fraud Searches and Data Sharing

Let's be direct about what makes this situation particularly alarming: the political motivation behind the data requests.

The political advocacy group that contacted DOGE wasn't interested in government efficiency. They were interested in voter rolls. They'd obtained state election data from somewhere and wanted to cross-reference it with Social Security records to identify discrepancies that might indicate voter fraud.

Now, the question of voter fraud is politically contentious. There are people who believe widespread fraud occurred in recent elections. Most election officials, election security experts, and election audits found no evidence of fraud at meaningful scale. But regardless of where you stand on that question, allowing a political group to access Social Security data for political purposes is a different category of problem.

It violates the Hatch Act, which prohibits federal employees from engaging in political activities in their professional capacity. When a DOGE employee signed a data agreement with a political group, they potentially violated that law. The SSA later made two referrals under the Hatch Act in late December, indicating they believed violations had occurred.

What's unclear is how much data was actually shared, and whether the political group successfully used Social Security records in their fraud analysis. The filing doesn't specify whether the Voter Data Agreement was ever actually acted upon, or whether it was just a document that sat unsigned until the audit discovered it.

But the intent is clear. A government employee was being asked to help a political organization access federal data for political purposes. And rather than refuse, they signed the agreement.

This is where government efficiency becomes government overreach. You start with a seemingly reasonable goal: reduce waste. You give people access to data. Then someone with political motivations uses that access for political purposes, and suddenly your efficiency initiative has become a tool for pursuing political agendas.

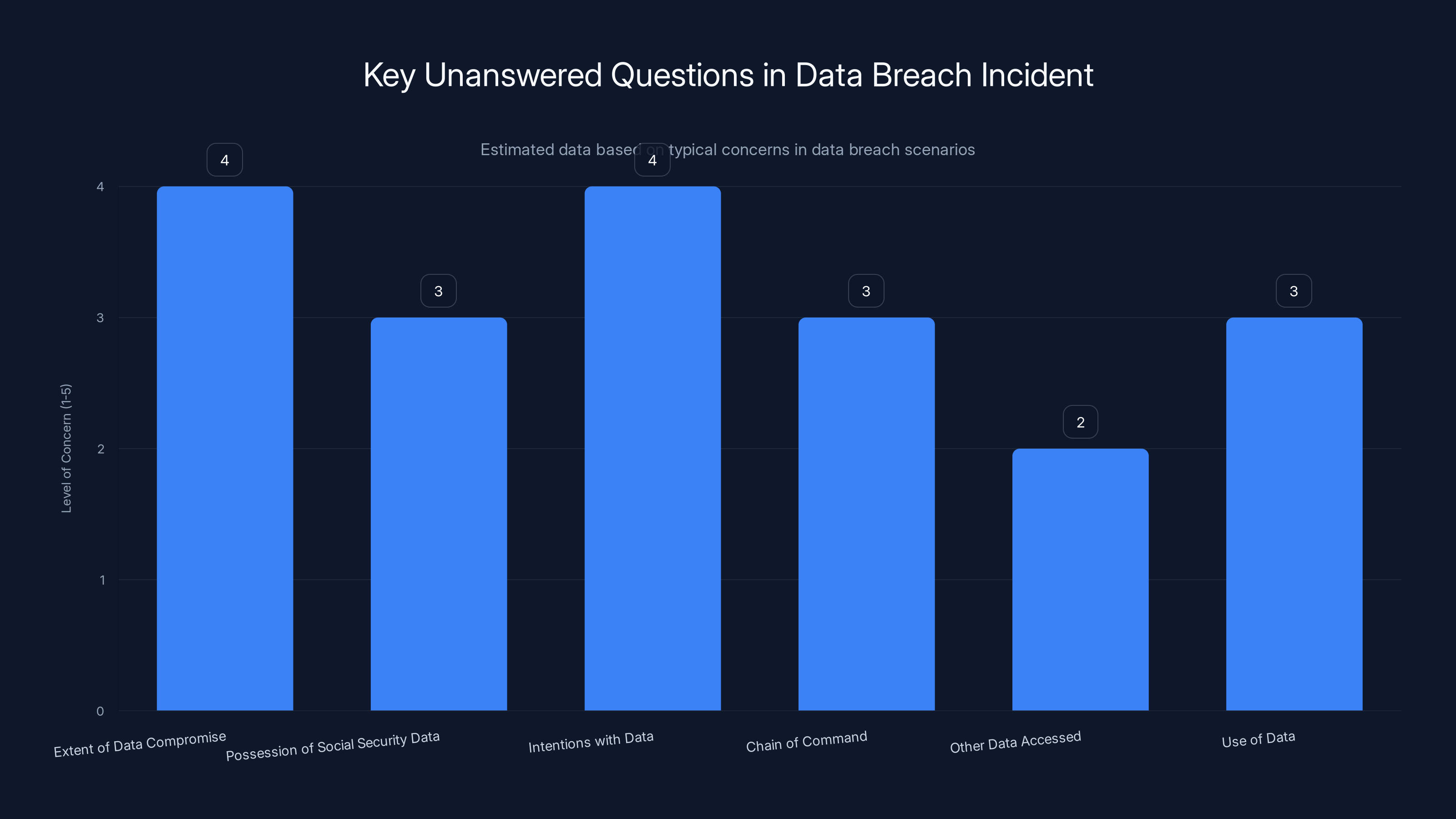

This chart estimates the level of concern for each unanswered question in the data breach incident, highlighting the need for further investigation. Estimated data.

The Data Access Problem: More Than Initially Disclosed

The Trump administration's original statements to the court were that DOGE's access to SSA systems was limited and that no personal information had been compromised. Then the audit happened. And suddenly, the SSA had to issue a correction.

Turns out, DOGE employees had more access to sensitive data than previously disclosed. Much more.

One DOGE team member sent an encrypted, password-protected file to a senior DOGE advisor. This file allegedly contained personal information on approximately 1,000 people. We're talking about actual individuals' data, potentially including Social Security numbers, names, addresses, earnings histories, or benefits information.

The SSA says it's unclear whether the DOGE advisor ever received the password to open that file. That's a remarkable thing to be unsure about when national security is at stake. Did they have the password? Did someone give it to them later? Is the file still sitting in someone's email inbox?

Neither the SSA nor DOGE appears to have a clear answer.

Beyond that one documented transfer, DOGE staffers were briefly granted access to systems containing Americans' personal information even after a federal court issued a temporary restraining order. The government claims they never actually viewed personal data with that access, but again, we're relying on their say-so. There's apparently no comprehensive audit log showing exactly what was accessed when.

Most alarmingly, a DOGE staffer ran searches for personal information on SSA systems the morning before the agency filed a court declaration stating that DOGE's access had been revoked. Think about that timeline. The declaration goes to court saying access is gone. Meanwhile, someone's literally searching SSA systems for personal data.

Then there's the Cloudflare situation. DOGE staffers shared data through Cloudflare, a third-party server that hasn't been approved for sharing sensitive government data. The SSA still doesn't know exactly what data was uploaded, whether it was deleted afterward, or whether it's still sitting on Cloudflare's servers accessible to others.

Cloudflare is a legitimate company that provides content delivery network services. But storing sensitive government data there without approval is like storing classified documents in a public storage unit. Sure, the storage unit has locks. But it's not designed for classified material, and there's no security clearance process for people accessing the facility.

The False Statements Problem: When Government Admits It Lied to Court

Perhaps the most damning aspect of this entire situation is that the Trump administration had to issue a court filing admitting it had made false statements under oath.

Let's be clear about what this means. Government attorneys stood before a federal judge and made representations about DOGE's access to SSA data. They said specific things were true. The court relied on those statements. Now, months later, the government is issuing a correction saying some of those statements weren't entirely accurate.

The government tried to soften this by saying they believed the statements were true at the time. They didn't intentionally lie. It was just that the statements weren't complete or accurate. Which is another way of saying they made statements to the court without having verified the facts first.

For instance, the government maintained that the US Digital Service, which DOGE took over, "never had access to SSA systems of record." Then they discovered that actually, a DOGE team member did send files containing personal information. So the statement was technically false.

They also said DOGE staffers' access had been revoked before filing a specific court declaration. But it turned out someone was searching for personal information the morning before that declaration was filed. So that statement wasn't quite accurate either.

These aren't trivial discrepancies. When you make statements to federal court, you're under oath. You're asking the court to make decisions based on those facts. If the facts turn out to be different, you've essentially asked the court to rule based on false information.

In this case, it meant the court might have made different decisions about temporary restraining orders, data access restrictions, or enforcement mechanisms if it had known the complete and accurate facts.

The filing suggests the SSA itself didn't have good visibility into what DOGE was actually doing. The agency couldn't say with certainty what data had been accessed, what had been shared, or what systems had been compromised. So when they made statements to the court, they were making educated guesses based on incomplete information.

That's a massive problem for government credibility and for proper oversight of sensitive data.

The Scope of Exposure: What Personal Data Was at Risk

The Social Security Administration doesn't just maintain Social Security numbers. It maintains comprehensive records on hundreds of millions of Americans. We need to understand what information could have been compromised.

For every person who receives Social Security benefits, the SSA maintains their name, date of birth, Social Security number, family relationships, earnings history, and benefit information. For people who've ever applied for benefits or even just looked up their earnings record, the SSA has extensive biographical and financial data.

That's not information you want floating around. Not because individuals are doing anything wrong, but because it's a privacy violation and because bad actors can use that data for identity theft, fraud, or surveillance.

In the case of the political group searching for voter fraud, they specifically wanted Social Security data cross-referenced with voter rolls. They were presumably looking for discrepancies: people voting in multiple states, people voting after death, people with inconsistent identifying information.

Whether or not voter fraud of that type exists at significant scale, giving a political organization access to Social Security data to conduct that analysis is inappropriate. That's personal information on millions of Americans being handed to a political group for political analysis.

The DOGE staffers who signed the Voter Data Agreement and the ones who shared information through Cloudflare didn't seem to fully grasp the sensitivity of what they were handling. They treated Social Security data like it was just another administrative dataset. You could encrypt it, upload it, share it with third parties who asked nicely.

But Social Security data isn't like that. It's one of the most protected datasets the government maintains specifically because of how sensitive it is.

How This Happened: The Oversight Failure

Now we get to the fundamental question: how did this happen? How did DOGE employees get access to restricted data, sign agreements with political groups, and share information through unapproved channels without anyone stopping them?

The answer is that oversight systems failed at multiple levels.

First, there was no clear policy about what DOGE employees could or couldn't do at the SSA. Were they just auditing efficiency? Could they access individual records? Could they share data with outside parties? These questions should have been answered before DOGE staffers ever received system access.

Second, once they had access, there was apparently no continuous monitoring of what they were actually doing. Audit logs might have existed, but either nobody was reviewing them in real time, or the logs weren't configured to flag suspicious activity.

Third, when requests came from political groups for data, there was no approval process standing between "we want the data" and "here's the data." A single DOGE employee could sign an agreement that shared federal data with a political organization.

Fourth, the SSA itself didn't have good visibility into its own systems. They couldn't explain what data had been accessed or shared until an audit forced them to look comprehensively.

These are organizational failures, not just technical failures. Yes, better data classification and access controls would help. But what really failed here was institutional rigor around who gets access to sensitive data and for what purposes.

The SSA is an agency with established protocols for data security. Those protocols exist because data breaches are serious. But when an agency is restructured and embedded with external teams, those protocols can become ambiguous. Do they still apply? Who enforces them? What if DOGE thinks the protocols are inefficient?

DOGE's entire purpose is to question whether existing processes are necessary. That's actually a valuable function. But when applied to data security protocols at an agency that maintains extremely sensitive information, questioning necessity becomes dangerous.

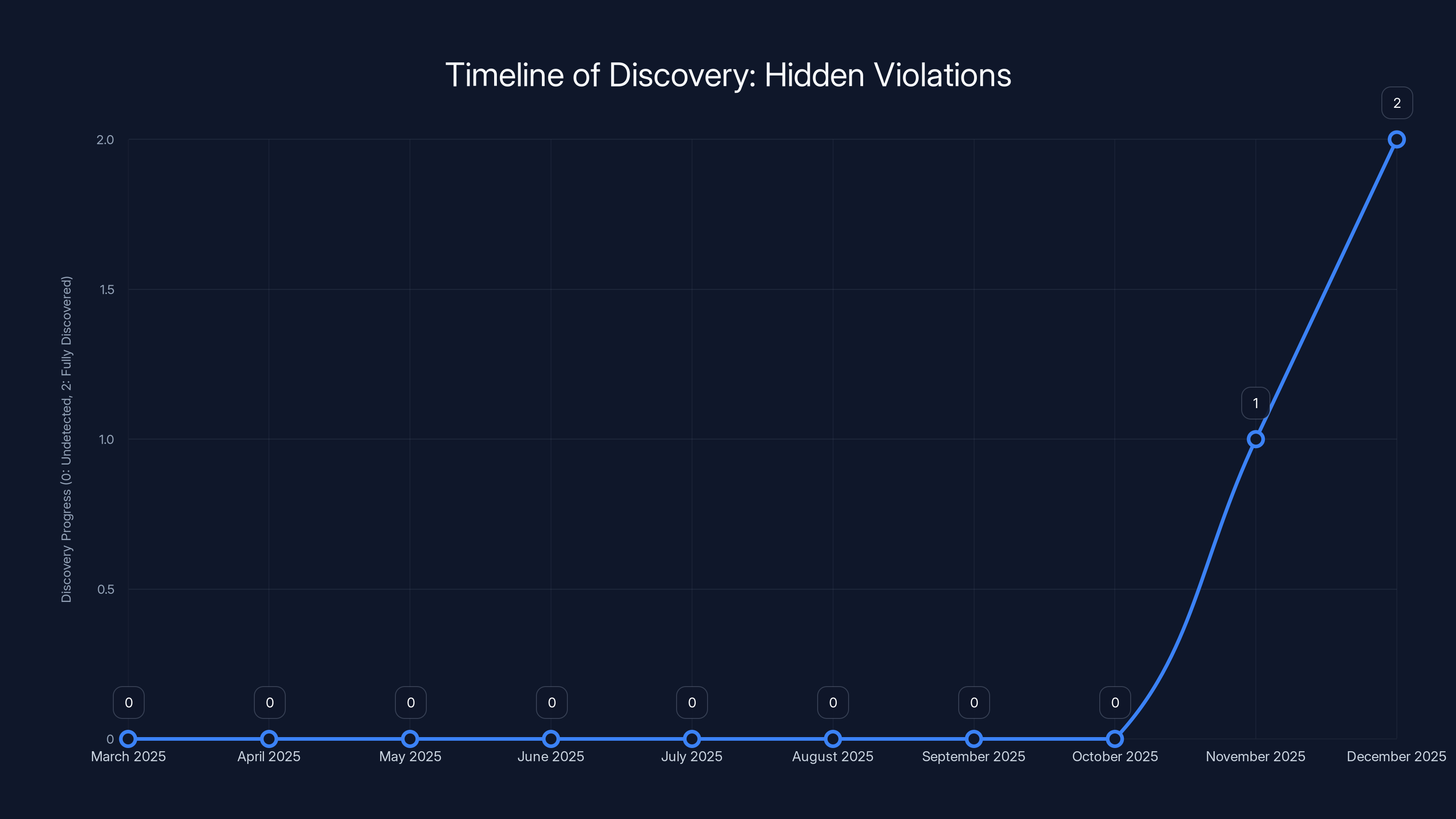

The timeline illustrates a nine-month period from the initial data sharing in March 2025 to the discovery of violations in November 2025, highlighting the delay in detection and response. Estimated data.

The Cloudflare Question: Data in the Cloud We Can't Control

One detail that deserves more attention is the Cloudflare issue. According to the court filing, DOGE staffers shared Social Security data through Cloudflare without approval. The SSA doesn't know exactly what data was uploaded or whether it still exists on Cloudflare's servers.

Cloudflare is a major content delivery network and security company. They're legitimate. They have security practices. But they're not a secure government facility designed for classified or highly sensitive data.

When you upload data to Cloudflare, it's stored on their servers, potentially replicated across multiple data centers, cached in various locations, and potentially backed up. Even if the original upload location is deleted, copies might exist elsewhere.

Furthermore, Cloudflare's terms of service almost certainly don't include provisioning for sensitive government data. The company could have compliance or legal obligations regarding law enforcement requests, government surveillance, or data subpoenas.

The fact that DOGE staffers thought uploading Social Security data to Cloudflare was acceptable shows a fundamental misunderstanding of data security. It's the kind of mistake you'd expect from people who treat data handling as just another IT task, not as a matter of national security.

And here's the thing: the SSA still doesn't know exactly what was uploaded. They have to contact Cloudflare and ask what data the SSA uploaded from which IP addresses during which time periods. Assuming Cloudflare cooperates and actually has records, this could take weeks or months to resolve.

Meanwhile, potentially sensitive information about millions of Americans has been sitting on Cloudflare's servers with no one quite sure what it contains.

Hatch Act Violations: When Government Workers Become Political Operatives

The Hatch Act is a 1939 law that prohibits federal employees from engaging in political activities in their professional capacity. It's not a restriction on what they can do in their private lives. It's a restriction on using government positions or resources for political purposes.

When DOGE employees signed a data-sharing agreement with a political advocacy group seeking to prove voter fraud, they were arguably violating the Hatch Act. They were using their positions as government employees and their access to government data for a political purpose.

The SSA identified this concern and made two referrals to the Office of Special Counsel, which investigates Hatch Act violations. Potential violations can result in termination, debarment from federal service, or even criminal charges depending on severity.

But here's what's interesting about the Hatch Act in the context of DOGE. DOGE's entire purpose is political. It's a political initiative launched by a political administration to accomplish political goals. So there's tension between DOGE's mission and the Hatch Act's restrictions.

If DOGE employees are supposed to reduce government waste, but they can't engage in political activities, how do they handle situations where efficiency and political goals align? What if they discover something that's technically wasteful but also politically controversial?

These are genuine tensions that nobody seems to have thought through before embedding DOGE inside agencies like the SSA.

The political group that contacted DOGE was specifically seeking to prove election fraud. That's explicitly political. It's not a neutral government function. It's not about efficiency. It's about supporting political claims about voting irregularities.

When DOGE employees engaged with that group and provided data, they crossed from government efficiency into politics. And they did so using access that was granted for efficiency purposes.

This is exactly what the Hatch Act is designed to prevent: government employees using their official position and access to pursue political objectives.

What We Still Don't Know: Unanswered Questions

The court filing answers some questions but raises many others that remain frustratingly unanswered.

First: how much personal data was actually compromised? The filing mentions 1,000 people whose data was in the encrypted file sent to a DOGE advisor. But how much data was shared through Cloudflare? How many people's information was potentially accessed through the various security failures documented in the filing?

Second: does the political group actually have Social Security data? The filing indicates they sought it and DOGE employees signed an agreement to provide it. But did the actual data transfer occur? If it did, do they still have it?

Third: what specifically was the political group planning to do with Social Security data? Were they trying to match it against voter rolls to find discrepancies? Were they planning to publicly release matched data? Were they planning to hand it to election officials or law enforcement?

Fourth: what's the chain of command here? Did DOGE leadership know about these activities? Was this a rogue employee action, or was it authorized at some level? The filing doesn't clearly specify who knew what and when.

Fifth: what other data might DOGE have accessed at the SSA or at other agencies where they're embedded? This incident was discovered in an audit. How many other incidents might exist that nobody's looked for?

Sixth: did the political group successfully use Social Security data for their purposes? Have they shared it with others? Is it posted somewhere online under a different label?

These are the questions that Congress should be asking, that election officials should be asking, and that the public should be demanding answers to.

The Broader Implications: Government Efficiency vs. Government Overreach

This incident raises important questions about how we balance government efficiency with government restraint.

Government agencies absolutely should be efficient. Waste is real. Outdated processes persist. Unnecessary positions exist. There's legitimate value in having people come in and say, "Why are we doing this? What would happen if we stopped?"

DOGE's concept isn't inherently bad. The execution, though, has revealed the tension between giving auditors sufficient access to actually audit something and preventing them from abusing that access.

When you give someone access to sensitive systems, you're making a trust bet. You're saying, "We trust you'll only use this access for legitimate purposes." When that bet doesn't pay off, the consequences can be serious.

In this case, the trust failed. Employees used access granted for efficiency purposes to engage with political groups. Data flowed to unapproved locations. Agreements were signed unilaterally. And nobody caught it until months later.

The bigger question is whether this was a unique failure or a symptom of a systemic problem with how DOGE is structured and embedded within agencies.

If DOGE is present in dozens of federal agencies, and each one has the same oversight gaps we're seeing at the SSA, then this isn't just a Social Security problem. It's potentially much larger.

We need to know:

- How many other agencies have DOGE embedded in them?

- What data access do DOGE employees have at each agency?

- What oversight mechanisms exist?

- How often is data access actually audited?

- What training do DOGE employees receive on data security and Hatch Act compliance?

- What happens when efficiency goals conflict with security protocols?

These answers will determine whether DOGE becomes a tool for legitimate government improvement or a mechanism for political data collection dressed up as efficiency.

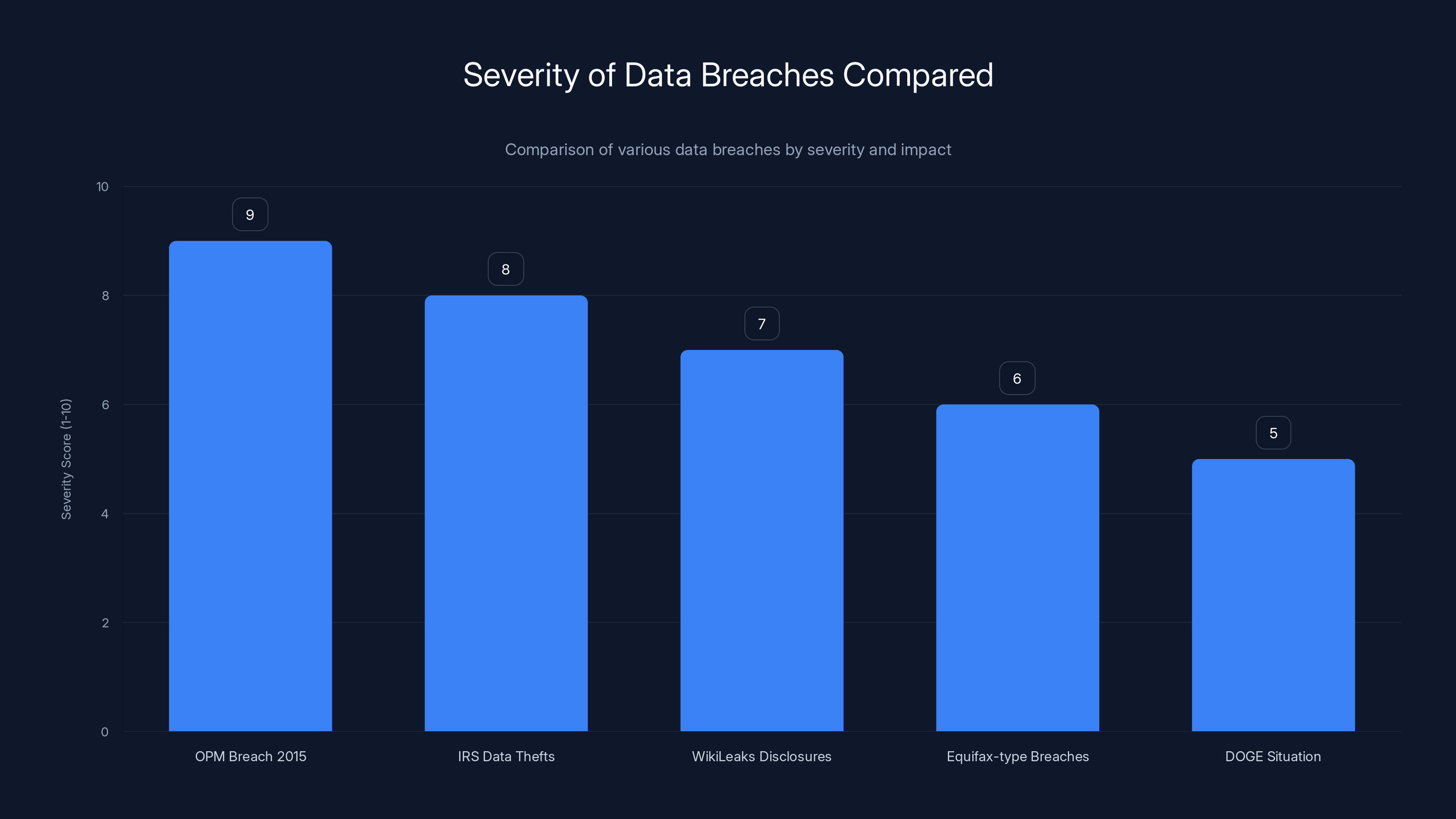

The DOGE situation ranks lower in severity compared to historical breaches like the OPM breach, but its intentional misuse of data for political purposes adds a unique concern. Estimated data.

Legislative and Regulatory Response: What Needs to Happen

Congress should be legislating guardrails around DOGE's access to federal data. Right now, there aren't clear statutory limits on what DOGE can access or how that access can be used.

That's a legislative failure. Agencies shouldn't have to guess at what's allowed. Congress should have specified exactly what DOGE employees can and cannot do with federal data, what approval processes are required, and what audit mechanisms must be in place.

Similarly, federal agencies themselves need to update their own policies. Every agency where DOGE operates should have explicit policies governing data access by external teams. These policies should cover what data they can access, for what purposes, and what oversight mechanisms will be in place.

The SSA should implement real-time monitoring of all data access. Not just audit logs that get reviewed quarterly, but actual alerts when unusual access patterns occur. If a DOGE employee suddenly starts pulling records on thousands of people, that should trigger an immediate review.

There should also be mandatory training for anyone getting access to sensitive data. Data security training. Hatch Act training. Specific protocols for the agency. This isn't burdensome. It's responsible.

Finally, there should be consequences. If DOGE employees violated the Hatch Act by engaging with political groups, they should face discipline. If they shared data inappropriately, they should lose access. If they lied to the court, there should be accountability.

Without consequences, what's the incentive to follow rules? If you can share sensitive data with political groups and the worst outcome is that you get moved to a different assignment, then the system isn't working.

The Voter Fraud Angle: Why This Matters Politically

We should address this directly: the involvement of a political group seeking to prove voter fraud adds a layer of concern that goes beyond typical government mismanagement.

Election integrity is important. If fraud is occurring at scale, that's a serious problem that needs to be addressed. But the process matters. You don't let a political group access federal databases to conduct their own fraud investigation. There are proper channels for that: law enforcement, election officials, authorized researchers.

When you let unauthorized groups access voter data and Social Security data and combine them, you're creating situations where:

- Data could be misused to intimidate or harass voters

- Innocent people could be flagged as "suspicious" based on flawed analysis

- Political groups could claim to have found fraud they actually didn't find

- Federal data becomes a tool for political campaigns

If the political group was legitimate, they could have requested data through proper channels. They could have filed FOIA requests. They could have worked with law enforcement. Instead, they contacted DOGE directly and sought direct access to data.

And DOGE employees accommodated that request. That's the part that's most concerning. Not just the data access, but the willingness to provide it to a political group for a political purpose.

This is exactly the kind of government overreach that surveillance and data protection laws are supposed to prevent. When political groups start getting access to comprehensive government databases, we're in new territory. And not in a good way.

Timeline of Discovery: How Long Did This Stay Hidden?

The timeline here is important because it shows how long these violations persisted before detection.

March 2025: DOGE employees are contacted by a political advocacy group seeking to analyze voter fraud. One employee signs a Voter Data Agreement.

Months pass: Presumably, data might be shared, analyzed, or used. Nobody inside the SSA knows this is happening. Nobody is monitoring for it.

November 2025: The SSA conducts an audit. During this audit, they discover the Voter Data Agreement for the first time. They learn that DOGE employees had accessed more data than previously disclosed. They discover the Cloudflare situation.

Late December 2025: The SSA makes Hatch Act referrals based on the violations they discovered.

Early 2025: The Trump administration issues a corrected court filing admitting that previous statements to the court weren't entirely accurate.

That's roughly nine to ten months between when violations occurred and when they were detected internally. And even after internal discovery, it took weeks to prepare a court filing correcting prior statements.

During all that time, nobody outside the government knew about any of this. The public didn't know. Congress didn't know. The court didn't know, technically, until the corrected filing was submitted.

That's a long runway for potential damage. If the political group did obtain Social Security data, they had months to use it, share it, or deploy it in ways we might never discover.

This points to a critical failure in government transparency and accountability. Agencies shouldn't discover that they've been violating data security protocols only when auditors stumble onto the issues. There should be continuous monitoring and immediate escalation when violations are suspected.

Precedent and Precedent-Setting: Why This Matters for Future Administrations

What happens with this situation sets precedent for how future administrations handle data access by new agencies or initiatives.

If DOGE employees face no meaningful consequences for sharing data with political groups and lying to the court, then you've just established that it's acceptable for efficiency initiatives to double as political data collection programs. The next administration will notice. They'll think, "If the last administration got away with this, so can we."

Precedent doesn't have to be formal. It can be as simple as: nobody faced serious consequences, so it must have been okay.

Conversely, if there are real consequences, if Congress gets upset, if agencies implement strict data access controls, then the precedent becomes: don't mess with sensitive government data, no matter what your nominal purpose is.

We're at a precedent-setting moment. How Congress responds, how agencies respond, how courts respond to the Hatch Act violations, all of that will influence how future government efficiency initiatives handle data access.

The election fraud search angle is particularly important for precedent. If a political group can access federal databases to search for election fraud, that opens up possibilities for future political groups to do the same for their causes. That's not a good precedent.

Government data should be off-limits to political campaigns and advocacy groups, even when those groups think they're pursuing legitimate objectives.

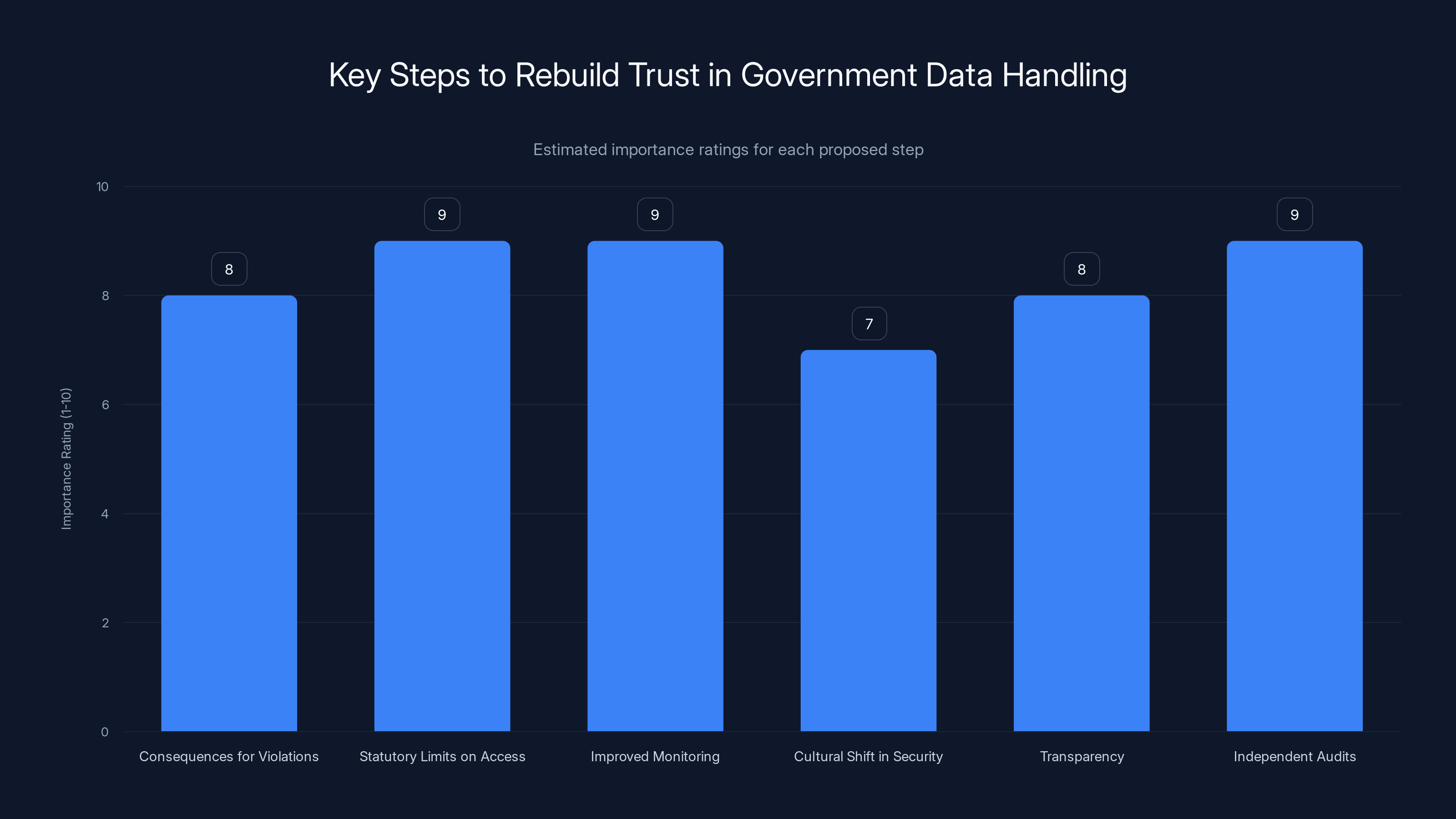

Statutory limits on data access, improved monitoring, and independent audits are rated as the most crucial steps to rebuild trust in government data handling. Estimated data.

What Happened to Oversight: The Mechanisms That Didn't Work

There should have been multiple points where this situation was caught and stopped. Let's map out where oversight failed:

First checkpoint: When DOGE employees were granted access to SSA systems, someone should have defined exactly what data they could access and for what purposes. Nobody did.

Second checkpoint: When a political group requested data, someone should have checked whether that request was appropriate. It wasn't processed through any approval mechanism.

Third checkpoint: When a DOGE employee signed a data-sharing agreement, that should have triggered a legal review. It didn't.

Fourth checkpoint: When data was being transferred or uploaded to external services, that should have been monitored and flagged. It wasn't.

Fifth checkpoint: Audit logs should have been reviewed regularly to spot unusual access patterns. They apparently weren't.

Every single one of these checkpoints failed. That's not a coincidence. That's a systemic breakdown in how the SSA manages access to sensitive data when external teams are embedded within the agency.

The question is whether this is specific to the SSA or a broader issue across federal agencies. If DOGE is similarly embedded in the Department of Treasury, the IRS, the Department of Defense, and other agencies with sensitive data, then we're potentially looking at the same oversight failures multiplied across dozens of organizations.

That would suggest the problem isn't just at the SSA. It's in how DOGE itself is structured and how federal agencies have accepted DOGE's presence.

The Courts' Role: How Judicial Oversight Works Here

The reason we know about all this is because it came out in a court filing. A federal court in Maryland had issued a temporary restraining order regarding DOGE's access to SSA data. The court was actively overseeing the situation.

When the Trump administration had to correct its previous statements to the court, that's essentially the court saying: "You didn't tell us the truth. Now we need the actual facts."

Courts have power in these situations. They can enforce data security protocols. They can order agencies to implement stronger oversight. They can hold government officials in contempt if they continue to provide false statements.

The question is whether the court will actually use that power. Will there be meaningful enforcement? Will there be sanctions against the government for the false statements? Will there be orders requiring specific data security improvements?

Or will this blow over, the court filing sits in the record, and things continue much as before?

Judicial oversight of government data practices is one of the important checks we have. If courts are willing to actively oversee how government handles sensitive data, that's a significant constraint on abuse. If courts treat it as too political or too complicated, then that check weakens.

In this case, we're about to find out which approach the Maryland federal court takes.

Social Security Administration Accountability: Who Knew What

The SSA itself isn't blameless in this situation. Yes, DOGE employees were the ones who accessed and shared data. But the SSA granted the access. The SSA failed to monitor what was happening. The SSA made false statements to the court.

Who made these decisions? Who approved DOGE's access to sensitive systems? Who failed to implement monitoring? Who signed off on the false statements to the court?

These are accountability questions that should be answered. If agency leadership knowingly allowed DOGE to access sensitive data without proper oversight, that's one category of problem. If they negligently failed to implement proper oversight, that's a different category but still a serious problem.

The SSA's recent leadership under the Trump administration likely includes people who were supportive of DOGE's mission. That could create reluctance to strictly monitor DOGE activities. When you're working toward similar goals as an external team, you're less likely to scrutinize what they're doing.

But that's exactly when oversight becomes most important. When you're aligned with someone, you're most likely to overlook their mistakes or let slide things you'd stop if they were external contractors from a competing firm.

Moving forward, the SSA needs leadership and structures that can simultaneously work with DOGE while maintaining serious oversight of data access.

What the White House Knew: Communication Lines and Responsibility

The court filing indicates the White House was involved in the corrections to the court. The question of what the White House knew about these violations and when they knew it is important for understanding whether this was a rogue operation or a systemic failure.

Did White House officials know that DOGE employees were sharing data with political groups? Did they know about the Hatch Act violations before the SSA discovered them? Did they authorize these activities or were they surprised to discover them?

These are questions the House or Senate could ask through oversight hearings. They're legitimate questions about executive branch accountability.

If White House officials knew about the data sharing with political groups and either approved it or deliberately ignored it, that's a serious abuse of power issue. If they didn't know and discovered it only when the SSA conducted its audit, that's a serious management failure.

Either way, the White House has responsibility for what agencies under its purview are doing with federal data.

The timeline highlights the sequence of events from the initial contact with a political group in March 2025 to the discovery of the unauthorized agreement in November 2025. Estimated data.

What Individuals Who Worked at DOGE Should Have Known

We should also consider the individuals involved. DOGE employees who signed agreements with political groups and shared data with them presumably didn't wake up thinking they were going to violate the Hatch Act and compromise federal data security.

More likely, they thought they were being efficient. The political group asked for data, they had access to data, so they provided it. From their perspective, maybe they thought they were helping identify actual fraud. Maybe they thought efficiency meant not being overly cautious with data sharing.

But that's not an excuse. Federal employees, and especially employees working with sensitive personal data, have responsibility to follow protocols regardless of how they personally view those protocols' necessity.

If the protocols seem inefficient, the proper response is to go through channels to have them changed. It's not to ignore them unilaterally.

DOGE employees who accessed and shared sensitive data likely knew this was out of bounds. When you're sending encrypted files to DOGE advisors and uploading things to Cloudflare, you're not following standard procedures. You know that. You're doing it anyway.

That's where personal accountability comes in. These aren't just system failures. These are choices made by individuals who likely knew those choices weren't appropriate.

The FOIA Angle: What Could Be Made Public

There's probably a lot more information about this situation that hasn't been made public yet. Congressional oversight committees could demand documents. Journalists could file FOIA requests. The public could push for transparency.

Key information that should be available:

- The actual Voter Data Agreement that was signed

- Communications between DOGE employees and the political group

- A detailed list of what data was shared and when

- The audit report that discovered the violations

- Email and communication records from DOGE leadership

- Records of what happened to the data shared through Cloudflare

FOIA requests are slow, but they can compel disclosure of information that the government wouldn't otherwise reveal. They're an important tool for public accountability.

Journalists and government transparency advocates should be pursuing these requests aggressively. The public has a right to know exactly what happened with their personal data.

Comparison to Other Data Breaches: How This Stacks Up

In the context of major data breaches and government mishandling of sensitive information, how serious is this situation?

On one hand, it's relatively contained. The number of people whose data was potentially compromised directly is in the hundreds or thousands, not millions. The data that was shared was shared with a political group, not sold on the dark web or posted publicly.

On the other hand, the involvement of federal employees and government data makes it more serious than a typical corporate data breach. The Hatch Act violations mean political activity was involved. The fact that it went undetected for months means the data was vulnerable for a long time.

Historically, government mishandling of data has included:

- The 2015 Office of Personnel Management breach that exposed security clearance information on millions of federal employees

- Various IRS data thefts and breaches involving tax information

- State department cable disclosures (Wiki Leaks)

- Numerous Equifax-type corporate breaches involving government records

This DOGE situation is less catastrophic than those situations but more concerning because it involved intentional data sharing for political purposes rather than accidental exposure or outside hacking.

Intentional misuse of government data is arguably worse than a breach. It means government employees themselves chose to share sensitive information inappropriately.

What Happens Next: Potential Consequences and Outcomes

Several things could happen from here:

First, there could be criminal investigations. The Justice Department has the authority to investigate whether federal employees violated laws by sharing data inappropriately or violating the Hatch Act. Criminal charges are possible, though typically reserved for the most serious violations.

Second, there could be administrative discipline. DOGE employees involved could be terminated, suspended, or have their security clearances revoked. This is more likely than criminal charges.

Third, there could be congressional investigations. Congress could hold hearings, subpoena documents, and demand testimony from government officials. This could be very public and politically contentious.

Fourth, there could be civil litigation. Affected individuals whose data was shared could potentially sue for privacy violations. This would be challenging because the government has sovereign immunity in many contexts, but it's theoretically possible.

Fifth, there could be new regulations and policies. Congress could pass legislation restricting DOGE's data access. Agencies could implement stronger oversight mechanisms.

Or, and this is also possible, the situation could fade from public attention, not much happens in terms of consequences, and the precedent becomes that data mishandling by efficiency initiatives isn't that serious.

Which outcome occurs will depend partly on how much political pressure builds around the issue and partly on how aggressively Congress pursues oversight.

Data Security Lessons: What Agencies Should Learn

There are specific lessons here that every federal agency should take from this situation:

First, external teams with system access need the same data security restrictions as internal employees. Don't assume that because someone is from the executive office, they have a blanket exemption from data handling protocols.

Second, data access should be granular and purpose-specific. You shouldn't grant broad access to entire databases. You should grant access to specific data elements for specific purposes.

Third, real-time monitoring of sensitive data access is essential. Audit logs that get reviewed quarterly aren't sufficient. You need alerts when unusual access patterns occur.

Fourth, approval processes for data sharing should be automatic and mandatory. A DOGE employee shouldn't be able to sign a data-sharing agreement unilaterally. There should be a review and approval chain.

Fifth, train everyone with data access on both the technical and ethical dimensions of data security. It's not just about passwords and encryption. It's about understanding why the data is sensitive and why it needs to be protected.

Sixth, have an escalation procedure for when data access requests seem inappropriate. If someone from a political group is asking for data, that should be flagged for legal review.

These aren't complicated solutions. They're standard data security and governance practices that any organization handling sensitive information should have.

The fact that the SSA didn't have them in place suggests either inadequate procedures or inadequate enforcement of procedures that existed.

The Bigger Picture: Government in the Digital Age

This incident sits at the intersection of several larger trends in how government operates.

First, there's the trend of bringing in outside teams and initiatives to reform government. Sometimes this is good. Fresh perspectives can identify real problems. But when those teams have direct system access, there's potential for abuse.

Second, there's the tension between government efficiency and government restraint. You need government to be reasonably efficient. But not at the cost of accountability and proper process. Sometimes proper process means things take longer.

Third, there's the challenge of government accountability in the digital age. It's easier than ever to access or copy large volumes of data. It's harder than ever to track what's happened to data once it's left its original home.

Fourth, there's the politicization of government functions. When efficiency initiatives become intertwined with political goals, the lines blur between appropriate government action and political abuse of government systems.

This DOGE situation touches on all of these broader trends. It's a symptom of deeper tensions in how government operates when confronted with demands for efficiency, accountability, and proper data handling.

What Citizens Can Do: Demanding Accountability

If you're concerned about this situation, there are actual steps you can take to demand accountability:

Contact your congressional representatives and senators. Demand that they hold hearings about DOGE's data access and practices at federal agencies. Demand that they investigate whether similar violations are occurring at other agencies.

File FOIA requests for information about DOGE's activities at agencies. Request communications, data access logs, and audit reports.

Monitor news sources and government transparency organizations like the Government Accountability Project and the Project on Government Oversight (POGO). They often cover these issues and can provide updated information as the situation develops.

If you believe your Social Security data was involved in the breach, you can file a complaint with the Office of Inspector General at the SSA.

Talk about this with friends and family. Help them understand that this isn't just a technical issue or a government administration issue. It's a fundamental question about whether government agencies properly protect citizens' personal information.

Demand that your representatives support legislation requiring explicit data access restrictions for DOGE and similar initiatives.

These actions might seem small, but they matter. Government responds to constituent pressure. If enough people demand accountability, oversight, and stronger data protections, those demands have weight.

The Path Forward: Rebuilding Trust in Government Data Handling

Restoring public trust in government data handling requires demonstrable action, not just statements.

First, there need to be real consequences for the violations that occurred. People who shared data inappropriately should face discipline. That sends a signal that the rules matter.

Second, Congress needs to pass clear statutory limits on data access by external initiatives. DOGE shouldn't have open-ended access to sensitive databases. The access should be specific, documented, and authorized through proper channels.

Third, agencies need to implement better monitoring, not just audit trails. Real-time alerts when unusual data access occurs. Continuous review of logs, not quarterly reviews.

Fourth, there needs to be a cultural shift. Data security should be seen as essential, not as an obstacle to efficiency. If an efficiency improvement requires compromising data security, the answer is that it's not worth the tradeoff.

Fifth, transparency is important. Citizens should be able to understand how their personal information is being handled by government agencies. There should be public reporting on data security incidents, even when no data is actually compromised.

Sixth, there should be regular independent audits of data access at sensitive agencies. Not audits that agencies conduct themselves, but independent audits that report to Congress.

These steps take time and political will. But they're necessary if we want citizens to trust that their Social Security data, tax records, and other personal information held by government is actually protected.

Conclusion: When Efficiency Becomes Recklessness

The DOGE data access situation at the Social Security Administration reveals a fundamental tension that government will continue to grapple with: how to embrace efficiency without opening the door to abuse.

DOGE wasn't created to mishandle data or violate the Hatch Act. It was created to identify and eliminate waste. But by embedding DOGE directly within agencies and giving them broad system access without proportionate oversight, the administration created the conditions for exactly what happened.

Now, when a political group requested data for election fraud analysis, DOGE employees said yes. When asked to sign a data-sharing agreement, they signed it. When they wanted to share information through Cloudflare, they did it. At each step, normal oversight mechanisms either didn't exist or weren't active.

The SSA discovered this only through an audit nine months later. The court learned about it only when the government corrected its prior false statements. The public learned about it through a reporting of a court filing.

This is how government accountability fails. Not with dramatic revelations, but through slow accumulation of small oversights that compound into major problems.

What happens next matters. If Congress forces real accountability, if agencies implement better oversight, if there are meaningful consequences for the people involved, then maybe this becomes a turning point. Maybe government learns that efficiency and data security aren't opposites, they're requirements that must be simultaneously satisfied.

If nothing much happens, if people lose interest, if the administration smooths this over, then the precedent becomes clear: efficiency initiatives can access sensitive data with limited oversight, share it with political groups, and face minimal consequences. The next administration will notice. They'll expand on it.

Right now, we're at the pivot point. The question is whether this incident becomes a catalyst for stronger government data protections or just another government failure that fades from memory.

For the millions of Americans whose Social Security data was potentially accessed, whose information might have been shared with a political organization, the stakes are real. This isn't abstract. It's your personal information. Your privacy. Your right to not have government agencies hand your data to political groups without your consent.

Holding government accountable for protecting that information is everyone's responsibility. Congress. Courts. Agencies. Oversight bodies. And ultimately, citizens who demand better.

The DOGE data access situation shows what happens when we get the balance wrong. Now we have a chance to get it right.

FAQ

What exactly did DOGE do with Social Security data?

DOGE employees at the Social Security Administration accessed personal records containing names, Social Security numbers, earnings histories, and benefits information on millions of Americans. They sent an encrypted file containing data on approximately 1,000 people to a DOGE advisor, shared information through the Cloudflare server (an unapproved third-party service), and signed a Voter Data Agreement with a political advocacy group seeking to analyze voter fraud, though it's unclear how much data was actually transferred under that agreement.

Why did the Trump administration admit this in a court filing?

The Trump administration was in a lawsuit with unions representing government workers, and a federal court had been overseeing DOGE's access to SSA data. When the government conducted an internal audit in response to the lawsuit, it discovered that previous statements it had made to the court about DOGE's data access limitations weren't entirely accurate. To comply with court orders and rules requiring truthfulness in legal filings, the administration had to issue a corrected statement admitting the broader access and violations that had occurred.

What is the Voter Data Agreement and why is it problematic?

The Voter Data Agreement was a data-sharing contract signed by one DOGE employee with a political advocacy group seeking to analyze state voter rolls for evidence of voter fraud and potentially overturn election results in certain states. It's problematic because it gave a political group access to federal data for explicitly political purposes, violated the Hatch Act which prohibits federal employees from engaging in political activities during their official duties, and was never properly reviewed through the SSA's data governance process that's designed to ensure sensitive data isn't inappropriately shared.

Did the SSA know this was happening before the court filing?

No. The SSA discovered all of these violations during an internal audit in November 2025, roughly nine months after the initial contact between DOGE employees and the political group occurred in March 2025. The agency had no real-time monitoring in place to detect when sensitive data was being accessed or shared inappropriately. The violations went undetected because oversight mechanisms that should have caught them either didn't exist or weren't being actively used.

What does "off-limits Social Security data" mean in the original headline?

"Off-limits" refers to Social Security data that DOGE employees weren't supposed to have access to. While DOGE was granted some legitimate access to SSA systems for efficiency auditing purposes, the actual scope of access they obtained was broader and included more sensitive personal information than they should have had. The data was "off-limits" both in the sense that specific data elements were beyond what their access should have included, and in the sense that sharing it with external political groups violated federal data protection rules and policies.

What could happen to the DOGE employees involved?

Potential consequences include administrative discipline (suspension, termination, loss of security clearances), Hatch Act violations which the SSA has already referred for investigation by the Office of Special Counsel, potential civil litigation from affected individuals, and in theory criminal charges, though criminal prosecution of federal employees for data mishandling is relatively rare. What actually happens depends on how seriously oversight bodies and the Justice Department choose to pursue accountability.

Is my Social Security data safe now?

If your data was among the approximately 1,000 records in the encrypted file, or if it was included in data shared through Cloudflare or with the political group, it's potentially compromised. The SSA doesn't yet know exactly what data was shared or whether it still exists on external servers. You should place a fraud alert on your credit reports, consider a credit freeze, and monitor your accounts for suspicious activity. The SSA or government should be communicating directly with potentially affected individuals, though that hasn't happened yet based on public information.

Why did DOGE have access to this data in the first place?

DOGE was embedded within the SSA as part of the government efficiency initiative. To identify waste and inefficiency, DOGE employees needed some access to see how the agency operated. However, the access provided was too broad, purpose-specific restrictions weren't clearly defined, and oversight mechanisms to monitor how that access was actually being used weren't adequately implemented. Essentially, the SSA granted access without proportionate safeguards, trusting that DOGE would only use it appropriately.

What is the Hatch Act and why does it matter here?

The Hatch Act is a federal law prohibiting government employees from engaging in political activities in their official capacity or using their government position for political purposes. When DOGE employees signed a data-sharing agreement with a political group seeking to prove election fraud and potentially supported that group's political mission using federal data, they violated the Hatch Act. The SSA identified this as a problem and referred the matter for investigation, potentially leading to discipline against the employees involved.

Key Takeaways

- DOGE employees at SSA accessed restricted personal data on millions of Americans without proper authorization or oversight

- One DOGE employee signed a Voter Data Agreement with a political group explicitly seeking to prove election fraud, violating the Hatch Act

- Data was shared through unapproved channels like Cloudflare, and the SSA still doesn't know exactly what was transmitted

- The Trump administration made false statements to federal court about DOGE's data access, later issuing corrections that admitted broader violations

- Nine-month gap between March violations and November discovery shows critical failures in real-time monitoring and data governance

![DOGE Social Security Data Breach: What Happened & Why It Matters [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/doge-social-security-data-breach-what-happened-why-it-matter/image-1-1768950458416.jpg)