The DOJ's Historic Data Release Gone Wrong

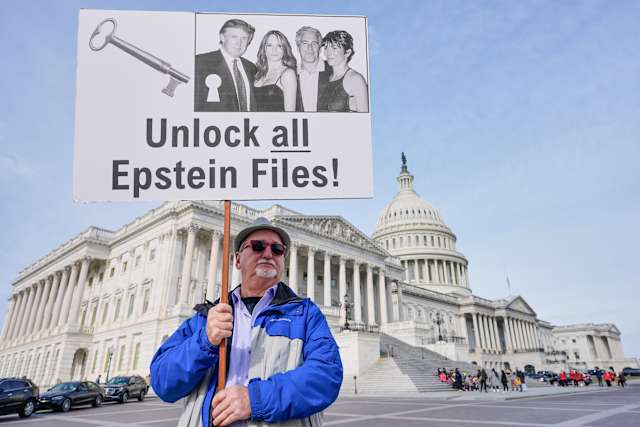

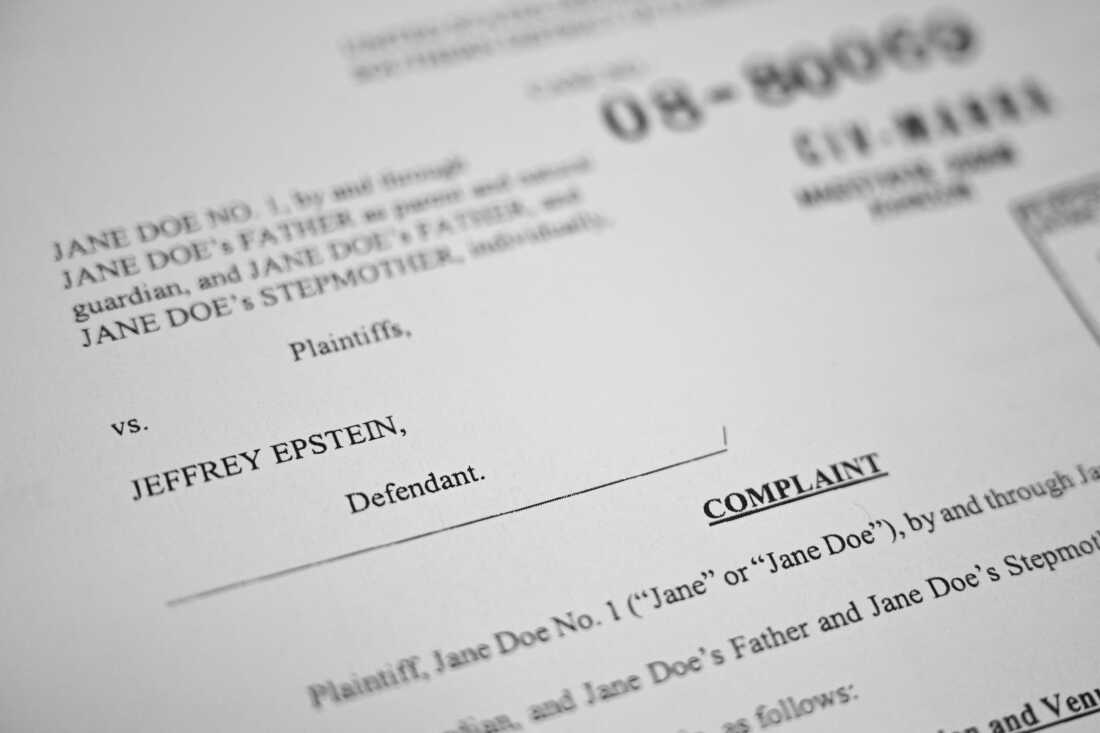

Last week, the Department of Justice released over 3 million pages of files related to Jeffrey Epstein in what was supposed to be a landmark moment for government transparency. Instead, it became a cautionary tale about how even well-intentioned institutional efforts can fail victims at massive scale.

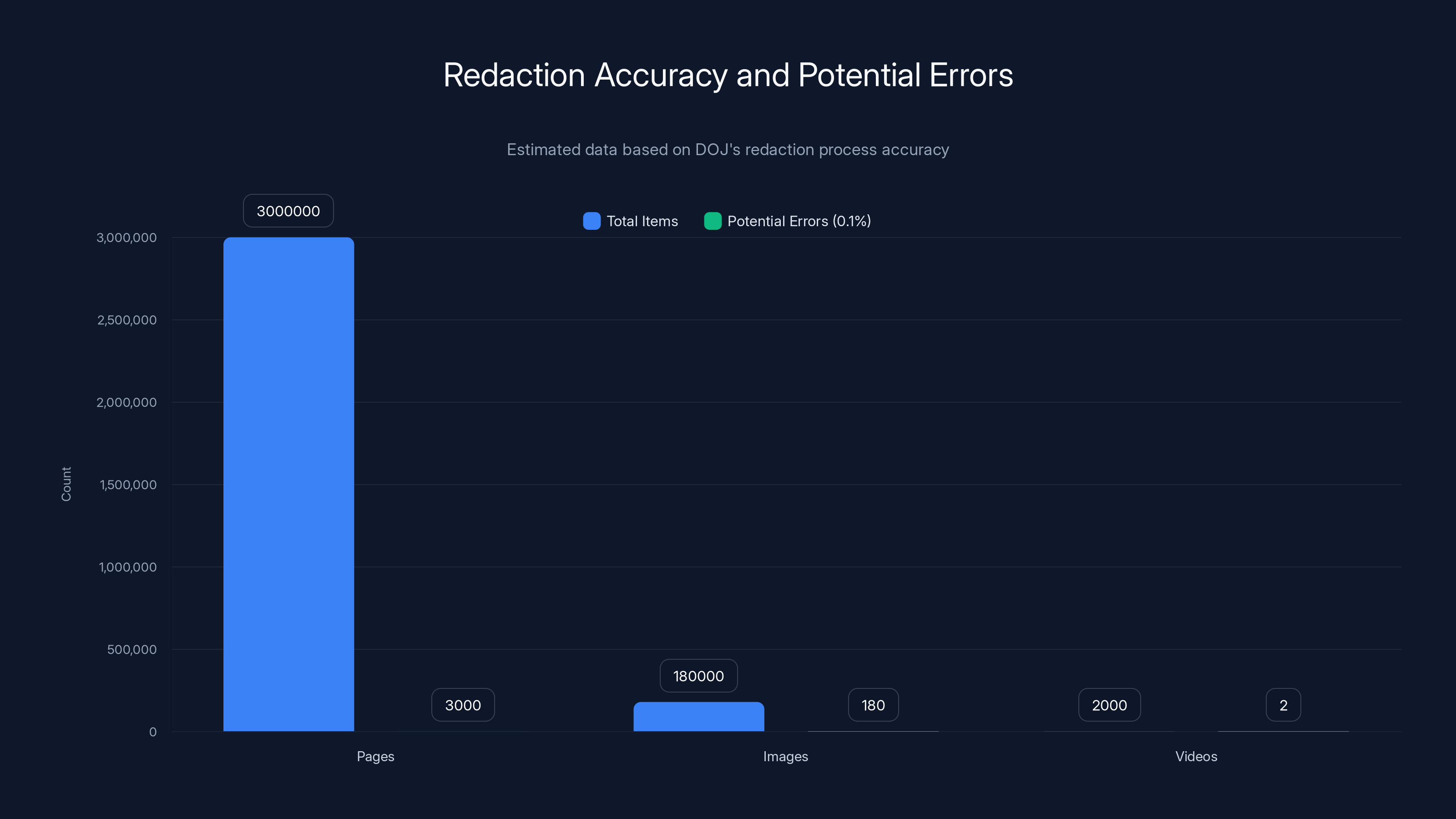

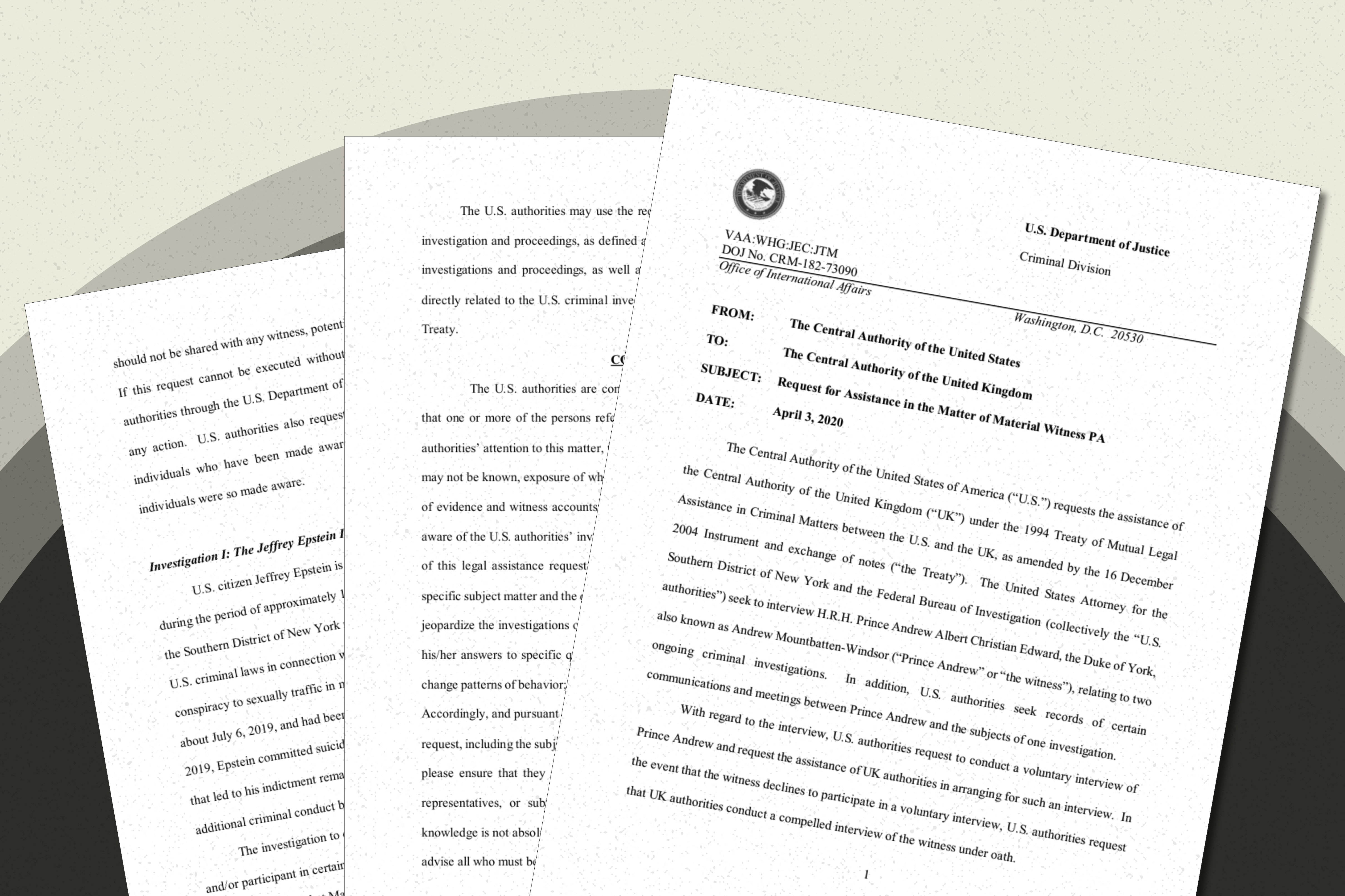

The release included more than 2,000 videos and 180,000 images collected from five separate cases and investigations. The scale was intentional. Congress had passed the Epstein Files Transparency Act, setting a December 19 deadline for the DOJ to make these files public. The goal was clear: let the public understand the scope of Epstein's crimes and the investigation's findings without further delays.

But the DOJ missed that deadline by over a month. And when the files finally went live on Friday, something catastrophic happened. Nearly 40 unredacted nude photographs remained visible. At least 43 victims' full names were left unredacted. Some of those names appeared more than 100 times throughout the documents. Worse, over two dozen of those names belonged to people who were minors when Epstein abused them, as reported by The New York Times.

This wasn't a small oversight. This was a systematic failure of one of the government's most critical responsibilities: protecting the privacy and safety of crime victims. And it raises uncomfortable questions about how the federal government handles sensitive information at scale.

Here's what actually happened, why it matters, and what this reveals about government transparency efforts.

How the Redaction Failed at Scale

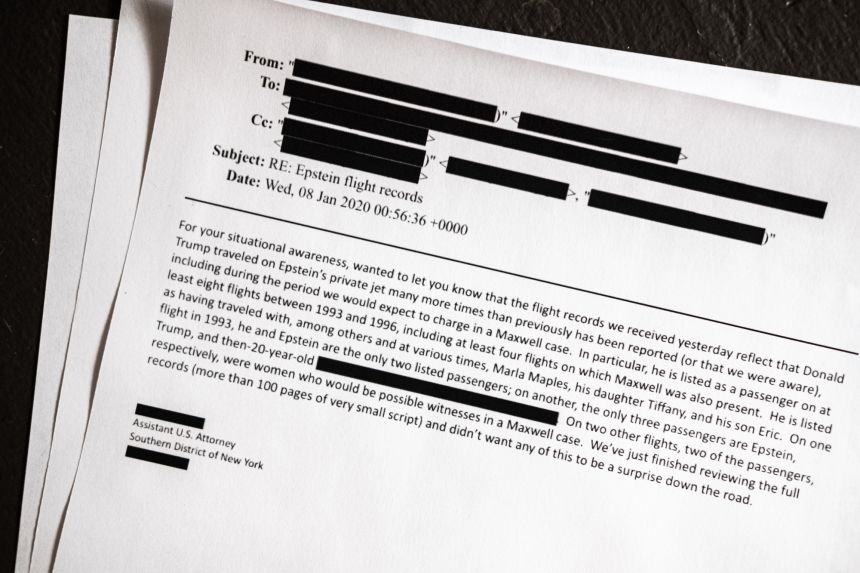

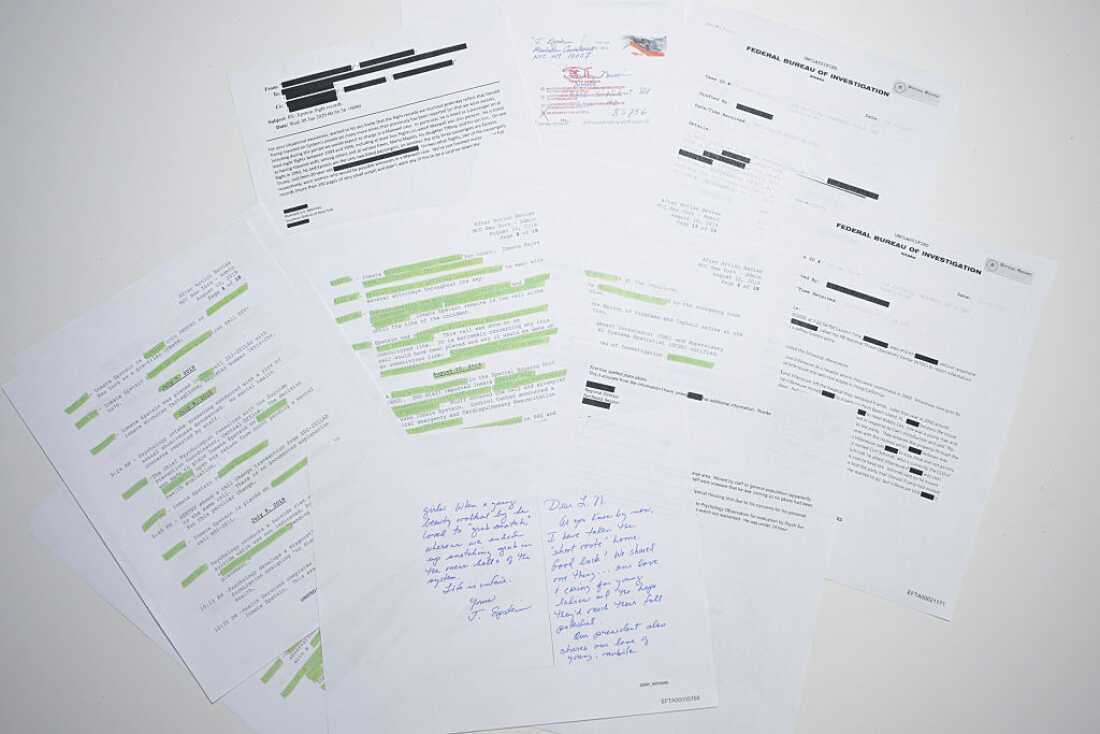

The scope of the Epstein files operation was genuinely massive. The DOJ described collecting materials from Florida cases, New York cases, Maxwell's prosecution, investigations into Epstein's death, even investigations into a former butler. These weren't neat, organized case files. They were five separate investigations' worth of evidence, witnesses statements, exhibits, photographs, and communications spanning decades.

The DOJ implemented what it called an "additional review protocol" before release. The agency wasn't just uploading raw files. They claimed to have developed a process specifically designed to identify and redact personally identifiable information about victims, nude images, and other sensitive content.

But here's where it broke down. When you're processing 3 million pages, 180,000 images, and 2,000 videos, even a 99.9% accuracy rate fails catastrophically. If your redaction process is 99.9% accurate, you're still missing potentially 3,000 errors across 3 million pages.

The types of failures tell the story. Some victims' names appeared consistently throughout documents but weren't flagged for redaction. Some nude images were missed entirely. The system didn't perform what should be a basic quality control check: a keyword search against a master list of victim names to verify that no full names remained visible.

Brad Edwards, an attorney representing Epstein victims, had actually provided the DOJ with a list of 350 victims on December 4, specifically so the government could use that list to verify redactions. As of the release, the government apparently hadn't performed that basic validation. Edwards told ABC News that the government should have at minimum run a keyword search against victim names before going live.

Instead, victims and their lawyers discovered the exposure organically. The New York Times found the unredacted photos. The Wall Street Journal discovered the unredacted names. 404 Media noticed that the nude images stayed online for at least a full day after the Times notified the government.

The DOJ's response was reactive, not proactive. They told media outlets they were "making additional redactions of personally identifiable information" and that "responsive documents will repopulate online" once proper redactions were complete. But that's not how this should work. The government shouldn't be finding out about privacy violations from newspaper investigations.

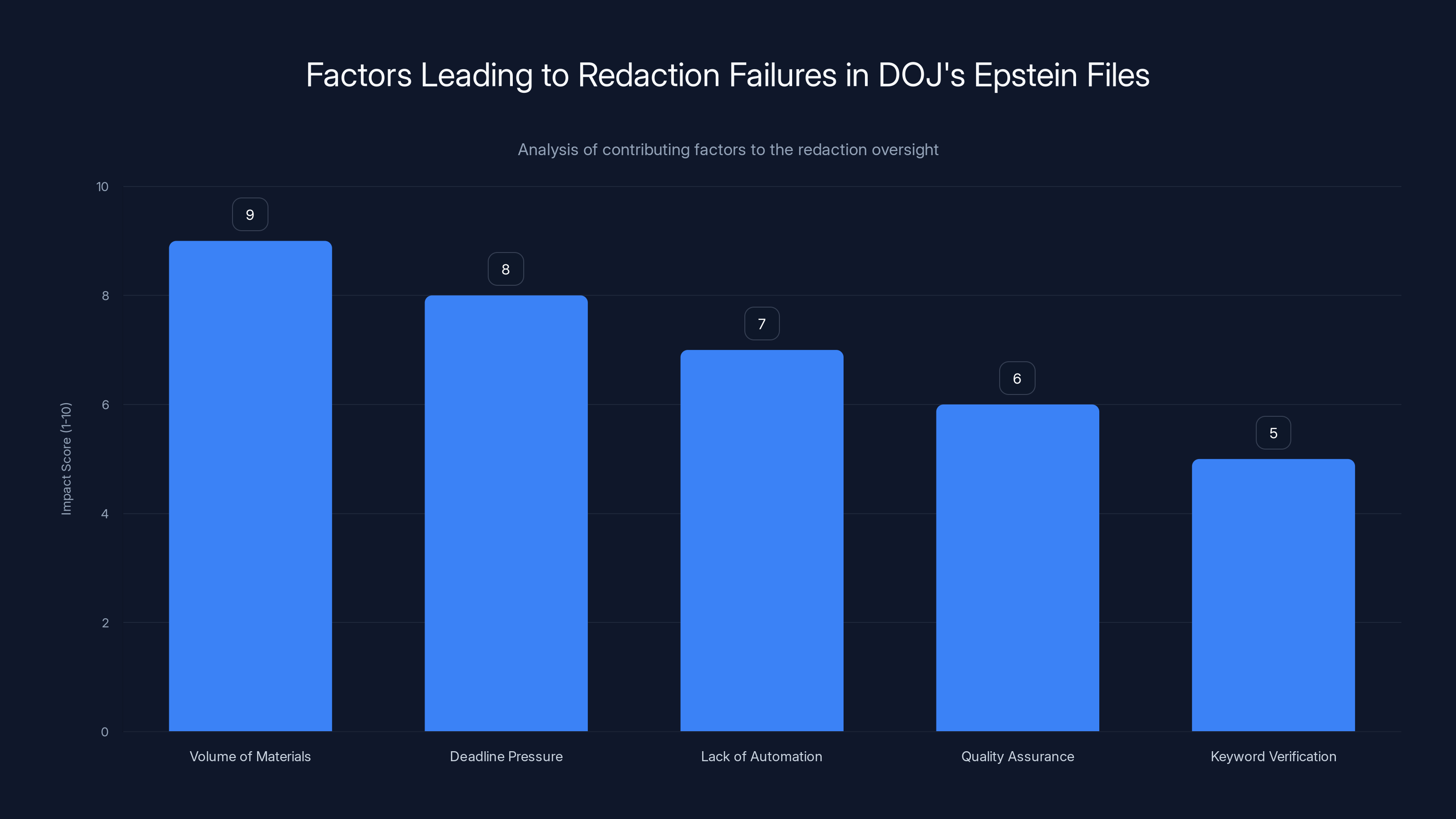

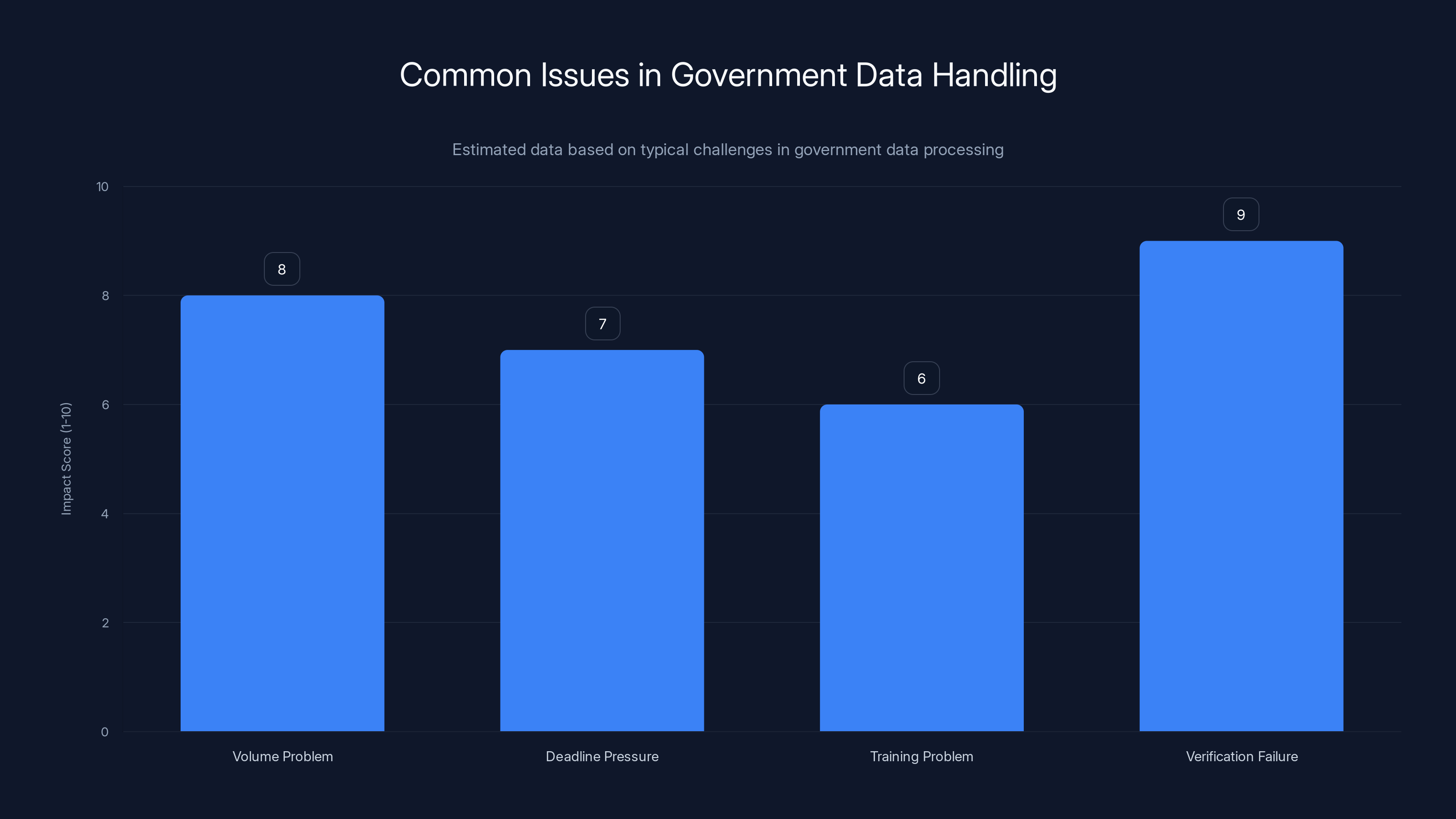

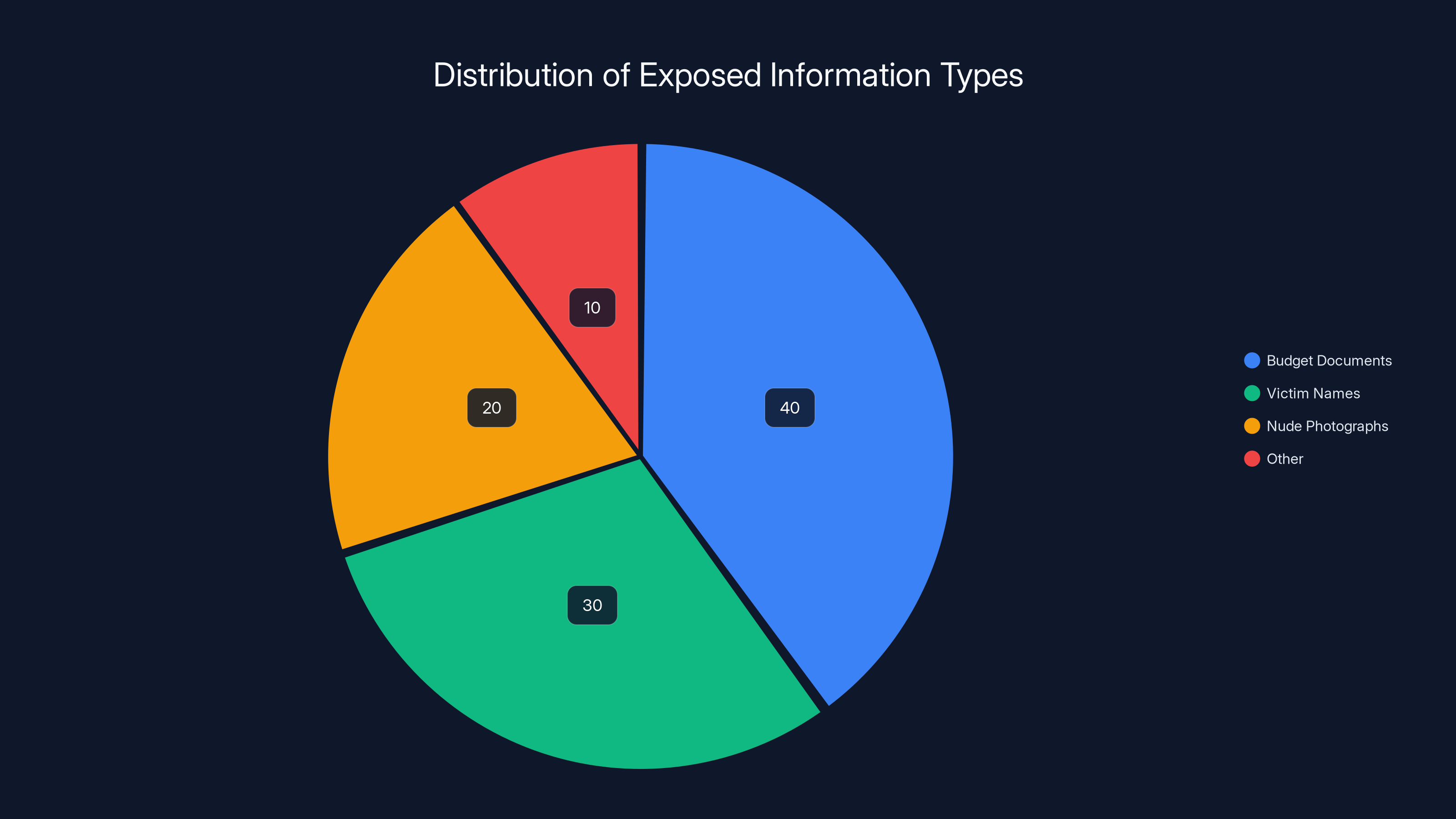

The massive volume of materials and deadline pressure were the most significant factors leading to redaction failures in the DOJ's Epstein files release. Estimated data.

The Impact on Victims: More Than Just Names

You have to understand what this exposure means for these individuals. Many of the victims whose information was released had never publicly identified themselves as Epstein victims. Their abuse had been private. Their recovery had been private. Now their full names were publicly searchable alongside descriptions of their abuse.

Anouska de Georgiou, who testified against Ghislaine Maxwell in her prosecution, learned her information was exposed when she discovered her driver's license picture was included unredacted in the files. Not just her name. Her address. Her image. A complete document that could enable someone to locate her.

Others faced the same situation. Victims who had kept their identity secret for years suddenly found themselves exposed to a potentially hostile public. The Wall Street Journal noted that many names appeared alongside "personally identifying details that make them readily traceable, including home addresses."

Annie Farmer, who testified that she was 16 years old when Epstein abused her in 1996, told The New York Times that the situation was "hard to imagine a more egregious way of not protecting victims than having full nude images of them available for the world to download."

Farmer is now a psychologist. She has built a life post-trauma. And suddenly, the federal government had made her vulnerable to retraumatization, harassment, privacy invasion, and potential physical danger. The same happened to dozens of others.

Brad Edwards reported that his office was receiving constant calls from victims who discovered their names and information were public. He described it as "literally thousands of mistakes," each one representing a specific person whose privacy was violated.

Even with a 99.9% accuracy rate, the redaction process could result in 3,000 errors across 3 million pages, highlighting the challenges of redaction at scale. Estimated data.

The Pattern: Government Data Failures and Why This Keeps Happening

This wasn't an isolated incident or the result of a single bad decision. This was a failure pattern that reflects larger problems in how government handles data.

First, there's the volume problem. When you're processing millions of pages, traditional manual review becomes impossible. You need automated systems to flag sensitive content. But automated systems make mistakes at scale. A 95% accurate system sounds good until you apply it to 3 million pages and realize that 5% error rate means 150,000 pages with problems.

Second, there's the deadline pressure. The Epstein Files Transparency Act set a hard December 19 deadline. The DOJ missed it by over a month. But even that one-month delay wasn't enough time to do the work properly. When institutions face time pressure and scope pressure simultaneously, something has to give. In this case, it was victim privacy.

Third, there's the training problem. The people implementing redaction protocols often don't fully understand the consequences of failures. A name in a document might seem like routine personally identifiable information from a standard redaction perspective. But that name attached to descriptions of sexual abuse is something else entirely. It requires different handling, different sensitivity, different verification.

Fourth, there's the verification failure. Nobody at the DOJ apparently said, "Before we release this, let's run a keyword search against all 350 victim names the lawyers gave us and make sure none of them appear unredacted." That's a basic quality control step that would have caught most of the problems. It wasn't done.

The DOJ's official statement acknowledged this indirectly. Their disclaimer on the Epstein files webpage said that "because of the volume of information involved, this website may nevertheless contain information that inadvertently includes non-public personally identifiable information or other sensitive content." In other words: we know we probably made mistakes, and we're admitting it upfront.

That's not reassurance. That's negligence with a disclaimer.

Why This Matters for Government Transparency

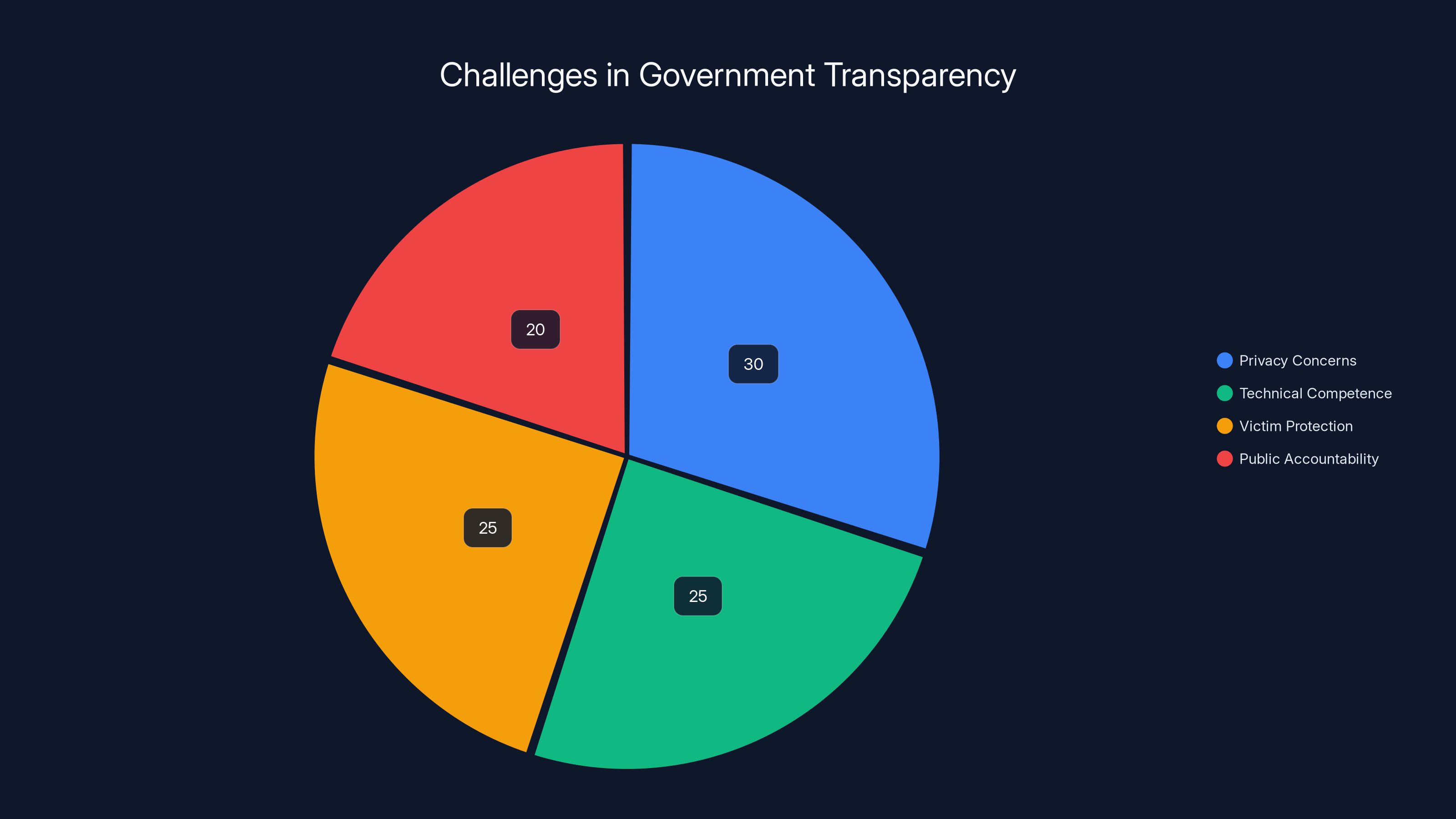

There's a tension at the heart of government transparency. The public has a right to understand what the government is doing. Transparency prevents corruption, reveals abuse of power, and ensures accountability. That's why the Epstein Files Transparency Act made sense. Epstein's crimes affected numerous people. The investigations were extensive. Understanding how government handled these cases has public value.

But transparency can't come at the cost of revictimizing victims. You can have both. You can release comprehensive case materials while protecting the privacy of the most vulnerable people involved. It just requires more care, more verification, and more time.

This failure will likely chill future transparency efforts. If victims know that demanding government transparency might result in their own exposure, they'll be less likely to cooperate with investigations. Prosecutors will face more resistance. And the government's ability to investigate serious crimes will suffer.

It also raises legitimate questions about whether government agencies have the technical competence to handle large-scale data releases securely. If the DOJ can't get this right, what does that say about other federal agencies handling sensitive data?

The irony is sharp: an effort to increase transparency resulted in decreased privacy for the people most entitled to protection. The tools and processes existed to prevent this. They just weren't implemented.

Verification failures and volume problems have the highest impact on government data handling issues. Estimated data based on common challenges.

The Technical Reality: Why Redaction at Scale is Harder Than It Looks

From a technical standpoint, redacting sensitive information from millions of pages sounds straightforward. Find the sensitive terms, remove them or obscure them, release the result.

In practice, it's exponentially more complex.

First, there's the identification problem. What counts as a victim's name? A full name is obvious. But what about partial names? Nicknames? Initials? In these documents, victims were referred to by first name only in some places and full names in others. The redaction protocol needs to be consistent across all these variations, or mistakes happen.

Second, there's the context problem. A victim's name appearing in a deposition has different sensitivity than the same name appearing in a list of witnesses. The same name appearing next to a nude image is more sensitive than appearing in a procedural document. Context matters, but automated systems often can't judge context well.

Third, there's the source problem. These files came from five different investigations. Each might have had different naming conventions, different formats, different organization schemes. Applying a consistent redaction protocol across all these sources is like trying to apply one set of rules to documents written in different eras, stored in different systems, organized according to different standards.

Fourth, there's the format problem. The DOJ wasn't just redacting text documents. They were redacting images, videos, and PDFs. Each format requires different technical approaches. A nude image requires visual analysis or manual review. A video requires either frame-by-frame analysis or extensive human review. Scaling that to 180,000 images and 2,000 videos is genuinely difficult.

The proper approach would have involved layered verification. First, automated systems to catch the obvious stuff. Second, human review of edge cases and complex situations. Third, keyword verification against a master list. Fourth, spot-checking by subject matter experts. Fifth, review by victim advocates or victim representatives.

The DOJ apparently did step one. Maybe step two. The failure to do steps three through five resulted in this disaster.

What the Numbers Actually Mean

Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche's comment that the exposed information represented "0.001 percent" of materials needs serious unpacking.

Technically, he might be right. If the exposed information represented 3,000 items out of 3 million pages, that's 0.1%, which rounds to the "0.001 percent" he mentioned. But that framing is deeply misleading.

First, it treats all data as equivalent. A misfiled budget document is not equivalent to an unredacted nude photograph of a victim. Yet both count as "materials." The fraction is mathematically defensible but substantively dishonest.

Second, it ignores the severity of the failures. Each exposed victim name might appear 100+ times in the files. Is that one error or 100 errors? The counting methodology matters.

Third, it ignores the irreversibility. Once a victim's name and address are public, you can't un-publish them. Screenshots have been taken. Archives have cached the pages. The information is everywhere. The government can redact it now, but that's closing the barn after the horses have escaped.

A more honest framing would be: "We failed to protect at least 43 specific individuals who had a reasonable expectation of privacy. Some of these individuals were minors when victimized. We don't know how long the information was publicly accessible before we noticed, and we don't know who accessed it or what they might do with it."

That's the actual situation. And it's unacceptable regardless of what percentage it represents.

Estimated data showing that privacy concerns and technical competence are major challenges in government transparency efforts, each accounting for about 25-30% of the issues.

The Institutional Accountability Question

When something this serious goes wrong, accountability usually follows. But what does accountability look like for government agencies, and is it sufficient?

The DOJ established an email address for victims to report unredacted materials. That's reactive. They acknowledged making "additional redactions" and said materials would be corrected. That's also reactive. But nobody has faced consequences for the initial failure.

Brad Edwards called for the government to take the entire release down temporarily, properly complete the redaction process, and then rerelease it. That would actually protect victims. It would also temporarily delay the transparency that the law requires. But protecting specific, identifiable vulnerable people should take priority over general transparency goals.

The government hasn't done that. Instead, they're redacting material as problems are reported, which means victims are continuing to report their own exposure—essentially asking the government to fix its mistake after the fact. That puts the burden on victims to discover they've been exposed and then advocate for their own privacy.

There are several structural failures that enabled this:

Lack of victim representation in the process: The DOJ didn't involve victim advocates in the redaction process. They received a list from Edwards but apparently didn't treat it as a critical verification tool.

Absence of pre-release verification: No one apparently said, "Before this goes live, let's verify that our keyword search for [list of 350 names] returns zero results for unredacted mentions."

Weak quality assurance: The processes were there, but the execution was half-hearted. An "additional review protocol" isn't enough. You need multiple verification layers.

Deadline pressure overriding process: The missed December 19 deadline meant the government was probably rushing. But rushing wasn't justified. Better to miss a deadline by another month than to expose victims.

None of these failures required technical incompetence. They required organizational failures: unclear priorities, inadequate process, insufficient verification, and pressure to move fast rather than move right.

Lessons for Government Data Management

This incident provides several critical lessons for how government agencies should handle large-scale data releases involving sensitive information.

Lesson 1: Scale doesn't justify carelessness. Yes, 3 million pages is a lot. But that's precisely why you need better processes, not worse ones. The bigger the project, the more critical the quality assurance.

Lesson 2: Automated redaction needs human verification. Automated systems are useful for handling volume. But they need oversight. Someone should verify that the automated systems actually worked before releasing materials.

Lesson 3: Involve affected communities. The DOJ had a list of 350 victims from their own lawyers. That list should have been a critical input to the verification process, not a nice-to-have.

Lesson 4: Deadline pressure isn't an excuse. If you can't do something right in the given timeframe, you need to ask for more time. The Epstein Files Transparency Act probably allows for flexibility in exactly these situations.

Lesson 5: Prerelease disclosure and spot-checking matter. Before going live, show your final output to relevant stakeholders—victim advocates, relevant prosecutors, subject matter experts—and ask them to spot-check it.

Lesson 6: Speed of response matters for mitigation. The DOJ was relatively quick to remove materials once they were notified. But faster notification detection mechanisms would have been better. Real-time monitoring of the release could have caught problems immediately.

These aren't technical lessons. They're organizational and prioritization lessons. The government has the technical capability to do this correctly. It chose not to.

Estimated data showing that while budget documents may form the largest category, sensitive information like victim names and nude photographs represent a significant portion of the exposed materials.

Comparing to Private Sector Data Incidents

When major tech companies experience data breaches or privacy failures, they face lawsuits, regulatory fines, and reputational damage. When the government does it, the accountability is usually softer.

Consider what happened when Microsoft had security vulnerabilities, or when Facebook exposed user data. Those incidents resulted in tens of millions in fines, regulatory investigations, and organizational restructuring.

The DOJ's failure to properly redact victim information in a massive data release seems at least as serious. Yet the response has been administrative, not investigative. No one has been fired. No one has faced consequences. No fine or penalty has been imposed.

There's an asymmetry here that's worth noting. Private companies face strong incentives to protect user data because failures carry real costs. Government agencies face weaker incentives because accountability mechanisms are less direct. Worse, government agencies often have fewer resources and less sophisticated data infrastructure than major tech companies.

Some of this is unavoidable. The government is managing legacy systems and budgets that don't match the complexity of modern data. But some of it reflects choices. The DOJ could have invested more in verification infrastructure. They could have delayed the release to do it properly. They could have implemented the lessons from previous data incidents.

The good news is that future incidents are preventable. The bad news is that this one wasn't difficult to prevent, and it happened anyway.

The Broader Implications for Privacy Law and Government Transparency

This incident occurs at a moment when privacy law is being reconsidered at multiple levels of government. California, New York, and other states have privacy legislation on the books or in development. The federal government is debating privacy frameworks.

The Epstein Files Transparency Act itself reflects a recognition that government transparency serves important public interests. But this incident suggests that transparency and privacy aren't always in harmony, and when they conflict, vulnerable people often lose.

There are legitimate questions about whether victims of crimes should have to maintain privacy from each other and from the public. Some privacy advocates argue that victims should have the right to control their own narrative and choose whether to publicly identify themselves. Others argue that public knowledge of how crimes were investigated serves broader social interests.

But there's no reasonable debate about whether unredacted nude images of victims should be publicly available. There's no legitimate reason why victims' home addresses should be searchable in government documents. The failures here aren't in the conceptual framework. They're in execution.

The lesson for privacy law is that transparency frameworks need to include specific protections for vulnerable populations. The Epstein Files Transparency Act set a deadline and specified what should be released. But it apparently didn't provide sufficient guidance or resources to ensure that sensitive information was properly protected.

Future transparency legislation should include:

- Specific protections for victim information

- Requirements for victim notification before release

- Provisions for delaying release if proper protections can't be implemented

- Clear accountability mechanisms for failures

- Requirements for victim representation in verification processes

Without these, transparency efforts will continue to harm the very people they're intended to protect.

Recommendations for Victims and Advocates

If you're affected by this or similar incidents, there are some practical steps worth considering.

The DOJ has established an email address (EFTA@usdoj.gov) for reporting improperly redacted materials. Victims should use this. Document what was exposed, when you discovered it, and what actions you took. Keep records.

Consider contacting a privacy attorney who works with victims. The government's failures might create legal liability that you should understand.

Document the exposure. Take screenshots if the materials are still available (they might not be for long as the DOJ redacts them). Time-stamp your documentation. This creates evidence of the exposure in case you need it later.

Consider whether you want to join any class action or collective response. Victims' advocates and attorneys are likely coordinating responses. Strength often comes from collective action.

Most importantly, understand that this is not your fault. The government had clear responsibility to protect your information, and they failed. You're not responsible for discovering their failures or fixing them. That's on them.

The Path Forward: Rebuilding Trust

The DOJ will probably eventually fully redact all improperly exposed information. Materials will come down and go back up with corrections. Eventually, the release will stabilize in its properly redacted form.

But the damage to trust is harder to repair. Victims now know that government agencies can fail to protect their information, even when explicit legal provisions require protection. That creates a chilling effect. Why cooperate with government investigations if there's a risk you'll be exposed?

Prospective victims might hesitate to report crimes. Witnesses might decline to participate in cases. The practical ability of law enforcement to investigate crimes could be reduced.

The government could rebuild trust through several mechanisms:

First, accountability. Someone should face consequences for these failures. That could be personnel changes, process audits, or other measures. But there should be visible accountability.

Second, comprehensive remediation. Beyond redacting materials, the DOJ should offer support to affected victims. This might include notification of exposure, identity theft monitoring, counseling, or other resources.

Third, structural change. The processes that enabled this failure should be changed. Future releases should include the verification mechanisms that prevented this incident.

Fourth, transparency about the failure. The DOJ should be honest about what happened, why it happened, and what they're doing differently. That honesty itself can rebuild trust.

Without these measures, the incident will be remembered as an example of how government agencies fail the people most entitled to protection. With these measures, it could become a turning point—a moment when institutions committed to doing better.

The choice is up to the DOJ.

FAQ

What exactly was exposed in the DOJ's Epstein files release?

The DOJ released over 3 million pages of files related to Jeffrey Epstein investigations, including documents, emails, photos, videos, and other materials. In the process, nearly 40 unredacted nude photographs and at least 43 victims' full names remained visible to the public. Some victims' names appeared 100+ times in the files, often alongside personally identifying information like home addresses.

Why did the government fail to properly redact the information?

The failure resulted from multiple factors: the massive volume of materials (3 million pages, 180,000 images, 2,000 videos), deadline pressure from Congress, lack of adequate automated redaction systems for such volume, absence of proper quality assurance verification, and failure to use a master list of victim names for keyword-search verification before release. Essentially, the government prioritized speed over security.

How did victims discover their information was exposed?

Victims didn't discover the exposure themselves. Journalists at The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal found the unredacted information while reviewing the released files. They contacted the DOJ and reported the exposure. Additionally, 404 Media discovered that nude images remained online for at least a full day after the Times notified the government. This means victims were only notified after media outlets reported the problem, not because the government proactively checked the release.

What are the legal implications of this exposure?

The government may face liability for violating victims' privacy rights, failing to comply with the intent of the Epstein Files Transparency Act (which required proper redaction), and potentially violating federal privacy laws. Victims may have grounds for lawsuits against the DOJ for damages. Additionally, victims who were minors when abused may have additional legal protections under laws regulating the distribution of images involving minors, though the legal analysis here is complex since the images were released by the government unintentionally.

How can victims report the exposure or request removal?

The DOJ established an email address, EFTA@usdoj.gov, where victims and their representatives can report improperly redacted materials. Upon notification, the DOJ commits to removing or redacting the materials. Victims should document what was exposed, when they discovered it, and provide specific page numbers or file references. Keeping documentation of the exposure is important for any potential legal claims.

What changes should the government make to prevent this from happening again?

Future releases should include: (1) mandatory pre-release verification using keyword searches against known protected names, (2) human spot-checking before materials go live, (3) involvement of victim advocates in the verification process, (4) stronger quality assurance protocols across all formats, (5) willingness to delay release rather than rush with inadequate redaction, and (6) post-release monitoring systems to catch errors quickly. Essentially, privacy and victim protection should be prioritized over meeting arbitrary deadlines.

Did the DOJ face any penalties for this failure?

As of the incident's disclosure, no formal penalties, investigations, or personnel consequences were announced. The DOJ's response was administrative: they established an email for reports and committed to making additional redactions. Whether future investigations or consequences emerge remains to be seen. Compared to penalties faced by private companies for similar data exposure incidents, the government's accountability mechanisms appear weaker.

What percentage of the release contained improperly exposed information?

Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche claimed the exposure represented approximately 0.001% of all materials. However, this framing is misleading because it treats all data equally, ignoring that some errors (unredacted nude images, victim addresses) are far more serious than others. A more meaningful metric is that 43 specific identifiable individuals had their privacy violated, some multiple times across documents, with their sensitive information and contact details exposed.

Can victims sue the government for damages?

Victims likely have grounds for civil lawsuits under privacy statutes and potentially under constitutional privacy rights. However, suing the federal government involves complex legal procedures, including potentially exhausting administrative remedies first and dealing with government immunity doctrines. Victims should consult with attorneys experienced in privacy law and victims' rights to understand their specific options. Class action litigation might also be an option if multiple victims coordinate.

How does this incident affect the credibility of government transparency efforts?

This incident creates a chilling effect on victims' willingness to cooperate with government investigations, knowing their information might be exposed later. It also raises questions about whether government agencies have the technical and organizational capacity to handle large-scale data releases safely. Future transparency efforts might face resistance from victims' advocates and from prospective victims hesitant to participate in official processes. The incident demonstrates that transparency and victim protection must be equally prioritized, not treated as competing goals.

Key Takeaways

The DOJ's Epstein files release exposed critical failures in how government handles sensitive victim information at scale. Nearly 40 nude photographs and 43 victims' full names were left unredacted despite explicit legal requirements for protection. The failures resulted from inadequate quality assurance, absence of verification processes, and deadline pressure overriding proper security protocols. Journalists discovered the exposure before the government did, revealing the lack of proactive monitoring. Victims faced retraumatization, privacy invasion, and safety risks. The incident has broader implications for government transparency law, privacy protection, and victim trust in institutions. Future releases require stronger structural safeguards, victim involvement in verification, and willingness to delay timelines when proper protection can't be ensured.

Related Articles

- How to Film ICE & CBP Agents Legally and Safely [2025]

- Big Tech's $7.8B Fine Problem: How Much They Actually Care [2025]

- Google's $68M Voice Assistant Privacy Settlement [2025]

- Why ICE Masking Remains Legal Despite Public Outcry [2025]

- ICE Judicial Warrants: Federal Judge Rules Home Raids Need Court Approval [2025]

- ICE Agents Doxing Themselves on LinkedIn: Privacy Crisis [2025]

![DOJ Epstein Files Redaction Failure: What Happened and Why It Matters [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/doj-epstein-files-redaction-failure-what-happened-and-why-it/image-1-1770059210325.jpg)