Dr. Gladys West: The Hidden Mathematician Behind GPS

You use GPS every single day. Whether you're navigating to a restaurant, tracking a delivery, or relying on emergency services to find your location in a crisis, you're benefiting from work that started in the 1970s inside a naval facility in Virginia. But most people have no idea who made it possible.

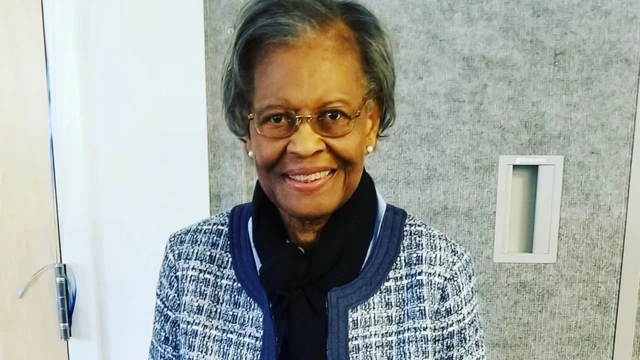

Dr. Gladys West was one of the most influential mathematicians of the 20th century, yet her name remained virtually unknown until 2018. She passed away on February 13, 2024, at 95 years old, leaving behind a legacy that touches billions of lives daily. Her story isn't just about mathematics or technology. It's about resilience, intellectual brilliance, and the systemic erasure of Black women's contributions to science.

West's work created the mathematical foundation that transformed GPS from a theoretical concept into the practical technology that powers modern life. The satellites circling Earth, the navigation systems in your car, the apps on your phone that pinpoint your exact location within meters, the systems that coordinate air traffic and guide emergency responders—all of these trace their lineage back to her equations.

What makes her story even more remarkable is the context. She accomplished this groundbreaking work during the height of segregation, at a time when Black women faced systematic exclusion from STEM fields. She navigated institutional racism, gender discrimination, and the widespread assumption that women couldn't contribute meaningfully to complex mathematics. Yet she not only survived these barriers—she thrived, publishing research that became fundamental to one of humanity's most transformative technologies.

This article explores West's extraordinary life, her mathematical contributions to GPS, the systemic obstacles she overcame, and why her story matters for understanding both the history of technology and the future of diversity in science.

TL; DR

- Pioneer's breakthrough: Dr. Gladys West developed accurate mathematical models of Earth's shape using satellite data in the 1970s-1980s, directly enabling modern GPS technology

- Decades of invisibility: Despite working at the Naval Surface Warfare Center for 42 years, West's contributions remained largely unrecognized until 2018

- Overcoming systemic barriers: She pursued higher education and built a distinguished career despite Jim Crow segregation and gender discrimination in STEM

- Late recognition: West was inducted into the Air Force Space and Missiles Pioneers Hall of Fame and honored as Female Alumna of the Year by the HBCU Awards in 2018

- GPS impact: Her geodetic models form the mathematical backbone of GPS systems now used in aviation, emergency response, mapping, and navigation globally

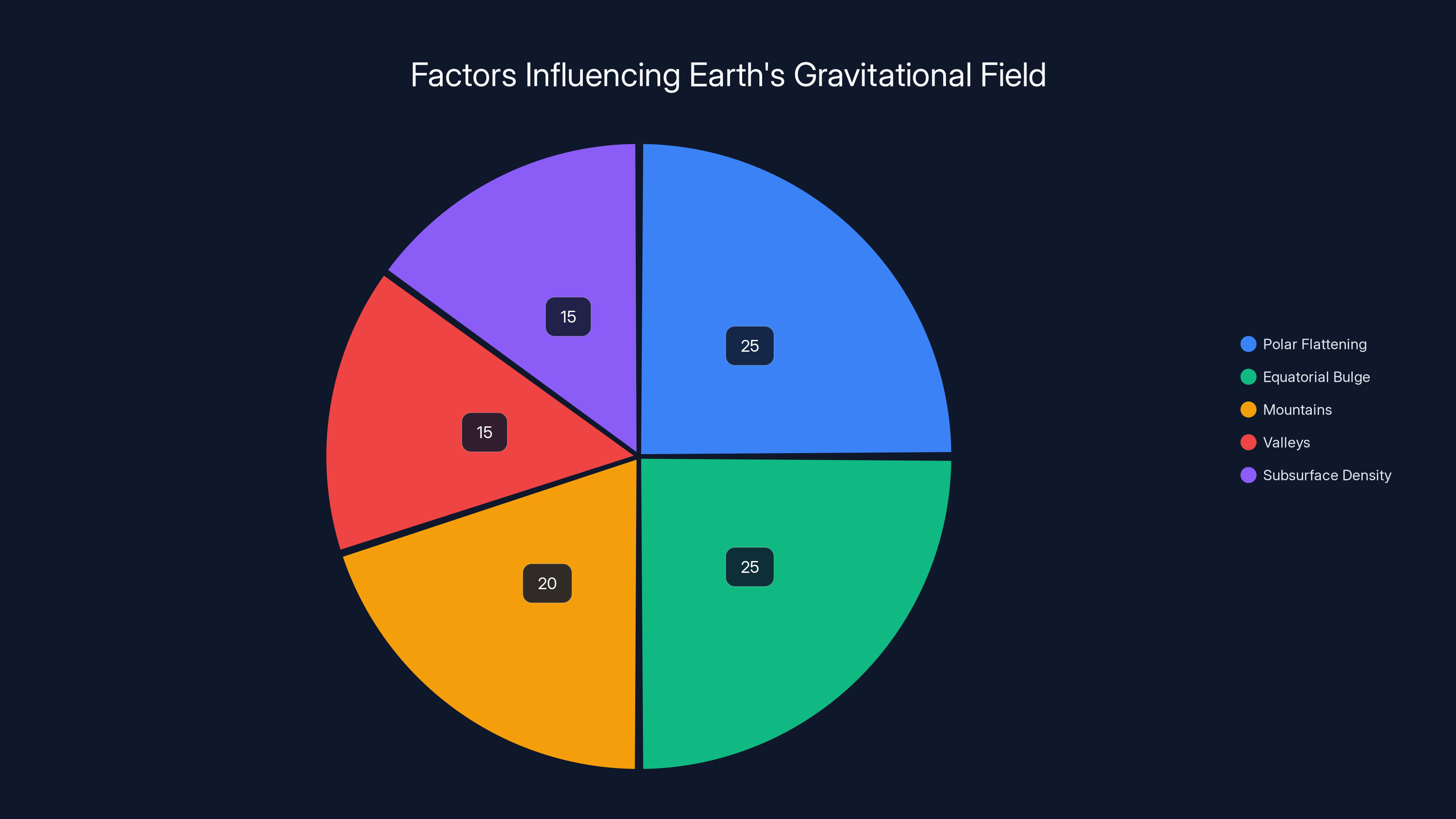

Estimated data showing the distribution of factors affecting Earth's gravitational field. Polar flattening and equatorial bulge are major contributors.

Early Life: A Mathematician in the Age of Segregation

Born Into Barriers

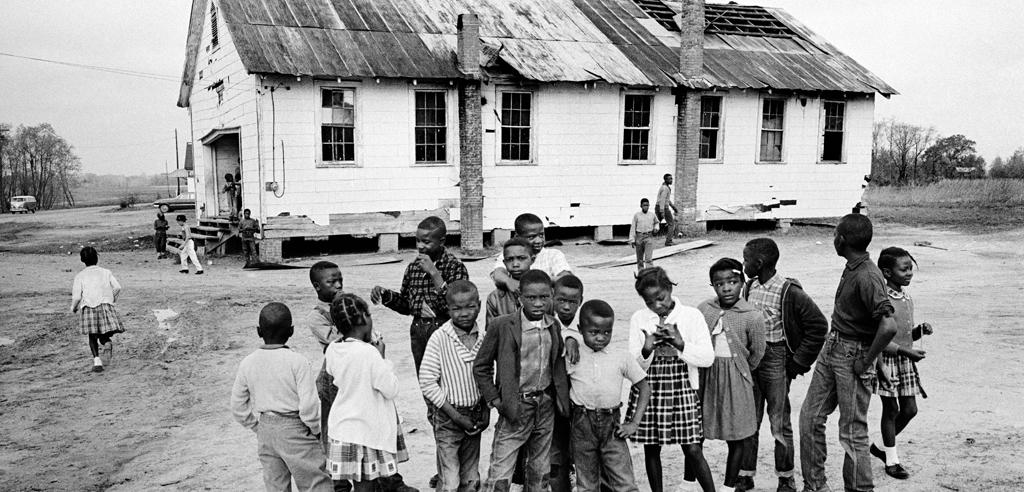

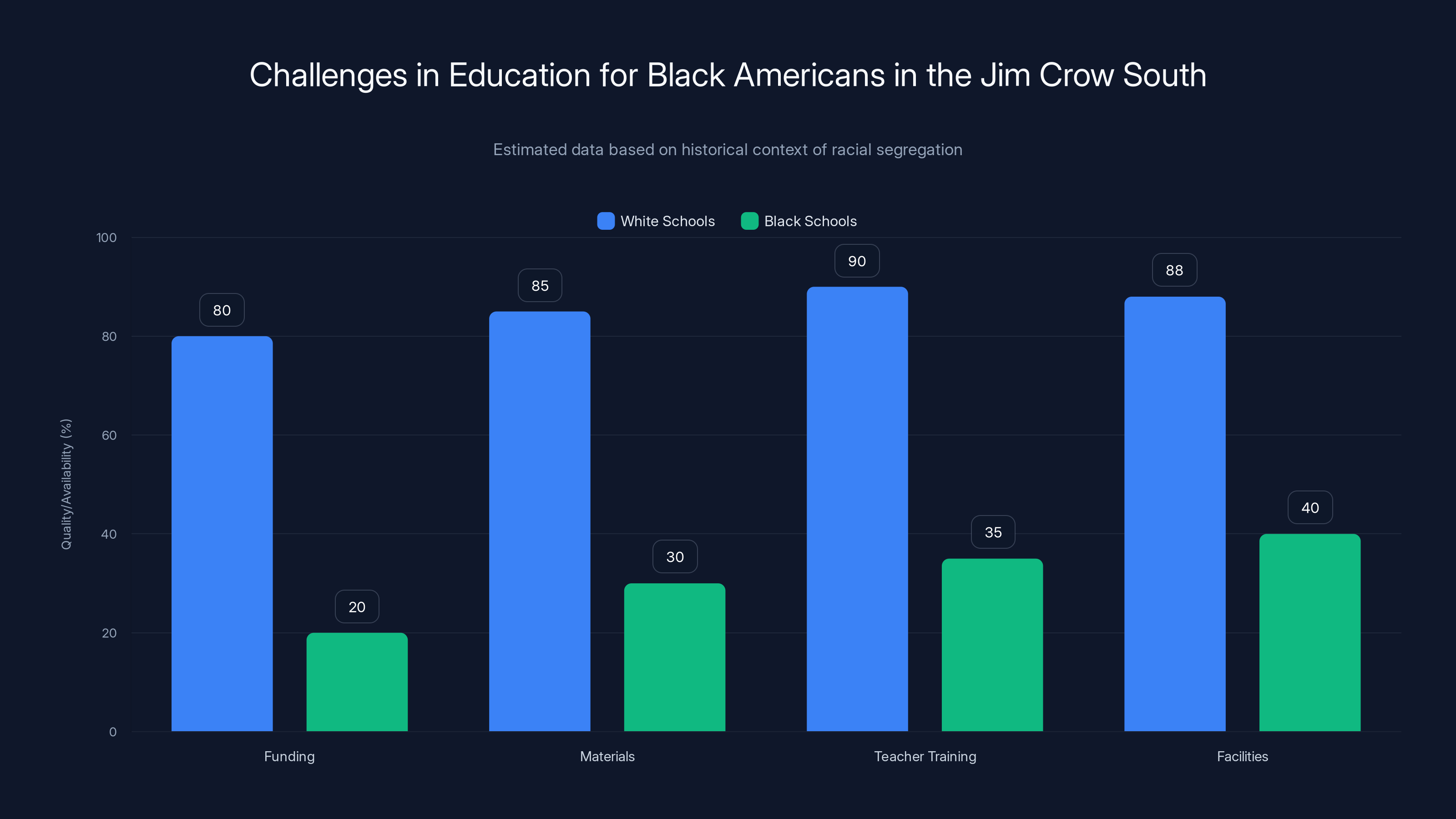

Gladys Beverly West entered the world on December 27, 1930, in Sutherland, Virginia—a time when the nation's legal infrastructure enshrined racial segregation and, by extension, limited educational pathways for Black Americans, particularly Black women. The Jim Crow South she grew up in was designed to systematically restrict Black people's access to quality schools, universities, and professional opportunities. Most Black communities in the South operated with severely underfunded schools, outdated materials, and teachers who themselves were often denied proper training and resources.

Yet West's family prioritized education despite these constraints. Her father worked as a farmer, and her mother was a schoolteacher. This combination proved invaluable. Her mother recognized early that Gladys possessed an exceptional mind for mathematics and encouraged her to pursue learning with intensity. In an era when many young Black girls were steered toward domestic work or caregiving roles, West's household sent a different message: your mind is your power.

Growing up in rural Virginia during the Depression and World War II era, West witnessed the stark inequalities of segregated America firsthand. The facilities available to Black students were primitive compared to white schools. Books were hand-me-downs. Laboratories lacked proper equipment. Yet within these constraints, West developed a fierce intellectual curiosity about how the world worked—particularly mathematics, the language that described natural phenomena.

Higher Education Against the Odds

West enrolled at Virginia State College (now Virginia State University) in the late 1940s. This historically Black college and university (HBCU) was one of the few pathways available to Black students seeking higher education in the segregated South. The college had been established specifically to serve Black students excluded from predominantly white universities, representing both a segregationist policy and a crucial institution for Black intellectual development.

At Virginia State, West excelled in mathematics. She earned her bachelor's degree in mathematics in 1952, followed by a master's degree in 1953—both achievements that placed her in a remarkably small cohort of Black women with advanced mathematics training in the early 1950s. During this same period, most of America's major universities excluded Black students entirely. The integration of higher education still lay more than a decade in the future.

What's particularly striking is that West achieved these credentials in mathematics—a field that even today struggles with diversity and inclusion. In the 1950s, the exclusion was far more severe. Black women mathematicians were virtually non-existent in American academia. The assumption held by most white academics and institutions was that Black people, and especially Black women, lacked the intellectual capacity for advanced mathematics. This wasn't a matter of opinion—it was actively reinforced through exclusion, underfunding of Black schools, and professional networks that never included Black scholars.

Yet West persisted. She didn't just complete her degrees—she demonstrated mastery of complex mathematical concepts. Her work at Virginia State showed she was capable of rigorous, original thinking in advanced mathematics. But like most Black graduates of that era, the doors that opened for white counterparts remained closed to her.

The Path to Naval Service

After completing her master's degree in 1953, West faced a job market that was explicitly segregated. Most employers didn't hire Black workers, and those that did confined them to menial positions. Scientific and technical fields were almost entirely white. Universities that might hire mathematicians were virtually all-white institutions with explicit or implicit racial restrictions.

The federal government, particularly the military, offered different opportunities. While the U. S. military remained segregated throughout the 1950s, certain technical positions—particularly in research and computation—began opening to Black workers. In 1956, West was hired at what was then called the Naval Ordnance Laboratory at Dahlgren, Virginia (later renamed the Naval Surface Warfare Center). This facility conducted advanced research in naval weapons systems and related technologies.

This position changed everything. Unlike many corporate employers, the federal government had been required to examine its hiring practices, and by the mid-1950s, some technical roles were open to qualified applicants regardless of race. West's exceptional credentials—a master's degree in mathematics from an established institution—made her qualified for positions that most Black workers couldn't access.

What's important to understand is that West's hiring wasn't a moment of corporate enlightenment. It reflected cold, practical necessity. The space race was beginning. Advanced computation was becoming critical to national security. The government needed mathematicians, and the pool of available American mathematicians was limited. Racial discrimination was not abandoned for moral reasons—it was subordinated to technological urgency.

Still, West seized the opportunity. She didn't simply take a job; she entered an intellectual environment where she could deploy her mathematical talents on problems of genuine complexity and importance.

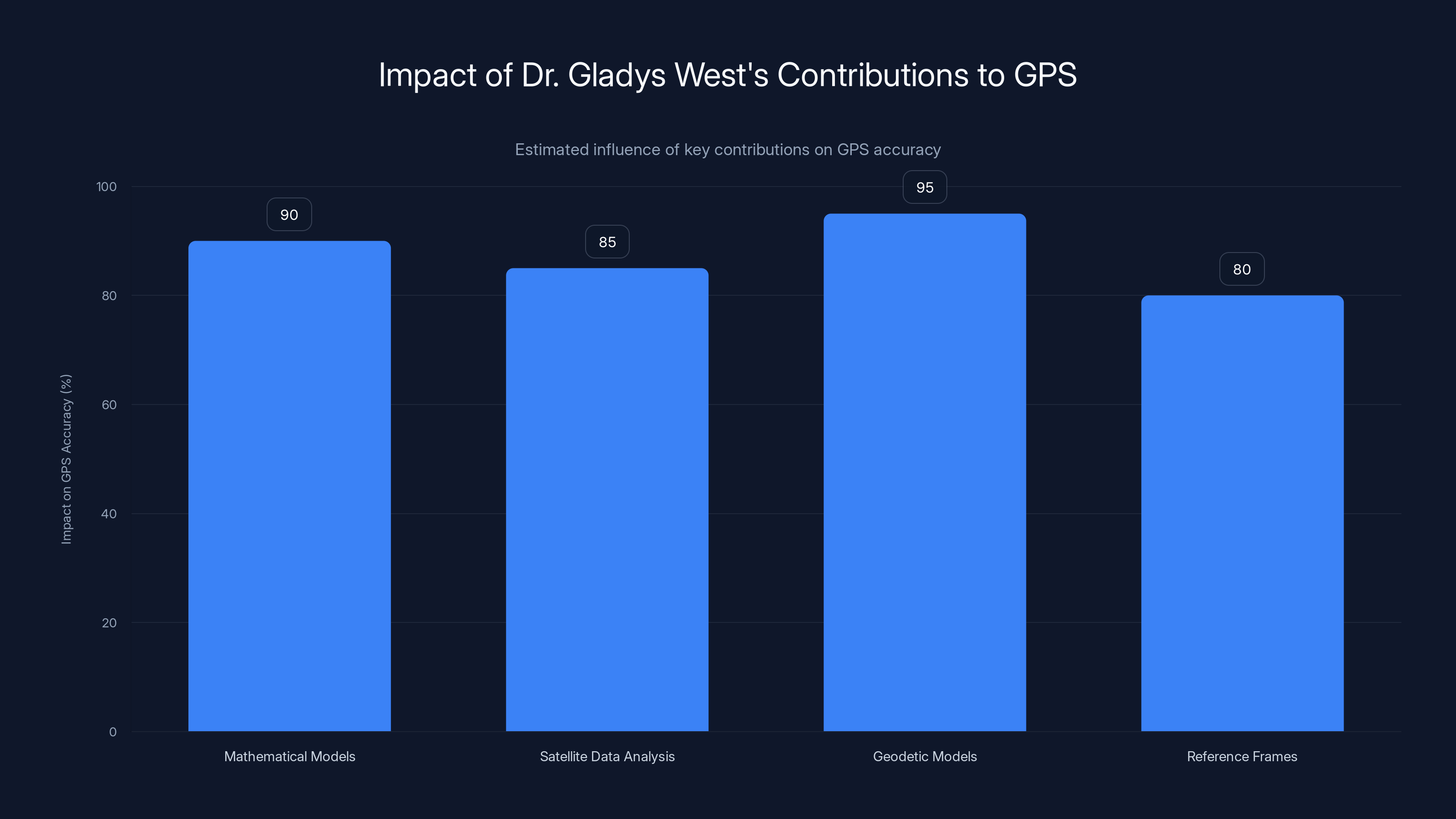

Dr. Gladys West's mathematical models and geodetic work significantly enhanced GPS accuracy, with estimated impacts ranging from 80% to 95%.

The Era of Computation: Women Mathematicians and Early Computing

Women in the Mathematical Sciences

When Gladys West joined the Naval Ordnance Laboratory in 1956, the landscape of mathematical work in America was undergoing dramatic transformation. Computers were emerging from experimental status into practical tools. The earliest computers—machines like ENIAC and the IBM Mark I—required armies of human computers to verify calculations, write code, and interpret results.

Interestingly, much of the early computational workforce was female. Women mathematicians and scientists took positions as "computers"—people who performed mathematical calculations by hand and later by early electronic computers. This wasn't due to progressive hiring policies. Rather, it reflected a familiar dynamic: women were hired for work that was tedious, required precision, and was considered less prestigious than theoretical mathematics. The early computer industry literally built itself on the labor of women who were systematically underpaid and undervalued.

West entered this world with advanced credentials, which meant she moved beyond basic computation into more complex mathematical work. Yet even within this female-dominated computing workforce, Black women were rare. While white women faced sexism and were confined to certain roles and lower pay grades, Black women faced both racism and sexism—a compounding discrimination that further restricted their opportunities.

What's remarkable about West is that she didn't remain in computational support roles. She moved into research and mathematical modeling, becoming one of a tiny number of Black women working in advanced mathematics during the 1950s and 1960s.

The Computational Revolution

During the 1960s and 1970s, the computational landscape transformed again. Computers became faster, more powerful, and more accessible. Where early computation had been a matter of breaking complex problems into simple arithmetic operations performed by human computers, now those operations could be handled by machines at unprecedented scale and speed.

This opened possibilities for mathematical work that had been impractical before. Complex systems could be modeled. Large datasets could be processed. Equations that would take human mathematicians weeks to solve could be computed in hours.

West's work at Dahlgren increasingly involved using these advancing computational tools to tackle problems of satellite geodesy—understanding Earth's shape and gravitational field based on satellite data. This required sophisticated mathematics, advanced computing, and the ability to navigate uncertainty in novel ways.

What's often overlooked in narratives about the computer revolution is that the work of translating human mathematical insight into computations that machines could execute required tremendous mathematical sophistication. You had to understand both the abstract mathematics and the practical constraints of the machines executing them. West excelled at this translation.

The Mathematical Foundation of GPS: West's Core Contribution

Understanding Earth's True Shape

GPS depends on knowing precisely where satellites are located in orbit. This seems straightforward until you consider the problem in detail: to use satellites to determine your position on Earth's surface, the system must know the satellites' positions with extraordinary precision. An error of a few meters in understanding satellite position translates into proportionally larger errors in ground-based positioning.

But here's the deeper challenge: to know where satellites are, you must first understand Earth's gravitational field. Earth isn't a perfect sphere. It's slightly flattened at the poles, bulges at the equator, has mountains, valleys, and dense rock formations below the surface. Each of these variations slightly distorts gravity.

Satellites don't follow perfectly circular orbits. Their paths are subtly influenced by gravitational variations across Earth's surface. To predict where a satellite will be at any given moment, you need a precise mathematical model of Earth's shape and gravitational field.

This was the problem West tackled beginning in the 1970s. Using satellite data that had been collected throughout the 1960s, she constructed increasingly accurate mathematical models of Earth's shape. She wasn't just fitting data to an equation. She was engaging in what's called geodesy—the mathematical science of measuring and representing Earth's size, shape, and gravity field.

The mathematics involved was genuinely sophisticated. West was working with satellite data that contained noise and measurement errors. She had to develop statistical methods to filter out errors while preserving true signal. She had to construct three-dimensional models from two-dimensional observations. She had to account for relativistic effects—Einstein's relativity, which affects how time passes for objects moving at different speeds and in different gravitational fields.

By the 1980s, West's mathematical models of Earth were among the most accurate in existence. These models became the foundation for GPS accuracy. When the military GPS system was developed, when civilian GPS was later released for public use, these systems depended on West's geodetic work to maintain accuracy over time.

The Technical Mathematics Behind GPS

To understand what West accomplished, it helps to grasp the basic mathematics of GPS systems. A GPS receiver determines its position by measuring signals from multiple satellites. Each satellite transmits a signal that includes the satellite's location and the time the signal was transmitted. By comparing the signal's transmission time to the receiver's local time, the receiver calculates the distance to each satellite (since radio signals travel at the speed of light, distance = speed of light × time elapsed).

With distance measurements to at least four satellites, a receiver can calculate its three-dimensional position: latitude, longitude, and altitude. The mathematics is based on solving a system of equations where each satellite provides one equation.

But this only works if you know where the satellites are with extreme precision. Early GPS systems had errors of tens to hundreds of meters because satellite positions were calculated less accurately. As geodetic models improved—particularly through West's work—GPS accuracy improved proportionally.

West's models improved accuracy in several specific ways. First, they reduced errors in understanding how Earth's gravity field distorts satellite orbits. Second, they provided a more accurate reference frame for mapping Earth's coordinates. Third, they enabled better calibration of satellite orbit prediction algorithms. Each improvement meant real increases in GPS accuracy that benefited users worldwide.

Research Output and Publications

West published extensively on her geodetic research. Though her work circulated primarily within specialized technical and military communities rather than mainstream scientific journals, her contributions were recognized by specialists in satellite geodesy, geophysics, and orbital mechanics.

For four decades, West contributed to the Naval Ordnance Laboratory's technical reports series, publishing findings on Earth models, satellite orbits, and geodetic techniques. Some of this work was classified—conducted under security classifications that limited who could access or cite it. That meant her contributions weren't widely visible in the broader scientific literature.

This relative invisibility was partly structural. Work done for military contractors and government agencies often remains classified or restricted in distribution. But it also reflected the broader pattern of Black women's contributions being overlooked or undervalued in scientific fields.

Yet among specialists, West was known and respected. Her mathematical models became standard reference tools. Her approaches to geodetic computation influenced how others in the field approached similar problems. Her 42 years at Dahlgren represented one of the longest continuous careers in satellite geodesy research by any American mathematician.

Estimated data highlights the stark disparities in educational resources between Black and White schools during the era of segregation, with Black schools receiving significantly less funding, materials, and training.

Breaking Barriers: A Black Woman in STEM During Segregation

The Double Discrimination

West's career achievements are remarkable in the abstract. They become extraordinary when understood in context. She pursued advanced mathematics during an era when American culture, institutions, and legal structures all told her she shouldn't exist in that role.

The barriers faced by women in STEM are well-documented. Women have been historically excluded from universities, discouraged from pursuing mathematics and science, confined to lower-status positions, and paid less than male counterparts for equivalent work. These barriers persist today, though less overtly than in the past.

But West faced compounded discrimination. She was not just a woman in mathematics—she was a Black woman. This meant she encountered racism alongside sexism. She couldn't access the same universities as white women. She couldn't join many professional organizations. She couldn't move freely in many parts of the country. She faced assumptions not just that women couldn't do mathematics, but that Black people—and especially Black women—were intellectually incapable.

Yet she persisted through all of it. She earned her degrees. She secured meaningful employment. She developed pioneering research. She achieved recognition within her specialized field. What enabled this?

Part of the answer lies in West's own resilience and intellectual determination. She clearly possessed what psychologists might call "grit"—the capacity to persist through obstacles and setbacks. Her family background, with a parent dedicated to education despite systemic constraints, shaped her values and expectations.

But another part of the answer lies in institutional structure. The HBCUs she attended—Virginia State—provided an environment where Black students could pursue advanced education. Faculty there, Black and white, created space for intellectual development that the larger segregated society denied. That space wasn't perfect. Resources were limited. But it was sufficient for exceptional students like West to thrive.

Similarly, the federal government provided employment pathways that private companies didn't. The Naval facilities at Dahlgren couldn't hire based on race alone, partly due to legal requirements for federal contractors, partly due to practical necessity for skilled technical workers. That created an opening West could move through.

Institutional Context: Working at Dahlgren

West's 42-year career at the Naval Surface Warfare Center at Dahlgren was unusual in multiple respects. First, the duration itself was remarkable. In an era when job-hopping was more common, West remained in one position for over four decades. That speaks to both her commitment to her work and the nature of the position—long-term research projects benefit from continuity of personnel who deeply understand the work's history and context.

Second, the intellectual environment at Dahlgren was collegial in many ways. It was a research facility focused on solving complex technical problems. Success in that environment depended on the quality of your mathematics and engineering, not your appearance or background. That didn't mean discrimination didn't exist—federal contractors in the 1950s through 1990s still had significant problems with racial and gender discrimination.

But the technical nature of the work created some immunity from the worst forms of discrimination. You couldn't simply assign lower-status tasks to Black employees if those employees possessed expertise no one else had. West's mathematical skills were genuinely rare. Her contributions to specific research projects had no easy substitute.

Third, West worked in an environment increasingly focused on space technology and satellites—areas where the Cold War drove government investment and priorities. The space race created urgency around technical problems that overrode some (though not all) discriminatory impulses. The government needed satellites, needed orbital mechanics calculations, needed geodetic models. If West was the person who could provide them, her race and gender became secondary to capability.

That's not moral progress—it's practical necessity. But it created space for West's work.

Recognition and Acknowledgment

For most of West's career, her work received little public recognition. Even within specialized technical communities, she wasn't well-known nationally. Her publications appeared in technical reports and specialized venues. The broader American public had no idea who she was.

This reflected a broader pattern in how scientific and technical history gets written and remembered. Often, the people who become famous are those whose work enters public consciousness or is widely cited in accessible venues. Much foundational technical work happens in specialized contexts—military research, government labs, industrial settings—where outputs remain restricted in distribution and visibility.

But there's also a specific pattern here about whose work gets remembered and celebrated. When historians of technology write about GPS, they often credit the military's vision, the engineers who built the systems, the physicists who solved related problems. They're less likely to credit the geodesists, the mathematicians who created foundational models, and especially less likely to credit women and people of color who contributed.

West's invisibility wasn't accidental. It reflected how historical narratives get constructed. If you're not teaching about women mathematicians, if you're not specifically researching Black contributions to STEM, if you're writing a history of GPS aimed at general audiences, it's easy to overlook the foundational mathematical work done by a Black woman in a government lab.

The 2018 Recognition: Why It Took 42 Years

The Delayed Recognition

West retired in 1998 after 42 years at Dahlgren. Her retirement didn't bring the fanfare that might accompany the career milestone of a pioneering scientist. There were no major profiles, no interviews in national media, no celebrations of her groundbreaking work. She had contributed to the foundation of one of humanity's most important technologies, yet she remained largely unknown outside specialized technical circles.

For two decades after her retirement, this pattern continued. West lived a private life. She was recognized within technical circles, but the broader American public had no awareness of her contributions.

Then, in 2018, things changed. West submitted a brief biography of her accomplishments to a sorority function—the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority (AKA), the historically Black women's sorority to which West belonged. Women in that organization read about her career and recognized its significance.

Why did it take a sorority connection to bring recognition? The answer lies partly in how scientific recognition operates. Much of it happens through academic institutions, major research universities, and visible publication venues. West's work, though groundbreaking, had circulated through military and government channels that academic historians often overlook.

Alpha Kappa Alpha members recognized the historical significance and helped amplify West's story. They facilitated interviews, helped connect her with journalists, and brought her to the attention of major media outlets. The organization's national platform meant that West's story could finally reach a wider audience.

The Awards and Honors (2018 Onward)

Following this initial recognition, West received multiple honors that acknowledged her career contributions. In 2018, she was inducted into the United States Air Force Space and Missiles Pioneers Hall of Fame. This honor recognized her foundational contributions to space technology—even though West herself had worked for the Navy, her geodetic models proved essential to Air Force operations as well.

That same year, West was honored as Female Alumna of the Year by the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) Awards program. This recognition highlighted both her personal achievement and what she represented: a Black woman who pursued advanced mathematics during segregation, built a distinguished career, and contributed meaningfully to transformative technology.

These honors, coming 20 years after her retirement and 60+ years after her pioneering research, acknowledge what should have been obvious decades earlier: West's work was foundational to modern technology.

But the 60-year delay in public recognition itself tells an important story. It reveals how easily transformative contributions can be overlooked when they come from people outside dominant groups. It shows how scientific narratives get constructed and reconstructed—sometimes with critical details missing until someone actively works to restore them.

Media Coverage and Public Awareness

Following the 2018 recognition, media outlets began covering West's story. The Guardian published a profile interview with her in 2020. Other publications followed. Her story began appearing in collections of overlooked women in science. Schools began teaching about her. Her name started appearing in lists of influential Black mathematicians.

This media attention served an important function. It meant that future generations would know about West's contributions. It meant that when people thought about GPS history, there was now a chance they'd learn about the geodetic mathematics that made it possible. It meant that young Black women interested in STEM could see West as a historical role model and precedent.

Yet the late recognition also raises uncomfortable questions. What does it say about our scientific culture that genuinely transformative contributions by Black women remained invisible for decades? What other contributions remain invisible? How many other Black women mathematicians, scientists, and engineers had their work overlooked or misattributed?

West's story became a touchstone for conversations about diversity in STEM precisely because it made visible a pattern that's likely broader than her individual case.

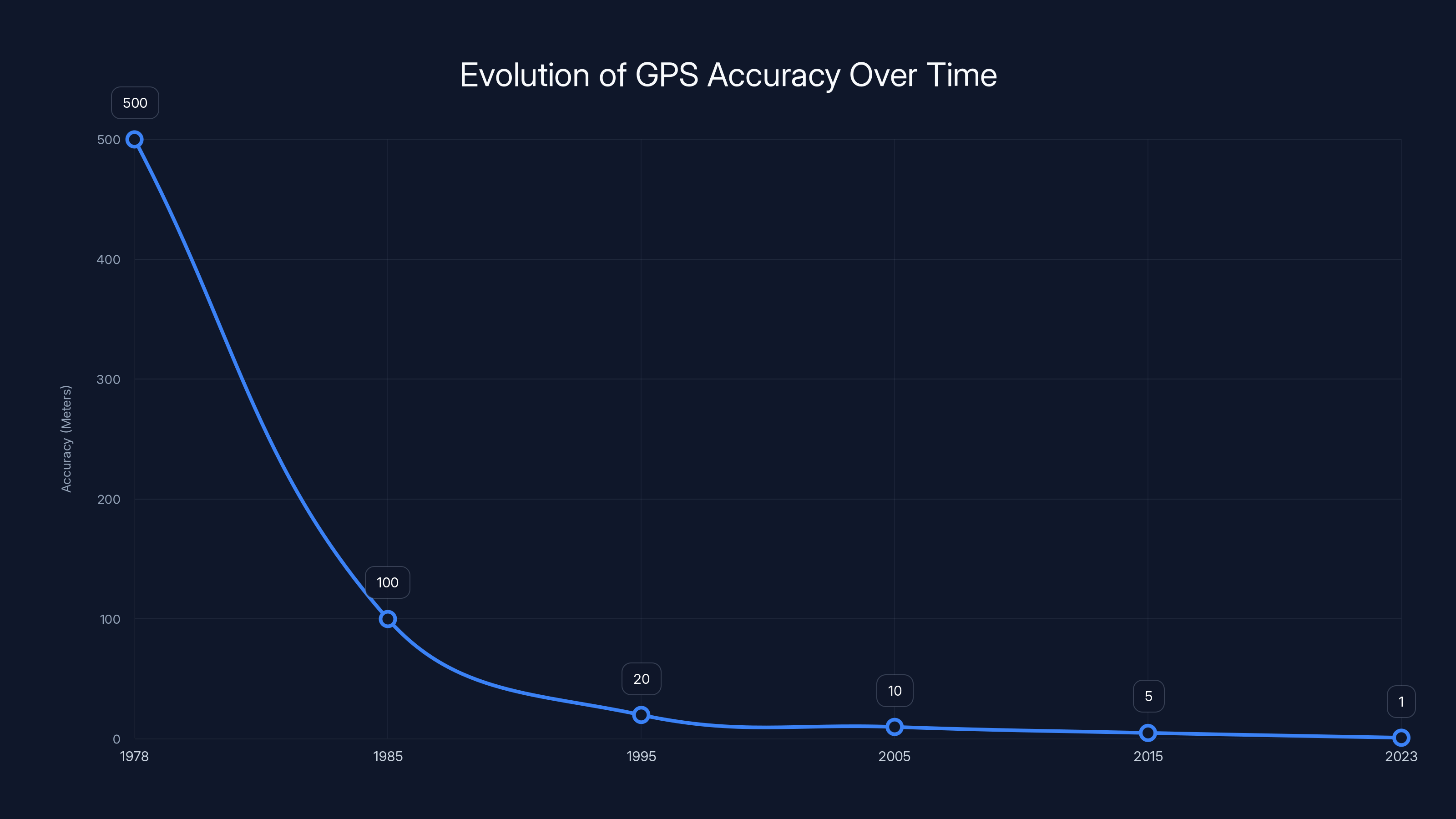

GPS accuracy has significantly improved from 500 meters in 1978 to approximately 1 meter in 2023, reflecting advancements in satellite technology and geodetic models. (Estimated data)

GPS Technology: From Theory to Global Infrastructure

The Development of GPS

Global Positioning System development began in the 1970s as a military project. The U. S. Department of Defense funded research into satellite-based navigation systems, recognizing that such systems would provide strategic advantages in military operations. If troops, ships, and aircraft could determine their precise position at any moment, tactical capabilities would improve dramatically.

The technological foundation for GPS had been developing for years. Satellite technology itself emerged from the space race. Understanding of satellite orbits had improved through both academic research and practical space missions. Radio technology had advanced considerably. Computer technology had improved sufficiently to handle the complex calculations GPS would require.

But the specific challenge GPS had to solve was determining position through satellite signals. Several approaches were considered. The system ultimately adopted involved satellites transmitting signals that included timing information and satellite location. A receiver could use signals from multiple satellites to triangulate its position.

This approach required solving a significant technical problem: the satellites carrying signals had to maintain precise orbital positions. The calculations of where satellites would be at any given moment had to be accurate to within meters. And over time, as satellites naturally drift in their orbits, position predictions had to be corrected.

This is where West's geodetic models became critical. Her mathematical models of Earth's shape and gravitational field enabled more accurate predictions of satellite orbits. They improved the accuracy of the reference frame used for position calculations. They provided the mathematical foundation that let the system work.

GPS Deployment and Accuracy Evolution

The first GPS satellite launched in 1978. The system achieved initial operational capability in 1983, though full deployment took years more. Early accuracy was modest—100 to 300 meters for civilian users, better for military users with access to encrypted signals. These limitations reflected both technical constraints and deliberate degradation applied to civilian signals for national security reasons.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, accuracy improved significantly. Better satellites, improved transmitters, more sophisticated receiver algorithms, and—critically—better geodetic models all contributed. By the 1990s, civilian accuracy had improved to 10-30 meters. Military accuracy exceeded 1 meter.

These improvements trace partly to West's work and the work it inspired. Her geodetic models became standard references. Her approaches to modeling Earth's shape influenced how subsequent researchers approached similar problems. The improvements she pioneered in understanding orbital mechanics contributed to the ability to maintain satellite positions more accurately.

The Civilian GPS Revolution

In 2000, the U. S. government removed artificial degradation from civilian GPS signals. This was partly due to pressure from allies and commercial users, partly recognition that civilian applications had become economically important. Suddenly, civilian GPS devices achieved meter-level accuracy instead of being deliberately degraded to 100+ meters.

That same year marked the beginning of rapid civilian GPS adoption. Within years, consumer GPS devices proliferated. Smartphones began incorporating GPS. Mapping services evolved. Logistics companies optimized routing using GPS. Emergency services deployed GPS-equipped vehicles.

This massive civilian GPS infrastructure—worth trillions in economic value, touching billions of people daily—depends on the same mathematical foundations West developed. The geodetic models, the understanding of Earth's shape and gravitational field, the mathematical frameworks for predicting satellite orbits: all of this traces back to work like hers.

The Broader Context: Black Women in Mathematics and STEM

Historical Patterns of Erasure

West's story of delayed recognition is not unique. It's part of a broader historical pattern where contributions by Black women to science and technology have been systematically overlooked, undervalued, or misattributed.

The most famous contemporary example is probably the "Hidden Figures" story: Black women mathematicians at NASA whose computational work was critical to the space program but remained largely unknown until a 2016 book and 2017 film brought attention to them. Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, and others contributed directly to NASA's success, yet most Americans had never heard their names until these contemporary accounts.

But the pattern extends far beyond NASA. Black women made significant contributions to early computer science, mathematics, physics, biology, and engineering. Yet in historical accounts, their work is often invisible or attributed to others.

Why does this happen? Several factors contribute:

Institutional invisibility: Much work by Black women happened in non-academic settings—government labs, military contractors, industry—where outputs might be classified or restricted in distribution. Academic histories of science often focus on universities and published literature, missing important work done elsewhere.

Lack of institutional positions: Historically, Black women couldn't access most academic positions. Without faculty status or university affiliations, their work was less likely to be recognized through academic channels.

Documentation gaps: Professional histories often rely on networks and connections. Black women often operated outside dominant professional networks. Their work was less likely to be discussed in professional meetings, mentioned in influential publications, or included in historical narratives constructed by those networks.

Deliberate exclusion: Sometimes the invisibility was active. Female scientists' work was attributed to male colleagues. Black scientists were excluded from professional organizations. Contributions were minimized or dismissed.

Narrative construction: How we tell the history of science matters. If we write histories of GPS without mentioning geodesists, we're already excluding vast categories of contributors. If we don't specifically look for women and Black contributors, we'll miss them.

The Black Mathematics Community

Despite systemic barriers, Black mathematicians have made significant contributions throughout American history. David Blackwell, pioneering statistician and game theorist. Elbert Frank Cox, first Black American to earn a Ph D in mathematics. Katherine Johnson, computer and mathematician at NASA. Vivette Alston, fluid dynamicist and first Black woman to join Bell Labs. Shirley Ann Jackson, physicist and Bell Labs researcher. Gloria Conyers Hewitt, differential equations mathematician.

West represents both this tradition of Black mathematical excellence and the pattern of limited recognition. She built on foundations created by earlier Black mathematicians who had fought for educational and professional access. Her success made it possible for subsequent Black mathematicians to imagine the field as a possibility for themselves.

Yet most Americans have heard of few Black mathematicians. The same educational systems that fail to teach Black history broadly also fail to teach Black mathematical and scientific history specifically. Students learn about Newton and Einstein, but not about Black physicists and mathematicians whose work was equally sophisticated and impactful within their domains.

West's recognition beginning in 2018 is part of a broader reclamation of this history. It signals that we're finally starting to acknowledge contributions that should have been obvious all along.

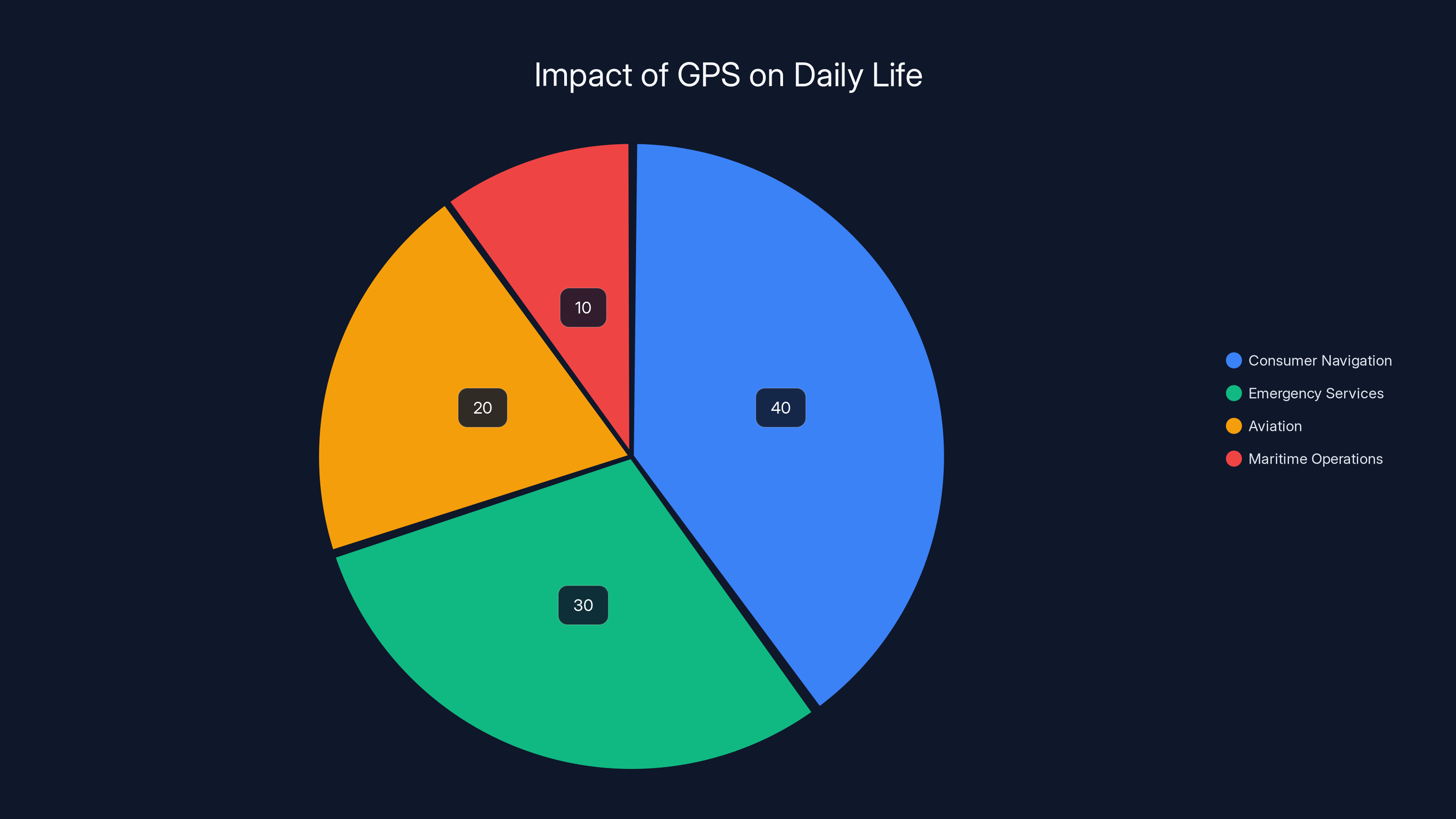

Estimated data shows consumer navigation as the largest GPS application, followed by emergency services, aviation, and maritime operations. This highlights the broad impact of GPS technology on daily life.

GPS Applications: How West's Work Transformed Daily Life

Navigation and Mapping

The most obvious GPS application is consumer navigation. Billions of people use GPS-based navigation daily—driving with GPS guidance, getting directions through smartphone maps, using fitness tracking apps that record routes and distances.

This entire ecosystem depends on the infrastructure West's work helped create. When your navigation app calculates your position, it's using GPS satellites whose orbital positions are predicted using geodetic models. The accuracy that makes navigation useful—knowing you're at an intersection rather than somewhere in the next block—comes from decades of geodetic refinement, starting with work like West's.

Consider the difference between 1970s navigation (paper maps, best guesses on position) and today's navigation (real-time positioning to within meters, dynamic route optimization based on current conditions). That transformation happened because satellite positioning technology matured, accuracy improved, and computing became powerful enough to process satellite signals in real-time. West's work was essential to the accuracy improvements.

Emergency Response and Public Safety

Emergency services depend critically on GPS. When someone calls 911, dispatchers use GPS from mobile phones to locate callers within seconds. Ambulances navigate to emergencies using GPS. Fire departments use GPS-coordinated positioning to understand where all units are deployed. Rescue services use GPS to find lost hikers or shipwrecked people.

In 2022, approximately 2.8 million lives were saved globally through location technology and related rescue operations—a number that would be impossible without satellite positioning systems. The accuracy required for these applications, the reliability of the system, and the global coverage all trace back to infrastructure that West's geodetic work helped establish.

Aviation and Maritime Operations

Commercial aviation depends on GPS. Aircraft use GPS for precise positioning, especially during approach and landing phases of flight. GPS enables more efficient routing, saving fuel and reducing emissions. GPS coordinates flight paths to millimeter precision, enabling safe aircraft separation.

Maritime operations similarly depend on GPS for navigation, vessel tracking, collision avoidance, and rescue coordination. Modern cargo ships, commercial fishing vessels, and naval operations all use GPS as a fundamental technology.

The accuracy and reliability these applications require wouldn't be possible without the geodetic foundations that West and her peers developed. When an aircraft uses GPS to guide its approach to landing, it's relying on systems whose foundational mathematics originated in work like hers.

Infrastructure and Land Management

GPS enables survey work, construction coordination, pipeline management, power grid operations, and land management. Engineers use GPS to establish reference points for construction projects. Utilities use GPS to manage distributed infrastructure. Governments use GPS to maintain accurate property records.

Agriculture uses GPS-guided tractors for precision farming, reducing fertilizer use and improving yields. Logistics companies use GPS to optimize routes and track shipments. Mining operations use GPS to coordinate equipment and manage resource extraction.

All of this depends on the positioning accuracy that the GPS system provides. That accuracy depends on the infrastructure West helped build.

Scientific Research

Scientists use GPS across numerous fields. Seismologists use GPS networks to detect ground motion and earthquake strain. Glaciologists use GPS to measure ice sheet movements and sea level rise related to climate change. Oceanographers use GPS to track buoys and understand ocean currents. Atmospheric scientists use GPS for precision measurements of atmospheric layers.

The ability to make measurements accurate to centimeters and monitor changes over years depends on GPS infrastructure. West's geodetic work established foundations that make these scientific applications possible.

The Mathematics of Geodesy: Understanding Earth

Reference Frames and Coordinate Systems

Before satellites, geodesy worked by measuring distances and angles between points on Earth's surface. Surveyors would establish networks of reference points and measure angles to distant peaks, using trigonometry to calculate distances and positions. This approach works but has fundamental limitations—you can only measure what you can see.

Satellites changed this entirely. Satellites circle Earth in known orbits. If you can measure the position of a satellite precisely and know its orbit, you can use that satellite's position as a reference for ground-based measurements.

But here's the key challenge: to use satellites as position references, you need an accurate model of Earth's shape. You need to know exactly where Earth's surface is relative to your coordinate system. This is what geodetic reference frames accomplish.

West's work contributed to developing and refining these reference frames. She created mathematical models of Earth's shape that accounted for the equatorial bulge, polar flattening, and local gravitational anomalies. These models enabled more accurate transformations between satellite observations and ground-based positions.

The Geoid: Mapping Earth's Gravity

One of geodesy's central challenges is understanding the geoid—the equipotential surface that would be defined by ocean level if continents and land topography didn't exist. The geoid isn't a perfect sphere because Earth's gravitational field is uneven. Dense rock formations create slightly stronger gravity. Ocean basins have slightly weaker gravity.

Measuring and modeling the geoid requires precise measurements of gravitational acceleration at points around Earth. Satellites provide a way to do this. As satellites orbit, variations in Earth's gravity affect their positions slightly. By measuring these variations, you can infer the geoid's shape.

West's work involved using satellite data to improve geoid measurements. Her mathematical models of Earth incorporated improved understanding of the geoid, which in turn improved satellite orbit predictions.

This might sound abstract, but it's practically important. When GPS calculates your position, it's referring that position to a specific geodetic reference frame that includes assumptions about the geoid. More accurate geoid models mean more accurate GPS positioning.

Orbital Mechanics and Perturbations

Satellites don't follow perfectly stable orbits. Their paths are perturbed—slightly altered—by various forces:

Gravitational perturbations: Non-uniform gravity from Earth's mass distribution causes satellites to deviate from Keplerian orbits (the simple elliptical orbits that would result from spherically symmetric gravity). Understanding these perturbations requires precise knowledge of Earth's gravitational field.

Atmospheric drag: At orbital altitudes where satellites operate, there's still a thin atmosphere. Atmospheric molecules collide with satellites, causing slight drag that gradually lowers orbits. The amount of drag depends on atmospheric density, which varies with solar activity and other factors.

Radiation pressure: Sunlight exerts pressure on satellites. This is minute but accumulates over time, particularly for satellites with large solar panels. Relativistic effects: At satellite speeds, relativistic effects on time and gravity become measurable. Clocks on satellites run at slightly different rates than ground clocks. Accounting for this requires relativistic calculations.

West's work involved modeling these perturbations accurately so that satellite orbits could be predicted precisely. The better the perturbation models, the better the orbit predictions, and thus the better the GPS positioning accuracy.

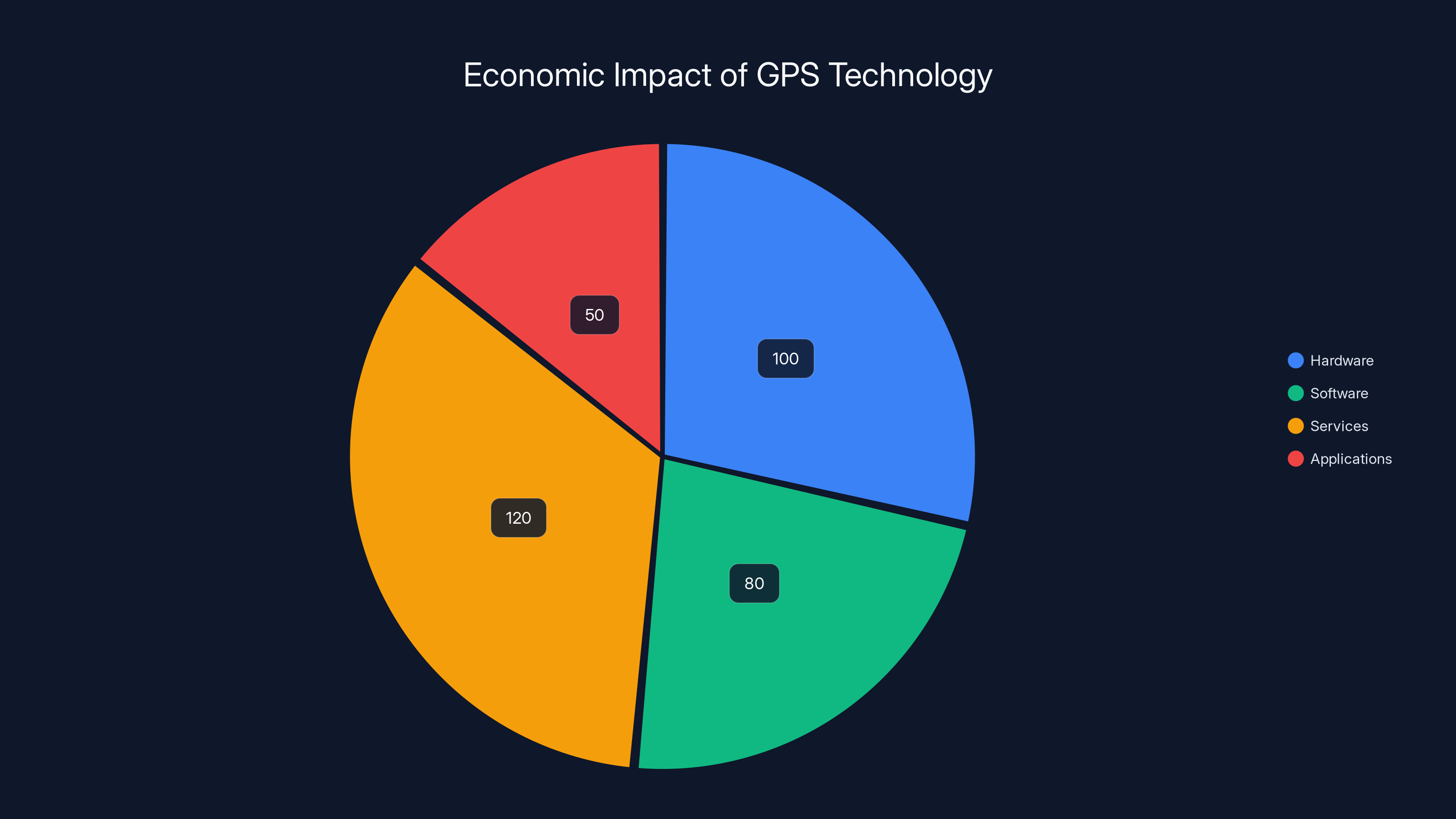

The global GPS market, valued at over $350 billion, is distributed across hardware, software, services, and applications. Services hold the largest share, highlighting the extensive use of GPS in various industries. (Estimated data)

The Legacy: How West's Work Shaped Modern Technology

Direct Technological Impact

West's contributions had direct technological impact in several ways:

GPS accuracy: The geodetic models she developed improved GPS accuracy by enabling better satellite orbit predictions and more accurate reference frames. These improvements happened incrementally—each refinement contributed to the overall accuracy evolution.

Satellite positioning: Her work on Earth's gravitational model improved predictions of how satellites would move in orbit. This enabled both better GPS performance and better performance of other satellite systems.

Computational methods: West developed mathematical and computational approaches to geodetic problems that influenced how subsequent researchers tackled similar challenges. These methodological contributions continue influencing satellite geodesy research.

Standardization: Her geodetic models influenced the development of geodetic standards used globally. The World Geodetic System (WGS 84), which is the reference frame used by GPS, incorporated lessons from work like hers.

Economic and Social Impact

The economic impact of GPS technology is enormous. The global market for GPS and location-based services exceeds $350 billion annually. This includes hardware, software, services, and applications built on top of GPS infrastructure.

Beyond the direct market, GPS enables entire industries and practices. Precision agriculture uses GPS to optimize farming and reduce environmental impact. Logistics optimization saves fuel and emissions. Emergency services save lives. Scientific research studies climate change, earthquake risk, and other phenomena.

All of this economic and social value depends on the infrastructure that West's work helped create. While she wasn't the only contributor—many engineers, physicists, mathematicians, and technicians contributed—her foundational role was critical.

It's also worth noting that West's contributions were public—funded by taxpayer money through the government. She developed work that became a public resource, though for many decades her contribution remained invisible to the public.

Scientific Influence and Continuing Research

West's work influenced how subsequent scientists approached geodetic and gravitational problems. Her mathematical frameworks and modeling approaches shaped the discipline. Research building on her work has continued improving our understanding of Earth and refining GPS systems.

The modern Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) ecosystem includes not just American GPS but also European Galileo, Russian GLONASS, and Chinese Bei Dou systems. All of these systems depend on similar geodetic principles and mathematical foundations that trace back to work West and her peers pioneered.

Current research in geodesy—including work on understanding how Earth's mass distribution changes due to groundwater depletion, ice sheet melting, and other climate-related phenomena—builds on foundational understanding that West's work helped establish.

Recognizing Hidden Figures: What West's Story Teaches Us

The Importance of Intentional Historical Recovery

West's story only entered public consciousness because people intentionally worked to recover and share it. Her sorority recognized her accomplishments and helped amplify her story. Journalists wrote about her. Historians incorporated her work into broader narratives. Her honors were publicized.

This raises an important point: historical visibility doesn't happen automatically. The contributions that get remembered are often those explicitly highlighted and promoted. If we rely on "naturally" emerging historical narratives, we're likely to continue overlooking contributions by people outside dominant groups.

Deliberate effort is required to recover overlooked contributions. This means:

- Teaching diverse scientific history: Including Black mathematicians, women scientists, and other overlooked contributors in what we teach students

- Supporting historical research: Funding work by historians investigating overlooked contributions

- Celebrating and honoring overlooked contributors: When we discover overlooked historical figures, actively recognizing their importance

- Questioning historical narratives: Asking whose contributions are missing from standard stories and actively seeking those contributions

Implications for Current STEM Diversity

West's career, while successful, happened within profoundly constrained circumstances. She achieved despite systemic barriers that were designed to exclude her. The fact that we're only now recognizing her suggests those barriers may not have fundamentally changed as much as we'd like to believe.

For Black women entering STEM today, West's story offers both inspiration and a cautionary tale. It shows that achievement is possible even in hostile circumstances—but it also shows that achievement doesn't guarantee recognition, particularly for women and people of color.

Current diversity initiatives in STEM often focus on access—getting more women and people of color into educational programs and career pipelines. That's necessary. But West's experience suggests we also need to focus on recognition, value, and equitable distribution of credit.

When Black women and other underrepresented people do work in STEM, that work needs to be:

- Properly credited: Not attributed to others or erased

- Publicly recognized: Not left invisible in specialized domains

- Valued appropriately: Not dismissed as less important than work by majority group members

- Integrated into historical narratives: Not treated as exceptions but as essential parts of scientific history

Moving Forward: From Hidden Figures to Visible Contributors

The "hidden figures" metaphor—which describes overlooked contributors as "hidden"—is revealing. It places the burden on those whose work was overlooked, treating visibility as accidental. A better framing would recognize that these contributions were deliberately or systematically made invisible.

Moving forward means:

Building inclusive institutions: Creating environments where Black women, women of color, Indigenous people, and other underrepresented groups can thrive and receive equal recognition.

Diversifying decision-making: Ensuring that people from diverse backgrounds participate in decisions about what research gets funded, what gets published, what gets celebrated.

Changing professional incentives: Rewarding people for work that's immediately visible in major publications isn't the same as recognizing all valuable contributions. That might mean reevaluating how we measure scientific impact and professional success.

Teaching diverse history: Making sure students learn about the contributions of people from all backgrounds, not just dominant groups.

Supporting public communication: When we discover overlooked contributors, publicly sharing their stories so they become part of shared historical knowledge.

West's 2018 recognition represents progress. But the fact that it took 42 years after her retirement, 60+ years after her pioneering research, suggests how much work remains.

Technology's Unrecognized Foundations: Other Cases of Overlooked Contributions

Hidden Work Behind Visible Technology

West's case isn't unique in this regard. Many technologies that seem to have obvious origins actually depend on contributions by overlooked people. Consider:

The internet: While we know about figures like Tim Berners-Lee (who created the World Wide Web) and pioneers like Vannevar Bush (who conceptualized hyperlinked information systems), we're less likely to know about Black researchers who contributed to networking protocols, security systems, and foundational computer science concepts.

Cellular technology: The development of cellular networks involved thousands of engineers and mathematicians, including many women and people of color whose contributions were rarely mentioned in public accounts of cellular technology's history.

Medical imaging: The development of MRI and CT imaging involved contributions from physicists, engineers, and mathematicians from diverse backgrounds whose names rarely appear in popular accounts.

Telecommunications: The history of telecommunications involves crucial contributions by women mathematicians and engineers—many of them overlooked in standard histories.

In each case, the pattern is similar: transformative technology developed through contributions by many people, yet historical narratives often emphasize founders and high-profile figures while overlooking everyone else, particularly people from underrepresented groups.

Systemic Causes of Invisibility

Why does this happen repeatedly? Several factors:

Institutional positioning: Contributions by people outside major academic and corporate centers are less likely to be documented and remembered.

Network effects: Professional recognition travels through networks. Being outside dominant professional networks means your work is less likely to be known and celebrated.

Publication and attribution: Academic careers advance through published research and citations. Work that remains in technical reports, company labs, or restricted-distribution contexts gets less academic attention and citation.

Narrative simplification: When we tell technology histories, we often simplify to focus on key figures and decisions. That simplification tends to exclude people from underrepresented groups.

Deliberate erasure: Sometimes invisibility reflects active choices—denying credit to people from certain groups, excluding them from professional organizations, attributing their work to others.

Understanding these systemic causes suggests that fixing the problem requires systemic change, not just individual recognition of overlooked contributors.

Lessons for Science and Society

The Value of Diverse Perspectives

One argument for diversifying STEM isn't just moral justice (though that matters). Diversity also produces better science. When research teams include people from different backgrounds with different experiences and perspectives, they approach problems differently. They notice things majority-group researchers might miss. They identify promising directions others might overlook.

West's approach to geodesy, shaped by her particular background and path to mathematics, likely influenced her perspective on problems and solutions. We can't know exactly how differently she thought compared to white male geodesists, but her contributions suggest she brought valuable insights to work that could have been approached in limited ways by a more homogeneous group.

More broadly, the assumption that good science comes only from a limited demographic subset is itself scientifically unfounded. Talent is distributed across all populations. When we restrict access to STEM, we're leaving talent on the table.

Institutional Accountability

West's delayed recognition raises questions about institutional accountability. The organizations where she worked—the federal government, the Naval Surface Warfare Center—benefited from her work for 42 years. Yet for decades, they apparently made no effort to publicly recognize her contributions.

Should institutions be held accountable for recognizing the contributions of all their workforce members? What obligations do institutions have to ensure equitable credit and recognition? These questions become particularly sharp when we consider that West's work became the foundation for a transformative global technology, yet her role remained invisible for decades.

Modern institutions can learn from this pattern. They should:

- Document contributions: Maintain records of who contributed to significant projects and discoveries

- Recognize achievements: Actively recognize the contributions of all employees, particularly those who might otherwise be overlooked

- Support public engagement: Help employees share their work and receive recognition for it

- Correct historical records: When oversights are discovered, actively work to correct them

Personal Initiative and Collective Action

West's story also demonstrates the importance of personal initiative. She took the step of sharing her accomplishments with her sorority, which then amplified her story. Her own action—writing a brief biography for a sorority function—created the opening that eventually led to broader recognition.

Yet relying on individual action alone is insufficient. Systems need to be structured so that overlooked contributions naturally emerge, rather than depending on individuals to fight for recognition.

This suggests the importance of collective action—communities, organizations, and social groups working together to restore overlooked history and ensure equitable recognition. West's sorority played this role, as did the HBCU awards program and journalists who covered her story.

The Global Impact: GPS Around the World

GPS as Global Infrastructure

GPS is fundamentally global infrastructure. Satellites circle Earth, providing positioning service to anyone with a receiver. This creates an interesting situation where American-developed technology became universal infrastructure that benefited everyone globally.

The economic value generated by GPS operates globally. GPS-enabled services in every country depend on the satellite infrastructure and the mathematical foundations that West's work helped establish. In that sense, her contributions have global impact that extends far beyond American borders.

Developing Countries and Equitable Access

That said, access to GPS technology hasn't been equally distributed. In early years, GPS was restricted for military and commercial use in developed countries. Civilian access improved over time, but capabilities and quality of service have varied globally.

Now, GPS is widely available globally through smartphone devices and dedicated receivers. This has enabled applications in developing countries—emergency services, agriculture, logistics, research—that wouldn't have been possible otherwise.

Yet the infrastructure remains fundamentally dependent on American satellite systems and American-developed mathematical foundations. This creates interesting questions about technology equity and dependency. Countries benefit from American-developed infrastructure without paying licensing fees or royalties. That's positive for equity. But it also means technological dependence on American systems.

West's contributions to this global infrastructure are shared globally, though few people worldwide know her name or understand her role.

FAQ

What were Dr. Gladys West's main contributions to GPS?

Dr. West developed highly accurate mathematical models of Earth's shape and gravitational field using satellite data during the 1970s and 1980s. These geodetic models became fundamental to GPS accuracy by enabling better predictions of satellite orbits and establishing reference frames for position calculations. Without these mathematical foundations, GPS would have been significantly less accurate.

Why was Dr. West's work not recognized for so long?

West's contributions remained largely invisible for decades due to several factors: her work was conducted in military/government labs rather than academia, results circulated in restricted technical reports rather than widely-cited publications, and historical narratives about technology often overlook contributions by Black women scientists. The systemic invisibility of her work reflected broader patterns of overlooked contributions by women and people of color in science and technology.

How did Jim Crow segregation affect Dr. West's career path?

Segregation severely limited West's educational and professional options. She couldn't attend most American universities—only historically Black colleges were accessible to her. Career opportunities in academia and private industry were essentially closed to Black women mathematicians. The federal government provided pathways that private employers didn't, which is why she was hired at a naval facility where merit-based technical work could overcome some (though not all) discriminatory barriers.

What is geodesy and why is it important for GPS?

Geodesy is the mathematical science of measuring and understanding Earth's physical characteristics—its shape, size, gravitational field, and coordinate systems. GPS requires knowing satellite positions with extreme precision, which depends on understanding how Earth's gravity influences satellite orbits. Accurate geodetic models enable accurate GPS positioning. West's geodetic work directly improved GPS accuracy by refining our understanding of Earth's gravitational field.

How has GPS technology evolved since Dr. West's foundational work?

GPS accuracy has improved dramatically from roughly 100 meters in the 1980s to centimeter-level accuracy for specialized applications today. These improvements came from better satellites, more sophisticated receivers, improved algorithms, and refinements to geodetic models built on foundations like West's work. Modern multi-constellation GNSS systems (GPS, Galileo, GLONASS, Bei Dou) use similar mathematical principles that West and her peers pioneered.

What can we learn from Dr. West's experience about diversity in STEM?

West's story reveals both the possibility of achievement despite systemic barriers and how easily that achievement can be overlooked. While her success is inspiring, the 60+ year delay in public recognition suggests that systemic change is needed beyond just individual achievement. This includes diversifying institutions, ensuring equitable credit and recognition, changing incentive structures, and actively recovering overlooked historical contributions.

How does West's work continue to influence current GPS systems?

Modern GPS systems remain dependent on geodetic reference frames and gravitational models that trace their lineage to work West pioneered. The World Geodetic System 84 (WGS-84), used globally by GPS, incorporates decades of refinement building on foundational geodetic work from the 1970s-1980s. Current research in satellite geodesy—including work on climate change, sea level rise, and gravitational modeling—continues building on frameworks West helped establish.

What recognition did Dr. West eventually receive for her contributions?

Dr. West's contributions were publicly recognized beginning in 2018, sixty years after her pioneering research. She was inducted into the United States Air Force Space and Missiles Pioneers Hall of Fame and honored as Female Alumna of the Year by the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) Awards. She received multiple media interviews and was featured in educational materials about overlooked women in science.

Conclusion: A Legacy That Continues

Dr. Gladys West passed away on February 13, 2024, at the age of 95. Her death closed the chapter on a remarkable life, but her legacy continues circling Earth above us—quite literally, in the satellites whose orbits her mathematics help predict. Every GPS signal you receive, every navigation app that guides you, every emergency service that locates people in crisis, every scientific measurement that advances our understanding of Earth: all of these trace back to mathematics West pioneered.

Her story matters for many reasons. First, it's a story about mathematics. West's work demonstrates that brilliant mathematical thinking can come from anywhere. It shows that solving real-world problems requires sophisticated abstract mathematics combined with practical computational skill. It proves that the foundation for transformative technology often comes from mathematical insights that seem abstract until they're applied.

Second, it's a story about resilience and achievement against systemic barriers. West pursued mathematics during segregation when Black women mathematicians essentially didn't exist in American society. She built a 42-year career doing work of genuine significance. She achieved this without the advantages that made careers easier for white male scientists. Her success is testimony to her determination, intelligence, and commitment to her work.

Third, it's a story about invisible contributions and overlooked history. West's delayed recognition reveals how easily the work of talented people gets overlooked when those people come from outside dominant groups. It shows that historical narratives aren't neutral records of what happened—they're constructed through choices about what to emphasize, what to celebrate, what to remember. Those choices tend to favor contributions by people already in positions of visibility and power.

Fourth, it's a story about systemic patterns that continue today. The barriers West faced—racism, sexism, exclusion from professional networks and institutions—have improved but not disappeared. Black women remain underrepresented in STEM. Their contributions continue being undervalued and overlooked. Understanding West's experience helps us recognize these patterns in current systems and motivates change.

Finally, it's a story about why diversity in science matters. When research and development communities are restricted to narrow demographic groups, they're restricted in perspective and capability. They miss insights that diverse groups would bring. They leave talent untapped. Actively building diverse communities in STEM isn't just justice, though that matters—it's practical: better science comes from diverse teams working on problems together.

West's mathematics transformed how humanity navigates and understands the world. Her life transformed understanding about what's possible despite systemic barriers. Her delayed recognition transformed conversations about whose contributions get remembered and celebrated.

She remains, even in death, a teacher—showing us what we might accomplish, what we overlook, and what we might become if we truly valued all contributions to human knowledge and achievement.

The satellites continue circling, guided by mathematics developed by a Black woman mathematician who made the world larger and more navigable. That's her legacy. It's more than enough.

Key Takeaways

- Dr. Gladys West developed mathematical models of Earth's shape using satellite data (1970s-1980s), directly enabling modern GPS accuracy

- Despite pioneering work, West's contributions remained publicly unrecognized for 42 years after retirement, reflecting systemic invisibility of Black women scientists

- West overcame Jim Crow segregation, gender discrimination, and professional barriers to build a distinguished 42-year career at Naval Surface Warfare Center

- GPS accuracy improvements from 100+ meters (1980s) to centimeter-level precision (today) trace to geodetic foundations West and contemporaries established

- West's delayed 2018 recognition illuminates how historical narratives about technology overlook contributions by people outside dominant groups, suggesting need for systematic change

Related Articles

- 2026 World Cup AI Technology: How Lenovo is Revolutionizing Football [2025]

- Why Apple's Move Away From Titanium Was a Design Mistake [2025]

- Artemis II: The Next Giant Leap to the Moon [2025]

- Netflix's New Pirate Series with Ed Westwick & John Hannah [2025]

- Nikon Viltrox Lawsuit: What It Means for Z-Mount Lenses [2025]

- Polar Grit X2 Review: Rugged Features at a Lower Price [2025]

![Dr. Gladys West: The Hidden Mathematician Behind GPS [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/dr-gladys-west-the-hidden-mathematician-behind-gps-2025/image-1-1768867732803.jpg)