The EPA's Historic Reversal: Understanding the Endangerment Finding Crisis

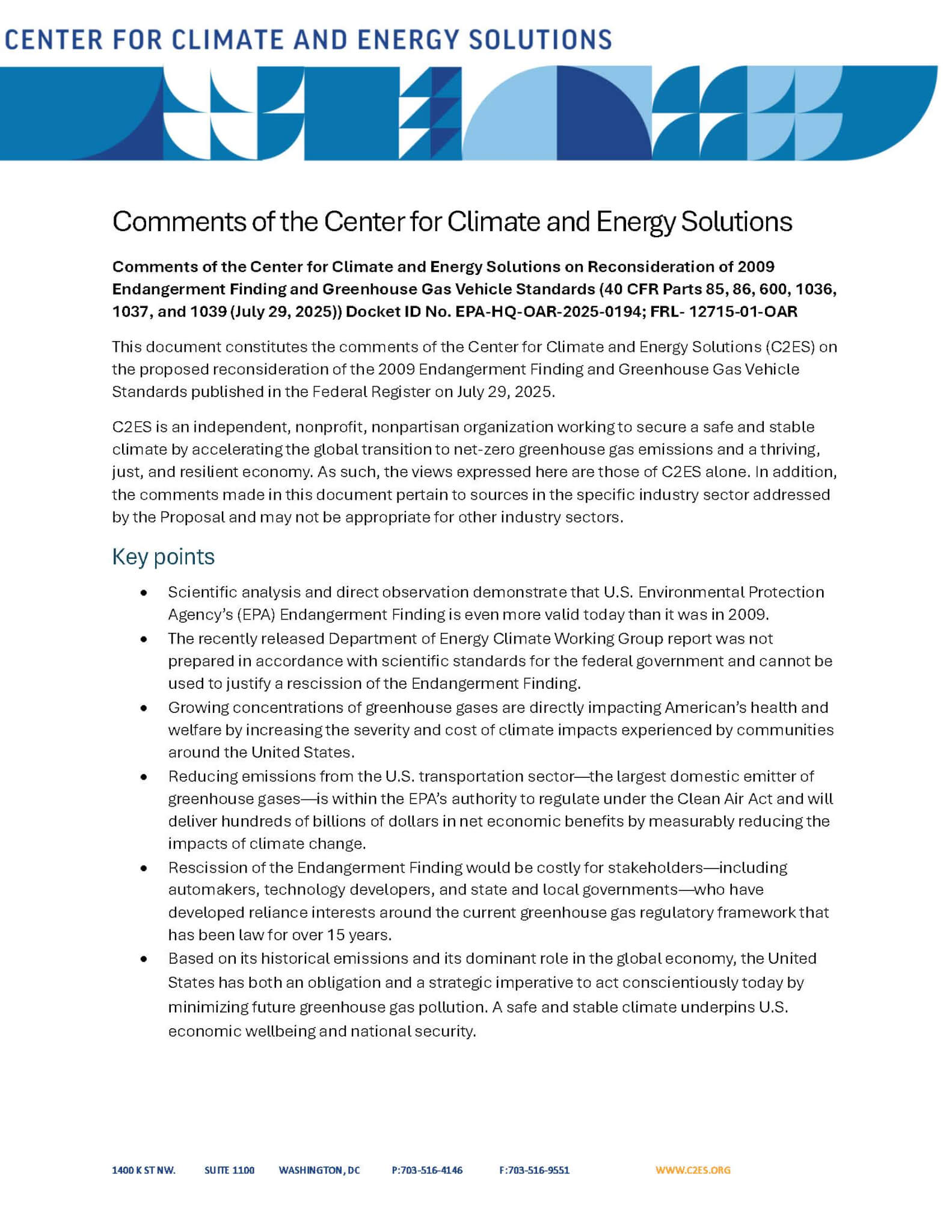

In February 2025, the Environmental Protection Agency made a decision that shook the foundation of nearly two decades of climate policy. The agency announced it was revoking the endangerment finding—a scientific document that has served as the legal basis for regulating greenhouse gas emissions from cars, power plants, and industrial facilities across America.

This wasn't a quiet bureaucratic shuffle. This was a deliberate dismantling of the very framework that made modern climate regulation possible in the United States. To understand why this matters, you need to know the history of how we got here, why the endangerment finding exists, and what the EPA's decision actually accomplishes.

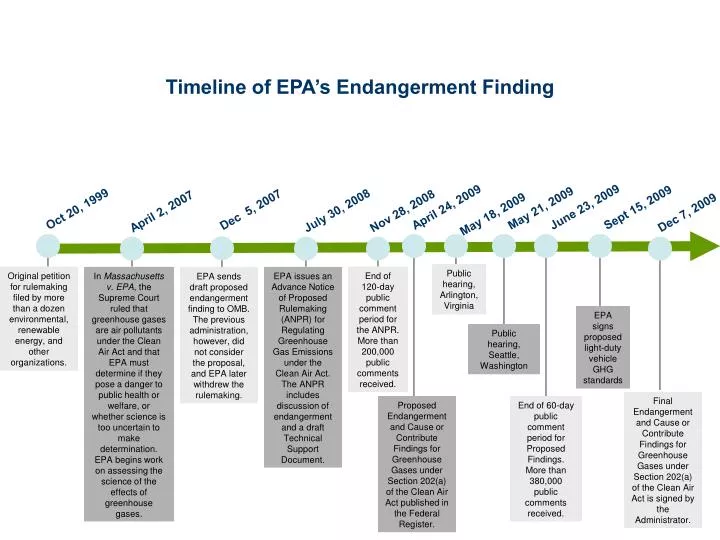

Let's start with the basics. In 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling in Massachusetts v. EPA that required the EPA to determine whether greenhouse gases pose a threat to human health and the environment. The Court essentially said: if you think something is dangerous, the law requires you to regulate it. There's no wiggle room for politics or ideology. Either the science shows it's dangerous, or it doesn't.

The Obama administration took that ruling seriously. In 2009, the EPA issued the endangerment finding, a comprehensive scientific assessment concluding that greenhouse gases—primarily carbon dioxide—do indeed endanger public health and welfare. This wasn't some environmental advocacy group making this argument. This was the EPA, using peer-reviewed science and climate models, stating as a matter of fact that human-caused climate change is real and poses measurable risks to Americans.

That finding became the legal scaffold for every major climate regulation that followed. The fuel economy standards that pushed automakers toward electric vehicles. The carbon pollution standards for power plants. The methane emissions rules for oil and gas facilities. All of these regulations rested on the foundation that the EPA had established in that 2009 endangerment finding.

When Trump took office in 2017, his first EPA administrator Scott Pruitt wanted to overturn the endangerment finding outright. But he didn't. Why? Because the science was too strong, and challenging it head-on would invite immediate lawsuits that the administration would probably lose. It was easier politically to leave the finding in place and simply refuse to enforce the regulations it supposedly required.

Now, in his second term, Trump's EPA is taking a different gamble. Instead of ignoring the endangerment finding, they're revoking it entirely. And they're banking on a Supreme Court majority that has shown little love for environmental regulations to overturn the 2007 Massachusetts v. EPA decision that started this whole thing.

This is a high-stakes constitutional bet. Here's what's really happening beneath the surface.

The 2007 Supreme Court Decision That Changed Everything

To understand why the Trump administration is making this move now, you need to go back to 2007. At that time, the Bush administration's EPA had essentially ignored a petition from states and environmental groups asking the agency to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act.

The Bush administration's reasoning was straightforward and convenient: greenhouse gases aren't specifically mentioned in the Clean Air Act, and besides, Congress didn't intend for the EPA to regulate something as global as climate change. Case closed. Except it wasn't.

Massachusetts and other states, along with environmental groups, sued. And they won in a way that changed everything. The Supreme Court's 5-4 decision said that under the language of the Clean Air Act, the EPA has the authority to regulate any air pollutant that affects public health. Greenhouse gases fit that description. Unless the EPA could provide a scientific reason why greenhouse gases don't endanger public health, the law required regulation.

This was significant for one simple reason: it removed discretion from the equation. The EPA couldn't just choose not to regulate something harmful. The Clean Air Act is written in mandatory language. It says the EPA "shall" regulate pollutants that endanger public health. There's no "may" in there. There's no room for political judgment about whether it's convenient to regulate something.

The Bush administration, faced with this ruling, essentially ran out the clock. The endangerment finding was completed under Obama.

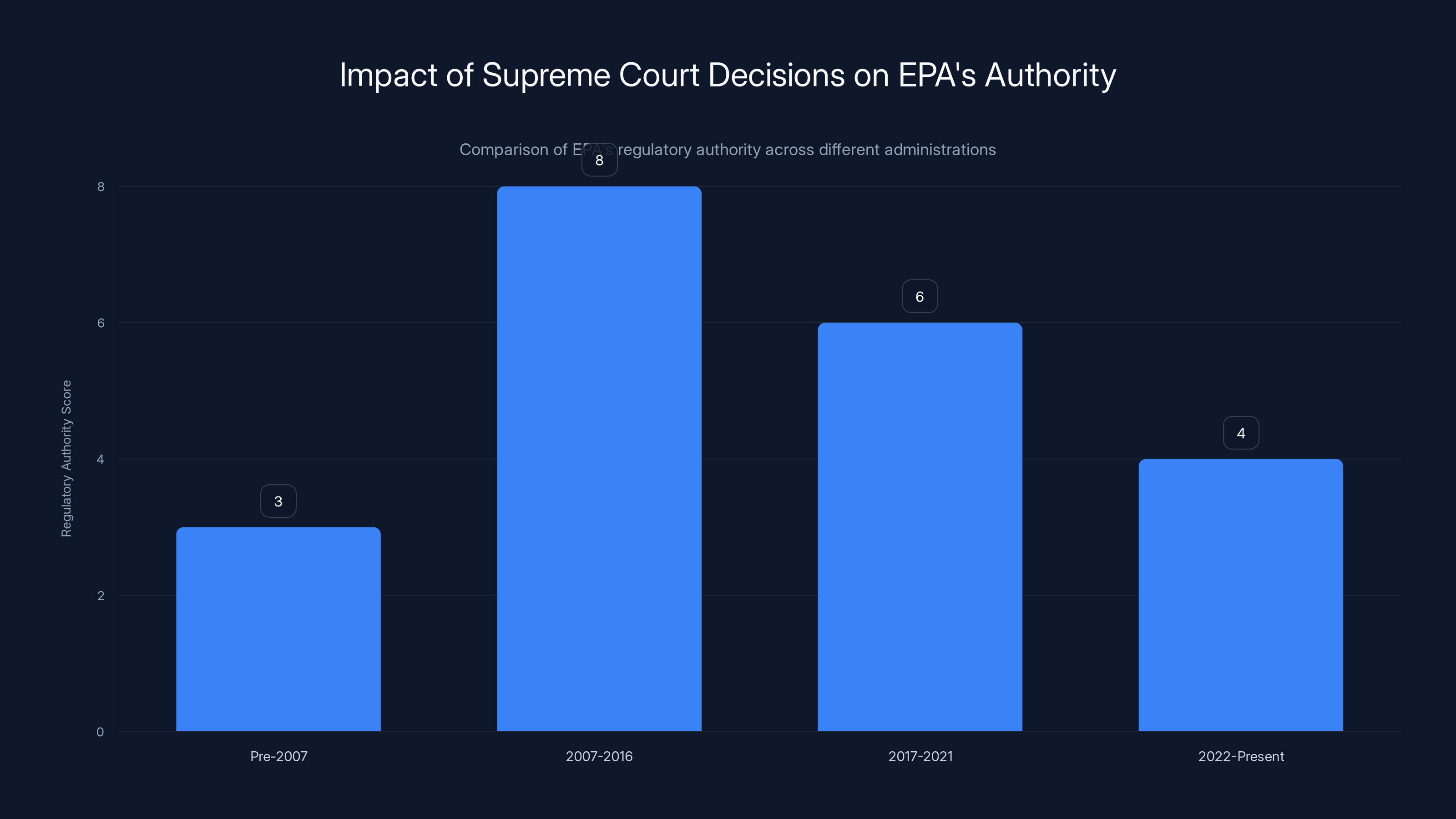

The EPA's regulatory authority peaked post-2007 with the endangerment finding, but has faced challenges due to legal and political shifts, particularly with the major questions doctrine. (Estimated data)

The Obama Administration Completes the Endangerment Finding

When the Obama administration took over in 2009, they faced a clear directive from the Supreme Court: either regulate greenhouse gases or provide scientific evidence for why you shouldn't.

The EPA created an exhaustive endangerment finding. It reviewed thousands of scientific studies. It examined climate models from multiple independent institutions. It assessed the risks to public health from heat waves, air quality degradation, water availability, and ecosystem disruption. The document was voluminous, peer-reviewed, and scientifically rigorous.

The conclusion was unambiguous: greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare.

With this finding in place, the EPA could now move forward with regulations. Cars would need to meet stricter fuel economy standards. Power plants would face limits on carbon pollution. Oil and gas facilities would need to control methane emissions.

But here's where things got complicated. Even with a clean legal mandate and a solid scientific foundation, these regulations faced intense opposition in courts and Congress. Fossil fuel companies sued. Republican states sued. The regulations faced constant legal challenges, and with a Republican majority on the Supreme Court, many of those challenges succeeded in slowing implementation or weakening rules.

Still, the endangerment finding stood. It was the legal foundation. As long as it existed, the EPA theoretically had to regulate greenhouse gases. The administration could debate the extent of regulation, but the basic fact—that greenhouse gases require regulation—was supposedly settled law.

That's what's being overturned now.

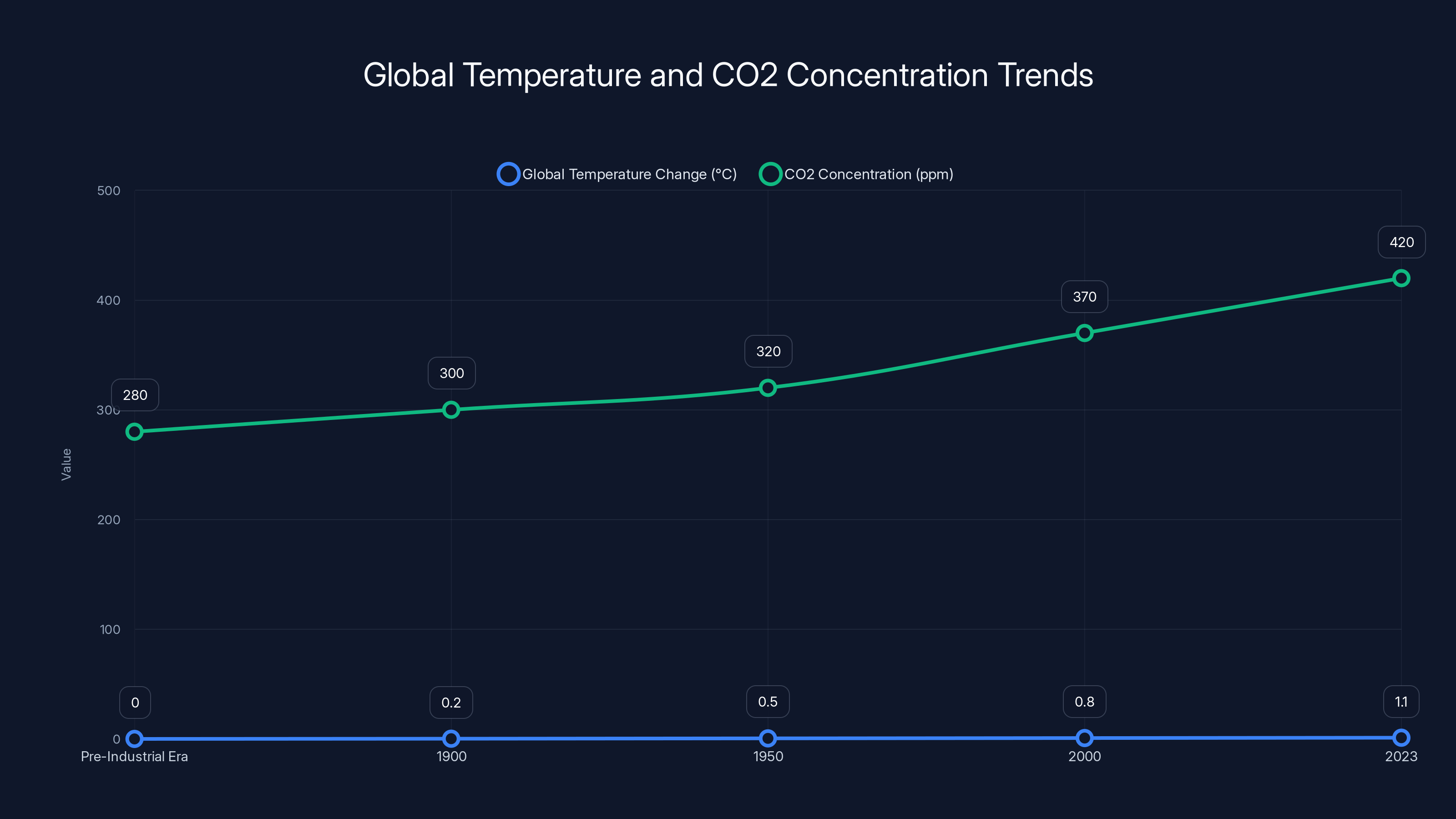

The chart illustrates the clear upward trend in global temperatures and CO2 levels since the pre-industrial era, highlighting the significant impact of human activities. Estimated data based on historical trends.

The First Trump Administration's Calculated Retreat

When Trump took office in 2017, his administration faced a choice: attack the endangerment finding directly, or work around it.

Scott Pruitt, who became EPA administrator, wanted to attack it directly. He was an ideological opponent of the endangerment finding. But the decision was made to leave it in place. Why?

Because overturning a comprehensive scientific document while the science itself continued to get stronger would be politically and legally untenable. It would invite immediate lawsuits, and those lawsuits would probably succeed. The evidence for human-caused climate change was mounting, not weakening. Polar ice was melting. Global temperatures were rising. Extreme weather was becoming more common. Reversing a scientific finding in the face of mounting evidence would be almost impossible to defend in court.

So instead, the first Trump administration took a different approach: accept the endangerment finding on paper, but gut the regulations through other means. Weaken fuel economy standards. Delay implementation of power plant rules. Refuse to update methane standards. It was regulation through inaction and minimal enforcement.

For example, the Trump administration announced a rollback of Obama-era fuel economy standards, proposing that automakers only improve efficiency by about 1.5% per year instead of the 5% average under Obama. The endangerment finding remained on the books, but the actual regulations flowing from it were weakened significantly.

The Second Trump Administration's Bold Gambit

The second Trump administration is playing a different game. Instead of working around the endangerment finding, they're trying to eliminate it.

And crucially, they're not even bothering to hide their strategy. In the EPA's announcement revoking the endangerment finding, they're explicitly stating that they believe recent Supreme Court decisions have changed how the courts should interpret the Clean Air Act. They're betting that the current Supreme Court majority will overturn Massachusetts v. EPA if given the chance.

This is a calculated risk, but it's not an irrational one. The current Supreme Court has shown consistent skepticism toward environmental regulations. In the Dobbs decision, the Court overturned Roe v. Wade, which had been precedent for 50 years. The message was clear: no precedent is sacred if the current majority disagrees with it.

The Court has also issued a series of decisions limiting EPA authority. In West Virginia v. EPA (2022), the Court blocked the EPA's major climate rule for power plants, saying the agency had exceeded its authority. The Court applied what's called the "major questions doctrine," which says that when an agency tries to regulate something truly major, Congress must have explicitly authorized that action.

The Trump administration is betting that this same reasoning could be applied to the endangerment finding itself. They're arguing that using the endangerment finding to launch a sweeping regulatory regime is itself a "major question" that Congress never explicitly authorized.

It's a clever legal argument. Not necessarily a strong one, but clever. And with a 6-3 conservative majority on the Court, it has a non-negligible chance of success.

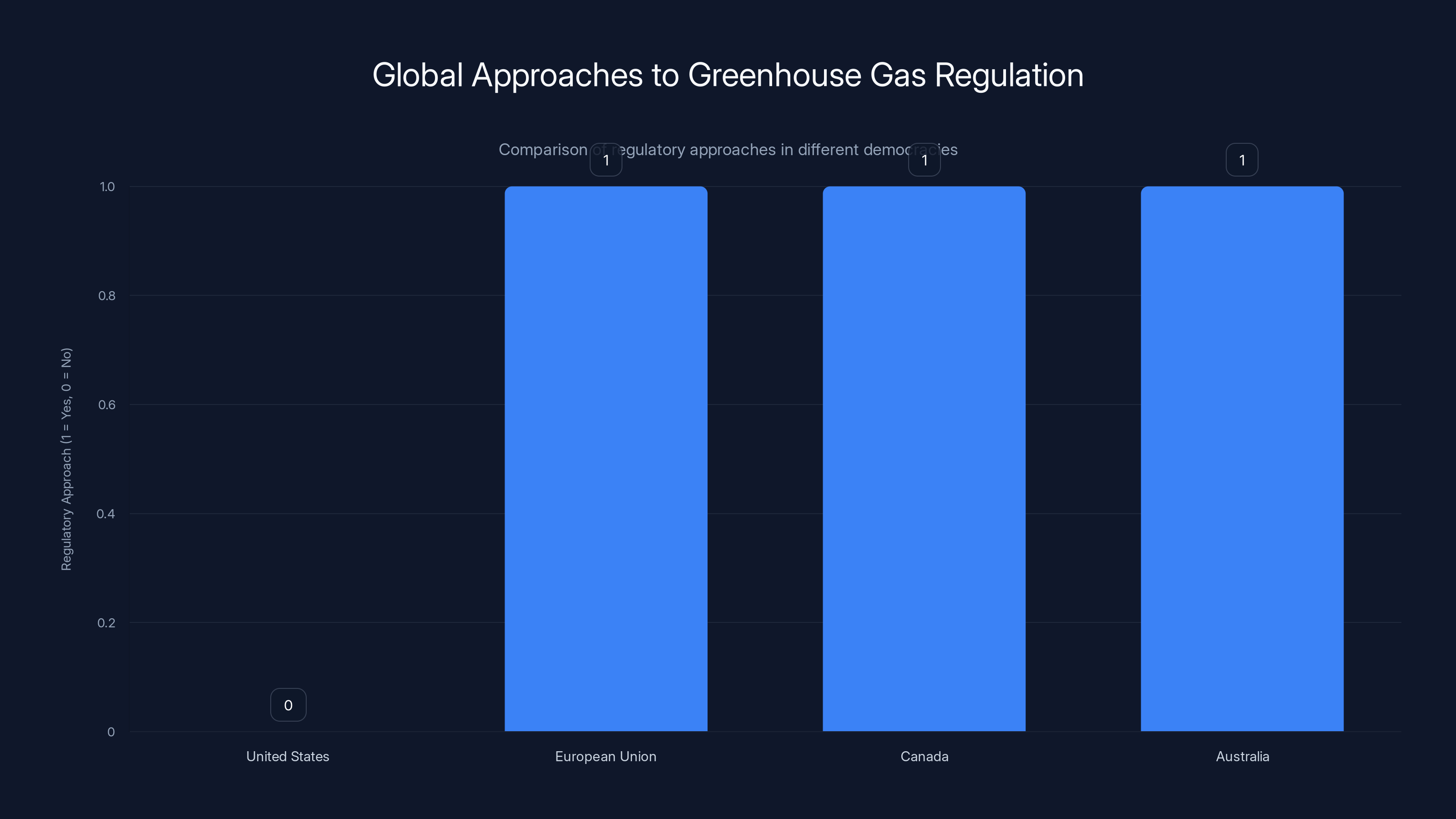

While the Trump administration questioned the EPA's authority to regulate greenhouse gases, other democracies like the EU, Canada, and Australia have implemented regulatory measures. Estimated data.

The Science Behind the Endangerment Finding: What the Data Actually Shows

Before we talk about the legal maneuvering, let's ground ourselves in what the endangerment finding actually says.

The endangerment finding is fundamentally a scientific document. It's not ideology. It's not environmental activism. It's the EPA laying out what the data shows about the risks of greenhouse gases.

Here's what that data demonstrates:

Temperature trends are unambiguous. Global average temperatures have risen approximately 1.1°C since the pre-industrial era. The last decade has been the warmest on record. The warming is not cyclical or natural. Multiple lines of evidence show that human activities, particularly the burning of fossil fuels, are the primary cause.

The atmosphere's CO2 concentration has surged. Atmospheric carbon dioxide has increased from about 280 parts per million in the pre-industrial era to over 420 ppm today. This increase correlates directly with industrialization and fossil fuel consumption. Ice core data shows that CO2 levels haven't been this high for over 800,000 years.

The mechanisms are well-understood. Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas. That's not debatable or controversial. When CO2 is released into the atmosphere, it traps heat that would otherwise escape to space. The physics of this phenomenon was understood by scientists in the 1850s. It's thermodynamics, not speculation.

Health impacts are measurable. Climate change causes real harm to human health. Heat waves kill thousands of people annually. Wildfires degrade air quality. Changing precipitation patterns affect water availability. Shifting climate zones allow disease vectors to expand their ranges. These aren't theoretical risks. They're happening now.

Economic costs are significant. The EPA's endangerment finding documents the economic costs of climate change. Extreme weather events cause billions in damage annually. Agricultural productivity is affected. Infrastructure is threatened by sea level rise and changing precipitation patterns. These costs are quantifiable and substantial.

The endangerment finding doesn't break new scientific ground. It synthesizes existing research. It reviews the consensus of climate scientists. And it reaches a conclusion that is effectively universal among climate scientists: greenhouse gases pose a measurable threat to human health and welfare.

This is why the first Trump administration didn't challenge the science head-on. The science is too strong. Too much evidence. Too many independent studies reaching the same conclusion.

The Trump Administration's Failed Attempt at a Counter-Report

Early in 2025, the Trump administration attempted to build a scientific case against the endangerment finding. They assembled a group of contrarian scientists to write a report questioning the evidence for human-caused climate change.

The effort was a disaster.

The contrarian report failed to gain any credibility within the scientific community. It cherry-picked data. It ignored inconvenient findings. It elevated discredited arguments that had been thoroughly debunked. Major scientific institutions, universities, and independent researchers quickly identified the report's flaws.

The Trump administration, realizing that a frontal assault on the science wasn't going to work, abandoned the scientific argument. They didn't try to convince Americans that the endangerment finding was scientifically wrong. Instead, they pivoted to a legal argument: that even if the science is sound, the EPA doesn't have the legal authority to regulate greenhouse gases based on it.

This is a more sophisticated strategy, but it's also more revealing. It concedes the scientific point. It essentially says: yes, greenhouse gases are dangerous, but we don't think the EPA should be the one regulating them.

That's a political argument, not a scientific one. And it's worth noting that other developed democracies have chosen differently. The European Union regulates greenhouse gases. Canada regulates them. Australia has carbon pricing. The question isn't whether democratic countries can choose to address climate change. The question is whether the U.S. EPA has the legal authority to do so under the Clean Air Act.

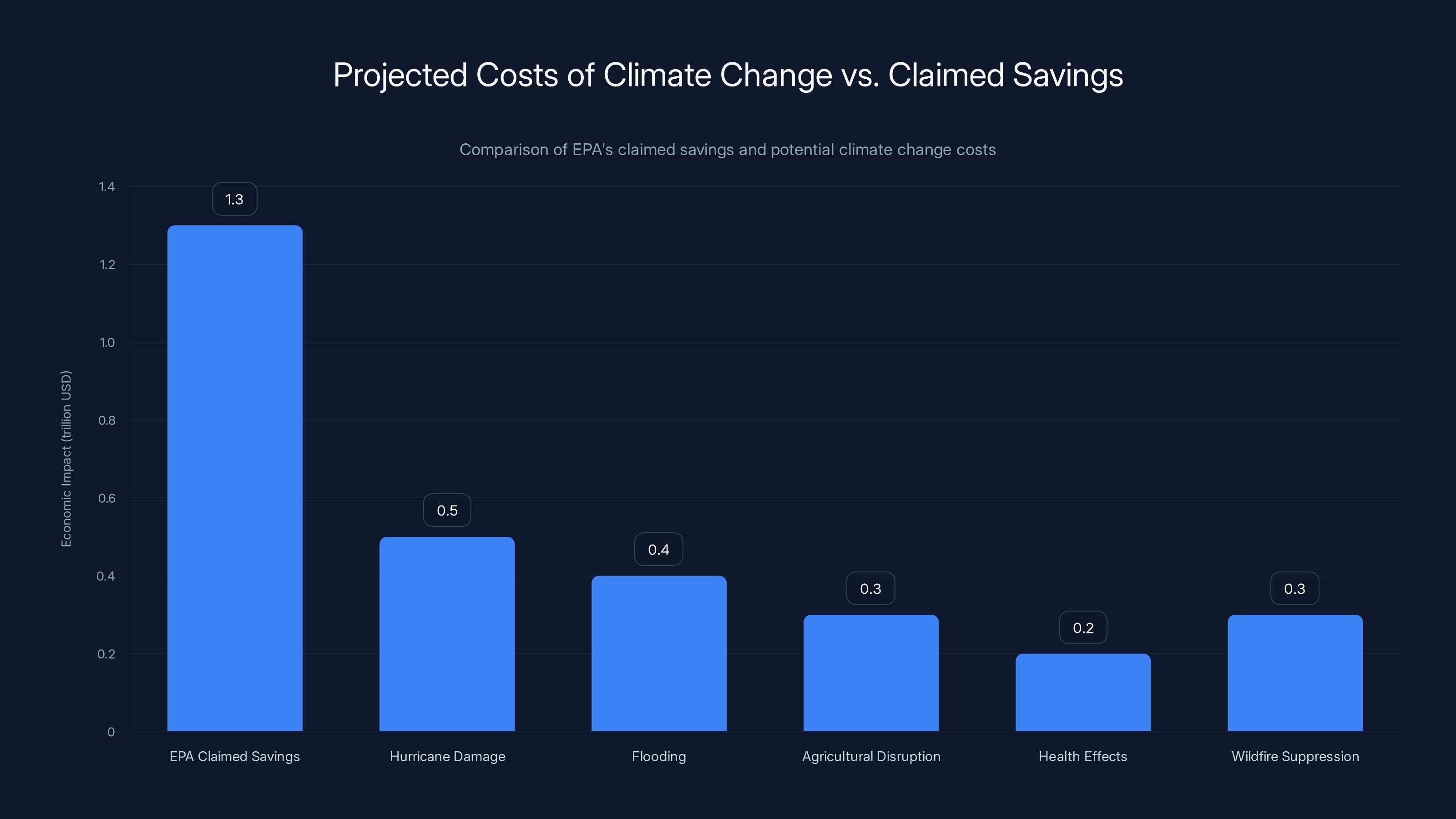

The EPA's claimed

The Legal Strategy: The "Major Questions Doctrine"

The Trump administration's legal argument rests on something called the "major questions doctrine." This is a principle that has been increasingly prominent in recent Supreme Court decisions.

The doctrine states that when an agency tries to regulate something that Congress would consider a "major question," the agency must have received explicit authorization from Congress to do so. You can't infer authorization. Congress has to clearly say that the agency can address this particular issue.

The Supreme Court applied this doctrine in West Virginia v. EPA. The Court said that using the Clean Air Act to impose major restrictions on how power plants generate electricity was such a significant decision that the EPA couldn't just rely on general language in the statute. Congress would need to have explicitly authorized the EPA to make that kind of major decision about the energy system.

The Trump EPA is now arguing that using the endangerment finding to launch a comprehensive regulatory regime for greenhouse gases across the entire economy is also a "major question." Congress, they argue, never explicitly authorized the EPA to undertake such sweeping regulation.

It's a logical extension of the West Virginia reasoning. If the courts accept the major questions doctrine as broadly as they've been applying it in recent decisions, then perhaps the endangerment finding itself represents a regulatory overreach.

But there's a problem with this argument. Congress did write the Clean Air Act in mandatory language. It says the EPA "shall" regulate air pollutants that endanger public health. Congress doesn't explicitly say greenhouse gases, but Congress also doesn't explicitly say ozone or particulate matter or nitrogen oxides. The law is written in general terms that apply to any air pollutant that meets the criteria.

The Supreme Court in Massachusetts v. EPA said that this general language is sufficient. The EPA has the authority to regulate anything that endangers public health under the Clean Air Act. You don't need special Congressional authorization for every specific pollutant.

So the legal argument comes down to this: does the major questions doctrine override the plain language of the Clean Air Act? Can a Supreme Court majority overrule a previous Supreme Court decision based on a doctrine that's only been recently emphasized?

The answer is: maybe. This Court has shown willingness to overturn precedent (Dobbs) and to apply new doctrines restrictively to agency authority (major questions). A 6-3 conservative majority could potentially say that Massachusetts v. EPA was wrongly decided.

The Cost-Benefit Analysis: How the EPA Justifies This Decision

The EPA's announcement revoking the endangerment finding includes some dubious economic claims. The agency claims that eliminating the endangerment finding will save $1.3 trillion in costs.

Where does this number come from? Primarily from the fuel economy standards for cars and the coal power plant rules—regulations that the EPA had already effectively eliminated or weakened in Trump's first term.

Here's the thing: the EPA is counting savings from regulations that aren't actually being enforced. They're claiming that by revoking the endangerment finding, they're saving money that these regulations would have cost. But the regulations are already dead or dying. Trump's EPA has already rolled back fuel economy standards. Trump's EPA has already delayed and weakened power plant rules.

So the $1.3 trillion number is largely fictional. It's savings from regulations that either don't exist or that Trump's EPA is already refusing to enforce.

Moreover, the EPA completely omitted the costs of not regulating greenhouse gases. If climate change continues unabated, what's the cost to the American economy? Increased hurricane damage. Flooding in coastal cities. Agricultural disruption. Heat-related health effects. Wildfire suppression. Infrastructure damage from more extreme weather.

The economic costs of climate change are substantial. The Trump EPA simply ignored them. They calculated costs on one side (from regulations that mostly don't exist) and benefits on the other side (from no regulations), and claimed that this omission meant the decision was economically justified.

It's not serious economic analysis. But it's the argument the EPA is making.

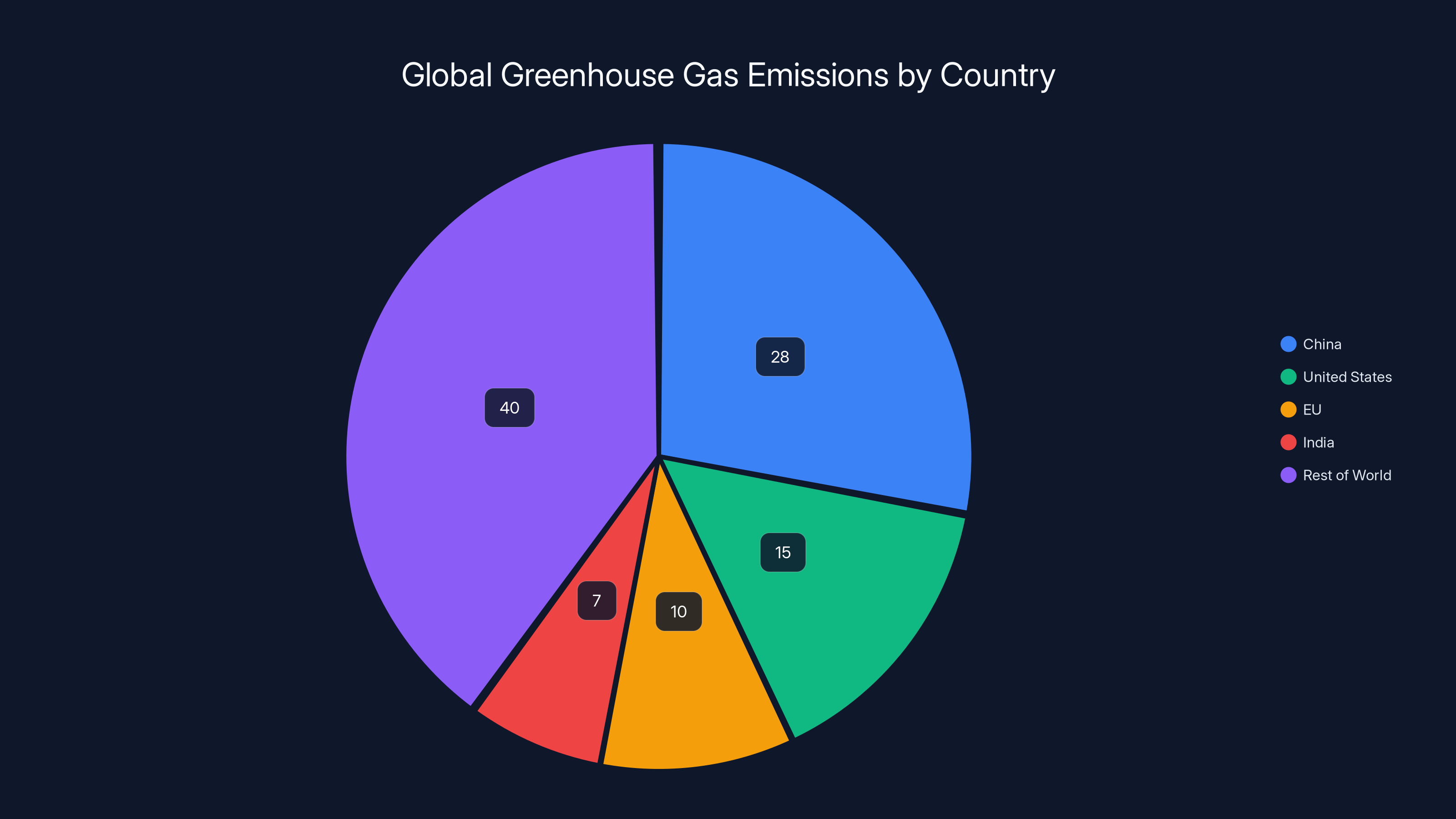

China leads in global greenhouse gas emissions, followed by the U.S. and EU. The U.S. decision to revoke its endangerment finding could impact international climate policies. (Estimated data)

Environmental Groups Immediately File Suit

Before the ink was dry on the EPA's announcement, environmental groups were filing lawsuits challenging the decision.

The legal arguments are clear. The endangerment finding is a scientific document. The EPA can't just vote that scientific findings are wrong. If the agency believes the finding is incorrect, they need to provide scientific evidence for why.

The EPA hasn't done that. They've only provided a legal argument that Congress didn't authorize the EPA to regulate greenhouse gases, even if they are dangerous.

Environmental lawyers argue that this reversal violates the Administrative Procedure Act, which requires agencies to follow rational procedures when making decisions and to base those decisions on the facts of the case.

Revoking a scientific finding without providing scientific evidence to contradict it isn't rational decision-making. It's politics disguised as policy.

These lawsuits will likely reach the Supreme Court. And when they do, the Court will face a choice: does the major questions doctrine override the mandatory language of the Clean Air Act and the 2007 precedent?

What Happens to Current Regulations If the Endangerment Finding Is Overturned

This is where things get complicated. Revoking the endangerment finding doesn't instantly eliminate all climate regulations.

Fuel economy standards can exist without the endangerment finding. They can be justified under different legal theories. Similarly, some regulations for power plants might survive under different rationales.

But the endangerment finding serves as the foundation. Removing it weakens every regulation that rests on it. It opens the door for legal challenges to these regulations. It's one thing for a regulation to exist when the EPA has found that the regulated substance endangers public health. It's another thing entirely if the EPA has revoked that finding.

Companies and states can now sue, arguing that particular regulations are unlawful because they're based on an endangerment finding the EPA no longer accepts.

So the revocation has a cascading effect. It doesn't immediately erase regulations, but it puts them all at legal risk.

The Supreme Court's Anti-Regulation Trajectory

To understand why the Trump administration is making this gamble, you need to look at the Supreme Court's recent decisions on agency authority.

The Court has consistently been skeptical of broad agency power. In multiple decisions, conservative justices have argued that agencies are overstepping their authority. Justice Gorsuch, in particular, has suggested that current administrative law doctrine gives agencies too much deference.

The major questions doctrine is the Court's way of reining in agency power. When something big is at stake, the Court is saying, Congress needs to make the decision, not an unelected agency.

Climate regulation certainly qualifies as a "big" decision. It affects the economy. It affects how companies operate. It affects energy policy across the country.

So the Trump administration is betting that when a case challenging the endangerment finding reaches the Supreme Court, the majority will say: Massachusetts v. EPA was wrongly decided. Congress never authorized the EPA to use the Clean Air Act as a general climate regulation tool. The endangerment finding is null and void.

It's a gamble, but it's not reckless. The Court's current trajectory suggests that a majority is open to limiting agency power in precisely this way.

International Implications: What This Means for Global Climate Policy

America's decision to revoke its endangerment finding doesn't happen in a vacuum. The U.S. is responsible for a significant portion of global greenhouse gas emissions, though not the majority. China emits more in absolute terms, but the U.S. still drives substantial emissions and sets technological standards that other countries follow.

Other nations are watching this decision closely. Some will see it as validation for their own climate skepticism. Others will view it as a step backward and an opportunity to position themselves as climate leaders.

The EU has already suggested that if the U.S. continues down this path, it might impose carbon border adjustment tariffs on American goods. These are tariffs designed to protect European companies from competition with American companies that don't face carbon costs.

It's a trade threat. And it's a real one. The EU is serious about carbon pricing and about preventing carbon leakage to countries with weaker regulations.

So the Trump administration's decision to revoke the endangerment finding has international consequences. It could provoke trade tensions. It could isolate the U.S. on climate issues at a time when American leadership on technology and emissions reduction has been a significant advantage.

The Road Ahead: Litigation and Uncertainty

Here's what's likely to happen in the coming months and years:

- Environmental groups will challenge the revocation in federal court.

- The case will likely reach the Supreme Court.

- The Supreme Court will decide whether the endangerment finding is legally valid.

- Depending on the decision, regulations will either stand or fall.

But this uncertainty is itself a problem. Companies need to know what rules they have to follow. If regulations might be overturned at any moment, it's harder to invest in compliance technology. Automakers, power plant operators, and industrial facilities are in a holding pattern.

This is exactly what the Trump administration wants, in a way. It creates legal uncertainty that discourages companies from investing in clean technology or emissions reductions. Why spend billions on new technology if the regulations requiring that technology might disappear?

But it also creates business uncertainty that many companies dislike. Some major corporations have taken positions supporting climate action because they believe long-term regulatory certainty is better than political whiplash.

Alternative Regulatory Paths Forward

Even if the endangerment finding is revoked, there are other ways to regulate greenhouse gases.

Congress could pass climate legislation. It hasn't done so successfully in recent years, but it's not impossible. A bipartisan group of senators has periodically considered climate bills.

States could impose their own greenhouse gas regulations. Several states have already done this. California has its own emissions standards. New York has its own regulations. If the federal government steps back, states might step forward.

International agreements could create incentives for emissions reduction. The U.S. could participate in carbon pricing with other countries. It could agree to emissions targets that are enforced through trade mechanisms.

Corporations could voluntarily adopt emissions reduction targets. Some major companies have already done this. It's not as effective as regulation, but it's not nothing.

But the most direct path—using the Clean Air Act to regulate greenhouse gases based on a clear endangerment finding—is the path the Trump administration is attempting to close.

The Bigger Question: Can Science Survive Politics

Ultimately, the EPA's decision to revoke the endangerment finding raises a deeper question about the role of science in policy-making.

The endangerment finding is fundamentally a scientific document. It's based on evidence. It's peer-reviewed. It reflects the consensus of climate scientists.

Can a federal agency revoke a scientific finding for political reasons? Can the EPA say that they no longer accept a scientific conclusion that the entire scientific community still accepts?

This is a governance question that goes beyond climate policy. If agencies can revoke scientific findings based on political pressure, then scientific evidence becomes a tool of politics rather than a guide for policy.

The courts will ultimately decide whether the EPA can take this step. But the decision has implications that extend far beyond climate regulation.

FAQ

What is the endangerment finding and why does it matter?

The endangerment finding is an EPA determination, mandated by the 2007 Supreme Court decision in Massachusetts v. EPA, that greenhouse gases pose a threat to human health and welfare. It serves as the legal foundation for all federal regulations of greenhouse gas emissions from cars, power plants, and industrial sources. Without it, the EPA's authority to regulate greenhouse gases becomes legally questionable, even if the science showing they're harmful remains unchanged.

Why did the Trump administration revoke the endangerment finding now instead of in the first term?

In Trump's first term (2017-2021), the administration chose to leave the endangerment finding in place while weakening regulations through other means, believing that overthrowing a scientific document would be too legally vulnerable. However, the current Supreme Court has demonstrated greater willingness to limit agency authority through the "major questions doctrine." The Trump administration is betting that this reshaped Court majority will overturn the Massachusetts v. EPA precedent if given the chance, making the revocation a strategic legal gamble rather than a purely scientific one.

What is the "major questions doctrine" and how does it apply here?

The major questions doctrine is a legal principle stating that when agencies attempt to regulate matters of major economic or political significance, Congress must explicitly authorize such regulation rather than the agency merely inferring authority from general statutory language. The Trump EPA argues that using the endangerment finding to regulate greenhouse gases economy-wide represents such a major question that Congress must have explicitly authorized it, which it didn't. This doctrine was emphasized in the Supreme Court's 2022 decision West Virginia v. EPA, blocking a major EPA carbon rule for power plants.

What are the economic claims the EPA is making about this decision?

The EPA claims the decision will generate $1.3 trillion in savings, primarily by eliminating costs from fuel economy standards and coal power plant regulations. However, these figures are controversial because Trump's EPA had already weakened or eliminated many of these regulations in the first term, so the "savings" are largely from rules that aren't currently being enforced. The EPA also completely omitted calculating the economic costs of unregulated climate change, including damage from extreme weather, agricultural disruption, and health effects, making the cost-benefit analysis incomplete.

What happens to existing climate regulations if the endangerment finding is revoked?

Technically, existing regulations don't immediately disappear, but their legal foundation is severely weakened. Companies and states can now sue to overturn individual regulations, arguing they're based on a finding the EPA no longer accepts. This creates cascading legal jeopardy for fuel economy standards, power plant rules, methane regulations, and other climate-related policies. The regulations become vulnerable to being struck down one by one through litigation rather than being formally rescinded all at once.

How likely is it that the Supreme Court will overturn Massachusetts v. EPA?

With a 6-3 conservative majority on the Supreme Court, there's a realistic possibility, though not a certainty. The Court has shown willingness to overturn precedent (as in Dobbs v. Jackson) and has consistently limited agency authority in recent decisions. However, overturning a foundational environmental law decision would be a dramatic step that some justices might be reluctant to take. The outcome depends on how the specific legal arguments are framed and which justices participate in the decision.

What scientific evidence does the EPA provide to support revoking the endangerment finding?

The EPA provides no scientific evidence to contradict the endangerment finding. Instead, they rely entirely on legal arguments that the EPA exceeded its authority. This is significant because it concedes that the science supporting the endangerment finding remains sound. The EPA essentially argues: "Yes, greenhouse gases are dangerous, but we don't have the legal authority to regulate them under the Clean Air Act." This is a political and legal argument, not a scientific one.

How are environmental groups challenging this decision?

Environmental groups have filed lawsuits arguing that the EPA violated the Administrative Procedure Act by revoking a scientific finding without providing scientific evidence to contradict it. They argue that revoking the endangerment finding is arbitrary and capricious decision-making that isn't grounded in fact or reason. These cases will likely reach the Supreme Court, where the Justices will ultimately decide whether the EPA's legal arguments override the statutory language of the Clean Air Act and prior precedent.

What international consequences might result from revoking the endangerment finding?

The European Union has indicated it might impose carbon border adjustment tariffs on American goods if the U.S. fails to maintain carbon pricing or emissions standards. Other countries may use the U.S. decision as justification for their own climate skepticism, or alternatively, they may position themselves as climate leaders while the U.S. steps back. This could affect America's geopolitical standing and its ability to influence global climate policy, particularly as other nations invest heavily in clean technology and emissions reduction.

Could Congress pass legislation to override this EPA decision?

Yes, Congress could pass legislation explicitly authorizing the EPA to regulate greenhouse gases and requiring the agencies to maintain an endangerment finding or equivalent authority. However, such legislation would likely require bipartisan support to overcome a presidential veto or to pass with sufficient majorities. Given the current political climate and Republican skepticism of climate regulation, passage of such legislation is unlikely in the near term, though not impossible if political circumstances shift.

What alternatives exist for regulating greenhouse gases if the endangerment finding is overturned?

Several alternatives could partially replace federal EPA authority: states could impose their own stricter emissions standards (California, New York, and other states already have); Congress could pass climate legislation; international agreements could create incentives for emissions reduction through trade mechanisms; and corporations could voluntarily adopt emissions reduction targets. However, none of these alternatives would provide the comprehensive, uniform regulatory framework that federal EPA authority enables, so a complete overturn of the endangerment finding would leave significant regulatory gaps.

Key Takeaways

- The Trump EPA revoked the endangerment finding that legally mandates regulation of greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act

- The administration is betting the Supreme Court will overturn the 2007 Massachusetts v. EPA precedent using the major questions doctrine

- The EPA provides no scientific evidence to contradict the endangerment finding; they rely entirely on legal arguments

- Revoking the endangerment finding weakens the legal foundation for fuel economy standards, power plant emissions rules, and methane regulations

- A 6-3 conservative Supreme Court majority with recent skepticism toward EPA authority makes this legal gamble realistic but uncertain

Related Articles

- EPA Clean Air Act Endangerment Finding Repeal: Impact & Implications [2025]

- Trump's EPA Kills Greenhouse Gas Regulations: What It Means [2025]

- DOE Climate Working Group Ruled Illegal: What the Judge's Decision Means [2025]

- EPA Revokes Climate Endangerment Finding: What Happens Next [2025]

- The Endangerment Finding Battle: US Climate Rules Uncertainty [2025]

- US Offshore Wind Court Orders: Construction Restart [2025]

![EPA Revokes Greenhouse Gas Endangerment Finding: What It Means for Climate Policy [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/epa-revokes-greenhouse-gas-endangerment-finding-what-it-mean/image-1-1770932135208.jpg)