DOE Climate Working Group Ruled Illegal: What the Judge's Decision Means

Last month, a federal judge handed down a decision that might seem like arcane administrative law, but it actually cuts to the heart of how governments can—and cannot—operate when scientific evidence contradicts their policy goals. The ruling? The Department of Energy's Climate Working Group violated federal law.

Here's what you need to know: A panel of government-selected climate contrarians was assembled to produce a report that would undermine the scientific rationale for the EPA's greenhouse gas regulations. The group operated almost entirely in secret, with members using personal email accounts to avoid public scrutiny. When environmental groups sued under the Federal Advisory Committee Act, the government first claimed the law didn't apply, then argued the problem was moot because they'd disbanded the group.

The judge wasn't buying it. And in a decision that could have real consequences for how the government approaches climate policy, she ruled that the violations were established as a matter of law—regardless of whether the group still technically existed.

But here's what's genuinely important: the court forced the government to release all the group's communications. Those emails are now public. And they reveal something far more troubling than sloppy compliance with advisory committee rules. They show a deliberate effort to manufacture scientific doubt about climate change specifically to undercut EPA regulations.

This article breaks down what actually happened, why the legal ruling matters, what the leaked emails reveal about the government's strategy, and what comes next for climate regulation in America.

TL; DR

- Legal Violation: A federal judge ruled the Department of Energy's Climate Working Group violated the Federal Advisory Committee Act by operating in secret, cherry-picking biased members, and refusing to keep public records. This was highlighted in a Spokesman article.

- The Real Goal: Emails reveal the group was specifically designed to produce a report that would give cover for dismantling the EPA's endangerment finding—the scientific foundation of all federal climate regulations. This was reported by France24.

- Secret Communications: Members were instructed to use private email accounts to avoid public scrutiny, but the court ordered full disclosure during the lawsuit, as noted by Union of Concerned Scientists.

- Mainstream Science Rejected: The group dismissed criticism from DOE staff and mainstream climate scientists as "hopelessly biased," while claiming their fringe positions represented legitimate scientific debate. This was detailed in E&E News.

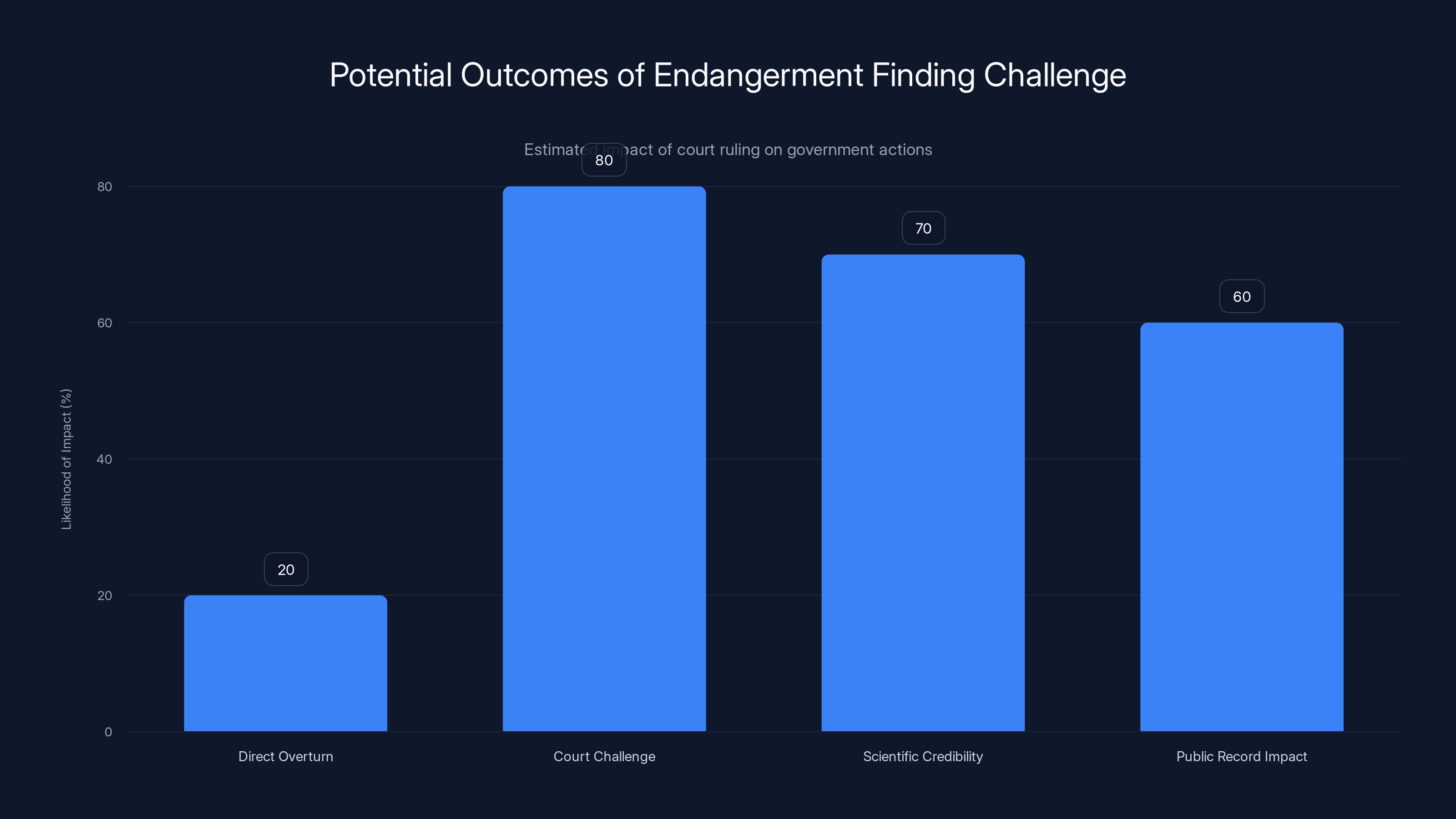

- Current Status: The government's attempt to overturn the endangerment finding is reportedly on hold due to weak scientific case, but this ruling may play a significant role if the matter reaches court, as discussed in Resources for the Future.

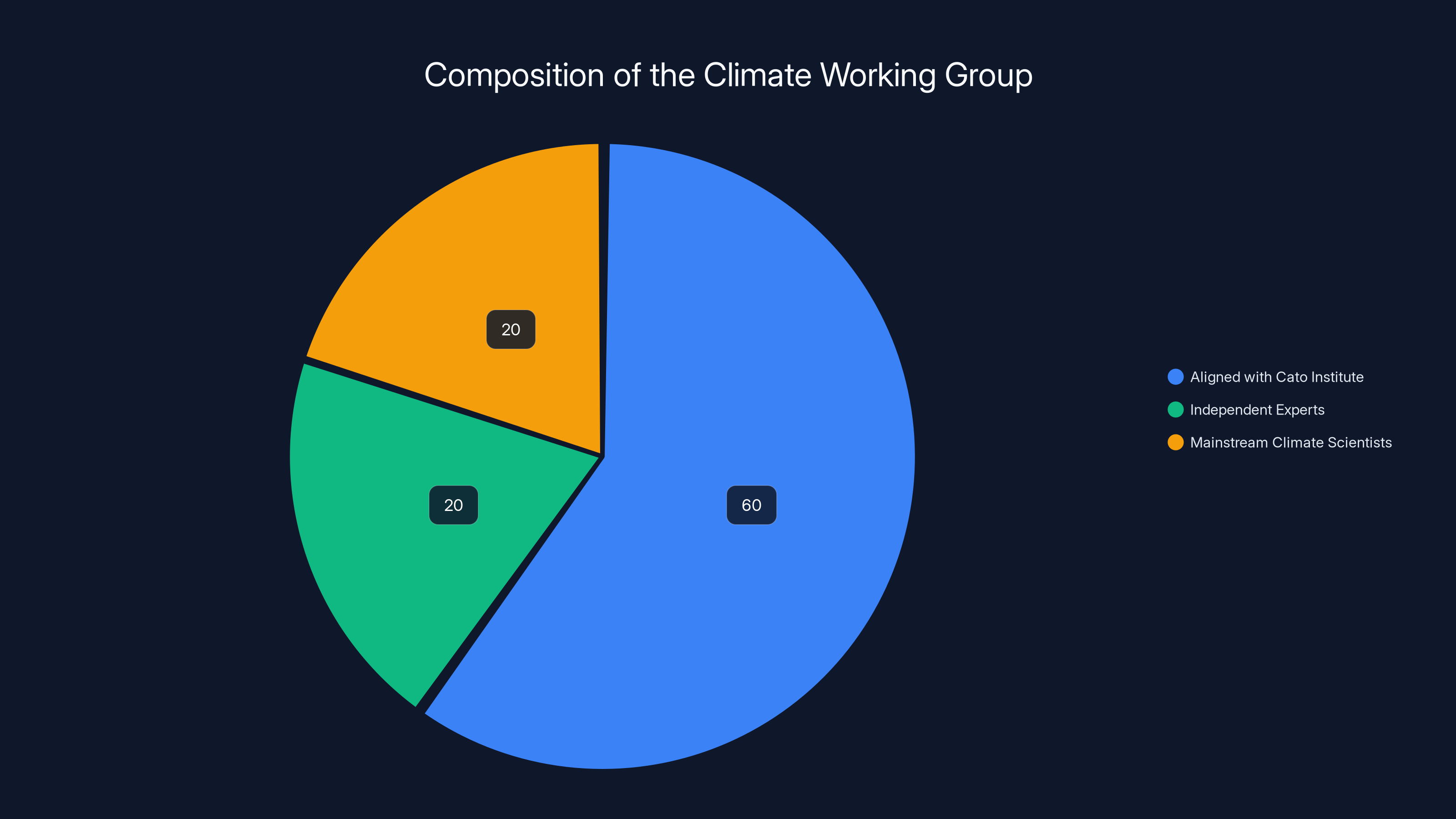

Estimated data shows equal distribution of tactics used in manufacturing doubt, highlighting a strategic approach to creating controversy.

The Scientific Foundation: The Endangerment Finding That Started It All

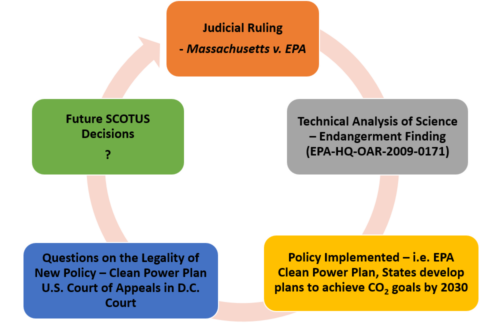

To understand why this lawsuit and this ruling matter, you need to go back to 2009 and a Supreme Court decision that changed everything about how the federal government approaches climate change regulation.

In Massachusetts v. EPA, the Supreme Court ruled that the Environmental Protection Agency had authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate greenhouse gases—but only if the EPA made a finding that these gases pose a danger to public health. This decision flipped the burden: the EPA couldn't just ignore climate science. It had to actively evaluate the evidence and make a formal determination about whether CO2 and other greenhouse gases represent a threat to Americans.

The Obama administration took that seriously. The EPA assembled the best available evidence from climate scientists, public health experts, and peer-reviewed research. In 2009, the agency issued an endangerment finding: yes, greenhouse gases do pose a risk to public health and welfare. This wasn't controversial in scientific circles. Every major scientific body—the National Academy of Sciences, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the American Meteorological Society—had reached the same conclusion years earlier.

With that endangerment finding in place, the EPA gained the legal authority to set emission standards under the Clean Air Act. This led to regulations like the power plant carbon standards (later rolled back, then partially restored) and vehicle emission standards. The endangerment finding wasn't just policy—it was the legal foundation for all federal climate regulation.

Here's the thing: even during the first Trump administration, when the political goal was clearly to roll back climate regulations, the scientific case for the endangerment finding was so airtight that nobody even tried to challenge it directly. They worked around it. They delayed. They used other legal theories. But they didn't try to overturn the finding itself.

The second Trump administration apparently decided that being subtle was a waste of time. Instead, they'd go after the finding directly. Which meant they needed something that looked like a credible scientific challenge to decades of peer-reviewed research.

Enter the Climate Working Group.

This chart estimates the distribution of factors influencing government decision-making, highlighting the importance of evidence-based decisions over political goals. Estimated data.

The Climate Working Group: Manufacturing Doubt on Purpose

In early 2025, the Department of Energy formed something called the Climate Working Group. On the surface, it looked reasonable: a group of scientists and technical experts assembled to review the scientific basis for the EPA's regulations and the endangerment finding. Nothing wrong with that, right? Second opinions are good. Scrutiny of regulations is normal.

But as the lawsuit documents and the released emails make clear, this group was never designed as a genuine scientific review. It was designed as a weapon.

The group was organized by a political appointee at the DOE—someone with previous ties to the libertarian Cato Institute. According to the released communications, the explicit purpose was to produce a report that would be useful in overturning the endangerment finding. Not to evaluate whether the endangerment finding was correct. Not to conduct an independent analysis. But to produce ammunition against EPA regulations.

To do this, the organizers needed people whose opinions were already aligned with that goal. They weren't looking for a balanced group of experts who might be convinced one way or another by evidence. They were looking for people who already believed—or at least were willing to argue—that current climate science was wrong or exaggerated.

This is important: there's a massive difference between "let's assemble experts who have different views on climate policy" and "let's find people willing to argue that the scientific consensus is wrong." The first is legitimate. The second is not.

The emails show that the group members themselves understood this distinction. They recognized that their views were outside the scientific mainstream. Rather than seeing this as a problem, they interpreted it as evidence that the mainstream was corrupt. In their communications, they described mainstream climate scientists as "hopelessly biased" and frequently attributed this alleged bias to the scientists' political views rather than to evidence.

This is a classic pattern in doubt manufacture: if the experts disagree with you, it's not because your evidence is weak. It's because they're biased. They're political. They're corrupt. Mainstream science becomes, by definition, wrong science.

There was some discussion within the group about getting their report peer-reviewed. An executive order required that significant science used in federal decisions be subject to peer review as part of achieving "gold standard science." So the group talked about peer review. But their approach was telling: they focused on identifying peer reviewers who already shared their views and would give the report a favorable reading.

In other words, they understood that outside experts would tear the report apart—so they looked for reviewers who wouldn't.

The Federal Advisory Committee Act Violation: Secrecy by Design

All of this brings us to the legal claim: violation of the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA).

FACA sounds dry and bureaucratic, but it exists for a reason. Passed in 1972, it requires that any group convened to provide advice to the federal government must operate under certain rules. These rules are straightforward:

The group must be balanced. You can't stack it with people who share a predetermined conclusion.

Meetings must be open to the public. Decisions made on behalf of the government shouldn't happen in private.

Records must be kept and made available. Transparency is the whole point.

The Climate Working Group violated all three requirements. And not by accident.

The group didn't hold public meetings. In fact, it apparently tried very hard to avoid any public transparency. The most damaging evidence? Group members were explicitly advised to use private email accounts rather than government email when communicating about the group's work. Why? To limit the ability of the public to obtain and review those communications under the Freedom of Information Act.

This wasn't careless. It was deliberate. Group members were essentially told: don't leave a paper trail the public can see.

When the Environmental Defense Fund and the Union of Concerned Scientists filed their lawsuit, they alleged FACA violations. The government's legal response was interesting. First, they claimed FACA didn't apply at all—that the Climate Working Group was just an information-gathering exercise, not a formal advisory committee.

But in court, when the judge started pressing on that question, the government's position shifted. They abandoned the "FACA doesn't apply" argument and instead insisted that the whole thing was moot because the government had already disbanded the group. Since the group no longer existed, the government argued, there was nothing to litigate.

The judge saw through this. In her ruling, she pointed out that the government was essentially ignoring the allegations of FACA violations and trying to hide behind the claim that the problems had been solved by dissolving the group. But you can't make a legal violation disappear by ending the thing that caused the violation. If you violated the law in forming an advisory committee, that violation happened. The fact that you later disbanded the committee doesn't erase it.

Moreover—and this is crucial—the judge noted that because the government was compelled to produce all the Climate Working Group's communications as part of the lawsuit discovery process, the FACA violation had essentially been remedied. The secret communications were now public. That's what FACA was designed to ensure: transparency. The lawsuit had achieved it.

As the judge stated: "These violations are now established as a matter of law."

Fossil fuel companies and utilities are estimated to gain the most from delaying climate regulations, benefiting significantly from the creation of climate doubt. Estimated data.

What the Leaked Emails Actually Reveal

The court ruling is important. The legal violation matters. But the emails are the real story.

When the government was forced to disclose all the Climate Working Group's communications—including messages sent to private email accounts—it revealed something damning about the entire enterprise. These weren't discussions among scientists honestly grappling with evidence. These were discussions among people who had been assembled for a specific political purpose and who were working backward from that purpose.

The emails show that the group was organized by a political appointee specifically to produce material that would aid the EPA in overturning the endangerment finding. That's not neutral. That's not balanced. That's not how scientific advisory processes are supposed to work.

The group recognized that their positions were outside the mainstream. But rather than taking that as evidence they should reevaluate, they took it as evidence that the mainstream was corrupt. They explicitly discussed the idea that mainstream climate scientists were "hopelessly biased" and attributed this to political motivations.

This is where the manufactured doubt strategy becomes clear. If experts disagree with your predetermined conclusion, the problem isn't your conclusion. The problem is that experts are biased. They're political. They're in it for funding or ideology, not evidence.

There was discussion of peer review, but it was revealing. The group wanted their report peer-reviewed—because an executive order required it—but they weren't interested in genuine peer review. They wanted reviewers who would approve of their findings. The emails show they were thinking about which scientists shared their views and would therefore give favorable reviews.

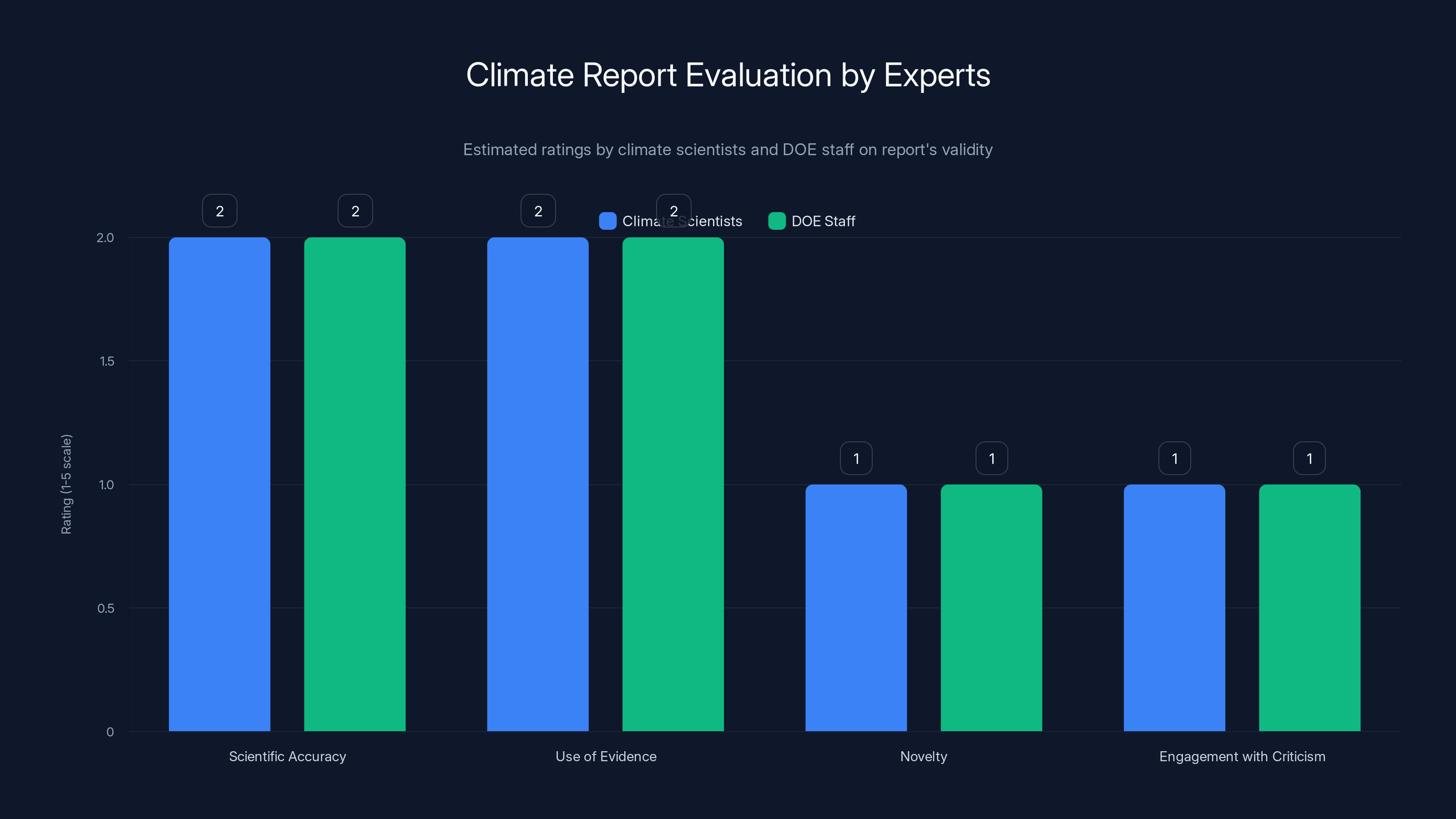

When DOE staff members actually reviewed the document, they identified many of the same flaws that the broader scientific community would later point out. The Climate Working Group largely ignored these internal critiques. When career scientists working for the Department of Energy said "this doesn't match the evidence," the answer wasn't to revise the report. It was to dismiss the critics as biased.

What's particularly telling is that the group seemed to understand that if they subjected their work to genuine scrutiny from outside experts, it would be torn apart. So they didn't. They built a process designed to ensure that their work would only be seen by people who already agreed with them.

This is the opposite of how science works. It's the opposite of how government advisory committees are supposed to work. And the emails prove it wasn't accidental. It was the plan.

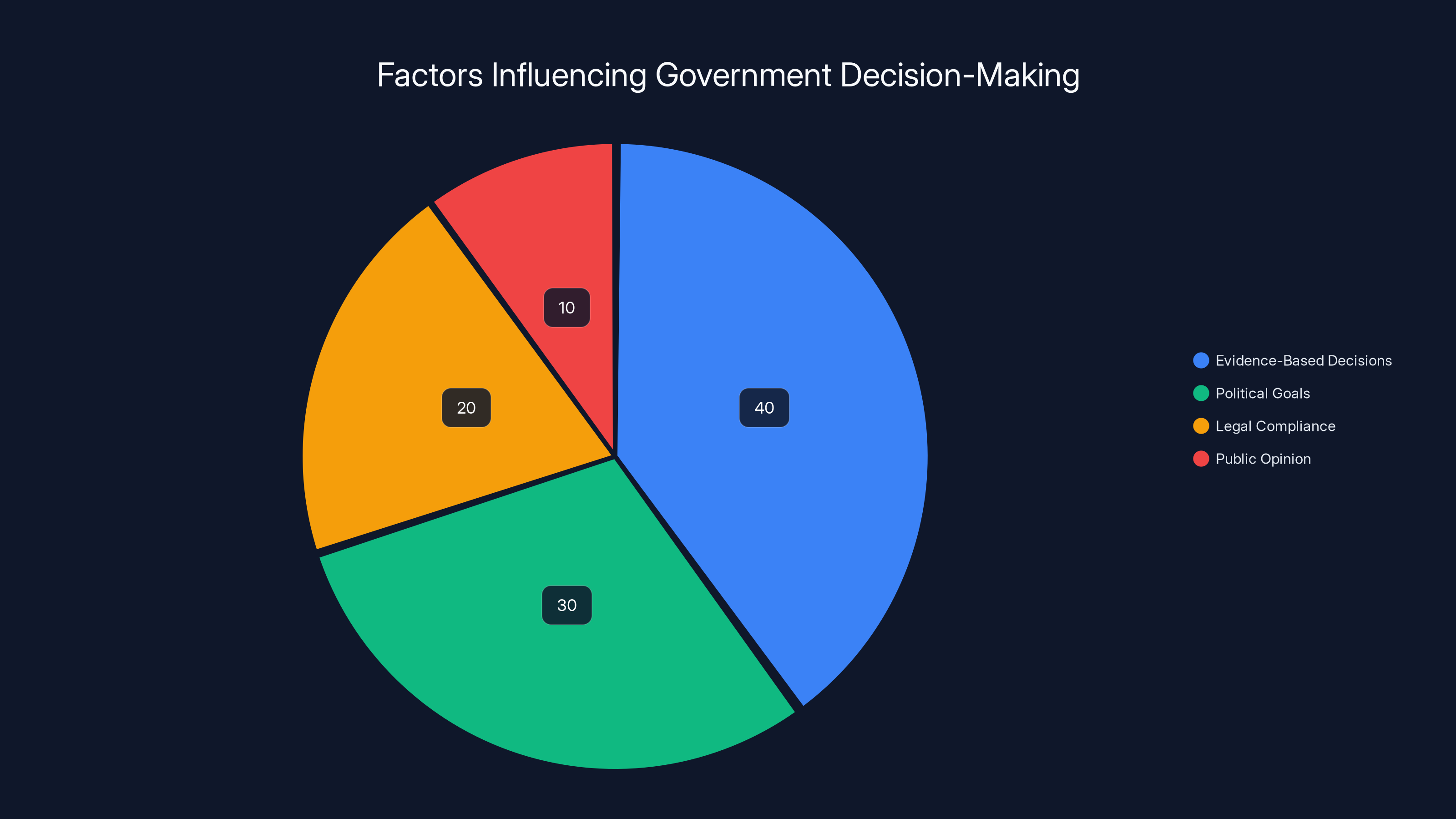

The Broader Pattern: How Doubt Gets Manufactured

The Climate Working Group didn't invent the strategy of manufacturing scientific doubt. It's been used before, and it follows a predictable pattern.

The tobacco industry perfected this playbook in the 1950s. Faced with overwhelming evidence that smoking causes cancer, they didn't try to hide the evidence. Instead, they funded research, created front groups, and generated the appearance of scientific controversy. They trained spokespeople to say things like "the science isn't settled" and "experts disagree." They weren't trying to prove smoking was safe. They were trying to create doubt about whether the evidence of harm was conclusive.

It worked remarkably well. For decades, they maintained political space for an industry that killed millions of people. All by manufacturing doubt.

The Climate Working Group is following the same playbook, but with less subtlety. The goal is straightforward: create the appearance that the scientific evidence for climate risks is controversial or questionable. If you can do that, you can argue that regulations based on that evidence should be delayed, weakened, or eliminated pending further study.

Here's how the pattern works:

Step one: Assemble contrary experts. Find scientists and technical people who, for whatever reason, are skeptical of the mainstream consensus. This doesn't require many people. A handful of contrarian voices is enough if you can present them as legitimate scientists rather than outliers.

Step two: Fund or organize their work. Give them a platform, resources, and legitimacy. A report from a "Climate Working Group" at the Department of Energy sounds more authoritative than a paper from an independent skeptic. Same content, different framing.

Step three: Dismiss mainstream science as biased. When actual experts criticize the contrarian work, don't engage with the criticism. Instead, argue that the critics are politically motivated, ideologically biased, or financially invested in promoting alarmism.

Step four: Create the appearance of balance. Use media and policy discussion to present the "both sides" narrative. If the public hears that there's debate among scientists, they're more likely to support regulatory delay or weakening.

Step five: Use that appearance of balance to delay action. "The science isn't settled." "We need more research." "Experts disagree." All of these buying time for the industry or policy sector being challenged.

The Climate Working Group was attempting this exact strategy. The emails make it clear. And the judge's ruling makes it clear that this strategy is illegal when executed through federal advisory committees.

But here's the troubling part: the ruling only applies to federal advisory committees. There are other ways to manufacture doubt that don't violate FACA. You can fund independent research. You can create front groups that aren't technically government committees. You can place contrarian experts in positions of influence within government agencies. The underlying strategy remains viable even if this particular execution was illegal.

Estimated data suggests that a majority of the Climate Working Group members were aligned with the Cato Institute or similar viewpoints, rather than representing a balanced scientific perspective.

The Scientific Response: What Climate Scientists Said About the Report

While the legal case was unfolding, something else happened that's important context: the scientific community organized a formal review of the Climate Working Group's report.

This was necessary because the report was claiming to challenge the scientific foundation of EPA regulations. If that were true—if the report had identified genuine scientific flaws in the endangerment finding or in climate science more broadly—that would matter. That would be worth discussing.

But when climate scientists actually read the report and evaluated its claims against the evidence, what they found was a document full of errors, misrepresentations, and arguments that had already been thoroughly addressed in the literature.

The report wasn't cutting-edge work that challenged a consensus that had become too comfortable. It was retreading arguments that had been made and refuted for years. It was citing studies selectively. It was mischaracterizing the state of scientific understanding. It was relying on the kind of rhetorical strategies that are common in manufactured doubt but that don't hold up in actual scientific debate.

The interesting part is that the DOE staff members who reviewed the report internally said many of the same things. The career scientists at the Department of Energy—people actually working in government who understand the technical issues—identified the same flaws. Their critiques aligned with what the broader scientific community would later say.

But the Climate Working Group wasn't interested in fixing those flaws. They weren't interested in engaging with the criticism. The emails show they dismissed it as bias.

This is the pattern again: when experts criticize your work, don't improve your work. Dismiss the experts.

The fact that the report was full of problems doesn't automatically mean the endangerment finding is correct. But it does mean that this particular challenge to the endangerment finding is weak. It does mean that if the government wants to overturn the endangerment finding, it's going to need much stronger scientific ground than this report provided.

And that matters for what comes next.

What Actually Happens Next? The Endangerment Finding Question

So here's the practical question: what happens now? The judge has ruled that the Climate Working Group violated federal law. The group has been disbanded. The emails are public. But the government still wants to overturn the endangerment finding. Is this ruling actually going to stop that?

Probably not directly. The ruling doesn't say that the endangerment finding must stand. It doesn't say the EPA can't reconsider its 2009 decision. What it says is that if the government wants to build a case for overturning that finding, it can't do it through an illegal advisory committee process.

But there's an indirect effect that could matter. If the government tries to formally overturn the endangerment finding, that decision will almost certainly be challenged in federal court. And in those proceedings, this ruling and the underlying record could play a significant role.

First, the court could conclude that the government's approach to scientific decision-making is fundamentally compromised. If you're willing to violate FACA to manufacture doubt about climate science, what does that say about your credibility on the topic?

Second, the record now includes the fact that DOE staff—the government's own scientists—identified serious flaws in the report that was supposedly going to be the scientific basis for overturning the endangerment finding. A court would likely give weight to that.

Third, the manufactured nature of the doubt-creation effort is now documented in the public record. The judge didn't just rule that FACA was violated. She established that the violations were violations of a group that was specifically formed to produce a predetermined outcome. The strategic choice to operate in secret, to avoid peer review from outside experts, to dismiss mainstream science as biased—all of this is now part of the court record.

But here's what's also worth noting: there's reporting that the administration's effort to overturn the endangerment finding has stalled because the scientific case is perceived as too weak. Not because of this court ruling, but because the underlying science just isn't there.

If the government decided to move forward anyway, it would be doing so despite weak evidence—and despite now being on the record of having tried to manufacture stronger evidence illegally. That's not a strong position for defending your decision in court.

The broader point is that the ruling matters not because it forbids the government from reconsidering the endangerment finding, but because it establishes that the government's approach to building the case for reconsideration is legally and procedurally compromised.

Both climate scientists and DOE staff rated the report poorly, highlighting its lack of scientific accuracy and engagement with criticism. Estimated data.

The Institutional Problem: When Agencies Stop Trusting Their Own Scientists

One of the most troubling aspects of this whole situation is what it says about institutional trust within the Department of Energy and other government agencies.

The Climate Working Group was organized by a political appointee. It cherry-picked outside experts to align with a predetermined conclusion. When it rejected criticism from DOE staff scientists—people whose job it is to provide technical expertise—it revealed something important: the leadership of the agency was not interested in the agency's own scientific expertise.

This creates a real problem. Government agencies work because they employ expertise. The EPA has experienced environmental scientists. The DOE has experienced energy and climate scientists. The National Institutes of Health have experienced medical researchers. When political leadership decides that these experts are obstacles rather than resources—when it actively works around them rather than with them—something fundamental breaks.

The pattern of the Climate Working Group fits into a broader approach: assemble an outside group of people willing to reach a desired conclusion, bypass the agency's own scientists, and use the outside group's report as the basis for policy decisions. This might create an appearance of expert support for the policy. But it actually undermines the institution's credibility and expertise.

Because here's what happens over time: expert scientists and technical staff at government agencies understand what's being done. They see their own work being dismissed and their own criticisms being ignored. They understand that their value to the agency has shifted from providing expert advice to rubber-stamping predetermined conclusions.

Some will leave for other opportunities. Some will stay but become demoralized. And the institutional capacity for genuinely expert analysis gets depleted.

This is particularly damaging in agencies that are supposed to be protecting public health or environmental quality. If the EPA stops trusting its own environmental scientists. If the USDA stops trusting its own agricultural scientists. If the FDA stops trusting its own medical scientists. Then you have agencies that look like agencies from the outside but that have lost their actual capacity to function as expert institutions.

The Climate Working Group case reveals this dynamic in miniature. A government agency deliberately circumvented its own scientific expertise to build a case for a predetermined conclusion. That's not how expert institutions work.

Federal Advisory Committee Act: What It Is and Why It Matters

Let's take a step back and understand FACA itself, because it's not a well-known law, but it's actually important for how government operates.

FACA was passed in 1972, in the aftermath of Watergate and other governance scandals that had eroded public trust in government. The basic idea was simple: if the government is going to have advisory committees providing advice to agencies, the public deserves to know who's on those committees, what advice they're giving, and how that advice influences decisions.

The law requires that advisory committees be:

Balanced. Committee membership should represent a range of perspectives. You can't stack a committee entirely with people who share one viewpoint and then claim the committee represents a consensus.

Open. Committee meetings should be open to the public. No secret meetings where back-channel deals are made or where members coordinate to influence policy in ways they wouldn't want public.

Transparent. Committee records should be kept and made available to the public. Decisions that influence government policy shouldn't be made behind closed doors.

These requirements exist because advisory committees can have enormous influence over government decisions. If a committee says "the evidence supports this policy," that can be incredibly powerful in policy debates. Public decision-makers can point to the committee and say "experts agree." But if that committee was stacked, if no one outside it knew what was being discussed, then the appearance of expert agreement is fake.

FACA prevents that. Or at least, it's supposed to prevent it.

The Climate Working Group violated the spirit and the letter of FACA. It was not balanced—it consisted of people selected specifically to reach a predetermined conclusion. It did not hold open meetings—in fact, it operated in secret. And it did not maintain transparent records—members were explicitly instructed to use personal email to avoid FOIA requests.

The judge's ruling establishes that these violations happened and that they matter.

But FACA has limitations. It applies only to committees formally designated as advisory committees. If you create something and call it something else—a working group, a task force, a study group—you might be able to avoid FACA requirements even if you're doing exactly the same thing an advisory committee would do.

That's one reason the government's initial argument was that FACA didn't apply: maybe this wasn't really an advisory committee, so FACA doesn't govern it. The judge rejected that argument, but the fact that the government tried to make it shows how the law can be evaded.

Going forward, the Climate Working Group ruling establishes that you can't evade FACA by just not calling something an advisory committee. If it looks like an advisory committee, if it functions like an advisory committee, then FACA applies. But smart government actors will look for ways to work around the ruling that don't involve formal advisory committees.

The court ruling indirectly affects the government's ability to overturn the endangerment finding, with a high likelihood of court challenges and impacts on scientific credibility. (Estimated data)

The Endangerment Finding and Climate Regulation: What Depends on It

Understanding the bigger picture requires understanding what actually depends on the endangerment finding.

When the EPA issued the endangerment finding in 2009, it unlocked the agency's ability to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act. This is important because the Clean Air Act is powerful legislation. Once the EPA finds that a pollutant endangers public health, it has authority to set emission standards for that pollutant.

The endangerment finding led to regulations on power plants, vehicles, refineries, and other sources. Some of these have been rolled back or weakened over the years, but they were based on the endangerment finding. If you overturn that finding, you undermine the legal basis for all of them.

But the endangerment finding isn't just a legal abstraction. It's a determination based on scientific evidence. The EPA looked at the best available science and concluded that greenhouse gases pose a risk to public health and welfare. That conclusion is backed by decades of research, agreement among every major scientific organization, and physical understanding of how CO2 traps heat in the atmosphere.

The question the Trump administration seems to be asking is: can you overturn a finding that's based on overwhelming evidence by assembling a group of contrarian scientists to argue that the evidence is wrong?

The answer that the courts are likely to give is: not through an illegal advisory committee process. And possibly not at all, because the evidence is what it is.

Regulation depends on the endangerment finding. But so does something broader: the idea that government decisions about matters of public health and environmental protection should be based on evidence. If you can overturn an endangerment finding that's based on massive amounts of evidence by manufacturing doubt and using a biased advisory process, then evidence stops mattering.

The judge's ruling doesn't prevent the government from trying. But it does establish that they can't do it through processes that violate federal law in the attempt.

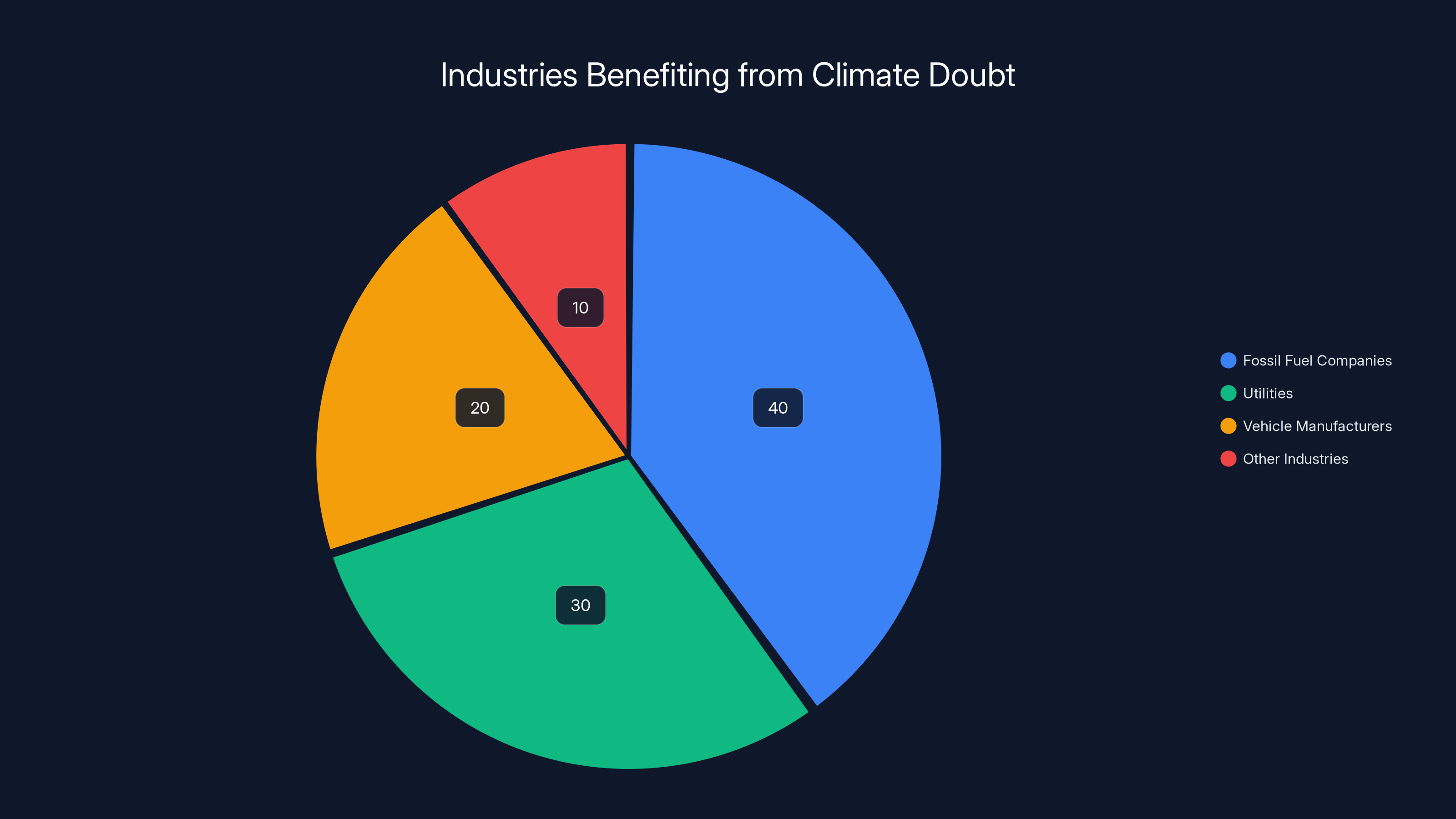

Who Benefits from Climate Doubt? Following the Money

It's worth asking: why does this matter enough that people are willing to fund the manufacture of doubt?

The answer has to do with the costs of climate regulation. If the EPA issues greenhouse gas regulations, some industries face increased compliance costs. Power plants have to install pollution control equipment or switch to cleaner energy. Oil refineries have to reduce emissions. Vehicle manufacturers have to improve fuel efficiency or electrify.

These changes cost money. For the companies involved, it makes economic sense to fund efforts to delay or prevent those regulations. And one effective strategy is to create doubt about whether the regulations are actually necessary.

The tobacco industry understood this decades ago. Every year they delayed regulation while creating doubt cost them billions in avoided compliance costs. Climate regulation faces opposition from similar sources: fossil fuel companies and utilities that would bear the costs of transitioning to cleaner energy.

The Climate Working Group didn't appear out of nowhere. It was organized because there's money in climate doubt. Not vast sums, but enough to fund a political appointee, enough to convene a group of contrarian scientists, enough to produce a report.

And for the money being spent, the value is enormous if it works. If you can create enough doubt that regulation is delayed by a few years, that's worth billions to the industries that would be regulated. If you can prevent regulation entirely, that's worth vastly more.

The judge's ruling might make it slightly more expensive to manufacture climate doubt in certain ways. It closes off one particular avenue: using federal advisory committees. But the underlying economic incentive remains. The industries facing climate regulation still have financial motivation to fund doubt-creation efforts.

What changes is the method. You probably can't use formal federal advisory committees anymore, at least not the way the Climate Working Group did. But you can fund independent research. You can create think tanks. You can place contrarian experts in government positions outside the advisory committee framework.

The incentive to manufacture doubt is powerful enough that the Climate Working Group was only one iteration of a strategy that will continue in different forms.

The Implications for Future Administrations and Climate Policy

What does the Climate Working Group ruling mean for how future administrations handle climate policy?

First, it establishes that you can't use federal advisory committees to manufacture doubt about settled science in order to justify reversing regulations. That avenue is closed, or at least much more costly in legal terms.

Second, it establishes a record: when you try to overturn a regulation based on overwhelming evidence using a secretly-formed, cherry-picked group of contrarians, courts notice. And they will take that into account if you later argue that your new policy decision is based on solid evidence.

Third, it provides a roadmap for opponents of government action. If an administration tries to overturn the endangerment finding or weaken climate regulations, organizations like the Environmental Defense Fund and Union of Concerned Scientists now know that the courts will enforce FACA requirements. They can sue, they can force transparency, they can get the process enjoined.

But here's where it gets complicated: does the ruling actually prevent the endangerment finding from being overturned? No. It prevents one illegal process for trying to overturn it. An administration could potentially try to overturn it through other means: by arguing that scientific understanding has changed, that new evidence contradicts the 2009 finding, that the risks have been overestimated.

The difference is that those arguments would have to be made directly and would have to be supported by evidence. You couldn't hide behind a secretly-formed advisory committee. You couldn't rely on a rigged process. You'd have to make the scientific case openly and defend it against expert scrutiny.

That's a real constraint, because the scientific case is actually pretty weak. The endangerment finding is based on solid evidence. Overturning it would require powerful contrary evidence. The Climate Working Group was supposed to provide that evidence, but instead it provided a report that mainstream climate scientists and DOE staff scientists both found problematic.

So the ruling doesn't prevent attempts to overturn the endangerment finding, but it does make those attempts more difficult and more expensive. And it puts administrations on notice that if they try illegal processes, those will be challenged and likely enjoined.

The Broader Question: Can Government Be Trusted With Science?

All of this raises a deeper question about the relationship between government and science.

Governments use science all the time. They regulate pharmaceuticals based on clinical trial data. They set safety standards based on engineering research. They establish environmental regulations based on toxicology and ecology studies. They decide on energy policy based on physics and economics.

But government is also political. Different administrations have different goals and values. When a scientific finding contradicts those goals, there's pressure to either ignore the finding or to challenge it.

Sometimes that challenge is legitimate. Science changes. New evidence emerges. Findings that seemed solid can be overturned. But there's a difference between "new evidence suggests the old consensus might be wrong" and "we've assembled a politically-appointed committee to manufacture doubt about evidence we don't like."

The Climate Working Group is an extreme example of the second approach. But less extreme versions happen constantly. Administrations appoint people who don't believe in the agency's mission. They reduce funding for research areas they don't like. They suppress or slow-walk the release of scientific findings. They pressure scientists to change conclusions.

The endpoint of all this—if it goes unchecked—is that government agencies stop being institutions grounded in evidence and become instead instruments of political will. They might use the language of science. They might employ scientists. But they're not actually doing science anymore.

The judge's ruling in the Climate Working Group case is a check against the most extreme version of this problem. It says: you can't form an advisory committee with the explicit goal of producing predetermined conclusions and then use that to overturn regulations based on evidence.

But it's only a partial check, because there are still ways to do similar things without triggering FACA violations. The underlying question—how do we ensure that government decisions about matters of public health and environmental quality remain grounded in evidence?—is not fully answered.

Practical Implications: What Happens to the Regulations?

So in practical terms: what's the status of climate regulations now?

The EPA's greenhouse gas emission standards for vehicles, power plants, and other sources remain in effect. They're based on the endangerment finding. The Climate Working Group ruling doesn't directly eliminate these regulations.

But there are regulations that have been rolled back or weakened in recent years, and the attempt to use the Climate Working Group to overturn the endangerment finding would have potentially given cover for further rollbacks.

What's changed is that the path to overturning the endangerment finding is now more difficult. You can't do it through an illegal advisory committee process. You'd have to make the scientific case directly, and you'd have to do it transparently.

Given that the scientific case is weak—given that DOE staff scientists found serious flaws in the Climate Working Group report, given that mainstream climate science has repeatedly and consistently concluded that greenhouse gases pose serious risks, given that every major scientific organization has endorsed that conclusion—the probability of successfully overturning the endangerment finding through legitimate means is low.

But the intent hasn't changed. There are still efforts underway to weaken climate regulations through other means. States are challenging federal regulations in court. Different executive orders are being issued. The underlying political goal—rolling back climate regulation—remains constant.

The judge's ruling is a constraint on one path to that goal. It's not the end of the story.

What about international implications?

It's worth noting that this is happening in a global context where other countries are moving in the opposite direction.

The European Union has established a far more aggressive climate regulatory framework. China, despite its status as the world's largest carbon emitter, is also investing heavily in renewable energy and emission reduction. Many countries have committed to net-zero targets and are establishing regulations to achieve them.

When the United States attempts to overturn its own climate regulations based on manufactured doubt, while other countries are moving forward with climate policy, it has implications beyond U. S. borders. It affects international climate negotiations. It affects the global energy transition. And it affects the credibility of U. S. institutions as evidence-based decision-makers.

If the United States government is willing to manufacture doubt about climate science to avoid regulation, why would any other country trust U. S. scientific claims on other matters? It's not just about climate policy. It's about institutional credibility.

The judge's ruling, by establishing that illegal processes to manufacture doubt will be challenged, is at least a partial answer to that credibility concern. But only partially, because the underlying political drive to overturn climate regulations is still there.

The Historical Context: Climate Policy and Partisan Conflict

This didn't come out of nowhere. There's a history here.

Climate policy in the United States has become increasingly polarized along partisan lines. That's not inherent—there's nothing about climate science or climate policy that should necessarily be partisan. But through a series of choices by political actors, it became that way.

In the 1980s, the evidence for human-caused climate change was building, but there was no strong partisan divide on the issue. The Montreal Protocol, which addressed ozone depletion, was passed with broad bipartisan support. There were Republican environmental leaders. Conservation and environmental protection were not uniquely partisan issues.

But as climate regulations started to look like they would have real economic costs for fossil fuel industries and energy-intensive sectors, those industries invested heavily in creating doubt. They found willing political partners. And through deliberate choices, climate regulation became a partisan issue in the United States.

Once that happened, scientific facts became tribal affiliations. If you're a Republican, you're supposed to be skeptical of climate science. If you're a Democrat, you're supposed to accept it. Neither of those positions has anything to do with evidence.

The Climate Working Group is a symptom of this politicization. An administration comes in wanting to roll back climate regulations. To do so, it needs some scientific cover. So it assembles a group of scientists who will provide that cover. The fact that the group is biased, that it operates in secret, that it violates federal law—these things matter less than the fact that it might provide political cover.

The judge's ruling doesn't solve the underlying polarization. It just establishes one boundary: you can't use illegal advisory committee processes to manufacture doubt. But the underlying political drive to overturn climate regulations remains.

Looking Forward: The Next Legal and Political Battles

So what's coming next?

First, the legal: If the administration continues efforts to overturn the endangerment finding, those efforts will almost certainly be challenged in court. Environmental organizations have already shown they're willing to litigate. The record from the Climate Working Group case will be available to them and to the courts.

Second, politically: There will be continued efforts to weaken climate regulations through different means. The Climate Working Group was one approach. There will be others. Some will stay within the bounds of legality (though maybe just barely). Some might not.

Third, scientifically: The question of whether climate change poses risks to public health and welfare is not actually in dispute among qualified experts. What is in dispute is policy: how aggressively should government regulate emissions? What's the right balance between regulation and economic costs? Those are legitimate policy debates. But they're different from scientific debates. You can't settle a policy disagreement by manufacturing doubt about science.

The Climate Working Group case is important because it establishes that boundary. It says: you can't use illegal government processes to manufacture scientific doubt to justify policy decisions. If you want to change climate policy, argue for different policies. But don't pretend that the underlying science is scientifically controversial when it isn't.

The legal and political battles over climate regulation will continue. But they'll continue with the knowledge that at least one illegal path has been blocked. And that might matter more than it initially appears.

FAQ

What is the Federal Advisory Committee Act?

The Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) is a 1972 law requiring that any advisory committees formed to provide guidance to federal agencies must be balanced in membership, hold open meetings, and maintain transparent records. FACA exists to prevent governments from secretly stacking advisory committees with biased experts to justify predetermined policy decisions. The law applies to committees formally designated as advisory bodies and requires compliance with transparency and balance requirements.

What did the judge rule about the Climate Working Group?

The judge ruled that the Trump administration's Climate Working Group violated the Federal Advisory Committee Act by operating in secret, failing to maintain public records, and selecting biased members. The judge established these violations as a matter of law and ordered the government to disclose all communications, including those sent to private email accounts. The ruling determined that the Climate Working Group had failed to comply with FACA's requirements for balanced membership, open meetings, and transparent record-keeping.

What is the endangerment finding and why does it matter?

The endangerment finding is the EPA's 2009 determination that greenhouse gases pose a risk to public health and welfare, issued after a Supreme Court ruling in Massachusetts v. EPA. This finding gives the EPA legal authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions under the Clean Air Act. The finding is based on peer-reviewed climate science and is supported by every major scientific organization. Without the endangerment finding, the EPA would lack legal authority for most of its climate regulations.

Why did the Climate Working Group operate in secret?

According to the leaked emails, the Climate Working Group deliberately operated in secret to limit public scrutiny. Members were explicitly instructed to use private email accounts rather than government email to avoid the possibility of their communications being disclosed under the Freedom of Information Act. The group also did not hold public meetings or maintain transparent records, violating FACA requirements. This secrecy was intentional, designed to prevent the public from understanding how the group was organized and what it was doing.

What did the leaked emails reveal about the group's purpose?

The emails show that the Climate Working Group was explicitly organized to produce a report that would undermine the EPA's endangerment finding and support efforts to overturn it. The group's organizers recognized that their members' views were outside the scientific mainstream but dismissed mainstream science as biased rather than reconsidering their own positions. The emails also reveal that the group was skeptical of subjecting their work to genuine peer review and instead focused on finding reviewers who would approve of their findings.

How does this ruling affect climate regulations?

The ruling doesn't directly overturn or eliminate existing climate regulations, which remain in effect based on the endangerment finding. However, it establishes that any attempt to overturn the endangerment finding through an illegal advisory committee process will be challenged and likely enjoined. The ruling makes it more difficult for the administration to use federal processes to manufacture doubt about climate science, though it does not prevent policy debates about how to regulate emissions or attempts to weaken regulations through other means.

What does "manufacturing doubt" mean in this context?

Manufacturing doubt is a strategy of creating the appearance of scientific controversy where expert consensus already exists. The Climate Working Group attempted to do this by assembling contrarian scientists and producing a report challenging climate science, while dismissing mainstream scientists as biased. The goal is not to prove that the consensus is wrong, but to create enough doubt that policymakers feel justified in delaying or weakening regulations based on the consensus.

Could the endangerment finding still be overturned?

Technically yes, but it would be very difficult. The endangerment finding is based on overwhelming scientific evidence supported by every major scientific organization. To overturn it, the government would need to present a compelling scientific case that the evidence doesn't actually support the finding. The Climate Working Group was supposed to provide that case, but its report was full of flaws that both DOE staff scientists and mainstream climate scientists identified. A court would likely be skeptical of any attempt to overturn the finding based on weak scientific arguments made through an illegal process.

What are the implications for future administrations?

The ruling establishes that federal advisory committees cannot be formed with the explicit goal of producing predetermined conclusions to justify predetermined policies. Future administrations can still pursue different climate policies, but they cannot do so through illegal advisory committee processes. The ruling also creates a record showing that when governments try to manufacture scientific doubt, courts will take notice and challenge those efforts.

How does this compare to how other scientific doubts have been manufactured historically?

The Climate Working Group follows a pattern pioneered by the tobacco industry in the 1950s: assemble contrarian experts, fund their work, dismiss mainstream science as biased, create the appearance of scientific controversy, and use that appearance to delay regulation. The pattern has been used to challenge scientific findings on acid rain, ozone depletion, and many other topics. What's different about the Climate Working Group case is that courts have now explicitly ruled that this approach violates federal law when executed through government advisory committees.

Conclusion: Democracy Requires Evidence-Based Government

The Climate Working Group case is fundamentally about whether government can make decisions based on evidence or whether political goals override evidence.

On one level, it's a technical legal ruling about compliance with the Federal Advisory Committee Act. The Department of Energy formed a committee, failed to follow the legal requirements, and got called out for it. Bureaucratic violation, bureaucratic consequence.

But beneath that surface is something more significant: an administration attempting to overturn a regulation based on overwhelming evidence by assembling a secret committee of contrarians and using that committee to manufacture doubt. The fact that this was illegal under FACA is important. But the fact that they tried to do it at all is what really matters.

Democracy depends on some baseline commitment to truth-seeking. You can disagree with policies. You can argue for different regulations. You can say that the economic costs of compliance are too high. Those are legitimate political debates. But you can't govern effectively if you're also pretending that scientific facts are political matters that can be resolved through rhetoric and manufactured doubt.

The judge's ruling doesn't solve the underlying political conflicts about climate policy. Those will continue. Different administrations will continue to have different views about how aggressively to regulate greenhouse gases. That's normal and healthy democratic disagreement.

What the ruling does establish is a boundary: you can't use illegal government processes to manufacture doubt about settled science to justify reversing regulations. If you want to change policy, make the case openly. If the scientific foundation for current policy is actually wrong, present evidence. But don't hide behind secret committees and biased processes.

That's a constraint that matters. Not because it will prevent all attempts to overturn climate regulations—political drives are powerful and can find other paths. But because it establishes that courts will enforce the law and that illegal processes to manufacture doubt will be challenged.

The Climate Working Group saga is a reminder that the relationship between government and science is genuinely important, and that democratic institutions have a role to play in protecting evidence-based decision-making. The judge in this case understood that. Her ruling reflects that understanding.

What happens next depends on whether future administrations understand it too.

Use Case: Need to create reports documenting government decisions and policy analysis? Generate professional policy briefs and analysis documents with Runable's AI-powered document automation starting at $9/month.

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- Federal judge ruled the Climate Working Group violated the Federal Advisory Committee Act by operating in secret and selecting biased members

- The group was explicitly designed to manufacture doubt about climate science to support efforts to overturn the EPA's endangerment finding

- Leaked emails show members were instructed to use private email accounts to avoid public scrutiny and to avoid genuine peer review

- The endangerment finding, issued in 2009, gives the EPA legal authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions under the Clean Air Act

- The court's ruling makes it illegal to use federal advisory committee processes to manufacture scientific doubt, though political efforts to weaken climate regulations may continue through other means

Related Articles

- DOJ Epstein Files Redaction Failure: What Happened and Why It Matters [2025]

- NIH Institute Directorships Politicization: The Power Struggle [2025]

- AI Drafting Government Safety Rules: Why It's Dangerous [2025]

- How Disinformation Spreads: The Border Patrol Shooting and Political Narratives [2025]

- State Attorneys General Fight Trump: The Last Constitutional Check [2025]

- EPA Closes Generator Loopholes: AI Data Center Expansion Hits Federal Wall [2025]

![DOE Climate Working Group Ruled Illegal: What the Judge's Decision Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/doe-climate-working-group-ruled-illegal-what-the-judge-s-dec/image-1-1770063007182.jpg)