The Endangerment Finding Battle: Why US Climate Rules Are About to Face Their Biggest Test

Something seismic just happened in environmental law, and most people haven't noticed.

The Environmental Protection Agency is dismantling the scientific and legal foundation that's allowed it to regulate greenhouse gases for the past 15 years. The endangerment finding, a 2009 ruling that seems obscure until you understand what it does, represents the bedrock of every climate regulation issued in the United States since Obama took office. Power plant emissions standards? Built on the endangerment finding. Vehicle emissions regulations? Same foundation. The authority to regulate methane, refrigerants, and dozens of other gases that trap heat in the atmosphere? All of it traces back to this one finding.

Now it's about to disappear, and nobody really knows what happens next.

The rollback isn't just a policy change. It's opening a Pandora's box of legal uncertainty that will reshape how climate change is regulated in America. Oil companies are panicking about losing their strongest legal defense against state and local climate lawsuits. Automakers are scrambling to figure out how to plan manufacturing when the regulatory landscape might shift beneath them. Environmental groups are preparing for a Supreme Court fight that could determine whether the federal government has any authority to address climate change at all.

For business, for law, for energy markets, and for every state and city trying to tackle climate change: this is the moment everything changes.

TL; DR

- The endangerment finding is the EPA's core authority to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act—remove it, and the entire regulatory framework collapses

- Right-wing groups spent 15+ years planning this rollback, using flawed scientific arguments that courts will likely reject

- Oil companies oppose the rollback because they depend on federal climate authority to defend against state and local lawsuits

- Automakers face manufacturing chaos in an uncertain regulatory environment where rules could change mid-production cycle

- This fight heads to the Supreme Court, where the outcome will determine whether climate regulation happens at the federal level or not at all

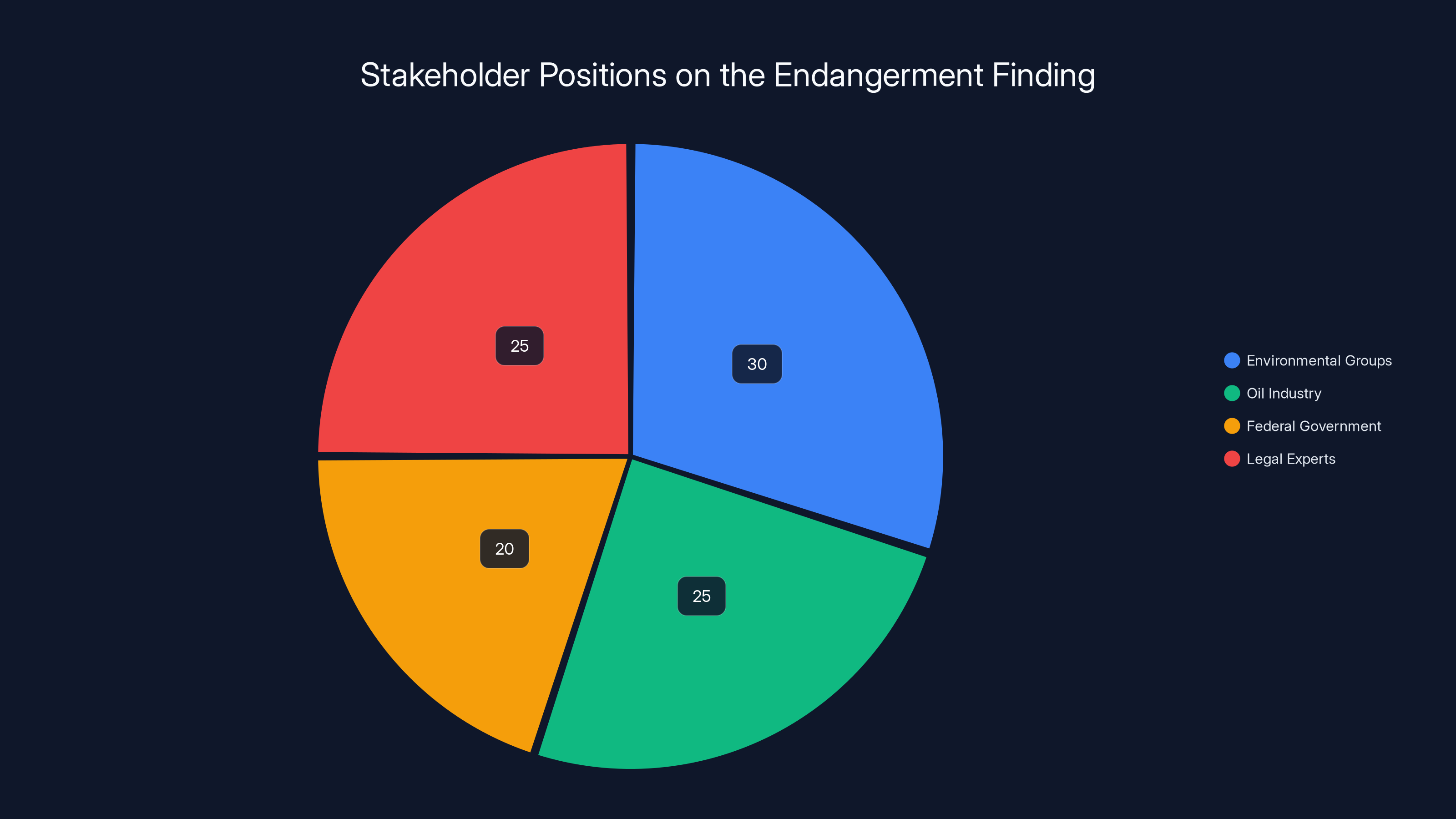

Estimated data: Environmental groups and legal experts generally support the endangerment finding, while the oil industry has mixed views due to legal protections it provides.

What Is the Endangerment Finding and Why Does It Matter So Much?

Let's start with the basics, because this ruling is genuinely strange to understand without context.

The Clean Air Act, passed in 1963 and significantly strengthened in 1970, gives the EPA a simple mandate: regulate any type of air pollution that might constitute a hazard to public health and welfare. Simple enough. The EPA has been using this authority for decades to regulate nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, particulate matter, and dozens of other pollutants.

But for years, there was one elephant in the room. Greenhouse gases. The EPA had never formally declared that greenhouse gases pose a risk to public health. Without that declaration, the agency would argue it lacked authority to regulate them under the Clean Air Act. It was a legal loophole, and it was deliberate.

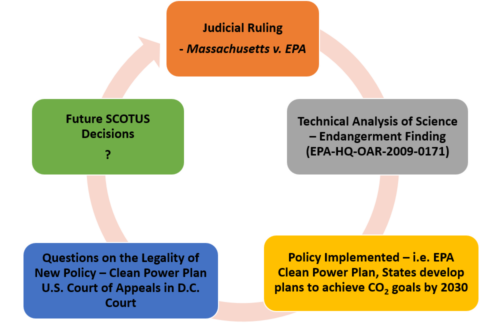

Then came Massachusetts v. EPA in 2007, a Supreme Court decision that changed everything. Massachusetts and 11 other states sued the Bush administration, arguing that the EPA had a responsibility to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles under the Clean Air Act. The Bush administration countered that greenhouse gases weren't air pollutants in the way the law intended.

The Supreme Court disagreed. The Court ruled that greenhouse gases were indeed air pollutants under the statute, and the EPA had to either regulate them or provide a scientific basis for why they shouldn't. The ruling was narrow, focused on motor vehicles, but the implications were massive.

This forced the EPA's hand. In 2009, under the Obama administration, the EPA issued the endangerment finding: a formal determination, backed by scientific evidence, that greenhouse gases pose a threat to public health and welfare. The finding was straightforward. It said greenhouse gas emissions from human activities are increasing atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases. These increases are causing climate change. Climate change is harming the environment and public health.

Once that finding existed, the Clean Air Act's logic became unavoidable. If greenhouse gases harm public health, and the EPA has authority to regulate pollutants that harm public health, then the EPA must regulate greenhouse gases. The endangerment finding was the legal bridge that connected the dots.

For 15 years, every major climate regulation the EPA issued traced its authority back to this finding. The finding wasn't just a statement of science. It was the legal architecture holding up the entire federal climate regulation structure. Remove it, and everything collapses.

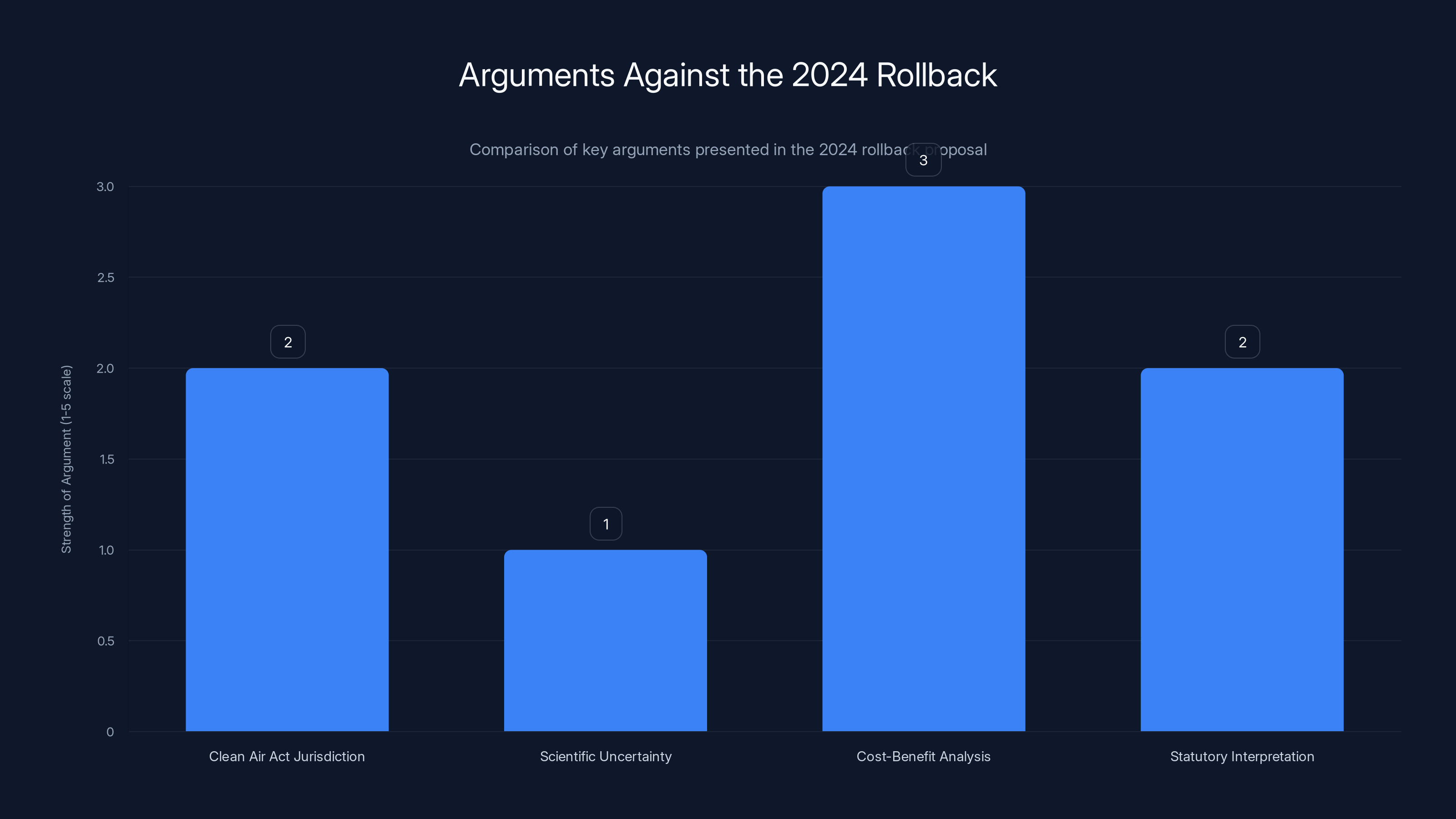

The rollback proposal's arguments were generally weak, with scientific uncertainty rated the lowest due to misrepresentation and cherry-picking. (Estimated data)

How Did We Get Here? 15 Years of Right-Wing Opposition

The endangerment finding has been a political target since before it officially existed.

Here's the strange part: the science behind the endangerment finding wasn't controversial. The EPA's analysis was solid. Multiple peer-reviewed assessments, data from ice cores and satellite records, and global climate science all pointed in the same direction. Greenhouse gases trap heat. That heat is warming the planet. The warming causes harm. The case was airtight.

But from the moment Massachusetts v. EPA was decided, right-wing groups understood the implications. Once the endangerment finding existed, climate regulation would follow inevitably. The Clean Air Act's logic would demand it. These groups set out to dismantle the finding before it could take root.

The Heritage Foundation led the charge. A network of fossil fuel-aligned think tanks, legal foundations, and ideological organizations began producing arguments against the finding. Some claimed greenhouse gases shouldn't be regulated because they're global and therefore outside the EPA's jurisdiction. Others argued the finding was based on flawed methodology. Still others pushed the idea that climate science itself was uncertain enough that the EPA shouldn't regulate.

None of these arguments had merit. They were clever legally, crafted to sound technical and reasonable. But they didn't hold up to scrutiny. Climate scientists reviewed them and found them wanting. Legal experts noted that the Clean Air Act's language made no distinction between local and global pollutants.

Yet the arguments kept coming. During Trump's first term, anti-regulation ideologues inside and outside the administration pushed the EPA to challenge the endangerment finding. Scott Pruitt, Trump's first EPA administrator, made clear his opposition to the finding. But here's where something unexpected happened: the business community pushed back. Oil majors, electric utilities, and automotive companies told the EPA that repealing the endangerment finding would create chaos. Industry preferred certainty, even if that meant climate regulation.

This was a huge blow to the anti-regulation movement. They'd expected industry to be their natural ally. Instead, industry was telling them the endangerment finding actually provided valuable stability. Companies knew what rules they had to follow. They could invest in compliance technologies with confidence. Repealing the finding would create uncertainty. Would new administrations issue new regulations? Which states would step in? Would litigation explode? No company wanted that.

So Pruitt retreated. Trump's second EPA administrator, Andrew Wheeler, also declined to attack the endangerment finding, despite pressure. The finding seemed unkillable.

But the right-wing coalition never gave up. They kept building legal arguments, funding sympathetic scientists, and pushing their vision of climate deregulation. They had patience. They had resources. They understood this was a long game. And eventually, they got their moment.

The 2024 Rollback: How the Arguments Fall Apart

When the Trump administration released its draft rollback proposal in summer 2024, observers got their first real look at the legal strategy. And it was striking how much spaghetti was being thrown at the wall.

The administration bundled together every argument against the endangerment finding: Clean Air Act arguments about jurisdiction, scientific arguments about climate causation, cost-benefit arguments about regulations, statutory interpretation arguments about what counts as an air pollutant. It was a kitchen sink approach, throwing everything hoping something would stick.

The Clean Air Act jurisdiction argument claimed that because greenhouse gases are emitted globally and affect climate patterns globally, they fall outside the EPA's authority to regulate "air pollution" affecting a particular geographic area. The statute was written for local pollutants like smog and acid rain. Greenhouse gases are different. They're a global problem, not a local one.

But this argument has a fatal flaw: the Clean Air Act doesn't distinguish between local and global pollutants. It simply says the EPA can regulate "any air pollutant" that endangers public health. It doesn't matter if the pollutant is local or global. And even if it did, greenhouse gas emissions happen locally. The EPA can regulate the tailpipe emissions, the power plant smokestacks, the industrial sources releasing methane. Those are all local sources. The fact that the molecules eventually mix into the global atmosphere doesn't change that.

The scientific arguments tried to undermine the findings of climate science itself. A report produced by the Department of Energy, authored by five known climate contrarians, claimed that climate science was too uncertain to support the endangerment finding. It misrepresented peer-reviewed studies, cherry-picked data, and ignored the overwhelming consensus in climate research.

When this came to light, many of the scientists whose work was cited in the report complained. Their findings had been misused or taken out of context. The academic community responded with criticism. And a federal judge ruled that the committee that produced the report was assembled illegally, violating federal advisory committee law.

Yet the administration still used these arguments in its final rollback proposal. Legal experts predict the scientific arguments will be demolished in court. A judge in a lawsuit will ask: what peer-reviewed evidence supports your claim? And the administration will have to defend a report that the scientific community rejected and that a court already found was produced illegally.

The cost-benefit arguments claimed that climate regulation is too expensive and the benefits too uncertain to justify. But the EPA's endangerment finding isn't supposed to be a cost-benefit analysis. It's a determination of whether a pollutant endangers public health. Once that determination is made, the Clean Air Act requires regulation. The cost-benefit analysis happens later, in designing specific rules. And the research on climate damages is clear: the costs of inaction far exceed the costs of regulation.

Put together, the rollback's arguments are a house of cards. They're legally weak, scientifically unsound, and contrary to how the Clean Air Act actually works. Which raises an obvious question: why is the administration pushing forward with arguments it knows are weak?

The answer is ideology. This isn't a good-faith legal challenge. It's an attempt to dismantle climate regulation regardless of the legal merits. The administration is counting on one of two outcomes: either courts will surprise everyone and reject decades of legal precedent, or the process of litigation will create enough uncertainty and delay that climate regulation effectively freezes in place.

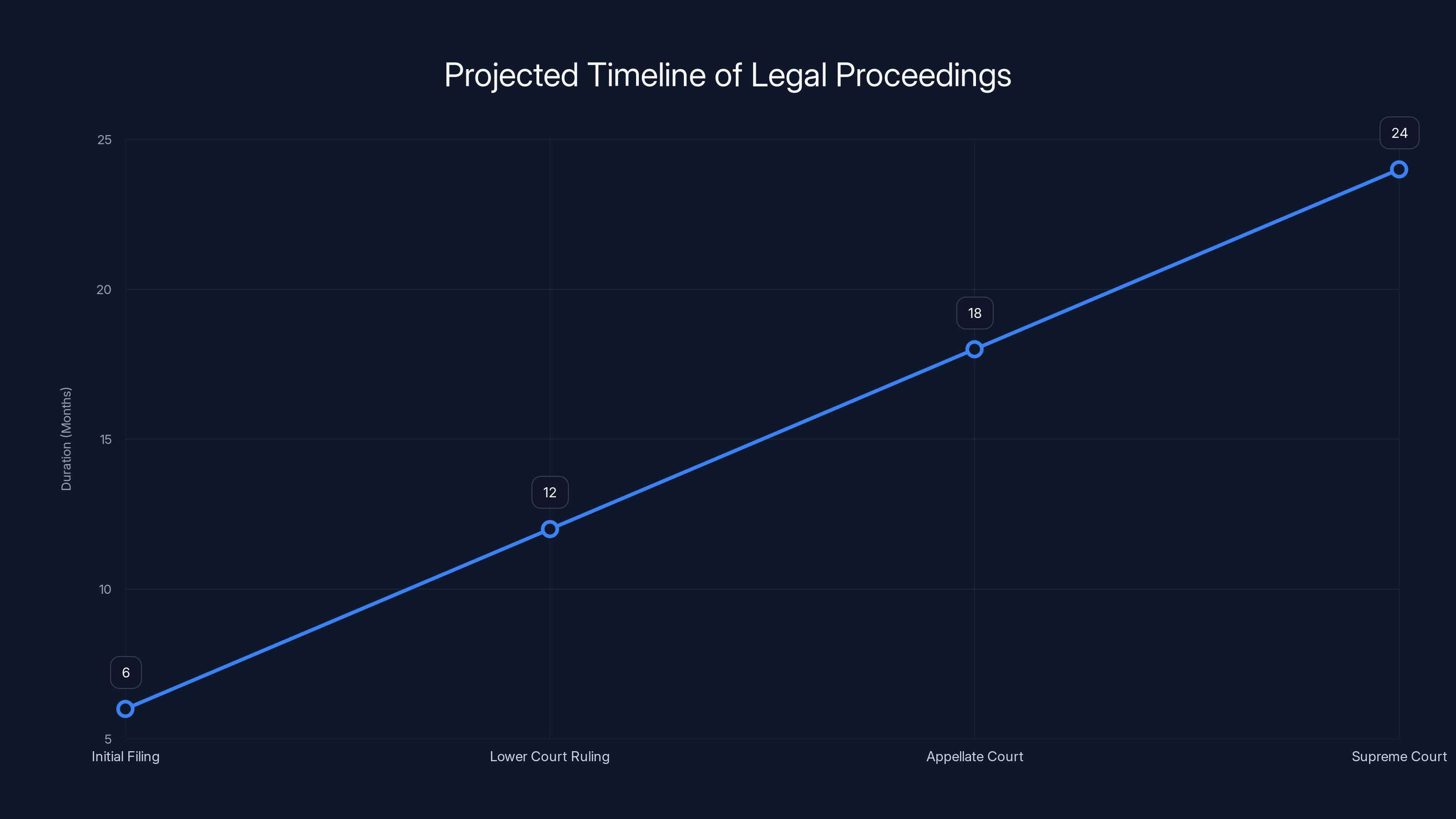

The legal proceedings following the EPA's repeal could span over two years, with each stage potentially taking several months. Estimated data.

Why Oil Companies Are Panicking About the Rollback

Here's something counterintuitive: Big Oil doesn't want the endangerment finding repealed.

This seems backwards. You'd think fossil fuel companies would be thrilled to see climate regulation dismantled. But the industry faces a bigger threat: state and local climate lawsuits. Cities and states across America have filed lawsuits against oil majors, alleging they knowingly deceived the public about climate science and should pay for climate damages.

These lawsuits could be catastrophically expensive. We're talking hundreds of billions in potential liability. A company facing a lawsuit in California or New York needs a strong legal defense. And the oil industry has found that defense in an unexpected place: the EPA's authority to regulate greenhouse gases.

The legal argument goes like this: the EPA has authority to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act. That authority is exclusive. States and municipalities can't also regulate greenhouse gases, because federal law preempts them. Therefore, state and local climate lawsuits shouldn't be allowed. The federal government controls climate policy.

This is a brilliant defensive strategy. The very regulation the oil industry fought for 15 years is now its strongest shield against liability. Remove the endangerment finding, and this defense collapses. If the EPA doesn't have authority to regulate greenhouse gases, then states do. State climate lawsuits become viable. And that means oil companies face potentially unlimited liability in multiple jurisdictions, each with different standards and judges.

So the American Petroleum Institute, the industry's leading lobbying group, sent a letter to the EPA with a strange request: if you must repeal the endangerment finding, please clarify that it only applies to tailpipe emissions from vehicles, leaving stationary sources like power plants protected by the rule.

It's an almost comical position. The industry is begging the EPA to partially keep the regulation it's been fighting. But it makes perfect sense from the companies' perspective. They need federal authority to exist, so they can argue state lawsuits are preempted. They don't care if that authority is used for vehicle emissions. They just need it to exist.

The administration's response will likely disappoint the industry. There's no indication the rollback will be selective or nuanced. If the endangerment finding is repealed, it's repealed. The entire legal foundation for federal climate regulation goes away.

For oil companies, this is a nightmare scenario. They spent billions adapting to EPA regulations. They settled climate lawsuits in some jurisdictions. They made investments assuming federal climate law was stable. Now, suddenly, that entire legal landscape is being bulldozed, and they face a patchwork of state regulations and the prospect of massive liability.

Automotive Companies in a Regulatory Minefield

Carmakers face a different problem: they can't plan production without knowing what the rules will be.

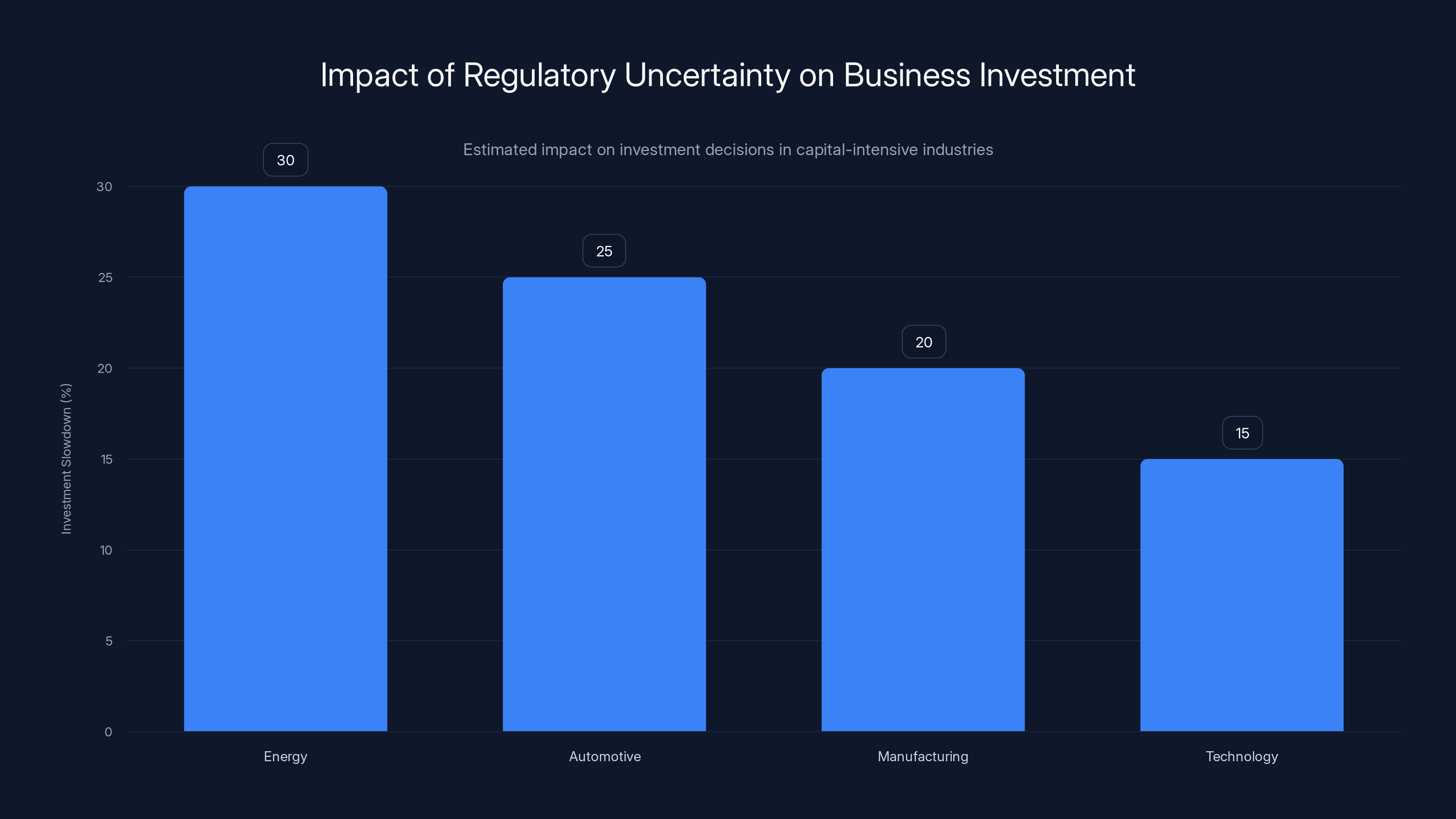

Automotive manufacturing is a long-cycle business. A company deciding whether to build a new electric vehicle plant is making a 10 to 15-year commitment. They need to know what regulations will govern vehicle emissions during that entire period. Will standards get stricter? Looser? Stay the same? The answer drives crucial investment decisions.

Under the current endangered finding, the answer is clear. The EPA has authority to regulate emissions. Future administrations will likely continue strengthening standards. Automakers can invest in electric vehicle technology with confidence. That's why the Big Three have all made major commitments to electrification. Tesla forced their hand, but the regulatory environment made the transition economically viable.

Now, that certainty is gone. If the endangerment finding is repealed, the regulatory environment becomes unpredictable. The current administration might freeze regulations or roll them back. The next administration might bring them back. State governments might impose their own standards. Litigation might create new requirements. Nobody knows.

In this uncertainty, what does a company do? The logical answer is to slow down. Don't invest in new EV plants. Don't commit to supply chain changes. Don't retool factories. Wait and see what happens. And if the rollback creates a legal fight that lasts 3 to 5 years, that's 3 to 5 years of companies pulling back investment from electric vehicles.

The irony is sharp: by dismantling the legal foundation for climate regulation, the administration might actually slow the transition to clean energy. Industry needs certainty more than it needs a particular rule. Destroy the foundation, and you destroy the certainty.

Some automakers have quietly expressed concern about this. Their public comments on the endangerment finding rollback note that regulatory uncertainty makes business planning difficult. It's not a passionate defense of the endangerment finding. It's a pragmatic statement: we need to know what the rules are, even if we have to comply with them.

The Trump administration's response, so far, has been dismissive. The administration has shown repeatedly that ideology matters more to it than business stability. It's willing to disrupt supply chains, overturn settled regulations, and create legal chaos if that serves its ideological goals. The automotive industry is learning what other sectors already know: regulatory certainty under this administration isn't guaranteed.

Estimated data shows that regulatory uncertainty can lead to significant investment slowdowns, particularly in capital-intensive industries like energy and automotive.

How the Legal Fight Will Actually Play Out

Assuming the endangerment finding is officially repealed, the next chapter is litigation. This will be complicated and expensive and might take years.

Environmental groups and progressive states will immediately challenge the repeal. The lawsuits will likely argue that the EPA acted arbitrarily and capriciously. That it based its decision on flawed science. That it violated administrative law requirements. That it acted contrary to the statute. Multiple lawsuits will be filed in different federal circuit courts, and they'll start working their way through the system.

The first question any court will ask: did the EPA follow the right procedure? Administrative law requires agencies to base decisions on the evidence in the record, to explain their reasoning, and to respond to significant comments. If the EPA repealed the endangerment finding based on a report that a judge already found was compiled illegally, that's a problem. If the EPA ignored peer-reviewed climate science and relied on fringe arguments, that's a problem.

On these procedural grounds, the EPA's rollback is vulnerable. The science arguments are weak. The Clean Air Act arguments don't hold up. The regulatory process was rushed. Courts applying the standard administrative law test might find the rollback was arbitrary and capricious. That means the endangerment finding gets restored.

But the Supreme Court is a complicating factor. The current Court has shown skepticism toward environmental regulation and deference toward executive branch decisions. In recent cases, the Court has embraced interpretations of environmental law that curtail EPA authority. The case of West Virginia v. EPA specifically limited the EPA's authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants under a particular provision of the Clean Air Act.

So the appellate process is unpredictable. A lower court might reject the rollback as arbitrary. But if the case reaches the Supreme Court, the outcome is less certain. The Court might uphold the rollback, or it might reject it, or it might narrow the endangerment finding's scope.

The most likely scenario is years of litigation. Cases in different circuits. Conflicting rulings. Petitions for Supreme Court review. Some courts upholding the rollback, others rejecting it. That's the Balkanization of climate law that nobody actually wants. But it's where we're headed.

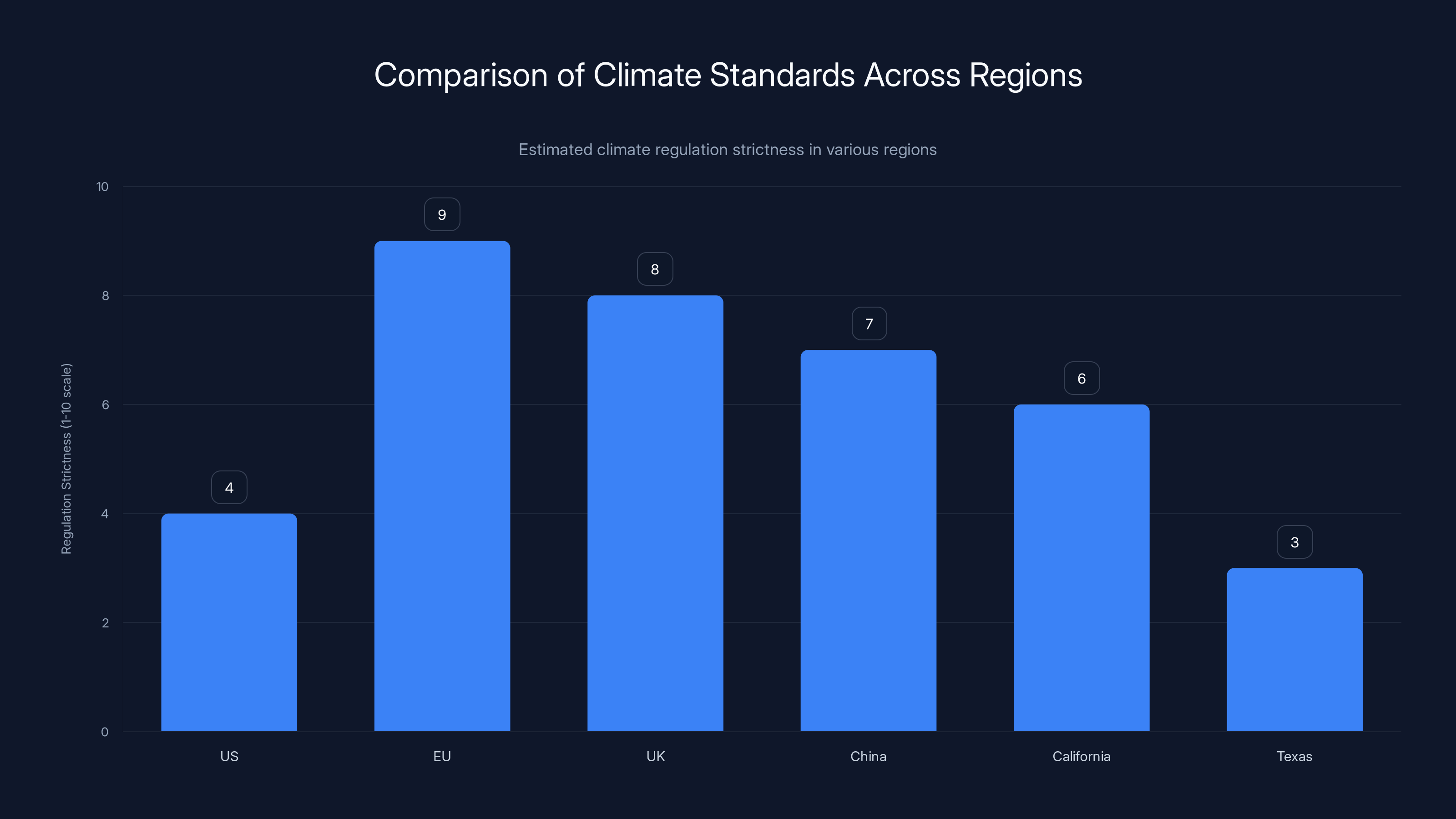

And during all those years, businesses face uncertainty. States are already stepping in with their own regulations. California has nearly EPA-level authority over emissions. New York is doing the same. If the federal government withdraws, a patchwork emerges. Companies have to comply with multiple standards in multiple jurisdictions.

This is actually worse for business than a single federal standard, even a strict one. Uniform rules are cheaper to comply with than fragmented rules. But that's the consequence of dismantling federal authority. You don't get deregulation. You get re-regulation by 50 different states.

The Scientific Arguments Will Collapse in Court

Let's be direct: the science arguments in the rollback proposal are bad. They'll be eviscerated in court.

The Department of Energy report that the administration relies on was authored by known climate contrarians. It cherry-picked data, misrepresented peer-reviewed studies, and ignored the broader scientific consensus. When scientists whose work was cited in the report reviewed it, they complained that their findings had been misused.

A federal judge has already ruled that the committee that produced the report was assembled illegally. That's not a good sign for the administration's case. When you go to court and argue that the EPA's decision is based on X report, and a judge has already found that report was produced illegally, you've got a credibility problem.

Climate science itself is not in doubt. The consensus is overwhelming. Temperature is rising. The rise is caused by greenhouse gas emissions. The consequences will be serious. Multiple lines of evidence support these conclusions. No peer-reviewed scientific study contradicts the basic findings. The argument that climate science is too uncertain to regulate is false.

A court examining the science will ask: what does the peer-reviewed literature say? And the answer is unambiguous. Greenhouse gases cause warming. The endangerment finding is correct. The administration's arguments to the contrary are fringe positions rejected by the scientific community.

Now, judges aren't scientists. They can't independently verify climate science. But they can ask: does the scientific consensus support the EPA's findings? The answer is yes, overwhelming yes. Does the administration's contrary evidence come from credible sources? No, it comes from known contrarians and a report already found to be illegally assembled.

On the science, the administration will lose. Experts predict this with high confidence. The question is which court will rule first and what the Supreme Court will do on appeal.

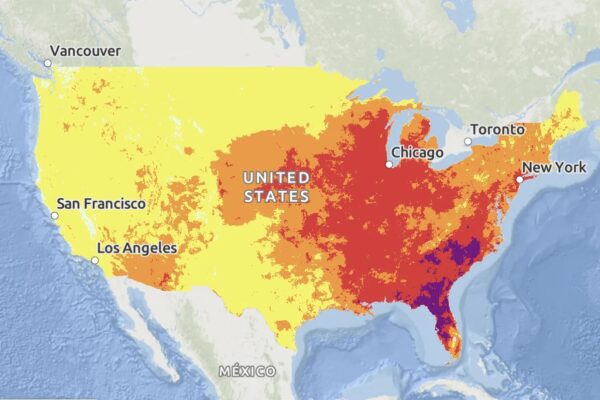

Estimated data shows that the EU and UK have stricter climate regulations compared to the US, with California having stricter standards than Texas.

What Happens to State Climate Action if the Endangerment Finding Is Gone?

Here's an often-overlooked consequence: if the endangerment finding is repealed, state climate action becomes more important and more complicated.

States have always had authority to regulate emissions within their borders. They can impose stricter standards than federal law allows. Many states have done exactly that. California's vehicle emissions standards are stricter than federal standards. New York has aggressive climate goals. Dozens of states have renewable energy standards.

But states are always vulnerable to federal preemption. If the EPA says "we have authority over this," states sometimes have to back down. The Clean Air Act gives the EPA clear authority to regulate air pollution. States can do more, but they can't do less.

Now, if the endangerment finding is gone, the EPA's authority to regulate greenhouse gases is questioned. That might actually expand state authority. If the federal government isn't regulating emissions, states can. This could push more aggressive state-level climate action.

But it also creates chaos. Fifty states developing their own standards is inefficient. Companies have to comply with different rules in different places. Supply chains become more complicated. California and New York set strict standards. Texas and Wyoming set looser standards. The Northeast and West Coast develop their own climate frameworks. The South develops something different.

For major companies operating across state lines, this is a nightmare. They want to know the rules. One federal standard is better than fifty state standards, even if the federal standard is strict.

So the consequence of repealing the endangerment finding might be exactly the opposite of what the administration intends. Instead of less climate regulation, you get more regulation, just fragmented across states. Instead of certainty, you get chaos. Instead of business-friendly deregulation, you get the worst of both worlds: multiple overlapping standards with no clear hierarchy.

The administration might find that destroying federal climate authority actually increases the burden on business in the long run.

How Climate Litigation Changes Without Federal Authority

One of the biggest wild cards in the endangerment finding saga is state and local climate litigation.

Cities and states have filed dozens of lawsuits against fossil fuel companies, alleging they knowingly misled the public about climate science and should pay for climate damages. These lawsuits raise novel legal questions. Can a city sue a company for contributing to global warming? What legal theory supports that claim? Can you draw a line from a specific company's emissions to a specific community's damages?

The oil industry's defense, as mentioned earlier, has been federal preemption. The EPA has authority over climate change. States can't also regulate it. Therefore, state courts can't hear climate lawsuits. Federal authority preempts state law.

This defense is strong. Several courts have found it persuasive. But it depends entirely on the EPA having authority to regulate greenhouse gases. If the endangerment finding is repealed and the EPA's authority is questioned, the preemption defense falls apart.

Suddenly, state climate lawsuits become viable in a way they weren't before. If the federal government isn't regulating emissions, states can. And if states can regulate emissions, they can certainly allow their citizens to sue for climate damages. The legal pathway opens up.

This is potentially catastrophic for the oil industry. Massive liability in multiple states, with no clear federal preemption defense. Companies face jury trials in California, New York, Vermont, and other hostile jurisdictions. The damages could be huge. The litigation costs would be staggering.

So again, the intended consequence of the rollback might be the opposite of what's intended. Instead of helping the oil industry, repealing the endangerment finding might unleash climate litigation that the industry can't defend against.

The industry knows this. That's why the American Petroleum Institute asked the EPA to preserve the finding for at least some sources. The industry is trying to save itself from its own side's ideological ambitions.

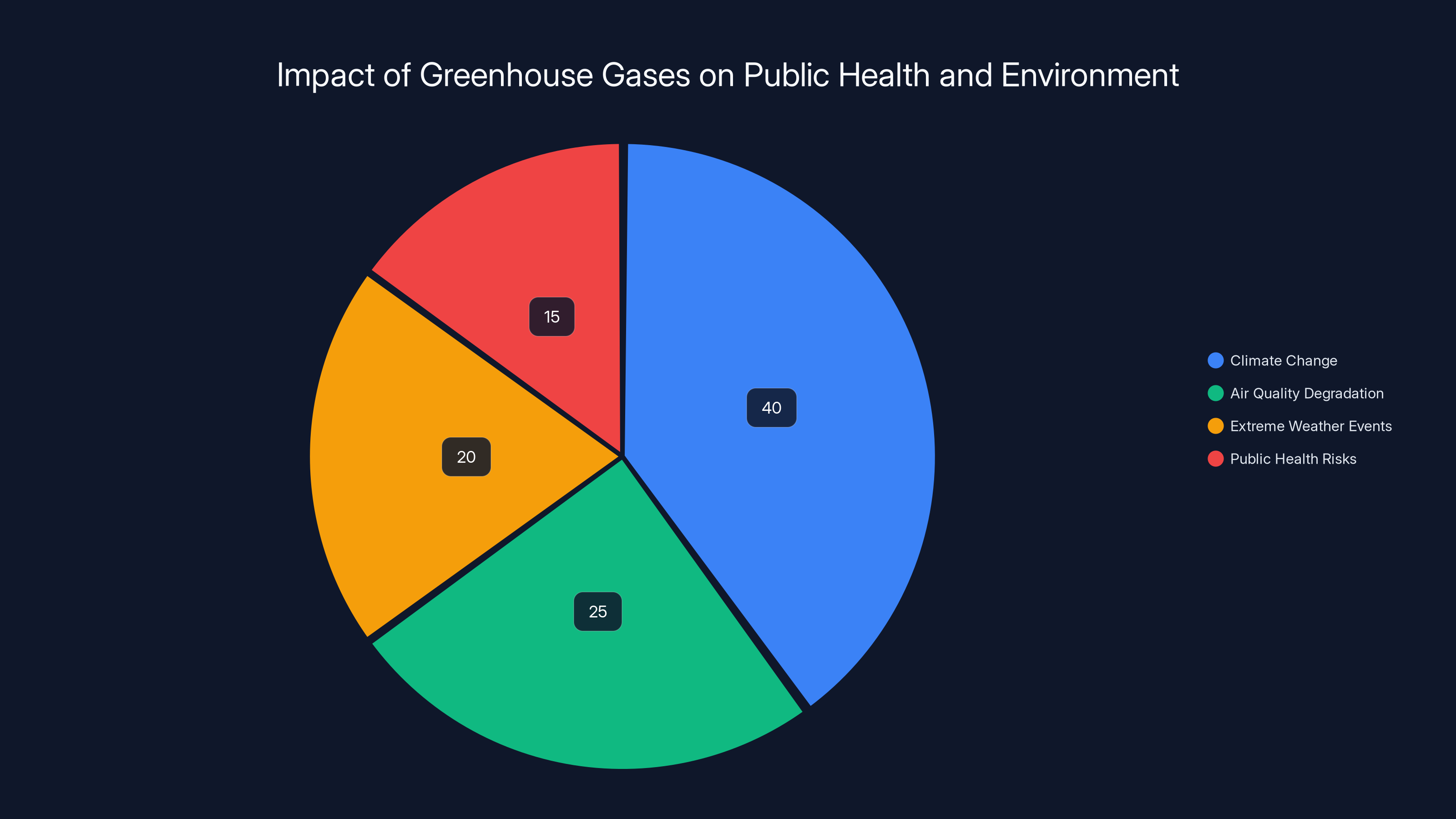

The EPA's Endangerment Finding highlights that greenhouse gases significantly contribute to climate change (40%), degrade air quality (25%), increase extreme weather events (20%), and pose public health risks (15%). Estimated data.

The Broader Regulatory Uncertainty Problem

Beyond the specific issues of climate regulation, oil liability, and automotive standards, there's a deeper problem: regulatory certainty.

Business hates uncertainty more than it hates regulation. A company can adapt to strict rules. What it can't adapt to is not knowing what the rules will be. Strict rules you can build around. Changing rules you can't.

The endangerment finding rollback creates massive uncertainty. It signals that regulatory foundations that have stood for 15 years can be dismantled. What other regulations are vulnerable? Are EPA authorities in general on shakier ground now? If climate regulation can be eliminated, what about clean air standards for other pollutants? Clean water regulations? Financial regulations?

Investors need to know what rules will govern their investments for the next 10 to 20 years. When those rules suddenly become uncertain, investment slows down. Companies hold back on expansion. They delay retooling factories. They avoid long-term commitments.

This is particularly true for capital-intensive industries like energy and automotive. A company building a new plant is committing billions of dollars. They need to know the regulatory environment for decades. The endangerment finding rollback introduces doubt. It suggests that regulatory foundations can change quickly. That makes long-term planning impossible.

The result, counterintuitively, might be economic contraction rather than growth. Instead of businesses celebrating deregulation and investing aggressively, they pull back, afraid of what the next shift might bring. Certainty beats deregulation when you have to plan for the long term.

This is the hidden cost of the administration's approach. It's not just about climate. It's about the broader framework of business regulation. If the administration can dismantle 15-year-old regulatory foundations, what's safe? The answer, increasingly, is nothing. And that creates a chilling effect on investment and expansion.

What the Courts Will Actually Focus On

When this case reaches federal courts, judges won't spend much time debating climate science directly. That's not the judge's job. The judge's job is to decide whether the EPA followed the law and its own procedures.

The key legal questions will be: Did the EPA have a rational basis for repealing the endangerment finding? Did the EPA rely on evidence in the administrative record? Did the EPA respond to major comments? Did the EPA's reasoning withstand scrutiny?

On these questions, the EPA's case is weak. The agency relied on a report that was legally defective. It cherry-picked science. It ignored contrary evidence. It made arguments that contradict the plain language of the Clean Air Act. A judge applying the standard for arbitrary and capricious action will likely find the repeal meets that standard.

But here's where the Supreme Court matters. The current Court has been skeptical of environmental regulations and deferential to executive decisions. In recent cases, the Court has narrowed EPA authority. The Court might decide that even if the repeal process was flawed, the Court won't second-guess the EPA's judgment about what the law allows.

Or the Court might focus on a different question: does the Clean Air Act actually give the EPA authority to regulate greenhouse gases at all? The text says the EPA can regulate "air pollutants." Are greenhouse gases air pollutants? Textually, the answer is yes. They're gases in the air, and they pollute the atmosphere. But the Court might adopt a different interpretation.

The most likely outcome is that lower courts reject the rollback as arbitrary and capricious. The endangerment finding gets restored. But the case goes to the Supreme Court, where the outcome is less predictable. The Court might uphold the lower courts, or it might surprise everyone and validate the EPA's repeal.

This uncertainty itself is a major problem. Companies and states need to know the legal status of climate regulation. Instead, they're getting years of litigation with unpredictable outcomes.

The International Dimension: US Climate Credibility at Stake

Outside the US legal system, there's another consequence that gets less attention: America's climate credibility on the global stage.

The US committed to the Paris Agreement. It pledged to reduce emissions. International partners expect the US to follow through. When the US starts dismantling its own climate regulations, it sends a message: climate commitments are temporary. They depend on who's in power.

This undermines the international climate framework. Other countries ask: why should we commit to climate reductions if the US might just abandon them in the next election? The result is slower progress globally. Weaker commitments. Less confidence in collective action.

For companies operating internationally, this is another complication. They navigate different climate policies in different countries. The EU has aggressive climate standards. Britain has climate commitments. China is investing in renewables, partly due to climate concerns. But the US, which should be leading, is instead dismantling its regulatory framework.

This creates a strange dynamic where US companies might face stricter standards in Europe and Asia than they do at home. A US automaker selling vehicles in California will face stricter standards than a vehicle sold in Texas. A US oil company operating internationally will face stricter climate regulations in Europe than in the US.

Over time, this incentivizes US companies to move emissions-intensive operations outside the US. Why operate under strict rules here when you can operate under looser rules elsewhere? The result is a hollowing out of domestic industry. And ironically, global emissions don't decrease, because the dirty operations just move to another country.

This is the perverse logic of unilateral deregulation in a globalized world. You can't eliminate climate regulations. You can only move them around. And if the US moves them to other countries, the US loses the ability to set global standards.

What Happens to the Broader EPA Authority After This?

If the endangerment finding is successfully repealed, it sets a precedent for attacking other EPA authorities.

The EPA's authority to regulate air pollution comes from Congress. Congress said: regulate pollutants that harm public health. The EPA issued findings for various pollutants. Those findings are now the foundation for regulations. If the endangerment finding can be dismantled, so can findings for other pollutants.

Why not repeal the findings for nitrogen oxides? Particulate matter? Sulfur dioxide? If the science can be challenged for greenhouse gases, it can be challenged for other pollutants. The legal machinery for attacking EPA authority becomes available for any regulation the administration dislikes.

The result is that the EPA becomes a weaker agency. It can't rely on its own findings to support regulations. Any finding is vulnerable to attack. Any regulation can be challenged as based on flawed methodology or insufficient evidence.

This might sound like a victory for deregulation. In fact, it's the opposite. It creates uncertainty about everything the EPA does. Water quality standards, air quality standards, hazardous waste regulations. Everything is potentially vulnerable.

Agencies need the ability to make findings and issue regulations. If those foundations are constantly under attack, the agency becomes paralyzed. It can't plan long-term. It can't enforce consistently. It can't improve based on new evidence.

For business, weaker agency authority means weaker regulatory standards, but also less certainty about what the standards are. It's not clearly better for business. It's just more chaotic.

The broader lesson is that attacking the endangerment finding has consequences that ripple through the entire regulatory system. It's not a targeted fix. It's a destabilization of how environmental law works in America.

Timeline: When Will We Actually Know the Outcome?

Assuming the rollback proceeds, here's a realistic timeline for the fight.

2024-2025: The EPA formally repeals the endangerment finding. Environmental groups and states file lawsuits in multiple federal courts.

2025-2026: Federal district courts hear the cases. Early rulings come down. Some courts might temporarily restore the finding, stopping the rollback pending litigation.

2026-2027: Appeals courts hear the cases. Different circuit courts might reach different conclusions. Some ruling the rollback valid, others ruling it invalid.

2027-2028: The Supreme Court petitions the circuit splits reach the Court. The Court decides whether to hear the case.

2028-2029: If the Court hears the case, oral arguments happen. The decision comes down. Depending on the Court's ruling, the endangerment finding is either restored or remains repealed.

So a realistic timeline is 4 to 5 years before we have clarity. During all that time, regulation is uncertain. Companies don't know what the rules will be. States are trying to figure out how much authority they have. Litigation is expensive and unpredictable.

This is the cost of the legal fight. Not just the outcome, but the years of uncertainty while the fight plays out.

What Environmental Groups and States Are Doing

Environmental organizations and progressive states aren't passive in this fight. They're preparing multiple strategies.

Litigation is the obvious one. Lawsuits will challenge the rollback on multiple grounds. Some focus on Clean Air Act issues. Others focus on administrative law problems with how the EPA conducted the rulemaking. Still others challenge the EPA's reliance on flawed science.

But litigation alone isn't enough. States are also moving proactively. California, New York, and other states are implementing their own climate regulations. They're setting standards that exceed what the federal government is doing. They're using state authority to fill the gap if federal authority disappears.

Some states are also filing amicus briefs in the litigation, supporting challenges to the rollback. They're arguing that repealing the endangerment finding harms their interests. It creates uncertainty for business operating in their states. It undermines state climate programs. It should be blocked.

Environmental groups are also mobilizing their membership, lobbying Congress, and building public pressure. They're highlighting how the rollback hurts public health. They're pointing out that air pollution from fossil fuels kills tens of thousands of Americans every year. Repealing climate regulations means more pollution, more deaths, more suffering.

But here's the thing: Congress is unlikely to help. The current Congress is controlled by Republicans who support the rollback. Democrats are in the minority. There's no legislative fix coming. Environmental groups and states have to fight in courts and in the regulatory process.

This asymmetry matters. The administration can dismantle regulations relatively easily. Rebuilding them is much harder. You have to pass legislation, or win in courts, or win elections. All of that takes time and is difficult.

The Ultimate Outcome: Uncertainty Is the Only Certainty

Here's what we can predict with confidence: we don't know the ultimate outcome.

The endangerment finding might be fully repealed. Or it might be partially preserved. Or it might be restored by courts. Or the Supreme Court might issue a ruling that splits the difference. Or the next administration might re-establish the finding. Or Congress might act.

The only certainty is that we're in for years of legal and regulatory chaos. That chaos will affect how companies invest. It will shape how states develop climate policy. It will influence how environmental groups litigate. It will impact how people understand their government's relationship to climate change.

What we do know is that the fight over climate regulations is just beginning. This isn't the end. It's the start of a long battle that will reshape American climate law. The endangerment finding, which seemed unassailable just a few years ago, turns out to be vulnerable. And everything that depends on it is now in question.

For anyone trying to understand American environmental policy, this moment is crucial. The rules that have governed climate regulation for 15 years are being challenged. The legal foundations are being questioned. The science is being disputed. The outcome will determine whether America can regulate greenhouse gases at all.

That's what makes this fight so consequential. It's not just about tweaking a regulation. It's about whether the federal government has the power to address climate change. And that answer will shape the next generation of climate law and policy.

FAQ

What exactly is the endangerment finding and why is it important?

The endangerment finding is a 2009 EPA determination that greenhouse gas emissions from human activities pose a threat to public health and welfare. It's important because it provides the legal foundation for the EPA to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act. Without it, the EPA's authority to regulate emissions is questionable, and nearly all federal climate regulations issued since 2009 lose their legal basis.

How did the endangerment finding come about?

The endangerment finding emerged from the 2007 Supreme Court decision Massachusetts v. EPA, where the Court ruled that the EPA had to either regulate greenhouse gases or provide a scientific basis for not doing so. The Bush administration initially resisted acknowledging the science, but under the Obama administration in 2009, the EPA formally issued the endangerment finding based on peer-reviewed climate science.

Why is the oil industry opposed to repealing the endangerment finding?

This is counterintuitive, but oil companies have come to rely on the endangerment finding for legal protection. They use the federal government's climate authority as a defense against state and local climate lawsuits, arguing that states can't sue for climate damages because the federal government regulates greenhouse gases. Repealing the finding would remove this defense and expose oil companies to massive climate liability in multiple states.

What are the main legal arguments the EPA is making to justify the rollback?

The EPA is using several arguments: that greenhouse gases are global pollutants outside the EPA's jurisdiction, that climate science is too uncertain to regulate, that the costs of regulation exceed the benefits, and that Congress never intended the Clean Air Act to apply to greenhouse gases. Legal experts consider all of these arguments weak and predict they will fail in court.

How long will the legal fight over the endangerment finding take?

A realistic timeline is 4 to 5 years before the Supreme Court issues a final decision. Lower courts will rule first, probably rejecting the rollback. Then appeals courts will get involved, potentially with conflicting decisions. Finally, the Supreme Court will need to resolve the conflict. Throughout this period, regulation remains uncertain.

What will happen to state climate regulations if the endangerment finding is repealed?

If the federal endangerment finding is repealed, states will likely expand their own climate regulations to fill the gap. This could actually lead to stricter climate standards in some places, as California, New York, and other progressive states impose their own rules. The result would be a patchwork of state standards rather than a unified federal approach, which is more complicated and expensive for businesses to navigate.

Can Congress do anything to protect the endangerment finding?

Congressionally, there are limited options. Congress could amend the Clean Air Act to explicitly authorize EPA regulation of greenhouse gases, but that would require passing new legislation through both chambers and getting past a presidential veto. The current Congress is unlikely to do this. The more likely remedy is court action.

What would repealing the endangerment finding mean for carbon emissions and climate change?

Repealing the endangerment finding wouldn't eliminate all climate policy. States would likely increase their own regulations, and international companies would still face climate requirements in other countries. But federal authority to regulate emissions would be weakened, potentially slowing the transition to clean energy and making it harder to meet international climate commitments. Global emissions might not decrease, but would instead be regulated less uniformly.

The Path Forward: Prepare for Years of Uncertainty

For businesses, policymakers, and citizens trying to understand what comes next, one message is clear: prepare for uncertainty.

The endangerment finding is foundational to American climate law. Dismantling it doesn't just change one rule. It upends the entire framework. For the next several years, maybe the next decade, the legal status of climate regulation will be in flux.

Companies should think about their regulatory exposure. What happens if climate regulations disappear? What if they get stronger? What if different states impose conflicting standards? Having a plan for multiple scenarios is wise.

States should accelerate their own climate programs. If federal authority is in question, state authority matters more. States that want to pursue climate action should do it now, before legal uncertainty paralyzes decision-making.

Environmental groups should prepare for a long legal fight. Courts move slowly. The Supreme Court is conservative. Victory isn't assured. But the arguments for climate regulation are strong, and the alternative is basically unlivable. The fight is worth pursuing.

For the rest of us, this is a reminder that environmental law isn't settled. It's contested. It's political. It's vulnerable. And the foundations we thought were solid can shift suddenly. That's both sobering and a call to action. Climate change won't wait for legal certainty. We need to move forward even amid uncertainty, using whatever authority is available, building coalitions, and pushing for the changes we need.

The fight over climate rules is just beginning. And for the next 4 to 5 years, or longer, we'll be living in its shadow.

Key Takeaways

- The endangerment finding is the legal foundation for all federal climate regulation since 2009. Repealing it would dismantle EPA authority to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act.

- Right-wing groups spent 15+ years planning this rollback using weak legal arguments that climate scientists and legal experts predict will fail in court.

- Oil companies paradoxically oppose the rollback because they depend on federal climate authority as a defense against state and local climate lawsuits that could cost billions.

- Automakers face manufacturing uncertainty because they can't plan long-term investment without knowing what emissions standards will govern vehicle production.

- The legal fight will likely take 4 to 5 years to resolve through multiple courts before reaching the Supreme Court, creating prolonged regulatory uncertainty for business and government.

Related Articles

- EPA Revokes Climate Endangerment Finding: What Happens Next [2025]

- Judicial Body Removes Climate Research Paper After Republican Pressure [2025]

- Climate Science Removed From Judicial Advisory: What Happened [2025]

- COVID-19 Cleared Skies but Supercharged Methane: The Atmospheric Paradox [2025]

- 2026 Winter Olympics Environmental Impact: Snowpack Loss and Climate Crisis [2025]

- Hair Sample Study Proves Leaded Gas Ban Worked [2025]

![The Endangerment Finding Battle: US Climate Rules Uncertainty [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-endangerment-finding-battle-us-climate-rules-uncertainty/image-1-1770894490440.jpg)