EPA Revokes Climate Endangerment Finding: What Happens Next [2025]

The Trump administration just pulled the legal rug out from under decades of climate regulation in the United States. In early 2025, the EPA formally revoked the scientific finding that greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare. On the surface, this looks like a denial of climate science. But here's what actually happened: this is a legal maneuver, not a scientific one. The Trump administration isn't claiming climate change isn't real. They're claiming the EPA never had the power to regulate greenhouse gases in the first place, as detailed in the Invading Sea.

This distinction matters enormously. It changes everything about how the climate debate moves forward legally, politically, and scientifically.

We're living through three of the warmest years on record. Hurricanes are intensifying faster than they did forty years ago. Wildfire seasons are extending. Heat waves are killing people. And yet, at the precise moment when climate impacts are hitting hardest, the federal government is stepping back from its legal authority to control greenhouse gas pollution, as reported by NPR.

But here's the thing: this decision doesn't erase climate science. It doesn't make the science go away. What it does is force a reckoning with a fundamental question that's been brewing for years: does the EPA have the constitutional power to regulate carbon emissions under the Clean Air Act? The Supreme Court will almost certainly have to answer that question. And when it does, the stakes will be massive.

This article walks through what just happened, why it happened, and where the legal and political battle heads next. We'll look at the scientific reality that the Trump administration is sidestepping, the legal framework they're attacking, the state responses that are already mobilizing, and the Supreme Court showdown that almost certainly awaits.

TL; DR

- The Core Move: The EPA revoked a 17-year-old finding that greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare, eliminating the agency's legal basis to regulate carbon under the Clean Air Act.

- It's Legal, Not Scientific: The Trump administration isn't denying climate science—they're claiming the EPA lacks the authority to regulate greenhouse gases, a constitutional argument.

- States Are Fighting Back: Democrat-led states and environmental groups have already vowed to challenge the revocation in federal court, likely heading to the Supreme Court.

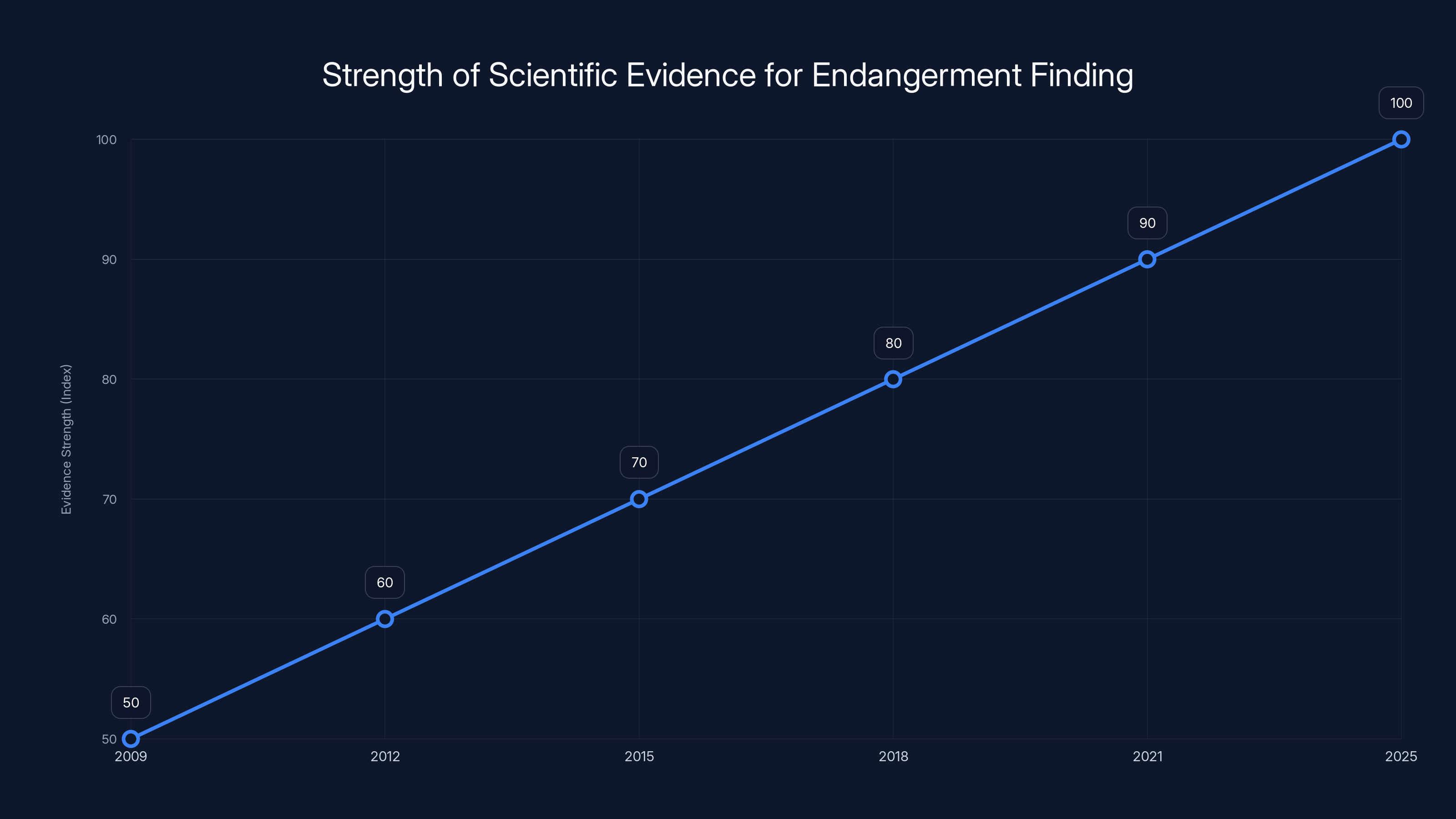

- Science Says Otherwise: The National Academies of Sciences confirms the endangerment finding is supported by stronger evidence now than it was in 2009.

- What's at Stake: This could reshape how the federal government approaches pollution control for decades and set a precedent for deregulation across industries.

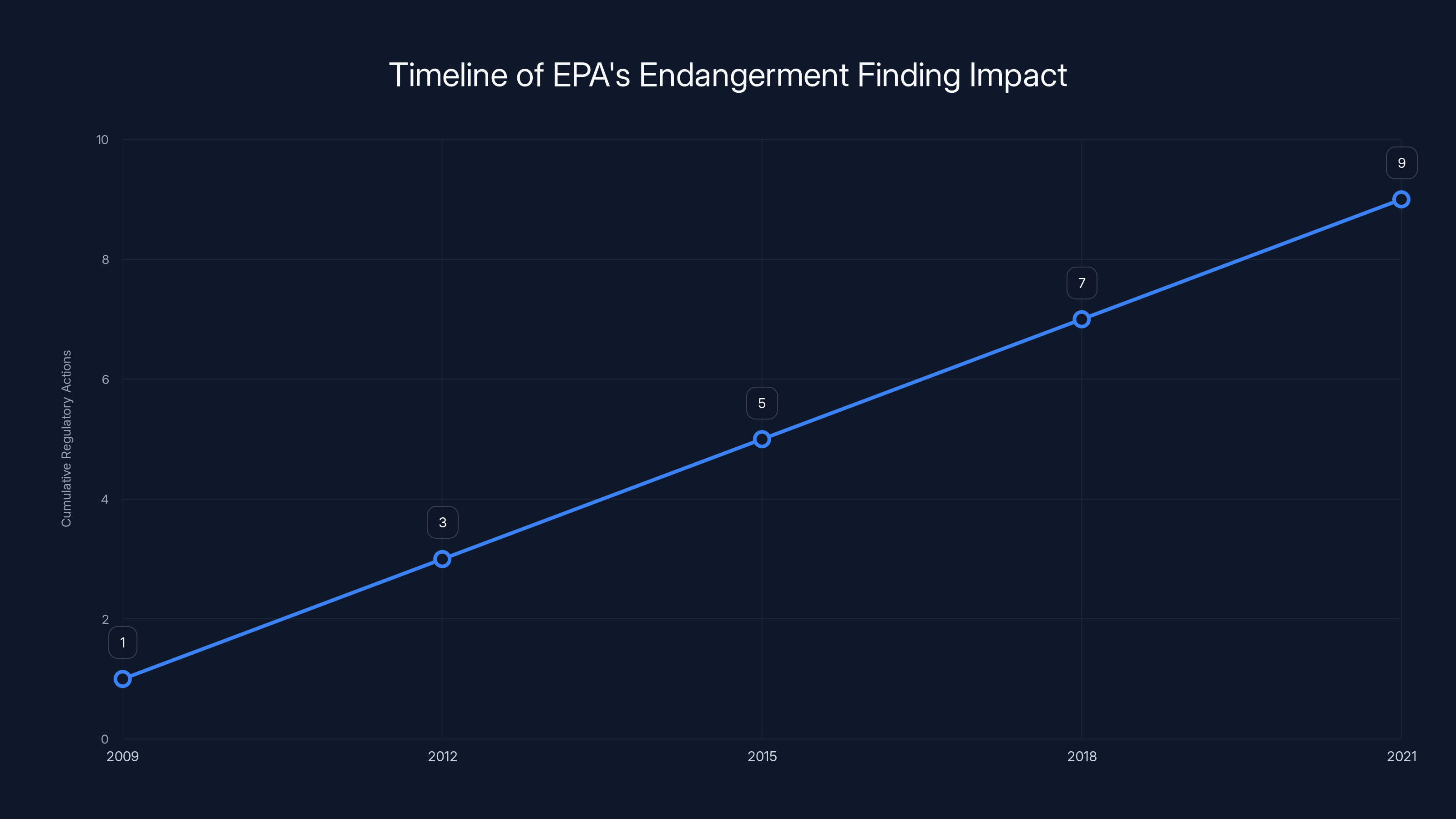

The Endangerment Finding led to a steady increase in regulatory actions by the EPA from 2009 to 2023. Estimated data shows key milestones in fuel efficiency, methane regulation, and emission standards.

The 17-Year Finding That's Now Extinct

Let's start with what the Trump administration just killed. In December 2009, the EPA under President Barack Obama issued something called the "Endangerment Finding." This wasn't poetry. It was a technical document, about eighty pages long, concluding that greenhouse gases pose a danger to public health and welfare.

That finding was the legal foundation for everything the EPA did on climate change for the next sixteen years. Every fuel efficiency standard. Every methane regulation for oil and gas companies. Every power plant emissions limit. Every vehicle emission standard. All of it traced back to that finding.

Here's why the finding mattered legally: the Clean Air Act gives the EPA power to regulate pollutants that "may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare." Once the EPA made the endangerment finding, they had a clear legal mandate. Congress had written the statute. The EPA had made the factual determination. Now they could regulate.

The finding itself was based on peer-reviewed science. The EPA evaluated thousands of studies. They looked at data from the National Center for Atmospheric Research, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and dozens of universities. They consulted with the National Academies of Sciences. Every line of evidence pointed the same direction: greenhouse gases are changing the atmosphere, and those changes harm human health and ecosystems.

But here's what made the finding vulnerable legally: it was based on a 2007 Supreme Court decision called Massachusetts v. EPA. In that case, the Court ruled that the EPA could regulate greenhouse gases as pollutants under the Clean Air Act. Four justices on that Court have since retired or died. The current Court looks fundamentally different.

The 2009 finding also happened to be issued by an agency led by a Democratic appointee, under a Democratic president. That made it a target. For the better part of sixteen years, Republican administrations and fossil fuel companies argued the finding was wrong or at least questionable. The Trump administration took a different approach: they didn't argue the science was wrong. They argued the EPA had no power to make the finding at all, as discussed in E&E News.

Estimated data shows that while deregulation may appear cheaper initially, long-term costs due to pollution and climate impacts surpass those of maintaining regulations.

Why This Is Legally Bold (and Legally Risky)

The Trump administration's argument is deceptively simple: the EPA doesn't have the power to make endangerment findings for greenhouse gases. The agency exceeded its constitutional authority. Therefore, the finding is void.

This is a much more radical argument than saying "the finding is scientifically wrong." If the administration had argued the science was flawed, they'd have to counter-argue the National Academies of Sciences. They'd have to explain why three of the warmest years on record weren't relevant to public health. They'd have to grapple with attribution science that can now link specific extreme weather events to climate change.

Instead, they're sidestepping the science entirely. They're saying the EPA is acting outside its authority.

Legally, there's a precedent for this kind of argument. The Supreme Court has been skeptical of "broad" EPA powers in recent years. In 2022, the Court ruled in West Virginia v. EPA that the agency had overreached when trying to regulate greenhouse gases from power plants under a specific section of the Clean Air Act. That decision suggested the Court was willing to constrain EPA authority.

But there's a crucial difference. West Virginia involved one specific statute. The endangerment finding is broader. It's the EPA's determination that a certain class of pollutants endangers public welfare. That's a fact-finding exercise. The Clean Air Act explicitly authorizes the EPA to make such findings.

The strongest argument the Trump administration has is what's called "the major questions doctrine." This legal principle holds that when a statute's interpretation would give an agency vast new powers, courts should require Congress to speak clearly. Regulating greenhouse gases touches the entire economy. That might count as a "major question" requiring explicit Congressional authorization.

But there's a counter-argument just as strong: Congress already spoke clearly. The Clean Air Act says the EPA can regulate pollutants that endanger public health. Greenhouse gases demonstrably endanger public health. The statute is explicit. No major questions doctrine applies.

When this case reaches the Supreme Court—and it almost certainly will—the outcome is genuinely uncertain. The current Court is more conservative than the one that decided Massachusetts v. EPA. But the statute language is clear. The scientific evidence is stronger now than in 2009. And even conservative judges might hesitate to read the Clean Air Act so narrowly that it excludes the most significant air pollutant of our time.

The Science That Nobody's Actually Disputing

Here's what's remarkable about this moment: the Trump administration isn't really disputing the underlying science. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin didn't argue that greenhouse gases don't warm the atmosphere. He didn't claim that extreme weather isn't increasing. His argument is purely legal: the EPA has no power to regulate based on that science.

The scientific evidence for the endangerment finding has only gotten stronger since 2009. Back then, the EPA was relying on projections and modeling. We were watching climate change unfold. Now, we're living in it.

The National Academies of Sciences convened a panel and issued a report specifically on the endangerment finding. Their conclusion was blunt: "The evidence for current and future harm to human health and welfare created by human-caused greenhouse gases is beyond scientific dispute." They noted that observational records are now longer. Multiple new lines of evidence have emerged. The scientific case is stronger, not weaker.

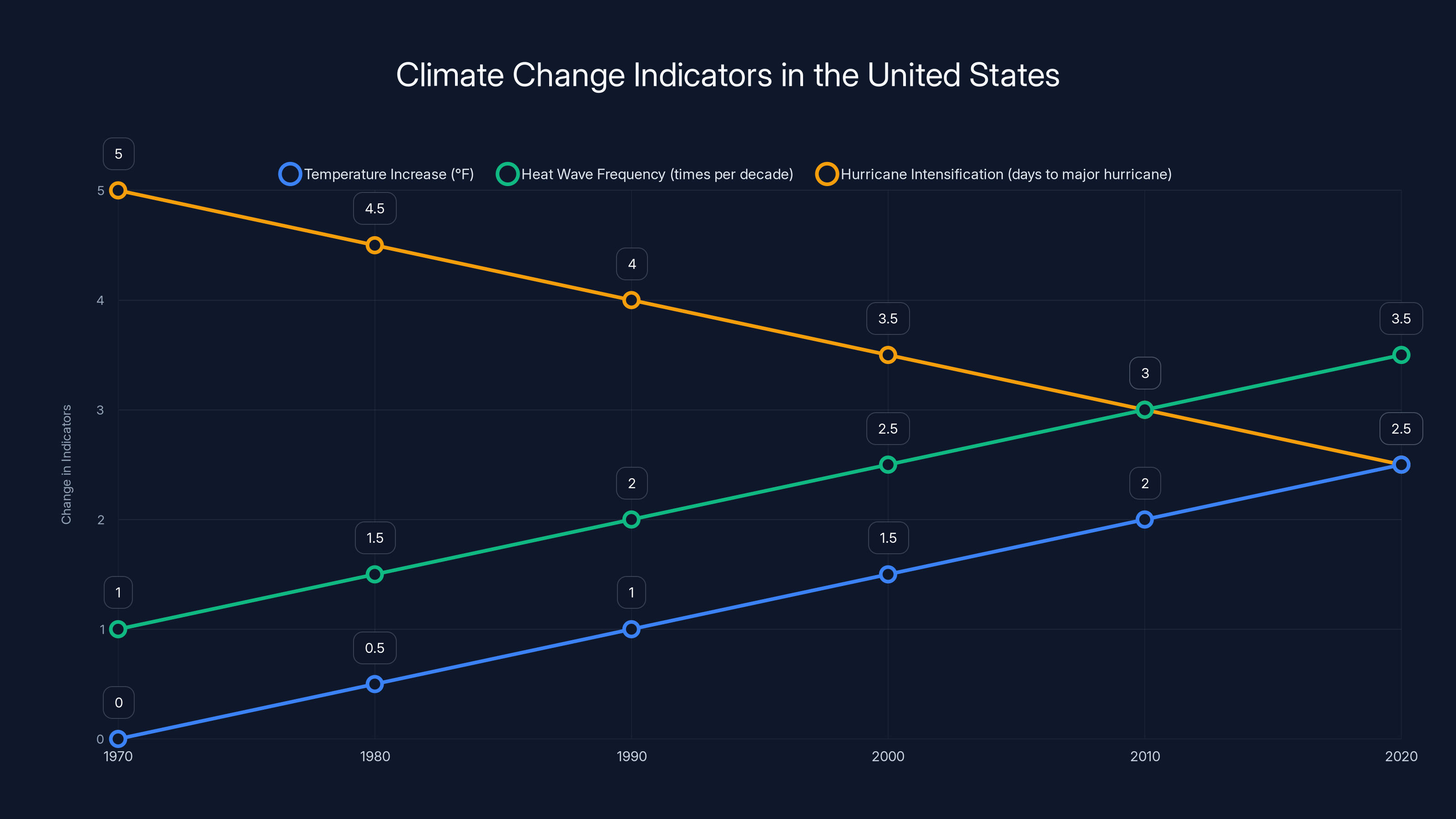

Consider what's changed since 2009. Temperatures in the contiguous United States have risen 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit since 1970. That's marked acceleration compared to the 20th century baseline. Heat wave frequency has tripled since the 1960s. Storms are producing more intense rainfall. Hurricanes are intensifying more rapidly—the average time from tropical storm to major hurricane has shrunk. They also break up more slowly, extending rain and wind impacts.

Wildfires have become more severe. The science of attribution—linking specific extreme weather events to climate change—has advanced dramatically. Scientists can now say with confidence that Hurricane Helene's flooding in North Carolina, the Los Angeles wildfires, and the catastrophic flooding in Texas were shaped by climate change.

That's not speculation. That's not modeling. That's observed reality backed by physical analysis.

The National Academies report also noted something important: the Trump administration never asked for their scientific input. The Clean Air Act actually requires the EPA to consult with the National Academies on scientific matters. The Trump EPA skipped that step. The National Academies had to fast-track their own report on their own dime just to get the science on the record before the repeal was finalized.

Phil Duffy, chief scientist at Spark Climate Solutions and a former top science adviser to President Biden, made a crucial point: "The evidence for societal harms from greenhouse gas emissions has become more of a present day reality than something that's predicted and expected." In 2009, the EPA was relying heavily on future projections. Now we're watching the harms unfold in real time.

Joseph Goffman, who served as the EPA's top air quality official under Biden, called the revocation "a fundamental betrayal of EPA's responsibility to protect human health. It is legally indefensible, morally bankrupt, and completely untethered from the scientific record."

He's right about one thing: the revocation is untethered from the scientific record. The Trump administration isn't contesting the science. They're just saying it doesn't matter, legally speaking. The EPA has no authority to act on it.

Estimated data shows a clear trend of increasing temperatures, more frequent heat waves, and faster hurricane intensification since 1970.

The Clean Air Act's Awkward Text

Understanding this battle requires wading into statutory language. That's not fun, but it's important because the statute itself is actually pretty clear, and that clarity is a problem for the Trump administration.

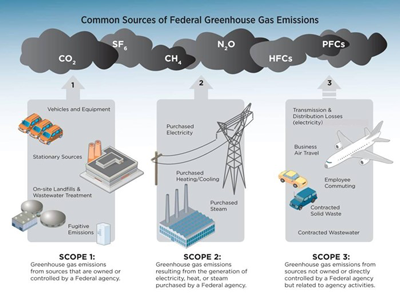

Section 202 of the Clean Air Act says the EPA must set emissions standards for new motor vehicles if the administrator determines that pollutant emissions "may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare." Section 111 applies similar logic to stationary sources like power plants and factories.

That's it. That's the authority. The statute doesn't distinguish between traditional pollutants and greenhouse gases. It doesn't say the EPA can regulate particulate matter but not carbon dioxide. Congress wrote a general statute, and the EPA is supposed to apply it to whatever pollutants are causing harm.

The problem—from the Trump administration's perspective—is that Congress wrote the statute in 1970. Back then, nobody was thinking about global greenhouse gases. Congress was focused on smog, soot, acid rain, and local air pollution. The statute is a blunt instrument, written before anyone imagined it would be applied to the entire global carbon cycle.

But statutory interpretation doesn't allow courts to rewrite laws because Congress didn't anticipate every application. Courts apply the statute as written. And as written, the Clean Air Act gives the EPA exactly the power the Trump administration says it doesn't have.

The Trump administration's legal strategy is to invoke the "major questions doctrine." Here's how it works: when a statute's application would raise questions of vast economic or political significance, courts sometimes require that Congress speak with exceptional clarity. The idea is that Congress probably wouldn't intend to give agencies power over such major questions through general language.

Regulating the entire economy's greenhouse gas emissions is definitely a major question. But there's a countervailing principle: when courts find that statutory language is clear, they can't invoke the major questions doctrine to override it. The statute has to be ambiguous for the doctrine to apply.

The Supreme Court's 2022 decision in West Virginia v. EPA suggested the Court might be willing to deploy the major questions doctrine aggressively. But that case involved a specific provision of the Clean Air Act about how power plants could be regulated. Here, we're talking about the EPA's fundamental power to identify endangering pollutants.

There's also a deeper statutory principle at play. Congress wrote the Clean Air Act to be adaptive. It gives the EPA the power to regulate "pollutants" generally. It doesn't give Congress the power to name every pollutant individually. That would make the statute obsolete. As science discovers new harms, the statute is supposed to evolve with it.

Greenhouse gases were never included in the original statute because their effects weren't understood in 1970. But by 2009, the science was clear. The EPA made the endangerment finding. The statute was applied as written. Now the Trump administration is arguing that applied the statute too broadly.

Here's what makes this legally precarious for the Trump administration: they're arguing for an interpretation of the Clean Air Act that would have seemed obviously wrong to Congress in 1970 and still seems wrong to most federal courts. If Congress wanted to exclude greenhouse gases, they could amend the statute. They haven't. Instead, they've repeatedly acknowledged climate change and its severity in other contexts.

How the EPA Actually Makes an Endangerment Finding

To understand why the Trump administration's legal argument is weak, it helps to know how the endangerment finding process actually works. It's not some exotic agency power. It's a straightforward fact-finding procedure.

The Clean Air Act requires the EPA to determine whether a pollutant endangers public health or welfare. That's a scientific and factual question. Does this substance harm people or the environment? If yes, regulate it. If no, don't.

The EPA doesn't get to make up its own test for "endangerment." The statute defines it: effects must be "reasonably anticipated." They can't be purely speculative. They can't be theoretical. They have to be based on evidence.

When the EPA issued the 2009 endangerment finding, they evaluated thousands of peer-reviewed studies. They looked at paleoclimate data showing how the atmosphere responded to changes in greenhouse gas concentrations over millennia. They examined ice cores from Antarctica and Greenland. They analyzed instrumental records from weather stations and satellites. They reviewed studies on ecosystem impacts, ocean acidification, extreme weather linkages, and public health effects.

Then they asked: is it reasonable to anticipate that greenhouse gases endanger public health or welfare? The answer was unambiguously yes.

Fourteen years later, the evidence is stronger. We have longer observational records. Attribution science has advanced—we can now link specific events to climate change with statistical confidence. Models have been validated. Real-world data has confirmed predictions made in earlier assessments.

The Trump administration's legal argument suggests the EPA should just... not have this power. But that's not how statutes work. If Congress wanted to exclude greenhouse gases, they could write that exclusion. They haven't. The statute as written gives the EPA precisely the authority the Trump administration claims it lacks.

One more thing worth noting: endangerment findings are supposed to be based on the best available science. The Trump EPA didn't commission new science. They didn't discover hidden flaws in the 2009 analysis. They just declared it void.

When environmental groups challenge that revocation in court, they'll introduce the National Academies report. They'll show that the scientific basis for the finding has only strengthened. The Trump administration will have to argue that it doesn't matter. The EPA doesn't have power to regulate greenhouse gases, regardless of the evidence.

That's a tough position to defend in federal court, especially before a Court that's already ruled once (in Massachusetts v. EPA) that greenhouse gases are pollutants under the Clean Air Act.

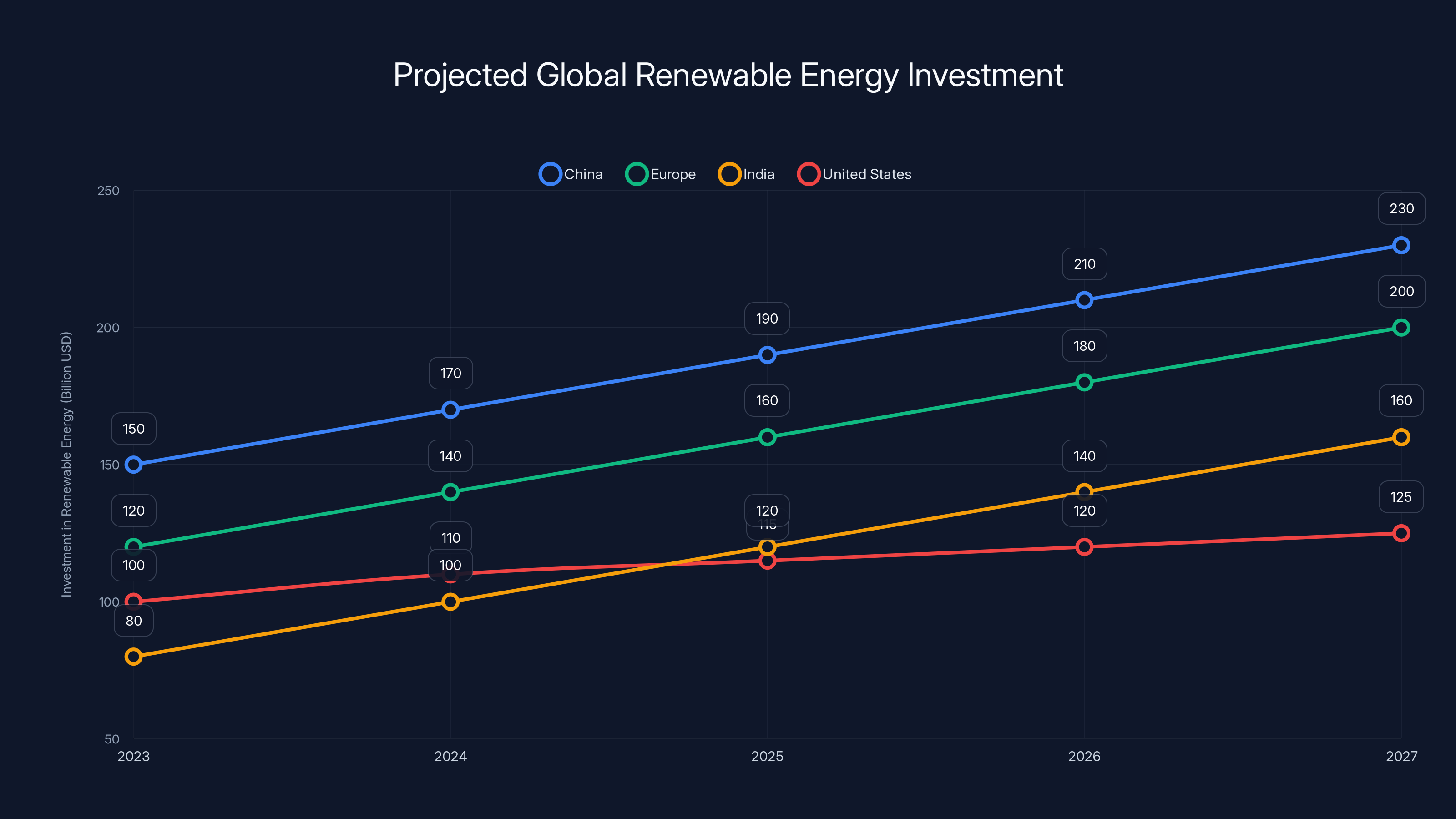

Estimated data shows that China, Europe, and India are projected to significantly increase their investment in renewable energy, while the U.S. lags behind due to policy choices. Estimated data.

What Happens to Existing Regulations?

Now here's a practical question: if the endangerment finding is revoked, what about all the regulations already on the books? Do they disappear immediately?

The answer is complicated, and it reveals a lot about how this legal battle will play out.

Regulations that were issued under the endangerment finding have multiple potential legal foundations. Some regulations might be defensible even without the endangerment finding. Some probably aren't. It depends on how the rules were written and what statutory authority they claimed.

Consider fuel economy standards for vehicles. The EPA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration issue these jointly. The regulations are written to serve several purposes: improving fuel efficiency, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and saving consumers money at the pump. Even without the endangerment finding, fuel economy standards might be justified under the statute as promoting fuel efficiency and reducing energy consumption.

But rules that are explicitly about greenhouse gas emissions and public health? Those become vulnerable. An EPA finding that greenhouse gases endanger health provided the legal hook for those rules. Without it, challengers can argue the rules lack a sufficient legal basis.

What likely happens is this: environmental groups immediately challenge the endangerment finding revocation in federal court. They ask for a preliminary injunction to block it while the case proceeds. They argue that the revocation is arbitrary and capricious—the Trump EPA didn't give an adequate explanation for overturning the finding. They also argue it violates the Administrative Procedure Act.

Meanwhile, industry groups probably challenge specific regulations, arguing that without the endangerment finding, those rules can't stand. Different suits will wind up in different courts. Some might reach the Supreme Court faster than others.

The landscape is messy. But the basic principle is this: if the endangerment finding is restored (because courts strike down the revocation), all the existing regulations remain on the books. If the revocation stands, the regulations become legally vulnerable to challenge.

State Responses and the Federalism Question

Here's where this gets interesting. The Trump administration doesn't have complete control over climate regulation. States do too.

Under the Clean Air Act, states can adopt their own emissions standards, provided they're at least as strict as federal standards. California has done this for decades. It's developed its own vehicle emissions rules and environmental standards. Because California is influential and auto manufacturers don't want different standards for different states, when California adopts a rule, other states often follow.

At least sixteen states with Democrat governors have already said they'll challenge the endangerment finding revocation. They're also considering protecting their own state regulations and potentially adopting new ones to fill the gap created by federal withdrawal.

This creates a federalism question: can states effectively require the EPA to regulate greenhouse gases by developing their own rules and forcing the agency to coordinate with them? Not directly. But states can absolutely regulate emissions within their borders. And if enough states do it, they effectively create a de facto national standard.

Some states are going further. New York, for example, is considering proposing emissions standards for power plants and vehicles. Vermont has signaled interest in stricter methane regulations. Massachusetts is considering comprehensive climate legislation.

The fossil fuel industry hates this. It's precisely why the Trump administration is moving to revoke the endangerment finding. Revoking it is meant to provide legal cover for eliminating federal regulations. But if states fill the gap, the industry still faces regulatory burdens. They just face them fifty different ways instead of one federal way.

The Trump administration could try to preempt state regulations. They could argue that federal law preempts state climate rules. But that's a weak argument. The Clean Air Act explicitly preserves state authority. Congress wrote it that way. Courts are unlikely to read a federal preemption that Congress didn't write.

So here's the likely scenario: the federal government withdraws from climate regulation. States move in. The result is a patchwork of rules that's actually less efficient for industry than uniform federal standards. Everyone loses except lawyers. Litigation explodes.

The Trump administration might argue that greenhouse gas regulation is inherently a federal question because greenhouse gases mix globally. Carbon dioxide from California affects the atmosphere in Montana. Why should California be able to impose its rules on manufacturers? But that argument proves too much. It would suggest the EPA should be able to regulate everything, everywhere. Courts are unlikely to adopt such a sweeping principle.

What's probable is that state climate regulation becomes the de facto alternative to federal regulation for the next several years. States develop rules. They litigate with each other over whether those rules discriminate against out-of-state commerce. They coordinate regionally to prevent firms from jumping between jurisdictions. It's messy. But it happens.

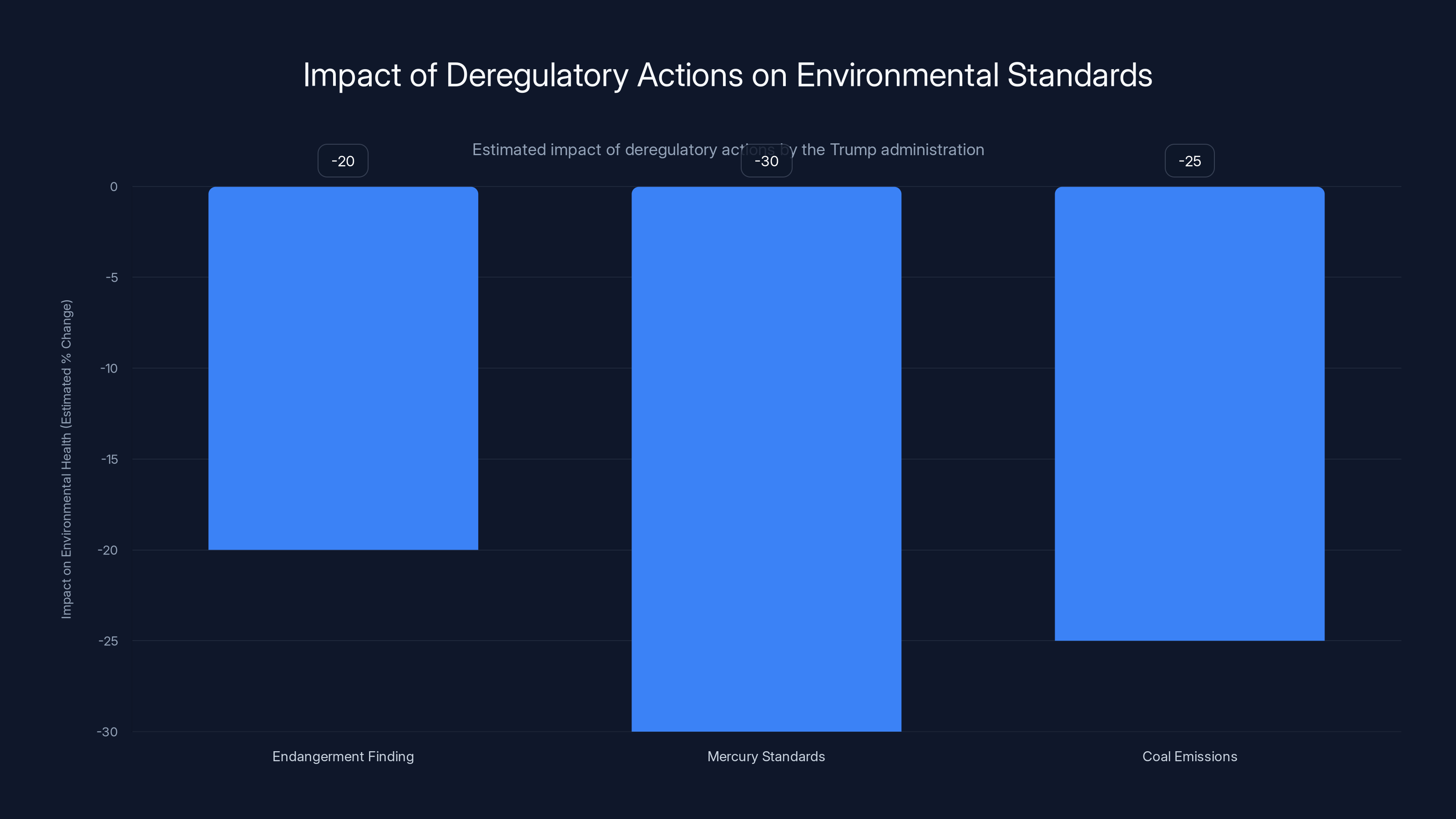

Estimated data shows significant negative impacts on environmental health due to deregulatory actions, with mercury standards repeal having the largest estimated effect.

The Supreme Court Reckoning That's Coming

This legal fight will almost certainly reach the Supreme Court. The question is whether it happens in 2026 or 2027 or later. But it will happen. Too much is at stake for this to be resolved at lower court levels.

When it does, the Court will have to revisit Massachusetts v. EPA. In that 2007 case, the Supreme Court ruled that greenhouse gases are "air pollutants" under the Clean Air Act and that the EPA has power to regulate them. The Court was 5-4 then. And all five justices in the majority—John Paul Stevens, Anthony Kennedy, David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer—are now retired or dead.

The current Court is more conservative. It has three Trump appointees. It's shown skepticism of broad EPA authority in recent cases. So the question is obvious: will the current Court reverse Massachusetts v. EPA?

There are reasons to think the answer is no, despite the Court's conservative tilt. First, reversing a major precedent is a big deal. Courts don't do it lightly. It undermines confidence in judicial stability. Second, the statutory language is clear. The Clean Air Act gives the EPA power to regulate pollutants that endanger public health. Greenhouse gases demonstrably do that. The statute is explicit.

Third, overturning Massachusetts v. EPA would require the Court to essentially read greenhouse gases out of the Clean Air Act. But the statute doesn't mention greenhouse gases at all. It just says "pollutants." The Court would have to write an exception into a statute that Congress didn't write.

That said, the Court could side with the Trump administration on narrower grounds. They could uphold the endangerment finding but limit the EPA's regulatory authority. They could say the EPA can identify greenhouse gases as endangering public health but can't write broad rules about how to regulate them. They could invoke the major questions doctrine.

Whatever happens, the decision will be momentous. It will determine whether the federal government can regulate greenhouse gases at all. It will shape climate policy for decades. It might even influence how courts interpret the Clean Air Act's authority over other emerging pollutants.

There's another procedural question: how does the case get to the Supreme Court? Does an environmental group sue the EPA directly, arguing the revocation is unlawful? Do states file suit? Do industry groups join as intervenors? The configuration of the litigation matters because it affects which arguments get emphasized.

Most likely, an environmental organization brings suit within days of the revocation being finalized. They challenge it in the D. C. Circuit Court of Appeals, which handles EPA cases. The Trump administration defends the revocation. The environmental group appeals an adverse decision (or vice versa) to the Supreme Court. The Court grants cert because the case involves a major question about federal power and climate policy.

Then, probably in 2026 or 2027, the Supreme Court will decide whether the EPA has the power to regulate greenhouse gases. That decision will reverberate through the entire regulatory state.

The Broader Deregulatory Agenda

The endangerment finding revocation isn't an isolated move. It's part of a broader deregulatory strategy. The Trump administration issued an executive order on the first day of the new term directing Zeldin to eliminate the finding. He's not acting independently. This is policy from the top.

Consider the context. The same week the EPA was finalizing the endangerment finding revocation, the administration announced plans to repeal Mercury and Air Toxics Standards. Those standards reduce mercury, arsenic, and other poisonous metals in coal plant emissions. They've prevented thousands of premature deaths from air pollution. But they also cost the coal industry money, and the Trump administration is hostile to environmental regulations.

The White House even organized a coal celebration event—literally, a pro-coal rally—to coincide with the endangerment finding revocation announcement. Lee Zeldin appeared alongside President Trump to declare that eliminating climate regulations would "unleash American energy dominance" and "drive down costs."

This rhetoric is important because it reveals what's actually happening. The Trump administration isn't being driven by a legal theory that the EPA lacks authority. They're driven by an ideological commitment to fossil fuels and opposition to environmental regulation. The legal argument is convenient cover for that ideology.

Historically, that matters in litigation. When agencies reverse course for what courts perceive as arbitrary or ideologically driven reasons, judges scrutinize the decision more carefully. Environmental groups will argue that the Trump EPA can't overturn a finding without confronting the underlying science. They'll point to the National Academies report. They'll argue that ideology doesn't trump statutory text.

The Trump administration will counter that precedent and legal theory trump ideology. They'll argue that even if the endangerment finding is scientifically sound, it exceeds EPA authority. The legal question is separate from the scientific question.

Both sides have plausible arguments. But judges—especially federal judges—might be skeptical of an agency that says "the science is right, but we're overturning it anyway for legal reasons." That combination rings false. If the science is right, the legal authority usually follows. If the science is wrong, then say so. Trying to have it both ways undermines credibility.

The scientific evidence supporting the endangerment finding has strengthened significantly from 2009 to 2025, with advancements in attribution science and longer observational records. (Estimated data)

What Happens to International Climate Commitments?

The endangerment finding revocation has implications beyond U. S. law. It affects international climate negotiations and U. S. credibility on climate issues.

The United States is a signatory to the Paris Agreement, an international treaty committing nations to limit global warming. Revoking the endangerment finding signals that the U. S. is backing away from that commitment. Other nations notice. They'll likely take it as evidence that U. S. climate policy will fluctuate wildly depending on who holds power.

That's a problem. International climate negotiations depend on stable commitments. If the U. S. government alternates between administrations that are pro-climate and anti-climate, foreign governments and corporations can't make reliable plans. Investments in clean energy become risky. International partnerships become tentative.

China and India have both criticized the U. S. for inconsistent climate policy. They point to the Obama administration's climate initiatives and the Trump administration's rollback, then the Biden administration's Inflation Reduction Act investments, and now another Trump administration rollback. How are they supposed to plan long-term climate cooperation with a partner that swings back and forth?

There's also the question of U. S. leadership on climate. For decades, the U. S. claimed to be the global leader on environmental issues and clean energy innovation. Revoking the endangerment finding undermines that claim. It signals that the U. S. is choosing coal and fossil fuels over clean technology.

Innovatively, that might be backwards. Clean energy is increasingly the economic opportunity. Solar and wind are now cheaper than coal in most U. S. markets. Electric vehicles are becoming cost-competitive with gasoline vehicles. Battery technology is advancing rapidly. By focusing on fossil fuels, the Trump administration might be choosing yesterday's economy instead of tomorrow's.

Some countries are already using the endangerment finding revocation as evidence that they shouldn't rely on the U. S. for climate cooperation. They're moving toward bilateral and regional arrangements without American participation. That isolates the U. S. from the clean energy transition that's already happening globally.

There's also a reputational cost. Scientists worldwide view the endangerment finding as a straightforward application of climate science to policy. Revoking it makes the U. S. government look ideologically driven and indifferent to scientific evidence. American scientists, businesses, and policymakers have to explain or defend a decision they didn't make and many don't support.

The Economic Argument: Will Deregulation Actually Cost Less?

The Trump administration is selling this as a cost-saving measure. They claim that eliminating the endangerment finding will "drive down costs" by reducing regulatory burdens on fossil fuel companies.

But that argument gets complicated when you factor in the real costs of pollution and climate change.

Air pollution from burning coal kills thousands of Americans annually. Cancer from air toxics, heart disease from particulate matter, respiratory illness from ozone—these carry medical costs, lost productivity, and human suffering. When you eliminate regulations that prevent those harms, you're not really saving money. You're just shifting costs from companies to communities.

Climate change itself carries enormous costs. Extreme weather damages infrastructure, disrupts agriculture, increases insurance premiums, and forces costly adaptations. The longer the U. S. delays emissions reductions, the more expensive those eventual reductions become. There's a powerful economic argument for early action on climate.

Think of it this way: a carbon tax in 2025 is cheaper than the cost of rebuilding infrastructure destroyed by climate-driven disasters in 2035. A methane regulation on oil and gas companies in 2025 is cheaper than the public health costs of continued exposure to methane-related air pollution in 2035.

The Trump administration's deregulatory agenda focuses on short-term savings for fossil fuel companies. They ignore long-term economic costs for everyone else. That's a legitimate policy choice—prioritizing industry over public health. But it shouldn't be dressed up as cost-saving. It's cost-shifting.

States will likely end up bearing more of the burden. If federal emissions standards are eliminated, states have to regulate more aggressively to protect their own air quality and public health. They'll develop their own rules, conduct their own monitoring, and fund their own enforcement. That's more expensive than coordinated federal action.

Businesses operating across multiple states will face a fragmented regulatory landscape. That increases compliance costs. They'll need different pollution control systems for different states. They'll need different reporting procedures. They'll need different legal expertise in multiple jurisdictions. Nationwide uniformity through federal regulations is actually more efficient and cheaper than a patchwork of state rules.

The irony is that by trying to eliminate federal environmental regulations, the Trump administration might end up creating a more expensive regulatory environment overall. States will fill the gap. Litigation will proliferate. Compliance becomes more complex.

What Environmental Groups Are Actually Going to Do

Environmental advocacy groups have been remarkably coordinated in their response to the endangerment finding revocation. They didn't wait for the Trump administration to finish. They started preparing litigation immediately.

The strategy is likely to unfold in phases. First, file lawsuits challenging the revocation as legally defective. The Trump EPA will have to explain why they're overturning a finding based on overwhelming scientific evidence. Environmental lawyers will argue that the decision is arbitrary and capricious—the agency didn't grapple with the evidence, didn't acknowledge contrary science, and didn't provide a reasoned explanation.

Second, seek preliminary relief. Environmental groups will ask courts to block the revocation while litigation proceeds. They'll argue that the revocation causes irreparable injury by eliminating EPA authority to protect public health. They'll ask judges to maintain the status quo.

Third, litigate in multiple forums simultaneously. Cases will hit federal district courts, the D. C. Circuit Court of Appeals, and probably the Supreme Court. Coordinating between these cases is difficult, but environmental organizations have experience doing it. They'll try to get a favorable ruling from one court early, establish precedent, and use that to influence other cases.

Fourth, link arms with state governments. States have their own legal authority and their own interest in fighting the revocation. When states sue the federal government, they're taken seriously by courts. Environmental groups will support state litigation and coordinate strategies.

Fifth, focus on judicial review standards. The Administrative Procedure Act requires agencies to explain major decisions. The Trump EPA will have to provide a reasoned explanation for why they're overturning the endangerment finding. Environmental lawyers will argue that no adequate explanation exists. You can't just say "the EPA lacked authority" without grappling with the statutory language and prior precedent.

Sixth, delay. Environmental groups will use litigation to slow the deregulatory process. Every month the endangerment finding revocation is blocked is a month the existing regulations remain in effect, continue reducing emissions, and prevent harms.

The goal isn't necessarily to win every case. It's to sustain uncertainty, bog down the federal government in litigation, and prevent the fossil fuel industry from fully escaping environmental regulation. That keeps pressure on the administration and gives the next administration (if it's pro-climate) a pathway to reverse course.

Former EPA officials are also mobilizing. Joseph Goffman, who led the EPA's air quality office under Biden, has been vocal in his criticism. The Environmental Protection Network—an organization of former EPA employees—released a statement saying the revocation is a "surrender" of the EPA's responsibility. These former officials have credibility. When they testify in court about how the EPA normally operates and how this decision breaks from that pattern, judges listen.

Individual scientists are also mobilizing. A group of atmospheric scientists and climate researchers is likely preparing a statement for the court about what the scientific evidence actually shows. The Trump administration can claim the EPA lacks power, but they can't prevent scientists from telling courts what the science says.

A Precedent for Deregulation Across Industries

Why does this matter beyond climate change? Because the legal argument the Trump administration is using could apply to many other regulations.

If the Supreme Court agrees that the EPA exceeded its authority by regulating greenhouse gases, what about other statutes that delegate broad powers to agencies? The Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulates workplace hazards. Do they have authority to regulate emerging dangers like long COVID or heat stress? The Food and Drug Administration regulates drugs and food. Can they regulate novel technologies?

The Trump administration seems to be laying groundwork for attacking agency authority across the board. Revoking the endangerment finding is the flagship issue. But it's not an isolated move. The broader theme is that agencies have accumulated too much power and need to be constrained.

If courts agree and deploy the major questions doctrine aggressively, it could affect labor law, food safety, drug approval, environmental protection, workplace conditions, and consumer protection. Every regulation would become vulnerable to challenge as an overreach of agency authority.

That's why this fight matters to more than climate advocates. It's about the fundamental structure of federal regulation. Has Congress delegated too much to agencies, or has Congress written statutes authorizing agencies to address emerging problems? That question will determine how the government can respond to new challenges for decades.

Public health advocates, labor unions, and consumer protection groups are watching this case closely. What happens with the endangerment finding will affect whether agencies can respond to other public health threats effectively.

The Next Two Years and Beyond

Here's what's probably going to happen in the near term.

First, the endangerment finding revocation will be challenged immediately, probably within days. Environmental groups will file suits in multiple courts. Some of those cases will reach the D. C. Circuit, which has jurisdiction over EPA actions.

Second, the Trump administration will defend the revocation vigorously. They'll file briefs arguing the EPA lacked authority. They'll claim that the major questions doctrine constrains EPA power. They'll try to distinguish Massachusetts v. EPA.

Third, individual lawsuits will challenge specific regulations that depend on the endangerment finding. The Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emission Standards will be challenged. Power plant regulations will be challenged. Methane rules will be challenged. There will be litigation chaos.

Fourth, states will play a larger role. Democrat-led states will join environmental groups in litigation. They'll also develop state-level regulations to fill the gap created by federal withdrawal.

Fifth, Congress probably won't act. The Republican majority in Congress has shown no interest in climate legislation. If they did, it would likely be to protect fossil fuel companies, not to advance climate goals. So Congress is not the forum for a legislative reversal of this policy.

Sixth, the Supreme Court will eventually grant cert on the endangerment finding question. When they do, they'll have to decide whether the EPA has power to regulate greenhouse gases. The outcome will reshape climate policy and agency authority.

Beyond the next two years, a lot depends on election outcomes. If a pro-climate administration wins in 2028, they could reinstate the endangerment finding. If a Republican administration remains, they'll continue the deregulatory push.

The climate question isn't really resolved by this particular Trump administration decision. It's kicking the issue to courts and future administrations. And that's the core problem: the U. S. doesn't have a stable climate policy. It has policies that swing back and forth depending on electoral outcomes. That makes long-term planning difficult and undermines American credibility internationally.

The Broader Climate Imperative That Doesn't Change

Here's what needs to be said clearly: the Trump administration's legal maneuver doesn't change the underlying climate reality.

Greenhouse gases are warming the atmosphere. The physics hasn't changed. The mechanism is straightforward: greenhouse gases trap heat. That's not controversial. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is increasing. The rate of increase is accelerating. The warming effect is observable and measurable.

Moreover, that warming has consequences. It's making extreme weather worse. It's changing precipitation patterns. It's stressing ecosystems. It's creating public health hazards. The impacts are happening now, not just predicted for the future.

The Trump administration can eliminate the endangerment finding. They can revoke regulations. They can even appoint judges who might uphold those reversals. But they can't change the science.

What happens if the U. S. largely exits climate regulation? Other countries will probably move faster. China is investing heavily in renewable energy and electric vehicles. Europe has aggressive climate targets. India is rapidly expanding solar capacity. Those countries will capture the economic benefits of clean energy transition.

The U. S. will gradually fall behind in technologies that matter for the 21st century. Solar, wind, batteries, electric vehicles—these are the technologies of the future. By choosing to protect coal and natural gas, the Trump administration is choosing decline. The market is already moving away from fossil fuels. Federal policy that tries to prop them up is fighting economic reality.

So from a purely pragmatic standpoint, this policy is likely to fail. It might slow climate regulation for a few years. But global climate change and global economics are stronger forces than any single government. If the U. S. government refuses to regulate greenhouse gases, the market, other countries, and states will do it anyway.

The real question is whether the U. S. wants to be a leader in the clean energy economy or a laggard. The Trump administration is choosing to be a laggard. That's a choice about national economic strategy, not really about climate science or environmental values.

FAQ

What exactly is an endangerment finding?

An endangerment finding is a formal EPA determination that a specific substance or class of substances poses a danger to public health or welfare. The Clean Air Act requires the EPA to regulate any pollutant it determines is endangering public health. In 2009, the EPA issued a finding that greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare, providing the legal authority for climate regulations for the next sixteen years.

Why is the Trump administration revoking it?

The Trump administration argues that the EPA exceeded its constitutional and statutory authority by issuing the endangerment finding in the first place. They're not claiming that greenhouse gases don't harm public health—they're claiming the EPA has no power to regulate based on that harm. This is a legal argument, not a scientific one. The administration issued an executive order directing the EPA to revoke the finding, and EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin carried out that order.

Is the scientific evidence for the endangerment finding weaker now than in 2009?

No, the opposite is true. The National Academies of Sciences reviewed the scientific evidence and concluded it's stronger now. Observational records are longer. Attribution science has advanced, allowing researchers to link specific extreme weather events to climate change. Scientists can now point to current harms, not just future predictions. The scientific case for the endangerment finding is more robust in 2025 than it was in 2009.

What happens to existing EPA climate regulations if the finding is revoked?

That's legally uncertain and depends on how individual regulations were written and what statutes they invoked. Some regulations might survive on alternative legal grounds. Others will become vulnerable to challenge. The practical effect is likely that regulations remain in place while litigation proceeds, but there will be uncertainty about which rules are actually enforceable. The Trump administration will probably try to eliminate specific regulations one by one, while environmental groups fight each elimination in court.

Will states fill the gap if federal regulations disappear?

Yes, almost certainly. States have independent authority to regulate air pollution and emissions within their borders. California and other states have already signaled they'll adopt their own climate and emissions standards if federal regulations disappear. Because states can be stricter than federal rules under the Clean Air Act, this could actually result in a patchwork of different standards across the country, which is less efficient than uniform federal regulation but still effective at reducing emissions.

Is this case definitely going to the Supreme Court?

Virtually certainly, yes. The case will likely take several years to wind through the courts. Environmental groups will file lawsuits challenging the revocation. The Trump administration will defend it. At least one suit will appeal an unfavorable decision to the Supreme Court, and the Court will almost certainly grant cert because the case involves fundamental questions about federal power and the Clean Air Act. The current Supreme Court has already expressed skepticism about broad EPA authority, so the outcome is uncertain, but the case will definitely reach them.

What does "major questions doctrine" mean and why does it matter?

The major questions doctrine is a legal principle holding that when a statute could be interpreted to give an agency vast new powers over issues of enormous economic or political significance, courts should require that Congress speak with exceptional clarity. The Trump administration is arguing that regulating the entire economy's greenhouse gas emissions is such a major question that it requires explicit Congressional authorization. Environmental groups counter that Congress already spoke clearly—the Clean Air Act authorizes regulation of any pollutant endangering public health. The doctrine is important because the Supreme Court has shown willingness to deploy it aggressively in recent years.

Could the U. S. meet climate commitments without federal EPA regulations?

It would be very difficult. International climate commitments like the Paris Agreement assume significant emissions reductions from all countries, including the U. S. Without federal regulations forcing power plants, vehicles, and industries to reduce emissions, achieving those reductions depends entirely on state action and voluntary corporate commitments. Some companies might voluntarily reduce emissions, but others won't. States can help, but they can't force nationwide reductions as effectively as federal standards. So eliminating federal climate regulations makes it much harder for the U. S. to meet international climate commitments.

What happens if the Supreme Court upholds the endangerment finding revocation?

If the Supreme Court agrees that the EPA lacked authority to issue the endangerment finding, it would be a seismic shift in environmental law. Federal climate regulation would essentially stop. The EPA couldn't regulate greenhouse gases unless Congress passed new legislation explicitly authorizing it. States would fill some of the gap with their own regulations, but national emissions would likely increase. The decision could also create precedent limiting EPA authority over other pollutants and environmental issues. It would reshape decades of environmental protection.

Conclusion: Where This Battle Heads

The Trump administration's revocation of the endangerment finding is a bold and controversial legal maneuver. On its face, it seems like an attempt to deny climate science and abandon environmental protection. But what's actually happening is more subtle and more legally precarious.

The administration isn't arguing that climate science is wrong. They're arguing that the EPA exceeded its authority by regulating based on that science. That's a different claim, and it's one that rests on some legitimate legal theories but also some deeply questionable ones.

The Clean Air Act is written broadly. It gives the EPA power to regulate any pollutant that endangers public health. Greenhouse gases demonstrably endanger public health. The statute doesn't carve out an exception for greenhouse gases. It applies to any pollutant. That's the text. That's what Congress wrote.

For the Trump administration to win, the Supreme Court would essentially have to rewrite the Clean Air Act. They'd have to read in an exception that Congress didn't write. They'd have to limit the EPA's authority in a way that contradicts the statute's plain language. That's possible—the current Supreme Court is willing to constrain agency authority. But it's not inevitable.

Moreover, the legal argument the Trump administration is advancing could have broader implications. If the EPA doesn't have power to regulate greenhouse gases, what about other environmental threats? What about emerging pollutants? What about novel public health hazards? The major questions doctrine could ultimately constrain agency power across the government.

That's why this fight matters far beyond climate change. It's about whether agencies can respond to new and evolving threats or whether their authority is locked in place by 50-year-old statutes written before anyone imagined those threats.

What's almost certain is that this will be litigated for years. The endangerment finding revocation will be challenged immediately. Various regulations will be defended separately. States will sue. The Supreme Court will eventually weigh in. And whatever they decide will reshape climate policy and environmental protection for decades.

In the meantime, the climate continues changing. Greenhouse gases keep accumulating. Temperatures keep rising. Extreme weather keeps intensifying. The Trump administration's legal maneuver doesn't change any of that. It just changes which branch of government gets to address it.

For those paying close attention, the real question isn't whether the endangerment finding is scientifically sound—it is. The real question is whether the EPA has the legal authority to act on that science. And that question will ultimately be decided by judges, not by scientists.

Key Takeaways

- The Trump EPA revoked the 17-year-old endangerment finding that provided legal authority for federal climate regulations—a legal argument, not a claim that science is wrong

- The National Academies of Sciences confirmed the endangerment finding is supported by stronger scientific evidence now than when it was originally issued in 2009

- Environmental groups and Democrat-led states are already litigating the revocation, and the case will almost certainly reach the Supreme Court, which must revisit its 2007 Massachusetts v. EPA precedent

- If the revocation stands, states will likely fill the regulatory gap with independent climate rules, creating a patchwork that's actually more complex and costly for industry than federal standards

- The legal outcome hinges on whether courts believe the Clean Air Act's plain language gives the EPA authority to regulate pollutants endangering public health or whether that power is constrained by the major questions doctrine

Related Articles

- DOE Climate Working Group Ruled Illegal: What the Judge's Decision Means [2025]

- NLRB Drops SpaceX Case: What It Means for Worker Rights [2025]

- Judicial Body Removes Climate Research Paper After Republican Pressure [2025]

- Climate Science Removed From Judicial Advisory: What Happened [2025]

- US Offshore Wind Court Orders: Construction Restart [2025]

- Hair Sample Study Proves Leaded Gas Ban Worked [2025]

![EPA Revokes Climate Endangerment Finding: What Happens Next [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/epa-revokes-climate-endangerment-finding-what-happens-next-2/image-1-1770824366485.jpg)