Epstein Files: The Tim Cook Meeting That Exposed Silicon Valley's Hidden Networks

When the Justice Department released thousands of emails from Jeffrey Epstein's correspondence in early 2025, most headlines focused on political figures and Wall Street names. But buried in those documents was something that caught the tech world off guard: evidence that Epstein had brokered connections between some of the biggest names in computing.

Specifically, emails showed that Epstein had been instrumental in arranging a meeting between Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, and Steven Sinofsky, the former President of Windows at Microsoft. This wasn't a casual introduction. It was part of a deliberate network-building effort at a critical moment in Sinofsky's career, right after he negotiated what would become a contentious $14 million severance package from Microsoft in November 2012.

The revelation opened a window into how elite tech executives actually operate behind closed doors. It's a story about power, influence, and the surprising ways that deals get made when traditional business channels don't cut it. It's also a story that raises uncomfortable questions about the networks that connect Silicon Valley's most powerful figures, and how those networks can be leveraged in ways most people never see.

What makes this particularly interesting isn't just the names involved. It's what the emails reveal about how networking actually works at the highest levels of technology. When a CEO wants to meet another CEO, they don't always go through public channels. Sometimes they use intermediaries. Sometimes those intermediaries are people like Epstein, who had cultivated relationships across finance, real estate, and yes, technology.

The Sinofsky-Cook meeting wouldn't have been unusual on its own. Tech executives meet all the time. What makes it remarkable is the specific context: it happened right when Sinofsky was in transition, exploring options, and trying to figure out his next move. And it happened through Epstein, which tells you something about who Epstein knew, and more importantly, who was willing to work with him at a moment when his legal troubles were already becoming public knowledge.

This article digs into what the emails actually say, what they tell us about executive networks, and what they reveal about a period in tech history when the industry was consolidating power in fewer hands. We'll look at the key players involved, the timeline of events, the actual content of the emails, and what it all means for how we understand Silicon Valley's power structure.

TL; DR

- Newly released Epstein files show that Jeffrey Epstein coordinated a meeting between Tim Cook and Steven Sinofsky in late 2012

- Steven Sinofsky left Microsoft with a $14 million severance package and was exploring career options at other major tech companies

- Tim Cook apparently expressed genuine interest in meeting Sinofsky, according to Epstein's email communication

- Ian Osborne, a British "fixer to billionaires," was also involved in brokering connections between tech executives and other high-profile figures

- The emails reveal how informal networks and intermediaries operate among the world's most powerful tech executives

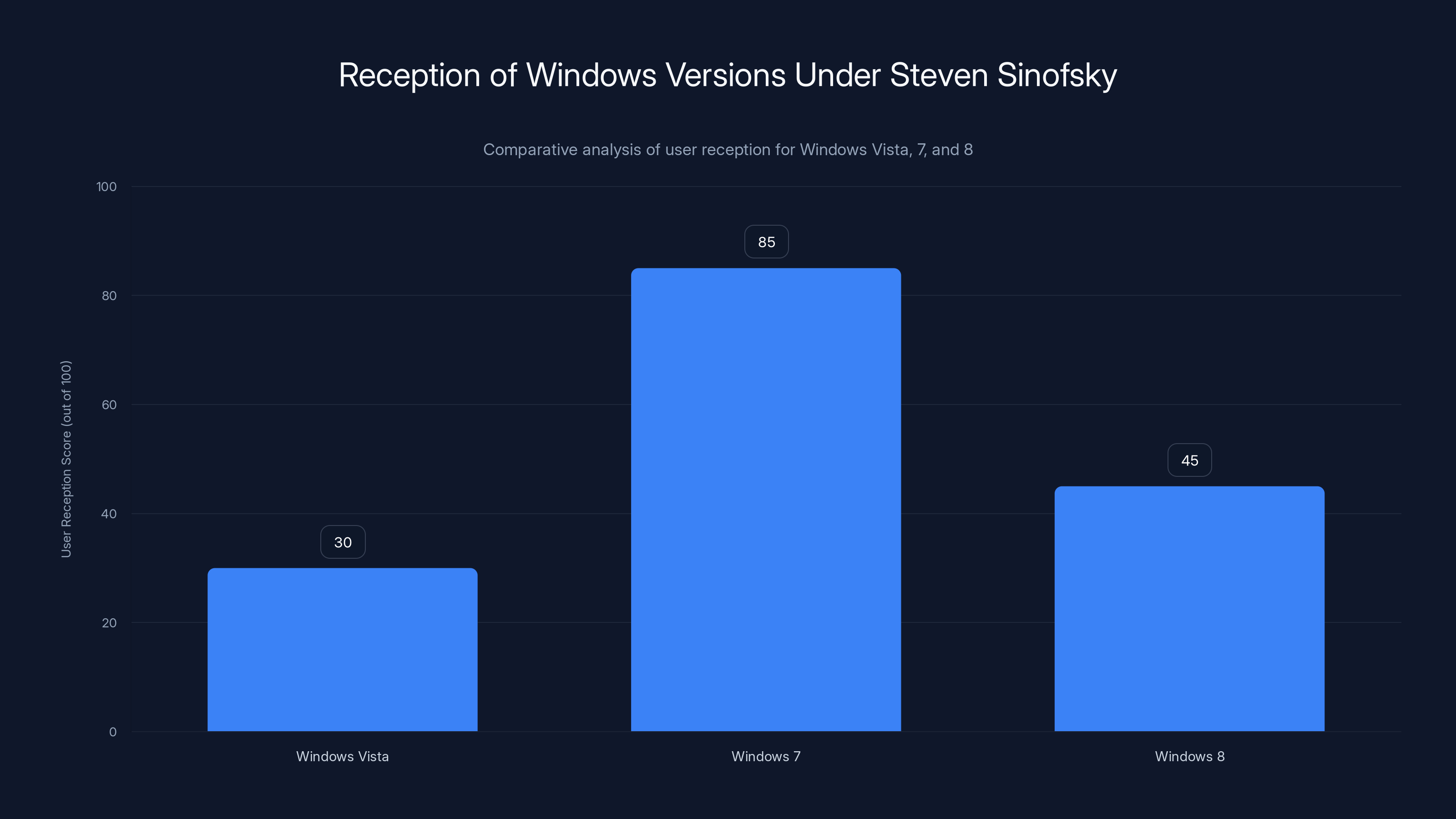

Windows 7 was highly successful with a user reception score of 85, compared to Windows Vista's 30 and Windows 8's 45. Estimated data based on historical reviews.

Who Was Steven Sinofsky, and Why Did His Microsoft Exit Matter?

Steven Sinofsky wasn't just any Microsoft executive. For seven years, he ran the Windows division, one of the most important business units in the entire technology industry. Windows isn't just software. At that time, it was the operating system that powered roughly 90% of the world's personal computers. That means Sinofsky was effectively managing the software that billions of people used every single day.

His tenure was marked by significant challenges. Windows Vista, released in 2007, was widely regarded as a commercial and critical failure. It was slow, it had compatibility issues, and users hated it. But Sinofsky recovered from that disaster by overseeing Windows 7, which was a massive success. Windows 7 became one of the most beloved operating systems in history. It solved Vista's problems, it was faster, and it felt like Microsoft had finally gotten it right.

Then came Windows 8, the tablet-first operating system that Sinofsky championed. Windows 8 was controversial. It introduced the Metro interface, removed the Start menu, and fundamentally changed how users interacted with Windows. The strategy made sense at the time: tablets were becoming increasingly important, and Sinofsky wanted Windows to compete in that space. But the public rejected it almost immediately. Corporations and individual users alike complained that Windows 8 felt unintuitive, that it abandoned the familiar Windows paradigm, and that it was trying too hard to be something it wasn't.

By 2012, Sinofsky's position at Microsoft was becoming untenable. Windows 8 had launched to poor reviews. Steve Ballmer, Microsoft's CEO at the time, was feeling pressure from investors. Something had to change. In August 2012, Sinofsky announced his departure from Microsoft. The company gave him a massive severance package, reported at $14 million. That kind of payout signals a few things: first, that Microsoft wanted to part ways cleanly without legal complications; second, that Sinofsky had enough leverage to negotiate a generous exit; and third, that his departure was significant enough that the company felt obligated to compensate him handsomely.

At 46 years old, Sinofsky suddenly found himself in a unique position. He had decades of experience running one of the world's most important software divisions. He had a massive financial cushion. And he was free to explore whatever came next. That's exactly where the Epstein emails come in.

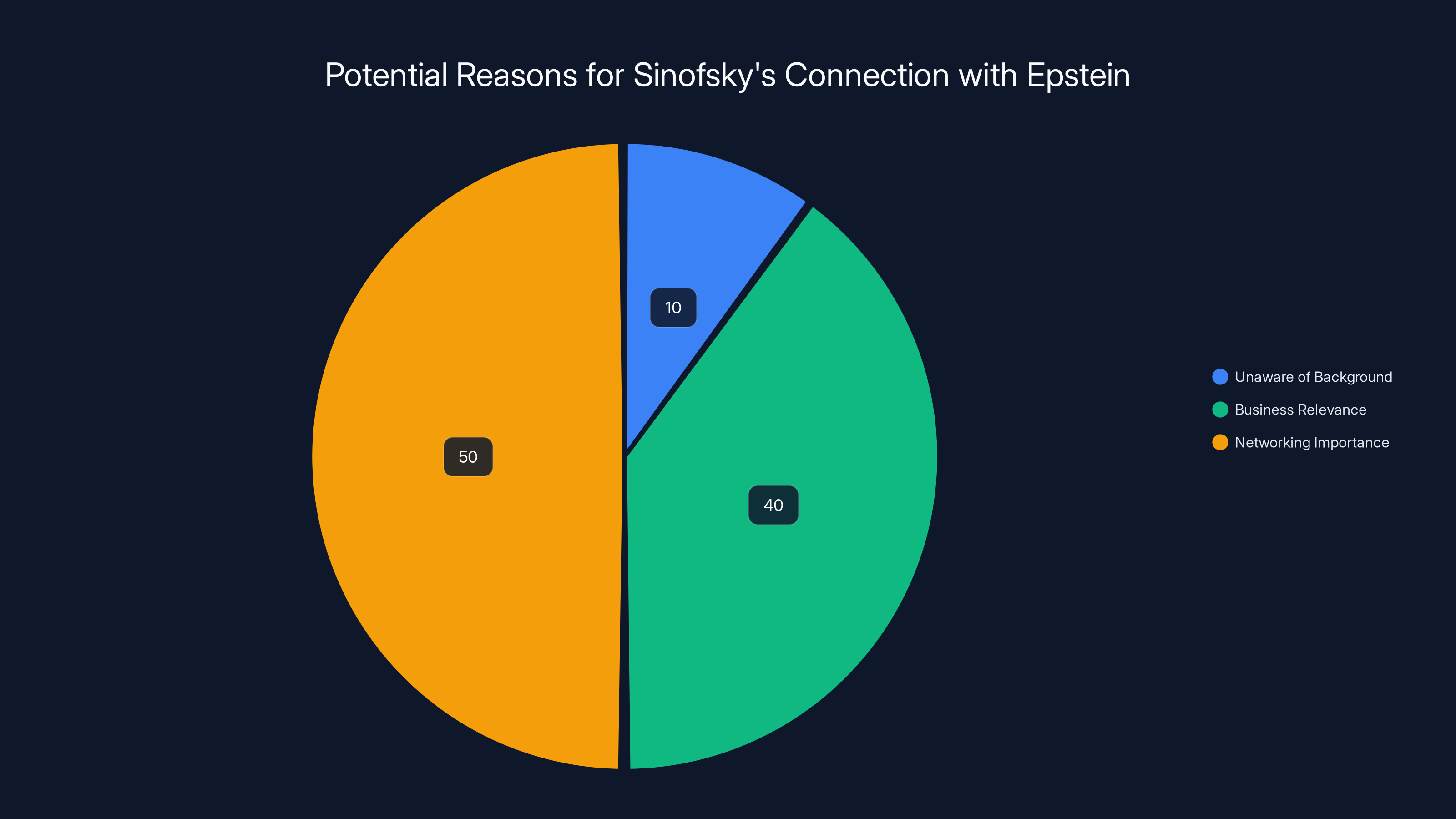

Estimated data suggests that networking importance was the primary reason for Sinofsky's connection with Epstein, followed by business relevance. Unawareness of Epstein's background is considered unlikely.

The Epstein Connection: How Did Sinofsky Know Him?

This is where things get murky. The emails don't explicitly explain how Sinofsky and Epstein initially connected, but they make it clear that by late 2012, they were in regular contact. Sinofsky was consulting with Epstein about his exit package, his non-compete agreements, and his future career options. That's an unusual relationship for a tech executive and a hedge fund manager.

Epstein had been convicted of soliciting prostitution in 2008, and he had served his sentence. By 2012, he was registered as a sex offender. Yet he was still actively involved in business circles, still brokering deals, and still connected to powerful people. The fact that Sinofsky was working with him suggests a few possibilities. Either Sinofsky didn't know about Epstein's background (unlikely for someone this sophisticated), or he knew and didn't think it was relevant to the business at hand, or the business connection was important enough that other concerns were secondary.

What's clear from the emails is that Epstein had positioned himself as a useful intermediary. He knew people. He could open doors. When Sinofsky was thinking about what to do next, Epstein apparently offered to help. "I have some thoughts on where you might have opportunities," Epstein essentially said. And then he delivered. Within weeks of Sinofsky's departure being announced, Epstein was writing to him about meetings with major tech CEOs.

This speaks to a broader pattern about how networks function at the very top of corporate America. When you're at Sinofsky's level, you don't rely on job postings or recruiters. You rely on introductions from people who know other important people. Epstein positioned himself as exactly that kind of person. Whether Sinofsky realized the implications of working with someone of Epstein's background is unclear. What is clear is that it worked. Epstein made the introduction, and Cook apparently was interested.

The Cook Email: What Exactly Did It Say?

According to the Justice Department files, approximately two weeks after Sinofsky's departure from Microsoft was announced in August 2012, Epstein sent Sinofsky an email. The email indicated that Tim Cook was "excited to meet" Sinofsky. This is significant language. "Excited" suggests genuine interest, not a obligatory coffee meeting. And Cook is not someone who takes meetings with just anyone. As the Chief Operating Officer of Apple at that time (and soon to be CEO), his schedule was incredibly full. The fact that he was apparently interested in meeting Sinofsky is notable.

However, there was a complication. Epstein mentioned in the email that Cook had heard Sinofsky was planning to start a company with "farstall." Epstein wasn't entirely sure of the spelling, which is typical of his emails—they're filled with typos and occasional confusion about names and details. But he was clearly referring to Scott Forstall, Apple's former i OS VP. Forstall had left Apple under controversial circumstances just one month before Sinofsky left Microsoft.

Why would Forstall's involvement be a problem? Because at that exact moment, Forstall and Cook didn't have a good relationship. Forstall had been forced out of Apple, and there was significant tension around his departure. If Cook thought Sinofsky was teaming up with Forstall, that could have been a dealbreaker. It's possible that Cook viewed Forstall as a rival or someone who had wronged Apple during his exit. It's also possible that Cook simply wanted to understand what Sinofsky's plans were before committing to a meeting.

The fact that Epstein included this detail in his email to Sinofsky suggests he was managing perceptions and trying to make sure both sides were aligned before the meeting happened. That's the work of an experienced intermediary. Epstein wasn't just passing along contact information. He was actively shaping the narrative, pre-addressing potential concerns, and trying to ensure the meeting went smoothly.

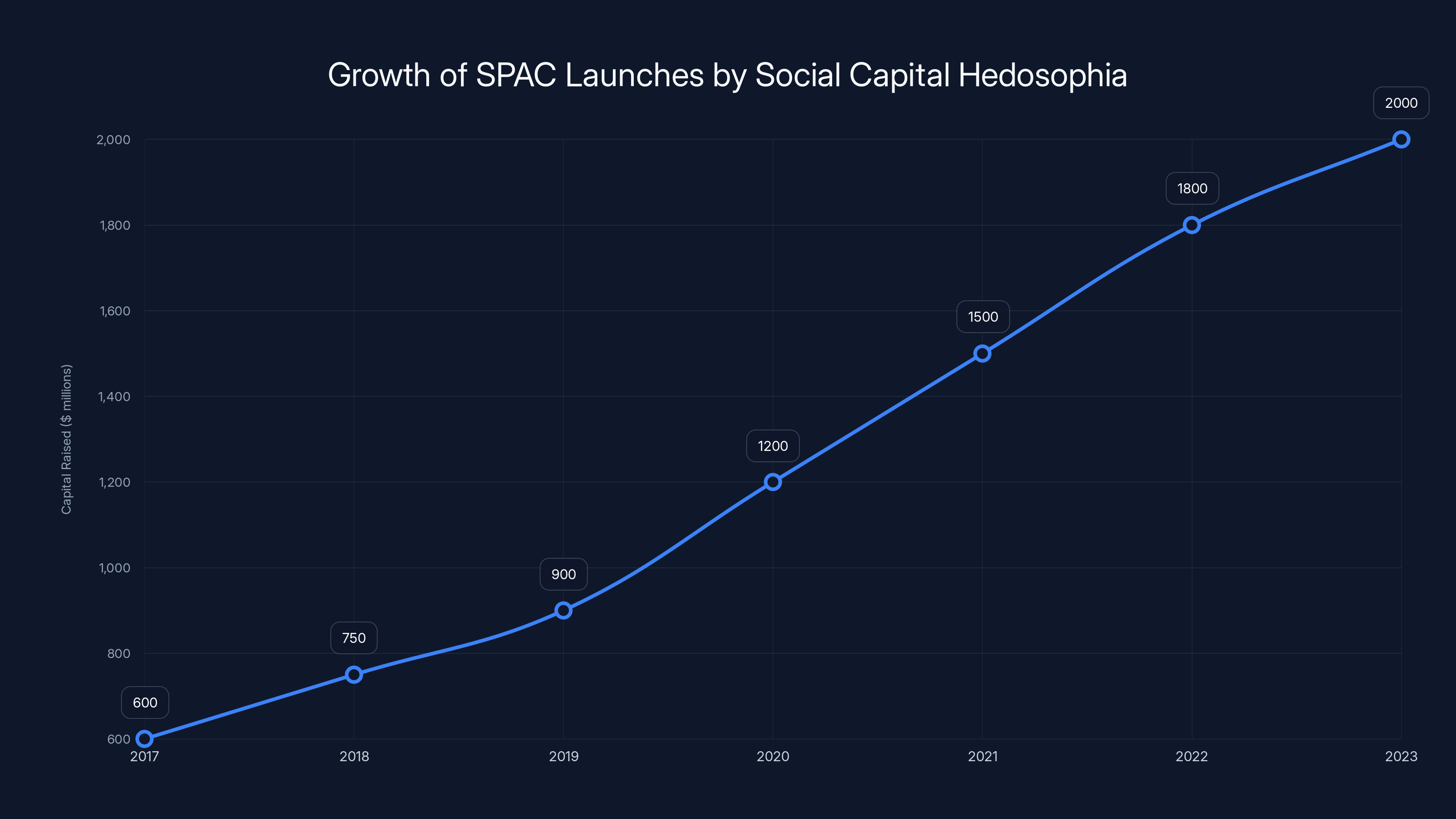

Social Capital Hedosophia's SPAC launches have shown significant growth since 2017, reflecting the increasing influence of Ian Osborne and Chamath Palihapitiya in the venture capital space. Estimated data.

The Follow-Up Email: Sinofsky and Cook Actually Met

About six months after the initial email exchange, the documents show another email from Sinofsky to Epstein. In this email, Sinofsky mentions that he did meet with Cook. More importantly, he shares what Cook said: "we should talk when I want to work full time."

This is a different kind of statement than "I'm excited to meet you." This sounds more cautious, more conditional. Cook isn't saying yes to anything. He's saying a conversation would be appropriate if and when Sinofsky decides he wants to return to full-time work. It's the kind of thing a CEO says when they're interested in someone but not ready to make a move. It keeps the door open without creating an obligation.

What's interesting is that six months had passed between Epstein's initial email and the meeting. In the world of high-level business, that's a long time. Things can change. Priorities shift. Yet apparently, the meeting happened. We don't know what was discussed, how long it lasted, or what came of it in the immediate aftermath. But the fact that Sinofsky felt it was worth reporting back to Epstein suggests he considered it meaningful.

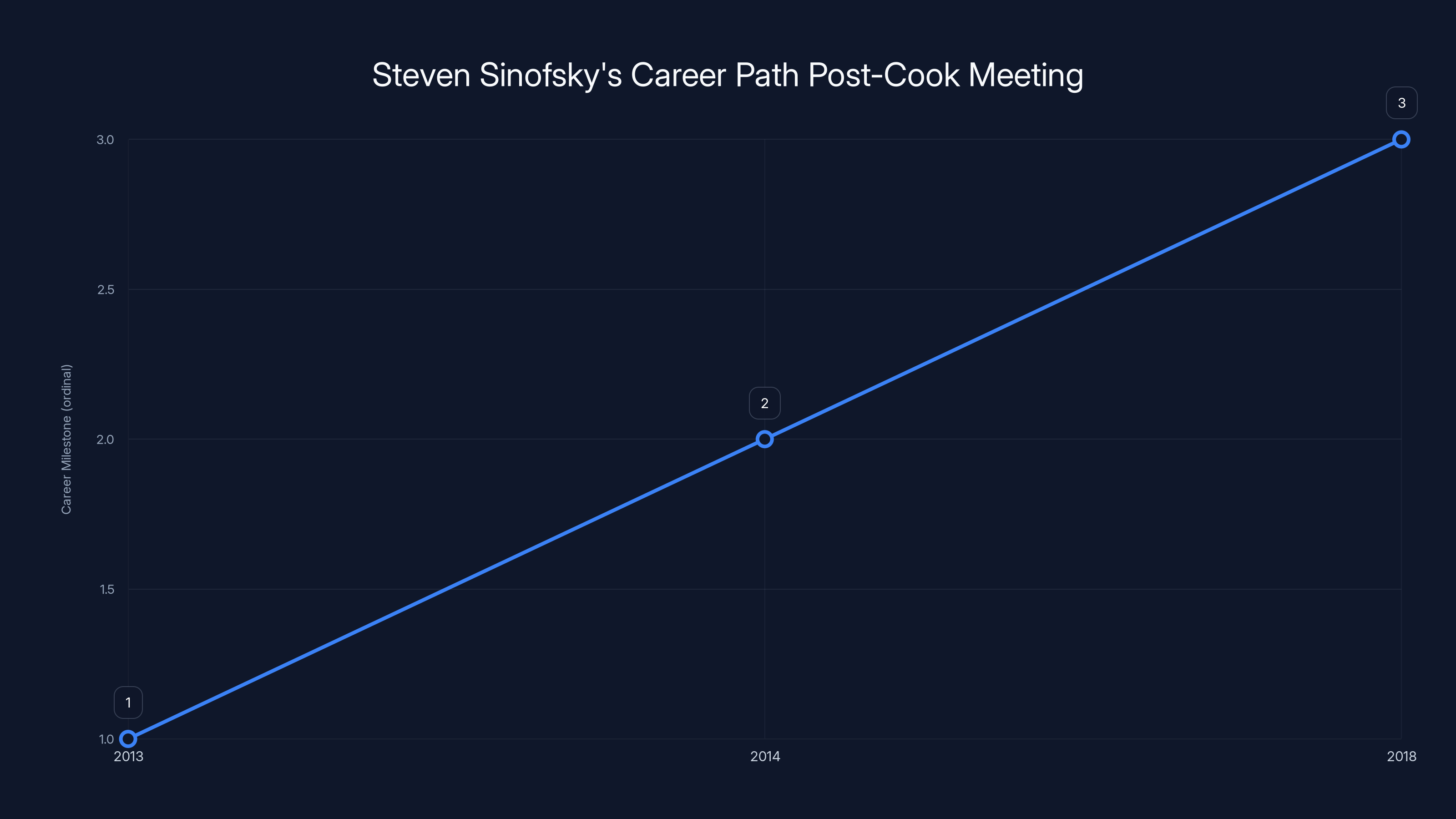

We also know that Sinofsky did not end up joining Apple. He launched Slope Ventures, a venture capital firm, in 2013. He later became CEO of Automattic, the company behind Word Press. But early conversations with Cook might have influenced his thinking, or helped him understand what was possible in his next chapter.

Ian Osborne: The Other Fixer in the Network

The emails also mention another figure: Ian Osborne. According to one message, Osborne was also in communication with Epstein around the same time, and Osborne mentions that he "Will call this afternoon. Was with Tim Cook this morning." This was sent in May 2013, about nine months after Sinofsky left Microsoft.

Osborne's email address was redacted in the released documents, but investigative reporting has identified him as Ian Osborne, a British investor and businessman who was known as a "fixer to billionaires" before he co-founded Social Capital Hedosophia with Chamath Palihapitiya in 2017. Social Capital became a major player in venture capital and SPAC launches during the 2020s.

Osborne being in contact with both Epstein and Cook, and mentioning that he had been with Cook that morning, suggests a broader network of people operating at the highest levels of business. These weren't random acquaintances. These were people who had direct access to major CEOs. They could pick up the phone and get meetings. They understood how to broker deals and facilitate introductions.

The presence of Osborne alongside Epstein in these communications suggests that there were multiple people playing the intermediary role during this period. Different people brought different connections and different expertise. Epstein brought finance and personal connections. Osborne brought his own network of wealthy individuals and his understanding of how capital flows.

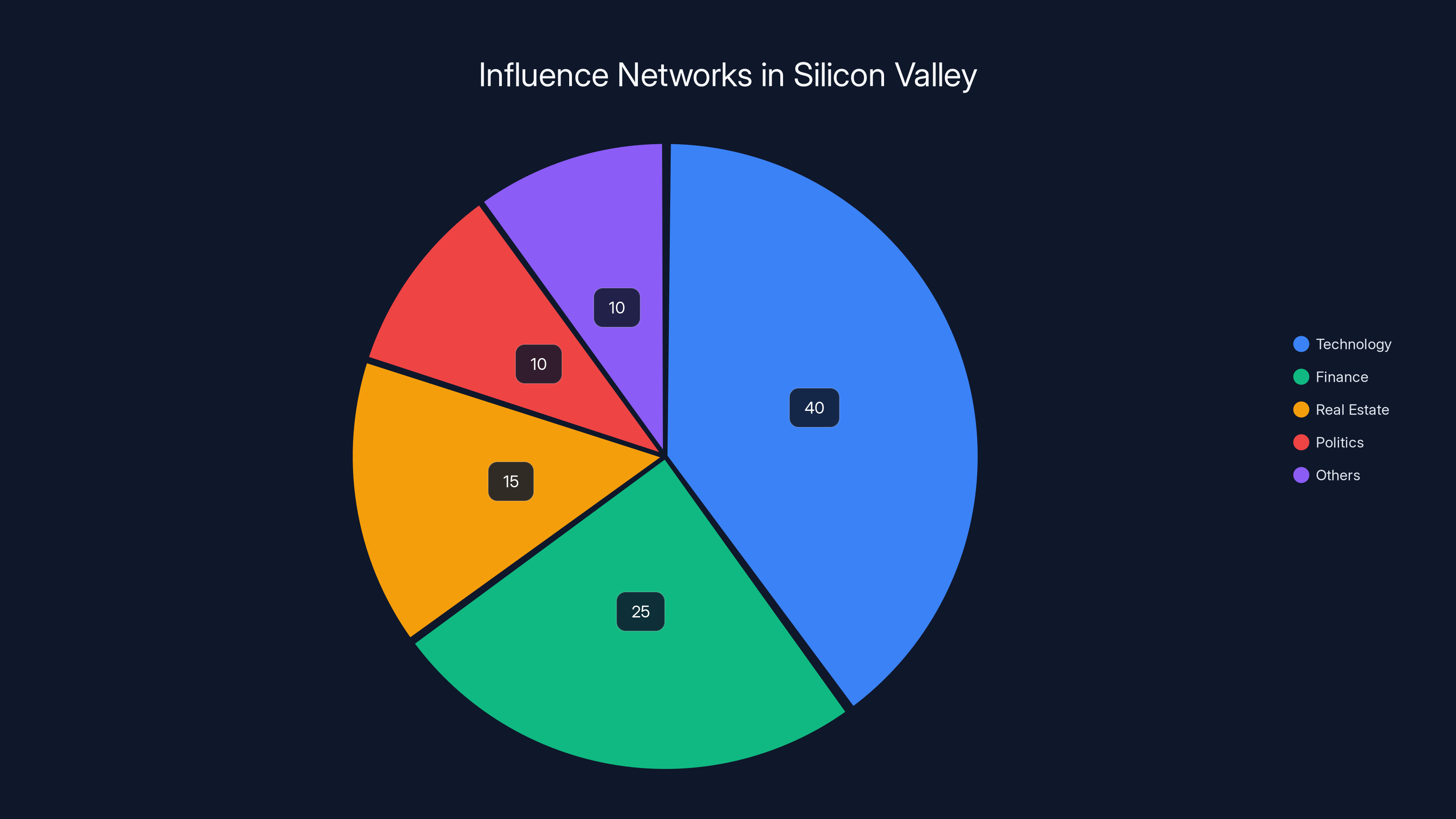

Estimated data shows technology as the largest sector influenced by Epstein's network, highlighting the hidden connections in Silicon Valley.

The Broader Context: Epstein's Network in Finance and Tech

What the Sinofsky emails reveal is that Epstein had cultivated relationships not just with politicians and Wall Street figures, but with major technology executives. By 2012, Epstein had been convicted and had served his sentence, yet he was still actively working as an intermediary and connector. How was this possible?

Part of the answer is that Epstein was extremely wealthy and extremely well-connected. He had built relationships over decades. When you're wealthy enough and connected enough, people overlook things they might otherwise object to. He could offer something valuable: access to other important people. That access was worth the cost of association for many people.

Another part of the answer is that by 2012, the financial crisis of 2008 was still fresh in people's minds. The banking and finance industries had faced intense scrutiny. Hedge fund managers, venture capitalists, and investment professionals were eager to navigate new terrain. Having a well-connected fixer who could facilitate introductions was genuinely useful.

The third part of the answer is that tech executives, even very sophisticated ones, sometimes operate in networks that are somewhat separate from the rest of society. They have their own social circles, their own restaurants, their own events. Once you're inside that circle, the usual rules sometimes work differently. If you're at Cook's level, you might not know all the details about everyone who approaches you. You might have an assistant screening meetings. You might rely on a colleague's judgment about whether someone is trustworthy. That creates opportunities for people like Epstein to operate.

What the Tim Cook and Sinofsky Situation Tells Us About Tech Leadership

The most interesting aspect of this story isn't that Epstein brokered a meeting. The most interesting aspect is what it reveals about how tech executives actually network and how decisions actually get made at the highest levels.

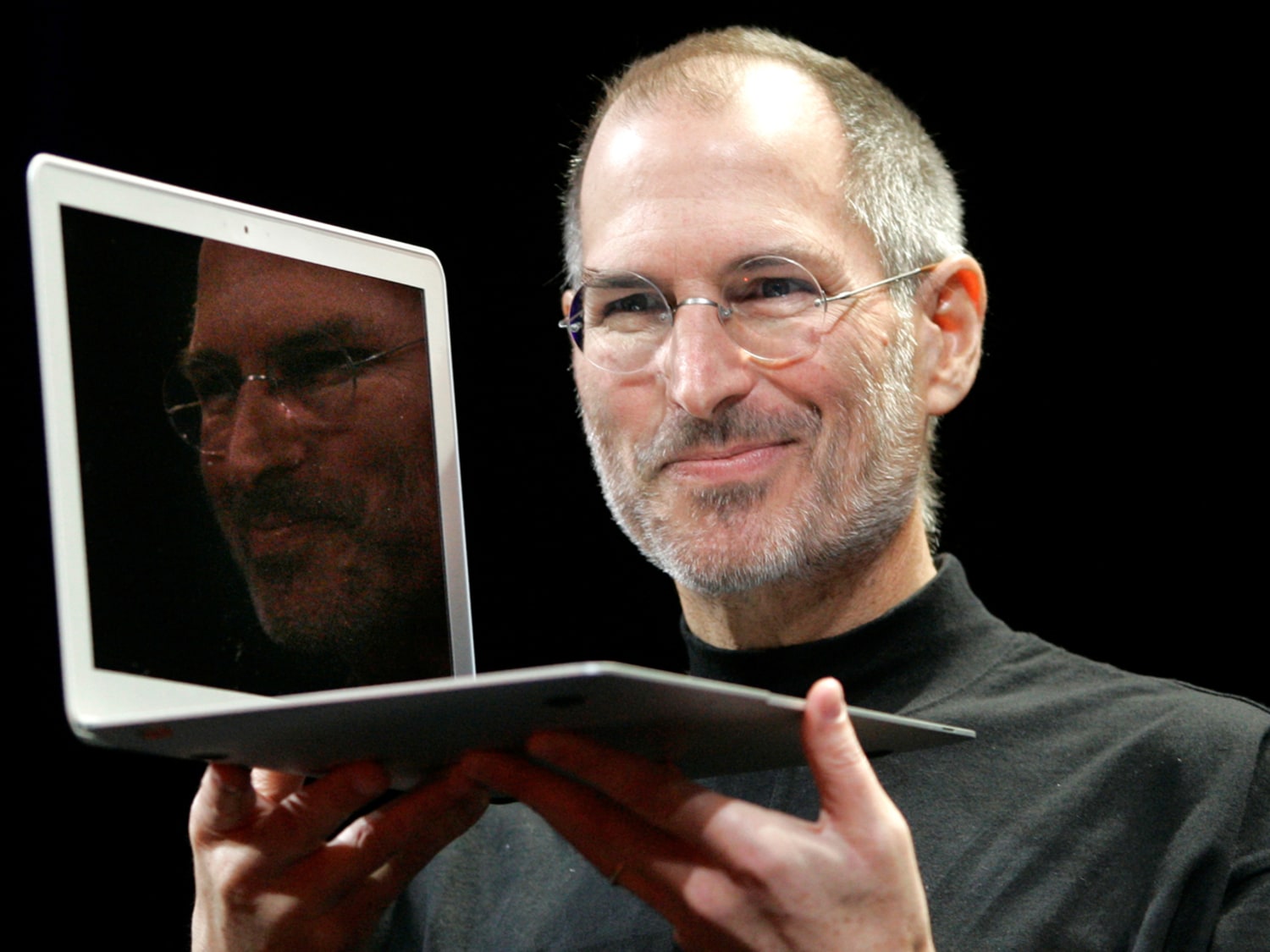

First, it shows that even at the CEO level, introductions matter enormously. Tim Cook didn't just randomly interview Sinofsky because he read about him in the news. Cook apparently agreed to meet Sinofsky because an intermediary made the introduction and vouched for his value. This is the kind of old-school business networking that doesn't always make it into Silicon Valley's public-facing mythology.

Second, it shows that personal relationships and informal networks are more important than most companies admit. Apple has formal HR processes, hiring procedures, and executive recruitment firms. But when it comes to really high-level talent, those formal processes sometimes matter less than who you know and who vouches for you. Sinofsky got the Cook meeting not because he applied for a job at Apple, but because he had an intermediary.

Third, it demonstrates that the technology industry's upper echelons are surprisingly interconnected. Cook, Sinofsky, Forstall, and dozens of other executives move in the same circles. They attend the same events. They're connected by the same network of people. This creates both opportunities and risks. Opportunities because information flows freely and partnerships can develop quickly. Risks because conflicts of interest can develop easily, and because the same network of people can make decisions that affect billions of users.

Fourth, it shows that context matters. In 2012, Sinofsky was at a vulnerable moment. He had just left Microsoft under somewhat contentious circumstances. Windows 8 was being criticized. He didn't have a clear next move. In that moment of uncertainty, being introduced to Tim Cook would have been extremely valuable. It would have broadened his options and made him feel like there were places where his experience was valued. Even if nothing came of the meeting with Cook, it would have been psychologically important.

Steven Sinofsky's career path shifted from founding Slope Ventures in 2013 to becoming CEO of Automattic in 2014, and leaving in 2018. Estimated data.

The Forstall Question: Why Did His Involvement Matter?

The fact that Epstein mentioned Forstall in his initial email about Cook meeting Sinofsky is worth examining more closely. Why would Cook care whether Sinofsky was working with Forstall? What was the dynamic between those two?

Scott Forstall had been the Senior Vice President of i OS at Apple. He oversaw the development of the i OS operating system, which powered the i Phone and i Pad. In October 2012, Apple announced that Forstall would be leaving the company. The official story was vague. Apple said Forstall would be "focusing on new ventures" but didn't provide details.

The reality was somewhat messier. Forstall had disagreed with other Apple executives, particularly Tim Cook and Jon Ives, about the direction of i OS design and development. There were also questions about Forstall's role in decisions around Maps, which had been a troubled launch. Forstall was forced out, and there was tension around his departure.

If Sinofsky was going to work with Forstall, that would have created a potential conflict for Cook. Here's why: Apple was entering a new phase. Forstall had been pushed out. Cook was consolidating power. If Sinofsky was going to help Forstall launch a competing venture or even just serve as a public validator of Forstall's work, Cook might have been concerned. He might have wanted to understand Sinofsky's loyalties and commitments before agreeing to meet.

The Epstein email addresses this by asking about it directly. This is sophisticated relationship management. Epstein wasn't just connecting two people. He was trying to understand and resolve potential friction before it became a problem.

The Barclays Connection: Epstein's Political Influence

The released documents also contain references to Epstein and Osborne working together on other business matters. Specifically, the Financial Times reported that in 2012, Epstein and Osborne were sending emails back and forth discussing efforts to help get Jes Staley appointed as CEO of Barclays Bank. Staley had been working at JPMorgan at the time.

This shows that Epstein wasn't just a social connector. He was also involved in corporate governance matters at major financial institutions. He was apparently trying to influence who became CEO of one of the world's largest banks. Combined with the tech connections, it paints a picture of someone who was embedded in networks of power across multiple industries.

Why is this relevant? Because it shows the scope of Epstein's influence. He wasn't just someone who knew important people. He was actively involved in shaping major corporate decisions. This makes his role in the Sinofsky-Cook introduction even more significant. When Epstein brokered that meeting, he was leveraging the kind of influence and network access that he used in much larger political and financial contexts.

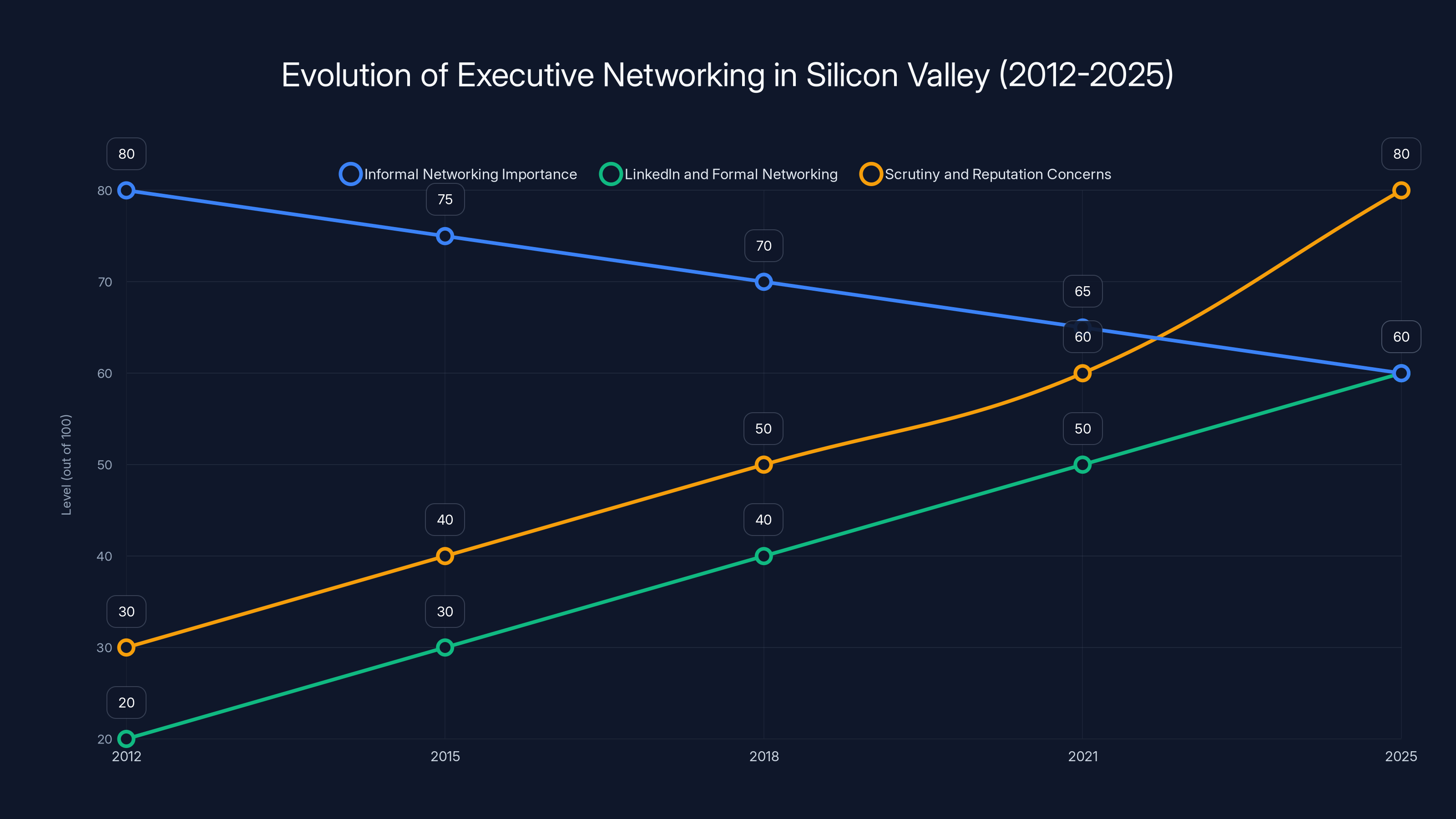

The importance of informal networking has decreased, while the use of LinkedIn and scrutiny over associations have increased from 2012 to 2025. Estimated data.

What Happened to Sinofsky After the Cook Meeting?

Historically, we know that Steven Sinofsky did not join Apple. Instead, he took a different path. In early 2013, a few months after the Cook meeting, Sinofsky launched Slope Ventures, a venture capital firm focused on productivity and enterprise software. That's a notable choice. It suggests that Sinofsky had decided that the best way forward wasn't to join another large company, but to become an investor and a founder.

Slope Ventures raised approximately $152 million in its first fund. Sinofsky then moved on to become CEO of Automattic, the company behind Word Press.com, in 2014. This was a dramatic change from his Microsoft role. Instead of managing a division with thousands of employees, he was now running a distributed, remote-first company. The experience was apparently not ideal. Sinofsky left Automattic in 2018 after less than four years in the role.

After Automattic, Sinofsky has been less visible in public corporate roles, though he remains active as an investor and advisor. His trajectory suggests that once you leave a major platform like Microsoft, finding the right next role is genuinely difficult. Even meeting with someone like Tim Cook doesn't necessarily lead anywhere. And that's an important reality check on this whole story.

The dramatic introduction, the interest from Cook, the intermediary effort from Epstein—in the end, Sinofsky made his own choices and went his own way. Sometimes the most valuable network doesn't actually change your path. It just gives you more options to consider.

The Epstein Files and What They Reveal About Corporate Networks

When thousands of pages of emails and documents from Epstein's correspondence were released by the Justice Department in 2025, the tech industry was surprised by what they contained. There were references to connections with tech CEOs, venture capitalists, and other figures in the technology world. The Sinofsky-Cook introduction was just one example.

What the files reveal is that for decades, Epstein had successfully positioned himself as a connector between different worlds. He understood finance. He understood real estate. He understood wealth management. And apparently, he understood the technology industry well enough to cultivate relationships with major figures like Cook.

How did he maintain these relationships? Several factors seem relevant. First, he was genuinely wealthy, which gave him the resources to host events, take people to dinner, and provide opportunities for networking. Second, he was apparently skilled at understanding what different people wanted and connecting them with others who could provide it. Third, he had decades of practice. By the time Sinofsky was consulting with him in 2012, Epstein had been building networks for forty years.

But there's also a darker aspect to this story. Epstein was using his position and relationships to maintain credibility and access despite his criminal conviction. People were apparently willing to work with him, consult with him, and accept introductions from him, despite knowing about his past. This says something uncomfortable about how power networks work. Sometimes the network itself matters more than the reputation of individual members. Sometimes people are willing to overlook serious character issues in exchange for the value someone provides.

What Apple and Microsoft Have Said

When The Verge first reported on these emails, they reached out to Apple for comment. Apple declined to comment on the record. Apple's response was essentially: we're aware of the story, but we're not going to discuss the private correspondence or the nature of the relationship between Sinofsky and Cook.

Microsoft was similarly silent. The company had already dealt with Sinofsky's departure more than a decade earlier. The severance package, the circumstances, the aftermath—all of that had been litigated or negotiated at the time. Revisiting it in 2025 in the context of the Epstein files wasn't something Microsoft was eager to do.

Neither company has suggested that anything inappropriate happened in the Epstein-mediated introduction. The meeting between Cook and Sinofsky appears to have been straightforward professional networking. The concern is more about the fact that it happened through Epstein as an intermediary, and what that says about the networks that these executives operate in.

The Broader Epstein Story in Technology

The Sinofsky-Cook meeting is one data point in a much larger story about Epstein's influence across multiple industries. The released files show connections to figures in finance, politics, entertainment, and academia. The technology industry connections are less numerous than the finance or politics connections, but they exist.

What made Epstein effective was that he understood the importance of relationships. He knew that phone calls and introductions mattered. He knew that being able to say "I know Tim Cook" or "I can get you a meeting with a venture capitalist" was valuable. He leveraged that knowledge relentlessly.

For Silicon Valley, the Epstein files are a reminder that the networks that drive the industry aren't entirely transparent. Major meetings happen through informal channels. Important decisions are influenced by people you might not have heard of. And sometimes the people facilitating those connections have complicated backgrounds.

Lessons About Power, Networks, and How Business Really Gets Done

The Sinofsky-Cook story offers several lessons about how business actually works at the highest levels, lessons that are often obscured by corporate PR and official narratives.

First, personal networks matter enormously. If you're trying to make a major career move, having the right introduction can be exponentially more valuable than having the perfect resume. This is partly about information asymmetry. CEO-level positions often aren't advertised. They're filled through relationships.

Second, intermediaries are powerful. The person who knows both sides and can facilitate an introduction has leverage and influence. This is especially true in contexts where direct introductions are difficult. If Sinofsky had tried to contact Cook directly, he likely would have been filtered out by assistants. Going through Epstein changed the equation entirely.

Third, context and timing matter. Sinofsky meeting with Cook happened at exactly the right moment—when Sinofsky was between jobs and exploring options, when Cook was consolidating power at Apple, when there was potential for mutual benefit. That timing wasn't accidental. Epstein understood the situation and acted accordingly.

Fourth, people at the highest levels of business are sometimes willing to overlook questionable backgrounds if someone provides sufficient value. Sinofsky apparently didn't have a problem consulting with Epstein despite his legal history. That willingness to work with someone despite complications speaks to the pragmatism of business at this level.

Fifth, the most valuable networks are often invisible to the public. We see the public announcements: who gets hired, who launches new ventures, who gets promoted. We rarely see the conversations and introductions that led to those decisions. The Epstein files lift the curtain on that invisible world, if only briefly.

The Evolution of Executive Networking in Silicon Valley

The way that executives network and find opportunities has evolved significantly since 2012. Back then, the methods that Epstein used were relatively standard. You had relationships. You leveraged them. You made introductions. That was how business worked.

Today, the landscape is different in some ways and similar in others. Linked In has made it easier to see how people are connected. But that also means that informal networks matter less, not more. It's easier to reach out to someone if you can see that you have a mutual connection.

At the same time, the highest-level connections still happen through informal channels. VCs still meet CEOs through mutual connections. Entrepreneurs still get introductions to major tech leaders through people they know. The basic dynamic that the Sinofsky story illustrates remains true.

What has changed is the level of scrutiny around who you associate with and who you take meetings with. In 2012, meeting with Epstein was easier. The public was less aware of his background. The social consequences of association were lower. By 2025, companies and executives are much more careful about their public-facing networks. They think more about optics. They worry more about being associated with controversial figures.

That's partly a good thing. It makes it less likely that someone like Epstein could maintain a prominent role in business networks. But it also means that casual networking is more fraught. People have to consider not just whether someone can be useful, but also whether being seen with them could damage their reputation.

Why This Story Still Matters in 2025

The Sinofsky-Cook email might seem like old news. It happened in 2012. Neither Sinofsky nor Cook ended up working together. Nothing major came of the introduction. So why does it matter now?

It matters because it illustrates something fundamental about how power operates in Silicon Valley. It's not entirely based on merit or expertise. It's based on relationships and access. A person with the right connections can get meetings with the most powerful people in technology. A person without those connections might never get those meetings, even if they're equally talented.

It matters because it shows that major tech executives were willing to work with Epstein well into his legal troubles, using his network and his access. That raises questions about judgment and about the culture of business at the highest levels.

It matters because it demonstrates that the most important decisions in technology—about who gets hired, who gets investment, who moves where—often happen through informal channels that aren't visible to the public. Understanding those channels is important for anyone trying to understand how Silicon Valley actually works.

Finally, it matters because it's a reminder that the story of Silicon Valley told in the press is often incomplete. We see the public moves: the hiring announcements, the product launches, the executive departures. We rarely see the conversations and introductions that preceded those public moves. The Epstein files give us a peek behind that curtain, and what we see is less meritocratic and more relational than the official narrative suggests.

Moving Forward: What This Means for Tech Leadership

As we move through 2025 and beyond, the tech industry is grappling with questions about ethics, governance, and culture. The Epstein files add important context to those discussions.

For tech companies, the lesson is clear: be thoughtful about who you associate with and who serves as an intermediary in your networks. The most convenient connection might not be the most appropriate one. Companies need to have internal processes and approval mechanisms for major executive-level meetings, not because executives are untrustworthy, but because outsourcing that responsibility to individual intermediaries creates risk.

For executives themselves, the lesson is about due diligence. Before accepting an introduction or working with an intermediary, it's worth asking questions about that person's background and reputation. The value of a single meeting is rarely worth the reputational risk of being associated with someone problematic.

For aspiring tech leaders, the lesson is sobering but important: your network matters enormously. But it also matters who's in that network and what associations you build. The best career moves are often made through trusted relationships. But those relationships have to be with people you actually trust, not just people who are useful in the moment.

The Sinofsky-Cook story, viewed in retrospect, is a cautionary tale about networks, influence, and the informal ways that power operates. It's not scandalous. It's not illegal. But it is revealing. And in an industry that prides itself on meritocracy and innovation, that revelation is worth taking seriously.

Key Takeaways

- Epstein brokered a meeting between Tim Cook and Steven Sinofsky after Sinofsky's Microsoft exit in 2012 for a $14 million severance package

- Cook expressed genuine interest according to Epstein's emails, though the meeting didn't result in Sinofsky joining Apple

- Executive-level opportunities in tech flow through informal networks and personal connections more than through formal hiring processes

- Epstein and intermediaries like Ian Osborne had significant influence in connecting powerful tech, finance, and business executives

- The story reveals how business networks operate largely invisibly, with important decisions made through relationships rather than merit-based processes alone

Related Articles

- Warren Demands OpenAI Bailout Guarantee: What's Really at Stake [2025]

- When VCs Clash: Inside the Khosla Ventures ICE Controversy [2025]

- Luminar's Collapse: Inside Austin Russell's Bankruptcy Battle [2025]

- Tech Workers Condemn ICE While CEOs Stay Silent [2025]

- Anthropic's Strategic C-Suite Shake-Up: What the Labs Expansion Means [2025]

- Meta Appoints Dina Powell McCormick as President and Vice Chairman [2025]