Introduction: When Founders Face Fallout

It's a story that feels almost scripted, except the stakes are real. Austin Russell built Luminar from scratch into what many believed would be the future of autonomous vehicle perception. The company raised hundreds of millions from top-tier investors. Russell himself became one of the youngest self-made billionaires. And then, in what felt like a matter of months, everything unraveled.

In January 2026, Russell found himself in a position no founder wants to be in: accepting a subpoena as his own company went through bankruptcy proceedings. But this wasn't just any legal demand. This was his company asking for his phone. This was the beginning of what would become a complex legal and financial entanglement that reveals far more about startup culture, governance failures, and the fragility of even the most promising ventures.

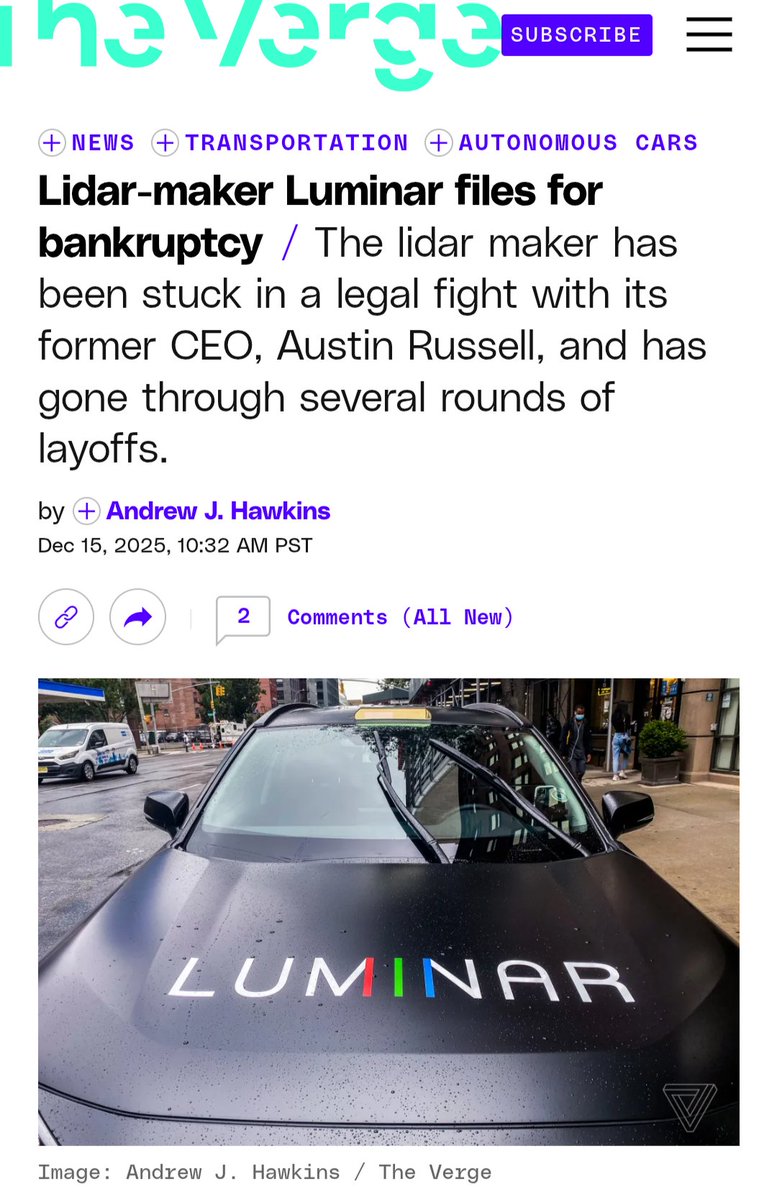

What happened at Luminar wasn't inevitable. It wasn't some unknowable market shift. It was a series of decisions, missteps, and governance failures that compounded over time. And when the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in December 2025, it forced a reckoning that nobody saw coming just two years prior.

This article digs into the complete story: how a lidar pioneer collapsed, what led to the bankruptcy, why Russell was pushed out, and what his legal battles reveal about founder accountability and corporate governance. We'll examine the subpoena standoff, the asset sales, the competitive pressures, and the broader lessons this case holds for the entire autonomous vehicle ecosystem.

The Rise of Austin Russell and Luminar

Austin Russell's origin story reads like something out of a startup mythology textbook. He dropped out of high school at 16 to start Luminar, convinced that lidar was the key to solving autonomous vehicle perception. While most founders were tinkering with apps or e-commerce plays, Russell was betting everything on optical physics and hardware.

The bet paid off spectacularly. Luminar secured funding from some of the most respected venture capital firms in Silicon Valley. Google's Eric Schmidt invested personally. Multiple automotive suppliers and manufacturers lined up to evaluate the technology. By 2021, when Luminar went public via SPAC merger, Russell was worth an estimated $2 billion at just 25 years old.

For years, Luminar seemed like one of the rare startup success stories that actually delivered. The company wasn't just raising money and making promises. They were shipping products. Volvo had committed to integrating Luminar's lidar into production vehicles. Mercedes-Benz signed a major deal. Chinese automotive companies were interested. The narrative was simple: Russell had been right all along, and Luminar would become the perception standard for autonomous vehicles.

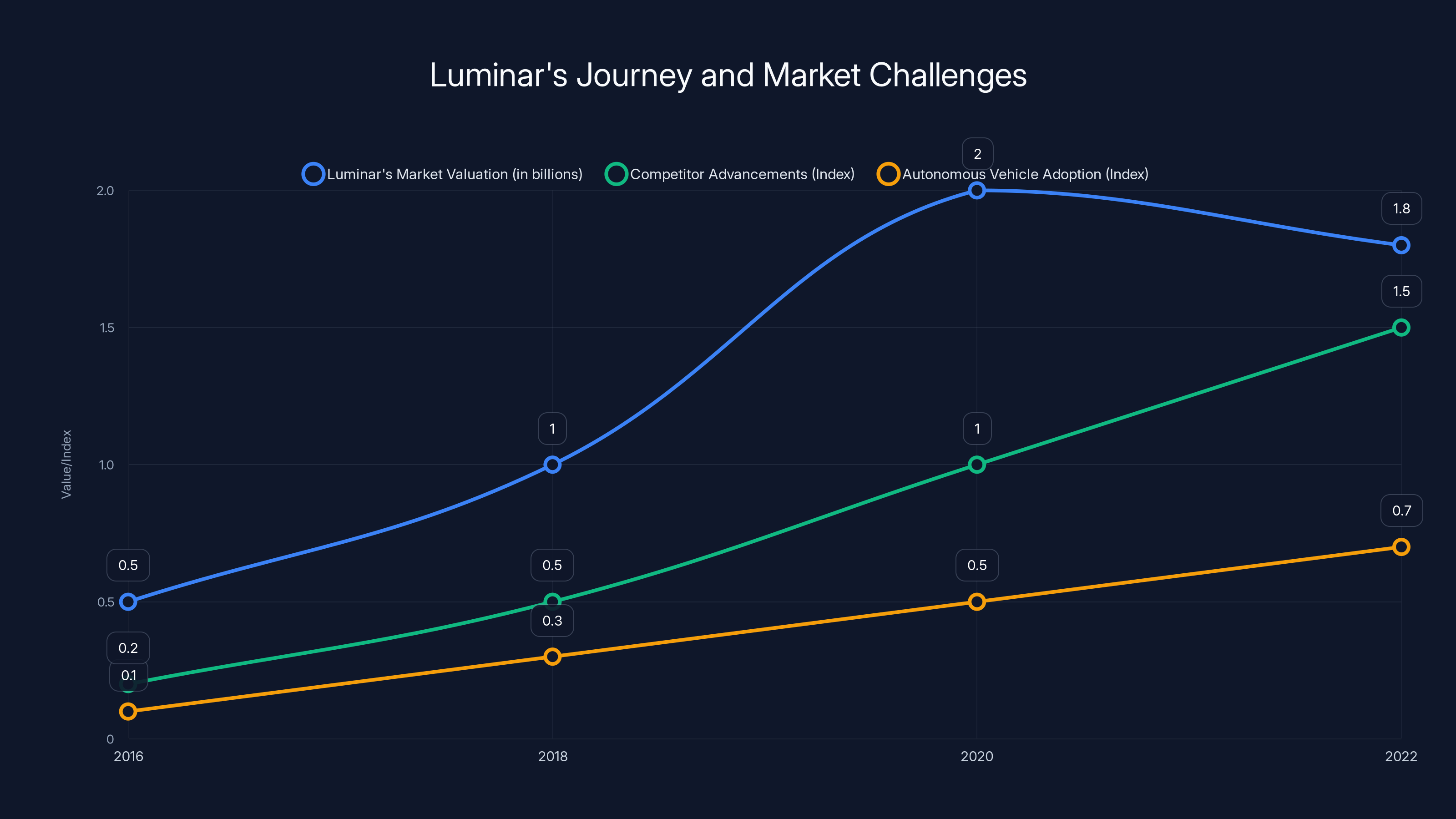

But here's where the story gets complicated. Being early and being right are two different things. Luminar was early, but the timeline for autonomous vehicles kept stretching. Full autonomous driving remained stubbornly elusive. And while Luminar waited, two things happened: competitors improved dramatically, and costs became an increasingly critical factor.

The company's burn rate was substantial. With hardware manufacturing and research, Luminar needed revenue to sustain operations. The contracts with Volvo and Mercedes-Benz sounded impressive in press releases, but they didn't arrive as quickly as expected. Meanwhile, Chinese lidar manufacturers were making cheaper sensors. Tesla questioned whether lidar was even necessary for autonomous driving. The narrative shifted from "when will lidar become standard" to "will lidar even be needed."

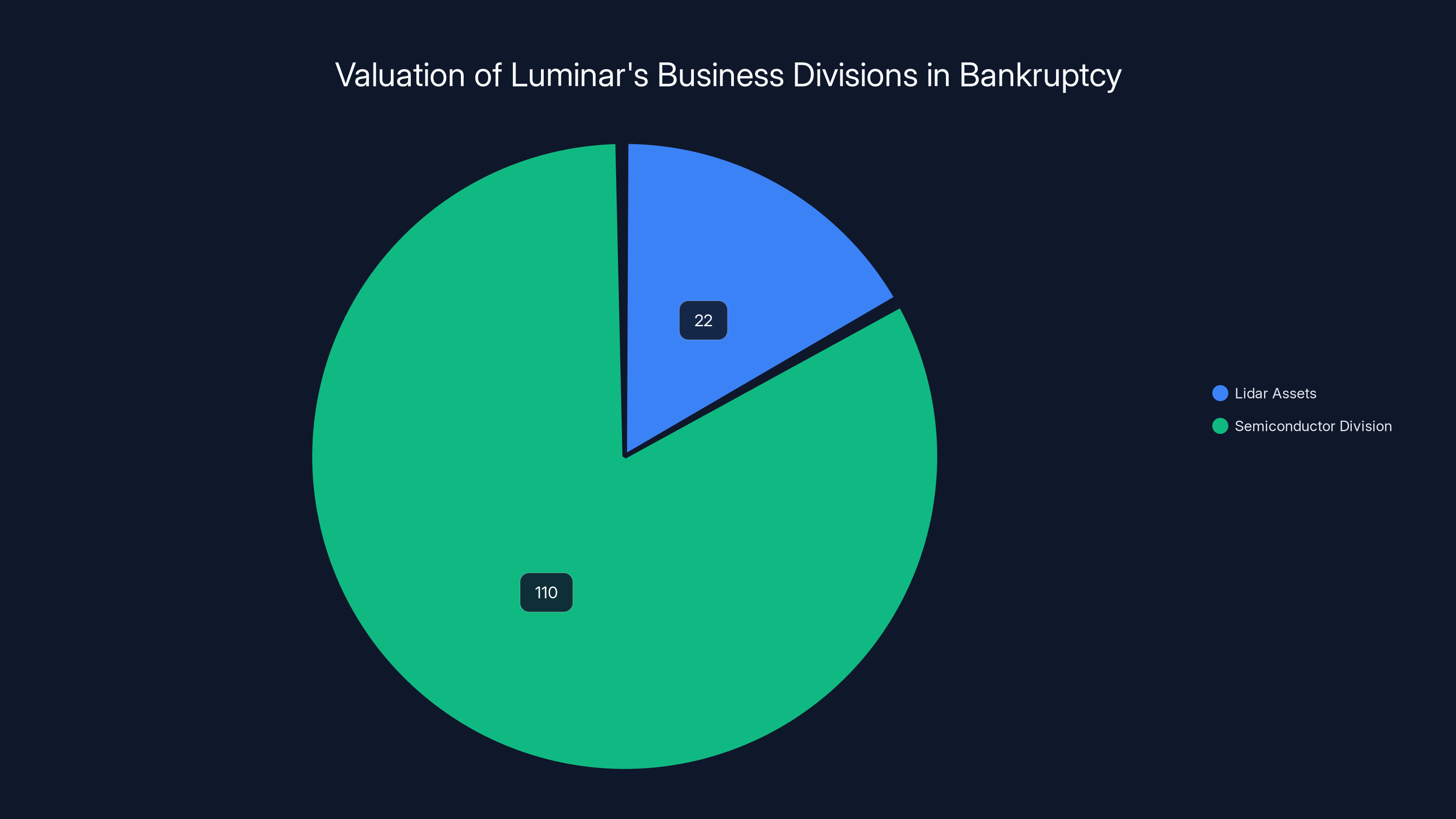

Luminar's semiconductor division was valued significantly higher at

The Ethics Inquiry That Changed Everything

In October 2025, Luminar announced that Austin Russell was stepping down as CEO. The official reason cited was an "ethics inquiry," but the details were sparse. This moment, more than anything else, marked the beginning of the end.

What exactly was this ethics inquiry about? Luminar never publicly disclosed the specifics. But the timing was significant. Russell's abrupt departure as CEO signaled to the market that something serious had occurred internally. Investors hate uncertainty. They hate founder drama even more. Within weeks of Russell's departure, confidence in the company evaporated.

The ethics inquiry itself suggests governance failures at the board level. Why did it take until October 2025 for an ethics issue to surface? Had the board not been properly monitoring governance? Were there warning signs that weren't addressed? Was Russell operating without sufficient oversight?

These questions matter because they speak to a fundamental issue in startup governance: founder-led companies often lack the checks and balances necessary to prevent problems from escalating. When your founder is also your visionary and your primary board voice, who's actually keeping watch?

Russell's departure left Luminar in a precarious position. He wasn't just the founder; he was the face of the company. His credibility, his vision, his narrative about lidar's future—these had all been central to Luminar's investor pitch. Without him in the CEO seat, investors started asking harder questions. And when those questions got asked, the answers apparently weren't reassuring.

The company tried to continue operations with new leadership, but the damage was done. Major customers had already begun losing confidence. Volvo and Mercedes-Benz, which had seemed like locked-in commitments, started reevaluating. If the founder had ethics issues serious enough to force his departure, what did that say about Luminar's trustworthiness as a supplier?

The Customer Exodus and Contract Losses

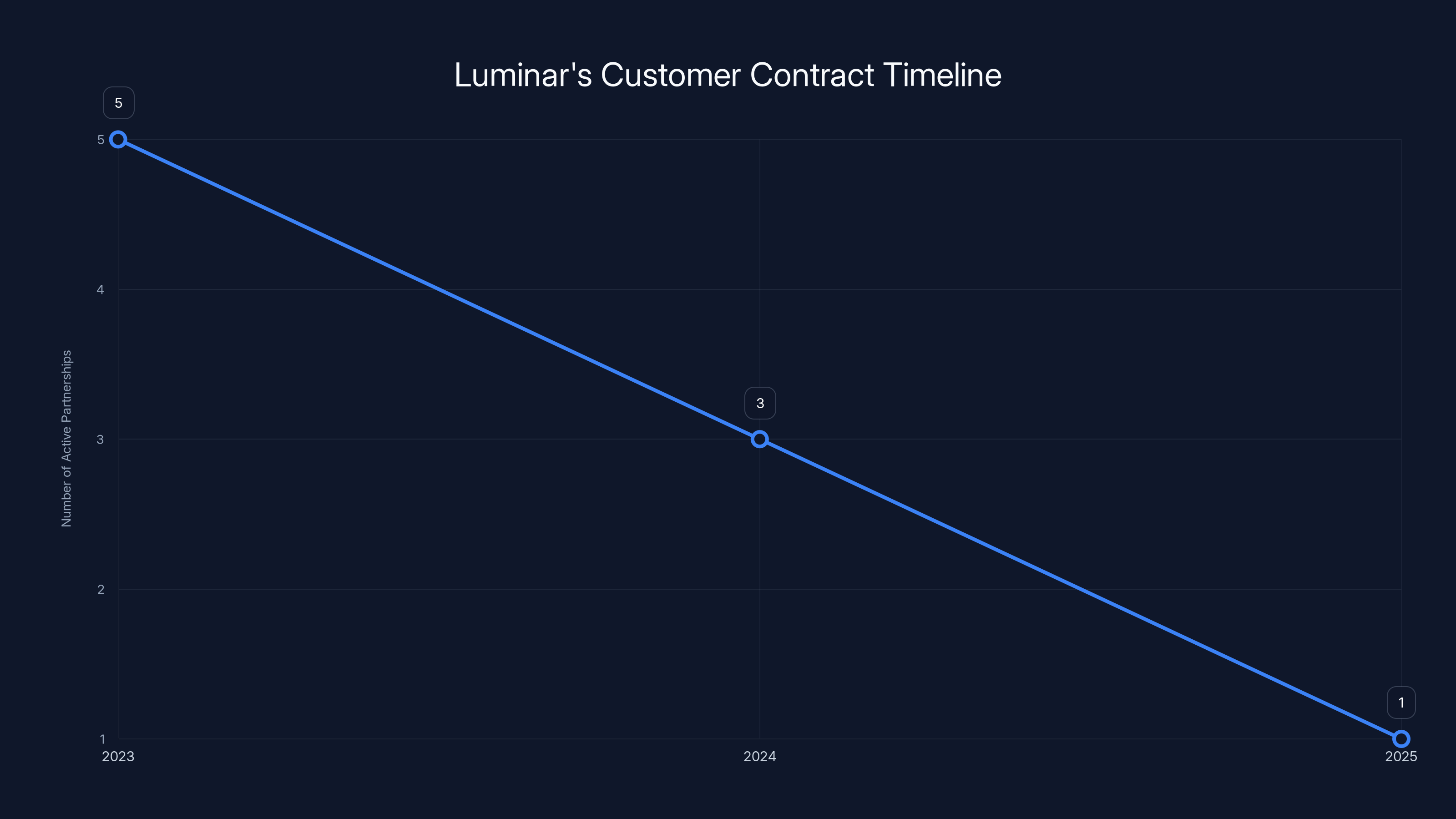

Luminar's bankruptcy filing in December 2025 mentioned specific customer contract cancellations. Volvo scaled back plans. Mercedes-Benz put Luminar on pause. These weren't small partners either. These were automotive giants with massive production volumes. A successful contract with Volvo alone could have sustained Luminar for years.

What's fascinating is how quickly these relationships deteriorated. In 2023, Luminar was publicizing these partnerships as proof of their technology's viability. By 2024, there was growing silence about customer milestones. By 2025, the partnerships were quietly unwinding.

This pattern suggests a few possibilities, none particularly comforting for Luminar investors. Either the technical roadmap was slipping (the sensors weren't performing as promised), or the price point was unworkable (Luminar's costs were too high), or the timeline for autonomous vehicle deployment kept getting pushed back (customers were deprioritizing lidar development).

Likely, it was all three. Luminar's sensors were excellent, but they were also expensive. Integration into production vehicles requires meeting specific cost and performance targets. As competitors improved, those targets became harder to hit. And as the timeline for real autonomous vehicles extended further into the future, customers had less urgency to commit resources and capital.

The Chinese lidar manufacturers played a crucial role here too. Companies like Robo Sense and Hesai were building sensors that were "good enough" for many applications, and at a fraction of Luminar's price. As the industry moved from "we need the best lidar" to "we need cost-effective lidar," Luminar's premium positioning became a liability.

Russell had been banking on a scenario where Luminar's superior technology would command premium pricing, similar to how NVIDIA's GPUs command premium prices in AI. But the lidar market didn't evolve that way. It became commoditized faster, and Chinese manufacturers were willing to compete on price in ways Luminar couldn't match.

Luminar's lidar assets were sold for

Russell's October Attempt to Buy Luminar

After stepping down in October 2025, Austin Russell apparently believed he could save Luminar—or at least its best parts—through a buyout. This is a move we've seen before with other founders who've had difficult exits from their companies. Russell wanted to control the narrative and the outcome.

His attempt to acquire Luminar at that time reveals something important: Russell apparently still believed in the core technology and saw value that the market wasn't recognizing. Maybe he thought that with him in full control again, without board constraints, he could execute better. Maybe he saw a path to profitability that new management couldn't see.

But by October 2025, Luminar's financial situation was already dire. The cash runway was short. Major customers had already signaled doubts. To successfully buy the company, Russell would have needed investors who believed in his vision. The irony is that those same investors had already backed Luminar at much higher valuations and were watching it collapse. Getting them excited about a new round at a bankruptcy price would be challenging.

The attempted buyout never materialized. And by December, Luminar filed for bankruptcy. Russell's opportunity to control his own company's fate slipped away.

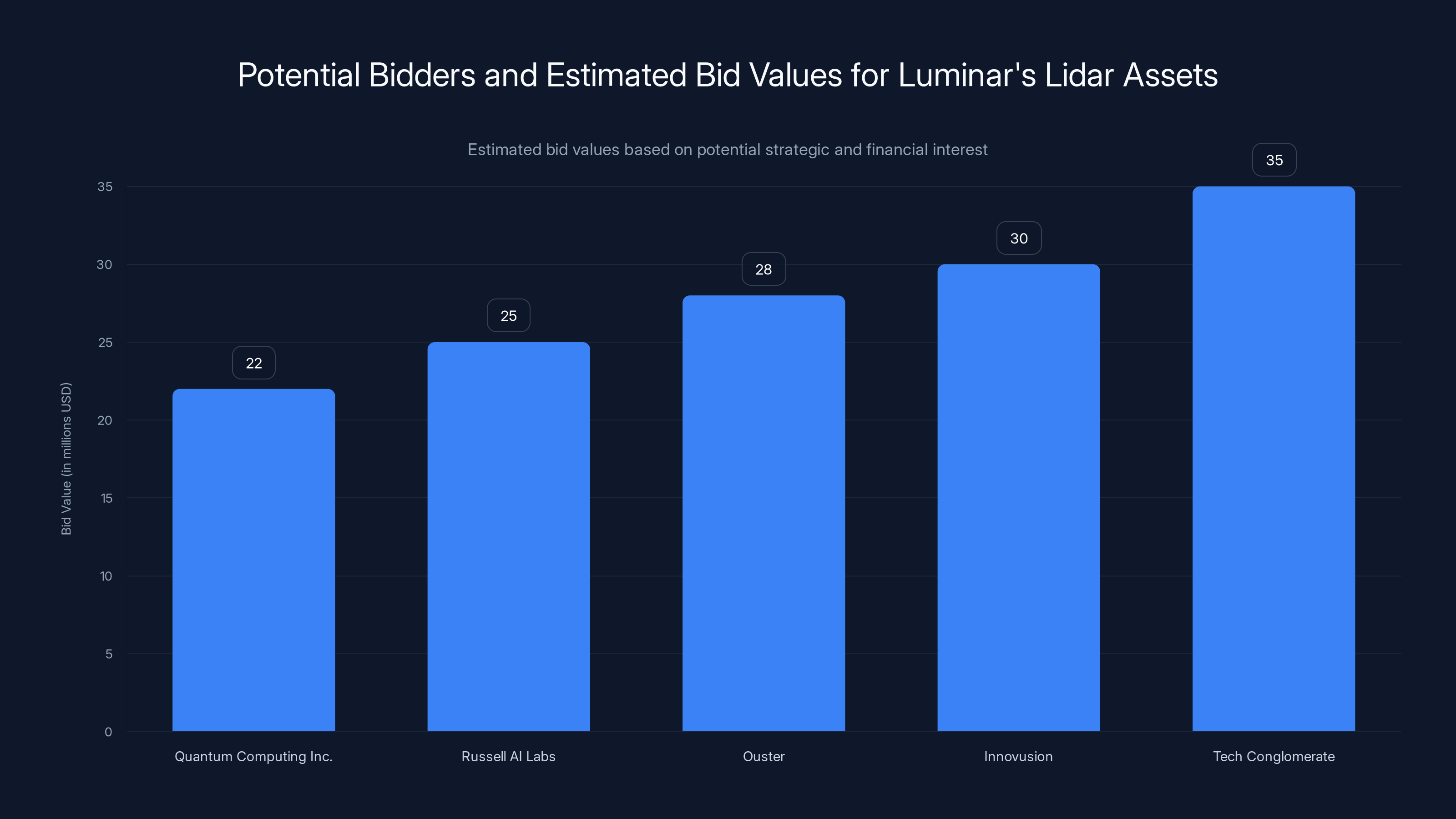

What's particularly interesting is that Russell's new venture, Russell AI Labs, apparently positioned itself as a potential bidder for Luminar's lidar assets in the bankruptcy auction. This suggests that even after being pushed out, Russell saw strategic value in the business. Whether that's realistic vision or wishful thinking remains to be seen.

The Lidar Technology Landscape

Understanding Luminar's collapse requires understanding the broader lidar market. When Luminar was founded around 2012, lidar was a nascent technology with few proven manufacturers. Velodyne was the established player, but for automotive applications, there was significant room for innovation.

Luminar's bet was on solid-state lidar using FMCW (frequency-modulated continuous wave) technology. This approach promised superior performance and reliability compared to traditional mechanical lidar. The company invested heavily in R&D, and by 2020, they had competitive products.

But here's the problem: everyone else was investing in lidar too. Over the span of 2015-2025, dozens of lidar companies emerged. Some were trying to build better mechanical lidar. Others, like Luminar, were pursuing solid-state approaches. Still others were experimenting with flash lidar or other novel architectures.

The result was an explosion of innovation but also intense competition. By 2023, you had companies like Ouster, Innovusion, Ibeo, Valeo, and numerous Chinese manufacturers all competing for the same customers. The technology was advancing across the board, which meant Luminar's technical advantages eroded faster than expected.

Meanwhile, Tesla and others continued to push the narrative that lidar might not even be necessary. If cameras and radar could handle most driving scenarios, why spend $1,000+ per unit on lidar? This philosophical debate, while unresolved technically, had massive business implications. It created uncertainty that customer suppliers didn't want to deal with.

The lidar market also proved to be more price-sensitive than Luminar anticipated. In many applications, "good enough" lidar at

The Quantum Computing Inc. Deal

When Luminar filed for bankruptcy, one of the first major transactions was a deal with Quantum Computing Inc. (QCI) to purchase lidar assets for

But context matters. In bankruptcy, assets are sold quickly and at distressed prices. $22 million for Luminar's operating lidar business represented some value recovery, even if it was a tiny fraction of what the business had been worth at its peak valuation.

QCI's interest in the assets is revealing. QCI is a quantum computing company, not a lidar specialist. Their interest in Luminar's lidar assets suggests they saw strategic value in entering the autonomous vehicle perception market or in acquiring IP and manufacturing capabilities at a discount.

This type of acquisition—where a struggling company's assets are bought by unrelated entities—is common in bankruptcies. The original investors get wiped out, but the business assets find new homes where they might be developed by companies with different economics or strategies.

Luminar also reportedly pursued a $110 million deal with QCI for its semiconductor division. This makes sense because lidar companies are really sensor companies, and sensors require custom semiconductors. If Luminar's silicon designs were valuable, a buyer might want them.

Luminar's valuation peaked in 2020, but competitor advancements and slow autonomous vehicle adoption have impacted growth. Estimated data.

The Subpoena Standoff Explained

Now we arrive at the core legal drama: Luminar's efforts to obtain information from Russell, specifically from his phone, as the company evaluated potential legal claims against him.

Why would a company in bankruptcy want its founder's personal phone? The answer involves complex corporate governance questions. If Russell engaged in misconduct, mismanagement, or self-dealing, Luminar's bankruptcy estate might have claims against him for damages. To evaluate those claims, lawyers need evidence.

Russell's phone would contain communications between Russell and investors, board members, and executives. It would show what Russell knew about company problems and when he knew it. It would reveal business decisions and their rationales. Essentially, the phone is a window into the decision-making of the company during the critical period when things started to fall apart.

But Russell had a legitimate concern: personal privacy. His phone wasn't company-issued. It contained personal information alongside any business-related content. Turning it over wholesale risked exposing his private communications, financial data, personal relationships, and other sensitive information.

The standoff reflected this tension. Russell agreed in principle that information should be shared, but wanted assurances that personal information would be protected. Luminar wanted unfettered access to get all relevant communications.

The fact that Russell was allegedly avoiding process servers at his Florida mansion is particularly telling. It suggests Russell's legal team was playing hardball and delaying tactics. Getting a subpoena served can be surprisingly difficult if someone is actively avoiding it. Russell's approach of turning away process servers added about two weeks to the timeline.

But ultimately, Russell folded. He agreed to accept the electronic subpoena. The agreement included provisions for protecting his personal information, addressing his original concerns. After accepting, Russell had 14 days to produce the phone contents (or 7 days to file a motion to quash).

What's notable is that Russell apparently only had one phone during his time at Luminar, despite Luminar's initial claims that he had two. This discrepancy is small but suggests confusion or exaggeration on Luminar's part, or perhaps Russell used different phones at different times and clarity was needed.

Evaluating Legal Claims Against Russell

Luminar's evaluation of potential legal claims against Russell raises important questions about founder accountability. What could those claims be?

Breach of Fiduciary Duty: If Russell, as CEO and a major shareholder, made decisions that primarily benefited himself rather than the company or shareholders, that's a breach. Did he allocate resources improperly? Did he make decisions with knowledge that they'd harm the company?

Self-Dealing: Did Russell transact with Luminar on terms that favored himself over the company? Did he take opportunities that belonged to Luminar for himself or his other ventures?

Misrepresentation to Investors: Did Russell make material misstatements to investors about the company's financial condition, technology, or customer relationships? If so, investors might have claims.

Mismanagement: Did Russell's decisions demonstrate such poor judgment that they amount to gross negligence or recklessness? (This is a high bar legally, but potentially relevant given Luminar's collapse.)

Corporate Waste: Did Russell approve expenditures or projects that had no reasonable business purpose?

The ethics inquiry that led to Russell's departure suggests at least one of these categories had issues. Luminar's bankruptcy lawyers needed his phone to gather evidence for evaluating claims and potentially negotiating settlements or pursuing litigation.

It's worth noting that bankruptcy proceedings often reveal uncomfortable truths about corporate governance and founder behavior. In some cases, founders had been making decisions that benefited themselves at company expense. In other cases, founders simply made bad judgments that, in retrospect, look like misconduct but weren't intentional.

Without seeing Luminar's actual legal theories, it's hard to know which category this falls into. But the fact that they're pursuing subpoenas and evaluating claims suggests they found something concerning in the information they did have access to.

The Regulatory and Governance Lessons

Luminar's collapse teaches several important lessons about startup governance that apply far beyond this one company.

Founder-Led Boards Are Risky: When the founder controls the board, who monitors the founder? Luminar apparently lacked sufficient independent board oversight. By the time an ethics issue surfaced in October 2025, significant damage had already accumulated. Better governance might have caught problems earlier.

Customer Concentration Risk: Relying on a few major customers (Volvo, Mercedes-Benz) created vulnerability. If those customers' autonomous vehicle programs slowed (which they did globally around 2024-2025), Luminar had no revenue diversity to fall back on.

Technology Risk Is Real: Luminar bet on a specific technology and approach. They were right about lidar being useful, but wrong about the timeline and their ability to maintain competitive advantages. Technology companies need diverse revenue streams and graceful paths to pivot.

Market Timing Matters: Luminar was right about lidar's potential but may have been 5-10 years too early. By the time autonomous vehicle adoption was closer to reality, the competitive landscape had changed dramatically. Early movers don't always win.

Transparency Builds Trust: Russell's abrupt departure with vague ethical reasons eroded investor and customer confidence. Clear communication about what happened and how it's being addressed might have contained the damage.

Cash Runway Is Critical: Hardware companies have longer development cycles and higher capital requirements. Luminar apparently didn't maintain sufficient cash reserves to weather the customer delays and market slowdown. Better financial planning might have extended runway long enough for market conditions to improve.

Estimated data shows a sharp decline in Luminar's active partnerships from 2023 to 2025, highlighting the rapid deterioration of customer relationships.

What Happened to Shareholders

For investors who bought Luminar stock at public prices, the bankruptcy was catastrophic. The company's equity was essentially wiped out. Shareholders had no claim on assets until creditors were satisfied. Given Luminar's debts and the asset sale prices, it's unlikely shareholders recovered meaningful value.

This is the nature of venture capital and growth stock investing. Companies win big or lose big. There's no middle ground. Luminar investors had bet on extraordinary growth and got bankruptcy instead.

For early-stage investors who bought in before the SPAC merger, the outcome was more nuanced. Some early VCs likely sold shares during the 2020-2021 period when the stock was trading at much higher levels. They got good returns despite the ultimate failure. Others, who held through the public listing, suffered significant losses.

Russell, with his billions of shares, was the single largest shareholder. His net worth evaporated along with the stock price. This is why his attempted buyout in October made some sense—he might have believed he could stabilize the company and recover value. But by then, the trajectory was too steep to reverse.

The Autonomous Vehicle Industry Impact

Luminar's collapse raised questions across the autonomous vehicle industry about commercialization timelines and the viability of sensor companies' business models.

For years, AV companies had been pitching investors on a simple timeline: development phase (2010-2020), deployment phase (2020-2030), autonomous driving everywhere (2030+). Luminar and other sensor companies had planned their business models around this timeline.

But reality diverged sharply. Autonomous vehicle adoption proved far more challenging than anticipated. Technical hurdles remained unsolved. Regulatory frameworks were slow to develop. Insurance and liability questions remained open. Consumer acceptance was lower than expected.

With the timeline slipping, the entire supply chain faced uncertainty. If full autonomous driving wasn't arriving in 2025 or even 2030, why invest heavily in specialized sensors today? This uncertainty depressed demand and compressed valuations across the sector.

Luminar's failure served as a warning: being early to an important market is risky if commercialization takes longer than expected. Companies need capital reserves, business model flexibility, and contingency plans.

For other lidar companies, Luminar's bankruptcy created both opportunities and challenges. Opportunities because Luminar's assets and technology came available at fire-sale prices. Challenges because it reinforced questions about whether lidar-specialized companies could become profitable businesses or whether they'd eventually be acquired at distressed valuations.

Russell AI Labs and the New Direction

After stepping down from Luminar, Russell launched Russell AI Labs. The focus appears to be artificial intelligence, a somewhat different direction from lidar hardware.

This pivot is telling. Russell had been a lidar missionary for over a decade. The move to AI suggests he either lost faith in the lidar market or wanted to diversify his portfolio. Alternatively, Russell may have seen that his credibility and funding ability were tied to the broader AI boom rather than lidar specifically.

Russell AI Labs being a potential bidder for Luminar's lidar assets in bankruptcy is interesting. It suggests Russell still sees value in the technology, even if it doesn't fit his new venture's primary focus. Perhaps he views lidar as a complementary technology for AI-driven applications.

The dynamics of Russell starting a new company while his old company goes through bankruptcy while he's the subject of litigation is complex. He's entitled to start new ventures, but it raises questions about focus and priorities. Did he move on too quickly? Is Russell AI Labs well-capitalized enough to be a credible bidder for Luminar's assets?

Public information on Russell AI Labs is limited, which is typical for early-stage ventures. But the timing and focus suggest Russell is trying to rebuild his reputation and wealth in a different market segment. Whether he'll achieve similar success with AI that he initially found with lidar remains to be seen.

Estimated data suggests that strategic buyers like tech conglomerates might place higher bids due to potential synergies, exceeding Quantum Computing Inc.'s opening bid of $22 million.

Timeline Reconstruction: How the Collapse Happened

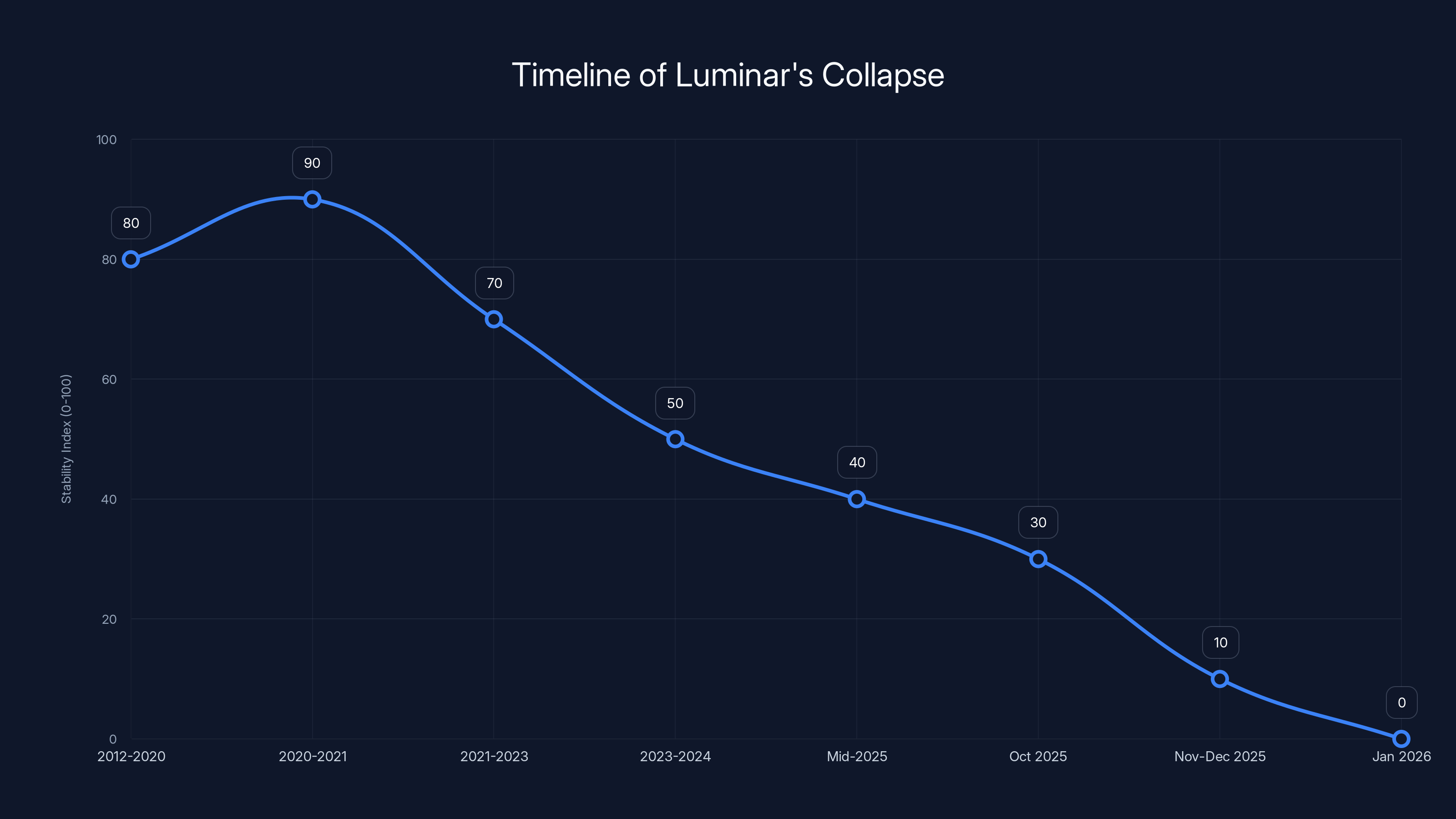

Reconstruction of Luminar's collapse looks roughly like this:

2012-2020: Founding, development, and early growth phase. Luminar raises capital, develops competitive lidar technology, attracts top talent.

2020-2021: Public market euphoria. Luminar goes public via SPAC merger. Stock price soars. Russell becomes a self-made billionaire. Investor and customer confidence is high.

2021-2023: Reality phase. Autonomous vehicle timelines slip. Customer integration efforts face technical and commercial challenges. Luminar's cash burn accelerates. Growth in manufacturing doesn't match demand expectations.

2023-2024: Stress signals. Major customer projects scale back. Volvo and Mercedes-Benz timelines extend. Luminar's stock price begins declining. Questions emerge about profitability and business model viability.

Mid-2025: Governance crisis. An ethics inquiry surfaces regarding Russell's conduct. This is serious enough to force his departure as CEO and push him from the board.

October 2025: Russell attempts to buy Luminar but fails to secure necessary financing or investor support. The market has already lost confidence.

November-December 2025: Rapid deterioration. With Russell out and major customers pulling back, the company's situation becomes untenable. Luminar files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

January 2026: Legal proceedings begin. Bankruptcy lawyers pursue discovery, including Russell's phone, to evaluate potential claims against him and understand what happened.

This timeline shows that while the final collapse was rapid, stress signals had been present for 18-24 months. Better monitoring, communication, and governance might have identified solutions earlier.

Implications for Startup Founders and Investors

Luminar's story carries specific lessons for both founders and investors.

For Founders:

Watch your corporate governance. A strong board with independent members and clear governance norms helps catch problems early. Russell's situation might have been different if a strong independent board was asking hard questions about strategy, customer relationships, and burn rate.

Build customer diversification. A company depending on three major customers has insufficient resilience. Spread risk across many customers, or maintain substantial cash reserves to weather customer concentration risk.

Communicate clearly when problems emerge. Russell's silent exit from the CEO role created exactly the opposite of the impression he probably wanted. Transparency and clear explanation would have been better.

Understand your market timing. Luminar was early to a good market, but "early" also means you burn through capital waiting for the market to develop. Founders need contingency plans if timelines slip.

For Investors:

Board composition matters. Where is founder oversight coming from? Are there independent directors with actual authority? Do they have enough information to govern effectively?

Understand unit economics in hardware. Hardware companies have high capital requirements and long development cycles. Ensure the company has capital runway sufficient to reach real revenue inflection points.

Monitor customer concentration. If three customers represent 70% of expected revenue, that's a red flag. Growth investors should push for customer diversification.

Watch for narrative shifts. When management changes the story about what's happening ("customers are scaling timelines" instead of "customers are losing interest"), investigate. This often indicates deeper problems.

Exit when governance concerns surface. Russell's ethics inquiry should have been a selling signal for equity investors. Governance problems rarely resolve themselves and often lead to larger issues.

The Bankruptcy Auction Dynamics

Luminar's bankruptcy process included an auction for the lidar assets. This auction is revealing about what the market actually valued.

Quantum Computing Inc.'s $22 million offer apparently was the opening bid, not an auction-winning price. Luminar scheduled an auction for the end of January 2026 to solicit higher bids. The company apparently hoped to generate competing offers that exceeded QCI's bid.

Russell's Russell AI Labs reportedly expressed interest in bidding, which would create an interesting scenario: the founder trying to buy back the assets from bankruptcy. Such scenarios have happened before (see Elon Musk and various X acquisitions). But for it to work, Russell needs capital and a convincing pitch to bankruptcy lawyers about why his bid should win.

Other potential bidders might include other lidar companies (Ouster, Innovusion, others), automotive suppliers seeking sensor technology, or technology conglomerates looking for IP assets.

The auction price would establish a market-validated valuation for Luminar's lidar business. If the winning bid is close to QCI's $22 million, that confirms the business was truly impaired and the bankruptcy valuation is realistic. If bids come in significantly higher, that suggests QCI got a steal and Russell or others saw real value.

The bankruptcy auction is essentially a correction mechanism. The capital market valued Luminar at near-zero in public trading. The bankruptcy auction would establish the actual enterprise value of the underlying business, divorced from equity holder expectations and sentiment.

The timeline illustrates Luminar's journey from growth to collapse, highlighting key events and phases. The company's stability index shows a sharp decline from 2023 onwards, culminating in bankruptcy by early 2026. Estimated data.

The Semiconductor Division Sale

Beyond the lidar asset sale, Luminar pursued a separate $110 million transaction for its semiconductor division. This separation makes sense because the businesses have different economics and customer bases.

The semiconductor division likely designed custom chips for Luminar's lidar sensors. But those designs might also have applications in other sensor types or systems. A buyer could potentially use those designs for other products, giving the IP broader value.

The $110 million valuation for the semiconductor division is noteworthy. It's five times higher than the lidar asset bid. This suggests the market values the chip design capabilities and IP more than the manufacturing business.

If this deal completes, it would help Luminar's creditors recover more value. The combined lidar and semiconductor sales (

What Happens to Employees

One aspect of Luminar's bankruptcy that received less public attention: what happens to the company's employees?

In a Chapter 11 restructuring, employees typically retain their jobs during the process but face uncertain futures. Some employees would be essential to running the business as it's sold or restructured, and they'd likely stay through the process. Others would face layoffs as assets are sold off and business operations contract.

Luminar had hundreds of employees across engineering, manufacturing, sales, and support functions. The bankruptcy would have triggered significant workforce reduction. Key engineers might be retained through asset purchase agreements where buyers hire them as part of the acquisition. Others would be terminated and offered severance.

The employee experience during this period would have been chaotic and demoralizing. Salary continues during bankruptcy, but there's uncertainty about when paychecks stop. Stock options and RSUs held by employees were nearly worthless. Employee morale would have collapsed.

This human dimension of corporate failure is sometimes overlooked in discussions of bankruptcy and business failure. Real people lost years of their careers and significant financial expectations due to corporate mismanagement and market timing failures.

Looking Forward: What's Next for Lidar

Luminar's failure doesn't mean lidar is doomed as a technology. But it does suggest that lidar sensor companies need different economics to survive.

Lidar is likely to remain important for specific applications: autonomous vehicle perception, robotics, 3D mapping, and other sensing applications. But the path to profitability for lidar specialists is narrower than previously believed.

Likely futures for the lidar sector include:

Vertical Integration: Lidar becomes a component of larger systems owned by automotive suppliers or OEMs, rather than an independent company. This reduces the capital requirements and aligns incentives.

Consolidation: Remaining lidar companies merge or are acquired by larger players, reducing competition and improving unit economics.

Cost Reduction: Manufacturing advances and volume production bring costs down substantially, making lidar viable for cost-sensitive applications.

Alternative Technologies: Novel sensor approaches (flash lidar, phase-shift lidar) prove superior or more cost-effective than mechanical or solid-state approaches, and the entire industry pivots.

Software Value: The real value shifts from the hardware to the software that processes lidar data. Hardware becomes commoditized while software captures the margin.

Luminar's specific technology might survive through acquisition (if buyers see value in the IP) or might be abandoned as buyers transition to their preferred architectures. Either way, the independent lidar company model faces significant headwinds.

Regulatory and Legal Frameworks Post-Bankruptcy

The bankruptcy process raises interesting regulatory questions about technology company governance and disclosure.

Should companies be required to disclose ethics inquiries and governance concerns to investors in real-time? Currently, disclosure requirements are vague. Companies have significant discretion in determining what's "material" and requires public disclosure.

Russell's departure with vague reference to an "ethics inquiry" likely should have triggered more detailed disclosure if SEC regulations were clearer. The lack of clarity allowed Luminar to maintain ambiguity, which arguably harmed investors.

Future regulation might tighten requirements for founder-CEO transitions, particularly when they involve governance concerns. Some argued for more transparency about founder conduct, conflicts of interest, and corporate governance practices.

The litigation between Luminar's bankruptcy estate and Russell will likely produce discovery disclosures (if not settled) that illuminate what the ethics inquiry involved. This could shape future expectations around founder accountability.

FAQ

What is Chapter 11 bankruptcy and how did it apply to Luminar?

Chapter 11 bankruptcy is a legal restructuring process that allows companies to continue operations while reorganizing debts and assets under court supervision. Luminar filed for Chapter 11 in December 2025, which allowed the company to evaluate strategic options including asset sales to creditors rather than immediately liquidating. This process gave Luminar time to find buyers for its lidar and semiconductor divisions rather than forcing an immediate liquidation that would have yielded lower asset prices.

Why did Austin Russell's phone become a central issue in the bankruptcy?

Luminar's lawyers sought Russell's phone to gather evidence for evaluating potential legal claims against him for misconduct, mismanagement, or breach of fiduciary duty. The phone would contain communications revealing what Russell knew about company problems, when he knew it, and what decisions he made. Russell initially resisted, citing privacy concerns about personal information on the device, but eventually agreed to accept the subpoena with protections for non-business-related content.

What caused Luminar to lose major customer contracts?

Luminar lost contracts with Volvo and Mercedes-Benz due to multiple factors: autonomous vehicle development timelines slipped further into the future, Chinese lidar competitors offered cheaper alternatives, uncertainty about whether lidar was even necessary for autonomous driving, and concerns about Luminar's governance and leadership following Russell's departure. When the founder of your key supplier is forced out due to ethics concerns, major customers reevaluate their relationships.

How much was Luminar's business actually worth in bankruptcy?

Luminar's lidar assets were valued at approximately

What could other lidar companies learn from Luminar's collapse?

Luminar's failure demonstrates that being first to market with good technology doesn't guarantee success if: 1) Market timelines slip longer than expected, draining capital reserves; 2) Governance structures lack adequate founder oversight; 3) Customer concentration is too high (relying heavily on a few large partnerships); 4) Business model economics depend on premium pricing that competitors can undercut; 5) Communication about company problems is vague and creates uncertainty. Other lidar companies should maintain diverse customer bases, substantial cash reserves, strong governance, and realistic timelines.

Could Russell's attempt to buy back Luminar have worked?

Unlikely, given the timing and circumstances. By October 2025, when Russell attempted the buyout, the company's financial condition had deteriorated substantially and investor confidence had evaporated. Convincing lenders or investors to finance a buyout of a failing company by its departing founder would have required extraordinary circumstances. Russell apparently couldn't secure the necessary capital, and the bankruptcy filing followed shortly after.

What happens to Luminar shareholders in the bankruptcy?

Luminar shareholders essentially lost their entire investment. In bankruptcy, secured creditors are paid first, followed by unsecured creditors, with equity holders receiving nothing unless assets exceed creditor claims. Given Luminar's debt levels and the modest asset sale prices, shareholders recovered nothing. This is the inherent risk of equity investing: high potential returns offset by the risk of total loss in failed companies.

How does the lidar market evolve after Luminar's collapse?

Luminar's bankruptcy confirms that standalone lidar sensor companies face structural challenges. Future developments likely include: consolidation through acquisitions, vertical integration into larger automotive supplier organizations, significant cost reductions through manufacturing innovation, possible shift to alternative sensor architectures, and migration of value from hardware to software. The market for lidar technology itself remains viable, but the business model for independent lidar specialists is fundamentally challenged.

Conclusion: What the Luminar Story Means

Austin Russell's journey from teenage founder to billionaire CEO to bankrupt company founder facing subpoenas is a striking reminder that technology alone doesn't guarantee success. Luminar built excellent lidar sensors. The technology worked. The science was sound. But lidar excellence meant little when customers postponed deployment, competitors reduced prices, timelines slipped, and governance failures eroded confidence.

The subpoena that Russell finally accepted isn't just a legal procedural matter. It's a symbol of the broader reckoning: when a company fails this dramatically, someone has to be accountable. Investors want to understand what happened and why. Creditors want to know if they can recover something. And the company's bankruptcy estate, acting on behalf of stakeholders, has legitimate interests in understanding whether founder decisions contributed to the collapse.

Russell's situation also reveals the vulnerability of founder-led companies without adequate governance. When one person has visionary power, strategic authority, and major shareholdings, who's actually monitoring that person? The answer at Luminar appears to have been: not enough. By the time an ethics inquiry surfaced in October 2025, significant damage had accumulated.

For other founders and companies, Luminar offers concrete lessons about governance, customer diversification, cash runway, and the difference between being early and being right. Being early to a large market is valuable only if you have the capital, focus, and execution to survive until the market develops. Luminar couldn't.

The larger autonomous vehicle industry also faces questions. If specialized sensor companies can't survive despite having first-mover advantages and solid technology, what does that mean for the sector? It suggests the economics of autonomous vehicle development are even more challenging than previously believed. It takes longer, costs more, and requires more resilience than early narratives suggested.

Russell's pivot to Russell AI Labs suggests he's moving forward and trying to rebuild. Whether he succeeds in AI where he failed in lidar depends on whether he's learned from Luminar's experience or whether similar patterns will repeat. His potential bid for Luminar's assets in bankruptcy is interesting, but secondary to the larger question of whether Russell can succeed in his next venture.

Ultimately, Luminar's story is one about market timing, governance, and the gap between vision and execution. It's a reminder that even billion-dollar valuations and promising technology offer no guarantees. Companies fail not because the market was wrong about the potential of their technology, but because of much more mundane reasons: cash ran out, customers delayed decisions, competitors improved faster than expected, and leadership faced challenges it couldn't overcome.

That's the unglamorous reality beneath the headlines about bankruptcy and subpoenas. It's also the reality that explains why venture capital has such high failure rates and why success, when it comes, is genuinely remarkable.

Key Takeaways

- Luminar collapsed from a $2 billion valuation to bankruptcy within 3-4 years due to market timing failures, customer concentration risk, and governance issues.

- Austin Russell's forced departure in October 2025 due to an ethics inquiry was the tipping point that eroded investor and customer confidence.

- The company lost major contracts with Volvo and Mercedes-Benz as autonomous vehicle timelines slipped and cheaper Chinese lidar alternatives emerged.

- Founder-led boards without adequate independent oversight failed to catch and address governance concerns until it was too late.

- Luminar's bankruptcy revealed that being early to market with good technology isn't enough if you lack the capital runway and customer diversification to survive market delays.

Related Articles

- The Dark Side of Hot Seed Rounds in AI: When Founders Keep the Money [2025]

- Physical AI: The $90M Ethernovia Bet Reshaping Robotics [2025]

- Emergent Raises $70M Series B: Inside the AI Vibe-Coding Boom [2025]

- 55 US AI Startups That Raised $100M+ in 2025: Complete Analysis

- Startup Battlefield 200 2026: Complete Guide for Founders [2025]

- AI Bubble Myth: Understanding 3 Distinct Layers & Timelines

![Luminar's Collapse: Inside Austin Russell's Bankruptcy Battle [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/luminar-s-collapse-inside-austin-russell-s-bankruptcy-battle/image-1-1768946872562.jpg)