The Bluetooth Security Crisis Nobody's Talking About

Your headphones are listening. Your speakers are vulnerable. And you probably don't even realize it.

Last year, security researchers at KU Leuven University in Belgium uncovered something genuinely terrifying: a fundamental flaw in how over 300 million audio devices handle wireless connections. The vulnerability lives inside Google's Fast Pair protocol, the same convenience feature that lets you connect your earbuds to your Android phone with a single tap. Turns out, that same "single tap" convenience is being weaponized by attackers.

What makes this crisis different from typical security patches? Most of us ignore those notifications. We're busy. We'll update later. But this vulnerability doesn't work that way. An attacker doesn't need your permission. They don't need to send you a link or trick you into opening anything. They just need to be within 50 feet of your device. That's a coffee shop. That's your commute. That's basically anywhere.

The researchers, collectively calling their work "Whisper Pair," demonstrated techniques that would let anyone nearby silently pair with your audio accessories and take complete control. They could turn on your microphone and listen to everything around you. They could play audio through your speakers at full volume. They could track your physical location in real time. And here's the part that should really concern you: it works even if you're an iPhone user who's never touched a Google product in your life.

Across 17 different audio accessories from 10 major manufacturers including Sony, JBL, Marshall, Xiaomi, Nothing, One Plus, Soundcore, Logitech, Jabra, and Google itself, the same vulnerability exists. These aren't obscure devices. These are the headphones people actually use. The speakers in living rooms. The earbuds on commuter trains.

What's genuinely alarming isn't just the technical flaw. It's the response. Google published a security advisory acknowledging the issue. Some manufacturers released patches. But here's what researchers and security experts agree on: almost nobody will install them. The patches require downloading manufacturer apps that most users don't even know exist. Your Sony headphones won't automatically update themselves. Neither will your JBL speakers. You have to actively seek out the patch, find the right app, and manually apply it. In the real world, that almost never happens.

This article breaks down everything you need to understand about this vulnerability: how it works, which devices are actually at risk, what patches exist, and most importantly, what you should do right now to protect yourself.

TL; DR

- Over 300 million audio devices are vulnerable through Google's Fast Pair protocol, affecting headphones and speakers from Sony, JBL, Marshall, and others

- The Whisper Pair attack lets anyone within 50 feet hijack devices, enable microphones for eavesdropping, play audio remotely, or track locations in real-time

- Patches exist but require manual installation through manufacturer apps—most users will never know they need to update

- Location tracking works even on iPhones because some devices support Google's Find Hub geolocation feature

- The fix situation is messy: Google patched its own devices, some manufacturers released updates, but a patch bypass was discovered almost immediately

Cost constraints and patch deployment issues are major factors in IoT security failures, with user behavior also playing a significant role. (Estimated data)

Understanding Fast Pair: Convenience vs. Security

Before we dive into the vulnerability, you need to understand what Fast Pair actually is and why Google designed it the way they did.

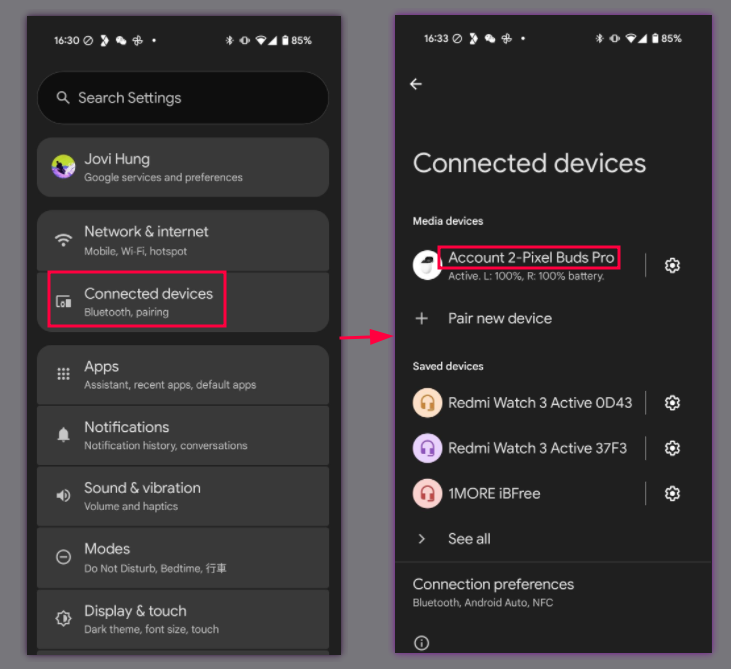

Back around 2017, Google looked at the Bluetooth pairing process and saw a problem. It was annoying. When you wanted to connect wireless earbuds to your Android phone, you'd have to dig into settings, find the Bluetooth menu, enable pairing mode on your headphones, wait for them to show up in a list, tap them, and hope nothing went wrong. For mainstream consumers, this was friction. Apple solved this differently with their Air Drop-like model and tighter integration, but Google needed their own approach.

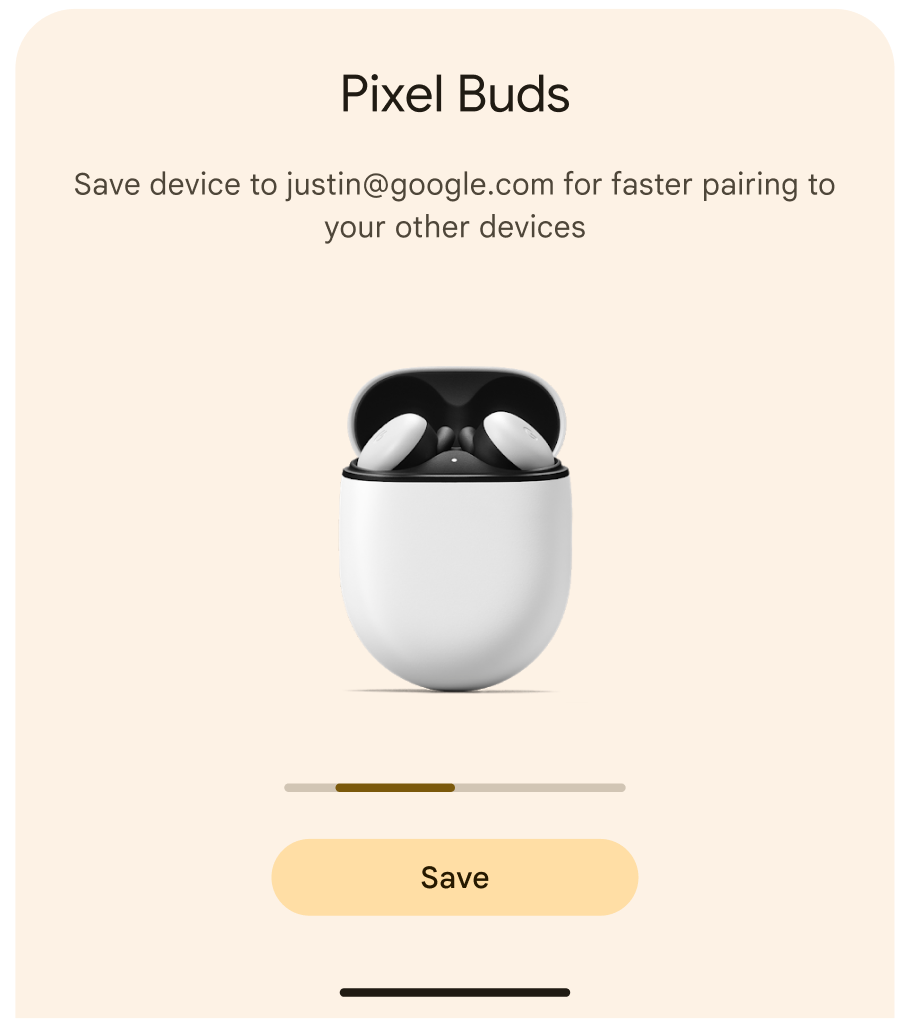

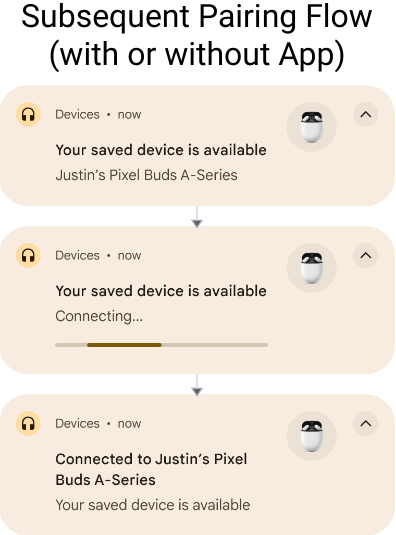

Fast Pair simplified everything. You turned on your headphones near an Android phone, and a notification popped up asking if you wanted to pair. One tap. Done. That's it. No menus. No settings. No waiting for device lists to refresh.

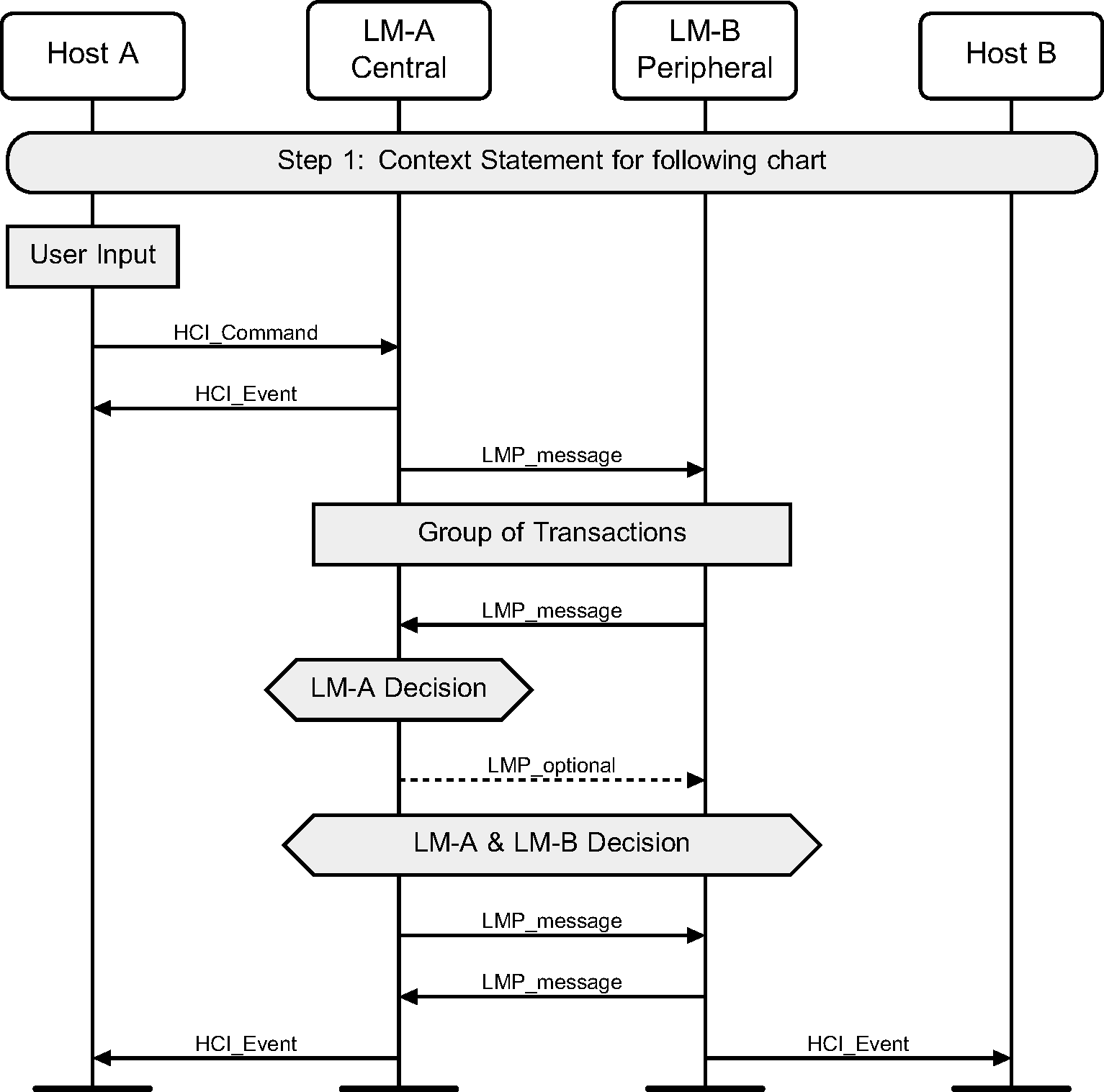

The protocol works by letting authenticated accessory devices broadcast information about themselves using Bluetooth's advertisement mechanism. When your phone sees this broadcast from a recognized device, it shows that notification. The pairing then happens using established Bluetooth security protocols like Bluetooth Classic or Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) with encryption.

On paper, this is secure. Google designed it carefully. The issue isn't with Bluetooth's core encryption. It's with how individual manufacturers implemented Fast Pair on their specific devices.

When you're connecting earbuds or speakers, the manufacturer's implementation needs to verify that the person connecting is authorized to do so. But here's where things get messy: different manufacturers took shortcuts. Some didn't properly validate that a connection request was actually coming from an authorized device. Others didn't encrypt certain parts of the pairing process that should have been encrypted. A few didn't implement rate limiting, which means an attacker could try connection attempts repeatedly without the device pushing back.

These aren't flaws in Google's basic Fast Pair concept. They're implementation details where manufacturers got it wrong. But they exist across devices from multiple companies, which suggests this wasn't just one manufacturer being careless.

Estimated distribution of vulnerable devices shows Sony and JBL as having the highest percentage of devices affected by the WhisperPair vulnerability. Estimated data.

The Whisper Pair Attack: How It Actually Works

Let's talk about what researchers actually demonstrated. Understanding the mechanics helps explain why this is such a big deal.

The attack breaks down into roughly three phases: discovery, pairing exploitation, and control.

Phase One: Discovery and Preparation

First, an attacker needs to find a device to target. They'll have a list of vulnerable device models and their Fast Pair signatures. When someone nearby turns on their Sony headphones or JBL speaker, the attacker's equipment detects the advertisement signal. They know exactly what model it is. They have precompiled information about that model's vulnerabilities.

This doesn't require fancy equipment. A modified smartphone running custom software or a $50 Bluetooth radio dongle on a laptop works fine. The attacker doesn't need to look like they're doing anything suspicious. They're just sitting in a coffee shop with their computer.

Phase Two: Exploiting the Pairing Flaw

Here's where the actual vulnerability manifests. Different devices have different flaws, but the researchers documented several patterns:

Some devices don't properly verify that incoming pairing requests match the device's expected identity. The attacker sends a pairing request that mimics a legitimate connection attempt. The device, due to incomplete validation, accepts it. The Bluetooth protocol itself tries to establish encryption, but because the initial handshake was compromised, the attacker ends up in a state where they have some level of access.

Other devices have timing issues. The validation happens at the wrong point in the pairing process, creating a window where an attacker can inject themselves.

A few devices don't implement proper cryptographic verification of certain handshake messages, which means an attacker can essentially bypass the authentication by providing fake but structurally valid responses.

Phase Three: Taking Control

Once the attacker has exploited the pairing flaw, they essentially own the connection. What they can do depends on the specific device, but the possibilities are genuinely disturbing:

Microphone hijacking: Many Bluetooth headsets and speakers have microphones. An attacker can remotely activate the microphone and listen to everything the device hears. Your ambient environment becomes transparent to them. They're hearing your conversations, your environment, potentially anything you say near your device.

Audio injection: The attacker can play any audio they want through the device at any volume. They could blast a loud noise to startle you. They could inject fake voices to manipulate you. They could play disturbing content. The point is, they have complete control over what you hear.

Call hijacking: If the device is being used for phone calls or video meetings, an attacker can interrupt, record, or manipulate those calls.

Location tracking: And here's the truly unsettling part. Some devices, particularly from Sony and Google, support integration with Google's Find Hub, a geolocation feature that lets you find your lost devices on a map. The researchers discovered they could exploit the same pairing vulnerability to access this tracking feature. This means they could follow a target's location in real-time, with precision, without the target knowing anything is happening.

The location tracking works through a combination of Bluetooth proximity data and cellular triangulation. Once an attacker controls the device, they can query its location at regular intervals and track movement patterns.

The Affected Devices: Who's Vulnerable

Let's get specific about which devices are actually at risk. The researchers tested 17 models across 10 different manufacturers.

From Sony, the vulnerable models include their WF-C700N and Link Buds S earbuds, which are popular mid-range wireless earbuds sold in major retailers worldwide. Sony also has vulnerable speakers in their SRS-XB series.

JBL's vulnerable devices include their Flip 6 and Flip 7 speakers, which are extremely common. If you've ever been to someone's house with a portable Bluetooth speaker, there's a decent chance it was a JBL Flip. They also have issues with their Tour Pro 2 earbuds.

Marshall speakers including their Stanmore III, Acton III, and Emberton speakers all show the vulnerability. These devices tend to be in home studios and music production setups.

Xiaomi's Redmi brand earbuds have the flaw. This matters more globally than domestically because Xiaomi has massive market share in Asia and emerging markets.

Nothing's Ear and Ear Pro earbuds are affected. Nothing is a newer brand, but their products have gained significant traction.

One Plus earbuds (One Plus Buds Pro 2 and other models) are vulnerable.

Soundcore's Liberty 4 Pro and other models from this brand, which is owned by Anker, are affected.

Logitech's Wonderboom 4 speaker has the vulnerability.

Jabra's various headsets and earbuds show the flaw across multiple models.

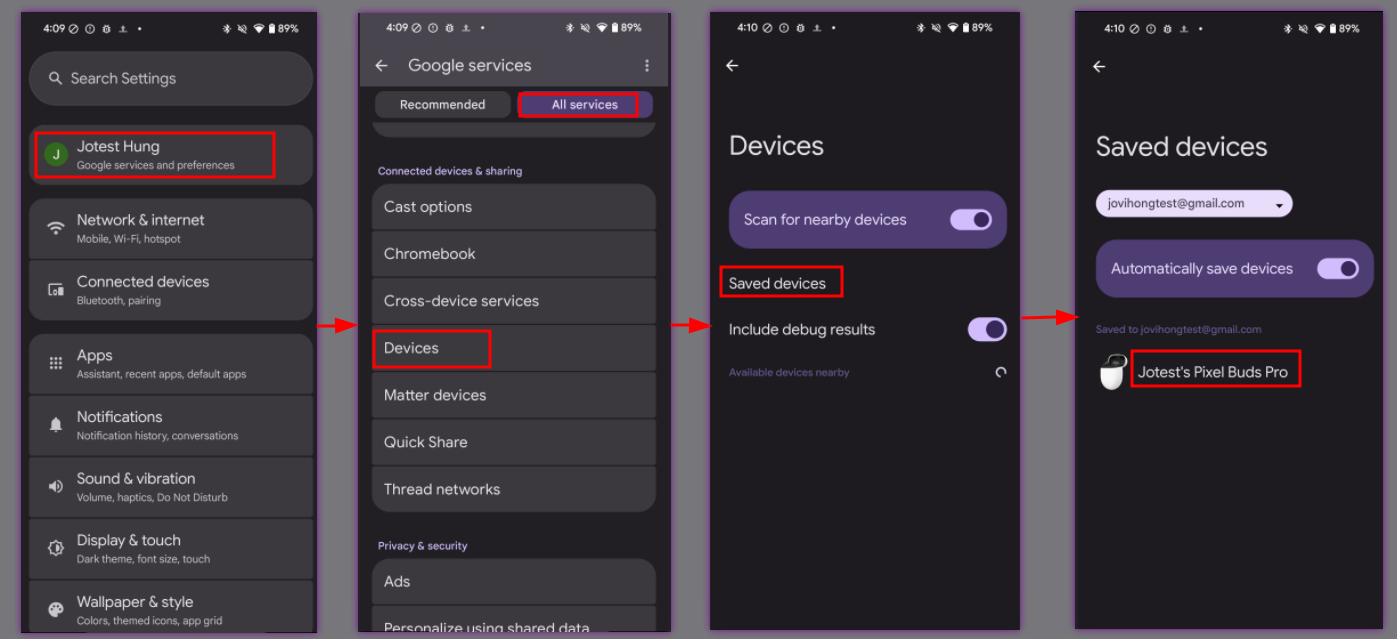

Google's own devices including their Pixel Buds Pro are vulnerable, which is particularly embarrassing for Google given that they designed the Fast Pair protocol.

The researchers note that these aren't exhaustive lists. There are likely other models not specifically tested that have similar vulnerabilities.

A crucial question: do you own any of these? Check your drawer. Check your car. Check your office. Check what your friends are using. This vulnerability is widespread enough that there's a strong chance you or someone close to you is affected.

Estimated data shows that identity verification flaws are the most common vulnerability in WhisperPair attacks, followed by timing issues and cryptographic verification flaws.

Why Patches Are Complicated

You might be thinking: okay, so there's a vulnerability. Companies release patches. Problem solved. Right?

Wrong. And understanding why reveals a fundamental problem with IoT security.

Here's the issue: audio accessories aren't like smartphones or computers. They don't have automatic update mechanisms built in. Your headphones aren't going to wake up at 3 AM and download a security patch like your iPhone does.

Instead, patches for these devices typically require one of two approaches. Either the manufacturer releases an app you need to install on your phone or computer, connect your device to, and manually apply the patch. Or, in some cases, patches come through the audio accessory's proprietary app if it has one.

Let's walk through how this actually works for a Sony device. You'd need to:

- Know a patch exists (most people won't)

- Find Sony's support website

- Locate the specific model of your headphones

- Download the right patch file

- Install Sony's proprietary software or app

- Connect your headphones to the computer or phone running that app

- Follow the patch installation process

- Wait for it to complete

Compare this to updating your phone's security: you get a notification, you tap "update now," and it happens in the background.

For audio accessories, every step is manual. And here's the brutal truth that researchers and security experts will tell you: the average person completes maybe one of those steps and then gives up.

Sony, Xiaomi, JBL, and others have released patches. Some are available now. Others are coming "over the next few weeks" according to their statements. But the people who most need these patches (people who don't closely follow tech security news) won't hear about them. They won't know to look for them.

Researchers estimate it could take months or even years for most vulnerable devices to get patched in the wild, not because the patches don't exist, but because distribution and user adoption are genuinely difficult problems.

How Attackers Find Targets

This is where the threat model becomes concrete. You might assume that exploiting this vulnerability requires sophisticated attackers with special skills. But that's not quite right.

The attack itself isn't particularly technically demanding. Someone with moderate Bluetooth programming knowledge could build tools to automate it. The KU Leuven researchers have demonstrated it working. Once a proof-of-concept exists, it tends to get shared and refined in security communities.

Who would actually target someone this way? Let's think through realistic threat scenarios.

The Jealous Partner or Stalker: This is actually a plausible threat. Someone who wants to monitor their partner or another person could target them. They wouldn't need advanced skills. They'd need to know the person owns a vulnerable device (which is easy since these models are popular) and have a way to get within 50 feet of that person regularly. The fact that it provides real-time location tracking makes this especially concerning for abuse victims.

The Jealous Coworker: Someone in your office who wants to spy on you could set up a Bluetooth-enabled computer in a shared space. Over time, they could harvest audio of your conversations or track when you arrive and leave.

The Burglary Ring: Criminals could scan neighborhoods for specific high-value audio devices. Once they identify targets (the expensive Sony speakers, Marshall speakers), they could monitor location and activity patterns to find good times for burglaries.

Nation-State or Corporate Espionage: While less likely to target regular individuals, the capability would be useful for intelligence agencies or corporate competitors wanting to monitor specific people of interest.

The Curious Attacker: Someone who can build the tools might exploit the vulnerability just to prove they can, without any specific target in mind. This is how many vulnerabilities get exploited initially: someone figures it out and starts testing it on people around them.

The 50-foot range is important context. That's roughly the range of a typical large house, a small apartment building, a coffee shop, a train car, or an open office. An attacker doesn't need specialized positioning. They need to be in a location where the target is going to be.

The chart illustrates the complexity of applying security patches on audio accessories compared to smartphones. Audio accessories show significantly lower completion rates across all steps due to manual processes.

The Google Response: Patches and Problems

When the KU Leuven researchers first discovered the vulnerability in August, they responsibly disclosed it to Google before going public. This is the standard process in security research: give the company time to fix it before revealing the vulnerability to the world.

Google's response was relatively quick. They published a security advisory acknowledging the Whisper Pair findings. They worked with manufacturers to push patches. They released updates to their own Pixel Buds Pro and other Google-branded audio devices.

They also released a patch to Android that they claimed would prevent the Find Hub tracking issue. This was important because it suggested Google understood the severity of location tracking and was taking it seriously.

But here's where things got complicated. Almost immediately after Google released its patch, the researchers found a bypass. They could still conduct the Find Hub tracking attack even with the patch in place. They informed Google of this, but as of the original reporting, Google hadn't issued an updated fix.

This is actually pretty common in security research. The first patch attempt doesn't always fully solve the problem. It might address the obvious exploitation vector but miss a subtle variation. Finding and fixing these bypasses takes additional development and testing time.

Google's statement to the press said they had "not seen evidence of any exploitation outside of this report's lab setting." This is probably true, but it's also important context: Google would have difficulty observing attacks on non-Google devices. If someone hijacks a Sony headset, Google's own systems might never see evidence of it.

For their own devices, Google likely does have the telemetry to know if their Pixel Buds are being hijacked in weird ways. But for JBL, Sony, and others, there's no centralized visibility. The fact that Google hasn't seen exploitation in their own systems is somewhat reassuring but doesn't mean the vulnerability hasn't been exploited elsewhere.

The Manufacturer Response: Mixed Results

When Google alerted the manufacturers to the vulnerability in August, the responses varied significantly.

Sony: As one of the companies with the most models affected, Sony has been relatively quiet publicly but apparently has been working on patches in the background. They didn't initially respond to press inquiries but are presumably developing fixes.

JBL: They issued a statement that Google had informed them of vulnerabilities and that they'd received security patches from Google. They said they'd roll out updates through their app over several weeks. This is responsible communication, though the slow rollout timeline is concerning.

Xiaomi: They confirmed they're working with suppliers to push over-the-air updates to their Redmi earbuds. This is actually the best-case scenario because OTA updates happen automatically without user intervention.

Jabra: They claimed they pushed out patches in June and July, but the timeline doesn't match when the researchers did their work. This suggests Jabra might have been patching for different Bluetooth vulnerabilities, not Whisper Pair. This kind of confusion isn't helpful for users trying to figure out if they're protected.

Logitech: They said they've "integrated a firmware patch for upcoming production units," which basically means new devices will have the fix, but existing devices in the wild won't unless the company releases a separate patch for them. Logitech also noted their affected Wonderboom 4 speaker doesn't have a microphone, which limits the eavesdropping risk for that specific device.

One Plus, Marshall, Nothing, and Soundcore: These companies either didn't respond or gave minimal responses. For consumers who own their devices, this is frustrating. You don't even know if a patch is coming or what timeline to expect.

The fragmented response is actually a feature, not a bug, of how the Android ecosystem works. Each manufacturer controls their own hardware and software. There's no central authority forcing everyone to release patches on the same timeline. This gives flexibility but also makes security patchwork and inconsistent.

Xiaomi leads with the most effective response due to automatic OTA updates. JBL follows with a clear communication plan, while others lag behind. Estimated data based on available information.

Location Tracking: The Scariest Part

Out of all the aspects of the Whisper Pair vulnerability, the location tracking capability is probably the most alarming. And it deserves its own deep dive.

Google's Find Hub feature (available on certain Bluetooth devices and available through Android) lets you locate your lost devices on a map, similar to how Apple's Find My works. If you've ever lost your earbuds, you know how useful this can be. You open your phone, see a map, and your device appears as a marker. You can navigate to it.

For this to work, the devices need to broadcast their location somehow. There are multiple technologies that enable this. The most common approaches are:

-

Bluetooth Low Energy scanning: Android devices and iOS devices create a mesh network where they can report back the Bluetooth signals they see. If your lost device broadcasts a BLE signal, nearby phones report it, and the system triangulates the location.

-

GPS in the device: If the audio device itself has GPS (rare for earbuds and headphones, but possible for some speakers), it can report its location directly.

-

Cellular integration: Some devices have cellular connectivity that allows them to report their location through carrier networks.

The vulnerability in Find Hub allows an attacker who has hijacked a device to access its location information and track it in real-time. For a stalker or abuser, this is genuinely dangerous. They know where you are at all times. They know your patterns. They know where you live, where you work, and where you spend your evenings.

What makes it particularly insidious is that it works silently. You're not getting any notification that your device is being tracked. There's no indicator. No battery drain alert. Nothing. The attacker is just quietly querying the location information and building a profile of your movements.

And again, the ironic part: this can happen to iPhone users even though they don't use Google services. If they borrow a friend's Bluetooth speaker that has Find Hub integration, that speaker could be hijacked and used to track them.

Practical Protection Steps You Can Take

Okay, this has been pretty heavy information. Let's talk about what you can actually do right now to reduce your risk.

Step 1: Identify Your Devices

First, make a list of what you actually own. Every Bluetooth audio device. Check your home, your car, your office, your bag. Write down the brand and model of each device. Be thorough. That old JBL speaker you forgot about in the closet still has this vulnerability.

Step 2: Check for Patches

Go to the manufacturer's support website for each device. Look for firmware updates or security patches. The page layout varies by manufacturer, but you're looking for something like "Support," "Downloads," "Firmware Updates," or "Software Updates."

If a patch is available, follow the instructions. Yes, it's tedious. Yes, you have to install an app you don't want. Do it anyway. Seriously.

Step 3: Decide What Stays and What Goes

For devices where no patch is available and no timeline has been announced, you have choices:

- Keep using them and accept the risk

- Stop using them until patches are released

- Sell them or donate them

- Request a refund from the retailer

There's no universally right answer. It depends on how much you value these devices and how much risk you're comfortable with.

Step 4: Manage Bluetooth Exposure

In situations where you're in public or around people you don't fully trust, you have some options to reduce attack surface:

- Turn off Bluetooth on your phone when you're not actively using it

- Put your phone in airplane mode in crowded places

- Disable Fast Pair notification if your phone allows it

- Use wired headphones instead of wireless ones when possible

These aren't perfect solutions, but they reduce the window of opportunity for an attacker.

Step 5: Stay Informed

Follow security news sources that cover IoT and Bluetooth vulnerabilities. This vulnerability has been disclosed, but there will be others. The more you know, the faster you can respond.

Bluetooth Low Energy is the most common technology used for location tracking, accounting for 50% of usage. Estimated data.

The Bigger Picture: Why IoT Security Keeps Failing

This vulnerability is important, but it's also a symptom of a larger problem with how the industry approaches Internet of Things (IoT) security.

The fundamental issue is incentives. Manufacturers have a strong incentive to get devices to market quickly and at low cost. Bluetooth audio accessories are commoditized. There's intense price competition. The devices that sell are the ones that are affordable and convenient.

Building in robust security from the beginning costs money. Testing security thoroughly costs money. Creating automatic update infrastructure costs money. Setting up secure supply chains costs money.

A company making

When a vulnerability is discovered later, manufacturers face a choice: invest resources in fixing it, or leave it alone and hope nobody exploits it. If they're a smaller company or if the cost of fixing is high, they often choose the latter.

Google's role here is interesting. They set the Fast Pair standard. They could have built in stronger requirements for how manufacturers implement it. They could have made it harder to get it wrong. But that would have made adoption slower. Manufacturers prefer simpler specs.

The result is that we have hundreds of millions of devices with a known vulnerability that will probably never get patched because the patch mechanism is broken. Not broken technically—it's not like patches don't exist. But broken in terms of how users actually behave. The gap between a patch being available and most users getting it is measured in months or years or infinity.

Some of this is changing. EU regulations increasingly require manufacturers to provide security updates for a minimum period. India has started implementing IoT security standards. Slowly, the industry is being forced to take this more seriously.

But for this specific vulnerability affecting these specific devices? The practical security window is narrow. If you own a vulnerable device and you want to be protected, you need to act in the next few weeks while patches are still fresh and support teams are still thinking about this issue.

Future Fixes and Better Standards

Looking forward, there are a few ways this category of vulnerability could be prevented in future devices and protocols.

Mandatory Encryption for All Pairing State Machines: The core issue across many of the vulnerable devices was that certain parts of the pairing process weren't sufficiently encrypted. Future implementations should require encryption from the very first handshake message, with no exceptions.

Hardware-Backed Security Modules: Newer Bluetooth chipsets increasingly include dedicated security processors. If pairing validation happens in these protected environments, it's harder for attackers to compromise it.

Automatic Rollback Protection: Some attacks work by replaying old pairing messages or device firmware. Implementing strong rollback protection (ensuring devices check version numbers and timestamps) would prevent this class of attack.

Decentralized Security Updates: Instead of relying on users to manually download and apply patches, manufacturers could use cloud-based security architecture where updates happen automatically through the device's normal connectivity.

Open Source Implementation Requirements: If Bluetooth implementations were open source (or at least auditable), security researchers could identify flaws earlier. Closed, proprietary implementations are vulnerable to the "security through obscurity" problem.

Google has already learned lessons from this. Their internal processes for how they'll implement Bluetooth security in future products have presumably been updated. But the installed base—those hundreds of millions of vulnerable devices—they won't benefit from these improvements.

One small positive note: the researchers' work has been published and detailed. Security researchers at other companies can now use their findings to audit other products. Companies that haven't been tested yet might proactively fix similar issues in their own devices. That's not guaranteed, but it's possible.

Industry Accountability and What Needs to Change

Beyond the technical fixes, there's a governance problem. When vulnerabilities affect this many devices, who's responsible for fixing them? The current model basically says: the manufacturer is responsible, but there's no enforcement mechanism.

The EU's Cyber Security Act will require manufacturers to disclose vulnerabilities within specified timeframes and provide security updates for products sold after a certain date. This is movement in the right direction. But it doesn't help the existing products that were sold before these regulations took effect.

Some experts argue for "right to repair" laws that would require manufacturers to keep support for longer periods. Others suggest a "security fund" where manufacturers contribute to a fund used to patch legacy devices they can no longer afford to support.

What's clear is that the current model of "ship it, ignore security issues, let the market sort it out" isn't working when security issues can enable surveillance and stalking.

Companies like Sony and JBL need to understand that putting out a patch on their website and hoping people find it isn't sufficient. They should be proactively notifying users. They should be using every communication channel available. Email if they have it. In-app notifications. Push notifications through any companion app. SMS if applicable.

Google, having created the Fast Pair protocol, also bears some responsibility for better documentation, better implementation guides, and better enforcement of security standards among manufacturers who use the spec.

This has been a long, technical article. Here's what matters: if you own any of the affected audio devices, there's a real, documented vulnerability that could enable someone to spy on you or track your location. Patches exist for some devices. Others are coming. The longer you wait, the more likely an attacker has time to compromise your device. Check your devices. Find patches. Apply them.

That's the most important actionable advice from all of this.

FAQ

What exactly is the Whisper Pair vulnerability?

Whisper Pair is a collection of security flaws discovered in 17 Bluetooth audio devices from 10 different manufacturers. These flaws allow an attacker within 50 feet to silently pair with the device without authorization, then take control of the microphone, speaker, and location tracking features. The vulnerability exploits weaknesses in how manufacturers implemented Google's Fast Pair protocol.

How many devices are actually vulnerable to Whisper Pair?

Researchers estimate over 300 million audio devices are vulnerable, including popular models from Sony, JBL, Marshall, Xiaomi, Nothing, One Plus, Soundcore, Logitech, Jabra, and Google. The 17 specific models tested by KU Leuven University represent a sample of the broader vulnerable population, but the implementation flaws are widespread across manufacturers.

Can an attacker hijack my device without being physically nearby?

No. The attack requires the attacker to be within Bluetooth range, which is approximately 50 feet in open space. However, this isn't a particularly restrictive requirement. A coffee shop, office building, apartment complex, or commuter train all fall within this range. The attacker doesn't need to be obviously positioned near you; they just need to be in the same general area.

Will my device automatically update with security patches?

Unfortunately, most audio accessories don't have automatic update mechanisms like smartphones do. Patches typically require you to download the manufacturer's app, connect your device, and manually apply the update. This manual process is why researchers estimate it could take months or years for most devices to be patched in the wild, even though patches exist.

Is location tracking only possible on Google devices?

No. The researchers specifically demonstrated location tracking on both Google devices and Sony devices that support Find Hub. Notably, even iPhone users could be tracked through this vulnerability if they own or are near a compromised device with location tracking capability. The vulnerability works across both Android and iOS ecosystems.

What should I do if I own one of the vulnerable devices?

First, check your device manufacturer's website for available firmware updates or security patches. Follow their instructions to apply any available patches. If no patch is available, check back regularly as manufacturers continue to release fixes over the coming weeks. In the meantime, consider turning off Bluetooth when not in use or disabling Fast Pair notifications if possible on your phone.

Did Google know about this vulnerability when they designed Fast Pair?

No. Google designed Fast Pair with security in mind, but the vulnerabilities exist in how individual manufacturers implemented the protocol on their specific devices. The flaws aren't in the Fast Pair standard itself, but in manufacturer shortcomings like incomplete validation of pairing requests, missing encryption in certain handshake phases, or lack of rate limiting on connection attempts.

Has anyone been exploited by this vulnerability outside of research?

Google stated they had not seen evidence of exploitation outside of the researchers' lab setting. However, this doesn't mean it hasn't happened. Google would have visibility into attacks on Google devices but would have no way to observe attacks on Sony, JBL, or other manufacturers' devices. The vulnerability has been publicly disclosed now, which increases the risk of exploitation going forward.

Will my homeowner's or renter's insurance cover losses from this vulnerability?

This is unlikely. Standard homeowner's and renter's insurance typically doesn't cover cybersecurity incidents or losses from device hijacking. If you're concerned about stalking or harassment, that's a matter for law enforcement. If you're worried about privacy, focus on installing patches and managing your Bluetooth exposure.

What's the difference between this vulnerability and typical Bluetooth hacking?

Typical Bluetooth hacking usually requires some level of user interaction or special hardware. This vulnerability is different because it exploits a fundamental flaw in the pairing process. An attacker can compromise a device silently, within 50 feet, without any notification to the user, and without the device owner doing anything wrong. It turns a security feature (Fast Pair) into an attack vector.

Protecting Your Digital Life: Related Security Practices

Beyond this specific vulnerability, there are broader security practices that protect your audio devices and digital life.

Regular Security Audits: Once every few months, review the devices you own and their security status. Which ones have outdated firmware? Which ones are no longer receiving support? This simple practice catches problems early.

Vendor Accountability: When you purchase devices, factor in the manufacturer's track record on security. Companies that have been responsive to past vulnerabilities are more likely to respond well in the future. Conversely, manufacturers with poor security track records should be avoided.

Network Segmentation: If you have a home network, consider putting IoT devices on a separate network from your computers and phones. This limits what an attacker can do if one device is compromised.

Bluetooth Profile Awareness: Understanding which Bluetooth profiles your devices use matters. A simple speaker that only plays audio has a smaller attack surface than a device with microphone access. When shopping for devices, consider this.

The Whisper Pair vulnerability has gotten attention because it affects so many devices and enables serious harms like stalking and surveillance. But it's part of a broader pattern where IoT devices ship with security problems that never get fixed. Being aware of this pattern helps you make better purchasing and device management decisions.

Final Thoughts: Living With Imperfect Security

Here's the uncomfortable truth about technology security: nothing is perfectly secure. There will always be vulnerabilities. The question isn't whether flaws exist, but whether they get fixed quickly and whether you're informed enough to take action.

In this case, researchers did the right thing. They discovered a serious vulnerability affecting hundreds of millions of devices. They responsibly disclosed it to Google and manufacturers. They published detailed findings so the industry could learn. Most of the companies involved have started rolling out patches.

But the patch distribution system is broken. It relies on users knowing to check for updates, finding the right app or website, and manually applying fixes. In practice, this means most vulnerable devices will stay vulnerable for a long time.

What you can do:

Check your devices now. If you own a Sony headset, JBL speaker, Marshall product, or any of the others mentioned, spend 15 minutes checking for patches. That's probably the most impactful security action you can take this month.

Stay informed. Follow security news outlets that cover privacy and device security. The more you know, the faster you can respond when the next vulnerability is disclosed.

Choose manufacturers that care about security. When buying new devices, factor in the manufacturer's security track record. Vote with your wallet.

This isn't about creating paranoia or assuming everyone's trying to hack you. Most people aren't. But the capability exists now. The vulnerability is documented. Patches are available. For the few people who might want to exploit this—whether they're stalkers, criminals, or nation-states—the opportunity is real.

Taking basic protective steps is just smart technology hygiene. No different than changing your passwords or turning off location sharing when you don't need it.

Your headphones shouldn't be a vulnerability. But right now, for millions of people, they are. Do something about it.

Key Takeaways

- Over 300 million audio devices from 10 major manufacturers contain WhisperPair vulnerabilities in Google's Fast Pair protocol

- Attackers within 50 feet can silently hijack devices, activate microphones for eavesdropping, inject audio, and track locations in real-time

- Security patches exist but require manual installation through manufacturer apps, leaving most vulnerable devices unpatched for months or years

- Location tracking works even on iPhones through compromised devices with Find Hub integration, enabling serious stalking threats

- Immediate action needed: check manufacturer websites for firmware updates to your Sony, JBL, Marshall, Xiaomi, and other vulnerable devices

Related Articles

- VoidLink: The Advanced Linux Malware Reshaping Cloud Security [2025]

- DDoS Attacks in 2025: How Threats Scale Faster Than Defenses [2025]

- How to Change Your Location With a VPN: Complete Guide [2025]

- Porn Taxes & Age Verification Laws: The Constitutional Battle [2025]

- Craigslist: Why Millennials Still Choose Authenticity Over Algorithms [2025]

- Ring's Mobile Security Trailer: 360-Degree Coverage Anywhere [2025]

![Fast Pair Bluetooth Vulnerability: Why 300M Devices Need Patching [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/fast-pair-bluetooth-vulnerability-why-300m-devices-need-patc/image-1-1768480806980.jpg)