FBI Device Seizure From Washington Post Reporter: Journalist Rights and First Amendment [2025]

A federal judge just hit the brakes on something that should terrify every journalist in America. The FBI seized devices from Hannah Natanson, a Washington Post reporter, and was about to search through her entire professional life. Years of source information. Confidential communications. Story drafts. Medical records. Wedding planning details. Everything.

Then a judge said, "Not so fast."

But this temporary win masks a much deeper problem. The government's ability to seize a journalist's devices in the first place. The chilling effect on reporting. The erosion of source protection that's foundational to investigative journalism. This isn't just about one reporter. It's about whether journalism as we know it can survive in an era of aggressive government surveillance and broad search warrants.

Let me walk you through what happened, why it matters, and what comes next.

The Seizure: What Actually Happened

Here's how this unfolded. The FBI executed a search warrant at Hannah Natanson's home in January 2026. They weren't investigating her. She wasn't accused of any crime. She's a reporter doing her job.

But they were investigating Aurelio Perez-Lugones, a Pentagon contractor with a top-secret security clearance. He allegedly took classified intelligence reports home. Maybe leaked them. The government suspected Natanson had received documents from him.

So they got a warrant. And they took everything.

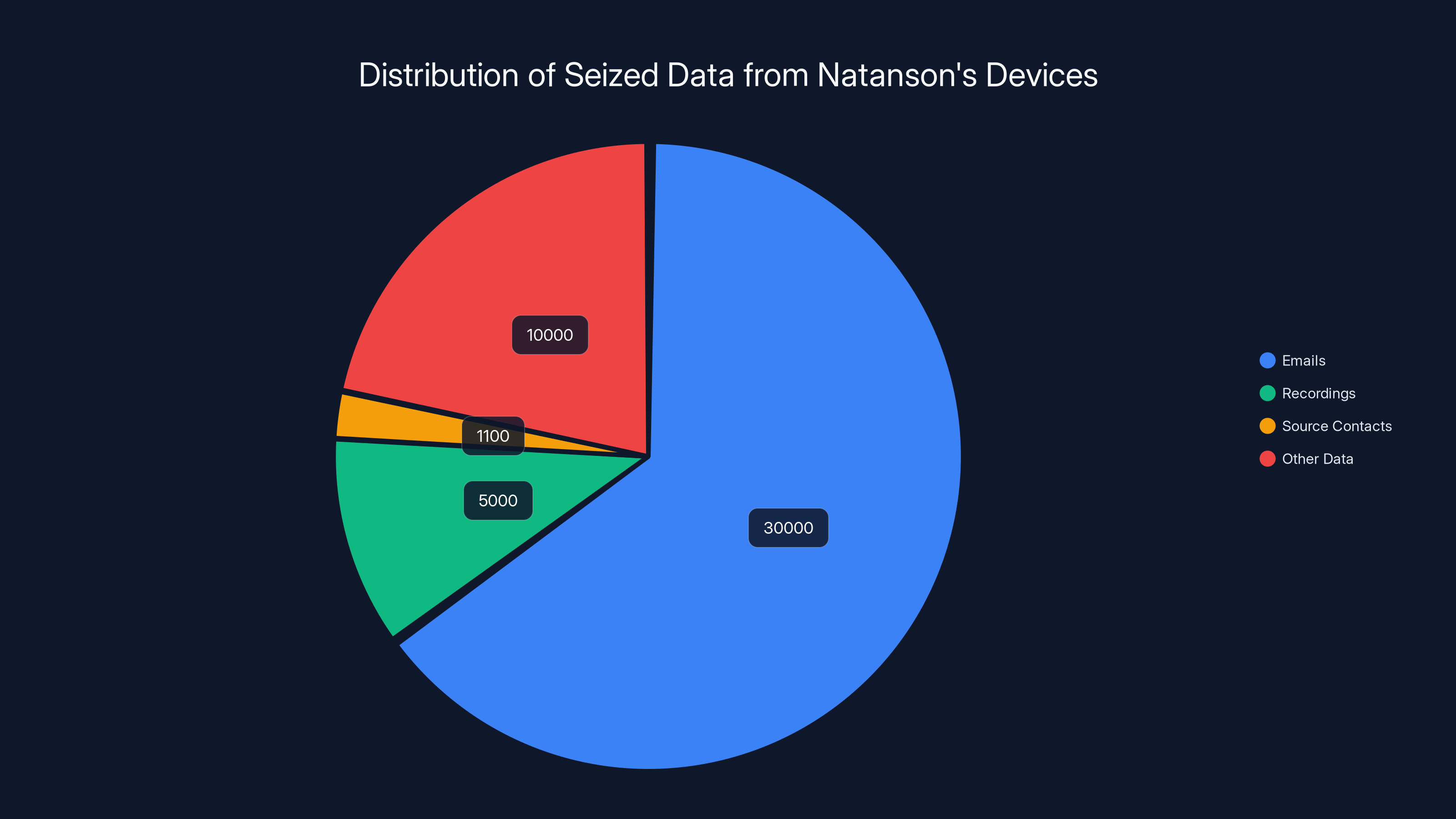

This wasn't a targeted grab of a few files. This was confiscation of her entire professional universe. Over 30,000 emails from the past year alone. Recordings of interviews. Notes on unreported stories. Communications with more than 1,100 confidential sources. Her encrypted Signal chats where she maintains those source relationships.

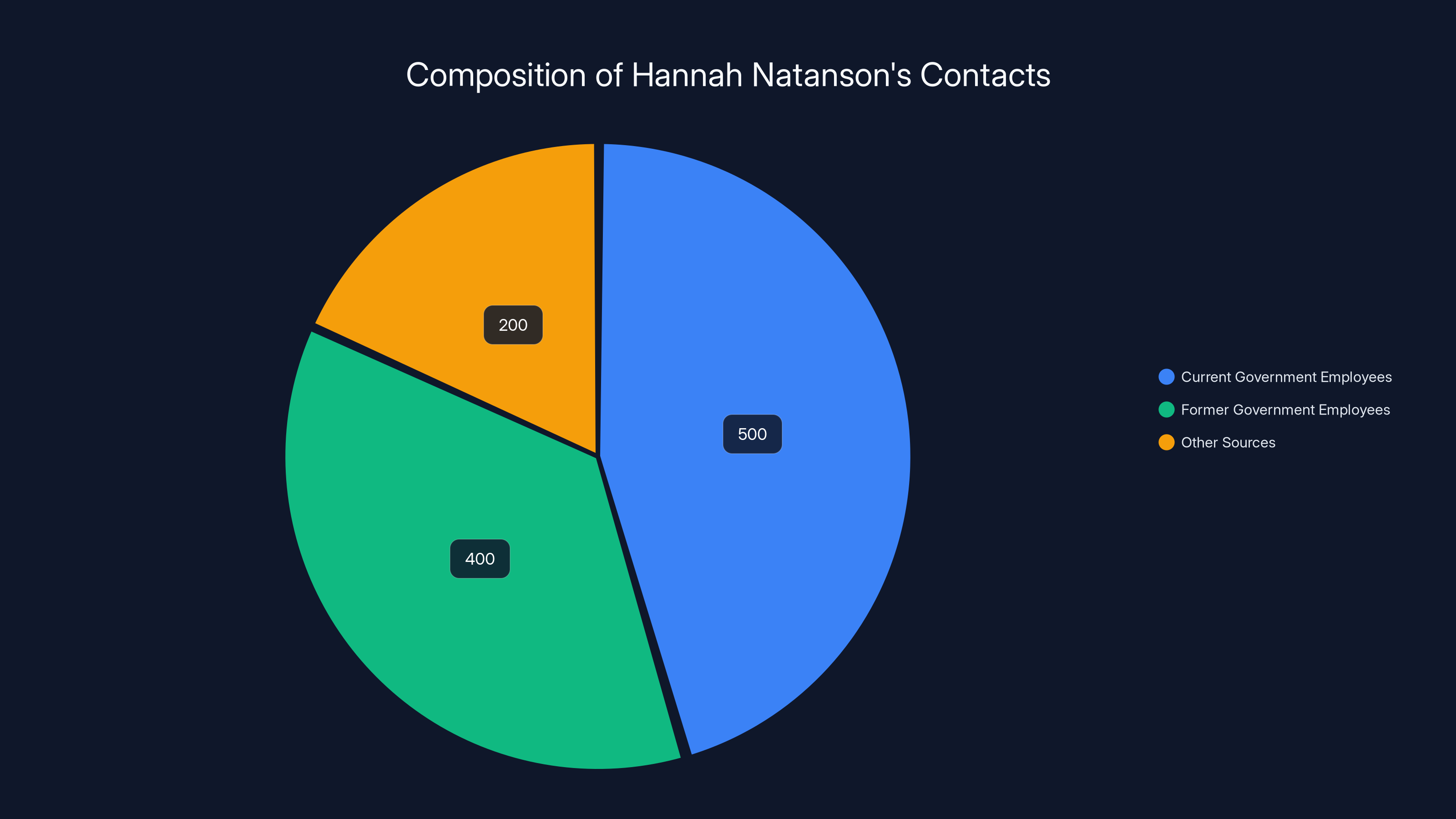

Think about that number: 1,100 sources. That's not just reporting contacts. That's Natanson's entire professional network of government employees, whistleblowers, and insiders who trusted her to protect their identities. Without her devices, she literally cannot contact them. Some of those sources might now assume their cover was blown.

The devices also contained deeply personal information. Medical records. Tax documents. Details about her wedding. The government argued they needed all of this to find documents that Perez-Lugones might have provided.

The majority of the seized data consists of emails, with a significant portion also being recordings and source contacts. Estimated data based on content description.

The Core Legal Problem: Overly Broad Search Warrants

Here's where the real issue emerges. Warrant law is broken for journalists.

When police want to search your house, they need probable cause to believe evidence of a crime is there. That's the Fourth Amendment. But there's a massive gap between "probable cause that evidence exists" and "we can search literally everything you own."

For regular suspects, there's been some movement toward narrow warrants. Police are supposed to describe specifically what they're looking for. Not "evidence of any crime." But "documents matching X, Y, Z." The goal is proportionality.

For journalists, warrants get treated differently. And not in a good way.

The government wanted documents received from or relating to Perez-Lugones. That's a reasonable search target. But the government executed that warrant by seizing six devices containing millions of files spanning years. They took Natanson's entire device storage instead of asking for specific records.

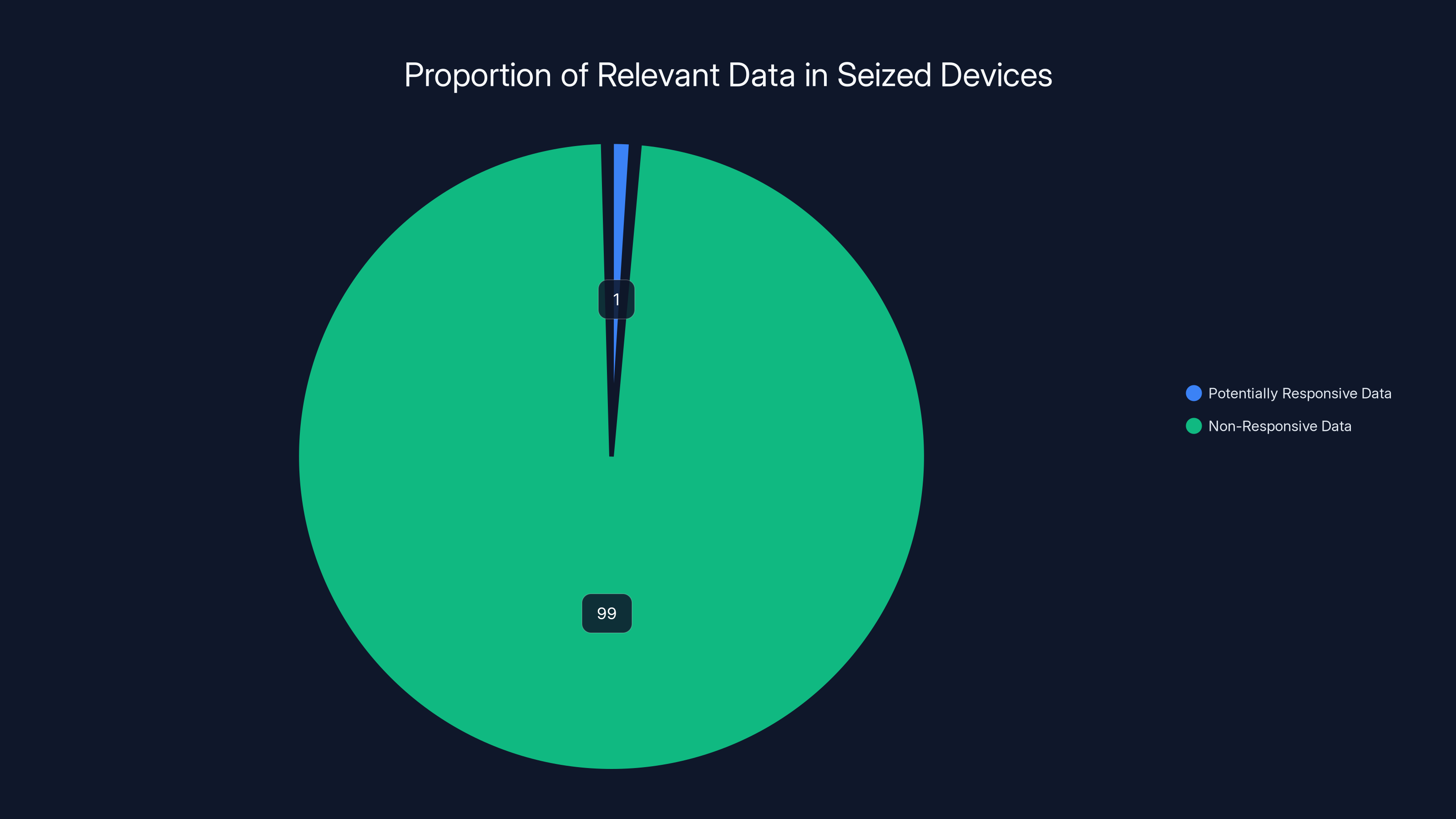

The Post's argument is mathematically simple. Natanson has thousands of source communications across 1,100+ contacts. Perez-Lugones allegedly possessed only a small number of classified documents and only began collecting them three months prior. The overlap? Probably tiny. Maybe less than 1% of seized data is even potentially responsive.

So the government seized a haystack to find a needle. And in doing so, they grabbed everything else: First Amendment protected material, attorney-client privileged communications with legal counsel, privileged psychotherapist notes, and medical information protected under federal privacy law.

Judge Porter's Temporary Victory: The Standstill Order

US Magistrate Judge William Porter looked at this situation and said the government needs to pause.

His order was surgical and precise. The government must preserve the seized materials. But they cannot review them. Not yet. Not until the court decides whether the search was even legal.

Porter granted what's called a "standstill order." It's a temporary freeze. The ruling stated: "The government must preserve but must not review any of the materials that law enforcement seized pursuant to search warrants the Court issued... until the Court authorizes review of the materials by further order."

This matters because the government had already told the Post's lawyers: "We're going to start searching these devices. Thanks for the warning, but we're not waiting." That's aggressive. That's what "the government refused" to listen to concerns about protected material.

Porter's order puts that search on hold while the court schedules full briefing and oral arguments.

But here's the crucial detail: this isn't a win. It's a pause. A temporary reprieve. The fundamental problem remains.

Estimated data shows that Hannah Natanson's contact list primarily consists of current and former government employees, essential for her investigative journalism.

The First Amendment Problem: Prior Restraint

The Washington Post framed this as a First Amendment issue. Specifically, they called it "prior restraint."

Prior restraint is government action that blocks speech before it happens. Not punishment after you publish. Blocking before you can publish. It's one of the most serious First Amendment violations because it stops information from reaching the public entirely.

The Post's argument: by seizing Natanson's devices, the government has suppressed her ability to publish. She can't contact her sources. She can't access her draft stories. She can't work. That's prior restraint in action.

The government probably disagrees with that framing. They'd argue they're not stopping publication. They're just investigating a potential crime. The seizure of devices is investigative action, not censorship.

But that argument ignores practical reality. When you seize a journalist's devices, you functionally stop their work. Especially when you seize everything instead of specific files. Natanson can't do her job without her devices. The ability to be a journalist has been restrained.

The Supreme Court has been skeptical of government efforts to burden press freedom. The landmark case is New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), where the Court blocked the Nixon administration from restraining publication of the Pentagon Papers. The Court held that prior restraint carries a "heavy presumption against constitutional validity."

Does seizing a journalist's devices trigger that same level of scrutiny? That's what the court will have to decide.

Source Protection: The Backbone of Investigative Journalism

Here's what most people don't understand about investigative journalism: it doesn't work without sources.

A journalist's contacts are her most valuable professional asset. That list of 1,100 sources Natanson maintains? That's years of relationship building. Trust earned. Confidentiality promises made. Those sources took risks to talk to her. They shared information that could get them fired, prosecuted, or worse.

When the government seizes a journalist's devices, they gain access to those source lists. They see encrypted chats. They see which government employees were communicating with a reporter. They can identify whistleblowers and confidential sources.

This has a cascade effect. Current sources realize their cover might be blown. Future sources won't contact journalists because they assume government surveillance is likely. Whistleblowers stay silent. Misconduct stays hidden. The public loses oversight of their own government.

The Supreme Court has never formally recognized an absolute journalist-source privilege in federal law. That's a massive gap. Most professions have privilege: lawyers with clients, doctors with patients, clergy with penitents. Journalists don't have the same protection federally.

Some states recognize a journalist shield law. Some don't. Federal courts are split on how much protection journalists get. But seizing all of a journalist's devices is unusually aggressive even by current standards.

The Underlying Case: What Was the Government Actually Looking For?

To understand why this matters, you need to know the original investigation.

The government was investigating Aurelio Perez-Lugones. He was a system administrator at the Pentagon with a top-secret security clearance. The government alleges he took classified intelligence reports home. Maybe provided them to unauthorized people. Maybe leaked them to the press.

That's serious. If true, if he actually took classified information home and leaked it, that's a crime. And there's legitimate government interest in investigating it.

But here's the thing: the government's own criminal complaint admits that Perez-Lugones possessed only a limited number of potentially classified documents. And he only started collecting them three months prior to the investigation.

So the government's own paperwork shows the universe of responsive documents is small. The time window is narrow. The number of people with access is limited.

Yet the government seized Natanson's devices going back years. Multiple devices. Millions of files. A broad dragnet approach instead of a targeted investigation.

The Post argued that instead of seizing everything, the government could simply subpoena the Post directly. Or subpoena Natanson. Ask for communications with Perez-Lugones specifically. Get documents he allegedly sent her. That's the traditional approach.

A subpoena would give the government the same information but with built-in safeguards. Natanson could contest it. The Post could assert privilege over confidential materials. The court could limit the scope. You can't do any of that with a surprise search warrant that seizes everything.

Estimated data suggests that less than 1% of the seized data was potentially responsive to the warrant, highlighting the issue of overly broad search warrants.

Attorney-Client Privilege: The Complicating Factor

There's another layer here that makes this even worse: attorney-client privilege.

Natanson contacted the Washington Post's legal team immediately after the FBI search. Lawyers have been advising her and the Post on how to respond. Those communications are legally privileged. The government can't read them. Can't use them. Can't even know what advice was given.

But if the devices remain in government custody and the government searches them, privilege gets complicated. The government might claim they need to search the devices to find criminal evidence. Privilege goes out the window in certain circumstances.

This creates a practical pressure: the government searches the devices, finds privileged communications, but claims they "accidentally" saw them during the search. The privilege is arguably waived. The defense gets murkier.

This is why the standstill order matters. By preventing the government from searching, the court protects attorney-client privilege while the broader legal questions get sorted out.

The Legal Standard: How Courts Actually Review Journalist Searches

Porter has a real legal framework to work with here, but it's not as strong as it should be.

Federal courts have developed a test for when government can search journalists' materials. The question isn't whether the government can investigate. It's whether the search was executed appropriately.

Courts ask: Did the government try less restrictive alternatives first? Did they use a subpoena instead of a warrant? Did they narrow the scope? Did they use filter teams to screen out privileged material? Did they follow published guidelines for journalist searches?

On all these points, the government seems to have failed. No subpoena attempt. No narrow scoping. No filter team. No apparent restraint.

Further, courts consider whether the search relates to a legitimate law enforcement purpose or whether it's actually trying to suppress speech. The government has a legitimate interest in investigating alleged leaks. But that doesn't mean they get a blank check to search everything a journalist owns.

Final factor: courts consider impact on journalism. Does the search chill free press function? Do sources lose confidentiality? Does the journalist lose ability to work? All yes here.

Porter will have to weigh these factors at the February 6 oral arguments.

Chilling Effect on Journalism: Why This Matters Beyond This One Case

Let's think about what happens if the government wins and can search Natanson's devices.

First, every journalist in America sees it. The FBI can seize your devices. Search through all your work. Look at your sources. Your conversations. Your draft stories.

Second, sources see it. Government employees who might leak misconduct? They see this and decide it's not worth the risk. Their name might appear in a search result. The government finds them. Retaliation happens.

Third, editors get nervous. Big investigations require risks. If those risks now include government device seizure, some stories just don't get reported.

This is the chilling effect. It's not direct censorship. It's the cold climate that prevents speech from happening in the first place.

The government claims this is just one case. One reporter. One investigation. But that's naïve. Every journalist operates under the precedent of the case before them. If Natanson loses, every other journalist knows they could be next.

The Press Freedom Foundation's statement captured this: "The search and seizure of Washington Post reporter Hannah Natanson's records is unconstitutional and illegal in its entirety. The Trump administration's policies require searches of journalists' materials to be narrow and targeted. This wasn't narrow. This wasn't targeted."

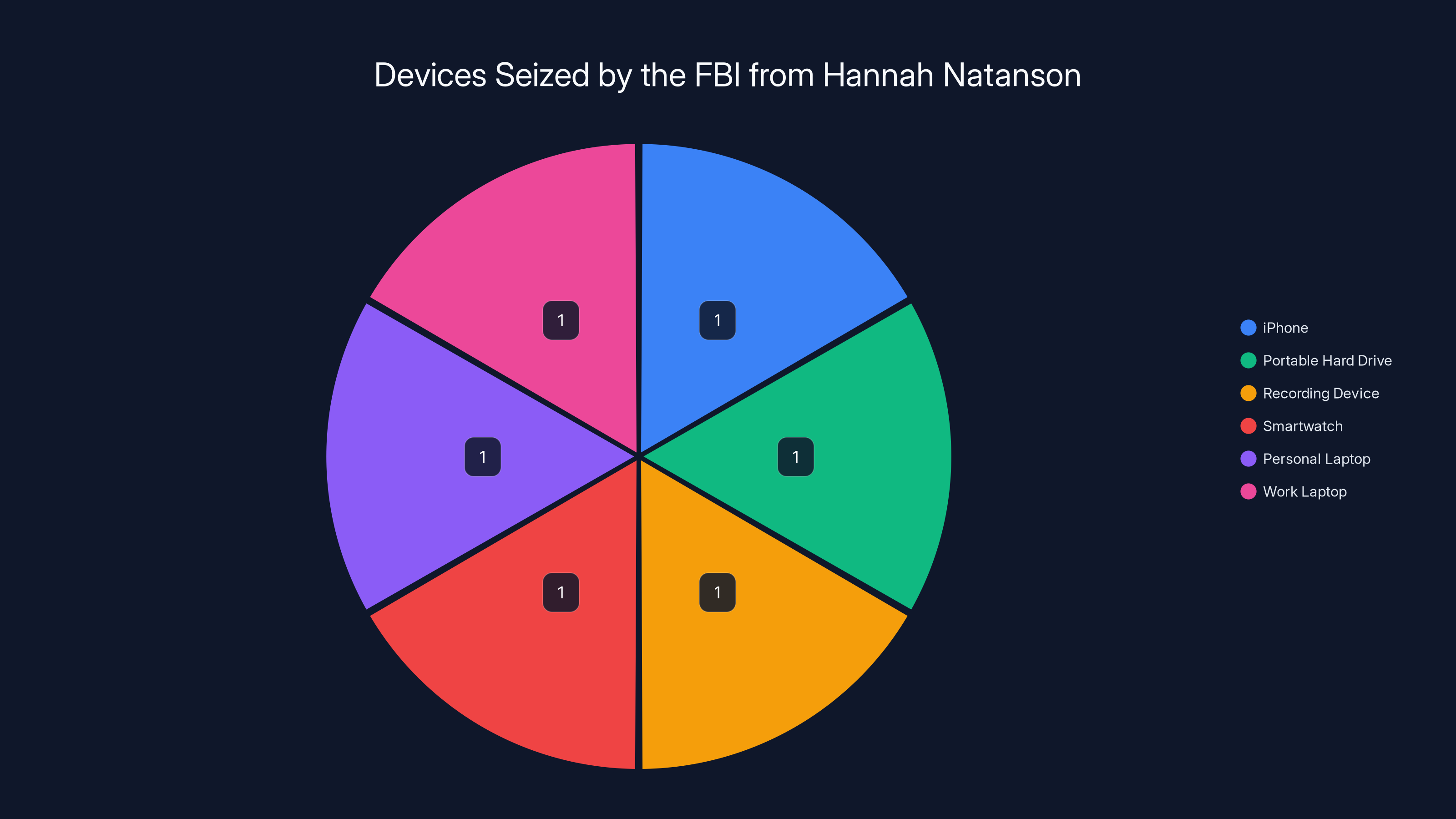

The FBI seized six distinct devices from Natanson, encompassing both personal and professional equipment, highlighting the extensive nature of the search.

Timeline and Next Steps: What Happens Now

Judge Porter established a clear schedule.

By January 28, the government must file a response brief explaining why they should be allowed to search the devices. They'll argue the investigation is legitimate. Perez-Lugones might have leaked documents. The warrant was properly issued. The search is reasonable.

The Post and Natanson will get time to file a reply. They'll argue the search is unconstitutional. It violates the First Amendment. It violates the Fourth Amendment. It violates privilege. It violates federal guidelines for journalist searches.

Oral arguments are scheduled for February 6. Both sides get to present in person. Answer questions. The judge gets to really dig into the legal issues.

After that? Another decision. Porter will rule on whether the standstill order becomes permanent. Whether the devices must be returned. Whether the government can search them going forward.

That's almost certainly not the end. Either side will appeal if they lose. This could end up in a circuit court. Maybe even higher.

Meanwhile, Natanson still can't do her job. Her devices remain seized. Her sources remain unreachable. This limbo continues for months or years.

Broader Context: Government Surveillance of Journalists

This case didn't happen in a vacuum.

The Trump administration has been more aggressive toward leakers and journalists than previous administrations. There have been more leak investigations. More pressure on news outlets. More government surveillance of people who report on the government.

The DOJ has been using broad surveillance authorities to investigate reporters' sources. Demanding phone records. Pursuing subpoenas. Executing search warrants.

This creates a difficult dynamic. Journalism requires secrecy about sources. Government leak investigations require finding sources. These are fundamentally opposed interests.

Previous administrations tried to balance this. They published guidelines. They said warrants on journalists should be narrow. They said subpoenas should be tried first. They said filter teams should screen material.

This case tests whether those guidelines actually mean anything. Or whether they're just suggestions the government can ignore when it wants to.

If the government searches Natanson's devices and faces no real consequence, the lesson is clear: guidelines don't matter. Warrants can be broad. Searches can be comprehensive. Journalists' materials are fair game.

If the court stops the search, it sends the opposite message: there are real limits to government power when it comes to the press.

The Perez-Lugones Angle: Why the Government Thought This Was Justified

Let's be fair to the government's perspective for a moment.

If Perez-Lugones actually did leak classified information, that's serious. National security is arguably at stake. The government has a legitimate interest in finding out what was leaked. Where it went. Who received it.

If they have reason to believe a journalist received classified documents from Perez-Lugones, they need to investigate. They can't just ignore it.

The question isn't whether they can investigate. It's how they investigate. With precision and restraint, or with sledgehammers and broad seizures.

The government chose sledgehammer. They got a warrant. They executed it broadly. They took everything.

Maybe they genuinely believed the narrow approach wouldn't work. Maybe they thought Natanson would destroy documents if warned. Maybe they thought she'd refuse a subpoena.

But those are speculations, not facts in the record. The government didn't attempt a subpoena. Didn't ask nicely. Didn't try anything less invasive first.

So from a judicial review perspective, Porter is right to question it. The government has burden to justify why they needed to be so broad.

Estimated data shows that government device seizures could significantly impact journalists (30%), sources (25%), editors (25%), and public trust (20%).

Federal Rules and Guidelines: What's Supposed to Happen

There are actual written rules about how journalists' materials should be handled.

The Department of Justice has guidelines, revised in 2020. They say:

- DOJ should use subpoenas to request journalist materials, not warrants, except in narrow circumstances

- Warrants on journalists should be narrow and specific

- Searches should use filter teams to screen out privileged material

- DOJ should follow procedures designed to protect confidential sources

- Department leadership must approve any search warrant on a journalist

Did the FBI follow these guidelines? The evidence suggests not.

No indication a subpoena was attempted. No indication a filter team was used. No indication the scope was narrowed. No sign the seizure was approved at the appropriate level.

This is why the Post kept saying "the government refused." When lawyers asked the government to follow its own guidelines, the government said basically: "We don't have to."

That's the real violation. Not just a broad warrant. But ignoring the very safeguards that are supposed to protect press freedom in leak investigations.

The Broader Implications: What Happens to Journalism?

This case touches something fundamental about how journalism works in democracies.

Investigative reporting requires access to people inside institutions. Government employees. Contractors. Whistleblowers. These people take massive risks to share information. They risk their careers. Their freedom. Sometimes their safety.

They only take those risks if they believe confidentiality is protected. If they think a journalist will keep their name secret. If they believe government won't find out who they are.

When the government seizes a journalist's devices, that protection vanishes. Suddenly, every source understands that the government can find out who they are. That their encrypted messages can be read. That their confidentiality depends entirely on the government's willingness to respect it.

That's a fundamental change to how journalism operates. It shifts the power dynamic. Institutions get stronger. Sources get riskier. Journalism gets weaker.

The press has always needed to operate with some level of government protection. Not because the press is special. But because democracy needs an informed public. And the public can't be informed if journalists can't talk to sources.

Porter's order recognizes this. It says the government can't just steamroll over press freedom while conducting an investigation. There has to be a balance.

Whether that balance holds through the full litigation is the real question.

Expert Perspectives and Industry Response

Journalist organizations and press freedom advocates have been vocal.

The Society of Professional Journalists called the seizure "alarming" and said it violates fundamental principles of press freedom. The Associated Press said it threatens the ability of journalists to protect sources. NPR's media reporters said it's "unprecedented in scope."

The Freedom of the Press Foundation, which tracks government pressure on journalists, noted this is part of a pattern. More leak investigations. More pressure on sources. More surveillance of press.

Seth Stern, the Foundation's chief of advocacy, said: "The search and seizure of Washington Post reporter Hannah Natanson's records is unconstitutional and illegal in its entirety. Even the Trump administration's own policies require searches of journalists' materials to be narrow and targeted. This was neither."

Academics who study press freedom have also weighed in. They note that broad device seizures are unusual internationally. Most democracies have stronger protections. You can't just seize a journalist's devices in the EU or UK without much more careful legal process.

America has fewer protections than most developed democracies. This case reveals how vulnerable the press actually is.

The US lags behind other democracies in journalist protections, with a score of 4 compared to higher scores in the EU and Canada. Estimated data.

What Natanson Loses During This Seizure

Let's be concrete about the harm.

Natanson can't contact her 1,100 sources. That means stories in progress stall. Investigations on hold. Sources assume cover is blown. Relationships break.

She can't access her files. Draft stories she was working on become inaccessible. Her notes. Her research. Years of work are stuck in government custody.

She can't verify reporting. When you have encrypted communications with sources and you want to confirm context or details, you reference those messages. She can't do that.

She loses professional capability. A reporter without devices is like a surgeon without instruments. The work can't happen.

Meanwhile, competitors publish. Other journalists report stories using sources that Natanson might have been developing. The window closes.

For the Post, the harm is institutional. They've lost a reporter's capability. They can't pursue investigations Natanson was working on. They lose stories, readers, influence.

The government's response would be: that's not our problem. We have legitimate law enforcement interests. If that disrupts journalism, that's unfortunate, but investigative power comes first.

But that's exactly wrong. Justice and the Constitution demand balancing. And the government didn't even try to balance. It just seized everything.

The Filter Team Precedent: Why That Matters

One of the Post's key arguments is that the government should have used a filter team.

Filter teams are exactly what they sound like. Independent lawyers (usually government lawyers from a different office) screen materials to remove privilege and irrelevant items before the investigating team sees them.

This preserves Fourth Amendment principles. The government gets access to responsive materials. But privilege stays protected. Irrelevant personal information stays hidden. The scope gets naturally limited by the screening process.

Filter teams are standard in corporate litigation. They're used in high-security contexts. They're explicitly recommended in DOJ guidelines for journalist searches.

But filter teams require patience and resources. It's easier to just seize everything and sort it out later. So the government took the easy route.

If Porter rules that filter teams should have been used, that sets precedent. Future journalist searches become more cumbersome. The government has to do the work properly.

That's why this detail matters. It's not just about this case. It's about the process for all future cases.

Constitutional Tension: Sixth Amendment Confrontation vs. First Amendment

Here's a subtle legal problem that will come up in the full briefing.

The Sixth Amendment gives criminal defendants the right to confront evidence against them. If Perez-Lugones is prosecuted, he has the right to know what evidence the government has. He has the right to cross-examine witnesses. He has the right to see documents used against him.

So if the government finds incriminating documents in Natanson's devices, those become evidence in Perez-Lugones's case. The government will want to use them to prove he leaked information.

But if Natanson asserts privilege over her sources, claiming they're protected, she's preventing Perez-Lugones from having full access to evidence. She's interfering with his right to confront accusers.

This is a real tension. How do you balance a criminal defendant's rights against a journalist's protection of sources?

Courts typically resolve this: the journalist loses the privilege if it's actually critical to a defendant's case. But the burden is very high. The defendant has to show that the privilege blocks essential exculpatory evidence.

In this case, it's unclear whether Natanson's communications with sources are even relevant to Perez-Lugones's case. Maybe they're not. Maybe they're just background on how leaks happen. If so, the Sixth Amendment doesn't override First Amendment protection.

This is the kind of nuance that will emerge in briefing.

Comparison to International Press Freedom Standards

America's protection of journalists is actually below the standard in many democracies.

The EU has stronger protections for journalists' materials. Germany and France both have specific laws protecting journalist-source privilege. The UK has common law protection. Canada recognizes privilege.

America? No federal privilege. No uniform protection. It's a patchwork of state laws and judicial discretion.

International journalism organizations have flagged America's vulnerability as a concern for press freedom. When reporters lack reliable protection, they self-censor. That weakens democracy.

This case is actually a moment where America's system is being tested against international standards. If Porter sides with the Post, it brings America closer to international norms. If the government wins, it moves America further from international standards.

That has soft power implications too. America claims to support free press globally. If America's own press doesn't get basic protections, that message rings hollow.

The Filter Team Solution: What Should Have Happened

Let's imagine how this should have played out.

- The FBI investigates Perez-Lugones and believes he may have leaked to Natanson

- They draft a narrow warrant: only seeking documents received from Perez-Lugones, only during the three-month window when he was allegedly collecting material

- They execute the warrant but use a filter team to review materials

- The filter team removes privileged materials, personal information, and irrelevant files

- Only responsive documents go to the investigating agent

- Natanson's sources remain protected. Her privilege is protected. Her personal information is protected.

That's the process DOJ guidelines recommend. That's how courts expect it to happen.

It takes longer. It requires more careful work. It requires honoring the press freedom interest during the investigative process, not after.

But it's the right way to do it. The government just didn't bother.

Looking Ahead: What February 6 Might Bring

The oral arguments are going to be intense.

The government will argue that the warrant was properly issued. The search is reasonable under the Fourth Amendment. The investigation is legitimate. Press freedom doesn't override law enforcement needs.

The Post will argue that the First Amendment protects the press from broad searches designed to uncover sources. That prior restraint doctrine limits the government's power. That even if the investigation is legitimate, the execution was unconstitutional.

Porter will have to decide: Is this search constitutional? If not, what remedy is appropriate? Return the devices? Suppress any evidence found? Both?

The decision will be technical and legal. But it'll have real consequences for press freedom in America.

If Porter sides with the Post, he might become a hero to journalism advocates. If he sides with the government, he signals that broad journalist searches are permissible.

Either way, it's likely going to be appealed. This will drag on for a while. Natanson's devices will remain in limbo. The broader questions about press freedom will remain unresolved until a higher court weighs in.

The Bigger Picture: Trends in Government Pressure on Press

This case is part of a larger trend.

Over the past decade, there's been increasing government pressure on leakers and journalists. More leak investigations. More surveillance. More aggressive use of warrants and subpoenas.

Some of this is structural. More digital communication means more digital trails. More ways for government to find out who's leaking. Better forensics and surveillance technology.

But some of it is also political. Administrations that view the press skeptically are more likely to use law enforcement tools against journalists.

The combined effect is that journalist-source relationships have become riskier. Sources know the government can probably find out who they are. That changes calculations. Some people who might have leaked misconduct decide it's not worth it.

Democracy runs on information flow. When information gets constrained, democracy suffers.

That's why this case matters beyond the specific facts. It's about whether America's press can operate with basic protection. Or whether government power overwhelms press freedom.

Final Implications: Democracy and Government Accountability

Let's step back and think about what press freedom actually does in a democracy.

It checks power. Journalists find out what government is doing. They report it. Public knows. Public gets angry. Accountability happens.

Without protected press, that mechanism breaks. Government acts in darkness. Misconduct stays hidden. Corruption goes unexposed.

This case is about whether that checking mechanism survives. If the government can seize a journalist's devices and search through all her sources and communications, then government pressure can effectively silence journalists.

Not through explicit censorship. Just through the fear that your sources will be exposed. That your confidential relationships will be revealed. That you'll lose your ability to do investigative work.

That's why the Natanson case matters. It's not just about one reporter or one investigation. It's about whether American democracy retains the institutional capacity to hold government accountable.

Judge Porter's standstill order is a temporary protection. But the broader question remains: What's the actual level of press protection in America? What power do journalists have to resist government pressure? How strong are the First Amendment limits on law enforcement?

The February 6 oral arguments will start to answer those questions. But realistically, the Supreme Court might eventually have to weigh in. This case touches fundamental Constitutional issues that probably need the highest court's guidance.

Until then, Natanson waits. Her devices sit in government custody. Her sources wonder if they've been exposed. And every other journalist in America watches carefully. Because what happens in Porter's courtroom affects what happens to all of them.

FAQ

What is a standstill order and why did Judge Porter issue one?

A standstill order is a temporary court order that freezes an ongoing process while legal questions get resolved. Judge Porter issued one to prevent the FBI from searching Hannah Natanson's seized devices until the court decides whether the search was constitutional. The order preserves the status quo and protects potential privilege while the broader legal issues are briefed and argued.

Why does the Washington Post argue this is prior restraint?

The Post argues that seizing Natanson's devices prevents her from publishing stories and contacting sources, which effectively restrains her ability to practice journalism before publication occurs. Prior restraint doctrine holds that government cannot block speech before it happens. By seizing her professional tools, the government has restrained her ability to gather information and publish, according to this argument.

What is attorney-client privilege and why is it relevant here?

Attorney-client privilege protects confidential communications between lawyers and clients from being discovered or used against them. Natanson communicated with the Washington Post's legal team after the search, and those communications are privileged. If the government searches her devices without respecting privilege, it could access these protected communications and potentially undermine her legal defense.

How many sources did Hannah Natanson have in her contacts?

Natanson maintained an encrypted contact list of over 1,100 current and former government employees with whom she communicated through encrypted Signal chats. Without access to her devices, she cannot contact these sources, which effectively halts her ability to conduct reporting and maintain confidential relationships essential to investigative journalism.

What is a filter team and why should the FBI have used one?

A filter team is a group of independent attorneys (typically government lawyers from a different office) who review seized materials to remove privileged communications, personal information, and irrelevant documents before handing responsive materials to the investigating agent. DOJ guidelines recommend filter teams for journalist searches to protect privilege while allowing legitimate law enforcement access to responsive materials. The FBI did not use a filter team here, which the Post argues violates federal procedures.

What was the government investigating Aurelio Perez-Lugones for?

Perez-Lugones was a Pentagon system administrator with top-secret security clearance who allegedly took classified intelligence reports home and may have leaked them. The government suspected he provided these documents to Natanson, which is why they sought a warrant to search her devices. However, the government's own criminal complaint indicates Perez-Lugones possessed only a limited number of documents for only three months, suggesting the universe of responsive material was small.

What happens at the February 6 oral arguments?

At the February 6 oral arguments, both the government and the Washington Post will present their legal positions to Judge Porter. The government will argue why the search warrant was proper and the search is justified. The Post will argue why the search violates the First and Fourth Amendments and why the devices should be returned. Judge Porter will ask questions and eventually rule on whether the standstill order becomes permanent and what happens next.

Why did the government refuse to use a subpoena instead of a search warrant?

The Post suggested the government could have simply subpoenaed communications with Perez-Lugones instead of seizing all six devices. A subpoena would allow the Post and Natanson to contest the request, assert privilege over protected materials, and limit the scope through negotiation. The government apparently believed a surprise warrant and seizure was more effective, but this approach bypassed safeguards that protect journalist materials and source confidentiality.

Could this case establish precedent affecting all journalists?

Yes. If the court rules that broad device seizures of journalists are constitutional, that precedent would apply nationwide and embolden law enforcement to use similar tactics against other journalists. If the court sides with the Post, it would establish stronger protections for journalist materials in leak investigations and require more careful, narrow approaches to journalist searches going forward.

What is the broader significance of this case for press freedom in America?

This case tests whether American journalists have real First Amendment protection when government investigators seize their materials. It reveals that America lacks the journalist-source privilege protection that many other democracies provide. If the government prevails, it demonstrates that press freedom in America is weaker than commonly assumed. If the Post prevails, it strengthens press freedom and aligns America more closely with international standards for journalist protection.

Key Takeaways

-

Temporary Protection: Judge Porter's standstill order freezes the FBI's search of Natanson's devices, but it's temporary pending full briefing and oral arguments in February.

-

Scope Problem: The government seized six devices containing over 30,000 emails, recordings, and 1,100 source contacts to find documents that probably comprise less than 1% of the seized data.

-

Source Confidentiality: Without her devices, Natanson cannot contact her 1,100 sources, effectively destroying confidential relationships essential to investigative journalism.

-

Process Violations: The government ignored DOJ guidelines requiring narrow warrants, filter teams, and subpoena attempts before journalist device seizures.

-

First Amendment Issue: The seizure functions as prior restraint by preventing Natanson from publishing and conducting investigations.

-

Weak Protections: America lacks federal journalist-source privilege that most other democracies provide, making American journalists more vulnerable.

-

Democracy Implications: If government can easily seize journalist materials and expose sources, it chills reporting on government misconduct and weakens democratic accountability.

-

Precedent at Stake: The court's decision will establish whether broad journalist device seizures are permissible nationwide.

Related Articles

- FBI Seizes Reporter's Devices: Press Freedom Under Siege [2025]

- Porn Taxes & Age Verification Laws: The Constitutional Battle [2025]

- Porn Taxes and Age Verification Laws: The Constitutional Crisis [2025]

- How Communities Respond to Immigration Enforcement Crises [2025]

- UK Digital ID No Longer Mandatory: What Changed [2025]

- Internet Censorship Hit Half the World in 2025: What It Means [2026]

![FBI Device Seizure From Washington Post Reporter: Journalist Rights and First Amendment [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/fbi-device-seizure-from-washington-post-reporter-journalist-/image-1-1769040461195.jpg)