UK Digital ID No Longer Mandatory: What Changed and Why It Matters [2025]

Back in September, Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced something that made privacy advocates lose sleep. A mandatory digital ID scheme for all working adults in the UK. The plan sounded straightforward enough: crack down on illegal employment, streamline right-to-work checks, modernize the system. Sounds good on paper.

But here's where it got messy. Within months, facing massive public backlash and nearly three million petition signatures, the government quietly walked back one of its core commitments. Digital ID wouldn't be mandatory after all. Instead, it would become optional, sitting alongside traditional documentation like passports and visas.

This U-turn raises a bunch of questions. What actually happened? Why did the government change course so quickly? What does this mean for identity verification in the UK? And perhaps more importantly, what does it say about how governments balance national security, efficiency, and citizen privacy?

Let's dig into this.

TL; DR

- The original plan: Digital ID was supposed to be mandatory for all right-to-work checks starting in 2029

- The reversal: Now it's voluntary, with multiple alternative documentation methods allowed

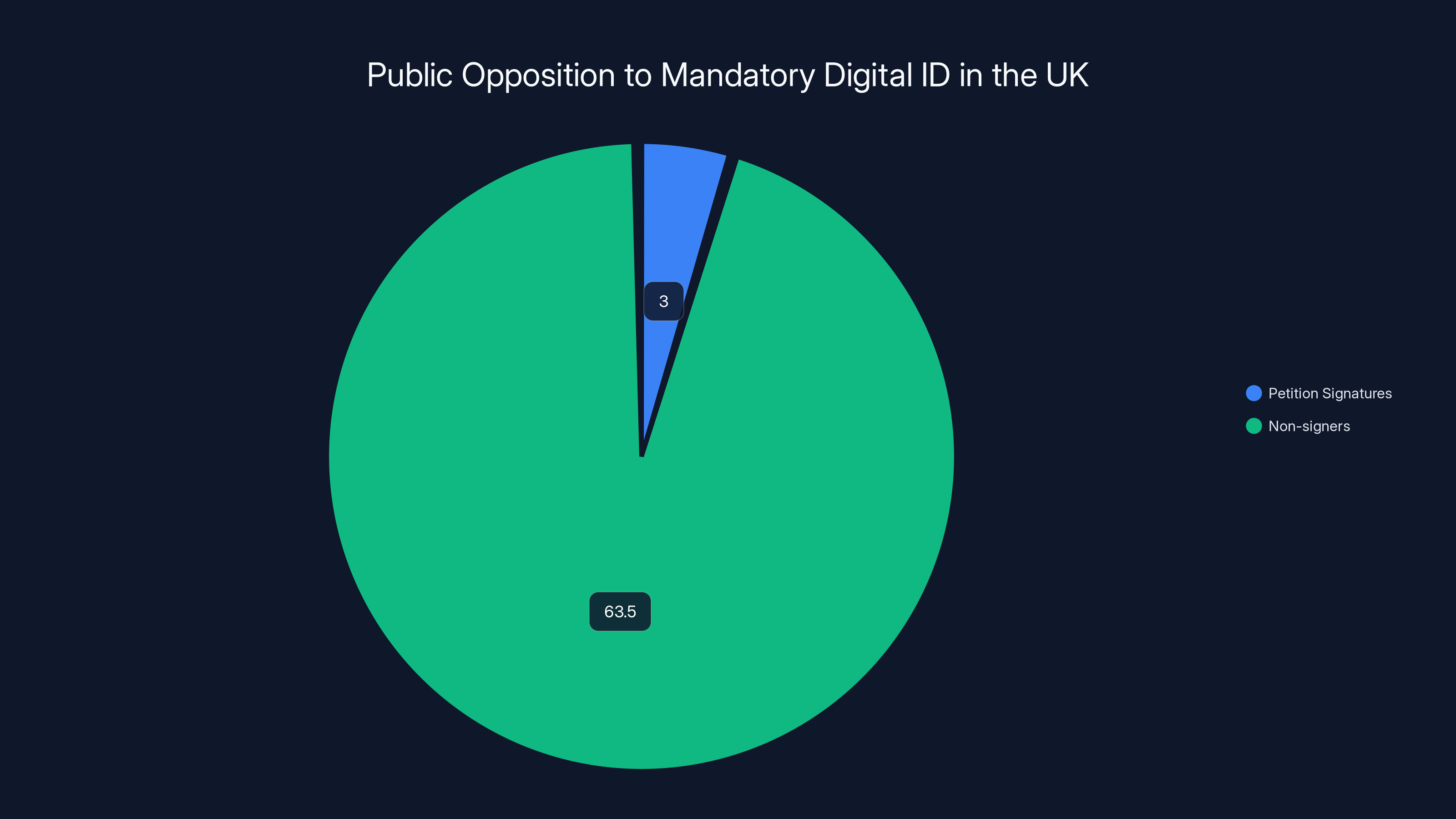

- The backlash: Nearly 3 million people signed a petition opposing mandatory digital ID

- Privacy concerns: Citizens worried about data collection, government surveillance, and digital rights

- What's next: A public consultation on final details is coming soon, with implementation still targeted for 2029

An estimated 4.5% of the UK population signed a petition against mandatory digital ID, highlighting significant public concern. Estimated data.

What Exactly Is the UK Digital ID Scheme?

Before we talk about why the government backed down, let's understand what they were actually proposing.

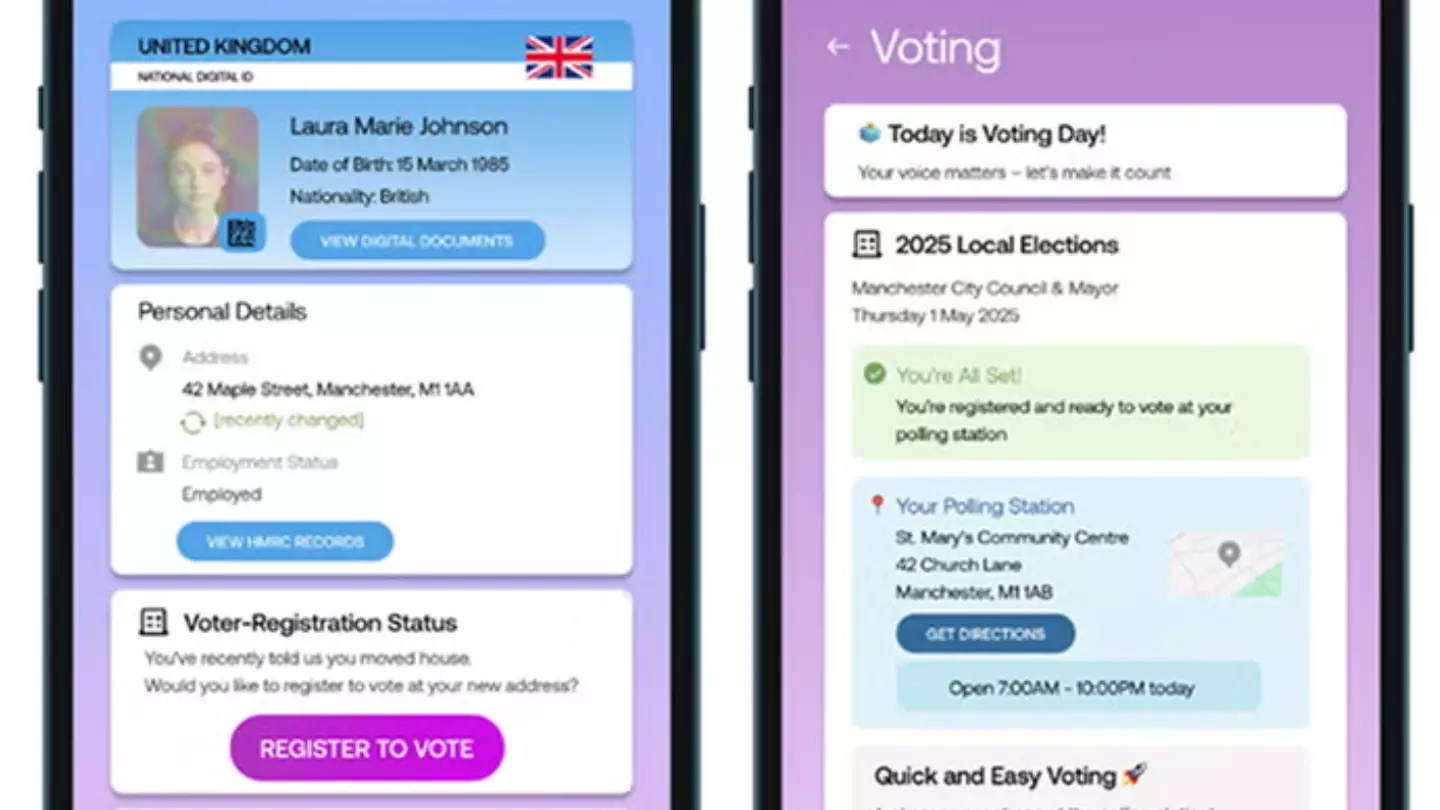

The digital ID scheme isn't some abstract government project. It's designed as a concrete tool: a digital identity stored on your smartphone containing your name, date of birth, nationality or residency status, and a photo. Think of it like a digital passport, but with specific purpose-built features for employment verification and other government interactions.

The whole system hinges on a specific problem the government identified. Right now, right-to-work checks rely on what officials called a "hodgepodge of paper-based systems." Employers verify eligibility through a mix of physical documents, online systems, and manual processes. There's no centralized record, no way to track when checks happened, and no clear audit trail. This creates what government officials argued was an open door to fraud and abuse.

Digital ID was supposed to fix that. Instead of an employer physically examining your passport or visa documents, you'd prove your right to work digitally. Fast, verifiable, with automatic record-keeping. On the surface, it's an efficiency play dressed up as a security measure.

But here's the thing. Identity verification systems, especially government-run ones, carry serious implications beyond just convenience. They touch on fundamental questions about surveillance, data ownership, and how much control governments should have over citizens' lives.

The original September announcement made mandatory adoption a core feature. By the end of Parliament's current session, digital ID would become the primary (and eventually only) way to verify employment eligibility. No paper-based workarounds. No alternatives. Digital ID, or don't work.

That mandatory requirement created an unprecedented situation. For the first time in recent British history, the government would have been collecting biometric data (photos and facial recognition-compatible images) from essentially every working adult. Not as an option. As a requirement to participate in employment.

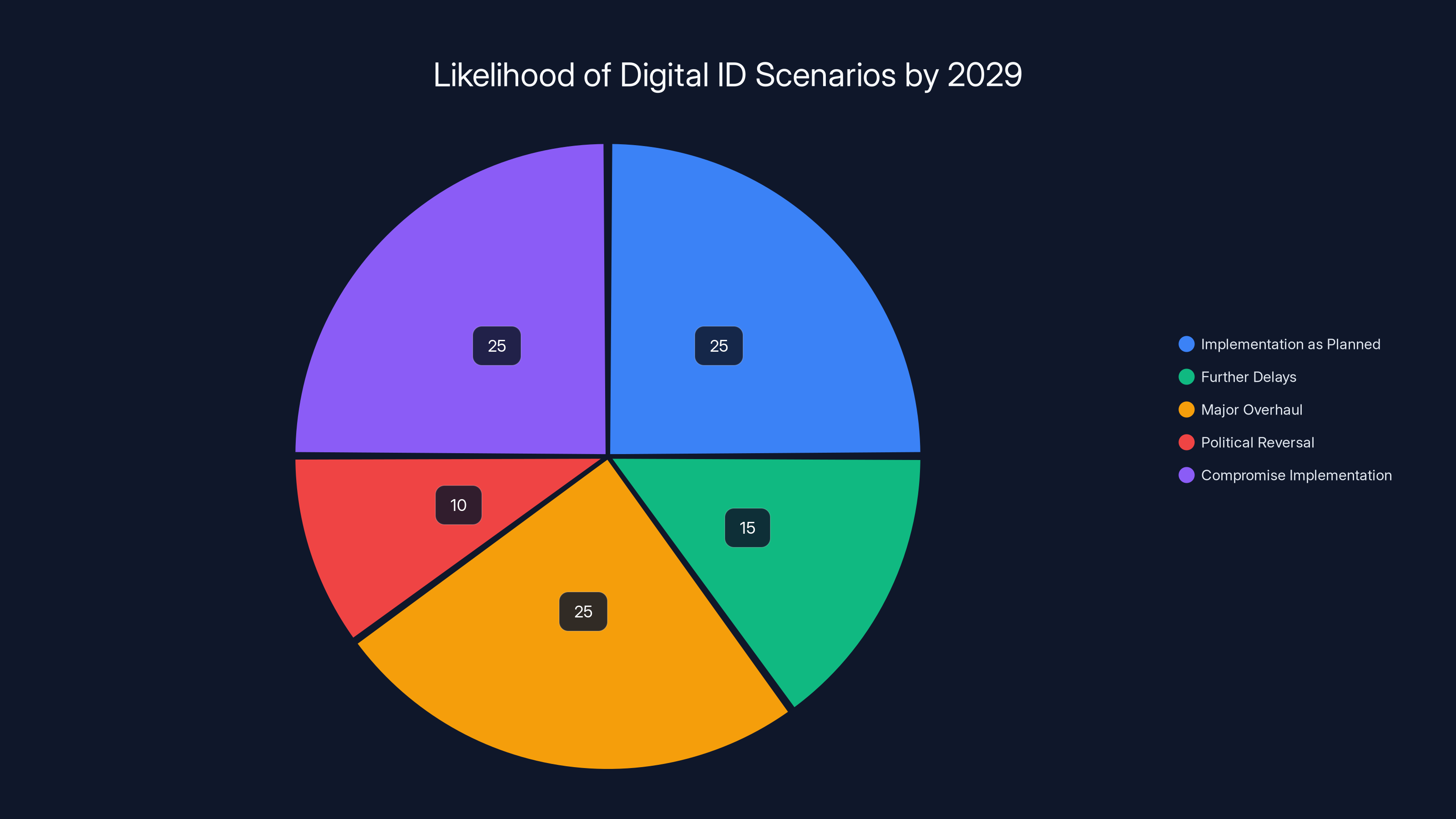

Estimated data suggests that 'Implementation as Planned', 'Major Overhaul', and 'Compromise Implementation' are equally likely scenarios for Digital ID by 2029.

The Public's Explosive Reaction to Mandatory Digital ID

When the government announced the plan in September, they probably didn't anticipate the response.

A parliamentary petition against mandatory digital ID launched and blew past normal thresholds almost immediately. Three million signatures. To put that in perspective, that's roughly 4.5% of the entire UK population. Not people who clicked a survey. Real people who cared enough to actively sign a petition opposing it.

That's not typical political noise. That's visceral public concern.

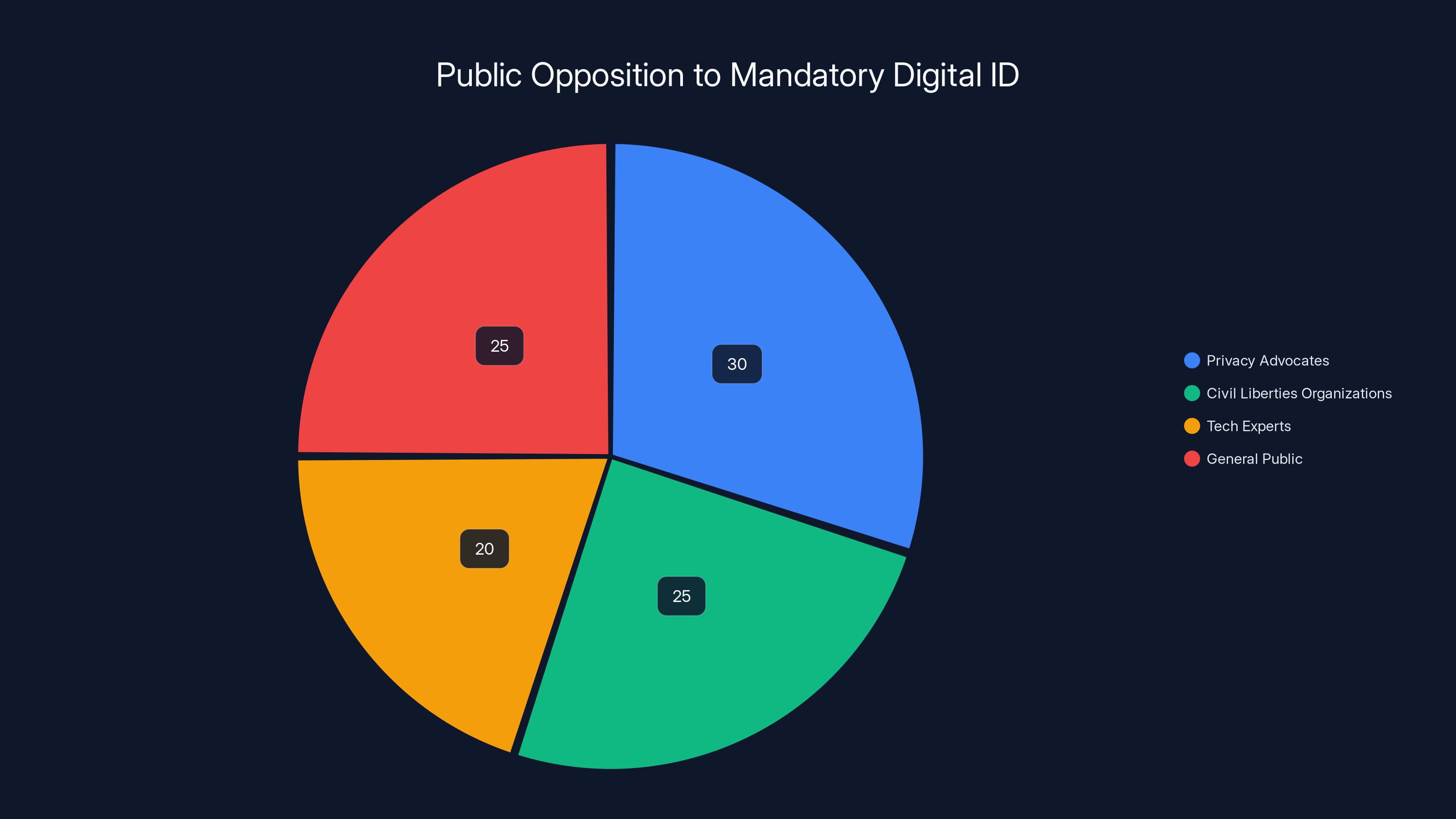

The opposition came from multiple directions simultaneously. Privacy advocates raised alarm about centralized biometric data. Civil liberties organizations warned about mission creep and government overreach. Tech experts flagged security risks. Even mainstream media outlets, not usually alarmist, started asking uncomfortable questions.

Why such intense backlash? Several overlapping reasons.

First, the data storage question. Where exactly would this biometric data live? The government's initial announcements were vague. Stored on your phone, sure, but what about backups? What about government access? What about what happens when you get a new phone? Who owns the data? These aren't academic concerns. They're practical questions about control and security.

Second, government surveillance precedent. The UK already operates some of the world's most extensive CCTV networks. The idea of a mandatory government database containing biometric information felt like another layer of tracking. Not surveillance in the traditional sense, but a form of control that governments could theoretically leverage in ways not yet contemplated.

Third, the mandatory element itself. Making something mandatory eliminates choice. If digital ID becomes your only way to work, you don't have an option to opt out. You accept the system's terms or lose economic participation. That's a fundamentally different relationship between citizen and government than voluntary adoption would be.

The combination of these factors created perfect political pressure. It wasn't just techies worried about privacy. It was ordinary people sensing they were losing a choice they didn't know they had.

Why the Government Actually Proposed It in the First Place

Understanding the U-turn requires first understanding the original motivation.

The UK has a genuine, measurable problem with illegal employment. Workers without proper visa status or residency rights participate in the job market, sometimes deliberately hired at below-minimum wages by exploitative employers, sometimes genuinely believing they have authorization.

For the government, this creates multiple headaches. There's the humanitarian angle: workers being exploited. There's the labor market angle: employers undercutting legal wages. There's the fiscal angle: unpaid taxes and benefits being claimed. And there's the political angle: voters concerned about immigration pressuring the government to "do something" about illegal employment.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer's September announcement was a response to these pressures. Digital ID seemed like an elegant solution. Modern, technological, systematic. It would catch illegal workers automatically. It would eliminate paperwork. It would make employers' lives easier while cracking down on exploitation. What's not to like?

From a pure efficiency standpoint, the logic is sound. Paper-based right-to-work checks are genuinely problematic. An employer can check a passport or visa, make a note, and never record the check happened. No audit trail. No easy way to catch fraudulent documents. No systematic approach.

Digital verification would change that. Employers could run an instant, recorded check against a secure system. Fraudulent documents would be immediately apparent. Everything would be logged automatically. The government gets better data about the labor market. Employers get easier compliance. Workers get a faster process.

The government wasn't being sinister in proposing this. They were responding to genuine problems with genuine proposed solutions. The mistake was assuming that efficiency gains and security improvements would outweigh citizens' concerns about data control and autonomy.

Estimated data shows that privacy advocates and civil liberties organizations form the largest groups opposing mandatory digital ID, each representing about a quarter of the opposition.

The U-Turn: How Mandatory Became Optional

Somewhere between September and January, political calculations shifted.

The government still maintained its commitment to digital right-to-work checks. They still want the system. They still see the efficiency benefits and the security improvements. But they could read public opinion. Three million people signing a petition isn't a minor concern you can ignore. It's a political liability.

Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves confirmed the change in a BBC interview, explaining that people would have multiple options for proving their right to work digitally. An electronic visa. A digital passport. Or the new digital ID system. All would be acceptable.

This is a critical shift, even though it sounds like a minor policy adjustment.

With mandatory digital ID: Every working adult must enroll in the government system. Everyone's biometric data gets collected. The government has a complete database of working-age citizens.

With optional digital ID: Workers can choose to use it, but don't have to. Alternative methods remain available. Participation is voluntary.

That difference ripples outward. It transforms the political economy of the system entirely.

From a government perspective, optional digital ID is less useful. You don't get universal coverage. You don't get a complete labor market database. Privacy advocates and civil liberties organizations lose their biggest concern, but you lose the comprehensive tool you originally wanted.

From a citizen perspective, optional is dramatically better. You maintain choice. If you're uncomfortable with the system, you're not forced into it. You can use traditional documentation. The government still gets a digital system, but it's not the comprehensive surveillance apparatus people feared.

The U-turn reflects a political reality of modern democracies. Governments can't force massive expansions of data collection on hostile populations without costs. The three million petition signatures made those costs clear.

The Privacy and Civil Liberties Concerns That Drove the Reversal

Let's be specific about what worried people. It's not abstract surveillance paranoia. There are concrete, documented concerns.

Biometric data permanence. Once the government collects your facial image, that data is permanent. Technology changes. New techniques for facial recognition emerge. Laws about how data can be used evolve. Future governments with different priorities might find uses for that database that current leaders don't anticipate. A facial recognition database created today with good intentions might be weaponized by a government ten years from now with different politics.

This isn't hypothetical. It's happened in other countries. Facial recognition databases created for one purpose have been repurposed for law enforcement, immigration enforcement, and political monitoring.

Data breach vulnerability. The government's digital services have experienced security incidents. The National Health Service has faced major data breaches. The Home Office has suffered security compromises. A centralized database containing biometric data for millions of citizens would be an attractive target for hackers, foreign governments, and criminals. One successful breach would expose the most sensitive form of personal data for millions of people.

Exclusion from work. Making digital ID mandatory for employment creates a backdoor coercive mechanism. You're not legally required to provide biometric data in the traditional sense. You're just required to do it if you want to work. That's a meaningful distinction legally, but not practically. If you want to participate in the labor market, you must enroll.

This creates disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations. Elderly people uncomfortable with technology. Recent immigrants unfamiliar with the system. People with disabilities that make biometric scanning difficult. Undocumented immigrants (who become unable to work entirely). The system disadvantages the already-disadvantaged.

Function creep. Once a system exists, it tends to expand. A digital ID system created for employment verification could eventually be required for healthcare access, voting, financial services, public benefits, or law enforcement. Each expansion seems reasonable in isolation. Together, they transform a specific employment tool into comprehensive government surveillance infrastructure.

This isn't paranoid. It's documented government behavior. Systems routinely expand beyond their original scope. The government's emergency powers during COVID were temporary until they weren't.

Lack of true consent. A voluntary system sounds consensual. But if it becomes the convenient, fast way to prove your right to work, employers will prefer it. Workers will face pressure to use it simply for job market efficiency, even if they're uncomfortable. That's not fully voluntary. It's coerced consent dressed up as choice.

The proposed digital system significantly improves efficiency, fraud detection, compliance ease, and data accuracy compared to the current paper-based system. Estimated data based on typical system improvements.

How the New Optional System Actually Works

With mandatory requirements off the table, what does the actual system look like?

The government is still moving forward with digital ID as an option. They're still committed to digital right-to-work checks generally. They're still pursuing the efficiency gains that motivated the system.

But now there are parallel tracks. A worker can prove their right to work through:

Digital ID: The government's new system. Biometric data, stored on your phone, used for instant employment verification.

Digital passport or visa: Official government-issued digital documents accessed through existing systems. No new biometric data collection required.

Traditional documentation: Physical passports, visas, and other papers. Employers can still use the traditional verification process.

The practical effect is significant. Most workers probably won't bother with digital ID. Why would you? If a digital passport works just as well, why provide biometric data to a new system? If traditional documentation still works, why change?

Adoption of the voluntary system will likely be moderate to low. Early adopters will use it. Some immigrants might prefer it to managing physical documents. Some employers might prefer one integrated system. But you're not going to see universal adoption just because the option exists.

From the government's perspective, this is less efficient than the original mandate. They don't get the complete labor market database. They don't get universal coverage. They still get some of the efficiency gains, but not all.

From a civil liberties perspective, this is dramatically better. The comprehensive surveillance database doesn't exist. You maintain choice. Privacy advocates got a concrete win.

Implementation Timeline: When Does This Actually Happen?

Here's something important that often gets lost in the debate: this system isn't being implemented tomorrow.

The government is targeting 2029 for the digital right-to-work system launch. That's four years away. An eternity in technology and politics.

Between now and then, several things need to happen:

Public consultation: The government promised a full public consultation on the scheme's details. They haven't announced when this starts, but it's supposed to happen before final system design is locked in.

Legal framework: Parliament needs to pass legislation enabling the system. With such public opposition to the original mandatory proposal, expect significant debate during the parliamentary process.

Technical infrastructure: Building a national digital identity system is technically complex. Servers need to be secured. Integration with employer systems needs to be designed. Backup and disaster recovery needs to be planned. Testing needs to happen. This takes time.

Workforce training: Employers need to understand how to use the system. Citizens need to know how to enroll. Government staff need training. Public awareness campaigns need to run.

Security hardening: A system this high-profile will face intense scrutiny. Security researchers will look for vulnerabilities. The government will need to address findings. Improvements will be iterative.

Four years is reasonable for a project like this, but it's also enough time for circumstances to change. A government change could shift priorities. A major data breach at a government agency could undermine public trust. Technical challenges could emerge. Public opinion could evolve further.

The 2029 date is current planning, not a guaranteed outcome. Things change.

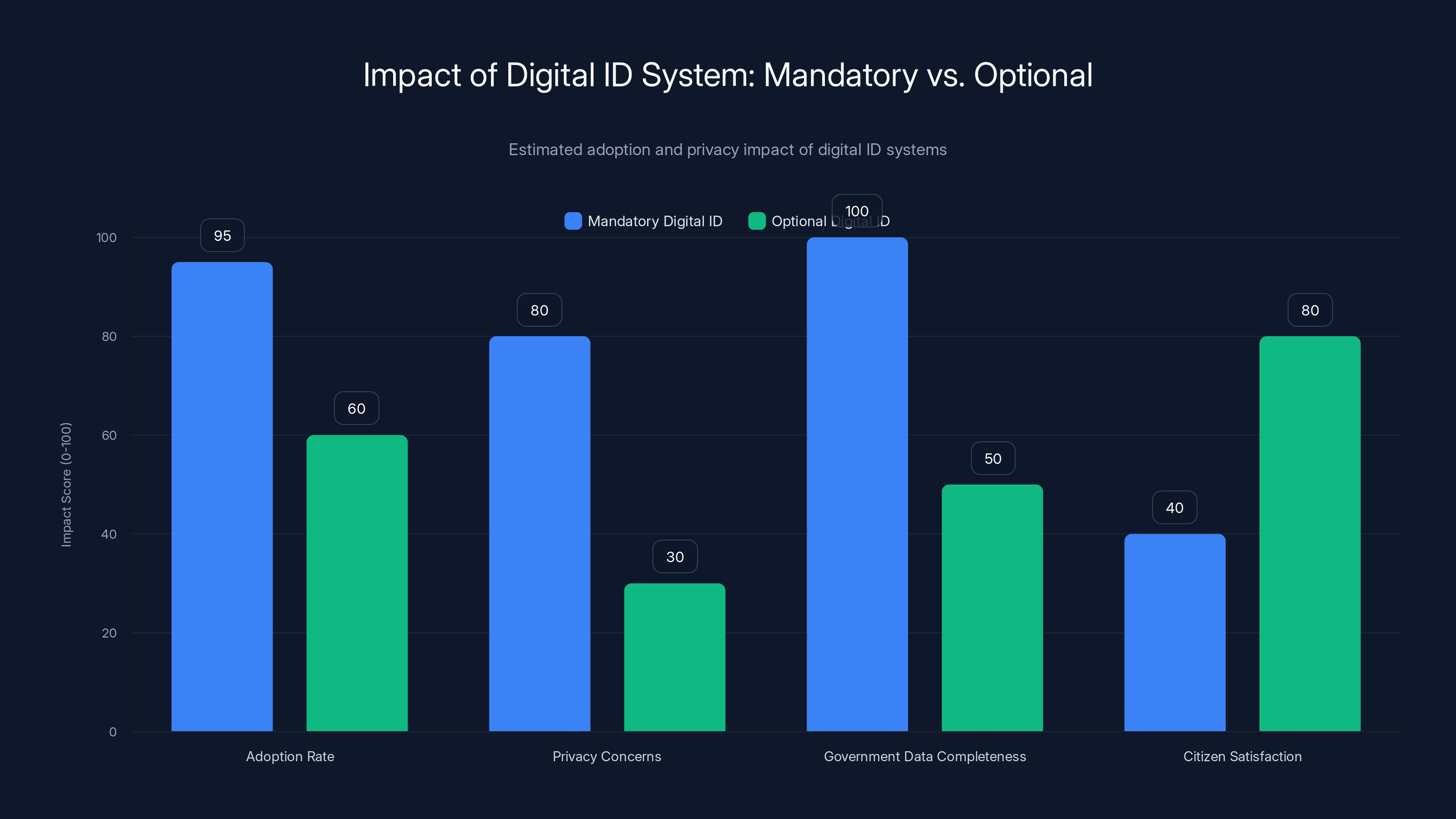

Mandatory digital ID systems have higher adoption and data completeness but raise privacy concerns. Optional systems offer more citizen satisfaction and lower privacy risks. (Estimated data)

Privacy Protections and Safeguards: What's Actually Being Planned?

The government hasn't released detailed specifications for privacy protections yet. That's supposed to come out during the public consultation.

But they've indicated some principles:

Data minimization: Only collecting data actually needed for right-to-work checks. Not gathering extra information "just in case."

User control: Individuals can see what data is held, request corrections, and understand how it's being used.

Limited access: Only authorized parties (employers conducting right-to-work checks, specific government agencies) can access the system.

Encryption and security: Data should be protected with encryption and secure access controls.

Sunset provisions: Data shouldn't be held indefinitely. Employment verification data might only be kept as long as it's actively needed.

These are reasonable principles. They're also pretty generic. The devil is in the implementation details.

A few critical gaps:

No mention of decentralization. The system is apparently centralized government infrastructure. That makes sense for efficiency but concentrates risk. One breach affects everyone.

No mention of algorithmic transparency. If the system uses machine learning to detect fraudulent documents or suspicious patterns, how does that work? Are decisions explainable? Can people understand why they were denied verification?

No mention of oversight mechanisms. Who investigates misuse? What recourse do individuals have if their data is misused? What penalties apply to government staff who abuse access?

No mention of international cooperation. Modern identity fraud often involves international elements. Does this system cooperate with other countries? Under what terms? With what safeguards?

These aren't minor details. They're fundamental to whether the system actually protects citizens or just creates new vectors for abuse.

International Perspectives: How Other Countries Handle Digital ID

The UK isn't inventing digital identity from scratch. Other countries have systems we can learn from.

Estonia: Often cited as the gold standard. Their digital ID system has been operating since 2002. It's decentralized (data lives in multiple places, not one central database), it's encrypted end-to-end, and citizens can see exactly who accessed their data and when. Estonia's system is relatively popular because it actually protects privacy while providing convenience.

Germany: Recently implemented digital IDs with strict privacy protections built in. Their system is designed so the government can verify claims ("this person has the right to work") without actually seeing personal data. It's innovative and privacy-preserving, though it's newer so less tested long-term.

Australia: Took a different approach with their digital identity system, storing less sensitive data but running into privacy criticism anyway. Some functions were narrower than planned because of public opposition.

China: Uses digital identity as a comprehensive surveillance tool, linked to social credit systems and law enforcement. Not a model to emulate, but a cautionary tale about what's possible with the same technology.

The pattern is clear: privacy-protecting digital identity is possible, but requires intentional design choices. Estonia's success comes from decentralization and transparency. Germany's comes from privacy-by-design architecture. The UK's system will depend on whether the government makes similar choices.

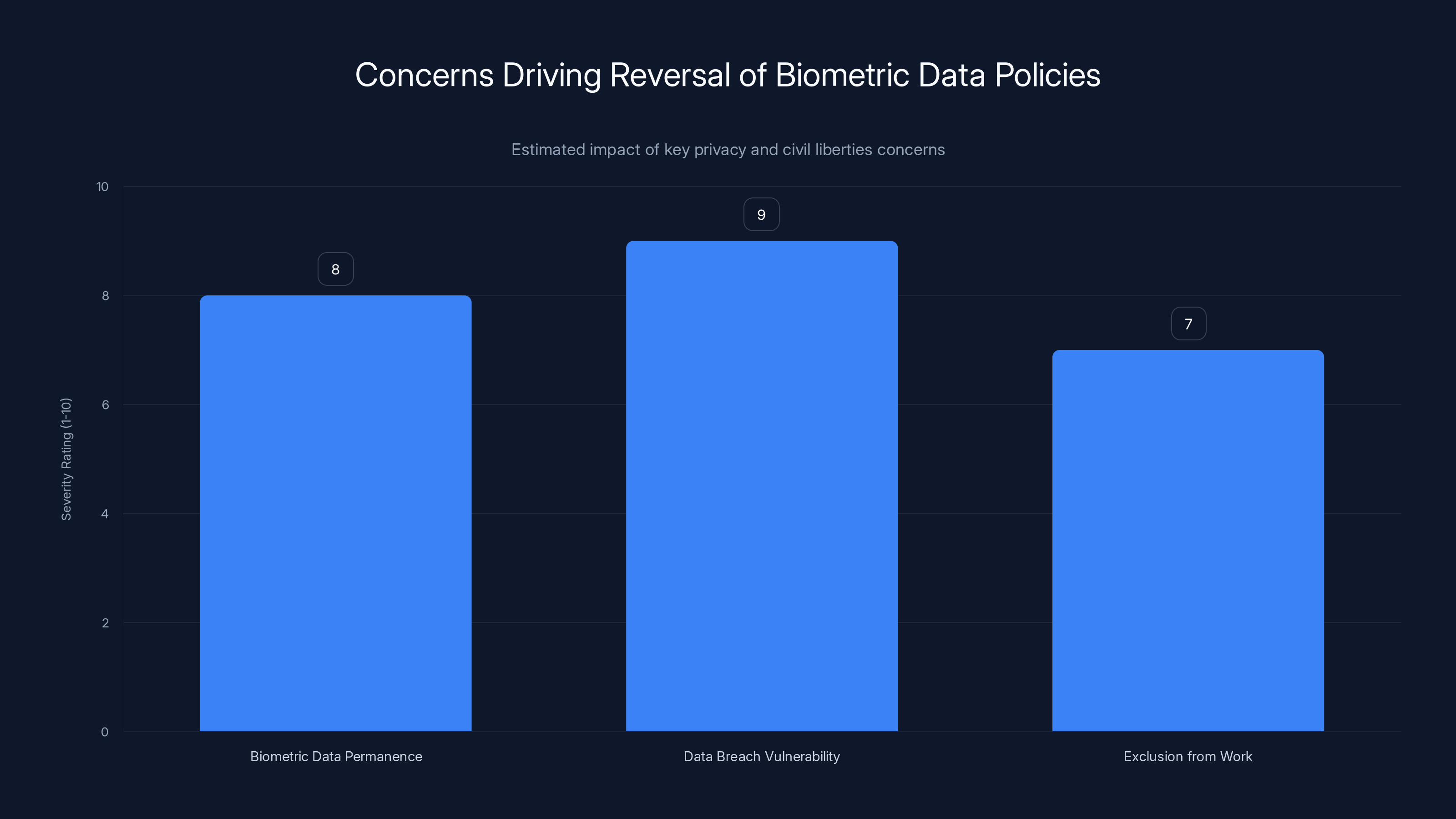

The most severe concern is data breach vulnerability, rated at 9, highlighting significant risks of centralized biometric databases. (Estimated data)

Political Implications: The Broader Meaning of the U-Turn

This isn't just a policy story. It's a political story about power, technology, and how democracies negotiate with citizens about surveillance.

The government came in with a plan. They thought efficiency gains and security improvements would be obviously good. They underestimated public concern about data collection and government power. Three million petition signatures taught them that lesson.

This suggests something important about public attitudes toward surveillance. People aren't automatically hostile to technological progress. They're not reflexively opposed to government services that use digital systems. But they do care about control. They want agency. They want to know what data is being collected and why.

Making digital ID mandatory crossed that line. It removed choice. It forced participation. It created a government database that could theoretically be used for purposes beyond employment verification. That crossed from efficient public service into something that felt like government overreach.

The U-turn is the government recognizing those limits. It's not a complete victory for privacy advocates. The system is still being built. It will still collect biometric data from millions of people. It will still be a government database. But it's optional, which changes the calculus entirely.

This probably won't be the last time this debate happens. As governments push for digital modernization, they'll keep testing where the lines are. Each time they push too far, they'll probably have to back down. Each time they back down, they learn a little more about what's actually acceptable to citizens.

What This Means for Employers: How Right-to-Work Checks Will Actually Work

Let's zoom in on the practical level. How does this actually affect businesses?

Employers currently run right-to-work checks using a mix of methods. They might check a physical passport. They might ask for a visa document. They might use the government's existing online checking service. No unified system. No consistent process.

The government wants to modernize this. Digital right-to-work checks would provide:

Speed: Instead of processing physical documents, employers get instant verification.

Compliance certainty: Automatic documentation that the check happened, when it happened, who did it.

Reduced fraud: Fraudulent documents would be immediately apparent in a digital system.

Consistent process: Same method for all workers, reducing confusion.

With optional digital ID, employers will probably have several pathways:

Government digital portal: A standardized system for checking right-to-work status using digital ID, digital passport, or other government documents.

Traditional checks: Continuing with physical document verification for workers who don't use digital systems.

Variation and complexity: During transition, employers might need to support multiple verification methods simultaneously.

From an employer perspective, optional is actually less efficient than mandatory would have been. Universal digital ID means one standard process. Optional digital ID means managing multiple pathways. But it's the trade-off required to respect worker privacy concerns.

The Future: Will Digital ID Actually Happen in 2029?

Prediction is hard, especially about the future. But some scenarios seem more likely than others.

Scenario 1: Implementation as planned. The government launches the optional digital ID system in 2029. Adoption is moderate. Maybe 20-40% of workers use it. Employers gradually adopt it alongside traditional methods. The system persists but never becomes dominant.

Scenario 2: Further delays. Technical challenges or new political complications push the launch to 2030 or 2031. Each year of delay gives opponents more time to organize. Implementation eventually happens but smaller than originally planned.

Scenario 3: Major overhaul during consultation. The public consultation surfaces concerns that require significant redesign. The system that eventually launches looks quite different from current plans. Features are cut. Privacy protections are strengthened. Implementation scope is reduced.

Scenario 4: Political reversal. A new government election produces a different party in power. The new government deprioritizes digital ID. The system gets sidelined in favor of other initiatives. It might eventually launch in minimal form or not at all.

Scenario 5: Compromise implementation. The government launches digital ID but in a much more limited form than originally planned. Maybe just for immigration-related employment checks, not universally. Maybe with stronger privacy protections than currently planned. Maybe with shorter data retention periods.

Of these, Scenarios 1 and 3 seem most likely. The government has political investment in some kind of digital right-to-work system. They've already walked back the most controversial element (mandatory requirement). They're probably going to push forward with something, though perhaps smaller and more privacy-focused than originally conceived.

The consultation process over the next year will be critical. What concerns emerge? How does the government respond? Does it signal flexibility or determination to push ahead? The answers to those questions will probably predict which scenario actually happens.

Workforce Implications: What Workers Actually Need to Know

If you're someone who works in the UK, what should you actually care about here?

Nothing changes immediately. The system isn't launching until 2029. Right-to-work checks continue as they currently work. No disruption to your job or your ability to work.

You'll eventually get a choice. When the system launches, you can choose to use digital ID or stick with traditional documentation. Either way works for employment verification.

Biometric data is optional. Unless something changes during the consultation, digital ID is purely voluntary. The government can't require you to provide a facial image unless you actively choose to use their new system.

Consider your comfort level. Digital ID is probably more convenient than managing physical documents. It's faster. Employers like it. But if you're uncomfortable with government biometric data collection, you don't have to participate. Your alternative options are fine.

Pay attention during consultation. If you care about privacy, watch what the government actually proposes for privacy protections. The public consultation is when input matters. That's when you can make your views known if you're concerned about how the system will work.

Don't panic about existing privacy. This isn't about the government suddenly gaining surveillance powers they didn't have before. They already monitor employment. They already have databases about visas, residency, and work eligibility. Digital ID is about modernizing how they access information they already collect. Important distinction.

The Broader Context: Government Digital Services and Trust

This story sits within a larger context of how governments use technology and how citizens react.

Governments worldwide are increasingly digital. They're moving services online. They're collecting more data. They're using artificial intelligence and automation. These changes promise efficiency, better service, cost savings.

But they also create risks. Data breaches become catastrophic when they involve government systems. Algorithmic bias becomes dangerous when used in government decisions. Surveillance infrastructure can be weaponized. Centralized databases create single points of failure and abuse.

Citizens are increasingly skeptical. They want the benefits of digital government services but worry about the risks. They want their government to be efficient but not invasive. They want technology but not surveillance.

The digital ID story in the UK is one example of that tension. The government trying to modernize. Citizens saying "wait, not like that." Negotiation. Compromise. The government backing down from mandatory requirements to something optional.

Will that be enough? Will optional digital ID actually address citizens' concerns? Or will opposition continue as the system gets built?

Those are the real questions hanging over this policy.

FAQ

What is the UK digital ID scheme and why was it created?

The UK digital ID scheme is a government initiative to modernize how people prove their right to work. Instead of using physical documents like passports and visas, workers would be able to use a digital identity stored on their smartphones containing their name, date of birth, nationality, residency status, and a photo. The scheme was created to address what the government called a "hodgepodge of paper-based systems" for employment verification that creates opportunities for fraud and abuse. The original plan, announced in September 2024, was to make this digital ID mandatory for all right-to-work checks by the end of Parliament's current session.

Why did the UK government reverse the mandatory digital ID requirement?

The government reversed the mandatory requirement after facing unprecedented public opposition. A parliamentary petition against mandatory digital ID attracted nearly 3 million signatures, representing about 4.5% of the entire UK population. Public concerns centered on biometric data privacy, potential government surveillance, function creep (where systems expand beyond original purposes), and the loss of choice. Privacy advocates, civil liberties organizations, and ordinary citizens expressed alarm at the prospect of a centralized government database containing facial images and personal data for every working adult. Chancellor Rachel Reeves confirmed in a BBC interview that digital ID would now be optional, with multiple alternative verification methods remaining available.

How will the optional digital ID system actually work?

Under the revised optional system, workers will have three ways to prove their right to work: using the new digital ID system, using digital versions of existing government-issued documents (like electronic passports or visas), or using traditional physical documentation. Employers can continue running right-to-work checks through any of these methods. The government is moving forward with building the digital ID infrastructure and expects to launch the system in 2029. However, participation will be voluntary rather than mandatory, meaning workers who prefer not to use digital ID can continue using traditional documentation without consequence.

What privacy protections are being planned for the digital ID system?

The government has indicated general principles for privacy protection including data minimization (collecting only data necessary for right-to-work checks), user control over personal data, limited access (only authorized parties), encryption and security measures, and data retention limits. However, detailed specifications for these protections haven't been finalized yet. The government promised a full public consultation where specific privacy safeguards will be detailed. Important gaps remain unclear, including whether the system will be decentralized, how algorithmic decisions will be made transparent, what oversight mechanisms will exist, and how international cooperation will be handled.

When will the digital ID system actually launch?

The government is targeting 2029 for the digital right-to-work system launch, which is approximately four years away. Between now and then, the public consultation process needs to occur, enabling legislation must pass through Parliament, and technical infrastructure must be built and tested. Four years is a reasonable timeline for a project of this complexity, but circumstances and political priorities can change. The consultation process and parliamentary debate could extend the timeline, or political changes could shift the project's scope or priority. The 2029 date is current planning but not guaranteed.

What data will the digital ID system actually collect from citizens?

Based on current plans, the digital ID will initially collect a person's name, date of birth, nationality or residency status, and a photograph. The photograph is particularly sensitive because it contains biometric data that could be used for facial recognition technology. The government has indicated the system will operate on a data minimization principle, meaning they won't collect extra information "just in case." However, the specific scope of what data is collected and how long it's retained hasn't been finalized. The public consultation will presumably address these specifics in detail.

How do other countries handle digital ID systems, and what can the UK learn?

Estonia operates what many consider the gold standard digital ID system, which has been running since 2002. Their approach uses decentralization (data lives in multiple locations rather than one central database), end-to-end encryption, and transparency (citizens can see exactly who accessed their data and when). Germany recently implemented digital IDs with privacy-by-design architecture where the government can verify claims without actually seeing personal data. Australia's digital identity system took a narrower scope approach after public opposition to broader proposals. China's system serves as a cautionary tale of how digital ID can become comprehensive surveillance infrastructure. The UK could learn that privacy-protecting digital identity is possible but requires intentional design choices and decentralization rather than centralized government databases.

What happens if I don't want to use digital ID? Will I be forced to participate?

No. The revised optional system means digital ID participation is entirely voluntary. You are not forced to use it. Workers who prefer not to provide biometric data to the government can continue using traditional documentation like physical passports and visas. Employers must continue accepting these traditional methods. The government cannot require you to enroll in digital ID as a condition of employment, though individual employers might prefer it for speed and convenience. You maintain full choice whether to participate or use alternative verification methods.

Could the digital ID system be used for purposes beyond right-to-work checks?

This is one of the core concerns that drove public opposition. In principle, a digital ID system could be expanded to other government functions like healthcare access, voting, public benefits, or law enforcement. This is called "function creep." While the government insists the initial system is specifically designed for right-to-work checks, critics worry that once the infrastructure exists, future governments might expand it. This is a documented pattern in government surveillance systems. The public consultation and legal framework for the system will be important moments to build in restrictions against function creep and require Parliament to approve any expansions.

Key Takeaways and What Comes Next

The UK's reversal on mandatory digital ID represents something important about modern democracies. Governments can't force comprehensive surveillance infrastructure on unwilling populations without political costs. Three million petition signatures made those costs clear, and the government responded by backing down from mandatory requirements.

But the story isn't over. Digital ID is still being built. It's still collecting biometric data from participants. It's still a government database. The change from mandatory to optional doesn't eliminate all concerns. It just changes the nature of the risk.

Over the next few years, several things matter:

The public consultation. This is when specific privacy protections get detailed. It's when opponents can raise concerns. It's when improvements can be mandated. Pay attention to what emerges here.

Parliamentary debate. As legislation enabling the system passes through Parliament, scrutiny will increase. Amendments requiring stronger privacy protections or limiting scope are possible. Political opposition to the system might reemerge.

Technical implementation. What the government actually builds might differ from what they promise. Implementation details matter. A well-designed system protecting privacy looks different from a system that's just technically adequate.

Public perception. As the system gets built and eventually launches, how do people actually use it? Does it become the convenient standard workers adopt? Or do most people stick with traditional documentation? Public adoption patterns will determine the system's real-world impact.

International precedent. How do other countries' digital ID systems perform? Do they protect privacy as promised? Do they suffer breaches? Do they get expanded beyond original purposes? These experiences will inform UK discussions.

The mandatory digital ID proposal failed because government and citizens couldn't agree on the terms. The negotiation resulted in optional digital ID. But that's probably not the end of the discussion. As the system develops, new questions will emerge. New concerns will surface. The conversation between government and citizens about how much surveillance is acceptable, what protections matter, and what role government should play in identity verification will continue.

That conversation is actually healthy. It's democracy working. Government proposes. Citizens respond. Compromise emerges. The system that eventually launches (if it does) will reflect that negotiation. That's probably better than a system the government imposed unilaterally.

The UK digital ID story is still being written. The interesting chapters are ahead.

Related Articles

- Roblox Age Verification Requirements: How Chat Safety Changes Work [2025]

- Trump's ICE Militarization Has Made Proud Boys Obsolete [2025]

- Senate Passes DEFIANCE Act: Deepfake Victims Can Now Sue [2025]

- Ring's AI Intelligent Assistant Era: Privacy, Security & Innovation [2025]

- Internet Censorship Hit Half the World in 2025: What It Means [2026]

- Porn Taxes & Age Verification Laws: The Constitutional Battle [2025]

![UK Digital ID No Longer Mandatory: What Changed [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/uk-digital-id-no-longer-mandatory-what-changed-2025/image-1-1768414679236.jpg)